Internationally renowned historian and antiwar activist Ngô Vĩnh Long died at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Bangor, Maine on October 12, 2022, at the age of seventy-eight. A professor of History at the University of Maine from 1985 until his death, Dr. Long was a leading scholar of the Vietnam/Indochina War and of the history of Vietnam from ancient times through French colonialism and US neocolonialism, postwar Vietnam, US-Vietnam relations, and Southeast and East Asia, especially China.

From his undergraduate years at Harvard until the end of his life, Ngô Vĩnh Long was a courageous intellectual activist and an activist intellectual. He often described himself as a proud Vietnamese patriot who cared deeply about Vietnam, its past, and its suffering, as well as about the United States, his second home. Even in the darkest of times, he maintained his vision and hope for a much better Vietnam, a more egalitarian US, and much better US-Vietnam relations.

Long sometimes described himself and was considered by some others as a pacifist. This is accurate if by “pacifist” we mean an opponent of war and a promoter of peace, reconciliation, and justice. But Professor Long was not the kind of pacifist who would uncompromisingly and openly condemn all expressions of violence, such as those exerted by Vietnamese anti-colonial and anti-imperialist revolutionaries, who were not always nonviolent in their struggles for freedom and independence. At the same time, he always worked to offer alternatives to violent responses to oppression, exploitation, and domination.

Much of Ngô Vĩnh Long’s scholarly and activist priorities and commitments can be traced back to formative influences in his family upbringing and his youthful experiences in Vietnam. These influences and experiences shaped his commitment to speak truth to power. From his youth until the end of his life, Long was profoundly moved by the human-caused suffering of Vietnamese people, which he dedicated his life to alleviating. He believed in providing independent analyses regardless of the personal, career, and other risks he faced from those in Vietnam and in the United States challenged by his interpretations and actions. He had an unshakable commitment to study and educate others about the violent and unjust economic, political, and cultural realities of French colonialism, US neocolonialism, Chinese imperialism, and other expressions of domination in the contemporary world.

In taking such positions, commitments, and actions, Ngô Vĩnh Long did not live under any illusions. He fully expected, and accepted, the negative consequences of his beliefs on his personal life, intellectual development, and professional career.Footnote1

In taking such strong and courageous personal and intellectual positions, Long gained a reputation that was sometimes revealing, but also one-sided and misleading. The headline for his obituary in The New York Times reported that he was a “lightning rod for opposing the Vietnam War.” His obituary in The Boston Globe stated that he was “a scholar of Vietnam attacked for his views about war.” One could easily conclude from these and other publications that Ngô Vĩnh Long was an uncompromising intellectual who created controversy.Footnote2

However, this perspective of Long is misleading because it does not address the key question: who considered him a lightning rod and an enemy? Ngô Vĩnh Long was very welcoming, unpretentious, kind, warm, and hospitable. He was very generous with his time when it came to his students, colleagues, and fellow scholars of Vietnam and Asia, including those with whom he disagreed. In relating to himself and to others, he expressed a great sense of humor, especially in his tendency to subject others to endless puns, many of which he recognized as really corny, as he laughed at himself. This more complex perspective offers a more insightful view of the vision and legacy of Long as an exemplary intellectual.

Born on April 10, 1944, Long was given the name of his birthplace, the southern province of Vĩnh Long, which means “perpetual prosperity.” Ngô Ngọc Tùng, his father, was the son of a scholar gentry family from the northern province of Bắc Ninh and an activist in the anticolonial movement against the French during the 1930s. Hồ Thị Ngọc Viễn, his mother, defied her family’s wish and eloped with Long’s father. Growing up in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Long was shaped by the brutality of French colonialism and how his parents and others identified with the Vietnamese revolutionary anti-colonial struggle. He recalled that as a young boy, he witnessed how the French killed many Vietnamese and dumped their bodies in the Mekong River. In a later interview he recalled how he would “swim with floating corpses” and this would make him very sick.Footnote3

His father urged him not to learn French, the language of the colonizing “barbarians,” and instead to learn English.Footnote4 The father and his young son traveled one hundred miles to Saigon (Sài Gòn, now Hồ Chí Minh City) where they purchased a copy of Great Expectations by Charles Dickens. For the next year, Long and his father would read Dickens every day and guess at the pronunciation. This was how Long acquired a rudimentary knowledge of English that had a profound influence on his future.

After 1954, the United States replaced the French as the dominant foreign power in Vietnam. The US Army hired Long as a translator and mapmaker when he was sixteen. His hope was to help the Americans draw accurate maps and avoid bombing the wrong targets or villages. By 1962, however, his work near the Strategic Hamlet program had consolidated Long’s opposition to US intervention in Vietnam. As he described in an interview in 1982: “In some places, people were dying of hunger in droves. I stayed in one village for two months and each month about 200 people died of hunger. People were so hungry they were eating the bulbs of plants.”Footnote5 What he saw transformed Long into a strong opponent of the Vietnam War and US intervention in Vietnam. Long resigned from his job and became an outspoken critic of both the US role and its ally, the South Vietnamese (Republic of Vietnam) government.

Long publicly spoke out and demonstrated against the war, drew the ire of the government in Saigon, and escaped arrest by traveling to the United States. He hoped to inform Americans about what was happening in Vietnam. Through the American Friends Service Committee, he spent a year as a high school exchange student in Joplin, Missouri, before enrolling in 1964 as the first student from Vietnam to attend Harvard.

Long soon became “the most prominent Vietnamese scholar-activist in the United States.”Footnote6 His speeches, writings, and actions alarmed the Saigon and Washington governments as well as economic, political, and academic power elites, and would have both inspirational and tragic consequences for his future life.

One of his first efforts after arriving at Harvard was organizing his fellow students to travel to Washington in April 1965 to take part in what was, until that time, the largest antiwar protest in the United States. For the next decade, Long was a prominent leader of a Cambridge-based Vietnamese student peace group. In addition to working with Americans, Long collaborated with other Vietnamese in the US and in 1965 was elected president of the Vietnamese Association in New England. But he concluded that organizing sympathetic Vietnamese in North America was not the most effective expenditure of his time and antiwar commitments. Therefore, he decided to focus on ways to influence the American public.

At that time, he also decided to make Asian Studies his field of study at Harvard. This is when he got to know John King Fairbank, who recognized his exceptional intelligence and was supportive of him, as well as Samuel Huntington, Henry Kissinger, and others who were major architects of US neocolonialism, militarism, and imperialism. Long later would relate that Huntington thought he was naïve in not recognizing that Vietnam and “every society, like every human being, has a breaking point.”Footnote7

Long felt that these august, eminent, powerful professors needed to be exposed as complicit with and actively involved in torture, genocide, war crimes, and the American military-industrial-academic complex. That is why his opposition to war and imperialism was not tolerated by the power elite and dimissed as “merely academic.”

In February 1968, several weeks after the Tết Offensive, Long and other Vietnamese graduate students presented “the first organized public statement against the war by Vietnamese citizens” in the US in front of 600 people at Harvard’s Sanders Theater.Footnote8 A month later, Long and fifteen other South Vietnamese students held a press conference in Washington to announce a joint statement that they had delivered to South Vietnam’s ambassador to the United States, Bùi Diễm.Footnote9 In this statement, which was entered into the Congressional Record at the request of Senator William Fulbright (D-Arkansas), the signers held the US government primarily responsible for the war. This infuriated and threatened South Vietnam government officials, who revoked the signers’ passports. Thanks to the protection of sympathetic American politicians, the students avoided deportation. For the remainder of the war, Long continued to organize numerous antiwar talks and teach-ins. For example, on March 7, 1969, he gave a stirring antiwar speech in front of eight US Senators and about 1,500 attendees at a commemoration in honor of Senator Ernest Gruening (D-Alaska) in Boston.

As Ngô Vĩnh Long noted on several occasions, the Tết Offensive of 1968 was one of the decisive events in deepening his commitment and pushing him even further. He and sixty-two other Vietnamese activists released a statement denouncing US conduct in the war and demanding an immediate end. In April 1972, fifteen patriotic, antiwar, and anti-imperialist young Vietnamese, most of whom were on US Agency for Development (USAID)-sponsored scholarships, gathered on the campus of Southern Illinois University (SIU) under the leadership of Ngô Vĩnh Long, and included David Trương, Lê Anh Tú, and others who participated at great personal risk. They exposed the nature of the policies of the US and South Vietnam governments, Vietnamization, and USAID policies of training and torture in Vietnam. They also criticized the Vietnam Center at SIU for its neocolonial and postwar policies, and described Wesley Fishel, Milton Sacks, and other key members of the center as war criminals ().Footnote10

Long and fellow student activists at Southern Illinois University, April 24, 1972.

Credit: Doug Allen.

Revealing of Long’s personality and revolutionary approach was his relationship with Nguyễn Thái Bình, a Vietnamese student who hijacked a Pan American flight from Manila to Saigon in July 1972.Footnote11 Bình and Long were close friends, and Bình regarded Long as an exemplary antiwar activist intellectual. Bình was one of the courageous Vietnamese who attended the event at Southern Illinois University, where he recited his own poetry, sang songs he had composed, and was overcome by anger and anguish about Vietnamese suffering. His visa was revoked, and he was forced to return to Saigon to face almost certain imprisonment and torture. Bình’s failed hijacking was a desperate attempt to force the United States to negotiate a peace deal with Hanoi. Despite their shared anti-imperialist, antiwar sentiments, and affectionate friendship, Long disagreed with Bình’s decision. With his greater understanding, Long knew that the desperate hijacking was doomed to failure, and he believed the antiwar movement should uphold nonviolence as a matter of both political strategy and moral principle.

Ngô Vĩnh Long had no illusions about the consequences of his activism on his career, security, and well-being. In a 1999 interview, he shared how he had become the focus of so much hatred and so many attacks and how, “for the next twenty years, from 1975 to 1995, my life was hell.”Footnote12

After the US withdrew from Vietnam and the war ended in April 1975, Long infuriated some Vietnamese-American refugees and the US power elite by refusing to denounce the Hanoi government or what was happening in unified Vietnam. He repeatedly said that he sympathized with many things in Vietnam, was critical of many other things, and analyzed developments as an independent scholar.

Of the many threats and attacks he faced, the most publicized was a gathering in April 1981, after he had spoken at Harvard. Many outraged Vietnamese Americans denounced him, and one of them hurled a Molotov cocktail at Long, trying to kill him. In a Boston Globe interview after this attempt on his life, he said, “They accuse me of being a communist agent. I am not.”

Long and other Vietnam scholars founded the Vietnam Studies Group (VSG) in 1970, which remains the most prominent academic society for researchers of Vietnam in the US.Footnote13 Some of the VSG scholars had been part of the antiwar movement in the 1960s and had strong anti-imperialist commitments. Others had played it safe, remained silent, and fit in with the establishment Vietnam Studies field that Long challenged. An even larger number were younger and were part of postwar mainstream Vietnam research and studies in the United States.

From Long’s perspective, the VSG increasingly lacked a revolutionary orientation and was often quite conservative. Nevertheless, reflective of Long’s approach and vision, he consistently attempted to reach out to other scholars of Vietnam, engage them in scholarly dialogue through writings, talks, and meetings, and hoped that he could move the VSG and the field in more progressive directions.

Among Long’s most consequential contributions to the antiwar movement was his creation of the Vietnam Resource Center (VRC) in early 1969, whose aims were to link American and international activists with those in Vietnam and to provide a greater understanding of the Vietnam War and what was happening in Vietnam. The VRC briefed American journalists before they traveled to Vietnam and introduced them to people in Saigon who could provide firsthand experiences and information. It was a major source of information and analysis for American and international antiwar activists.

One of the VRC’s most significant accomplishments was the publication of the influential newsletter Thời Báo Gà (TBG, “Rooster Times”), which first appeared in March 1969 and was edited and written mainly by Long. The first thirteen issues were published primarily in Vietnamese; from the fourteenth issue onward, it was published entirely in English. This helped serve Long’s goal of disseminating news of wartime developments in Vietnam to the American public. In its sixteenth and eighteeth issues, for example, TBG vividly encapsulated the ongoing evolution of urban opposition in South Vietnam to the war and reprinted statements by activist students, Buddhists, and Catholics.Footnote14

The information and incisive analyses provided by TBG were frequently consulted and referenced by American politicians, antiwar activists, and progressive think tank analysts who used the materials to argue for an end to US engagement in Indochina. Among them were Senators William Fulbright and Edward Kennedy, Noam Chomsky, Howard Zinn, Don Luce, and people associated with the Indochina Resource Center and the American Friends Service Committee ().

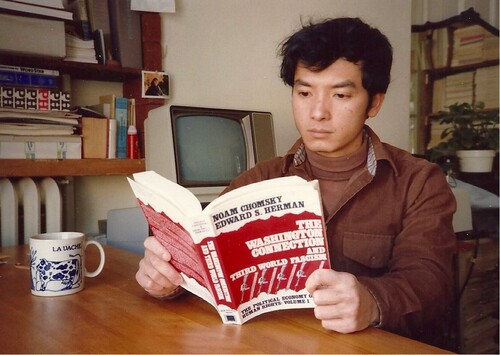

Ngô Vĩnh Long reading Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman’s The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism. 1979. The book was gifted to Long by Herman when he visited Long at his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Credit: The family of Ngô Vĩnh Long.

Professor Long also was the first activist to provide evidence to Americans of birth deformities among victims of Agent Orange. By providing prominent scientists, such as Harvard biologist Matthew Meselsson, photos and articles from South Vietnamese newspapers, Long helped rally the US scientific community against the war and, more specifically, against the indiscriminate spraying of herbicides by the US military in Indochina. He later became a board member of the Vietnam Agent Orange Relief & Responsibility Campaign, a project of Veterans for Peace.

One of Ngô Vĩnh Long’s major impacts was his role in the founding of the Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars (CCAS) in 1968 and the following year of the Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars (BCAS, later renamed Critical Asian Studies). One cannot overemphasize Long’s contributions to CCAS and BCAS as an invaluable resource for new information and analysis, his key participation at teach-ins and conferences, his speaking out and activism, and his writings and many publications.Footnote15

As a scholar activist and an activist scholar, Long perceived the modern state as a military-industrial-intellectual complex, in which the intellectual class plays a critical role in rationalizing and normalizing the oppressive manifestations of state and elite coercive powers. Long’s approach was similar to that of the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, especially Gramsci’s “war of position” – the slow intellectual and cultural struggle of anti-capitalist revolutionary forces, in which organic revolutionary intellectuals challenge the hegemony of the capitalist ruling class. This simultaneously places the progressive intellectual in the best position to expose the nature of state and ruling class coercion and to be essential for mobilizing resistance to that coercion.

Many progressive antiwar and anti-imperialist Asian and other scholars identified with the National Statement of Purpose of the Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars adopted at the national meeting of the CCAS held in March 1969 in Boston. The three-paragraph Statement of Purpose begins: “We first came together in opposition to the brutal aggression of the United States in Vietnam and to the complicity of silence of our profession with regard to that policy.” The Statement ends by affirming that CCAS is intended to provide alternatives to establishment scholarship on Asia, serve as a catalyst and communications network for Asian and Western scholars, and to be “a community for the development of anti-imperialist research.”Footnote16

During his student days, Ngô Vĩnh Long authored two books. Most remarkable is Before the Revolution: The Vietnamese Peasants under the French, written while he was a graduate student.Footnote17 This outstanding book provides readers with an understanding of the then-little known economic, political, cultural, and ideological dimensions of French colonialism in Vietnam. It is also an invaluable resource for understanding the First Indochina War (1946-1954) and the emergence of US neocolonialism and imperialism.

The next year, he authored Vietnamese Women in Society and Revolution: The French Colonial Period.Footnote18 This book presents a survey and analysis of a little-known and under-studied topic: how bourgeois, peasant, and proletarian Vietnamese women related to French colonialism and to the anti-colonial revolutionary movements.

Long’s third book, published in 1991, is the co-edited Coming to Terms: Indochina, the United States, and the War.Footnote19 As Long commented, this book offers the most comprehensive articles on the subject matter in any foreign language, and it was widely praised in journals.Footnote20

After the war ended in 1975, Long decided to change his research priorities in ways that he felt would be most effective in reaching a larger audience. From the war’s end to the last month of his life, Long wrote hundreds of scholarly and popular articles with incisive analysis, and gave countless media interviews on developments in Vietnam, US-Vietnam relations, and Sino-Vietnamese relations.

In 1985, Ngô Vĩnh Long was hired as a faculty member in the Department of History at the University of Maine. For the previous decade, he had worked as a carpenter, became a very talented photographer, and wrote eloquent poetry, such as the following untitled poem:

Ngô Vĩnh Long and former Socialist Republic of Vietnam Prime Minister Võ Văn Kiệt in Hanoi in March 2008, three months before Kiệt passed away.

Credit: The family of Ngô Vĩnh Long.

Long is survived by his first wife, lawyer Nguyễn Hội-Chân, and their son Ngô Vĩnh-Hội and daughter Ngô Thái-Ân. From his second marriage, he is survived by his wife, clinical social worker and mental health counselor Mai Hương Nguyễn, and their sons Ngô Vĩnh-Thiện and Ngô Vĩnh-Nhân.

Ngô Vĩnh Long’s legacy

Ngô Vĩnh Long hoped that his scholarly work would help others understand the costs of making a revolution, the complicated nature of postwar problems, and how postwar struggles determine whether a revolution is won or lost in the long term.Footnote21 In that regard, as a revolutionary progressive intellectual, Long was always aware of how Henry Kissinger and other power elites regarded the “bad lesson” of the Vietnamese Revolution. They believed that a revolutionary Vietnam was akin to a cancer that must be contained and then destroyed before it could spread. This, they assumed, could be accomplished through violent means, economic blockades, denial of desperately needed aid, and other measures. Ngô Vĩnh Long confronted and rejected their views throughout his life.

As Long analyzed and wrote, many divisions that had developed during the Vietnam War and in the postwar period remain in today’s Vietnam. On the one hand, in the late 1960s and 1970s, the US-supported, anti-communist South Vietnamese regime under Nguyễn Văn Thiệu attempted to destroy all progressive and revolutionary alternatives in the south. On the other hand, after the Hanoi-dominated Socialist Republic of Vietnam was established in 1976, the state neutralized, marginalized, eliminated, and sometimes absorbed revolutionary groups and individuals from the south. This is how an alarmed and distressed Ngô Vĩnh Long viewed much of Hanoi’s nonrevolutionary “success” in formulating and enacting policies defining what happened in Vietnam after the war.Footnote22

Long also described and interpreted the complexities of Vietnam’s approaches to China and to the United States. With regard to the United States, Long was concerned about continuing threats of neocolonialism, the Vietnamese government’s willingness to offer much cheaper, more docile, and profitable labor and resources to multinational corporations than China, and his recognition that some elites in Vietnam extolled Donald Trump. At the same time, Long was especially disturbed by the resurgence of right-wing extremism in the US and around the world.

With regard to China, after the American War in Vietnam ended, Long was concerned about China’s support for Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge, the Chinese war on Vietnam, and the support of some Vietnamese for a Chinese economic development model. Over the past three decades, he became increasingly alarmed by the significant and ongoing threat posed by China’s economic, political, and military policies and actions. In Vietnam, he was considered one of the foremost experts on Vietnam’s relations with China and the United States, especially concerning ongoing territorial disputes in the South China Sea.Footnote23

In coming to terms with Long’s legacy, we need to be selective in appropriating what is of lasting value and rejecting the temptation to identify and categorize Long in narrow rigid terms. He was a progressive intellectual who took a complex, multidimensional, and open-ended analytical approach, sought principled compromises, and adjusted to historical and contextual changes, while attempting to maintain his revolutionary vision and hopes for mutual collective understanding, reconciliation, peace, and justice. He sometimes described this as a “pan-humanism” perspective that could challenge, transform, and overcome divisions in Vietnam, in the Vietnamese diaspora, and in US-Vietnam relations.

Examining Vietnam and Indochina during French colonialism and in the revolutionary struggle for freedom and independence, Ngô Vĩnh Long admired Hồ Chí Minh and many other Vietnamese revolutionaries. After North Vietnam’s military victory in 1975, Long became very critical of Vietnam’s rigid policies and nonrevolutionary developments. Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to conclude that he rejected everything about the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. After the war, he continued to identify with and support progressive forces within Vietnam and in the diaspora. Long appreciated the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (NLF) and its subsequent Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG).Footnote24 He admired the NLF-PRG revolutionary leaders, including Nguyễn Thị Bình (Madame Bình), who became a major figure in reunited Vietnam and was twice elected vice-president of the SRV.Footnote25

Finally in avoiding narrow identifications and categorizations, Long also admired the courage, effectiveness, and revolutionary potential of the Third Force in South Vietnam, especially between 1968 and 1975. This included students, intellectuals, Buddhists, Catholics, and others in the south who resisted the Saigon regime without espousing communist doctrine.Footnote26 Also referred to as the “Third Segment,” this informal coalition of progressive urban groups was not aligned with either the South Vietnamese government or the NLF-PRG. In his writing, Long discussed the history and significance of the Third Force, and even identified with it.Footnote27

A key debate in Vietnam Studies, China Studies, and in related fields has been about activism versus professionalism. For a relatively brief period during the height of the Vietnam/Indochina War, the balance shifted for many scholars toward antiwar activism. With the end of the war in 1975, the balance shifted back toward professionalism, and many scholars minimized or rejected activism as part of their academic and professional careers. This was never the vision or practice of Long. He remained an exemplary model of the activist intellectual, not only during periods when many others praised and joined him, but also during the rough times when he struggled against the professional current and was punished for maintaining his position.

Living consistent with his beliefs, Ngô Vĩnh Long worked for a democratic and socialist Vietnam. He worked for a Vietnam that would be diverse, inclusivist, and pan-humanist. Such a Vietnam would be radically egalitarian and opposed to top-down hierarchical economic and political relations of domination. It would be nonviolent, organically harmonious, and peaceful, promote freedom and social justice, and work to transform and overcome divisive conflicts. Long envisioned and worked for a future Vietnam that would be committed to meeting the needs of all, especially the impoverished, peasants, wage workers, and others who are most oppressed and have the least freedom.

In his life, Ngô Vĩnh Long demonstrated the essential role and indispensable contributions of progressive intellectuals. While his greatest accomplishment was to help end one of the bloodiest wars in human history, his ultimate goal was always to pave the way for new and hopeful beginnings.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

An Thùy Nguyễn

An Thuy Nguyen (Nguyễn Thùy An) is a PhD Candidate in History at The University of Maine. Her specializations are the history of US foreign relations, diplomatic history, Vietnamese history, twentieth century US history, women’s history, and gender studies. Her dissertation probes the significance and implications of the Nixon Doctrine in Asia from the perspectives of South Vietnamese antiwar activists. An has authored a journal article, a book chapter, two book reviews, and other opinion pieces. An also serves as translator and editor of a book project on the first Indochina War (funded by the Vietnam Studies Group and the Henry Luce Foundation) and as translator for a documentary film on the Vietnam War. She is a recipient of the Swarthmore College Peace Collection’s Moore Research Fellowship, the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations’ Marilyn Blatt Young Dissertation Fellowship and Samuel Flagg Bermis Research Grant, and University of Maine fellowships and awards. She can be contacted at an.[email protected].

Douglas Allen

Douglas Allen is Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at the University of Maine. He has authored and edited eighteen books and more than 150 book chapters and journal articles, including Gandhi after 9/11: Creative Nonviolence and Sustainability (Oxford University Press, 2019). A peace and justice scholar-activist, Allen was active in the civil rights movement, the Vietnam antiwar movement, the anti-apartheid movement, and many other struggles resisting violence, war, class exploitation, imperialism, racial and gender oppression, and environmental destruction. In 2022, he edited two volumes, The Philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi and War and Peace in Religions. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Notes

1 See, for example, an interview with Ngô Vĩnh Long that appears in Allen Citation1989.

2 Mydans Citation2022; Marquard Citation2022.

3 Appy Citation2004.

4 By the time he graduated from Harvard, Long was proficient in French, Chinese, and Russian, in addition to English and Vietnamese.

5 Dumanoski Citation1982.

6 As described by Doug Allen, a view shared by many other antiwar scholar-activists at the time. Allen Citation1989, 120.

7 Allen Citation1989, 120.

8 Yee Citation1968.

9 The New York Times, March 3, Citation1968.

10 There are many CCAS and other publications covering this event in detail. See, for example, Allen Citation1976; Ngô Vĩnh Long Citation1972; and Emerson Citation1975, especially 300-308 & 399-401.

11 On a Pan American World Airways flight from Manila to Saigon on July 2, 1972, Nguyễn Thái Bình (1948-1972), who had studied in the United States on a USAID scholarship, attempted to divert the plane to Hanoi. Holding lemons wrapped in tin foil, Bình threatened to detonate his “bombs” if his request was not met. Insisting on the need to refuel the plane, pilot Gene Vaughn landed the aircraft at Saigon’s Tân Sơn Nhứt Airport. Once the plane touched down, the pilot subdued Bình and shouted at an armed passenger to “kill the son of a bitch.” A total of five bullets pierced Bình’s back. Vaughn proudly recalled throwing the student’s body out of the aircraft “like a football” to be picked up later by stunned guards. Just over a month earlier, Bình had given a fiery antiwar speech at his graduation commencement at the University of Washington. Bình was praised by newspapers in North Vietnam as a hero and a martyr after his untimely death. See Montgomery Citation1972.

12 Allen Citation1989, 121.

13 The VSG is a Subcommittee of the Southeast Asia Council of the Association for Asian Studies and provides resources for scholarly research, study, and teaching about Vietnam. Long served as its president in 1981.

14 Ngô Vĩnh Long Citation1971a; Ngô Vĩnh Long Citation1971b.

15 For example, Long provided information and analysis for most of the articles in Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars Citation1970.

16 The Statement of Purpose was first published in BCAS Citation1969. Long worked closely with CCAS antiwar and anti-imperialist scholars. These included Jim Peck, Mark Selden, Marilyn Young, Noam Chomsky, John Dower, Leigh and Richard Kagan, Jon Livingston, Nina Adams, Tom Engelhardt, Jim Morrell, Perry Link, and many others.

17 Ngô Vĩnh Long Citation1973.

18 Ngô Vĩnh Long Citation1974.

19 Allen and Ngô Vĩnh Long Citation1991.

20 This book grew out of a special issue published by the Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars in 1989. See BCAS Citation1989.

21 Allen Citation1989, 121.

22 For his analysis of polarization and divisions within Vietnam and of how North Vietnamese leaders undermined and often destroyed non-communist revolutionary individuals and groups, see Long Citation2013b. This insightful analysis shows how Long identified with non-communist progressive individuals and movements. This also helps us to understand why Long experienced problems with Vietnamese officials after the war.

23 Long was frequently invited to teach special courses to young Vietnamese diplomats during their short-term training programs at Harvard. He also gave many interviews, lectures, and speeches in Vietnamese on the South China Sea disputes over the years. For an example of an English article by Long on this topic, see Long Citation2013a.

24 He was never associated with, nor represented in any capacity, the NLF-PRG, as claimed by some.

25 Along with former Prime Minister Võ Văn Kiệt (1922-2008), who Long greatly admired, Bình was one of the most progressive politicians in the SRV and often advocated for government reforms and opposed controversial measures, such as a bauxite mining project approved by then-Prime Minister Nguyễn Tấn Dũng in 2008. For more on Nguyễn Thị Bình, see Nguyen Citation2023b.

26 For more on the Third Force in South Vietnam, see Nguyen Citation2019 and Citation2023a. See also Quinn-Judge Citation2017.

27 Cf. Long Citation2013b. Long argued that it is important to recognize the continuing presence and the lessons of the Third Force for the future of Vietnam. See Long Citation2011.

References

- Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars. 1969. “Purpose and Policy Statements.” 2 (1): 8-9.

- Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars. 1989. “Twentieth Anniversary Issue in Indochina and the War.” https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rcra19/21/2-4?nav=tocList.

- Allen, Douglas. 1976. “Universities and the Vietnam War: A Case Study of a Successful Struggle.” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars (BCAS) 8 (4): 2–16.

- Allen, Douglas. 1989. “Antiwar Asian scholars and the Vietnam/Indochina War.” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars (BCAS) 21 (2-4): 112–134.

- Allen, Douglas and Ngô Vĩnh Long (editors). 1991. Coming to Terms: Indochina, the United States, and the War. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Appy, Christian. 2004. Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides. New York: Viking.

- Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars. 1970. The Indochina Story: A Fully Documented Account. New York: Bantam Books.

- Dumanoski, Dianne. 1982. “Trials of Ngo Vinh Long: threats, break-ins, bombs.” The Boston Globe, July 6.

- Emerson, Gloria. 1975. Winners and Losers: Battles, Retreats, Gains, Losses and Ruins from a Long War. New York: Random House. 300–308, 399-401.

- Marquard, Bryan. 2022. “Ngo Vinh Long, scholar of Vietnam attacked for his views about war, dies at 78.” The Boston Globe, November 13.

- Montgomery, Paul. 1972. “Hijacker killed in Saigon; Tried to divert jet to Hanoi.” The New York Times, July 3.

- Mydans, Seth. 2022. “Ngo Vinh Long, lightning rod for opposing the Vietnam War, dies at 78.” The New York Times, October 23.

- New York Times. 1968. “16 South Vietnamese in U.S. and Canada support a halt,” March 3, 1968.

- Nguyen, An Thuy. 2019. “The Vietnam women’s movement for the right to live: A non-communist opposition movement to the American War in Vietnam.” Critical Asian Studies 51 (1): 75–102.

- Nguyen, An Thuy. 2023a. “Third Force: South Vietnamese Urban Opposition to the Nixon Doctrine in Asia (1969-1973).” Doctoral Dissertation, The University of Maine.

- Nguyen, An Thuy. 2023b. “Nguyễn Thị Bình (b.1927): The flower and fire of the revolution,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Communist Women Activists around the World, edited by Francisca de Haan. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Quinn-Judge, Sophie. 2017. The Third Force in the Vietnam Wars: The Elusive Search for Peace 1954-1975. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Ngô Vĩnh Long. 1971a. “Grooming the ‘Third Force.” Thời Báo Gà (16), May.

- Ngô Vĩnh Long. 1971b. “The Urban Opposition.” Thời Báo Gà (18), November.

- Ngô Vĩnh Long. 1972. “A Vietnamese Invasion.” Thời Báo Gà (24), May.

- Ngô Vĩnh Long. 1973. Before the Revolution: The Vietnamese Peasants und the French. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Ngô Vĩnh Long. 1974. Vietnamese Women in Society and Revolution: The French Colonial Period. Cambridge, MA: Vietnam Resource Center.

- Ngô Vĩnh Long. 2011. “Vài Nhận Xét Về “Thành Phần Thứ Ba” và “Hòa Hợp, Hòa Giải Dân Tộc [A few comments on the “Third Segment” and “National Reconciliation and Concord].” Thời đại Mới [New Era].

- Ngô Vĩnh Long. 2013a. “Unhappy neighbors: Why Beijing’s muscle-flexing in the South China Sea alarms Asia.” Cairo Review (August): 70–84.

- Ngô Vĩnh Long. 2013b. “Military victory and the difficult tasks of reconciliation in Vietnam: A cautionary tale.” Peace & Change 28 (4): 474–487.

- Yee, Min S. 1968. “Harvard Viet students denounce US, Saigon.” The Boston Globe, February 15.