ABSTRACT

The Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power in 2002 with the promise of reforms to further democratic consolidation in Turkey. At that time, the AKP represented a rainbow coalition of individuals from the previous Islamist parties and many liberal democrats who were fed up with the failures of old secular political parties. The Turkish public shared their frustrations and overwhelmingly supported the AKP. Unfortunately, these reforms did not last. Today, it is indisputable that under the rule of the AKP, and more specifically, President Recep T. Erdoğan, Turkey has become an authoritarian state defined and shaped by one person. This article explores what these developments mean for the future of Turkish democracy as the country celebrates its centenary, and it includes an examination of whether Turkish political culture is supportive of such changes.

Introduction

Turkey once stood as an example of democracy for countries in the Middle East and the Muslim world. It was a remarkable experiment in state-building from the ashes of an empire. However, on the eve of the Republic’s centenary, the Turkish political system cannot be characterized as a functioning democracy. Many of its shortcomings are ably described in other contributions to this Special Issue. As Turkey prepares for elections in 2023, it not only has to deal with the devastating consequences of the February 2023 earthquakes, but also uncertainties and controversies, including whether President Recep T. Erdoğan, who has announced his candidacy to be re-elected, is constitutionally eligible to serve a third term.Footnote1

When Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) came to power in 2002 with the promise of democratization and new leadership from self-proclaimed reformist successors of the Virtue Party (Fazilet Partisi), many students of Turkish politics welcomed it as a new beginning, perhaps a transformation in political Islam that promised democratic consolidation in Turkey. At that time, the AKP represented a rainbow coalition of reformist members of the previous Islamist parties, Kurdish voters, and some liberal democrats who were fed up with the old secular political parties and their intransigent policies. However, a few scholars, including this author, worried that these self-proclaimed reformist leaders of the AKP were nothing more than wolves in sheep’s clothing who were ready to take advantage of the economic and political crises of the country that followed the 2001 financial collapse. I maintained that the AKP had its own agenda of conquering the state from within, a long-held ambition of Islamist counter-revolutionaries in Turkey. In an early assessment of what the post-Virtue Party AKP might hold for Turkey, I concluded that if the self-claimed reformers truly intended to create a new political party like the Christian-Democratic parties in Western Europe, this would be a significant change toward the consolidation of democracy in Turkey. But, if they were to revert to the practices and goals of their old mentors, then the future of democracy would be at risk.Footnote2

One cannot deny that during its first term in power, AKP pushed ahead with reforms in pursuit of membership in the European Union (EU) and gradually broke the grip of the powerful Turkish military on politics. At that time, the AKP was a coalition of different leaders and groups which held varying ideological positions. One group was the self-proclaimed reformers of the former Welfare (Refah)and Virtue parties who left the old circle around Necmettin Erbakan, a stalwart of Islamist politics in Turkey. This group was led by Erdoğan, Abdullah Gül, Abdüllatif Şener, İdris Naim Şahin, Binali Yıldırım, and Bülent Arınç, and was supported by overwhelming majority of the Milli Görüş followers who had long been associated with Erbakan. The second group represented liberal and secular politicians, writers, and businessmen who were followers of former center-right political parties. Their main interest was to reform the economy and realize Turkey’s EU membership aspiration. The third main group included former secular leftists who had abandoned the rigid leftist ideologies of pre-1980 Turkey and looked for a new beginning. The elections of 2002 gave AKP a lopsided majority (two-thirds of the seats despite winning just over 34 percent of the vote) because only two political parties managed to clear the ten percent national elections threshold.

Following AKP’s 2002 victory, there were concern over whether Turkey would see a shift in its secular politics and orientation towards the Western world. Erdoğan repeatedly assured the public that the AKP did not find it appropriate to mix religion and politics and that it viewed itself as a party of conservative democrats rather than Islamists. Initially, there were signs of promise and progress. Political reforms in the early 2000s opened the door for EU accession talks in 2005. However, soon after, Erdoğan gradually began to eliminated his rivals within the AKP and reversed previous reforms through constitutional amendments coupled with nepotism and corruption, even as the party won several more victories at the polls. Today, it is indisputable that under the rule of the AKP, Turkey has become an authoritarian state with a political system defined and shaped by one man – Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Moreover, under Erdoğan's orders, the AKP has embarked on educational and social engineering programs aimed at Islamizing society with neo-Ottoman propaganda. These developments lead one to wonder what was the fundamental goal of Erdoğan when he declared Hedef 2023 (Vision 2023), a program designed to mark the country’s centenary.Footnote3 Some worry that the ultimate goal is replacement of Ataturk’s secular republic with an Islamic state characterized by a la Turca Presidentialism (neo-Sultanism) or a third attempt at Meşrutiyet (a constitutional monarchy)?Footnote4

This article seeks to examine how Erdoğan has succeeded in becoming the dominant force in Turkish politics and society and what his goals may be. It traces his rise and the AKP’s transformation, as well his various attempts to consolidate power. It also interrogates the behavior and inclinations of Turkish voters, focusing on the phenomenon of voter realignment and how extensive support is for a more authoritarian political direction. It concludes with some thoughts about Turkey’s political future.

The rise of political Islam: Erdoğan at the helm

How did Erdoğan transform Turkish politics into an authoritarian presidential system in which he has become the dominant figure? Three factors aided him and his team in consolidating their grip on power in Turkey. First was their gradual takeover of the networks of the Welfare and Virtue parties.Footnote5 Both were products of earlier Islamist political parties that entered the political scene at the beginning of the multi-party system. The second factor was the extensive coalition the party built with religious orders known as tarikat, including the powerful Fethullah Gülen Movement. Together, Erdoğan and Gülen, along with powerful tarikats, embarked on a strategy to achieve their common goal – to bring down the secular state by capturing its secular institutions from within. By the early 2010s, after they secured their hold on Turkey’s secular institutions, including the military, Erdoğan and Gülen went against each other to determine who would be in charge of shaping the future of the ‘new Turkey’. Finally, the AKP benefitted from voter realignment which occurred in the 1990s and the failure of traditional parties to adapt to this realignment.

From the Islamic Democracy Party to AKP: a story of alliances and resilience

To appreciate what the AKP means for political development in Turkey, one must first understand the role political parties play in democracies. Political parties provide a crucial link between the electorate and elites as well as between citizens and government in functioning democracies.Footnote6 Political parties fulfill several important tasks that include: (1) Organizing public participation in politics, (2) Control and recruitment of elites, (3) Conflict management, (4) Competition management, (5) Policy innovation, and most significantly, (6) Socializing the public to system consensus.Footnote7 It is in the context of parties’ role that one can understand the rise of the AKP.

When one looks at how Islamist political parties have worked in Turkey, one sees that they not only played a crucial role in the polarization of public opinion, but they also campaigned diligently to convince their followers that the current political system and its laïc (secular) nature were illegitimate. In this respect, the AKP and its predecessors did not socialize their followers toward system consensus. However, Erdoğan's AKP did successful adapted to changing political dynamics and voter realignment during the 1990s and early 2000s. One constant, however, for both the AKP and its predecessors was how they closely worked with religious leaders and tarikats to advances their political agenda.

Islamist political parties in Turkey have always had ties to powerful tarikats and their influential religious leaders, known as sheikhs. Those tarikats that ventured into politics had one common goal: to reverse Kemal Atatürk’s reforms and bring Islam back into the realm of politics. However, until the 1990s, these groups lacked the necessary economic and human capital base to challenge openly Turkey's laïcité and its staunch defenders. Given their lack of power, the tarikats adopted a powerful strategy that relied on patience, so that if every believer did their part, sometime in the future, Turkey would once again become an Islamist state and return to its rightful place in the Islamic world. That strategy was composed of several elements:

Alliance with the dominant right-wing political party for protection in return for providing voter support in elections;

Establishing a capital base with successful businesses to provide support for Islamist projects;

Establishing an independent political party and forming coalitions with other parties, whether the right of center or left of center, and securing key ministries;

Recruitment of tarikat followers to positions of authority in state institutions such as the Ministry of Education, Judiciary, and State Planning Organization;

Expansion of religious schools and securing entry of imam hatip graduates into universities;

Establishing a strong presence in state security forces (i.e. the police);

Infiltrating the armed forces to neutralize its laic orientation; and

Capturing the state from within and changing Turkey's constitution to establish an Islamic state.Footnote8

The first phase of political Islam’s rise in Turkey occurred from 1950–1972. This was the infancy period of formal political organization. The Islamic Democracy Party (İslam Demokrasi Partisi, IDP) was the first Islamist political party to enter into politics during the multi-party period. Established in 1951 by an anti-Semite, Cevat Rifat Atilhan, the party lasted only six months. But it launched the Islamist arrow into the political arena. The IDP established the first campaign slogan of the Islamists: ‘The sun of welfare and happiness will rise when [we] take the Koran into our hands. Believers unite and form your regime’Footnote9 It is essential to note the symbolic reference to’‘refah’ (welfare) in this slogan. In the ensuing years, those who played crucial roles in establishing other Islamist political parties used similar phrases of religious importance.

During the 1960s, a group of Islamists affiliated with Sheikh Mehmet Zahit Kotku entered the political scene and encouraged Necmettin Erbakan to enter politics as an independent candidate from Konya. Kotku belonged to the Nakşibendi order (tarikat) and was head of the powerful İskender Paşa (Iskender Pasha) congregation (dergah). Erbakan's previous move to be a candidate from the main center-right political party, the Justice Party (Adalet Partisi, AP), was blocked by AP leader Suleyman Demirel. This led Kotku and his followers to launch another Islamist political party. Soon after, several influential Islamist figures met at the home of the then AP Senator Ahmet Tevfik Paksu to discuss whether or not a new political party should be formed.Footnote10 When they decided to form a new party, the participants agreed to seek the blessing and permission of Kotku, who was receptive to the idea. Following their meeting with Kotku, Erbakan, Paksu, and others met to decide on the party’s name. The name, however, came from an influential Islamist writer, Eşref Edip, who said that he had a dream where a voice told him what the party’s name and emblem should be. Thus, they agreed on the name of the National Order Party (Milli Nizam Partisi, MNP) and its emblem was a hand pointing to the heavens in an Islamic symbol. Another crucial aspect of this episode is that we observed a coalition of the Nakşibendi and Nurcu tarikats in the formation of the MNP.Footnote11

There was no doubt in anyone’s mind at the time that Erbakan was receiving his orders from Kotku. However, the political life of this party was also short. Soon after the military intervention in 1971, the Constitutional Court ordered the closure of the MNP for advocating anti-secular political views and thus opposing the Republic. Erbakan left for Switzerland, began publishing a newspaper Tek Nizam (One Order), and established the Milli Görüş (National Vision) organization.Footnote12 The latter was to become one of the most essential support bases of future Islamist parties in Turkey and served as a mentor such future leaders such as Erdoğan. Following a court dismissal of his personal case, Erbakan returned to Turkey and formed the National Salvation Party (Milli Selamet Partisi, MSP) on October 11, 1972.Footnote13 This party became a critical partner of coalition governments until the 1980 coup and utilized its vital position to expand its infiltration of state institutions with crucial personnel appointments. Its efforts ended abruptly when the military carried out a coup in September 1980 and banned all political parties.

However, before the military coup, the Islamists did achieve a significant victory in putting Turkey on the agenda of a global Islamist movement. This occurred at a Sharia congress in Pakistan.Footnote14 It was known as the International Sharia Congress and was sponsored by a Saudi Arabian institution Rabitat al-Alam al-Islami (The World Muslim League). The participants, including Islamists from Turkey, signed a declaration that outlined many goals, including:

The constitutions of the Islamic countries should be restructured according to Islamic principles, and the Arabic language should be spread among the people.

The civil code should be replaced by Sharia law.

Women should obey the Islamic code.

Necessary economic and political steps should be taken to establish modern Islamic states based on the Sharia.

At every level of education, Islam must be taught as a mandatory subject.

In secondary schools students must memorize the Koran.

Every Muslim should memorize the five principles of Islam.

To accomplish these goals, Islamic schools must be established in every country.

To establish an Islamic Unity, all Muslim states should first recognize and accept their Islamic identity and form a confederation under the guidance of a commonly elected Caliph.Footnote15

The Sharia Congress in Pakistan was just the beginning of a significant strategy of Islamist counter-revolution in Turkey. Its significance can be seen in the educational changes the AKP introduced following its second election victory in 2007. Reforms in education not only brought mandatory ‘religion and values’ courses to public schools, they also allowed the hijab to be worn by girls starting in the fifth grade.Footnote16 The AKP also reversed the previous mandatory eight years of public education with a 4+4+4 system and expanded İmam-Hatip middle schools, thus enabling parents to send their children for eight years of a religion-focused education system. As İlkay Meriç explains, this was not a model for secular progressive education but one that aimed to achieve a publicly-stated position of Erdoğan: future generations with conservative and religious values.Footnote17

Since transitioning from military rule in 1983, Islamists have followed a multi-track strategy in re-entering political life. The center-right Motherland Party (Anavatan Partisi, ANAP), under the leadership of Turgut Özal, initially attracted many former MSP followers. To strengthen the coalition between Islamic fundamentalists and nationalists, Özal embraced the Türk-İslam Sentezi (Turkish-Islamic Synthesis) of the İlim Yayma Cemiyeti (Community for Spreading Wisdom) as the party position of ANAP. This synthesis emphasized the goal of establishing a strong and powerful Turkey to re-establish the glory of the Ottoman Empire and outlined broad-ranging policy goals for the government that included: (1) union between religion and state; (2) society built on an Islamic foundation; (3) coalition between government and the military, and (4) rule of religious law. It also identified enemies of the movement that needed to be controlled and/or eliminated: atheists, separatists, Western humanists, intellectuals who blamed Islam for the fall of the Ottoman Empire, and the laïcists. It is important to note that the current neo-Ottomanist movement under the AKP continues to emphasize these principles, thus providing clear proof of a long-term strategy of goals of political Islam in the country.

Erdoğan emerged on the political scene when Erbakan reorganized Islamists under the banner of the Welfare Party following a general amnesty. He became mayor of Istanbul in 1994. He was one of the critical trusted students of Erbakan with solid views and criticism of Turkey’s Western orientation. The return of Erbakan and birth of the Welfare Party ended the Islamist voters’ mass support of ANAP. Starting with the 1991 national elections, Erbakan and the Welfare Party began to have more electoral success. The party leadership expressed views and policy positions of the National Vision that were sympathetic to the conservative and disenchanted voters and created a nationwide network of devoted followership guided by party activists and party elites.

The informal party organization of the Welfare Party was extensive and relied on a tightly controlled network of activists and volunteers.Footnote18 Graduates of Imam-Hatip schools further grew in numbers and found employment throughout state bureaucracy.Footnote19 The strategy of public education through Imam-Hatip schools was to bear fruit in the future as the ever-increasing number of individuals among the graduates entered the workforce as dedicated followers of the Islamist movement.

The Welfare Party succeeded beyond its leaders’ wildest dreams in the 1995 national and local elections. Yet, their initial success was soon followed by their downfall. The ‘post-modern coup’ of 1997 brought down the Welfare Party-led coalition government between Erbakan and Tansu Çiller of the True Path Party and eventually to the closure of Welfare Party on January 16, 1998.

Afterward, some of Erbakan's closest allies in the party established the Virtue Party (Fazilet Partisi) and attempted to tone down their criticism of secularism to present a new image for their party. These younger elites, led by individuals as Erdoğan and Abdullah Gül, emphasized the need for a system-oriented political party and openly challenged the older guard led by the then-leader of the Virtue Party, Recai Kutan. However, it was pretty clear that Erbakan continued to call the shots in the party while being banned from politics for five years. The influence of Erbakan on the became apparent during the first grand congress of the Virtue Party in May 2000. Fed up with the old guard’s tight control and its unwillingness to consider the new ideas of a younger generation, reformists (yenilikçiler), led by Gül, challenged Kutan for the party’s leadership. The reformists were upset by the traditionalists’ (gelenekçiler) domination of the party’s Central Committee and by Erbakan's continuing control of appointing new members to the party’s leadership.Footnote20 The Virtue Party, however, did not last long and faced a quick ban by a decision of the Constitutional Court for its anti-secular and anti-system orientation.

Following the closure of the Virtue Party, the reformists and traditionalists split up and began to chart their separate ways. Erbakan chose his close ally Kutan as the chairman of their camp’s new party – the Felicity Party (Saadet Partisi, SP). On the reformist front, Erdoğan and other reformists established the AKP, which received 51 members of the National Assembly, mostly former Virtue Party members. Powerful figures from the Virtue Party (such as Gül, Bülent Arınç, Cemil Çiçek, Abdülkadir Aksu, and Ali Coşkun) decided to join the reformists.

The AKP in power

When AKP was established, it paid far greater attention to creating a system-oriented image as its references to religion were softened, often included under the general category of allowing a greater expression of individual civil and political rights.Footnote21 It also presented itself as more pro-EU and business-friendly and less nationalistic and Islamist than its predecessors. It seemed that Islamic-oriented elites had a historic opportunity to reform Islamic politics in Turkey and establish a truly democratically-oriented Islamic political party. It should be noted, however, that system-oriented in Turkey meant a party had to be committed to the principle of laïcité. Erdoğan and his allies’ call for a system-oriented political party thus suggested a new beginning for Islamic-oriented parties in Turkish politics.

The question, however, was whether the AKP’s rhetoric would be matched by policies and actions to convince the general public and secular establishment that it was a genuine system-oriented conservative political party without Islamist aspirations. It gained this opportunity after coming to power after the 2002 elections. On this score, it did have some tangible accomplishments. The AKP leadership did a tremendous job, at least initially, of portraying the party as a coalition of individuals from different political points of view. It pushed ahead with EU harmonization reforms, which convinced most observers that this was a system-oriented political party with a moderate religious orientation. However, when one considers the nature of two powerful foundations (vakıf) that played a significant role in establishing the AKP, its system-oriented image should have been seriously questioned. These foundations were the Birlik Vakfı and the İlim Yayma Vakfı. The latter was the product of the previously discussed İlim Yayma Cemiyeti. The former was established in 1985 by Korkut Özal who, with three other Milli Görüş followers (Abdulkadir Aksu, Ali Coşkun, and Cemil Çiçek), aimed to bring together Islamic congregations to promote the Turkish-Islamic synthesis in everyday life and political arena. Other AKP founders with a Milli Görüş background included (in addition to Erdoğan) İsmail Kahraman, Hasan Kalyoncu, and Zeki Ergezen.Footnote22 There was no doubt for any shrewd observer of Turkish politics that these foundations were oriented to socialize their members toward system consensus. On the contrary, they wanted to change the system.

The AKP forged another key coalition with the powerful Gülen Movement. This was an interesting partnership that is perfectly captured by the notion ‘the enemy of my enemy is my friend’ Both Erdoğan and Fethullah Gülen, who has been living in self-imposed exile in the United States since 1999, viewed the Kemalist establishment, especially the powerful Turkish military, as their enemies. However, the two leaders represented fundamentally opposing branches of political Islam in Turkey. While Erdoğan emerged from the Nakşibendi grouping, whereas Gülen was a leader of the Nurcus. Historically, these two branches viewed each other as opponents with different views on replacing the laïcité system with an Islamic state. While Erdoğan used EU-inspired reforms to gradually break the military’s grip on politics, Gülenists successfully infiltrated the lower ranks of the judiciary, the military, and other major state institutions. The Gülenists also built a global network that benefited from the help of the AKP government to open doors for their business ventures and schools.Footnote23 This alliance paved the way for Erdoğan to establish his hegemony within the AKP and Turkey. However, this alliance was to be short-lived.

Following his second election victory in 2007, Erdoğan began to gradually reverse political reforms, successfully removed liberals from AKP leadership positions, and replaced his opponents in the rank and file with staunch Milli Görüş followers close to him. New policy measures included delegating the once-powerful National Security Council to an advisory role and gradually putting the armed forces under civilian authority. Erdoğan also revised the separation of powers between Turkey’s executive and judiciary, concentrating powers in the hands of the former, which he controlled. Erdoğan’s and Gülen’s next move targeted the military establishment. Through trumped-up charges, 300 active and retired high-ranking officers were sent to prison through conspiracy cases such as Balyoz and Ergenekon. The purged active duty officers were then replaced by those sympathetic to Erdoğan and Gülen. With the military threat gone, it became apparent that a showdown between Erdoğan and Gülen was a matter of time – who would be pre-eminent in reshaping Turkey's future.

The first shot across the bow came from the Gülenists. In December 2013, a series of police investigations revealed financial corruption involving high-level members of AKP, including Erdoğan's son Bilal and three cabinet ministers. Erdoğan characterized the investigations as a judicial coup designed by the Gülen movement and unleashed a comprehensive crackdown against the latter. The State Prosecutor, a close associate of Gülen, and other investigators were quickly removed from their positions and reassigned to far corners of Turkey. Furthermore, police officers in charge of the operations, who were also members of the Gülen Movement, were arrested. The next phase of this clash occurred when the military attempted a coup in July 2016. It was a total failure. There are, however, serious questions concerning who planned the failed coup. Was it planned by Gülen and his followers within the officer corps? Or was it somehow staged by Erdoğan to expose those Gülenist officers?

In any event, Erdoğan used the coup to purge Gülenists and military officers loyal to Ataturk’s secular principles who were critical of Erdoğan and his political regime.Footnote24 According to information available through open source Turkish media, the authorities arrested, sacked, or suspended over 130,000 people including soldiers, judges, teachers, policemen, businessmen and sports officials, detained nearly 143 journalists, arrested or removed almost 50,000 military, police, and other security personnel from their posts, suspended 143 admirals and generals (out of 375), dismissed 262 military judges and prosecutors, dismissed 47 district governors and arrested 30 of 81 provincial governors, dismissed 3,000 judges and prosecutors and arrested over 1,500 lawyers and confiscated their properties, dismissed more than 15,000 Education Ministry officials, revoked licenses of 21,000 teachers, fired 3,623 professors and 1,500 deans, closed 1,043 private schools, 1,299 charities and foundations, 19 trade unions, 15 universities, 35 medical institutions, and military schools(placing them all under state control), and closed more than a hundred media outlets.Footnote25 With this move, Erdoğan eliminated his most powerful enemies. With mass public support behind him, he then sponsored a referendum to replace Turkey’s parliamentary system with a strong presidential one. This passed in April 2017, and in July 2018, after having triumphed in the presidential elections the previous month, Erdoğan began to formally transform Turkey's long-standing parliamentary system into a heavily centralized presidential one. This new system has entrenched his one-man authoritarian rule.Footnote26

According to Ihsan Yilmaz and Galib Bashirov, what has emerged in Turkey during the last two decades of AKP rule can be termed Erdoğanism. It refers to the emerging political regime in Turkey that has four main dimensions: (1) electoral authoritarianism as the political system; (2) neopatrimonialism as the economic system; (3) populism as the political strategy; and (4) Islamism as the political ideology.Footnote27

Voter realignment in Turkey

The ability of political parties to adapt to voter realignment is at the heart of survival in politics. Political party adaptation can form a dynamic process where systemic developments characterized by social, cultural, and economic changes in the country affect mass political behavior and parties’ response. Systemic changes refer to socioeconomic development broadly defined. This spills over to political development in the form of a civic society practicing its political choice in the electoral process. As individual citizens’ attitudes, beliefs, and values change, their participation in the political process reflects these changes. If they are satisfied with the policies and views of the political party they support, we can expect this support to continue. In this case, the political party in question is adapting to the changing position of its support base. If the party fails to make these adjustments, voters are likely to move on to other political parties that are more in line with their new position(s). This happened in Turkish electoral politics during the 1990s, ending with the rise of the AKP.Footnote28 Party leadership is also a very important component of adaptation. Leaders recognize not only the policy needs of the country but also see the changes in the party’s support base and implement reforms that reflect these changes within the party structure. Furthermore, if the top leader has a charismatic nature that attracts the masses, it would contribute to adaptation.

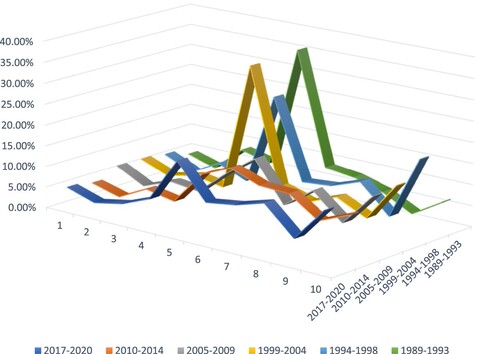

Since the beginning of multiparty politics in 1946, the Turkish political system has experienced a turbulent history, ridden with ideological polarization and fractionalization of political parties and interest groups, as well as periods of social and political unrest. The most recent voter realignment in Turkey occurred in the mid-1990s with a significant shift from the political center and more traditional center-right parties toward the far right.Footnote29 The rise in conservative values among the public also supports this trend and could explain the attraction of political parties like AKP for the electorate. Data from the World Values Survey in Turkey (see ) provide important insight into individuals’ self-identification on a political ideological scale (0 = far left to 10 = far right).

What one observes in should be alarming for the future of democracy in Turkey. The ideological middle has collapsed in Turkey along with a rise in individual identification with the conservative political right since the 1990s. And when the median voter’s dominance of the ideological spectrum disappears, what follows is polarization and decline of democratic systems. These results confirm earlier findings of Ersin Kalaycıoğlu and Ali Çarkoğlu on rising religiosity in Turkey since 1994 and that the entire electorate shifted to the right of the ideological spectrum, thus highlighting a major voter realignment in this country. Since the mid-1990s, surveys reveal a steady and stable shift of the entire political landscape from left to right, with the centrist block collapsing. Election results further support this observation. The reasons behind the shift are similar to the 1970s. Simply, coalition governments of traditional parties in the 1990s failed to address the economic and socio-political crises facing the country. When the financial meltdown of 2001 occurred, the voters simply voted the AKP into power.

As discussed in the section on religiosity and political values below, Turks’ traditional values also explain this realignment. The ever-increasing number of Imam-Hatip graduates have been spreading their Islamist influence throughout Turkey. It is certainly true that not all graduates of these schools favor the reversal of all of Atatürk’s reforms. However, they do receive ample socialization and education that demonize Atatürk while their conservative/traditional values are elevated.Footnote30 The rise and increased influence of the Gülenist movement further contributed to this phenomenon. Economic hardship added to the materialist and survivalist needs of ordinary citizens who longed for a leader who could meet their aspirations. The importance of this realignment for the AKP is quite telling. By portraying itself as a reformist conservative and moderately Islamist political party, the AKP captured the conservative and other disgruntled center-rightist voters’ support in 2002. The self-proclaimed reformists did not have to do much as the ideological bloc moved in their direction to the right, and the old parties of that spectrum lost their legitimacy in the eyes of the electorate. The unfortunate outcome of this realignment and the AKP's subsequent actions is that this has made it easier for the gradual transformation of the countryis political system from a parliamentary democracy to an authoritarian presidential system.

Religiosity and Turks’ social and political values

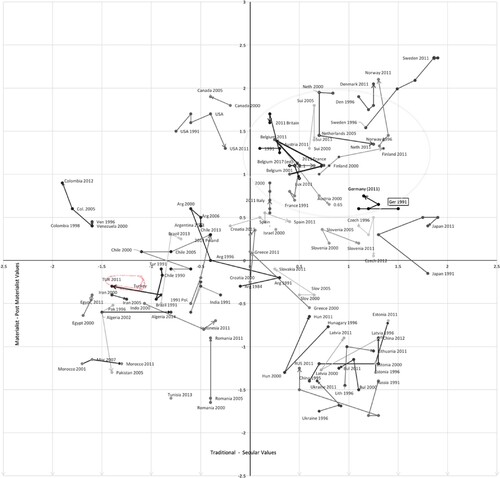

Traditional and survivalist values of the average Turkish citizen can be seen in , which plots Turkey against other selected countries from data found in the World Values Survey.Footnote31 Two indices provide rich information along the x and y-axis. As the two maps from 1996 and 2020 show, average societal values in Turkey along these measures have not changed significantly and are in the opposite quadrant from the Western democracies. This is an important factor in explaining, at least in part, why the public remained largely silent about Erdoğan's systematic dismantling of democracy in Turkey during the last decade.

Figure 2. Inglehart-Welzel Culture Map. Source: Yesilada et al, Global Power Transition, 35. Note: The small circle in the left-bottom quadrant shows shifting position of average Turkish values on the I-W index since 1991. The larger circle in the right-top quadrant is the EU countries.

To understand the relationship between values and democratization at the societal level, the two dimensions need to be explained. The first dimension is Traditional (Religious) vs. Secular (Rational) values, which reflect division between societies regarding religion and religiosity. The more traditional societies emphasize religion, while more secular-rational ones do not. For example, societies near the traditional pole emphasize the importance of parent–child ties and deference to authority, absolute standards and traditional family values, and reject divorce, abortion, euthanasia, and suicide. They tend to have high levels of national pride coupled with a nationalistic outlook. Societies with secular-rational values have opposite preferences in all of these areas.

The second critical dimension of cross-cultural variation is linked with the transition from an industrial society to post-industrial society, which brings a distinction between Survival (materialist values associated with the industrialization phase of development) and Self-expression (postmodern/post-industrial) values.Footnote32 Factor analysis of the mean national scores reveals that individualism, autonomy, and self-expression (measures of postmodern value system) all tap a single underlying dimension that accounts for 91 percent of the cross-national variance. The basic argument suggests that the unprecedented wealth accumulation in advanced societies during recent generations resulted in a more significant portion of the population that takes survival for granted. These individuals shift their priorities from an overwhelming emphasis on economic and physical security toward an increasing focus on subjective well-being, self-expression, and quality of life. Individuals also become free to emphasize a general need for self-expression and question authority. They demand political participation.Footnote33 The result is a gradual transition toward democratization in autocratic nations and more effective political representation in democratic countries.Footnote34

However, important nuances must be addressed concerning the transition to democratic governance. For example, it is essential to note that while the desire for freedom is universal, human emancipation is not prioritized when individuals grow up when survival is uncertain. Welzel’s more recent work on changing values supports this observation.Footnote35 On the flip side, adopting democratic institutions does not automatically produce a culture that emphasizes self-expression values either. Take, for example, the findings on ‘tutelary democracies’ including Turkey.Footnote36 One needs to distinguish between embedded (genuine) and institutional democracies. The former represents countries with more post-modern and secular values, whereas the latter is found in traditional/religious and materialist/survivalist societies. The latter is more prone to collapse and transformation into an authoritarian political system than the former, as the population in materialist/survivalist societies is more concerned with making ends meet than how democratic their government institutions are.

An additional factor that is intensely debated among scholars is over how religion affects the relationship between the emergence of post-industrial values and the transition to democracy, especially when we consider the distinction between institutionalized and genuine (embedded) democracies. As Yilmaz explains, modernization influences values in a predicted direction, but the magnitude and occasionally the direction of the influence depend on cultural heritage. This concept mainly pertains to religious traditions.Footnote37 Put differently, it can be argued that religious tradition is the most crucial factor in cultural change. This is why observed differences in secularized populations, such as Western European countries versus the United States, depend on their respective religious traditions or heritage. This would also explain the exception observed in high-income Islamic societies where emancipatory values have yet to emerge on a large scale.

As seen in , since the mid-1990s, an increasing number of Turks are supportive a strong leader who would not have to bother with parliament and elections. shows how these results break down by education level from the most recent iteration of the survey. When controlled for the education level of respondents, the following is observed (). It is important (and perhaps surprising) to note that majority of those surveyed favored a strong authoritarian leader, regardless of their level of education. Even university-educated Turks are divided between 47 percent in favor and 42 percent against such a leader. Put differently, whereas modernization theory would predict that education would lead to more democratic attitudes, we do not witness such an outcome in Turkey. Furthermore, in , we see that when controlled for values on the World Values Survey’s autonomy index, there is almost an even divide on support for an undemocratic leader between traditional/religious (who are far more numerous) and more secular respondents.

Table 1. Support for a strong, undemocratic leader.

Table 2. Preference for a strong, undemocratic leader by education level.

Table 3. Support for undemocratic leader by autonomy level.

Measuring the religiosity of Turks through another question also displays an insight into the effects of changes made in the educational system under the AKP. provides views on religion and science. An overwhelming majority of Turks believe that when science and religion conflict, the latter is always right. Furthermore, as we saw in on support for an undemocratic leader, the level of education attained does not affect the results significantly.

Table 4. Views on conflict between science and religion.

Prospects for the future

As the Republic nears its centenary on October 29, 2023, the observations in this paper should raise concern for the future of the country’s democracy. When the AKP came to power in 2002, it embarked on ambitious economic and political reforms that finally promised to bring embedded democracy to Turkey and have Turkey accepted among the EU member states. Yet, since 2007, most of the initial reforms that were made to meet EU membership requirements have been reversed and have been replaced by an authoritarian dictatorship of a single individual. It should be noted that the EU's actions have aided Erdoğan in achieving his ambitions. Each time Turkey showed a positive step toward meeting accession requirements, the EU moved the finish line and also demanded more concessions from Turks towards Cyprus and Greece, irrespective of how the latter two have undermined chances to solve the Cyprus problem or bilateral disputes between Greece and Turkey.Footnote38 Nonetheless, from 2008 onward, it is clear that democratic development in Turkey has regressed, and educational and social developments have resulted in the deepening of societal cleavages that threaten the country’s stability.

While the AKP can celebrate its numerous election victories, its recent actions should concern anyone who cares about the future of Turkey. The same observation also applies to what has happened to the AKP itself. Once a coalition of varying political ideologies, it has become a party of one man who firmly controls the actions of elected politicians and appointed officials.Footnote39

There is no denying that Erdoğan is proud and self-confident, often arrogant and vindictive, and has a different vision for Turkey than his secular predecessors. He enjoys popularity among a large sector of Turkish society by projecting the image of a strong leader. They call him Reis (captain or leader of the country). This attribute is highly valued among many Turks, as shown above. As Harold Lasswell noted many years ago about influential leaders, Erdoğan is equally successful in displaying his motives on public objects and rationalizing them in terms of public interest. He can ‘reach and touch’ those from the lower classes and manipulate their feelings by frequent referrals to past Ottoman greatness and Islamic values. Concerning the latter, he is keen on promoting sectarian Sunni values and institutions that would spread Islamic principles as opposed to Kemalist secularism. He views his role as the ‘legitimate’ leader of the faithful and expects all who are below him to bow to his preferences.

This is typical of a former mürid (loyal follower) mentality and explains, in part, why he is unwilling to step aside and become an impartial president. Erdoğan was a mürid under the late Necmettin Erbakan, dating back to 1976 as a youth leader in the NSP. His rise to the helm of AKP is an impressive story of political intrigues that deserves in-depth analysis beyond the scope of this paper. As far as he is concerned, he has paid his dues to reach this position and is likely to insist on staying in power as long as possible. Certainly, the preference for a strong leader and traditional/conservative values within Turkish society favor Erdoğan. He is also charismatic and capable of persuading voters to flock to his side.

However, is it possible that given the terrible economic conditions in Turkey during the past several years (as well as the catastrophic earthquakes, whose impact was made worse by shoddy construction and lack of enforcement of building codes) could make the voters think twice and abandon him and hand AKP a defeat? Many liberal and secular observers of Turkey would like to believe this is possible. Yet, one should not be overly optimistic. To tackle the economic hardship, Erdoğan is forging significant financial deals with rich Gulf states to inject fresh capital into the economy. His populist economic policies also aim to satisfy the aspirations of the average citizen, albeit they might be less than desired. History also informs us that no dictator who succeeded in concentrating absolute power in his hands has been replaced through fair elections. One fear is that, if all looks bleak, he would not hesitate to venture into a foreign conflict to galvanize national fervor and rally support around him.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Birol A. Yeşilada

Birol Yesilada is Professor of Political Science and Director of the Turkish Studies Center at Portland State University. He has written extensively on Turkish political economy, Turkish political culture, and Turkish foreign policy.

Notes

1 For a good analysis of what this election means for Turkey’s future, see a special report from The Economist. “Erdoğan’s Empire,” January 20, 2023.

2 Yesilada, “Virtue Party.” Turkish Studies Spring, 2002, pp. 62–81.

3 For more on Hedef 2023, see “İşte ekonomide 2023 hedefleri,” Haberturk, January 23, 2011, available at https://www.haberturk.com/ekonomi/makro-ekonomi/haber/594402-iste-ekonomide-2023-hedefleri

4 These terms used by various observers of Turkish politics (i.e., Ersin Kalaycıoğlu, Mahir Tokatlı, Birol Yeşilada) refer to a presidential system that resembles late Ottoman constitutional monarchy but with a highly centralized authoritarian head of state and government. (See references)

5 It is not the purpose of this paper to discuss the extensive network of those political parties as they have been written about extensively in the past. For example, see Yesilada, “The Virtue Party” Turkish Studies Spring, 2002, and Yesilada, “Refah Party Phenomenon,” in Birol Yesilada, ed., Comparative Political Parties and Party Elites: Essays in Honor of Samuel J. Eldersveld, Ann Arbor, the University of Michigan Press, 1999, pp. 123–50, and Banu Eligur, The Mobilization of Political Islam in Turkey, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

6 For a detailed discussion, see Eldersveld, Political Parties in American Society, New York: Basic Books, 1982; Robert Michels, Political Parties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies in Modern Democracies, New York: Dover, 1959, first published in German in 1911, Elmer Schattschneider, Party Government, New York: Holt, Reinhart and Wiston, 1941, and Birol Yesilada, “Realignment and Party Adaptation: The Case of Refah & Fazilet Parties,” in Politics, Parties and Elections in Turkey, eds. Sabri Sayari and Yilmaz Esmer, Boulder: Lynne Reinner Publishers, 2002.

7 Eldersveld and Walton, Political Parties in American Society, 2nd ed., New YorK: Bedford/St.Martins, 2000 pp., 387–90.

8 For a detailed discussion of this point, see Yesilada, “The Virtue Party, ” Turkish Studies Spring, 2002,

9 Celil Bozkurt, Yahudilik ve Masonluga Karsi Cevat Rifat Atilhan, Istanbul, Dogu Kütüphanesi, 2012..

10 Among those who were present at this gathering were key Islamist figures, including Hasan Aksay, Mustafa Yazgan, Arslan Topçubaşı, Osman Yüksel Serdengeçti, and İsmail Hakkı Yılanoğlu. The consensus was that through its veto of Erbakan, the AP had turned its back on Islamist values. See Okutucu, Istikamet Seriat, Refah Partisi [Direction Sheria: The Refah Party], Istanbul: Yeryüzü Yayınları, 1996, p. 29.

11 The charter members of this party included such key figures of the Nakşibendi Order and Nurcu movement as Erbakan (member of the parliament from Konya and Nakşi), Ahmet Paksu (member of parliament and Nurcu), and Hasan Aksay (former member of parliament and Nakşi). These individuals played an important role in Islamist politics for years to come. The initial chairman of the MNP was Süleyman Arif Emre. Erbakan replaced him on February 8, 1970.

12 Milli Görüs, officially known as the Avrupa Milli Görüş Teşkilatı (The National Vision Organization of Europe) and re-named İslam Toplumu Milli Görüş Teşkilatı—ITM (the National View Association of Muslim Community) is the largest Muslim organization in Germany with strong ties to Turkey. Its aim is two-fold: (1) to shield Turkish immigrants from Western cultural and political influences, and (2) to establish an Islamic state in Turkey based on the rule of Sharia. Necmettin Erbakan established this organization in Europe in the early 1970s. The organization supported the political parties of Erbakan over the years – National Order Party, National Salvation Party, Welfare Party, Virtue Party, and the Felicity Party.

13 Other founding members of the party included Aksay, Fehmi Cumalıoğlu, Recai Kutan, Korkut Özal, and Salih Özcan. These individuals attained prominent positions in the party and played important roles in reformulating the Islamist political movement after the 1980 coup. For details see Yesilada, “The Refah Party Phenomenon,” in Comparative Political Parties and Party Elites, ch. 6, and and Eligur, The Mobilization of Political Islam in Turkey.

14 Yesilada, “Islam, Dollars and Politics: The Political Economy of Saudi Capital in Turkey. Paper presented at the 23rd Annual Meeting of the Middle East Studies Association in Toronto, Canada during November 15-18, 1989.

15 Ibid.

16 Murat Aksoy, “AK Parti’nin.” https://t24.com.tr/yazarlar/murat-aksoy/ak-partinin-resmi-din-dayatmaya-girisimi,10226. For a detailed analysis of how AKP revised secular education in Turkey see Elif Gençkal Eroler, Dindar Nesil Yetisştirmek, Istanbul: İletişimYayınları 2019.

17 İlkay Meriç, “4+4+4’un Arkasına Gizlenenler,” [Hiding Behind 4+4+4] https://marksist.net/ilkay-meric/444un-arkasina-gizlenenler.

18 The party maintained a divan (council) in every district, comprised of 50 regular and 50 alternate members. In addition, there were neighborhood representatives who maintained an information database on everyone living in that area, including each family unit. There was also a network of headmasters and teachers (hatipler ve öğretmenler), who engaged people in discussion at the local coffee houses and other gathering places. Another informal network came from the Koran courses and the Preacher and Prayer Leader Schools (İmam Hatip Okulları). The religiously oriented parties’ connection to religious orders is essential because these orders provide bloc votes for them. See Eligur, The Mobilization; Yesilada, “The Virtue Party”; Adenauer Foundation, Refah Partisi Üzerine Bir Araştırma [A Study on the Refah Party] (Ankara: Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Citation1996), 45-48 and Adenauer Foundation, Yerleşik Siyasi Partiler Arastirmasi [A Study of the Established Political Parties] (Ankara: Korand Adenauer Foundation, Citation1996) pp. 50–55.

19 These schools make up the backbone of Islamist movement in Turkey. For their impact on public education see Cakmak, “Pro-Islamic Public Education.”.

20 In 1999, a number of leading reformists (Gül, Cemil Çiçek, Ali Coşkun, and Abdulkadir Aksu) resigned from the committee. Other key individuals in this power struggle were Erdoğan and Melih Gökçek, the mayor of Ankara. However, the reformists did not consider Gökçek a reliable ally. Erdoğan, on the other hand, was removed from office in 1998 when the State Security Court had found him guilty of inciting domestic unrest and religious hatred for, among other things, having quoted from a poem by Ziya Gökalp in a speech given in Siirt in December 1997. As a result of this decision he was also barred from politics. Until that time, Erdoğan was viewed as the most likely challenger to Erbakan and Kutan in the party. Erdoğan was hand-picked by Erbakan for the former’s oratory skills and was elected mayor of Istanbul in 1994 on the Welfare Party ticket. In addition to having recited Gökalp’s poem, the Court cited Erdoğan’s statement where he identified society as having two fundamentally different camps – those who blindly follow a charismatic leader, such as the Kemalists, and those who follow justice and were true Muslims who believed in Sharia.

21 Yesilada, “Virtue Party,” 78–9.

22 These individuals saw themselves as the continuum of the Islamist National Turkish Student Union (Milli Türk Talebe Birliği) of 1966. They succeeded in bringing together followers of the powerful İskender pasha congregation and Fethullah Gülen and played a key role in establishing the Virtue Party and later the AKP. Many members of AKP cabinets had close ties to Korkut Özal. In addition, Özal had substantial ties to members of the İlim Yayma Vakfı and was considered mentor of many of its key figures including Kadir Topbaş (Istanbul Metro Mayor), Ahmet Davutoğlu (Foreign Minister), Ali Coşkun, Mehmet Aydın (State Minister), and Nevzat Yalçıntaş. See Cumhuriyet, May 26, 2006.

23 It is not in the scope of this paper to provide an in-depth discussion of the Gülen Movement. For a detailed analysis see Yusuf Akdag, Din, Kapitalizm, ve Gülen Cemaati, (Istanbul, Evrensel yayinevi, 2011), Caroline Tee, “ Gülen Movement: BetweenTurkey and International exile,” in Muhammad Upal and Caroline Cusack eds. Handbook of Islamic Movements and Sects, (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 2021), ch. 4, pp. 86–109.

24 Ihsan Yilmaz and Galib Bashirov, “The AKP after 15 years: emergence of Erdoğanism in Turkey,” Third World Quarterly, Vol. 39, no. 9, p. 8.”

25 Wikipedia has an occasionally updated page that as of 2023 lists over 200 news articles and more extensive reports that document the extent of these purges. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2016%E2%80%93present_purges_in_Turkey.

26 Kemal Kirişci and Ilke Toygür, Turkey’s new presidential system and a changing west Implications for Turkish foreign policy and Turkish-West relations. January 2019. Brookings Institution.

27 Ihsan Yilmaz and Galib Bashirov, “The AKP after 15 years: emergence of Erdoğanism in Turkey,” Third World Quarterly, Vol. 39, no. 9, pp. 1812–1830.

28 This relationship between voter realignment and party adaptation is a complex one to operationalize and test but one can employ a set of criteria outlined by Samuel Eldersveld and Hanes Walton Political Parties in American Society. 2nd ed. that include: (1) The type of leadership selected by a party as its candidates for public office, (2) The organizational form and process which party adopts, whether very democratic and decentralized internally, or hierarchically controlled from the top down, or an in-between ‘stratified’ structure with considerable autonomy in decision making at all levels of the party, (3) The social base of support for the party, or the character of its social group coalition, (4) The ideological line and direction of the party in the context of public opinion shifts, (5) The strategies and tactics used in campaigns that will activate those loyalties, floating voters, and apathetic individuals to ensure victory, and (6) The party activists at the middle and lower levels of the organization, the ‘working elites’ at the base of the system, upon which the party relies heavily.

29 For a detailed analysis of voter realignment in Turkey see Çarkoğlu and Kalaycıoğlu Türkiye’de Siyasetin and The Rising Tide; Toprak, Türkiye’de Farklı Olmak; Toprak and Çarkoğlu, “Değişen Türkiye’de Din”; and Esmer, World Values Survey” and Yılmaz Esmer, World Values Survey: Turkey Wave No. 5 (World Values Survey, 2007) and “Radikalizm ve Aşırıcılık, {Radicalism and Extremism]” published in Milliyet May 31, 2009, Binnaz Toprak et al., Türkiye’de Farklı Olmak [To be Different in Turkey], (Istanbul: The Open society Institute and Bosphorus University, 2008).

30 There are many examples of attacks on Ataturk by teachers in these schools as well as in schools of the Gulen movement. One only needs to Google Turkish media over time to see the incidents as well as documentation and analysis by investigative reporters and scholars. For example see, Sendika.org “Atatürk düşmanlığı ölmedi, imam hatiplerde yaşıyor,” November 15, 2017, available at https://sendika.org/2017/11/ataturk-dusmanligi-olmedi-imam-hatiplerde-yasiyor-456396/

31 The author of this article is one of the principal investigators of the World Values Survey and has published different versions of these maps in academic journals and books. For examples see Yesilada, EU-Turkey Relations in the 21st Century,London. Routledge, 2013 and Yesilada et al., Global Power Transition and the Future of the European Union, London: Routledge, 2018.

32 Ronald Inglehart “Mapping Global Values.” Comparative Sociology 5, No. 2-3 (June 2006, pp. 115–13

33 Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel, Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy. Cambridge, Cambirodge University Press, 2005.

34 Ibid.

35 Christian Welzel, Freedom Rising. Cambridge, Cambridge University press, 2013..

36 Hakkı Taş, Turkey – from tutelary to delegative democracy, Third World Quarterly, 36:4, (2015)776–791, DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1024450, Rhoda Rabkin, “The Aylwin Government and ‘Tutelary Democracy: A Concept in Search of a Case?” Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs Vol. 34, No. 4 (Winter, 1992-1993), pp. 119-194, Kemal Kirisci and Amanda Sloat, “The rise and fall of liberal democracy in Turkey: Implications for the West,” Brookins: Foreign Policy DOI: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/FP_20190226_turkey_kirisci_sloat.pdf; Lauren McLaren and Burak Cok, “The Failure of Democracy I Turkey: A Comparative Analysis,” Government and Opposition , Volume 46 , Issue 4 , 2011 , pp. 485 – 516 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2011.01344.x.

37 Yilmaz Esmer, “Globalization, ‘MacDonalization” and Values: Quo Vadis.” Esmer, Y., Pettersson, T., eds. Measuring and Mapping Cultures: 25 Years of Comparative Value Surveys. Leiden: Brill 2007.

38 For an analysis of this issue see Yesilada, EU-Turkey Relations in the 21st Century.

39 Hakan Yavuz and Ahmet Erdi Ozturk, eds., Islam, Populism and Regime Change in Turkey: Making and Re-making the AKP, London: Routledge, 2021.

References

- Adenauer Foundation. Refah Partisi Üzerine Bir Araştırma. Ankara: Konrad Adenauer Foundation, 1996.

- Adenauer Foundation. Yerleşik Siyasi Partiler Arastirmasi. Ankara: Konrad Adenauer Foundation, 1996.

- Akdag, Yusuf. Din, Kapitalizm, ve Gülen Cemaati. Istanbul: Evrensel Yayinevi, 2011.

- Aksoy, Metin. “AK Parti’nin ‘resmi din’ dayatma girişimi,” T24, September 24, 2014, available at https://t24.com.tr/yazarlar/murat-aksoy/ak-partinin-resmi-din-dayatmaya-girisimi,10226.

- Cakmak, Diren. “Pro-Islamic Public Education in Turkey: The Imam-Hatip Schools.” Middle East Studies 45, no. 5 (2009): 825–846.

- Çarkoğlu, Ali, and Ersin Kalaycıoğlu. Türkiye’de Siyasetin Yeni Yüzü. Istanbul: Open Society Institute, 2006.

- Çarkoğlu, Ali, and Ersin Kalaycıoğlu. The Rising Tide of Conservatism in Turkey. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

- Eldersveld, Samuel. Political Parties in American Society. New York: Basic Books, 1982.

- Eldersveld, Samuel, and Hanes Walton. Political Parties in American Society. 2nd ed. New York: Bedford/St. Martins, 2000.

- Eligur, Banu. The Mobilization of Political Islam in Turkey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Eroler, Elif Gençkal. Dindar Nesil Yetisştirmek. Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2019.

- Esmer, Yilmaz. “Globalization, ‘MacDonaldization’ and Values: Quo Vadis.” In Measuring and Mapping Cultures: 25 Years of Comparative Value Surveys, edited by Yilmaz Esmer, and Thorleif Pettersson, 79–98. Brill: Leiden, 2007.

- Esmer, Yilmaz. World Values Survey: Turkey Wave No. 5. World Values Survey, 2007.

- Inglehart, Ronald. “Mapping Global Values.” Comparative Sociology 5, no. 2–3 (2006): 115–136.

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Christian Welzel. Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Kirisci, Kemal, and Amanda Sloat. “The rise and fall of liberal democracy in Turkey: Implications for the West,” Brookings Institution, February 2019, available at https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-rise-and-fall-of-liberal-democracy-in-turkey-implications-for-the-west/.

- Kirişci, Kemal, and Ilke Toygür. “Turkey’s new presidential system and a changing west Implications for Turkish foreign policy and Turkish-West relations.” Brookings Institution, January 2019, available at https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/20190111_turkey_presidential_system.pdf.

- McLaren, Lauran, and Burak Cok. “The Failure of Democracy in Turkey: A Comparative Analysis.” Government and Opposition 46, no. 4 (2011): 485–516.

- Meriç, Ilkay. “4+4+4’un Arkasına Gizlenenler,” April 2012, available at https://marksist.net/ilkay-meric/444un-arkasina-gizlenenler.

- Michels, Robert. Political Parties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies in Modern Democracies. New York: Dover, 1959. (First published in German in 1911).

- Okutucu, Mustafa Hakki. Istikamet Seriat: Refah Partisi. Istanbul: Yeryüzü Yayınları, 1996.

- Rabkin, Rhoda. “The Aylwin Government and ‘Tutelary’ Democracy: A Concept in Search of a Case?” Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 34, no. 4 (1992–1993): 119–194.

- Schattschneider, Elmer. Party Government. New York: Holt, 1941.

- Taş, Hakki. “Turkey – from Tutelary to Delegative Democracy.” Third World Quarterly 36, no. 4 (2015): 776–791.

- Tee, Caroline. “Gülen Movement: Between Turkey and International Exile.” In Handbook of Islamic Movements and Sects, edited by Muhammad Upal, and Caroline Cusack, 86–109. Leiden: Brill, 2021.

- Toprak, Bonnaz, et al. Türkiye’de Farklı Olmak. Istanbul: The Open Society Institute and Bosphorus University, 2008.

- Toprak, Binnaz, and Ali Çarkoğlu. Değişen Türkiye’de Din Toplum ve Siyaset. Istanbul: TESEV, 2006.

- Welzel, Christian. Freedom Rising: Human Empowerment and the Quest for Emancipation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Yavuz, M. Hakan, and Ahmet Erdi Ozturk, eds. Islam, Populism and Regime Change in Turkey: Making and Re-Making the AKP, London: Routledge, 2021.

- Yesilada, Birol. “Islam, Dollars and Politics: The Political Economy of Saudi Capital in Turkey.” Paper presented at the 23rd Annual Meeting of the Middle East Studies Association in Toronto, Canada, November 1989.

- Yesilada, Birol. “The Refah Party Phenomenon in Turkey.” In Comparative Political Parties and Party Elites: Essays in Honor of Samuel J. Eldersveld, edited by Birol Yesilada, 123–151. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999.

- Yesilada, Birol. “Realignment and Party Adaptation: The Case of Refah and Fazilet Parties.” In Politics, Parties and Elections in Turkey, edited by Sabri Sayari, and Yilmaz Esmer, 157–178. Boulder, CO: Lynne Reinner, 2002.

- Yesilada, Birol. “Virtue Party.” Turkish Studies 3, no. 1 (2002): 62–81.

- Yesilada, Birol. EU-Turkey Relations in the 21st Century. London: Routledge, 2013.

- Yesilada, Birol, et al. Global Power Transition and the Future of the European Union. London: Routledge, 2018.

- Yilmaz, Ihsan, and Galib Bashirov. “The AKP After 15 Years: Emergence of Erdoğanism in Turkey.” Third World Quarterly 39, no. 9 (2018): 1812–1830.