ABSTRACT

Establishing the English Premier League has resulted in a dramatic rise in commercial activities, raising public health concerns around unhealthy brand marketing. The present paper deals with three linked case studies analysing the marketing techniques of three of the Premier League’s partners in the 2019/20 season: Coca-Cola, Budweiser, and Cadbury. Data from Twitter were triangulated with promotional materials, product promotions in supermarkets and grey literature. An inductive thematic analysis explored the strategies used to engage fans. The studies show sponsors purchasing access to fans and inserting their brands into the emotional and passionate environment of EPL football. Sponsors evoke cultural traditions to align with and engage fans, to encourage consumption. Consumption is ’responsibilised’ and positioned as an individual choice. The marketing techniques identified exploit social and cultural dimensions of EPL football to increase consumption of unhealthy brands, with the potential to negatively impact on the health of the EPL’s audience.

Introduction

The transformation and commodification of football which accompanied the launch of the English Premier League (EPL) in 1992 made football fans into communities of international consumers. The huge broadcasting deals accompanying subscription television contracts together with commercial sponsorship transformed English football.Footnote1 Today, EPL football with its billions of followersFootnote2 across the world makes English football an attractive proposition for corporations who want their brands to stand out in a global marketplace.

The health harms caused by industrial epidemics of unhealthy commoditiesFootnote3 are spread by transnational corporations (TNCs) using global markets. As an international product, the EPL reflects these neoliberal social and economic developments.Footnote4 Studies both in the UK and in Australia have raised concerns that unhealthy marketing messages fill our sports stadiumsFootnote5 and events such as the European Football ChampionshipsFootnote6 and the Olympic GamesFootnote7 have been highlighted.

The brands promoted through sport include foods and beverages high in fats, sugars and/or salt (HFSS) and alcohol, raising concerns about the potential health impact of the commercial partnerships and corporate practices now prevalent in sport and the content that children are exposed to through these.Footnote8 The marketing of these brands aims not only to increase consumption but also to influence attitudes and social norms.Footnote9 The EPL enables promotion of unhealthy brands through its partnership practices of having official soft drink, snack and alcohol partners. These partners use marketing and communication processes to engage with football fans (brand activation) and promote unhealthy consumption at a time when the global burden of non-communicable diseases is growing, driven in part by the consumption of products high in fat, sugar and salt (HFSS).Footnote10

This research seeks to understand how unhealthy brands build relationships with football’s consumers through marketing. As far as the researchers are aware, this is the first application of a comprehensive approach to examining unhealthy brand engagement marketing processes in sport. Other studies have focused on the volume of the marketing of individual harmful commodities in sport such as food and drink brands,Footnote11 alcoholFootnote12 and gambling.Footnote13

Sport sponsorship

In writing about the World Cup held in France in 1998, Pierre Bourdieu described the process of commercialization in football and of ‘Sport visible as spectacle hides the reality of a system of actors competing over commercial stakes’.Footnote14 In this, as in education and art,Footnote15 Bourdieu provides an explanatory model which considers sport as an economic process in which economic exchange represents relations of power and distribution of capital. As Bourdieu illustrated, TNCs are using their economic capital to purchase visibility and build cultural capital.Footnote16 TNCs leverage this economic capital, which is sought after by clubs and leagues to compete in markets in which costs are high, inserting themselves into football’s social networks and cultural practices. These corporations then want to see a return on their investment which is usually measured against brand awareness and, if possible, product sales. They typically supplement their sponsorship with related marketing activities which may cost more than the sponsorship itself.Footnote17

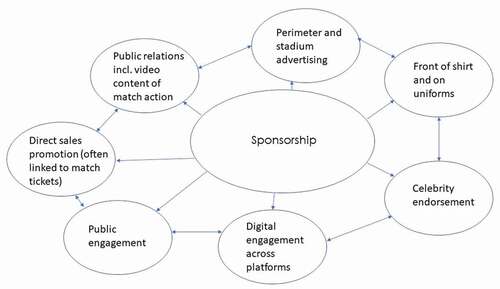

Marketing literature emphasizes that for sport sponsorship to be successful for companies, it needs to be mixed with other promotional tools.Footnote18 Marketeers use a number of methods to ‘activate’ their brand with these illustrated in linking strategies as shown in .

Figure 1. The sport sponsorship mix in the English Premier League.Adapted from (Bűhler and Nufer Citation2013, p.99).

Cornwell argued that sponsorship is more successful than traditional advertising due to its potential to influence consumer engagement. Engagement, in this sense, directly involves the consumer in a relationship with a brand which can be a form of emotional bonding.Footnote19 Meenaghan has provided a framework for understanding the effects of commercial sponsorship on consumers arguing that the central tenets of sponsorship effects are goodwill, image transfer and fan involvement.Footnote20 Fan involvement is defined as the extent to which consumers identify with, and are motivated by, their engagement and affiliation with their chosen activity. Thus, TNCs build perceptions of brands with fans through consumer engagement and participation strategiesFootnote21 designed to build trust, create loyalty, and drive consumption and profitability.Footnote22

Methods

Design

Sponsorship arrangements are complex and are individually negotiated. A multiple case study approach has therefore been taken in this study of brand engagement and sponsorship activation in the EPL. The data are presented as discrete case studies enabling a detailed analysis and in-depth exploration of the complexity of the arrangements.Footnote23 The differing marketing strategies of each brand are described, focusing on the methods identified to engage fans, improve perceptions of brands, and encourage consumption. In each study, the case was considered unique,Footnote24 and examined for characteristics of brand engagement between the sponsor, the sponsee (Premier League) and fan-consumer. Data from Twitter and other digital sources were triangulatedFootnote25 with promotional materials including press releases, football match programmes, product promotions in supermarkets, together with grey literature when this was available.

Case studies

This study considers the unhealthy sponsorship partnerships of the EPL. In the 2019/20 football season the EPL was official partners with Cadbury, its ‘Official Snack’, Budweiser, ‘Official Beer’, and Coca-Cola as ‘Official Soft Drink’.Footnote26 These partnerships may not be representative of all sport sponsorship practices within the EPL but may be considered illustrative and provide an insight into how brands seek to build relationships with fan-consumers, as well as fit our focus on unhealthy commodities. Coca-Cola launched their three-and-a-half-year partnership with the Premier League on 7 February 2019, Cadbury (owned by Mondelez International) was the ‘Official Snack’ of the EPL between 2017 and 2020. Budweiser (part of Anheuser-Busch InBev) became the ‘Official Beer’ of the Premier League in July 2019.

Procedure

Data gathering took a similar approach for each case study but was also impressionistic, that is flexible, opportunistic, and open to identifying a range of examples from many different sources.Footnote27 In each of the studies, a simple search technique using the specific three brand names (Coca-Cola, Cadbury and Budweiser) was adopted using Google and Google Scholar to identify mentions of these brands in connection with football and the EPL in grey literature and in media such as online newspapers and other industry-related websites. Searches were structured using the date on which each sponsorship started.

Twitter was used as a platform to explore social media data used by sponsors and sponsees which promote the brands and thus encourage consumption of their associated products. The micro-blogging site is considered as a good platform by corporations for engagement with potential consumers because of its ability to identify interests through retweets and hashtags that an individual shares.Footnote28

The searches on Twitter for each of the linked case studies were determined by the marketing methods used by the brand and reflecting the use of hashtags and brand Twitter accounts where these were employed. The social media searches are described briefly in the sections below to distinguish between the approaches used by each brand. Data used in this study did not include audience reception data, as we were focused on engagement techniques as deployed by the three EPL sponsors.

Data capture/collection

The Social Media Research Foundation’s NodeXL Pro application was used to capture tweets initially and to explore digital activation by sponsors, sponsees and fans. NodeXL is a network data capture, analysis and visualization package which works with Microsoft Excel 2016. Searches were carried out on the principal brand accounts with hashtags when identified using the Import function from the Twitter Search Network to show who was replied to or mentioned in recent tweets. Twitter limits searches to 18,000 tweets. Search results are not complete in that Twitter’s search algorithm focuses on what it considers relevant (thus Twitter determines what is included). NodeXL searches use this algorithm which provides tweets posted up to 10 days before the date of the search. NodeXL searches were supplemented by manual browsing of accounts and hashtags to reduce risk of missing important tweets not provided by the searches. Tweets identified this way were captured using screenshots and stored as PDFs. In all the searches undertaken, both visual and textual data were captured. Data from online searchers of grey literature, online newspapers and other websites were stored as PDFs and website links and filed by brand.

Data analysis

The NodeXL datasets were sorted by account and hashtags using Excel’s filter function. Tweets captured as PDFs were read and viewed alongside data in the filtered NodeXL datasets, as well as the PDF data collected via web searches. In each study, these data were read and re-read to inductively generate an analysis of the characteristics of brand engagement between the sponsor, the sponsee (Premier League) and fan-consumer. Analysis thus followed an inductive thematic procedureFootnote29 identifying common features within and across the three brands’ use of their strategic partnerships with the EPL. Each of the linked case studies is first presented descriptively before we consider the themes generated when looking across the case studies in the discussion section.

Results

Coca-Cola

NodeXL was used to extract 3,200 tweets from the official Twitter account for Coca-Cola GB (@CocaCola_GB) which had 149.7 K followers on 28 January 2020 (the date of extraction). The strapline ‘Where Everyone Plays’ featured prominently on the account profile picture and a search was then used for this hashtag and variations such as #WhereEveryonePlaysPremierLeague. Fifteen tweets were obtained.

The press announcement of Coca-Cola’s sponsorship of the Premier League was accompanied by a tweet which introduced Coca-Cola’s marketing strapline with a link to a 90 second film ‘Where Everyone Plays’.Footnote30 The film featured fans from all the clubs in the EPL at that time. It used a catchy tune, ‘Only You’ by Yazoo, with the lyrics:

All I needed was the love you gave

All I needed for another day

And all I ever knew

Only you.

The full lyrics of Yazoo’s song can be interpreted in different ways but may be seen as a love song referring to a deep and emotional relationship. Coca-Cola evoke the sentiment of a love never lost and seek to engage with the level of commitment and passion that football fans feel for their club, which is often entwined with community identity.Footnote31

The video and song are an attempt by Coca-Cola to connect fan emotion and passion with their brand and products. It is an example of how affect transferFootnote32 (or ‘image transfer’ as MeenagahanFootnote33 described it) may enable the positive feelings generated by the film to be transferred to Coca-Cola through association. The video provided regional and historical references to evoke football traditions including a Mersey Ferry, Chelsea Pensioners, and a clip of fans’ football banter over fish and chips. In the 90 seconds, there are 17 images of Coca-Cola cans and bottles. Coca-Cola continued with using this film and edited highlights of it across the two football seasons considered.

The company used carefully chosen references to the cultural heritage of each club in the EPL. Coca-Cola GB’s tweet on 5 August 2019 was simple and direct: ‘This season, let’s make it a game #WhereEveryonePlays’ (the first match of the EPL 2019/20 season was Liverpool versus Norwich City on 9 August). The launch video was edited to add references to the three promoted clubs including Norwich City fans finding a talking image of Delia Smith (the club’s major shareholder and celebrity cook) in their fish pie, repeating a famous moment in the club’s history when she took to the field at half time in an attempt to rouse the fans, using the phrase ‘let’s be having you’. Similarly, the scene in which an all-male group of West Ham fans, gathered in a snooker hall and declaring that ‘we’re West Ham, we ain’t singing’ draws on historical representations of the club’s ‘firms’ known for their violence and heavy drinking, as depicted in the 2005 film Green Street Hooligans.

Coca-Cola’s video, produced by specialist marketing agency M&C Saatchi, is a masterpiece of cultural references, a ‘proper, flag-waving, badge-kissing crowd-pleaser’.Footnote34 The short film skilfully uses an emotive memory or image from every club, appropriating and instrumentalising each club’s cultural capital, which can then be used and referenced once again in smaller edits. On the opening day of the new season, a ten second edited version of the same film was tweeted with fans chanting to the background of the synthesized chorus line of ‘Only You’. This received an astonishing 5.7 M views. The excitement levels at the start of every football season are intense amongst fans with high hopes for their clubs. Each of the film edits targeted fans with a specific form of familiarity linked to the cultural heritage of their clubs.

Coca-Cola GB’s tweets referencing the Premier League were few and were well spaced out, based around their use of films as described. Two of Coca-Cola’s films highlighted the company’s social responsibility programme building goodwill.Footnote35 On 22 July 2019, a tweet included a one minute twenty seconds film promoting Coca-Cola’s relationship with registered charity, Street Games UK. The text in the film included ‘we’re helping communities to access pitches’ and a sign referencing young people’s hatred of signs which forbid them to play games at the same time as linking to the drink brand. The text accompanying the film also stated that Coca-Cola will donate £200,000 to Street Games. The film received 28.4 K views.

Cadbury

Cadbury was signed as the Official Snack Partner of the Premier League in a three-year deal from 2017 to 2020 declaring, ‘Cadbury wants to bring the Premier League to consumers for them to share in the moments of excitement that football brings’.Footnote36 Brand activation was explicit from the start, with the following promised to football fans in its publicity material including on the Cadbury website:

The chance to win matchday tickets;

Opportunities to meet Premier League stars past and present;

Support for the Premier League Primary Stars programme;

Golden Boot, Golden Glove and Playmaker awards at the end of the season.

From this launch content, Cadbury, like Coca-Cola, were keen to associate their brand with the passion of football, to benefit from the anticipated brand transfer affect, by using their economic capital to purchase a bridge to the social capital amassed by the EPL and its clubs. By buying Cadbury’s products, football fans could directly engage with their club with the opportunity of tickets to matches and stadiums together meeting with meeting players. The awards provided further opportunities for fan involvement particularly through social media interactions, and represent a direct insertion of the Cadbury brand into a competitive element of the EPL.

NodeXL was used to extract 3,200 tweets from the official Twitter account for CadburyUK which had 303 K followers on 28 January 2020. However, unlike Coca-Cola, there does not seem a hashtag that Cadbury use concerning the Premier League. In using Twitter therefore as a method to test engagement between brand and fans, 90 tweets from the main Cadbury UK Twitter account were examined simply by scrolling back through the account. We captured all tweets from the formal launch of Cadbury’s sponsorship of the EPL on 11 August 2017 (the beginning of the 2017/18 season) and continued through to 31 January 2020.

Of the 90 tweets captured and analysed, 26 refer to Cadbury’s partnerships with a number of charities, 24 to generic Cadbury product or sales promotion, and 19 to Cadbury’s partnership with the EPL (either direct tweets from CadburyUK or retweets from the Premier League Twitter account). The remainder are on a mix of topics. On 10 October 2019, Cadbury FC launched a promotion with the EPL. The customer could buy a ‘participating Cadbury product’, visit the Cadbury FC website where they could enter a barcode and batch code and receive a randomized match score prediction. If their predicted score came up, they won ‘VIP matchday experiences’, pairs of match tickets and club shop vouchers of between £5 and £10 (the most popular). A 15 second film was used by Cadbury to promote ‘Match and Win’ featuring ex Arsenal FC legend, Thierry Henry, and linked to Cadbury’s products. The film received 4.8 K views.

On 27 January 2020, a six-second film made a direct link with the Cadbury Dairy Milk product. As also described on the Cadbury FC webpage, if you purchase a chocolate bar and ‘find a shiny’, this gives you an opportunity to ‘win an experience with a Premier League Legend’. The six-second film shows a young woman on a supermarket checkout and a sound as the item (presumably a chocolate bar) is scanned.

shows Cadbury’s products in UK supermarkets. Cadbury have directly linked their promotions and their commercial partnership with the EPL to drive consumption of their chocolate bars. The Dairy Milk bar photographed shows the ‘Match and Win’ logo providing an opportunity to match a code on the wrapper with the chance to ‘Win VIP Matchday Experiences Plus 1,000,000s of Other Prizes Available’.

Cadbury UK retweeted @OfficialPanini (23.7 K followers in February 2020) on 14 June. An 18 second video linked in a tweet promoted Cadbury player award winners who were then featured in the Premier League Panini Tabloid Sticker Collection. Panini is an Italian company who produce trading cards and other collectables. The use of stickers is popular amongst children, as with the cigarette cards of the twentieth century, and their use here links Panini closely with Cadbury. This is a strategy benefitting both Cadbury and Panini which engages with and reinforces consumption amongst children. Cadbury’s partnership with Panini enabled the brand to insert itself into a long-established tradition of fans collecting cards featuring players and now stickers in the modern day. Cadbury FC also has its own Fan Club in which membership enables fans to win match tickets and provides a database for Cadbury. Football has its own tradition of supporters’ clubs and Cadbury is trying to tap into this concept of football and brand loyalty.Footnote37

Cadbury sponsored a series of awards during their partnership with the EPL featuring numbers of player appearances, ‘Playmaker Award’ (players recognized for their creativity in creating chances for other players to score goals), most successful goalkeepers (Golden Glove award) and goalscorers (Golden Boot). This enabled Cadbury to regularly show images of players which fans would identify with. At the same time, all these images were carrying the Cadbury logo together with that of the Premier League using the purple colour of Cadbury’s chocolate wrapper, a colour traditionally associated with imperial majesty and now suggesting luxury and status whilst encouraging consumers to treat themselves.Footnote38

Cadbury UK also retweeted @premierleague on 12 May promoting Cadbury’s Playmaker Award. A 35 second film showcased Eden Hazard of Chelsea FC, highlighting the Cadbury brand received 278.5 K views. The highest number of viewers came with the Golden Boot award which was won by three players who all scored 22 Premier League goals in the 2018/19 season. The 35 second film accompanying the tweet and the award had 555.4 K views. Cadbury UK announced their partnership with the Premier League for the 2018/19 football season on 14 August 2018 with another 11 second film featuring Jamie Redknapp. This received an incredible 4.2 M views.

As with the other Premier League partner brands, Cadbury used their association with the League to promote their products (via Mondelez International) globally. ‘Joy Schools’ is an initiative by Mondelez International (Malaysia) ‘which empowers people to snack right’ (by promoting Oreo, Cadbury Dairy Milk and other brands).Footnote39 Joy Schools was established in 2011 by Mondelez across Southeast Asia and was described as a community investment initiative. Mondelez International’s press release of 2019 featured ex-Premier League football and England ‘legend’, Michael Owen, taking part in a football school in Malaysia whilst promoting the Cadbury brand.Footnote40 Like Coca-Cola, Cadbury are using their link with the Premier League to promote goodwill through a corporate social responsibility programme.

Budweiser

The announcement that Budweiser would become the official beer of the Premier League was made in July 2019. By partnering with both the EPL and La Liga in Spain, Budweiser hoped to reach fans across five continents ‘through a series of unique programmes across the globe’.Footnote41 The launch on 23 July 2019 was supported by a tweet from the Premier League’s official Twitter site. The accompanying 30 second film featured a young male fashionable street rap, ‘Make Way for the King’ (artist: Ohana Bam, 2019). The film used images from Premier League matches and promoted the ‘Be a King’ slogan. It received 63.6 K views and 1.2 K likes.

All the brands in the case studies operate globally. In India, Budweiser used mainline and digital advertising and fan parks with screenings of the EPL to keep fans engaged and to enjoy the excitement around matches.Footnote42 A similar approach was used in Nigeria where the brewing company organized viewing parties and teamed up with local celebrities to promote their beer alongside footballFootnote43 together with launching a Kings of Football show on Nigerian television.Footnote44

NodeXL was used to extract 3,200 tweets from the official Twitter account for Budweiser UK which had 20.4 K followers on 28 January 2020 (the date of extraction). The strapline ‘Beer of Kings’ featured prominently on the account profile picture and a search was then used for this hashtag and variations including #kingsofthepremierleague. Ninety-five tweets were identified and considered. The majority of the data captured was before Budweiser’s sponsorship of the EPL was announced in July 2019.

The media images used in Budweiser UK’s tweets were of a shared fun and camaraderie as employed in the GIF (Graphics Interchange Format) first observed in a tweet on 16 June 2018 and shown in , ‘Made for Sharing’. As a GIF, the tweet encourages sharing of the image as well as the beer. There is a small link in the figure provided to drinkaware.co.uk (to ‘encourage’ ‘responsible drinking’). As with Coca-Cola, Budweiser uses films which capitalise on the excitement and passion of football match-play to elicit fan engagement.

There were 29 tweets by BudweiserUK after July 2019 (after their sponsorship of the EPL commenced) featuring hashtags. These fell into two categories. The first was interactions with fans who mention the beer brand. The second category used short films of around 45 seconds which featured action from the Premier League matches and a highlight on individual players using the #BeerOfKings hashtag. From 27 September 2019, Budweiser launched a new campaign with the subscription broadcaster, Sky Sports. A short film (28 seconds) presented players from each Premier League team, linked to a specific Sky Sports programme and launched ‘Kings of The Premier League’ using both this as a hashtag and the abbreviated #KOTPL. This film received 30.6 K views. On 30 September 2019, Budweiser tweeted that the Kings ofThe Premier League show is carried in full on Sky Sport’s You Tube channel.

The 47 second film tweeted on 18 October 2019 with Premier League action received only 318 views. However, the tweet by Sky Sports linked with Budweiser (using the #BeerOfKings and #KOTPL hashtags) on 1 November had a much bigger audience of 64.5 K views. The remaining tweets from BudweiserUK were all either responses to other tweets tagging #KingOfBeers or more short films which never received more than 400 views (at the time of analysis). On 10 January 2020 however, the last tweet obtained, another approach is used. A one-minute video shows Tottenham Hotspur’s Son Heung-Min’s Premier League’s Goal of the Month winner for December 2019. The film includes not only the goal but also an interview of Son by Layla Anne-Lee from ‘Bud Football’. This approach was very successful and received 23.5 K views.

Discussion

As has been shown, modern football has become a core component of a global culture industryFootnote45 in which the brands of TNCs have colonised the EPL. Sporting culture has been indiscriminately mined to promote corporate brand values and the consumption of unhealthy commodities, with corporations exchanging their economic capital for access to the social capital of the EPL and its clubs.Footnote46 The EPL have worked with their category partners so that sponsorship is perceived as a win–win situation. The economic investment by the sponsor is seen as of benefit to the sport and the findings in this study shows the EPL supports brand activation and engagement with fan-consumers illustrating all elements of the sport sponsorship mix.Footnote47

The digital strategies adopted demonstrate increasingly sophisticated brand engagement techniques. All show unhealthy commodity industries using a mixture of marketing methods, in association with the EPL, to promote consumption. Football fans form a global base estimated at three billion,Footnote48 and the digital revolution provides ever more ways for corporations reach consumers and attempt to build brand loyalty and consumption through brand engagement. This marketing impacts on awareness of brands, intended consumption and behaviourFootnote49 and is likely to impact on adverse health outcomes.Footnote50

Evoking tradition, authenticity and excitement

Tradition is a key component of English football. Brands work on sponsorship engagement models that draw on ideas about authenticity and they position themselves carefully to tell a story based on football’s history.Footnote51 This was particularly prominent in Coca-Cola’s ‘where everyone plays’ campaign, which skilfully wove together targeted references to club-specific histories, e.g. Delia Smith’s famous ‘let’s be having you’ speech, demonstrating an appropriation of aspects of each club’s cultural capital as part of the engagement strategy.

Football-related marketing positively influences brand user engagementFootnote52 and helps to transfer the positive emotions aroused by football, described by Elias and Dunning as the ‘quest for excitement’,Footnote53 onto a brand.Footnote54 The approach taken by Cadbury and Budweiser was to attach their brands to this excitement by using footage and sponsoring key season-long awards. Football’s strong relationship with media outlets has enabled it to develop and maximize its relationship with marketing by guaranteeing that their sponsorship will be wrapped up in the excitement, passion and cultural traditions which is captured and covered by multiple media outlets.Footnote55

The brands described have worked hard to identify themselves with these rich traditions and accompanying passions. Sandvoss argued that many football fans consider fandom as ‘an integral part of their personality’, and Robson’s study of Millwall fans offers insight into the deep-seated connections fans make with their club in relation to their community.Footnote56 Our study clearly demonstrates that the selected EPL partners are attempting to use their economic capital to access and integrate with the social, cultural and emotional foundations of football to drive brand engagements and, ultimately, consumption of their products.

Masculinities and football

Despite the transformation of football in the modern era, the prevailing marketing approach in the EPL would appear to be aimed at male fans with studies considering gambling marketing illustrating this.Footnote57 Historically, Sugden and Tomlinson wrote that global sponsorship of football has been based around male consumption: ‘drinking, snacking, shaving, driving’.Footnote58 Cortese and Ling described how the tobacco industry used cultural constructions of masculinity as ‘both a vehicle and a product of consumption’.Footnote59

This was evident in the approach taken by Budweiser, which regularly invoked the concept of the ‘king’ in its strategies. To drink Budweiser was positioned as an act of becoming a ‘king’, of consuming the ‘king of beers’, evoking traits of power and authority. These ultra-masculinized traits where then also projected onto players themselves through the ‘kings of the premier league show’ produced in association with Sky Sports. Similarly, in Coca-Cola’s ‘where everyone plays’ film, West Ham fans are characterized with implicit reference to ultra-masculine traits of violence and excess alcohol consumption, evoked via their appearance as an apparent ‘firm’ that ‘aint singing’.

Corporations have an interest in promoting risky behaviour as a masculine traitFootnote60 whether this applies to tobacco consumption, alcohol use or gambling. Messner and Montez de OcaFootnote61 described the way in which sports advertising draws on tropes of masculinity to encourage consumers to think of their products as an essential part of a stylish and desirable lifestyle. The case studies of both Budweiser and Coca-Cola’s engagement strategies echo these findings and demonstrate their continued relevance.

The language of individual responsibility

Corporate practices promote the consumption of unhealthy commodities through their marketingFootnote62 and any attempts at curtailing the operation of free markets is commonly positioned as unnecessary regulation.Footnote63 The dominant neoliberal discourse argues that people are responsible for their health and are blamed for their consuming practices.Footnote64 Maani et al. argued that whilst the use of unhealthy commodities is strongly influenced by factors such as availability and advertising as part of a marketing mix, the focus in health policies is on individual ‘lifestyles’.Footnote65

In the brand marketing considered in the EPL case studies, an occasional sugary drink, snack, or beer is argued as hardly likely to affect health and indeed, all these activities should be seen as fun according to the marketing messages. In the findings, Budweiser linked to the Drinkaware website and talked of drinking responsibly whilst Cadbury (Mondelez International), of snacking ‘right’. The emphasis is placed on individual responsibility and ignores the exposure to the marketing activities of the brands featured in these case studies and the group-identity that they help to create. Such framing detracts attention from the systemic production of harm, and positions itself as a matter of individual consumption, in ways that benefit the status quo. This is an example of what Rose refers to as ‘responsibilisation’, which describes the process through which structural features of social life are obfuscated by discourses framed in individualizing terms.Footnote66

Corporate social responsibility

TNCs are taking increasing steps to present themselves as good corporate citizens with sports sponsorship sometimes considered part of a global corporate social responsibility (CSR) programme.Footnote67 As Cornwell has noted, industries including tobacco, alcohol, gaming and fast food have all received criticism for their sport sponsorship programmes with a central concern being these sponsored activities reach youth audiences.Footnote68 Nestle argued that ‘Big Soda’s’ tactics of investing in sponsorships and worthy causes enhances a company’s credibility, gains brand loyalty and neutralizes critics.Footnote69 In the case study, Coca-Cola demonstrated their support of Street Games UK, a registered charity, whose website declares that the organization ‘harnesses the power of sport to create positive change in the lives of disadvantaged young people right across the UK’.Footnote70 Access to the charity gives Coca-Cola both a series of positive images around disadvantaged people and physical activity and helps to neutralize criticism of its activities. Similarly, Mondelez used Cadbury’s sponsorship of the Premier League campaign to promote ‘Joy Schools’, their ‘flagship social-responsibility programme’in Malaysia.Footnote71

Limitations and future research

Data from Twitter were central to the analysis produced in each of the case studies. However, other social media platforms such as Instagram, Tik Tok and YouTube could also have been used and may have contributed different perspectives to our research. It is certainly impossible to either capture the full complexity of digital platforms when only using one platform or indeed to comprehensively measure brand engagement.

However, the large volume of grey literature available assisted in developing an understanding of the methods used by transnational corporations to promote their brands both in the UK and globally. A limitation is that searches have been carried out in the English language only so that data relating to some aspects of global marketing may have been missed.

There are many opportunities for future research. A similar study could be undertaken which examines a wider range of digital platforms to explore online marketing in sport. Secondly, although marketeers will hope brand engagement leads to increased consumption, it would be relevant to corporations, social science and public health academics to understand more about the effectives of various marketing approaches. Finally, there is much to be explored in the psychological sphere in terms of the language and imagery used in sport marketing and in new areas such as automated emotion analysis techniques which utilize artificial intelligence technologies.

Conclusions

Each of the three corporate partners of the EPL we examined sought to exchange their economic capital to access the social capital held by the EPL and its clubs to enable engagement with fan-consumers. Football offers excitement, passion, cultural heritage and tradition which were all tropes used by the three corporations in their marketing campaigns to gain attention for their brands. Brand activation attempts to create an emotional and cultural connection with the consumer. Its ultimate aim is to produce consumption of a product by consumers and to integrate the brand into their lives through shared experiences.Footnote72 Our study shows how three unhealthy commodity brands attempt this through their commercial partnerships with the EPL.

Whilst the marketing campaigns of transnational corporations are considered by public health advocates to be ‘harming our physical, mental, and collective wellbeing’,Footnote73 consumers are blamed if they consume too many of their products and are chastised by these same companies (and government) to act responsibly; they are subject to ‘responsibilisation’ in a contradictory dynamic of addictive consumer capitalism.Footnote74

The UK government’s latest obesity strategy noted that food choices are ‘shaped and influenced through advertising in its many forms’.Footnote75 It is important that sponsorship should not be separated from advertising in considering regulation which helps to protect football fans (including many children and young people) from the marketing of HFSS food beverages and alcohol. Public health academicsFootnote76 and organizations such as the European Healthy Stadia NetworkFootnote77 are raising concerns about unhealthy sport sponsorship. This study supports these concerns.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. Whannel, ‘Fields in Vision’.

2. EPL, ‘Global Media Platform’ and ‘Global Fan Base’.

3. Jahiel and Babor, ‘Industrial epidemics, public health advocacy and the alcohol industry: lessons from other fields’.

4. Giulianotti and Robertson, ‘Globalization and Football’.

5. Parry et al., ‘Watching Football as Medicine: promoting health at the football stadium’; Cassidy and Ovenden, ‘Frequency, duration and medium of advertisements for gambling and other risky products in commercial and public service broadcasts of English Premier League football’.

6. Purves et al., ‘Alcohol Marketing during the UEFA EURO 2016 Football Tournament: A Frequency Analysis’.

7. Garde and Rigby, ‘Going for gold – Should responsible governments raise the bar on sponsorship of the Olympic Games and other sporting events by food and beverage companies’.

8. Ireland et al., ‘Commercial determinants of health: advertising of alcohol and unhealthy foods during sporting events’.; and Djohari et al. ‘The visibility of gambling sponsorship in football related products marketed directly to children’.

9. Petticrew et al., ‘Alcohol advertising and public health: systems perspectives versus narrow perspectives’.

10. Afshin et al., ‘Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017’.

11. Kelly et al., ‘Food and drink sponsorship of children’s sport in Australia: who pays?’

12. Purves et al., ‘Alcohol Marketing during the UEFA EURO 2016 Football Tournament: A Frequency Analysis’.

13. Purves et al., ‘Examining the frequency and nature of gambling marketing in televised broadcasts of professional sporting events in the United Kingdom’.

14. Bourdieu, ‘The state, economics and sport’. 17.

15. Bourdieu, ‘The Field of Cultural Production’.

16. Bourdieu, ‘The state, economics and sport’.

17. O’Keefe, Titlebaum and Hill, ‘Sponsorship activation: Turning money spent into money earned’.

18. Keller, ‘Strategic Brand Management. Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity’.

19. Cornwell, ‘Less “Sponsorship as Advertising” and More Sponsorship-Linked Marketing As Authentic Engagement’.

20. Ibid.

21. Meenaghan, ‘Understanding Sponsorship Effects’.

22. Hollebeek, ‘Exploring customer brand engagement: definition and themes’.

23. Cornwell, ‘Sponsorship in Marketing. Effective Partnerships in Sports, Arts and Events’.

24. Thomas, ‘How to do Your Case Study’.

25. Stake, ‘The Art of Case Study Research’.

26. Thomas, ‘How to do Your Case Study’.

27. Robinson,‘Inside the Premier League’s nine sponsorship deals for the 2019/20 season’.

28. Stake, ‘The Art of Case Study Research’.

29. Read et.al., 'Consumer engagement on Twitter: perceptions of the brand matter'.

30. Braun, Clarke and Weate, ‘Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research’.

31. Coca-Cola GB, ‘Welcome to ‘Where Everyone Plays’‘.

32. Robson ‘No one likes us, we don’t care’.

33. Pracejus, ‘Seven Psychological Mechanisms Through Which Sponsorship Can Influence Consumers’.

34. Meenaghan, ‘Understanding Sponsorship Effects’.

35. Arrigo, ‘Pick of the Week: Coca-Cola scores with Premier League ad’. 1.

36. Meenaghan, ‘Understanding Sponsorship Effects’.

37. Premier League, ‘The Premier League and Cadbury kicked off their exciting partnership in the 2017/18 season’.

38. Taylor, ‘Football and its Fans. Supporters and their Relations with the Game, 1885-1985’.

39. Williams, ‘Branded’.

40. Mondelez International, ‘Young Aspiring Footballers Treated to Cadbury’s Football Clinic with Michael Owen‘.

41. Mondelez International, ‘Young Aspiring Footballers Treated to Cadbury’s Football Clinic with Michael Owen‘.

42. Premier League, ‘Premier League partners with Budweiser’.

43. Chakraborty, ‘Budweiser makes a sporty move in India: partners as Broadcast Co-presenting with Premier League’.

44. Esan, ‘Budweiser is Delivering Fun, Exciting Experience at Viewing Parties as Promised’.

45. BellaNaija.com, ‘Anticipate a Fresh Dose of Naija’s Pop Culture as Budweiser brings to You #Kingsof Football’.

46. Lash and Lury, ‘Global Culture Industry’.

47. Goldman, ‘Capital’s Brandscapes’ and Bourdieu ‘The forms of capital’.

48. Bűhler and Nufer, ‘Relationship Marketing in Sport’.

49. EPL., ‘Global Media Platform’ and ‘Global Fan Base’.

50. Kelly et al., ‘A hierarchy of unhealthy food promotion effects: identifying methodological approaches and knowledge gaps’.

51. Hastings, ‘Why corporate power is a public health priority’.

52. Cornwell, ‘Sponsorship in Marketing. Effective Partnerships in Sports, Arts and Events’.

53. Aichner, ‘Football clubs’ social media use and user engagement’.

54. Elias and Dunning, ‘Quest for excitement. Sport and leisure in the civilizing process’.

55. Bűhler and Nufer, ‘Relationship Marketing in Sport’.

56. Manoli and Kenyon, ‘Football and marketing’.

57. Robson ‘No one likes us, we don’t care’.

58. Lopez-Gonzalez, Guerrero-Solé, and Griffiths, ‘A content analysis of how “normal” sports betting behaviour is represented in gambling advertising’.

59. Sugden and Tomlinson, ‘FIFA and the Contest for World Football. Who rules the people’s game?’ 93.

60. Cortese and Ling, ‘Enticing the New Lad: Masculinity as a Product of Consumption in Tobacco Industry-Developed Lifestyle Magazines’, 4.

61. Cortese and Ling, ‘Enticing the New Lad: Masculinity as a Product of Consumption in Tobacco Industry-Developed Lifestyle Magazines’.

62. Messner and Montez de Oca, ‘The Male Consumer as Loser: Beer and Liquor Ads in Mega Sports Media Events’.

63. Kickbusch, Allen and Franz, ‘The commercial determinants of health’.

64. Allen, ‘Commercial Determinants of Global Health’.

65. Schrecker and Bambra, ‘How Politics Makes Us Sick. Neoliberal Epidemics’.

66. Maani et al., Corporate practices and the health of populations: a research and translational agenda’.

67. Rose, ‘Governing “advanced” liberal democracies’.

68. Amis and Cornwell, ‘Sport Sponsorship in a Global Age’.

69. Cornwell, Sponsorship in Marketing. Effective Partnerships in Sports, Arts and Events.

70. Nestle, ‘Taking on Big Soda (And Winning)’.

71. Street Games, ‘What We Do’.

72. Mondelez International, ‘Young Aspiring Footballers Treated to Cadbury’s Football Clinic with Michael Owen‘.

73. Saeed et al., Brand Activation: A Theoretical Perspective’.

74. Hastings, ‘Why corporate power is a public health priority’. 345.

75. Reith, ‘Addictive Consumption. Capitalism, Modernity and Excess’.

76. HM Government, ‘Tackling obesity: empowering adults and children to live healthier lives’. 9.

77. Dixon, Lee and Scully, ‘Sports Sponsorship as a Cause of Obesity’.

Bibliography

- Afshin, A., P. John Sur, K.A. Fay, L. Cornaby, G. Ferrara, J.S. Salama, E.C. Mullany, et al. ‘Health Effects of Dietary Risks in 195 Countries, 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017.’ The Lancet, 393 05/11/May 2019 2019: 1958–1972. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8.

- Aichner, T. ‘Football Clubs’ Social Media Use and User Engagement.’ Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 37, (2019): 242–257. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-05-2018-0155.

- Allen, L.N. ‘Commercial Determinants of Global Health.’ in Handbook of Global Health, ed. I. Kickbusch, D. Ganten, and M. Moeti, 1275–1310. Geneva: Springer International, 2020.

- Amis, J., and T. Bettina Cornwell. ‘Sport Sponsorship in a Global Age.’ In Global Sports Sponsorship, ed. J. Amis and T.B. Cornwell, 1–17. Oxford: Berg, 2005.

- Arrigo, Y. ‘Pick of the Week: Coca-Cola Scores with Premier League Ad.’ Campaign, (2019): 1.

- BellaNaija, C. ‘Anticipate a Fresh Dose of Naija’s Pop Culture as Budweiser Brings to You #kingsoffootball.’ https://www.bellanaija.com/2020/01/budweiser-kings-of-football/.

- Bourdieu, P. The Field of Cultural Production. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1993.

- Braun, V., V. Clarke, and P. Weate. ‘Using Thematic Analysis in Sport and Exercise Research.’ In Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise, ed. B. Smith and A.C. Sparkes, 191–205. Abingdon: Routledge, 2017.

- Bridgewater, S. Football Brands. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Bűhler, A., and G. Nufer. Relationship Marketing in Sport. Abingdon: Routledge, 2013.

- Cassidy, R., and N. Ovenden. Frequency, Duration and Medium of Advertisements for Gambling and Other Risky Products in Commercial and Public Service Broadcasts of English Premier League Football. Goldsmiths, University of London. 2017. https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/20926/1/Frequency%2C%20duration%20and%20medium%20of%20advertisements%20for%20gambling%20and%20other%20risky%20products%20in%20commercial%20and%20public%20service%20broadcasts%20of%20English%20Premier%20League%20football%20%283%29.pdf

- Chakraborty, D. ‘Budweiser Makes a Sporty Move in India; Partners as Broadcast Co-Presenting with Premier League.’ afaqs!, (2019): 1.

- Coca-Cola, G.B. ‘Welcome to Where Everyone Plays’. news release, 2019, https://www.coca-cola.co.uk/marketing/sponsorships-and-partnerships/premier-league/coca-cola-and-the-premier-league-welcome-to-where-everyone-plays. (Accesed 15 July 2020).

- Cornwell, T.B. ‘Less ‘Sponsorship as Advertising’ and More Sponsorship-Linked Marketing as Authentic Engagement.’ Journal of Advertising, 48, (2019): 49–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2019.1588809.

- Cornwell, T.B. Sponsorship in Marketing. Effective Partnerships in Sports, Arts and Events. Second. Abingdon: Routledge, 2020.

- Cortese, D.K., and P.M. Ling. ‘Enticing the New Lad: Masculinity as a Product of Consumption in Tobacco Industry-Developed Lifestyle Magazines.’ Men and Masculinities, 14, (2011): 4–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X09352177.

- Bourdieu, P.‘The State, Economics and Sport.’ France and the 1998 World Cup. The National Impact of a World Sporting Event, ed. H. Dauncey, and G. Hare, London: Frank Cass, 1999. 15–21.

- Dixon, H., A. Lee, and M. Scully. ‘Sports Sponsorship as a Cause of Obesity.’ Current Obesity Reports, 8 (2019): 480–494. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-019-00363-z.

- Elias, N., and E. Dunning. Quest for Excitement. Sport and Leisure in the Civilizing Process. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1986.

- EPL . Global Fanbase. (Premier League, 2017). http://fanresearch.premierleague.com/global-fanbase.aspx. (Accessed: 11 April 2021).

- EPL . Global Media Platform. (Premier League, 2017), http://fanresearch.premierleague.com/global-media-platform.aspx. (Accessed: 11 April 2021).

- Esan, D. ‘Budweiser Is Delivering Fun, Exciting Experience at Viewing Parties as Promised’. Sports247, https://www.sports247.ng/budweiser-is-delivering-fun-exciting-experience-at-viewing-parties-as-promised/. (Accessed 3 August 2020).

- Garde, A., and N. Rigby. ‘Going for Gold - Should Responsible Governments Raise the Bar on Sponsorship of the Olympic Games and Other Sporting Events by Food and Beverage Companies?’ Communications Law, 17, (2012): 42–49.

- Giulianotti, R., and R. Robertson. Globalization & Football. London: SAGE, 2009.

- Goldman, R., and S. Papson. ‘Capital’s Brandscapes.’ Journal of Consumer Culture, 6, (2006): 327–353. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540506068682.

- Hastings, G. ‘Why Corporate Power Is a Public Health Priority.’ British Medical Journal, 345, (2012): 26–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e5124.

- Hibai, L.-G., F. Guerrero-Solé, and M.D. Griffiths. ‘A Content Analysis of How ‘Normal’ Sports Betting Behaviour Is Represented in Gambling Advertising.’ Addiction Research & Theory, 26, (2018): 238–247. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2017.1353082.

- HM Government. ‘Tackling Obesity: Empowering Adults and Children to Live Healthier Lives.’ eds., Department of Health & Social Care, (London: HM Government, 2020). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/tackling-obesity-government-strategy/tackling-obesity-empowering-adults-and-children-to-live-healthier-lives

- Hollebeek, L. ‘Exploring Customer Brand Engagement: Definition and Themes.’ Journal of Strategic Marketing, 19, (2011): 555–573. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2011.599493.

- Ireland, R., C. Bunn, G. Reith, M. Philpott, S. Capewell, E. Boyland, and S. Chambers. ‘Commercial Determinants of Health: Advertising of Alcohol and Unhealthy Foods during Sporting Events.’ Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 97 (2019): 290–295. doi:https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.18.220087.

- Jahiel, R.I., and T.F. Babor. ‘Industrial Epidemics, Public Health Advocacy and the Alcohol Industry: Lessons from Other Fields.’ Addiction, 102 (2007): 1335–1339.

- Keller, K.L. Strategic Brand Management. Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity. Fourth. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2013.

- Kelly, B., L.A. Baur, A.E. Bauman, L. King, K. Chapman, and B.J. Smith. ‘Food and Drink Sponsorship of Children’s Sport in Australia: Who Pays?’ Health Promotion International, 26, (2010): 188–195. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daq061.

- Kelly, B., L. King, K. Chapman, E. Boyland, A.E. Bauman, and L.A. Baur. ‘A Hierarchy of Unhealthy Food Promotion Effects: Identifying Methodological Approaches and Knowledge Gaps.’ American Journal of Public Health, 105 (2015): e86–e95. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302476.

- Kickbusch, I., L. Allen, and C. Franz. ‘The Commercial Determinants of Health.’ The Lancet, 4 (2016): 895–896.

- Lash, S., and C. Lury. Global Culture Industry. Cambridge: Polity, 2007.

- Maani, N., M. McKee, M. Petticrew, and S. Galea. ‘Corporate Practices and the Health of Populations: A Research and Translational Agenda.’ The Lancet, nos 5 (2), (2020): e80–e81.

- Manoli, A.E., and J. Andrew Kenyon. ‘Football and Marketing.’ in Routledge Handbook of Football Business and Management, ed. S. Chadwick, D. Parnell, P. Widdop, and C. Anagnostopoulos, (Abingdon: Routledge, 2019), 88–100

- Mark, P., I. Shelmit, T. Lorenc, T.M. Marteau, G.J. Melendez-Torres, A. O’Mara-Eves, K. Stautz, and J. Thomas. ‘Alcohol Advertising and Public Health: Systems Perspectives versus Narrow Perspectives.’ Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 71 (2017): 308–312. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2016-207644.

- Meenaghan, T. ‘Understanding Sponsorship Effects.’ Psychology & Marketing, 18, (2001): 95–122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6793(200102)18:2<95::AID-MAR1001>3.0.CO;2-H.

- Messner, M.A., and J. Montez de Oca. ‘The Male Consumer as Loser: Beer and Liquor Ads in Mega Sports Media Events.’ Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 30, (2005): 1879–1909. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/427523.

- Mondelez International (Malaysia). ‘Young Aspiring Footballers Treated to Cadbury’s Football Clinic with Michael Owen.’ News Release, 2019, http://redzoommedia.blogspot.com/2019/03/young-aspiring-footballers-treated-to.html. (Accessed: 2 February 2020).

- Nestle, M. Soda Politics. Taking on Big Soda (And Winning). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- O’Keefe, R., P. Titlebaum, and C. Hill. ‘Sponsorship Activation: Turning Money Spent into Money Earned’.’ Journal of Sponsorship, 3, (2009): 43–53.

- Parry, K.D., E.S. George, J. Richards, and A. Stevens. ‘Watching Football as Medicine: Promoting Health at the Football Stadium.’ in Football as Medicine. Prescribing Football for Global Health Promotion, ed. P. Krustrup and D. Parnell, (Abingdon: Routledge , 2020): 183–200.

- Pracejus, J.W. ‘Seven Psychological Mechanisms through Which Sponsorship Can Influence Consumers.’ in Sports Marketing and the Pyschology of Marketing Communication, ed. L.R. Kahle and C. Riley, Mahwah: Erlbaum, 2004.

- Premier League. ‘Premier League Partners with Budweiser.’ https://www.premierleague.com/news/1291167. (Accessed: 31 January 2020).

- Premier League. ‘The Premier League and Cadbury Kicked off Their Exciting Partnership in the 2017/18 Season.’ https://www.premierleague.com/partners/cadbury. (31 January 2020).

- Purves, R.I., N. Critchlow, A. Morgan, M. Stead, and F. Dobbie. ‘Examining the Frequency and Nature of Gambling Marketing in Televised Broadcasts of Professional Sporting Events in the United Kingdom.’ Public Health, 184 (2020): 71–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.02.012.

- Purves, R.I., N. Critchlow, M. Stead, J. Adams, and K. Brown. ‘Alcohol Marketing during the UEFA Euro 2016 Football Tournament: A Frequency Analysis.’ International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14, (2017): 704. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14070704.

- Reith, G. Addictive Consumption. Capitalism, Modernity and Excess. Abingdon: Routledge, 2019.

- Robertson, W., McQuilken, N., Ferdous, A.S. ‘Consumer engagement on Twitter: perceptions of the brand matter.‘.European Journal of Marketing, 2019, 1905–1933.

- Robinson, D. ‘Inside the Premier League’s Nine Sponsorship Deals for the 2019/20 Season.’ NS Business 9 August 2019. https://www.ns-businesshub.com/business/english-premier-league-sponsors-2019-20/. (Accessed 8 April 2021).

- Robson, G. ‘No One Likes Us, We Don’t Care’: The Myth and Reality of Millwall Fandom. (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2000).

- Rose, N. ‘Governing ‘Advanced’ Liberal Democracies.’ in Foucault and Political Reason: Liberalism, Neo-Liberalism and Rationalities of Government, ed. A. Barry, T. Osborne, and N. Rose, (London: UCL Press , 1996): 37–64.

- Saeed, R., H. Zameer, S. Tufail, and I. Ahmad. ‘Brand Activation: A Theoretical Perspective.’ Journal of Marketing and Consumer Research, 13 2015, 94–99.

- Schrecker, T., and C. Bambra. How Politics Makes Us Sick. Neoliberal Epidemics. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research. London: SAGE, 1995.

- Street Games. ‘What We Do.’ https://www.streetgames.org/what-we-do. (Accessed: 11 February 2020).

- Sugden, J., and A. Tomlinson. FIFA and the Contest for World Football. Who Rules the Peoples’ Game? Cambridge: Polity Press, 1998.

- Taylor, R. Football and Its Fans. Supporters and Their Relations with the Game, 1885-1985. Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1992.

- Thomas, G. How to Do Your Case Study. London: SAGE, 2011.

- Viggars, M. Sport Relegated to Subs Bench in Fight against Obesity. (Liverpool: European Healthy Stadia Network, 2020).

- Whannel, G. Fields in Vision. Television Sport and Cultural Transformation. London: Routledge, 2002.

- Williams, G. Branded? London: V&A Publications, 2000.