ABSTRACT

Escaping war and persecution during the twenty-tens, over two-million displacees made life-risking journeys into Europe. Trauma continued for those who managed to cross borders and reach new havens: grappling with migration systems, searching for decent housing, and striving for social integration. This article presents empirical findings of a multi-modal participatory mapping project conducted with refugees and asylum seekers in Southwest England, and highlights the impact of memory and deep creative mapping on the spatial practice of making-home in forced displacement. The resulting maps embody spaces of recovery; memoryscapes revealing synergies between the constructs of memory and the concept of home in exile. The project asks how a creative participatory method of mapping home through memory reconsolidation can ameliorate the trauma of displacement and aid the re-making of home.

Resumen

Escapando de la guerra y la persecución durante la década de 1920, más de dos millones de desplazados realizaron peligrosos viajes a Europa. El trauma continuó para quienes lograron cruzar las fronteras y llegar a nuevos refugios: lidiar con los sistemas de inmigración, buscar una vivienda digna y luchar por la integración social. Este artículo presenta los hallazgos empíricos de un proyecto de mapeo participativo multimodal llevado a cabo con refugiados y solicitantes de asilo en el suroeste de Inglaterra, y destaca el impacto de la memoria y el mapeo creativo profundo en la práctica espacial de la creación de un hogar en el desplazamiento forzado. Los mapas resultantes incorporan espacios de recuperación; paisajes de memoria que revelan sinergias entre las construcciones de memoria y el concepto de hogar en el exilio. El proyecto pregunta cómo un método participativo creativo de mapeo del hogar a través de la reconstitución de la memoria puede mejorar el trauma del desplazamiento y ayudar a reconstruir el hogar.

Résumé

Pour échapper à la guerre et à la persécution, plus de deux millions de personnes déplacées ont entrepris le dangereux voyage vers Europe pendant les années 2010. Les traumatismes ont continué pour ceux qui ont réussi à traverser les frontières et atteindre une terre de refuge: la confrontation aux systèmes de migration, la recherche d’un logement acceptable, et la bataille pour l’intégration sociale. Cet article présente les observations empiriques d’un projet de cartographie participative multimodale mené auprès de réfugiés et de demandeurs d’asile dans le sud-ouest de l’Angleterre, et souligne l’impact de la mémoire et de la profonde créativité de la cartographie sur la pratique spatiale de la fabrication de foyer dans les déplacements forcés. Les cartes qui en ont été créées représentent des espaces de récupération, des espaces-souvenirs révélant des synergies entre les structures mnémoniques et le concept du foyer pendant l’exil. L’étude pose cette question: comment une méthode de création participative pour cartographier le foyer par le biais de la consolidation des souvenirs peut atténuer le traumatisme du déplacement et assister à la re-fabrication du foyer.

Introduction

The asylum system in the UK leaves vulnerable displacees in precarious situations, waiting for months and sometimes years until a case is made and assessed against criteria derived from the UN Convention for Refugees. The UK has one of the largest migration detention systems in Europe (Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, Citation2020). After detention comes further displacement through a national (but restrictive) scheme running across volunteer dispersal cities. The trauma continues as displacees grapple with the UK migration system, search for decent accommodation and attempt social integration (Darling, Citation2016; Home Affairs Committee, Citation2017). A similar pattern has been documented across Europe (Robila, Citation2018). Besides physically visible trauma to the body, psychological trauma becomes amplified, while recovery towards wellbeing is often hampered by the mutually reinforcing effects of constrictive asylum policies. For displacees, this trauma is further exacerbated by spatio-cultural rootlessness and new urban environments unmediated by familiar social networks (Rishbeth et al., Citation2019). Trauma can become a ‘lifelong problem’ affecting the function and structure of the brain, alongside ‘neuropsychological components of memory’ (Bremner, Citation2006, p. 455). This experience of trauma intensifies for each displaced person as they remember and grieve for the loss of their loved ones, their homes and homelands, without the benefits of compassionate therapeutic care.

Centred on interdisciplinary pathways towards creative spatial practices and spaces of recovery, the article traverses spatio-temporal memoryscapes of home (Butler, Citation2008). It seeks to contribute to emergent studies of creative agency in the aftermath of traumatic displacement and the way spatial, narrative, and material practices can help shift post-traumatic recovery towards a sense of self-realization and belonging (Boccagni, Citation2017; Lenette, Citation2019; Marshall, Citation2021). Grounded in the empirical findings of a multi-modal, participatory mapping project with refugees and asylum seekers in Southwest England, the article explores the transformative potential of slow, iterative, co-designed methodologies – in this case, deep-mapping. The memoryscapes of home reaffirm a person-centred approach to understanding the re-making of home and proactive integration in the context of displacement. From the standpoint of ethics, collaborative methodology and co-constructed knowledge production, the project and this article contribute to the current ‘messy and contested’ (Askins, Citation2018, p. 1283) landscape of research in participatory social and spatial justice in action.

The article follows a narrative, process-led structure, highlighting the participants’ insights and experiences, and aligning these through critical touchpoints to key areas of current debate in the fields of geography, displacement studies, psychology, and spatial practice. In this approach, concepts of home as it connects and disconnects from the rest of its immediate context (be it neighbourhood, street or city-scapes; Sheringham et al., Citation2021) are discussed through the spatial imaginary lens put forward by Alison Blunt and Dowling (Citation2006). This is expanded upon through an engagement with the material culture of home (and homeland) as a reciprocal approach to the production of a sense of agency and identity, seen as the retention of ‘a capacity for change’ (Miller, Citation2009, p. 99). At the intersection of asylum (approaching integration in urban life), displacement (loss of home and homeland) and making-home (the temporality of remaking of home in exile), the article pivots on Paolo Boccagni’s in-depth examination into the migration-home nexus focusing on space and time in relation to the concept of home from the margins Boccagni (Citation2017). We further consider the construct of memory, in particular memoryscape, to be a vital component in the remaking of home and the affirmation of identities. This responds to Owain Jones’s work on geography and memory (2012) as well as Toby Butler’s work on the mutability and affect of memory in informing an understanding of place – memoryscape (Butler, Citation2008) and aiding recovery (Lenette, Citation2019; Robinson, Citation2005). Critically, we argue that the construction of memory guides the process of re-making of home in displacement through the acts of deep-mapping and participation (Fleuret & Atkinson, Citation2007; Hernández, Citation2020; Lazarenko, Citation2020; Lenette, Citation2019).

Situated as a research-based spatial practice, this article moves the discussion of home from space fixity, as a container of things (at least in the domain of policy and housing provision) to spatial imaginaries of multiplicity and socially engaged action (in geographical terms) – a space of becoming that is open-ended, negotiated and reimagined – with methods for the design of space hinging on agency and grassroots activism (Dodd, Citation2020). Thus, home is approached through the performativity of practice, affect and memory as they are intrinsically linked to becoming, agency, creativity and imagination (Jones, Citation2011, p. 876).

The first section of the article details the project and its conceptual framework. The second introduces the participatory methodology and multi-modal methods, while the third highlights the gradual, participant-led development of memoryscapes of home, bridging between trauma and the construct of memory. The latter section pivots on participants’ memories of their homes and homelands recalled through interviews and workshops. The fourth section illustrates the space of recovery – the map and concomitant deep-mapping process – and affirms the vitality of ‘rupture’ (Murrani, Citation2020; Ratnam & Drozdzewski, Citation2020) in the relationship between the construct of memory and the concept of home processed and expressed tangibly in the space of the map. Findings within this section are supported by the feedback received from project participants at exit interviews and from exhibition participants, feeding into the larger tapestry of impact towards home negotiated, home imagined and home as a key to collective agency towards integration. The conclusion emphasizes spatial future imaginings of displacement that are constantly in the process of becoming – and overcoming rigid asylum and resettlement policies.

Creative Recovery through spatial practice

Funded by the European Cultural Foundation, Creative Recovery: Mapping Refugees’ Memories of Home as Heritage is a refugee and asylum seeker-focused pilot project launched at the initiative of the Displacement Studies Research Network at the University of Plymouth between September 2018 and October 2019. Through a creative participatory action research methodology (Kindon et al., Citation2007), the project shifts the focus onto displacees as creative agents in the process of recovery after the initial trauma of being dispersed across the UK. This enables them to become co-researchers and co-producers of vibrant and revelatory representations (Giritli-Nygren & Schmauch, Citation2012) of their original home environments, and to explore how valued aspects of this material, spatial and socio-cultural identity can be revitalized as they integrate within new communities. The conceptual framework for the project hinges on the contingency of the meaning of home and the material culture of belonging that are reconstituted as sites of memory in forcibly displaced contexts. It asks how a creative participatory method of mapping homescapes through memory reconsolidation can help ameliorate the trauma of displacement and aid the re-making of home.

Existing research with forced displacees in cities has been dominated by social service- and health-related projects, alongside robust investigations of the wider systemic frameworks within which the experience of refugeedom takes place (Darling, Citation2020). Research that brings together creativity in the fields of spatial practice, memory and migration has extensively covered the trauma of conflict (Halilovich, Citation2013), displacement in camps (Kiddey, Citation2020; Lacroix et al., Citation2013; Refugee Hosts, n.d.), and border crossings (Erens, Citation2000), but little research has focused on countering the trauma of integration in countries of arrival. Notably, there is a scarcity of research projects utilizing deep, slow and iterative participatory mapping processes (Lenette, Citation2019) that weave memory and history for making-home in exile (HomING., Citationn.d.).

Spearheaded by Boccagni (Citation2017), successful projects that examine the ‘migration-home nexus’ unpack how memory, experience, and relationships to material objects produce a collective sense of home. Home is thus demarcated as exceeding a spatial dimension, defined and considered from national, personal and collective perspectives (Boccagni, Citation2017, p. 136). Boccagni’s positioning of homemaking transcends the domestic; instead, it identifies the processes of belonging, settling, dwelling and asserting ownership over space, and their dependence on the economic opportunities and social structures made available to displaced communities. Homemaking looks at immigration on the local level and the dynamic and micro-relationships between host and guest. Boccagni and Hondagneu-Sotelo (Citation2021) argue that while homemaking can empower, it is not an egalitarian process – it is informed by gender, age, country of origin and other factors. These other factors and relations are framed as ‘more-than-human relations’ of imaginaries that blur, making displacees’ homes oscillate between the material relations of ‘nature and culture, private and public, domestic and non-domestic’ (Alam et al., Citation2020, p. 1125). Additionally, the gradual development of feelings of belonging in new host contexts has been shown to be positively supported through opportunities for ‘curated sociability’ (Rishbeth et al., Citation2019, p. 127), where the act of being together (Lobo, Citation2017) and engaging in activities within friendship or mentorship schemes has boosted engagement with the wider urban context and furthered connections with host communities. All of these were relations that our project grappled with and used as touchpoints to trigger discussions between participants at workshops.

The spatial turn has facilitated a deeper engagement with creative methods for social research on migration, acknowledging the power of visual participatory, creative, and co-produced research with migrants and refugees having transformative impact on migrants’ health and well-being, as well as contributing to their social integration (Jeffery et al., Citation2019). This further recommends the innovative and replicable approach developed and tested through the Creative Recovery project, providing that crucial link between the inward-looking work of recovery from trauma to outward-looking social connectivity and integration in the new context of making-home post-displacement. Lenette (Citation2019) makes a strong case for the capacity of creative and participatory research methods to create sanctuary. She identifies ‘Knowledge Holders’ as people with lived experience of forced migration as the central figures and leaders of research on refugeedom (Lenette, Citation2019, p. 240). Our project concurs with Lenette’s advocacy of creative participatory methods. Throughout our work, we remain wary of the possibility of slipping into a ‘fixed narrative’ of refugeedom and thus emphasize the importance of deconstructing and reconstructing the imagery, narratives and identities raised around this topic (Lenette, Citation2019, p. 240).

Experience-based co-design and creative deep mapping as a combined methodology of research

Aligned with the body of research linking creativity and healing (Stuckey & Nobel, Citation2010), Creative Recovery intentionally placed participants’ lived experiences in the spotlight. This process fostered agency and allowed space for self-representation by exploring markers of identity, guided by a participatory action approach known as Experience Based Co-Design (EBCD), an emerging method used successfully to develop and improve health services on the basis of patients’ narratives and lived experiences (Robert et al., Citation2015; Point of Care Foundation, Citation2020).

A slow, iterative, and cyclically-reflective process served as the backbone of the project. Over the course of nine months, the participants explored notions of self, home, identity, memory, displacement, and integration through initial interviews; a series of biweekly thematic mapping workshops; exit interviews; and self-representation through a collective exhibition of project outputs with open audience interaction and participation. The project’s methodology emphasized agency and self-representation through creative exploration rooted in the participants’ lived experience charted through self-identified emotional touchpoints – departing from, intersecting in, and gaining resolution from the concept of ‘home’.

These emotional touchpoints (critical topics from each participant’s perspective) loosely revolved, at least at initial prompt level, around the concept of home. Touchpoints evoked feelings of happiness or sadness in the teller, but also in others listening to or reading the narrative. Most importantly, however, they addressed issues around ‘testimonial injustice’ (Fricker, Citation2009) occurring when a speaker is denied a voice by being unheard or invalidated during interactions with others, commonly with those who hold more agency and social capital.

In line with a body of work highlighting the impact of narrative in medicine especially for establishing compassionate and transformative care, we used multimodal storytelling techniques to create powerful opportunities and routes to address testimonial injustice by utilising these testimonies as touchpoints: to feel heard is to feel validated. Within our workshops, such touchpoints formed the basis of discussions and created shared experiences, and also fostered empathy and bonding among the group, they later described this as meaningful and enriching. These touchpoints were also a core feature in the shaping of the narrative maps, with the participants becoming co-designers and co-producers of material that communicated and visualized their experiences and meanings. Our use of touchpoints extends the use of mapping ‘traumascapes’ in psychological research (Lazarenko, Citation2020) and psychogeography through the participant-led tracing of the indeterminacies of the refugee experience in a post-colonial landscape (Sidaway, Citation2021), utilizing the conceptualisation of home (homescapes) as sites of memory in response to displacement – in alignment with areas of focus within migration studies (Ehrkamp, Citation2017).

Participants took a leading role in constructing memories of their respective homescapes through maps, drawings, and personal photographs through a series of thematic workshops that fostered a multimodal, multi-skill approach, detailed in the project report (Murrani & Popovici, Citation2019). During the project’s nine workshops, the participants – a diverse group of refugees and asylum seekers from ten different countries – were introduced to experimental deep mapping (Roberts, Citation2016, p. 5) techniques (geographical, memory, narratives and stories, objects, photographs) to capture memories of everyday journeys charted at home. This method focused on eliciting prior and salient memories of home and the meanings enmeshed in these memories; some explicit, some yet to be discerned and consciously articulated. Subsequent questions explored how these memories could be enacted as experiences in the UK. This method deviates from directive questions that might ask how people felt about leaving their homes/homelands? Or, what have they left behind? Thus, the discussions and activities prompted the spontaneous co-construction of a narrative of personal value and agency, in which loss was just one strand of the tapestry of personal experience, rather than an all-defining and reductive label.

To this end, the project utilized mapping as an imagination-releasing process, combining narratives of objects and photographs of sentimental value with slow and iterative drawing and tracing of daily journeys taken by participants in their neighbourhoods (in their homelands), tracking back the locations of some of the photographs and sharing other memories of home-making. These cognitive maps, also known as ‘counter-maps’, are a set of embodied representations of temporality and states of precariousness charted cognitively through spaces of mobility by people fleeing home. Often, they stand in opposition to the ‘politics of bordering and ordering’ coordinated by a state (Campos-Delgado, Citation2018, p. 490). Mapping enabled the perfect set of tools to emerge, triggering new spatial practices of making-home as it oscillated between imagining, remembering, creating and transforming. Departing from Michel De Certeau’s (Citation1984, pp. 115–130) the maps traced and reframed the spatial stories of our participants’ spatial memories of home (homescapes), and reaffirmed making-home as an essential part of the spatial practices of the everyday as well as a powerful act of restitutive place-making in the world (Rose-Redwood et al., Citation2020). Thus, conceptualized and employed, maps are contingent, relational, and fleeting (Kitchin et al., Citation2013), produced while negotiating and re-territorialising space and time. This definition resonates with James Corner’s (Citation2002) description of the process of mapping as a ‘creative practice’ of ‘finding that is also a founding’. He assigns agency to the act of mapping which uncovers ‘realities previously unseen or unimagined, even across seemingly exhausted ground’ (Corner, Citation2002, p. 13).

We witnessed this process of ‘uncovering realities’ with several of our project participants, especially towards the end of the process, with the discovery that the slow and patient exploratory work of finding (again) and (re)founding the self in intersection with home became the space where participants recorded feelings of ownership, confidence, and self-worth.

In addition to maps, we utilized other visual methods in the form of photographs, films and storytelling to elicit narratives (lived and imagined), revealing the hidden complexity of meanings of home for each of our participants. In utilizing imagery methods for socially focused research (Banks, Citation2001) we understand the challenges that this approach brings with it, such as ‘the problem with images’ which creates ‘the problem with audiences’, yet we wish to emphasize that we follow MacDougall’s (Citation1978, p. 422). We remained mindful of the problematic visual representations of embodied experiences of refugees that reinforce othering and stereotyping even when they meant to evoke empathy (Lenette, Citation2016, p. 3). The focus is on the ‘meaning’ negotiated and constructed collectively and collaboratively by the researchers, the audience and the visual material produced, overlaying trauma, memory and meanings of home (connected together in the following section) into the space of a map.

Trauma, memory and home

People forced to flee their country of origin will have suffered a variety of terrible experiences prior to departure, and also in transit and on arrival to the country where they are seeking asylum. Understanding and supporting individuals in their responses to these experiences is not straightforward, due to significant variability in the individual expression of recognizable, established psychiatric labels such as PTSD. The use of these markers can be misleading in the assessment of responses to trauma and provision of care, unless viewed through the more nuanced lens of cultural norms and behaviour patterns.

The hippocampus is particularly sensitive to stress but also has the capacity for neuronal plasticity, producing the potential for the initiation and growth of self-led recovery through enriching, creative activities that use a combination of memory work and positive social interaction (Malabou, Citation2012). Jones (Citation2011) affirms this enrichment of memory in geographical studies by emphasising its complexity beyond the processual basics of encoding, storing, recording and retrieving of experiences that can occur sequentially or not, voluntarily and involuntarily (un/consciously), in the long or short term, as well as in a sensory manner. He situates the imaginative and creative aspect of memory in the performativity of practice embodied spatially through time, stating: ‘Memory is a key means by which the present is practiced’ (Jones, Citation2011, p. 879). This aspect of the performativity of memory is deeply connected to its fragility, especially in relation to vulnerable and traditionally excluded communities (Drozdzewski et al., Citation2016, p. 449). This idiosyncratic construct of memory certainly resonates with that of home, in particular displacees’ concept of homescape wrapped in traumascapes.

The narrative of the trauma of war and conflict, displacement, border crossing, detention, dispersal and integration, represented a common theme for Creative Recovery’s group of 12 participants. They originated from four continents, ten countries and spoke six languages but were united by emotional loss and longing for home. For ethical reasons, we deliberately did not speak of loss for the entire duration of the project; instead, our focus was on countering the trauma of loss through positive memories of home and homeland. To begin with, we felt the need to construct a shared meaning of home. Through memories, the participants reported different accounts of what home meant to them, unpacked below during interviews and workshops.

Memories of home

For Mohammed, a Palestinian from Gaza who recently graduated with a degree in management, home is a multiplicity and a totality situated between the individual and the collective agency of identity, belonging and nationhood. In addition to Mohammed’s photographs of childhood which were his way of explaining the meaning of home, he brought to the workshops his traditional scarf, the keffiyeh (كوفية – koofiyyeh) which represents his Palestinian nationality. The pattern of the keffiyeh is encoded with unity (black dots symbolizing the tight bonds between Palestinian people) but also separation (the border pattern represents the separation of Gaza from the rest of the world). This pattern carries deep personal meaning through its abstraction which can be interpreted by the wearer according to their individual life experiences and journey. From this perspective, Mohammed’s keffiyeh is an abstract map intersecting personhood and nationhood, and it quickly became the creative focus of his memoryscape map. Filtered through Mohammed’s own experience, the resulting piece also operates as a counter-map, reclaiming Gaza from the political and disciplinarian privilege and challenging their ‘authority to write the earth’ (Alderman et al., Citation2021, p. 67).

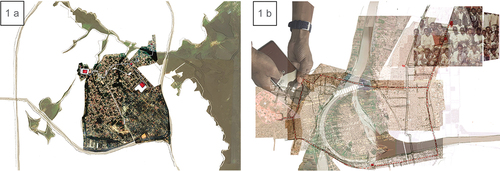

A single mother from Lagos (Nigeria), Deborah associates home with community traversed by socio-economic class, spirituality and resilience (). She describes the contrast between relatively affluent, poorer, and rough areas of the city, with the network of places of religious worship acting as a spiritual binding agent.

Figure 1. a. Deborah’s map representing her daily journey in Lagos between her and her best friend’s houses and the church. b. Waleed’s map of memory and home layering photos from his childhood onto daily journeys across the Nile which he continued to do throughout his adult life in Sudan.

Land and home ownership in Nigeria are difficult to attain, resulting in large segments of the population living in collective compounds where housing units are rented at extortionate prices. Although houses in the compound are shared between 15 and 40 people, with different tribes coming together to socialize, Deborah’s account also suggested a constant state of vigilance required for cohabitation – there were fights, violence targeted towards children, and accidents: ‘If everyone could build, nobody would live in shared houses.’ Deborah’s best memories of home revolve around coming together with others at her local church to observe a shared spirituality. Although not articulated, perhaps the equalizing effect of the spatial dialogue between divinity and congregation subconsciously enhanced her experience and memory of these events.

Waleed is a human rights activist from Khartoum, Sudan who has been away from his homeland for 20 years yet still does not feel at home in exile. He expresses that his concept of home remained rooted in the time of childhood and the place where his family still resides. Waleed emphasizes his strong connection to the Nile and memories of swimming across to fruit farms on the other side of the river (). For Waleed, his memory of home is a transgressive and performative concept, echoing Jones’s assertion of the connectivity between memory and geography (Jones, Citation2011). Waleed forged the freedom to drift across boundaries between the spatial sensibility of the place where he grew up and the imaginative alternative life he constructed through books, novels and poems.

Waleed explained that his inability to put down roots is represented in his resistance to put framed pictures of his family on any walls in a place that could never be home, including the flat where he currently lives. With a spatial sensibility of a flâneur, Waleed uses photos he stores online of home and all the places he has visited as memoryscapes that define him beyond the geographical boundaries of his current, past or future location.

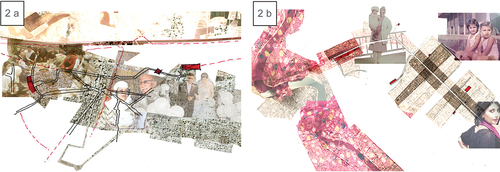

For Mahmoud, a trainee doctor from Kobanî, Syria, currently working as a delivery driver in the UK, home is the smell of his mother’s freshly baked flat bread in a clay oven; the mountains and the freedom of animals roaming around; his evening gatherings with his friends drinking tea in winter and a cold yogurt drink (Ayran) in summer; smoking shisha; playing cards; and sleeping outside in the garden counting the stars at night. He noted the feeling he had when he first visited Dartmoor, finding it the closest place in the UK to his home in Syria. Mahmoud stated that these feelings and connotations of home are shared between all his village community who are predominantly farmers. By disassociating home from just the bricks (or in his village’s case, stone) and mortar of the house, almost all villagers were able to return to rebuild homes in exactly the same geographical location as their previous dwellings after their complete wipe-out of during the constant shelling and bombing between 2011 and 2016. He further recalls: ‘We had the mental capacity to make them even bigger and better than before.’ The villagers’ attachment to home was geographical, communal and experiential, yet never to a building per se ().

Figure 2. a. Mahmoud’s map included the boundaries of the village and showed the main routes to Aleppo (the closest city). It also included a photograph of his wedding focusing on the community relevance of that event in his village. b. Basma’s map reflected the dichotomy of freedom and oppression of women through her choice of photos showing her as a liberal Iraqi while reflecting on the close-knit spatial context of her dense urban environment.

Holder of a Fine Arts degree and single mother from Baghdad, Iraq, Basma finds home in her connections with her family and the community around them. She spoke predominantly about that network expanding and shrinking depending on major life events. During her last few years in Iraq, as a divorcee, she lived in a block of flats close to her parents’ house and her daughter’s school. She recalled being able to see and hear the children playing in the playground at break time but also being watched from other balconies by the distant neighbours, alluding to the fact that in a conservative society (that had become more extreme after years of war, sanctions and sectarian violence), a single mother in a flat is judged for her past as well as protected by the neighbours. This dichotomy of protection and surveillance, among others such as freedom and oppression of women in general, are common in a conservative society ().

This sample of definitions and rich juxtapositions of meaning around the construct of home through memory reveals the universal, human relatability of home as a fundamental prerequisite of wellbeing and personhood (having or having known one; making or longing for one; refusing to be beholden to one), but also its challenging fluidity. Home becomes an edgeless notion rooted in experience instead of place (Murrani & Popovici, Citation2019). It becomes spatial and temporal, or purely emotive and relational. It can be grasped, achieved, lived in, and constructed, or longed-after in the ineffable terrain of the mind and imagination. Home is to have a place, to know one’s place, to critique one’s place within society. This malleable meaning of the concept of home is manifest through lived and imagined experiences. Blunt and Dowling tie this contingent nature of home to everyday home-making practices which they describe as spatial imaginaries (Blunt & Dowling, Citation2006, p. 254).

Home, revisited through the imprecise art of memory, is both less and more: less, as the enforcement of societal restriction fades; and more, as the endless possibilities of a tranquil, hopeful childhood solidify. Catherine Loveday postulates and then further adds:

Each time we remember a moment from our life we construct it anew. We do this by using the building blocks of episodic memory – recollective feelings of being somewhere; and semantic memory – concrete knowledge about our world […] and about our personal history […]. Memories are almost never 100 percent accurate, and all memories are malleable and changeable. (Loveday, Citation2018, p. 64)

Paula Reavey (Citation2017) explains that memories are interwoven from multiple narratives of the past and material objects which occupy a space in time. These are therefore also known as ‘memoryscapes’ or ‘geographies of memories’ (Reavey, Citation2017, p. 107). Similar to Butler’s (Citation2008) geographies of memory and nostalgia, our participants’ stories chart all (and more) of these intricacies of memoryscapes through space and time, often choosing to describe home through the activities taking place therein, through the people filling it with the joys and sorrows of the everyday, and through the journeys on which it is a starting, middle, and endpoint. The material objects brought in to support these kaleidoscopic imaginings of homescapes are likewise complex: traditional wedding attire is not only representative of a milestone in a woman’s life, starting from the home, but also of her place in and treatment by society. Like home, the inclusion of material culture plays a vital part in the production and re-affirmation of identity. According to Miller, not only homes, clothes and belongings can be prohibitive and instrumental to developing a sense of agency and identity (Miller, Citation2009, p. 220).

A simultaneity of scales – from the personally minute to the broadly national – permeates these understandings and mappings of home, and, with each retelling and remembering, the ground shifts to allow new meanings of associations – past, present, and future. These scales are influenced by the degree of ‘rupture’ in displacees’ daily lives and the space needed for recovery. Ratnam and Drozdzewski (Citation2020) engage with the meaning of detours as ruptures in the mobility of a group of forcibly displaced Sri Lankan refugees attempting to resettle in Sydney, Australia:

In the new mobilities paradigm, places are intertwined processes, experiences, and networks constructed over the lifecourse, and carried to new homes and places of resettlement. Different memories, experiences, and identities amass and are carried too; rupture points become parts of the lifecourse. (Ratnam & Drozdzewski, Citation2020, p. 760)

Creative Recovery engaged with this syncretic synergy between the contingent concept of home and the plasticity of the construct of memory through map-making, where maps became spaces of recovery from trauma, explored in context in the following section.

Spatial recovery: impact of common threads in a larger tapestry

The act of deep mapping facilitated the creation of alternative spaces of imagination, visualized ruptures in the course of participants’ journeys, and provided a valuable sense of recovery and reclamation of making-home in exile. We call attention to the notion of ‘rupture’ (Murrani, Citation2020) as causing both migratory displacement and detour in movement and obstructed mobilities in participants’ journeys into safety. Identifying ‘rupture’ emphasizes the multiple stopping points and homes in the migratory journey that resist and move beyond a singular narrative of what settling and making-home means in exile. Through the work of one of our participants, we illustrate the notion of ‘rupture’ found in the intricacies and fragility of mapping a space of recovery during mapping home from memory.

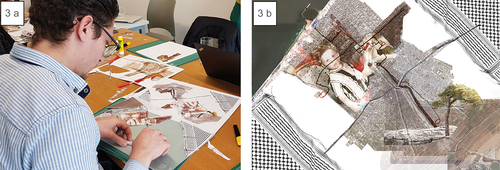

Mohammed’s approach to the idea of home was grounded in building and growing community relationships: his experiences volunteering and event organising during university had moulded his spatial practices of home with transfigurative power aimed towards collective agency. A favourite seaside promenade was a spatially fluid arena for shared dreams and social projects, masterminded whilst walking side by side with friends. This fluid sensibility of space enabling and hosting social agency in service of both the city and the self was also filtered through Mohammed’s creative homescape collage, built around his traditional Palestinian scarf ().

Figure 3. a. Mohammed assembling the intricate components of his memoryscape charted through his childhood and through the streets of Gaza from the mountains to the sea. b. Mohammed’s final map showing at its heart a photo of his childhood placed between the mountains and the sea and shrouded by his Gazan keffiyeh.

The geometrically abstract pattern encodes a wealth of meanings on a range of scales – from one’s own room to the entire Gaza Strip, and from the deeply personal to the political. As part of his mapping process, he discovered that the three opensource maps that we provided of Gaza did not match one another when overlaid and – more importantly to him – did not reflect his vivid memories of the streets of Gaza (from as recently as 2017). Further research revealed that for political and security reasons no one map of Gaza is identical to another – a finding that encouraged Mohammed to map Gaza the way he remembered it cognitively (). This directly impacted his growth through the project by reaffirming his passion for advocacy, particularly in addressing the inaccurate and negative portrayal of Gaza and refugees in the UK. Soon after the project finished, Mohammed was granted refugee status. He moved to Scotland to start an MA in International Relations and Politics at the University of Edinburgh and shortly after was offered a job at the Scottish Refugee Council.

This transformative and informal process of slow, iterative and cognitive deep mapping charted through ‘rupture’ had a demonstrably beneficial effect on all of the participants, reflected in the quotations below. The open-ended, co-created maps of the coordinates of diverse memoryscapes of journeys taken at home (and homelands) have encouraged not only the re-affirmation of a sense of personal and cultural self but also their adaptation and re-rooting in a displaced context. Participants recall:

It just made me realize more about myself, and my journey, and my childhood, and all this kind of memories. Being involved in the project, listening to my other colleagues, what they are saying and just starting to realize like there are too many things I didn’t know that they mean anything to me until the project came. It’s really good, like, even emotionally and psychological like, it definitely helped me a lot. (Tarig from Sudan, from an interview at the opening night of the exhibition, June 2019)

In the past we have spoken many times about our memories, but this time it is different, it’s something unique, we portray our memories by mapping. Some part we feel nostalgic to the past, and the faces, and to the routes we used to take back home, but another part we are proud of what we have achieved.

I have three homes actually, one of them is Palestine, Gaza with my family and friends, and one is here with my new friends, and one is the world itself.

I map, therefore, I am. (Mohammed from Gaza, from an interview with BBC Spotlight Southwest, June 2029)

Alongside the self-perceived sense of recovery from loss and the trauma of displacement reported by participants during interviews, three additional findings were revealed through the qualitative analysis of their responses. First, we detected a sense of optimistic self-projection into the future as creative agents. The memoryscape of home, once (re)constructed, becomes a fluid mental place of catharsis – and, beyond the cusp of recovery, a source of psychological resilience, supporting the shift towards thriving. Second, conceptualising and physically producing the maps enabled participants to ‘make real what was in our head’ (one participant remarks during a workshop); to articulate and externalize feelings, meanings, and ideas of home that support criticality and self-assertion in the pursuit of making-home in exile. Third, the participants’ emergent awareness of social, cultural, and political issues affecting their countries of origin, the UK, and EU has evolved into a keen interest in advocacy for social integration, as well as community and social work focused on nurturing multicultural relationships.

The above findings may also inform policy-making at local and central government levels in the provision of housing alongside educational and professional opportunities. The first level of this ripple effect has already been tested through an exhibition featuring the participants’ creative maps and personal narratives, alongside interactive opportunities for the audience to reflect on the patterns, joys, and challenges of making-home in an era of increasingly normalized transnational mobility. Below, are the common threads emerging from the impact study of the Mapping Creative Recovery exhibition.

1. Home negotiated

Home as a plural, edgeless, re-negotiable realm blending imagination, daily spatial practices (Murrani & Popovici, Citation2019), and a web of associated social relationships, is the unifying thread running through the exhibition survey answers. The exact blend of the material and immaterial elements that coalesce into home varies substantially, although all share to a significant extent a range of experiential markers of identity that are constantly negotiated. This negotiation results from the spatial practice that is imagined, lived, and experienced in relation to mobility, material culture, temporality and precarity of making-home on the move (Murrani, Citation2019). It further allows different considerations of scales of negotiation at the subjective level constructed by the act of making-home in exile, as well as the cultures and dynamics this produces exterior to the individual (Miranda Nieto et al., Citation2020, p. 196) all wrapped into notions of constant ‘rupture’ to daily lives.

2. Home transformed from space to imagination: the self as a nexus for home

Most exhibition visitor responses to the question ‘What does home mean to you?’ firmly placed home as memory; this open-ended answer outstripped three multiple-choice options, demonstrating the importance of memory in providing a space for self-definition. Although the visitors’ answers touched on a few common themes (safety and belonging, love and acceptance, calmness and contentment, the familiarity of the everyday), they also indicated that home is a space-in-flux for growing, becoming and imagining, a non-defined entity constantly re-worked through the practices of the everyday.

A final point of impact between the project and its public reception hinges on the individual, deeply personal narratives of self-representation co-produced by the project participants. The combination of storytelling and shared memories, photographs/portraits capturing the essence of each participant beyond their refugee status, and the maps exploring their imaginative journeys of recovery, supports Lenette’s art-based participatory action research methods towards sanctuary (Lenette, Citation2019), a dimension often absent in the discourse around cities of sanctuary in the UK, where aspects of territoriality and policy-making often overshadow relational place-making (Darling, Citation2010). The commonalities of human experience regardless of cultural background and the fundamental need to be seen and heard across the eroding noise of ignorance and misrepresentation (Fricker, Citation2009) further reverberated through the exhibition’s open feedback.

3. Home: a key to collective agency and integration

Home belongs to a community of shared, yet negotiable values, with the capacity to enact positive social change outside its immediate sphere of influence. Through an open-ended brainstorm for follow-on research that would enhance and expand on the current project, exhibition visitors indicated the importance of sustained community outreach and involvement for robust social integration, which was not to be confused with assimilation (Boccagni & Hondagneu-Sotelo, Citation2021). Our participants suggested that this could be achieved by pursuing a shift in public opinion through educational initiatives, particularly within local school communities, with the broader goal of influencing the formulation of social policies. Furthermore, the respondents remarked on the crucial role of the creative engagement of refugees in development projects, particularly housing but more generally with more-than-human imaginaries, for example, economic, spiritual, and aesthetic imaginaries of home (Alam et al., Citation2020) as being key to integration.

Conclusion: future imaginings

The project took the participants on a journey of recovery through the map, engaging an expanded model of memory in space and time where the construct of memory and the concept of home overlapped into memoryscapes of creative recovery in displacement. Yet these journeys have not stopped at the making of maps. Some of our project participants have since been granted refugee status and continue to negotiate new life challenges, migration-based systems of control and assistance (e.g., social services; Brun & Fábos, Citation2015, p. 14), affirming that making home is a process of negotiation rather than a fixed destination.

Developed through our EBCD approach to mapping refugees’ memories of making-home, our project brought to light participants’ exceptional awareness of transnational connections; their related skills in digital social media; and a complex ruptured (responding to continuous disruption) understanding of what it would take to make themselves truly at home again (Murrani, Citation2020). Our deep mapping process was enriched through multi-modal, diverse testimonies, challenging the reductive labels placed on displacees by foregrounding the plurality of their journeys through traumascapes projected onto the maps.

Isobel Blomfield and Lenette (Citation2018) speak of the risks of arts-based projects with refugees and asylum seekers. Even the production of counter-narratives to damaging discourses can reinforce existing tropes and stereotypes through the artist’s lack of lived experience and reflexivity, and through the assumption of a ‘de facto’ incapability of ‘misrepresentation in their collaborations’, thus perpetuating voicelessness, othering, and disempowerment (pp. 322–323). We remain mindful of such pitfalls by focusing on the process of mapping and its meaning with regards to participants’ memoryscapes of home and its future imagining. Alongside Kesby (Citation2007) we remain attentive to the crucial step of identifying the resources and processes with applicability outside the immediacy of the project and PAR research, ‘enabling agents to repeatedly mobilize them to enact empowerment elsewhere’ towards ‘stable reperformance of empowered forms of agency’ (p. 2852).

With its focus on the diverse notion of home, the project enabled our co-researchers to operate on a range of scales, from the immediately personal to the urban and the national, and to actively seek methods – like deep-mapping – whereby the tension-fraught but fruitful confrontation of these levels could be explored. Cartography’s epistemological turn towards the processual, contingent, and unfolding acknowledges the co-constitutive link between map-space and world-place which is both ideological and pragmatic (Kitchin et al., Citation2013). This shift has opened the act and the space of mapping to situated knowledges and modes of spatial practice previously made liminal by the orthodoxy of (colonial) cartography, foregrounding a plurality of Indigenous (Rose-Redwood et al., Citation2020), Black (Alderman et al., Citation2021), and now, refugee counter-mappings. Our participants creatively revisited, contested, and qualitatively enhanced digital cartographic representations of their homes through the messy materiality of making, forging a social space of meaningful encounters and renegotiation of the situated self and social relationships in both discursive and embodied ways.

The article situates the role of memory work at the heart of making-home practices, linking the two constructs of memory and home at different scales of rupture (Ratnam & Drozdzewski, Citation2020), through performativity and imagination (Jones, Citation2011). This expanded model of memoryscape afforded a sense of personhood, self-efficacy and a safe place to express emotions and feelings about home and self (Boccagni, Citation2017; Miller, Citation2009). The nexus of home and self is crucial to the establishment of new social negotiations of difference and similarity, traversed by aspects such as race, gender, and ethnic background. Such spatially imagined and recovered negotiations, percolate in the exercise of making, anchored in significant urban and domestic spaces.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the European Cultural Foundation through their Courageous Citizens 2018 grant funding (Grant reference: RD201809) as well as the Sustainable Earth Institute’s Creative Associate 2019 Scheme at the University of Plymouth. The authors further extend their gratitude to the Plymouth Branch of the British Red Cross who acted as our project partner and gatekeeper organisation. Most importantly, the authors would like to thank all twelve participants who gave generously time and energy and had unparalleled faith in this project and its team. The authors confirm that all ethical protocols and approvals including consents have been obtained from the University of Plymouth and the participants before the start of the research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alam, A., McGregor, A. & Houston, D. (2020). Neither sensibly homed nor homeless: re-imagining migrant homes through more-than-human relations. Social & Cultural Geography, 21(8), pp. 1122–1145. DOI: 10.1080/14649365.2018.1541245

- Alderman, D. H., Inwood, J., & Bottone, E. (2021). The mapping behind the movement: On recovering the critical cartographies of the African American Freedom Struggle. Geoforum, 120(6) , 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.01.022

- Askins, K. (2018). Feminist geographies and participatory action research: Co-producing narratives with people and place. Gender, Place & Culture, 25(9), 1277–1294. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1503159

- Banks, M. (2001). Visual methods in social research. SAGE Publication.

- Blomfield, I., & Lenette, C. (2018). Artistic representations of refugees: What is the role of the artist? Journal of Intercultural Studies, 39(3), 322–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2018.1459517

- Blunt, A., & Dowling, R. (2006). Home. Abingdon. Routledge.

- Boccagni, P. (2017). Migration and the search for home: Mapping domestic space in migrant’s everyday lives. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Boccagni, P., & Hondagneu-Sotelo, P. (2021). Integration and the struggle to turn space into “our” place: Homemaking as a way beyond the stalemate of assimilation vs transnationalism. International Migration. March 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12846

- Bremner, J. D. (2006). Traumatic stress: Effects on the brain. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 8(4), 445–461. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.4/jbremner.

- Brun, C., & Fábos, A. (2015). Making homes in Limbo? A conceptual framework. Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees, 31(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.25071/1920-7336.40138

- Butler, T. (2008). Memoryscape’: Integrating oral history, memory and landscape on the river Thames. In P. Ashton & H. Kean (Eds.), People and their pasts: Public history today. Basingstoke. Palgrave Macmillan. 223–239 .

- Campos-Delgado, A. (2018). Counter-mapping migration: Irregular migrants’ stories through cognitive mapping. Mobilities, 13(4), 488–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2017.1421022

- Corner, J. (2002). The agency of mapping: Speculation, critique and invention. In D. Cosgrove (Ed.), Mappings (pp. 213–252). Reaktion Books Ltd.

- Darling, J. (2010). A city of sanctuary: The relational re-imagining of Sheffield’s asylum politics. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 35(1), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2009.00371.x

- Darling, J. (2016). Asylum in austere times: Instability, privatization and experimentation within the UK asylum dispersal system. Journal of Refugee Studies, 29(4), 483–505. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/few038

- Darling, J. (2020). Refugee urbanism: Seeing asylum ‘like a city. Urban Geography. 42(7), 894–914 . https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1763611

- de Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life (S. Rendall, Trans.). Berkeley. University of California Press.

- Dodd, M. (2020). Spatial practices: Modes of action and engagement with the city. Abingdon. Routledge.

- Drozdzewski, D., De Nardi, S., & Waterton, E. (2016). Geographies of memory, place and identity: Intersections in remembering war and conflict. Geography Compass, 10(11), 447–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12296

- Ehrkamp, P. (2017). Geographies of migration I: Refugees. Progress in Human Geography, 41(6), 813–822. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516663061

- Erens, P. (2000). Crossing borders: Time, memory, and the construction of identity in ‘Song of the Exile’. Cinema Journal, 39(4), 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2000.0015

- Fleuret, S., & Atkinson, S. (2007). Wellbeing, health and geography: A critical review and research agenda. New Zealand Geographer, 63(2), 106–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7939.2007.00093.x

- Fricker, M. (2009). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

- Giritli-Nygren, K., & Schmauch, U. (2012). Picturing inclusive places in segregated spaces: A participatory photo project conducted by migrant women in Sweden. Gender, Place and Culture, 19(5), 600–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2011.625082

- Halilovich, H. (2013). Places of pain: Forced displacement, popular memory and trans-local identities in Bosnian war-torn communities. Berghahn Books.

- Hernández, K. (2020). Land and ethnographic practices—(re)making toward healing. Social & Cultural Geography, 21(7), 1002–1020. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2020.1744703

- Home Affairs Committee. (2017). Asylum accommodation. Twelfth report of session 2016–17. (House of Commons, HC 637). https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmhaff/637/637.pdf

- HomING. (n.d.). The Home-Migration Nexus. n. d. Home as a window on migrant belonging, integration and circulation. https://homing.soc.unitn.it/

- Jeffery, L., Palladino, M., Rotter, R., & Woolley, A. (2019). Creative engagement with migration. Crossings: Journal of Migration & Culture, 10(1), 3–17. doi:10.1386/cjmc.10.1.3_1.

- Jones, O. (2011). Geography, memory and non-representational geographies. Geography Compass, 5(12), 875–885. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2011.00459.x

- Kesby, M. (2007). Spatialising participatory approaches: Geography’s contribution to a mature debate’. Environment and Planning A, 39(12), 2813–2831. https://doi.org/10.1068/a38326

- Kiddey, R. (2020). Reluctant refuge: An activist archaeological approach to alternative refugee shelter in Athens (Greece). Journal of Refugee Studies. 33(3) , 599–621. doi:10.1093/jrs/fey061.

- Kindon, S., Pain, R., & Kesby, M. (Eds.). (2007). Participatory action research approaches and methods: Connecting people, participation, and place. Abingdon. Routledge.

- Kitchin, R., Gleeson, J., & Dodge, M. (2013). Unfolding mapping practices: A new epistemology for cartography. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 38(3), 480–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00540.x

- Lacroix, T., Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E., Lacroix, T., & Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E. Refugee and diaspora memories: The politics of remembering and forgetting. (2013). Journal of Intercultural Studies, 34(6), 684–696. Eds. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2013.846893

- Lazarenko, V. (2020). Mapping identities: Narratives of displacement in Ukraine. Emotion, Space and Society. 41(2) , 293–315. doi:10.1080/00905992.2012.747498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2020.100674

- Lenette, C. (2016). Writing with light: An iconographic-iconologic approach to refugee photography. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 17(2). Art. 8 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs160287

- Lenette, C. (2019). Arts-based methods in refugee research: Creating sanctuary. Springer.

- Lobo, M. (2017). Re-framing the creative city: Fragile friendships and affective art spaces in Darwin, Australia. Urban Studies, 55(3), 623–638. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016686510

- Loveday, C. (2018). The brain: What it does, how it works, and how it affects behaviour. André Deutsch, Carlton Publishing Group.

- MacDougall, D. (1978). Ethnographic film: Failure and promise. Annual Review of Anthropology, 7(1), 405–425. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.07.100178.002201

- Malabou, C. (2012). The new wounded: From neurosis to brain damage. (S. Miller, Trans.). Fordham University Press.

- Marshall, D. (2021). Being/longing: Visualizing belonging with Palestinian refugee children. Social & Cultural Geography, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2021.1972136

- Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford. (2020). Immigration detention in the UK. https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/immigration-detention-in-the-uk/

- Miller, D. (2009). Stuff. Cambridge. Polity.

- Miranda Nieto, A., Massa, A., & Bonfanti, S. (2020). Ethnographies of home and mobility: Shifting roofs. Abingdon. Routledge.

- Murrani, S. (2019). Urban creativity through displacement and spatial disruption. In M. E. Leary-Owhin & J. P. McCarthy (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Henri Lefebvre: The city and urban society (pp. 402–410). Abingdon. Routledge.

- Murrani, S. (2020). Contingency and plasticity: The dialectical re-construction of the concept of home in forced displacement. The Journal of Culture and Psychology, 26(2), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X19871203

- Murrani, S., & Popovici, I. (2019). Mapping Creative Recovery. (Project Report). European Cultural Foundation. https://creativerecovery1819.files.wordpress.com/2020/03/creative-recovery-report.pdf

- Point of Care Foundation. (2020). EBCD: Experience-based co-design toolkit. https://www.pointofcarefoundation.org.uk/resource/experience-based-co-design-ebcd-toolkit/

- Ratnam, C., & Drozdzewski, D. (2020). Detour: Bodies, memories, and mobilities in and around the home. Mobilities, 15(6), 757–775. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2020.1780071

- Reavey, P. (2017). Scenic memory: Experience through time–space. The Journal of Memory Studies, 10(2), 107–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698016683844

- Refugee Hosts. (2020). Local community experiences of displacement from Syria: Views from Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey. https://refugeehosts.org/

- Rishbeth, C., Blachnicka-Ciacek, D., & Darling, J. (2019). Participation and wellbeing in urban greenspace: ‘Curating sociability’ for refugees and asylum seekers. Geoforum, 106, 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.07.014

- Robert, G., Cornell, J., Locock, L., Purushotham, A., Sturmey, G., & Gager, M. (2015). Patients and staff as codesigners of healthcare services. BMJ, 350, g7714. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7714

- Roberts, L. (2016). Deep Mapping and Spatial Anthropology. Humanities, 5(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/h5010005

- Robila, M. (2018). Refugees and Social Integration in Europe. Expert group report to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs – UNDESA.

- Robinson, C. (2005). Grieving home. Social & Cultural Geography, 6(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464936052000335964

- Rose-Redwood, R., Barnd, N. B., Lucchesi, A. H., Dias, S., & Patrick, W. (2020). Decolonizing the map: Recentering indigenous mappings. Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization, 55(3), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.3138/cart.53.3.intro

- Sheringham, O., Ebbensgaard, C., & Blunt, A. (2021). ‘Tales from other people’s houses’: Home and dis/connection in an East London neighbourhood. Social & Cultural Geography, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2021.1965197

- Sidaway, J. D. (2021). Psychogeography: Walking through strategy, nature and narrative. Progress in Human Geography, 030913252110172. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325211017212

- Stuckey, H. L., & Nobel, J. (2010). The connection between art, healing, and public health: A review of current literature. American Journal of Public Health, 100(2), 254–263. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.156497