ABSTRACT

Despite the EU accession of the Republic of Cyprus in 2004, the “Green Line” dividing Cyprus that was added as a border in 1974 remains an external EU-border between the Republic of Cyprus (RoC) and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), a self-proclaimed state internationally recognized exclusively by Turkey. Pro- and con European attitudes on Cyprus are therefore not recent phenomena, but date back to the start of EU accession negotiations in 1998 and the Annan-Plan for reunification in 2004. These aspects, however, refer to the Turkish-Greek antagonism on the island and the ongoing national tensions that have resulted in violent conflicts since independence in 1960, the establishment of a demilitarized UN Buffer Zone in 1964 and the division of the island in 1974, also cutting through the island’s capital Nikosia/Lefkoşa. Drawing on fieldwork from 2004/2005 and 2014/2015 regarding the border’s shifting meanings and pointing to the border as a place where pro- and con-EU-articulations converge, emphasis is placed on the borderscape in Nikosia/Lefkoşa that impedes and increases the movement of people and goods. After all, the border is a dividing line that both shapes and exhibits identities. Moreover, it serves as an individual economic resource whilst border-crossings likewise offer benefits. Nevertheless, the border also stands as painful emotional remembrances for people on both sides. The pro- and con-EU attitudes that were dominant when the RoC joined the EU in 2004 have thus been blurred on both sides of the Green Line. The empirical research for this paper has been framed by the question of how this blurring is intertwined with the division of Cyprus and how people are affected by the Green Line as a socio-material and symbolic artefact on the micro-scale of personal feelings, identities and practices.

Introduction

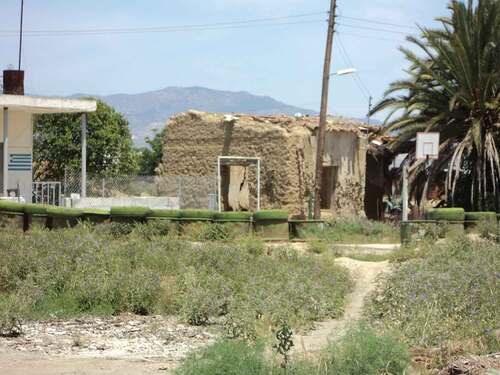

The Green Line and the UN Buffer Zone that divide Cyprus, which have served as a closed border from 1974 to 2004, de jure do not exist any longer. Yet, they act de facto as an external EU border situated between the Republic of Cyprus (RoC, EU-member since 2004) in the south of the island and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), a self-proclaimed state internationally recognized only by Turkey. The EU accession negotiations since 1998 and the UN plan for reuniting Cyprus in 2004 have thus comprised both policy and public debates on Europeanization, including pro- and con-EU-attitudes. Additionally, they refer to the Turkish-Greek antagonism and the ethno-national tensions on the island that have resulted in violent conflicts since independence was declared in 1960, the subsequent establishment of a United Nations Buffer Zone in 1964, and the division of the island in 1974, likewise cutting through the island’s capital Nikosia/Lefkoşa (Constantinou Citation2008; Demetriou Citation2007; Oktay Citation2007; Peristianis and Mavris Citation2011). The buffer zone divides the former heart of the city in an east-west direction, running through its medieval centre and its former commercial centre. Due to the partition, building remnants dominate the atmosphere in and along the ‘dead zone’. The streets located close to the border are obviously blind alleys and have mostly been used as light industrial facilities and wholesale units since 1964 in the south. In the north, the area consists of low-income residential neighbourhoods and tire shops. The buffer zone with its UN watchtowers, barricades and destructed buildings was, and remains “visually demoralising” (Oktay Citation2007, 237; see also ). Despite the removal of the downtown border-wall in the former main street (Ledra Street) in 2008, most residents in Nikosia/Lefkoşa continue to turn their backs on the border in everyday life, while people from both sides proceed to cross the border on a nearly daily basis, likewise accompanied by tourists. The ways that the Green Line actually affects people in both parts of the city remain understudied. In this paper, this is analysed by conceiving parts of the city as borderspaces and borderscapes.

Considering my fieldwork in 2004/2005 and 2014/2015 on the border’s shifting meanings and effects both as barrier and resource over the last decade, leading to the border as a symbolic and material place where attitudes towards and against Europeanization converge, this paper concentrates on the borderspaces in Nikosia/Lefkoşa that impede and increase the movement of people. The border as a dividing line has shaped people’s personal histories and identities. Yet it is also a resource in the sense of external funding, individual remembrances and financial benefits or simply curiosity and excitement (Bryant Citation2012; Papadakis Citation2018). Notably, the pro- and con-EU attitudes that were dominant when the RoC joined the EU in 2004 have been blurred on various levels as well as on both sides of the Green Line.

The contribution focuses on the economic, social and cultural origins and effects of border-related polarizations and links them to the Europeanization process of the island since 1998 and to EU-phoria and Eurocriticism in daily life. However, since the division of Cyprus also refers to larger geopolitical dimensions, especially the unresolved Turkish–Greek conflict and the ongoing negotiations for reunification, the EU itself is less of an issue in day-to-day concerns than a political matter concerning the border. Consequently, the paper first sets the scene, drawing on conceptual considerations when encountering and researching the border. In the following two sections, a short summary of the division of Cyprus and the impact of Europeanization will be presented. Subsequently, trajectories of pro- and con-European attitudes in people’s daily lives related to the border are explored empirically and result in final considerations of the experiences concerning the Green Line in times of Europeanization. The fieldwork in 2004/2005 and 2014/2015 and its analysis has predominantly addressed the questions of how people are affected by the Green Line as a socio-material and symbolic artefact on the micro-scale of daily life, personal feelings and identities.

Borderspaces and Borderscapes

In the past decades, borders and border studies have gained increasing attention. Even in focusing only on Europe and its de- and rebordering processes, various approaches to borders and bordered spaces enter into play (for overviews, see, for example, Haselsberger Citation2014; Laine Citation2016; Newman Citation2006; O’Dowd Citation2010; Popescu Citation2011; Rumford Citation2006; Wastl-Walter Citation2011; Wilson and Donnan Citation2012). Johnson et al. (Citation2011) make a plea for more sophisticated conceptualizations of ‘borders’ that rest not merely on territorial lines, but on the interrelated aspects of ‘place’, ‘perspective’ and ‘performance’. For the purpose of this paper on the Cypriot border, how it is experienced, ‘lived’ and framed by Europeanization, I refer to the interrelations between place, people’s perspectives and performances. Thereafter, I emphasize performativity, i.e., how exactly the border is perceived, performed and materialized in everyday practices – but also influenced by the dynamic process of Europeanization that ‘adds’ to both people’s identities and state policies. Conceptually, this article follows Parker and Vaughan-Williams (Citation2012) reflections on critical border studies with respect to performance and performativity on the one hand, and Brambilla’s (Citation2015) as well as my earlier work on the interrelations of representations and practices in borderscapes on the other (Strüver Citation2005). The objective is to focus on the ways in which borders affect people’s minds and lives on the micro-scale and the manners performed in bordered routines and identities.

In reflecting on the borderscape concept as an epistemological, ontological and methodological approach to critical border studies that liberates scholars from the ‘territorialist imperative,’ Brambilla takes up the processual notion of bordering and goes beyond the borderline to address performativity and practices. Against the background of understanding borders as material artefacts and symbolic representations and in pursuit of researching them with interactive methods, practices of ‘doing and undoing the border’ can be tackled. Brambilla (Citation2015, 26) argues that “the concept of borderscapes calls for a processual ontology that conceives reality as actively constructed, was what constitutes reality depends on human understanding and praxis” (for recent discussions of borderscape concepts with respect to practices, performances and performed identities, see also Dell’Agnese and Amilhat Szary Citation2015; Giudice and Giubilaro Citation2015; Varró Citation2016). The realities of borders as such, then, are in a constant state of coming into being. Moreover, this perspective links political and social processes to personal feelings, experiences and identities, as well as everyday practices.Footnote1

In what follows, I bring practices, identities, representations and materialities together in order to address how the border affects everyday performativities. Emanating from Butler’s theory of performativity that stresses the embodiment of practices and conjoins representations and practices together, her key concerns initially revolve around the performativity of gender identities, but have likewise been applied to the construction of national and ethnic identities (Butler Citation1993, Citation1997; Edensor Citation2002; Fortier Citation1999). Butler has defined performativity as enactment, as constant repetition of norms in practices, which reproduce or subvert public discourses. Performativity is thus constitutive of imaginations as well as of embodied identities and practices. It is both signifying and enacting; it operates through embodied practices in space that recall and reconnect with places. That is to say that the production of spaces and borders also takes place through performative acts, through acts of narration, visualization and imagination and can be conceived as borderscaping – as the practice of doing the border. Consequently, a borderscape always implies borderscaping as practices through which a border is experienced and felt, both in a symbolic and socio-material sense.

This concern for the socio-material, for the mutual constitution of humans and non-humans – as a kind of completion of the cultural turn’s concern for imaginations and representations only – forms the basic principle of Actor Network Theory (ANT) and assemblage thinking (Latour Citation2005; Law Citation2009), in which assemblages constitute relational arrangements of humans and non-humans that produce, for example, identities, territories and borders. Despite ANT’s influence on socio-material approaches, I will turn to Reckwitz' (Citation2012) praxeological perspective on affective spaces (and borders) that offers a framework for linking the analysis of emotions to space and to other material artefacts. According to him, the social is less composed of normative discourses or material structures, but of the ever-evolving network of human bodies and artefacts that both constitute material anchors of practices. Humans are culturally subjectified bodies, but since sociality is not reduced to intersubjectivity, practices rely on the interactions with artefacts. In this context, Reckwitz applies the term ‘affect’ in a very broad and interactive sense (comprising both ‘being affected’ and ‘affecting’) and indeed hardly in the biological understanding of a bodily response to an external stimulus: “there is no such thing as a pre-cultural affect. Affects are always embedded in practices which are, in turn, embedded in tacit schemes of interpretation”.Footnote2 Reckwitz thus applies a ‘weak version’ of ANT and argues that the social is (re-) produced within practices and networks between human bodies and non-human artefacts. Unlike ANT, he recognizes power relations as well as sociocultural and historical contexts. Artefacts, such as spatial borders, “are used and interpreted in specific ways, but which in turn also considerably impact on the activities they partake in” (Reckwitz Citation2012, 251). Artefacts are thus material and sociocultural objects at the same time. Being affected and affecting takes place between human subjects and non-human objects and affections emerge when human bodies move in space. Spatial arrangements are experienced in practices, but spaces as such are not affective: “affects only form when a space is practically appropriated by its users, which always activate these users’ implicit cultural schemes and routines” (Reckwitz Citation2012, 255).Footnote3

Navaro-Yashin (Citation2009) also sketches out a relational, but more ethnographic approach towards affective spaces and combines theories of affect with subjectivity. She asks whether affect emerges from the self and its subjectivity or from the surrounding environment; she furthermore claims (in a similar way as Reckwitz does) that affect is experienced by subjects in relation to objects, not emerging from the objects themselves. Subjects and objects are always entangled with each other: “the relation which people forge with objects must be studied in historical contingency and political specificity. If persons and objects are assembled in a certain manner (…) this is not because they always, already, or anyway would do so. Rather, ‘assemblages’ of subjects and objects must be read as specific in their politics and history” (Navaro-Yashin Citation2009, 9).

Regarding people’s cultural schemes and their affective experiences of spaces in practices on the one hand, and the political and historical specificity of assemblages on the other, a link to Butler’s performativity and her conception of affect is observable. That is, affects depend on socially structured feelings in which these feelings always relate to social structures of perception. It follows then, that “we can only feel and claim affect as our own on the condition that we have already been inscribed in a circuit of social affect” (Butler Citation2009, 50). Affective responsiveness, e.g., towards a border and/or ‘the other side’, constitutes an interpretative act – not of a single person, but of enacted norms and frames. In Butler’s understanding of ‘frames,’ they delimit perceptions and interpretations beyond the individual and at the same time structure how people come to know and identify people, places and borders, including the perception of oneself and others.Footnote4 Accordingly, norms do not determine perceptions and feelings, but enter into frames that structure them beyond the individual: “our affect is never merely our own: affect is, from the start, communicated from elsewhere. It disposes us to perceive the world in a certain way” (Butler Citation2009, 50). This includes the fact that feelings towards spatial artefacts as well as towards people are in part conditioned by how the world is framed.

In order to deal with the Green Line on Cyprus in a way that links place and perspective with performativities as well as sociocultural frames with subjective experiences, the border’s changing meanings and related frames with respect to their historical and political specificity will be outlined in the next section.

The Division of Cyprus and the Border’s Changing “Functions” (1964 – 1974 – 2004)

The Green Line on Cyprus separates out the two dominant Cypriot communities, i.e., Turkish and Greek Cypriots (GC). It refers to the ethno-national(-ist) tensions between the two communities as well as to social boundaries on the island that have resulted in intercommunal and sectarian violence and interethnic conflicts since independence from Britain in 1960, the establishment of a demilitarized UN Buffer Zone in 1964 and the division of the island in 1974 following massive fighting on both sides. The intercommunal violence is also seen as a colonial remnant and as an outcome of previous anticolonial violence (see Constantinou Citation2008; Demetriou Citation2007; Oktay Citation2007; Peristianis and Mavris Citation2011).

What is more, the Green Line constitutes a doubled-layered partition line cutting through the island and its capital with a ‘dead zone’ or ‘no man’s land’ of variable width in between. It was drawn as a temporary boundary on a map with a green pencil by a British Major in December 1963 (Peristianis and Mavris Citation2011, 143).Footnote5 As a result of the fighting and the division of the island, thousands of people were evicted from their homes and a population resettlement of Turkish and GC between North and South took place between 1963 and 1974. In March 1964, the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus arrived and fortified the Green Line with barbed wire fences and barricades, roadblocks, oil barrels and sandbags, particularly within Nikosia/Lefkoşa. Despite the division and the population resettlement, a Greek-sponsored coup against the GC president provoked Turkey’s military intervention on the island in July 1974 – which many GC experienced and describe as an invasion. This war resulted in a permanent division of Cyprus with a closed border as of August 1974 that more or less corresponds to the establishment of the Green Line in 1963/64. Since then, the border distinguishes between the internationally recognised RoC and the TRNC, a self-proclaimed state in 1983, internationally recognized only by Turkey. The term ‘border’ is thus applied here not so much in the sense of an internationally recognized delineation between sovereign nation-states, but as a ceasefire line and line of partition. From a GC point of view, the border is often called the “Occupation Line,” referring to the Turkish invasion and dividing the ‘free’ from the ‘occupied’ areas of the island, whereas from a Turkish Cypriot (TC) perspective, it is called the “Peace Line” that guarantees rescue and security and thus refers to the Turkish intervention in 1974 (Alpar Atun and Doratli Citation2009; Calame and Charlesworth Citation2009; see also Constantinou Citation2008; Peristianis and Mavris Citation2011; Bryant Citation2012; Papadakis Citation2018).

In contrast to the RoC as an internationally acknowledged and wealthy state from the early 1990s onwards, the TRNC has suffered from political and economic isolation and has expressed desire to be open in the sense of being internationally recognized (Bryant Citation2014). During a period of worsening of the economic environment and the standards of living (1999/2000), the TRNC was denoted an ‘open air prison’ and an ‘enclave’ disconnected from global interactions (Bryant Citation2012, Citation2014; Navaro-Yashin Citation2009, Citation2012). People then initiated public protests against their political leadership that gained enormously in importance. Indeed, shortly thereafter in December 2002, nearly half of all Turkish Cypriots participated in the related gatherings. The protests were redirected towards social justice and global integration in general and Cypriot unification and joint EU accession in particular (Agapiou-Josephides Citation2012; Karatsioli Citation2014). Due to these ongoing protests, border checkpoints were opened by the authorities of the TRNC in April 2003 for the first time since 1974. This was also seen as a rebellious act against the GC EU-negotiations about entering the EU without the island’s northern part. About two million Cypriots primarily from the north, proceeded to cross the Green Line between May and December 2003. This was accompanied by an initial period of euphoria and enhanced Europhile trends (Bryant Citation2016). Meanwhile, the situation between the south and the north has improved greatly since 2003/2004 such that the

“opening of the gates to facilitate reciprocal movement did not only symbolize the coming together of people and groups, who were previously prevented from being in contact with each other, but it also somehow changed the perception of the border, or borderland area, from that of a barrier to an interface (…). Changing peoples’ perceptions is generally a ‘bottom-up, rather than a top-down process'” (Alpar Atun and Doratli Citation2009, 126).

However, this changed again only a year later. Partly as a result of the rebellion, negotiations about reunification were set-up once again and ultimately led to a UN referendum (known as the Annan Plan), aimed at uniting the island by way of a bi-communal federation in April 2004. While 65% of the Turkish Cypriots accepted the Annan Plan and thus voted in favour of reunification, 74% of the GC voted against it. One week later, on 1 May 2004, the RoC entered the EU without the TRNC - although Turkish Cypriots technically became EU-citizens and their territory is now part of the EU. Despite the original Turkish Cypriot EU-scepticism, the majority had supported the Annan-Plan on the one hand, because they were aware of socioeconomic benefits which the reunification and the EU accession of a united island would prevent. The GC, on the other hand, had originally been enthusiastic about unification, but voted against it for security reasons (Kyris Citation2012).

The Green Line dividing Cyprus thus de jure ceased to exist as of the RoC’s single EU-accession in 2004. De facto, it is an external EU border between the RoC and the TRNC, since only the RoC became a full EU member while the territory of the entire island constitutes part of the EU; EU law furthermore includes a provision that the acquis communitaire is officially suspended in the north. Since the RoC claims both Greek and Turkish Cypriots as its citizens, Turkish Cypriots are able to claim both RoC identity cards and EU passports and other advantages linked to these circumstances (e.g. international travel freedom). Despite the failed attempt at reunification before EU accession, Turkish Cypriot citizens (not Turkish settlers and Turkish soldiers in the TRNCFootnote6) are therefore technically citizens of the RoC because of their historical citizenship before 1974 and their territorial affiliation in the meantime. After the RoC became an EU member in May 2004, nearly half of the Turkish Cypriots did acquire RoC identity cards and about half of them also EU passports (Bryant Citation2014).

The UN Buffer Zone as a demarcation line is therefore merely a national border in a very broad sense since it is neither an internationally recognized state border nor an external border of the European Union. In theory, free movement of goods and people is possible, but in practice, border controls and limitations remain in place for both people and goods. The Green Line thus continues to act as a border across the island. This ‘acting’ of the border includes its power to affect people and will be addressed empirically below.

With the application for EU membership in 1990, the role of the EU had gained importance for Cyprus and has likewise raised expectations with respect to solving the ‘Cyprus problem’, i.e., for overcoming the division and establishing a bi-zonal and bi-communal federal Cypriot state without the UN Buffer Zone as a barrier. What is more, the unexpected opening of the border allowing Turkish and Greek Cypriots to cross to the respective other side as of 2003 had been unimaginable for nearly 30 years and prompted a renewed debate about a common future of Cyprus, as well as about pro-European attitude in popular discourse and everyday life. This opening and the crossings of the border make reference thus to a normalization of people’s relations across the border (Karatsioli Citation2014). However, the failed referendum only a year later replaced experimentation with normalization, followed by disillusion. Indeed, in northern Cyprus, new tendencies of nationalism emerged and the border was (once again) acknowledged in a ‘positive’ sense, as protecting but also as enabling. That is, because of the Turkish Cypriots’ positive vote for reunification, an increasing international openness towards the TRNC was observable: “since the failed referendum, the EU and international organizations [such as UNDP and USAID] have attempted to implement a strategy of ‘engagement without recognition’” (Bryant Citation2014, 135; see also Kyris Citation2012) – and have improved living conditions in terms of housing, consumer goods, domestic and international transportation, etc.. At the same time, because of the increasing significance of the EU to the TRNC in terms of economic, social and political development and increased funding activities by Turkey, the RoC has blocked the implementation of a direct trade agreement between the TC business sector and EU member states with a veto, and has thus so far reproduced the community’s economic isolation within Europe.Footnote7

Europeanization and Economic Crises

The ceasefire line dividing Cyprus acted as a closed border between 1974 and 2003/2004. As a result, international trade and travel to and from the north was limited to Turkey. In the period immediately preceding the war and the division of the island, the north had been the part that provided more than 70% of all economic performance (especially in tourism and agriculture). These economic structures collapsed after 1974 due to the non-recognition of the TRNC as a (partial) state and the economic embargo, and have ultimately increased the Turkish Cypriots’ dependence on Turkey (Bryant and Yakinthou Citation2012). In the southern part, however, a rapid development of new industries and infrastructures took place after 1974, including sun-and-sea tourism (Sharpley Citation2001).

Since the economy of the south was among the healthiest in Europe since the 1990s, the EU accession of the RoC based on territorial affiliation was especially relevant for the northern part. Due to the growing international engagement and partial relaxation of the economic blockades, as well as due to EU and UNDP funding and broad infrastructure programmes supported by the TC and the Turkish governments, socioeconomic prosperity is now seen to be growing while the living conditions of TCs have likewise improved (Karatsioli Citation2014; Kyris Citation2012). Since the opening of the border in 2003/2004 and the related international media attention, the development of natural, cultural and casino tourism in the TNRC and a general economic recovery are observable. The urban landscapes (and roadscapes) in the island’s north rapidly improved between 2004 and 2014, and both housing and shopping facilities improved in standard (Karatsioli Citation2014; Kyris Citation2012; see also Theophanus, Tirkides, and Pelagidis Citation2008; Giritli, Jenkins, and Ugural Citation2014; Turkish Cypriot Chamber of Commerce Citation2017).

“At the same time, pirated DVD and CD shops are everywhere, while taxes on hotel casinos and brothel areas outside the main cities are important sources of state revenue. As a result, Turkish Cypriots recognize that they are incorporated in the global economy as passive consumers rather than as producers, that their marginal position leaves them consuming originals but producing semblances and fakes” (Bryant Citation2014, 136).

The financial support of the TRNC by Turkey was and remains highly relevant (Bryant Citation2014). Linked to their dependency on Turkey and with Turkey’s economy being part of the Asian crisis, the Turkish Cypriots had to endure a major economic crisis in 1999/2000, while Turkey introduced austerity measures to the island’s northern part. Meanwhile, due to the failed reunification, international non-recognition and isolation, the TRNC was neither appreciably affected by the international financial crisis in 2008, nor by the domestic banking crisis in the RoC in 2011. Since the RoC still impedes cross-border trade for goods from the North, Turkish Cypriots still rely heavily on Turkey as their main economic partner and have to establish international trade agreements with the TRNC as a kind of Turkish autonomous province. Yet, it became obvious that the TRNC’s dependency on Turkey was transformed from one based on ethnic relations to one determined by economic relations (Karatsioli Citation2014).

When the RoC joined the European Union in 2004, it was one of the most prosperous economies in comparison to the other (old and new) member states. The economy of the RoC was (and remains) dominated by the service sector, especially tourism and financial services two sectors that depend on (geo-) political stability across Europe and the Middle East. The country used to offer an investment-friendly environment with a very low corporation tax rate (of 10%) and an above-average interest rate (of 6–7%). This resulted in a large and ever-growing banking sector that contributed significantly to employment and to the general well-being of the state and its people (Iordanidou and Samaras Citation2014; Orphanides Citation2014).

After the elections in February 2008, the left (communist) party AKEL came into power in the RoC. On the basis of the very healthy national economy on the one hand, and the positive effects of the opened border on the other, the new government’s political objectives were focused on resuming peace talks and plans for establishing a bi-zonal federation. However, because of the global financial crisis, the Eurozone crisis and their consequences, along with growing public expenditures and national economic recession, the government had lost control over its financing in summer 2011. Moreover, in July 2011, the country’s largest power station was destructed after an accidental explosion. This had immediate (and long-term) effects on production and service industries due to power cuts and power saving measures across the southern part of the island. The national economic crisis threw the RoC into recession and resulted in an increasing unemployment rate (from 3,7% in 2008 to 11,9% in 2012 and 16,1% in 2014,Footnote8 see also the decline of GDP since 2011 in ). Different from political measures in, for example, Greek, Portugal and Spain, the response of the RoC government was not initially based on austerity programmes, but on increasing social spending and caring for its people (Orphanides Citation2014). A reversal of this approach, however, was introduced after the Eurozone granted financial assistance in March 2013 and the resultant austerity measures of the bail-out package included cuts in social benefits and an increase of valued added tax, i.e., real salaries and purchasing power decreased (Iordanidou and Samaras Citation2014).

While in 2008/09 the government of the RoC neglected the (international) financial crises due to its focus on domestic politics regarding rapprochement with the northern part of the island, the so-called ‘Cyprus Issue’ was displaced from the political agenda from 2011 onwards with respect to the domestic financial crisis in the RoC (Katsourides Citation2014). Iordanidou and Samaras (Citation2014) argue that the financial crisis in Cyprus has displaced the international image of Cyprus as a divided island suffering from partition to one suffering from financial mismanagement and economic recession. At the same time, references to the island’s crisis in the summer of 1974 were employed at the beginning of the RoC’s economic crisis, a period characterised by both hardship and resilience: “Cypriots draw on spirit of ’74 to see them through Euro crisis” (Theodoulou Citation2013; see also Orphanides Citation2014).

In addressing the impact of austerity on everyday life in the RoC, Bryant (Citation2016) emphasizes increasing social suffering related to material poverty for the first time since the 1980s. She points out that the opening of the border in 2003 and the preparation for the referendum on reunification in 2004 have resulted in euphoria and anxieties on both parts of the island at the same time, mainly because of the uncertainty of the future. After the referendum, the EU accession of the RoC, and the economic crisis in the island’s southern part, many GC now describe the current economic crisis as a struggle for existence, “while anxieties around the opening and referendum recognized that these events would reconstitute the everyday” (Bryant Citation2016, 23). Taking up this notion of daily life, the next section draws on everyday performative acts of borderscaping which are influenced by the Turkish-Greek antagonism and the process of Europeanization.

Europeanization and Everyday Life along and across the Border

Agapiou-Josephides (Citation2012, Citation2016) argues that the pro- and con-EU-articulations on Cyprus are (still) linked to the island’s political problems and to the dividing border. The referendum of 2004, then, is seen as the most significant turning point both in party and in popular Euroscepticism. Subsequently, in 2014/15, not only EU-indifferences, but EU-criticism and EU-disillusion were widespread in both parts of the island and across various political attitudes.

The preparation for Cyprus’ EU accession was internationally as well as nationally linked to aspirations for unification and to EU-phoria on both sides of the Green Line. Especially for the people in the TRNC, it appeared to be a fortunate solution for political as well as economic problems on the national scale, notably for those linked to the non-recognition and isolation of the TRNC. For many Turkish Cypriots, the first extensive disappointment was thus the Greek Cypriots’ vote against the Annan-Plan for reunification in April 2004. After 10 years, their disillusion with the EU became even more obvious; it is mostly based on the EU’s reluctance to officially recognize the TRNC and establish formal economic and political relations. In the Cypriot borderscapes, ‘Europe’ thus seems to be hardly an issue in day-to-day-concerns, but is rather an official political issue. Nevertheless, the changes related to the process of Europeanization affect people’s lives. Adopting the conceptual considerations on performative practices of doing and undoing the border, as described before, empirical explorations are presented in pursuit of understanding how sociocultural and economic aspects are reshaped in both parts of the island by Europeanization as well as how personal experiences and feelings converge with discursive frames.

On the one hand, the Green Line nowadays is rather a resource than a barrier. The UN Buffer Zone was considered a security necessity for a long time, but post-2004, it has become a line of opportunity, e.g., for tourism. The RoC, for example, is marketing Nikosia as the “last divided capital of the world” and yet or on account of this, the city maps ‘end’ at the border (as do the Lefkoşa maps).Footnote9 However, focusing on Cypriots’ perceptions and drawing on fieldwork in May 2004 (immediately after the referendum and the RoC’s EU accession), April 2005 and again in May 2014 (during the week of European elections) and September 2015, the emphasis is put in this study on the Green Line in Nikosia/Lefkoşa and its transformed meanings during the last decade, including its representation as political, cultural and economic division that affects (ethno-) national identities and frames everyday practices.

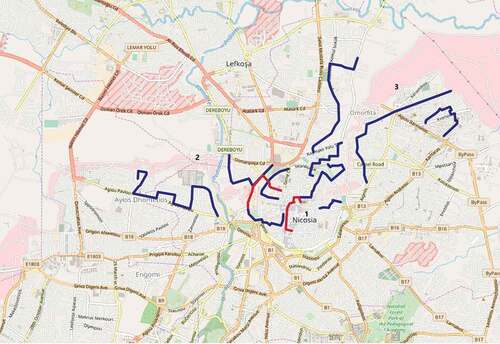

The empirical investigation relies on an ethnographic approach towards affective borderspaces and rests on the assumption that affect is experienced by subjects in relation to (spatial) objects and that these experiences are framed by historical contingency and political specificity beyond the individual. The fieldwork of the research presented comprises more than 50 narrative interviews with Turkish and Greek Cypriots, conducted in English in the streets of Nikosia/Lefkoşa in 2004/2005 and 2014/2015.Footnote10 In 2014 and 2015, most of them were performed as interactive walking interviews, focusing on people’s perceptions of the border and thus on how people are experiencing the border while ‘walking and talking’ (see ).

Figure 2. Map with dominant routes of “walk and talk” interviews in 2014/2015 (dotted lines indicating cross-border walks; the numbers refer to the pictures’ respective location).

Ethnographic approaches such as walking interviews are less focused on the interviewer than on the socio-spatial experiences of the interviewees and on the narratives related to spatial artefacts encountered (or remembered) while walking (Evans and Jones Citation2011; for a discussion of this method for border studies, see Varró Citation2016; Papadakis Citation2018). These interviews allowed me to get more profound insights and to understand people’s personal histories, feelings, anxieties, etc., attached to the border and local spaces, even if the verbal communication was sometimes poor. The interviewees were mostly approached and asked to participate in the research in public places of the inner city. Their narrations were partly complemented by sketch-maps and snapshots.

Since the TRNC is highly protective of the border and tries to block investigations taking place within the buffer zone of Lefkoşa (see ), some of the interviewees tended to exhibit a protective attitude towards me while walking. In Nikosia, however, the walks were rather (too) uneventful since even the UN soldiers display boredom and lack of interest in guarding the border or people walking (too) close to it. In the northeastern part of Nikosia, e.g., one could easily end up walking into the buffer zone (see ).

The unexpected opening of the border in April 2003 also opened up the possibility for both Turkish and GC to cross the border in order to visit old friends and former homes, or out of curiosity about the ‘other side’. In interviewing border crossers in 2004, 2014 and 2015 as well as people who live in Nikosia/Lefkoşa, but do not cross (in 2004, 2005 and 2014) with respect to their emotions attached to – or affected by – the border, some dominant findings will be summarized along five different aspects: the border as a generator of economic resources (1), identity issues (2), regarding the perceived impact of Europeanization (3), emotional experiences of crossing the border (4) and the decision to ignore the respective other side (5). These aspects are illustrated by anchor quotes, relying on codes that were inductively assigned when analysing the interview-material in MAXQDA (transcribed from audio recordings; for this type of qualitative analysis, see Mayring Citation2014). The anchor quotes thus refer not only to individual expressions, but to socio-culturally structured feelings and perceptions of the border and towards (or against) Europeanization.Footnote11

(1) There is first of all the aspect that the border is experienced as anindividual economic resource, i.e., that ‘everyday life gets better andcheaper’. One GC (36m; I 7/2015) states:

“We do need the border: I cross nearly on a daily basis, to do shopping, to eat out and yes, not only for cheaper, but better beaches, better gambling, better sex (…). Sometimes, I cross in Ledra Street just to get a much cheaper cup of coffee.”

But also on a national level and from a TC perspective,

“[t]hings have changed since ’74, and then again since 2004. Not in unification-terms, but well, in terms of our wellbeing and the entire situation, economically. (…) This also affects me and my family, economically” (TC 32f, I 9/2014).

(2) However, related to formal and felt identity issues, numerousambivalences and concerns are expressed both by TCs and GCs, forexample:

“I am irritated, again and again, that I do have to show my identity [card], in my own land!” (GC, age 52m; I 6/2015) as well as: “Crossing the line, at the checkpoint or even as a really open border, if that will ever happen, does not feel right, it feels like accepting the Greek dominance” (TC 27m; I 12/2015).

Yet a year after the opening of the border and immediately after the failed referendum, one young GC (24m) brought up his excitement about the changes:

“This is really exciting! And I don’t mind the Turkish Cypriots, hey, they are Cypriots! But there is no place for Turkish settlers and the Turkish Army” (I 22/2004).

After 10 yearsr, however, a TC makes reference to the buffer zone as part of his identity,

“it defines who we are and where we belong. Every time you cross [to go to work], you get a sense of your identity – let there be a European Union or not (…). I cross five times a week and the crossing is not simply travel back and forth, but part of my identity. (…) Well…, my identity is officially tied to the [new] passport, but it remains a Turkish Cypriot one. (…) I need both identities, the new one in order to go to work …. And for travelling, travelling abroad. But I definitely also need the ‘me’-identity, simply for being me!” (40m; I 7/2014; emphases by the interviewee).

Interestingly, some people seem to negotiate with themselves between these positions towards the border that they develop on an individual level, against socially structured feelings and normative frames, e.g., using economic advantages related to the border-crossing, while at the same time, however, being critical of the partition and/or the ‘other side’. Another GC (38m) reveals this much as follows:

“Although I do cross on a regular basis [to eat out much cheaper], I know… I know that this is me, recognizing the division as legal – and as permanent” (I 10/2015).

(3) Regarding the impact of Europeanization, a young TC made very clear,

“we are not second class any longer, we are now emancipated and have equal rights, things are getting normal (…). We have better education, better passports, better work … we can work abroad, legally!” (28m, I 3/2014)

and a GC, being only a bit older, points out that

“a unified Cyprus will be growing economically on both sides, the last ten years give evidence for this. The EU of course has made this progress possible. But who knows, without the referendum being tied to our accession, we might have been better of politically, I mean in terms of true acceptance?” (GC 42m, I 19/2014).

In 2014/15, many TC and GC cross the border on a daily basis to get to work, access cheaper or better shopping, eat out and thus do ‘use’ the border as an economic resource at an individual level. Yet while doing research on non-border-crossing practices in Nikosia/Lefkoşa in 2005 and 2014, I often came across phenomena that are not related to the border’s economic advantages, but refer to highly (4) emotional experiences and the affective entanglements of people and materialities:

A female GC aged 63, for example, told me when interviewed in 2004:

“Last year, I crossed out of curiosity and yes …, I will never again – I did not feel at home at all [in my former home close to Famagusta], I felt the invasion again, I felt dizzy, I felt physically sick. This started right at the checkpoint, but got worse when we went east, toward what was our home” (I 7/2004).

A TC reports similar experiences:

“We were feeling as visitors to our [former] home! We never had any problems back then, now going south means feeling insecure; there is so much hate. When I go to the other side [in Nikosia], I never feel safe. When we visit my family’s place [Arkamas] … well, that is like a second displacement for me. (…) I hardly recognize anything there, and what I do recognize from being a child … I feel estranged, all the things don’t relate to me” (50f; I 2/2014).

(5) In addition, the analysis with respect to EU trajectories likewise discloses ignorance towards the respective other side:

“Obviously, I am curious, but I have my doubts…, I now have the chance, even the legal right to cross to the other side, but just thinking about it makes me mad [angry]” (GC, 67m, I 5/2005).

And nearly 10 years later, another GC stated:

“I never visit the occupied part. We seem to be paying for everything [for the Turkish Cypriots] which is not justified, not economically, not morally. So I don’t want to spend a single Euro over there. For me, the other side does not exit” (65m, I 12/2014).

The border thus functions as individual economic opportunity for many Greek and Turkish Cypriots in everyday life. That is, it is an economic resource that is evaluated quite similarly as positive by both the Turkish and GC interviewed (2014/15) after more than 10 years of having the possibility to cross over. Yet, for both groups of people, these positive outcomes are ambivalent as they also comprise the acknowledgement of the Green Line as a line of division, including its causes and effects. The dividing border constitutes part of people’s identities (on both sides) - whether by crossing it or not – and this influence on one’s identity seems to be much more powerful than in the years before its opening. Consequently, the (perceived) impact of Europeanization appears to affect people because of the open border. At the same time and with reference to pro- and con-EU-attitudes, most Turkish Cypriots cursorily consider themselves Europhile for individual advantages and “for being somewhat part of the EU” (TC, 32m, I 3/2015), but not, however, for political or sociocultural reasons. Yet, whereas many GC in 2004/2005 have emphasized the “overall positive political effects for the entire island” (GC, 47m, I 1/2005), many of them proceeded to criticize economic drawbacks on a national scale related to their EU membership in 2014/2015.

Nevertheless, the main objective of this analysis was not to compare Turkish and Greek Cypriots’ experiences and narratives, but to explore how people are affected by the Green Line as a socio-material and symbolic artefact on the micro-scale of personal feelings, identities and daily practices – and whether or how this changed between 2004/05 and 2014/5. These findings can be tied back to Navaro-Yashin’s and Reckwitz’ argument that affect is experienced by people in relation to the border(-space) and is historically contingent. Moreover, they also illustrate the ways in which the borderspaces in Nikosia/Lefkoşa are performed as borderscapes.

Outlook: Cypriot Borderscapes

Coming back to the general question of how the Green Line in Nikosia/Lefkoşa is experienced and framed by Europeanization, the significance of the EU had initially changed towards increasingly Europhile notions since the RoC’s application for EU membership in 1990. Specifically, after the opening of border checkpoints in April 2003, a remarkable period of widespread EU-phoria ensued for about a year in both parts of the island – pervading everyday life, political and popular discourses. For many Turkish Cypriots, Cyprus’ EU accession was linked to the prospects of reunification and thus to overcoming political and economic isolation. However, 10 years later, their disillusion with the EU in political terms was widespread; yet their individual advantages (including EU passports, cross-border work and remittances sent from abroad) were acknowledged and appreciated. Skip to the present, and many GC now primarily express Euroscepticism in terms of economic well-being, coupled with political indifference towards the EU. This was particularly obvious during the week of the European elections in May 2014.

In order to address performative practices of bordered and nationalized daily routines beyond the ‘territorialist imperative’ and in researching the practices of ‘doing and undoing the border’ as borderscaping, this paper has approached the Green Line as manifestation of the unresolved conflict between Greek and Turkish Cypriots and their respective national, sociocultural and spatial identities. In that pursuit, it has also highlighted the border as a place where Europeanization becomes an issue, where pro- and con-EU-attitudes symbolically come together. These attitudes emerge from economic and political issues, as well as from spatial practices such as whether or not to cross the border. These practices, however, do not rely on individual perceptions only, but likewise on collective historical remembrances and discursive frames.

The theoretical and empirical considerations on how the border in Nikosia/Lefkoşa is performed in everyday life and in people’s identities, and, furthermore, how these performative enactments refer to borderscapes as affective spaces of ‘historical contingency and political specificity’, including the changing perspectives on Europeanization, ultimately illuminate how perceptions of the EU and pro- and con-EU-attitudes seep into experiences of the border. It follows, then, that rational or partial (because economic) explanations for pro and con EU-attitudes are virtually impossible, since they depend on historically contingent and politically specific frames on the one hand, and on affective experiences in spatial practices on the other. This includes the phenomenon of pro- and con-EU attitudes potentially changing in rapid succession. Indeed, they are subject to the full scope of emotional attachments and political events.Footnote12 The empirical analysis presented in this paper has illustrated how these frames are practiced and manifested, including and emphasizing the emotional experiences of the Cypriot borderscapes both locally in Nikosia/Lefkoşa and nationally, as well as in relation to Europeanization.

Regarding the background of her own research on Cyprus, Bryant (Citation2012, 357) presumes that “while the border as that which contains the “other” has been shaken [since 2004], the border as frame of suffering remains peculiarly intact.” She also refers to Butler’s (Citation2009) notion of ‘normative frames’ in general and to banal and affective local nationalism in particular, e.g., to representations such as newly emerging TC flags and monuments in the aftermath of the opening of the border in 2003 and a ‘flag mania’ and rising local nationalism after the failed referendum in 2004. A similar point emphasizing normative frames as affecting people’s perceptions and practices is made by Wetherell et al. (Citation2015), that affective (national) histories “grab people”. She stresses that affective practices are figurations where people’s practices become entangled with meanings and with other social and material figurations (Wetherell Citation2012, see also Merriman and Jones Citation2016). The affective is neither detached from the discursive, nor from the spatial; rather, it is the discursive, e.g., ‘banal nationalism’, that adds power to affects and their circulation in space.Footnote13 The borderscapes in Nikosia/Lefkoşa are then embodied experiences of place and space in everyday live, and likewise of normative frames that are (re-) produced by the unresolved conflict between Greek and Turkish Cypriots and by the Green Line as the material and symbolic manifestation of this conflict.

Notes

1. See also Mol and Law (Citation2005) for considerations on the materialities and ‘practical enactments’ of borders.

2. He is therefore critical of non-representational theory’s approach to affect, see Thrift (Citation2008).

3. See also Varró (Citation2016) on a ‘practice turn’ in border studies; and see O’Dowd (Citation2010) and Paasi (Citation2009) on affect and emotions mobilized by borders – and borders relying on historical contingency and related power relations as well as to sociocultural practices.

4. This also refers to Laine’s argument to understand borders as multiscalar and dynamic processes with various symbolic and material forms and that research on their de- and reconstruction needs to address different levels, comprising the discursive and the institutional sphere, but also the level of everyday practices. Moreover, Laine (Citation2016) also stresses that the collective memory of borders is embodied in daily routines and experiences/perceptions and thus remains present in changing landscapes of (European) policies.

5. There are doubts about this narrative on the origin of the Green Line. However, since the term is widely used and recognized (in daily language, academic research and EU documents on Cyprus), this paper also applies the term (see also Papadakis Citation2018).

6. Due to the non-recognition of the TRNC internationally, exact numbers regarding the population and their origins are impossible. However, the shares are approximately 60% Turkish Cypriots, 25% settlers and workers from Turkey and 10% Turkish soldiers (Hatay Citation2017).

7. The EU-funding is documented in the annual EC reports (https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/annual-reports-implementation-aid-regulation-turkish-cypriot-community_en) for the most recent, see http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52017DC0372. See also Theophanus, Tirkides, and Pelagidis (Citation2008) and the very recent evaluation by the Turkish Cypriot Chamber of Commerce (Citation2017).

8. For the development of the unemployment rate, see: Statistical Data Warehouse Cyprus. 2016. Unemployment rate 1997–2016. Accessed October 4, 2017. http://sdw.ecb.europa.eu/quickview.do?SERIES_KEY=139.AME.A.CYP.1.0.0.0.ZUTN.

9. However, the ‘visually demoralising’ Buffer Zone in Nikosia/Lefkoşa is now starting to change on both sides due to rehabilitation measures and also due to increasing cross-border tourism.

10. While in 2004/2005, English was reduced to basic communication with most of the Turkish Cypriots, it was much easier to speak with older Greek Cypriot people (as a colonial inheritance). In 2014/15, however, English was much more common regardless of age in both parts of the island. The analysis was done using the original English transcriptions.

11. The quotes refer to the original interviews according to the following scheme: Turkish or Greek Cypriot (TC/GC), age, gender, number of interview in the respective year.

12. O’Dowd (Citation2010) and Paasi (Citation2009) have also pointed out that history is very important and that emotions mobilised by borders rely on their historical contingency and related power relations as well as social practices. Moreover, see Anderson (Citation2017) on BREXIT-border issues on the Irish island and their entanglements with pro- and con-EU-attitudes, national(ist) emotions, identities and practices.

13. With an explicit focus on geopolitics, Laketa (Citation2016) has also addressed affect and emotions in a divided city with the case of invisible border between Muslims and Catholics in post-conflict Mostar.

References

- Agapiou-Josephides, K. 2012. Changing patterns of Euroscepticism in Cyprus: European discourse in a divided polity and society. In Euroscepticism in Southern Europe, ed. S. Verney, 159–84. London: Routledge.

- Agapiou-Josephides, K. 2016. Cyprus. In Routledge handbook of European elections, ed. D. Viola, 448–68. London: Routledge.

- Alpar Atun, R., and N. Doratli. 2009. Walls in cities: A conceptual approach to the walls of Nicosia. Geopolitics 14 (1):108–34. doi:10.1080/14650040802578682.

- Anderson, J. 2017. A solution to the problem of a ‘hard’ irish border: The island’s post-brexit borders. Accessed December 7, 2017. http://crossborder.ie/site2015/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/REVISED-Solution-Irish-Border-Problem-pdf-2-July-.pdf.

- Brambilla, C. 2015. Exploring the critical potential of the borderscapes concept. Geopolitics 20 (1):14–34. doi:10.1080/14650045.2014.884561.

- Bryant, R. 2012. Partitions of memory: Wounds and witnessing in cyprus. Comparative Studies in Society and History 54 (2):332–60. doi:10.1017/S0010417512000060.

- Bryant, R. 2014. Living with liminality: De facto states on the threshold of the global. The Brown Journal of World Affairs 20 (2):125–43.

- Bryant, R. 2016. On critical times: Return, repetition, and the uncanny present. History and Anthropology 27 (1):19–31. doi:10.1080/02757206.2015.1114481.

- Bryant, R., and C. Yakinthou. 2012. Viewing Turkey from North Cyprus today. Istanbul: Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation. Accessed October 4, 2017. http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/zypern/10617.pdf.

- Butler, J. 1993. Bodies that matter. On the discursive limits of ‘Sex’. London: Routledge.

- Butler, J. 1997. Excitable speech. A politics of the performative. London: Routledge.

- Butler, J. 2009. Frames of war. London: Verso.

- Calame, J., and E. Charlesworth. 2009. Divided cities. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Constantinou, C. 2008. On the Cypriot states of exception. International Political Sociology 2 (2):145–64. doi:10.1111/j.1749-5687.2008.00041.x.

- Dell’Agnese, E., and A.-L. Amilhat Szary. 2015. Borderscapes: From border landscapes to border aesthetics. Geopolitics 20 (1):4–13. doi:10.1080/14650045.2015.1014284.

- Demetriou, O. 2007. To cross or not to cross? Subjectivization and the absent state in Cyprus. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 13 (4):987–1006. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2007.00468.x.

- Edensor, T. 2002. National identity, popular culture and everyday life. Oxford: Berg.

- Evans, J., and P. Jones. 2011. The walking interview: Methodology, mobility and place. Applied Geography 31 (2):849–58. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.09.005.

- Fortier, A. 1999. Re-membering places and the performance of belonging(s). Theory, Culture and Society 16 (2):41–62. doi:10.1177/02632769922050548.

- Giritli, N., G. P. Jenkins, and S. Ugural. 2014. Economic repercussions of opening the border to labour movements between North and South Cyprus. Economic Research 27 (1):729–39. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2014.975920.

- Giudice, C., and C. Giubilaro. 2015. Re-imagining the border: Border art as a space of critical imagination and creative resistance. Geopolitics 20 (1):79–94. doi:10.1080/14650045.2014.896791.

- Haselsberger, B. 2014. Decoding borders. Appreciating border impacts on space and people. Planning Theory & Practice 15 (4):505–26. doi:10.1080/14649357.2014.963652.

- Hatay, M. 2017. Population and politics in north Cyprus: An overview of the ethno-demography of north Cyprus in the light of the 2011 census. PRIO Cyprus Centre Report, 2. Nicosia: PRIO Cyprus Centre and Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

- Iordanidou, S., and A. Samaras. 2014. Financial Crisis in the Republic of Cyprus. Javnost – The Public 21 (4):63–76. doi:10.1080/13183222.2014.11077103.

- Johnson, C., R. Jones, A. Paasi, L. Amoore, A. Mountz, M. Salter, and C. Rumford. 2011. Interventions on rethinking ‘the border’ in border studies. Political Geography 30 (2):61–69. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.01.002.

- Karatsioli, B. 2014. What kind of state are we in when we start to think of the state? Cyprus in Crisis and prospects for reunification. The Cyprus Review 26 (1):147–67.

- Katsourides, Y. 2014. The comeback of the right in crisis-ridden Cyprus: The 2013 presidential elections. South European Society and Politics 19 (1):51–70. doi:10.1080/13608746.2013.861261.

- Kyris, G. 2012. The European Union and the Cyprus problem. Eastern Journal of European Studies 3 (1):87–99.

- Laine, J. P. 2016. The multiscalar production of borders. Geopolitics 21 (3):465–82. doi:10.1080/14650045.2016.1195132.

- Laketa, S. 2016. Geopolitics of affect and emotions in a post-conflict City. Geopolitics 21 (3):661–85. doi:10.1080/14650045.2016.1141765.

- Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the social. An introduction to actor network theory. Oxford: UP.

- Law, J. 2009. Actor-network theory and material semiotics. In The new Blackwell companion to social theory, ed. B. Turner, 141–58. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Mayring, P. 2014. Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Accessed October 4, 2017. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173.

- Merriman, P., and R. Jones. 2016. Nations, materialities and affects. Progress in Human Geography 41 (5):600–17. doi:10.1177/0309132516649453.

- Mol, A., and J. Law. 2005. Boundary variations: An introduction. Environment and Planning D: Society & Space 23 (5):637–42. doi:10.1068/d350t.

- Navaro-Yashin, Y. 2009. Affective spaces, melancholic objects: Ruination and the production of anthropological knowledge. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 15 (1):1–18. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2008.01527.x.

- Navaro-Yashin, Y. 2012. The make-believe space: Affective geography in a post-war polity. London: Duke UP.

- Newman, D. 2006. The lines that continue to separate us: Borders in our `borderless’ world´. Progress in Human Geography 30 (2):143–61. doi:10.1191/0309132506ph599xx.

- O’Dowd, L. 2010. From a ‘borderless world’ to a ‘world of borders’: ‘Bringing history back in’. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (6):1031–50. doi:10.1068/d2009.

- Oktay, D. 2007. An analysis and review of the divided city of Nicosia, Cyprus and new perspectives. Geography (Sheffield, England) 92 (3):231–47.

- Orphanides, A. 2014. What happened in Cyprus? The economic consequences of the last communist government, Europe. LSE Financial Markets Group Special Paper Series 232. Accessed October 4, 2017. http://www.lse.ac.uk/fmg/dp/specialPapers/PDF/SP232-Final.pdf.

- Paasi, A. 2009. Bounded spaces in a ‘borderless world’: Border studies, power and the anatomy of territory. Journal of Power 2 (2):213–34. doi:10.1080/17540290903064275.

- Papadakis, Y. 2018. Borders, paradox and power. Ethnic and Racial Studies 41 (2):285–302. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1344720.

- Parker, N., and N. Vaughan-Williams. 2012. critical border studies: Broadening and deepening the ‘lines in the sand’ Agenda. Geopolitics 17 (4):727–33. doi:10.1080/14650045.2012.706111.

- Peristianis, N., and J. Mavris. 2011. The ‘green line’ of Cyprus: A contested boundary in flux. In The ashgate research companion to border studies, ed. D. Wastl-Walter, 143–70. 1st ed. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Popescu, G. 2011. Bordering and ordering the twenty-first century: Understanding borders. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Reckwitz, A. 2012. Affective spaces. A praxeological outlook. Rethinking History 16 (2):241–58. doi:10.1080/13642529.2012.681193.

- Rumford, C. 2006. Theorizing borders. European Journal of Social Theory 9 (2):155–69. doi:10.1177/1368431006063330.

- Sharpley, R. 2001. Tourism in Cyprus. Tourism Geographies 3 (1):64–86. doi:10.1080/14616680010008711.

- Strüver, A. 2005. Spheres of transnationalism within the European Union: On open doors, thresholds and drawbridges along the Dutch-German border. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 31 (2):323–43. doi:10.1080/1369183042000339954.

- Theodoulou, M. 2013. Cypriots draw on spirit of ’74 to see them through Euro crisis. In The national, Abu Dhabi, 1. May. https://www.thenational.ae/international

- Theophanus, A., Y. Tirkides, and T. Pelagidis. 2008. An anatomy of the economy of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus?. Journal of Modern Hellenism 25–26:157–88.

- Thrift, N. 2008. Non-representational theory: Space, politics, affect. London: Routledge.

- Turkish Cypriot Chamber of Commerce. 2017. Northern Cyprus Economy Competitiveness Report 2016–2017. Accessed October 4, 2017. http://www.ktto.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/KTTO2016-2017-eng.pdf.

- Varró, K. 2016. Recognising the emerging transnational spaces and subjectivities of cross-border cooperation: Towards a research agenda. Geopolitics 21 (1):171–94. doi:10.1080/14650045.2015.1094462.

- Wastl-Walter, D., ed. 2011. The Ashgate research companion to border studies. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Wetherell, M. 2012. Affect and emotions. A new social science understanding. London: Sage.

- Wetherell, M., T. McCreanor, A. McConville, H. Barnes, and J. le Grice. 2015. Settling space and covering the nation: Some conceptual considerations in analysing affect and discourse. Emotion, Space and Society 16:56–64. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2015.07.005.

- Wilson, T., and H. Donnan, ed. 2012. A companion to border studies. Chichester: Wiley.