ABSTRACT

Amidst multiple foreign policy flip-flops of the Turkish government, the Middle East is where observers agree most about the explanatory priority of ideational factors over realpolitik calculations. The assertive foreign policy activism to extend the country’s role in the region has largely been linked to the Islamist leanings of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP). This study revisits Turkey’s Middle East policy with a particular focus on the AKP’s relations with the Muslim Brotherhood (Ikhwan al Muslimin), which marked Turkish foreign policy formulation and implementation in multiple theatres from Yemen to Egypt to Libya. Using a neoclassical realist approach, it argues that the AKP’s ideological ties to the Ikhwan are significant for the availability of new resources but Turkish foreign policy behavior in the Middle East, including relations with the Ikhwan, reflects a grand strategy to respond to systemic and sub-systemic stimuli.

Introduction

In 2011, scholar Tariq Ramadan, grandson of the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood (al Ikhwan al Muslimin, hereafter Ikhwan), suggested that “Democratic Turkey is the template for Egypt's Muslim Brotherhood.”Footnote1 In the heyday of the Arab Uprisings, Turkey’s ex-Islamists-turned-conservative-democrats were believed to inspire Islamists in the Middle East, in particular the various affiliates of Ikhwan, which were the “Arab Spring’s largest immediate beneficiaries.”Footnote2 However, while the conventional idea of a Muslim-democratic “Turkish Model,” as embodied in the ruling Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP), soon lost its relevance, some began to argue that the AKP and its leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, were pursuing an Islamist foreign policy based on Ikhwan links and ideology. Put differently, the template identified by Ramadan had, arguably, been reversed. This article casts a more critical view on such claims.

Invoking the glories of the Ottoman period, the AKP has engaged in a (neo)imperial project, a phenomenon well-described in Hakan Yavuz’s contribution to this special volume.Footnote3 Throughout its two-decades of rule, it has been invested in the Middle East more than in any other region. When compared to the Republic’s history, this unmatched level of Middle Eastern involvement—along with the country’s drift away from its Western orientation in the 2010s—has been subject to ideational readings and related to the AKP’s Islamist identity as an “independent driver” of its foreign policy.Footnote4 For many observers, the AKP’s approach to Ikhwan and the Middle East is devoid of instrumental rationality. Some argue that Erdoğan, despite his pragmatism, has been “a captive of his ideological convictions.”Footnote5 Others even question the mental condition of Turkey’s “Islamist” strongman and project him as the nearest approximation of a mad king pursuing over-ambitious foreign policy activism in the region.Footnote6

Countering the overwhelming domestic and ideational readings in the academic literature,Footnote7 this article suggests that a fine-tuned, outside-in approach anchored in several systemic factors is better-suited to explain the underlying dynamics beneath Turkey’s Middle East policy. It employs neoclassical realism, which offers a holistic understanding of whether foreign policy behavior is exogenously determined by the material conditions of the international system or endogenously by collective ideas and other domestic factors.Footnote8 A growing body of literature draws on this approach to examine Turkish foreign policy in general,Footnote9 and Middle East policy in particular.Footnote10 This article seeks to contribute to the literature by delving into the heart of the debate and, in a most likely case design, calls into question the validity of a more ideational reading of Turkish foreign policy in the area where it is likely to be most persuasive. It focuses on the AKP’s Middle East policy vis-à-vis its relationship with the Ikhwan, which, allegedly, forms the basis of its “Islamist” foreign policy reflexes.

Despite the centrality of the topic, references to various Ikhwan branches in the academic field are thin and scattered. This paper intends to develop a holistic outlook on the AKP-Ikhwan relations. It is not exhaustive, but suggestive of the rich scope of the developments in the post-Arab Uprisings era. The central argument is that, while the AKP’s ideological ties to Ikhwan made resources available in the competitive logic of proxy warfare, Turkey’s grand strategy and Ikhwan’s role in it largely follow systemic incentives and constraints envisioned in structural perspectives. It begins with a brief critique of the ideational readings that grant Islamist/Ikhwan ideology a central explanatory role in Turkey’s Middle East policy. As an alternative explanation, it analyzes systemic and sub-systemic imperatives and their implications for Turkish foreign policy towards the region. In the following sections, it discusses Ikhwan’s role in Turkey’s vision for a new regional order and assesses how the unit-level variables affected the decisions of the foreign policy executive in this regard.

Ikhwan ideology and foreign policy

The recurrent emphasis on the AKP’s Islamist orientation in Middle East policy establishes a sharp contrast between the old Kemalist politics of avoidance and Turkey’s current assertiveness in the region. Since 2009, the “shift of axis” debate has highlighted the AKP’s increasing involvement in the Middle East as a foreign policy manifestation of its Islamist identity and, consequently, Turkey’s retreat from Kemalist secularism and Westernization.Footnote11 At the regional level, too, Turkey is part of a supposedly ideational struggle for the soul of Islam, depending on one’s affinity for Ikhwan. This rivalry is framed ideologically as “‘moderate versus Islamist’ for Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, and ‘competitive democracy versus authoritarian monarchy’ for Ankara.”Footnote12 Whether religion is seen either as a primordial entity or social construct, ideational readings treat it as a self-standing referent that informs foreign policy perceptions and choices. From a broader perspective, ideas and beliefs matter a) as a meaning-making heuristic and cognitive short-cut, guiding policymakers’ actions; b) as an institutional framework, building the Zeitgeist or shared systems of thought in any setting; or c) as strategic tools used to craft political discourse and mobilization.Footnote13 Neoclassical realism recognizes the significance of ideas and beliefs such as religion as a transmission belt between systemic stimuli and foreign policy outputs. However, they are “analytically subordinate to the systemic factors, the limits and opportunities of which states cannot escape in the long run.”Footnote14

Against the purported parochialism of area studies, Turkey-focused readings need to be put under comparative lenses for validity. Islamism, as an independent variable in foreign policy, is not enough to explain similar foreign policy behaviors of other regional players. For instance, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), dubbed “Little Sparta,” has been equally aggressive in filling the perceived void left by the United States’ (US) indifference and imposing its vision on the region.Footnote15 From building a rimland of militias in Yemen to arm transfers for the rebels and Emirati fighters in Libya, this power projection hardly relates to any religiously-inspired agenda. Similarly, the prime motivation of Qatar’s Wahhabi leaders in siding with Turkey in several regional conflicts was power maximization, not religion.Footnote16 While it is true that as a small state with grand ambitions and few constraints, Qatar’s support for actors in the Islamist spectrum makes it an essential part of the key conversations shaping the region, this support is largely considered instrumental, if not opportunistic, since Doha has sought influence through access to various political actors (Islamist and non-Islamist) abroad. In a similar vein, ideational readings attribute too much substance and coherence to the AKP’s political identity and ideology. Erdoğan’s dance with diverse political ideologies, from conservative democracy to Islamism to Turkish nationalism, invites a more nuanced reading.Footnote17

In terms of agent orientation, several observers point to the AKP’s ideological kinship with Ikhwan, even referring to the party as its Turkish branch.Footnote18 The AKP’s antecedent, the National Outlook (Millî Görüş) Movement and its affiliated political parties under Necmettin Erbakan had a larger overlap with Ikhwan’s world view, with the connections even gaining a personal level when Erbakan’s niece married Ibrahim el-Zayat, the head of Ikhwan’s organization in Germany. Erbakan’s Welfare Party hosted several top Ikhwan figures at its party congress in 1993, including Mustafa Mashhur and Mahdi Akif. The AKP maintained such ties, as evidenced by Hamas leader Khaled Meshal’s 2006 visit to Ankara or the AKP’s hosting of Mohamed Morsi, the head of the Ikhwan’s Freedom and Justice Party, at its 2012 party congress.Footnote19 Following the 2013 post-coup suppression of Ikhwan in Egypt, Erdoğan showed his solidarity for the victims with the then popularized four-finger Rabaa salute. These existing ties later made available to the AKP some of the resources of the Ikhwan.

However, one should not overlook the bumpy trajectory of the AKP-Ikhwan relationship. In retrospect, the Ikhwan’s leaders initially did not welcome the foundation of AKP as a split-away from the National Outlook. This formation was reminiscent of Ikhwan’s own experience when some of its defectors founded the Wasat Party in 1996 and divided the movement. Moreover, in its early years, the AKP was constantly reassuring outside observers of its commitment to secularism and maintaining good relations with Israel. Obviously, such developments ran counter to Ikhwan’s founding ideology, and its leaders did not accept the AKP as Islamist, but secular.Footnote20 Finally, having learned its lesson from the fate of the National Outlook parties, which were shut down by the Constitutional Court for being a hub for anti-secular activities, AKP leaders worked hard to persuade the state elite of the absence of a hidden Islamist agenda, and acted cautiously to avoid overtly close relations with other Islamist actors at home and abroad.

The Arab Uprisings, however, marked a new phase in bilateral relations. Unlike former portrayals of the AKP as a splinter movement embracing Western secularism, Ikhwan began, at least strategically, using the popular “Turkish Model” discourse for its own political legitimation against the widespread charges of terrorism. By framing the AKP as a successful fusion of Islam and democracy, Ikhwan could now position itself as a rightful actor in the pursuit of a similar, viable, pro-Western project in Egypt. This was not an unrequited love, as Turkey, being an aspiring middle power, also wanted to get the best out of the turmoil in the region. While the 2013 coup moved Ikhwan much closer to Turkey, the rapprochement was replaced gradually by an embedded relationship, in which Ikhwan’s prospects became increasingly tied to the AKP. After years of unceasing domestic and transnational repression, the Ikhwan weakened considerably in both organizational and financial terms, becoming a diaspora movement in exile with internal schisms. Although the divide over the leadership continues between Ibrahim Mounir’s camp in London and Mahmoud Hussein’s camp in Istanbul, Istanbul has become the new hub, hosting Ikhwan’s several foundations, organizations, and TV channels.Footnote21 In April 2016, Ikhwan leaders from all over the world gathered in Istanbul for an event titled “Thank you, Turkey,” declaring their gratitude and allegiance to the Turkish leader as the only hope for the Islamic Ummah.Footnote22

While support for Ikhwan abroad did not start with Erdoğan and had precedence in Kemalist Turkey,Footnote23 Erdoğan intensified Turkey’s relations with Ikhwan not at the peak of its pan-Islamist vision but when he leaned more towards a nationalist foreign policy discourse. In an iconic twist, following the failure in 2015 of the Kurdish resolution process, the reference point of the Rabaa salute changed from support for Ikhwan to the AKP’s new nationalist dictum of “one homeland; one state; one flag; one nation.” Nevertheless, the recent militarized foreign policy behavior, to which Ikhwan is attached, is not merely an AKP phenomenon, but rests on a consensus within the state bureaucracy on several fronts. Turkey’s incursion to Libya, for instance, was not mainly motivated by an Islamist urge to support the Ikhwan affiliates in a civil war but related to its power calculations to counterbalance other countries in the Eastern Mediterranean dispute through the well-supported Eurasianist “Blue Homeland” project.Footnote24

The question of the AKP’s Ikhwan-based foreign policy expectably puts Turkey at the center and yet largely poses the diverse Ikhwan branches as passive recipients of Turkey’s foreign policy decisions. When Morsi himself came to power in 2012, his regional leadership aspirations were harshly limited by material capabilities, and Egyptian foreign policy did not change much except for a few symbolic moves, like his visit to Tehran the same year. Besides forging strong relations with revolution supporters, Morsi adopted a non-confrontational approach towards Egypt’s traditional allies, signaling no drastic foreign policy change at both the regional and global levels.Footnote25 Moreover, Turkey’s relations with diverse Ikhwan branches have taken different trajectories depending on the balances of power. Unlike the Egyptian Ikhwan, which was bound to Turkey’s favors, the Yemeni front has a more transactional relationship with Turkey, shifting according to the involvement of other actors, such as Saudi Arabia and Iran. Especially since its 2015 launch of Operation Decisive Storm, Saudi Arabia has backed the Ikhwan-affiliated al-Islah Party in Yemen despite leading, at a broader regional level, the anti-Ikhwan campaign. Likewise, al-Islah seeks to keep its relations with Saudi Arabia safe in recognition of the latter’s political, military, and economic clout in Yemen.Footnote26 Ennahda in Tunisia remains at a cautious distance from Erdoğan, who, in contrast with his harsh reaction to the 2013 military intervention in Egypt, sufficed with a single statement calling the 2021 dismissal of the Tunisian government a “coup.”Footnote27 Overall, such diversity cannot be attributed to the primacy of a single ideological constant. Taking into account these phenomena, this paper adopts neoclassical realism to explain how Turkey’s Middle East policy has been shaped by the global and regional dynamics.

Systemic and sub-systemic factors

When the collapse of the Soviet Union transformed the Cold War’s bipolar international system into a unipolar one, the new structure led some scholars to claim US hegemonic exceptionalism in the absence of any balancing against the preponderant material capabilities of the US in the international distribution of power.Footnote28 For pessimists, however, the unipolar system was just a temporary phase until a new multipolar system would emerge due to the inevitable pattern of hegemonic failure.Footnote29 In fact, American decline has been a recurring narrative in academic debates since the 1950s. Yet, in its last wave, scholars citing the Great Recession (2007-2009) observe the power of the US shrinking in the face of rising challengersFootnote30, a transformation producing a shift towards a nascent multipolar order. Even Francis Fukuyama, who once claimed the end of history, argued in 2021 for the end of the American era, with its peak period lasting less than twenty years from the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession.Footnote31 Of course, the US still maintains a preeminence in multiple metrics of material capabilities. However, the Great Recession and the subsequent Eurozone Crisis not only underlined the shift of wealth and power from the (Transatlantic) West to the (Indo-Pacific) East but also raised doubts about the economic and financial robustness of US primacy. This marked the emergence of a de-centered “post-western world,”Footnote32 in which the US ceased its commitment to defend the liberal international order and non-western authoritarian powers such as China and Russia emerged as alternative models of development.

The fading unipolar moment and the US’s retrenchment played out most evidently in its withdrawal of overseas military deployments. Since the 1991 Gulf War, the US has had a strong direct military presence in the Middle East, with more than 200,000 troops stationed in the region (mostly in Iraq) in the early 2000s and cemented its position as the chief guarantor of the regional security order.Footnote33 However, with the economic crisis constraining the interventionist impulse and growing fatigue with inconclusive military interventions, successive US administrations under Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden have sought to devote fewer resources to and diminish the US troop presence in active conflict zones such as Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan. The US cut down its military presence in part by a retreat to offshore balancing, e.g. reluctantly leading from behind during the Syrian war, or, even, as in the case of Afghanistan, a direct withdrawal of US troops.Footnote34 The feasibility of this “right-sizing” policy is open to debate. However, the Middle East has been increasingly de-prioritized and replaced by a pivot toward Asia-Pacific to counter China’s rise. As shown by the lack of retaliation against Iran, which was widely blamed for the attacks on Saudi oil facilities at Abqaiq and Khurais in 2019, the US did not want to be entrapped by the regional conflicts any longer. This also relates to energy issues—a prime motive behind US Middle East policy. Whereas the US’s annual energy imports incrementally increased since the 1950s, reaching a record high in 2005, the numbers have decreased since then, making the country a net total energy exporter in 2019 for the first time since 1952 and signaling much less dependence on the Gulf energy supplies.Footnote35

At the sub-systemic level, the post-Arab Uprisings geopolitical turmoil, combined with multiple cases of state failures and conflict, has multiplied the impact of the US’s perceived disengagement. In the absence of a regional hegemon, Washington’s retreat from where it had previously overextended itself has created a perception of a power vacuum, stimulating two foreign policy behaviors in the Middle East: power maximization and balancing.

Strategic autonomy as power maximization

The perceived void left by the US withdrawal encouraged multiple regional actors to take a maximalist approach in pursuit of greater “strategic autonomy.”Footnote36 Unlike “restrictive strategic environments” that entail greater systemic impediments to a state’s use of material power to achieve its interests, “permissive strategic environments,” as in the case of Middle Eastern politics under a waning unipolar system, provide states with a broader range of strategies to respond to potential threats and opportunities.Footnote37 Besides international players like Russia, opportunistically keen to fill the power vacuum, several ambitious aspirants in the region, such as Turkey, Iran, and the UAE, adopted power-maximizing behaviors under less systemic imperatives in an effort to move up the regional and global hierarchy.

If grand strategy is broadly defined as the organizing principle informing a state's relations with the outside world, the Turkish case represents a recent slide from integrationist revisionism to autonomous expansionism, both aiming to revise the existing regional order (see ).Footnote38 Previously, the rigid bipolar international system of the Cold War era pushed Turkey to align itself with the Western bloc in order to counterbalance potential Soviet aggression. Throughout this period, Turkish foreign policy was anchored in its traditional Western orientation and geopolitical position as the southern bastion of NATO. The advent of a unipolar system at the end of the Cold War altered Turkey’s grand strategy from calculated pacifism to regional activism, adding new regional components to its foreign policy and redefining its position with multiple identities and historical assets.Footnote39 After the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, Turkey found systemic incentive for more active involvement in the Middle East as well, and projected itself as a functioning Muslim democracy with a pro-Western orientation that could serve as an anchor for a new Middle East with Western-friendly democratic governments—known as the US’s Greater Middle East Initiative. This revisionist policy meant improving cultural and economic ties to other countries and enhancing mediator and facilitator roles in regional conflicts. In fact, the AKP government opposed the motion allowing US troops to use Turkey’s military bases and facilities in Iraq’s 2003 invasion. Moreover, it also established contacts with Hamas, which was listed as a terror organization by the US and European Union (EU) but won the 2006 legislative election in the Palestinian territories. In general, however, the AKP thrived on a multidimensional and proactive foreign policy, mostly overlapping the national interests with those of the US and the EU.

Table 1. The systemic and sub-systemic dynamics shaping Turkey’s Middle East Policy

In the permissive environment of the post-unipolar global system, Turkey, like other rising powers as potential gravity centers of the global economy and political order, has increasingly aimed to carve out more space and autonomy in the pursuit of raising its global and regional profile.Footnote40 At the sub-systemic level, Turkey reoriented its foreign policy to respond to the dramatic political transformations in its immediate neighborhood. It pursued a maximalist, regional-hegemony-seeking behavior with the calculation that the authoritarian regimes in the region would sooner or later crumble through the Arab Uprisings, paving the way for the rise of Ikhwan offshoots across the region. With the same discursive claim of reinvigorating Pax Ottomana, the integrationist approach of the early years of AKP rule has been replaced by a more autonomous, interventionist policy with a more hawkish tone after the siege of Kobani in 2015 and, more pronouncedly, the 2016 abortive coup.Footnote41 Turkey has pursued assertive, bellicose, and largely unilateral involvements such as oil and gas drilling in the Eastern Mediterranean basin or preemptive cross-border military operations in Northern Iraq and Syria.Footnote42 It competed with other powers such as the UAE and Saudi Arabia for regional leverage, particularly through its involvement in the Libyan conflict, but also extended its direct presence from the Eastern Mediterranean basin to the Horn of Africa.

Balancing as security maximization

Another consequence born of perceived US apathy has been the new pattern of alliances. While the hegemon was extricating itself from the conflict-ridden region, the growing security challenges led to a latent-anarchic, self-help system in which security and survival were at stake. The Middle East, already marked by long-standing internal clashes, has heated up with the constant proliferation of threats under the increasing permeability of borders and power rivalries. In a volatile region, states have used different foreign policy tools, such as balancing, strategic hedging, and bandwagoning, as part of a strategy that includes both conflict and cooperation.Footnote43 As power is more diffused and fragmented among a wider range of competing state and non-state actors, the security concerns primarily lead to new pacts and alliances.

Although neither Russia nor China can match the US presence in the Middle East, regional powers have tended to cooperate with non-Western powers in the post-unipolar world. The systemic incentives and constraints have led to a series of back and forth plays in Turkish foreign policy,Footnote44 with the power-maximizing behavior accompanied by a balancing strategy. As Turkey and the US gradually lost their shared strategic outlook in multiple regional conflicts, Ankara played a delicate balancing game between major powers to increase its room to maneuver and pursue its own interests. The AKP sought to forge greater military and economic cooperation with Russia and China by declaring its intention to join the Shanghai Cooperation Organization or, more recently, via the 2019 Asia Anew Initiative.Footnote45 Yet, Turkey’s politics of aggregate balance via rapprochement with Russia went only so far, as they have divergent interests in the Middle East, and Russia imposed geographic limits on Turkey’s zone of influence, especially in Syria, via its 2016–2017 Operation Euphrates Shield and the 2020 Idlib offensive.Footnote46

The more consistent pattern has been the emergence of new alliances. Israel aside, three competing axes have been confronting each other from Morocco to Afghanistan. The divide between the Iranian-led Axis of Resistance and the Saudi-led Sunni Arab bloc has a long history; however, the more recent rift within the Sunni bloc dates back to the Arab Uprisings. Alarmed by the contagious revolutionary fervor and the rise of Ikhwan affiliates throughout the region, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt—known as the Arab Quartet—designated Ikhwan as a terrorist organization and worked together to contain the “democratic threat” and re-establish the status quo ante. In contrast, Turkey and Qatar, which did not feel threatened by the Ikhwan’s rise, have harbored and supported the movement on multiple fronts in order to establish a new regional order with Ikhwan-led governments in power. Despite their divergent visions, both alliances could maintain cordial relations through the mid-2010s and cooperate in cases such as Syria or Yemen. However, following the 2017 Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Crisis, in which Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, and Bahrain severed diplomatic ties with Qatar due to its support for Ikhwan, Turkey backed Qatar, deploying troops and supplies to the country. The murder of Saudi dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018 at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul (allegedly by the security aides to Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman) deteriorated bilateral relations further. A Cold-War-like rivalry between the alliances with several proxy confrontations on multiple fronts, such as Syria and Libya, has reached a stalemate, putting the regional security order under a lot of strain and consuming the political and economic resources of all involved parties.

The countries of the Middle East, consumed by this intra-regional zero-sum competition, found an incentive to keep tensions low in the face of rising security challenges and the US’s waning role as a security guarantor to its allies. The 2020 Abraham Accords to normalize relations between Israel and several Arab states and the 2021 re-entry negotiations to revive the Joint Comprehensive Plan for Action, marking a softer stance on Iran, also triggered diplomatic de-escalation in the region.Footnote47 Having realized the limitations of its expansionist foreign policy, most notably in Syria as the most calamitous example, the AKP government, too, has worked since 2020 to recalibrate its foreign policy and made more pronounced overtures for rapprochement with countries in the region. While initially condemning the Abraham Accords, Turkey gradually expressed an understanding, eventually leading to Israel’s President Isaac Herzog’s official visit to Turkey in 2022 – the highest-level visit in 14 years. Reflecting the new wind of rapprochement, the GCC Crisis was resolved at its 2021 summit in al-Ula, ending the dispute with Qatar, and this was followed by some fence-mending between the Arab Quartet and Turkey, such as Erdoğan’s visits to Abu Dhabi and Riyadh.Footnote48 Likewise, in April 2022, a Turkish court ruled to stop the trial of 26 Saudis accused in the Khashoggi killing and to transfer the case to Saudi Arabia. Overall, uncertainty exists as to whether political leaders of the region are simply seizing the moment or whether this de-escalation heralds a new era despite the continuation of hot conflicts.

Ikhwan’s role in Turkey’s power projection

The AKP’s calculation was that the Arab Spring would be the Ikhwan Spring in practice, and AKP’s stance as the advocate of the Arab street against the crumbling authoritarian regimes was in line with its broader agenda of democratic transition in the region. Initially, Western powers also supported the revolutions.Footnote49 The global dynamics that once favored the rise of the AKP would now promote the AKP model of political governance throughout the region. The new Middle East with Turkey-allied Sunni governments would then usher in a new era in the AKP’s own projection. The sudden surge in Arab streets required swift action. To export its model and transfer its know-how, the AKP government financially subsidized the Ikhwan-affiliated political parties and organized workshops in 2011 and 2013 to train the Arab Islamists in political campaigning and party formation.Footnote50 It convinced the Egyptian Ikhwan to run a candidate for president in 2012, although the movement had previously pledged not to do so.Footnote51 Turkey gave the movement “geographical depth” via its material capabilities, and Qatar offered “rhetorical breadth” via its media and intellectual organizations.Footnote52

In this cost–benefit analysis, Turkey, unlike the Gulf monarchies, had little to fear regarding the security of its regime due to its support for Ikhwan. Both Qatar and Turkey felt immune to an Ikhwan-led uprising. Quite the contrary, such a proxy power minimizes Ankara’s strategic costs, such as the legal consequences of its foreign operations and potential human and material losses. Working with local actors instead of crude interventions could also be used to legitimize Turkish involvement in the broader region. For Turkey and Qatar, Ikhwan provided a wieldy political identity with which local populations could identify.

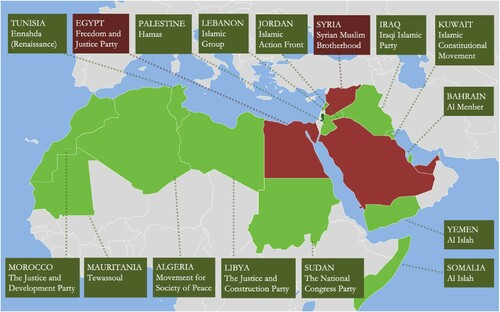

In the aftermath of the Arab Uprisings, aspirants such as Iran and Saudi Arabia employed their already-existing transnational networks and proxies for their divergent templates for regional order, e.g. the Shia organizations like Hezbollah and Salafi Islamist groups, respectively. This power competition operated in a setting where transnational non-state actors such as the Kurdish armed forces and Salafi jihadis were challenging nation-state borders. In security terms, the post-2011 alliances are marked by the rise of armed non-state actors as proxies for regional powers.Footnote53 With similar regional-hegemony-seeking behavior yet lacking the political infrastructure to do so, Turkey aimed to alter the regional distribution of relative material capabilities by first targeting the low hanging fruits and activated its links to Ikhwan offshoots across the Middle East and North Africa. Though not hierarchically interconnected, the movement possessed strong grassroots organizations across the region. As seen in , Ikhwan-affiliated political parties operated in several countries, including Algeria, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, Morocco, Sudan, Tunisia, and Yemen.

Figure 1. Ikhwan-affiliated political parties. Source: Author’s illustration.

Note: Countries in a dark red shade have designated the Ikhwan as a terrorist organization.

Enabled by these linkages, Erdoğan embarked upon a wholesale region-building process with a new imagination for the Middle East. For instance, he suddenly brought up the Köroğlu Turks in Libya, whom the Turkish public had never heard of before but came into the picture during Ankara’s cooperation with the Ikhwan-affiliated Government of National Accord (GNA), stating: “In Libya, there are Köroğlu Turks remaining from the Ottomans […] and they are being subjected to ethnic cleansing. Haftar is bent on destroying them, too. As is the case across North Africa, in Libya, too, one of our main duties is to protect the grandchildren of our ancestors.”Footnote54 In 2017, the Sudanese island of Suakin popped up in the Turkish news as a former Ottoman port, one that Erdoğan hoped to use as a military base to impose Turkish prerogatives in the Horn of Africa. As such, the AKP’s reimagination of the region, or Pax Ottomana, rests on the present network and strength of Ikhwan offshoots rather than a deeper shared history. This network has enabled Ankara to project its influence in areas where doing so used to be unthinkable until recently. Besides such political leverage, the Ikhwan identity also offered a religious legitimation to Turkish interventionism. Notably, Turkish support for Hamas outbid Arab leaders in the Palestinian cause, which resonated most among the Arab populations.

Initially things were lining up and the fortunes seemed to rise for Ikhwan in Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, and Somalia. AKP aggressively supported the reconstruction of these countries to export the “Turkish model.” Mohamed Morsi’s victory in Egypt’s 2012 presidential elections and Ennahda leading Tunisia’s transitional government after 2011 marked the zenith of this project. Turkey also supported the Ikhwan-affiliated JCP in Libya and pushed Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to legalize the Syrian Ikhwan and hold free elections.Footnote55 While diplomatic channels failed and the rising star of Ikhwan faded, most notably with the 2013 military intervention that ousted Morsi, Ankara did not hesitate in flexing its muscles to confront major setbacks on multiple fronts and adopted a proxy warfare strategy by making use of Ikhwan networks. In Syria, for instance, Turkey backed Faylaq al-Sham, an Ikhwan-affiliated armed group, which, together with Ahrar al Sham, joined the Turkish army’s 2016 Operation Euphrates Shield. In order to restructure and unify nationalist Islamist armed groups in Idlib, Turkey also supported the National Front for Liberation in 2018, which was led by Ikhwan-affiliated groups, political Salafists, and nationalists.Footnote56 In Libya, Turkey assumed the command of militias in Tripoli that were aligned with the GNA and empowered them with Syrian mercenaries. Reinforcing this proxy architecture, Istanbul has increasingly become a transnational center of Ikhwan activities, such as hosting the intra-party elections of Yemeni al Islah and the formation of the Syrian National Council which included the exiled Ikhwan members.

Because Turkish foreign policy is so tied to Ikhwan offshoots, the AKP elite saw the coups overthrowing Ikhwan in Egypt (2013) and Sudan (2019) as a direct attempt to reduce Turkish influence.Footnote57 Deep ties make it more difficult to use Ikhwan as a bargaining chip to normalize relations with the new governments. Nevertheless, when responding to the sub-systemic stimuli, the Turkish government did not hesitate to make concessions and diminish its support for these groups. Turkey’s Ikhwan links within its overstretched foreign policy have increasingly become a liability. To mend the fences with the Arab Quartet and show its good will in that regard, the Turkish authorities, for instance, asked the Ikhwan’s Istanbul-based TV channels in 2021 to tone down their criticisms of Egypt’s military-dominated government. Due to the continuing pressure, several critical Arab reporters left Istanbul and Ikhwan’s most popular satellite channel, Mekameleen, shut down its Turkey offices in March 2022.Footnote58 Especially in the case of the relations with Egypt, the extradition of prominent Ikhwan figures is an open question and Turkey denies allegations against them. However, the current rapprochement has concerned many Ikhwan exiles and pushed them to consider moving to another country such as Malaysia.

One of the reasons that facilitated the Quartet’s initiative to normalize relations and Turkey’s to soften its pro-Ikhwan stance is the movement’s much weakened position. The Ikhwan-affiliated governments fell one by one, from Egypt to Sudan to Tunisia, and the movement overall faced catastrophic setbacks with the authoritarian backlash to the Arab Uprisings. It has also been wracked by internal frictions, reflected in the two camps that have emerged in London and Istanbul. The Ikhwan ran out of steam in general and its potential power as a threat to the regime security of the Gulf countries has waned immensely. For the very same reason, Ikhwan seems to have lost the value Erdoğan once saw in it. Ankara has showed its willingness to curb some activities and voices of Ikhwan. While the considerable use of Ikhwan links as a proxy power in foreign policy and as a discursive asset in domestic politics still makes it difficult to cut off links entirely, Turkey’s recent track record and the current regional rapprochement, widely expected to take place only in the post-Erdoğan era, indicate that relations with Ikhwan did not primarily evolve out of Islamist convictions.

Unit-Level variables

Systemic incentives and constraints explain longer trends, but divergence in foreign policy responses to the same systemic stimuli often hinge on the domestic processes “as transmission belts that channel, mediate and (re)direct policy outputs in response to external forces (primarily changes in relative power).”Footnote59 Especially, in permissive settings, such unit-level factors may have a greater influence on the process of foreign policy making and implementation. This holds true for Turkey’s relations with the Middle East and Ikhwan in the last decade as well.

In neoclassical realist theory, strategic assessment of the geopolitical structure of the international and regional systems can be heavily affected by the personality, core values, beliefs, and ideas of the foreign policy executive. As Kitchen argues in his analysis of the unit-level impact of ideas as an intervening variable, uncertainty about threats and opportunities, derived from imperfect intelligence, may also create a void to be filled by ideas and beliefs.Footnote60 When interpreting the Arab Uprisings as a historic moment for its foreign policy ambitions, AKP leaders overestimated not only Turkey’s material capabilities in comparison to those of other regional forces, but also the Ikhwan’s fortunes. In addition to Erdoğan being prone to risk-taking, the potential transformative power attributed to Ikhwan in the aftermath of the Arab Uprisings steered Turkey’s foreign policy in a particular direction under the aforementioned permissive systemic conditions. Regarding the cognitive filters processing systemic signals and threat perceptions, Erdoğan also internalized regional developments and saw Ikhwan and himself as having an overlapping fate under the threat of Western powers and the Saudi-UAE alliance. The ousting of Morsi coincided with the massive, anti-government 2013 Gezi Protests, which Erdoğan claimed were driven by dark, outside forces in an attempt to bring him down. “Those, who dream that I will end up like Adnan Menderes (Turkish Prime Minister ousted from power in 1960 and later executed) and Morsi, hear me! This journey will not be left unfinished. There are millions of Anatolian people who will shoulder the new Turkey ideal,” Erdoğan stated.Footnote61 This perceived vulnerability pushed him harder to build the strength needed to defuse internal and external threats as much as systemic conditions would permit doing so. Another element of grand strategy formulation is the selection of means to address systemic stimuli. This brings questions of “what means are available, which will work most effectively, and whether their use can be justified.”Footnote62 Here, ideological affinity ensured the availability of resources as the AKP used its old links with Ikhwan branches. This move was also “justified” by the AKP’s Islamist foreign policy discourse, which not only provided the shared ground to work together in multiple regional conflicts but also raised the party’s profile at home as the protector of the ummah.

One should also note that not all the unit-level variables are ideational. Turkey’s institutional structure has functioned as a moderating variable in the AKP’s Middle East policy. While states consist of diverse, competing actors, the centralization and personalization of political power in contemporary Turkey eliminated the traditional veto players and the systems of checks and balances, further fast-tracking foreign policy making and implementation. The process reached its zenith with the 2018 transition to the presidential system.Footnote63 Another moderating variable conditioning the state’s ability to respond adequately to external pressures and opportunities, is state-society relations. While the AKP elite is able to harness the country’s power potential in general, social and elite cohesion to support foreign policy objectives defines the level of responsiveness. In this regard, the ruling alliance between the AKP and the ultranationalist Nationalist Action Party, as well as the presence of several Eurasianist groups in the state bureaucracy, affected the scope of Turkish interventionism in the region in line with a populist expansionist rhetoric. Finally, transborder military operations can stimulate a “rally around the flag” effect, increasing public support for government policies at least in the short run,Footnote64 and act as a diversionary effect in times of successive economic crises, which have only been exacerbated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Considering the sagging approval ratings for his presidency and the Turkish economy wracked with high inflation, Erdoğan sought success abroad. Besides systemic stimuli, domestic challenges and the desperate need for Gulf capital further motivated him to repair the fractured relations with Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

Conclusion

The AKP’s Middle East policy, widely considered as foreign policy adventurism, represents more than a passing twist, but a deeper change in Turkey’s foreign policy orientation. Despite its domestic use for the authoritarian practices, the AKP’s pursuit of strategic autonomy reflects a grand strategy to respond to the shifts in the balance of power in the post-unipolar world. The AKP’s ideological ties to the Ikhwan made available new resources and opportunities and helped legitimize its foreign policy activism, particularly among its conservative base. However, the AKP approached Ikhwan as part of its power-maximizing strategy because it offered the greatest benefit (as the most organized group in the region) at the lowest cost (posing no threat to its own regime security). When regional conditions changed, the AKP was willing to downplay its Ikhwan card as well. The domestic ideational, institutional, and social factors mediating systemic and sub-systemic stimuli have affected the scope and pace of AKP’s relations with the Ikhwan within its broader Middle East policy.

Amidst theoretical quarrels about the overriding importance of material or ideational factors, a neoclassical realist approach suggests a holistic perspective in which systemic imperatives explain a state’s strategic orientation and unit-level variables account for the variance in concrete foreign policy choices. As a remedy to the disconnect between the International Relations of the Middle East and Foreign Policy Analysis, it provides a systemized, generalizable, outside-in approach that is also attuned to factors of domestic politics. Yet, neoclassical realism still maintains a state-centric approach to foreign policy analysis. A more complete approach requires the incorporation of non-state actors in order to grasp proxy power politics and transnational governance in the Middle East. While this study on the AKP’s entanglement with the Ikhwan’s offshoots as a force multiplier can provide an entry point, future studies need to take into account the interests, incentives, and constraints various non-state actors face.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hakkı Taş

Hakkı Taş is a Research Fellow at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg. His research interests include populism, political Islam, and identity politics, with a special focus on Turkey and Egypt. His articles have appeared in numerous journals including Comparative Studies in Society and History, Third World Quarterly, PS: Political Science and Politics, and the British Journal of Politics and International Relations. His research has been funded by several institutions, including the Swedish Institute, Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, and Gerda Henkel Foundation.

Notes

1 Ramadan, “Democratic Turkey.”

2 Berman, “Islamist Mobilization.”

3 Yavuz, “The Motives.”

4 Başkan and Taşpınar, The Nation or the Ummah, 9.

5 Cagaptay, Erdogan’s Empire, 133.

6 Duvar English, “CHP leader.”

7 For a recent overview of Turkish foreign policy, see Aydın, “Grand Strategizing”; Dalacoura, “Turkish foreign policy”; Şahin, “Theorizing the Change”; and Siri et al., “Turkey as a regional security actor.”

8 Ripsman et al, Neoclassical Realist Theory, and Schweller, “Unanswered Threats.”

9 Aydın, “Grand Strategizing”; Kutlay and Öniş, “Turkish foreign policy”; Ovalı and Özdikmenli, “Ideologies and the Western Question”; and Şahin, “Theorizing the Change”.

10 Han, “Paradise Lost”; Kardaş, “Revisionism and Resecuritization”; Yeşilyurt, “Explaining Miscalculation and Maladaptation”; and Yilmaz, “A Government Devoid.”

11 Hintz, Identity Politics.

12 Aydıntaşbaş and Bianco, “Useful Enemies.”

13 Swinkels, “How Ideas Matter.”

14 Kitchen, “Systemic pressures,” 118.

15 Mashino, “The Bipolar Conflict.”

16 Yüksel and Tekineş, “Turkey’s love-in.”

17 Taş, “The Formulation and Implementation.”

18 T24, “Çandar.”

19 Gurpinar, “Turkey and the Muslim Brotherhood,” 24–28.

20 Ayyash, “The Turkish Future.”

21 Yavuz, “Erdoğan’s Soft Power Arm.”

22 Taş, “AKP and the Muslim Brotherhood.”

23 Özkan, “Relations between Turkey and Syria.”

24 Taş, “The Formulation and Implementation.”

25 Fouad, Missing Influence, 35.

26 Al-Sofari, “An Exceptional Case.”

27 Yaşar and Aksoy, “Making Sense.”

28 Wohlforth, “The Stability.”

29 Layne, “This Time,” 204.

30 Nye, “The rise.”

31 Fukuyama, “Francis Fukuyama.”

32 Stuenkel, Post-western World.

33 Barnes-Dacey and Lovatt, Principled Pragmatism, 4.

34 Hinnebusch, “The Arab Uprisings,” 16.

35 Barnes-Dacey and Lovat, Principled Pragmatism, 6.

36 Kutlay and Öniş, “Turkish foreign policy.”

37 Ripsman et al, Neoclassical Realist Theory, 52–56.

38 Ibid., 84.

39 For a historical account of Turkey’s grand strategies, see Aydın, “Grand Strategizing.”

40 Kanat, “Theorizing the Transformation,” 71.

41 Yeşilyurt, “Explaining Miscalculation,” 79–80.

42 The latter required tacit US approval.

43 El-Dessouki and Mansour, “Small states.”

44 Dalacoura, “Turkish foreign policy.”

45 Taş, “The Formulation and Implementation,” 17.

46 Şahin, “Theorizing the Change,” and Kubicek, “Structural dynamics.”

47 Jabbour, After a Divorce, 12.

48 Mashino, “The Bipolar Conflict,” 4.

49 Kardaş, “Revisionism and Resecuritization,” 494.

50 Jabbour, After a Divorce, 9.

51 Çevik, “Erdogan’s Endgame.”

52 Cinkara, “Interpreting Turkey.”

53 Darwich, “Foreign Policy Analysis.”

54 International Crisis Group, “The View,” 3.

55 Yeşilyurt, “Explaining Miscalculation,” 72.

56 Yüksel, “Turkey’s approach,” 142.

57 Aydıntaşbaş and Bianco, “Useful Enemies.”

58 Taş, “AKP and the Muslim Brotherhood.”

59 Schweller, “Unanswered Threats,” 164.

60 Kitchen, “Systemic pressures,” 134.

61 Erdoğan, “President.”

62 Kitchen, “Systemic pressures,” 135.

63 Taş, “The Formulation and Implementation.”

64 Siri et al, “Turkey as a regional security actor,” 14.

References

- Al-Sofari, Mutahar. “An Exceptional Case: Saudi Relations with Yemen’s Islah Party.” The Washington Institute Fikra Forum. July 26, 2021. Accessed March 2, 2022. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/exceptional-case-saudi-relations-yemens-islah-party.

- Aydın, Mustafa. “Grand Strategizing in and for Turkish Foreign Policy: Lessons Learned from History, Geography and Practice.” Perceptions 25 (2021): 203–226.

- Aydıntaşbaş, Aslı, and Cinzia Bianco. “Useful Enemies: How the Turkey-UAE Rivalry Is Remaking the Middle East.” ECFR Policy Brief 380 (2021): 1–22.

- Ayyash, Abdelrahman. “The Turkish Future of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood.” The Century Foundation, August 17, 2020. Accessed September 1, 2021. https://tcf.org/content/report/turkish-future-egypts-muslim-brotherhood/?agreed=1&agreed=1.

- Barnes-Dacey, Julien, and Hugh Lovatt. Principled Pragmatism: Europe’s Place in a Multipolar Middle East. Berlin: ECFR, 2022.

- Başkan, Birol, and Ömer Taşpınar. The Nation or the Ummah – Islamism and Turkish Foreign Policy. Albany NY: SUNY Press, 2021.

- Berman, Chantal. “Islamist Mobilization during the Arab Uprisings.” In The Oxford Handbook of Politics in Muslim Societies, edited by Melani Cammett and Pauline Jones, January 2021. Accessed September 1, 2021. https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190931056.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780190931056-e-43.

- Cagaptay, Soner. Erdogan’s Empire: Turkey and the Politics of the Middle East. London: I.B. Tauris, 2020.

- Çevik, Salim. “Erdogan’s Endgame with Egypt.” The Cairo Review of Global Affairs, August 6, 2021. Accessed 3 March 2022. https://www.thecairoreview.com/global-forum/erdogans-endgame-with-egypt/.

- Cinkara, Gokhan. “Interpreting Turkey’s Current Diplomatic Rapproachement Toward the Gulf.” The Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington. March 22, 2022. Accessed April 1, 2022. https://agsiw.org/interpreting-turkeys-current-diplomatic-rapprochement-toward-the-gulf/.

- Dalacoura, Katerina. “Turkish Foreign Policy in the Middle East: Power Projection and Post-Ideological Politics.” International Affairs 97, no. 4 (2021): 1125–1142.

- Darwich, May. “Foreign Policy Analysis and Armed Non-State Actors in World Politics: Lessons from the Middle East.” Foreign Policy Analysis 17, no. 4 (2021): 1–11.

- Duvar English. “CHP leader questions Erdoğan's mental wellbeing yet again.” October 10, 2021. Accessed November 7, 2021. https://www.duvarenglish.com/chp-leader-questions-erdogans-mental-wellbeing-yet-again-news-59138., 2021.

- El-Dessouki, Ayman, and Ola Rafik Mansour. “Small States and Strategic Hedging: The United Arab Emirates’ Policy Towards Iran.” Review of Economics and Political Science (2020): 1–14. DOI:10.1108/REPS-09-2019-0124.

- Erdoğan, Tayyip. “President Erdoğan Meets Representatives of NGOs in Kayseri.” TCCB, May 17, 2015. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://www.tccb.gov.tr/en/news/542/32391/cumhurbaskani-erdoganin-samsun-programi.

- Fouad, Khaled. Missing Influence – How MB Administers its Foreign Relations. Cairo: Political Stimulus, 2022.

- Fukuyama, Francis. Francis Fukuyama on the end of American hegemony.” The Economist. November 8, 2021.

- Gurpinar, Bulut. “Turkey and the Muslim Brotherhood: Crossing Roads in Syria.” Eurasian Journal of Social Sciences 3, no. 4 (2015): 22–36.

- Han, Ahmet K. “Paradise Lost: A Neoclassical Realist Analysis of Turkish Foreign Policy and the Case of Turkish-Syrian Relations.” In Turkey-Syria Relations: Between Enmity and Amity, edited by Raymond A. Hinnebusch, and Özlem Tür, 55–70. Surrey: Ashgate, 2013.

- Hinnebusch, Raymond. “Arap Ayaklanmaları ve Ortadoğu ve Kuzey Afrika Bölgesel Devletler Sistemi.” Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi 11, no. 42 (2014): 7–27.

- Hintz, Lisel. Identity Politics Inside Out: National Identity Contestation and Foreign Policy in Turkey. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Honghui, Pan. “Prospects for Sino-Turkish Relations.” China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies 02, no. 1 (2016): 101–117.

- International Crisis Group. “Turkey Wades Into Libya’s Troubled Waters.” Crisis Group Europe Report 257 (2020): 1–31. Brussels: ICG.

- Jabbour, Jana J, After a Divorce. a Frosty Entente: Turkey’s Rapprochement with the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. Strategic Necessity and Transactional Partnership in a Shifting World Order. Paris: IFRI, 2022.

- Kanat, Kılıç Buğra. “Theorizing the Transformation of Turkish Foreign Policy.” Insight Turkey 16, no. 1 (2014): 65–84.

- Kardaş, Şaban. “Revisionism and Resecuritization of Turkey’s Middle East Policy: A Neoclassical Realist Explanation.” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 23, no. 3 (2021): 490–501.

- Kitchen, Nicholas. “Systemic Pressures and Domestic Ideas: A Neoclassical Realist Model of Grand Strategy Formation.” Review of International Studies 36, no. 1 (2010): 117–143.

- Kubicek, Paul. “Structural Dynamics, Pragmatism, and Shared Grievances: Explaining Russian-Turkish Relations.” Turkish Studies 23, no. 5 (2022): 1–31. Forthcoming. doi:10.1080/14683849.2022.2060637

- Kutlay, Mustafa, and Ziya Öniş. “Turkish Foreign Policy in a Post-Western Order: Strategic Autonomy or new Forms of Dependence?” International Affairs 97, no. 4 (2021): 1085–1104.

- Layne, Christopher. “This Time It’s Real: The End of Unipolarity and the Pax Americana.” International Studies Quarterly 56 (2012): 203–213.

- Mashino, Ito. 2021 “The Bipolar Conflict in the Middle East over the Muslim Brotherhood.” Mitsui & Co. Monthly Report. June 15, 2021. Accessed September 2, 2021. https://www.mitsui.com/mgssi/en/report/staff/1228935_10746.html.

- Mutlu, Sefa. 2022 “Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan: Seçilmişlerin bulunduğu Meclis'in feshi Tunus halkının iradesine bir darbedir.” AA. April 4, 2022. Accessed April 10, 2022. https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/gundem/cumhurbaskani-erdogan-secilmislerin-bulundugu-meclisin-feshi-tunus-halkinin-iradesine-bir-darbedir/2555000.

- Nye, Joseph S. “The Rise and Fall of American Hegemony from Wilson to Trump.” International Affairs 95, no. 1 (2019): 63–80.

- Ovalı, Ali Şevket, and İlkim Özdikmenli. “Ideologies and the Western Question in Turkish Foreign Policy: A Neo-Classical Realist Perspective.” All Azimuth 9, no. 1 (2020): 105–126.

- Özkan, Behlül. “Relations Between Turkey and Syria in the 1980s and 1990s: Political Islam, Muslim Brotherhood and Intelligence Wars.” Uluslararası İlişkiler 16, no. 62 (2019): 5–25.

- Ramadan, Tariq. “Democratic Turkey Is the Template for Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood.” Huffington Post, February 8, 2011. Accessed September 2, 2021. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/post_1690_b_820366.

- Ripsman, Norrin, Jeffrey Taliaferro, and Steven Lobell. Neoclassical Realist Theory of International Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Şahin, Mehmet. “Theorizing the Change: A Neoclassical Realist Approach to Turkish Foreign Policy.” Contemporary Review of the Middle East 7, no. 4 (2020): 483–500.

- Schweller, Randall. “Unanswered Threats: A Neoclassical Realist Theory of Underbalancing.” International Security 29, no. 2 (2004): 159–201.

- Siri, Neset, et al. Turkey as a regional security actor in the Black Sea, the Mediterranean, and the Levant Region.” CMI Report 2. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute, 2021.

- Stuenkel, Oliver. Post-Western World: How Emerging Powers Are Remaking Global Order. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2016.

- Swinkels, Marij. “How Ideas Matter in Public Policy: A Review of Concepts, Mechanisms, and Methods.” International Review of Public Policy 2, no. 3 (2020): 281–316.

- T24. “Çandar: AK Parti, Müslüman Kardeşler’in bir şubesi niteliğinde.” October 9, 2014. Accessed September 5, 2021. https://t24.com.tr/haber/kobane-dustu-dusuyor-demek-dussun-demektir,273281.

- Taş, Hakkı. “AKP and the Muslim Brotherhood: Faithful Companions?,” Ahval. April 28, 2021. Accessed September 5, 2021. http://ahval.co/en-116743.

- Taş, Hakkı. “The Formulation and Implementation of Populist Foreign Policy: Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean.” Mediterranean Politics (2020): 1–25. DOI: 10.1080/13629395.2020.1833160.

- Wohlforth, William. “The Stability of a Unipolar World.” International Security 24, no. 1 (1999): 5–41.

- Yaşar, Nebahat Tanrıverdi, and Hürcan Aslı Aksoy. “Making Sense of Turkey’s Cautious Reaction to Power Shifts in Tunisia.” SWP Comment 52 (2021): 1–4. Accessed December 1, 2021. https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/comments/2021C52_TurkeyAndTunisia.pdf.

- Yavuz, M. Hakan. “Erdoğan’s Soft Power Arm: Mapping the Muslim Brotherhood’s Networks of Influence in Turkey.” Center for Research & Intercommunication Knowledge Special Report 187 (2020): 1–50. Accessed September 3, 2021. https://crik.sa/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Erdogans-Soft-Power-Arm.pdf.

- Yavuz, M. Hakan. “The Motives of Erdogan’s Foreign Policy: Neo-Ottomanism and Strategic Autonomy.” Turkish Studies 23, no. 5 (2022). forthcoming.

- Yeşilyurt, Nuri. “Explaining Miscalculation and Maladaptation in Turkish Foreign Policy Towards the Middle East During the Arab Uprisings: A Neoclassical Realist Perspective.” All Azimuth 6, no. 2 (2017): 65–83.

- Yilmaz, Samet. “A Government Devoid of Strong Leadership: A Neoclassical Realist Explanation of Turkey’s Iraq War Decision in 2003.” All Azimuth 10, no. 2 (2021): 197–212.

- Yüksel, Engin. “Turkey’s Approach to Proxy war in the Middle East and North Africa.” Security and Defence Quarterly 31, no. 4 (2020): 137–152.

- Yüksel, Engin, and Haşim Tekineş. “Turkey’s love-in with Qatar.” CRU Report (2021). Accessed September 4, 2021. https://www.clingendael.org/publication/turkeys-love-qatar-marriage-convenience.