ABSTRACT

In this article we argue that the EU suffers from autoimmunity: a self-harming protection strategy. Drawing on Derrida’s political understanding of autoimmunity, we contend that the root of this malfunction lies in the EU’s own b/ordering and othering policies, which are intended to immunise the foundational ethos of the EU. For this purpose, we dissect the EU border regime into three linked b/ordering mechanisms: the pre-borders of paper documents that regulate from afar the mobility of the people from visa-obliged countries; the actual land borders often consisting of iron gates and fences regulating mobility on the spot; and the post-border in the form of waiting/detention camps that segregate and enclose the undocumented migrants after entry. We make clear how this discriminatory b/ordering and othering regime has led to a recurrent drawing of ever less porous, inhumane and deadlier borders. Such thanatopolitics finds itself at odds with the humanist values that the EU is supposed to uphold, particularly cross-border solidarity, openness, non-discrimination and human rights. We argue that the EU b/ordering regime has turned fear of the non-EUropean into an increasingly unquestioned – even ‘commonsensical’ – anxiety that has become politically profitable to exploit by extreme nationalistic and EUrosceptic parties. The core of the EU’s autoimmunity that we want to expose lies within this irony: in its attempt to protect what it considers meaningful, the EU has unleashed an autoimmune disorder that has turned the EU into its own most formidable threat.

DRAWING INSPIRATION from the cultural, religious and humanist inheritance of Europe, from which have developed the universal values of the inviolable and inalienable rights of the human person, freedom, democracy, equality and the rule of law.

– Lisbon Treaty, 2009

Introduction

We write this article as concerns about the rising suicide attempts in the Moria refugee camp of Lesbos, Greece, have been worsening to the point that children are now taking their own lives (BBC Citation2019; MSF Citation2018; Tondo Citation2018). Recently, a teenager tried to hang himself from a pole and earlier, a 10-year-old boy tried to take his own life. It is hard to imagine the levels of anxiety and utter helplessness that would push a child to these extremes. Yet, the ways in which the EU has decided to make these people suffer are contributing to the catalogue of horrors that asylum seekers keep reluctantly thickening by trying to reach the EU: abandoned, dehydrated and famished amidst the desert (Laurent and O’Grady Citation2018); suffocated while smuggled in poorly ventilated lorries (AiK Citation2018); and detained, tortured, raped and enslaved by human traffickers and slave traders along their perilous odysseys (AP Citation2018; Kemp Citation2017; Malik Citation2019; van Houtum and Boedeltje Citation2009). As if their plight was not harrowing enough, instead of receiving them with the humanism promised by the preamble to its constitution, the EU’s atrocious refugee centres now leave undocumented migrants at the mercy of their own despair; crippled by the hopelessness and mental breakdown that results from languishing in the unfathomable squalor and brutality of these camps. A wide network of NGOs has documented how the “sweeping human rights violations” taking place in Greek detention camps have aggravated both gender-based violence against women and girls at “an alarming rate” as well as mental health problems among adults and children alike (Lucas, Ramsay, and Keen Citation2019). The constant violence and death among undocumented migrants trying to make their way to the EU has become so normal that they hardly make any headlines anymore: the only epitaphs that many of their irrecoverable bodies will ever be honoured with are either the unsentimental numbers or threatening red arrows with which undocumented migrants are represented in Frontex’s “risk analyses” (van Houtum and Bueno Lacy Citation2019).

Shamefully, the EU’s external border has become the deadliest border on the planet today (van Houtum Citation2015). Although estimates differ, there is some agreement that around 37,000 human beings have died in their attempt to reach the EU since the early ‘90’s – when Schengen was progressively incorporated into EU law (UNITED Citation2019). Yet, those who have scraped this number together realise that it will never be complete, for it is impossible to tell how many migrants have been lost to the perilous migration routes in North Africa or further afield. A crucial development of late that has aggravated this deadliness is the EU-wide trend to criminalise humanitarianism (Hockenos Citation2018; Nabert et al. Citation2019; Provera Citation2015). NGOs attempting to save lives at sea are now being harassed and charged with human smuggling and trafficking: a cynically hypocritical policy that will probably lead to higher casualties in the Mediterranean – turning it, as the UNHCR has put it, into a “sea of blood” (BBC Citation2018; Tondo Citation2019).

This overt callousness poses the conundrum that we analyse in this article: how did the EU, which only in 2012 was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize for its six-decade long contribution to the advancement of peace, dignity, freedom, equality, the rule of law and human rights in Europe – which are, according to the EU, the values of “the European way of life” – backslide so precipitously (Plenel Citation2019)? What happened to the “force for good” that the EU once prided itself on embodying (EC Citation2017)?

In this paper we contend that, far from a new or unexpected phenomenon, the convergence of violent migration policies along the external borders of the EU as well as the increasingly ethno-exclusionary politics that characterise the current public debate within the EU are the exacerbation of a longstanding b/ordering and othering trend in the policies of the EU (Jones Citation2017; Kriesi and Pappas Citation2015; van Houtum and van Naerssen Citation2002). Although we recognise that the EU is not a homogeneous political entity but a complex supranational organisation composed of diverse political institutions, culturally specific member states, antagonistic political parties of all ideological stripes and, overall, a wide range of interests, for the purpose of this article, we aim at evaluating the overall justice and self-harming reciprocity that the EU’s border regime exerts on its political community as a whole. To this end, we will analyse the b/ordering and othering regime of the EU through the lens of Jacques Derrida’s powerful notion of political autoimmunity, which he defined as the strange behaviour by which an organisation, “in quasi-suicidal fashion, ‘itself’ works to destroy its own protection, to immunise itself against its ‘own’ immunity” (Derrida Citation2003, 94). So, in contrast to the employment of the metaphor of “autoimmunity” by far-right politicians like Thierry Baudet to denounce “massive immigration” as the cause of the West’s “weakening body”, we resort to Derrida’s notion of autoimmunity to argue exactly the opposite: the EU’s autoimmunity is not rooted in its openness to the world but in the counterproductive effects of its current closed, discriminatory border regime. We argue that that the EU over time has developed a regime that consciously discriminates, endangers and criminalises the mobility of specific migrants on nativist grounds, alienates the EU from its self-professed values of rule of law and human rights, and thereby legitimises and normalises nativist authoritarian populists like Baudet and others (Boedeltje and Van Houtum Citation2008; van Houtum and Bueno Lacy Citation2017). Thus, the autoimmunity that we recognise has its roots inside EUrope and not beyond its borders. To structure our argument, we break down the EU’s border regime into three kinds of borders: (1) the pre-border of the visa control or, as we term it, the paper border; (2) physical border controls or what we refer to as the iron border and; (3) the post-border articulated in the reception and detention camps that keep migrants ostracised even after they have entered the EU. We analyse how these three cogwheels of the EU’s b/ordering and othering machinery have developed over time and, employing Derrida’s concept of autoimmunity, we will explain how they have become increasingly self-reinforcing engines propelling a self-destructive policy, and we will suggest three alternative directions that could take the EU out of this suicidal paradox (van Houtum Citation2010).

We conclude by stressing the ominous political implication of this EUropean border disorder: that the harrowing fate of immigrants is inextricably linked to the fate of the EU; their suffering and deaths are both symptoms and consequences of an autoimmune reaction that might ultimately lead to the EU’s demise. Succinctly put, by driving migrants and their children to commit suicide, the EU is opening a black hole that might swallow whole the ethos, values and laws on which much of its peace and prosperity have been built. In other words, we may be witnessing a dangerous authoritarian turn or even a sEUcide: the unnecessary self-destruction of the post-war project of the European integration with humanist ambitions.

Derrida’s Autoimmunity

Autoimmunity as an approach to the critical analysis of politics is most notably associated to the deconstructive method developed by Jacques Derrida. For him, autoimmunity evoked the mechanism by which a political hegemon flexes its “techno-socio-political machine” in order to consolidate its power yet unleashes a reaction that ends up undermining its power and perhaps even its survival. Derrida identified a series of symptoms typical of this autoimmune disorder: (1) a reflex of power and the reflection it produces; (2) a trauma that envisions an inauspicious future should nothing be done to prevent its repetition; (3) invisible and anonymous enemy forces that can hardly be pinned down to a particular state, cartographical location or physical entity; (4) apocalyptic descriptions of geopolitical events carrying religious undertones and, perhaps more decisively, (5) a double incomprehension: a power’s inability to comprehend the traumatic events to which it responds and to realise that what it deems its understanding of them – and on which it relies to devise reasonable responses to them (Derrida Citation2003, 90, 97–98). Ultimately, for Derrida, this autoimmunity sets in motion a dauntingly counterproductive machinery of self-fulfiling prophecies that are fuelled not by a “clash of civilisations” but rather by what Edward Said called “a clash of ignorance” (Citation2001).

In a famous and lengthy interview with the philosopher Giovanna Borradori, Derrida resorted to a deconstructive analysis of 9/11 to dissect the autoimmune syndrome that, according to him, afflicts the US’ global hegemony (Derrida Citation2003). He pointed out the asymmetry of how, on the one hand, 9/11 is remembered as an unparalleled historical tragedy yet, on the other, it is clear that certain events of similar or far more atrocious violence – not least orchestrated by the US – have happened many times before and will happen many times afterwards without arousing a comparable amount of media attention or political urgency. For example, whereas 9/11 enjoys the privilege of arousing pathos in Europe and the United States, quantitatively comparable or much worse killings beyond their their territories do not cause such an intense upheaval in their media and public opinion (e.g., Cambodia, Rwanda, Palestine, Iraq, Afghanistan and so on) (Derrida Citation2003, 92).

Unsurprisingly, by exposing the inconsistencies of the violent discourse on which the power of the world’s hegemon rests, humanists like Derrida and Edward Said have made themselves targets of a discourse which has sought to delegitimise their critiques by lambasting them as “philosophers of terror” – particularly in the US (Mitchell Citation2005, 913). Ironically, such ad hominem dismissal of critical philosophy is a symptom of the very autoimmune syndrome that Derrida intended to highlight. Even when philosophers as concerned with the subtleties of language as Derrida make sure to distance their critique of US hegemony from any apology of terrorism (Derrida Citation2003, 107), they are nonetheless rebutted not by counterarguments of comparable equanimity but by an alleged inability of self-reflection – which is the very target of their critique on geopolitical autoimmunity.

For Derrida, the catastrophic connotations of 9/11 should be understood as a reflex and reflection of both the magnitude of American power as well as of the significance of its contestation through terrorism. The autoimmunity of the military reflex and response that the US gives to Islamist terrorism lies, according to Derrida, in the mismatch between the crime that it tries to redress and the counterproductive nature of what such response achieves: rather than bringing the individuals responsible for such attacks to justice, the traumatic attacks of 9/11 have been used to justify a colossal global fight (“war on terror”) whose camps, defined in binary terms (“you’re either with us or against us”), have set an imaginary “West” against invisible and anonymous enemy forces – which have been apocalyptically lumped together in the geographical abstraction of “the axis of evil” – bent on the irrational mission to destroy. Arguably, such a reflex is a variation of what Étienne Balibar has called “racism as universalism” (Balibar Citation1989), i.e., a power system that cultivates a hierarchy of better and lesser races not through the coarse discourse of racial superiority and inferiority but, rather, through a more “sophisticated” discourse that acknowledges human diversity in order to justify an essentialist cultural incompatibility among its components. The proponents of this racist universalism misrepresent culture as though it were confined to homogenous and hermetic racial groups that are fundamentally incompatible and thus inherently antagonistic – the most infamous example being Samuel Huntington’s “clash of civilisations” (Citation1993, Citation1996).

The political discourse inspired by this clash-of-civilisations logic has characterised terrorism as an irrational threat rooted in allegedly “essential” civilisational antagonism: this baseless assumption (Brotton Citation2003; Bulliet Citation2006), together with its usually accompanying Islamophobia, has breathed new life into “the essential terrorist” (Said Citation2006): an all-purpose geopolitical scapegoat that the US – and the EU, to a less hysterical extent (Ernst Citation2013; Grosfoguel and Mielants Citation2006) – have been employing to justify state-led violence (Said Citation1997). Only the wars that the US has waged in response to the 4,000 deaths caused by 9/11 have killed more than 500,000 people counting the military and civilian deaths in Afghanistan, Iraq and Pakistan; and over 1,000,000 million people if one adds the US interventions in Syria and Yemen (Crawford Citation2018). Obama’s administration was dropping an average of three bombs per day and Trump’s war machine has been dropping one bomb every twelve minutes in one of the dozens of wars that the US has waged somewhere around the globe at any given point (Benjamin Citation2017; Turse Citation2017).

What Derrida elucidates is that the Islamist terrorism that has become a scourge across Europe is carried out and promoted by sectors of the European and global populations whose grievances are intimately related to the military devastation of large swathes of the world by US, NATO or EUropean armies. Since such disaffected groups lack the firepower to oppose much superior state armies through conventional warfare, they resort to asymmetrical warfare in the form of terrorism. Although such understanding does not make Islamist terrorism less horrifying or condemnable, it does make it seem like a much more rational and expected political response to the state terrorism that fuels it than the dominant political discourse would have us believe. Therefore, Derrida clarifies, the distinction between what is classified as either ‘war’ or ‘terrorism’ does not aim at establishing an ontological difference but rather a power difference: when you do to us what we do to you, you are not evaluated under the same benevolent light as we are but instead immediately denounced as an irrational criminal and thus as a legitimate target of ever more brutal retaliation. The US’ response is thus fuelled by incomprehension and hypocrisy: in order to protect its ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’, its own penchant for violence has constructed an enduring global war that is leading to openly racist and Islamophobic policies, laying the rationale of an increasingly authoritarian surveillance society in the US (Lieblich and Shinar Citation2018) and, overall, to the autoimmune weakening of its democracy (Faludi Citation2007).

The Autoimmune Borders of the EU

In what follows we will deploy Derrida’s notion of autoimmunity to analyse the architecture and ideology of the EU’s b/ordering and othering policies as a response to migration (van Houtum and van Naerssen Citation2002). To this end, we will dissect the EU’s b/ordering response into what we see as three core immunising borders of the EU which consist of different materialities and architecture: the pre-border (paper), the territorial border (iron) and the post-border (camp).

The Paper Border

Arguably, one of the most significant landmarks in the recent history of EU’s b/ordering policy has been the creation of a common external visa border – what we call “the paper border”. The common paper b/ordering of the EU dates back to the Schengen Agreement of 1985, which envisioned the gradual abolition of internal borders in exchange for the establishment of strict border controls along the EU’s external borders – which implied merging Member States’ border controls under a joint command. This agreement was further refined in the Dublin Convention of 1990 through the harmonisation of the EU’s common asylum procedures later enshrined in the Maastricht Treaty of 1992 (EC Citation2018). The effective establishment of the Schengen area in 1995 was incorporated into EU law by the Amsterdam Treaty that came into effect in 1999. Ushered by the Schengen Information System (SIS) and Visa Information System (VIS) that resulted from these agreements – implemented in 2006 and 2011, respectively – the EU established common external border surveillance systems aimed at filtering out global border crossers lacking the travelling papers required by the Schengen Agreement.

In effect, the EU as a whole started mimicking the nation-state with this paper b/ordering: it legalised and thereby normalised the hegemonic distinction between native and non-native EUropean citizens (Slootweg, Van Reekum, and Schinkel Citation2019; van Houtum and Bueno Lacy Citation2019). This territorial entrapment of EUrope marked a watershed in European history: it started to carve up not only a paper border between EUrope and “non-EUrope” but also an imaginary split between an anachronistically defined EUrope and the rest of the world. In this regard, it is crucial to emphasise that Europe has always been geographically undetermined and that it has never been either a congruent political organisation nor a demos (Delanty Citation1996); nor has the European continent ever been severed from its contiguous Mediterranean geographies by such sharp borders (Boedeltje and Van Houtum Citation2008; Braudel Citation1995, Citation2002). Yet, since the introduction of the Schengen Agreement, the EU has increasingly been fortifying itself and turning the Mediterranean into its common defensive moat.

This EU’s abduction of the idea of Europe – on which it does not have a monopoly – has been progressively reified through a conscious ordering brought about by the distinct process of EUropeanisation. This EU strategy to create an cultural attachment to its political project by identifying it with the heritage of Europe has been characterised by the creation of maps, coins, symbols, narratives and geopolitical practices that have attempted to shoehorn European history and culture into the current borders of the EU (Boedeltje and Van Houtum Citation2008; Bueno Lacy and Van Houtum Citation2015). Membership to the EU started to become associated with a historical belonging to Europe and, in contrast, neighbouring countries started to be imagined as lacking an intrinsic Europeanness – the othering process.

Tellingly, in 1987, the European Economic Community (ECC) – the immediate predecessor of the EU – received a request from Morocco to join its political community. Almost immediately, however, the Council rejected its application on the basis of Morocco not being a European country and thus not meeting the basic eligibility criteria for EU membership. It is worth noticing that the EU Council’s reasoning amounted to more than an innocent incursion into basic physical geography: its decision implicitly asserted that, not only was the Council the institutionalised version of Europe but also that, as such, it enjoyed the prerogative of legally defining and conferring, in a discretionary way, the arbitrary acknowledgement of Europeanness. Subsequently, the EU demarcated the Bosporus as yet another boundary of Europe with the creeping disqualification of Turkey (the only country to which EU membership has been promised yet never granted). Through these practices, the EU suggested that it regarded the borders of European culture as roughly coinciding with the idea of a Christian – or, at least, of an essentially non-Muslim – European civilisation. In other words, the present started to invent the past by b/ordering EUropeanness in a way that consciously left out large swathes of land whose people, cultures and heritage have played a crucial role in the history of Europe: North Africa, Asia Minor, Russia and, arguably, also the worldwide former colonies with which Europeans share so much transculturation. We argue that a troubling consequence of carving this hard external border – on which the EU’s invention of Europe has been predicated – has been the resurrection of traumatic prejudices about Europe’s others: the non-Europeans who have been traditionally imagined as backward and violence-prone intruders (Vitkus Citation1997). Although the existence of this civilisational threat is mostly confined to sensationalised accounts or downright fabrications magnified by murkily manipulated digital media (Callawadr Citation2017; Juhász and Szicherle Citation2017), the invisibility and anonymity inherent to such non-existent boogeymen has made their signifiers – i.e., the flesh-and-bone human beings immigrating to the EU – legitimate targets of ever more vicious state surveillance and repression.

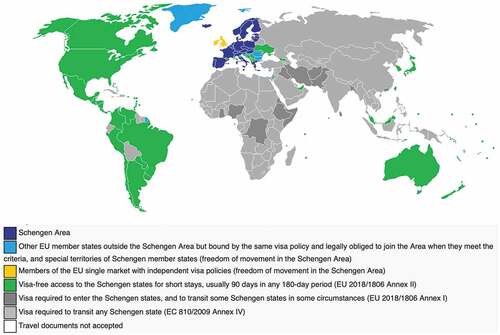

The striking culmination of this veritable paper b/ordering regime was the common Schengen list of visa-required countries introduced in 2001. This significant – yet still remarkably under-researched – “black and white list” (later re-branded as the “negative and positive list”) made a sharp discriminatory distinction between countries whose citizens require a visa paper to enter the EU – largely Muslim, African and overall less affluent countries – and those exempted from it – largely OECD members as well as a few countries in South America and Asia (Mau et al. Citation2012, Citation2015; Neumayer Citation2006; Salter Citation2003, Citation2006; van Houtum Citation2010; van Houtum and Lucassen Citation2016, see ).

Figure 1. The paper fortress of the EU.Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Schengen_visa_requirements.png (06-02-2020).

This list is based on the principle of nativist discrimination – a principle that is forbidden by law in all Member States of the EU and which runs against the EU’s own Copenhagen criteria and Lisbon Treaty – and has, in effect, almost entirely closed off legal migration channels to the EU for the large majority of the world (van Houtum Citation2010). This paper border is thus dividing EUropeans from non-EUropeans on the basis of arbitrary geographical discrimination even before the actual fences, border guards and detention camps are able to exert their own b/ordering effects. This, what could be termed, pre-border has outsourced the EU’s border control to government offices far away from the EU’s actual border. So, the paper border should not be conceived as a line on a map dividing one country from another but rather as a global techno-political mechanism meant to b/order the EU at remote control (Zaiotti Citation2016). Rather than guards with guns, this first border of the EU is watched over by bureaucrats armed with paper and entrenched in faraway embassies. Through this political technology that could be termed tele-bordering, all citizens of a large group of nations – barred few exceptions – are blacklisted. This means that, in practice, most of the citizens of these blacklisted countries cannot acquire the visas they require to legally travel to the EU. The implication is that the paper border of the EU remotely and invisibly cage people in the inequitable lottery of birth (see Rawls Citation1999, 118–123).

The result of this tele-bordering has been as counterproductive as it has been dramatic (Miller Citation2019). The first suicidal paradox inherent to the creation of the EU’s ‘paper fortress’ is that even if someone is fleeing from life-threatening situations in their country, they cannot get a visa because of the country they are fleeing from. By refusing them regular entry, the EU’s paper fortress paradoxically punishes people for being born in the wrong place and for trying to escape an oppressive regime, violence, economic despair or natural disaster. This constitutes not only a violation of international refugee law but a factual rejection of both the humanist ethos and legal custom on which the internationally-recognised right to ask for another country’s protection has been built. Such custom includes an express exhortation to governments for the “issue and recognition of travel documents”, which “is necessary to facilitate the movement of refugees, and in particular their resettlement” (UN Citation1951). The result of the EU’s wilful non-compliance with such international obligations is that – and this is the second paradox of this paper border regime – access to the EU’s regular asylum system can only be gained irregularly – through smugglers and other illicit ways. The safe alternative of air travel is also excluded because, since 2001, air carriers can be fined for taking on board migrants lacking the required visa (Directive 2001/51/EC), a policy that amounts to the erection of an effective b/ordering dome over the EU’s airspace (FitzGerald Citation2019).

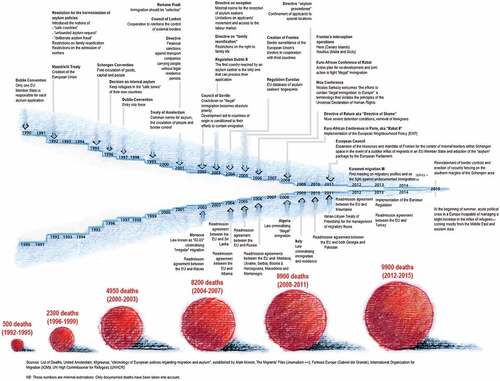

This paradoxical policy of legally welcoming refugees yet illegalising the channels that would allow them to legally and safely travel to the EU is what FitzGerald has recently described as “the Catch-22” of the rich world’s asylum policies (FitzGerald Citation2019). By forcing asylum seekers to undertake a reckless odyssey – which also criminalises the travel of both a large portion of the world as well as those who assist undocumented migrants in their journeys – the EU has boosted a large-scale smuggling industry that profits from the legal void that the EU itself has made sure to enforce. Rather than the humanitarian philanthropy with which the EU so duplicitously pretends to characterise its border regime (Lavenex Citation2018), its anti-smuggling – and, at its core, anti-refugee – policies have become the legal framework on which a billion-dollar industry of refugee smugglers and border enforcers (e.g., Frontex) has thrived (Lyman and Smale Citation2015; Spijkerboer Citation2018). This is the third paradox of the paper border regime: the EU has decided – against its own principles and international obligations – to voluntarily create a border system that ensures only more “illegality”, corruption and human insecurity. Thus, this paper border should be credited with turning the routes to seek asylum in the EU – a supposedly safe destination – into a grim and perilous survival of the fittest. Since this is precisely the kind of distress that refugee law is intended to prevent, the so-called “migration crisis” of 2015 in the EU would be better described as a “refugee-protection crisis”. By erecting such an insurmountable paper border, the EU has advocated a politics of death, a necropolitics (Mbembé Citation2003). Below, provides a chronology that shows the rise of the deadly EU’s external border discussed so far.

Figure 2. The rise of the deadly EU border.Source: https://visionscarto.net, 2016, translated from French by authors.

Translated into Derrida’s conceptualisation of autoimmunity, we argue that the reflex of power that has manifested itself as the common paper b/ordering – intended to protect the EU from unwanted foreigners – has been predicated on an inexistent apocalyptic threat of invisible and anonymous non-EUropeans. Moreover, the development of the EU Commission’s paper-border regime has gone hand in hand with the promotion of a global “war against undocumented migrants and their smugglers” – who much of the EUropean press and opportunistic politicians wantonly associate with all sorts of crime and moral decay (Albahari Citation2018; Burrell and Hörschelmann Citation2019; Trilling Citation2019). The consequences of this rhetoric, which imitates the versatile vagueness of the global “war on terror”, have been considerable: it has strengthened and legitimised cultural prejudices against exceptionalised migrants; it has simultaneously helped to normalise and popularise a stream of EUrosceptic illiberal political movements that are trying to erect themselves into the preservers of Europe’s nativist culture and it has led to a politics of death that, shamefully, is presented as the regrettable but unavoidable collateral damage that EUrope has to accept in order to preserve the “enlightened” European civilisation that the EU has essentialised. The incomprehension lies in the EU’s inability to comprehend the suicidal paradox in which it has trapped itself: in a short period – since the Schengen Agreement was signed in 1985 – the EU’s has triggered a border politics of autoimmunisation that, in an inexorably self-defeating manner, aims at shielding EUrope’s humanist heritage by surrounding it with an ever more anti-humanist border regime.

The Iron Border

The second b/ordering – or immunisation – strategy of the EU that we wish to address is the construction of all kinds of material deterrences that have been erected over time along the external borders of the EU and which we metonymically classify as “the iron border”. This border complements the ‘gate at a distance’ of the paper border, it encompasses all land border fences, walls and barbed wire; typically guarded by stern-looking men and women in uniform who are equipped with guns, handcuffs, surveillance vehicles and sophisticated techno-military gear, on-the-spot passport controls at airports, trains and highways; as well as surveillance patrols along the EU’s maritime borders tasked with stopping refugees from either reaching the EU or remaining in it (Gualda and Rebollo Citation2016; Minca and De Rijke Citation2017; van Houtum Citation2010). In contrast to the remote-controlled legal procedures of the largely invisible paper border, an important aspect of the iron border around and within the EU’s territory is its purposeful visibility to the public eye. It suffices to google “fences” and “EU” (or anything akin) to come across thousands of pictures featuring the heterogenous materiality of the iron border – such as the iconic fences separating the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla from Africa; as well as the recently built fences along the Hungarian-Serbian border. To a large extent, the iron borders should be understood as a conscious performative power play, a geopolitical spectacle conceived as a public-relations’ strategy intended to project safety and security for domestic electoral consumption by manufacturing a potent infrastructure that portray the government as being “tough on unwanted outsiders”. The straightforward message of such political theatre is that, the government is protecting its people by keeping a close eye and a clenched fist on anyone trying to enter the country by irregular means. More than a line of control alone, it has also proved itself as a camera-happy and televised spectacle, a performative mise en scène, that employs an unwritten but foreseeable script where the barbed wire epitomizes the division between EUrope and a threatening world of incompatible and undesirable strangers and that implicitly casts unsuspecting migrants into the threatening stereotypes on which xenophobic EUrosceptics feed.

This intended visibility and attention-grabbing character of the iron border only intensified with the outbreak of the refugee-protection crisis in the summer of 2015. This included the sensationalised arrivals of undocumented immigrants disembarking from their fragile dinghies, trying to climb fences or cutting their way through barbed wire. Although governments and migration scholars estimate that the number of the largely invisible visa-overstayers – who entered regularly – is at least as large as the number of undocumented migrants, migrants trespassing the EU’s physical outer borders have received much more media as well as political attention. Undoubtedly, what has triggered this sense of crisis is that populist politicians have relied on these images to frame undocumented migration as an invasion and a threat to sovereignty. Ultimately, this narrative constitutes the rationale of the EUropean far-right’s core ethno-exclusionary demand: to call for harder borders (Metz Citation1982; Trilling Citation2019). The political sway of these border aesthetics should not be underestimated: as a response to this ‘spectacular’ theatre of trespassing undocumented migrants, the EU has only expanded its iron border control (DeGenova Citation2017). It is estimated that the EU has constructed almost 1,000 km of iron borders in the last two decades: more than six times the total length of the Berlin Wall (Ruiz Benedicto and Brunet Citation2018) – to which the digital surveillance systems at sea and on land should be added. Not surprisingly perhaps, though still ironically, the costs of physical border controls have gone up at about the same speed and in a similar proportion as the turnover in the smuggling industry (The Migrants’ Files Citation2014). Since its foundation in 2004, Frontex’s budget has exponentially increased – from 6.2 million in 2004 to 281 million in 2017 – and it is still expected to rise up to 322 million in 2020, making it one of the best funded agencies in the EU (Grün Citation2018). Between 2000 and 2014 (one year before the refugee-protection crisis), the EU had already spent almost 13 billion euros on border control. This has conferred the EU the dishonourable distinction of having one of the costliest border regimes on the planet. And as long as the EU’s visa-based paper border keeps working as the main manufacturer of irregular migrants, we should expect the iron border and its costs to keep rising too.

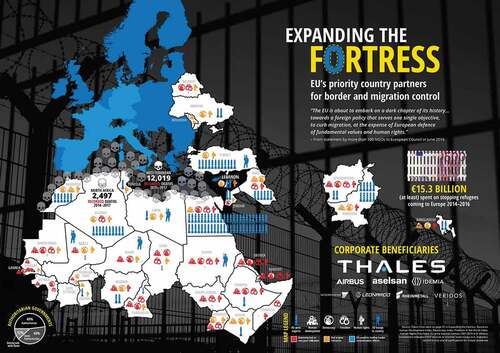

In the meantime, the EU has struck a growing number of bilateral deals with neighbouring countries in order to stop undocumented migrants. The EU is b/ordering contiguous non-EU autocracies as its immigration enforcers in exchange for large sums of money – raising the costs of external border controls and boosting the border security industry even further (see ). This neo-colonial outsourcing of migration control to poorer countries, warlords and dictators is factually stretching the EU’s own iron border far beyond its EU’s actual physical border (Lahav Citation1998; Nye Citation2004; Lavenex Citation2006; Rijpma and Cremona Citation2007; Levy Citation2010; Ferrer-Gallardo and Van Houtum Citation2014; Zaiotti Citation2016; Carrera et al. Citation2018). This amounts to the same kind of “dictator-empowering policy” that the EU not so long ago decried as dirty and shameful when Berlusconi and Gaddafi struck a deal in 2010 that committed Libya to stop migrants in return for money (Bialasiewicz Citation2012). Today, the EU pact with Libya has given rise to a full-fledged slave market run by cold-blooded human traffickers who, incentivated by the EU’s crackdown on irregular migration and the resulting business downturn of would-be profitable passengers, are now auctioning economic migrants and refugees as slaves (Asongu and Kodila-Tedika Citation2018). How times have changed. Only one self-manufactured “crisis” later, the EU is hiring neighbouring autocratic regimes through incentives that amount to outright bribes (Malik Citation2019; Verhofstadt Citation2018). Today the EU supports autocratic regimes even though they have no qualms about violating the rights of asylum seekers by violating the legal prohibition of non-refoulement – a touchstone of refugee law – in order to keep undocumented migrants at bay (DW Citation2019). The infamous deal between the EU and Erdogan’s despotic administration is a case in point: Turkey is cutting short the journeys of asylum seekers’ travelling towards the EU in return for 6 billion euros and the (conditional) promise of visa-free access to the EU for its citizens.

Figure 3. Expanding Fortress Europe. Source: https://www.tni.org/files/expanding_the_fortress_-_infographic.jpg (Akkerman Citation2018).

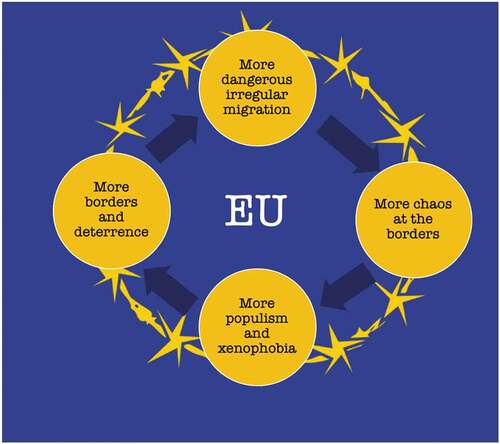

The autoimmunisation of this ‘iron’ b/ordering strategy lies in the incongruence between the EU’s desire to gain more control over its borders in order to safeguard its democracy, human rights, the rule of law and diplomatic power of attraction; and its choice to accomplish this by employing the military force of autocratic and unsafe neighbouring countries whose lack of respect for the EU’s fundamental principles allows them to conduct the kind of politics antithetical to EU values. By outsourcing its border policies to smugglers and repressive regimes with the aim of tightening its grip on migration, the EU is, incomprehensibly: (1) increasingly losing sight and control over its ever expanding, ever more shadowy and ever more distant physical border, thus undermining its own sovereignty and making itself liable to blackmail and, at least, morally complicit in the mistreatment of refugees by autocratic regimes elsewhere; (2) widening the global mobility divide between those who can travel and those who cannot while creating more human misery, criminal economic activities and political instability in these countries – therefore paradoxically feeding their populations’ desire to migrate (Malik Citation2019); (3) hollowing out the EU’s core values and contributing to legitimise the discourse on which illiberal Eurosceptic populists draw their strength (van Houtum and Bueno Lacy Citation2017). The result is a tunnel vision which keeps the EU obsessed with stopping undocumented migrants, literally at all costs, even though the sensationalised chaos and manufactured ‘insecurisation’ at its borders is undermining solidarity with refugees while strengthening the hand of populist EUrosceptics, who exploit the threat inherent to the aesthetics of the iron border to push their demands for even higher walls and an ever more vicious border regime (see ).

The Border Camp

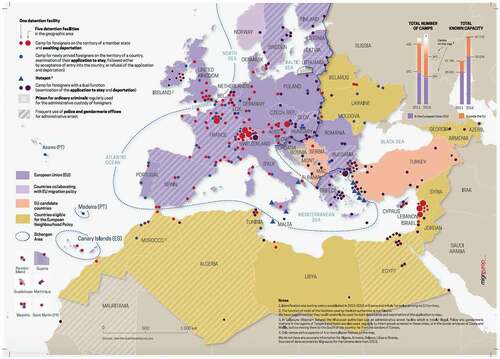

The third immunising b/ordering pillar of the EU’s border architecture that we identify here is the post-border or what we refer to here as “the border camp”. Undocumented migrants who have the fortune to make it across the paper and iron borders must endure yet another procedure of exclusion upon arrival to the EU’s territory in the form of the concentrated segregation of the migrant camp (see for an inventory of camps in Europe and further afield by Migeurop). This secluded reception, in which migrants have to wait until their case is ‘processed’, coincides with what Derrida called “hostipitality” (Citation2000): a portmanteau of hostility and hospitality. Like the iron border, this policy aims to exceptionalise migrants in space and its political significance and implications have attracted vast and growing critical attention from political philosophers, political geographers and scholars from akin disciplines (Agamben Citation1997, Citation2002, Citation2005; McElvaney Citation2018; Minca Citation2005; Vaughan-Williams Citation2009).

Figure 5. The encampment in EUrope and near abroad. Source: Migreurop 2016 (http://www.migreurop.org/IMG/pdf/migreurop_carte_en_hd-compressed.pdf).

In the case of the spatially segregated border camp, the Derridean reflex of power aims at the ‘abnormalisation’, invisibilisation and exceptionalisation of undocumented migrants from visa-obliged countries. These waiting camps correspond to what Vaughan-Williams (Citation2015) described as “zoo-like spaces”: refugees are caged yet exposed to the camera at all times, a spatial confirmation of their social undesirability and an animal-like representation that, we argue, contributes to consolidate the already abundant disdain or plain fear for refugees in the EU. The segregation and maltreatment of people who share a bodily resemblance or cultural affinity with already-discriminated ethnic minorities in EUropean societies send a toxic message to the EU’s own citizens: it tells them that the fundamental rights to which the EU adheres do not fully apply to undocumented migrants (Virdee and McGeever Citation2018). By legitimising such discrimination, the immunisation tactic of the border camp fails to ensure the protection of law and order that it was designed to safeguard and, instead, emboldens populist leaders and political movements in the EU who would like to rely on the same discriminating discourse and excluding practices not only against increasingly vilified migrants but also against migrant-looking citizens and antagonistic political minorities (Bueno Lacy and Van Houtum Citation2013; van Houtum and Bueno Lacy Citation2017; Vasilopoulou Citation2009).

Certainly, there is a considerable number of people willing to rescue refugees from the claws of the sea or help them find their way into EUropean societies. However, their humanitarian deeds are by and large offset by the calculated tactics of separating specific people from blacklisted countries and warehousing them under marginalised conditions while making them dependent on the government – for both their livelihood and freedom. This amounts, in Derrida’s terms, to an incomprehensible deterrence politics that is counterproductive for both the (mental) health and integration of migrants as well as for solidarity across the EU (Borg-Barthet and Lyons Citation2016; Fernández Citation2014; HRW Citation2012; Kingsley Citation2018; Leape Citation2018; Mountz and Kempin Citation2014; Smith Citation2018; van Houtum Citation2010). To make things worse, some states like Hungary, Poland and Slovakia have even expressly stated that they are willing to host only Christian refugees (Bastide Citation1968; Bonnett Citation1998; Cienski Citation2017; Reuters Citation2015). Moreover, asking a country like Greece to be solidary with the rest of the EU – by accepting what is perceived as “the burden” of managing the arrival of asylum seekers given its position at the EU’s external border – when the EU’s lack of solidarity turned Greece into the epitome of devastating austerity is bound to nurture resentment against the EU and undocumented migrants alike (Howden and Fotiadis Citation2017; Smith Citation2018; Theodossopoulos Citation2016). Given the cold shoulder that other EU Member States showed it when it needed their solidarity the most, Greece does not seem very receptive to the EU’s calls to improve the inhumane conditions of detained migrants languishing on its Mediterranean islands. What is more, Greece has been accused of misusing EU funds meant for the critically overcrowded and underfunded refugee camps in its Aegean islands and its new government is now busy with both the senseless destruction of refugee-support networks like Exarcheia as well as with the introduction of laws that allow it to deport thousands of asylum seekers without concern for their rights under international refugee law (King and Manoussaki-Adamopoulou Citation2019; Smith Citation2018, Citation2019). This aggravating animosity of the Greek state towards the EU and undocumented migrants is critical to understand how the EU’s vicious autoimmune cycle is being thrown into ceaseless spins by both its internal austerity policies and its external border regime.

In this regard, it is worthwhile to reflect on the question that Derrida posed in his deconstruction of geopolitical autoimmunity: “Can’t ‘letting die,’ ‘not wanting to know that one is letting others die’[…] also be part of a ‘more or less’ conscious and deliberate terrorist strategy?” (Derrida Citation2003, 108). Derrida’s reflection poses a harrowing question when applied to the EU’s border management: is it less cruel because it repels potential refugees at a distance by preventing them from even legally applying to migrate to the EU? Is it less violent because it premeditatedly builds obstacles that preclude asylum seekers from safely entering the EU and purposefully creates ever more inhumane hosting conditions once they have reached what they imagined would be a safe territory? Perhaps, by pushing (involuntary) migrants – many of whom have sought the EU’s protection – into a hopelessness so intolerable that they prefer to find comfort in their own deaths, the suicidal autoimmunity of the EU’s b/ordering strategy is coming to an abhorrent full circle.

Towards a Responsible and Sustainable Border Policy

“For the first time in 30 years, I really believe that the European project can fail” (Lefranc Citation2016). This alarming message came from no less than the vice-president of the European Commission, Frans Timmermans. The way he sees it, the recent “refugee crisis” has strained solidarity across the EU to the brink of rupture. The continuation of this crisis, Timmermans frets, poses an existential threat to the project of European integration.

Employing Derrida’s notion of autoimmunity, we have argued that to a large extent the EU has been entrenching itself into this dead end. Not only has the EU been unable to find support for a comprehensive and responsible migration and asylum system across its supranational community but the EU is increasingly taking the self-destructive road towards dirty deals, multiplying its human rights violations and pushing back legitimate asylum seekers to countries where they might die or suffer severe harm. The politicisation of migration and the coinciding adoption of extreme policies by establishment parties under the pretence of “normality” as a strategy to stop the rise of extreme far-right anti-immigrant parties has by now – one would think – proven to be severely counterproductive (Mudde Citation2019a, Citation2019b; van Houtum and Bueno Lacy Citation2017). What is more, since the structural causes that keep pushing people away from their countries – e.g., inequality and poverty, armed conflict and widespread violence, droughts and agricultural collapse, overfishing and the depletion of ancestral fisheries, and overall livelihood-destroying global ecocide – are unlikely to be addressed anytime soon and the worsening effects of climate change are surely going to keep magnifying them (Franzen Citation2019; Nordås and Gleditsch Citation2007), the question the EU should be asking is not whether the next crisis of solidarity and its liberal democratic spirit will come, but rather when.

To break this self-defeating political path, the EU urgently needs a drastic revision of both its violent b/ordering regime and the essentialist EUropean discourses that support it (Jones Citation2017). To this end – and as a conclusion – we offer three different paths that the EU could take: normalisation, legalisation and equalisation (van Houtum Citation2015; van Houtum and Lucassen Citation2016). To begin with, the reforms would require, at the very least, a normalisation of people migrating in today’s globalizing world. At the same time, normalisation also implies to make informed policy decisions based on scientific assessments rather than imaginaries and narratives. The dominant pattern of world migration shows that migration is still very much the exception rather than the rule: 97% of the world’s population is not a migrant. Refugees represent less than 1% of the world’s population and more than 85% of all refugees on the planet are hosted outside the EU – mostly in less affluent countries (De Haas Citation2016; UNHCR Citation2019). Moreover, the EU’s neighbouring countries are hosting a higher number of refugees than the EU – in absolute and relative terms. Although this does not mean that hosting an increasing number of refugees is not difficult for EUropean societies, what it does mean, however, is that such a challenge does not warrant either a transfer of responsibility to dictatorships or the buffer-politics of “dirty deals” that the EU has been undertaking. Rather, this geopolitical challenge requires cooperation among EU Member States. The panic-stricken depiction of an “invasion” of migrants coming to the EU is not only scientifically unfounded, but also dehumanising and contemptible. It is a worrying sign of our times to realise that all kinds of phobic metaphors to refer to undocumented migrants have become normalised in the EU over the last decade. Think of the threatening descriptions and (cartographic) imaginaries of undocumented migrants conjured up by hydraulic metaphors such as flows, streams, floods and waves; zoological metaphors evoking swarms, flocks, cockroaches and insects; as well as bellicose and criminalising metaphors that bring to mind invasions, armies, illegal and criminal activities, hordes and fighting (see Mamadouh Citation2012; van Houtum Citation2010; van Houtum and Bueno Lacy Citation2019). When dehumanisation is normalised and unchallenged, physical violence and untamed extremism become ever more likely.

Apart from normalisation, meaningful reform would also require legalisation: the creation of more legal channels for migrants to safely travel to EU and which would allow for the circularity of migration (Clemens, Dempster, and Gough Citation2019). This specific path also requires the EU to crack down on the boogeyman represented by “the economic migrant”. The fear of economic migrants reveals perhaps one of the biggest flaws of Schengen: the criminalisation of people whose biggest threat to the prosperity of the EU polity seems to be their ambition to work in order to earn the kind of living standards that their countries of origin cannot offer them. It is a testament to the extreme nature of our times that such unremarkably liberal ideas as respect for those who seek fairness of opportunities as well as the right to work are today seen as extreme proposals for a project, like the EU, that prides itself on its universal rights, rule of law and market economies (Holmes Citation1993, 3–4). Not only is creating more legal channels morally just but it would be in the interest of everyone: migrants themselves, their countries of origin – where they send much of the money they earn – and, finally, also in the interest of the EU’s economy, particularly regarding the preservation of its welfare states. The legalisation of migratory movements could not only drastically disrupt the illicit chaos and high death rates at the gates of the EU but it would also protect the EU’s own rule of law by disrupting the supply-and-demand chains on which smugglers, slave traders and even violent extremists depend. Such legalisation would also buttress the welfare state by tapering off the informal sector in the economy and allowing migrants to stand again on their own feet; and by setting clear rules for migrants to acquire citizenship and social security rights, depending on their years of participation. With legalisation we also mean abiding by the EU’s own rule of law: although all EU Member States have signed the Refugee Convention and its protocols – which means that their pledge to aid people escaping their countries is a commitment of their own volition – their increasingly vicious border regime is vigorously hollowing out the protections that these international agreements afford to asylum seekers. Trampling upon such international obligations stands in direct contradiction with the EU’s own rule of law and is weakening its diplomatic power while legitimising xenophobia and the arbitrary abuse of power.

Finally, a comprehensive reform of the EU’s border regime should encompass an equalisation – i.e., an equal distribution of refugees across the EU and among the neighbouring regions on the basis of shared responsibility and resettlement; as well as an immediate end to the concentrated-segregation politics of the EU’s current refugee camps. In the longer run, an equalisation agenda would imply a wider series of tasks that would bring the EU outside its perceptual isolation by assuming itself as the significant global actor it is. This would imply the EU’s pursuit of fair trade, a global green deal and the peaceful resolution of conflicts – at least around its immediate neighbourhood or, at the very least, in the regions and countries that are the sources of its largest refugee populations. Furthermore, the EU should rely on international institutions to support global agreements like the Global Compact for Migration. Ultimately, such equalisation agenda would also need to take into account what is perhaps the most important measure: a drastic revision of the discriminatory visa regime in order to root out the nativist principle built into the design of the EU’s political community. Of the three borders discussed in this article, this paper border is arguably the most resilient root of the EU’s refugee-protection crisis: the autoimmune policies devised to address this form of human mobility have not only magnified the challenge posed by an increased number of asylum seekers in the EU but they have also exacerbated other geopolitical problems to the point that this self-made migration crisis has become the most threatening existential EU has ever faced. As we have argued, the visa regime of which the EU is a chief advocate has created a global caste system of elite travellers whose mobility is welcomed and people born in the wrong place whose mobility is banned, criminalised and deterred to the extent that they could die not only trying but also even after they have arrived. The deliberate intention to keep the less affluent and religiously different trapped at a distance simply because they were born there is an act of discrimination that is at odds with the equal moral worth of human beings that the EU is supposed to exalt and defend. Surely, the EU’s discriminatory visa system, in spite of being hardly a hundred years old, may today seem normal and unbreakable, but so did once the trans-Atlantlic slave trade, South Africa’s apartheid and the divine right of kings.

The discussion on how to achieve a responsible, sustainable and just border policy surely does not end here. What is worrying, however, is that, for now, the EU seems poised to keep medicating itself with its increasingly auto-toxic remedies. This policy, we argue, should not be regarded as either a momentary lapsus but, rather, as a train wreck happening in slow motion. Since the EU closed its external closure of the borders with the introduction of Schengen, its political community has followed an ever deadlier path of discriminatory global self-enclosure that excludes a large portion of the world. Today, the EU is experiencing the limits of this border model: the current politicisation of migration and the measures to curtail the movement of immigrants is shaking the EU to its foundations, endangering the openness of Schengen, the non-discrimination principle, the protection of human rights, solidarity and the rule of law, the liberal-democratic principles of the Copenhagen criteria and, ultimately, the very ethos of the EU. Barring a drastic change in the EU’s course, the death and suicide of undocumented migrants and their children – which we denounced at the outset of this article – will not stop. What is more foreboding, perhaps, is that the EU – at least as we know it – might share their fate. Perhaps Frans Timmermans is right: for the first time, the project of European integration that has brought historically unseen prosperity and peace to Europe seems like it might fail. Ironically, it might fail because the European Union has become its own most formidable threat.

References

- Agamben, G. 1997. The camp as the nomos of the modern. In Violence, identity, and self-determination, ed. H. De Vries and S. Weber, 106–18. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Agamben, G. 2002. Remnants of Auschwitz: The witness and the archive. New York: Zone Books.

- Agamben, G. 2005. State of exception. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- AiK (Agencies in Kecskemét). 2018. Four men jailed over deaths of 71 migrants locked in lorry. The Guardian, June 14. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jun/14/people-smuggling-gang-jailed-over-hungary-migrant-lorry-deaths

- Akkerman, M. 2018. Expanding the fortress. The Transnational Institute. https://www.tni.org/en/publication/expanding-the-fortress

- Albahari, M. 2018. From right to permission: Asylum, Mediterranean migrations, and Europe’s war on smuggling. Journal on Migration and Human Security . 6(2). 1–10.

- AP. 2018. Three female migrants found murdered near Greece-Turkey border. The Guardian, October 10. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/oct/10/three-women-found-dead-near-greece-river-border-with-turkey

- Asongu, S. A., and O. Kodila-Tedika. 2018. “This one is 400 Libyan dinars, this one is 500”: Insights from cognitive human capital and slave trade. International Economic Journal 32 (2):1–16. doi:10.1080/10168737.2018.1480643.

- Balibar, E. 1989. Racism as universalism. New Political Science 8 (1–2):9–22. doi:10.1080/07393148908429618.

- Bastide, R. 1968. Color, race, and christianity. In Color and race, ed. J. Franklin, 34–49. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- BBC. 2018. Italy aquarius: Prosecutors order migrant rescue ship seizure. BBC, November 20. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-46274328

- BBC. 2019. Lesbos migrant camp children say they want to die. December 19. https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-europe-50814521/lesbos-migrant-camp-children-say-they-want-to-die

- Benjamin, M. 2017. America dropped 26,171 bombs in 2016. What a bloody end to Obama’s reign. The Guardian, January 9. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/jan/09/america-dropped-26171-bombs-2016-obama-legacy

- Bialasiewicz, L. 2012. Off-shoring and out-sourcing the borders of EUrope: Libya and EU border work in the Mediterranean. Geopolitics 17 (4):843–66. doi:10.1080/14650045.2012.660579.

- Boedeltje, F., and H. Van Houtum. 2008. The abduction of Europe: A plea for less ‘unionism’ and more Europe. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 99 (3):361–65. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2008.00467.x.

- Bonnett, A. 1998. Who was white? The disappearance of non-European white identities and the formation of European racial whiteness. Ethnic and Racial Studies 21 (6):1029–55. doi:10.1080/01419879808565651.

- Borg-Barthet, J., and C. Lyons. 2016. The European Union migration crisis. Edinburgh Law Review 20:230–35. doi:10.3366/elr.2016.0346.

- Braudel, F. 1995. The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean world in the age of Philip II, 1–3. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Braudel, F. 2002. The Mediterranean in the ancient world. London: Penguin.

- Brotton, J. 2003. The renaissance bazaar: From the silk road to Michelangelo. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bueno Lacy, R., and H. Van Houtum 2013. Europe’s border disorder. E-International Relations, December 5. https://www.e-ir.info/2013/12/05/europes-border-disorder/

- Bueno Lacy, R., and H. Van Houtum. 2015. Lies, damned lies and maps: The EU’s cartopolitical invention of Europe. Journal of Contemporary European Studies 23 (4):477–99. doi:10.1080/14782804.2015.1056727.

- Bulliet, R. W. 2006. The case for Islamo-Christian civilization. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Burrell, K., and K. Hörschelmann. 2019. Perilous journeys: Visualising the racialised “refugee crisis”. Antipode 51 (1):45–65. doi:10.1111/anti.12429.

- Callawadr, C. 2017. The great British brexit robbery: How our democracy was hijacked. The Guardian, May 7. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/may/07/the-great-british-brexit-robbery-hijacked-democracy

- Carrera, S. N. El Qadim, M. Fullerton, B. Garcés-Mascareñas, S. York Kneebone, A. M. López Sala, N. Chun Luk, L. Vosyliuté. 2018. Offshoring asylum and migration in Australia, Spain, Tunisia and the US. Brussels: CEPS.

- Cienski, J. 2017. Why Poland doesn’t want refugees. Politico, May 21. https://www.politico.eu/article/politics-nationalism-and-religion-explain-why-poland-doesnt-want-refugees/

- Clemens, M., H. Dempster, and K. Gough. 2019. Promoting new kinds of legal labour migration pathways between Europe and Africa. London & Washington: Centre for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/promoting-new-kinds-legal-labour-migration-pathways-between-europe-and-africa

- Crawford, N. C. 2018. Human costs of the post-9/11 wars: Lethality and the need for transparency. Brown University. https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2018/Human%20Costs%2C%20Nov%208%202018%20CoW.pdf

- De Genova, N. 2017. The borders of “europe”. autonomy of migration, tactics of bordering. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- De Haas, H. 2016. Refugees: A small and relatively stable proportion of world migration. Hein de Haas’ blog, August 22. http://heindehaas.blogspot.com/2016/08/refugees-small-and-relatively-stable.html

- Delanty, G. 1996. The frontier and identities of exclusion in European history. History of European Ideas 22 (2):93–103. doi:10.1016/0191-6599(95)00077-1.

- Derrida, J. 2003. Autoimmunity: Real and symbolic suicides. In Philosophy in a time of terror: Dialogues with Jurgen Habermas and Jacques Derrida, Trans. P. A. Brault and M. Naas, 85–136. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Derrida, Jacques. 2000. Hostipitality. Angelaki 5 3:3–18. doi:10.1080/09697250020034706

- DW (Deutsche Welle). 2019. Outsourcing border controls to Africa. Deutsche Welle, March 13. https://www.dw.com/en/outsourcing-border-controls-to-africa/av-45599271

- EC (European Commission). 2017. A force for good in a changing world. European Commission, March 24. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/commissioners/2014-2019/mimica/blog/force-good-changing-world-0_en

- EC (European Commission). 2018. Schengen, borders & visas. European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/borders-and-visas_en

- Ernst, C. W. 2013. Islamophobia in America. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Faludi, S. 2007. The terror dream: Fear and fantasy in post-9/11 America. New York: Henry Holt & Co.

- Fernández, B. 2014. Detention in Malta: Europe’s migrant prison. Al Jazeera, May 18. https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2014/05/detention-malta-europe-migrant–201451864644370521.html

- Ferrer-Gallardo, X., and H. Van Houtum. 2014. The deadly EU border control. ACME 13 (2):295–304.

- FitzGerald, D. S. 2019. Refuge beyond reach: How rich democracies repel asylum seekers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Franzen, J. 2019. What if we stopped pretending? The New Yorker, September 8. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/what-if-we-stopped-pretending

- Grosfoguel, R., and E. Mielants. 2006. The long-Durée entanglement between Islamophobia and racism in the modern/colonial capitalist/patriarchal world-system: An introduction. Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge 5 (1):1–12.

- Grün, G. C. 2018. Follow the money: What are the EU’s migration policy priorities? Deutsche Welle, February 15. https://www.dw.com/en/follow-the-money-what-are-the-eus-migration-policy-priorities/a-42588136

- Gualda, E., and C. Rebollo. 2016. The refugee crisis on Twitter: A diversity of discourses at a European crossroads. Journal of Spatial and Organizational Dynamics 4 (3):199–212.

- Hockenos, P. 2018. Europe has criminalized humanitarianism. Foreign Policy, August 1. https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/08/01/europe-has-criminalized-humanitarianism/

- Holmes, S. 1993. The anatomy of antiliberalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Houtum van, H. 2010. Human blacklisting: The global apartheid of the EU’s external border regime. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (6):957–76. doi:10.1068/d1909.

- Houtum van, H. 2015. Dood door beleid; EU dodelijkste grens op aarde. De Volkskrant, July 1. https://www.volkskrant.nl/columns-opinie/dood-door-beleid-eu-grens-dodelijkste-grens-op-aarde~be784791/

- Houtum van, H., and F. Boedeltje. 2009. Europe’s shame: Death at the borders of the EU. Antipode 41 (2):226–30. doi:10.1111/anti.2009.41.issue-2.

- Houtum van, H., and L. Lucassen. 2016. Voorbij fort Europa. Amsterdam: Atlas Contact.

- Houtum van, H., and R. Bueno Lacy. 2017. The political extreme as the new normal: The cases of brexit, the French state of emergency and Dutch Islamophobia. Fennia 195 (1):85–101. doi:10.11143/fennia.64568.

- Houtum van, H., and R. Bueno Lacy.. 2019. The migration map trap. On the invasion arrows in the cartography of migration. Mobilities ( Online). 1–24. doi:10.1080/17450101.2019.1676031.

- Houtum van, H., and T. van Naerssen. 2002. Bordering, ordering and othering. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 93 (2):125–36. doi:10.1111/tesg.2002.93.issue-2.

- Howden, D., and A. Fotiadis 2017. Where did the money go? How Greece fumbled the refugee crisis. The Guardian, March 9. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/09/how-greece-fumbled-refugee-crisis

- HRW (Human Rights Watch). 2012. Boat ride to detention: Adult and child migrants in Malta. New York: Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/malta0712ForUpload.pdf

- Huntington, S. 1993. The clash of civilizations? Foreign Affairs 72 (3):22–49. doi:10.2307/20045621.

- Huntington, S. 1996. The clash of civilizations and the remaking of world order. New York: Penguin Books.

- Jones, R., . 2017. Violent borders: Refugees and the right to move. London: Verso.

- Juhász, A., and P. Szicherle. 2017. The political effects of migration-related fake news, disinformation and conspiracy theories in Europe. Budapest: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Kemp, R. 2017. Ross Kemp: Libya’s migrant hell. Sky. https://www.sky.com/watch/title/programme/ca063fef-330c-4245-b948-1ea2c8a56570

- King, A., and I. Manoussaki-Adamopoulou 2019. Inside exarcheia: The self-governing community Athens police want rid of. The Guardian, August 26. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/aug/26/athens-police-poised-to-evict-refugees-from-squatted-housing-projects

- Kingsley, P. 2018. ‘Better to drown’: A Greek refugee camp’s epidemic of misery. The New York Times, October 2. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/02/world/europe/greece-lesbos-moria-refugees.html

- Kriesi, H., and T. S. Pappas, eds. 2015. European populism in the shadow of the great recession. Colchester: Ecpr Press.

- Lahav, G. 1998. Immigration and the state: The devolution and privatisation of immigration control in the EU. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 24 (4):675–94. doi:10.1080/1369183X.1998.9976660.

- Laurent, O., and S. O’Grady 2018. Thousands of migrants have been abandoned in the Sahara. This is what their journey looks like. The Washington Post, June 28. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2018/06/28/thousands-of-migrants-have-been-abandoned-in-the-sahara-this-is-what-their-journey-looks-like/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.189e0fba07fb

- Lavenex, S. 2018. ‘Failing forward’ towards which Europe? Organized hypocrisy in the common European asylum system. Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (5):1195–212. doi:10.1111/jcms.12739.

- Lavenex, Sandra. 2006. Shifting up and out: the foreign policy of european immigration control. West European Politics - West Eur Polit 29:329-350. doi:10.1080/01402380500512684.

- Leape, S. 2018. Greece has the means to help refugees on Lesbos – But does it have the will? The Guardian, September 13. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/sep/13/greece-refugees-lesbos-moria-camp-funding-will

- Lefranc, F. 2016. Frans Timmermans: ‘The European project can fail’. Euractiv, November 7. https://www.euractiv.com/section/euro-finance/interview/frans-timmermans-the-european-project-can-fail

- Levy, C. 2010. Refugees, Europe, camps/state of exception: “into the zone”, the European Union and extraterritorial processing of migrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers (theories and practice). Refugee Survey Quarterly 29 (1):92–119. doi:10.1093/rsq/hdq013.

- Lieblich, E., and A. Shinar. 2018. The case against police militarization. Michigan Journal of Race and Law 1 (23):105–53.

- Lucas, A., P. Ramsay, and L. Keen. 2019. No end in sight. The mistreatment of asylum seekers in Greece. Statewatch. http://www.statewatch.org/news/2019/aug/greece-No-End-In-Sight.pdf.

- Lyman, R., and A. Smale 2015. Migrant smuggling in Europe is now worth ‘billions’. The New York Times, September 3. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/04/world/europe/migrants-smuggling-in-europe-is-now-worth-billions.html

- Malik, K. 2019. When refugees in Libya are being starved, Europe’s plan is working. The Guardian, November 30. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/nov/30/when-refugees-in-libya-are-being-starved-europes-plan-is-working

- Mamadouh, V. 2012. The scaling of the ‘invasion’: A geopolitics of immigration narratives in France and The Netherlands. Geopolitics 17 (2):377–401. doi:10.1080/14650045.2011.578268.

- Mau, S., F. Gülzau, L. Laube, and N. Zaun. 2015. The global mobility divide: how visa policies have evolved over time. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (8):1192–213. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1005007.

- Mau, S., H. Brabandt, L. Laube, and C. Roos. 2012. Liberal states and the freedom of movement: Selective borders, unequal mobility. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mbembé, J. A. 2003. Necropolitics. Public Culture 15 (1):11–40. doi:10.1215/08992363-15-1-11.

- McElvaney, K. 2018. Rare look at life inside Lesbos’ Moria refugee camp. Al-Jazeera, January 19. https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/inpictures/rare-life-lesbos-moria-refugee-camp-180119123918846.html

- Metz, C. 1982. The passion for perceiving in psychoanalysis and cinema. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Miller, T. 2019. Empire of borders: The expansion of the US border around the world. London: Verso.

- Minca, C. 2005. The return of the camp. Progress in Human Geography 29 (4):405–12. doi:10.1191/0309132505ph557xx.

- Minca, C., and A. De Rijke 2017. WALLS! WALLS! WALLS! Society + Space. https://societyandspace.org/2017/04/18/walls-walls-walls/

- Mitchell, W. J. T. 2005. Picturing terror: Derrida’s autoimmunity. Cardozo Law Review 27 (2):913–25.

- Mountz, A., and R. M. Kempin. 2014. The spatial logics of migration governance along the southern frontier of the European Union. In Territoriality and migration in the E.U. Neighbourhood: Spilling over the wall, international perspectives on migration, ed. M. Walton-Roberts and J. Hennebry, vol. 5, 85–96. Dordrecht: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-6745-46.

- MSF. 2018. Self-harm and attempted suicides increasing for child refugees in Lesbos. MSF, September 17. https://www.msf.org/child-refugees-lesbos-are-increasingly-self-harming-and-attempting-suicide

- Mudde, C. 2019a. The far right may not have cleaned up, but its influence now dominates Europe. The Guardian, May 28. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/may/28/far-right-european-elections-eu-politics

- Mudde, C. 2019b. Why copying the populist right isn’t going to save the left. The Guardian, May 14. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2019/may/14/why-copying-the-populist-right-isnt-going-to-save-the-left

- Nabert, A., C. Torrisi, N. Archer, B. Lobos, and C. Provost 2019. Hundreds of Europeans ‘criminalised’ for helping migrants – As far right aims to win big in European elections. Open Democracy, May 18. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/hundreds-of-europeans-criminalised-for-helping-migrants-new-data-shows-as-far-right-aims-to-win-big-in-european-elections/

- Neumayer, E. 2006. Unequal access to foreign spaces: How states use visa restrictions to regulate mobility in a globalized World. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 31 (1):72–84. doi:10.1111/tran.2006.31.issue-1.

- Nordås, R., and N. P. Gleditsch. 2007. Climate change and conflict. Political Geography 26 (6):627–38. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2007.06.003.

- Nye, J. S. 2004. Soft power: The means to success in world politics. New York: Public Affairs.

- Plenel, E. 2019. Cette Europe qui nous fait honte. Mediapart, September 12. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/international/120919/cette-europe-qui-nous-fait-honte

- Provera, M. 2015. The criminalisation of irregular migration in the European Union. CEPS, February. https://www.ceps.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Criminalisation%20of%20Irregular%20Migration.pdf

- Rawls, J. 1999. A theory of justice. Cambride, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Reuters. 2015. Slovakia says it prefers Christian refugees under resettlement scheme. Reuters, August 20. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-europe-migrants-slovakia-idUSKCN0QP1HN20150820

- Rijpma, J. J., and M. Cremona 2007. The extra-territorialisation of EU migration policies and the rule of law. EUI Working Paper LAW No. 2007/01 .

- Ruiz Benedicto, A., and P. Brunet. 2018. Building walls. Fear and securitization in the European Union. Barcelona: Centre Delàs d’Estudis per la Pau.

- Said, E. 1997. Covering Islam: How the media and the experts determine how we see the rest of the world. New York: Vintage Books.

- Said, E. 2001. The clash of ignorance. The Nation, October 4. https://www.thenation.com/article/clash-ignorance/

- Said, E. 2006. The essential terrorist. Arab Studies Quarterly 9 (2):195–203.

- Salter, M. B. 2003. Rights of passage: The passport in international relations. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Salter, M. B. 2006. The global visa regime and the political technologies of the international self: Borders, bodies, biopolitics. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 31 (2):167–89. doi:10.1177/030437540603100203.

- Slootweg, A., R. Van Reekum, and W. Schinkel. 2019. The raced constitution of Europe: The eurobarometer and the statistical imagination of European racism. European Journal of Cultural Studies 22 (2):144–63. doi:10.1177/1367549418823064.

- Smith, H. 2018. Lesbos refugee camp at centre of Greek misuse of EU funds row. The Guardian, September 26. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/sep/26/lesbos-refugee-camp-at-centre-of-greek-misuse-of-eu-funds-row

- Smith, H. 2019. Greece passes asylum law aimed at curbing migrant arrivals. The Guardian, November 1. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/nov/01/greece-passes-asylum-law-aimed-at-curbing-migrant-arrivals

- Spijkerboer, T. 2018. High risk, high return: How Europe’s policies play into the hands of people-smugglers. The Guardian, June 20. https://www.theguardian.com/world/commentisfree/2018/jun/20/how-europe-policies-accelerate-people-smuggling

- The Migrants’ Files. 2014. The human and financial cost of 15 years o Fortress Europe. The Migrant Files. http://www.themigrantsfiles.com/

- Theodossopoulos, D. 2016. Philanthropy or solidarity? Ethical dilemmas about humanitarianism in crisis-afflicted Greece. Social Anthropology 24 (2):167–84. doi:10.1111/1469-8676.12304.

- Tondo, L. 2018. ‘We have found hell’: Trauma runs deep for children at dire Lesbos camp. The Guardian, October 3. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/oct/03/trauma-runs-deep-for-children-at-dire-lesbos-camp-moria

- Tondo, L. 2019. Mediterranean will be ‘sea of blood’ without rescue boats, UN warns. The Guardian, June. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/09/mediterranean-sea-of-blood-migrant-refugee-rescue-boats-un-unhcr

- Trilling, D. 2019. How the media contributed to the migrant crisis. The Guardian, August 1. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2019/aug/01/media-framed-migrant-crisis-disaster-reporting

- Turse, N. 2017. The U.S. is waging a massive shadow war in Africa, exclusive documents reveal. VICE, May 18. https://www.vice.com/en_ca/article/nedy3w/the-u-s-is-waging-a-massive-shadow-war-in-africa-exclusive-documents-reveal

- UN. 1951. Convention and protocol related to the status of refugees. UNHCR. https://www.unhcr.org/3b66c2aa10

- UNHCR. 2019. Figures at a glance. UNHCR. https://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html

- UNITED. 2019. List of 36 570 documented deaths of refugees and migrants due to the restrictive policies of “Fortress Europe”. UNITED, April 1. http://www.unitedagainstracism.org/campaigns/refugee-campaign/fortress-europe/

- Vasilopoulou, S. 2009. Varieties of euroscepticism: The case of the European extreme right. Journal of Contemporary European Research 5 (1):3–23.

- Vaughan-Williams, N. 2009. Protesting against citizenship. Citizenship Studies 9 (2):167–79. doi:10.1080/13621020500049127.

- Vaughan-Williams, N. 2015. “We are not animals!” Humanitarian border security and zoopolitical spaces in EUrope. Political Geography 45:1–10. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.09.009.

- Verhofstadt, G. 2018. Europe bribes Turkey. Politico, January 12. https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-bribes-turkey/

- Virdee, S., and B. McGeever. 2018. Racism, crisis, Brexit. Ethnic and Racial Studies 41 (10):1802–19. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1361544.

- Vitkus, D. J. 1997. Turning turk in Othello: The conversion and damnation of the moor. Shakespeare Quarterly 48 (2):145–76. doi:10.2307/2871278.

- Zaiotti, R. 2016. Mapping remote control: The externalization of migration management in the 21st century. In Externalizing migration management: Europe, North America and the spread of ‘remote control’ practices, ed. R. Zaiotti, 3–30. London: Routledge.