ABSTRACT

This article explores community responses to ‘Golden Head’, a guerrilla artwork that was installed covertly in a Melbourne park in early 2020 by unknown persons. Focusing on local residents’ reactions to this mysterious, unsanctioned statue, we document an ongoing array of playful speculations, creative responses and imaginative interactions that unfolded both in situ and via social media. We argue that in eliciting an outpouring of jokes, memes, stories, photographs and other creative rejoinders, this enigmatic object has strengthened and renewed a collective sense of place. We also consider Golden Head’s reception in light of recent challenges to the legitimacy of many traditional memorial statues, and as a response to the increasingly over-regulated city. We conclude that this outpouring of imaginative local reactions to Golden Head constitutes a playful form of collective place-making that implicitly critiques the grandiose ambitions of official statues and affirms the oft-neglected ludic potential of urban space.

Resumen

Este artículo explora las respuestas de la comunidad a ‘Golden Head’, una obra de arte de guerrilla que fue instalada de forma encubierta en un parque de Melbourne a principios de 2020 por personas desconocidas. Centrándonos en las reacciones de los residentes locales ante esta estatua misteriosa y no autorizada, documentamos una serie continua de especulaciones divertidas, respuestas creativas e interacciones imaginativas que se desarrollaron tanto in situ como a través de las redes sociales. Argumentamos que al provocar una avalancha de bromas, memes, historias, fotografías y otras réplicas creativas, este objeto enigmático ha fortalecido y renovado un sentido colectivo de lugar. También consideramos la recepción de Golden Head a la luz de los recientes desafíos a la legitimidad de muchas estatuas conmemorativas tradicionales y como una respuesta a la ciudad cada vez más sobrerregulada. Concluimos que este torrente de reacciones locales imaginativas a Golden Head constituye una forma lúdica de creación colectiva de lugares que critica implícitamente las ambiciones grandilocuentes de las estatuas oficiales y afirma el potencial lúdico del espacio urbano, a menudo descuidado.

Résumé

Cet article examine les réactions de la communauté face à la « Tête d’or » (Golden Head), une œuvre de guérilla artistique installée anonymement et mystérieusement dans un parc de Melbourne au début de l’année 2020. Par le biais d’une étude des réactions des riverains face à cette statue énigmatique et en dehors des règles, nous documentons une pléiade sans fin d’hypothèses farfelues, de réactions créatives et d’interactions imaginatives qui ont fait surface sur place autant que sur les réseaux sociaux. Nous soutenons que cet objet énigmatique, qui a suscité une cascade de plaisanteries, de mèmes, d’histoires, de photos et toutes autres sortes de réparties originales, a renforcé et renouvelé un sentiment collectif de lieu. Nous étudions aussi l’accueil de la Tête d’or par rapport à la récente remise en question de la légitimité de certaines statues commémoratives traditionnelles, et comme réponse à une ville de plus en plus surréglementée. Nous concluons que ce déferlement de réactions imaginatives à l’échelle locale engendré par la Tête d’or constitue une forme fantaisiste de création collective de lieux, qui critique de manière implicite les ambitions grandioses des statues du quartier et affirme le potentiel ludique souvent négligé des espaces urbains.

KEYWORDS:

PALABRAS CLAVE:

MOTS CLEFS:

Introduction

On Australia Day, 26 January 2020, inhabitants of the Melbourne suburb of Northcote awoke to find a curious new addition to their much-valued recreational space, All Nations Park. Standing proudly at the park’s summit, gazing across the urban vista, was a peculiar statue: a gold-painted head atop a tall rectangular plinth.

Located six kilometres north-west of Melbourne’s city centre, Northcote has around 25,000 residents. Before white settlement in the 1830s, the area’s lush grasslands and woods were home to the Wurundjeri people for over 30,000 years. Once a working-class industrial suburb, in recent decades Northcote has undergone extensive gentrification, with an influx of high-income residents, though pockets of low-income inhabitants remain. All Nations Park was formed in 2002 on a reclaimed landfill site. The popular 13-hectare park includes an ANZAC memorial, lake, performance area, playground, skate park, Indigenous gardens and exercise equipment.

This article explores community responses to the covertly installed guerrilla artwork known as ‘Golden Head’. Opening with a survey of Melbourne’s memorial landscape, we consider the artwork’s reception in the context of contemporary public debates about the legitimacy of many traditional memorial statues. We then focus on local residents’ reactions to this unsanctioned monument, documenting an array of playful speculations, creative imaginings and interactions that have unfolded in situ and via social media. We argue that this creative outpouring constitutes a playful form of collective place-making, one that serves to implicitly critique the grandiose ambitions of traditional commemorative statues. As Courage (Citation2021, p. 3) emphasises, a totalising definition of placemaking is best avoided. Nonetheless, she submits that contemporary placemaking has decentred the ‘primary focus on buildings and macro urban form’ – such as the installation of authoritative memorials – that characterised elite strategies. Current placemaking practices often reflect wider local concerns and desires, and are undertaken by diverse ‘communities of practice’. We contend that Golden Head’s installation, and the interpretations and interactions prompted by the sculpture, exemplifies such a shift.

Empirical data were derived from social media posts and qualitative interviews. Our primary data comprised user-generated comments and visual content posted to a public Facebook group by local residents and park visitors over nine months, from late January to mid-October 2020. Content was collected over a four-week period and extracted via screenshots for passive analysis. We searched the group’s timeline for references to the guerrilla artwork, collated some 700 text-based comments and 500 visual artefacts, and undertook qualitative textual analysis to identify key themes, categories, patterns and practices. A smaller data set was drawn from related content posted to the public Facebook page of Darebin City Council, the local government body that manages All Nations Park. A third set of empirical material comprised separate interviews with the Mayor of Darebin and a Northcote resident who mediated negotiations between council and the statue’s anonymous creators. Drawing on narrative inquiry (Price, Citation2010), visual ethnography (Pink, Citation2013) and social semiotics (Poulsen et al., Citation2018), our analysis reflects the dynamic interplay of multimodal content on social media platforms. Data was coded manually using an inductive-deductive approach, within a primarily data-driven frame. Online content is cited with its publication date noted, and the user’s name redacted.

The shifting status of the ‘great man’ statue

Like most cities with colonial and nationalist histories, Melbourne’s memorial landscape remains littered with commemorative statues of ‘great men’. Typically fashioned in classic realist styles and installed on plinths in public spaces, these forms inscribe ‘a set of symbolic codes, ordering discourses, and master narratives’ (Sherman, Citation1999, p. 7) through which powerful groups seek to imprint their ideological authority and legitimacy on place.

In Melbourne, these figures purvey symbolic meanings about imperial power, tradition, loyalty and wise governance, ensuring the ideological stamp of empire continues to echo across the city. Later statues inscribe nationalist heroism and military sacrifice through ‘pioneering’ explorers and statesmen (Edensor, Citation2020), honouring ill-fated explorers Burke and Wills, navigator Matthew Flinders and assorted politicians, judges and philanthropists. In the Domain Parklands, south of the Yarra River, a particular realm of the city has been assigned for the commemoration of British monarchs, statespersons and military heroes in bronze and stone, collectively asserting the authoritative meanings and feelings of those who installed them. A marble likeness of Queen Victoria conjures up ‘the ideas, aspirations and motivations of the first generations of Anglo-colonial settlers’ (Vaughan, Citation2013), while equestrian statues of King Edward VII and the Marquis of Linlithgow, Victoria’s governor from 1889–95, accompany a lofty bronze memorial to King George V, unveiled in 1952.

These figural statues are dwarfed by the nearby Shrine of Remembrance. Built between 1927 and 1934, this colossal structure exemplifies how national commemorative strategies increasingly eschewed figurative representations and sought to align personal with public memory and mourning, especially following WWI. Yet the Shrine also inscribes the reified centrality of Anzac commemoration in the national mythscape on place; the annual Anzac Day Dawn Service, attracting tens of thousands, underpins the tendencies for monuments of this scale to stage the ‘rituals, festivals, pageants, public dramas and civic ceremonies [that] serve as a chief way in which national societies remember’ (Hoelscher & Alderman, Citation2004, p. 350). Such memorials consolidate ‘the affective and emotional connections between people and place over time, and reinstate memories of trauma and war’ (Drozdzewski et al., Citation2016), the Shrine’s material immensity symbolically resonating with the weight of the trauma that pervaded post-WWI Australia. Yet despite the imposing presence of this gigantic placemaking project, across Australia the centrality of Anzac commemoration is increasingly challenged by anti-militarist, Indigenous and gendered critiques.

While the 19th and early 20th century commemorative craze for erecting monuments to ‘great men’, military loss and heroism testifies to how the powerful have imprinted their values and identities on place, since WWII Melbourne’s material memoryscape has become more variegated and complex. Today, memorials from different eras commemorate a range of identities, styles and ideals. Indeed, as Shanahan and Shanahan (Citation2017, p. 116) emphasise, the city is continuously in a ferment over its relationship with the past, as diverse communities negotiate and contest commemorative features ‘by memorializing, curating, visiting, vandalizing and repairing its remains, relics and ruins’, and erecting new memorials. Many post-WWII memorials moved away from figuration and towards abstract forms, often drawing onlookers into affective, sensual and embodied encounters, foregrounding the spatial relationships between viewer, memorial and location (Stevens & Sumartojo, Citation2015).

Accompanying the general demise of elite modes of placemaking is a broader shift, wherein commemorative forms align with what Atkinson (Citation2008, p. 385) terms the ‘democratisation of memory’: the decline of singular, ‘top-down’ memory production in favour of a ‘polyphony of voices that start to weave together a complex, shifting, contingent but continually evolving sense of the past and its abundant component elements’. Such memorials epitomize what Robertson (Citation2016, p. 10) calls ‘heritage from below’: installations that explicitly question dominant historical narratives, reflect ambivalence about national histories, memorialize neglected figures and events, or seek to open new routes to debating place identity and understanding the past. Examples include Nearamnew (2001), a complex, nuanced ground sculpture designed by Paul Carter at Federation Square, a popular public space and cultural precinct on the Yarra River. Commemorating Federation in 1901, Nearamnew’s inscribed stone slabs include fragmentary narratives attributed to an Aboriginal maker, colonist, prime minister, child, artist, migrant, builder, ferryman and visitor. Deliberately entangled and semi-legible, these multi-layered ‘vision texts’ give voice to distinctive, multi-layered visions of place, challenging ‘the monologic drive of white culture to write out the speech of the other’ (Rutherford, Citation2005, p. 7).

More explicitly, across the river to the south, Kings Domain Resting Place consists of a granite boulder installed over the buried remains of 38 Aboriginal people, returned back ‘to country’ in 1985 from containment in an ‘anthropological’ collection at the University of Melbourne (Edensor, Citation2020). And sited on the National Gallery of Victoria’s grounds, In Absence (2019) is a nine-metre timber tower that invites audiences to contemplate the fallacy of Terra Nullius. Created by Aboriginal artist Yhonnie Scarce with Edition Office architects, it affirms the longstanding history of Aboriginal design, industry and agriculture by referencing traditional eel traps, stone buildings and hollow smoking trees. Such creative practices have helped reinstall ignored, neglected or excluded identities in place.

However, while these practices of placemaking-via-memorialisation have decentred older modes of official commemoration, the figural memorial retains some salience in Melbourne. A bronze sculpture of eminent Aboriginal pastor, athlete and activist Sir Douglas Nicholls and his wife Lady Gladys Nicholls, also a respected Aboriginal activist, was installed in Parliament Gardens in 2007. Contemporary sculptures of popular entertainers, musicians and sporting stars are becoming more numerous. Realist sculptures of Australian runners, footballers and cricketers surround the Melbourne Cricket Ground, and busts of famous Australian tennis players feature at adjacent Melbourne Park, the national tennis centre. And the statue we investigate, Golden Head, is also figural – albeit in a uniquely non-prescriptive way.

In critiquing these earlier figural commemorative forms, Enloe (Citation1998, pp. 51–2) contends that it is overwhelmingly men ‘whose ideas and actions had been crucial shapers’ of commemorative practices, valorising selective heroic and patrician traits, and privileging certain historical events and processes in construing place identities. For example, few memorials mark the massacres perpetrated during Australia’s Frontier Wars. Recently, these imperialist, masculinist, racist and class-oriented sculptural memorials have been threatened, with specific historical events, regimes or persons challenged as politically unacceptable. Active since 2015, the Rhodes Must Fall campaign demands that statues of notorious colonialist Cecil Rhodes be removed from Cape Town and Oxford. In 2020, American Black Lives Matter campaigners targeted Confederate memorials and statues of slave-owners for perpetuating racism and white supremacist ideals, with dozens of statues toppled, burned or defaced . UK protesters dumped a statue of merchant slave-trader Edward Colston into Bristol Harbour, briefly mounting an unauthorised likeness of anti-racism protestor Jen Reid in its place, while in Belgium, King Leopold II, a monarch who reigned while savage colonialism was perpetrated, was dethroned from plinths in Antwerp and Ghent. Place, these activists contend, is tainted by association with such malign figures.

Similar campaigns are active in Australian cities. In 2020 ‘no pride in genocide’ was scrawled on a statue of Adelaide founder Colonel William Light (Slessor, Citation2020). In Queensland, a statue of Townsville founder Robert Towns was vandalised, with blood-red paint applied to its hands, while in Ballarat, Victoria, the words ‘homophobe’ and ‘pig’ were graffitied on bronze busts of former Liberal prime ministers John Howard and Tony Abbott. James Cook statues were vandalised in Sydney, while in Perth a statue of former governor James Stirling had its neck and hands sprayed red, and an Aboriginal flag painted over its inscription.

In Melbourne, police were dispatched to guard Captain Cook’s Cottage in 2014 after activists repeatedly graffitied the building. A Cook memorial in St Kilda was daubed with the words ‘No Pride’ on the eve of Australia Day 2018, and the following year painted with the slogan ‘A Racist Endeavour’, a pun on the name of Cook’s ship. A 1979 statue of colonial stockman Sir John Batman, at Queen Victoria Market, has been particularly controversial. Batman was notoriously brutal towards Aboriginal people, and in 1835 forged a disputed treaty with a group of Wurundjeri elders to acquire the land where Melbourne now stands. In October 1991, Aboriginal activists and supporters gathered around the statue. One participant tore up a copy of the treaty then staged a mock trial, accusing Batman of war crimes, theft, trespass, rape and genocide, with the crowd shouting ‘guilty!’ to each charge. The statue’s hands were coloured red to signify the bloodshed Batman sanctioned and perpetrated (Condon, Citationn.d.).

The tastes, styles, cultural values and motivations that once made such forms of memorialization commonplace in placemaking practices are now profoundly outmoded, incomprehensible or wholly forgotten. However, statues continue to haunt places today (Edensor, Citation2019). Despite the assaults on some controversial statues, most remain part of the mundane, everyday experience of the city – familiar but unremarkable landmarks, ignored and unloved.

The arrival, removal and resurrection of Golden Head

As official statues were being toppled, an unsanctioned monument installed in a Melbourne park elicited a sharply contrasting response. On the eve of Australia Day 2020, under cover of darkness, a mysterious object appeared in Northcote’s All Nations Park. Around 1.5 metres high, and bearing a solemn expression, the installation was a life-sized gold-painted head mounted on a concrete plinth. No explanatory plaque or interpretive aids offered any clues to its provenance or significance.

This cryptic new arrival sparked excited speculation amongst locals. Who did the statue represent? Who had installed it, and why? What did it mean? Constructed from poured concrete, with smooth skin and tousled hair, the statue had seemingly sprung up overnight from the clay-rich soil. All Nations Park is built on the site of a deep quarry and prolific brickworks that operated for a century before becoming a council tip in the late 1970s. Perched atop a hill in the park’s centre, the figure gazed resolutely westward towards the adjacent shopping centre, Northcote Plaza.

A modest cluster of no-frills shops, Northcote Plaza already had its own long-running fan club: the Northcote Plaza Appreciation Society (Citationn.d.), a loose online community that pays humorous tribute to their dowdy but beloved local fixture. With a mix of irony and enthusiasm, the forum celebrates the way ‘Norplaz’ bestows place distinctiveness on Northcote: a resolutely untrendy space, the shopping centre is an antidote to the slick, homogenous developments in other gentrified inner suburbs. Established in October 2007, at the time of writing the NPAS Facebook group has over 9000 members (or ‘Plazafarians’).

When photos of the statue were first shared within this online community – a group already primed to communicate creative, playful interpretations of their locale – fascination quickly spread. Members adopted the new arrival as their own. Androgenous but evidently inclining towards the masculine, it was dubbed ‘Golden Head’. Locals made pilgrimages to visit the statue, posed for photos, and joined debates about its provenance, meaning, identity and significance.

On 6 February, just 10 days after Golden Head’s enigmatic arrival, a resident posted an ominous online warning to the statue’s de facto fan club: ‘Something is happening!!’ An accompanying photo showed council workers clustered around the fallen icon. Supporters hurried to the scene. Council’s removal of Golden Head was documented in real time, with witnesses posting live updates: images and footage of a council ute driving away, the statue lying prone in the back, his head encased in bubble wrap.

Fans immediately rallied on Facebook, calling on Darebin Council to return the mysterious icon to his community. Some angrily accused Council of kidnapping and theft; others expressed sadness and loss. Council swiftly responded via its own public Facebook page, stating that the statue had ‘fallen over in the night’ and been damaged; it posed a safety risk, and was now in storage. This post drew more than 80 comments, the tone ranging from ironic to aggrieved. That afternoon, Council issued a second statement, acknowledging the community’s love for the statue, and promising it was being treated ‘with the utmost care and respect’. Staff asked the unknown creator to come forward, stating: ‘Council would love to chat with the artist/s to find a permanent home for the statue (the artist/s can remain anonymous).’ Admirers launched an online petition calling for Golden Head to be reinstalled in his ‘rightful place’, and one devotee wrote to the Prime Minister.

On 14 March, a larger, heavier replica of the original statue was covertly installed overnight. This version was bolted to a concrete slab. The community enthusiastically hailed Golden Head’s return, with visiting fans posting a new swathe of photographs – although some were unhappy that it looked slightly different from its predecessor. This time Council moved quickly: the next day park-goers posted images of the statue cordoned off with safety tape, reporting that council staff were back onsite. The following afternoon Council removed the statue with a crane, citing safety risks due to unsteady footings. When a bystander asked why Council was taking Golden Head away, park staff allegedly replied, ‘They are not sure what he represents.’ Council posted another statement on Facebook, the tone less jovial now, again urging the artist/s to come forward:

The City of Darebin understands the community sentiment for the statues, but … does not encourage unauthorised art or graffiti of our streets, parks and gardens. This is why we have begun the art acquisition process, to review the two statues through a professional art lens and assess them against Council’s art collection and commissioning priorities (16 March).

The statue’s removal again drew a heated online response from locals, who demanded it be reinstated. With a local resident acting as go-between, council staff and the anonymous artists engaged in email dialogue and negotiated a formal agreement. On 26 June, the original Golden Head was reinstalled, with a plaque and reinforced foundations. It received a hero’s welcome. Council announced it would remain in place for a year before being auctioned, with proceeds going to a local homelessness charity, at the artist’s request. The plaque provided minimal context, preserving the mystery. Council posted a Facebook update:

The artists did provide a statement about the work. But they requested [it] was kept confidential. They would like the statue to remain open to interpretation, and for visitors to continue to bring their own ideas and narratives to the work (26 June).

Playing with Golden Head: place-making through collective creativity

From its first appearance, Golden Head was embraced by Northcote residents. A community of practice rapidly formed, contributing to a powerful placemaking process grounded in mutual enthusiasm, the sharing of ideas and images, and a repertoire of jokes, stories and engagements (Courage, Citation2021). The widespread sharing of creative responses via social media helped sediment the statue as a popular signifier of Northcote’s identity. An outpouring of images, comments, speculation, quips, stories and discussions about Golden Head appeared on the NPAS Facebook page. Shared within this existing online community, these posts fuelled further interactions between locals, park users, the statue, and All Nations Park. Through this ongoing collective process, residents endowed the statue with its own mythology, argued for its legitimacy, and helped embed its presence in place.

Online responses constituted a mix of text-based and visual content. Created by an overlapping group of park visitors, residents and NPAS Facebook group members, these responses were instrumental in consolidating Golden Head’s appropriation as a cherished local symbol. Analysing this social media content, we identify five key themes through which Golden Head is represented in celebratory, comic and proprietorial ways.

Bearing witness and making memories: narrating Golden Head’s life story

First, a series of textual and visual artefacts document the major ‘life events’ through which Golden Head came to occupy his position in All Nations Park: his sudden appearance, his expulsion, the resultant empty space, his subsequent reincarnation, his successor’s removal (see ), new footings being laid for his return, and his official reinstallation. In marking such milestones, these digital expressions comprise a communal narration of Golden Head’s ‘life story’. People shared images and discussions of significant events as they unfolded, endowing the statue with a narrative arc and situating him within both the chronology of their own lives and the collective life of the community. This resonates with Bellah et al.’s (Citation1985) assertion that communities are bound together by shared memories, by the stories they tell and retell.

Importantly, this ‘documentation’ also constitutes a form of bearing witness, a mode of information-sharing that inspired a growing sense of ownership and catalysed further responses. These ‘witnessing’ practices were initially deployed to mobilize community action: as a fleet of council vehicles arrived to remove Golden Head, people posted images and footage, imploring more witnesses to document events in person. Drawn into recording these unfolding dramas, Northcote residents thus became protectors of the artwork:

If anybody is on the ground right now. Apparently Gold Head is being loaded into a council truck as we speak! If somebody could get some footage or pics of our Lord’s exit I would be very appreciative.

Any members with drone capability able to get a clear image?

Omg … they have brought out the spades and a giant roll of bubble wrap

They are loading him into the back of a truck right now. God this is terrible.

There were 7 men and 6 red witches’ hats and a young lady crying.

Should we have a funeral? (all posted 6 February)

Could Golden Head be coming back?! There’s a brand new footing being laid on the top of the hill in All Nations Park. (23 June)

Myth, mystery and meaning: co-creating Golden Head’s backstory

A second category of social media posts speculate about the enigmatic statue’s provenance, identity, purpose and meaning. These responses seek to creatively construct Golden Head’s ‘backstory’. Who made the statue, and why did they place it in the park? Who and what does it represent? Some users attributed it to the Australian Cultural Terrorists, a guerrilla art group that claimed responsibility for the 1986 theft of Picasso’s Weeping Woman from the National Gallery of Victoria. Others compared its creators to anonymous UK street artist Banksy. Others posted images of Golden Head alongside public figures, debating the resemblance: was the figure meant to represent David Bowie, Lou Reed, Captain Spock or Justin Timberlake? Did it resemble Australian actor Vince Colosimo, 1990s TV host Dylan Lewis, or Aboriginal activist Sir Douglas Nicholls? Was it a homage to Egg Boy, the teenager who cracked an egg on the head of racist politician Fraser Anning, or a memorial to Tyler Cassidy, the 15-year-old boy fatally shot by police in All Nations Park in 2008?

In developing these conjectural strands, many users framed Golden Head as a community protector, heroic ruler or benevolent deity. Some images capture the statue from an elevated standpoint, suggesting a beneficent or custodial role, while others feature grateful supplicants kneeling at his feet. Group members often comically but affectionately parody religious language and tropes:

He was the GOD of Northcote Plaza! (6 February)

Like Phoenix from the ashes! He has risen! (22 February)

The second coming. (14 March)

I feel like everything is going to be alright, now that our Patron Saint has returned. (15 March)

All hail our god. Let him come back (again) and help lead us through these dark times (17 March)

Introducing the next generation to our lord and saviour (27 June, with photo of young baby ‘meeting’ Golden Head)

The ancient Israelites began worshipping a golden calf when Moses left them for 40 days and for that they were condemned by god. I reckon if they’d worshipped a golden head they would have been right though (27 August)

I, humble supplicant, and pilgrim, give thanks this day to Our Beloved Golden Head, on the Temple Mount of All Nations, for watching over us with benevolence and humour towards all things daggy and divinely disturbing that is our Plaza. (29 August)

As Melburnians endured prolonged, strict lockdowns during Covid-19’s first wave, pandemic references formed another sub-theme, with park users recruiting the statue to help spread public safety messages. Often accompanied by photographs of Golden Head wearing a facemask (see ), these comments reinforce his imagined role as exemplary community protector, an ambassador for compliance with sometimes unpopular health measures:

The hero we need during this time. No lungs to cough on us. No hands to touch his face. Just a good solid gold head to worship. (17 April)

It’s a shame about this COVID thing, would’ve been great to have a Golden Party for Golden Head’s return (30 May)

The hero returns bringing fresh hope to the northern lands! GH, please protect our suburb from the pandemic cluster! (26 June)

Good to see our friend on the hill is keeping up with the Rona safety measures. Good man!! (14 July)

Be more like Golden Head. Stay safe and wear a mask plaza people! X (23 July)

Other commentators explicitly embrace the statue’s playful ambiguity:

Why can they not let go of this insatiable need to *know*? (26 February, responding to media speculation about statue)

Art can be organic and this one has captured the imagination of us locals (16 March)

Yes, we all attach our own meanings to objects. I believe the golden head is a great source of inspiration for our community! (27 August)

Local Mayor Susan Rennie echoed these notions, acknowledging that the statue’s mystery elevated its worth: ‘People going to be photographed with Golden Head, dressing it up, creating memes, hypothesising about who it could be … shows the value of that artwork. It brought people together, it brought joy to people’. Furthermore, she enters into the creative speculation herself:

That’s no accident, that Golden Head occupies that very dominant position in the park [atop the hill]. He’s looking out, and naturally that raises questions – what is he looking at? … There’s one theory that it’s someone looking out over the real estate they will never be able to afford to buy into. Another theory is that it’s an Aboriginal person looking out over their stolen land.

Affection, affiliation and ownership: caring for Golden Head

A third category of response centres on emotional or affective responses to Golden Head. The vast majority of commentators express positive feelings towards the statue, and many declared sadness, even grief, over its removal. These affective responses are entwined with an anthropomorphic impulse: a tendency to see the statue as sentient and capable of emotion. Most users refer to the statue as ‘he’, and those using the pronoun ‘it’ are sometimes corrected. Some call him ‘Golden Boy’, or ‘GB’ for short, and several address the figure directly. These attributions of sentience are entangled with expressions of affection, reverence and care, often spliced with humour. The following quotes focus upon his cherished presence, a sense of loss following his removal, a longing for his return, familial relationality and physical contact, and concerns about his condition:

Wasn’t he always there in our hearts from the beginning?

So many memories. Goodbye Gold brother

He was the father we never had. He was the brother everybody would want. He was the friend everyone deserved. ☹ (all 6 February)

Can we get a proof of life photo? (10 Feb, after statue’s removal)

He was lying there peacefully on Wednesday (10 March, with photo of damaged statue)

Poor old Golden Head is looking pretty banged up. Big crack on his neck and lots of chipped bits. I don’t remember noticing that before – is that new? (25 June, with photo of damage: see )

Went up there today to bestow the love. There was a line up. (1 July)

To whoever was looking out for Golden Head’s eyes today, thanks! Seeing him being so well cared for brought a smile to my face! (2 August, with photo of statue wearing sunglasses: see )

At least we can still hug statues. (20 August)

Images of Golden Head playing ‘dress-ups’ (see ) reinforce these affiliative impulses. These playful, creative responses signal the statue’s fluid identity and honorary personhood, while underpinning its status as an object of affection. Golden Head has been adorned with a cape, denim jacket, sunglasses, scarves, a plastic Viking helmet, surgical masks, and an Aboriginal flag. Accompanied by the slogan, ‘Always Was, Always Will Be [Aboriginal land]’, signifying that Australia has been home to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people for millennia, this framing of the figure as Indigenous sits in striking contrast with the aforementioned activist campaigns to dethrone disputed commemorative statues. To fill the void left by Golden Head’s removal, one admirer posted a memorial slideshow depicting these diverse outfits. These photographic practices are acts of affiliation and ownership. They demonstrate how people produce, record and freely share their creative relationships with the statue.

Animating bonds with place: Golden Head as a fulcrum for belonging

A fourth category of response emphasises Golden Head’s embeddedness in place, and the statue’s role in strengthening community belonging. His presence has drawn additional visitors to All Nations Park, reinforced connections between the park and adjacent Northcote Plaza, provoked discussion of local history, catalysed a rich array of place-based associations, and provided a landmark and focal point for creative interactions between community members.

In animating and strengthening bonds with place, the guerrilla artwork has also catalysed communal belonging. Golden Head’s status as a treasured signifier of place is forged through in-person visits, via his role as a tourist attraction, through historical and geological connections to place, in calls to reclaim his ‘rightful’ place, and in overt statements about how the statue has mobilised a shared sense of place:

I took my walking group up there this morning and the mysterious statue with its latest adornment was much admired (29 January)

Putting All Nations Park and the Plaza on the map … (31 January)

Some say his foundations go all the way down to the huge magma chamber below Northcote plaza. (2 February)

He’s a symbol of the People’s Republic of Northcote

Golden Head already has determined his long term home … Please return this icon to its rightful home atop Mount Northcote

Golden head belongs to Northcote on the mount! … We want him home in all his splendour! … he belongs in the ‘bosom’ of our community …

Look how he brought a community together. I have actually only been living in Northcote since October and I have felt more connected to my environment more than I did back at home in the UK. (all posted 6 February)

Golden Head surveying his domain. ‘And Alexander wept, seeing as he had no more worlds to conquer’ (25 June, with photo of statue looking over Northcote)

Interesting to note the choice of plinth upon which our Golden Head rests. Hewn of the very rock that encircles Him, the rough chisel technique reflects Northcote’s working class origins. (25 June)

I hope the person that buys him at auction next year stipulates that he remains in place, as Lord of the Plaza (26 June)

It’s a pilgrimage that every Darebin citizen should take at least once in their lives (25 July)

These place-specific assertions are reinforced by multiple documentary-style ‘portrait photographs’ depicting Golden Head from various angles, at different times of day and night. Some images adopt a close-up perspective, whereas others capture him gazing across a vista from his elevated position; some look upwards at the figure from ground level, others display his silhouetted form from afar. These divergent viewpoints collectively sediment Golden Head in place; he is repeatedly envisioned as an integral element within the local landscape.

Golden Head also appears in numerous selfies and group photos with friends, family and pets. In these images, residents and figure align in compositions that stage both as belonging to place. One disciple kneels before the statue, hands raised in prayer; others hug him, kiss his cheek, or stand smiling at his side. These postures chime with Larsen’s (Citation2005, p. 425) account of tourist photography as a performed practice that ‘revolves around staging and posing intimate social life and capturing moments of bodily actions taking place in and on various – ordinary as well as extraordinary – material stages’. Here, however, this unfolds in the place of belonging, rather than in the space of the Other.

Weilenmann and Hillman (Citation2020, p. 44) note that popular discourse often derides the selfie as a ‘vapid and narcissistic photographic genre’. However, images of visitors posing with Golden Head reinforce their claim that the selfie can also be ‘a performed and embodied practice that is sensitive to the local context in which it is produced’ (Weilenmann and Hillman, Citation2020, p. 56). The photographs also refute claims that social media settings generate the circulation of placeless images, contributing to a hollowing-out of the local. They resonate with Mosconi et al.’s (Citation2017, p. 960) insistence that social networking is ‘often a fundamentally local and situated practice’ through which ‘civic discussions [take] place about sites of local interest’. Indeed, Golden Head’s reception demonstrates how Facebook in particular can serve as a local infrastructural network, affirming ‘the capacity of social media to bring neighbours closer together, create closer ties, and increase civic engagement through novel cooperative configurations’ (Mosconi et al, Citation2017, p. 962).

Relatedly, Sinanan (Citation2020, p. 52) argues that social media posts often revolve around place-based values, codes and knowledge, ‘influenced by locational and contextual socialities’; similarly, Pink and Hjorth (Citation2012) see the production of such images as entangled with an ‘emplaced visuality’. Elements of place are continuously reconstituted by both corporeal movements and the circulation of ideas and images across social media, which in turn may encourage further site visits. Here, relationships between people and place are strengthened as ‘the electronic is superimposed on to the geographic in new ways’ (Pink & Hjorth, Citation2012, p. 146). By directing attention to specific local elements, these digital interactions shape new mobile routines around which everyday ‘place-ballets’ (Seamon, Citation1980) are co-ordinated. These engagements reverberate between digital space and physical place, as ‘the paths, interactions and connections that people form are woven and remediated through intersecting arrays of new media’ (Crang et al., Citation2007, p. 2419). This resonates with Ashmore’s (Citation2013, p. 271) suggestion that community-themed Facebook groups ‘may constitute a hybrid space’ wherein virtual-world interactions add ‘details to places and social networks in the physical space’ that the community inhabits.

Sharing a laugh: Golden Head as a catalyst for jokes, memes and play

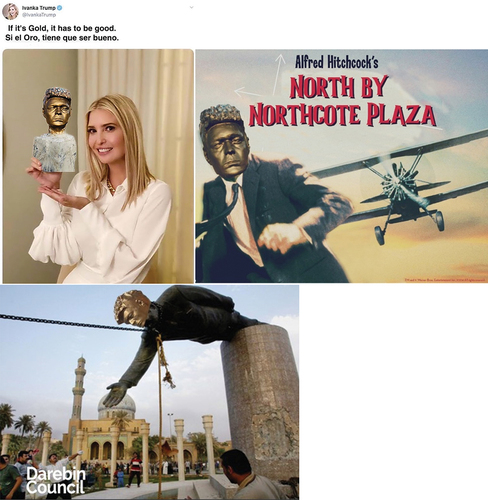

We have noted the prevalence of humour in user-generated images and texts about Golden Head, and this fifth category of response infuses all the categories discussed above. This comedic tendency reflects the ethos of the NPAS Facebook group, characterised by a shared fondness for humour, irony and absurdity. Members routinely exchange banter, wisecracks, running jokes and laugh emojis. With Golden Head, this humour reaches its most inventive expression in humorous memes (see ), some of which have been printed on coffee cups and t-shirts. In one such intertextual artefact, Golden Head is wittily superimposed onto a poster of an Alfred Hitchcock thriller, retitled Northcote by Northwest. One meme shows an image of Ivanka Trump holding a model of the statue, with the text, ‘If it’s gold, it has to be good’, a spoof of her advertising campaign for Goya beans; another recycles the renowned photograph of a toppled Saddam Hussein statue, the local icon’s head replacing that of the Iraqi dictator, referencing the local council’s toppling of Golden Head. In a nod to heroic solidarity amongst underdogs, one meme references the 1969 film starring Kirk Douglas: ‘I am Spartacus. I am the Golden Head artist.’

These memes complement comical photographs of the statue ‘dressed up’ or surrounded by worshippers, creating opportunities to produce, mimic and remix absurd juxtapositions within a shared sphere of recognition. The vernacular, surreal and amusing images, and the accompanying wisecracks and jokes, critically undercut the reified cultural meanings of dominant commemorative forms that seek to inscribe established meanings on place over time (Weitz, Citation2016). Such ironic rejoinders affirm that ‘to laugh is to know the world in a different way’, and to rebuke accepted notions of common sense (Emmerson, Citation2016, p. 722). Equally importantly, as Ridanpää (Citation2014, p. 704) submits, humour ‘possesses a shared social purpose for helping group cohesion and social bonding, as well as creation and preservation of group identities’. As a shared object of affectionate irony and laughter, Golden Head exemplifies how a politics of place can be centred on ‘the mobilization of affective experiences’ (Ridanpää, Citation2014, p. 705) that consolidate a sense of collective belonging.

Further, Golden Head’s capacity to instigate these creative pleasures underlines how rarely urban spaces enable unfettered, spontaneous play. While official memorials are typically designed to demand reverence, a broader preoccupation with aesthetics and functionality tends to downplay the ludic potential of urban space. Unlike many touristic, architectural or heritage sites, where selective text and reified form close down interpretation, Golden Head’s meanings are open to imaginative speculation; consequently, the site has become an exemplary place of ludic creativity. Lacking normative assignations, people can make use of Golden Head however they choose. The installation fosters ‘democratic openness’ (Maddrell, Citation2009, p. 681), its inscrutability encouraging abundant playful practices.

While play is often dismissed as infantile or frivolous, these humorous engagements attest that it can be ‘a vehicle for becoming conscious of those things and relationships that we would otherwise enact or engage without thinking’, generating ‘sparks of insight and moments of invention, which present us with ways to be “otherwise”’ (Woodyer, Citation2012, p. 322). As Stevens contends, play tends to occur when ‘people step beyond instrumentality, compulsion, convention, safety and predictability to pursue new and uncertain prospects’ (2007, p. 196). Golden Head’s novel indeterminacy has spawned a wealth of playful, creative practices that strengthen a collective sense of place-belonging.

Critically, these dynamic practices of collective placemaking largely occurred during Melbourne’s extended 2020 COVID-19 lockdowns. Movement restrictions, a loss of usual routines and the need for daily exercise prompted residents to explore their neighbourhoods and (re)discover previously overlooked aspects of their local environments, including green spaces, place-signifiers and idiosyncratic features. In this context, people are investing time in fostering local interactions wherein they ‘take their social life online and animate their neighbourhoods’. For Cara Courage (Citation2021: 2), this unexpected reacquaintance with neighbourhood realms such as All Nations Park is part of a ‘relocalism’ that reaffirms the importance of place and community.

Golden Head’s story remains open-ended. On 6 December 2020, the second statue was beheaded by vandals, his head stolen; fans expressed sadness, disbelief and anger on the NPAS Facebook page. On 24 January 2021, an apparently female Golden Head materialised on her predecessor’s plinth, receiving an enthusiastic online welcome. That same weekend an identical female head was installed on Bin Chicken Island, Merri Creek, in the nearby suburb of Coburg, while adifferent golden female statue covertly placed in Bulleen’s Heide Sculpture Park, further east, was swiftly removed. On 5 August 2021, the original Golden Head was auctioned online, attracting an anonymous winning bid of AU$3200 (a planned live auction and community party were cancelled due to Covid-19). At the artist’s request, th proceeds were donated to a refuge for Aboriginal women and children escaping family violence (32 Auctions, 2021). Council removed the female Golden Head from All Nations Park later than month. The original statue’s current whereabouts remain unknown.

Conclusion: challenging, toppling or playing with statues

At a time when commemorative statuary is increasingly subject to neglect, critique and assault, it is instructive to explore why Golden Head, a statue that bears a formal resemblance to such memorials, has been so enthusiastically embraced by Northcote’s residents. We contend that the creative appropriation and humorous celebration of Golden Head’s presence in All Nations Park casts new light on the strange resilience of figurative statues. While an outmoded form of commemoration, they largely persist; the values they embody have not yet been exorcised. Frank and Ristic (Citation2020, p. 556) conceive such memorials as forms of territorialization that ‘stabilize spatial boundaries and inscribe fixed place identities often exclusive of ‘others”’, while their removal acts to deterritorialize space. These figures rarely invite interpretation, let alone play; their imposing stances and accompanying texts are encoded with notions of heroism, leadership, philanthropy and nobility.

Traditional statues radiate authority through their lofty position, while their weighty materiality embeds them in the landscape. Their ubiquity has largely insulated them from critical interrogation, as citizens rarely notice them. Despite this, such statues are increasingly under threat, as citizens question their subjects’ mooted benevolence or heroism, highlighting their participation in colonial genocide, war crimes, slavery and other violent and repressive institutional practices.

Critics complain that toppling statues is an act of destructive vandalism that erases history. Yet as historian David Olusoga (Citation2020) points out in response to the recent felling of slave-owner Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol, ‘This is not an attack on history. This is history’. Similarly, Frank and Ristic (Citation2020, p. 553) claim that such actions do not constitute the ‘killing of memory’, the erasure of the past, but rather seek to unpack, deconstruct and subvert troublesome heritage and open it up to new meanings. These campaigns are entwined with political struggles for more inclusive recognition of marginalised, dispossessed and subaltern groups who lack an officially sanctioned presence in the urban landscape.

At the University of Cape Town, a Cecil Rhodes statue has prompted ‘occupation, appropriation, modification and transformation’ by students staging in-situ creative ‘performances and dialogues’, daubing graffiti, placing banners, wrapping the statue in rubbish bags and pouring paint over it (Frank & Ristic, Citation2020, p. 553). A coalition of Australian artists, curators, academics and First Nations leaders published an open letter to the City of Sydney in July 2020, requesting that a Captain James Cook statue be relocated from Hyde Park to a public museum. In September 2020, activist arts collective The Statue Review affixed unsanctioned plaques to two colonial statues in Perth. Highlighting Septimus Roe and James Stirling’s participation in the 1834 Pinjarra Massacre, in which up to 80 Noongar men, women and children were murdered, the plaques state: ‘He belongs in a museum. Not on our streets’ (Butler, Citation2020). As we have discussed, campaigns to remove Melbourne statues have been equally intense (Holsworth, Citation2017).

While these critical engagements have a creative dimension, they radically contrast with the celebratory, affectionate and humorous practices sparked by Golden Head. Northcote local Sean Whelan, who liaised between Council and the statue’s anonymous creator/s during negotiations to reinstall it, articulated this divergence:

Everywhere around the world we’re tearing down statues – and I’m actually for that. The beauty of [Golden Head] is because it’s anonymous it doesn’t have a political agenda; it doesn’t have anything. It’s whatever you want to project on it, and that’s the vital difference. I think that’s why people love it so much too. It’s that mystery. Because then you can fill in the gaps with your own imagination.

Darebin’s then-Mayor Susan Rennie articulated similar ideas:

It was the stories surrounding it, the myth, the mystery – that whole process was a big part of what makes it so special to the community … So often, statues are created to immortalize powerful white men [but] I’ve not heard anyone say that Golden Head is supposed to represent someone in power. Here is a statue that could be any one of us … It has a somewhat androgenous look. Also, its skin is gold, not white or black … Everyone can see in that statue what they want to. Everyone can interpret for themselves what it means.

While Golden Head’s enigmatic qualities render him somewhat unique, he can be situated within an emergent lineage of playful and unsanctioned engagements with statuary and memorials. Other figurative statues have occasionally garnered creative and affectionate responses. In Australia, Eliza, installed in 2007, a swimmer installed in the Swan River to commemorate Perth’s demolished Crawley Baths, has become an ever-evolving ‘canvas’ for local guerrilla art actions. The Seattle installation Waiting for the Interurban (1978), a cluster of figures waiting for a bus, is frequently targeted for dress-up pranks (Harris, Citation2011). And guerrilla sculptor Mihály Kolodko instals tiny bronze statues in mystery locations around Budapest. Fans swap tips on finding the figures, debate their meanings, dress them up and share photos online (AFP, Citation2020).

Chang (Citation2019) questions whether unauthorised and grassroots public art has the power to transfigure place and sense of belonging. We emphatically claim that Golden Head offers a concrete example of this transformative power. In the over-regulated contemporary city, where spaces are monitored, governed and assigned specific functions, the inscrutable and mysterious are apt to be excluded or excised. Yet people delight in encountering the unexpected, whether as inexplicable vestiges from the past or sudden intrusions into the present. Esoteric elements in the urban landscape have a unique power to stimulate curiosity, playfulness, imagination and conjecture – especially in contrast to the often-homogeneous waterfronts, shopping malls and cultural quarters that gesture toward placemaking, but merely reproduce a serial monotony.

Guerilla artworks align with the improvisational, contingent placemaking practices of tactical urbanism, providing a ‘radically democratic counterweight to institutional systems, whether state-driven or market-dominated’ (Brenner, Citation2021: 320). Typically unsigned and unsanctioned, these works are particularly effective catalysts for creative responses. Installed covertly by unknown persons, Golden Head exemplifies these qualities, while playfully subverting the code of reverence associated with traditional ‘great man’ statues: coated in gold and elevated on a plinth, he was accorded the trappings of dignity, yet no-one is certain who or what he represents. His enigmatic origins and unfixed identity lent him a generative force. Unauthorised and open-ended, he sparked a collective sense of intrigue and speculation, inviting a proliferation of light-hearted responses. Golden Head is a symbol without a referent, an icon without a pre-determined meaning, a tabula rasa onto which the community can project its own playful imaginings. In contradistinction to the reified, authoritative narratives of traditional figural memorials (Toolis, Citation2017), here a plurality of voices has co-produced inclusive, improvisational stories and loose performances via everyday social interactions, both online and in situ. In eliciting an outpouring of jokes, memes, stories, photographs and other creative responses, this enigmatic object has strengthened and renewed a collective sense of place and belonging.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Melbourne poet and performer Sean Whelan and former City of Darebin Mayor Susan Rennie for their valuable and generous input. We also thank Jolynna Sinanan for her excellent advice, two anonymous reviewers for their wise comments, as well as the editor for his support.

References

- AFP. (2020). Budapest’s Banksy disciple sparks treasure hunts and nostalgia. France 24, 21 January [WWW document]. URL https://www.france24.com/en/20200129-budapest-s-banksy-disciple-sparks-treasure-hunts-and-nostalgia (accessed 21 October 2020).

- Ashmore, R. (2013). ‘Far isn’t far’: Shetland on the internet. Visual Studies, 28(3), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2013.829995

- Atkinson, D. (2008). The heritage of mundane places. In B. Graham & P. Howard (Eds.), The Ashgate research companion to heritage and identity. Ashgate.pp. 381–395

- Bellah, R., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W., Swidler, A., & Tipton, S. (1985). Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life. University of California Press.

- Brenner, N. (2021). Is tactical urbanism an alternative to neoliberal urbanism? Reflections on an exhibition at MoMA. In C. Courage (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of placemaking. Routledge.pp. 113–128

- Butler, G. (2020) Australian activists give racist statues new plaques to highlight colonial violence. Vice World News, 16 October [WWW document]. URL https://www.vice.com/en/article/4ayez3/australian-activists-give-racist-statues-new-plaques-to-highlight-colonial-violence (accessed 19 October 2020).

- Chang, T. C. (2019). Writing on the wall: Street art in graffiti-free Singapore. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 43(6), 1046–1063. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12653

- Condon, B. (n.d.) John Batman’s statue tried for war crimes. The Koori History Website Project: Information on Black Australia’s 240-year struggle for justice [WWW document]. URL http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/resources/story10.html (accessed 12 July 2020).

- Courage, C. (2021). Introduction: What really matters: Moving placemaking into a new epoch. In C. Courage (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of placemaking. Routledge.pp 1–8

- Crang, M., Crosbie, T., & Graham, S. (2007). Technology, time–space, and the remediation of neighbourhood life. Environment & Planning A, 39(10), 2405–2422. https://doi.org/10.1068/a38353

- Drozdzewski, D., De Nardi, S., & Waterton, E. (2016). The significance of memory in the present. In D. Drozdzewski, S. De Nardi, & E. E. Waterton (Eds.), Memory, place and identity: Commemoration and remembrance of war and conflict. Routledge.pp. 1–16

- Edensor, T. (2019). The haunting presence of commemorative statues. Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organization, 19(1), 53–76.

- Edensor, T. (2020). Stone: Stories of urban materiality. Palgrave.

- Emmerson, P. (2016). Doing comic geographies. Cultural Geographies, 23(4), 721–725. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474016630967

- Enloe, C. (1998). All the men are in the militias. In L. Lorentzen & J. Turpin (Eds.), The women and war reader. New York University Press.50–62

- Frank, S., & Ristic, M. (2020). Urban fallism. City, 24(3–4), 552–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2020.1784578

- Harris, J. (2011). Guerilla art, social value and absent heritage fabric. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 17(3), 214–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2010.535212

- Hoelscher, S., & Alderman, D. (2004). Memory and place: Geographies of a critical relationship. Social and Cultural Geography, 5(3), 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464936042000252769

- Holsworth, M. (2017) Statues wars 2017. Melbourne Art Critic, 25 October [WWW document]. URL https://melbourneartcritic.wordpress.com/2017/10/25/statues-wars-2017/ (accessed 13 July 2020).

- Larsen, J. (2005). Families seen sightseeing: Performativity of tourist photography. Space and Culture, 8(4), 416–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331205279354

- Maddrell, A. (2009). A place for grief and belief: The witness cairn at the Isle of Whithorn, Galloway, Scotland. Social and Cultural Geography, 10(6), 675–693. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360903068126

- Mosconi, G., Korn, M., Reuter, C., Tolmie, P., Teli, M., & Pipek, V. (2017). From Facebook to the neighbourhood: Infrastructuring of hybrid community engagement. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 26(4–6), 959–1003. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-017-9291-z

- Northcote Plaza Appreciation Society. (n.d.). Public group. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/groups/6111773948/search?q=gold

- Olusoga, D. (2020) The toppling of Edward Colston’s statue is not an attack on history. It is history. The Guardian, 8 June [WWW document]. URL https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jun/08/edward-colston-statue-history-slave-trader-bristol-protest (accessed 22 August 2020).

- Pink, S. (2013). Doing visual ethnography: Images, media, and representation in research. Sage.

- Pink, S., & Hjorth, L. (2012). Emplaced cartographies: Reconceptualising camera phone practices in an age of locative media. Media International Australia, 145(1), 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X1214500116

- Poulsen, S., Vigild, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (2018). Social media as semiotic technology. Social Semiotics, 28(5), 593–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2018.1509815

- Price, P. (2010). Cultural geography and the stories we tell ourselves. Cultural Geographies, 17(2), 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474010363851

- Ridanpää, J. (2014). Geographical studies of humour. Geography Compass, 8(10), 701–709. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12159

- Robertson, I. (2016). Heritage from below: Heritage, culture and identity. Routledge.

- Rutherford, J. (2005). Writing the square: Paul Carter’s Nearamnew and the art of federation. PORTAL Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies, 2(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.5130/portal.v2i2.94

- Seamon, D. (1980). Body-subject, time-space routines, and place-ballets. In A. Buttimer & D. Seamon (Eds.), The human experience of space and place. Croom Helm.pp. 148–165

- Shanahan, M., & Shanahan, B. (2017). Commemorating Melbourne’s past: Constructing and contesting space, time and public memory in contemporary parkscapes. In L. McAtackney & K. Ryzewski (Eds.), Contemporary archaeology and the city: Creativity, ruination, and political action. Oxford University Press. pp. 111–126

- Sherman, D. (1999). The construction of memory in Interwar France. University of Chicago.

- Sinanan, J. (2020). ‘Choose yourself?’: Communicating normative pressures and individual distinction on Facebook and Instagram. Journal of Language and Sexuality, 9(1), 48–68. https://doi.org/10.1075/jls.19004.sin

- Slessor, C. (2020). Statue of Adelaide founder Colonel William Light again vandalised with slogans. ABC Radio Adelaide, 25 June [WWW document]. URL https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-06-25/colonial-figure-statue-vandalised-in-adelaide-for-second-time/12390720 (accessed 13 July 2020).

- Stevens, Q. (2007). The ludic city: Exploring the potential of public spaces. Routledge.

- Stevens, Q., & Sumartojo, S. (2015). Introduction: Commemoration and public space. Landscape Review, 15(2), 2–6.

- Toolis, E. (2017). Theorizing critical placemaking as a tool for reclaiming public space. American Journal of Community Psychology, 59(1–2), 84–199. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12118

- Vaughan, G. (2013) The cult of the queen empress: Royal portraiture in colonial Victoria. Art Journal of the National Gallery of Victoria, 50 [WWW document]. URL: https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/the-cult-of-the-queen-empress-royal-portraiture-in-colonial-victoria/ (accessed 7 September 2020).

- Weilenmann, A., & Hillman, T. (2020). Selfies in the wild: Studying selfie photography as a local practice. Mobile Media and Communication, 8(1), 42–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157918822131

- Weitz, E. (2016). Humour and social media. The European Journal of Humour Research, 4(4), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.7592/EJHR2016.4.4.weitz

- Woodyer, T. (2012). Ludic geographies: Not merely child’s play. Geography Compass, 6(6), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2012.00477.x