ABSTRACT

Although the intensification of direct and indirect gendered violence against women during the COVID-19 pandemic has been extensively reported globally, there is limited research on women’s responses to it. Addressing calls to explore the relationships between emotional-affective atmospheres and politics during the pandemic as well as to centre analyses of gendered violence within geography, this paper explores how women in the favelas of Maré, in Rio de Janeiro have developed mutual support, (self)-care and activism in the face of the crisis. Engaging with nascent debates on responses to COVID-19, together with feminist geographical work on resistance to gendered violence, the article adapts the notion of ‘emotional communities’ developed by Colombian anthropologist, Myriam Jimeno, to examine how emotional bonds created among survivors of violence are reconfigured into political action. Drawing on qualitative research with 32 women residents and 9 community actors involved in two core community initiatives in Maré, the paper develops the idea of building reactive and transformative ‘emotional-political communities’ at individual and collective levels to mitigate gendered violence and wider intersectional structural violence. Emotional-political community building is premised on grassroots activism among women and organisations that develops as part of compassionate (self)-care and the quiet rather than spectacular politics of change.

Introduction

The intensification of gendered violence against women and girls, and especially domestic violence, during the COVID-19 crisis has been one of the most widely reported phenomena globally (Agüero, Citation2021). This needs to be situated within pre-existing gender inequalities that have also deepened during the pandemic (Azcona et al., Citation2020; Smith et al., Citation2021) alongside recognition of the exacerbation of multiple types of violence against women beyond intimate partner and interpersonal to encompass indirect forms of structural, symbolic and systemic violence. Furthermore, there is a growing recognition that these gendered effects need to be viewed through an intersectional lens, creating ‘intolerable intersectional burdens’ (Ho & Maddrell, Citation2021), especially for poor racialised women experiencing gendered violence in the world’s urban peripheries (Chen, Citation2020; UN Women, Citation2020).

While the harmful intersectional ramifications of the pandemic must not be under-estimated as people struggle with illness, grief and economic devastation (Kabeer et al., Citation2021), there is some evidence of the emergence of mutual support, solidarity and activism (Ho & Maddrell, Citation2021). However, less attention has been paid to how women have dealt with the disproportionate effects beyond feminist calls to arms around rethinking social reproduction and systemic intersectional inequalities (Morrow & Parker, Citation2020). There remains an urgent need to explore how women respond to the effects of COVID-19 in relation to gendered violence. Addressing calls by feminist geographers to hasten analyses of gendered violence as situated within socio-spatial, cultural, economic and political systems (Brickell, Citation2015; Brickell & Maddrell, Citation2016; Pain, Citation2015), the focus here is on direct and indirect forms within and beyond the private sphere among those living in situations of endemic urban conflict dealing with the slow violence of state neglect and marginalisation (Brickell, Citation2020; Datta, Citation2016).

While women’s multiple forms of resistance to gendered violence in the absence of or active alienation by the state has also received considerable attention among feminist geographers and others alike (Boesten, Citation2012; Faria, Citation2017; P. Pain, Citation2014; Piedalue, Citation2022; Rajah & Osborn, Citation2020), there is scope to explore these in the context of the pandemic. Beyond spectacular and criminal justice interventions, it is long acknowledged that women and feminist organisations have constructed ‘emotional communities’ as part of processing, dealing with and resisting violence (Jimeno, Citation2008; Macleod & De Marinis, Citation2018). During the COVID-19 crisis when emotional-affective intensities and mutual solidarities emerge, there are potentialities for capturing these for transformative purposes (Maddrell, Citation2020).

This paper engages with these issues through an exploration of the lived experiences of dealing with gendered violence in the favelas of Maré in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Empirically, it draws primarily from qualitative research conducted since the onset of the crisis with 32 women residing in the territory (based on interviews and five focus groups), and with a range of community actors who have mobilised around two initiatives to deal with pandemic-related issues. The first has been a campaign to address urgent basic needs and sustenance by distributing food and hygiene goods, and the second, a collaborative support network for women created to deal with the rise in incidence of gender-based violence.

Conceptually, the discussion engages with Maddrell’s (Citation2020, p. 108) call to consider how an ‘emotional-affective geographies lens’ can assist in understanding the effects of COVID-19 focusing especially on ‘the relation between emotional-affective atmospheres and politics’. It draws from feminist debates on how women develop a range of agentic tactics to gendered violence that may be small-scale and individual or more collective and formalised (also Brickell, Citation2020; Pain, Citation2014; Piedalue, Citation2017, Citation2022), and with the potential to bring about ‘gender transformation’ (Moser, Citation2021). The specific conceptual framing lies in Latin American thinking drawing on Myriam Jimeno’s elaborations of ‘political-affective’ and ‘emotional communities’ (Jimeno, Citation2008; Jimeno et al., Citation2018). In adapting the original conceptualisations according to which affective regimes are forged among victims/survivors of community violence through sharing and reconfiguring emotional testimonies into political struggles, we develop the idea of building ‘emotional-political communities’ in order to understand the processes of recognising and addressing gendered violence against women during crisis. This is articulated by differentiating the notions of ‘reactive’ and ‘transformative’ emotional-political communities at individual and collective levels, which reflect a non-linear move from responding to immediate needs in a crisis towards promoting more longer-term and structural changes.

The first section situates the discussion within our core conceptual framing around ‘emotional-political communities’ through engagement with geographical and feminist theorising around gender transformation, situated agency, and various forms of resistance to gender-based violence. The second outlines the contexts of gendered poverty and urban armed violence in Maré, Rio de Janeiro, together with the methodological framework. The third section explores the ways in which emotional-political communities have been built on pre-existing everyday tactics through interrelated reactive and transformative processes. The conclusion retraces the core components of the notion of building reactive and transformative ‘emotional-political communities’ and reflects on its broader contributions to feminist geographical work on gendered violence, coping and resistance, especially in the context of COVID-19.

Articulating emotional-political communities to address gendered urban violence

As noted above, this section outlines the conceptual framing for the article around re-thinking the notion of ‘emotional communities’ developed by Colombian anthropologist Myriam Jimeno (Citation1998, Citation2008). This also builds on geographical and feminist research on practices and tactics of resistance and agency to confront gendered violence against women (Brickell, Citation2020; Pain, Citation2014; Piedalue, Citation2017, Citation2022), especially in high conflict urban areas (Hume & Wilding, Citation2020; Zulver, Citation2016) to engender ‘gender transformation’ (Moser, Citation2021). It develops the idea of ‘emotional-political communities’ as part of an exploration of the ‘emotional-affective geographies’ of the pandemic focusing on how loss and desperation can engender political action (Maddrell, Citation2020). We argue that the pandemic has led to gendered emergency responses to provide basic needs as well as assistance for those facing increases in gendered violence. This has led to the emergence of ‘reactive emotional-political communities’ primarily at collective levels, but also individually. More strategic ‘transformative emotional-political communities’ have also emerged over time involving the provision of income-generating opportunities and organising around reproductive and other rights in the context of wider urban and structural violence.

The concept of ‘emotional communities’ Jimeno (Citation1998, Citation2008) evokes the role of emotions in social and political struggles around everyday experiences of violence. Forged through anthropological research with displaced Nasa indigenous survivors of a paramilitary massacre in Colombia, Jimeno (Citation1998) originally used the term ‘political-affective’ communities which has since been taken-up by others in relation to armed conflicts, organised crime, dictatorial repression and everyday urban violence (Macleod & De Marinis, Citation2018). Jimeno (Citation1998) used this to refer to processes in which political narratives engage wider audiences, fostering systems of emotional-political bonds, as well as belonging and identity that further engender collective action towards justice and reparation. She then developed this further to refer to ‘emotional communities’ as a short-hand version where the politics of change were more muted and to encompass a focus on sharing painful stories that coalesce around collective embodiment of lived experiences, engaging other stakeholders through emotions often expressed as empathy, indignation and solidarity (Jimeno, Citation2008).

Our use of the term ‘emotional-political communities’ adapts Jimeno’s to delineate the ways in which affective responses to crisis and gendered violence have been harnessed to produce individual and collective actions more as a process of change. While Jimeno focuses on how the emotional trauma of violence actively creates collective political responses, our emphasis is on how collective emergency responses to crisis can create an awakening among women, especially among survivors of gendered violence. We therefore move beyond Jimeno’s focus on individual sharing of testimony among victims-survivors of gendered violence and the interconnections between informal and formal communities of support, towards a more explicit focus on various forms of pragmatic political resistance tactics led by women. Our conceptualisation of ‘emotional-political communities’ also presents an inverted flow of connections between individual experiences of violence and collective forms of action towards justice. Rather than strictly observing the roles of emotions in contexts of resisting gender-based violence, we construe the emergence of actions and tactics as potentially resignifying various painful lived experiences as violence themselves. In other words, campaigns, support networks, working groups, micropolitical solidarity and even protests work to enable experiences of direct and indirect forms of violence to be identified as such.

Our notion of emotional-political communities is therefore strongly influenced by long-established thinking around feminist organising where women mobilise around economic and social justice issues, and not just as responses to violence as in Jimeno’s version. Our conceptualisation therefore acknowledges how mobilisation around immediate ‘practical needs’ may lead to greater consciousness of gender oppression, especially around gender-based violence (Profitt, Citation1994) to become more ‘strategic’ over time as women challenge gendered power relations (Moser, Citation1993). More recently, Moser (Citation2021) has argued that ‘gender transformation’ involves a framework of three stages: meeting basic needs, empowering women through building assets and providing economic opportunities, as well as seeking legal, institutional and societal change collectively. This shift from practical to strategic is embedded within our configuration of ‘reactive’ and ‘transformative’ emotional-political community building that reflects a move from addressing immediate needs in a crisis towards more longer-term and structural changes. Again, this type of differentiation is missing from Jimeno’s conceptualisation.

Conceptualising emotional-political community building is also directly informed by feminist and especially feminist geographical debates around how women’s responses to male violence need to be understood along a continuum ranging from ‘small acts’ of ‘quiet politics’ to active resistance through leaving abusers and political mobilising (Katz, Citation2004; Pain, Citation2014). In turn, it acknowledges that these practices may be curtailed in contexts of high levels of conflict, fear and poverty (Hume & Wilding, Citation2020; also Datta, Citation2016; Faria, Citation2017). Furthermore, while we focus on ‘reactive’ and ‘transformative’ forms of creating emotional-political communities, we acknowledge that these are not binaries and are themselves inherently diverse as women develop a range of forms of ‘plural resistance’ (Piedalue, Citation2017), ‘defiant tactics’ (Brickell, Citation2020, p. 137), or ‘high risk feminism’ (Zulver, Citation2016). These may entail everyday community-based individual and collective processes that address intimate partner and wider forms of structural and state violence that Amy Piedalue (Citation2022) refers to as ‘slow nonviolence’. Entailing ‘mobilizing family and community members and spaces’ and ‘women’s knowledge sharing’, slow nonviolence focuses on grassroots, feminist ethics of care among marginalised communities where compassion and ‘organic community relationships’ (see also, Jokela-Pansini, Citation2020 on strategies of ‘(self)-care’; Lorde, Citation1988) which are central tenets of our thinking around emotional-political communities.

Much of this research also calls for an explicitly intersectional approach to resistance and practices of social change (Fluri & Piedalue, Citation2017; Piedalue, Citation2022). This is especially important in the context of Brazil where women located at the intersection of various systems of oppression are more likely to experience gendered violence in extreme ways (Santos, Citation2017). Indeed, a large body of work has revealed how anti-Black state and specifically police violence in poor urban communities has severe long-term affective and deadly consequences for Black women (Caldwell, Citation2007; Fernandes, Citation2014; Rocha, Citation2012). This has variously been referred to as ‘sequalae’ as a form of physical and emotional trauma resulting from police violence (Smith, Citation2016) or a ‘slow death’ of anxiety and depression among Black mothers of children killed or injured (Perry, Citation2013). Therefore, emotional-political community building fully integrates an intersectional perspective that recognises how state violence can engender emotional ill-health. Indeed, not only do emotions permeate economic and political realms rather than being contained within bodies and the private sphere (Ahmed, Citation2004), but direct and indirect gendered violence can act as a catalyst for such community building through political actions (Jimeno et al., Citation2018; De Marinis, Citation2018). This resonates with an expression developed by women survivors of state violence in Brazil which calls for the ‘transfiguration of mourning into fight’ (transformar luto em luta) calling women to join forces in solidarity and action, most notably among mothers who have lost their children and partners (Moura & Santos, Citation2008; Rocha, Citation2012).

This leads to the final dimension of our conceptualisation of emotional-political communities in relation to activism and gendered violence during the COVID-19 crisis which clearly postdates Jimeno’s work. There is emerging evidence that grassroots organisations have been providing services in poor urban communities in the absence of state interventions (Gupte & Mitlin, Citation2021). In exploring the ‘repertoires of collective action’ in urban Latin America during COVID-19, Duque Franco et al. (Citation2020) found that delivery of food products and communal kitchens were the main forms of solidarity and community interventions, followed by hygiene and prevention campaigns, and income projects. These were the most effective and widespread in communities with already developed ‘associative fabric’ (also Córdoba et al., Citation2021). Not only have women been the main beneficiaries of assistance reflecting their traditional social roles within households, but collective action has also been instigated by and for women. For instance, feminist collectives have emerged in Mexico to organise food security networks and barter trading together with social media platforms focusing on women’s rights in relation to domestic violence and economic insecurity with emotional bonds and sharing trauma being central to the process (Ventura Alfaro, Citation2020). Similarly, in China, ‘collective spirit and emotional intensity’ has been mobilised through feminist activism against domestic violence (Bao, Citation2020, p. 62). Echoing this nascent work, we argue that COVID-19, while devastating in so many ways, has provided an impetus for building emotional-political communities. Recalling our blurred distinction between reactive and transformative emotional-political communities, we show how women-led initiatives shift from short-term responsive acts into more structuring-propositive practices. This also enables women to perceive their own painful experiences as violence and, consequently, equips them to respond in more strategic and transformative ways dedicated to confronting and preventing direct, indirect, structural and symbolic dimensions of gendered violence. The discussion now moves on to outline the nature of emotional-political community building in the context of Maré in Rio de Janeiro with specific reference to addressing gendered violence.

Contextualising gendered violence in Maré, Rio de Janeiro: background and methodology

Maré is one of the largest and most populous groups of favelas in Brazil, a territory affected by high levels of poverty, inequality, organised crime and public insecurity. It has a population of almost 140,000 people according to its 2013 community-led census, of which 51% are women and 62% identify themselves as mixed-race and black (Redes Da Maré, Citation2013). In a country structurally marked by its colonial history and system of slavery, Rio de Janeiro is especially divided between rich and poor who reside in favelas which overlap with a racial divide (Fernandes, Citation2014). Despite Maré being officially recognised as a neighbourhood within Rio de Janeiro in the 1990s, the territory is stigmatised as a slum detached from the city and it suffers neglect through restricted or unstable access to basic services, transportation and lighting (McIlwaine et al., Citation2021). Against this backdrop, Maré is territorially controlled by various armed groups who act as perpetrators and agents of paralegal state governance (Sousa Silva, Citation2017). Countering this, state security forces frequently make brief but often deadly incursions resulting in systematic violence affecting the daily lives of residents (Wilding, Citation2014). In 2017 alone, there were 41 police incursions that resulted in 42 deaths and 41 injured people (Krenzinger et al., Citation2018). Although the Supreme Court suspended police incursions in Rio’s favelas at the start of the pandemic, there were 16 in 2020 (Redes Da Maré, Citation2021).

In terms of gender-based violence, 35% of women in Brazil have experienced it (Guimarães & Pedroza, Citation2015) with one woman being murdered daily in Rio de Janeiro in 2016 (Krenzinger et al., Citation2018). In Maré, our pre-COVID research showed that 57% of those surveyed suffered one or more forms of gender-based violence (34% physical, 30% sexual and 45% psychological) with young black women being most likely to experience it (69% of black women compared to 55% of mixed-race and 50% of those identifying as white). Intimate partners committed 47% of the violence with more than half occurring in the public sphere (53%; Krenzinger et al., Citation2018; McIlwaine et al., Citation2020). Although men are direct targets, women residents of Maré are direct victims of police incursions, crossfire and fighting, also being emotionally impacted by the terror that dominates life in the territory (also Perry, Citation2013; Smith, Citation2016). They are often harassed by the police to provide information about criminal groups and suffer in their roles as mothers, partners and daughters of the targeting of young, black men by the police’s arbitrary misuse of force (Rocha, Citation2012).

During the initial period of the pandemic in 2020, Marques et al. (Citation2020) note a 17% rise in reporting domestic violence nationally with a 50% increase in domestic violence cases in the first weekend following social distancing in Rio de Janeiro. Despite under-reporting, more than 250 women were victims of violence every day during lockdown in 2020 in the state of Rio de Janeiro, comprising 73,000 women between March and December 2020, of which 61% occurred inside homes (ISP-Instituto de Segurança Pública, Citation2021).

Yet Maré is also a locus of articulated social struggles, many of which are led by women. Women typically openly protest in the face of death or aggression to their families and are the ones who develop alternative household income strategies (45% of women are sole heads of household – Krenzinger et al., Citation2018). They have also been historically active in fighting for the community’s improvements around housing tenure, basic services and public security. With the onset of COVID-19, socio-economic, health and infrastructural injustices have intensified resulting in families (often headed by women) facing hunger, despair and more violence. Reflecting the situation in Maré, a recent survey in 76 Brazilian favelas showed that 68% of residents did not have the means to buy food with 71% experiencing incomes falling by half during the pandemic (Data Favela, Citation2021).

Turning to the methodology, the research outlined here was designed as a co-produced, collaborative feminist project based on a multi-methods framework to capture women-led institutional, community and arts-based initiatives in resisting violence and building dignity in Maré, Rio de Janeiro. This builds on a pre-COVID project on violence against women and girls on the multiscalar nature of such violence in Maré and among Brazilians in London based on a survey with 801 women together with interviews with 20 women and 6 focus groups (Krenzinger et al., Citation2018; McIlwaine et al., Citation2020, Citation2021). Both projects have entailed close partnerships with Redes da Maré, especially through their Casa da Mulheres (House of Women) initiative (who are located within the favela), together with the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. Unsurprisingly, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has caused severe disruptions in the progress of the project. However, following a break in the research for several months while our partners focused on the emergency situation and after multiple online consultations, we decided to continue. This was on the grounds that first, our partners and field researchers were based in the community and could conduct the interviews in a safe and socially distanced manner as appropriate, and second, that the information being gathered was crucial for understanding the effects of the pandemic on women’s lives in general and in relation to gendered violence.

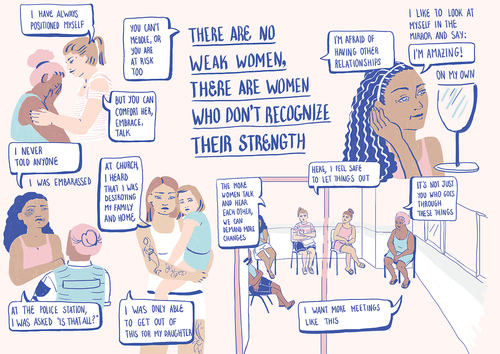

At the time of writing, the research has entailed 32 in-depth interviews with women survivors of violence residing in Maré with diverse profiles in terms of age, racial identity, place of residence and occupation, together with five focus groups to explore their experiences (conducted face-to-face in Portuguese with full protective clothing, distancing and testing made available). These focused on how women dealt with gendered violence through various practices and activities in general and in relation to the pandemic and were based on co-designed interview/focus group schedules developed via two online workshops with women from the community. The interviews and focus groups were voice recorded, transcribed and analysed using thematic analysis. In addition, a visual artist observed four of the five focus groups providing a visual documentation of the discussions registering subjective and sensitive elements (see, ).

Figure 1. Artist’s interpretation of focus group discussion with five women survivors of violence who worked outside of their households (by the artist Mila de Choch).

These were complemented by an additional set of semi-structured interviews with nine female community actors who work in Maré in different organisations supporting women and one beneficiary (all conducted online in Portuguese and voice recorded, transcribed and analysed using thematic analysis). The community actors were involved in two key initiatives: a COVID-19 campaign to distribute food and hygiene goods, and a collaborative support network for women to address gender-based violence (see below). The interviews aimed at capturing women’s roles, strategies and resources within formal and informal support networks addressing gendered violence during times of COVID-19. One of the authors has been integrated into one of the initiatives and has been afforded insights into all stages of its elaboration, with all authors in constant contact online with the field team. The horizontal co-produced mode of practice between research teams in Brazil and the UK secured the continuation of activities. This has also meant that the project partner institutions have had autonomy to decide their own order of activities, timetable, and safety measures according to context-specific guidelines to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Building emotional-political communities to address gendered violence against women in times of COVID-19 in Maré

Not only have multiple community-based and women-led experiences of resistance historically flourished in Maré, but women have always developed tactics and agentic practices to cope with direct and indirect gendered violence. In outlining how emotional-political communities have been created in response to COVID-19, we emphasise how some activities have intensified or reconfigured while others have been created from scratch generated through the emotional forces of the pandemic that have prompted political acts.

While our focus here is on the reactive and transformative forms of emotional-political communities during COVID, it is important to acknowledge that pre-pandemic research revealed that only 52% of women who had experienced gender-based violence disclosed or reported it. This was overwhelmingly through informal means (83%), with only 2.5% reporting to a formal source such as the police. Dealing informally with violence has been even more widespread since the onset of the pandemic. Both pre-COVID and since, the women interviewed identified their main tactics for dealing with both intimate partner and police and armed group violence as ‘immediate management of threat’ (Hume & Wilding, Citation2020, p. 260). This involved removing themselves temporarily from their home through staying with friends or family or remaining at work or church for as long as possible. Clearly, during lockdown, this was no longer possible, putting many women in danger. However, participating in initiatives prior to the pandemic was also shown to provide women with the emotional and economic resources to be able to deal with any subsequent gendered violence. For example, Ingrid, who identified as Asian and was married with two children spoke of her participation at the Casa das Mulheres: ‘It opened my eyes to many things, things that I didn’t know, like what harassment really was and also racism’. In many ways, this reflects Piedalue’s (Citation2022, p. 15) notion of slow non-violence that derives from grassroots women’s collectives who have consistently worked to counter gendered violence against women through gradual intersectional social change rooted in (self)-care (also Jokela-Pansini, Citation2020). We argue that both individual women’s existing associative experiences and the activities of grassroots organisations have intensified during COVID-19 leading in part to the emergence of emotional-political communities.

Building reactive emotional-political communities

The reactive phase of building emotional communities in Maré relates to immediate responses to the emergencies created by COVID-19 which negatively affected women’s lives in terms of their disproportionate reproductive responsibilities, hunger, health and hygiene care and gendered violence. Women have emerged as key architects and beneficiaries of the two main programmes developed as initial responses to COVID-19 as part of ‘repertoires of collective action’ in the face of government neglect (Duque Franco et al., Citation2020).

Women-led emergency responses to COVID-19

Focusing first on the institutional collective response, this stage related to women leaders in organisations developing ways to meet basic food, hygiene and health needs through developing a campaign as noted by the coordinator of Casa das Mulheres:

Our organisation completely reorganised itself during the pandemic, in order to come up with effective rapid responses for the urgent issues that were arising, particularly those related to hunger, unemployment and of course, health-related problems.

This entailed the ‘Maré Says No to Coronavirus’ (Campanha Maré Diz Não ao Coronavírus) initiated by our partner organisation Redes da Maré based on early realisation of the potentially devastating impacts of the pandemic on the poor, mostly black women residents. The campaign started in March 2020 premised on six fronts of action: food security; assistance to the homeless; income generation; access to health rights, care and prevention; production and dissemination of secure information; and support for local artists and cultural groups. The distribution of basic food baskets and personal hygiene items were organised based on assessing families according to various criteria of social vulnerability, resulting in baskets and hygiene kits delivered to 17,648 families directly benefiting 54,709 people between March and December 2020. These core activities were not only led by women but also mainly delivered by them.

Gradually, the campaign developed a rights and health care structure. This encompassed an online service to address cases of violations of rights and violence, individual follow-up of health cases, ensuring access to medical treatments, monitoring cases of COVID-19, mass testing, and providing telemedicine services. This structure began with the identification of demands for access to health during the distribution of basic food baskets and took shape in a complex articulation among different services and institutions in Maré and beyond. From a process that began as an emergency response to provide food in lockdown and its associated economic instability, a multifaceted action was also created through project Health Connection (Conexão Saúde) that gathered six key institutions into a partnership within and beyond Maré. Started in September 2020, by November the project had already carried out 4,769 tests, 1,338 medical consultations, 729 psychological consultations, and included 155 people in the Safe Home Isolation programme. The substantial data generated on COVID-19 also made it possible to develop a series of briefs offering information for the local population, challenging the underreporting of official data in favelas (also Gupte & Mitlin, Citation2021).

Although all genders were involved, women run and operate the centrepieces of the campaign and project. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this reflects women’s wider roles in Maré as noted by one of the campaign’s collaborators and the coordinator of Casa das Mulheres:

Women play a major role in the history of struggles for improvement in Maré. Redes da Maré’s own history is very much intertwined with women’s struggles … 80% of its collaborators are women and the public we serve are much more women than men.

Women were not only the main organisers, but also the primary beneficiaries given they were bearing major reproductive burdens and dealing with severe income insecurity and hunger among their family members. Within an estimated group of beneficiaries of more than 54,000 residents, most of the households (79%) who resorted to campaign donations were headed by women, aged between 20 and 49, with 71% identifying as black and mixed-race. Most were also caring for vulnerable family members with 42% having more than one child up to 6 years old, 19% caring for an elderly person over 60, and 44% having one or more residents with chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension or respiratory problems. In terms of income, almost two-thirds of those assisted (62%) reported that everyone in their household was unemployed with 66% with family income below half a minimum wage, with a further 12% facing extreme poverty and hunger with no income at all (Redes Da Maré, Citation2020). Women-led initiatives were therefore helping other women to deal with the severe and intersectional care and livelihood burdens of the pandemic, in part through forming emotional-political communities of activity to reactively address the emergency. This was explained by a worker at Conexão Saúde:

It is very difficult to get men to partake in forms of care and responsibility towards their children and other household members. We dealt with very complex cases of women who were sick and were the sole providers in their household. They were desperate … they would often turn to their mother … this is the cycle of women … and this issue is inherent in the networks of support for women.

Women-led networks to address COVID-19

The second women-led initiative developed was the collaborative ‘Support Network for Women in Maré’ (RAMM – Rede de Apoio às Mulheres da Maré), initiated in May 2020 by the organisation Fight for Peace (Luta Pela Paz). It was established out of concern for the increase in domestic violence due to lockdown measures in the overcrowded homes of Maré. The RAMM identified the need for coordination among professionals from different areas of care, including public policy arenas, local civil society organisations and the neighbouring university, the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ – our project partner) with the aim of building joint strategies for women in Maré. From the outset, the collective and horizontal running of RAMM was based on weekly meetings to define priority actions among its seven regular participants and included public events to reach up to 40 collaborating institutions across the state of Rio de Janeiro. RAMM’s first action was to construct an ‘integrated workflow’ through a participatory process for the mapping of services, policies, and meetings with representatives based on solidarity and an urgent need to address domestic violence. This workflow was disseminated through public events and online strategies, as explained by one of RAMM’s members: ‘everything is being built collectively … Now we have a website where users can access information about services. But it is also a source of information to workers dealing with a case of violence against women.’ In many ways, the RAMM has entailed building a reactive emotional-political community in itself.

With the women-led emergency infrastructure in place, individual women residents began to inhabit and construct the emotional-political communities of the campaign and the RAMM. In responding to immediate needs, often seen as adversities rather than structural violence, they began to get involved in other forms of collective engagements, including participating in the campaign as a form of income generation. As explained by one of the coordinators of Conexão Saúde, many residents were gradually recruited, most of whom were women left with no income due to the pandemic. This included 54 seamstresses sewing facemasks and 22 cooks preparing daily meals for free distribution (13 men were also involved as drivers to deliver donations). In generating a modest income, both addressing practical needs and some asset and capability building occurred (reflecting Moser’s, Citation2021 second phase of gender transformation to ensure livelihood security). In the face of the psychological and economic tolls that COVID has wreaked, these jobs have provided important safety nets as noted by Monica, one of the cooks in the campaign, about her co-workers:

There has been huge demand from women suffering from depression and anxiety, among other things. This is the effect the pandemic is having … women, whose lives are made even more difficult by COVID. Many of their husbands … lost their jobs, so the income they receive is now practically the only income they have to get them through the pandemic.

By being involved in the collective action, some women narrated a personal journey that changed their views about their painful experiences as women living in Maré. In some cases, the seeds of these processes were pre-COVID; Monica, for example, further elaborated a realisation process that occurred several years earlier when she joined the cooking cooperative: ‘So I began to really understand all the problems of gender-based violence in Maré, of which we know there are many … It was there that I recognised myself as a woman who was going through things that other women were going through too’.

Other women experienced it during the COVID organising. A change of posture was noticeable and acknowledged by women particularly in valuing collective spaces to talk about their everyday struggles and experiences of violence. This was captured in the focus groups where participating women frequently mentioned the value of the sessions (see, ). This was further noted by a member of RAMM who works with women survivors of violence:

At first the issue of violence didn’t come up much … so when they first meet it is hard to talk about any of that … but as my therapeutic work is very corporeal … the issue starts to resurface in other forms of building intimacy between participants. As they begin to know each other … the possibility of speaking about it opens up, and to tell each other “no, you can’t allow him to do this to you.”

These processes reflect classic feminist pedagogical practices rooted in popular education methodology (Freire, Citation1970; hooks, Citation1994) as well as Lorde’s (Citation1988) notion of ‘self-care’. From this point of realisation, where violence clearly emerges in women’s memories and lifelong sufferings, the seeds of action can be sown (Hume & Wilding, Citation2020; Piedalue, Citation2017, Citation2022; Profitt, Citation1994). A coordinator at Casa das Mulheres made this point in relation to state negligence in the favela: ‘Women in Maré create their own forms of informal resistance and resilience … precisely from this shortfall, this absence, this ineffectiveness. Women are incredibly inventive’. The key issue here is how these practices of resilience and reworking have emerged as part of the reactive emotional response to the crisis and suffering which have the potential to be more transformative (Jimeno et al., Citation2018; Pain, Citation2014).

Building transformative emotional-political communities

Reactive emotional-political communities thus provide the foundation for more transformative ones that reflect strategic change along a continuum of transformation or ‘plural resistance’ (Piedalue, Citation2017), even if these are not linear and ultimately ‘slow’ (Jimeno, Citation2008; Piedalue, Citation2022). These dynamic processes resonate with Moser’s (Citation2021) third stage in her gender transformation framework in addressing unequal power relations and seeking legal, institutional and societal change. Yet this neglects the emotional-affective aspects of how transformation may be engendered intersectionally through compassion and care for themselves and others, which play out individually and collectively in women’s lives (Ho & Maddrell, Citation2021; Jokela-Pansini, Citation2020), that is central to our conceptualisation of transformative emotional-political communities.

Strategic transformations through individual change

At the individual level, women in Maré have begun to re-signify their personal painful experiences as violence through creating transformative collective engagements. Renata, a 24-year-old white, lesbian student who grew up seeing her abusive father attacking her mother and who was responsible for making her take action against him, spoke of transformations she noticed in herself after getting involved in a project prior to and during the pandemic. This entailed counselling, personal development and judo classes run by Fight for Peace which led to her creating a project to teach women to defend themselves: ‘we have group conversation sessions, self-defence lessons, physical exercises, and today we have 60 women enrolled’. Understanding that her students would potentially be at risk from violent partners at home, Renata continued to provide self-defence classes for women during the pandemic through weekly online sessions on Instagram, which were then transferred back to face-to-face sessions.

Participation in collective spaces before and during the pandemic was therefore perceived as life-changing for some individual women. This was expressed in the opportunities for talking about violence that had been silenced for many years. These arenas enabled subjective changes based on the circulation of shared emotions in practical and strategic ways. Silvia, a 56 year-old white survivor of violence who was divorced with a son, worked as a cook in the Casa das Mulheres culinary programme pre-COVID and was also part of the emergency action for meals for distribution. She spoke of how her work in the culinary course gave her the self-confidence, strength and financial autonomy to leave her abusive ex-husband.

Strategic transformations through organisational change

More strategic transformation occurred in the institutional functioning of the two initiatives as the emotional and political coalesced. As the pandemic unfolded in 2020, the campaign and network underwent shifts from providing emergency basic needs towards working on rights and prevention. One of the collaborators of the Maré Says No to Coronavirus campaign noted this reformulation of organisational structure and priorities based on demands brought by women and the need for more strategic attention to gendered violence:

It is in the context of the pandemic that we realize that it is not only armed violence that affects people … and everything that was already very bad in terms of social policies, worsened during the pandemic … How are we going to support this woman so that this woman somehow builds her support network and is able to get out of this situation?

Drawing on the existing capacity of Redes da Maré and partners, this entailed widening the scope of services on-site, mobile teams, remote assistance and online referrals. The distribution of food and hygiene baskets also facilitated new data collection around community needs and structural deficits in providing basic safety measures recommended by the World Health Organization including information about COVID-19, public services and citizen rights. In recognising women’s disproportionate ‘intersectional burdens’ (Ho & Maddrell, Citation2021), the Casa das Mulheres introduced a focus on women’s health, reproductive and mental health and self-care. As part of this, they developed a specific strategic initiative on reproductive rights, providing individual information, distribution of menstrual cups and birth control.

A similar dynamic unfolded concerning the need for basic information on access to social and judicial rights, including registering for the state’s COVID emergency aid – a challenging process requiring access to technology and the internet. In response, remote and on-site legal and psychosocial assistance as part of the Maré de Direitos (Maré of Rights) project were provided in addition to home visits, enabling access to assistance with making COVID-related judicial claims to hospitalization and emergency aid. Gradually, information and assistance not directly related to COVID-19 was sought around livelihoods, professional training, adult and early childhood education, school registration, as well as the persisting armed violence and police brutality.

The Casa das Mulheres also adapted its remote services offered to women survivors of gendered violence. Recognising the challenges of help-seeking due to lack of privacy and the continuous presence of the aggressor in the home, a hybrid service was created allowing face-to-face access within scheduled times, replacing the previous ‘open doors’ service. This provoked a permanent institutional reflection towards maintaining a hybrid service allowing women from across Maré to attend, particularly those who were previously excluded due to distance or by residing in territories belonging to rival armed groups.

These transitions from reactive to strategic activities were also evident in the RAMM as they moved from providing service information towards capacity-building for social workers and community actors assisting women survivors of gendered violence. This involved opening the ‘workflow’ for new institutions and participants, as a member of RAMM reflected: ‘A change occurs from the moment that we recognize ourselves as a network, this starts to be thought collectively in an intentional way, and not only reactively.’ The culmination of this process was a programme of ‘Capacity-building in assistance to women in Maré’ developed from February to April 2021, aimed at the participation of key workers from different women’s rights services. The programme took place online with 24 institutions and 35 participants from civil society organizations, social movements, women’s service centres, public health care units, councils, universities, and statutory services. The topics addressed were gender and sexuality, violence against disabled women, networks for challenging gendered violence, intersectional experiences of violence, and the singularity of Maré. The discussions revolved around case studies where participants shared their experiences, discussed referrals, and how to improve services. From this collective experience, in which emotional-affective energies were embedded, grew an inter-institutional workflow including a WhatsApp group connecting participating institutions and key workers allowing continuous sharing of experiences, reading and work guidelines. The RAMM has become a new collective body encompassing a transformative emotional-political community of participants wanting to address violence against women during the crisis through strategic work around rights yet underpinned by care and compassion. In the face of endemic urban and structural violence, the process both individually and collectively is gradual and often fragmented, yet there is a feminist potency created by the crisis that has been used to improve the lives of women in the territory.

Conclusions

This paper has responded to the call to interrogate the ‘emotional-affective geographies’ of the COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of mutual support and activism (Maddrell, Citation2020; also Duque Franco et al., Citation2020). It also addresses a wider call to centre gendered violence against women in its multiple forms across private and public spheres within feminist geography (Brickell & Maddrell, Citation2016). These have been examined in relation to women’s individual and collective responses to COVID-19 in contexts of gendered domestic, structural, urban and endemic state violence in Maré, Rio de Janeiro. The paper also contributes to feminist geographical debates on intersectional forms and ‘defiant tactics’ of ‘plural resistance’ and ‘slow nonviolence’ (Brickell, Citation2020; Piedalue, Citation2017, Citation2022) developed among women in contexts of heightened marginalisation and exclusion in ways that reflect ‘small acts’ and ‘quiet politics’ (Pain, Citation2015, Citation2019). It does so through the adaptation of the concept of ‘emotional communities’ developed by Colombian anthropologist, Myriam Jimeno, to examine how emotional bonds created among survivors of violence are reconfigured into political action and situated agency (Jimeno et al., Citation2018).

Yet our notion of ‘emotional-political communities’ differs from Jimeno’s in a number of ways. First, is that we shift from a focus on individual women’s sharing of testimony of violence to engender political change, to arguing that individual and collective emergency reactions to crisis can bring about change as a process, especially among survivors of gendered violence. Second, we highlight how the emergence of emotional-political communities and the tactics that underpin them can allow women to resignify and identify painful lived experiences as violence. Third, emotional-political communities are differentiated into ‘reactive’ and ‘transformative’ forms which reflect the shift from how women as well as organisations themselves need to address both immediate practical needs as well as strategic structural changes to cope with and prevent gendered violence in the longer term (Moser, Citation2021). Fourth, our idea of emotional-political communities places compassion and (self)-care at the core as an integral element (Jokela-Pansini, Citation2020; Lorde, Citation1988), and not just as an immediate response to crisis or violence as in Jimeno’s version. Finally, our emotional-political community building recognises intersectionality much more explicitly. This is especially important in the context of Brazil where marginalised black women have disproportionately suffered in individual, familial and collective ways from gendered and endemic urban violence and the ‘slow death’ or ‘sequalae’ of anxiety at the hands of state and non-state perpetrators (Smith, Citation2016; Perry, Citation2013; see also, Hume & Wilding, Citation2020; Zulver, Citation2016).

Emotional-political community building is thus a potential non-linear responsive-reactive and structuring-propositive mechanisms to dealing with the devastating effects of COVID-19 among women and support organisations in marginalised territories. Building such communities can lead to affective and political recasting of painful lived experiences by women. While for some, the seeds were planted in pre-pandemic times, others have become more engaged in their responses to COVID. However, although women-led emotional-political communities have emerged as the backbone of responses to the pandemic, literally saving lives and livelihoods, it is essential to remember that they have done so largely in the absence of the state and in the case of Maré, despite continual state aggression against those struggling to survive favelas.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval has been granted for this research from the King’s College London Research Ethics Committee (HR-19/20-18,918).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Andreza Dionisio Pereira who assisted in conducting the field work in Maré as well as Paul Heritage and Renata Peppl from Queen Mary University of London and People’s Palace Projects, as well as Eliana Sousa Silva from Redes da Mare and Alba Murcia for research assistance. We are also grateful to Mila de Choch for her artistic interpretation of the focus group discussion in . Most of all, we extend our gratitude to the women of Maré who were interviewed as part of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agüero, J. M. (2021). COVID-19 and the rise of intimate partner violence. World Development, 137(105217), 2–7. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105217.

- Ahmed, S. (2004). The cultural politics of emotions. Routledge.

- Azcona, G., Bhatt, A., Encarnacion, J., Plazaola-Castaño, J., Seck, P., Staab, S., & Turquet, L. (2020). From insights to action: Gender equality in the wake of COVID-19. UN Women. http://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/09/gender-equality-in-the-wake-ofcovid-19

- Bao, H. (2020). “Anti-domestic violence little vaccine”: A Wuhan-based feminist activist campaign during COVID-19. Interface, 12(1), 53–63. https://www.interfacejournal.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Interface-12-1-Bao.pdf.

- Boesten, J. (2012). The state and violence against women in Peru. Social Politics, 19(3), 361–382. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxs011

- Brickell, K. (2015). Towards intimate geographies of peace? Transactions of the Institute of. British Geographers, 40(3), 321–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12086

- Brickell, K. (2020). Home SOS: Gender, violence and survival in crisis ordinary Cambodia. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Brickell, K., & Maddrell, A. (2016). Geographical frontiers of gendered violence. Dialogues In Human Geography, 6(2), 170–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820616653291

- Caldwell, K. L. (2007). Negras in Brazil. Rutgers University Press.

- Chen, A. L. Q. (2020). A socio-spatial research agenda on the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Sociologica, 63(4), 453–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699320961811

- Córdoba, D., Peredo, A. M., & Chaves, P. (2021). Shaping alternatives to development: Solidarity and reciprocity in the Andes during COVID-19. World Development, 139, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105323

- Data Favela. (2021). Pandemia na favela [Pandemic in the favela]. Instituto Locomotiva. https://www.rioonwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/2forum_datafavela_divulg_0.pdf

- Datta, A. (2016). The intimate city. Urban Geography, 37(3), 323–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2015.1096073

- De Marinis, N. (2018). Political-affective intersections: Testimonial traces among forcibly displaced indigenous people of Oaxaca, Mexico. In M. Macleod & N. De Marinis (Eds.), Resisting violence: Emotional communities in Latin America (pp. 143–161). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Duque Franco, I., Ortiz, C., Samper, J., & Millan, G. (2020). Mapping repertoires of collective action facing the COVID-19 pandemic in informal settlements in Latin American cities. Environment and Urbanization, 32(2), 523–546. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247820944823

- Faria, C. (2017). Towards a countertopography of intimate war: Contouring violence and resistance in a South Sudanese diaspora. Gender, Place & Culture, 24(4), 575–593. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1314941

- Fernandes, F. L. (2014). The construction of socio-political and symbolical marginalisation in Brazil. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 4(2), 53–67. http://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_4_No_2_Special_Issue_January_2014/4.pdf.

- Fluri, J. L., & Piedalue, A. (2017). Embodying violence: Critical geographies of gender, race, and culture. Gender, Place & Culture, 24(4), 534–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1329185

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Herder and Herder.

- Guimarães, M. C., & Pedroza, R. L. S. (2015). Violência contra a mulher: Problematizando definições teóricas, filosóficas e jurídicas [Violence against women: Questioning theoretical, philosophical and legal definitions]. Psicologia e Sociedade, 27(2), 256–266. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-03102015v27n2p256

- Gupte, J., & Mitlin, D. (2021). COVID-19: What is not being addressed. Environment and Urbanization, 33(1), 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247820963961

- Ho, E. L., & Maddrell, A. (2021). Intolerable intersectional burdens. Social & Cultural Geography, 22(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2020.1837215

- hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to transgress. Routledge.

- Hume, M., & Wilding, P. (2020). Beyond agency and passivity. Urban Studies, 57(2), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019829391

- ISP-Instituto de Segurança Pública. (2021). Monitor da violência doméstica e familiar contra a mulher no período de isolamento social [Monitor domestic and family violence against women in the period of social isolation]. http://www.ispvisualizacao.rj.gov.br/monitor/index.html

- Jimeno, M. (1998). Identidad y experiencias cotidianas de violencia [Identity and everyday experiences of violence]. Revista Análisis Político, 33(1), 32–46. https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/anpol/article/view/78439.

- Jimeno, M. (2008). Lenguaje, subjetividad y experiencias de violencia [Language, subjectivity and experiences of violence. In F. Ortega (Ed.), Veena Das: Sujetos del dolor, agentes de dignidad (pp. 261–291). Bogotá.

- Jimeno, M., Varela, D., & Castillo, A. (2018). Violence, emotional communities, and political action in Colombia. In M. Macleod & N. De Marinis (Eds.), Resisting violence: Emotional communities in Latin America (pp. 23–52). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jokela-Pansini, M. (2020). Complicating notions of violence. EPC: Politics and Space, 38(5), 848–865. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420906833.

- Kabeer, N., Razavi, S., & Rodgers, Y. V. M. (2021). Feminist economic perspectives on the COVID-19 pandemic. Feminist Economics, 27(1–2), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2021.1876906

- Katz, C. (2004). Growing up global. University of Minnesota Press.

- Krenzinger, M., Sousa Silva, E., McIlwaine, C., & Heritage, P. (eds.). (2018). Dores que libertam [Pains that set free]. Attis.

- Lorde, A. (1988). A burst of light: Essays. Firebrand.

- Macleod, M., & De Marinis, N. (eds.). (2018). Resisting violence: Emotional communities in Latin America. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Maddrell, A. (2020). Bereavement, grief, and consolation: Emotional-affective geographies of loss during COVID-19. Dialogues in Human Geography, 10(2), 107–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620934947

- Marques, E. S., Moraes, C. L., Hasselmann, M. H., Deslandes, S. F., & Reichenheim, M. E. (2020). A violência contra mulheres, crianças e adolescentes em tempos de pandemia pela COVID-19 [Violence against women, children and adolescents in times of a COVID-19 pandemic]. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 36(4), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00074420

- McIlwaine, C., Krenzinger, M., Evans, Y., & Sousa Silva, E. 2020. Feminised urban futures, healthy cities and violence against women and girls (VAWG). In M. Keith & A. A. de Souza Santos. Eds., Urban transformations and public health in the emergent city pp.55–78. MUP Press. https://www.manchesteropenhive.com/view/9781526150943/9781526150943.00008.xml

- McIlwaine, C., Krenzinger, M., Rizzini Ansari, M., Evans, Y., & Sousa Silva, E. (2021). Negotiating women’s right to the city: Gender-based and infrastructural violence against Brazilian women in London and residents in Maré, Rio de Janeiro. Revista de Direito da Cidade, 13(2), 954–981. https://doi.org/10.12957/rdc.2021.57564.

- Morrow, O., & Parker, B. (2020). Care, commoning and collectivity. Urban Geography, 41(4), 607–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1785258

- Moser, C. (1993). Gender planning and development. Routledge.

- Moser, C. (2021). From gender planning to gender transformation. International Development Planning Review, 43(2), 205–229. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2020.9

- Moura, T., & Santos, R. (2008). Transformar o luto em luta: Sobreviventes da violência armada. Oficina do CES, 307. Universidade de Coimbra. https://estudogeral.sib.uc.pt/handle/10316/11077

- Pain, P. (2014). Seismologies of emotion: Fear and activism during domestic violence. Social & Cultural Geography, 15(2), 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2013.862846

- Pain, R. (2015). Intimate war. Political Geography, 44, 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.09.011

- Pain, R. (2019). Chronic urban trauma. Urban Studies, 56(2), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018795796

- Perry, K. K. Y. (2013). Black women against the land grab. University of Minnesota Press.

- Piedalue, A. D. (2017). Beyond ‘Culture’ as an explanation for intimate violence. Gender, Place & Culture, 24(4), 563–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2016.1219323

- Piedalue, A. D. (2022). Slow nonviolence: Muslim women resisting the everyday violence of dispossession and marginalization. EPC: Politics and Space, 40(20), 373–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654419882721

- Profitt, N. J. (1994). Resisting violence against women in Central America: The experience of a feminist collective. Canadian Social Work Review, 11(1), 103–115. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12322384/.

- Rajah, V., & Osborn, M. (2020). Understanding women’s resistance to intimate partner violence: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 152483801989734. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019897345

- Redes da Maré. (2013). Censo populacional da Maré [Population census of Maré]. Redes da Maré. https://apublica.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/censomare-web-04mai.pdf

- Redes da Maré. (2020). Maré diz não ao coronavírus: Relatório de atividades da campanha [Maré says no to coronavirus: Campaign activity report]. Redes da Maré. https://www.redesdamare.org.br/media/downloads/arquivos/RdM_Relatorio_campanha.pdf

- Redes da Maré. (2021). Boletins anuais de direito à segurança pública na Maré [Annual bulletins on the right to public security in Maré]. Redes da Maré. https://www.redesdamare.org.br/br/info/22/de-olho-na-mare

- Rocha, L. O. (2012). Black mothers’ experiences of violence in Rio de Janeiro. Cultural Dynamics, 24(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0921374012452811

- Santos, S. (2017). Interseccionalidade e desigualdades raciais e de gênero na produção de conhecimento entre as mulheres negras. Vozes, Pretérito & Devir, 7(1), 106–120. http://revistavozes.uespi.br/ojs/index.php/revistavozes/article/view/150.

- Smith, C. A. (2016). Facing the dragon: Black mothering, sequelae, and gendered necropolitics in the Americas. Transforming Anthropology, 24(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/traa.12055

- Smith, J., Davies, S. E., Feng, H., Gan, C. C. R., Grépin, K. A., Harman, S., Herten-Crabb, A., Morgan, R., Vandan, N., & Wenham, C. (2021). More than a public health crisis: A feminist political economic analysis of COVID-19. Global Public Health, 16(8–9)1364–1380. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1896765 Advance online publication. Global Public Health

- Sousa Silva, E. (2017). A ocupação da Maré pelo Exército brasileiro: Percepção de moradores sobre a ocupação das Forças Armadas na Maré. Redes da Maré. https://www.redesdamare.org.br/media/livros/Livro_Pesquisa_ExercitoMare_Maio2017.pdf

- UN Women. (2020). COVID-19 and violence against women and girls (EVAW COVID-19 briefs). https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/04/issue-brief-covid-19-and-ending-violence-against-women-and-girls#view

- Ventura Alfaro, M. J. (2020). Feminist solidarity networks have multiplied since the COVID-19 outbreak in Mexico. Interface, 12(1), 82–87. https://www.interfacejournal.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Ventura-Alfaro-1.pdf.

- Wilding, P. (2014). Gendered meanings and everyday experiences of violence in urban Brazil. Gender, Place and Culture, 21(2), 228–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2013.769430

- Zulver, J. M. (2016). High risk feminism in El Salvador. Gender and Development, 24(2), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2016.1200883