ABSTRACT

This article addresses the question of how forestry projects, given the recently improved standards for the accounting of carbon sequestration, can benefit from existing and emerging carbon markets in the world. For a long time, forestry projects have been set up for the purpose of generating carbon credits. They were surrounded by uncertainties about the permanence of carbon sequestration in trees, potential replacement of deforestation due to projects (leakage), and how and what to measure as sequestered carbon. Through experience with Joint Implementation (JI) and Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) forestry projects, albeit limited, and with forestry projects in voluntary carbon markets, considerable improvements have been made with accounting of carbon sequestration in forests, resulting in a more solid basis for carbon credit trading. The scope of selling these credits exists both in compliance markets, although currently with strong limitations, and in voluntary markets for offsetting emissions with carbon credits. Improved carbon accounting methods for forestry investments can also enhance the scope for forestry in the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) that countries must prepare under the Paris Agreement.

POLICY RELEVANCE

This article identifies how forestry projects can contribute to climate change mitigation. Forestry projects have addressed a number of challenges, like reforestation, afforestation on degraded lands, and long-term sustainable forest management. An interesting new option for forestry carbon projects could be the NDCs under the Paris Agreement in December 2015. Initially, under CDM and JI, the number of forestry projects was far below that for renewable energy projects. With the adoption of the Paris Agreement, both developed and developing countries have agreed on NDCs for country-specific measures on climate change mitigation, and increased the need for investing in new measures. Over the years, considerable experience has been built up with forestry projects that fix CO2 over a long-term period. Accounting rules are nowadays at a sufficient level for the large potential of forestry projects to deliver a reliable, additional contribution towards reducing or halting emissions from deforestation and forest degradation activities worldwide.

1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the international climate negotiations in the early 1990s, forests have been considered as a climate change mitigation option. Forests not only produce wood to replace the use of fossil fuels and energy-intensive materials, but they also absorb CO2 from the atmosphere. Despite these climate benefits, investing in forests for climate change mitigation has gained little traction. Forestry projects, with their relatively long time horizons, have long been considered relatively risky investments. As a result, forestry projects were picked up much slower in international carbon markets, such as those under the Kyoto Protocol, or were even excluded from them, such as with the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) of the EU. As a consequence, the main incentives for carbon-related forest activities over the past 5 years did not come from carbon markets, but were provided by over 25 public funds (HBS & ODI, Citation2015) to assist governments in improving their forest management.

Meanwhile, standards for carbon accounting have been developed in the voluntary carbon trading market. These standards have become available for private and public initiatives that are interested in afforestation and forest management investments for climate change mitigation. Recent examples of such initiatives are the New York Declaration on Forests (UN, Citation2014), the Woodland Carbon Code initiative in the UK (Forestry Commission, Citation2015), the forest scope of the Gold Standard (WWF, Citation2015), the Club Carbone Forêt Bois in France (I4CE, Citation2015), and the Bonn Challenge in Germany (Welt Wald Klima, Citation2015).

The main question in this article is: How can forestry projects, given the improved standards for accounting of carbon sequestration, benefit from existing and emerging carbon markets in the world? Section 2 discusses how carbon trading or pricing mechanisms can generate additional investment incentives for low-emission projects, including forestry. Section 3 focuses on current and emerging market opportunities for forestry-based credits. Section 4 discusses the potential role of forestry projects in the implementation of the Paris Agreement. Section 5 concludes with a brief discussion on future opportunities for forestry carbon sequestration projects in international climate policy cooperation.

2. Why it has been difficult for forestry carbon projects to enter carbon markets

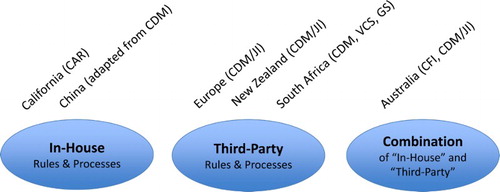

An important rationale for carbon trading is to enable countries or companies with climate commitments to fulfil these cost-effectively. Since GHGs mix evenly in the atmosphere, it does not make any difference for the climate where emission reductions take place. It then makes economic sense to locate emission reductions where investment costs are relatively low. In an ETS, such cost-saving opportunities can be used for trading emission allowances between companies. Each company covered by the ETS has a quota with a maximum amount of allowed emissions per year. A company can comply with its quota by investing in emission reduction measures. However, if the costs of doing so are relatively high, it is economically attractive to purchase allowances from other capped companies, for whom remaining below their caps is easier and thus less costly. According to the International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP, Citation2012), over 14 such ETSs have been established by different countries or regions and their number is expected to double by 2020 (see ).

Figure 1. Three types of international offset programmes, in which forestry projects may be involved in the near future. Adapted after WorldBank (Citation2015).

In the EU ETS, companies can, in principle, also purchase carbon credits based on GHG emission reduction projects outside the ETS. During 2008–2012, EU ETS companies could acquire such credits through the Kyoto carbon credit trading mechanisms Joint Implementation (JI) and Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). Meanwhile, due to strongly reduced EU ETS market prices, the scope for trading project-based carbon credit in the EU ETS has been strongly reduced. Moreover, at the political level in the EU, there is a growing preference to use carbon credits on top of existing climate commitments, instead of offsetting these. Finally, organizations not covered by an ETS could decide to voluntarily ‘offset’ their GHG emissions by purchasing carbon credits from emission reduction projects.

A key requirement for linking (voluntary) climate commitments and carbon credits is that the project-based emission reductions are real and additional. Under the Kyoto Protocol, a comprehensive methodology toolbox has been compiled to guarantee quality of traded credits (UNFCCC, Citation2016a). In principle, forestry projects can be eligible for generating carbon credits for sale on the ETS market. However, their inclusion in ETS schemes around the world has been complicated (or even blocked, such as in the EU ETS) for a number of reasons. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (IPCC Working Group III, Citation2014) has summarized them:

Carbon leakage, which can occur when tree planting or forest protection activity is (partly) counteracted by another activity that results in extra emissions elsewhere.

Permanence: a forest protected or planted during a certain period of time may be subject to clearing during future periods; or replanting of trees after a rotation period has ended is not always guaranteed. Moreover, permanence of sequestered carbon in forests is challenged by the risks of natural forest disturbances (e.g. fires and insects).

Complexity of accounting, in terms of, for example, the capacity of different tree species to store carbon, determining where carbon is sequestered (e.g. soil and trunks), how to account for carbon sequestered in wood after a harvest, as well as handling the differences in terms of carbon accounting between harvesting and avoiding deforestation.

Next to the problematic accounting issues related to forestry carbon projects, slow investments in forestry projects were also caused by political developments during climate negotiations. For instance, when discussing modalities and procedures for CDM projects under the Kyoto Protocol during the early 2000s, several developing countries preferred projects in energy, industrial, and transport sectors, which resulted in a narrower scope for forestry in the CDM (van der Gaast, Citation2015).

As a result of these factors, forestry projects were never able to get a serious market share in JI and CDM markets. For example, as of 1 June 2016, 66 afforestation or reforestation (A/R) projects have been registered by the CDM Executive Board out of 7715 registered CDM projects. For JI, these figures are 3 forestry projects out of 604 registered projects (Fenhann & Schletz, Citation2015; UNFCCC Citation2016b, Citation2016c). Voluntary forest carbon projects also aim for improved forest management (IFM), reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, conservation activities, sustainable forest management, and enhanced carbon sinks (altogether called REDD+). IFM and REDD+ are outside the scope of JI and CDM.

Since the early 2000s, the methodologies for accounting of carbon sequestration in forests have evolved due to experiences with JI, CDM, and voluntary forest projects. Through this evolution, the supply of forestry-based carbon credits has improved in quality. The question that remains is: what are the carbon markets where improved supply of forestry projects can meet the demand for carbon credits? For that, an initial overview of potential carbon markets for forestry projects is presented in the next section.

3. What is the perspective for forestry projects on existing carbon markets?

Internationally, the most important market for carbon credits was created under the Kyoto Protocol, either starting in 2000 via the CDM, or during 2008–2012 via JI. Despite the fact that since the end of the first commitment period of the Kyoto protocol in 2012, the stream of new CDM and JI projects has mostly dried up, the total volume of the JI/CDM market, that is, 1645 Mt CO2 (Forest Trends, Citation2015), is almost 20 times larger than the voluntary market with 87 MtCO2 (Hamrick et al., Citation2015). Nevertheless, as voluntary markets are not directly connected to political decisions, and given the increased awareness among businesses and consumers of climate change issues since the Paris Climate Conference in 2015, they may develop as serious market opportunities for forestry projects. Below, an overview is provided of both compliance-based and voluntary-based carbon markets and how receptive these are for forestry carbon projects, given the improved accounting methods, as explained above.

3.1. Compliance markets

As part of its policy package to comply with the Kyoto Protocol, the EU launched the ETS in 2005 (Directorate General Climate Action, Citation2015). The scheme caps GHG emissions for over 11,000 energy-intensive companies (around 45% of the EU’s total emissions) and allows trade between enterprises to remain below their caps. Allowance prices have fluctuated strongly between over 28€ in 2008 and nearly 3.0€ in 2015, with an average price of 11.3€ per allowance (Fusion Media, Citation2015). The EU ETS has since the start of the economic crisis in 2008 suffered from a structural surplus of allowances with correspondingly low allowance prices.

An important qualitative restriction of the EU ETS is that JI or CDM credits generated through nuclear energy projects, afforestation or reforestation activities, and projects involving the destruction of industrial gases are not eligible for trading on the EU ETS market (European Commission, Citation2004). As such, forestry-based projects could not benefit from the carbon credit market acceleration during 2008–2012, when European companies developed the strongest demand for Kyoto-based carbon credits of any major trading block (WorldBank, Citation2015).

In the future, forest carbon credits could possibly enter the EU ETS through the provision that carbon credits from projects in sectors not covered by the ETS can, in principle, be traded in the ETS market (DG Climate Action, Citation2015). Alternatively or next to that, carbon credits could also be used in the future by Member States to comply with their climate commitments in non-ETS sectors (under the so-called Effort Sharing Decision) (Meyer-Ohlendorf, Citation2016).

Contrary to the EU ETS, the New Zealand ETS, launched in 2008, has included forestry as one of its main sectors. As such, New Zealand is regarded as a trendsetter for carbon trading from forest projects. Other ETSs are being planned, or are in a pilot stage, in Australia, Brazil, China, and South Korea (van der Gaast & Spijker, Citation2013). Whether and how these schemes will provide scope for forestry projects is as of today unclear, given their pilot status. However, the Chinese ETS pilot scheme, currently containing seven regional schemes to be merged by 2017 (ICAP, Citation2012), includes forestry projects as an option. Emission reduction credits from projects outside the scheme, so-called China Certified Emission Reductions, can be traded in the China ETS, to a maximum of 5–10% of the total allowance caps. This also may provide a broader scope for forestry carbon credit projects in China. For instance, in the Beijing ETS pilot, carbon reductions from energy-saving and forest projects can be used as offsets for emissions from companies within the national Chinese ETS (Zhang, Citation2015).

3.2. Voluntary markets

Voluntary markets have been of great importance for forestry as they have been the framework where international accounting methodologies for forest carbon credits, such as those for A/R, IFM, or REDD+, were developed and tested (Kollmus, Lazarus, Lee, LeFranc, & Polycarp, Citation2010). Voluntary carbon schemes have become a stable market for about 2000 current carbon projects (WorldBank, Citation2016). In 2014, forestry project developers, active in voluntary markets, received on average US$4.7 per ton CO2 for REDD+ projects, US$9.1 per ton CO2 for IFM project credits, and US$8.9 per ton CO2 for A/R (Hamrick et al., Citation2015). While the prices are stable, the volume of credits sold has been low: 19 Mt CO2 of forestry-based carbon credits (Hamrick et al., Citation2015). Most of the buyers of voluntary carbon credits (43%) are from the US, followed by the UK (26%) and Germany (13%), representing mostly energy, wholesale, or retail sectors.

Demand on the entire voluntary markets is expected to grow slowly to 200–500 million credits by 2020 (Peters-Stanley & Yin, Citation2013), which could also enhance the prospects for forestry-related projects, especially with the increasingly enhanced quality of carbon accounting for this type of project. As explained in DEHSt (Citation2015), several European countries are currently developing private and public offsetting schemes in their non-ETS sectors, such as the Woodland Carbon Code in the UK and a proposed Green Deal (for developing a national carbon market system) in the Netherlands, with forestry among the project options.

3.3. Enhanced market perspectives through improved carbon credit accounting

Notwithstanding the slow start of forestry projects on international carbon markets, especially those for supporting compliance with ETS and Kyoto Protocol commitments, future prospects of forestry carbon credit projects seem to have improved. When focusing solely on the issues of carbon leakage, permanence, and accounting complexity, considerable improvement in methodologies and safeguards has been achieved, including approved GHG accounting methodologies for large-scale A/R projects by the CDM Executive Board (UNFCCC, Citation2016a). A closer look at these methodologies shows that the main accounting issues they need to address are in line with the discussion by the IPCC (IPCC Working Group III, Citation2014, see above) and which relate to defining sequestration sources in forests, leakage, and addressing temporary storage of carbon in forests and in harvested wood products.

For use in voluntary markets, carbon accounting methodologies for forestry projects have been developed and applied by a range of organizations, such as Gold Standard and Verified Carbon Standard (Chia, Fobissie, & Kanninen, Citation2016; Hamrick et al., Citation2015; Held, Tennigkeit, Techel, & Seebauer, Citation2010; Peters-Stanley & Yin, Citation2013). With these improved methods for clearly checking the additionality of emission reductions or carbon sequestered, leakage and handling permanence, external validation of the forestry project plans, and external verification of the project results can be carried out much more thoroughly than before.

4. Has the Paris Agreement opened a new window of opportunities for forestry projects?

The Paris Agreement, as adopted at the 21st Conference of Parties (COP-21) in 2015 (UNFCCC, Citation2015), set a long-term objective of decarbonized economies for limiting global average temperature increase by 1.5°C or 2°C (compared to pre-industrial time levels). For that, countries shall communicate national climate plans (‘Nationally Determined Contributions’ or NDCs), which will be subject to international review (‘global stocktaking’). By their nature, NDCs are not directly linked to carbon credit trading. Contrary to the quota for industrialized countries in the Kyoto Protocol, which were eligible for trading, NDCs are not based on national, quantified GHG emission targets, but on nationally determined voluntary mitigation actions (self-commitments), which could take several different forms such as technology innovation, subsidy schemes, sector-level targets, etc.

As NDCs will contain preferred actions for countries to meet climate goals in light of national socio-economic plans, there could be scope for including forestry projects among the mitigation actions in an NDC. For example, REDD+ action could form part of NDCs as potential emission reduction sources (Climate Focus, Citation2015). Relevant to and potentially stimulating for forests and land-use activities are the criteria and rules agreed in Paris for NDCs, in particular the frequent references to ‘removals by sinks of greenhouse gases’ as an option for mitigation, when specifying NDCs in further detail (UNFCCC, Citation2015).

There has been a lively discussion on the contribution of ‘Land use (change) and forestry' (LUCF) activities to meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement (UNFCCC, Citation2015). As an indication, 119 intended NDCs were communicated by countries before COP-21. Among others, two inventories (Climate Focus, Citation2015; Grassi & Dentener, Citation2015) concluded that forestry and land-use actions could become important mitigation options in post-2020 climate plans (NDCs). As a result, forests and land-use activities could turn globally from a net source of carbon emission, as was the case during the period 2000–2010, to a net sink of carbon by 2030, that is, carbon sequestration by forests becomes larger than carbon release from forests. By then, forestry and land-use could provide for about a quarter of planned emission reductions globally (Grassi & Dentener, Citation2015).

While REDD+ forest projects are potential mitigation options for inclusion in NDCs, also forestry-related carbon trading could be eligible under NDC, via so-called internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (articles 6.2 and 6.3 of the Paris Agreement). Especially for the latter, proper carbon accounting will remain an important requirement, which has recently been emphasized at a technical UNFCCC working group meeting in Bonn in May 2016 (IISD, Citation2016). At that meeting, countries stressed the importance of avoiding double counting and ensuring environmental integrity for carbon accounting. In light of that, forestry project investments, given the improved carbon accounting methodologies as discussed above, are nowadays better equipped for full eligibility for carbon credit trading under the Paris Agreement.

5. Conclusion

While forestry is potentially an important area for reducing global GHG emissions, forestry projects have had a relatively small share in the international markets for trading emission reduction credits. Reasons for this mismatch between theoretical potential and practical implementation are related to risks and uncertainties that have long surrounded forestry projects, such as leakage, how long once sequestered carbon will remain in the trees, how to precisely determine and monitor the size of the carbon sinks in a forests, and how to handle specific risks, such as forest fires and insect plagues.

At the same time, especially because of activities in the voluntary markets, big steps have been made in improving the methodologies for carbon accounting in forestry projects, especially with respect to addressing uncertainties and mitigation risks. With these methodologies, forestry projects are now better equipped for entering existing and emerging compliance and voluntary markets at a scale that does justice to the potential role of forest activities in meeting climate and national socio-economic and environmental development goals.

An interesting new option for forestry carbon projects could be the NDCs under the Paris Agreement in December 2015. Given that NDCs will be assessed, among others, against their contribution to GHG emission reductions below business-as-usual scenarios, the improved methodologies for carbon sequestration could make tradeable credits from forestry projects better suitable as mitigation options in NDCs than they were during the early days of carbon market development in the 1990s and under the Kyoto Protocol.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Giacomo Grassi (Joint Research Centre), Edwin Aalders (DNV GL), James Schadenberg (Control Union Certifications), and one EU governmental expert for their expert views on post-Kyoto developments and Tracy Houston Durrant (Joint Research Centre) for checking the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Wytze van der Gaast http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8782-180X

Richard Sikkema http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0954-3469

References

- Chia, E. L., Fobissie, K., & Kanninen, M. (2016). Exploring opportunities for promoting synergies between climate change adaptation and mitigation in forest carbon initiatives. Forests, 7, 1–16. doi:10.3390/f7010024

- Climate Focus. (2015). Forests and land use in the Paris agreement. The Paris agreement Summary. 22 December 2015; 28 December 2015. Retrieved February 19, 2016, from http://www.climatefocus.com/publications/cop21-paris-2015-climate-focus-overall-summary-and-client-briefs

- DEHSt. (2015). Domestic carbon initiatives in Europea. Workshop 19 June 2015. Berlin: Author.

- DG Climate Action. (2015). The EU emissions trading system (EU ETS). Retrieved December 10, 2015, from http://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/ets/index_en.htm

- European Commission. (2004). Amending directive 2003/87/EC establishing a scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the community, in respect of the Kyoto protocol’s project mechanisms. Official Journal of the European Union, L338, 18–23.

- Fenhann, J., & Schletz, M. (2015). Welcome to the UNEP DTU CDM/JI pipeline analysis and database. UNEP/Danish Technical University (DTU). Retrieved December 10, 2015, from http://www.cdmpipeline.org/

- Forest Trends. (2015). Forest carbon portal (FCP). Retrieved June 5, 2015, from http://www.forestcarbonportal.com/project/

- Forestry Commission. (2015). UK Woodland carbon code. Retrieved September 24, 2015, from http://www.forestry.gov.uk/carboncode

- Fusion Media. (2015). Carbon emissions historical data. Retrieved December 4, 2015, from http://www.investing.com/commodities/carbon-emissions-historical-data

- van der Gaast, W. P. (2015). International negotiation conditions – past and present (PhD thesis). University of Groningen (RUG).

- van der Gaast, W. P., & Spijker, E. (2013). Biochar and the carbon market. Retrieved from http://jin.ngo/publications/11-publications/158-biochar-and-the-carbon-market.

- Grassi, G., & Dentener, F. (2015). Quantifying the contribution of the land use sector to the Paris agreement. JRC science for policy report. EUR 27561.

- Hamrick, K., Goldstein, A., Thiel, A., Peters Stanley, M., Gonzalez, G., & Bodnar, E. (2015). Ahead of the curve. State of the voluntary carbon markets 2015. Ecoystem marktplace (Forest Trends). Retrieved September 24, 2015, from http://forest-trends.org/releases/uploads/SOVCM2015_FullReport.pdf

- HBS & ODI. (2015). Climate funds update. Author. Retrieved September 22, 2015, from http://www.climatefundsupdate.org/listing

- Held, C., Tennigkeit, T., Techel, G., & Seebauer, M. (2010). Analysis and evaluation of forest carbon projects and respective certification standards for the voluntary offset of GHG emissions. Climate change. Bonn: Umwelt Bundesamt.

- I4CE. (2015). Programme de recherche – Territoires & climate. Author. Retrieved September 24, 2015, from http://www.i4ce.org/go_project/club-carbone-foret-bois-2/

- ICAP. (2012). Emission trading schemes (ETS) map. Retrieved September 10, 2015, from https://icapcarbonaction.com/ets-map

- IISD. (2016). Summary of the Bonn climate change conference: 16–26 May 2016. Environmental Negotiations Bulletin, 12(676), 1–26.

- IPCC Working Group III. (2014). Carbon offsets, tradable permits, and leakage working group III. Mitigation. Retrieved June 29, 2016, from https://www.ipcc.ch/ipccreports/tar/wg3/index.php?idp=174

- Kollmus, A., Lazarus, M., Lee, C., LeFranc, L., & Polycarp, C. (2010). Chapter 7 voluntary offset standards. In A. Kollmus et al. (Eds.), Handbook of carbon offset programs. Trading systems, funds, protocols and standards (p. 66). London: Earthscan.

- Meyer-Ohlendorf, N. (2016). Proposals for reforming the EU effort sharing decision. Berlin: Ecologic Institute.

- Peters-Stanley, M., & Yin, D. (2013). Maneuvering the mosaic – state of the voluntary carbon markets 2013. Forest Trends and Bloomberg New Energy Finance, Washington DC.

- UN. (2014). Forests, action statements and action plans. Author. Retrieved September 22, 2015, from http://www.un.org/climatechange/summit/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2014/07/New-York-Declaration-on-Forest-%E2%80%93-Action-Statement-and-Action-Plan.pdf

- UNFCCC. (2015). Adoption of the Paris Agreement. Proposal by the President. FCCC/CP/2015/L.9/Rev.1. Retrieved January 4, 2016, from http://unfccc.int/documentation/documents/advanced_search/items/6911.php?priref=600008831

- UNFCCC. (2016a). CDM methodologies; small scale and large scale afforestation and reforestation. Retrieved February 2, 2016, from https://cdm.unfccc.int/methodologies/index.html

- UNFCCC. (2016b). JI project overview. Retrieved June 1, 2016, from http://ji.unfccc.int/JI_Projects/ProjectInfo.html

- UNFCCC. (2016c). Projects search. CDM Executive Board. Retrieved June 1, 2016, from http://cdm.unfccc.int/Projects/projsearch.html

- Welt Wald Klima. (2015). World forest foundation standards and project criteria. Retrieved September 24, 2015, from http://worldforestfoundation.de/index.php?id=44

- WorldBank. (2015). Options to use existing international offset programs in a domestic context. PMR Technical Note 10. Partnership for Market Readiness, World Bank, Washington, DC. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO. Retrieved September 22, 2015, from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2015/08/24957603/options-use-existing-international-offset-programs-domestic-context

- WorldBank (2016). States and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2016, WorldBank, Ecofys, Vivid Economics, Washtington, D.C., USA.

- WWF. (2015). Gold standard – A/R requirements. Retrieved September 24, 2015, from http://www.goldstandard.org/resources/afforestation-reforestation-requirements

- Zhang, Z. X. (2015). Carbon emissions trading in China: The evolution from pilots to a nationwide scheme. Climate Policy, 15(S1), S104–S126. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2015.1096231