ABSTRACT

This article explores how and by what means an emergent health commons is (re)produced in practice. Drawing on recent studies that consider the materiality of citizens’ struggles over the commons, it adopts a more-than-human approach to commoning. Employing ethnographic research on a communal healthcare cooperative in a region of the Netherlands that faces depopulation and institutional failure, I argue that the durability of an emergent health commons is a continuous and contested achievement involving infrastructuring. To articulate the ongoing infrastructural work needed to create and maintain the commons, I employ insights from Maintenance and Repair Studies that explore maintenance as a practice of material care. By exploring the care for infrastructure ethnographically, I specify which aspects of the community healthcare practice, precisely, are maintained in common, and for whom. My analysis reveals that commoning ‘opens up’ new ways of organizing health and existing in common, but may not always sustain radical openness when the social arrangements of the commons transform into steel and bricks. The maintainability of health in common, I suggest, hinges as much on nurturing ‘social’ bonds as on how such bonds are variously infrastructured.

Resumen

Este artículo explora cómo y por qué medios se (re)produce en la práctica un bien común de salud emergente. Basándose en estudios recientes que consideran la materialidad de las luchas de los ciudadanos por los bienes comunes, adopto un enfoque más que humano de la propiedad común. Empleando una investigación etnográfica en una cooperativa de bienes comunes de la salud en una región de los Países Bajos que enfrenta la despoblación y el fracaso institucional, sostengo que la durabilidad de un bien común de salud emergente es un logro continuo y cuestionado que involucra la infraestructura. Para articular el trabajo continuo de infraestructura para crear y mantener los bienes comunes, utilizo los conocimientos de los estudios de mantenimiento y reparación que exploran el mantenimiento como una práctica de cuidado material. Al explorar etnográficamente el cuidado de la infraestructura, especifico qué aspectos de la práctica de la salud comunitaria, precisamente, se mantienen como un bien común y para quién. Mi análisis revela que la comunidad ‘abre’ nuevas formas de organizar la salud y existir como bien común, pero no siempre puede sostener una apertura radical cuando la organización social de los bienes comunes se transforma en acero y ladrillos. La manutención de la salud como bien común, sugiero, depende tanto del fomento de los lazos ‘sociales’ como de cómo dichos lazos se estructuran de diversas formas.

Résumé

Cet article examine la manière et les moyens par lesquels on (re-)produit en pratique les biens communs émergents pour la santé. En s’appuyant sur des études récentes consacrées au caractère essentiel de la lutte des citoyens pour les biens communs, il adopte une approche plus qu’humaine envers la mise en commun. Par le biais d’une recherche ethnographique sur une coopérative de soins de santé communautaire dans une région des Pays-Bas en proie au dépeuplement et à l’échec des institutions, je soutiens que la durabilité des biens communs émergents pour la santé est un développement continu et controversé impliquant l’infrastructuration. Afin d’articuler les travaux d’infrastructure permanents nécessaires à la création et à l’entretien des biens communs, j’utilize des informations provenant de cours d’entretien et de réparations qui portent sur la maintenance en tant que pratique de soins concrets. En explorant de manière ethnographique les soins pour l’infrastructure, je détermine quels aspects des pratiques sanitaires de la communauté, exactement, sont entretenus en commun, et à qui ils sont destinés. Mon analyse révèle que la mise en commun « ouvre » de nouvelles voies pour l’organization sanitaire et l’existence en commun, mais n’est pas toujours capable de maintenir une transparence radicale quand les dispositifs sociaux des biens communs sont convertis en acier et en briques. Je suggère que la maintenabilité de la santé dans les communs dépend autant de l’attention qu’on prête aux liens « sociaux » que de la façon dont ceux-ci sont infrastructurés différemment.

Introduction

‘We take care because we care’ is the slogan Sarah, a member of a rural community in the Netherlands, used to explain her decade-long engagement with Waddenburren’s health and wellbeing. It all started in 2006, she continued, when the village was officially labelled a ‘shrinkage area’ and privatized healthcare providers withdrew from the region due to depopulation. Beginning with an initiative by parents, like Sarah, to secure housing and care facilities for village youth with disabilities, soon various initiatives seeking to improve the location’s vitality and its residents’ health developed into a residence-based association. In 2016, the commercial care institution withdrew from the retirement home, ‘t Getijdenhuis. Then, the residents ‘took responsibility’ by forming a cooperative and negotiating legal ownership and entered into a partnership with a team of professional nurses, becoming responsible for the care facility’s daily operations.

Waddenburen residents played an active role in delivering community healthcare and social services for over 10 years. During my fieldwork in 2018, the Dutch King Willem-Alexander declared their cooperative a national example of a ‘caring community’, which public restructuring and decentralization privilege as part of a ‘community turn’ in healthcare provisioning (Macmillan & Townsend, Citation2006, p. 745).Footnote1 The cooperative’s origin story, outlined above, is part of a public discourse that foregrounds the turn to community as a matter of human affect (Fortier, Citation2010). In this discourse, residents ‘take care’ of their communities because they care about the health and wellbeing of proximate others. The narrative locates care as a quality of ethical relations between local citizens and reduces care-giving as a self-sustaining achievement of ‘strong’ socio-spatial relationships.Footnote2 Often left out, however, are the ongoing maintenance and repair activities required to preserve the socio-material infrastructure of care over time. Caring, J. Tronto (Citation1989) reminds us, cannot be reduced to the affective dimensions and emotional experiences of care-giving alone, but also encompasses a broad range of practical tasks oriented towards the (re)production of life (Milligan & Wiles, Citation2010). For ‘caring communities’ to come into being and sustain themselves, their infrastructures also require care. This article ask not why residents care about proximate others, but rather what caring for a communal infrastructure means in practice.

In similar setting of institutional deficit, scholars have conceptualized citizen initiatives aimed at the repair and replacement of broken public or private infrastructures as newly emerging commons (Berlant, Citation2016). The cooperative, likewise, can be seen as an emergent health commons that brings together not just patients, but also neighbours, nurses, government workers, local entrepreneurs (see also Del Casino, Citation2014). While infrastructure often tends to be regarded as a stable material background to the ‘social’ (re)production of the commons (Federici, Citation2014), in the area where I carried out my fieldwork the material (re)production of infrastructure became the explicit foreground for commoning practices. Infrastructure became, following Bowker’s (Citation1994) terminology, ‘inverted’, almost by default, due to the breakdown of conventional infrastructural arrangements (Blok, Citation2016). Instead of discussions about how to organize the common good of public health, activities often centred around decorating the common room, garden maintenance, and installing fences, sensors, or particular furniture. For my interlocutors, the creation and cultivation of healthcare as a commons was intimately intertwined with the (re)production of a material infrastructure to maintain life-in-common.

Building on attempts to co-theorize infrastructure and the commons, this article adopts a more-than-human approach to commoning in public service delivery. Ash Amin’s (Citation2014) work on ‘lively infrastructure’ is exemplary in recasting citizens’ struggles for public service delivery in more-than-human terms. Amin recounts the story of settlement on the outskirts of Belo Horizonte in Brazil as a mise en scene by infrastructure. Zooming in on the ‘liveliness’ of infrastructure, Amin (Citation2014) reveals that commoning public services is performed by a socio-material network that includes citizens, but also ‘titles, pipes, bricks and pits’ (p. 156). In line with Amin’s work on the liveliness of infrastructure, I argue that it is the continuous maintenance of infrastructural relationships that include both human and non-human actors that enable the reproduction of healthcare as a commons. Articulating the ongoing infrastructural work of reproducing the commons, I employ insights from Maintenance and Repair studies that explore maintenance as a practice of material care (De Wilde, Citation2021; Denis & Pontille, Citation2015). These studies teach us that, despite its invisibility, persistent maintenance is crucial to sustaining any durable infrastructural collective (De Laet & Mol, Citation2000; Denis & Pontille, Citation2015, Citation2019; Graham & Thrift, Citation2007). Through an analytical lens that examines what maintenance and repair scholars capture as the ‘care of things’ (Denis & Pontille, Citation2015), I trace contestations over care for infrastructure ethnographically. By focussing on the mis en scene of infrastructure, I ask whose infrastructure and which commons are maintained. In so doing, I take up Amin’s (Citation2014) invitation to further our understanding of the materiality of commoning by focusing on how, and by what means, infrastructures in common are sustained in practice.

My analysis draws upon 12 months of ethnographic fieldwork. I present an in-depth case study of an area-based cooperative, through which residents have negotiated ownership over collective buildings and land, in order to retain a local infrastructure for public healthcare and communal wellbeing.Footnote3 To observe what it takes to organize and maintain community owned healthcare provisioning in everyday practice, I partook in voluntary work, such as gardening, preparing coffee and tea, and cleaning and tiding up tasks, and observed countless formal and informal meetings amongst cooperative members and between residents and other stakeholders, such as funding agents, politicians, and care professionals. I observed how everyday problems, challenges, and aspirations to sustain the cooperative’s health and community activities were articulated and negotiated in infrastructural practices. Additionally, I conducted 15 in-depth semi-structured interviews with a wide range of actors involved in maintaining and regulating participatory health practices: local volunteers, public officials, social workers, representatives of grant-making organizations, and social entrepreneurs. In the interviews, I inquired about what went well, what difficulties they encountered, and what could be improved to achieve durable communal infrastructures for public health.

Below, I elaborate upon conceptualizing commoning as ‘care of things’ by situating study of the commons in Infrastructure and Maintenance & Repair Studies. To explore what care of things entails in practice, I describe subtle contestations preceding a controversy over the ownership of a nursing home using infrastructure for the mise en scene. First, I analyse how an infrastructure for public health is made into a commons through adjusting the infrastructure to local know-how, skills, and labour and distributing healthcare among various actors and settings. Second, I provide ethnographic ‘snap shots’ of how local volunteers and care professionals struggle to maintain infrastructure in common and reveal how tensions emerge around mundane infrastructural challenges. By focusing on attempts to align infrastructure with various commons and heterogenous objectives, I demonstrate how care of an infrastructure for public health ‘opens up’ new ways of organizing health and being in common, while precluding the possibility of others. In conclusion, I reflect upon what lessons can be learned from commoning by attending to the material intricacies of infrastructural care and maintenance.

‘Care of things’: commons, infrastructure, maintenance

Although ‘the commons’ once denoted communal pastures in 15th-century England and sparked debates about ownership of shared natural resources and their enclosure (Hardin, Citation1968; Ostrom, Citation1990), acknowledging the heterogeneity of the commons has caused geographers to expand the idea of the commons beyond development of a fixed, ‘single’ theoretical scheme (Holder & Flessas, Citation2008; Noterman, Citation2016). Scholars thus call for practice-based, ‘thick’ descriptions of what, precisely, causes something to become common (Blomley, Citation2008; Bollier & Helfrich, Citation2015; Eizenberg, Citation2012; Linebaugh, Citation2008; Slavuj Borčić, Citation2020). Instead of stable entities, the commons ‘are conceived here as ongoing, always in the making, indissoluble wholes of human and nonhuman’ (Blaser & de la Cadena, Citation2017, p. 186) activity. Such practice-based accounts do not simply assume the object shared but raise critical questions about the work, relations, and scope required to make something common. As Blaser and de la Cadena (Citation2017) specify the task at hand:

[T]he idea of the commons and of commoning call forth an exploration of what making ‘things’ (objects, identities, concepts, ideas and so on) common implies, especially where things might (also) be uncommon

An important implication of this relational approach to commoning is that the collectives engaged in commoning cannot be assumed to be a particular type of community. Rather than viewing community, and the ‘things’ shared, as pre-existing entities, a relational approach to commoning examines the dialectical process through which communities and their commons are formed (Gibson-Graham et al., Citation2016; Huron, Citation2015). What makes, and sustains, an infrastructure in common is thus a question that warrants close ethnographic attention.

This approach resonates with pioneering studies of the sociality of infrastructure that indicate the recursive loops and co-constitution of infrastructure and commonality (P. Harvey et al., Citation2016). Infrastructures do not simply undergird or mirror social relations, but, in fact, actively shape and reconfigure them (Jensen & Morita, Citation2017; Star, Citation1999). From this perspective, objects do not figure as passive receivers of social order, but instead have the agency to infrastructure the social (Amin, Citation2014). Whilst it is true that infrastructures have performative effects and shape sociality, they do not operate on their own. As Carse (Citation2014) points out, infrastructures ‘require human communities to maintain them, even as they shape those (and other) communities’ (p. 219). Thus, I conceive infrastructured commons as ‘achievements that remain fragile’ (P. Harvey et al., Citation2016, p. 11) unfolding in ‘the situated practices of those who live and work with’ them (Strebel, Citation2011, p. 248).

Maintenance & repair studies take this fragility as a starting point for exploring the continuous (re)production of socio-material order (Denis & Pontille, Citation2015, Citation2019). Building on feminist-inspired work on care practices (Mol et al., Citation2010), they mobilize the analytics of ‘care of things’ to capture the ongoing care work that accompanies fragility (Denis & Pontille, Citation2015, p. 355). Examined through the analytical lens of ‘care of things’, the material permanency of infrastructures is questioned and translated into a question of ‘maintainability’ (De Wilde, Citation2021; Denis & Pontille, Citation2015): how do infrastructural collectives hold together and sustain themselves in the face of constant decay (Graham & Thrift, Citation2007)? Attention to care of things, thus, ‘bring[s] to the surface the care work that underlies the production of sociomaterial order’ (Denis & Pontille, Citation2015, p. 361). Yet, precisely because of infrastructure’s permanent fragility, and the continuous work invested in its stability, infrastructural maintenance ‘can be designed in many different ways in order to produce many different outcomes and these outcomes can be more or less efficacious’ (Graham & Thrift, Citation2007, p. 17). Caring for infrastructure does thus not preserve pre-existing order, but is instead a performative, creative practice (Denis et al., Citation2016, p. 5) of continuously tailoring, adjusting, and aligning infrastructures in response to emerging situations (De Wilde, Citation2021, pp. 5–6).Footnote4

Whilst infrastructure may connect ‘us’ humans and nonhumans in socio-material associations (Amin, Citation2014, p. 138), precisely how infrastructures make community and do or do not sustain commonality cannot be assumed. Blaser and de la Cadena (Citation2017) propose the notion of uncommons to highlight that the shared thing, or what is ‘common’, may be an object of divergence. Not assuming that what convenes actors is a homogenous interest, the uncommons evokes a heterogeneous ‘we’ and diverging ways of relating to an object held in common. The notion of the uncommons thus raises the question of the extent to which, or as Blaser and de la Cadena (Citation2017) put it, ‘[h]ow far does the shared domain that constitutes a community extend?’ (p. 186). That is, what if the community caring for an infrastructure, does not, or not always, align with regard to how and for whom that infrastructure should be maintained? I describe how different variations of caring for infrastructural arrangements enact infrastructure as an uncommons. The story starts with a controversy.

A controversy: ‘the battle of ‘t Getijden huis’

As part of his commitment to stimulate ‘caring communities’, King Willem-Alexander annually visits citizen projects that include communal services that ‘take care’ of neighbours and community members. In autumn 2018, Waddenburen was nominated for such a royal visit. The residents took the king on a carefully-prepared tour that demonstrated how they had renovated and transformed a former retirement home into communal care facilities for the elderly, youth with disabilities, and preschool children. They furthermore took him to see the surrounding garden and abandoned church, both renovated by the villagers and opened for communal activities. Although they admitted that there had been ‘obstacles’ along the way, the residents presented the infrastructure created in common as a relatively stable achievement.

Shortly after the king’s visit, newspapers reported a scandal. The entire nursing team of 17 employees resigned publicly stating: the care can and should be better organized. Two years after the inception of the cooperative, local volunteers and professional staff disagreed on how to manage healthcare. Some volunteers and nursing staff claimed that ‘care money’ had been spent on ‘non-medical’ activities, such as renovating the church for communal activities. Nurses furthermore complained that they had to devote working hours to what they considered non-caring activities, such as writing newsletters for the community, organizing community festivities, and staffing the reception desk. The villagers protested that the nursing team attempted to stage a ‘coup’ by restricting access to the nursing home building. The conflict deeply divided the villagers, who spoke of ‘the battle of ‘t Getijden Huis’.

In the media, the controversy was framed as an agnostic struggle between individual citizens and professionals. Articles titled ‘Care money spent on other activities’ and ‘Fights for months in the king’s pet project’ dominated the newspapers. What started out as a ‘national example’ of Dutch participatory healthcare quickly developed into a public controversy about mismanagement of public funds and the cooperative was presented as a failed ‘social’ experiment. As Berlant (Citation2016) remarks regarding the difficult work required to infrastructure the commons, however, ‘a failed episode is not evidence that the project was in error’ (p. 414). On the contrary, the question the controversy opened up is precisely how a durable communal infrastructure for public health is continuously achieved in practice.

Considered through an analytical lens of care, failure and fragility are inevitable and rather instructive for understanding unfolding tensions and shifting problems (Mol et al., Citation2010, p. 14). In the maintenance practice in and around ‘t Getijdenhuis I observed during fieldwork, the infrastructure appeared vulnerable, and in continuous need of care (Denis & Pontille, Citation2015). It was only when controversy arose, and the project’s stability was explicitly questioned, that I started to see the relevance of these mundane infrastructural challenges to sustaining or not sustaining the commons. By tracing how tensions and shifting problems unfolded in the making and maintaining of an infrastructure in common, I will outline the shared, local work involved, first, in making, and second, in sustaining an infrastructure in common.

Making public health ‘common’

Adapting infra to local know-how, skills, and labour

Waddenburen’s villagers were very well aware of the local situation in which they operated. Although they refused the label, ‘shrinkage area’, (‘We have always been a sparsely populated area’), they recognized that privatized healthcare institutions withdrew from the region due to an insufficient number of clients to maintain profit margins. To retain healthcare in the village, they proposed adapting healthcare services to their local situation. To explain what this method entails, Sarah, considered the ‘founding mother’, compared it with maintaining a household:

The organisation of society is based on columns. This structure is based on quantity, more or less according to the urban model. This is not possible here in a sparsely populated area. Here, facilities disappear. We therefore develop on the basis of holistic principles. This means that we come up with solutions based on the principle of a household. Everything in a household is interconnected. Some decisions are economically related. Other choices you make, despite them being costly. You make them because they have meaning in a different way. For example, because you want to keep something. … This holistic approach is of great importance in a sparsely populated area, because, here, facilities cannot be maintained independently from each other.

Rather than counting the number of clients, Sarah thus regards healthcare as a ‘household’ embedded in community activities and needs. Such an approach starts from the question ‘what is needed?’ to retain healthcare in the village and contrasts with the organization of public health according to institutionalized standards.

The government outsources safety inspections of public-private spaces to various agencies. Care providers are obliged to hire one of these agencies to check compliance with safety rules, according to nationally established protocols. When the cooperative took over running the nursing home from the former care institution, it was initially declared that safety standards in the building met the government-established requirements, but in practice the residents found that these standards had not, or not wholly, been met. Take, for example, the question of whether ‘t Getijdenhuis was infested by legionella bacteria. Various agencies carried out inspections according to government protocols, but none appeared to be in possession of sufficient information. Nevertheless, decisions were taken on the basis of these inspections. As a result, the cooperative had to change the water pipes, which later turned out unnecessary. To better deal with (costly) situations like these, a local technical maintenance team was formed. A rotating group of volunteers signals, maintains, and repairs technical glitches in and around the buildings.

One of the first interventions the technical team carried out was adapting the buildings’ energy infrastructure. The first time I visited Waddenburen, Frans, one of the technical maintenance team volunteers, proudly showed me the adaptations the cooperative had carried out to reduce energy use. One of the changes they had made was to instal movement-sensitive lightening, which turns on when someone makes use of a space and automatically switches off when there is no activity. In a large building with long hallways, this prevents energy wasting and lowers structural costs. The renovations to the building’s electric infrastructure were important, Sarah told me later, not only because of the goal of transitioning to energy neutrality in the future, but also because it made running the building affordable. Thus, employing local expertise to prevent high levels of energy use and adaptations to the infrastructure allows care to remain in the village. Maintenance of the building is not only adapted to fit the local situation, such in-situ solutions are also stored in a community of practice and embedded in a local environment (Henke, Citation2019, p. 259).

On its website, the cooperative proudly states that since it became the legal owners of ‘t Getijdenhuis in 2016, the building ‘is no longer a retirement house’, but a compound with apartments where young and old can live as part of the village community and access care services whenever they need. Yet, at the time of my fieldwork ‘t Getijdenhuis still resembled a retirement house. With its blocky, box-like construction, yellow facades, and sandy bricks, from the outside, the building is typical of modern Dutch retirement houses’ architectural style. While the interior had undergone minor modifications, such as the creation of a library corner and walls decorated with photographs of inhabitants and villagers, the functional canteen and long corridors with carpeted floors betrayed its recent past. To enable the estate’s new function, the building required a fundamentally different appearance. One cooperative member, a retired landscape architect, for instance, drew plans to redesign ‘t Getijdenhuis as an ‘open’ space:

Now the building is somewhat hidden away behind a parking lot, which is not good. It should be completely transparent and on the ground floor. The main entrance should receive a lot of natural light, so you can directly glance through and see if your friend is sitting there, drinking coffee. If so, you drop by. So, yes, it should be totally open.

The ‘transparent’ redesign of the building is important, according to the architect, as it will merge the former nursing home with the village surrounding it. As such, she envisions the ‘t Getijdenhuis becoming the village’s new social centre. In a similar vein, teams of volunteers and local professionals renovated the old, neglected, monastery garden and abandoned church surrounding the nursing home to make them available as commons. Adaptations in the infrastructure’s material arrangement by means of local know-how, skills, and labour thus aimed to ‘open up’ the former privatized healthcare institution to communal forms of use and maintenance. Such adaptations not only restore a situation to its previous state, but actually provide local situations with practical new, innovative solutions (Denis & Pontille, Citation2015; Graham & Thrift, Citation2007, p. 5).

The importance of infrastructure was, however, not always visible to those not directly involved in caring for it. When infrastructure is in place and day-to-day care services resume normalcy, infrastructure quickly dissolves into the material background (Star, Citation1999). At a meeting of the general membership, one of the cooperative members inquired, for instance, what they actually get ‘in return’ for their small membership fee. Anticipating such a question, Nico, one of the board members, prepared a slide show, depicting the renovated infrastructure. He carefully compiled photographs of the situation before and after the cooperative formed to demonstrate the transformation of the infrastructure. We saw, for example, the overgrown monastery garden and decayed church next to pictures of a well-tended garden full of flowers and the church’s newly installed heat pump. Reiterating the question, what do members receive in return for their membership fee, Nico responded:

Well, all this! That you can stay living here when you grow old. That the church remains at the disposal of everyone in this room. So use it! It’s simple. If you like to play piano, put a piano in the church and give a concert to friends, family and neighbours. So, what do you get in return? A garden that belongs to the village again, where you can have a stroll or a picnic, meet up with neighbours and friends. This is what you become a member of. But you have to do it. You have to use it.

Nico’s speech resonates with what Lea and Pholeros (Citation2010) find in a study on (dysfunctional) housing provisioning for aboriginal communities, that is, material infrastructure, and its aesthetics, ‘is no guarantee of a functioning infrastructure’ (Harvey et al., Citation2016, p. 4). Yet, precisely how infrastructures are used and maintained in common is no straightforward issue in practice.

Maintaining an infrastructure in common

Attempts to open up the infrastructure for public health to include local know-how, needs, and activities to the community also met with resistance, coinciding with the emergence of new boundaries and exclusions. Moreover, as I show below, in the mundane maintenance practices performed by my interlocutors, various commons compete for infrastructural stabilization. Here, I provide three examples of attempts to ‘open up’ infrastructure to the heterogeneous needs of multiple commons that create tension regarding attempts at stabilizing some commons.

Maintaining an assisted living facility, house of the village, or resource?

According to some members, the estate’s common room should function as a ‘house of the village’, a place where anyone could pop by for an affordable, healthy meal, or just sit and have a cup of coffee. To integrate the common room with the village, some members started a small shop of ‘forgotten groceries’ (the supermarket was located in another village down the road). At a fixed time every morning, volunteers made sure there were fresh pots of coffee and tea ready for anyone who wanted to join from inside and outside ‘t Getijdenhuis. But not all cooperative members were in favour of ‘opening up’ the nursing home for non-residential use. The nursing team, for instance, were concerned about the impact of a permeable building on the health of their clients, some of whom they considered ‘vulnerable’. The nurses argued that ‘t Getijdenhuis promised their clients to be a place of sheltered living and found that an ‘open building’ disrupted the privacy and safety of their clients and the nursing staff. In a folder disseminated among the villagers, staff members stressed that they work according to the norms of their profession and the regulations formulated by law. The privacy law, for instance, prescribes that, in principle, every visitor should register upon entering the ‘private’ domain of a care centre. In practice, in ‘t Getijdenhuis, considered a common place by the villagers, this became untenable: people come and go without registration.

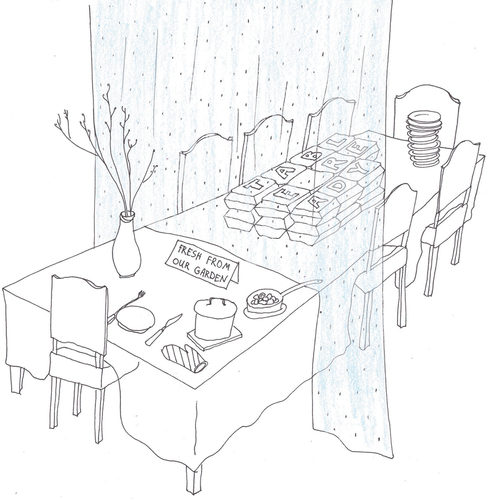

The composition of the tables in the common room mediated the tension between permeability and enclosure of the building. Initially, the nursing team had set up the coffee tables in small units scattered around the hallway so that clients and their visitors could talk privately. When the nursing team resigned and permanently withdrew from the building, redistributing the common room’s tables was one of the first things the cooperative members did. Instead of square units dispersed across the space they created one long vertical table. When I visited ‘t ‘t Getijdenhuis at that time, multiple villagers commented on the different table composition, which according to them, really invited villagers to walk in and join the long coffee table for conversations. In the nursing practices the common room is enacted as a ‘closed’ space, secured with standards about privacy, interaction, and security. Yet, in the practices of the volunteers, the building is enacted as an ‘open’ house: part of village routines, with permeable boundaries into community life (). The mis en scene of infrastructure, thus, seems to make possible some commons, such as gatherings among neighbours, while making less attainable the successful enactment of another commons, like a safe space for nursing home clients and staff.

A similar tension between different infrastructural arrangements became apparent in the use of the square outside ‘t Getijdenhuis. When Roel, a farmer and board member, took the representatives of a grant-making organizations on a tour of ‘t Getijdenhuis, he painted a vivid picture of a lively space where people from different generations meet and mingle. ‘Everything is mixed up here! Really, here, people from zero to a hundred drink coffee together’. Roel’s visitors were impressed. Yet, housing and taking care of people with different care needs is not a straightforward task when a building, designed with one particular user in mind, becomes shared among multiple users. Considering the needs of both children and the elderly requires adjusting the building to fit the situations of different users. Finding a compromise that satisfies the needs of all users does not always succeed.

Take, for example, the case of the (im)movable fence. The day care rents a space in the nursing home. One day, the day care administration decided that it needed to fence off the outside playground and protect the children. They came up with the idea of a movable fence, so that the fence could be removed when the children were not playing outside. In the end, however, an immovable fence was installed because a movable fence was too expensive. The immovable fence was regarded as problematic by some volunteers: the fence sets ‘t Getijdenhuis apart from community life, while the residents of ‘t Getijdenhuis, according to the volunteers, should feel integrated in, and part of, the community. As one volunteer put it: ‘Now the elderly people live behind a fence!’ The immovable fence thus meditates (Amin, Citation2014), or infra-structures, the shared outside space as an enclosed playground, instead of shared place for villagers and nursing home residents.

To those responsible for the financial stability of ‘t Getijdenhuis, however, the movable fence was an impractical solution. As Henk, responsible for the management of the building explained:

A vision is good and important, but can a vision always be reconciled with the requirements of commercial rental? We are not talking of small amounts. It [the cost] quickly amounts to a total of one million per year. You have to deal carefully with such a large sum of money. We rent rooms to all these different target groups in ‘t Getijdenhuis. You have the elderly, people with disabilities, and people who just want to live sheltered. It’s a very complex business.

For those responsible for renting the rooms and maintaining the stability of ‘t Getijdenhuis as a resource, expensive movable fences can thus be considered a ‘careless’ decision. Hence, maintaining the fluidity of an ‘open’ building for communal activities may clash with maintaining a safe infrastructure for clients of the nursing team, as well as with maintaining the stability of the infrastructure as a business. The practices involved in stabilizing an infrastructure of public health in common, may thus, ‘add to some common worlds and not others’ (Gill, Citation2017, p. 71).

Maintaining aesthetic gardens or safe common places?

When the village cooperative became the legal owner of both the nursing home and the area surrounding the compound, one of the first things it did was to make the overgrown, neglected monastery garden attractive and accessible for villagers and visitors. When renovating the old monastery garden, volunteers did not just restore the historic walking trails, but also took special care to adapt the trails to make them accessible for people who use walkers or wheelchairs. They had installed relatively flat bridges that conveniently connected different parts of the garden. Thus, the renovation of the garden not only strove for aesthetic renewal, but also to encourage an inclusive sharing of place. However, making the garden available and accessible was not sufficient to guarantee ongoing safe use of the garden. When in use, the garden needs to be continuously maintained to remain accessible and a common place. Different users of the garden, however, do not easily align.

The smooth surface and convenient connections introduced a new problem in terms of maintaining the walking paths as an inclusive shared place. Parents who dropped their children off at the day care before their work, often in a hurry, used the renovated walking trails as cycling ‘highways’. Moreover, when, one winter, the walking trails came covered in green algae, which made the surfaces slippery and inaccessible, garden users filed complaints with the garden volunteers. In response, Sarah wrote a letter to the cooperative’s board to express her worries about the use and maintenance of the garden:

From 2010 to the present, I have been working as a volunteer in the garden and I see how the garden is appreciated, but also used, by dog lovers, cyclists, and wild flower pickers. When the paths are slippery, they come to my door with the comment, ‘Those paths are slippery’; ‘you’ have to do something about it! As if we were the government. The volunteers on Thursday always have to deal with dog poo.

The accessible walking trails thus presented new, shifting, problems, such as hasty cyclers, algae, and dog poo, for the ongoing maintenance of the garden as a clean and safe place for ‘everyone’ (). The garden’s initial renovation ‘opened up’ the space to be used and maintained by everyone, but did not automatically result in stabilizing a safe place for all the commons formed by the everyday use of the garden. The garden, as a shared object, thus, emerges as a heterogenous ground where negotiations over the commons take place (Blaser & de la Cadena, Citation2018, p. 13). To make and maintain the garden in common is a ‘continuous achievement’ and requires ongoing efforts to align the heterogeneous needs of various commons (p. 13).

Maintaining sustainable cooking or tasty food?

The former retirement home came with a fully equipped kitchen. When Sarah first showed me the monastery garden, she proudly explained that the harvested vegetables would be used in the kitchen to feed the residents of ‘t Getijdenhuis. In preparation for the visit of the king, pumpkins were placed in the vegetable garden of a residence-based care cooperative, though they had already been harvested, to visually represent its self-sustainability.

As with the landscape surrounding ‘t Getijdenhuis and the building itself, there was internal disagreement among the cooperative members and employees regarding whether the professional kitchen should cook only for the residents of ‘t Getijdenhuis, or serve meals to the general community. The landscape architect cited the example of a friend, who lives near the nursing home. The friend is old, but lives independently. Recently, she had surgery on her knee, which was not completely successful, resulting in impaired mobility. The architect considered it a good idea that ‘t Getijdenhuis offer inexpensive, healthy meals to people like her friend. The garden volunteers, likewise, were keen on the idea that their harvested vegetables and herbs could be used in the nursing home’s kitchen to serve nutritious meals and bolster the self-sustainability of the cooperative.

In practice, aligning these sustainable cooking practices with the diverging tastes of prospective eaters was difficult. Karin, one of a few non-medical staff with a paid position, concerned herself with reorganizing the kitchen. According to the administration, the kitchen had been “in the red” for a long time already. The recently hired chef lacked clarity about the kitchen’s purpose. Was she to cook only for the residents of the nursing home? Or for a larger public? Moreover, the majority of nursing home residents did not order meals from the kitchen, but made use of a commercial food service called Table Ready that sold pre-cooked meals, which only required microwave heating before serving. In an attempt to better align the kitchen’s cooking practices with residents’ eating preferences, Karin prepared a short survey for the residents of ‘t Getijdenhuis asking what they like to eat. It turned out that the elderly residents were not happy with the fresh, unfamiliar vegetables from the garden. They preferred their vegetables cooked until they were falling apart. Moreover, while they appreciated choice, for them this meant choosing between two different potato dishes. In response, the chef did not see the purpose of cooking with fresh vegetables from the garden, and those remained in the freezer. The younger residents in the assisted living facilities said, on the contrary, that they appreciated the meals made with fresh produce. Karin, therefore, proposed to the chef to focus her cooking on the younger residents, while the elderly residents could order from the commercial service that offered affordable meals.

While the garden practices enacted the kitchen as an infrastructure to realize a healthy, self-sustaining community, the nursing home clients preferred cooking practices that catered to their appetites (). Some commons thus fail to be enacted through infrastructure due to a discrepancy between new infrastructural practices and already-existing eating routines. Care for infrastructure thus sometimes entails making practical compromises between ‘old’ and ‘new’ commons (Mol et al., Citation2010, p. 13).

Discussion: caring for whose infrastructure, which commons?

In the cooperative’s maintenance practices, the community does not figure primarily as a collective of people in the same geographical location, but rather as various situated collectives that emerge around care for infrastructure. The commons that emerge, and endure, in this maintenance work are an effect of variously constituted socio-material relations. For example, the functioning of the common room as the ‘house of the village’ or an enclosed space for clients is linked to the nurses and volunteers who compose the space, regulate access, and distribute coffee, tea, and meals, as well as the furniture, gates, and sensors that infrastructure the various collectives present in the space. Commoning, here, thus constitutes a ‘site of forging and stabilizing – that is, infrastructuring’ (Blok, Citation2016, p. 104). These more-than-human collectives forge and stabilize health as a commons. But what, exactly, is being maintained in common?

As in other health settings experiencing restructuring and decentralization programmes, the boundaries between spaces formerly considered public or private, institutional and non-institutional, have become blurred (Milligan & Wiles, Citation2010, p. 747). Yet, although various collectives convene to maintain the cooperative’s buildings, spaces, and health services, they do not necessarily maintain the same ‘thing’. Local volunteers and neighbours gather and take care of the common room to engage in informal community activities, such as eating together, socializing, and helping each other. In these practices, the common room maintains the togetherness and wellbeing of a neighbourhood community. Nurses care for the common room as a place to nurture the comfort, safety, and health of (some) vulnerable clients. Here, the common room constitutes an institutionalized space for regulating care of specific needs and sheltered living. For those who take care of the nursing home as real estate, balancing out the needs of various target groups, the commons is constituted as financially sustainable places. Infrastructuring, then, does not adhere to a single logic of what ‘the’ commons entails, but follows different courses.

While infrastructure may assemble collectives, it can also become an object of divergence and obstruct commonality. Sharing a space with clients who have a perceived need for security and an enclosed environment may not be easily reconcilable with its function as an open ‘house of the village’. Likewise, for elderly people who want to remain part of village life, the space may require different infrastructuring from that which suits parents whose young children need not only space to play, but also a barricade to keep them from crossing the street. The stabilization of some commons, through fences or the arrangement of tables, may thus preclude the realization of other, equally relevant commons.Footnote5 Rather than conceiving of these divergences as obstacles to overcome, geographers can take these ‘uncommons’ as a productive starting point for the ‘heterogenous grounds where negotiations take place towards a commons that is a continuous achievement’ (Blaser & de la Cadena, Citation2018, p. 24). The building, with its immutable walls, divisions of space, and multiple functions does not automatically bend to accommodate diverging needs. That requires difficult negotiations and, most importantly, ongoing care.

Annemarie Mol’s (Citation2021) work on eating inspires the idea that the doing involved in care constitute a task. In the clinic and the kitchen, Mol suggests, the doing involved in eating is not about healthy choices or a ‘natural’ process, but rather a task that involves people performing physical labour, though it is not confined to people alone. A task’s accomplishment depends on myriad things, including tools, places, and times near and far from the actor performing the task. Similarly, in Waddenburen, care for the infrastructure was demonstrated through various tasks. It entailed adapting the building’s infrastructure to fit the specific conditions needing to be met to provide care in a sparsely populated area. It required a local maintenance team to remain vigilant to catch the small and big glitches in the cooperative’s infrastructure. It demanded a willingness to learn and apply new knowledges to improve infrastructure: to tinker with (im)movable fences and furniture, to adapt walking trails to walkers and wheelchairs, and to attempt to align eating habits and cooking routines. Caring for infrastructure also included carefully distributing resources and mundane cleaning and tending activities to keep the space continuously accessible as commons.

Focussing on care for infrastructure thus allows us to explore the tensions involved in commoning as a practical accomplishment of infrastructuring, rather than as an act of virtue. These different variants of care carry with them various commons and ways of infrastructuring, which may conflict with each other. Infrastructuring is not necessarily good or bad, as the above example demonstrate. What is done to infrastructure a particular commons may be good for some but bad for others (Mol, Citation2021, p. 100–101). Sometimes, this requires making compromises among locally relevant commons, such as the solution Karin proposed to cook fresh vegetables from the garden for the youth and to serve the elderly residents pre-cooked meals from a commercial service. Yet, it is precisely these mundane negotiations, compromises, and adjustments that are never made public. They unfold rather quietly as part of the material practices of everyday care. The work, time, and resources invested in negotiating the tensions and divergences that emerge while achieving durable, infrastructured collectives thus largely remains invisible. In the cooperative’s maintenance practice, then, infrastructure silently sustains some forms of relating, while excluding others (Gill, Citation2017). Attending to the specificities of these variants of care and the different ways of relating they (fail to) sustain fosters a practice-based debate on commoning that does not shy away from disagreements, but rather cherishes different approaches to commoning, specific to research sites and practices (Domínguez-Guzmán et al., Citation2021, p. 14).Footnote6

Conclusion

Maintaining public health as a commons must be continuously realized. In this article, I have conceptualized this maintenance work as the ‘care of things’ (Denis & Pontille, Citation2015). By describing commoning as a mis en scene of infrastructure, I have made visible the difficulties in caring for and stabilizing an infrastructure in common that provides public healthcare delivery for local communities. First, I have shown how the commoning of infrastructure as a shared domain opens it up to include local know-how, skills, and labour. Then, I analysed the mundane problems and tensions that unfold in day-to-day maintenance, the infrastructuring, of various commons and focused on attempts to align infrastructure with the heterogenous needs of different commons. My case study thus illustrates the durability of the commons as a fragile, temporary, and continuous achievement of infrastructuring and echoes Ash Amin’s (Citation2014) call to acknowledge the agency of material objects in attempts to infra-structure, or mediate, the commons. Whereas feminist scholar Silvia Federici (Citation2014) captures the reproduction of the commons in the slogan, ‘no commons without community’ (p. 229), emphasizing commoning as a quality of social relations, I thus propose emphasizing the infrastructural reproduction of commonality: ‘no commons without infrastructuring’. Below, I reflect on three lessons that attending to the material intricacies of infrastructural care and maintenance teach us about the actualization of ‘actually existing commons’ (Eizenberg, Citation2012), especially where healthcare also emerged as uncommon (Blaser & de la Cadena, Citation2017).

First, analysing commoning through a mis en scene of infrastructural maintenance allows us to ethnographically unravel ‘the complications of other-than-human dimensions of the political relations that join and divide us’ (P. Harvey et al., Citation2016, p. 7). Maintaining an infrastructure in common, then, involves compromising not only between different principles of what makes for healthy ways of living (Heath, Citation2021, p. 1269) but also between different socio-material adjustments, or infrastructuring, of the shared object. The point here is not that one formation is better than another, but that care of nursing home residents may require a different infrastructuring from care of neighbours. It is thus that infrastructure divide or join ‘us’ and may cause to materialize certain common worlds, at the expense of others (D. Harvey, Citation2011, p. 102; Gill, Citation2017, p. 71). When conceptualizing the emergence of healthcare as a commons from this more-than-human perspective, we are consequently bound by specific places, materials, practices, and timing (Andrews & Duff, Citation2019). By focusing on mundane infrastructural practices, it becomes possible to empirically study how the commoning of healthcare ‘takes place’ within the temporary achievements of more-than-human assemblages (Andrews et al., Citation2014; Thrift, Citation2008). The political potential of taking infrastructure into account for the sake of strengthening the expansion of the commons over time, is thus in its capacity to offer a way to rethink ‘the very techno-material nature of that thing called “public” or “commons”’ (Corsín Jiménez, Citation2014, p. 358).

Second, considering the maintainability (De Wilde, Citation2021; Denis & Pontille, Citation2015) of infrastructure provides us with a note of caution in embracing the radical openness of the commons. Although my perspective fully aligns with the theoretical ambition of critical geographers to situate and trace the fluid emergence of heterogenous commons (Holder & Flessas, Citation2008; Noterman, Citation2016), my research findings also indicate the empirical limits of such fluidity when it concerns a place-specific infrastructure shared by various kinds of users. That is, although maintenance may hold the potential for remaking order in new ways, openness cannot always be sustained when social divisions are made from steel and bricks (Latour, Citation2000, p. 19). As J. C. Tronto (Citation1987, pp. 659–660) suggests, embracing an ethics of care with the potential for doing things differently entails engaging with the tensions and boundaries that arise as part of that care. Rather than desiring openness over en/closure, we may thus ask how various commons, and the tensions and differences that exist among them, are balanced and negotiated through infrastructure. This requires facilitation of specific goals and fostering differences and divergences among heterogenous commons. In the case of the cooperative, facilitation of a mutable fence, for instance, would constitute a fruitful way to foster the coexistence of diverging commons and heterogenous care needs.

Finally, although infrastructure may connect ‘us’, both humans and objects, in various socio-material constellations, it does not work on its own. Infrastructures require continuous care to maintain durability. To render the turn to community in healthcare as an exclusively social phenomena, as policymakers tend to do in health promotion strategies, therefore fails to grasp how the decentralization of healthcare occurs in practice. What holds together collectives that engage with healthcare is not intangible interpersonal relations, driven by affects, but rather a variety of infrastructural entanglements. This aligns with the work of feminist geographers who have highlighted an ethics of caring for place and environment that moves beyond seeing ‘subjects as simply human and places as human-centred’ (Gibson-Graham, Citation2011, p. 1). Recognising infrastructural engagement as ‘care-taking tasks’ (Conradson, Citation2003, p. 451) may be a first step towards shifting the terms of community engagement strategies within healthcare policies, from merely encouraging ethical relations amongst local citizens to addressing the tangible and material aspects of daily civic engagement in healthcare. This calls for studies that assess community engagement not only as a matter of (in)equal citizenship regarding ‘who can, is, or will be allowed to participate’ (Swyngedouw, Citation2005, 2000), but also as explorations of the contingency and material complexities of keeping an infrastructure in common by exposing ‘who cares how, when and for what’ (De Wilde, Citation2021, p. 1265).

Acknowledgments

Without the expertise and insights of the residents, volunteers, and professionals active in Waddenburen, who generously welcomed me into their cooperative and their lives, this research would not have been possible. I collaborated with visual artist Sophia Tabatadze to create insightful drawings that translate empirical arguments into a visual language. For commenting on numerous drafts of this article, I wish to thank Mandy de Wilde, Linda van der Kamp, and Jan Rath. My sincere thanks go to the anonymous reviewers and the editor for Social & Cultural Geography for their constructive feedback. This paper also benefited from inspiring feedback I received at the ESA summer school ‘Sociological Knowledges for Alternative Futures’ in Barcelona, and from the 2021 4S conference panel, ‘Centering Public Health’, where I presented an earlier version of my argument. Finally, I thank Helen Faller for her careful copyediting of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. Caring communities’ is the English translation of the Dutch policy term ‘Zorgzame gemeenschappen’ that refers to activating of private, local citizens in the public health domain via community. The Dutch term attributes the quality of caring (zorgzaam) as an ethical aspect of community.

2. Elsewhere I analyse this normative discourse as a technique of government, building on Foucauldian-inspired work on affective citizenship (Fortier, Citation2016), enabling the standardization of local citizens’ welfare initiatives on a national scale (Smits, Citation2022).

3. The study was undertaken following local ethics committee approval. To ensure anonymity, I stripped transcript excerpts, individual interviews, and observations of identifiers and used pseudonyms for respondents, places, and organizations.

4. For the link between Maintenance & Repair Studies’ analyses of ‘care of things’ and foundational work on feminist ethics, see De Wilde (Citation2021).

5. See also the detailed study by Curtis et al. (Citation2007) of tensions between enclosure and openness of space arising in the use of a London mental health inpatient unit.

6. For the argument that, in analysing the care for water and its irrigation infrastructure, social scientists should not reproduce care as a universal concept and overarching narrative, but instead pay attention to the diverse and specific ways care is carried out in the work required to maintain an infrastructure, see Domínguez-Guzmán et al. (Citation2021).

References

- Amin, A. (2014). Lively infrastructure. Theory, Culture & Society, 31(7–8), 137–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276414548490

- Andrews, G. J., Chen, S., & Myers, S. (2014). The ‘taking place’ of health and wellbeing: Towards non-representational theory. Social Science & Medicine, 108, 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.037

- Andrews, G. J., & Duff, C. (2019). Matter beginning to matter: On posthumanist understandings of the vital emergence of health. Social Science & Medicine, 226, 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.02.045

- Berlant, L. (2016). The commons: Infrastructures for troubling times. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 34(3), 393–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816645989

- Blaser, M., & de la Cadena, M. (2017). The uncommons: An introduction. Anthropologica, 59(2), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.3138/anth.59.2.t01

- Blaser, M. de la Cadena, M. Eds. (2018). A world of many worlds. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478004318

- Blok, A. (2016). Infrastructuring new urban common worlds?: On material politics, civic attachments, and partially existing wind turbines. In P. Harvey, C. Jensen, & A. Morita (Eds.), Infrastructures and social complexity (pp. 120–132). Routledge.

- Blomley, N. (2008). Enclosure, common right and the property of the poor. Social & Legal Studies, 17(3), 311–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663908093966

- Bollier, D., & Helfrich, S. (Eds.). (2015). Patterns of commoning. The Commons Strategy Group/Off the Commons.

- Bowker, G. (1994). Information mythology and infrastructure. Information Acumen: The Understanding and Use of Knowledge in Modern Business, 231–247.

- Carse, A. (2014). Beyond the big ditch: Politics, ecology, and infrastructure at the Panama Canal. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262028110.001.0001

- Conradson, D. (2003). Geographies of care: Spaces, practices, experiences. Social & Cultural Geography, 4(4), 451–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464936032000137894

- Corsín Jiménez, A. C. (2014). The right to infrastructure: A prototype for open source urbanism. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 32(2), 342–362. https://doi.org/10.1068/d13077p

- Curtis, S., Gesler, W., Fabian, K., Francis, S., & Priebe, S. (2007). Therapeutic landscapes in hospital design: A qualitative assessment by staff and service users of the design of a new mental health inpatient unit. Environment & Planning C, Government & Policy, 25(4), 591–610. https://doi.org/10.1068/c1312r

- De Laet, M., & Mol, A. (2000). The Zimbabwe bush pump: Mechanics of a fluid technology. Social Studies of Science, 30(2), 225–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631200030002002

- Del Casino, V. J. (2014). Commoning, health and well-being. Social & Cultural Geography, 15(8), 982–983. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2014.916996

- Denis, J., Mongili, A., & Pontille, D. (2016). Maintenance & repair in science and technology studies. TECNOSCIENZA: Italian Journal of Science & Technology Studies, 6(2), 5–16. .

- Denis, J., & Pontille, D. (2015). Material ordering and the care of things. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 40(3), 338–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243914553129

- Denis, J., & Pontille, D. (2019). Why do maintenance and repair matter? In A. Blok, I. Farías, & C. Roberts (Eds.), The routledge companion to actor-network theory (pp. 283–293). Routledge.

- De Wilde, M. (2021). A heat pump needs a bit of care: On maintainability and repairing gender–technology relations. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 46(6), 1261–1285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243920978301

- Domínguez-Guzmán, C., Verzijl, A., Zwarteveen, M., & Mol, A. (2021). Caring for water in northern Peru: On fragile infrastructures and the diverse work involved in irrigation. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 5(4), 2153–2171. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486211052216

- Eizenberg, E. (2012). Actually existing commons: Three moments of space of community gardens in New York City. Antipode, 44(3), 764–782. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00892.x

- Federici, S. (2014). Feminism and the politics of the commons. In D. Bollier & S. Helfrich (Eds.), The wealth of the commons: A world beyond market and state (pp. 206–247). Levellers Press.

- Fortier, A. M. (2010). Proximity by design? Affective citizenship and the management of unease. Citizenship Studies, 14(1), 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621020903466258

- Fortier, A. M. (2016). Afterword: Acts of affective citizenship? Possibilities and limitations. Citizenship Studies, 20(8), 1038–1044. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2016.1229190

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2011). A feminist project of belonging for the Anthropocene. Gender, Place & Culture, 18(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2011.535295

- Gibson-Graham, J. K., Cameron, J., & Healy, S. (2016). Commoning as a postcapitalist politics 1. In Releasing the commons (pp. 192–212). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315673172-12

- Gill, N. (2017). Caring for clean streets: Policies as world-making practices. The Sociological Review, 65(2), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081176917710422

- Graham, S., & Thrift, N. (2007). Out of order: Understanding repair and maintenance. Theory, Culture & Society, 24(3), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276407075954

- Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science, 162(3859), 1243–1248. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.162.3859.1243

- Harvey, D. (2011). The future of the commons. Radical History Review, 2011(109), 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-2010-017

- Harvey, P., Jensen, C. B., & Morita, A. (2016). Introduction: Infrastructural complications. In P. Harvey, C. Jensen, & A. Morita (Eds.), Infrastructures and social complexity (pp. 19–40). Routledge.

- Heath, S. (2021). Balancing the formal and the informal: The relational challenges of everyday practices of co-operation in shared housing co-operatives in the UK. Social & Cultural Geography, 22(9), 1256–1273. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2020.1757138

- Henke, C. R. (2019). Negotiating repair: The infrastructural contexts of practice and power. In I. Strebel, A. Bovet, & P. Sormani (Eds.), Repair work ethnographies (pp. 255–282). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Holder, J. B., & Flessas, T. (2008). Emerging commons. Social & Legal Studies, 17(3), 299–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663908093965

- Huron, A. (2015). Working with strangers in saturated space: Reclaiming and maintaining the urban commons. Antipode, 47(4), 963–979. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12141

- Jensen, C. B., & Morita, A. (2017). Introduction: Infrastructures as ontological experiments. Ethnos, 82(4), 615–626. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2015.1107607

- Latour, B. (2000). The berlin key or how to do words with things. In P. Graves-Brown (Ed.), Matter, materiality and modern culture (pp. 10–22). Routledge. 1993 .

- Lea, T., & Pholeros, P. (2010). This is not a pipe: The treacheries of indigenous housing. Public Culture, 22(1), 187–209. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2009-021

- Linebaugh, P. (2008). The magna carta manifesto: Liberties and commons for all. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520932708

- Macmillan, R., & Townsend, A. (2006). A ‘new institutional fix’? The ‘community turn’ and the changing role of the voluntary sector. In C. Milligan & D. Conradson (Eds.), Landscapes of voluntarism: New spaces of health, welfare and governance (pp. 15–32). Bristol University Press.

- Milligan, C., & Wiles, J. (2010). Landscapes of care. Progress in Human Geography, 34(6), 736–754. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510364556

- Mol, A. (2021). Eating in theory. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478012924

- Mol, A., Moser, I., & Pols, J., Eds. 2010. Care in practice: On tinkering in clinics, homes and farms. Transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1515/transcript.9783839414477.

- Noterman, E. (2016). Beyond tragedy: Differential commoning in a manufactured housing cooperative. Antipode, 48(2), 433–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12182

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge university press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511807763

- Slavuj Borčić, L. (2020). The production of urban commons through alternative food practices. Social & Cultural Geography, 23(5), 660–677. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2020.1795234

- Smits, F. (2022). Intimate standardisation: How the activating welfare state localises citizens and standardises welfare. Citizenship Studies, 26(2), 184–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2022.2036104

- Star, S. L. (1999). The ethnography of infrastructure. The American Behavioral Scientist, 43(3), 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027649921955326

- Strebel, I. (2011). The living building: Towards a geography of maintenance work. Social & Cultural Geography, 12(3), 243–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2011.564732

- Swyngedouw, E. (2005). Governance innovation and the citizen: The janus face of governance-beyond-the-state. Urban Studies, 42(11), 1991–2006. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500279869

- Thrift, N. (2008). Non-representational theory: Space, politics, affect. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203946565

- Tronto, J. (1989). Women and caring: What can feminists learn about morality from caring? In C. C. Gould (Ed.), Key concepts in critical theory: Gender (pp. 282–289). Humanities Press.

- Tronto, J. C. (1987). Beyond gender difference to a theory of care. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture & Society, 12(4), 644–663. https://doi.org/10.1086/494360