ABSTRACT

This paper advances theoretical developments in critical toponymies through focusing on the renaming of South China Sea Islands and everyday use of names by fishermen in Hainan, China. Undergoing a series of historical renamings associated with European colonial influences and claims of sovereignty by the Chinese state, multiple official and vernacular toponymic systems co-exist and operate in complex ways in everyday life. By focusing on complexities in the everyday usage of these co-existing toponymic systems, this paper develops calls in the literature to engage with a more complex understanding of the operation of power in naming beyond a focus on a power/resistance dichotomy. Whilst acknowledging the role of political power, it develops this by analysing how renaming is also influenced by social and demographic change, developments in other areas such as heritage, and technological changes, which have received scant attention in the critical toponymies literature. The paper explores the naming of oceanic features to shift the focus of analysis away from the literature’s concentration on cities and street names. Overall, the paper argues for a more nuanced and diversified approach to analyzing critical toponymies.

Résumé

Este artículo avanza los desarrollos teóricos en toponimias críticas al centrarse en el cambio de nombre de las Islas del Mar de China Meridional y el uso cotidiano de nombres por parte de los pescadores en Hainan, China. Sometidos a una serie de cambios de nombre históricos asociados con las influencias coloniales europeas y los reclamos de soberanía por parte del Estado Chino, múltiples sistemas toponímicos oficiales y vernáculos coexisten y operan de manera compleja en la vida cotidiana. Al centrarse en las complejidades del uso cotidiano de estos sistemas toponímicos coexistentes, este artículo desarrolla llamados en la literatura para comprometerse con una comprensión más compleja de la operación del poder al nombrar más allá de un enfoque en una dicotomía poder/resistencia. Si bien el documento reconoce el papel del poder político, lo desarrolla analizando cómo el cambio de nombre también está influenciado por el cambio social y demográfico, desarrollos en otras áreas como el patrimonio y los cambios tecnológicos, que han recibido poca atención en la literatura crítica de toponimia. El artículo explora la denominación de las características oceánicas para desviar el enfoque del análisis de la concentración de la literatura en ciudades y nombres de calles. En general, el artículo aboga por un enfoque más matizado y diversificado para analizar las toponimias críticas.

Resumen

Cet article présente des avancées théoriques dans le domaine de la toponymie critique en se concentrant sur les changements de noms des îles de la mer de Chine méridionale et l’utilisation quotidienne des noms par les pêcheurs de l’île de Hainan, en Chine. Avec des changements de noms successifs au fil de leur histoire, liés à l’influence coloniale européenne et aux revendications territoriales de la Chine, plusieurs systèmes toponymiques officiels et vernaculaires co-existent et fonctionnent de manière compliquée dans la vie de tous les jours. En se concentrant sur les complexités de l’usage quotidien de ces systèmes, cet article fait appel à la recherche pour s’engager dans une compréhension plus subtile de l’opération du pouvoir dans l’acte de donner un nom au-delà d’une focalisation sur la dichotomie pouvoir/résistance. Tout en reconnaissant le rôle du pouvoir politique, il approfondit avec une analyse concernant la façon dont le changement de nom subit aussi l’influence des évolutions sociales et démographiques, des développements dans d’autres sphères, telles que le patrimoine, et les progrès technologiques, qui ont reçu peu d’attention dans la recherche en toponymie critique. Il explore les noms des lieux océaniques pour rediriger l’objectif de l’analyse et l’éloigner de la recherche concentrée sur les noms de villes et de rues. De manière plus générale, cet article se prononce en faveur d’une approche plus diverse et plus nuancée de l’analyse de la toponymie critique.

Introduction

The study of place naming, or toponymy, has experienced a critical turn as geographers have moved beyond the traditional focus on etymology and taxonomy (Rose-Redwood et al., Citation2010) to interpreting toponyms within their broader socio-political context, and especially the role they play as ‘symbols of memory or socio-political ideology’ (Wanjiru & Matsubara, Citation2017, p. 3). Critical toponymies has expanded to include its contested cultural politics, political economy, and the affective dimensions of naming and renaming. The critical turn, so far, is not notable in Chinese studies of place naming (Ji et al., Citation2016), although a few studies (mostly in Chinese) have paid attention to the power relations, cultural memories, and commercialization of place (re-)naming (see, Ji, Citation2018; Ji et al., Citation2016; Li & Feng, Citation2015; Liu et al., Citation2017; Wei, Citation2016). Analysis of the everyday use of toponyms remains a neglected area, although popular or everyday responses to (re)naming is emerging as an increasingly important topic (Creţan & Matthews, Citation2016; Light & Young, Citation2014), but such studies have maintained a relatively narrow focus on resistance to renaming.

To develop this field this article interrogates the complex interaction of historical, official, and vernacular toponymies of the South China Sea Islands (SCSI). The South China Sea (SCS) is located in the Western Pacific Ocean and covers c.3.5 million square kilometers bordering China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Brunei, and the Philippines. Located at the intersection of the Western Pacific and the Indian Ocean, and straddling the Indo-Pacific Region’s international shipping lanes, it is of considerable strategic importance. Since the 1970s, territorial conflicts focused on the SCS have been central to relationships between China and some of its Southeast Asian neighbours, and both the sea and its mostly uninhabited islands, rocks, and reefs have been subject to competing claims of sovereignty. This has been expressed through competing toponyms, including Southeast Asia Sea, Bien Dong Sea, and Viet Nam Sea (claimed by Vietnam); the West Philippine Sea (the Philippines); and the Borneo Sea (Malaysia). In 1980 the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China claimed that China has indisputable sovereignty over the Xisha Islands and Nansha Islands. Politically, the toponyms of the SCSI have played a role in claims of sovereignty. While an official toponymy was promulgated to this end by the Chinese government in 1983, which in itself intersects in complex ways with previous historical and political rounds of naming, a vernacular toponymy of the SCSI also co-exists in the everyday life of Hainan fishermen. This vernacular toponymy has a complex relationship with the official toponymy which cannot simply be understood through the lens of resistance.

We therefore advance recent arguments in critical toponymies by calling for a more nuanced approach to the operation of power in renaming which conceptualizes it as a more complex and diffuse process than the top-down hegemonic imposition of, and bottom-up resistance to, new names. We go beyond political power alone to consider the intersection of state power with other processes which are neglected in the critical toponymies literature – socio-economic change, demographic change, the ‘heritagisation’ of names, and technological change. Our analysis of renaming and the everyday use of the names of sea features in Hainan and the SCS diversifies the contexts in which critical toponymies have been considered beyond urban street names and cases characterized by revolutionary political change, to consider multiple and more ambiguous toponymic systems.

Following a critical literature review the paper introduces the naming processes and meanings of the official and vernacular toponymies, the latter particularly as recorded in Genglubu – guides written by Hainan fishermen recording navigation routes and other information for fishing in the SCS. The paper then explores the everyday responses of Hainan fishermen to the two sets of toponymies of SCSI, including their use and recognition of toponyms, and attitudes to renaming. The analysis explores how Hainan fishermen’s everyday responses to official toponyms of SCSI are shaped by a range of factors including, but also beyond, resistance to state power.

Critical toponymies beyond the power/resistance framework – everyday geographies of toponymies

The critical toponymies literature has analysed how naming is imbricated in the relationship between politics, power and place (e.g., Alderman, Citation2000, Citation2003; Azaryahu, Citation1996; Hui, Citation2019; Marin, Citation2012; Rose-Redwood, Citation2008a; Yeoh, Citation1992, Citation1996). As Berg and Kearns (Citation1996) argued, place naming is part of the social construction and contestation of place and part of the production and reproduction of the symbolic and material order, a way of ‘norming’ or legitimating hegemonic power relations. For Rose-Redwood et al. (Citation2018a, p. 309) the process of naming is a ‘performative enactment of sovereign authority over … spatial organization … ’.

Regimes use naming as part of their attempts to impose power onto socio-spatial relations, for example, in colonial (e.g., Yeoh, Citation1992, Citation1996) or state-socialist (e.g., Light et al., Citation2002) contexts. Change in political regimes has often been accompanied by attempts to reinforce hegemony by changing the toponymic landscape, particularly in post-colonial, post-socialist, and post-Apartheid contexts. Where the critical toponymies literature has examined ‘bottom-up’ or popular responses to such ‘toponymic cleansing’ (Rose-Redwood et al., Citation2010), it has focused on resistance to renaming (e.g., Alderman, Citation2002, Citation2003; Alderman & Inwood, Citation2013; Alderman & Reuben, Citation2020; Kearns & Berg, Citation2002; Rose-Redwood, Citation2008b; Wideman & Masuda, Citation2018). Opposing the actions of the state is less common in the Chinese political context compared to some of the contexts in which the critical toponymies literature has analysed resistance, but there are nonetheless some examples of resisting renaming in China, such as public responses to the renaming of the city of Huizhou as Huangshan (Ji, Citation2018). By considering different contexts we can diversify our understanding of how power operates in toponymic processes.

This literature has generated valuable insights into the intersection of power, landscape, and (re-)naming, but here we seek to advance recent calls for a more nuanced understanding of how re-naming works as an expression of power beyond a power/resistance dichotomy. As Rose-Redwood et al. (Citation2010, p. 466) argued, ‘critical place-name scholarship risks becoming a bit too predictable and formulaic in its repetitious invocations of toponymic domination and resistance.’ Critical toponymies is

… in a period of active theory construction in which scholars are expanding and problematizing conventional understandings of how toponymic inscriptions operate as technologies of power inside and outside the context of formal political regimes, resistance movements, and people’s official and unofficial performances of identity. (Rose-Redwood et al., Citation2018b, p. 7)

We argue that the literature has been too focused on power to the neglect of a range of other processes – e.g., social and economic changes, demographic and generational changes, heritage, and technology – which intersect with power to a greater or lesser degree in certain times and places. We consider a context in which dual and often multiple toponymies are performed within a diversity of intersecting and/or parallel official and everyday processes, operating inside and outside of formal power structures, and intersecting with social, economic, and technological changes. Here, we develop literature highlighting the ambiguities of co-existing toponymic systems and their use in the everyday, sometimes (but not always) linked to resistance.

A limited literature has explored dual or multiple co-existing toponymic landscapes (e.g., Bigon & Njoh, Citation2018; Light & Young, Citation2014, Citation2018; Yeoh, Citation1992, Citation1996, Citation2018). Yeoh (Citation2018) demonstrates how in colonial Singapore official street names and a range of non-European immigrants’ names worked side-by-side in everyday life. As Bigon and Njoh (Citation2018, p. 212) note ‘place names create and maintain emotional attachment to places’, and hence older, removed place names can persist in everyday usage (Light & Young, Citation2014). This ‘toponymic ambiguity’ (Bigon & Njoh, Citation2018) includes the existence of dual street names but also the co-existence of different names in bilingual societies (and even differences in pronunciation as a performative act (Kearns & Berg, Citation2002)), resulting in the co-existence in everyday life of official and unofficial or vernacular (but more popular) street names.

These studies illustrate the potential limits to state-sanctioned (re-)naming and power – political change and associated renaming are not comprehensive or final (Light & Young, Citation2014, Citation2018). Yeoh (Citation1992, Citation1996, Citation2018) demonstrates how the imposition of official European-style street naming practices in colonial Singapore was limited by immigrant Asian communities use of alternative systems of street names – the ‘persistence of different systems of signification in the city showed that municipal representations of the landscape did not command an unchallenged hegemony.’ (Yeoh, Citation2018, p. 50). As Rose-Redwood et al. (Citation2018b, p. 5) note this signals the importance of moving beyond ‘official practices of naming to the importance of competing ontologies of place that were enacted through informal everyday speech acts’ (and see, Creţan & Matthews, Citation2016; Shoval, Citation2013).

This research thus points to a more nuanced understanding of power and naming. As Yeoh (Citation2018, p. 51) usefully points out, ‘power in the naming process is not the same as power in everyday life.’ Rose-Redwood et al. (Citation2018b, p. 16) argue that ‘how official and unofficial street names are used by urban residents in their everyday lives’ can be down to habit rather than resistance to top-down political naming projects (and see, Light & Young, Citation2014; Vuolteenaho & Puzey, Citation2018). As Rose-Redwood (Citation2008a) has demonstrated there are performative limits to the official city-text, where the official act of street renaming is not guaranteed by decree of the state alone but depends upon its performative uptake in everyday life.

More emphasis should therefore be placed on the performative dimensions of place names. Duminy (Citation2014, p. 325) points to

the value of conceiving of naming as a performative practice, in which symbolic power and capital are seen as reproducible yet unstable, as emergent from the relations cast between creative acts of iteration and destabilization, rather than as a property deduced from a presupposed hegemony.

This focus on performativity in turn invites consideration of a greater range of actors and processes through which power and meaning inter-relate with place-naming, as argued by Rose-Redwood et al. (Citation2018b, p. 16):

our critical analyses of street naming must … extend beyond the sovereign declarations of officialdom … naming is not a singular act of political will but rather depends on a series of reiterative citational practices enacted by a diverse array of social and political actors …

Here, power is differentiated in terms of who possesses how much of it and is not simply a unidirectional, top-down imposition of renaming and meaning. This means that critical toponymies must also ‘take into account the diversity, specificity, and relationality of all performance and counter-performances resisting and reconstituting the “perlocutionary field” of the naming process (Rose-Redwood, Citation2008b)’ (Duminy, Citation2014, p. 321), including the emotional and affective geographies of urban toponymy and the reception of place names in everyday life. These elements might be more obvious in cases where official renaming meets intense local diversity, such as in the SCSI context. Here we also follow recent literature which has adopted assemblage theory to analyse place naming as a ‘radically open and dynamic process mobilized relationally through a multiplicity of discourses and materialities’, a process which can also lead to different ‘alliances and counter-framings’ (Wideman & Masuda, Citation2018, p. 383).

Finally, these recent moves in the literature also suggest a need to diversify the kinds of context studied. Critical toponymies has tended to focus on street names, typically in larger (and capital) more often Western cities, in contexts of rapid and revolutionary political change (e.g., Azaryahu, Citation1996; Azaryahub, Citation2012; Creţan & Matthews, Citation2016; Marin, Citation2012; Palonen, Citation2008). There are works on island naming, but these tend to follow a more traditional focus on the origins and meanings of island toponyms (Garau & Sebastián, Citation2013, Citation2017; Nash, Citation2012, Citation2016) though more critical analyses exist (e.g., Nash, Citation2017; Radil, Citation2017). In this paper, therefore, we analyse a different context to advance the critical toponymies literature.

Methods and data

The analysis involved interviews and participant observation in Haikou, Qionghai, and Wenchang in Hainan Province, combined with archival research. Purposive and snowball sampling were used to select participants. 113 participants were involved – 93 fishermen/residents (in balanced age groups from 30-89 – due to the highly gendered nature of professional fishing only one fisherwoman was interviewed), 1 newspaper editor, and 19 government or public service (e.g., museum) staff, supplemented by interviews or discussions with several experts who know Genglubu. The names of interviewees in this paper are pseudonyms for confidentiality. Most interviews were conducted in Mandarin Chinese, but a few with local fishermen in the Hainan dialect involved local people as translators.

Among fishermen/residents, in-depth interviews (lasting 1–1.5hrs) with 32 of them took place in their homes, workplaces, the seaside, or teahouses. After an exploration of their recognition of vernacular and official toponyms of SCSI, the interviews proceeded with several open questions about the multiple dimensions of the toponyms. Interviewees were informed that they could answer each open question based on their personal experience and thoughts, and were encouraged to raise new topics. Interviews with other professional groups provided diverse insights into the vernacular and official toponyms of the SCSI, fishermen’s use and recognition of toponyms, and the general context of the culture of Hainan fishermen.

Naming and renaming the South China Sea Islands: vernacular and official toponyms

The co-existence of vernacular and official naming systems in the SCSI context has evolved over a long time period, and here we trace the evolution and interaction of the different naming processes.

Genglubu

Vernacular names function mainly in oral use, but many of them have also been recorded in Genglubu, guides created by Hainan fishermen recording navigation routes and other (e.g., meteorological) information which have been passed down through generations (Liu, Citation1994). Most scholars maintain that Genglubu originated in the early Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) (Li & Feng, Citation2015; Zeng & Zeng, Citation1996; Zhou, Citation2015). With increasing tension in the SCS, Genglubu were co-opted by the Chinese state from the later twentieth century as part of the historical evidence used to support its claims of sovereignty over the SCS, based on the argument that they constituted a folk record of Chinese fishermen engaging with the islands of the SCS for many centuries. As part of this process the Chinese state engaged policymakers, academics, and the media in the exhumation and exploration of Genglubu (e.g., CGTN, Citation2017).

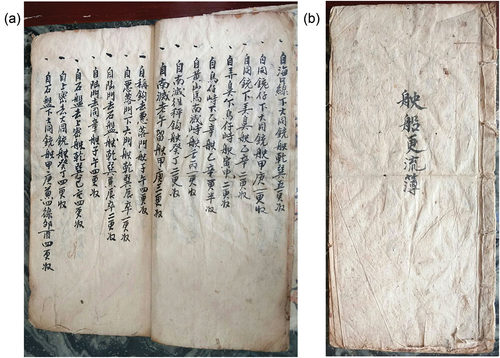

There was no unified title for these guides until the 1970s, when scholars named them Genglubu since most recorded navigation routes contain the characters for ‘geng’ and ‘lu’ (Liu and Zhang, Citation2017). Although there is some variety among the 20 different versions of Genglubu collected thus far, for the most part the recorded islands and reefs, sea areas, and fishing routes are similar. The key content comprises routes – composed of a starting point, end point, sailing distance and course – covering the Xisha Islands (Paracel Islands), Nansha Islands (Spratly Islands), and other sea areas. One example (see ) helps to illustrate this – ‘自海口线下大同铳驶乾巽五更收’ means ‘from Barque Canada Reef to East Reef, heading 315°, sailing for 10 hours or 50 nautical miles’. ‘海口线(hai kou xian)’ refers to ‘Barque Canada Reef’, ‘大同铳(da tong chong)’ refers to ‘East Reef’, ‘更(geng)’ means ‘the time or distance of a voyage’ (one ‘geng’ equates approximately to 2 hours or 10 nautical miles). The toponyms of the SCSI were recorded in Genglubu in their vernacular form following the names given by Hainan fishermen according to the shape, location, color, landform, biology, and legends of the islands and reefs. The vernacular toponyms in this study were collected from 18 versions of Genglubu.

The vernacular toponyms of the South China Sea Islands

The vernacular toponymy of Hainan fishermen recorded in the Genglubu is thus a set of oral toponyms in the local dialect. In the Genglubu, islands often have many toponyms. This can be attributed to the oral and spontaneous nature of vernacular toponyms without a formal written text form – they were written down following their pronunciation in the local dialect. Thus, there are differences in the recording of vernacular toponyms in different versions of Genglubu, but the pronunciations between them are similar. 18 versions of Genglubu record 109 vernacular toponyms in the Xisha Islands and Nansha Islands (34 and 75 respectively). Of these, 47 carry general terms. Thus the vernacular toponymy shares a set of general terms, such as 圈 ‘quan’ (atolls), 峙’zhi’ (island), 峙仔’zhizai’/沙仔’shazai’/线仔’xianzai’ (sandbars), 门’men’ (waterway), 沙’sha’/线’xian’ (reef), 沙排’shapai’/线排’xianpai’ (underwater sandy beach), and 郎’lang’ (deeper reef under the sea).

This vernacular toponymy, centered as it is on the natural features of the SCSI and fishermen’s experience and anecdotes, played a key role in the everyday practices of fishing on the SCS. For example, as Min (an expert) stated in an interview:

An old fisherman told me that there was a large submerged reef on the South China Sea. Foreign fishing boats didn’t have guts to go in at night because they were afraid of hitting the reef. However, Hainan fishermen didn’t worry about it and know how to deal with it. They called it ‘鱼鳞(fish scale)’. The name itself showed that Hainan fishermen mastered the geographical conditions there.

Thus the vernacular naming of the feature reflected and transmitted local everyday experience of fishing in the area, with ‘fish scale’ indicating that local fishermen held no fear of the feature.

The official toponymies of the South China Sea Islands

Various official naming systems have also been applied to this area and interacted with the vernacular toponymy. In the second half of the 19th century, official naming was mainly undertaken by powerful nations seeking to exploit the area – principally Britain and America – and therefore official names were recorded in English on their sea charts. In the 20th century, due to the strategic importance of the area and the growth in China’s attempts to gain control of the sea, Chinese governments began to name the SCSI formally. The first official designation occurred in 1907, when a Qing Dynasty (the last imperial dynasty of China, 1644–1912) official Li Zhun named 16 reefs during his tour of the Xisha (Paracel) Islands, but only ‘Ganquan Island’, ‘Shanhu Island’, ‘Chenhuang Island’, and ‘Guangjin Island’ are still in use today because of the loss of the original document (the ‘Li Zhun Cruise Chart’). In 1935, the ‘Contrast Table of Chinese and British Names of Islands and Reefs in the South China Sea’, issued by the National Land and Sea Map Review Committee of Government of the Republic of China, published 139 toponyms. However, rather than imposing new names, almost all of these names were transliterated or freely translated from the English toponyms, without any attempt to claim indigenous Chinese cultural characteristics in the region. In 1947, 172 toponyms of the SCSI were issued in the document ‘Comparison of old and new names of South China Sea Islands’, which was published by the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of China.

The most recent official renaming took place in 1983, when 287 toponyms were published in The People’s Daily (the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party), including 192 toponyms in the Nansha Islands and 51 in the Xisha Islands. In contrast to previous rounds of renaming, this set of toponyms were defined by numerous meetings and discussions based on an investigation conducted by experts from the Committee on Geographical Names of the People’s Republic of China. 20% of the new toponyms followed vernacular ones. However, 34% of these toponyms were transliterated or freely translated from English ones, of which 13% had corresponding vernacular toponyms. In 2020, the Ministry of Natural Resources and the Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China issued a further 80 toponyms, including 25 islands and reefs of which 17 were notably named with vernacular toponyms. These larger-scale toponymic revisions formed part of efforts to establish a narrative of a long-term Chinese presence in the area.

Complex toponymies in the everyday life of Hainan fishermen

Our research showed that fishermen of different age groups have remarkable variations in the use, recognition, and degree of confusion with regard to the two sets of toponymies in everyday life and practice.

The number of respondents who clearly indicated a preference for using official or vernacular toponyms was similar (42 and 45 respectively), indicating that both vernacular and official toponyms were significant in the fishermen’s everyday lives. About a quarter of the respondents (24) could recognize and match two sets of toponyms for some of the islands and reefs in the SCS, but only 8 (all fishermen aged 60 and over) almost fully understand both sets of toponyms. 30 respondents were unfamiliar with official toponyms and 22 respondents of their vernacular counterparts, indicating that for the majority of fishermen the official and vernacular toponyms varied in their knowledge and use.

Generational differences in the use and recognition of toponyms were highly significant. Fishermen aged 60 and over could match more toponyms between the two sets, and exhibited a higher degree of recognition of, and preference towards, vernacular toponyms. Their younger counterparts had an overall lower awareness of the vernacular toponyms of the SCSI and tended to use official toponyms.

The fishermen were also asked about their attitude towards the two sets of toponyms. Only 26% of fishermen had a strong emotional preference (11% in favour of vernacular toponyms and 15% for official ones). The remaining 74% expressed no obvious emotional tendency towards either of the two sets of toponyms. Among them, the majority of respondents (29%) typically said ‘I am not sure, but [I am] used to saying our [vernacular] names’. Around a quarter of fishermen (23%) were indifferent. 15% were comfortable with both sets of toponymies. A very small proportion believed that the official toponyms were named after vernacular toponyms – ‘many official toponyms are the same as ours [vernacular toponyms]’ – and thus did not really distinguish between them.

Overall, Hainan fishermen thus have no obvious strongly held attitude towards the renaming of toponyms. The vernacular toponyms are not discarded, but this is not accompanied by resistance towards the new toponyms. This vernacular toponymy is deeply embedded in the everyday lives of Hainan fishermen and is more related to personal habit and convenience (and see, Light & Young, Citation2014). While not rejecting the official toponyms, at the same time the vernacular ones are not easily abandoned, thus creating the phenomenon of the co-existence of dual toponymies in everyday life.

Dual toponymies of the SCSI in the everyday lives of Hainan fishermen

The ways that these dual toponymies persist, interact, and are infused in everyday life plays out in complex ways which are further influenced by a range of factors which are not often considered in the critical toponymies literature. This is explored in the following sections.

Everyday work routines

I know the names of the islands and reefs I often visit, but I don’t know the ones I haven’t been to (Huang, fisherman, 66).

The utilitarian function of toponyms is facilitating spatial orientation (Rose-Redwood et al., Citation2010). Indeed, people encounter toponyms through utilizing them practically in everyday life. The toponyms of the SCSI are intimately related to Hainan fishermen’s working activities on the sea. Therefore, their recognition of the toponyms of the SCSI varies according to their own living and work practices. Fishermen thus exhibited different degrees of recognition of different islands and reefs, which overwhelmingly related to their maritime experience – they were ‘very familiar with the characteristics of islands and reefs with frequent fishing time’ (Qiang, fisherman, 61).

At times, fishermen mixed official toponyms with intimate knowledge of the characteristics of the islands, for example, ‘East Island is very small, but this island has the largest number of birds’ (Wu, fishing Captain, 54) or ‘I can go right with my eyes closed in the Xisha Islands, and we know how many products each island has’ (Qiang, fisherman, 61). Sometimes vernacular names were linked with practical and safety aspects of being at sea, as in ‘The best shelter in Xisha Islands is Sanjiao [the vernacular form of Chenhang (Duncan) Island]’ (Sugong, fishing Captain, 84). At the same time, fishermen lacked knowledge of the official toponyms if they did not form part of their regular fishing activities:

I don’t remember the official placenames of Yinyu [the vernacular form of Observation Bank] and Laocu [the vernacular form of Pattle Island]. I rarely went to these two islands, and now I don’t remember where they are … They are very small pieces … but I will know when I go there’ (Zheng, fishing Captain, 54).

In these cases, the use of the official or vernacular toponymies (or both simultaneously) was related to the mundane working practices of fishermen, and not the imposition of, or resistance to, power.

Technological change

Studies of the use of toponyms and responses to renaming have neglected the mundane role of technological change in favour of a focus on the political. Before the 1970s, Genglubu acted as a key navigation tool for Hainan fishermen, and the recording of vernacular toponyms in them was related to their use in the everyday working environment. However, technology has come to play an increasingly role in navigation as fishermen in Qionghai and Wenchang discussed. In the later 20th century nautical charts became more commonplace, followed by Loran C navigation systems, and in the 21th century GPS satellite navigation systems drove changes in the use of toponymies. These advanced digital navigational instruments work with official toponyms and this has driven the use of official toponyms into the everyday life of Hainan fishermen. Indeed, the recognition and use of official toponyms has become a necessity, reducing the value of vernacular toponyms. However, the dual toponymy still persists, but there is more a division between the work environment and the rest of everyday life, i.e. ‘the vernacular toponymy is used for daily oral communication, while the official toponymy is used for working on the sea’ (Chuang, fishing Captain, 63). Though at times some fishermen struggled to reconcile matching the two sets of toponyms for a specific island or reef, they continue to co-exist in everyday life.

Generational differences and demographic changes

Studies of the reception and use of renaming have so far not considered the influence of demographic and generational factors. The most recent official toponymy of the SCSI was published in 1983, and satellite navigation systems reproducing official toponyms did not become popular among fishermen until the 1990s. Thus, many older fishermen did not have much contact with official toponyms before they retired because of the relatively short history of the official toponyms, and these fishermen had used the vernacular toponyms for far longer. Therefore, the vernacular toponyms are firmly rooted in older fishermen’s minds. More elderly fishermen (70+) expressed no knowledge of the official toponymy. Middle-aged fishermen (40–70), who experienced the politically and technologically supported transition of toponyms, could recognize more toponyms in both the vernacular and official sets. Fishermen under 40 had lower awareness of vernacular toponyms of SCSI and understood more official ones. As Zhong (fisherman, 62) lamented, ‘the older all speak dialect [vernacular toponyms], our generation speak both, I guess the next generation will not know vernacular toponyms.’

However, among these generational differences there also exist complex inter-generational uses of the two toponymic systems. Talking with the old fishermen is one of the main sources through which younger fishermen and non-fishermen obtain knowledge of the SCSI. However, one young fisherman (Lin, 43) noted that, despite being more cognizant with the official toponyms, ‘we normally say our own [vernacular] place names. If we say official ones, those old fishermen can’t understand it.’ To share valuable fishing knowledge requires the use of a particular shared toponymic system across the generations. Nevertheless, as young people increasingly turn away from fishing to engage in other land-based occupations, their sea-going experience declines and their awareness of the vernacular toponyms without formal text records becomes less clear:

The young people today don’t know the folk place names, such as Dakuang [the vernacular form of Discovery Reef] and Erkuang [the vernacular form of Vuladdore Reef], because they have never been to them (Dan, fisherwoman, 44).

Furthermore, our interviewees reported that many fishermen are not accustomed to discussing their experiences of fishing within their families, further reducing the exposure of younger people without fishing experience to the vernacular. Many younger interviewees suggested they could not understand vernacular toponyms, and had no intention of learning them, leading to a generational gap which older fishermen could exploit for humour:

There’s a generation gap between my generation and the older one. They often talk and joke with each other using what they would say on the sea. For example, an old fisherman asked “do you want to ‘qingcang’?” In fact, ‘qingcang’ means to go to pee, but other people don’t know what they are talking about (Resident, 30+).

Everyday language

Language is the basis for people to utilize and communicate toponyms, and the oral communication of toponyms is often determined by language (Herman, Citation1999). Some kinds of toponyms only have meaning within the context of a particular language or pronunciation (Kearns & Berg, Citation2002; Light & Young, Citation2014). The vernacular toponymy of the SCSI is presented through the local dialect, as fishermen tend to speak the local dialect in their everyday life, while Mandarin is rarely used and even many old fishermen cannot understand Mandarin. Generally, official toponyms pronounced in Mandarin are unfamiliar and even unpronounceable for those who are used to speaking the local dialect. Accordingly, everyday language practice restricts some people’s use of official toponyms, resulting in their low level of cognition of official toponyms – as one respondent said ‘we generally speak the vernacular toponyms with our dialect’ (Yi, fisherman, 75).

However, with the development of mass media and education, and increasing interaction with outsiders, Mandarin has been popularized among fishermen. In this context, although the local dialect remains the most important language, Mandarin is increasingly embedded in fishermen’s everyday life, enhancing their awareness of official toponyms. This embedding of Mandarin in everyday contexts like official education, media, and GPS systems is encouraged by central government and this does represent the exertion of state power. However, the interaction of language with the use of toponyms is complex. As our research showed, fishermen with a higher level of Mandarin possess a higher recognition of official toponyms, and vice versa. Thus the co-existence of fishermen who tend to speak Mandarin with those who are relatively unfamiliar with it contributes to the differentiation and confusion in fishermen’s recognition of the co-existing toponyms of the SCSI. The co-existence of state-led and persisting vernacular toponyms is thus not simply about resistance to official renaming. It is also produced by complex processes of competition and compromise between the government and Hainan fishermen in the use of Mandarin versus the local dialect.

Habit

More recent literature has suggested a move away from a focus on resistance to consider the role of habitual practice in the use of toponyms (Light & Young, Citation2014). Non-representational theory (Thrift, Citation2008) examined habit in the context of the recent increase in interest in affect. Habit is unreflexive, precognitive, and usually unconscious, and can be one of the ways to realize affect, thus, it has a clear affective dimension (Duff, Citation2010). Genglubu can be traced back to the early Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), while the official toponymy has been used partially by fishermen for less than four decades. The vernacular toponymy thus has a deep foundation among Hainan fishermen. Therefore, for many fishermen, particularly the elderly, there are no other intentional purposes behind continuing to use vernacular toponyms – such as resistance to renaming or political identity construction – it is down to habit and inertia (and see, Light & Young, Citation2014). As one older respondent said: ‘I don’t know the origin of vernacular toponyms. We (fishermen) are just used to it’ (Lu, fishing Captain, male, 66). Custom and habit are more important in this context – ‘We have been talking about our place names for so many years, old people do not understand new placenames, and we are accustomed to using folk place names. In addition, we cannot remember all official place names’ (Bao, fisherman, 69).

Fishermen’s status and role

Generally, the captains understand both official and vernacular names of each island (Bao, fisherman, 69).

The particular role that fishermen perform in fishing boats also impacts on their recognition and use of toponyms. Up until 1949, Hainan fishermen engaged in the practice of ‘Federal sailing’, pooling together finance from joint investments with relatives or neighbours, and sailing together to ensure safety. The captain was selected by the crew according to their experience and capability, and was responsible for arranging fishing routes, guaranteeing navigation and safety, and decision-making. During the 1950–90s, these organizational forms underwent changes, but the selection of captains was always based on their experience and knowledge. Even though technological progress in navigational equipment since the 1990s has reduced the requirements for a captain’s ability, their awareness and familiarity with navigation routes, islands, and reefs is still higher than that of ordinary fishermen. Indeed, captains in this study showed higher levels in identifying and matching the vernacular and official toponyms.

By comparison, as ordinary fishermen usually follow their captain’s instructions understanding the two sets of toponyms is unnecessary for them, but the captain can typically master and match the vernacular toponyms with official toponyms on satellite navigation systems or charts. However, with the development of navigation equipment the requirement for the captain’s superior knowledge and experience at sea has also been reduced. Therefore, the ability of younger captains to recognize and identify to the two sets of toponymies is relatively weak, or they are more familiar with the official toponyms.

Emotional attachment

Toponyms are not merely a tool for orientation, but also serve as ‘memorial arenas’ which serve to sustain memory, cultural traditions, and reflect a certain political identity (Alderman, Citation2002, Citation2003; Azaryahu, Citation1986; Hui, Citation2019; Wanjiru & Matsubara, Citation2017). Here, vernacular toponyms are the product of Hainan fishermen’s ancestors’ naming according to their own maritime experience and the geographical and biological characteristics of the islands and reefs they found, continually supplemented and modified by their descendants. Vernacular toponyms carry rich cultural deposits and embody the achievements of Hainan fishermen. More importantly, these toponyms are significant arenas in which to maintain memory and symbolize the identity of Hainan fishermen – ‘These (folk) place names are the achievement of our ancestors’ continuous sailing experience and the basis of our modern voyage’ (Wang, fishing Captain, 53). In some cases, fishermen remembered the folk-tales associated with the vernacular names and could recount them:

[In dialect] Nailuo means ‘enduring’. It was said that a fisherman took his kid to the sea to catch fish, and the boy felt lonely on South Reef. This fisherman told his son to endure it. So ancestors called that island Nailuo shazai (Qiang, fisherman, 61).

Here the use of vernacular toponyms was related to history, memory, place, and local pride in the vernacular names – ‘Vernacular toponyms were created by our ancestors in our dialect. We cannot know only Taiping Island and not Huangshanma [the vernacular form]. We should pass them on’ (Lu, fishing Captain, male, 66) and ‘The vernacular toponyms were named by our ancestors according to their own sea-going experience and should be handed down’ (Zheng, fishing Captain, 54).

However, again generational factors complicate this picture and mean it will change over time, as for many fishermen there is no significant difference between the vernacular and official toponyms in relation to their function and nature, and the official toponyms have even brought more convenience. Thus, the loss of cultural memory about vernacular toponyms among fishermen may become an ongoing process:

If you stay a few years later, you would not be able to study the folk toponymy. Because old captains might all died by then, and no one would know about these. Younger captains don’t understand those place names in Genglubu (Huang, government worker [Tanmen], male, 49).

The alignment of political power and the everyday lives of Hainan fishermen

The critical toponymies literature has rightly focused on how bottom-up resistance to the official renaming is often ignited or mobilized by political, cultural, and economic conflicts between elites and less powerful groups, including racial or ethnic struggles (e.g., Alderman, Citation2003; Hui, Citation2019; Yeoh, Citation1992), discrepancies in political ideology (e.g., De Soto, Citation1996), claims for social justice (e.g., Alderman, Citation2008; Alderman & Inwood, Citation2013; Wideman & Masuda, Citation2018), or more mundane matters such as the economic costs for residents (e.g., Creţan & Matthews, Citation2016). However, since there is less of a fundamental chasm or dissonance between Chinese state authority and Hainan fishermen in terms of political ideology, national identity, and ethnicity, here we argue that power and renaming can operate in more complex ways.

On the one hand state power is certainly still at play. Tensions around claims to the SCS became more intense in the 1970s and 1980s (e.g., the military conflict between China and Vietnam in the Xisha (Paracel) Islands in 1974) in the contexts of the detection and exploitation of vast reserves of oil and natural gas in 1970s and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) establishing a right to claim an exclusive economic zone within two hundred nautical miles of a state’s shores in 1982. The official renaming of sea features by China in 1983 can be understood as one response to competing claims of sovereignty by Asian countries in the SCS. This has continued into the 21th century with recurring tension and conflict, notably the Scarborough Shoal Dispute in 2012, and the China-Philippines South China Sea Arbitration in 2016. These political disputes have implications for the survival of Hainan fishermen, as they shape the accessibility and security of their fishing activities. As one fisherman recounted:

when we were fishing near some islands in Nansha Islands in the 1980s, soldiers from other countries fired at our boats to keep us away … the bow and stern of our boat were full of bullet holes (Laofu, fisherman, 52)

Therefore, the official renaming was a part of political claims of sovereignty by the Chinese state over the SCS, but this also helped Hainan fishermen. This alignment of interests helped to shape a context in which the fishermen saw less need for resistance.

The toponymic cleansing of colonial influences in the official renaming was a part of China’s attempts to lay claim to territory, but this relied in part on associating ‘indigenous’ Chinese cultural characteristics with the SCS through largely following vernacular toponyms used by Hainan fishermen. This action helped to officially formalise and popularise part of the vernacular toponymic system which mainly exists in oral form without formal written records and material inscriptions (e.g., street signs). The partial incorporation of vernacular toponyms into state-led renaming created a context in which resistance to official naming was less appropriate.

Furthermore, as is analysed above, the fact that the official toponyms co-exist with, rather than fully replace, vernacular toponyms in the everyday life of the fishermen also relates to their wish to retain them, linked to their spoken language, entrenched habit, and emotional attachment. Thus, the way that power operates in (re-)naming can be much more diffuse and related to a complex mix of interests than a simple power/resistance dichotomy.

Conclusion

The analysis of Hainan fishermen’s use of, and response to, co-existing official and vernacular toponymies of SCSI in everyday life develops different perspectives in critical toponymic research. In this context vernacular and official toponymies co-exist and interact in complex ways which go beyond understandings focused on power expressed through resistance to the top-down imposition of naming as a political act (and see, Rose-Redwood et al., Citation2018b).

The four rounds of official renaming by the Chinese state since the 20th century were a part of nation-building and territorial claims, through seeking to infuse indigenous discourses with new naming systems and the displacement of foreign language names and symbolism. The incorporation of vernacular toponyms used by Hainan fishermen into official systems was politically driven and related to territorial claims by the state, demonstrating that the vernacular toponymy was partly co-opted by the authorities for political purposes. However, this process was not all-powerful or all-inclusive (and cf., Light & Young, Citation2018). Official and vernacular toponymies are interpenetrative and coexisting in everyday life. While in other contexts official adoption of vernacular toponyms was the result of government compromise in the face of resistance (e.g., Berg & Kearns, Citation1996; Hodges, Citation2007), here residents’ responses to the new toponyms and renaming by the state were not simply characterized by negation or resistance. Some people inter-mix them in everyday life and practice while others are simply unaware of official toponyms and use vernacular ones instead (cf., Creţan & Matthews, Citation2016; Light & Young, Citation2014). While it is vital that the critical toponymies literature continues to bring to light the role of power in (re-)naming, this paper argues for the bringing together of a broader range of contexts, cases, processes, and explanatory frameworks to explore beyond hegemony/resistance in renaming.

Shifting the focus from understanding naming in relation to power through the top-down/resistance nexus means considering a wide range of inter-connected factors that rarely get included in such analyses. Hainan fishermen’s everyday responses to the toponyms of the SCSI and the phenomenon of dual toponymies were related to multiple factors. Demographic factors played a role in the differences and various degrees of confusion in the use and recognition of toponyms of the SCSI among fishermen. Fishermen aged 60 and over could match more toponyms between the two sets of toponyms, and demonstrated a higher degree of recognition of and preference towards vernacular toponyms, while their younger counterparts, who were relatively unfamiliar with vernacular toponyms, had an overall lower awareness of the toponyms of the SCSI. However, the majority of fishermen – even those who more habitually use vernacular toponyms – did not express negative feelings towards the official toponyms, in contrast to most studies which focus on residents’ resistance to renaming by elites (e.g., Shoval, Citation2013; Duminy, Citation2014; Creţan & Matthews, Citation2016; Madden, Citation2018).

Other factors which the analysis revealed as important and in need of further study included technological change, habit, nuances in language, emotional attachments, and the everyday work contexts in which names are used. Working practices at sea and technological progress in navigation were significant, because the utilitarian function of toponyms is often manifested in practical experience, which impact the fishermen’s use and recognition of toponyms. Another significant factor influencing everyday responses to renaming is habit (Light & Young, Citation2014). Linguistic and psychological inertia was a key reason why many fishermen tend to use vernacular toponyms, and also intensified generational differences in the use and recognition of different toponyms. The role and status of fishermen and emotional attachment to toponyms also strengthened these processes. This is not to argue that political power is entirely absent in such processes, but that it can operate in different ways. As analysed above, official renaming aimed at strengthening China’s political claims of sovereignty over the SCS but this also aligned with the needs of Hainan fishermen to continue to fish in these waters, in part reducing any incentive for them to resist such changes, providing an example of how considering toponymies as assemblages can reveal perhaps unexpected alliances, not only resistance (see, Wideman & Masuda, Citation2018).

Overall, public responses to processes of renaming are continuously transforming and are not solely about resistance to top-down naming processes. The analysis here develops Rose-Redwood et al.’s (Citation2018b, p. 16) argument that ‘critical analyses of street naming must … extend beyond the sovereign declarations of officialdom’ to consider how naming ‘depends on a series of reiterative citational practices enacted by a diverse array of social and political actors [and their] repetitious use in daily life.’ Analyses thus need to explore the complex interaction of official and non-official (vernacular) place naming systems, which will require consideration of a broader range of contexts, factors, and processes that shape the use of place names in everyday life.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alderman, D. (2000). A street fit for a King: Naming places and commemoration in the American South. The Professional Geographer, 52(4), 672–684 doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-0124.00256.

- Alderman, D. (2002). Street names as memorial arenas: The reputational politics of commemorating Martin Luther King in a Georgia county. Historical Geography, 30(1), 99–120 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238703150_Street_Names_as_Memorial_Arenas_The_Reputational_Politics_of_Commemorating_Martin_Luther_King_Jr_in_a_Georgia_County.

- Alderman, D. (2003). Street names and the scaling of memory: The politics of commemorating Martin Luther King, Jr. within the African American community. Area, 35(2), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4762.00250

- Alderman, D. (2008). Place, naming, and the interpretation of cultural landscapes. In B. Graham & P. Howard (Eds.), The Ashgate research companion to heritage and identity (pp. 195–213). Ashgate.

- Alderman, D., & Inwood, J. (2013). Street naming and the politics of belonging: Spatial injustices in the toponymic commemoration of Martin Luther King Jr. Social & Cultural Geography, 14(2), 211–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2012.754488

- Alderman, D., & Reuben, -R.-R. (2020). The classroom as “toponymic workspace”: Towards a critical pedagogy of campus place renaming. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 44(1), 124–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2019.1695108

- Azaryahu, M. (1986). Street names and political identity: The case of East Berlin. Journal of Contemporary History, 21(4), 581–604. https://doi.org/10.1177/002200948602100405

- Azaryahu, M. (1996). The power of commemorative street names. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 14(3), 311–330. https://doi.org/10.1068/d140311

- Azaryahub, M. (2012). Renaming the past in post-Nazi Germany: Insights into the politics of street naming in Mannheim and Potsdam. Cultural Geographies, 19(3), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474011427267

- Berg, L. D., & Kearns, R. A. (1996). Naming as norming: ‘race’, gender, and the identity politics of naming places in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 14(1), 99–122. https://doi.org/10.1068/d140099

- Bigon, L., & Njoh, A. J. (2018). Toponymic complexities in Sub-Saharan African cities: Informative and symbolic aspects from past to present. In R. Rose-Redwood, D. Alderman, & M. Azaryahu (Eds.), The political life of urban streetscapes (pp. 202–217). Routledge.

- CGTN. (2017). ‘What is China?’ Book provides evidence of China’s claims in South China Sea’. https://news.cgtn.com/news/7763444d34457a6333566d54/index.html

- Creţan, R., & Matthews, P. W. (2016). Popular responses to city-text changes: Street naming and the politics of practicality in a post-socialist martyr city. Area, 48(1), 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12241

- De Soto, H. G. (1996). (Re) inventing Berlin: Dialectics of power, symbols and pasts, 1990–1995. City & Society, 8(1), 29–49. https://doi.org/10.1525/ciso.1996.8.1.29

- Duff, C. (2010). On the role of affect and practice in the production of place. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28(5), 881–895. https://doi.org/10.1068/d16209

- Duminy, J. (2014). Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 32(2), 310–328 https://doi.org/10.1068/d2112.

- Garau, A. O., & Sebastián, J. B. (2013). Minorca island landscape characterization through toponymy. Investigaciones Geográficas, 60, 155–169. https://doi.org/10.14198/INGEO2013.60.09.

- Garau, A. O., & Sebastián, J. B. (2017). Toponymy and nissology: An approach to defining the Balearic Islands’ geographical and cultural character. Island Studies Journal, 12(1), 243–254. https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.15

- Herman, R. K. (1999). The Aloha State: Place names and the anti-conquest of Hawai ‘i. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 89(1), 76–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/0004-5608.00131

- Hodges, F. (2007). Language planning and placenaming in Australia. Current Issues in Language Planning, 8(3), 383–403. https://doi.org/10.2167/cilp120.0

- Hui, D. L. H. (2019). Geopolitics of toponymic inscription in Taiwan: Toponymic hegemony, politicking and resistance. Geopolitics, 24(4), 916–943. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2017.1413644

- Ji, X., Wang, W., Chen, J., Tao, Z., & Fu, Y. (2016). Review and prospect of toponymy research since the 1980s. Progress in Geography, 35(7), 910–919. https://doi.org/10.18306/dlkxjz,2016,07.012.

- Ji, X. (2018). City-renaming and its effects in China. GeoJournal, 83(2), 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-017-9772-0

- Kearns, R. A., & Berg, L. D. (2002). Proclaiming place: Towards a geography of place name pronunciation. Social & Cultural Geography, 3(3), 283–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464936022000003532

- Li, P., & Feng, D. (2015). The politics of place naming: Changing place name and reproduction of meaning for Conghua Hotspring. Human Geography, 30(2), 58–64. https://doi.org/10.13959/j.issn.1003-2398.2015.02.009.

- Light, D., Nicolae, I., & Suditu, B. (2002). Toponymy and the communist city: Street names in Bucharest, 1948–1965. GeoJournal, 56(2), 135–144. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022469601470

- Light, D., & Young, C. (2014). Habit, memory, and the persistence of socialist-era street names in postsocialist Bucharest, Romania. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 104(3), 668–685. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2014.892377

- Light, D., & Young, C. (2018). The politics of toponymic continuity: The limits of change and the ongoing lives of street names. In R. Rose-Redwood, D. Alderman, & M. Azaryahu (Eds.), The political life of urban streetscapes (pp. 185–201). Routledge.

- Liu, N. W. (1994). The nomenclature of the Nanhai Islands in Ancient China. Scientia Geographica Sinica, 14(2), 101–108 https://doi.org/10.13249/j.cnki.sgs.1994.02.101.

- Liu, N. W., & Zhang, Z. S. (2017). Interpretations of Hainan Fishers’ Genglubus. The Journal of South China Sea Studies, 3(1), 22–26. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2017&filename=NHXK201701005&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=zShcVUNoY_bAJPCBlxp9VNVm5Jr_3lEVeSjqkAhUnJEh3Wh1KIpv-HNGHP1aa_Yh.

- Liu, X. Y., Zhang, Z. S., & Niu, S. Y. (2017). Analysis on the name evolution and power relation of Huangyan island in the critical perspective. Human Geography, 32(4), 115–120. https://doi.org/10.13959/j.issn.1003-2398.2017.04.016.

- Madden, D. J. (2018). Pushed off the map: Toponymy and the politics of place in New York City. Urban Studies, 55(8), 1599–1614. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017700588

- Marin, A. (2012). Bordering time in the cityscape. Toponymic changes as temporal boundary-making: Street renaming in Leningrad/St. Petersburg. Geopolitics, 17(1), 192–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2011.574652

- Nash, J. (2012). Naming the aquapelago: Reconsidering Norfolk Island fishing ground names. Shima: The International Journal of Research into Island Cultures, 6(2), 15–20. http://www.shimajournal.org/issues/v6n2/d.%20Nash%20Shima%20v6n2%2015-20.pdf.

- Nash, J. (2016). Language contact and ‘the Catch’: Norfolk Island fishing ground names. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift-Norwegian Journal of Geography, 70(1), 62–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2015.1110197

- Nash, J. (2017). Pitcairn Island, Island toponymies and fishing ground names. The Journal of Territorial and Maritime Studies, 4(1), 86–96 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319932838.

- Palonen, E. (2008). The city-text in post-communist Budapest: Street names, memorials, and the politics of commemoration. GeoJournal, 73(3), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-008-9204-2

- Radil, S. M. (2017). The multi-scalar geographies of place naming. The Journal of Territorial and Maritime Studies, 4(1), 72–85. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26664144.

- Rose-Redwood, R. (2008a). From number to name: Symbolic capital, places of memory and the politics of street renaming in New York City. Social & Cultural Geography, 9(4), 431–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360802032702

- Rose-Redwood, R. (2008b). “Sixth Avenue is now a memory”: Regimes of spatial inscription and the performative limits of the official city-text. Political Geography, 27(8), 875–894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2008.11.002

- Rose-Redwood, R., Alderman, D., & Azaryahu, M. (2010). Geographies of toponymic inscription: New directions in critical place-name studies. Progress in Human Geography, 34(4), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132509351042

- Rose-Redwood, R., Alderman, D., & Azaryahu, M. (2018a). Contemporary issues and future horizons of critical urban toponymy. In R. Rose-Redwood, D. Alderman, & M. Azaryahu (Eds.), The political life of urban streetscapes (pp. 309–319). Routledge.

- Rose-Redwood, R., Alderman, D., & Azaryahu, M. (2018b). The urban streetscape as political cosmos. In R. Rose-Redwood, D. Alderman, & M. Azaryahu (Eds.), The political life of urban streetscapes (pp. 1–24). Routledge.

- Shoval, N. (2013). Street-naming, tourism development and cultural conflict: The case of the Old City of Acre/Akko/Akka. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 38(4), 612–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12003

- Thrift, N. (2008). Non-representational theory: Space, politics, affect. Routledge.

- Vuolteenaho, J., & Puzey, G. (2018). Armed with an encyclopedia and an axe”: The socialist and post-socialist street toponymy of East Berlin revisited through Gramsci. In R. Rose-Redwood, D. Alderman, & M. Azaryahu (Eds.), The political life of urban streetscapes (pp. 74–97). Routledge.

- Wanjiru, M. W., & Matsubara, K. (2017). Street toponymy and the decolonisation of the urban landscape in post-colonial Nairobi. Journal of Cultural Geography, 34(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873631.2016.1203518

- Wei, X. (2016). The change of urban place names and the construction of social memory: An analysis based on the annals of Zidi Village. China Ancient City, 3, 53–56. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2016&filename=ZGMI201603010&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=3PXDf0TempWjfqPGdQ4y0X4BpjJuLDDCkG7vGDATm4dQhCARwluOFBpSImEKEKtK.

- Wideman, T. J., & Masuda, J. R. (2018). Toponymic assemblages, resistance, and the politics of planning in Vancouver, Canada. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 36(3), 383–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654417750624.

- Yeoh, B. (1992). Street names in colonial Singapore. Geographical Review, 82(3), 313–322. https://doi.org/10.2307/215354

- Yeoh, B. (1996). Street-naming and nation-building: Toponymic inscriptions of nationhood in Singapore. Area, 28(3), 298–307. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20003708.

- Yeoh, B. (2018). Colonial urban order, cultural politics, and the naming of streets in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Singapore. In R. Rose-Redwood, D. Alderman, & M. Azaryahu (Eds.), The political life of urban streetscapes (pp. 41–55). Routledge.

- Zeng, Z. X., & Zeng, X. S. (1996). The Genglubu study of the Qing Dynasty <Shun Feng De Li> (Wang Guochang’s handwritten copy). China’s Border and History and Geography Studies, 1, 88–107. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD9697&filename=ZGBJ601.009&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=E528DM4Ql_V1JcH0Qq8anmNN26kiejY2lUKeEfQ8LR4OKWgnF15nFQ4d78joWRWV.

- Zhou, W. M. (2015). The formation, prevalence and decline of Genglubu and its nature and use. Humanities & Social Sciences Journal of Hainan University, 33(2), 34–41. https://doi.org/10.15886/j.cnki.hnus.2015.02.005.