ABSTRACT

This article examines a set of sexuality education textbooks used in a selection of primary schools in Beijing. These textbooks, under the overall name of 珍爱生命 (Cherish Lives), embody a comprehensive sexuality education approach with content designed on the basis of the UNESCO International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education. Using feminist critical discourse analysis, we explore these books from three angles: the challenge of engaging with children as sexual subjects, given adult hegemony around sex; confusion about efforts to break the presentation of gender as a binary; and the contradiction between reproducing the myth of universal heterosexuality and attempting to present an education sensitive to LGBT issues. We show that while these textbooks demonstrate progress in sexuality education, they also manifest compromise. Despite this compromise, the books have recently been withdrawn and it is unclear whether their publication heralds a new, high quality approach to primary school sexuality education or not.

Introduction

The intersection of childhood and sex in any form has been a contentious topic in most countries for a long time (Hall et al. Citation2016). This is the case in China where, with the development of the Internet, children can receive more sexual information than ever before (Leung et al. Citation2019). In addition, Chinese media have begun to focus on illegal sexual behaviours against children, and a growing number of people pay attention to social issues about gender equality and diversity (Wu and Dong Citation2019). This has made some Chinese parents and social organisations aware of the importance, even perceived necessity, of sexuality education, but such education is difficult for parents to provide in practice. For one thing, most parents lack professional knowledge and training in sexuality education; for another, they are almost invariably embarrassed when talking about sex with their children because of widespread cultural hesitancy surrounding the discussion of sexual matters. For this reason, some parents and the Ministry of Education department responsible for sexuality education have for some time hoped that sexuality education would be taught as a formal course in school (Zhang, Li, and Shah Citation2007).

In China, many have worked hard to improve the quality of sexuality education (Tang Citation2014). Drawing on good practice elsewhere in the world, sexual and reproductive health education, services and research in China have begun over the last couple of decades to develop on a large scale (Kuete et al. Citation2021). At the present time, the sexuality education methods adopted in China focus mainly on school, family and community sexuality education, and sexuality education among peers. Some experts also recommend the dissemination of scientific sexual knowledge to young people through the media, including the new media. Indeed, data from the Chinese General Social Surveys indicate that the Internet is one of the driving forces behind the beginnings of a sexual revolution in China, with greater Internet usage being associated with more sexually permissive attitudes, including attitudes towards premarital sex, extramarital sex and same-sex behaviour (Liu et al. Citation2020). However, limited use is made of the Internet for teaching sex education in schools (but see UNESCO Citation2020) and, at present, adolescent sex education books issued in China are of varying quality, and school-based sex education materials are rare. Furthermore, little research has been undertaken on school sexuality education books (Tang Citation2014; Liang and Bowcher Citation2019), and this is the knowledge gap we seek to address.

Accordingly, this article focuses on 珍爱生命 (Cherish Lives) – a set of sexual health textbooks for primary school pupils (Liu Citation2010, Citation2011a, Citation2011b, Citation2013, Citation2014a, Citation2014b, Citation2014c, Citation2014d, Citation2014e, Citation2015, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). These textbooks constitute an important programme and one that proved to be influential. They were produced under the aegis of Beijing Normal University, a national level university connected to the Ministry of Education. The programme was one of the few sex education initiatives to be implemented in primary schools, ran for a number of years and was evaluated (Liu and Su Citation2014). However, as we will see, these textbooks proved to be controversial (Chen Citation2017). In this paper, we use feminist critical discourse analysis to examine the discourse of these books from three angles: the challenge of children as sexual subjects, given adult hegemony around sex; confusion about attempts to break the presentation of gender as a binary; the contradiction between reproducing the myth of universal heterosexuality and attempting to present an education sensitive to LGBT issues. Specifically, we pose the research question: how do the Cherish Lives textbooks present issues of sexuality, gender and relationships?

Most cultures have a degree of social sensitivity on the topic of sex, and talking to children about sexual matters is often controversial. In China, in part due to the influence of Confucian culture, talking about sex openly is generally avoided although the reality is that Confucian teaching and philosophy is deployed and interpreted in different ways by government, profit-making businesses and other entities, with the interpretations usually influenced by context and who stands to gain or lose.

Sex education books in China

Sex education books for children in China typically use metaphors and other indirect ways to refer to the sexual organs and sexual behaviour. It is widely held that children should be kept away from sexual knowledge, as such knowledge would sully their purity and induce them to engage in sexual intercourse.

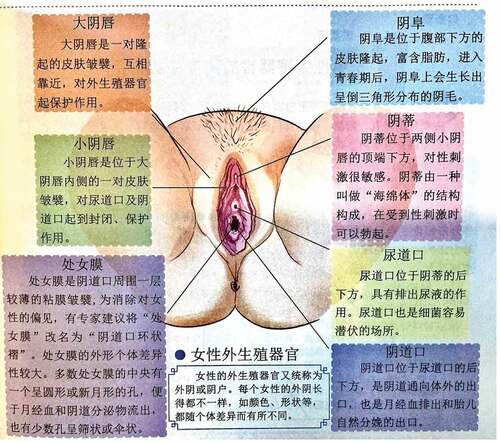

Most Chinese books about sexuality, gender and relationships involve the transmission of a large amount of information on growth and development, reproductive health, health care, sexually transmitted infection and HIV prevention, with material on a range of associated topics including menstruation, nocturnal emissions and breast development (Tang Citation2014). Providing rich and sufficient physiological knowledge can help young people understand physical changes and reduce sexual confusion caused by ignorance. However, most of the books contain no illustrations of the sex organs, although some contain simple line drawings of these (Greenwood Citation2010). Providing only text without associated and well produced illustrations is not conducive to the full understanding of the body structure of oneself and others.

Information about adolescent sexual psychology in these books is entirely concerned with communication within heterosexual relationships. When same-sex relations and practices are addressed, they are considered to be pathological, which may lead to negative self-recognition, or even more serious results, for some young people (Tang, Wang, and Tong et al. Citation2013). There are several books that teach daughters how to ‘marry a good husband’, and which therefore manifest gender discrimination (Liao Citation2013). In terms of attitudes towards adolescent sexual psychology, there are two main approaches to love relationships. One approach tries to prevent ‘puppy love’, portraying its damaging and irreversible consequences, especially with respect to academic performance and the consequences of early sexual intercourse. The other approach talks about love relationships from a young person’s perspective and gives advice to young people to help develop the ability to communicate, to protect themselves and be more self-aware in intimate relationships.

Most of the material on sexual harassment focuses on women who are sexually harassed; it is rare to state that men too can also be sexually harassed (Tang Citation2014). In addition, family relationship management is discussed. Poulain (Citation2013) has argued that an unhealthy marriage can create trauma for any offspring and trigger rebellion and disobedience among teenagers. Some books discuss topics such as sexual ethics, and there are also a number of adolescent sex education books that mention issues such as child sexual abuse, sexual education for children with intellectual disabilities, and sexual organ damage by, for example, using objects such as pencils as aids to masturbation.

Overall, sex education in China is strongly medicalised, stressing reproductive health and physiological knowledge (Peng Citation2012). Peng’s (Citation2012) analysis of books found that only a few of them engaged with ‘gender education’ and related issues, perhaps the result of the current tendency to equate gender with biological sex.

Background information about Cherish Lives

Cherish Lives is a series of sex education textbooks specially prepared for primary school students (aged 7 to 11 years old). It provides school-based curriculum materials from the first grade to the sixth grade of primary school, with each grade being divided into two semesters, and six lessons being provided per semester (Liu and Su Citation2014).

The textbooks cover a wide range of aspects of child sexual development, including families and friends, life and skills, gender and rights, physical growth, sexual and health behaviours, and sexual and reproductive health (). These topics are based on the content requirements listed in the ‘Guidelines for Health Education in Primary and Secondary Schools’ (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China Citation2008) and the six key concepts of the ‘International Technical Guidance on Sexual Education’ issued by UNESCO (Citation2020).

Table 1. Contents of the material in Cherish Lives, organised by school grade

According to the development team (Liu and Su Citation2014), this set of books began with plans for sex education for migrant children in Beijing. So-called migrant children are those who accompany their parents from their own natal areas (mostly rural) to new cities. In China, with continued economic and social development, more and more young labourers have migrated from underdeveloped areas to more developed cities. China’s migrant population has therefore seen rapid growth in the past few decades. There were an estimated 36 million migrant children in China in 2010 (the most recent year for which statistics appear to have been published), with about 30% of children in Beijing being migrant (All-China Women’s Federation Citation2013).

The housing conditions of migrants can be very disadvantageous for children. Of the 6,344 children interviewed in Zou, Qu, and Zhang (Citation2004), 79% shared a bedroom with their parents and 45% lived in accommodation where different families shared a bathroom. Cases of reported child abuse and sexual assault on migrant children have increased recently, possibly because of greater awareness and reporting but also because such children lack parental protection and knowledge, and awareness about anti-sexual assault (Guangdong Women’s Federation Citation2012). Most of the victims of sexual abuse are migrant girls who come to the city with their parents (Guangdong Women’s Federation Citation2012).

The migrant school system is a parallel system, less regulated than mainstream state schools, migrants in Beijing essentially being excluded from mainstream schools. The team producing Cherish Lives located primary schools designed especially for migrant children in Beijing and worked with ten of these schools to trial experimental units of sex education, beginning in 2007.

This set of books began to be available on the public book market in 2011. In 2013, the first batch of migrant children who had received six years of sex education using Cherish Lives and benefitted from a trained teacher graduated from primary school. Analysis undertaken by the books’ production team indicated that students made considerable progress in their knowledge about sex and related attitudes (Liu and Su Citation2014).

In 2017, with the publication of all 12 books in the series, discussion about these books became a hot topic in the local social media. A parent in Hangzhou complained about the book to Hangzhou Bureau of Education because of the inclusion of descriptions of reproductive organs, celibacy and same-sex relationships. As a result, the books were withdrawn at that school (Chen Citation2017). It was this that prompted the research reported in this article. In March of 2019, the books were banned from public sale and disappeared from the major book markets and e-commerce platforms.

Methods

The goal of this study was to explore the knowledge, ideology and power relations surrounding sex and gender in Cherish Lives, so critical discourse analysis from a gender perspective was appropriate. Feminist critical discourse analysis (FCDA) was selected because it can aid in understanding the intersection between sex, gender, power, hegemony and discourse. As Lazar (Citation2007, 141) has put it, FCDA ‘aims to advance a rich and nuanced understanding of the complex workings of power and ideology in discourse in sustaining (hierarchically) gendered social arrangements’. The ideologies discussed by critical discourse analysis often seem ‘natural’ and unchallenged. As a result, they play an important role in maintaining the relationship between power and practice.

FCDA regards discourse as an element of social practice, which enjoys a dialectical relationship with society, such that discourse is not only a form of social practice but is also influenced by it (Lazar Citation2005). Gender is understood as a variable with liquidity and multiplicity, not a fixed state, but rather as a dynamic process constituted through a series of practices (Connell Citation2005). Gender is seen as socially constructed, interacting with other aspects of identity – such as race, age and class. Both critical discourse analysis and feminist approaches to analysis are increasingly being used to examine Chinese source material (see, for example, Peng Citation2021).

Cherish Lives uses a variety of learning approaches to facilitate children’s engagement and learning; including text, pictures, character dialogues, after-school exercises and some supplementary materials. Together, these form a multimodal whole and accordingly, insights from multimodal analysis (Jewitt Citation2016) and critical art history (Hatt and Klonk Citation2006) were employed with a focus on semiotics, feminism and general critical appraisal. Using these analytical methods, each of the books in the Cherish Lives series was examined from cover to cover, read and re-read; extensive notes were made, and interpretations were discussed between the two authors until agreement was reached. Attention was paid both to the written text and to the illustrations.

Findings and discussion

Sexual desire and the behaviour of children: breaking the adult hegemony over sex

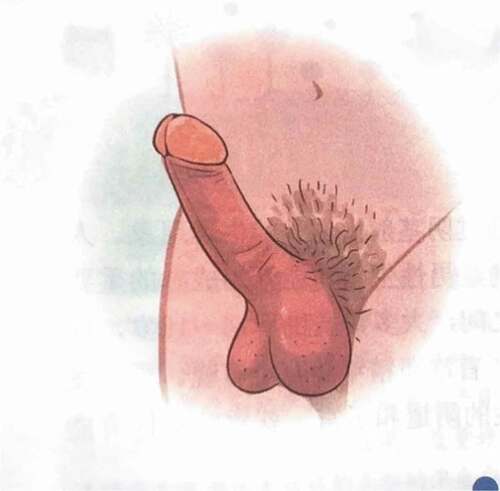

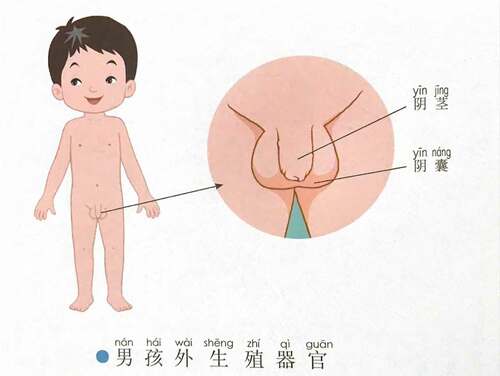

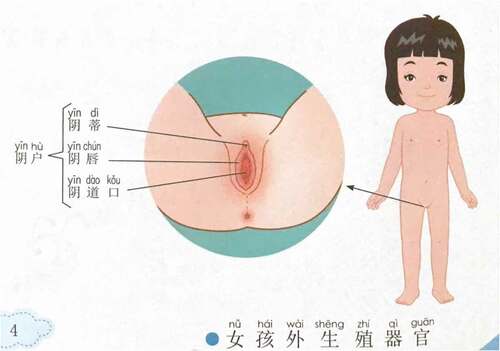

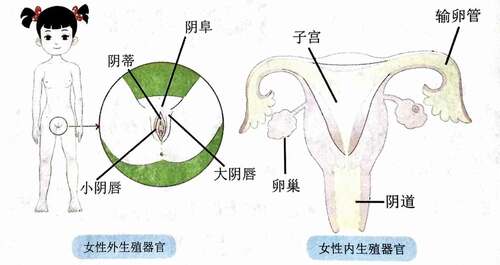

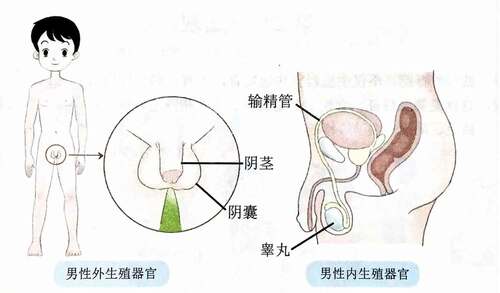

In Cherish Lives, direct (medical) terms are used to name the sexual organs and other body parts from grade 1 to grade 6 ( and ). We can also see similar direct language used in the sections of the books that address the issue of child sexual abuse prevention ( and ).

Figure 1. Illustration from Grade 1 of Cherish Lives, Volume 2, page 4. 男性外生殖器 = male external genitalia; 阴茎 = penis; 阴囊 = scrotum.

Figure 2. Illustration from Grade 1 of Cherish Lives, Volume 2, page 4. 女性外生殖器 = female external genitalia; 阴户 = vulva; 阴蒂 = clitoris; 阴唇 = labia; 阴道口 = vagina.

Figure 3. Illustration from Grade 2 of Cherish Lives, Volume 2, page 29. The girl is saying ‘Mum and dad, our neighbour, uncle Wang, just wanted to touch my buttocks; I said “no”’.

Figure 4. Illustration from Grade 2 of Cherish Lives, Volume 2, page 27. The woman is saying ‘Xiaojun, you have grown taller again. Take off your trousers and let aunt see if your penis has grown’.

Kenny et al. (Citation2008) maintain that children who have learned the medical names of the parts of their body, especially their sexual organs, are better placed to acquire self-protection skills and identify potential abuse. Using professional terms to describe the sexual organs can help to remove the social taboo surrounding discussion of sexual matters. Using direct rather than euphemistic or metaphorical sexual language in books and other texts, in whatever language they are written, can initially seem strange and embarrassing to readers, however, which is itself an indication of the powerful and largely unvoiced regulation that exists within discourse around sex.

The illustrations of sexual organs and nudity in Cherish Lives plays a similar role to the use of direct written language. Illustrations of genitalia and the naked body appear in all the grades, except grade 4. The realism of these illustrations changes, however. As students enter puberty in the fifth and sixth grade, the illustrations of sexual organs become more realistic (compare , and ).

Figure 5. Illustrations from Grade 3 of Cherish Lives showing the female reproductive system (Volume 2, page 6).

Figure 6. Illustration from Grade 5 of Cherish Lives showing the female reproductive system (Volume 2, page 3).

Figure 7. Illustrations in Grade 3 of Cherish Lives showing the male reproductive system (Volume 2, page 7).

The sexual responses, sexual desires and sexual behaviours of children are also referred to and affirmed in this set of textbooks. For example, the chapter on sex in the life cycle in the grade 3 book says: ‘From birth to death, sex is part of a person’s life’ and ‘The infant will have sexual behaviours soon after birth, such as erection in a male infant and the vagina getting wet in a female infant. These are normal and innate physiological phenomena’ (grade 3, volume 2, page 25) (all translations are by the authors of this paper). Also mentioned is masturbation:

Masturbation can occur at any age in the life cycle. In the infant stage, some male infants will touch their penis and female infants may well rub the vulva. Masturbation is an important way for us to explore our bodies, and masturbation allows us to understand how to make our body feel comfortable and satisfied. Masturbation is normal sexual behaviour. (Grade 3, volume 2, page 22)

In other, more traditional sexuality education books in China, when masturbation is mentioned, reference is made only to boys. Masturbation in girls is not mentioned, because the sexual desire of women always seems to be invisible. In Cherish Lives, not only is female masturbation mentioned, it is described as normal and morally acceptable:

For masturbation, most females use a finger to gently rub and massage the clitoris. With the increase in sexual excitement, the vagina will produce a slippery secretion. When you have an orgasm, you will usually feel the muscles tense, then relax, and get sexual satisfaction. (Grade 5, volume 2, page 21)

Girl: Mom and Dad, some people say that the girl who masturbates is a bad girl, is that the case?

Mom: This is wrong, and masturbation is a normal behaviour that everyone can decide to masturbate or not masturbate. It is a personal choice.

Dad: Girls and boys are the same. It is normal to masturbate. (Grade 5, volume 2, page 28)

Gender binary discourse and the construction of ‘social gender’

After Simone De Beauvoir (Citation1953) famously wrote that ‘one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman’, the distinction between ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ became a core concept in second-wave feminist studies and the feminist movement. However, in everyday Chinese, there is no distinction between biological sex and gender, the word 性别 xing bie, being used for both. In the field of Chinese gender studies, the phrase 社会性别 she hui xing bie, with the literal meaning of ‘social gender’, is often used to translate the word ‘gender’ into Chinese. The term 社会性别 has been in use in China since the 1990s, when the scholar Wang Zheng first to argued for it on the grounds that people would confuse the concepts if性别 continued to be used to indicate gender as well as biological sex (Wang Citation1997).

In the third grade book of Cherish Lives, the chapter on gender and rights draws a distinction between biological sex and 社会性别 (social gender) – in order to reject the equating of biological sex with gender, the latter being defined as ‘the social and cultural combination of attitudes, behaviours, rights and responsibilities that are linked to a gender by society; this changes with society and time. There is a big difference between traditional gender and modern gender’ (grade 3, volume 1, page 21).

Elsewhere, ideas about social gender rarely appear in children’s sexuality education books because school sexuality education in China has been based on biological determinism. The concept of social gender can help children understand the social and cultural constructs of masculinity and femininity as represented in shifting discourses on gender. Such an understanding can help disrupt the gender-based discrimination, oppression and inequality that exists in patriarchal society. In the grade 3 book, traditional assumptions about gender differences are explicitly addressed:

China’s traditional society requires men to be strong, bold, independent and courageous, and men have a high family and social status; women are required to be weak, quiet, obedient, good at housework and caring, and have a low family and social status. The traditional presumption of ‘male superiority to female’ is a simplified division of men and women that reflects the inequality between men and women, and it is a constraint on both men and women. (Grade 3, volume 1, page 32)

The Cherish Lives books advocate a pluralistic approach to gender. They say that men and women can be equally independent and confident, and able to take good care of others. Men and women are presented as both having the responsibility to ensure that children’s development is no longer constrained by stereotypical gender differences.

Introducing the concept of social gender in primary school sexuality education textbooks can help children understand the social construction of gender and negate unequal gender treatment. Elsewhere, Connell (Citation2013) has written that the configuration of gender practice in the school can serve as a kind of gender regime. For example, boys who manifest what may be considered traits of femininity may be the subjects of school bullying. If the notion of fixed gender roles in education can be broken down at an early stage, children can actively construct their own gender and are better placed to tackle gender inequality and constraints on individual development.

However, the discourse about gender in the pictures and texts in Cherish Lives seems to be somewhat contradictory. In general, the external image of people (the type and colour of their clothing, the appearance of their hair, the presence of accessories, etc.) can indicate something about their identities (Davies and Kasama Citation2003), including how gender is performed (cf. Jackson and Gee Citation2005).

In Cherish Lives, all the boys wear trousers (long or short). Girls are almost as likely to wear trousers as they are skirts or dress (), but symbols representing femininity can be found in the details and decorations of clothes that let the reader quickly identify the gender of the character. As Jackson and Gee (Citation2005) have argued, despite the availability for girls of skirts and trousers as alternatives, girls are still marked out as different from boys – girls can be ‘boys’ but they are still girls. In Cherish Lives, the story is much the same with respect to the colour of children’s clothing; occasionally, boys wear pink clothes but mostly they wear dark colours like blue, purple or green, while girls wear bright colours like pink, orange or yellow (). Although the text talks about men wearing pink clothes, the reality is that the expected relationship between the body and its biological sex operates as a kind of gender binary, with this stereotype becoming a cultural ideology, which even the advocacy of gender pluralism in the text cannot eliminate.

Figure 9. Illustration from the Grade 3 book of Cherish Lives showing the clothing of boys and girls (Volume 1, page 23).

Figure 10. The cover of Volume 2 of the Grade 1 book of Cherish Lives showing a girl wearing pink and a boy wearing blue.

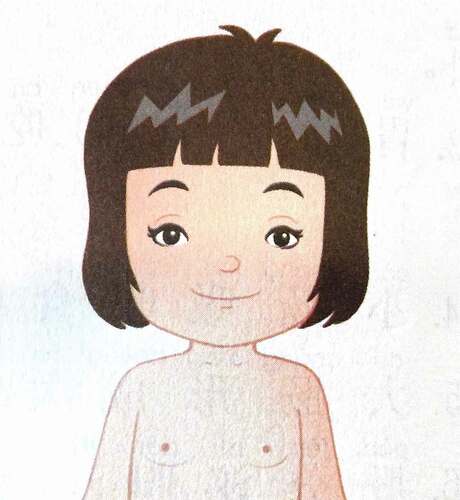

Hair, like clothes, constitutes a practice of gender, distinguishing between masculinity and femininity (Davies Citation1993). In Cherish Lives, all the illustrated boys and men have short hair, although in real life some Chinese men have long hair. Girls and women are sometimes portrayed with short hair and sometimes with long, but those with short hair manifest other symbols to indicate their femininity, including hair accessories (), long eyelashes (), protruding breasts or high heels.

Figure 11. In Cherish Lives, females are sometimes shown with short hair but femininity can be indicated in other ways. Note the flower on the girl’s head band, the frilly edge to her jumper and other differences between the clothing of the girl and the boy, such as the more angular style of the boy’s collar (cover of Volume 2, Grade 4).

According to Robinson (Citation2013), childhood can provide a queer time and space for children freely to explore gender practices; however, most children participate in normative gender performances. Unfortunately, in most cases, in China and elsewhere, schools are institutions that regulate and seek to normalise gender and sexual behaviour (Surtees and Gunn Citation2010). School textbooks – and the images they contain – have a special role to play in this respect.

Like many items of clothing the apron carries a particular cultural meaning (Jackson and Gee Citation2005). It is normally associated with women, because within the traditional patriarchal social division of household duties that pertains in China, women take primary responsibility for cooking and other kitchen activities. In Cherish Lives, however, the frequency of wearing aprons in the family is the same for men and women, and boys are sometimes shown wearing them ().

Elsewhere in Cherish Lives, efforts are made to break down traditionally gender stereotypes. In the chapters on families, it is said that both men and women have responsibility for parenting and undertaking household chores. In the grade 4 book, we read that ‘family responsibility is not gender-specific; both parents have to do housework, educate children, and take responsibility for managing the family finances’ (volume 1, page 5).

The contradiction between the ‘heterosexual myth’ and LGBT education

Until recently, there has been a widespread presumption in sexuality education that all children are heterosexual (Roien, Graugaard, and Simovska Citation2018). This kind of assumption is prevalent, even if children are considered as asexual or sexually dormant in childhood and adolescence (Robinson Citation2013). It relates to what Butler (Citation2006) identifies as the ‘heterosexual matrix’, or the idea that heterosexuality (and gender norms associated with it) defines the norms against which other forms of sexuality must be measured and judged. In China, these discourses largely constitute and regulate understandings of marriage, love and intimacy as witnessed through children’s experiences, family values and gender practices.

In Cherish Lives, all the illustrations of families show heterosexual families, including the core small family, and the traditional big family that expresses filial piety, since people live with and care for the older generation. Within this discourse, the heterosexual matrix offers an invisible gender norm defining what constitutes a ‘natural’ state. As a result, children will likely think that marriage only happens between a man and a woman.

In Cherish Lives, romantic love relationships, marriage and reproduction are also defined by the heterosexual matrix. The description of reproduction in the first grade is as follows: ‘Mom and Dad met each other; Mom and Dad fell in love; Mom and Dad got married; Mom and Dad got me; I am a good testimony to the love between Mom and Dad’ (grade 1, volume 2, page 8). In the second grade we read: ‘Mother and Dad love each other; Dad’s penis is placed in Mother’s vagina … ’ (grade 2, volume 2, page 2). The book still emphasises the link between heterosexual love, marriage and reproduction – in that order. In second grade (volume 2, page 13), a man and a woman talk about the sex of the baby they are expecting, and there is a wedding photograph of them on a nearby table, indicating that the couple are married ().

Figure 15. The illustrations in Cherish Lives emphasise the link between heterosexual love, marriage and reproduction (grade 4, volume 2, page 44).

Throughout this set of books, heterosexual behaviour, marriage and reproduction are therefore closely linked. In line with gender performativity theory (Butler Citation1990), through repetition and performance children likely repeat and transfer such textbook performances to their real lives. However, LGBT issues are also engaged with in Cherish Lives and are presented positively, in contrast to other sexuality education books that either do not mention these issues or are negative about them. Although issues of gender and sexuality diversity are mainly addressed in the fifth and sixth grade books, some material about them is included in books for younger children. The first relevant mention occurs in the context of adolescent emotional changes, discussed in grade 3: ‘Adolescent boys and girls not only want the opposite sex to pay attention to themselves; some people are more interested in the same sex, and it is normal that such people are attracted by others of the same sex’ (grade 3, volume 2, page 33).

At the same, the grade 3 book makes it clear that this interest in others of the same sex does not necessarily mean that one has a same-sex sexual orientation:

Girl: Sometimes I feel that I prefer girls, not boys, which makes me confused.

Teacher: Adolescence is the time to explore yourself in all aspects, and it is normal to be confused. We can communicate more. (Grade 4, volume 2, page 44)

Here, the teacher does not provide a direct answer to the confusion of the girl who likes girls not boys. True, the teacher does not condemn or question the girl about her feelings, but at the same time, the teacher does not explicitly tell the girl that it is acceptable for her to have feelings of someone of her own sex. What the teacher does is to provide a space for a student of this age to explore their sexuality, aligning their counselling with tolerance.

In the grade 4 book, the illustration for the introduction in the chapter on sexual fantasy shows a male figure in bed imagining himself holding hands with another man (). The heart between the two of them, as a symbol of love, makes clear the sex sexual attraction.

More explicitly, when discussing discrimination in the fifth grade, there is a formal introduction to homosexuality, with the text arguing that people should not be discriminated against on the grounds of their sexual orientation:

Homosexuality is an emotional attraction between people of the same sex and is a natural phenomenon that exists in the society. Homosexuality is not a medical condition and does not require treatment and correction. Homosexuality is not different from heterosexuality except for sexual orientation, and we should respect and treat homosexuals equally. (Grade 5, volume 1, page 17)

In Cherish Lives, pairs of women appear in texts and pictures as often as do pairs of men (e.g., ). In other sexuality education books that make references to same-sex relationships, women are typically overlooked and rendered invisible. In fact, although there has been a long history in China of opposition to men’s same-sex relationships, women’s same-sex relationships have never been illegal and are rarely commented on (Tsui Citation1990). While this approach to women’s same-sex relationships enables them to avoid moral condemnation in most cases, the discussion of same-sex female desire and behaviours in Cherish Lives helps break the silence surrounding lesbians in discourse of homosexuality in China.

Figure 17. Three pictures with the caption ‘Love is a beautiful relationship’; one shows two males, one shows a male and a female, and one shows two females (Grade 5, Volume 2, page 32).

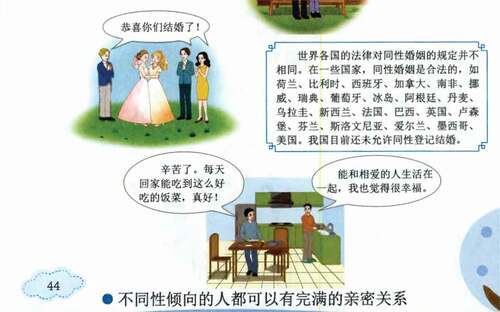

In the grade 6 book, only the illegality of same-sex marriage in China is commented upon in the main body of the text, and no clear attitude towards this is given. But in the text in the accompanying illustration (), support is expressed for same-sex marriage:

The laws of the world differ for same-sex marriage. In some countries, same-sex marriage is legal: in the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, Canada, South Africa, Norway, Sweden, Portugal, Iceland, Argentina, Denmark, Uruguay, New Zealand, France, Brazil, the United Kingdom, Luxembourg, Finland, Slovenia, Ireland, Mexico and the United States. China has not yet allowed same-sex marriage.

The picture at the top left shows two women getting married and the dialogue reads ‘Congratulations on getting married!’. The picture at the bottom shows two men together in a kitchen and the dialogue reads:

Male 1: Life is hard, but it’s good to go home every day to eat such delicious food.

Male 2: I feel very happy that I can live with people I love.

The sixth grade book also include a discussion as to the meaning of 出柜 chu gui (coming out):

Homosexuals and bisexuals usually use the phrase chu gui ‘coming out’ to indicate that they know and accept their sexual orientation and are open to others. The process consists of several stages. At the first stage, people realise that they are different from the usual heterosexuality and make sure that they are gay/lesbian or bisexual. At the second stage, they accept their own sexual orientation. At the third stage, they share their homosexual or bisexual identity with others. At every stage of the process, homosexuals and bisexuals are required to overcome different kinds of difficulty. Therefore, not every homosexual or bisexual person is willing to coming out. (Grade 6, volume 1, page 42)

This text then describes some of the processes involved when coming out as homosexual or bisexual. The journey is described as a dynamic process of exploring one’s sexual orientation. However, it can still be very difficult to come out in China. Although same-sex sexual behaviour has been legal in China since 1997, and (male) homosexuality was declassified as a mental illness in 2001, individuals in same-sex relationships still face resistance in terms both of social recognition and official policies (Zhang Citation2017).

Conclusions

In answer to the question ‘how do the Cherish Lives textbooks present issues of sexuality, gender and relationships?’, it is clear that these textbooks represent an ambitious attempt to provide a contemporary sex education programme for primary-aged children in China. Although there are aspects of the textbooks that can be criticised from a liberal perspective – for example, in terms of the fairly conventional ways in which gender is signified through the style and colours of clothes and how the heterosexual family is still presented as the norm – the content generally offers a comprehensive approach to sexuality education. There is also coherence between the text and the illustrations so that the overall result poses a challenge to the traditional Chinese patriarchal gender system. The textbooks include clear information about reproductive organs and sexual behaviour, masturbation, same-sex relationships and, through discussion of the term ‘social gender’, the role of culture in influencing gender relations. Importantly, the realistic illustrations in Cherish Lives together with the use of direct language for sexual organs, break some of the prohibitions surrounding the discussion of sexual matters.

In general, the way in which sex and gender are presented in Cherish Lives carries significant meaning for the field of school sex education in China. However, Cherish Lives proved to be controversial (Chen Citation2017). Although many educational professionals (teachers, public welfare practitioners, sex educators and others) and the children who used the materials were positive about them (Liu and Su Citation2014; Chen Citation2017), some parents found the text and illustrations too graphic. In addition, there were accusations that the books blindly imitated the West and could cause psychological harm to children. The books were suddenly withdrawn by the government in 2019, without any explanation provided as to why. It is not known whether the decisions were made at central or local level and we can only speculate as to the precise reasons why the books were withdrawn. Parental views may have been important but there may have been other factors at play too and a number of these have been suggested: perhaps the books were seen as promoting too much sexual openness; perhaps they were seen as giving too much weight to children’s rights, and thereby potentially challenging traditional authority; perhaps they were seen as reflecting what were considered to be ‘Western’ views. Although the books are no longer publicly available, they are still used in the migrant primary schools where they were developed.

Battles over the materials used in sex education have occured worldwide. In the UK, the publication of Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin (Bösche Citation1983) – a translation of a Danish book – led to comparable ‘moral panic’ in some quarters and was part of the reason for the introduction of legislation that attempted to outlaw positive teaching about homosexuality. That particular book recounts describes a few typical days in the life of Jenny, a five-year-old, Martin, her father, and Eric, Martin’s boyfriend who lives with Jenny and Martin. Karen, Jenny’s mother, lives nearby and regularly visits. In the USA, the children’s book Heather Has Two Mommies led to similar political battles (Newman Citation1989).

Bakken (Citation2018) argues that the present Xi Jinping administration in China is very nervous about LGBT matters, in part because it believes they pose a potential threat to traditional structures of authority and the family. This may be at least part of the reason why this series of sexuality education books has been banned. It is at present unclear whether the Cherish Lives ‘experiment’ will herald the development and publication of new, high quality primary school sexuality education textbooks or will be followed by a sustained period of conservative reaction and suppression.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Wenli Li and her team for permission to reproduce illustrations from Cherish Lives and to the two reviewers who provided us with very valuable feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- All-China Women’s Federation. 2013. “National Report on the Status of Left- behind Children and Migrant Children in China.” Beijing: All-China Women’s Federation of China. ( In Chinese)

- Bakken, B. 2018. “Interviewed by Joanna Chiu for ‘China’s LGBT Community Finds Trouble, Hope at End of Rainbow.’.” Agence France-Presse, June 2. AFP [Online] Accessed 28 August 2019. https://www.news24.com/World/News/chinas-lgbt-community-finds-trouble-hope-at-end-of-rainbow-20180602

- Bösche, S. 1983. Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin. London: Gay Men’s Press.

- Butler, J. 1990. “Gender Trouble, Feminist Theory, and Psychoanalytic Discourse.” In Feminism/Postmodernism, edited by L. J. Nicholson, 324–340. New York: Routledge.

- Butler, J. 2006. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Chen, M. 2017. “Elementary School Sex Education Books are Controversial Who Is ‘Scared’ by Sex Education? [Online]” Accessed 1 January 2021. http://www.xinhuanet.com//local/2017-03/15/c_1120629027.htm (In Chinese)

- Connell, R. W. 2005. Masculinities. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Connell, R. W. 2013. Gender and Power: Society, the Person and Sexual Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Davies, B. 1993. Shards of Glass: Children Reading and Writing beyond Gendered Identities. St Leonards, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin.

- Davies, B., and H. Kasama. 2003. Gender in Japanese Preschools: Frogs and Snails and Feminist Tales in Japan. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

- De Beauvoir, S. 1953. The Second Sex by Simone De Beauvoir, Translated and Edited by H. M. Parshley. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Greenwood, E. 2010. Hi, Adolescence. Beijing: Higher Education Press. (In Chinese).

- Guangdong Women’s Federation. 2012. “Research Report on the Situation of Sexual Abuse Against Girls.” Guangzhou: WFGP of China. ( In Chinese)

- Hall, K. S., J. McDermott Sales, K. A. Komro, and J. Santelli. 2016. “The State of Sex Education in the United States.” Journal of Adolescent Health 58 (6): 595–597. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.032.

- Hatt, M., and C. Klonk. 2006. Art History: A Critical Introduction to Its Methods. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Jackson, S., and S. Gee. 2005. “‘Look Janet’, ‘No You Look John’: Constructions of Gender in Early School Reader Illustrations across 50 Years.” Gender and Education 17 (2): 115–128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0954025042000301410.

- Jewitt, C., ed. 2016. The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Kenny, M. C., V. Capri, E. E. Ryan, M. K. Runyon, E. E. Ryan, and M. K. Runyon. 2008. “Child Sexual Abuse: From Prevention to Self‐protection.” Child Abuse Review 17 (1): 36–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/car.1012.

- Kuete, M., C. Li, F. Yang, Q. Huang, H. Yuan, H. C. Sipeuwou Ngueye, X. Ma, et al. 2021. “Family Planning Services Use: A Shared Responsibility between Men and Women of Reproductive Age in Hubei Province, China.” International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13704.

- Lazar, M. M. 2005. “Feminist CDA as Political Perspective and Praxis.” In Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis: Gender, Power and Ideology in Discourse, edited by M. M. Lazar, 1–28. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lazar, M. M. 2007. “Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis: Articulating a Feminist Discourse Praxis.” Critical Discourse Studies 4 (2): 141–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17405900701464816.

- Leung, H., D. T. L. Shek, E. Leung, and E. Y. W. Shek. 2019. “Development of Contextually-relevant Sexuality Education: Lessons from a Comprehensive Review of Adolescent Sexuality Education across Cultures.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (4): 621. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16040621.

- Liang, J. Y., and W. L. Bowcher. 2019. “Legitimating Sex Education through Children’s Picture Books in China.” Sex Education 19 (3): 329–345. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2018.1530104.

- Liao, W. 2013. I Taught My Daughter to Marry Well. Beijing: Beijing Press. (In Chinese).

- Liu, J., M. Cheng, X. Wei, and N. N. Yu. 2020. “The Internet-driven Sexual Revolution in China.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 153: 119911. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.119911.

- Liu, W. 2010. Cherish Lives – Sexuality Health Textbook for Pupils of Grade 1. Vol. 1 vols. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press. (In Chinese).

- Liu, W. 2011a. Cherish Lives – Sexuality Health Textbook for Pupils of Grade 1. Vol. 2 vols. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press. (In Chinese).

- Liu, W. 2011b. Cherish Lives – Sexuality Health Textbook for Pupils of Grade 2. Vol. 1 vols. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press. (In Chinese).

- Liu, W. 2013. Cherish Lives – Sexuality Health Textbook for Pupils of Grade 3. Vol. 2 vols. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press. (In Chinese).

- Liu, W. 2014a. Cherish Lives – Sexuality Health Textbook for Pupils of Grade 2. Vol. 2 vols. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press. (In Chinese).

- Liu, W. 2014b. Cherish Lives – Sexuality Health Textbook for Pupils of Grade 3. Vol. 1 vols. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press. (In Chinese).

- Liu, W. 2014c. Cherish Lives – Sexuality Health Textbook for Pupils of Grade 4. Vol. 1 vols. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press. (In Chinese).

- Liu, W. 2014d. Cherish Lives – Sexuality Health Textbook for Pupils of Grade 4. Vol. 2 vols. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press. (In Chinese).

- Liu, W. 2014e. Cherish Lives – Sexuality Health Textbook for Pupils of Grade 5. Vol. 1 vols. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press. (In Chinese).

- Liu, W. 2015. Cherish Lives – Sexuality Health Textbook for Pupils of Grade 5. Vol. 2 vols. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press. (In Chinese).

- Liu, W. 2016a. Cherish Lives – Sexuality Health Textbook for Pupils of Grade 6. Vol. 1 vols. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press. (In Chinese).

- Liu, W. 2016b. Cherish Lives – Sexuality Health Textbook for Pupils of Grade 6. Vol. 2 vols. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press. (In Chinese).

- Liu, W., and Y. Su. 2014. “School-based Primary School Sexuality Education for Migrant Children in Beijing, China.” Sex Education 14 (5): 568–581. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2014.934801.

- LoBue, V., and J. S. DeLoache. 2011. “Pretty in Pink: The Early Development of Gender-stereotyped Colour Preferences.” British Journal of Developmental Psychology 29 (3): 656–667. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835X.2011.02027.x.

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. 2008. “Guidelines for Health Education in Primary and Secondary Schools.” Beijing: Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. (In Chinese)

- Newman, L. 1989. Heather Has Two Mommies. New York: Alysson Books.

- Peng, A. Y. 2021. “Neoliberal Feminism, Gender Relations, and A Feminized Male Ideal in China: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Mimeng’s WeChat Posts.” Feminist Media Studies 21 (1): 115–131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2019.1653350.

- Peng, T. 2012. “Adolescent Sex Education from the Social Gender Perspective”. Chinese Sex Science 2012(8): 48–51. (In Chinese).

- Poulain, P. 2013. It’s Better to Explain These Things Sooner to Your Child. Beijing: Beijing Lianhe Press. (In Chinese).

- Robinson, K. H. 2013. Innocence, Knowledge and the Construction of Childhood: The Contradictory Nature of Sexuality and Censorship in Children’s Contemporary Lives. London: Routledge.

- Roien, L. A., C. Graugaard, and V. Simovska. 2018. “The Research Landscape of School-based Sexuality Education: Systematic Mapping of the Literature.” Health Education 118 (2): 159–170. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/HE-05-2017-0030.

- Surtees, N., and A. C. Gunn. 2010. “(Re)marking Heteronormativity: Resisting Practices in Early Childhood Education Contexts.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 35 (1): 42–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911003500107.

- Tang, Z. 2014. “Evaluation of Adolescent Sex Education Books in Mainland China since 1978.” Master’s thesis., East China Normal University. (In Chinese)

- Tang, Z., J. Wang, L. Tong, N. Tan, Y. Li, and X. Peng. 2013. “An analysis of the characteristics of the popular science books on adolescent sex education.” Chinese Sex Science. 2013 (7): 82–86. (In Chinese)

- Tsui, K. 1990. “Breaking Silence, Making Waves and Loving Ourselves.” In Lesbian Philosophies and Cultures: Issues in Philosophical Historiography, edited by J. Allen, 49–61. New York: SUNY Press.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific & Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). 2020. International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education: An Evidence-informed Approach for Schools, Teachers and Health Educators. Paris: UNESCO.

- Wang, Z. 1997. “Differentiation of Feminine Consciousness and Gender Consciousness.” Collection of Women’s Studies 1997 (1).

- Wu, A. X., and Y. Dong. 2019. “What Is made-in-China Feminism(s)? Gender Discontent and Class Friction in Post-socialist China.” Critical Asian Studies 51 (4): 471–492. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2019.1656538.

- Zhang, J. 2017. “The Protection of the Rights of Homosexuals in China – From the Perspective of Ronald Dworkin’s Thought.” PhD thesis., Southwest University of Political Science and Law. (In Chinese)

- Zhang, L., X. Li, and I. H. Shah. 2007. “Where Do Chinese Adolescents Obtain Knowledge of Sex? Implications for Sex Education in China.” Health Education 107 (4): 351–363. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09654280710759269.

- Zou, H., Z. Qu, and Q. Zhang. 2004. “Survey on Current Situation of Living and Protection Conditions of Migrant Children in China’s Nine Cities.” Youth Research 1: 1–13. (In Chinese).