ABSTRACT

A vast literature analyzes how Bengali identities developed in colonial India. This article steps away from both celebratory approaches and a focus on the colonial period. Instead, it explores how non-Bengalis increasingly challenged Bengali superiority in more recent times. As the colonial incarnation of a genteel Bengaliness lost its bearings and split into competing territorial manifestations in East Pakistan (later Bangladesh) and India, it encountered rising hostility and developed both assertive and timid configurations. This article offers an exploratory overview of how various groups of non-Bengalis have been rebuffing Bengali dominance by means of cultural distancing, graphic resistance, the ideology of indigeneity, insurgency, and the legal and military force of postcolonial states.

Introduction

Two centuries ago, a specific identity – “Bengaliness” – began to change the vast South Asian region of Bengal and the lands surrounding it. In this article, I look at efforts to contain and curb this identity. There is an extensive literature about Bengali identity, but it is sadly fragmented. We have distinct bodies of knowledge on the British and post-British eras, but few studies across the colonial/postcolonial divide. In addition, postcolonial studies of Bengaliness have been largely blinkered by national Bangladeshi and Indian perspectives. These obscure that today Bengaliness is a transnational identity in conversation with many other identities in Bengal and the wider region. Third, Bengaliness is often associated with upper-middle-class, educated, and urban understandings of that identity, marginalizing various lower-class, local, and rural understandings. Fourth, the cultural dimension of Bengaliness receives more attention than its political features. Finally, studies of Bengaliness tend to be self-absorbed; they generally fail to incorporate non-Bengali inputs, responses, and impacts. Thus, we remain largely ignorant of what non-Bengali neighbors have thought about Bengaliness, how they have acted on these insights, and how they have influenced Bengali identities. The existing historiography is Bengali-centric and presents only half the conversation.

Historians need to understand Bengaliness as a powerful, evolving, multifaceted, and transnational identity in constant dialogue with many others. This mission goes well beyond the reach of this article, which neither intends to be comprehensive nor aims at presenting a biography of postcolonial Bengaliness. I merely seek to encourage a comparative approach to postcolonial Bengaliness and to non-Bengali strategies to rebuff highhanded forms of it, across a region that is now divided by international borders.Footnote1

What is Bengaliness? Some 270 million people speak the Bengali (or BanglaFootnote2) language, making it the world’s sixth largest in terms of native speakers. It is the national language of Bangladesh and the official language of two states in India (West Bengal and Tripura), and there are millions of native speakers beyond these administrative units.Footnote3 Bengali is clearly the dominant language in Bengal, but this large region has always been distinctly multilingual, and continues to be so.

It is important to realize that there is something programmatic about referring to “the Bengali language” as a historical formation. While there has been a written form of Bengali for some ten centuries, throughout this time spoken forms varied widely across the region and it was impossible to identify clear linguistic boundaries. Without a unifying state, a national army, schools, or other institutions to impose a standard language, and only a minute proportion of literate inhabitants, many speakers of what linguists later categorized as Bengali dialects did not identify with any standard language. Instead, they referred to their speech forms by local names (such as Jaintiapuri, Noakhailla, Siripuria, and Chatgaia buli). Therefore, it is a moot point to what extent they considered themselves to be speakers of Bengali.Footnote4

Subsuming this welter of vernaculars under the rubric of the Bengali language was a long process. It gathered pace after the British East India Company occupied the region in the eighteenth century. Two groups were especially influential. Colonial linguists were keen to impose order on the dazzling complexities of South Asian speech forms. And educated cultural activists who thought of their own dialect as “standard Bengali” used it in their efforts to construct a Bengali identity, a Bengali community, a Bengali nation, and “Bengaliness.”Footnote5

A sophisticated historiography exists that is devoted to the flourishing of this vision of Bengaliness during British rule. Historians have been less interested in how it fared in the rocky post-British period when the notion of Bengali superiority became entangled in state practices of internal colonialism and countermoves progressively sought to restrict its reach. This article focuses on these moves to “provincialize” postcolonial Bengaliness.Footnote6 But to situate these postcolonial struggles over Bengaliness, we need a brief sketch of its complex colonial crafting.Footnote7

Bengaliness: colonial contortions

The British East India Company’s annexation of Bengal in the year 1757 prompted leading elite Bengalis, largely concentrated in the colonial city of Calcutta (Kolkata), to develop a new understanding of regional identity. This was based on the idea of a shared language and a sense of unity among Bengali speakers, and it celebrated their cultural production. Bengali identity, or Bengaliness, took on a proud new meaning for them as they assumed the mantle of spokespeople for the region’s inhabitants. Their version of Bengali – a “new Sanskritized and sanitized language under preparation in Calcutta”Footnote8 – formed the basis of this new Bengali paradigm, but they also considered numerous cultural practices, including food, music, speech genre, literary writing, and dress style, to be quintessentially Bengali.Footnote9 For them, to be a Bengali was to be sophisticated, cultured, aware of the wider world, and in possession of delicate sensibilities.

Generations of scholars have closely analyzed and interpreted this model, and it continues to be a topic of intense academic scrutiny. The result is an intricate historiography with its own codes and expressions. Thus, the term “Bengal Renaissance” evolved to refer to cultural and social changes that commenced in the early years of the nineteenth century. And bhadralok (respectable people, or genteel society – distinct from the common people, known as chhotalok) became the key term for the literary-minded upper class in Calcutta who steered this intellectual and cultural project.Footnote10

The elaboration of Bengaliness was a response to the shock of British annexation and a worldwide upswing of nationalist models. Bengal was the first sizeable region of South Asia that the British acquired and the colony of British India expanded from this bridgehead. Calcutta became the capital of British India and would remain so for a century and a half. The composite social elite of Bengal now had to cope with the fact that they were relegated to a subservient position, which necessitated serious soul-searching. Added to this was their new overlords’ need for a class of local officeholders to help them collect land taxes and run the colonial administration. For these ends, British-style education was opened for a select group of youngsters in Bengal, and some were also admitted to universities in Britain. Their encounter with European ideas about civilization, nationalism, modernity, rational thought, religion, class, gender, and urbanity played a major role in firing the cultural stirrings now known as the Bengal Renaissance.

These Banglaphone recipients of colonial education, privileges, and employment generated the new paradigm of Bengaliness. It was embodied in poets, playwrights, essayists, educators, composers, and novelists whose creative works fired people’s imaginations, decoded social change, bolstered self-confidence, and welcomed readers into a community of refined emotion and inner nobility. Among these many cultural heroes were people that continue to be deeply admired and widely reviewed in contemporary scholarship and public discourse, for example, Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833), Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay (1838-1894), and Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941). Even though those who propagated the new meaning of Bengaliness formed only a tiny minority, over time their adaptation became the bedrock of self-identification for many middle-class Bengalis. As a result, the term bhadralok broadened to include those who shared the elites’ dreams, respect for high culture, and genteel attitudes, without necessarily sharing their wealth, education, or service jobs.Footnote11

Over time Bengaliness became more than an aesthetic and emancipatory identity; it turned into something of a civilizational model, to be admired and emulated by less refined others in South Asia. According to Chatterji, “as the uncovenanted beneficiaries of the Permanent Settlement, as compradors and collaborators, the bhadralok dominated nineteenth-century Bengal and successfully staked their claim to be the fuglemen of a new India.”Footnote12 But this political claim to superiority (what Bandyopadhyay described as “Bengal’s geopolitics”Footnote13) gave rise to an avalanche of critical voices, initially hesitant but increasingly strident.

Intra-Bengali contestations

Certain Bengali speakers resisted this civilizational model on the grounds of class, education, employment, religion, region, and gender. These detractors disputed the model’s point of departure: the unity of all Bengalis. They demonstrated that there were many ways in which people could express their Bengaliness. One critique was that genteel Bengaliness idolized the subculture of a minute well-off minority, the largely high-caste Hindu “respectable people” who lived mostly in the colonial capital and rural manor houses. Bengali Hindus belonging to lower orders as well as non-Hindu Bengalis found it hard to recognize themselves in the model, and they increasingly challenged the right of high-caste Hindus to speak for all Bengalis. These critics pointed out that the bhadralok lifestyle was not only based on educational privileges and cultural achievement, but also had its roots in the exploitation of the labor of other Bengalis: agricultural tenants, servants, women, and dependents. Therefore, the genteel model of Bengaliness served the interests of the elite vis-à-vis the colonial rulers as well as vis-à-vis most other Bengalis.Footnote14

Historians have studied this critique most closely for two groups: Bengali MuslimsFootnote15 and low-caste Hindus/Dalits.Footnote16 The genteel model favored the idea that high-caste Hindus were the “primary citizens of the land and inheritors of an ancient Aryan civilization.”Footnote17 From the late nineteenth century onwards Muslim and low-caste/Dalit contestations signaled that a high-caste appropriation of Bengaliness was untenable.Footnote18 Even so, many bhadralok dismissed non-bhadralok definitions of Bengaliness as irrelevant. The political consequences of this attitude became painfully clear as the twentieth and twenty-first centuries unfolded, and the region of Bengal was torn apart.

Colonial Bengaliness beyond the Bengali fold

The historiography has tended to treat Bengaliness as an autonomous creation. Historians have paid relatively little attention to how it emerged from interactions with numerous other regional identities. Rather, they have understood it primarily as an emancipatory cultural phenomenon in response to British rule in Bengal. What was crucially important, however, was that educated Bengalis, who felt superior to others in the region, translated their notion of Bengaliness into political entitlements. They used it to wield power. As British rule spread across South Asia, the colonial government placed educated Bengalis in administrative, educational, and other salaried jobs well beyond Bengal. Just like Bengal, these surrounding areas were cultural and linguistical composites. In these places, Bengali speakers were in the minority and the expansion of educated Bengalis with claims of cultural superiority set in train several reactions.

Some were welcoming, and certain non-Bengalis chose to emulate genteel Bengaliness.Footnote19 Others rebuffed Bengali superiority, most notably in Orissa (Odisha), Bihar, and Assam (). In these places, the colonial state often appeared to be a British-Bengali coproduction. A decidedly anti-Bengali attitude fueled local emancipatory projects that successfully resisted Bengalization and established other languages – Odia, Hindi, and Assamese – as alternative languages of education and officialdom. It has been said that Bengali-language activists were appalled because they felt that “the outlying provinces were being unjustly taken away from the cultural custody of Calcutta.”Footnote20

By the turn of the twentieth century, it was clear that the Bengali civilizational model had failed to travel beyond the Bengali-speaking heartland.Footnote21 The conviction that Odia, Assamese, and the speech practices of eastern Bihar were all Bengali dialects – and should benefit from the civilizing touch of Calcutta bhadralok speech – had suffered defeat. The dream of a Greater Bengali identity fell apart because the colonial state had accepted these languages as separate from – and basically on a par with – Bengali.Footnote22 A new trend had manifested itself across the wider region: language and (colonially demarcated) territory became welded together in the forging of competing nation-building projects.Footnote23

Splitting the Bengali heartland

The link between language, power, and territory was further tested in 1905 when the colonial authorities decided to divide the region into two new provinces: one containing eastern Bengal and Assam, and the other western Bengal, Orissa, and Bihar. This move led to what one author has described as “bhadralok hysteria”Footnote24 and the emergence of conspiracy theories among high-caste Hindus who saw it as a calculated attack on Bengali unity and power, and an insult to Bengal’s cultural heritage.Footnote25 Many Calcutta bhadralok feared losing their cultural and economic control of eastern Bengal. Many Muslim Bengalis welcomed the split, however, hoping for emancipatory effects and better career prospects because eastern Bengal had a clear Muslim majority. These fears and hopes proved largely realistic. In the new province of Eastern Bengal and Assam, the bhadralok found that they were less privileged than in Calcutta.

A militant anti-colonial movement followed the split.Footnote26 It depended heavily on Hindu imagery to mobilize the Bengali masses. Although this was in line with mainstream nationalist thought at the time, it offended many Muslims and contributed to a fateful new twist in Bengaliness as religious identities began to crystallize into compelling political ones. Communal politics, which pitted Bengali Hindus against Bengali Muslims, became a reality. It forced the bhadralok to woo low-caste/Dalit Bengalis into the Hindu fold to build up numbers. Although the administrative division of Bengal was annulled in 1911, communal mindsets survived. Bengal was administratively reunited but the spell of genteel Bengaliness had been broken. Communal politics would dominate the final phase of British rule and turn out to be a major factor in a second territorial partition of the Bengali heartland as the British left.

A final bid to mobilize all Bengalis as a political community was made by a group of Calcutta politicians in 1947. Fearing the breakup of the Bengali heartland as British rule ended, they proposed a “United Bengal” – a sovereign nation-state separate from both India and Pakistan. But it came to nothing: “the United Bengal Plan was never more than a pipe dream.”Footnote27 The all-Bengal nation-state that they longed for never materialized.

Bengaliness: postcolonial complications

In the decades after British rule ended, Bengaliness found itself on a different course. Some processes were especially influential in modifying and restraining it. First, Bengaliness fell victim to bifurcation, as did the study of Bengaliness, which split into parallel Indian and Pakistani/Bangladeshi conversations.Footnote28 Second, new international borders blocked the dispersal of Bengaliness (). Third, postcolonial state elites adopted Bengaliness as a discourse of cultural superiority and political dominance. Fourth, Bengaliness faced new forms of rejection and resistance. And fifth, an emergent global discourse of Indigeneity constructed Bengalis as the Other.

Dual Bengaliness

The Muslim-Hindu antagonism that had taken political shape at the beginning of the twentieth century culminated in renewed territorial division when the British left in 1947. British India was broken into Muslim-majority and non-Muslim-majority territories, the former becoming Pakistan and the latter India. Eastern Bengal became East Pakistan, and western Bengal (which was smaller and less populous) joined India as one of its federated states. Many Muslim Bengalis left India for East Pakistan, just as many Hindu Bengalis left East Pakistan for India.Footnote29

As bhadralok Bengalis – “former imperial subordinates”Footnote30 – saw their colonial moorings slip away, they took control of West Bengal, where they consolidated genteel Bengaliness and underscored its duality by elevating local (ghoti) lifestyles over those of immigrants from eastern areas (bangal), whom they portrayed as rustic and unsophisticated.Footnote31 For the political elite, Bengaliness also became a powerful tool in their struggles with India’s central state. Meanwhile, in East Bengal the genteel model declined as both a rising Bengali middle class and the Pakistan state searched for a new Muslim Bengaliness and more “Islamic” speech forms, dress codes, food habits, literature, and architecture.Footnote32 Dhaka became the new citadel of a retooled Bengaliness.

Separate territorialization became even more definite when, in 1971, East Pakistan broke away and became the independent state of Bangladesh. In East Pakistan, right from the start in 1947, local politicians opposing the dominant West Pakistan state elite employed Bengaliness as a powerfully mobilizing force.Footnote33 Often referred to as the Language Movement, this resistance grew out of frustration about Bengali (the majority language of the 1947–1971 West and East Pakistan state) being denied the status of a national language. The language, its script, and Bengaliness all became emotive rallying points in a struggle that ended in a successful war of independence.Footnote34

After 1971, many observers in India expected the appeal of the genteel model of Bengaliness to reemerge in the east, but this did not happen. Bangladesh culture had been shaped by its distinct, tortuous post-1947 experiences. Increasingly self-confident, Bengalis in the new state of Bangladesh distanced themselves from the bhadralok-inspired model, and rival political parties projected their own versions.Footnote35 By the 2020s, Bangladesh and India each had thriving, territorialized forms of Bengaliness, and many Bengalis in India had come to accept that these forms should meet on a level playing field. Meanwhile, even in India the dominance of the genteel model was fading.Footnote36

Today the number of native speakers of Bengali in India and Bangladesh is about 270 million, four times larger than in the late 1940s. State policies, the educational system, and media outlets propagate parallel Kolkata-style or Dhaka-style “standard” Bengali. Even so, for many Bengali speakers, regional dialects remain the language of the heart and the home. The eastern and western forms of standard Bengaliness have been highly successful but they have not replaced more local identities such as Noakhali-ness, Dhakaiya-ness, or Jalpaiguri-ness by any means. Instead, many Bengalis speak standard Bengali as well as another dialect.

Turbulent as these transformations of postcolonial Bengaliness have been, they were an intra-Bengali issue that had little effect on how non-Bengali neighbors perceived Bengalis. In the colonial period, British wits and racial theorists had viciously lampooned genteel Bengaliness, describing Bengali men as effeminate, effete, non-martial, and pretentious.Footnote37 But effeteness was the last thing that non-Bengali neighbors associated with Bengalis: many were more impressed by Bengali assertiveness, expansionism, disdain, and guile.Footnote38

In the postcolonial era, Bengalis and non-Bengalis found themselves in a transformed cultural landscape without a trace of Bengali effeteness. Two major features were the emergence of Bengaliness as the idiom of state power, and the dismantling of colonial-era protections restricting Bengali settlement in certain areas.Footnote39 Another was what Townsend Middleton has called “forms of coloniality … endemic to the birthplace of Subaltern Studies, Bengal.”Footnote40 These developments compelled non-Bengalis increasingly to push back against Bengali ascendency.

Bengalis on the move

In colonial times, Bengalis had migrated within and beyond Bengal in small groups or as temporary migrants. After 1947 this pattern changed, and very large groups settled permanently in areas where they had been absent or minorities before. This spatial expansion led to new struggles because it often traversed recently imposed international state borders. As non-citizens and unauthorized newcomers, border-crossers could be vulnerable. They had no right to work, settle, or own property across the border. During colonial rule, everybody in British India had been a British subject. In independent India, Pakistan, and Burma, however, national citizenship emerged as a potent identity that was used to marginalize Bengali newcomers in areas beyond the Bengali heartland. And even in that heartland, citizenship trumped Bengaliness. Simply being Bengali among Bengalis no longer secured social acceptance and protection.Footnote41 Struggles over migration and citizenship generated legal, bureaucratic, and physical confrontations, as well as a new distinction between “assertive” and “timid” Bengaliness.

Bengali superiority as a state discourse

In Bangladesh, Tripura, and West Bengal, postcolonial state elites projected Bengaliness as a discourse of political dominance. Their choice to imagine these spaces as being purely Bengali inspired multiple forms of rejection. Non-Bengali inhabitants could be influenced, even charmed, by Bengali cultural expressions, but they recoiled from Bengali dominance. As state-backed ethnic intimidation became common and sometimes turned violent, non-Bengali citizens felt that their state elites ignored and disowned them. The state model of Bengali superiority promised state protection to Bengalis intent on criminal acts (discrimination, fraud, plunder, rape, murder) against their non-Bengali co-citizens ().

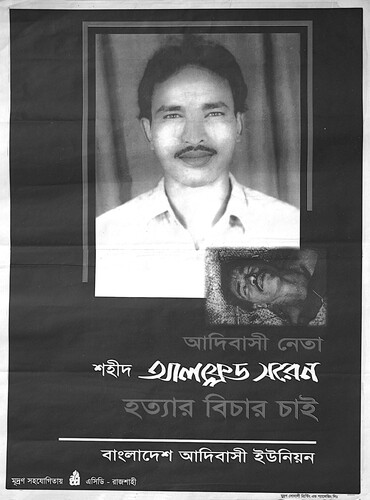

Figure 1. Alfred Soren, a Santal (non-Bengali) activist, was murdered after organizing protests against land-grabbing Bengali landlords in 2000. This poster demanded justice – but twenty-odd years later the case was still pending.Footnote42

SOURCE: Poster distributed by the Bangladesh Indigenous Union.

Language politics

In addition to struggles over citizenship and majoritarian supremacy, non-Bengalis also sought to rebuff Bengaliness in the “inner domain of cultural identity.”Footnote43 Among the many cultural tools at their disposal were marriage strategies, dress codes, cuisine, music, cinema, festivals, emblems, political parties, and social media.Footnote44 Their struggles also involved reclaiming elements of religion and folklore that Bengalis had presented as their own, reviving non-Bengali traditions, and challenging Brahmanical culture.Footnote45

Language was an especially powerful means of defending this inner domain. The written forms of South Asian languages have long been battlegrounds for identity politics. In this part of the world, for a language to have a unique script is widely understood to demonstrate high civilizational status. As literacy spread among smaller language communities, language politics flourished.Footnote46 Script served “not only as an important identity marker, but also as a demarcator from the dominant languages of the region, and maybe, ultimately, as a stabilizer” of languages.Footnote47

But many South Asian languages do not have a unique script. Instead, they have histories of “multiscriptality.” The Bengali language is no exception. Although today it is written in the Eastern Nagari script, it has used other scripts as well, notably Perso-Arabic and Roman, and during Pakistan times activists in Eastern Bengal attempted, but failed, to impose the Urdu-Arabic script.Footnote48

Conversely, scripts are often multilingual.Footnote49 Thus, Bengali is the most prominent language written in Eastern Nagari script, but it is not the only one. Both linguistically related languages (Assamese, Chakma) and non-related languages (Meitei, Kurux, and Toto) use this script, so it is a misnomer to speak of it as a “Bengali script.”Footnote50 Even so, Eastern Nagari is often symbolically identified with the Bengali language and its rejection understood as a rebuff to all things Bengali. Rejection came in two forms: readoption of previous scripts and invention of new ones.Footnote51

Script readoption

In some speech communities that had abandoned their own scripts and embraced the Eastern Nagari script, campaigns emerged for the reintroduction of the discarded script. In Manipur, the Meitei language (and possibly some other languagesFootnote52) had been written in a distinctive script. But after conversion to Vaishnavism – a “Bengali” form of Hinduism – in the eighteenth century, the “Bengali” script was introduced and spread with growing literacy during the colonial period. From the 1950s onward, however, Meitei activists began to resist the script (which they considered to be both alien and historically imposed) and made the Meitei script “a strong symbol for an allegedly lost glorious past, a tool for strengthening the modern Meitei identity.”Footnote53 Bengalis (who were not part of Manipur’s present) were constructed as “a historicized foe.”Footnote54 These efforts gradually gained ground, and today the Meitei Mayek script has considerable state backing. It is taught in schools and appears on billboards and government buildings, and in official documents ().

Figure 2. Script readoption. Meitei-language notice in two scripts (Meitei Mayek and Eastern Nagari), followed by English, in Imphal, Manipur, 2011. Credit: Willem van Schendel.

Chakma identity politics rejected this “Bengali” script in politically far more charged circumstances. The struggle for independence from Pakistan mobilized mass support by using the “Bengali” script as a powerful symbol of pride and identity. After Bangladesh gained independence in 1971, Bengaliness was anchored in the constitution of the new state, which stated that “Bangladesh’s citizens will be known as Bengali.” A Chakma member of the Constituent Assembly immediately objected to this.Footnote55 It became clear, however, that the new state elite celebrated Bengaliness, rejected cultural diversity, and refused to acknowledge the separate identities of the country’s dozens of ethnic minorities and languages.Footnote56 This contributed to an armed autonomy movement in the Chittagong Hill Tracts.Footnote57 Chakma activists used a revived and adapted script (Ojhapath) as one of their tools to underline that Chakmas were not Bengalis, and that the Chakma language was not a dialect of the Bengali language.Footnote58

A third variant of script readoption developed around the Sylheti vernacular, spoken in northeastern Bangladesh, in Assam and Tripura (India), and among a large diasporic community in the United Kingdom. Sylheti had historically been written in various scripts, one of which was the local Syloti Nagri script. It was used for print texts in the nineteenth century but was gradually marginalized by Eastern Nagari script. But it was not political conflict between Bengalis and Sylhetis that prompted the resurgence of Syloti Nagri. Rather, it was a purely cultural reassertion of Sylheti identity resulting largely from the efforts of a transnational group of script activists around 2000.Footnote59

Script invention

The second pattern of graphic resistance against Bengali superiority took the form of new scripts. Smaller language communities in and around the Bengali heartland often did not have written forms until formal education and Christian missionary activity reached them during the colonial period. Missionaries were instrumental in creating locally adapted Romanized scripts for different language communities. As Christianity spread, Bengalis found their heartland surrounded and punctuated by Roman script communities such as Garo, (A·chik),Footnote60 Khasi, Bawm, and Mizo.Footnote61 This led to postcolonial struggles over which script to use. Kokborok, Hajong, and Dimasa are examples of Eastern Nagari/Roman multiscriptality. More complicated cases of languages with multiple scripts are Kurux (three scripts) and Santali (five scripts).Footnote62 A special case of script invention is Rohingya, a language related to Bengali (and sometimes described as a Bengali dialect). And yet, after 1948 Rohingya speakers rejected the “Bengali” script – instead opting for Arabic/Urdu or Burmese scriptFootnote63 – until, in the 1980s, a new script was developed: Hanifi Rohingya ().Footnote64 After repeated mass flights of Rohingyas from their native Arakan (Rakhine) in Myanmar between the 1940s and the 2010s, hundreds of thousands ended up in refugee camps in Bangladesh, where some non-government organizations sought to introduce Roman script to teach the Rohingya language.

Figure 3. The word “Rohingya” written in Hanifi Rohingya script, which was developed in the 1980s. Credit: Willem van Schendel.

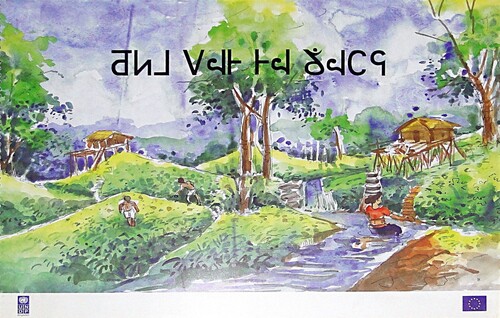

Finally, speakers of some unwritten languages opted for their own scripts without the intermediate step of using “Bengali” script. Like many non-literate language communities in the region, the Mro (or Mru) in the Chittagong Hill Tracts told stories of having had a script in the past but having lost it.Footnote65 In the 1980s, Man Le, a Mro visionary, developed the distinctive Mrocha script. Initially, it was linked to a new religion, Krama, but then spread more widely among Mro speakers. Today an estimated eighty percent of Mro are literate in the new script and it is being taught in the first three school years ().Footnote66 Script invention is an ongoing process, as the Toto of West Bengal demonstrate: they created their own script in the 2010s.Footnote67

Figure 4. Children’s book Shinglok’s Field in Mro script. SOURCE: Guhathakurta and Van Schendel (editors) 2013, 464–465.Footnote68

Postcolonial script politics have expressed “language grief,” a desire to salvage local identities, and a deliberate distancing from Bengaliness.Footnote69 They also have modified the meanings that people attach to places. Cultural campaigns and state policies continually changed the linguistic landscape (the written language forms found in the public spaceFootnote70). For example, Urdu signs became prominent in Eastern Bengal between 1947 and 1971, only to disappear overnight after Bangladesh became independent. Today, Bengali signs are more dominant in the linguistic landscape of Dhaka than in that of Kolkata (Calcutta), where Hindi and English are prominent competitors.Footnote71 And in Manipur, Meitei Mayek signs marginalized Bengali signs after the state government adopted modernized Mayek script in 1980. Script politics also play a role in struggles over the naming of places. Should the state officially known as Tripura be written as “ ” (“Tripura” in Bengali) or as “Twipra” (in Kokborok, using Roman script)? How such struggles over the linguistic landscape have affected people’s sense of self and their non-Bengaliness has hardly been studied.

” (“Tripura” in Bengali) or as “Twipra” (in Kokborok, using Roman script)? How such struggles over the linguistic landscape have affected people’s sense of self and their non-Bengaliness has hardly been studied.

Indigeneity

Defiance of Bengali dominance received a new boost in the 1980s with the advent of a global narrative of Indigeneity. This challenged the civilizational hierarchies underlying a well-established South Asian narrative on “tribes” as well as bhadralok assertions of being the primary citizens of the land. Many non-Bengali communities that had been categorized as tribal embraced the idea of being Indigenous peoples. Supported by international campaigns, this global identity category provided a powerful local resource to confront oppression, demand cultural and economic rights, and organize locally, nationally, and internationally. It helped to reverse the imposed speechlessness (“nirbakization”) that indigenous groups had suffered.Footnote72

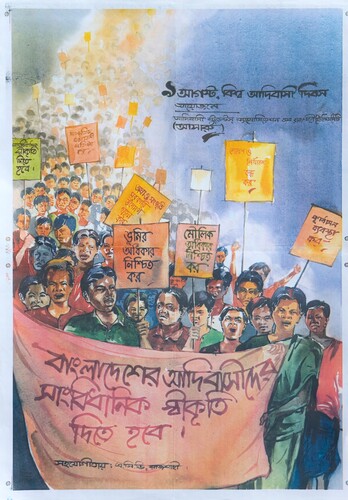

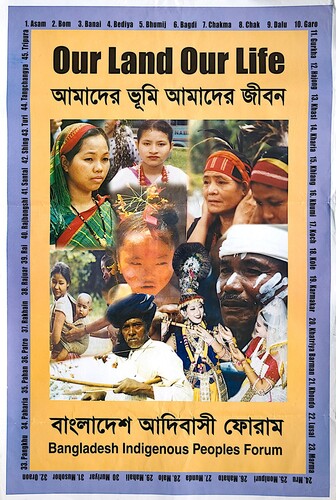

Indigeneity is a concept that the state elites of both Bangladesh and India reject ().Footnote73 Nevertheless it has become an effective tool of self-identification to contest Bengali hegemony and internal colonialism () and has been especially successful in Bangladesh.Footnote74 In West Bengal and Tripura, India’s constitutional safeguards for “scheduled tribes” have caused non-Bengali identity politics to be articulated largely in the idiom of tribal rights.Footnote75

Figure 5. “The Indigenous peoples of Bangladesh must be given constitutional recognition!”. SOURCE: Poster distributed by the Association of Indigenous Students of Rajshahi University on World Indigenous People’s Day.

Figure 6. A poster listing forty-five non-Bengali communities that are united in the Bangladesh Indigenous Peoples Forum.Footnote76 SOURCE: Poster distributed by the Bangladesh Indigenous Peoples Forum.

Assertive Bengaliness

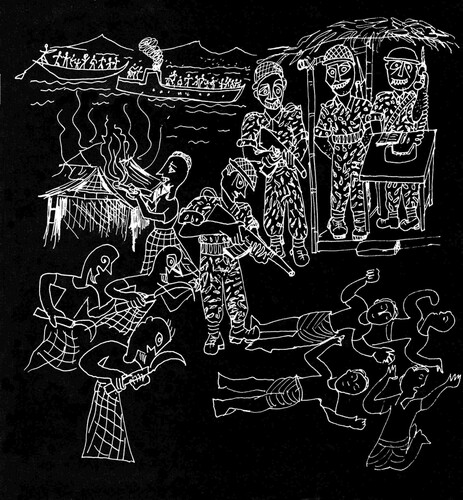

In Bangladesh, West Bengal, and Tripura, assertive Bengaliness has provoked anger among non-Bengalis who perceive it as overbearing, condescending, racist, and against the law.Footnote77 In Bangladesh, the state’s imperious Bengaliness spawned the insurgency in the Chittagong Hill Tracts and countered it with militarization and demographic engineering.Footnote78 Army trucks brought in thousands of Bengali settlers to displace non-Bengalis and eventually outnumber them. Anti-Bengali sentiments and fighting intensified, and today – half a century later – the area remains under tight military rule. The Chittagong Hill Tracts War became well known internationally as a sustained attack on the rights of Indigenous peoples ().

Figure 7. An image of Bangladesh army personnel and Bengali settlers oppressing non-Bengalis in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. SOURCE: Guhathakurta and Van Schendel (eds.) 2013, 408.Footnote79

In neighboring Tripura, large numbers of Hindu migrants from East Bengal sought refuge after 1947. They came to dominate the non-Bengali population, and the Tripura state assertively celebrated genteel Bengaliness (), epitomized by the affectionate relations of the former royal family with Rabindranath Tagore.Footnote80 Resistance took many forms, right from 1947 when the anti-Bengali organization Seng-krak began protesting the displacement of non-Bengalis from their lands. Many confrontations followed and from the 1980s violence became widespread across Tripura, and it continues today.Footnote81

Figure 8. Caption: Celebrating Bengali cultural icons at the University of Tripura, 2011. The Bengali text respectfully commemorates the 150th birthday jubilees of poet Rabindranath Tagore (born in 1861) and spiritual master Vivekananda (born in 1863).Footnote82 Credit: Willem van Schendel.

In West Bengal, resistance to Bengali dominance has taken many forms.Footnote83 It has been especially well documented for the north, where it has had a long history.Footnote84 In Darjeeling district, this culminated in the demand by Nepali speakers for a separate state of Gorkhaland.Footnote85 As a labor union leader told a researcher in 2017:

There was a design. They were expansionists, the Bengalis. From Bangladesh they took over Tripura, then our Jalpaiguri, then Siliguri. There was influx in Assam. Aren’t they expansionists? They are expansionists … These rulers from Kolkata have very colonial designs. Colonial designs! Whenever the demand is raised based on democratic rights to separate from Bengal, they put you in jail.Footnote86

Likewise, speakers of the Kamtapuri (or Rajbangshi) language in northern West Bengal struggled for an autonomous state.Footnote87 In 2018 their campaign had some success when the West Bengal Assembly passed a bill recognizing Kamtapuri as a separate language, thereby dropping previous assertions that it was a Bengali dialect.Footnote88

These moves against assertive Bengaliness have followed the older regional pattern in which language and territory are inextricably connected. Just as in the colonial period, asserting linguistic separateness implies administrative separation from the Bengali heartland.Footnote89 Whether this is framed as a demand for a separate federated state or an autonomous homeland, the goal is the same: spatial emancipation to push back against Bengali hegemonic designs, internal colonialism, and spatial control.Footnote90

Timid Bengaliness

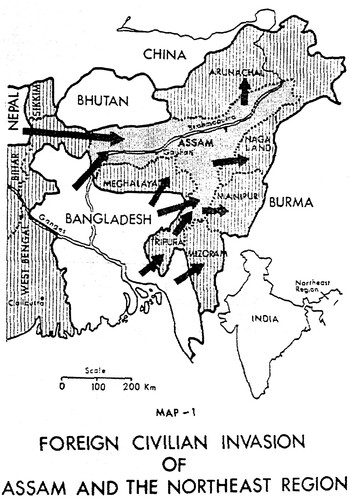

Beyond the linguistic heartland a very different scenario has played out in places where Bengaliness could not count on state support and Bengalis have had to be careful to avoid becoming targets of intimidation. A well-known case is Assam where, starting in the nineteenth century and accelerating after 1947, the inflow of Bengalis became “a key coagulant of Assamese nationalism.”Footnote91 A powerful anti-foreigner movement, focusing on Bengali migrants from East Pakistan/Bangladesh, gathered strength from the 1950s ().Footnote92

Figure 9. Anti-Bengali graffiti on a wall in Dibrugarh, Assam (India), 2004: “Assamese wake up, the Bangladeshis have arrived in Dispur.”Footnote93 Credit: Willem van Schendel.

In post-independence India and Myanmar, the forced removal of Bengali speakers suspected of being migrants from Bangladesh became official practice. The Indian authorities employed push-backsFootnote94 and a succession of administrative tools to expel Bengali non-citizens.Footnote95 In 1948, Burmese armed forces burned hundreds of Rohingya villages, killed thousands, and triggered a large exodus of survivors to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), a brutal pattern of ethnic cleansing that has been repeated several times, most vehemently in 2017 and 2018.Footnote96

In several regions, the post-1947 borders cut local Bengalis off from the Bengali heartland. This was the case in areas of the Indian Republic with large, settled Bengali-speaking populations such as Assam (Cachar, Karimganj, Dhubri), Assam/Meghalaya (Mankachar), and Bihar (Manbhum).Footnote97 After partition, these regions were controlled by non-Bengali elites, and Bengali identities became minoritized and inevitably more fragile and defensive.Footnote98 Feeling victimized, some minoritized Bengali residents as well as aggrieved Bengali migrants from East Pakistan organized around a demand for “Bangalistan.” This irredentist demand invented a Bengali heartland that included territories that had never been considered Bengali before, a postcolonial echo of the colonial-era dream of a Greater Bengal (). It would cover:

… parts of Assam, [the] plains of Meghalaya, West Bengal, Tripura, Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Bihar, and Jharkhand. In fact, its territorial ambitions are international – it wants Nepal’s Jhapa district, Myanmar’s Arakan area, and the whole of Bangladesh.Footnote99

Figure 10. “We demand Bangalistan, a self-sufficient social and economic region.” A slogan by the organization Amra Bangali (We Bengalis) in Agartala, Tripura, India, 2011. Credit: Willem van Schendel.

Figure 11. This map, from a book titled Assam’s Agony, claimed to unveil the “unwritten conspiracy” behind “mass infiltration” from Bangladesh.Footnote100 SOURCE: Van Schendel Citation2005, 196.

Rebuffing Bengaliness

There are many ways in which people can express and enjoy their Bengaliness, and many ways in which others can perceive Bengaliness. I have presented a selection of strategies that non-Bengalis have employed, and continue to employ, to keep Bengali dominance at bay.

Contemporary manifestations of Bengali superiority are rooted in the crafting of a specific genteel vision of Bengali identity some 200 years ago. Like many nationhood projects that emerged worldwide during that period, this vision appeared to provide a strong basis for nation- and state-building.Footnote101 But this potential was never fully realized. The formation of the Bengali nation as a politico-linguistic community (or “people-nation”Footnote102) had fatal flaws that hampered the construction of a unified Bengali nation-state.

This imagined community splintered both externally and internally. Rejections by regional elites in colonial Orissa, Bihar, and Assam imposed distinct spatial boundaries on an envisioned Bengali homeland, and Bengali-speaking Muslim and Dalit activists disputed the right of a small but powerful group of upper-caste Hindus to represent the Bengali linguistic community and to define the Bengali nation. These emancipatory struggles exposed deep fissures among Bengali speakers based on social and ritual exclusion, locality, and economic exploitation.

Despite these tribulations, postcolonial Bengali statehood did take shape. Ironically it bypassed Calcutta, the cradle of genteel Bengaliness. In East Pakistan, Bengaliness emerged as an emancipatory identity that galvanized resistance against the Pakistan state elite. It shaped a robust political community that gained sovereign statehood when Bangladesh became an independent self-ascribed Bengali state in 1971. The 1972 Constitution declared that the Bangladesh state was the receptacle of Bengaliness.Footnote103 Meanwhile, in India, Bengaliness became entrenched in two federal states (West Bengal and Tripura) but had to contend with the overarching project of building a postcolonial Indian nation. In neighboring areas such as Assam, only the timid version of Bengaliness could flourish.

Today, the ideals of many Bengalis throughout the wider region still resonate with the original features of genteel Bengaliness – to be sophisticated, cultured, aware of the wider world, and in possession of delicate sensibilities. But contemporary Bengaliness is no longer recognizably bhadralok or unitary.Footnote104 The end of British rule accelerated the unraveling of this vision. Changing political, economic, and gender relations affected it; new media platforms allowed lower- and middle-class notions of Bengali culture to circulate; and diasporic connections challenged parochialism. Throughout the post-1947 period, and increasingly hard to ignore, non-Bengalis emancipated themselves. They pushed back against self-congratulatory views of Bengaliness and exposed these masked colonial attitudes, oppressive practices, and willful refusals to listen. Bengali cultural pride and self-assurance began to give way to more complex feelings, including nostalgia and a sense of being embattled. Little by little, genteel Bengaliness lost its grip on postcolonial generations of Bengalis as they redefined and reworked their Bengaliness.Footnote105 Introspection led some to empathize with non-Bengalis and deal with them on a more equal footing.

And yet, postcolonial power elites sought to define the territories of West Bengal, Bangladesh, and Tripura as essentially Bengali spaces, thereby hijacking Bengaliness for their own ends and triggering a range of militant counter-hegemonic movements.Footnote106 In these territories, current state narratives posit Bengaliness as the ageless identity core for all Bengali-speakers, not as the historically contingent and malleable idea that I have explored in this article. Non-Bengali elites – who interpret this “state Bengaliness” as an ideology of oppression – engage in forceful identity politics to mobilize support against their Bengali counterparts. They use ethnic and linguistic symbols, often presented in equally ahistorical narratives, to frame their struggles for economic resources and political power.Footnote107

Such identity politics benefit from several new tools. In the heartland of majoritarian Bengaliness, non-Bengalis feel empowered by global narratives of Indigeneity and internal colonialism. These encourage non-Bengalis to work together and jointly assert their identities (). In this way, global developments fortify local initiatives that in turn generate new national and international inter-ethnic alliances.Footnote108

Beyond the Bengali heartland, cross-border Bengali migrants continue to be defined as unauthorized intruders, and longstanding Bengali-speaking residents must prove their bona fides as citizens.Footnote109 Violent confrontations in the form of riots, pogroms, lynchings, rapes, massacres, and acts of genocide are well documented.Footnote110 In these clashes, non-Bengalis sometimes join forces with state armies, for example, Rakhine Buddhist communities that participated in the mass expulsion of Rohingyas in Myanmar.Footnote111

These identity politics have modified Bengaliness. Whereas the colonial Bengali-Odia-Assamese-Hindi conflict was a clash of elite worldviews, postcolonial Bengaliness has involved the legal, ideological, and armed forces of sovereign states, as well as confrontations over scarce resources between lower-class Bengalis and non-Bengalis.Footnote112

Today, conversations between Bengalis and non-Bengalis are often ill-disposed. Individual interactions between Bengalis and non-Bengalis may, of course, be friendly and trusting, but the prevailing political climate mitigates against this. State-driven assertive Bengaliness frustrates productive coexistence and feeds violent confrontations, ultimately victimizing both non-Bengalis and Bengalis. In this cauldron of identity politics, new people-nations are wrought: Gorkha, Jumma, Kamtapuri, Kokborok, Marma, Mro, and more. Their identity politics vary but these movements share an urge to keep Bengaliness at bay. They are exemplars of a connected transnational history of rebuffing Bengali dominance.Footnote113 Such rebuffing strategies parallel those of many other minoritized communities around the world. This points to the urgency of a research agenda on Bengaliness that overcomes both the blinkers of methodological nationalism and the failure to incorporate non-Bengali inputs, responses, and impacts.

Even though non-Bengali voices have made growing numbers of Bengalis rethink notions of Bengali superiority (and made NGOs step up their efforts to serve non-Bengalis), assertive Bengaliness remains the narrative of internal colonialism throughout the region. Political and economic elites routinely weaponize it as they target non-Bengali groups in both India and Bangladesh. Faced with state policies that persistently deny non-Bengalis their civil and cultural rights, many non-Bengali activists are convinced that rebuffing Bengali dominance has become a matter of life and death.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Meghna Guhathakurta, Ellen Bal, and Malini Sur for their insightful comments, and Yasmin Saikia for help with translating from Assamese.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Willem van Schendel

Willem van Schendel works in the fields of history, anthropology, and the sociology of Asia. His recent books related to the theme of this article include Flows and Frictions in Trans-Himalayan Spaces: Histories of Networking and Border Crossing (Amsterdam University Press, 2022; edited with Gunnel Cederlöf) and A History of Bangladesh (Cambridge University Press, second edition, 2020). A list of his publications can be found at uva.academia.edu/WillemVanSchendel.

Notes

1 The term “non-Bengali” covers a range of self-identifications that share only an awareness of not being Bengali.

2 The origin of the word “Bangla” is unclear. It is usually assumed to be derived from “Vanga” and “Vangala,” found in early Sanskrit texts. These words referred to people and lands beyond the direct knowledge of the writers, somewhere in what we now call Bengal. The languages then spoken in these lands were unrelated to the Bengali language but have left traces in it. Today, Bangla denotes both the region of Bengal (roughly, West Bengal in India and Bangladesh) and the Bengali language. See Chatterji Citation1926, 62–69; Chakrabarti and Chakrabarti Citation2013, 32–34.

3 Alexander, Chatterji, and Jalais Citation2016.

4 In the first comprehensive survey of the language, Grierson gave an overview of different speech forms and their names. Although he acknowledged that it was impossible to establish linguistic boundaries, he identified over twenty vernaculars as dialects of Bengali. Some of Grierson’s dialects are now often treated as separate languages, for example, Chakma, Chittagonian, Sylheti/Siloti, Hajong, and Rohingya. See Grierson Citation1903, I, ii, 12, 17–9, 214; Guts Citation2013.

5 “Bengaliness” is a translation of the Bengali words  (bangalitto) and বাঙালিয়ানা (bangaliana).

(bangalitto) and বাঙালিয়ানা (bangaliana).

6 Middleton Citation2020.

7 British colonial rule ended in 1947 and Bengali-speaking regions in India have developed a postcolonial Bengaliness since then. But over sixty percent of Bengali speakers became citizens of Pakistan. According to some historians, they came under renewed colonial rule, now by a West Pakistani elite, until 1971.

8 Kar Citation2008, 30. See also Grierson Citation1903, I, 14, 17; Iqbal Citation2020.

9 For example, adda, “the practice of friends getting together for long, informal, and unrigorous conversations … Adda is often seen as something quin[t]essentially Bengali, as an indispensable part of the Bengali character or as an integral part of such metaphysical notions as ‘life’ and ‘vitality’ for the Bengalis.” Chakrabarty Citation1999, 110. See also Janeja Citation2010, 119–126; Sen Citation2011.

10 Other English terms used for the bhadralok are literati or intelligentsia, but the category was broader and more complex, and it changed over time.

11 Ghosh Citation2004, Citation2016; Dasgupta Citation2018.

12 Chatterji Citation2001, 299. The Permanent Settlement was the land tax system that formed the bedrock of British rule in Bengal.

13 Bandyopadhyay Citation1997a, 45–46.

14 High-caste Hindus have always formed a small but ritually and culturally privileged group among Hindus. And Hindus were (and still are) a minority among Bengali speakers. Most Bengalis are Muslims (a fact that did not register until the first population census in 1872) and smaller groups identify as Christians, Buddhists, and followers of other religions.

15 For introductions, see Hashmi Citation1992; Iqbal Citation2009; Bose Citation2014; Daechsel Citation2015.

16 For introductions, see Bandyopadhyay Citation1990, Citation1997b, Citation2004; Basu Citation2003; Sarkar Citation2005.

17 Basu Citation2010, 79; Bhattacharya Citation2014; Gupta Citation2017; Mukharji Citation2017.

18 At a time when colonial discourse often restricted the term “Bengali” to caste Hindus, many Banglaphone Muslim and Dalit activists aspired to being explicitly accepted as Bengalis.

19 For example, the Maharajas of Cooch Behar and Tripura, and the Chakma Rajas.

20 Kar Citation2008, 65. See also Mishra Citation2020, 48–61; Jha Citation2020.

21 Some Bengali-speaking regions spilled over the administrative borders of colonial Bengal, however, such as Sylhet and Cachar in Assam.

22 An influential version of “Greater Bengal” is articulated in Sen Citation1935.

23 Ludden Citation2012.

24 Kar Citation2008, 55.

25 Ludden Citation2012, 493.

26 Sarkar Citation1973; Silvestri Citation2009.

27 Chatterji Citation2002, 260. See also Aiyar Citation2008; Ghosh Citation2017, 355–366.

28 Janeja Citation2010.

29 Higher-caste Hindus migrated to India first, followed by Dalits. See Bandyopadhyay and Basu Ray Chaudhury Citation2022.

30 Ludden Citation2022.

31 Shamshad Citation2017; Chatterjee Citation2020a. Manpreet Janeja (Citation2010) analyzes the divergence of contemporary Bengaliness (bangalitto) in Bangladesh and West Bengal. See Feldman Citation2021.

32 Rounaq Jahan (Citation1972) characterized this new East Bengali middle class as a “vernacular elite”. See Newbold Citation2021.

33 Anisuzzaman Citation2008; Khondker, Muurlink, and Ali Citation2022.

34 Murshid Citation2022. For a brief introduction to literature on the war, see Van Schendel Citation2020, 131–138.

35 Jones Citation2011.

36 Chakrabarty Citation2004; Ghosh Citation2016; Dasgupta Citation2018; Roy Citation2019; Chakraborty Paunksnis Citation2021.

37 For more on the imperial disdain for the bhadralok lifestyle, see Rosselli Citation1980; Sinha Citation1995; Dutta Citation2021.

38 Van Schendel Citation1992; Bal Citation2007; Chettri Citation2017.

39 For example, the 1873 Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation, the 1900 Chittagong Hill Tracts Regulation, and the 1935 Government of India Act.

40 Middleton Citation2020, 34.

41 Chakrabarty and Jha Citation2022; Feldman Citation2021; Sur Citation2021.

42 The text (in Bengali) reads: “We demand a court judgement on the murder of indigenous leader Martyr Alfred Soren. Bangladesh Indigenous Union.” See Rozario Citation2020; Van Schendel Citation2020, 248–249.

43 Partha Chatterjee employed this term to analyze Bengali cultural resistance to British rule: “The bilingual intelligentsia came to think of its own language as belonging to that inner domain of cultural identity, from which the colonial intruder had to be kept out.” Chatterjee Citation1993, 7.

44 For example, Tun Citation2015; Bal Citation2010; Besky Citation2017; Mukherjee Citation2020; Hoque Citation2022, chapter 5.

45 Mahato Citation2000; Roy Citation2015; Sen Citation2022.

46 Brandt and Sohoni Citation2018; Brandt Citation2020a.

47 Brandt Citation2014, 86.

48 Kurzon Citation2010; Mandal Citation2014; d’Hubert Citation2014, 338–346; d’Hubert Citation2020; Brandt Citation2020a, 17–21; Brandt Citation2021.

49 Not all scripts are, however. Lepcha (spoken by some 30,000 people in northern Bengal) has its own script, presumably developed in the eighteenth century.

50 At least three regional styles of writing Eastern Nagari (western, northern, eastern) could be distinguished before printing began to standardize texts. d’Hubert Citation2014, 336–338.

51 There were also cases of “script persistence.” These included Burmese script (Marma in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, and Rakhaing in Patuakhali and Cox’s Bazar), Armenian script (Armenians), and Urdu script (urban elites and post-1947 migrants).

52 Brandt Citation2018, 125.

53 Brandt Citation2018, 127.

54 Brandt Citation2018, 134.

55 Chakma Citation2010; Siddiqi Citation2018, 246–249.

56 Mohsin Citation2003; Bal Citation2010; Yasmin Citation2014; Brandt Citation2020b; Sultana Citation2021; Guhathakurta Citation2022.

57 Van Schendel Citation2020; 245–250.

58 Brandt Citation2018.

59 d’Hubert Citation2014, 340–347; Simard, Dopierala, and Thaut Citation2020.

60 A script for Garo, A·chik Tok·birim, was invented in 1979 but it remains marginal compared to the Roman script.

61 Pappuswamy Citation2017.

62 Singha Citation2002; Debnath Citation2013; Historial Citation2013; Brandt Citation2014, 89–91; Brandt Citation2020a, 13–14; Choksi Citation2021.

63 Sarkar CitationForthcoming.

64 Pandey Citation2016.

65 Brauns and Löffler Citation1990, 235–236. See Pachuau and van Schendel Citation2022; 86.

66 Mahmud Citation2007, 140; Uddin Citation2008. See Narzary Citation2013.

67 Anderson Citation2019.

68 Published by permission from Save the Children UK, London.

69 Bostock Citation1997.

70 Shohamy Citation2006, 110; Gorter Citation2006.

71 Bengali signs were most dominant after Bangladesh’s independence in 1971. As English emerged as the language of prestige education, English signs became more prominent – and more Arabic signs signaled the reemergence of public expressions of Islam.

72 Mahato Citation2000. In Bengali, nirbak means speechless. In West Bengal another identity project invented “mulnibasi” for autochthonous inhabitants belonging to the legal categories of “scheduled tribes,” “scheduled castes,” “other backward classes,” and religious minorities. See Roy Citation2015.

73 Gerharz Citation2014; Alamgir Citation2016, 215–217; Brandt Citation2020b. In 2019, the Bangladesh government directed all registered organizations to delete the terms “indigenous” and “adibashi.” The Indigenous World 2020, Citation2020, 203–204. See also Uttom Citation2022.

74 Uddin Citation2019.

75 Chhetri Citation2021; Debbarma Citation2021. But compare this with Thami Citation2020.

76 The poster equates “Indigenous” with the Bengali word adibashi (original inhabitant, autochthon).

77 For examples, see Datta Citation2015, 97–143; Roy Citation2015; Ghoshal Citation2017; Ahmed Citation2017, 114–115; Braithwaite and D’Costa Citation2018, 345; Datta Citation2019; Jamatia and Gundimeda Citation2019.

78 Mohsin Citation2003; Adnan Citation2008; Alamgir Citation2016; Bal and Siraj Citation2017; Braithwaite and D’Costa Citation2018, 321–362.

79 Cover of a locally published booklet, Chitkar (The Scream), which commemorated the 1993 Naniarchar massacre. The artist was not acknowledged.

80 Jamatia and Gundimeda Citation2019; Ghoshal Citation2021, 140–155.

81 Bhattacharjee Citation1989, 127–134; Bhattacharyya Citation1989; Van Schendel Citation2005, 194–195, 203–204; Debbarma Citation2021.

82 The text reads: “Tripura University offers reverent obeisance to master poet Rabindranath on his 150th anniversary and to Swami Vivekananda on the eve of his 150th anniversary.”

83 For some political movements, see Duyker Citation1987; Ghosh Citation1993; Chhetri Citation2021.

84 Chettri Citation2017, 45–57; Chhetri Citation2018; Middleton Citation2021.

85 Chettri Citation2017, 82.

86 Middleton Citation2020, 40.

87 Native speakers and linguists have identified this speech by other names as well: Rangpuri, Koch, Bahe, Kamta, and Kamrupi. See Misra Citation2006; Toulmin Citation2009, 1–13; Nandi Citation2014; Rajbansi–Bengali Citation2014.

88 See Basistha Citation2016, 673. In fact, the Assembly recognized it as two languages: “Rajbangshi” and “Kamtapuri.”

89 In the colonial period, anti-Bengali emancipation movements in Orissa, Assam, and Bihar (see ) had successfully resisted the dominance of the Bengali language in their territories and replaced it with alternative languages for education and officialdom.

90 Basistha Citation2016, 667; Chakravarti Citation2017; Middleton Citation2020, 32–33.

91 Sen Citation2021, 4.

92 Three phases of this movement are known as Bongal Kheda (“Drive Out the Foreigners”), the Assamese Language Movement, and the Assam Movement. See Goswami Citation2014; Ahmed Citation2014; Murshid Citation2016; Ghoshal Citation2021, 126–138, 200–222; Saikia CitationForthcoming.

93 Dispur is the capital of Assam. The slogan was signed by the All-Assam Students Union (AASU). I would like to thank Yasmin Saikia for helping me translate this Assamese text.

94 Van Schendel Citation2005, 197–200, 222–226.

95 Death by Paperwork Citation2021.

96 The Myanmar government classifies Rohingyas as Bengali/Bangladeshi immigrants, a label that Rohingyas reject. See Farzana Citation2017.

97 In the 1950s, Bengali-speaking parts of Manbhum were added to the state of West Bengal and became Purulia district.

98 Baruah Citation2020; Dubochet Citation2022.

99 Roy Citation2008.

100 Das Citation1982, 41, 31, 169; Ghoshal Citation2021. See Van Schendel Citation2005, 194–198.

101 For examples, Chatterjee Citation2020b, 25–30.

102 Chatterjee Citation2020b, 31–71, 86–89, 107–111.

103 It stated: “The unity and solidarity of the Bangalee nation, which, deriving its identity from its language and culture, attained sovereign and independent Bangladesh through a united and determined struggle in the war of independence, shall be the basis of Bangalee nationalism.” See Siddiqi Citation2018.

104 Ghosh Citation2017.

105 Chakrabarty Citation2004; Chakraborty Citation2014; Bhattacharya Citation2019; Bhattacharya Citation2022.

106 Mohsin Citation2003.

107 This model of “fixed Bengaliness” is mirrored by equally fixed, timeless models of identity among many non-Bengali activists. There are important parallels between these ahistorical models of ethnic identity and the fixed identities projected by religious identity movements – Islamism and Hindutva – that are presently confronting state Bengaliness in both Bangladesh and India. Highly relevant for contemporary politics, these are largely intra-Bengali in nature.

108 For example, Kapaeeng Foundation and International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA).

109 Sur Citation2021. In the Chittagong Hill Tracts – beyond the Bengali heartland but inside the Bangladesh territory – non-Bengalis distinguish clearly between the small, long-settled local Bengali community and the new immigrants and armed forces.

110 Mohaiemen Citation2010; Kimura Citation2013; Wouters Citation2022.

111 Simpson and Farrelly Citation2021, 249–264; Than and May Citation2022.

112 For case studies, Kimura Citation2013; Alamgir Citation2016; Bal and Siraj Citation2017; Sur Citation2019, Citation2021.

113 Rebuffing Bengaliness also takes place among non-Bengalis who distinguish between members of their own group being more, or less, “Bengalized.” Bal and Claquin Chambugong Citation2014.

References

- Adnan, Shapan. 2008. “Contestations Regarding Identity, Nationalism and Citizenship during the Struggles of the Indigenous Peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh.” International Review of Modern Sociology 34 (1): 27–45.

- Ahmed, Bokhtiar. 2017. “Beyond Checkpoints: Identity and Developmental Politics in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh.” PhD thesis, Australian Catholic University.

- Ahmed, Rafiul. 2014. “Anxiety, Violence and the Postcolonial State: Understanding the ‘Anti-Bangladeshi’ Rage in Assam, India.” Perceptions 19 (1): 55–70.

- Aiyar, Sana. 2008. “Fazlul Huq, Region and Religion in Bengal: The Forgotten Alternative of 1940–43.” Modern Asian Studies 42 (6): 1213–1249.

- Alamgir, Fariba. 2016. “Land Politics in Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh: Dynamics of Property, Identity and Authority.” PhD thesis, University of East Anglia.

- Alexander, Claire, Joya Chatterji, and Annu Jalais. 2016. The Bengal Diaspora: Rethinking Muslim Migration. London: Routledge.

- Anderson, Deborah. 2019. “Proposal for Encoding the Toto Script in the SMP of the UCS.” Accessed August 27, 2022: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/94c1m9w5.

- Anisuzzaman. 2008. “Claiming and Disclaiming a Cultural Icon: Tagore in East Pakistan and Bangladesh.” University of Toronto Quarterly 77 (4): 1058–1069.

- Bal, Ellen. 2007. They Ask if We Eat Frogs: Garo Ethnicity in Bangladesh. Singapore/Leiden: ISEAS/IIAS.

- Bal, Ellen. 2010. “Taking Root in Bangladesh.” The Newsletter (International Institute of Asian Studies) 53: 24–25.

- Bal, Ellen, and Timour Claquin Chambugong. 2014. “The Borders that Divide, the Borders that Unite: (Re)interpreting Garo Processes of Identification in India and Bangladesh.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 29 (1): 95–109.

- Bal, Ellen, and Nasrin Siraj. 2017. “‘We are the True Citizens of This Country’: Vernacularisation of Democracy and Exclusion of Minorities in the Chittagong Hills of Bangladesh.” Asian Journal of Social Science 45: 666–692.

- Bandyopadhyay, Debaprasad. 1997a. “Colony’s Burden: A Case of Extending Bangla.” Aligarh Journal of Linguistics 5 (1): 40–55.

- Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar. 1990. Caste, Politics, and the Raj: Bengal 1872–1937. Calcutta: K.P. Bagchi.

- Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar. 1997b. Caste, Protest, and Identity in Colonial India: The Namasudras of Bengal, 1872–1947. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press.

- Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar. 2004. Caste, Culture and Hegemony: Social Dominance in Colonial Bengal. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar, and Anasua Basu Ray Chaudhury. 2022. Caste and Partition in Bengal: The Story of Dalit Refugees, 1946–1961. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Baruah, Sanjib. 2020. In the Name of the Nation: India and its Northeast. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Basistha, Nandini. 2016. “Confusing Identity, Overlapping Demands, and Conflict in Leadership: A Deep Probe into the Problem of Rajbanshi-led Movements in North Bengal.” Indian Journal of Public Administration 62 (3): 667–683.

- Basu, Swaraj. 2003. Dynamics of a Caste Movement: The Rajbansis of North Bengal, 1910–1947. New Delhi: Manohar.

- Basu, Subho. 2010. “The Dialectics of Resistance: Colonial Geography, Bengali Literati and the Racial Mapping of Indian Identity.” Modern Asian Studies 44 (1): 53–79.

- Besky, Sarah. 2017. “The Land in Gorkhaland: On the Edges of Belonging in Darjeeling, India.” Environmental Humanities 9 (1): 18–39.

- Bhattacharjee, S. R. 1989. Tribal Insurgency in Tripura: A Study in Exploration of Causes. New Delhi: Inter-India Publications.

- Bhattacharya, Sabyasachi. 2014. The Defining Moments in Bengal: 1920–1947. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Bhattacharya, Binayak. 2019. “Seeing Kolkata: Globalization and the Changing Context of the Narrative of Bengali-ness in Two Contemporary Films.” Asia 73 (3): 559–574.

- Bhattacharya, Parimal. 2022. Field Notes from a Waterborne Land: Bengal beyond the Bhadralok. Gurugram: HarperCollins Publishers India.

- Bhattacharyya, Harihar. 1989. “The Emergence of Tripuri Nationalism, 1948–1950.” South Asia Research 9 (1): 54–71.

- Bose, Neilesh. 2014. Recasting the Region: Language, Culture, and Islam in Colonial Bengal. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Bostock, William W. 1997. “Language Grief: A ‘Raw Material’ of Ethnic Conflict.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 3 (4): 94–112.

- Braithwaite, John, and Bina D’Costa. 2018. Cascades of Violence: War, Crime and Peacebuilding across South Asia. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Brandt, Carmen. 2014. “Script as a Potential Demarcator and Stabilizer of Languages in South Asia.” In Language Endangerment and Preservation in South Asia, edited by Hugo C. Cardoso, 78–99. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

- Brandt, Carmen. 2018. “Writing off Domination: the Chakma and Meitei Script Movements.” South Asian History and Culture 9 (1): 116–140.

- Brandt, Carmen. 2020a. “From a Symbol of Colonial Conquest to the Scripta Franca: The Roman Script for South Asian Languages.” In Wege durchs Labyrinth: Festschrift zu Ehren von Rahul Peter Das, edited by Carmen Brandt and Hans Harder, 1–36. Heidelberg: CrossAsia-eBooks.

- Brandt, Carmen. 2020b. “Projecting and Rejecting Indigeneity: ‘From Bangladesh with Love’.” In Media, Indigeneity and Nation, edited by Markus Schleiter and Erik de Maaker, 150–170. London: Routledge.

- Brandt, Carmen. 2021. “Why Dots and Dashes Matter: Writing Bengali in Roman Script.” In “Das alles hier”: Festschrift für Konrad Klaus zum 65. Geburtstag, edited by Ulrike Niklas, Heinz Werner Wessler, Peter Wyzlic, and Stefan Zimmer, 23–54. Heidelberg/Berlin: CrossAsia-eBooks.

- Brandt, Carmen, and Pushkar Sohoni. 2018. “Script and Identity: The Politics of Writing in South Asia: An Introduction.” South Asian History and Culture 9 (1): 1–15.

- Brauns, Claus-Dieter, and Lorenz G. Löffler. 1990. Mru: Hill People on the Border of Bangladesh. Basel etc.: Birkhäuser Verlag.

- Chakma, Bhumitra. 2010. “The Post-colonial State and Minorities: Ethnocide in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh.” Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 48 (3): 281–300.

- Chakrabarti, Kunal, and Shubhra Chakrabarti. 2013. Historical Dictionary of the Bengalis. Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press.

- Chakrabarty, Anindita, and Manish K. Jha. 2022. “Social Construction of Migrant Identities: Everyday Life of Bangladeshi Migrants in West Bengal.” Community Development Journal 57 (4): 731–749.

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 1999. “Adda, Calcutta: Dwelling in Modernity.” Public Culture 11 (1): 109–145.

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2004. “Romantic Archives: Literature and the Politics of Identity in Bengal.” Critical Inquiry 30 (3): 654–682.

- Chakraborty, Mridula Nath, ed. 2014. Being Bengali: At Home and in the World. London: Routledge.

- Chakraborty Paunksnis, Runa. 2021. “Bengali Dalit Literature and the Politics of Recognition.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 44 (5): 817–833.

- Chakravarti, Sudeep. 2017. “Twipraland Demand: Legitimate Agitation for Separate Tribal State in Tripura or BJP Grab to Topple CPM Govt?” Firstpost, July 17. Accessed August 27, 2022. https://www.firstpost.com/politics/twipraland-demand-legitimate-agitation-for-separate-tribal-state-in-tripura-or-bjp-grab-to-topple-cpm-govt-3822581.html.

- Chatterjee, Partha. 1993. The Nation and Its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Chatterjee, Partha. 2020a. “When Victims Become Rulers: Partition, Caste, and Politics in West Bengal.” In Dipesh Chakrabarty and the Global South: Subaltern Studies, Postcolonial Perspectives, and the Anthropocene, edited by Saurabh Dube, et al. 105–121. London: Routledge.

- Chatterjee, Partha. 2020b. I am the People: Reflections on Popular Sovereignty Today. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Chatterji, Joya. 2001. “The Decline, Revival and Fall of Bhadralok Influence in the 1940s: A Historiographic Review.” In Bengal: Rethinking History – Essays on Historiography, edited by Sekhar Bandyopadhyay, 297–315. New Delhi: Manohar and International Center for Bengal Studies.

- Chatterji, Joya. 2002. Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932-1947. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chatterji, Suniti Kumar. 1926. The Origin and Development of the Bengali Language. Calcutta: Calcutta University Press.

- Chettri, Mona. 2017. Ethnicity and Democracy in the Eastern Himalayan Borderland. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Chhetri, Nilamber. 2018. “The Quest to Belong and Become: Ethnic Associations and Changing Trajectories of Ethnopolitics in Darjeeling.” In Darjeeling Reconsidered: Histories, Politics, Environments, edited by Townsend Middleton and Sara Shneiderman, 154–176. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chhetri, Nilamber. 2021. “Tribal Politics in West Bengal: Quest for Identity and Recognition.” In Handbook of Tribal Politics in India, edited by Jagannath Ambagudia and Virginius Xaxa, 525–541. Los Angeles.: Sage.

- Choksi, Nishaant. 2021. Graphic Politics in Eastern India: Script and the Quest for Autonomy. Delhi: Bloomsbury Academic Indika.

- Daechsel, Markus. 2015. “Review of Recasting the Region: Language, Culture and Islam in Colonial Bengal, by Neilesh Bose” (review no. 1871). Reviews in History: 1-5. Accessed August 27, 2022. http://www.history.ac.uk/reviews/review/1871.

- Das, Amiya Kumar. 1982. Assam’s Agony: A Socio-Economic and Political Analysis. New Delhi: Lancers Publishers.

- Dasgupta, Supurna. 2018. “(When) Did the Bhadralok Die?” Society and Culture in South Asia 4 (1): 176–178.

- Datta, Ranjan. 2015. “Land-Water Management and Sustainability: An Indigenous Perspective in Laitu Khyang Community, Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT), Bangladesh.” PhD thesis, University of Saskatchewan.

- Datta, Ranjan. 2019. “Implementation of Indigenous Environmental Heritage Rights: An Experience with Laitu Khyeng Indigenous Community, Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh.” AlterNative 15 (4): 309–20.

- Death by Paperwork: Determination of Citizenship and Detention of Alleged Foreigners in Assam. 2021. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Law School.

- Debbarma, R. K. 2021. “Tribal Politics in Tripura: A Spatial Perspective.” In Handbook of Tribal Politics in India, edited by Jagannath Ambagudia and Virginius Xaxa, 501–512. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Debnath, Rupak. 2013. “Kokborok Language Planning and Development.” In Report of the Seminar on Language Planning for Development of Kokborok, 32–40. Agartala: Tribal Research and Cultural Institute.

- d’Hubert, Thibaut. 2014. “La diffusion et l’usage des manuscrits bengalis dans l’est du Bengale, XVIIe-XXe siècles.” Eurasian Studies 12: 325–356.

- d’Hubert, Thibaut. 2020. “” [The Forgotten Texts of the Regional Tongue: Bengali Manuscripts in Arabic Script].” ভাবনগর 12 (13–14): 1447–1462.

- Dubochet, Lucy. 2022. “Citizenship as Burden of Proof: Voting and Hiding Among Migrants from India’s Eastern Borderlands.” Citizenship Studies 26 (6): 1–17.

- Dutta, Sutapa. 2021. “Packing a Punch at the Bengali Babu.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 44 (3): 437–458.

- Duyker, Edward. 1987. Tribal Guerrillas: The Santals of West Bengal and the Naxalite Movement. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Farzana, Kazi Fahmida. 2017. Memories of Burmese Rohingya Refugees: Contested Identity and Belonging. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Feldman, Shelley. 2021. “Displacement and the Production of Difference: East Pakistan/Bangladesh, 1947–1990.” Globalizations 19 (2): 187–204.

- Gerharz, Eva. 2014. “What is in a Name? Indigenous Identity and the Politics of Denial in Bangladesh.” Südasien-Chronik - South Asia Chronicle 4: 115–137.

- Ghosh, Arunabha. 1993. “Jharkhand Movement in West Bengal.” Economic and Political Weekly 28 (3/4): 121–127.

- Ghosh, Parimal. 2004. “Where Have All the ‘Bhadraloks’ Gone?” Economic and Political Weekly 39 (3): 247–251.

- Ghosh, Parimal. 2016. What Happened to the Bhadralok? Delhi: Primus Books.

- Ghosh, Semanti. 2017. Different Nationalisms: Bengal, 1905-1947. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Ghoshal, Anindita. 2017. “Tripura: A Chronicle of Politicisation of the Refugees and Ethnic Tribals.” Development and Change 14 (2): 27–41.

- Ghoshal, Anindita. 2021. Refugees, Borders and Identities: Rights and Habitat in East and Northeast India. London: Routledge.

- Gorter, Durk. 2006. “Introduction: The Study of the Linguistic Landscape as a New Approach to Multilingualism.” International Journal of Multilingualism 3 (1): 1–6.

- Goswami, Uddipana. 2014. Conflict and Reconciliation: The Politics of Ethnicity in Assam. London: Routledge.

- Grierson, George A. 1903. Linguistic Survey of India, Vol. V. Indo-Aryan Family – Eastern Group. Calcutta: Government Printing.

- Guhathakurta, Meghna. 2022. “The Making of Minorities in Bangladesh: Legacies, Policies and Practice.” In The Emergence of Bangladesh: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Khondker, et al., 109–133. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Guhathakurta, Meghna, and Willem van Schendel, eds. 2013. The Bangladesh Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Gupta, Swarupa. 2017. Cultural Constellations, Place-making and Ethnicity in Eastern India, c. 1850–1927. Leiden: Brill.

- Guts, Lisa. 2013. “Phonological Description of the Hajong Language.” In North East Indian Linguistics, Volume 4, edited by Gwendolyn Hyslop et al., 216–239. Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

- Hashmi, Taj ul-Islam. 1992. Pakistan as a Peasant Utopia: The Communalization of Class Politics in East Bengal, 1920-1947. London: Routledge.

- “Historial [sic] Back Ground of Kokborok Script: Past, Today & Tomorrow”. 2013. Agartala: Tripura University.

- Hoque, Farhana. 2022. “From Hybridity to Singularity: The Distillation of a Unique Buddhist Identity on the Borderlands of South and Southeast Asia.” PhD thesis, University College London.

- The Indigenous World 2020. 2020. Copenhagen: International Working Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA).

- Iqbal, Iftekhar. 2009. “Return of the Bhadralok: Ecology and Agrarian Relations in Eastern Bengal, c. 1905–1947.” Modern Asian Studies 43 (6): 1325–53.

- Iqbal, Iftekhar. 2020. “Bengal Delta.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. Accessed August 27, 2022. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.19.

- Jahan, Rounaq. 1972. Pakistan: Failure in National Integration. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Jamatia, Fancy, and Nagaraju Gundimeda. 2019. “Ethnic Identity and Curriculum Construction: Critical Reflection on School Curriculum in Tripura.” Asian Ethnicity 20 (3): 312–329.

- Janeja, Manpreet Kaur. 2010. Transactions in Taste: The Collaborative Lives of Everyday Bengali Food. New Delhi: Routledge.

- Jha, Sneha. 2020. “Bringing Order to Chaos: The Appropriation of Maithili by Colonial State, c. 1870s–1940s.” Indian Historical Review 46 (2): 227–246.

- Jones, Reece. 2011. “Dreaming of a Golden Bengal: Discontinuities of Place and Identity in South Asia.” Asian Studies Review 35 (3): 373–395.

- Kar, Bodhisattva. 2008. “‘Tongue Has No Bone’: Fixing the Assamese Language, c. 1800-c. 1930.” Studies in History 24 (1): 27–76.

- Khondker, Habibul, Olav Muurlink, and Asif Bin Ali, eds. 2022. The Emergence of Bangladesh: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kimura, Makiko. 2013. The Nellie Massacre of 1983: Agency of Rioters. New Delhi, etc.: Sage.

- Kurzon, Dennis. 2010. “Romanisation of Bengali and Other Indian Scripts.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society series 3 20 (1): 61–74.

- Ludden, David. 2012. “Spatial Inequity and National Territory: Remapping 1905 in Bengal and Assam.” Modern Asian Studies 46 (3): 483–525.

- Ludden, David. 2022. “Spatial History in Southern Asia: Mobility, Territoriality, and Religion.” In Flows and Frictions in Trans-Himalayan Spaces: Histories of Networking and Border Crossing, edited by Gunnel Cederlöf and Willem van Schendel, 29–50. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.