ABSTRACT

The recent authoritarian turn and democratic backsliding around the world have raised concerns over increased instability and violent conflicts. Turkey is a striking example of this authoritarian turn with the transition from a multiparty democracy to a competitive authoritarian regime. With seven in-depth case studies from Turkey, this special issue sheds light upon the changing dynamics of violence and social coexistence in countries that experience democratic decline from a transdisciplinary perspective. In this introductory article, we briefly trace the authoritarian transition and societal fault lines in Turkey, discuss the case studies presented in this special issue, and draw out our contribution to the literature.

Introduction

What does the recent advance of authoritarianism around the world mean when it comes to prospects for peaceful coexistence or conflict in divided societies? This special issue sheds light on the complex and changing dynamics of societal cohesion and violence during an authoritarian transition in one country characterized by significant cleavages and high degrees of political polarization: Turkey.

With the ‘democratic recession’ (Diamond Citation2015) and global advance of authoritarianism over the last two decades, adherence to norms of liberal democratic governance has faltered in many places. This global trend in governance has coincided with a related trend in international relations: the passing of the ‘unipolar moment’ (Krauthammer Citation1990; Zakaria Citation2019) and the growing belief – championed by thinkers in countries like Russia, China, and Turkey but not only there – that we are witnessing the emergence of a multipolar world order (Lukyanov Citation2010; Cooper and Flemes Citation2013; Chebankova Citation2017) in which important power brokers like Russia, China, and Turkey contest Western hegemony and the liberal norms that govern the international system. These trends in governance and international relations have consequences for the likelihood of conflict and how it is managed. Existing research going back as far as Gurr (Citation1974) suggests that states that undergo an authoritarian transition may be more prone to violent conflict, and the decline of liberal norms in the international system may have consequences for dominant patterns of peacebuilding and conflict resolution, which have long been informed by liberal assumptions and norms. The forceful power projection and joint ‘management’ of conflicts by Russia and Turkey in Syria, Libya, and the South Caucasus in recent years has caught western powers off guard. Similarly, the use of military-auxiliary forces has become a common method to address violent domestic conflicts (Kovacs and Svensson Citation2013) around the world. From Russia, China, and Turkey to Kyrgyzstan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, states increasingly resort to authoritarianism, militarism, and neo-patrimonialism to manage order in conflict-affected regions (Smith et al. Citation2020; Lewis et al. Citation2018).

These trends call particular attention to the changing dynamics of social coexistence and conflict in countries that experience democratic decline. Here, existing scholarship tells us to expect higher degrees of instability, and we may also assume a greater willingness on the part of non-democratic regimes to rely on authoritarian and illiberal means of managing conflict and grievances. Turkey is undoubtedly a striking example of the recent authoritarian turn, with its transformation from a multiparty democracy, albeit flawed and under military tutelage, to today’s (competitive) authoritarian state (Öktem and Akkoyunlu Citation2016; Esen and Gumuscu Citation2016, Citation2018, Citation2020; Somer Citation2016). It is also a country with a number of potentially volatile social, cultural, and ethnic cleavages that have caused conflict and strife in the past. Hence, Turkey of today might be seen as somewhat of a petri dish for studying patterns and processes of conflict and cooperation in countries that undergo democratic decline.

In this special issue, we therefore present seven in-depth case studies from Turkey. They provide a sharp and introspective lens on the dynamics of social coexistence and how conflicts have been transformed, maintained, and reconstituted while the country transitioned into authoritarianism. The authors examine multiple sides and sites of the socio-political change, including not only major contestations that pertain to Alevis and Kurds but also new modalities of societal conflicts and coexistence. Shedding light on the changing dynamics of coexistence and societal conflicts during Turkey’s transition into authoritarian governance, the contributions also bring up-to-date empirical and theoretical insights into peace and conflict studies. As such, the special issue connects with recent collections of studies dealing with the dismantling of democratic institutions (Öktem and Akkoyunlu Citation2016) and rethinking power in Turkey through everyday practices (Massicard Citation2018).

These articles have originated from the fourth annual conference of the Consortium of European Symposia on Turkey (CEST) in November 2018, hosted by the Stockholm University Institute for Turkish Studies (SUITS). Scholars from various fields of study – anthropologists, sociologists, political scientists, and students of international relations – came together to explore the dynamics of social coexistence and conflict in Turkey during authoritarian resurgence. This conference was supported by generous funding from Stiftung Mercator and Stockholm University.

Peace, violence, and political regimes: living together during authoritarian transition

Conflict studies have long argued that hybrid regimes that combine democratic and autocratic institutions are more prone to conflict compared to both fully autocratic and consolidated democratic regimes (Auvinen Citation1997; Fearon and Laitin Citation2003; Gurr Citation1974; Hegre et al. Citation2001; Henderson and Singer Citation2000; Muller and Weede Citation1990; Reynal-Querol Citation2002; Slinko et al. Citation2017). These studies underline that fully autocratic governments undermine the opportunity for armed conflict by the use of high levels of threat and coercion against opponents, while democratic governments circumvent the risk of violence by providing institutions to express grievances through non-violent collective actions. In contrast, hybrid regimes that neither use full force to suppress the opposition nor provide any genuine political competition to voice social discontent are more prone to political violence.

Moreover, it seems like political transition itself is often associated with turbulence and instability. Cederman et al. (Citation2010) for example, find that regime transformation – both democratization and autocratization – is associated with increased civil violence. Autocratization tends to lead to violence more abruptly: ‘the collapse of democratic rule is generally associated with more or less instant outbreaks of political violence, especially in the case of military coups’ (Cederman et al. Citation2010, 387).

Some of these findings have been revised recently with alternative measures and concepts. Recent studies unpack the box of democratic and autocratic regime categories and further our understanding about how different forms of autocratic and democratic regimes create incentives and disincentives for conflict occurrence. These studies suggest that military regimes and multi-party electoral autocracies have a higher risk of armed conflict compared to single-party authoritarian regimes as they lack an institutional base to co-opt political opposition through positions and rents (Fjelde Citation2010). Moreover, electoral autocracies like competitive authoritarian regimes have substantially lower risk of conflict than non-electoral regimes (Bartusevičius and Skaaning Citation2018; Knutsen et al. Citation2017) since elections – even if non-competitive – serve to reduce incentives for violence by decreasing the legitimacy of violence in the eyes of opponents and facilitating co-optation of opponents through political competition.

While these studies focus on the risk of civil war or large-scale violence, a review of case studies on democratic backsliding reveals a broad repertoire of repressive modes of governance and state violence that permeate into institutional structures and everyday life. Fuelling polarization and partisan interests in society, political leaders with authoritarian ambitions cover their attempts to capture democratic institutions (Svolik Citation2019) and set up a politically dependent judiciary, loyal legislative, and putative regime security force. The erosion of checks and balances and the expansion of executive authority allow leaders to crack down on any sort of public opposition, including civil society groups, media organizations, and political opponents, and to repress their voices through harassment, torture, arrest, assaults, electoral fraud, abuse of state resources, and media censorship. While the basic rules of political competition are hollowed out, elections turn out be full of risks for contenders, who are exposed to repression, restrictions, imprisonment, even exile. However, these rising illiberal and authoritarian orders are not simply based on violence and coercion but produce subtle strategies to sustain domestic orders and contain conflicts. Case studies from Angola (De Oliveira Citation2011), Rwanda (Waldorf Citation2015), sub-Saharan Africa (Jones et al. Citation2013), Central Asia (Owen et al. Citation2018), Indonesia (Smith Citation2014), Thailand (Chalermsripinyorat Citation2020), and Sri Lanka (Lewis Citation2010) reveal how not only authoritarian but also democratic and semi-democratic regimes employ illiberal modes of peacebuilding and authoritarian conflict management practices (Lewis et al. Citation2018). Such measures include spatial domination and control, hierarchical or selective distribution of resources, use of state propaganda and other forms of information control and knowledge production, and ‘legal bargaining’, all employed to co-opt and/or neutralize political opponents.

The complexity of these authoritarian practices call attention not only to direct forms of violence, e.g. repression, terrorism, torture, or crimes, but also to indirect forms of violence such as structural, symbolic, and everyday violence to understand the changing dynamics of social coexistence and conflict during authoritarian transitions (for an extensive analysis, see Scheper-Hughes and Bourgois Citation2004). The erosion of rule of law and the decline of democratic institutions can have a dramatic impact on structural violence that is embedded in power relations and structural inequalities deteriorating the rights of disadvantaged groups like ethnic and religious minorities, sexual minorities, women, migrants, etc. Polarizing and securitizing discourses that consistently create majorities and minorities in society reify social differences and aggravate symbolic violence that is anchored into the normative order of society. Conversely, refusal to recognize groups and their grievances and attempts to silence minorities may amount to another form of structural violence as discrimination and inequalities in societies go unaddressed. There are also everyday forms of violence, such as interpersonal violence, domestic violence, or vigilantism, that are intertwined with broader relations of patronage, conflict, and cooptation in society but not considered as violent conflict per se, falling short of what at least most large-N studies of civil war or ethnic conflict examine. In this special issue, we propose to consider violent conflict as a phenomenon that occurs along a broad spectrum ranging from small to large scale violence, and from indirect to direct forms of violence. Not limiting ourselves to massive outbreaks of violence between or directed at certain groups allows the contributions in this special issue to identify a broader range of social, political, economic, and psychological consequences of democratic breakdown and societal violence. Doing so, we hope, also allows for a richer assessment of the potential for sustainable peacebuilding and social reconciliation processes in the future.

Turkey as a case study: authoritarian transition and societal cleavages

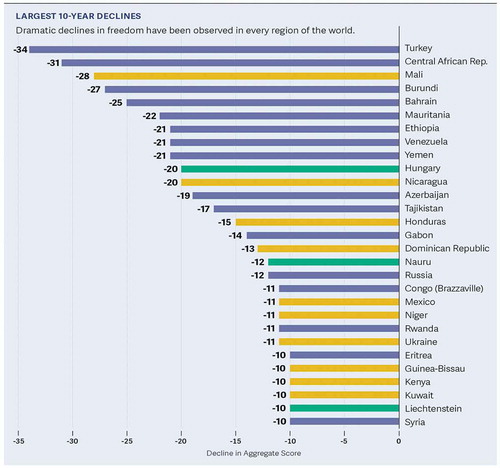

Against this backdrop, and for two simple reasons, Turkey provides a very interesting case for study the interplay between democratic backsliding, different forms of violence and societal conflicts. First of all, Turkey has undergone a dramatic process of autocratization or democratic backsliding over the past decade (see ). For sure, Turkey has never been a fully consolidated liberal democracy. Periodic military coups and military-bureaucratic tutelage along with institutional and legal limitations that stretch back to the rise of the AKP (Justice and Development Party, Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi) in 2002 meant that Turkish democracy was always flawed. There were already narrow limits to democratic freedoms, especially concerning the social and political rights raised by Islamic and Kurdish movements that were framed as threats to national unity and the democratic system (Kogacioglu Citation2003). Somer (Citation2016) talks about this as Turkey’s ‘old authoritarian regime’. We agree with Somer (Citation2016) that Turkey during the 1980s could not be considered as having a fully consolidated democracy, that there were authoritarian features of the political system, and that we can therefore only speak of an ‘incomplete democratic transition’ (Somer Citation2016, 485) as having occurred by the 1990s. And yet, within the above-described parameters, and in the periods between the violent and disruptive but brief military interventions, until recently Turkey remained a multiparty democracy – albeit flawed – with a separation of powers, competitive and fair elections, peaceful transfers of power, and a diverse and independent media landscape.

Today, the situation is radically different. Turkey has arguably seen a more dramatic decline in measures of freedom than perhaps any other country over the past decade (Freedom House Citation2018) (see Diagram 1). Somer (Citation2016) describes the situation as ‘new authoritarianism’, having been added to remnants of the ‘old’ authoritarian regime. Öktem and Akkoyunlu (Citation2016) called what we have witnessed in Turkey an ‘exit’ from democracy. In a series of Esen and Gumuscu (Citation2016, Citation2018, Citation2020) have described how Turkey has now arrived at what they call a ‘competitive authoritarian’ regime, following Levitsky and Way (Citation2010). In the end, we agree with their assessment:

After several years of democratic backsliding, Turkey now fails to meet even the basic requirements of an electoral democracy … . Elections are now unfair; civil liberties are systematically violated, and the playing field is highly skewed in favor of the incumbent party (Esen and Gumuscu Citation2020, 1).

Hence, Turkey quite clearly serves as a paradigmatic case of democratic backsliding or autocratization.

The second reason why Turkey is an intriguing case to understand the changing dimensions of social conflicts during authoritarian transition is that Turkey is also a country with several deep societal fault lines along which conflict can, and has, occurred. The longest standing and most serious such cleavage is an ethnic conflict, the so-called Kurdish problem in Turkey, with the ongoing armed conflict between the PKK and the Turkish state that left behind more than thirty thousand deaths (see Çandar Citation2020 for a recent examination of the Kurdish problem). There is also a sectarian division between a Sunni majority and a large Alevi Muslim minority that has occasionally been the source of violence in the past (Yilmaz and Barry Citation2020), and in recent years, polarization over religiosity versus secularism, between those who support the AKP and President Erdogan and those who resent it, and between Kemalists and pro-Islamists (Aydın-Düzgit Citation2019) have all emerged as potential fault lines along which conflict may occur.

The combination, then, of being a country that has seen a dramatic transition from a partially consolidated democracy to a competitive authoritarian regime and having a number of deep societal divisions, makes Turkey a rather obvious case to examine the effects of democratic decline on societal conflict. While we do not claim that all findings presented here are readily generalizable beyond the Turkish context, we do believe that the empirical and theoretical contributions in this special issue can help scholars to better understand social crises and conflicts in other countries that experience similar democratic decline, even if their transformations are less spectacular than those we have seen in Turkey. Moreover, in light of the significant political, social, and economic uncertainty that Turkey is currently facing, an examination of the dynamics of peace and conflict in the country is of significant importance for analysts, policy makers, and activists who want to understand the modalities of violent conflict and repression in order to prevent and transcend them.

Contributions

This special issue provides the reader with a better understanding of the dynamics of social coexistence and violence during authoritarian transition and hopes to contribute to peace and conflict studies in five major mays. First, while the large part of conflict studies focuses on domestic order and peacebuilding in conflict regions, we broaden the social and political landscapes exploring the dynamics of social coexistence and violence not only in conflict regions but also in relatively peaceful sites. This heterogenous picture of Turkey’s authoritarian order allows us to observe changing power hierarchies and the sense of (in)security within society and understand how this dynamic power landscape impacts on distinct forms of violence to emerge at the subnational level (Raleigh Citation2014). Second, we bring an in-depth analysis of the reasons, social dynamics, and subnational mechanisms that drive distinct forms of violence. Notwithstanding the caveat of overdetermining violence, we flip the question of violence on its head and fine-tune it by asking which social relations prevent, create, and produce it. Rather than seeing violence as a by-product of ancient hatred between abstract groups, many of the contributors to this special issue descend to the local level and focus on the strategic action implicated in violent behaviour in which individuals or social groups put their interests into work, form collective discourses, and ultimately reshape the wider framework of state-society relationships. In so doing, we go beyond the dichotomous conceptualization of peace–violence and narrow the space between them, revealing the interconnections between episodic or/and systematic violence and everyday social interactions in order to explain the transition from relatively peaceful coexistence networks into conflictual behaviours.

Third, we do not shy away from looking at ways in which categorical distinctions and boundaries between public-private, legal-extralegal, and legitimate-illegitimate violence (for an extensive analysis, see Scheper-Hughes and Bourgois Citation2004) – which are so deeply ingrained in conflict studies, including examinations of Turkey’s Kurdish conflict – are frequently blurred in practice. Our contributors examine the blurring of these boundaries, as paramilitary violence can be endorsed by the state and legalized with the transition into authoritarian governance in conflict regions (Ayhan 2021). Even extralegal social violence can be seen by various societal actors as ‘legitimate’ and applauded implicitly or explicitly by state authorities and citizens against the perceived enemies of the state or in-group (Saglam Citation2021; Kadioglu Citation2021), and violence that disproportionally impact certain parties and groups may not be recognized as such, especially by partisans of incumbent governments who are tempted to blame their rivals for provoking such incidents (Toros and Birch Citation2021). Moreover, the contributions reveal not only the workings of physical violence but also that of symbolic violence, which can take the form of internalized hostility, humiliations, and legitimation of inequalities among citizens (Bourdieu Citation1997), and they highlight the importance of cultural and moral contexts to understand the emergence, perception, and functions of violence. We show how this observed ambiguity ingrained in the definition and perception of violence is fundamental rather than incidental if we want to understand the intertwining of identities, actors, and motives that generate violent behaviour in polarized contexts.

Fourth, we bring novel and hard-to-collect empirical evidence about crucial but under-theorized and under-researched aspects of social peace in Turkey from a bottom-up view, exploring nascent social interactions, collective imaginations, daily encounters, collective and individual anxieties, inner struggles, new modalities of governance, law, and subjectivities during authoritarian transition. Finally, we provide nuanced analyses of the limits and potentials of the conflict resolution processes including the Alevi opening and the Kurdish peace process that have significantly affected public and political life in Turkey in recent decades. These analyses offer in-depth insights into pressing issues that any conflict resolution efforts will face in contemporary Turkey: national, religious, and institutional boundaries of the dominant Turkish Sunni identity (Bozan Citation2021), multi-layered damage of ethnic conflicts on social relations (state–individual, state–group, and intergroup relations) (Celik Citation2021), and the rift between macro-level political negotiations and meso-level political actors in an atmosphere of political polarization (Dilek Citation2021).

We organize the special issue along two axes. The first section of the special issue teases out the dynamics of different types of violence and social coexistence of everyday life in contemporary Turkey. The second section discusses the limits of and possibilities for conflict resolution under the pressures of growing authoritarianism in Turkey. The findings, we believe, are relevant not solely for those who aim to understand the Turkish context better but would benefit also those who trace and explore conflict resolution and peacebuilding across the world.

Articles

Drawing upon rich ethnographic research in Tophane, a historical neighbourhood of Istanbul, Defne Kadioglu Polat (Citation2021) traces the local transformation and changing state–society relationships from the perspective of conservative-nationalist residents who support the incumbent AKP government. In contrast with arguments that see vigilantism as undermining state authority (Bora Citation2008) or as a consequence of social, political, and economic polarization in Turkey, Kadioglu shows how residents articulate their discontent against gentrification policies using the hegemonic discourses (public morality, Islam, and nationalism) promoted by the AKP that allow them to remain within the moral hierarchies set by the state. She demonstrates that in a context where government authorities implicitly or explicitly endorse violence against oppositional voices and institutions are not responsive to citizens’ demands, some residents use vigilante violence against perceived ‘subversives’ (newcomers, Kurds, tourists, alcohol drinkers) to display their discontent and legitimize their violent behaviours through moralistic discourses. As such, she suggests that consent in authoritarian contexts is neither unwavering loyalty nor fully compliant but that they are arenas in which contention can co-occur within or alongside consent (Kadioglu Polat Citation2021).

Erol Saglam (Citation2021) extends the discussion on vigilantism by engaging with the literature on the state, vigilantism, and conspiracy theories based on his detailed ethnographic research on nationalist communities in Trabzon, a city in northeast Turkey that is considered one of the hotbeds of Turkish nationalism. The city comes into the public limelight especially with occasional vigilante attacks against the perceived ‘enemies of the state’, an ambiguous and ever-growing category in Turkish public discourse that changes according to the context and includes journalists, human rights defenders, NGO activities, tourists, etc. Saglam offers a rich narrative of the masculine world of Turkish nationalists in which men embody and enact the state through their engagement with conspiratorial narratives and participation in social violence. His account shows how vigilante violence in this nationalist context does not undermine the state authority but maintains and endorses it, extending the state’s control over society via men’s bodies that ‘become the interfaces, means, and agents of state power’ (Saglam Citation2021, 222). In this respect, state privileges (violence, surveillance, punishment) are delegated to ordinary people who uphold law and order in the name of the state and nation. Saglam’s study also reveals how state-sponsored moral-judicial hegemony becomes integrated into the social fabric of everyday life, endorsed by masculine subjects, and becomes instrumental in their interactions with state agents.

Ayhan Isik (Citation2021) makes a welcome intervention into paramilitary violence that characterize many conflicts including Turkey’s Kurdish conflict. He sheds light on a complex and dark phenomenon that is an under-researched theme, namely pro-state paramilitary groups and paramilitary violence. Pro-state paramilitary groups have become widely seen as part of the ‘deep state’ in Turkey but remained an open secret as part of the ‘dirty war’ between the state and the PKK in Kurdish regions. Isik also identifies the period starting from the 1990s as the ‘paramilitarization of the state’ in line with Bozarslan (Citation2018), during which state authorities endorsed and legalized more and more the activities of paramilitary groups, reminding us of Harvey’s remark about the crucial role of the state to define legality to maintain its monopoly over violence and power (Harvey Citation2003, 145). In line with the proliferation of paramilitary groups, violence in the region extends unrestricted, far surpassing its initial target, the PKK, and targeting Kurdish civilians, politicians, and human rights advocates with the allegation of being pro-PKK. Isik also gives detailed information about their use and operations in external interventions since the resumption of violence between the PKK and the state in 2015/2016.

Emre Toros and Sarah Birch (Citation2021) make an important contribution to the study of electoral violence. Reminding us that ‘violence is in the eye of the beholder’ (Scheper-Hughes and Bourgois Citation2004, 2), they shed light on the cultural construction of violence in a context of high political polarization based on rich empirical data. Their analysis demonstrates how partisanship and the region of residence shape the blame attribution of electoral violence. A very important finding of the study is that partisans are reluctant to blame electoral violence on affiliates of their own party whereas they are quick to blame the supporters of their traditional political rivals. This impact is sharper in regions ridden by conflict, as evidenced by Turkey’s Kurdish regions. Another remarkable finding of the study is the common tendency of ‘victim blaming’ among citizens, as a large proportion of the population accuse partisans and officials of the pro-Kurdish HDP of instigating violence despite the empirical evidence that shows that the pro-Kurdish HDP is disproportionately affected by electoral violence incidents.

Aysegul Bozan’s (Citation2021) study of the perspectives of young AKP activists on the Alevi Opening, which was organized in 2010 as a forum to discuss Alevi demands, flushes out the potentials and limits of conflict resolution and reconciliation efforts in Turkey. Bozan’s in-depth interviews with young AKP activists illustrate the limits of the conservative Sunni identity that constitutes the main electoral base of Turkey’s right and conservative parties. As Bozan’s interviews demonstrate, the lived experience of these partisan youth is often highly differentiated from Alevis’, even for those who live in the same city with Alevis like in Sivas, making it hard for them to come to terms with and understand the pain and grief among the Alevi population towards the Madimak Massacre in Sivas on 2 July 1993, when 33 artists and intellectuals were burned to death by Islamist and nationalist groups. However, Bozan’s study also reveals the potential for a change in attitude among AKP-affiliated youth towards Alevi demands in line with the Alevi Opening, as half of the participants indicated pro-Opening attitudes for pragmatic (the uselessness of prohibitions, better control of worship places), political (pluralistic attitudes, citizenship rights), or subjective (respect for others) reasons.

Esra Dilek’s (Citation2021) contribution provides a detailed analysis of Track Two diplomacy, a form of diplomacy that aims to build a better relationship between competing actors and explore new ideas for conflict resolution through often informal and unofficial contacts between non-state actors. Track Two diplomacy was implemented during Turkey’s Kurdish peace process in the form of a series of workshops organized under the guidance of the London-based Democratic Progress Institute’s (DPI) Turkey programme. Dilek carefully reveals how these workshops were efficient in informing political actors about comparative perspectives and different conflict resolutions processes that helped, in turn, to build capacity among political actors for policymaking. Based on extensive interviews, she reveals how participants filtered comparative insights according to their political agenda and used them to substantiate their interests. However, in a polarized political environment, Track Two diplomacy fell short of creating common agendas and purposes among policymakers, especially on controversial issues such as disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) and transitional justice.

Ayse Betül Celik (Citation2021) contributes a critical analysis of Turkey’s Kurdish peace process and highlights certain features that made social reconciliation difficult: disregard for oppositional actors’ voices, electoral polarization, continuing nationalist discourses, and insufficient bottom-up reconciliation and trust-building mechanisms. She argues that since conflict damages relations at multiple levels (state–individual, state–group, and intergroup relations), peace processes should be designed as a multi-layered process. Turkey’s peace process prioritized negotiations between the PKK and the Turkish state, but it failed to filter down to the local level and address the needs for ethno-cultural justice and rights as well as reconciliation over social polarization and competing histories. As such, it could not repair relations between victims and perpetrators (individual level), repressed groups and repressive systems/groups (inter-group level), and the state with minority groups. Celik (Citation2021) reminds us that a lasting resolution to this long-standing conflict may depend on reforms that are not easily accommodated within Turkey’s contemporary authoritarian framework.

In their attention to the social dynamics and subnational mechanisms that drive distinct forms of violence (Isik Citation2021; Kadioglu Citation2021; Saglam Citation2021; Toros and Birch Citation2021) and conflict resolution (Bozan Citation2021; Celik Citation2021; Dilek Citation2021) in an authoritarian setting, the contributors to this special issue provide a better understanding about how authoritarianism trickles down and changes social relations at both micro and macro levels. There is a need to better understand and theorize the everyday underpinnings of social conflict and collective violence if we want to understand insecurity and instability for countries under democratic decline. It is our hope that this special issue will constitute a useful contribution to this undertaking.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Imren Borsuk

Imren Borsuk is a researcher at the EUME-Berlin and Stockholm University Institute of Turkish Studies. Her work focuses on urban poverty, gender, communal conflict, and interethnic relations. Her works have been published in European Urban and Regional Studies, Palgrave Macmillan, Journal of International Relations, Transparency International publications, All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace.

Paul T. Levin

Paul T. Levin is Director of the Stockholm University Institute for Turkish Studies. His work focuses on Turkish politics and international relations, Turkey-EU relations, foreign aid, nationalism, collective identity, governance, democracy, and authoritarianism. He is Director of the Consortium for European Symposia on Turkey (CEST), Associate Researcher at the Swedish Institute for International Affairs, and Research Fellow at the Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul.

References

- Auvinen, J. 1997. Political conflict in less developed countries. Journal of Peace Research 34, no. 2: 177–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343397034002005.

- Aydın-Düzgit, S. 2019. The Islamist-secularist divide and Turkey’s descent into severe polarization. In Democracies divided: The global challenge of political polarization, ed. T. Carothers and A. O’Donohue, 17–37. Washington D.C: Brookings Institution Press.

- Bartusevičius, H., and S.E. Skaaning. 2018. Revisiting democratic civil peace: Electoral regimes and civil conflict. Journal of Peace Research 55, no. 5: 625–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343318765607.

- Bora, T. 2008. Türkiye’nin linç rejimi [ The lynch regime of Turkey]. Istanbul: Iletisim Yayınları.

- Bourdieu, P. 1997. The forms of capital. In Education, culture, economy and society, ed. H. Halsey, H. Launder, P. Brown, and A. Stuart Wells, 46–58. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bozan, A. 2021. The Alevi issue and democratic rights in Turkey as seen by young AKP activists: Social conflict, identity boundaries and some perspectives on recognition. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 21, no. 2: 273–292. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2021.1909283.

- Bozarslan, H. 2018. The Turkey of the 2010’s: Conflict, pluralism, and spaces of life in a modern anti-democracy. Keynote lecture presented at the Societal Conflict and Cohabitation in Turkey and Beyond, CEST Conference, November 29, 2018, Stockholm University.Sweden

- Çandar, C. 2020. Turkey’s mission impossible: War and peace with the kurds. London: Lexington Books.

- Cederman, L.E., S. Hug, and L.F. Krebs. 2010. Democratization and civil war: Empirical evidence. Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 4: 377–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343310368336.

- Celik, A.B. 2021. Inclusive citizenship and societal reconciliation within Turkey’s kurdish issue. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 21, no. 2: 313–332. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2021.1909284.

- Chalermsripinyorat, R. 2020. Dialogue without negotiation: Illiberal peace-building in Southern Thailand. Conflict, Security & Development 20, no. 1: 71–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14678802.2019.1705069.

- Chebankova, E. 2017. Russia’s idea of the multipolar world order: Origins and main dimensions. Post-Soviet Affairs 33, no. 3: 217–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2017.1293394.

- Cooper, A.F., and D. Flemes. 2013. Foreign policy strategies of emerging powers in multipolar world: An introductory review. Third World Quarterly 34, no. 6: 943–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.802501.

- De Oliveira, R.S. 2011. Illiberal peacebuilding in Angola. The Journal of Modern African Studies 49, no. 2: 287–314. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X1100005X.

- Diamond, L. 2015. Facing up to the democratic recession. Journal of Democracy 26, no. 1: 141–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2015.0009.

- Dilek, E. 2021. Rethinking the role of track two diplomacy in conflict resolution: The democratic progress institute’s Turkey program. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 21, no. 2: 293–311. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2021.1909291

- Esen, B., and S. Gumuscu. 2016. Rising competitive authoritarianism in Turkey. Third World Quarterly 37, no. 9: 1581–606. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1135732.

- Esen, B., and S. Gumuscu. 2018. Building a competitive authoritarian regime: State–business relations in the AKP’s Turkey. Journal of Balkan and near Eastern Studies 20, no. 4: 349–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19448953.2018.1385924.

- Esen, B., and S. Gumuscu. 2020. Why did Turkish democracy collapse? A political economy account of AKP’s authoritarianism. Party Politics, 11 May, https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068820923722.

- Fearon, J., and D. Laitin. 2003. Ethnicity, insurgency, and civil war. American Political Science Review 97, no. 1: 75–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055403000534.

- Fjelde, H. 2010. Generals, dictators, and kings: Authoritarian regimes and civil conflict 1973–2004. Conflict Management and Peace Science 27, no. 3: 195–218. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894210366507.

- Freedom House. 2018. Freedom in the world 2018. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2018.

- Gurr, T.R. 1974. Persistence and change in political systems, 1800-1971. The American Political Science Review 68, no. 4: 1482–504. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1959937.

- Harvey, D. 2003. The new imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hegre, H., T. Ellingsen, S. Gates, and N.P. Gleditsch. 2001. Toward a democratic civil peace? Democracy, political change, and civil war, 1816–1992. American Political Science Review 95, no. 1: 33–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055401000119.

- Henderson, E., and D. Singer. 2000. Civil war in the post-colonial world, 1946–92. Journal of Peace Research 37, no. 3: 275–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343300037003001.

- Isik, A. 2021. Pro-state paramilitary violence in Turkey since the 1990s. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 21, no. 2: 231–249. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2021.1909285

- Jones, W., R.S. De Oliveira, and H. Verhoeven. 2013. Africa’s Illiberal State-builders. Working Paper Series no. 89, Oxford Refugee Studies Centre, Oxford.

- Kadioglu Polat. D. 2021. ‘No one is larger than the state.’ Consent, dissent, and vigilant violence during Turkey’s neoliberal urban transition. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 21, no. 2: 189–211. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2021.1909290.

- Knutsen, C.H., H.M. Nygård, and T. Wig. 2017. Autocratic elections: Stabilizing tool or force for change? World Politics 69, no. 1: 98–143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887116000149.

- Kogacioglu, D. 2003. Dissolution of political parties by the constitutional court in Turkey: Judicial delimitation of the political domain. International Sociology 18, no. 1: 258–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580903018001014.

- Kovacs, M.S., and I. Svensson. 2013. The return of victories? The growing trend of militancy in ending armed conflicts. Paper prepared for the 7th General Conference of the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR), 4–7 September, Science Po Bordeaux, Domaine Universitaire. France

- Krauthammer, C. 1990. The unipolar moment. Foreign Affairs 70, no. 1: 23. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/20044692.

- Levitsky, S., and L.A. Way. 2010. Competitive authoritarianism: Hybrid regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lewis, D. 2010. The failure of a liberal peace: Sri Lanka’s counter-insurgency in global perspective. Conflict, Security & Development 10, no. 5: 647–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14678802.2010.511509.

- Lewis, D., J. Heathershaw, and N. Megoran. 2018. Illiberal peace? Authoritarian modes of conflict management. Cooperation and Conflict 53, no. 4: 486–506. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836718765902.

- Lukyanov, F. 2010. Russian dilemmas in a multipolar world. Journal of International Affairs 63, no. 2: 19–32.

- Massicard, É. 2018. Introduction: Rethinking power in Turkey through everyday practices. Anthropology of the Middle East 13, no. 2: 1–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.3167/ame.2018.130201.

- Muller, E., and E. Weede. 1990. Cross-national variation in political violence: A rational action approach. Journal of Conflict Resolution 34, no. 4: 624–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002790034004003.

- Öktem, K., and K. Akkoyunlu. 2016. Exit from democracy: Illiberal governance in Turkey and beyond. Southeast European Society and Politics 16, no. 4: 469–80.

- Owen, C., S. Juraev, D. Lewis, N. Megoran, and J. Heathershaw, eds. 2018. Interrogating illiberal peace in Eurasia: Critical perspectives on peace and conflict. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Raleigh, C. 2014. Political hierarchies and landscapes of conflict across Africa. Political Geography 42: 92–103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.07.002.

- Reynal-Querol, M. 2002. Political systems, stability and civil wars. Defense and Peace Economics 13, no. 6: 465–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10242690214332.

- Saglam, E. 2021. Taking the matter into your own hands: Ethnographic insights into societal violence and the reconfigurations of the state in contemporary Turkey. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 21, no. 2: 213–230. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2021.1909293

- Scheper-Hughes, N., and P.I. Bourgois, eds.2004. Violence in war and peace: An anthology. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Slinko, E., S. Bilyuga, J. Zinkina, and A. Korotayev. 2017. Regime type and political destabilization in cross-national perspective: A re-analysis. Cross-Cultural Research 51, no. 1: 26–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397116676485.

- Smith, C. 2014. Illiberal peacebuilding in hybrid political orders: Managing violence during Indonesia’s contested political transition. Third World Quarterly 35, no. 8: 1509–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2014.946277.

- Smith, C.Q., L. Waldorf, R. Venugopal, and G. McCarthy. 2020. Illiberal peace-building in Asia: A comparative overview. Conflict, Security & Development 20, no. 1: 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14678802.2019.1705066.

- Somer, M. 2016. Understanding Turkey’s democratic breakdown: Old vs. new and indigenous vs. global authoritarianism. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 16, no. 4: 481–503. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2016.1246548.

- Svolik, M.W. 2019. Polarization versus democracy. Journal of Democracy 30, no. 3: 20–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2019.0039.

- Toros, E., and S. Birch. 2021. How citizens attribute blame for electoral violence: Regional differences and party identification in Turkey. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 21, no. 2: 251–271. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2021.1915642.

- Waldorf, L. 2015. Rwanda’s illiberal peace-building. Africi E Orienti 16, no. 3: 21–34.

- Yilmaz, I., and Barry, J. 2020. Instrumentalizing Islam in a ‘secular’state: Turkey’s diyanet and interfaith dialogue. Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies22, no. 1: 1–16

- Zakaria, F. 2019. The self-destruction of American power: Washington squandered the unipolar moment. Foreign Affairs 98: 10.