ABSTRACT

Background

The implementation of quality standards and measures in the school-based prevention of risk behaviors is not well evidenced in the literature.

Aims

The description of the emergence and implementation of an original nationwide quality management for the prevention of risk behaviors.

Methods

Narrative review from database searches, including gray literature, followed by a subsequent content analysis.

Results

The implementation was divided into six stages characterized by specific activities, measures and concepts given by parameters of the thematic scope and approaches. The driving element turned out to be the changing responses of service providers. It was the response, engagement and the increasing level of providers self-organization that had the greatest effect on development. This interactive process had a major influence on the eventual wide thematic range and scope. It led to establishing of a unique system represented by four components: a certification system and standards for the quality of methods and their delivery to the target group, the monitoring and evaluation of the programs at the school level, qualification standards for professionals, and ethical standards.

Conclusions

Reflection on the implementation of quality management in school-based prevention in the past 20 years may empower similar processes in other countries.

Introduction

In recent decades, prevention science has proven its potential to have a positive effect on health issues that are linked to risk behaviors worldwide, including substance use, by developing and implementing evidence-based prevention interventions (Simon & Burkhart, Citation2021; Sloboda et al., Citation2019).

A systematic review of addiction prevention research (Kempf et al., Citation2017) showed that the main research objectives were predominantly focused on the evaluation of prevention strategies, studies of risk factors, and prevalence studies. Solid evidence of effective substance use prevention interventions was built (Pistone et al., Citation2020). A scientific approach to prevention generated a mix of effective programs, practices, and policies with a focus on key determinants of successful socialization, such as nurturing and safe environments, social norms, parental skills and monitoring, executive and social skills, and impulse control management (Simon & Burkhart, Citation2021; Sloboda et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, the current challenge seems to reside in the process of the implementation of effective programs into prevention practice, and into the functioning of existing services and infrastructures or systems (EMCDDA, Citation2019a; Simon & Burkhart, Citation2021).

Sloboda and David (Citation2021) pointed out the importance of establishing a culture of prevention that is applied in various contexts, including substance use prevention in school settings. One of the reasons for cultivating the culture is that it helps to establish a responsive environment for evidence-based prevention activities and services to be embraced and sustained (Sentell et al., Citation2021). In a certain context, prevention may even be harmful (Moos, Citation2005; Sumnall & Bellis, Citation2007) and a deficit in prevention culture may lead to the misspending of resources on ineffective or harmful prevention strategies. Therefore, developing a quality assurance and control system for prevention aims to avoid exposing people, and in particular young people, to interventions that can be ineffective or even iatrogenic. On the other hand, a quality assurance and control system (quality management) should increase support and enable the funding of evidence-based interventions recognized by such a system of quality (EMCDDA, Citation2019a).

Standards and guidelines represent instruments that enable evidence-based recommendations to be disseminated and implemented and play an important role in quality management (Ferri & Griffiths, Citation2015). Typically, quality standards focus on procedural (e.g., evaluation, documentation, and service planning) and structural aspects of quality assurance (e.g., intervention content, environment, and staffing composition and competencies), and are based upon professional consensus and set by recognized national or international bodies (EMCDDA, Citation2011b; Ferri & Griffiths, Citation2015). The second component of quality assurance is the mechanism by which compliance with the criteria set by the standards is verified. The mechanisms include, for instance, comprehensive quality management in the workplace, internal and external supervision, and peer reviewing, as well as formal mechanisms such as on-site inspection, accreditation, certification, licensing, etc. (Mravčík et al., Citation2010). Generally, quality assurance itself is a part of a quality management system that also includes quality planning, quality control, and quality improvements (Gabrhelík, Citation2015).

The significant advances in prevention science have led to the development of a range of tools to ensure that the provision of prevention is evidence-based and of high quality (EMCDDA, Citation2019a; Renstrom et al., Citation2017). Beside the UNODC International Standards on Drug Use Prevention (UNODC, Citation2015), which enable worldwide implementation, at the European level the European Drug Prevention Quality Standards (EDPQS) have been developed (EMCDDA, Citation2011a). Nevertheless, each of the prevention standards on the international level focuses on a different aspect of the three components of prevention: staff competencies, the design and infrastructure of interventions, and the effectiveness of interventions (Burkhart, Citation2015).

For the purposes of this study, the authors decided to relate to the international and especially to the European context. The data suggest that standards for prevention are widely used across Europe; nevertheless, little is known about their use at the local level. Two-thirds of the countries report on the use of prevention standards with the predominant position of the EDPQS, while Belgium, France, Lithuania, Hungary, the Netherlands, Finland, and the Czech Republic report on the use of their own prevention standards (EMCDDA, Citation2019a). Quality standards became the priority in the EU Drug Strategy 2013–2020, which aimed to improve the quality of drug services and to bridge the gap between science and practice (Council of the European Union, Citation2012). It was followed by a very practical act in terms of developing an integrative version of standards for prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and social reintegration (Council of the European Union, Citation2015). Despite the number of activities, series of projects, and discussions on the topic of quality management (Ferri et al., Citation2018), we can still speak about a lack of real evaluation and comparative studies with a special focus on the daily practices of quality management in drug prevention, as could be seen in the area of treatment.

The aim of the study was to identify and describe the process and background of the development and implementation of an original national quality assurance and control system (quality management) for the school prevention of risk behaviors in the Czech Republic.

Methods

Design

Narrative review documenting the emergence of the nationwide quality system for school-based prevention. The narrative review was prepared according to SANRA (the Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles) (Baethge et al., Citation2019).

Setting

Czech Republic; period from 1999 to 2021.

Information sources

The retrieved literature originated from searches of computerized databases, hand searches, and authoritative texts (Baethge et al., Citation2019; Green et al., Citation2006). The following databases were searched: Academic Search Ultimate, Charles University Central Catalog, EBSCO eBooks, Electronic Journals Library Charles University, Institute of Scientific Information, JSTOR, Kramerius 5, Oxford University, SALIS, Science Direct, Google Scholar, Scopus, Springer, Taylor & Francis, and Web of Science. After the searching key information sources were identified, including gray literature (including unpublished reports, working versions of documents drawn up as part of implementation-related projects, and the available strategic and working documents of participating governmental and non-governmental institutions).

Data collection and content analysis process

After de-duplication and a topic-relevance review of all the abstracts and executive summaries (where present), the remaining texts were selected for further analysis. In the next phase, the data sources were screened, categorized, and systematized. The subsequent content analysis of all the texts was focused on the identification of relevant thematic areas and their content. The following categories were created with the purpose of identifying and describing:

the temporal consecution of the fundamental decisions and steps associated with the concept of a national quality control system and its implementation and logic;

the key stages of the entire process and their relationship with the major factors influencing the development, course, and outcome of a given stage (such as specific projects, institutions, strategies adopted by the government, and associated tasks);

the key milestones in the development of the quality control system and the context of changes in its core concept, and factors that had a bearing on such changes;

the barriers to full implementation and factors that play a critical role and moderate the establishing process to provide a better understanding of this complex process.

One reviewer (MM) screened the titles/abstracts and analyzed the full texts of the identified texts.

Results

Stage 0: To prevent or not to prevent? (1993-1998)

Despite the first national drug policy strategy (Kalina, Citation1993) being adopted shortly after the 1989 Velvet Revolution, the Czech Republic was not able to formulate and implement any detailed and specific strategy for school-based prevention that would be in line with the general drug policy strategy. Prevention was integrated into this document and became one of the four pillars in the context of the emerging national drug policy, which was expressed institutionally in 1995, when the National Drug Commission was officially established; in 2002 it was transformed into the Government Council for Drug Policy Coordination (GCDPC)Footnote1 (Kiššová, Citation2009).

The critical moment for developing the first concept of school-based prevention was the decision made by the Ministry of Education (MoE) that adopted the concept of “social pathology” stemming from the terminology of criminology (Ministry of Education, Citation1998). The prevention of substance use was an integral part of this document but other areas, such as the prevention of bullying, sexual risk behavior, etc., were omitted.

Moreover, any efforts and activities to address topics related to the quality of prevention interventions and prevention professionals failed in the 1990s (Miovský & Van der Kreeft, Citation2002). Both the interventions and the first prevention professionals represented totally new elements in the entire system as no school-based prevention of risk behavior formally existed until the change of political regime in 1989. Throughout the 1990s, none of the ministries assigned by different governments to deal with school prevention (MoE, Ministry of Health, and Ministry of the Interior) was able to complete the task. In fact, inconsistency, poor cooperation, and a lack of coordination became typical of this area. To this day, for example, the line between what is understood by school prevention, health prevention, and crime prevention has not been clearly described and set in the Czech Republic. Neither have the responsibilities of the prevention-specific stakeholders been clarified and defined. All three domains overlapped in the relevant government documents (see, e.g., Ministry of Education, Citation1998; Ministry of Health, Citation1999). This was one of the many reasons for identifying the school prevention of substance use as a major gap and priority for the Phare Twinning 2000 governmental project, which had a critical role and impact on the next phase, Stage I.

Stage I (1999-2004): From the articulation of the need to the first draft of the quality standards

The context of the first stage appears to have been of crucial significance for the initiation and formation of the whole future national system for the school prevention of risk behavior within the general prevention efforts in the Czech Republic and the related notion of quality. The reason is the truly unique role of the above-mentioned Phare Twinning Project 2000: Drug Policy between the Czech Republic and Austria, implemented from 1999 to 2001. For the first time in post-Revolution history, a real needs assessment study was conducted and the state of prevention in the Czech Republic was subjected to a critical and independent evaluation. A number of major shortcomings were ascertained, which were associated with the inconsistent coordination and quality management of school-based prevention (Miovský & Van der Kreeft, Citation2002). In terms of coordination, overseen by the MoE, it was found that there was no single vision of (or umbrella framework for) a coordination system (a description of a functionally interconnected system of prevention activities at all levels)Footnote2 of school prevention, which had probably led to an imbalanced delineation of target groups and a total absence of control measures and any quality policy.

In response to this state of affairs, standards and policy documents were developed by the relevant ministries (e.g., Ministry of Education, Citation2005; Ministry of Interior, Citation2007). Their major drawback, however, was the continuing absence of any relevant school prevention monitoring system and of the practical implementation of evaluation tools. None of the ministries involved was sufficiently aware of what school prevention interventions were provided, where, by whom, and to whom. This was associated with poor quality control and the inefficient management of the whole prevention system (Miovský & Van der Kreeft, Citation2002).

The Phare Twinning Project team responded to this finding by appointing an expert working group comprising representatives of the ministries, prevention providers, and professional organizations with a mandate to develop national quality standards for the school prevention of substance use. The first prototype (Miovský et al., Citation2002) was inspired by the pioneering work of an expert group responsible for the architecture of the national quality standards for treatment and harm reduction in the Czech Republic. This played a vital role in the formation of the approach to quality, effectiveness, and development of the entire system of quality assessment in addictology in the Czech Republic (Kalina et al., Citation2001; Kalina, Citation2000). The first national quality standards were based on three fundamental approaches to quality management in prevention (Miovský et al., Citation2002):

general principles and standards for methods/interventions,

quality standards for providers (organizations/legal entities), including operating regulations, safety, information, etc.,

quality standards for procedures/ways of a specific method/program/intervention being applied, i.e., put into practical use (this procedural aspect is thus another essential criterion).

The standards were articulated and included in the official outcomes of the Phare Twinning Project and recommended by the Czech government for implementation by 2003 (Governmental Statement no. 549 from June 4th). A wide discussion evolved within the relevant professional associations and ministries; however, no specific steps were taken and none of the ministries launched the nationwide implementation into practice.

Stage II (2005-2008): Pilot implementation of the national quality standards

The move to the second stage was initiated by the informal decision of the MoE to implement the school prevention quality standards in practice. In 2004–2005, the leaders of the Phare Twinning Project 2000 working group were addressed and with support from the GCDPC, the previous version of the standards was modified and upgraded, and the new version was officially published (Ministry of Education, Citation2005). At that time, no specific implementation project was conceived to promote the standards and encourage the providers and institutions involved in the school-based prevention of substance use to adopt them. The creators of the standards presumed that they would mainly play a formative role and be disseminated and discussed spontaneously (Miovský et al., Citation2015; Pavlas Martanová, Citation2012b). The previous activities of the service providers appeared to guarantee the continuation of the entire process and the members of the expert group were united in expecting that the service providers would be the main driving force. However, after two years it became apparent that the expectations had not been met. The spontaneous and uncontrolled implementation brought about unforeseen consequences and an imbalance at both the regional and national coordination levels (Miovský, Citation2015; Miovský et al., Citation2015):

with hardly any exceptions, the standards were used in practice only by the providers affiliated with the not-for-profit sector (NGOs), who began to project the requirements into both the interventions and their delivery;

schools (teachers), however, appeared to disregard the standards almost completely and failed to reflect them in their prevention activities, the selection of providers, and the evaluation of the interventions that were carried out. The vast majority of the school staff never became acquainted with the prevention standards and showed no interest in them;

other providers of prevention interventions (those outside the NGO sector), including those from the private sector and the predominant providers (the Police of the Czech Republic and the Municipal Police) completely ignored the school-based prevention quality standards;

at conference-based discussion fora and within expert panels, schools and supporting services (such as counseling centers) began to voice their criticism that the concept of substance use prevention led to an imbalanced approach and failed to take account of other domains of risk behavior, some of which are of comparable concern in epidemiological terms and thus remain unattended to (such as bullying and violence in schools).

These reactions led to changes in the concepts. The concept of social pathology prevention was changed to the prevention of risk behavior, inspired by Jessor’s concept (Jessor et al., Citation1991; Jessor & Jessor, Citation1977). The term risk behavior, which refers to behavior that is evidently conducive to higher health, social, educational, and other risks for the individual and/or the community, was continually integrated into the policy documents. This process also respected the broader context and epidemiology of different kinds of risk behaviorFootnote3 in Czech schools (for more details see, Miovský, Citation2015).

Stage III (2008–2011): Change in the concept and the implementation strategy

Thanks to the first large-scale randomized controlled prevention trial conducted in the Czech Republic (Miovský et al., Citation2011) an expert core of professionals concerned with the theory and practice of prevention (see, e.g., Miovský et al., Citation2004) was formed. The core researchers also became members of the research center, the Center for Addictology, that was established at the First Medical Faculty of Charles University at the same time. Thus, the first two years of the implementation were reflected by experts from various institutions, and, in cooperation with the MoE, the key decision was made to design an EU-funded joint national project dealing with the implementation of the quality standards and other crucial tasks concerning school-based prevention (Miovský et al., Citation2015). This gave rise to the project referred to as “VYNSPI I,”Footnote4 following up closely on the previous process with the involvement of all key institutions, including the MoE. As regards the development of the national quality policy system and its implementation, the VYNSPI I project covered and addressed the following goals:

to reconceptualize the quality standards and extend their scope beyond substance use prevention to cover the area of risk behavior in its entirety (Pavlas Martanová, Citation2012a);

to create a national system for certifying the quality of school prevention providers and the interventions applied: a shift from a formative implementation principle to a normative one, i.e., the development of a methodology for verifying the extent to which the quality standards are fulfilled. In practice, this required specific procedural and technical steps to be defined;

to devise a practical, sustainable, and economical way of institutionalizing the entire process, with the responsibilities and roles being clearly assigned and the emerging certification process solidly grounded in legislative terms;

to create a simple concept and criteria for assessing the qualifications and education of prevention professionals and propose ways of assessing these in practice;

to prepare a concept of a national system for monitoring school-based prevention programs and providers.

All these goals were achieved, and the outcomes were passed on to the MoE, which was responsible for the coordination of prevention, in the 2009–2011 period. The following stage of the implementation of the national quality policy system was launched in 2012 – the description of the subcomponents of the entire system was also officially published in the same year. Key publications were published in Czech and English; these included the general framework for school-based prevention and its infrastructure (Gabrhelík et al., Citation2012; Miovský, Citation2015), the quality standards and related documents covering the certification process (Pavlas Martanová, Citation2012a), the original four-level model for assessing the qualifications and education of prevention professionals (Charvát et al., Citation2012), and robust evaluation studies (Nevoralova et al., Citation2012).

Stage IV (2012–2015): Evaluation of the components of the national system

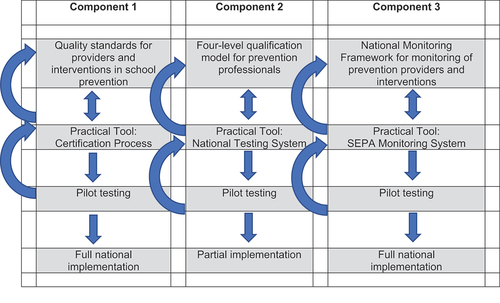

Following the completion of all the tasks of the VYNSPI I project the need for pilot testing arose at this stage. For this purpose, a follow-up project, VYNSPI II,Footnote5 followed up on VYNSPI I. The main objective of VYNSPI II was to pilot the system in five selected regions (out of 14) of the Czech Republic. This resulted in the final division into three quality system components (see, ). From this point onwards these components developed independently of each other (Miovský et al., Citation2015).

Figure 1. Schematic model of the national quality control and management system in school-based prevention in the Czech Republic.

Quality standards for providers and interventions in school prevention (certification system): revised standards extended to cover all types of risk behavior (Pavlas Martanová, Citation2012a) were constantly implemented thanks to the liaison between the MoE and the GCDPC and managed in practical terms by the National Educational Institute, which assumed the role of the certification agency with all the ensuing powers and responsibilities. In addition, certification for quality became a requirement for the providers when applying for certain public funds (both governmental and regional). In practice, however, this requirement was introduced by only some of the providers of financial support: the MoE and the GCDPC at the national level, and the regional financial mechanisms (two cases).

Quality standards for prevention professionals (qualification standards): a unique concept based on a competence approach referred to as the four-level qualification model for prevention professionals was piloted on 100 volunteers among different professions. The testing procedures, the assessment process, and the cost-effectiveness of the entire model were verified in practice (Charvát et al., Citation2012). The limited powers of the MoE appeared to be a major issue with regard to further implementation, as they do not allow the qualifications of health and social professionals to be assessed in practice. In practical terms, thus, the entire system would have to be limited to prevention professionals in the education sector, which would make no sense. Therefore, the team began to look for a different solution, or, in other words, look for ways of incorporating the model into the Czech legislation. Only partial implementation thus took place in the following years (see Stage V), with only some steps forward being taken in selected professions.

National Monitoring Framework for monitoring of prevention providers and interventions (the System of Evidence of school-based Prevention Activities, SEPA): to monitor whether what is being implemented in schools is based on the outcomes of the VYNSPI I project. The technical concept was inspired by the EDDRA quality system (EMCDDA) and the database of prevention programs developed for Serbia (Gabrhelík, Citation2015). This gave rise to an original national monitoring system which is used by elementary and secondary schools to map and evaluate prevention interventions delivered by both in-house education professionals and external providers. SEPA provides a comprehensive overview – on the levels of school, county, region, and nation – of what specific prevention interventions (parameters and classification) are delivered to children in given schools and by whom and when in a given school year. Half of the schools in the Czech Republic use SEPA regularly as the system is used on a voluntary basis. In addition to having a unique overview of the activities delivered to children, the schools can compare their respective prevention-related performance, which makes it a truly original approach to the coordination and synchronization of prevention programs at the level of individual schools as well as regions.

Stage V (2016-2020): Developmental crisis and issues with further implementation

Since Stage IV each of the three components has been developing independently and had its own (often very different) implementation issues and limits. While Component 3 saw its full national implementation at the fifth implementation stage, Component 2, involving quality and prevention professionals’ education, has been implemented only in part. Component 1, addressing the quality standards and certification system, has been fully implemented (see, ). Nevertheless, efforts to have it fully established and consolidated failed and it is thus still at risk. The five years constituting the last phase, Stage V, were marked by the multi-speed national implementation of each of the three components under consideration (see, and ). This was represented by a number of various technical complications, and it seems that under a normative approach, in practice, different areas of the quality policy were inevitably confronted with restrictions imposed by the national framework/context, into which they were being embedded (Miovský, Citation2013, Citation2015).

Table 1. Summary of the key periods in the development of the national school prevention system in the Czech Republic.

First serious crisis with quality standards for providers and interventions in school prevention

The full implementation of the national system proved to be surprisingly smooth and the National Educational Institute, together with the Ministry of Education, ran the entire system successfully. Eventually, the consequences of this system being put into practice became the critical moment.

The segment of profit-oriented prevention providers turned out to be the first major issue. Unlike the not-for-profit sector, they tended to evade the entire system from the beginning or challenged it publicly, e.g., the Revolution Train project based on scare tactics (OSPRCH, Citation2020). Moreover, filing complaints and attempts to discredit and abandon the system for the entire period at the end contributed to the general uncertainty and misgivings about the system. In fact, it cannot be ruled out that the decision of the MoE in 2019 to halt the system temporarilyFootnote6 was motivated by this long-term systematic campaign of impugnment and discreditation. The official explanation of this state provided by the MoE MoE (Ministry of Education/National Pedagogical Institute, Citation2021) refers to legal uncertainty (whether the certification system was legitimate and had appropriate legal grounds). At the time of the publishing of this article, the certification process has not been resumed. The second major issue (closely related to the first one) arose as soon as the first public authorities on a national and regional level began to use the system for the purposes of their funding programs for preventive interventions. For one thing, all these entities were placed under tremendous pressure, as their requirements for the quality certificate dramatically reduced the eligibility for public funding. In addition, it dramatically increased demands for the quality of the interventions and the ways of verifying such quality. This pressure was subsequently multiplied by the fact that other institutions running funding programs for prevention had never embraced the certification process, balked at this step, and did not require quality certification (those included the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Social Affairs).

Partial implementation of four-level qualification model for prevention professionals

The lack of national legislative grounding became a critical issue for the implementation of the quality standards for prevention professionals. There is no formal definition of a prevention professional and, therefore, it is not recognized as an existing autonomous and unique profession or a specialization affiliated with another existing profession. The outcome of the pilot study (see Stage IV) and the attempt to implement its results showed that under the current conditions it is not possible to apply the normative principle in the Czech Republic and neither is it possible to provide any legal grounding. Thus, three different approaches to the implementation process were combined:

to facilitate a public discussion and ongoing promotion activities informing the professional community about the competence model and the four-level qualification model, for example, through the recently established national Professional Association for the Prevention of Risk BehaviorFootnote7 (OSPRCH) and regular national conferences dedicated to prevention;

to advocate the targeted integration of the requirements (knowledge-skills-competencies) into the standards for different professions and specializations); and

to incorporate the national standard into the reference training courses. For example, the adoption of the minimal qualification level for prevention (the basic/minimal qualification level within the four-level model) by means of the INEP online 40-lesson course using the EUPCFootnote8 curriculum.

National monitoring framework for the monitoring of prevention providers and interventions

During the fifth stage of implementation, the SEPA system gained the trust of schools since it was developed both for monitoring and self-evaluation purposes. The SEPA system has been, among other things, gradually cultivated and improved in order to serve schools optimally. In 2020, for example, it demonstrated its viability and strengths in the prompt assessment of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the school-based prevention of risk behavior (Lukavská et al., Citation2021).

In the last three years, there has been general instability in terms of the quality system for prevention. Despite the efforts of the GCDPC in this area, e.g., the issuing of a recommendationFootnote9 to the MoE to restore the quality standards and certification process and give a higher priority to the quality policy and system in prevention, since 2019 the opposite direction has been visible. The halt of the certification processFootnote10 was followed by a reorganization within the Ministry of Education and other governmental institutions (Mravčík et al., Citation2020).

Moreover, even the quality standards and certification process did not lead to a significant reduction of prevention interventions with non-verified quality (provided especially by the private sector and police representatives). These providers thus still enter schools with potentially harmful prevention interventions. Currently, such interventions also receive support from the MoE. One example might be the activities of the DigiCoalition (DigiKoalice) under the Ministry of Education/National Pedagogical Institute (Citation2021) aimed at the prevention of risk behaviors associated with the internet, including internet addiction and cyberbullying. In connection with these activities, there are efforts to put into practice quality control procedures which neither show any signs of a scientific basis nor build on existing quality standards.

Discussion

A modern Czech drug policy began to take shape in the 1990s, following the collapse of the Communist regime. Since the development of the first Czech drug policy strategic document in 1993, prevention has been covered as one of the focus areas. Specifically, the study focused on the key factors concerning the origin and development of stable and sustainable quality management and its parts, reflected on the assumption of the origin of quality management and practical conditions and limits accompanying its real-life implementation, and sought to identify and describe the conditions and possibilities of transferring this 20-year experience into similar processes in other countries and different contexts. Accordingly, it is necessary to better understand the limits and barriers to full implementation of the system and the role of key players and try to identify critical moments for the deeper study of how to implement quality management into the national context and transfer this knowledge. Nevertheless, it has never been the center of attention. Following the development of addiction services, the need to assure the quality of prevention grew over time. Since 2005, a system of certification of professional competence has been developed and implemented with the significant involvement of practitioners. Six developmental stages of the implementation of quality in the school-based prevention environment were identified. These developmental stages, however, do not represent a continuous and linear trajectory from the nonexistence of quality in prevention to fully implemented quality measures that are acknowledged by the professional public as well as the key stakeholders. Despite this, the development was crowned by the establishment of a unique system represented by four core components: (a) a certification system and standards for the quality of methods and their delivery to the target group, (b) the continuous monitoring and evaluation of the provision of programs at the school level, (c) qualification standards for prevention professionals based on a competence model, and (d) ethical standards. Despite the partial successes in the implementation of the core components of the system, the school-based prevention area remains exposed to prevention interventions with non-verified quality and thus to potentially harmful interventions. Nevertheless, the system itself proved to have, to a certain extent, the capability of self-protection and represents a partial barrier to rapid, extensive, and potentially disruptive changes in the prevention system.

Besides the steps already mentioned, there have recently been other projects and initiatives that could be related to prevention. In 2016–2021, a project funded by ESF, Systemic support for the development of addictology services within the framework of the Integrated Drug Policy (RAS), has been running under the GCDPC. The main goal of the project was to design a new structural framework for services and a new integrated system of high-quality, available, and affordable services, built upon a clear embeddedness of competencies in the system of public services and a stable system of funding (Project RAS, Citation2018).

The culture of prevention is expected to build a supportive framework for effective and sustainable strategies and high-quality services and interventions that are beneficial to individuals, communities, and society (Sloboda & David, Citation2021). While there have been numerous materials written on what constitutes quality, there is still a lack of agreement on a universal definition (Vlasceanu et al., Citation2007). Quality is not exactly an abstract concept, but rather an umbrella definition for a spectrum of partial measurable achievements (Ferri & Griffiths, Citation2015). Quality should be reflected in the following domains of school-based prevention: interventions and services, providers, evidence (also called monitoring or data collection), and the management system (which is mainly represented by the decision makers, opinion leaders, and policy makers that operate in a sustainable and financially stable environment).

The developmental stages identified above consist of time periods that could be marked as periods of a creative nature, innovations, and development and periods that could be characterized as rather turbulent and poorly managed by the government. To put it in a different way, the Czech national prevention system seems to be capable of introducing systematic quality management tools while the nationwide implementation and sustainability pose the biggest challenges to the survival of the system. The lesson learned from the case study of the Czech Republic should encourage prevention professionals to take precautious steps that would guarantee greater involvement and dedication of the decision makers, opinion leaders, and policy makers.

Even though much progress has been made in developing evidence-based interventions over the past three decades in Europe, there are still prevention practices with little or no evidence of effectiveness being implemented in community and school settings (Burkhart, Citation2020). Therefore, it is important for prevention practitioners to develop their skills and competences in response to the current evidence being provided by prevention science research (Henriques et al., Citation2019). Aiming to respond to the needs, there are many types of training of professionals, varying from specific courses within university curricula to specialized university programs (Ferri & Griffiths, Citation2015). A recent achievement in the training of professionals is the Universal Prevention Curriculum, which was adapted to the European context (EMCDDA, Citation2019b) and available information indicates its viability by its integration into training and academic programs (e.g., Miovský et al., Citation2019).

The issue of quality has permeated the history of services in the field of addiction in the Czech Republic practically since the beginning, mainly because of the creation of the Standards of Professional Competence. Later on, Standards of Professional Qualifications were developed for the area of prevention. Since then, there has been an effort to maintain and especially develop the system on the basis of current knowledge and evidence. Since 2021, the Czech Republic has been one of the partners in the FENIQS-EU project, supported by the European Commission. The aim of the project was to contribute to the improvement of the process of implementation of quality standards in the area of prevention, treatment and social reintegration, and harm reduction and thus to encourage services to implement quality standards (FENIQS-EU, Citation2021). The participation in the FENIQS-EU project allows us to turn to the past and evaluate what activities have been undertaken in the field of quality. Thorough reflection and evaluation can lead to future initiatives based on evidence and examples of good practice.

The revolution in quality management came with the birth of Total Quality Management (TQM), which is a philosophical concept rather than a system of prescribed criteria (Lukášková & Franková, Citation2007). Until now, many tools and complex systems for quality management have been developed in different areas and for different purposes, especially in the industrial sector, from where their use subsequently reached all conceivable contexts, including healthcare and social services (e.g., ISO, EFQM, QMS). They aim to increase production, reduce costs and errors, attract new partners, fill the client’s needs, improve credit, and, particularly, provide a comprehensive and holistic approach to quality management focused on continuous development (Malík Holasová, Citation2014). Although it may seem that the language of these “tools” is far from the social and health service environment, it is a fact that there is a great source of inspiration on quality management in the industrial and business sector. Maybe this post-pandemic period could be the right time to revise old habits and take an inspiring walk into new areas.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The GCDPC secretariat is part of the Office of the Government and provides drug policy coordination, monitoring of the drug situation, and funding for drug policy programs under the grant scheme; the GCDPD also manages national policy and the system of quality assurance in drug services. While the development of the network of drug services has been coordinated and supported by the GCDPC, the prevention system was subject to rather specific developments.

2. Government Resolution No. 1045 dated October 23 2000, Item No. 5b.

3. (a) bullying and extremely aggressive behavior, (b) substance use prevention, (c) high-risk sexual behavior, (d) extreme sports and risk-taking behavior in traffic, (e) racism and xenophobia, (f) the negative influence of religious sects.

4. Reg. No. CZ.1.07/1.3.00/08.0205

5. Reg. No. CZ.1.07/1.1.00/53.0017

6. Deputy Minister of Education for the management of the education section letter reference number MSMT-22022/2019/1 dated July 1 2019.

7. The professional society was established (legally as an independent NGO) in 2017, inspired by SPR and EUSPR profiles and activities transformed into the national level and context and trying to engage practitioners and support prevention science and practice.

9. Government Council for Drug Policy Coordination Resolution No. 02/0620 dated June 25 2020.

10. Deputy Minister of Education for the management of the education section letter reference number MSMT-22022/2019/1 dated July 1 2019.

References

- Baethge, C., Goldbeck-Wood, S., & Mertens, S. (2019). SANRA—a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Research Integrity and Peer Review, 4(5), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-019-0064-8

- Burkhart, G. (2015). International standards in prevention: How to influence prevention systems by policy interventions? International Journal of Prevention and Treatment of Substance Use Disorders, 1(3–4), 18–37. https://doi.org/10.4038/ijptsud.v1i3–4.7836

- Burkhart, G. (2020). Looking back on 25 years of monitoring prevention in Europe. EMCDDA. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/news/2020/looking-back-on-25-years-of-monitoring-prevention-in-europe_en

- Charvát, M., Jurystová, L., & Miovský, M. (2012). Four-level Model of Qualifications for the Practitioners of the Primary Prevention of Risk Behaviour in the School System [Čtyřúrovňový model kvalifikačních stupňů pro pracovníky v primární prevenci rizikového chování ve školství]. Adiktologie, 12(3), 190–211.

- Council of the European Union. (2012). EU drugs strategy (2013-20). General Secretariat of the Council of EU.

- Council of the European Union. (2015). Council conclusions on the implementation of the EU action plan on drugs 2013-2016 regarding minimum quality standards in drug demand reduction in the European Union. General Secretariat of the Council of EU.

- EMCDDA. (2011a). European drug prevention quality standards: A manual for prevention professionals. Publications Office of the European Union.

- EMCDDA. (2011b). Guidelines for the treatment of drug dependence: A European perspective. Publications Offi ce of the European Union.

- EMCDDA. (2019a). Drug prevention: Exploring a systems perspective. Publications Office of the European Union.

- EMCDDA. (2019b). European prevention curriculum: A handbook for decision-makers, opinion-makers and policy-makers in science-based prevention of substance use. Publications Office of the European Union.

- FENIQS-EU (2021). Further enhancing the implementation of quality standards in drug demand reduction across Europe. Newsletter # 01. https://feniqs-eu.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/NewsletterFeniqs.pdf?utm_source=mailpoet&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=newsletter-01_7

- Ferri, M., & Griffiths, P. (2015). Good practice and quality standards. In N. el-Guebaly, G. Carrà, & M. Galanter (Eds.), Textbook of addiction treatment: International perspectives (pp. 1337–1359). Springer.

- Ferri, M., Dias, S., Bo, A., Ballotta, D., Simon, R., & Carrá, G. (2018). Quality assurance in drug demand reduction in European countries: An overview. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 25(2), 198–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2016.1236904

- Gabrhelík, R., Duncan, A., Miovský, M., Furr-Holden, C. D. M., Štastná, L., & Jurystová, L. (2012). “Unplugged”: A school-based randomized control trial to prevent and reduce adolescent substance use in the Czech Republic. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 124(1–2), 79–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.010

- Gabrhelík, R. (2015). Systém výkaznictví aktivit školské prevence [School-based Prevention Reporting System]. Adiktologie, 15(1), 48–60.

- Green, B. N., Johnson, C. D., & Adams, A. (2006). Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 5(3), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6

- Henriques, S., Broughton, N., Teixeira, A., Burkhart, G., & Miovský, M. (2019). Building a framework based on European quality standards for prevention and e-learning to evaluate online training courses in prevention. Adiktologie, 19(3), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.35198/01–2019-003-0004

- Jessor, R., & Jessor, S. L. (1977). Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. Academic Press.

- Jessor, R., Donovan, J. E., & Costa, F. M. (1991). Beyond adolescence: Problem behavior and young adult development. Cambridge University Press.

- Kalina, K. (1993). Koncepce a program protidrogové politiky 1993–1996 [Drug Policy Concept and Programme 1993–1996]. MV CR.

- Kalina, K. (2000). Kvalita a účinnost v prevenci a léčbě závislostí [Quality and effectiveness in addiction prevention and treatment]. SANANIM.

- Kalina, K., Miovsky, M., & Radimecky, J. (2001). Accreditation standards for facilities and programmes providing professional services to problem users and substance abusers under the responsibility of the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic [Akreditační standardy pro zařízení a programy poskytující odborné služby problémovým uživatelům a závislým na návykových látkách v působnosti MZ ČR]. Phare Twinning Project 2000. Praha: Office of the Government of the Czech Republic.

- Kempf, C., Llorca, P. M., Pizon, F., Brousse, G., & Flaudias, V. (2017). What’s new in addiction prevention in young people: A literature review of the last years of research. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(1131), 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01131

- Kiššová, L. (2009). Czech drug policy and its coordination. EU2009.cz (Zaostřeno Na Drogy), 7(2), 1–12.

- Lukášková, R., & Franková, E. (2007). Řízení kvality v organizacích poskytujících služby: Pojem kvalita a jeho význam [Quality management in organizations providing services: The concept of quality and its meaning]. Trendy ekonomiky a managementu, 1(1), 56–62.

- Lukavská, K., Burda, V., Lukavský, J., Slussareff, M., & Gabrhelík, R. (2021). School-based prevention of screen-related risk behaviors during the long-term distant schooling caused by COVID-19 outbreak. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8561. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168561

- Malík Holasová, V. (2014). Kvalita v sociální práci a sociálních službách [Quality in social work and social services]. Grada.

- Ministry of Education. (1998). Koncepce prevence zneužívání návykových látek a dalších sociálně patologických jevů u dětí a mládeže na období 1998–2000 [Policy document on substance abuse and other social pathology among kids and adolescents for period 1998-2000]. MSMT CR.

- Ministry of Education. (2005). Standardy odborné způsobilosti poskytovatelů programů primární prevence užívání návykových látek [Standards of professional qualifications of the providers of primary prevention programmes in use of addictive substances]. MSMT CR.

- Ministry of Education/National Pedagogical Institute. (2021). Minutes of the 3rd online meeting of the DigiKoalice cyber prevention advisory group of 30 June 2021. Not published.

- Ministry of Health. (1999). Zdraví 21 – Dlouhodobý program zlepšování zdravotního stavu obyvatelstva ČR – Zdraví pro všechny v 21. století [Health 21 - Long-term program for improving the health status of the population of the Czech Republic - Health for all in the 21st century]. MZ CR.

- Ministry of Interior. (2007). Strategie prevence kriminality na léta 2008 až 2011 [Crime prevention strategy for the years 2008 to 2011]. MV CR.

- Miovský, M. (2013). An evidence-based approach in school prevention means an everyday fight: A case study of the Czech Republic’s experience with national quality standards and a national certification system. Adicciones, 25(3), 203–207.

- Miovský, M. (2015). Vývoj národního systému školské prevence rizikového chování v České republice: Reflexe výsledků 15letého procesu tvorby [The development of the National system of school-based prevention of risk behaviour in the Czech Republic: Reflections on the outcomes of a 15-year process]. Adiktologie, 15(1), 62–87.

- Miovský, M., Gabrhelík, R., Charvát, M., Šťastná, L., Jurystová, L., & Pavlas Martanová, V. (2015). Kvalita a efektivita v prevenci rizikového chování dětí a dospívajících [Quality and effectiveness in the prevention of risk behavior among children and adolescents]. (M. Miovský, eds.). Nakladatelství Lidové noviny/Univerzita Karlova.

- Miovský, M., Kubů, P., & Miovská, L. (2004). Evaluation of Addictive Substance Use Primary Prevention Programmes in the Czech Republic: General Background and Application Possibilities. Adiktologie, 4(3), 345.

- Miovský, M., Skácelová, L., & Radimecky, J. (2002). Quality standards for Substance Use Prevention Programes [Standardy kvality programů prevence závislostí]. Task force: School prevention, Component 3: Phare Twinning Project 2000. Praha: Office of the Government of the Czech Republic.

- Miovský, M., Šťastná, L., Gabrhelík, R., & Jurystová, L. (2011). Evaluation of the drug prevention interventions in the Czech Republic. Adiktologie, 11(4), 236–247.

- Miovský, M., & Van der Kreeft, P. (2002). Souhrnná zpráva Analýzy potřeb v oblasti primární prevence užívání návykových látek. Pracovní skupina: Primární prevence, Component 3: Phare Twinning Project “Drug policy.” Příloha č. III/1/1 Závěrečné zprávy č. III/1. Retrieved from Praha: Office of the Government of the Czech Republic.

- Miovský, M., Vondrová, A., Gabrhelík, R., Sloboda, Z., Libra, J., & Lososová, A. (2019). Incorporation of universal prevention curriculum into established academic degree study programme: Qualitative process evaluation. Central European Journal of Public Health, 27(88), S74–S82. https://doi.org/10.21101/cejph.a5952

- Moos, R. H. (2005). Iatrogenic effects of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders: Prevalence, predictors, prevention. Addiction, 100(5), 595–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01073.x

- Mravčík, V., Pešek, R., Horáková, M., Nečas, V., Škařupová, K., Šťastná, L., … Zábranský, T. (2010). Annual report. The Czech Republic 2009 drug situation. Office of the Government of the Czech Republic.

- Mravčík, V., Chomynová, P., Grohmannová, K., Janíková, B., Černíková, T., Rous, Z., … Vopravil, J. (2020). Výroční zpráva o stavu ve věcech drog v České republice v roce 2019 [Annual Report on Drug Situation in the Czech Republic in 2019]. Office of the Government of the Czech Republic.

- Nevoralova, M., Pavlovska, A., & Stastna, L. (2012). Evaluation of the school-based primary prevention of risk behaviour in the Czech Republic. Adiktologie, 12(3), 244–255.

- OSPRCH. (2020). Společné stanovisko odborných společností k projektu revolution train [Joint opinion of professional companies on the revolution train project] [Press release]. https://www.osprch.cz/images/dokumenty/Train_stanovisko2020.pdf

- Pavlas Martanová, V. (2012a). Development of the standards and the certification process in primary prevention - an evaluation study. Adiktologie, 12(3), 174–188.

- Pavlas Martanová, V. (2012b). Development of the standards and the certification process in primary prevention an evaluation study [Vývoj Standardů a procesu certifikace v primární prevenci evaluační studie]. Adiktologie, 12(3), 174–188.

- Pistone, I., Blomberg, A., & Sager, M. (2020). A systematic mapping of substance use, misuse, abuse and addiction prevention research: Current status and implications for future research. Journal of Substance Use, 25(3), 231–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2019.1684583

- Project RAS. (2018). O projektu RAS [About RAS project]. Office of the government of the Czech Republic. Retrieved from https://www.rozvojadiktologickychsluzeb.cz/

- Renstrom, M., Ferri, M., & Mandil, A. (2017). Substance use prevention: Evidence-based intervention. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 23(3), 198–205. https://doi.org/10.26719/2017.23.3.198

- Sentell, T. L., Ylli, A., Pirkle, C. M., Qirjako, G., & Xinxo, S. (2021). Promoting a culture of prevention in Albania: The “Si Je?” program. Prevention Science, 22(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0967-5

- Simon, R., & Burkhart, G. (2021). Prevention Strategies. In N. el-Guebaly, G. Carrà, M. Galanter, & A. M. Baldacchino (Eds.), Textbook of addiction treatment (pp. 73–89). Springer.

- Sloboda, Z., Petras, H., Robertson, E., & Hingson, R. (2019). Prevention of substance use. (Z. Sloboda, H. Petras, E. Robertson, & R. Hingson, Eds.). Springer.

- Sloboda, Z., & David, S. B. (2021). Commentary on the culture of prevention. Prevention Science, 22(1), 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01158-8

- Sumnall, H. R., & Bellis, M. A. (2007). Can health campaigns make people ill? The iatrogenic potential of population‐based cannabis prevention. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 61(11), 930–931. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2007.060277

- UNODC. (2015). International Standards on Drug Use Prevention. United Nations. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/prevention/prevention-standards-first.html

- Vlasceanu, L., Grunberg, L., & Parlea, D. (2007). Quality assurance and accreditation: A glossary of basic terms and definitions. UNESCO-CEPES.