ABSTRACT

Only a very few studies to date have comprehensively assessed children’s knowledge of sexuality. In this study, we examined the level of sexual knowledge among children aged 3–6 years in Finland. We analysed children’s explanations of what they saw in drawings related to genital naming, conception and childbirth, safety skills, and adult sexual activity. Levels of knowledge were generally low. The largest number of correct answers were given for genital naming and safety skills. Knowledge increased with age. Children’s gender was not related to their total level of knowledge. There was a correlation between children’s ability to name their genitals and their knowledge of safety skills. The results suggest that only what is known about can be protected. Building on the findings of this study, age-appropriate sexuality education should be provided to all children.

Introduction

Sexuality and sexuality education in early childhood often go unmentioned or opposed due to myths, tradition, and fears. The term sexuality often has adult connotations and sexuality is not seen as a part of childhood (Cacciatore et al. Citation2020; Brilleslijper‐Kater and Baartman Citation2000). While many sexuality issues only become relevant in adolescence, this is not the case for all topics. The objective of early sexuality education is to provide age-appropriate and safety-enhancing information about the body, rights, emotions and skills to protect physical integrity, and positive attitudes to reinforce a healthy body image (WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA Citation2010; Cacciatore, Korteniemi-Poikela, and Kaltiala Citation2019), to which all children are entitled (Cacciatore et al. Citation2020).

Importantly, children may encounter explicit sexual material online and need help dealing with it, hence the importance of preparing children for everyday social realities that, according to the European Court of Human Rights (Citation2018), justifies the provision of early sexuality education. In Finland, at 18 months, children spend on average over half an hour, and at 5-years-old more than two hours a day, using e-media devices (Niiranen et al. Citation2021). Of 5–6 and 7-year-olds respectively, 87% and 100% have their own telephone, of which 75% and 89% are smart phones (DNA Citation2022). Because of this, sexuality must be openly discussed with children from an early age in a manner appropriate to their developmental level (WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA Citation2010).

Attitudes about childhood sexuality and sexuality education vary considerably depending on culture, place, context and time. Finland is a comparatively open-minded country regarding sex and sexuality education. Sexuality education has been mandatory in schools since 2002 (Apter Citation2011), and since 2022, the mandatory national early childhood education and care (ECEC) curriculum (Finnish National Agency for Education Citation2022, 48) requires teachers and carers to ensure that ‘children’s age-appropriate curiosity towards sexuality and the body is guided respectfully’.

So far as we are aware, Finland is the only country where universal ECEC at all ages includes information related to sexuality, safety skills and the body equally for all children. Each child’s individual ECEC plan is made together with the child’s parents. Given the ubiquity of sauna culture, nudity is widely accepted in Finland and considered natural within the family. Yet talk about childhood sexuality may be taboo (Cacciatore et al. Citation2020) or unfamiliar to teachers and carers without appropriate training. Growing awareness of child sexual abuse may even strengthen the taboo against discussion of childhood sexuality. Without good quality research, there is no information regarding children’s level of knowledge about sexuality in Finland or whether this changes over time.

Children’s sexual expression, interests and knowledge differ from those of adolescents and adults (Cacciatore et al. Citation2020; Cacciatore, Korteniemi-Poikela, and Kaltiala Citation2019; Sandnabba et al. Citation2003). Only a few studies have explored comprehensively children’s perspectives on sexuality or current knowledge thereof (van Ham et al. Citation2021), the focus being mostly on childhood sexual abuse prevention (Wurtele and Kenny Citation2011). Studies assessing the sexual knowledge of non-abused young children would yield important information on their need for age-appropriate sexuality education.

Studying children’s sexuality is not easy (González Ortega Citation2020; Lyon Citation2014; de Graaf and Rademakers Citation2011). Retrospective accounts of early experiences may be distorted or inaccurate as memory fades with time and memories may be reconstructed based on current understandings (Lahtinen Citation2022). Asking parents and early education professionals is also problematic because of their attitudes, memory, background and willingness to report affect observations (de Graaf and Rademakers Citation2011). In addition, children also tend to hide their sexual play (Cacciatore et al. Citation2020). Beyond this, young children have limited vocabulary, social skills and ability to concentrate (de Graaf and Rademakers Citation2011). They are suggestible and tend to try to please adults with their answers. They may find questioning frightening and sense the unspoken nature of sexuality (Cacciatore et al. Citation2020). Finally, children may feel ashamed or guilty regarding their own sexual experiences and it is hard to be certain that they openly tell us what they know (van Ham et al. Citation2020).

The literature suggests variation across countries, ethnicities and socioeconomic status, as well as by sex, in levels of sexual knowledge among non-abused children aged 2–9 years (Goldman and Goldman Citation1982; Gordon, Schroeder, and Abrams Citation1990; Volbert Citation2000; Caron and Ahlgrim Citation2012; Wurtele, Melzer, and Kast Citation1992; Brilleslijper‐Kater and Baartman Citation2000; Bem Citation1989; van Ham et al. Citation2021). Children appear to have most knowledge about the names of genitals and sex differences, and least knowledge about safety skills, pregnancy and adult sexual behaviour. However, research on children’s sexual knowledge is scarce and relevant studies have been conducted in only a few countries.

To assess the sexual knowledge of young children, interviews have often been used (Wurtele Citation1993; Wurtele and Owens Citation1997), sometimes accompanied by drawings of the body (Wurtele, Melzer, and Kast Citation1992; Kenny and Wurtele Citation2008), or drawings covering sexuality more comprehensively (Gordon, Schroeder, and Abrams Citation1990; Volbert and Homburg Citation1996; Brilleslijper‐Kater and Baartman Citation2000; Brilleslijper-Kater Citation2005; van Ham et al. Citation2021), photographs (Bem Citation1989; Davies and Robinson Citation2010), and drawing assignments (Caron and Ahlgrim Citation2012). Existing studies have focused on children’s knowledge of sex differences, gender identity, body parts and their functions, adult sexual behaviour, pregnancy, childbirth, and safety skills. The main findings from studies using drawings are summarised in , showing that children’s level of knowledge increases with age but does not increase over time. Socio-cultural background seems to be more influential than age in affecting knowledge levels, meaning that lower-class children typically know less about sexuality than middle- and upper-class children, regardless of age.

Table 1. Drawing-assisted interview studies of non-abused children’s sexual knowledge*.

The Nordic countries are considered progressive regarding sexuality education, but no research from Finland has been published on sexual knowledge elicited directly from children. In this study, we aimed to ascertain what 3–6-year-olds attending Finnish early education know about sexuality (genital naming, conception and childbirth, adult sexual behaviour, and safety skills) and how this knowledge relates to the child’s age or sex. The hypothesis was that Finnish children would have at least as much sexual knowledge as similarly aged children in earlier research conducted in other countries and would express it freely. Findings would help determine what knowledge, skills and attitudes best support and protect their sexual development.

Methods

Study design

The study was conducted between September-November 2019. It used a structured interview in which children responded to drawings. We chose to use open-ended questions and quite complex drawings of social situations to elicit responses, because young children respond better to concrete stimuli, and because verbal questioning without the use of visual aids might be too abstract for them (e.g. Brilleslijper‐Kater and Baartman Citation2000).

The study was conducted in seven municipal early childhood education units in two metropolitan municipalities, RII and HEI (pseudonyms), with approximately 30,000 and 660,000 inhabitants respectively. Both municipalities have recently (2017 and 2019) begun to include sexuality education in the mandatory local ECEC curriculum, but without systematic staff training. The proportion of multicultural families in the studied units varied between 25% and 56%. Our goal was to include at least 40 children of each of the following age groups (3, 4, 5, 6-year-olds), with an equal number of girls and boys in each. We included 3–6-year-olds in the study because 2-year-olds tend to express themselves more non-verbally than verbally, and because in Finland 7-year-olds already attend school.

We (RC, SIF) submitted the study description, pictures and interview protocol to early childhood education professionals in each of the study sites via email and at a briefing meeting. The professionals distributed information and consent forms to the parents of attending 3–6-year-old children and collected the parental consent forms. Only agreements were returned and counted. Early education teachers familiar to the children then conducted the interviews in their respective units.

LÖ attended the interviews and trained the teachers in how to carry out the interviews. It was emphasised that the child should be free to answer each question openly. If a child did not understand a question or was afraid to answer, teachers were advised to encourage them with more direct, but not leading, questions. At the beginning of each session, the researcher greeted the child; set up the audio-recording; and registered the child’s age, sex and observed their behavioural reaction on arrival (e.g. relaxed, tense, giggly). They also noted any special events, such as interruptions. Other background factors were not assessed. After the interviews had been transcribed and anonymised, the audio recordings made during the interviews were destroyed.

A warmup picture was shown first to engage the child. The teacher then asked the child open-ended questions about what was happening in the pictures and how the children or adults depicted in the pictures might feel in that situation.

Study instruments

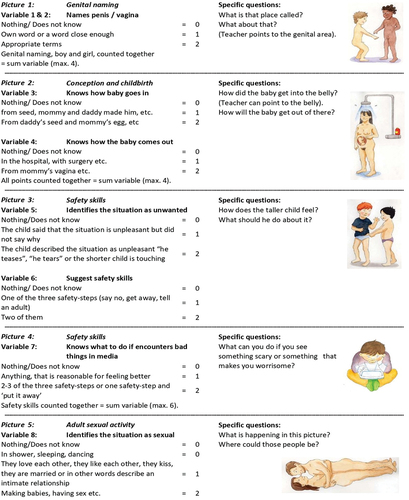

We developed ten specially designed drawings for the study and one additional drawing for the warmup drawing featuring two running children. The drawings and the interview protocol were designed by experts in childhood sexuality education (SI-F), early education (NS), child psychiatry (RC), forensic interviewing of children (SV, JK), and childhood sexual knowledge studies (RV). Sample illustrations, inspired by the work of Volbert and Homburg (Citation1996, Citation2000), are shown in . The questions associated with the different pictures were of the following type.

I’ll show you some pictures and you can tell me what you see. What is happening in this picture? What are the children doing? What are those people thinking or saying? Tell me how the baby will get out of the tummy? Very good!

The interview protocol was based on those used in earlier studies (Volbert Citation2000; Brilleslijper‐Kater and Baartman Citation2000) and the WHO Standards for Sexuality Education in Europe 2010. The interview covered eight topics as follows: (1) the human body and human development; (2) fertility and reproduction; (3) sexuality; (4) emotions; (5) relationships and lifestyles; (6) sexuality, health, and well-being; (7) sexuality and rights; (8) social and cultural determinants of sexuality (values/norms). The protocol determined the order in which the pictures were presented, and the questions asked. The children’s answers were not corrected in any way.

Variables and scoring analyses

For this paper, we analysed responses related to the topics of genital naming; conception and childbirth; safety skills (two drawings); and adult sexual activity, all of these together five drawings. We asked one or two questions per picture, which resulted in eight question variables.

Children’s responses were scored on a scale of 0–2 as follows: 0= does not know, 1= partial knowledge, 2= adequate knowledge. We also calculated an overall summed score across all the items (0–16 points) and separate summed scores for genital naming (2 items), conception and childbirth (2 items), and safety skills (3 items). If the interviewer deviated too far from the protocol (e.g. by asked a leading question such as ‘They are happy, aren’t they?’ or did not ask anything, etc.), a score of 0 was given.

The ratings were made by two independent raters (LÖ, JKon). The raters also scored 24 common questions to test inter-rater reliability of the scoring. The inter-rater reliability was very high (r = 0.97), with the raters giving the same score in 96% of the questions.

Statistical analyses

We first determined the frequencies of correct, partially correct, and ‘do not know’ answers to each topic, and then calculated correlations between different items using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The mean (and standard deviation) of the general level knowledge summed scores was calculated for each age group (3, 4, 5, 6-year-olds), and the age groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Associations of age and gender with the summed scores and individual items were analysed using ordinal logistic regression, with the responses coded as 0 (does not know), 1 (partially correct), and 2 (correct). The results were expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Child’s sex and age were entered into the model simultaneously. Analyses were run separately for all the question items and for the summed variables measuring general knowledge of all topics. SPSS software was used for all the analyses.

Ethics

The University of Helsinki Ethics Review Board in Humanities and Social and Behavioural Sciences approved the research protocol for the study (Ref 34/2019). We also sought and received permission to conduct the research from both municipalities. Parents were informed in advance and written permission was obtained for children’s participation. Participation was completely voluntary, and the withdrawal was possible at any time. No payments were made to participants. The children had the opportunity to refuse to participate or discontinue their involvement in the study.

Results

Participants

A total of 143 3–6-year-old children were interviewed, but 11 of these interviews were excluded: five were interrupted because of the child’s restlessness or unwillingness to participate and six children fell outside the target age group. Thus, the final data included responses from 132 children (70 boys and 62 girls) ().

Table 2. Age, sex, number and the percentage of all participants.

Qualitative observations of the children’s reactions in the interviews

Upon arrival, about half of the children seemed to be at ease (relaxed position, made eye contact, interacted verbally), whereas the others appeared to be tense or nervous (rigid position, quiet and brief answers). In addition, when pictures with nudity were shown, some children started responding by whispering, rapidly turning to the next picture, and frequently responded with ‘I don’t know’. Some 6-year-olds said, for example, ‘Yuck!’ or ‘I’m not supposed to say that word’ when it came to the genital naming picture, as in the following example:

(What’s the name of that place?) ‘Don’t know’ (You don’t know. Mm … What about that?) ‘Don’t know’ (You don’t know …) ‘I’m not supposed to say that’ (You must not say …) ‘They are toilet words’ ([…] Would you have known them?) ‘I do not want to say’

The children looked for longer and talked more when presented with pictures that including children. Towards the end, some children appeared to become tired or bored, merely glancing at the pictures, talking less and more frequently responding ‘I don’t know’.

Item-by-item level of knowledge

The percentages of correct, partially correct, and wrong/no answers for each topic are presented in . The children were most knowledgeable about genital naming and recognising peer-to-peer harassment as unpleasant (Picture 3, ). Additional details and examples are given below.

Table 3. Percentage of incorrect (does not know), partially correct, and correct answers.

Picture 1: genital naming

Of the children who answered, almost all used the well-established names that children used to describe genitals pimppi/pimpsa (vulva) and pippeli/kikkeli (penis), which we scored as correct. Of all the children, 51.5% (n = 68) correctly named the female genitals, while 3.8% (n = 5) used an incorrect name, such as butt/bottom. Nearly half of the children (44.7%, n = 59) could not or did not want to answer the questions about the female genitals. Slightly more, 61.4% (n = 81), named the male genitals correctly, while 4.5% (n = 6) used an uncommon or incorrect name. One third (34.1%, n = 45) did not know or want to answer.

No children used anatomically correct adult terms such as vulva/vagina or penis. Of the children, 45.5% (n = 59) named both genitals correctly. Of those who named the female genitals correctly, 88.2% (n = 60) also named the male genitals correctly. Of those who named the male genitals correctly, 74.1% (n = 60) also named the female genitals correctly.

Both sexes knew the names of their own genitals best: 56.5% (n = 35) of girls named the female genitals, 53.2% (n = 33) the male genitals, and 48.4% (n = 30) both male and female genitals; 45.7% (n = 32) of boys named the female genitals, 68.6% (n = 48) named the male genitals, and 42.9% (n = 30) both male and female genitals.

There was no significant difference in girls’ ability to name male and female genitals, whereas boys were more likely to name male than female genitals.

Picture 2: conception and childbirth

Using Picture 2 of a pregnant naked woman showering, we asked how the baby got into the tummy. Three percent (n = 4) of the children showed some knowledge, all of them 5-year-old girls, while 97% (n = 128) expressed no knowledge. One child said that the father gives the seed, one talked about seeds more generally, one mentioned that adults play together to get a baby, and one mentioned that the baby goes in and comes out from the same hole. None referred directly to intercourse or other sexual activities.

When asked how the baby comes out, 39.4% (n = 52) of the children referred to either genital delivery (22.0%, n = 29) or Caesarean section (17.4%, n = 23) and 60.6% (n = 80) expressed no knowledge or no correct knowledge.

Picture 3 and 4: safety skills

Related to Picture 3 of a child pulling another’s pants, 88.6% (n = 117) of the children described the act as unpleasant. No-one mentioned the full Three-Step Rule: say no, go away, tell an adult you trust (Wurtele Citation1993; WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA Citation2010). Only 2.3% (n = 3) said the child should say no and tell an adult, and 56.1% (n = 74) mentioned at least one of these steps. The remaining children (41.7%, n = 55) said nothing or suggested other responses, such as hitting.

In Picture 4, a worried-looking child had a tablet computer in their lap. Most children noticed that the child was sad or worried, but some reported reasons unrelated to safety, such as that the child was hungry, the tablet battery had run out, or the child had lost a game.

If a child said that the child in the picture had seen something unpleasant (85.6%, n = 113), they were then asked what the child should do. Of these, 0.9% (n = 1) said that the child could turn off the scary content and tell an adult, and 36.3% (n = 41) offered one such response. More than half (62.8%, n = 71) of the children suggested other actions such as to go to eat or to play, or did not know what to do.

Picture 5: adult sexual activity

In this picture, a naked adult man and woman are embracing on top of each other. Most children (84.8%, n = 112) gave an explanation without any reference to sexuality, for instance that the adults were taking a shower, a sauna, or bath, were at home, or shopping. Some intimacy in the relationship between adults was mentioned by 15.2% (n = 20) of the children, such as being married or a mother and father hugging or kissing. None referred to sex, intercourse, reproduction or the like. Often children rotated the horizontal image upright so as to get the adults to appear standing in the picture.

Gender differences

The only significant gender difference in girls’ and boys’ levels of knowledge was in naming genitalia: boys named male genitalia significantly more often ().

Table 4. Pearson correlation coefficients between items.

Table 5. Associations of age and sex with sexuality-related knowledge level variables.

Item by item correlations

shows the correlations between all item responses. Items 1, 2, 5, 6 and 7 showed statistically significant correlations, which indicated that children who were able to correct name the genitals (items 1, 2) were also likely to be aware of sexuality-related safety skills (items 5, 6, 7). There was also a correlation between being able to name the male and female genitals and knowing where a baby comes out (items 1, 2, and 4). No statistically significant correlation was found between items related to adult sexual interaction and conception (items 3, 8) and the other items.

The relationship between age, sex, and knowledge

Level of knowledge increased with age (M = 5.7, SD = 3.0). The mean level of knowledge (possible range between 0–16) was 3.5 among 3-year-olds and 7.2 among 6-year-olds (). Age was related to better knowledge on all items, except for reproduction and adult sexual activity (). Girls were significantly (53%) less likely than boys to correctly name the penis. The child’s sex did not correlate with any other variables ().

Discussion

The level of sexuality-related knowledge expressed by 3–6-year-olds in Finland was surprisingly low compared to earlier similar studies conducted in the USA (Gordon, Schroeder, and Abrams Citation1990), Germany (Volbert and Homburg Citation1996), and the Netherlands (Brilleslijper‐Kater and Baartman Citation2000; Brilleslijper-Kater Citation2005; van Ham et al. Citation2021) with several (14–29) drawings covering sexuality comprehensively (). The most correct answers were related to genital naming and safety skills, and the least correct answers related to conception and adult sexual behaviour. Age correlated positively with level of knowledge in all variables except those related to conception and adult sexual behaviour, where the children provided little information, as in most earlier studies (Gordon, Schroeder, and Abrams Citation1990; Brilleslijper‐Kater and Baartman Citation2000; Volbert Citation2000). We found no differences between the sexes in sexuality-related knowledge. A recent Dutch study found that girls score more correct answers than boys in all topics (van Ham et al. Citation2021).

Genital naming

The children expressed the highest level of knowledge regarding genital naming, as in other research (Gordon, Schroeder, and Abrams Citation1990; Volbert Citation2000; van Ham et al. Citation2021). Oddly, in this study only about half of the children named both genitals correctly.

In an earlier study conducted in Germany, Volbert (Citation2000) found that 75–83% (n = 147, 2–6-year-olds) gave some label to both genitals. In a parallel study in the Netherlands, Brilleslijper-Kater and Baartman (Citation2000) found that 95% of children were able to give a name to the penis and 78% to the vagina (n = 63, 2–6-year-olds) when any reasonably appropriate name for the genitals was considered correct. On the other hand, far fewer children were able to name the genitals in a US study when only the anatomically correct words penis and vagina were accepted as correct (Wurtele, Melzer, and Kast Citation1992). In a later study, also conducted in USA, children who preferred speaking English reported more names for genitals than first language Spanish-speaking children, who reported none, indicating a possible link between knowledge and cultural taboos (Kenny and Wurtele Citation2008).

It seems rather unlikely that almost half of 3–6-year-olds in Finland do not know any terms for the genitals. This ‘lack’ of knowledge may be related to societal norms and difficulty mentioning specific terms in the presence of only adults, rather than ignorance. Early education professionals often view all the language used to describe the genitals, poop, farting and so on, as ‘toilet words’, which strengthens the taboo concerning their use (Öhrmark Citation2021).

As in several earlier studies (Bem Citation1989; Gordon, Schroeder, and Abrams Citation1990; Wurtele Citation1993; Volbert and Homburg Citation1996; Brilleslijper‐Kater and Baartman Citation2000; Kenny and Wurtele Citation2008; van Ham et al. Citation2021), children in this study were more knowledgeable about male than female genitals, and boys found greater difficulty naming female genitals.

Conception, pregnancy and childbirth

Hardly any children in this study demonstrated an even partial knowledge about conception. These results are in line with those of others (Goldman and Goldman Citation1982; Gordon, Schroeder, and Abrams Citation1990; Volbert Citation2000; Brilleslijper‐Kater and Baartman Citation2000; Brilleslijper-Kater Citation2005; Caron and Ahlgrim Citation2012). Knowledge of conception was not related to age, sex or overall level of knowledge of the child, suggesting other underlying reasons such as the sexuality education received and the child’s socio-cultural background.

Most of the children did not know how a baby is born. This corroborates Gordon’s and Volbert’s findings (Gordon, Schroeder, and Abrams Citation1990; Volbert Citation2000), although their study used leading questions as also did a Dutch study, where none of the participating 2–6-year-olds knew where a baby comes out Brilleslijper‐Kater and Baartman (Citation2000) even when presented with suggestions such as the navel, mouth, anus, vagina and an opening in the tummy.

Adult sexual activity

The children reported little understanding of adult sexual activity and, as in earlier studies, level of knowledge did not appear to increase with age (Gordon, Schroeder, and Abrams Citation1990; Brilleslijper‐Kater and Baartman Citation2000; Volbert Citation2000; van Ham et al. Citation2021). Even 8-year-olds were as unaware of adult sexual activity as younger children in a recent Dutch study (van Ham et al. Citation2021). This strongly suggests that the topic is mostly not explained to children, or they sense its unmentionable nature.

Children’s knowledge of where babies come from, and adult sexual activity was not connected to any of the other topics studied (). It appears that knowledge of ‘private’ body parts and sexuality-related safety skills can be taught and understood with no linked understanding of either conception or adult sexual activity. Knowledge of pregnancy, birth, reproduction and adult sexual behaviours generally increases later in childhood, but there are differences between countries (de Graaf and Rademakers Citation2011).

Today, media and peer information compete with the knowledge provided by families. In 2019, 70–95% of 3–6-year-olds in Finland attended kindergarten (Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare Citation2020) with peers. In this age group, the parents of the children are often of childbearing age and become pregnant, and many children find themselves with siblings. As Cacciatore et al. (Citation2020) have observed, children ask about numerous topics related to sexuality in kindergarten where a simple child-level explanation of pregnancy, conception and adult sexuality could help them deal with the varied and confusing sexual health information they encounter.

Safety skills

Two safety images depicted inappropriate peer-to-peer sexual threat and encountering inappropriate material on a smart device. In these situations, children already need the safety skills as to say no, go away and sometimes tell an adult to get explanations or help. If children know these safety skills relevant to everyday situations (e.g. via the Three-Step Rule), they may be able to use the same skills in more serious situations.

The full Three-Step Rule was not mentioned by any of the children interviewed. Only one comprehensive drawing-assisted study has addressed this topic (Gordon, Schroeder, and Abrams Citation1990). Children’s knowledge about safety skills in Gordon’s study was greater than in ours, perhaps because of the use of leading questions, such as who to tell if something happened. In both Gordon et al’s and our study, however, age correlated strongly with an increase in knowledge. Also, the correlation between children’s ability to name their private parts and their knowledge of safety skills was evident in both studies, suggesting that only what is known and named can be protected, and those children who feel that private body parts should not be discussed with adults, may find it difficult to report possible abuse.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study in Finland to explore the sexual knowledge of very young, and the second largest of only five comparable drawing-assisted studies that employed a wide-ranging approach to sexuality. We were able to collect data directly from a group of culturally diverse children. Many earlier studies collected data primarily from upper-class, native-born, intelligent children (Gordon, Schroeder, and Abrams Citation1990; Brilleslijper‐Kater and Baartman Citation2000; Brilleslijper-Kater Citation2005; van Ham et al. Citation2021).

Using a quantitative method facilitated comparison with other studies. The structured interview protocol enabled us to score and compare the children’s responses. Interrater reliability in this study was high. To ensure anonymity, we did not video record the interviews, so detailed non-verbal reactions could not be assessed. Nevertheless, audio recording yielded good quality verbal accounts. For the sake of comparison, in this paper we analysed responses to only five pictures. A more holistic understanding of childhood sexuality could be achieved by analysing more of them, covering topics such as love, diversity, body image and sexual curiosity, which are central in childhood (Cacciatore et al. Citation2020; Cacciatore, Korteniemi-Poikela, and Kaltiala Citation2019; González Ortega Citation2020).

The children in this study were interviewed briefly by female early childhood education teacher who was familiar to them, while most earlier studies used specialist interviewers over a longer period of time (Wurtele Citation1993; Brilleslijper‐Kater and Baartman Citation2000; Goldman and Goldman Citation1982). It is important to recognise that teachers occupy a position of power over children and their interviewing skills likely vary.

One limitation of the present study was that we collected no information on background socioeconomic and cultural factors. These are likely to influence children’s knowledge of sexuality and willingness to talk openly about it (Kenny and Wurtele Citation2008). Finally, our findings represent experience in densely populated areas of Finland rather than in smaller towns or rural areas.

Conclusions

In this study, we found the level of sexuality-related knowledge among 3–6-year-olds to be generally low. Genital naming and safety skills were most familiar. The correlation between children’s ability to name their body parts and their knowledge of safety skills suggests that only what is known about and can be named can be protected against. Knowing the names of genitals makes it easier to recognise and disclose sexual abuse, laying the groundwork for future sexuality education.

To support well-being and safety, young children should be able to talk about sexual issues with trusted adults they know. Bodily safety and age-appropriate comprehensive sexuality education should be guaranteed and provided to all children. The cultures of children’s families are diverse, so as part of early education children should be taught straightforward terms for the body parts and the value of openness.

To reach all children, including sexuality education as a compulsory part of early childhood education and care is essential. More research is needed, however, on how to understand, support and protect childhood sexuality and to ascertain how age-appropriate sexual knowledge can best be provided to children in the early years.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Family Federation of Finland for facilitating the study. Elements of the study appear in a master’s thesis submitted by the second author to Helsinki University (Öhrmark 2021).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Apter, D. 2011. “Recent Developments and Consequences of Sexuality Education in Finland.” FORUM Sexuality Education and Family Planning 2: 3–8.

- Bem, S. 1989. “Genital Knowledge and Gender Constancy in Preschool Children.” Child Development 60 (3): 649–662. doi:10.2307/1130730.

- Brilleslijper‐Kater, S., and H. Baartman. 2000. “What Do Young Children Know About Sex? Research on the Sexual Knowledge of Children Between the Ages of 2 and 6 Years.” Child Abuse Review 9 (3): 166–182. doi:10.1002/1099-0852(200005/06)9:3<166:AID-CAR588>3.0.CO;2-3.

- Brilleslijper-Kater, S. 2005. “Sexual Knowledge in Sexually Abused and Non-Abused 3- to 7-Year-Old Children.” Beyond Words: Between-Group Differences in the Ways Sexually Abused and Nonabused Preschool Children Reveal Sexual Knowledge. PhD diss., Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

- Cacciatore, R., S. Ingman-Friberg, D. Apter, N. Sajaniemi, and R. Kaltiala. 2020. “An Alternative Term to Make Comprehensive Sexuality Education More Acceptable in Childhood.” South African Journal of Childhood Education 10 (1): 1–10. doi:10.4102/sajce.v10i1.857.

- Cacciatore, R., S. Ingman-Friberg, L. Lainiala, and D. Apter. 2020. “Verbal and Behavioral Expressions of Child Sexuality Among 1–6-Year-Olds as Observed by Daycare Professionals in Finland.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 49: 2725–2734. doi:10.1007/s10508-020-01694-y.

- Cacciatore, R., E. Korteniemi-Poikela, and R. Kaltiala. 2019. “The Steps of Sexuality—a Developmental, Emotion-Focused, Child-Centered Model of Sexual Development and Sexuality Education from Birth to Adulthood.” International Journal of Sexual Health 31 (3): 319–338. doi:10.1080/19317611.2019.1645783.

- Cacciatore, R., K. Porras, and M. Kalland. 2020. “Safe Body-Emotion Education and Sexuality Education.” In Non-Violent Childhoods – Action Plan for the Prevention of Violence Against Children 2020–2025, edited by U. Korpilahti, H. Kettunen, and E. Nuotio, et al., 176–190. Helsinki: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.

- Caron, S., and C. Ahlgrim. 2012. “Children’s Understanding and Knowledge of Conception and Birth: Comparing Children from England, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United States.” American Journal of Sexuality Education 7 (1): 16–36. doi:10.1080/15546128.2012.650970.

- Davies, C., and K. Robinson. 2010. “Hatching Babies and Stork Deliveries: Risk and Regulation in the Construction of Children’s Sexual Knowledge.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 11 (3): 249–262. doi:10.2304/ciec.2010.11.3.249.

- de Graaf, H., and J. Rademakers. 2011. “The Psychological Measurement of Childhood Sexual Development in Western Societies: Methodological Challenges.” Journal of Sex Research 48 (2–3): 118–129. doi:10.1080/00224499.2011.555929.

- DNA. 2022. “Koululaistutkimus 2022.” [school student survey] Available at: https://corporate.dna.fi/documents/753910/11433306/DNA+Koululaistutkimus+2022.pdf/45cbcfcd-0308-be26-d7c5-a6f32a6a02d8?t=1649764482372

- European Court of Human Rights. 2018. “Refusal to Exempt Primary School Pupil from Sex Education Did Not Breach Convention.” Press Release, January 18 Available at: https://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/FS_Childrens_ENG.pdfhttps://www.strasbourgconsortium.org/common/document.view.php?docId=7501

- Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. 2020. Tilastoraportti 33/2020 [Statistical report]. Published 29 September 2020. Available at: https://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/140541/Tr33_20.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y

- Finnish National Agency for Education. 2022. “National Core Curriculum for Early Childhood Education and Care.” Available at: https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/National%20core%20curriculum%20for%20ECEC%202022.pdf

- Goldman, R., and J. Goldman. 1982. Children’s Sexual Thinking: A Comparative Study of Children Aged 5 to 15 Years in Australia, North America, Britain and Sweden. Lawrence, MA: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- González Ortega, E. 2020. “Research on Childhood Sexuality: Limitations and Recommendations.” Summa Psicológica UST 17 (1): 62–69. doi:10.18774/0719-448x.2020.17.455.

- Gordon, B., C. Schroeder, and J. Abrams. 1990. “Age and Social-Class Differences in Children’s Knowledge of Sexuality.” Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 19 (1): 33–43. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp1901_5.

- Kenny, M., and S. Wurtele. 2008. “Preschoolers’ Knowledge of Genital Terminology: A Comparison of English and Spanish Speakers.” American Journal of Sexuality Education 3 (4): 345–354. doi:10.1080/15546120802372008.

- Lahtinen, H. -M. 2022. Child Abuse Disclosure, from the Perspectives of Children to Influencing Attitudes, and Beliefs Held by Interviewers, PhD diss., University of Eastern Finland.

- Lyon, T. 2014. “Interviewing Children.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 10: 73–89. doi:10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110413-030913.

- Niiranen, J., O. Kiviruusu, R. Vornanen, O. Saarenpää-Heikkilä, and J. Paavonen. 2021. “High-Dose Electronic Media Use in Five-Year-Olds and Its Association with Their Psychosocial Symptoms: A Cohort Study.” BMJ Open 11: 11(e040848. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040848.

- Öhrmark, L. 2021. “Mitä 3–6-vuotiaat lapset tietävät seksuaalisuudesta?” [What do 3-to-6-year-old Children Know about Sexuality?]. Master’s thesis, University of Helsinki. Available at: http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:hulib-202108253503

- Sandnabba, N. K., P. Santtila, M. Wannäs, and K. Krook. 2003. “Age and Gender Specific Sexual Behaviors in Children.” Child Abuse & Neglect 27 (6): 579–605. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00102-9.

- van Ham, K. E., S. Hoytema-van Konijnenburg, A. Brilleslijper-Kater, J. G. Schepers, A. Daams, R. R. Teeuw, R. R. van Rijn, and J. H. Van der Lee. 2020. “A Systematic Review of Instruments to Assess Nonverbal Emotional Signs in Children During an Investigative Interview for Suspected Sexual Abuse.” Child Abuse Review 29 (1): 12–26. doi:10.1002/car.2601.

- van Ham, K. S., S. van Delft, R. Brilleslijper-Kater, J. van Rijn, J. van Goudoever, J. H. van der Lee, and A. Teeuw. 2021. “Reactions of Non-Abused Children Aged 3–9 Years to the Sexual Knowledge Picture Instrument: An Interview-Based Study.” BMJ Paediatrics Open 5: 1. doi:10.1136/bmjpo-2021-001128.

- Volbert, R. 2000. “Sexual Knowledge of Preschool Children.” Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality 12 (1–2): 5–26. doi:10.1300/J056v12n01_02.

- Volbert, R., and A. Homburg. 1996. ““Was wissen zwei-bis sechsjährige Kinder über Sexualität?.” [What do children aged 2–6 know about sexuality].” Zeitschrift fur Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie 28: 210–227.

- WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA. 2010. Standards for Sexuality Education in Europe: A Framework for Policy Makers, Educational and Health Authorities and Specialists. Cologne: BZgA. Available at: https://www.bzga-whocc.de/en/publications/standards-in-sexuality-education/

- Wurtele, S. 1993. “Enhancing Children’s Sexual Development Through Child Sexual Abuse Prevention Programs.” Journal of Sex Education and Therapy 19 (1): 37–46. doi:10.1080/01614576.1993.11074068.

- Wurtele, S., and M. Kenny. 2011. “Normative Sexuality Development in Childhood: Implications for Developmental Guidance and Prevention of Childhood Sexual Abuse.” Counseling and Human Development 43 (9): 1–24.

- Wurtele, S., A. Melzer, and L. Kast. 1992. “Preschoolers’ Knowledge of and Ability to Learn Genital Terminology.” Journal of Sex Education and Therapy 18 (2): 115–122. doi:10.1080/01614576.1992.11074045.

- Wurtele, S., and J. Owens. 1997. “Teaching Personal Safety Skills to Young Children: An Investigation of Age and Gender Across Five Studies.” Child Abuse & Neglect 21 (8): 805–814. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00040-9.