Abstract

The way that the media reports and comments on key events in the fragmented global climate governance landscape is one important route to strengthening public accountability of such governance. Editorials and other opinion pieces provide key contributions to the public sphere, but have been almost entirely neglected in media research on climate change. Another understudied aspect in such research is the reporting on the fragmentation of global climate governance across numerous forums. This article provides an exploratory approach to address these two research gaps. It presents a quantitative analysis of how often leading newspapers in seven countries (Finland, India, Laos, Norway, South Africa, UK and USA) wrote about 18 meetings in six different global climate governance forums between 2004–2009 and whether they provided commentaries about them. The study shows that media coverage (articles and opinion pieces) is limited or absent for many meetings that are not attended by heads of state, are the launch of a new process or do not have the convening power of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The pattern of coverage differs significantly among individual newspapers and there is no clear distinction between developed and developing country newspapers. The article concludes that overall news coverage, and editorial commentary in particular, of global climate meetings in the selected newspapers is too low and too patchy to significantly support domestic publics to hold their own (and indirectly other) governments accountable with regard to fragmented global climate governance.

Policy relevance

This study is instructive for the media and civil society, who should both act as accountholders of governments with regard to how they act in global climate governance and its implementation. Reporting and commentaries need to reflect the overarching process, not only sporadic coverage of high-level meetings, but also critical analysis of what is achieved. They should also take a broader scope in terms of the kinds of meetings and processes in global governance that they cover. Civil society should encourage the media to increase coverage along these lines, e.g. by adequate monitoring of government actions (or lack thereof) and share this with the media.

1. Introduction

A new step was taken in global climate governance with the adoption of the Paris Agreement at the twenty-first Conference of the Parties (COP 21) of the United Nations Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in December 2015. Yet it is not the only ‘game in town’. An increasing number of global forums in which climate governance is addressed have emerged from the 2000s (Oh & Matsuoka, Citation2015; Palmujoki, Citation2013; Widerberg & Pattberg, Citation2015; Zelli, Citation2011). This ‘fragmentation’ in global climate governance has included other UN-based forums such as the UN Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD), minilateral initiatives (such as the Asia Pacific Partnership on Clean Development and Climate (APP) launched in 2005, the Major Economies Meetings (MEM) starting in 2007 and the G8, which put climate change high on its agenda in 2005–2009) and initiatives promoting international cooperation on renewable energy, such as the biannual renewables conferences from 2004 onwards. Some of these forums have ceased to exist (the CSD and the APP) but several remain active and come alongside other intergovernmental, private–public and multistakeholder initiatives (Widerberg & Pattberg, Citation2015; Zelli, Citation2011). One gap in the growing literature on the fragmentation of global climate governance is its implications for public accountability.

The way that the media reports and comments on key events in the global climate governance landscape is one important route to strengthening public accountability of such governance. There is a growing literature on climate change in the media but this has largely neglected any analysis of how the media cover different forums of globally fragmented climate governance. This literature has also rarely addressed the volume of editorials and similar opinion pieces that cover global climate governance, despite such articles playing a particular role in forming the public sphere. This article provides an exploratory approach to addressing these two research gaps. Our starting point is the assumption that active media coverage of and media commentary on fragmented global climate governance and governments’ respective actions as part of such governance can be one route to enabling citizens to perform their role as accountholders. Accountability then strengthens both the democratic legitimacy of such governance and keeps the pressure on governments to implement their commitments. This article examines: (1) the degree to which leading newspapers in seven countries (Finland, India, Laos, Norway, South Africa, the UK and the US) wrote about a set of 18 global climate governance meetings in the period 2004–2009; (2) whether they provided editorial commentaries about them; and (3) how media coverage differed between diverse forums.

2. Accountability, fragmented global climate governance and the media

There is a long-standing academic and partly societal debate on the democratic deficit of global governance (Falk & Strauss, Citation2001; Moravcsik, Citation2004; Zürn, Citation2004). The lack of possibility for those governed to hold the governors to account for their actions or lack of actions is frequently seen as a key component of the democratic deficit (Goodhart, Citation2011; Held, Citation2004; Keohane, Citation2006; Scholte, Citation2004). Zürn (Citation2004) sees this as a symptom of what he calls ‘executive multilateralism’ where decision-making on international affairs is primarily made among governmental representatives. There is at best only sparse consultation between the government and the public or between the government and elected representatives about policies on global issues and parliaments therefore have weak oversight of their government’s involvement (Scholte, Citation2002). This does not mean that the domestic societal, ideological and institutional context is not hugely influential on state positions in global governance (Moravczik, Citation1997), but rather that the direct channels of forging a strong accountability relationship between governments and their citizens are weak, even in democracies. These channels are of course even weaker or absent between national publics and the governments of other states whose actions may influence them.

Accountability as a general concept applies to a social relationship between someone who should be answerable for his/her actions (accountee) towards someone else (accountholder).Footnote1 Public accountability can be considered ‘the opportunity of citizens to critically monitor and debate proceedings of political decision-making’ which implies that decision makers (in this case governments) are scrutinized, discussed and criticized in public (Steffek, Citation2010, p. 46). We agree with Steffek (Citation2010) that such public accountability is a necessary condition for the democratization of global governance although this does not negate the important role of other routes for accountability (Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, Citation2015). Furthermore, it is easy to argue that such (domestic) public accountability stands central as states (and their executive governments) have the largest responsibility for determining the outcome of global climate change governance. One important arena for accountability relationships is therefore domestic rather than global – governments in relation to their own citizens.

Two ‘endpoints’ of global climate governance tend to evoke discussions about accountability; when global climate governance is seen as (too) strong or (too) weak from the perspective of those who seek to hold governments to account. Firstly, implementing the kind of commitments that are required to reach the well below 2 °C (or 1.5 °C) target of the Paris Agreement will influence the lives and the economic prospects of many individuals and businesses. Accountability can then for some become an issue of protecting themselves from what they see as abuse of power (Keohane, Citation2006). Secondly, accountability comes to the fore when the international community’s efforts are considered too weak to achieve the goals it has set for itself. In this case the implications for the most vulnerable states and peoples make them take to the streets and use other arenas to hold governments to account for not having yet adopted what they see as sufficiently strong global governance.Footnote2 However, too much or too little governance only provides an output perspective on governance and debates around accountability (and legitimacy) can also emerge from input dimensions – the who and how of the governance processes, including the accountability of the states taking part in them (Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen & Vihma, Citation2009).

The arenas for the public to scrutinize, discuss and criticize their governments for what they do in global climate governance are of course numerous if the public sphere is seen as a ‘network for communicating information and points of view’ (Habermas, Citation1998, p. 360). The media is one of these arenas, and although it is not clear ‘how the mass media intervene in the diffuse circuits of communication in the political public sphere’ (Habermas, Citation1998, p. 378) it is at least expected to provide, in democracies, among other things ‘incentives for citizens to learn, choose, and become involved in the political process’ and ‘[m]echanisms for holding officials to account for how they have exercised power’ (Gurevitch & Blumler, Citation1990, p. 25). However, Moravcsik (Citation2004, p. 344) claims that even in democracies ‘citizens remain “rationally ignorant” or non-participatory with regard to most issues, most of the time.’ The media can thus be seen as an actor of its own, an actor who holds governments to account, but also as an enabler of the public’s role as accountholder. This means that the media’s reporting of the ‘facts’ of global climate governance in the news pages as well as their editorial commentaries on such governance could (or should) play an important role in strengthening the accountability relationship between governments and citizens.

There has been a sharp increase in the concept of the public sphere in media studies (Lunt & Livingstone, Citation2013) and in this literature it has been suggested that the editorial page is ‘one of the few dominant media spaces that allow for lengthy argumentation, presentation of evidence, and wide circulation’ and that ‘whatever other shortcomings traditional journalism has … the editorial page still subscribes to and draws legitimacy from the ideals of the public sphere’ (Squires, Citation2011, p. 31). Nonetheless, there is a dearth of studies on how and how much the media discusses global climate governance, including in editorials, and even more so how it discusses different forums of fragmented global climate governance. Most of the research on climate change in the media has focused on how the media represents climate change and climate change science or to a much lesser degree the factors that influence such representation (Dirikx & Gelders, Citation2010a). The majority of these studies have been made primarily on printed English language media (Boykoff & Timmons Roberts, Citation2007; Painter, Citation2010) with exceptions in Painter (Citation2010), Dirikx and Gelders (Citation2010b) and Lyytimäki (Citation2011), among others. What many of these studies show, however, is a peak in the media interest in climate change at the time of major meetings under the UNFCCC, see Anderson (Citation2009), Boykoff (Citation2011) and Lyytimäki (Citation2011). An exceptional peak occurred for COP 15 in Copenhagen in 2009. This indicates that the politics of climate change is a central focus for the media. Painter (Citation2010) showed this clearly in his analysis of the media coverage in 12 countries of COP 15, where most of the content focused on the drama of the politics rather than the science of climate change. Painter’s study of the media coverage of COP 15 and Boykoff’s study of the media coverage of COP 16 in Cancun are among the few works that collect media items specifically tied to one particular global climate meeting. We have found no studies that compare the media coverage of meetings of different global climate governance forums beyond the UNFCCC. Moreover, there seem to be no quantitative studies that look particularly at editorials and other opinion pieces of global climate governance and that link the analysis of media coverage to the media’s role in enabling accountability relationships between the citizens and governments. This study is provides an exploratory approach to address these gaps.

3. Comparing multilateral and minilateral governance forums

The global climate governance forums included in this study have both a few similarities and several important differences, as summarized in . All forums have an intergovernmental character at their core; states are the major actors. They share the objective of addressing climate change directly or indirectly by promoting low-carbon energy options. They all identify some type of desired actions by states, through norms or action plans. The forums differ along several dimensions that are relevant for their legitimacy and effectiveness including:

The number of states that are taking part – from universal multilateralism in the UNFCCC and the CSDFootnote3 to highly selective minilateralism in the MEM, APP and the G8

Their degree of private sector involvement – from purely intergovernmental (the UNFCCC, the CSD and the G8) to heavy private sector involvement (in the APP and the International Renewable Energy Conferences [IRECs])Footnote4

Their openness to civil society observers and transparency of decision-making processes from non-transparent G8 meetings to the UN-based meetings where observers can attend (except in the most sensitive negotiations)

The type of outcomes they produce, including their ‘hardness’ on the hard–soft law continuumFootnote5 – from hard law in the UNFCCC, to soft law in G8 – while the implementation plans of the IRECs are only self-defined voluntary commitments

The degree of peer monitoring and follow-up of commitments, from very limited in the G8 to obligatory regular national communications under the UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol.

TABLE 1 Key characteristics of global energy and climate governance forums included in the media analysis

The implications of such differences in universality of government participation, openness to private sector and civil society, transparency and review arrangements, as well as the legal character of the outcomes and attention to equity among various global climate governance forums, are subject to scholarly debates through concepts such as legalization (Abbott, Keohane, Moravcsik, Slaughter, & Snidal, Citation2000; Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen & Vihma, Citation2009) and regime complexes (Keohane & Victor, Citation2011). These differences and their implications, however, may not be known by journalists and editors, particularly if the meetings are not attractive enough for coverage in news articles or editorials. Our results indicate indeed that the media does not ‘see’ much of the fragmentation in the global climate change regime complex.

4. Research objectives and methodology

It is clear from the arguments above that the media could (or should) play a substantial role in the accountability relationship between publics and their governments with regards to the actions of the latter in global climate governance. In this article our objective is to explore whether the media actually has the potential to play such a role by looking at how much the media discusses a diverse set of key meetings in a set of different forums of global climate change governance.Footnote6 The potential ability of the media to do so differs between specific forums of global climate governance and individual newspapers in different countries. We approach this objective by addressing three research questions:

1. How much do newspapers write about key meetings of different global climate governance forums?

2. What proportion of the coverage of different global climate governance forums constitute opinion pieces (editorials and other types)?

3. What are the patterns of variation in newspaper coverage of different global climate governance forums and which journals contribute most to them?

Answering the first question gives an idea of the attention that newspapers give to these meetings and thus how much the public that consumes the media is informed about such events and how this differs among different forums in fragmented global climate governance. Answering the second question gives a picture of the degree to which newspaper editors find these meetings important enough to comment on in their editorials or invite commentary on in other types of opinion pieces. Such commentary would reflect a more active role in the accountability relationship between the public and the government. Answering the third question can unveil the consequences of fragmented climate governance for public accountability via the media. It will also enable the identification of further research questions for those studying both the media coverage of climate change and the consequences of this fragmentation of climate governance.

In order to answer these three questions we collected the number of individual opinion pieces as well as news articles that were written about selected global climate change governance events from 2004–2009 from a total of seven newspapers published in seven different countries: Helsingin Sanomat (HS) in Finland, Aftenposten (AP) in Norway, The Times of India (ToI), the Johannesburg Star (JS) in South Africa, The Guardian (Gu) and The Times (TI) in the UK, the New York Times (NYT) and the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) in the US and finally the Vientiane Times (VT) in Laos. More details on these newspapers are given in Table I in the Supplemental data. The countries were selected to cover differences in income levels and political systems as well as position/membership in the global climate change regime. More detailed information on how the selected countries differ on these criteria is given in Table II in the Supplemental data. The selection was also influenced by the language skills of the research team and access to newspaper archives for the major newspaper/s of each country.

We chose to focus on quality newspapers (broadsheets and their modern equivalents) because they tend to have more coverage of climate change and include opinion pieces. This focus on the printed media has limitations, however, as it reaches fewer people and mostly those with a higher education. For example, in the US people rely more on television for political news than on any other medium including the Internet (Boykoff, Citation2012). Furthermore, the role of social media has expanded significantly, making this an important arena for future research.Footnote7 Nonetheless, although newspaper circulation may have decreased ‘dominant print news sources remain significant agenda setters, providing raw materials that are accessed by search engines and re-circulated, linked, posted, and cited by bloggers, facebook users, content aggregators’ (Squires, Citation2011, p. 31). One study showed that 98% of the articles on blogs originated from dominant newspapers and media sources such as the NYT, the BBC and the Washington Post (Gloviczki (2008) quoted in Squires (Citation2011).

The analysis was carried out in the period 2004–2009 for two reasons. First, it is a period that saw unprecedented public and political attention to the issue of climate change, particularly between 2007 and 2009 with the crescendo around COP 15 in Copenhagen. The results therefore provide a ‘high end’ for the role that the media can play in supporting public accountability of governments’ actions in global climate governance. Second, it is a period that included the launch of several multilateral or minilateral forums that discussed action on climate change mitigation and thus expanding fragmentation.

Eighteen intergovernmental meetings in the period 2004–2009 were selected that directly or indirectly related to global climate change governance with a focus on mitigation. The meetings fall into six categories of governance forums with particular characteristics (see ) in the landscape of fragmented climate governance. Table III in the Supplemental data contains a list and brief description of all of the meetings included in the analysis.

The articles included in the sample were identified in the following way. For each meeting a search period that started two days before and ended four days after each meeting was chosen. We then searched for articles in this period that included any of a list of possible key words linked to the meeting in question (name of meeting, location, and ‘climate’, ‘energy’, or ‘CO2’). In special cases (for renewable energy conferences and CSD 15) the additional search phrases ‘renewable energy’ and ‘sustainable development’ were used. Different combinations of the alternative key words were used and the combination that gave the highest number of articles was chosen for manual checking of the content. Those articles that did not mention the meeting in question were then excluded from the sample.

We identified editorials and other opinion pieces that did more than merely report the facts of the meetings on a case-by-case basis as each newspaper had different types of such articles (see Table IV in the Supplemental data for details of the selection criteria). The number of any type of opinion pieces varied considerably between newspapers, with the lowest numbers in absolute and relative terms in the VT and JS.

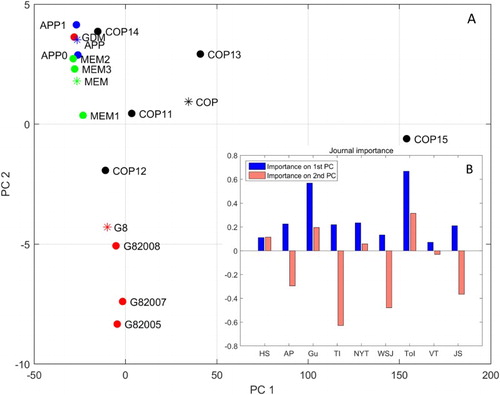

Multivariate statistical analysis of the data was made through analysis of variance (ANOVA) simultaneous components analysis (ASCA) (Smilde et al., Citation2005; Zwanenburg, Hoefsloot, Westerhuis, Jansen, & Smilde, Citation2011). The ASCA proceeds in the following way. First the variation in the data, expressed as the number of articles per newspaper per meeting, is decomposed using one-factor ANOVA. The resulting matrix is analysed using a component model where residuals are projected in a lower-dimensional (2D) space to visualize variability of the data points of the different groups. The loadings provide an interpretation of the relative contribution of, in our case, different newspapers in covering the various types of global climate meetings (see further explanations below).

5. Results

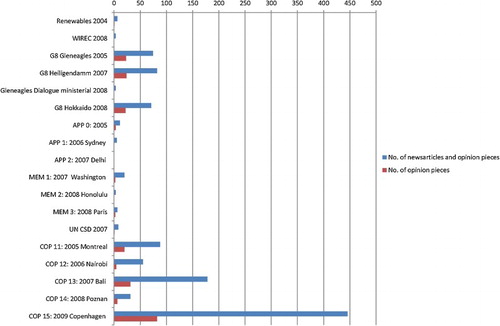

provides an overview of the volume of articles, thus outlining how much the newspapers wrote about key climate meetings (question 1) and how this varied between meetings (question 3). The specific numbers of articles are given in Table V in the Supplemental data. The total number of articles reveals a considerable variety in how much newspapers write about different meetings in various global climate change governance forums. The renewables conferences received very sparse coverage; the meetings were often completely ignored. The G8 Summits that had climate change high on the agenda were given the most coverage in newspapers from the UK and India and from the US in the case of the Hokkaido summit. The MEM and particularly the APP meetings were very sparsely covered and the CSD meeting was only covered in UK newspapers, the AP and VT. The COP meetings of the UNFCCC received by far the most attention.

FIGURE 1 Total number of articles versus the number of opinion pieces per meeting in the selected newspapers

also shows the proportion of opinion pieces and similar style articles with in-depth discussions on the governance process and/or outcome (question 2). It shows how often opinion pieces are dedicated to different types of key meetings. Here the numbers are significantly lower, roughly 10–20% of the total number of articles, and it is only for the meetings of the G8 and the more important COPs that we find any noticeable number of such opinion pieces. Many categories of meetings, such as the renewables conferences, the APP, the MEMs and the CSD are either entirely or almost entirely invisible in the opinion pieces. The only exceptions to this are for the first meeting in a new process.

The total number of opinion pieces in each newspaper is shown in . The variation among the newspapers in the number of total opinion pieces thus varied by about as much as the total number of articles. However, looking at only the number of opinion pieces for the COP 15 meeting, the variation was much higher, ranging from 1 in the VT to 24 in the ToI. The Gu and the ToI were the most active newspapers in contributing to such discussions, and the least active newspapers were HS, the VT and the JS.

TABLE 2 Total number of opinion pieces on global climate change governance meetings per newspaper

The pattern of variation in how much individual newspapers within and between countries wrote about the climate change meetings in total (question 3) was sizeable. Coverage varied from low (41 in the VT and 51 in the HS) to high (216 in the Gu and 257 in the ToI). The variation for the two newspapers within the UK is as big (216 for Gu versus 127 for the TI) as between the two neighbouring countries Finland and Norway (51 for the HS and 101 for the AP). (a) shows the results of the ASCA used to model the variability of newspaper coverage observed for meetings in the four major (in terms of coverage) governance forums: the G8, the UNFCCC/COPs, the APP and MEMs. When points (representing specific meetings) are close to each other in the plot this shows they had similar press coverage. The relative contribution of each newspaper in producing the patterns in coverage (question 3) can be obtained by inspecting the journal’s importance along the two axes that are given in (b). Additional information can be gained from looking at how the coverage of the different meetings is correlated (see figure I in the Supplemental data).

FIGURE 2 Anova-Simultanous Components modeling of press coverage observed for meetings of four global climate governance forums. A) Model score plot: points represent press coverage of individual meetings, stars represent the average coverage for all meetings of one type of governance forum. Points closer in the component space (PC, x- and y-axes) indicate meetings with similar press coverage. B) Model loading plot indicating which newspapers are the most important (relative contribution on x- and y-axis) in causing the differences among meetings observed in panel A

Meetings were spread around the average press coverage profile for a given category, with the exceptions of GDM in the G8 forums and COP 15 in the UNFCCC forum. These two meetings are clear outliers, indicating different press coverage. The COP 15 meeting in Copenhagen generated 446 articles in this study.Footnote8 The record for a single newspaper in this sample was the ToI (141 items). The Gu, with 80 items, is a good second but even the lowest score in the VT of 9 makes one article on average every other day in the analysed period. The GDM attracted only three articles; one from each of the developing country newspapers in the sample.

The Gu and ToI are mostly responsible for the pattern of variation in the coverage of the COP meetings, which spread along the x axis (see PC1 in (b)). These two newspapers had considerably higher coverage of COP 13 in Bali and COP 15 in Copenhagen compared with the other newspapers.

The TI and the WSJ are responsible for most of the variation along the y axis (see PC2 in (b)) and thus among coverage of the MEM, APP and G8 meetings, which each form a clear cluster. However, the JS, ToI and AP also contributed to the variation. The TI wrote three articles each about the launch of both the APP and MEM while the WSJ did not write any articles about the APP, but did publish more than any other newspaper about all three MEM meetings. The WSJ and JS had very similar numbers of articles about the G8 meetings but the JS wrote only once about the APP and MEM, respectively. It is noticeable that a newspaper as big as the NYT falls in the mainstream pattern of coverage of the meetings of the various global climate governance forums together with HS, VT and, to some degree, the AP. The ASCA also shows that there is no clear difference in coverage between the newspapers in developed and developing countries.

6. Discussion

The results show that the media coverage of global climate governance meetings is limited or absent for many of those meetings that: (1) do not draw heads of state like the G8 or COP 15; (2) do not launch a new initiative like the MEM; or (3) do not have the convening power of the UNFCCC. This counts for both newspaper articles and opinion pieces. The poor or absent coverage of many meetings implies that for the public who draws their information from the published media the fragmented character of global climate governance is relatively invisible. The patterns of variation in coverage of the meetings of different forums (through newspaper articles and opinion pieces) can be a reflection of journalists and editors (lack of) awareness of them taking place, or that they considered them of marginal political importance and/or interest to their readers. Such evaluations of importance and interest can be related to a variety of factors. Here we discuss a few plausible factors and how our data illustrates them.

The political views of a newspaper on environmental or equity issues in general can have an influence. In our sample the Gu and ToI had exceptionally high coverage of the UNFCCC COP meetings in particular. The Gu’s prioritization of environmental issues is illustrated by the fact that it doubled its environmental special reporters between 1989 and 2005, in contrast to an opposite trend among newspapers in the US (Painter, Citation2010). The ToI has strongly supported the Indian equity-focused position in global climate governance (Vihma, Citation2011).

The heads of state do attract media attention and our data show clearly that their attendance at G8 Summits and COP 15 correlate with high coverage. However, high-level attendance in the form of ministers did not guarantee coverage; many ministers attended the renewables conferences, the CSD and the GMD, all of which received very sparse coverage. Strikingly, COP 14 – which took place only one year before the big COP 15 – had the lowest coverage of all the COPs included in this study, and yet was a crucial event for the success of the negotiations and had, as all COPs do, ministers attending in the second week.

Newspapers cover news and thus the launching of new initiatives or processes should be attractive to the media. In our data the highest attention was consistently given to meetings that were either launching a ‘new’ policy forum or process (the G8 in 2005 launching the GDM, the first APP meetings and MEMs, COP 13 that launched the negotiations for a new climate agreement and COP 15 that was supposed to see the birth of that agreement) compared with the subsequent meetings in the process.

It is also plausible that newspapers write more about the meetings of a forum in which their country is a member. However, our data is inconsistent in this regard. For example, the UK was a member of the MEM but not the APP. The TI, however, wrote as much about the launch of each of those forums, and indeed the TI together with the HS were the newspapers with the highest number of articles on the APP despite the distance of the UK and Finland from Asia-Pacific. And while the US is a member (indeed an initiator) of both the APP and MEM, the WSJ wrote no articles about the APP meetings but nine about the MEMs. On the other hand, the only newspapers that wrote about the GDM were from developing countries (India and South Africa) who were members of that forum but not of the ‘mother forum’ – the G8.Footnote9

It is reasonable to expect that a country hosting a meeting boosts the media interest in the newspapers of that country. Our data is limited with regards to examining this hypothesis as we do not have newspapers from all of the hosting countries. However, the UK newspapers wrote more about the G8 meetings in the UK and Germany compared with the one in Hokkaido, Japan. The WSJ wrote most about the first MEM meeting, which was hosted in Washington DC.

Finally, other possible factors that can influence coverage are the length and frequency of the meetings. The fact that the COP meetings are two weeks long could lead to more articles compared with the one-day APP meetings or two-day MEMs. On the other hand, our data include COP meetings (COP 12 and COP 14) with lower coverage than G8 meetings by several newspapers. Since almost all meetings were annual, with the exceptions of the bi-annual renewables conferences and the one-off GDM, both of which had very low coverage, frequency does not seem to have an influence.

7. Conclusions

Overall the news coverage, and the commentary on global climate meetings in particular, seems to be too low and patchy to significantly support domestic publics to hold their own (and indirectly other) governments to account with regard to content of fragmented global climate governance. The media attention, including opinion pieces, was concentrated around high-level meetings with heads of state in attendance, such as the G8 and COP 15. In contrast, COP 14 attracted very little attention. And yet the foundation for the inability to reach an agreed outcome at COP 15 had been laid in negotiations over two years that had resulted in a negotiating text of some 200 pages when diplomats arrived in Copenhagen. One could thus say that attention came too late for meaningful debate in the domestic media about the positions of their respective governments on global climate governance and how such governance should look more generally. The attention to the non-UNFCCC meetings without heads of state was, if present at all, only at the launch of a new initiative (APP and MEM) with (almost) no coverage or commentaries on subsequent meetings where one could have evaluated the potential results of the earlier meetings. Unsurprisingly, the media engages more easily with events that can be sold as ‘new’ in some respect compared with either the negotiation meetings preparing for them or subsequent meetings that may scrutinize follow-up. Our data are inconclusive with regard to other possible factors that explain media interest such as membership, hosting of a meeting or the length of the meeting.

Our study was limited to examining whether the media has the potential to hold governments to account either by informing the public of the facts of the meetings or by producing evaluative judgements about these facts. In order to analyse whether they actually do so requires both a content analysis of the newspaper articles, particularly the opinion pieces, but also tracing articles through the years to see if newspapers really follow up on the issues.

Strengthened accountability between domestic publics and government actions in global governance is desirable from the perspective of democracy. There is also an important functional role of such accountability relationships – they provide a means of putting pressure on decision makers and switch governance from ‘the routine mode to the ‘crisis mode’’ (Steffek, Citation2010, p. 47). The media could be expected to play an important part in this accountability relationship if newspaper editors indeed see the media as ‘the “accountability holder” par excellence in society’ as Pimlott (Citation2004, p. 104) claims.

However, the media is not the only route for public accountability. Steffek (Citation2010, p. 59) argues that because media coverage on international policy-making is ‘sluggish’, and because of the very technical character of the issues, the role for civil society − expert NGOs − becomes particularly important as they provide the kind of detailed reporting of the negotiations that most professional journalists cannot provide ‘given the limitations of their general-interest publications’. Their reports may not reach a wider public, but do provide information to experts around the world, including experts in NGOs who can function as translators of information to communities and frame alternatives.

Supplementary figure

Download TIFF Image (1.3 MB)Read all about it supplementary material

Download MS Word (101 KB)Acknowledgement

The authors owe thanks to research assistant Jaakko Otranen, who collected the original data and colleagues at the Public Administration and Policy Group at Wageningen University, for comments on earlier versions of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For a detailed discussion on more institutionalized perspectives (political or legal) on accountability see Bovens (Citation2007) and Mashaw (Citation2007).

2 Examples include the demonstrations held in conjunction with COP 15 in Copenhagen in 2009 (up to 100,000 people, see http://www.unep.org/climatechange/CopenhagenCOP15/Day6/Climatedemonstrationattractsthousands/tabid/2532/language/en-US/Default.aspx) and in conjunction with the Climate Summit at the UN in New York in September 2014 (around 600,000 in more than 2000 locations around the world, see http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-29301969).

3 Formally the CSD had 53 member states on a rotating basis but in practice all states could take part in the meetings.

4 At the UNFCCC and the CSD meetings there is a considerable business and civil society presence, but only as observers; they do not participate in the actual negotiations.

5 For a discussion on the hard–soft law continuum see Abbott and Snidal (Citation2000), Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen and Vihma (Citation2009) and Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen (Citation2011).

6 Analysing whether the media actually does play a role in strengthening accountability requires a content analysis of the media coverage as well as domestic studies of the impacts of the coverage on citizen engagement or government policy.

7 For the period included social media was starting to take off, twitter, for example, was launched in 2006.

8 There were 4000 journalists from 119 countries at COP 15, 85% of them came from the developed world (Painter, Citation2010). Research on the media coverage of climate change in 50 newspapers in 25 countries on six continents shows the highest peak in the covered period (2004–2015) to be at the time of COP 15 (Nacu-Schmidt et al., Citation2015).

9 The APP was launched by the USA and Australia as an alternative and/or complement to the Kyoto Protocol for the global governance of climate change (Zelli, Citation2011).

References

- Abbott, K. W., Keohane, R. O., Moravcsik, A., Slaughter, A.-M., & Snidal, D. (2000). The concept of legalization. International Organization, 54, 401–419. doi: 10.1162/002081800551271

- Abbott, K. W., & Snidal, D. (2000). Hard and soft law in international governance. International Organization, 54, 421–456. doi: 10.1162/002081800551280

- Anderson, A. (2009). Media, politics and climate change: Towards a new research Agenda. Sociology Compass, 3, 166–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00188.x

- Bovens, M. (2007). Analysing and assessing accountability: A conceptual framework. European Law Journal, 13, 447–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0386.2007.00378.x

- Boykoff, J. (2012). US media coverage of the Cancún climate change conference. Political Science & Politics, 45, 252–258. doi: 10.1017/S104909651100206X

- Boykoff, M., & Timmons Roberts, J. (2007). Media coverage of climate change: Current trends, strengths, weaknesses (Human Development Report 2007/2008) [background paper]. New York: United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved from: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/boykoff_maxwell_and_roberts_j._timmons.pdf

- Boykoff, M. T. (2011). Who speaks for the climate? Making sense of media reporting on climate change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dirikx, A., & Gelders, D. (2010a). Ideologies overruled? An explorative study of the link between ideology and climate change reporting in Dutch and French newspapers. Environmental Communication, 4, 190–205. doi: 10.1080/17524031003760838

- Dirikx, A., & Gelders, D. (2010b). To frame is to explain: A deductive frame-analysis of Dutch and French climate online change coverage during the annual UN Conferences of the Parties. Public Understanding of Science, 19, 732–742. doi: 10.1177/0963662509352044

- Falk, R., & Strauss, A. (2001). Toward global parliament. Foreign Affairs, 80, 212–220. doi: 10.2307/20050054

- Goodhart, M. (2011). Democratic accountability in global politics: Norms, not agents. The Journal of Politics, 73, 45–60. doi: 10.1017/S002238161000085X

- Gurevitch, M., & Blumler, J. G. (1990). Political communication systems and democratic values. In J. Licthenberg (Ed.), Democracy and the mass media (pp. 24–35). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Habermas, J. (1998). Between facts and norms. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Held, D. (2004). Democratic accountability and political effectiveness from a cosmopolitan perspective. Government and Opposition, 39(2), 364–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00127.x

- Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S. (2015). Paris and then? Holding states to account. Muscatine, IA: Stanley Foundation.

- Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S. I. (2011). Global regulation through a diversity of norms: Comparing hard and soft law. In D. Levi-Faur (Ed.), Handbook on the politics of regulation (pp. 604–614). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S. I., & Vihma, A. (2009). Comparing the legitimacy and effectiveness of global hard and soft law: An analytical framework. Regulation & Governance, 3, 400–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5991.2009.01062.x

- Keohane, R. O. (2006). Accountability in world politics. Scandinavian Political Studies, 29, 75–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9477.2006.00143.x

- Keohane, R. O., & Victor, D. G. (2011). The regime complex for climate change. Perspectives on Politics, 9, 7–23. doi: 10.1017/S1537592710004068

- Lunt, P., & Livingstone, S. (2013). Media studies’ fascination with the concept of the public sphere: Critical reflections and emerging debates. Media, Culture & Society, 35, 87–96. doi: 10.1177/0163443712464562

- Lyytimäki, J. (2011). Mainstreaming climate policy: The role of media coverage in Finland. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 16, 649–661. doi: 10.1007/s11027-011-9286-x

- Mashaw, J. (2007). Accountability and institutional design: Some thoughts on the grammar of governance. New Haven, CT: Yale University.

- Moravcsik, A. (2004). Is there a ‘democratic deficit’ in world politics? A framework for analysis. Government and Opposition, 39, 336–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00126.x

- Moravczik, A. (1997). Taking preferences seriously: A liberal theory of international politics. International Organization, 51, 513–553. doi: 10.1162/002081897550447

- Nacu-Schmidt, A., Wang, X., Andrews, K., Boykoff, M., Daly, M., Gifford, L., et al. (2015). World newspaper coverage of climate change or global warming, 2004–2015. Retrieved July 3, 2015, from http://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/media_coverage

- Oh, C., & Matsuoka, S. (2015). The genesis and end of institutional fragmentation in global governance on climate change from a constructivist perspective. International Environmental Agreements, Politics, Law and Economics. doi:10.1007/s10784-015-9309-2

- Painter, J. (2010). Summoned by science: Reporting climate change at Copenhagen and beyond. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Palmujoki, E. (2013). Fragmentation and diversification of climate change governance in international society. International Relations, 27, 180–201. doi: 10.1177/0047117812473315

- Pimlott, B. (2004). Accountability and the media: A tale of two cultures. The Political Quarterly, 75, 102–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-923X.2004.00593.x

- Scholte, J. A. (2002). Civil society and democracy in global governance. Global Governance, 8, 281–304.

- Scholte, J. A. (2004). Civil society and democratically accountable global governance. Government and Opposition, 39(2), 211–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00121.x

- Smilde, A. K., Jansen, J. J., Hoefsloot, H. C. J., Lamers, R.-J. A. N., van der Greef, J., & Timmerman, M. E. (2005). ANOVA-simultaneous component analysis (ASCA): A new tool for analyzing designed metabolomics data. Bioinformatics, 21, 3043–3048. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti476

- Squires, C. R. (2011). Bursting the bubble: A case study of counter-framing in the editorial pages. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 28, 30–49. doi: 10.1080/15295036.2010.544613

- Steffek, J. (2010). Public accountability and the public sphere of international governance. Ethics & International Affairs, 24, 45–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7093.2010.00243.x

- Vihma, A. (2011). India and the global climate governance: Between principles and pragmatism. The Journal of Environment & Development, 20, 69–94. doi: 10.1177/1070496510394325

- Widerberg, O., & Pattberg, P. (2015). International cooperative initiatives in global climate governance: Raising the ambition level or delegitimizing the UNFCCC? Global Policy, 6, 45–56. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12184

- Zelli, F. (2011). The fragmentation of the global climate governance architecture. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 2, 255–270.

- Zürn, M. (2004). Global governance and legitimacy problems. Government and Opposition, 39, 260–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00123.x

- Zwanenburg, G., Hoefsloot, H. C. J., Westerhuis, J. A., Jansen, J. J., & Smilde, A. K. (2011). ANOVA–principal component analysis and ANOVA–simultaneous component analysis: A comparison. Journal of Chemometrics, 25, 561–567. doi: 10.1002/cem.1400