ABSTRACT

Flood risk is increasing across the world due to climate change and socio-economic development, calling for a shift from traditional protection and post-event activism towards a forward-looking, risk-aware, and more holistic resilience approach. The national legal system of countries can play an important role in creating and encouraging such a shift. In this study, we explore the potentials and shortcomings of national laws in managing flood risk and increasing flood resilience in the context of climate change. We analyze 139 laws from 33 countries collected from the Climate Change Laws of the World and Disaster Law databases and underpin this with case studies to gain insights on the interplay between national laws and resilience processes. We find: (1) a shift in flood laws from focusing on flooding as a natural resource and water resource management issue towards a broader consideration of disaster risk management (DRM) and climate adaptation policy; (2) a significant lack of climate change recognition in laws regulating decisions and actions for future flood risks, especially in DRM; (3) a prevailing focus on response and recovery strategies and a lack of recognition of risk reduction strategies and proactive flood risk governance approaches; and (4) little recognition of natural capital (comparing to physical capital) and its role in increasing flood resilience.

Key policy insights

Flood-related laws around the world lack consideration of future risks. Disaster risk management and climate change are often considered as separate issues in national laws, which can lead to gaps in institutional ownership, responsibilities, and allocated budgets.

Flood-related laws are mainly created after major events, most of which are focused on reactive strategies (i.e. response and recovery). Laws can facilitate the shift from post-event response to anticipatory actions by encouraging proactive flood risk management (FRM) activities (i.e. risk reduction).

Nature-based solutions often remain unrecognized in national laws due to the dominant focus on hard engineering measures. FRM should be treated as a holistic concept in laws: ensuring all the necessary human, social, physical, natural and financial systems are in place to support it.

1. Introduction

Floods affect more people around the world than any other hazard (Aerts et al., Citation2018; Hanger et al., Citation2018; UNISDR, Citation2015). In many places across the world risk levels are increasing, with climate change and socio-economic development influencing risk patterns and exposure (De MoeL et al., Citation2011; IPCC, Citation2018; Nicholls et al., Citation2008). Particularly for many low-lying parts of the world, flood prospects look daunting given the interplay of sea-level rise, changing rainfall patterns and continued urban development in high-risk areas (Kulp & Strauss, Citation2019). In the face of these threats, a rethink in flood risk management (FRM) is required along three lines: (1) taking account of future risks and impacts of climate change; (2) integrating forward-looking and proactive approaches; and (3) employing a variety of strategies and measures to reduce and manage risks, including spatial planning, community planning, and natural FRM measures, rather than merely focusing on defence and protection measures (Dieperink et al., Citation2016; Keating et al., Citation2014).

The importance of mainstreaming climate adaptation into other policy areas is probably most evident in the context of flooding, where a disregard of future risk drivers can lead to expensive lock-ins, as highlighted, for example, in the UK Climate Change Risk Assessment 2017 (Adger et al., Citation2018). Forward-looking risk reduction and climate adaptation are, thus, important in building the resilience of communitiesFootnote1 to the impacts of extreme weather and long-term changes. Building climate resilience needs to be an essential component of current and future development planning to ensure that previous gains in poverty reduction and economic prosperity are not cancelled out by adverse climatic impacts (Surminski et al., Citation2016; Mechler & Hochrainer-Stigler, Citation2019). The concept of resilience has received significant attention recently, becoming a widely recognized part of public and private initiatives on climate risks.Footnote2 In parallel, there has been substantial discussion on the meaning, nature, and implications of resilience in the literature (Bahadur et al., Citation2010; Béné et al., Citation2012; Schipper & Langston, Citation2015) including its shifting conceptions from ‘bounce back’ to ‘bounce forward’ (Peel & Fisher, Citation2016) and also on the role of legislation for social-ecological resilience (Ebbesson & Hey, Citation2013; Garmestani et al., Citation2013; Garmestani & Allen, Citation2014).

However, what is less clear is whether existing FRM regulatory approaches are being adjusted or extended to incorporate a forward-looking resilience approach. While more decision-makers recognize the importance of resilience as a concept, the management of flood risk remains a reactive process, still mostly driven by post-event activism rather than strategic and forward-looking planning (Surminski & Thieken, Citation2017; Tingsanchali, Citation2012). One area that remains largely unexplored is the influence of laws on the nature of FRM, particularly on the ability to increase flood resilience in the context of climate change. Against this background, this paper analyzes national laws dealing with flood issues, with a view to highlighting their potentials and shortcomings for managing flood risk and enhancing flood resilience for communities.

The formal legislative system of countries plays an important role in setting out rules and frameworks for flood risk governance. These tend to regulate (prohibit, obligate or permit) flood-related decisions, actions and responsibilities. National level lawsFootnote3 are employed to support the integration and coordination of local and national disaster risk management (DRM) practices and the proper distribution of resources among different sectors and institutions. Moreover, they create specific accountabilities and liabilities for public officials, private sectors and societies in terms of FRM activities (Alexander et al., Citation2016a). As such, national flood laws can play a significant role in shaping how flood risks are managed. For example, Arnold (Citation1988), Hartmann and Albrecht (Citation2014), England (Citation2019), Spray et al. (Citation2009), Gilissen (Citation2015), and Howarth (Citation2002) look at the influence of national laws on the trends of FRM in the US, Germany, Australia, Scotland, Netherlands, and England and Wales, respectively. There are also legal studies on other sectors related to flood e.g. national water laws (Crase et al., Citation2020; Hobbs, Citation1997; Howarth & McGillivray, Citation2002; Van Rijswick et al., Citation2012) and environmental laws (Howarth, Citation2017; Stallworthy, Citation2006; Thornton, Citation2018). However, most of such studies are fragmented, limited in scope and country specific. What seems lacking is therefore a global overview of the flood-related national laws across various countries.

The closest global legal studies that cover some aspects of flood legislation are those focusing on Disaster Risk Management (DRM)/Reduction (DRR) and climate change adaptation, which have mainly emerged over the last two decades (Mercer, Citation2010; Thomalla et al., Citation2006). For example, the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) have jointly assessed the DRM laws of 31 countries and identified the factors that have supported or hindered the implementation of DRR activities within these laws (IFRC and UNDP, Citation2014). Moreover, the question about forward-looking laws and policies, and recognition of climate change, has offered a new perspective to study risk governance: Averchenkova et al. (Citation2017) and Nachmany et al. (Citation2017) studied the climate change laws of the world and showed a twentyfold increase in the number of national climate change mitigation and adaptation laws within twenty years. However, these studies illustrate the lack of integration of climate change laws into mainstream development strategies of the countries analyzed. Olazabal et al. (Citation2019) presented the most up-to-date database of the climate change adaptation policies at national, regional/state and local level across 68 countries and 136 coastal cities. Their analysis showed that coastal adaptation legislation is relatively recent and is concentrated in developed countries.

There is also growing research on analyzing the relationships between national and local climate adaptation policies and strategies. Heidrich et al. (Citation2016) analyzed climate change policies of 200 European cities and found that the number of cities with mitigation and adaptation strategies is larger in countries where a national law requires municipalities to prepare urban climate strategies. Reckien et al. (Citation2018) reviewed the local climate plans of 885 European cities and showed that cities that are in countries with national climate legislation are five times more likely to produce local adaptation plans.

Despite all these studies, there is still little evidence on how national legislation is currently encouraging or constraining decisions and actions to build flood risk adaptation and resilience across different countries. In this paper, we address this knowledge gap by investigating the following three research questions:

(1). What are the types of national laws currently used to shape and influence FRM, what are their objectives and focus areas, which mechanisms are used, and whom do they target?

(2). How do laws capture the temporal challenges of FRM, in particular changing risk levels due to climate change, and are laws designed reactively or proactively, focusing on the post or pre-disaster aspects?

(3). What roles do national laws play for community-level resilience, given that FRM and adaptation action need to be local?

To obtain insights on these questions we have collected and analyzed the national laws of 33 flood-prone countries and underpinned this with expert interviews and household surveys conducted via the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance (ZFRA, https://floodresilience.net/). One should note that this analysis does not aim to evaluate the quality of laws nor their implementation. Rather, it aims to provide insight into how the concepts of adaptation and resilience can be applied in national level legislation mechanisms to influence decision making for flood risk reduction.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the methodology and framework used in this study, while section 3 elaborates on the results of the legal analysis in three sub-sections corresponding to the three research questions of this paper. Finally, section 4 discusses the main outcome of this study and concludes.

2. Methodology

A mixed-methods approach has been used in this study. As the first step, we collected a dataset of national laws in 33 countries in collaboration with the research group Climate Change Laws of the WorldFootnote4 at the London School of Economics (LSE) and Disaster Law Footnote5 at the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). The resources used for the data collection and methodology used for the selection of relevant laws are explained in Supplementary Information A. We then conducted an overarching desk-study and content analysis of the laws identified and validated our results with local expert knowledge.Footnote6 This method has been used for analyzing research questions one and two. The detailed methodology for the legal textual analysis is explained in Supplementary Information A.

Countries have been selected based on three criteria: (1) top 10 countries in terms of the population exposed to river flooding as per Aqueduct Global Flood Analyzer, (2) top 10 countries in terms of the population exposed to coastal flooding as per Climate Central, and (3) countries identified as vulnerable to flooding as per ZFRA. This selection criteria led to a set of 28 countries. Additionally, to represent a distribution of countries with different socio-economic development backgrounds, we added five OECD countries that have recently been subject to flood risk governance analysis under the EU’s STARFLOOD (2016) project – Belgium, France, Sweden, Poland – and an ongoing flood risk governance investigation by the Geneva Association – Canada. The full list of the 33 countries and their selection criteria can be seen in and .

Table 1. 33 countries and the selection criteria for each country.

Secondly, for research question three, we conducted five deep-dive case-studies analyzing the laws of five countries through the lens of a ‘community flood resilience’ framework developed and implemented under the ZFRA, and supplemented this with local expert discussions.

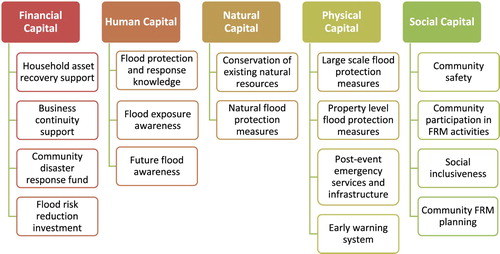

A communityFootnote7 flood resilience framework has been developed for measuring and assessing the flood resilience of communities across the world (Keating et al., Citation2017). In this framework, flood resilience is defined based on the five types of capital i.e. financial (economic assets and financial support), human (knowledge, awareness and skills), natural (ecosystems and eco-services), physical (basic infrastructure and physical protection measures) and social (social networks and public participation) (Campbell et al., Citation2019; DFID, Citation1999; Keating et al., Citation2017; Magnuszewski et al., Citation2019) – see . In this framework, the five forms of capital demonstrate the capacity for communities to avoid the creation of new risks, reduce existing risks, prepare for future risks and improve their response to, and recovery from, a flood event. Each form of capital includes a set of indicators resulting in 44 indicators of community flood resilience – shown in Supplementary Information A. To our knowledge, this is the only framework developed for assessing ‘flood resilience’ at the ‘community-level’ and being used in various countries across the world. We use the indicators within this framework to investigate how and to what extent community-level resilience is addressed in the national laws of the five cases studies.

Figure 2. An overview of the community flood resilience framework and the simplified categories of indicators for each capital. For the complete list of 44 indicators see Supplementary Information A.

Due to the exploratory nature of research question three, the five case-study countries were chosen to cover a diverse range of economic and human development contexts (i.e. developed vs developing countries), political systems (i.e. federal states vs unitary states), government systems (i.e. presidential, parliamentary, and constitutional monarchies), and different geographical locations (i.e. Asia, Europe, and America). These are Bangladesh, Indonesia, Nepal, United Kingdom (UK), and the United States (US).

Here, we acknowledge that any study of this kind comes with some limitations: Firstly, this study does not assert whether a country needs national laws, nor does it provide a comparison among countries based on the number and quality of laws identified. Instead, we conduct a stock-take and investigate the overall shortcomings and potentials of existing laws in terms of current and future flood risk and resilience. We acknowledge that the use of legislation systems depends on political systems, the general structure of government and governance culture of countries, and therefore, the lack of laws for an issue such as flooding cannot automatically be interpreted as lack of flood governance—in federal systems, for example, there is often very little or no national-level legislation. Similarly, in some countries, the executive route to decision making might dominate, with very little use of legislation in areas such as disaster, flood and climate change. Therefore a more comprehensive assessment of the countries’ regulatory responses to flood risks would need to take into account legislation as well as executive policies and strategies (Nachmany et al., Citation2019).

Secondly, the focus of this study is on primary lawsFootnote8 but we acknowledge that those alone are not the only foundations and determinants of flood-related decision making. Yet, primary laws play an important role in fostering collaboration, partnership and proper distribution of resources across governance scales and sectors, and geographical locations.

Finally, this study focuses on the laws that explicitly include flood, adaptation and/or natural disaster/hazard in their text (see Supplementary Information A for the terms used for collecting laws). We do not consider laws that may have an indirect impact on flood risk and resilience if they do not explicitly address a type of flood, adaptation or natural disaster/hazard. Therefore, the analysis and results of this paper are based on the laws that tend to directly influence decisions and actions related to FRM.

3. Results

Overall, across the 33 countries investigated, we identified and analyzed 139 laws that exist in 30 countries (see Supplementary Information B for the full list of the laws). In Belgium, Nigeria and Egypt no national laws related to flood exist. Importantly, these three countries show flood-related policies and strategies across national and local levels, for example, Egypt’s National Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change and DRM 2011, and Nigeria’s National Erosion and Flood Control Policy 2011 and National Policy on Climate Change and Response Strategy 2013 (Osumgborogwu & Chibo, Citation2017). Belgium, in turn, is an example of a federal government system, where the governance and responsibility for FRM sit within the three distinct regions of Brussels, Flanders and Wallonia, and not with the federal government (Mees et al., Citation2016, Citation2018). This means that, while there is no national law on flood or climate adaptation in Belgium, flood risk governance is organized through many regional regulations for flood and coastal risk management in these three regions (Castanheira et al., Citation2017). Therefore, it is important to note that the number of laws in each country does not imply the quality of legal responses to flood risks in that country. Some countries, for example, may have one comprehensive DRM law that covers various aspects of FRM, whereas others may have many laws or policies/regulations from various sectors that each touch upon elements of FRM. That being explained, we present the results of our analysis based on individual laws and not as a comparison of individual countries.

3.1. Typology of national laws

This section will look at the typologies of laws in terms of their objectives and focus areas, the mechanisms used and the actors they target.

3.1.1. Objectives and focus areas

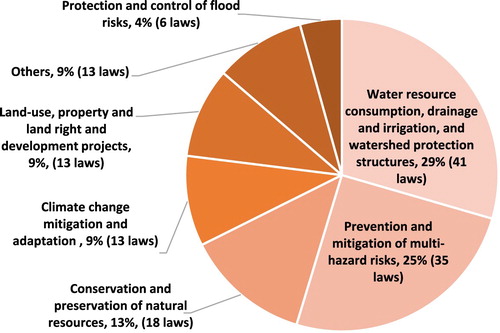

Analyzing the 139 laws shows a variety of underpinning objectives aimed at different policy areas. Most laws are either focused on water resource management (29%) or wider DRM (25%). The rest of the laws are focused on natural resource management (13%), climate change adaptation (9%) and land use and spatial planning (9%). Only 4% of laws are specifically focused on FRM strategies (). In terms of specific focus areas, we find that:

Water resource management laws are mainly about issues related to the water resource consumption, improving drainage systems and building watershed protection measures such as embankments and flood walls alongside the rivers e.g. water acts of Afghanistan (2009), Bangladesh (2013), China (1988), France (1992), Germany (2009), Honduras (2009), Indonesia (1974), Montenegro (2007), Poland (2001), and UK (2014).

Disaster risk management laws cover issues related to the protection, mitigation and reduction of multi-hazard risks e.g. the DRM acts of Bangladesh (2012), India (2005), Indonesia (2007), Myanmar (2013), and Pakistan (2010).

Flood risk management laws are specifically about protection, prevention and control of flood risks such as the German Act to Improve Preventive Flood Control (2005) and the US Flood Disaster Protection Act (1973).

Natural resource management laws are about issues concerning conservation and preservation of the natural resources (non-water resources) that may protect communities against flood (such as natural areas and agricultural lands alongside the rivers) e.g. Albanian Law on Protected Areas (2017), French Law for Reclaiming Biodiversity, Nature and Landscapes (2016), and Nicaraguan General Law on the Environment and Natural Resources (2014).

Land-use and spatial planning laws are related to management, planning, and governance of land-use, development projects and property/land rights e.g. Law about Spatial Planning in Indonesia (2007) and The Building and Planning Act of Sweden (2010).

Climate change laws focus on strategies and actions for improving adaptation and mitigation mechanisms e.g. Climate Change Acts of Philippines (2009), Mexico (2012), New Zealand (2002), and Nicaragua (2009).

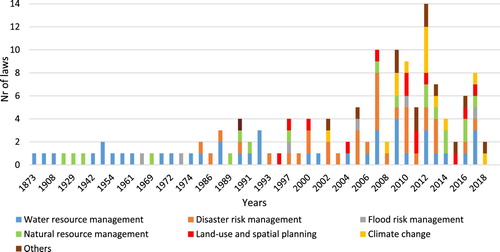

A historical overview of the 139 laws explains why most laws influencing FRM are water and resource management laws. shows that before 1980, rules and regulations for flooding were traditionally set by water and natural resource management laws. This can perhaps be explained by the argument that disaster risk governance, across the world, had been situated within environmental and natural resource governance for a long time (Lemos & Agrawal, Citation2006; Tierney, Citation2012) following policies, regulations, decisions and actions that tended to be based on a conservation, preservation and restoration paradigm (Clarvis et al., Citation2014). In such a paradigm, ecosystems and natural hazards are both assumed to be predictable and therefore can be protected from external drivers (Clarvis et al., Citation2014; Craig, Citation2010). Since the 1980s, we see an emergence of laws related to DRM/DRR and eventually also climate adaptation, as well as laws from other sectors such as spatial planning and finance influencing FRM, which consider flood not only as a nature-based disaster that comes from rivers overflowing but also as a human-caused disaster that can be prevented, mitigated, and adapted to by communities.

Figure 3. Overview of the primary issue areas of the 139 laws identified as relevant for FRM in 30 countries.

Figure 4. The publication year of 139 laws. Note that this figure shows the creation year of the laws and not their revision years, and that the years on the X axis are only the year in which laws are created and thus have different intervals, e.g. the gap in creation of new laws significantly decreases from 2000 onwards.

3.1.2. Mechanisms used by laws

Across the laws analyzed we can identify five main types of mechanisms through which the laws intend to influence the way floods are managed. In most of the cases, the laws encompass a combination of these mechanisms (see Supplementary Information B for a full list of mechanisms used in each law):

(1). Setting up a new government body: 28% (nr=39) of laws create or mandate the creation of a department, committee, board, council, institute, or association that has FRM as part of its tasks, and establishes their functions, responsibilities and funding sources. For example, River Research Institute Act of Bangladesh (1990), Risk Assessment Act of Germany (2002), and Council of Research in Water Resources Act of Pakistan (2007) create research institutes to develop models, maps or databases, disseminate information for the public and advise the government on flood risk decision making.

(2). Establishing or clarifying roles, responsibilities and rights related to FRM activities: 71% (nr=100) of laws define responsibilities, powers and rights either within the new bodies created in the law or among the existing government and non-government bodies and actors. The UK Flood and Water Management Act of 2010, for instance, creates structures and responsibilities for FRM in the UK and improves local leadership by giving power to local and county authorities.

(3). Establishing or mandating the creation of a national, regional or local regulatory document: 41% (nr=57) of laws establish or mandate creation of a strategy, vision, policy, plan, regulation, assessment, criteria or guideline for FRM at the national, regional and local levels. The National Environmental Policy Act of the US (1969), for instance, outlines national environmental policies that prohibit the support of floodplain developments. The DRM Act of Bangladesh (2012) also mandates DRM committees to formulate local DRM plans based on their areas and local hazards.

(4). Mandating or regulating the implementation of specific projects, actions, or interventions: 13% (nr=19) of laws regulate the implementation of specific flood-related projects such as the construction, maintenance, management, and control of the flood defence and embankment. For instance, the Albanian Law on Irrigation and Drainage System mandates the implementation of flood defence projects and stipulates budget sourcing for such projects. The Indian Embankment and Drainage Act of 1952 also regulates the construction, maintenance, and removal of embankments in this country and establishes guidelines for engineering works.

(5). Mandating or prohibiting funding, budget, fees or charges for FRM: 30% (nr=43) of laws provide regulations for the financial sources of FRM activities. The US National Flood Insurance Act (1968) and the French law on Compensation of the Victims of Natural Disasters (1982) are two examples that create, respectively, government-provided and public-private partnership flood insurance programmes. Also, the People’s Survival Fund Act (2012) in the Philippines and the act on Creation of the Fund for Civil Protection, Prevention, and Mitigation of Disasters (2005) in El Salvador focus on creating flood recovery funds from national governments for the local communities.

3.1.3. Who does the law target?

Overall, national-level public actors are given the dominant roles and responsibilities in all the laws analyzed. Yet, the level of involvement of non-governmental actors (i.e. civil society, the private sector and public-private partnerships) and local and regional governments varies in different countries’ laws. Among the 30 countries, 16 define some kind of FRM ownership for local government, in addition to the regional/sub-national and national level government (e.g. UK, New Zealand, Pakistan and Philippines) and 7 countries engage communities (people, civil society and homeowners) in FRM activities. The latter is either through the creation of community-level governance structures (e.g. farmers’ or water users’ association) that can contribute to flood-related decision making or by mandating involvement of civil society representatives in the process of FRM planning (e.g. National Disaster Management Act of Pakistan and Law on the Integrated Management of Water Resources in Albania), or through obliging implementation of property-level mitigation measures (e.g. Act on Managing Water Resources in Germany). In addition, 10 countries acknowledge the role of the private sector, and 9 countries recognize the role of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in their national-level laws, especially in light of strengthening cooperation and communication among the national/local governments and NGOs/private sectors for flood response and preparedness (e.g. Law on the national risk management system in Honduras, Disaster Reduction and Management Act in the Philippines, and Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act in the US). However, the laws of 11 countries (e.g. the Netherlands, Mexico and India) solely rely on defining the roles and responsibilities of the national government and public sectors for FRM activities.

The role of multi-actor engagement is increasingly considered as a crucial element of flood risk governance (Alexander et al., Citation2016a; Doorn-Hoekveld, Citation2017; Wiering et al., Citation2018). For instance, in the Netherlands, flood protection is a specific governmental competence by law, and therefore, government and public sectors have a dominant role in FRM responsibilities, which is reported as a driver of the limited contribution of other actors – particularly citizens (Doorn-Hoekveld, Citation2017; Wiering et al., Citation2017). However, in the UK, there are signs of a shift in flood risk governance arrangements for England and Wales, which has been influenced by the Flood and Water Management Act of 2010. This act gives the local authorities a leadership role and the Environment Agency a national overview role concerning FRM (Alexander et al., Citation2016b; Environment Agency, Citation2011; Goytia et al., Citation2016), while a variety of sub-arrangements with specific roles for public-private and national-regional-local partners also exist (Wiering et al., Citation2017).

3.2. Temporal aspects of flood risk management in national laws

Flood events and risks are increasing over time due to the impacts of climate change (IPCC, Citation2018). This calls for (1) integrating climate change in future flood projections, and (2) focusing on reducing current and future flood risks through proactive FRM – instead of reactive approaches that only focus on response and recovery after flood events. This section will look at how national laws address such temporal challenges of FRM.

3.2.1. Climate change and changing flood risks

Overall, there are a few examples of laws that mandate the inclusion of climate change in the projection, assessment and management of future flood risks, yet most of the laws do not recognize the impacts of climate change in regulating decisions and actions for future flood risks. As seen in the previous section, out of the 139 laws analyzed, only 13 laws from 10 countries contain a specific climate change focus, out of which 7 laws have both an adaptation and mitigation focus and 6 laws (from Bangladesh, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Pakistan and Philippines) merely look at adaptation. In total, 30 laws – 21% of the total laws – incorporate ‘climate change’ in the document, most of which have been passed since 2002. Some of these laws emphasize the inclusion of climate change parameters in the flood and hazard related policies and regulations to take account of dynamic future risks and resilience. For example, the Law Concerning Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics (2009) obliged the Indonesian government to formulate climate change adaptation policies, strategies and programmes, and monitor their implementation, including through the monitoring of climate change indicators and climatology data collection. The UK Flood and Water Management Act of 2010Footnote9 also mandates the specification of the current and predicted impact of climate change on flood risk in the national flood and coastal risk management strategy of the UK. Furthermore, our analysis shows that only 17% of the DRM laws analyzed incorporate climate change in the document, demonstrating a significant lack of attention to climate-dependent changing risk in the mitigation and management of future disasters.

3.2.2. Proactive vs reactive laws

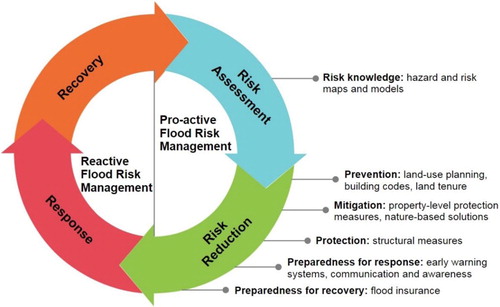

National level laws can accelerate proactive FRM by regulating the measures that assess and reduce possible future flood risks. Flood risk reduction has been officially defined by the UN Office for DRR (UNDRR) as a systematic approach to identify, assess and reduce the risks of disasters (). A set of themes introduced in the Hyogo and Sendai frameworksFootnote10 as well as IFRC reports that define how to analyze the incorporation of risk reduction activities and strategies in legislative documents. Such themes include the provision of early warning system (EWS), provision of community education and public awareness, improving building codes and land use planning, provision of risk-sharing and insurance, and improving public participation in DRR activities (IFRC and UNDP, Citation2014).

Figure 5. Proactive and reactive FRM. Adopted from (Surminski & Thieken, Citation2017) and (IFRC and UNDP, Citation2014).

35 out of the 139 laws (from 26 countries) have a DRM focus covering various aspects of DRM (). Most of these laws were adopted in the 1990s and early 2000s and have not been substantially updated in the last decade. These DRM laws mostly have a holistic view on different aspects of DRM but do not include DRR elements as a priority. Only 8 out of 35 DRM laws incorporate ‘DRR’, all of which have been passed since early 2002, with some prioritizing DRR over other aspects of DRM (e.g. DRM laws in New Zealand, Indonesia, Nepal and Philippines). However, some national laws may not use the terminology of ‘DRR’ but still have a strong focus on activities related to DRR such as EWS, risk mapping and funding risk reduction activities. In section 4.3 we analyze different aspects of DRR in national laws of five countries as a part of our resilience framework.

also shows the timing of creation of the 139 laws. The spike in the number of laws – starting from the beginning of the twenty-first century – suggests a link to the increasing frequency and real impacts of flood events followed by pressures from governments and international organizations for improving flood risk governance. Many of the flood-focused or DRM laws were passed in the wake of significant disasters. In the UK, for example, the series of floods in summer 2007 triggered the creation of the UK Flood and Water Management Act in 2010. This Act was recommended by the Pitt Review, an independent review assigned by the British government to study the drivers and impacts of the 2007 flood events (The Pitt Review Report, Citation2008). In the US, the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 was promoted as a result of the destruction caused by flood surges from Hurricane Betsy in Florida and Louisiana in 1965. In France, following the serious flooding of 1981, the French parliament passed a law the following year to institute a new compensation system for natural hazards (Magnan, Citation1995). In Germany, the hundred-year flood of summer 2002 provided the background for the German federal parliament passing the Flood Control Act in 2005 to introduce nationally binding requirements for the prevention of flood damage (Kienzler et al., Citation2015; Thieken et al., Citation2016). In Indonesia, the tsunami of September 2004 that caused tremendous loss of life and destroyed large numbers of properties and infrastructure in the province of Aceh led to the development of the comprehensive Law Concerning DRM in 2007 (IFRC and PMI, Citation2014). These and many similar examples indicate that law-making for flood and disaster risk has often been a post-event response by governments rather than a proactive intervention for flood risk reduction (see Supplementary Information C for a comparison between the history of flood events and flood-related laws created in the 33 countries). This also differentiates between DRM and adaptation laws, the latter providing forward-looking consideration of future flood risks.

3.3. Role of national laws in community flood resilience

This section explores the framing and focus of national laws in the context of flood resilience. 16 out of 139 laws incorporate the word ‘resilience’ and three laws, from Mexico, Peru and the Philippines, provide a clear definition of ‘resilience’ in the laws, all of which follow the UNDRR’s definition of resilience:

the ability of a system, community or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate to and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner, including through the preservation and restoration of its essential basic structures and functions. (UNDRR, Citation2016)

However, national laws can enhance community resilience in many ways and through various functions and instruments. In this section, we present the result of our deep analysis on the laws of five case study countries i.e. Bangladesh, Indonesia, Nepal, UK, and the US, using the indicators from the community flood resilience framework presented in (Keating et al., Citation2017). Given that FRM needs to be holistic and focus on improving various aspects of flood resilience, that is, the five forms of capital introduced above – financial, physical, human, social and natural – we investigate if and how these five forms of capital have been addressed in the laws of the five case studies. Importantly this analysis looks at the laws but not the specific socio-economic or cultural contexts of the five countries.

3.3.1. Financial capital

National legislation can support financial capital by regulating or encouraging the creation and distribution of any economic resources that support household asset recovery, business continuity, community disaster response and risk reduction investments – e.g. through providing insurance, loans, grants, funds and compensation. Among the five countries analyzed, US and UK laws mainly influence financial capital via improving insurance mechanisms, whereas the other countries either do not incorporate financial mechanisms or rely on the government-created disaster response fund ().

Table 2. The five forms of capital indicators in the national laws of the five case studies. See Supplementary Information D for the name of laws incorporating each capital/indicator and for more description of indicators.

The national laws of the US and UK support household asset recovery and business continuity by creating or improving affordable national insurance. The UK Water Act of 2014 establishes a public-private flood reinsurance scheme (i.e. FloodRe) to promote availability and affordability of flood insurance for households while minimizing the cost of doing so for the insurance companies. The US National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 creates a government-provided flood insurance programme and establishes criteria for premium reductions given to flood protection and risk reduction projects. Later amendments of this act made the purchase of flood insurance mandatory for properties within floodplains, allowed the rise of premiums in high-flood areas to reflect the real risk of living in such areas, and ceased subsidizing flood insurance for properties that had been flooded multiple times.

The contribution of national laws to the provision of community disaster funds depends on the political and governance situation of countries. For example, the national law of the US authorizes the president to make loans to local governments which may suffer a substantial loss of revenues as a result of the flood. As such, the communities have access to some flood emergency and recovery funds, yet activation of these funds requires decisions made at the federal or state level. The Indonesian Law Concerning DRM, to the contrary, mandates national and regional governments to create a community disaster response fund – known as disaster aid – that is available for individual members of the community in the form of compensation money for personal injury, soft loan for business recovery, or aid for necessities. The ZFRA surveys in Indonesia shows that, in 36 out of 40 communities analyzed, a local flood emergency and recovery fund exists for the community members. However, 61% of community members either were not aware of the existing funds or claimed that they did not have access to such funding during the previous floods. This presumably indicates that legislating for the creation of flood emergency funds without a mechanism for fair distribution and communication of such funds does not support the financial recovery of the communities.

We did not identify any law at the national level in the five countries that mandates budgets for DRR investments other than building large-scale physical protections – e.g. investing in flood resilience and adaptation measures. Yet, some countries bundled risk reduction into their national DRM funding. For example, the Stafford Act of the US obligates the creation of federal funding programmes for disaster resilience and mitigation for local government, which come from the general budget of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

3.3.2. Human capital

National laws may contribute to increasing a community's knowledge on flood response and preparation by creating relevant governance structures, responsibilities and funding. The US act on Water Infrastructure Improvement, for instance, mandates all the non-federal sponsors of dam rehabilitation projects to demonstrate a Floodplain Management Plan, in which increasing public education and awareness of flood risk in areas protected by the dam project should be included. The Stafford Act also obligates FEMA to provide funds for education and training in life-supporting first aid to children. In Indonesia, the Law Concerning DRM provides the right to all flood-prone community members to receive education, training, and skills in DRM and obtain information on DRM policies.

Raising awareness about current flood risk exposure has been mainly encouraged in countries’ laws via creating or improving flood zone maps and models. All five countries analyzed have at least one law that mandates the creation of flood zone maps or identification of high flood risk zones. However, such maps are often aimed at providing information for governments and DRM bodies rather than raising flood awareness among the communities. The Bangladesh Water Act (2013) gives power to the executive committee of the water resources council to declare any wetland as a flood control zone based on the results of inquiries and surveys conducted in this country. The Indonesia Law Concerning DRM also assigns the task of preparing, deciding on, and disseminating maps of disaster-prone areas to local agencies. After disseminating the maps to the government bodies, it becomes the responsibility of the Indonesian government to revoke or reduce property rights in such areas and provide compensation for the property holders. The ZFRA interviews and surveys indicate that most of the communities in Nepal, Bangladesh, Indonesia and the US have a roughly accurate perception of their flood exposure, but according to local knowledge, such awareness has been triggered by previous flood events and not by the flood zone maps and models.

To raise awareness about future flood risk, some laws encourage research on the impact of climate change on natural hazards and dissemination of climate change information for the public. The Bangladesh DRM Act legislates for the establishment of a National Disaster Management Research and Training Institute to research the effects of climate change and future risk and assess the capability of disaster management methods in light of future flood risk predictions. The Indonesia Law Concerning Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics obliges the Indonesian government to enhance awareness and public participation in climate change adaptation activities by fostering data collection, analysis and monitoring of climate change and dissemination of information within the public.

3.3.3. Natural capital

Protection, conservation and preservation of existing natural resources such as water resources, farmlands, green lands, floodplains, wetlands and other ecosystems are often addressed in laws related to water resource management and environmental management. Among the laws of the five countries, the Clean Water Act, National Environmental Policy Act and North American Wetlands Conservation Act in the US; the Soil and Watershed Conservation Act in Nepal; the Law Concerning DRM in Indonesia; and the River Research Institute Act in Bangladesh; all emphasize establishing policies, studies, plans, and creating responsibilities for protecting existing natural resources. However, no law encourages or regulates the application of new natural protection measures or nature-based adaptive solutions for flood risk reduction and protection (), despite the increasing importance of such measures in recent FRM discussions (Hartmann et al., Citation2019; Jongman, Citation2018; Schanze, Citation2017).

3.3.4. Physical capital

Implementation of large-scale flood protection projects, also known as structural measures, are mainly regulated or encouraged in the water resource management laws of the five countries by creating policies, responsibilities, and funding for these projects, e.g. Embankment and Drainage Act, Water Development Board Act and Water Act in Bangladesh; Soil and Watershed Conservation Act in Nepal; and Watershed Protection and Flood Prevention Act of the US. We did not find any laws that support or regulate property level flood protection measures, but these are probably considered in local plans and regulations of these five countries.

Improvement of post-event services is considered in the DRM laws that identify departments and responsibilities for DRR. The DRM Acts of Indonesia and Bangladesh identify fulfilment of necessities (i.e. water, food, healthcare, accommodation and clothing) as one of the main components of emergency response and share related responsibilities among the national, regional and local disaster management bodies.

Creation and use of EWS are proposed and encouraged by national laws of many countries as a method to increase public awareness and preparation for future floods. Some laws only emphasize the creation of EWS as the main requirement of DRM e.g. the UK Flood and Water Management Act, while others specify details and directives for the implementation of EWS. The Bangladesh Weather Act (2018) creates the Bangladesh Meteorological Department and regulates the establishment of a weather forecasting centre that issues weather alerts and warnings. The Law Concerning DRM in Indonesia identifies EWS as a set of actions from observation and analysis of disaster signs to decision-making by authorities, dissemination of information and community actions, and regulates related roles and responsibilities.

3.3.5. Social capital

National flood laws may contribute to improving community social networks by requiring the creation of local flood response and recovery plans that coordinate individual activities or suggest safety improvements in the flood-prone communities. National flood laws can also regulate or encourage public participation in FRM activities e.g. in the process of preparing policies, plans, and strategies for FRM, or designing and implementing flood risk reduction interventions.

The Bangladesh Disaster Management Act obligates the creation of a local DRM plan based on each area's specifications and local hazards. The UK Flood and Water Management Act (2010) mandates the creation, maintenance and application of a strategy for local FRM by lead local flood authorities who must consult the public and local risk management authorities about these strategies.

Indonesia’s Law Concerning DRM establishes the right for all members of communities to participate in decision-making on DRM activities. This law encourages participatory planning, particularly for DRR and reconstruction activities. Also, it obligates local governments to increase community participation in the provision of funds and aid. However, the ZFRA interviews and surveys in Bangladesh and Indonesia show that, in a majority of communities analyzed (32 out of 40 in Indonesia and 6 out of 9 in Bangladesh), there is no local flood plan available. Additionally, in 5 communities in Indonesia and 3 communities in Bangladesh, the flood plans have not been developed in a participatory way and have not been communicated within the communities.

In term of inclusiveness, Indonesia’s Law Concerning DRM establishes the equal right for all community members to receive aid for basic needs and compensation for losses from disasters besides benefiting from social security in flood-prone areas. Bangladesh’s DRM Act obliges the government to give preference to the protection and risk reduction for vulnerable communities affected by flood events, including minorities, older persons, women, children and disabled persons. The Stafford Act of the US also requires EWS to provide information to individuals with disabilities, special needs and limited English proficiency.

4. Discussion and conclusion

Flood risk governance is structured and has evolved differently across countries and regions, driven by specific cultural and historical aspects, as well as the scale and real impact of flood risk experienced. This study provides insights to help improve understanding of the role that national laws can play in enhancing flood resilience and adaptation.

Our analysis of 139 laws in 33 countries shows that, historically, there has been a shift in flood laws away from an initial focus on flooding as a natural and water resource management issue towards a broader set of laws that consider flooding within DRM and climate adaptation policy. Indeed, climate change adaptation appears as a new paradigm for legislation aimed at managing flood risks, usually mentioned up-front in the justification of flood laws. However, we find a significant lack of detailed climate change recognition within flood-related laws. This is underpinned by our observation of a disconnect between DRM and climate change laws: both are often separated and largely working in isolation in most of the countries. This underlines the importance of enhanced integration of FRM and climate adaptation (IFRC, Citation2019). Continued separation of ‘adaptation’ and ‘FRM’ laws can lead to gaps in institutional ownership and responsibility, and to separate budgets. This could also mean that investments in flood prevention might be based on current risk levels and underestimate future risk trends, reducing their effectiveness.

Moreover, our analysis indicates that the creation of new DRM legislation has often been a post-event response to major flood events. The content analysis of DRM laws across countries demonstrates that flood risk reduction and prevention (known as proactive FRM strategies) are not prioritized in such laws and a larger focus remains on response and recovery (known as reactive FRM strategies). However, the predicted impacts of climate change (i.e. rise in temperature and sea level, and changes in precipitation) call for ex-ante, pre-event and proactive policymaking and governance, which also needs to be considered in the legislation of countries. A shift to anticipatory action is difficult for many reasons (Surminski et al., Citation2016), and laws could play an important role in facilitating this adjustment, for example, by requiring any flood risk assessments to consider current and future risks and resilience levels, or by setting out how climate change trends need to be taken into account when taking decisions on infrastructure or land-use. This is particularly important in the context of so-called slow-onset changes, such as sea-level rise and coastal erosion, which require difficult decisions about pre-emptive resettlement or managed retreat that are likely to be politically difficult and unpopular.

The deep-dive analysis of the role of national laws in supporting community flood resilience shows that there is very little recognition of natural capital as a key component of increasing flood resilience. The national laws investigated are predominantly focused on physical and human capital, such as EWS, flood zone maps and models, and building large scale flood protection measures. However, the analysis did not identify any national law that explicitly promotes the creation of new natural protection measures (i.e. nature-based solutions) as an FRM and climate adaptation strategy. This is an area that will require further attention as natural FRM efforts offer many advantages over ‘hard’ engineered measures such as seawalls, including environmental benefits. However, natural capital often remains unrecognized or underfunded. This underlines the importance of treating FRM and adaptation as a broad and holistic concept: ensuring the necessary human, social, physical, natural and financial systems are in place to address climate impacts when they occur. Climate change cuts across all of these systems, which in turn are complex and interrelated, and trying to tackle adaptation or FRM focusing on only one system is likely to fail (Surminski & Szoenyi, Citation2019).

As an extension of this study, further research is required on the question of whether or how the laws are being implemented within countries. Case studies from the ZFRA (as described in section 3.3) highlight that, despite the existence of comprehensive laws for FRM, those laws have rarely been implemented properly and equally across the five countries. Therefore, further investigation into the implementation, and thereafter the impact and effectiveness, of these laws would be important. Another line of future research would be to take the database of this study and focus on the socio-economic, political and cultural factors influencing law-making for disaster and climate change across different countries.

Moreover, it must be noted that new concepts such as resilience, climate change adaptation, DRR and nature-based solutions usually get adopted more quickly in strategies and policies, which are produced and updated more frequently than the national laws. Therefore, in some ways, it is not surprising to see that such notions are still less recognized in laws compared to the traditional FRM measures and concepts such as physical protection measure, emergency response and recovery. Nevertheless, we see this as a big gap in the way laws are influencing FRM, and therefore suggest further efforts be made to revisit and update laws to enable them to effectively support future FRM.

Finally, it should be emphasized that the parallel national and international processes, such as preparing the nationally determined contributions, national adaptation plans, and DRR strategies, can provide a vehicle for governments to understand and address the gaps in their national laws in order to encourage a shift from incremental actions towards a more resilience-oriented approach in FRM.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (187.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the ‘Climate Change Laws of the World’ group at the Grantham Research Institute for their support in collecting and analyzing the data, and are grateful for peer review comments from Alina Averchenkova, Tommaso Natoli, Ann Vaughan, and the editor and two anonymous reviewers of this journal.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance defines community flood resilience as ‘the ability of a system, community or society to pursue its social, ecological and economic development goals while managing its disaster risk over time in a mutually reinforcing way’(Keating et al., Citation2017).

2 Notably in Sendai Framework by United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR), Rockefeller’s 100 Resilient Cities, and the Coalition for Climate Resilient Investments.

3 Legislation or law is a system of rules passed by and enacted by a legislature or other governor body.

4 A research group at the Grantham Research Institute at the London School of Economics (UK) that collects and maintains a database covering all laws and policies that are relevant to climate change and have been passed by legislative branches or published by executive branches, and that are no longer in draft form (https://climate-laws.org/)..

5 Collects and analyzes an online database on the laws related to DRM across the world https://www.ifrc.org/en/publications-and-reports/idrl-database/

6 Via our local partners in the ZFRA project.

7 ZFRA defines community as a group of people who have a kind of physical, administrative, or social bonds that make them form a unit. As the definition of community varies across different cities and villages, in ZFRA projects, the boundaries of communities are largely defined by the community members themselves. See (Pettengel et al., Citation2019) for more information.

8 Primary and secondary laws are created respectively by the legislative and executive branches of government. Primary law—also known as ‘act’—generally consists of statutes that set out broad outlines and principles. Secondary law—also known as 'regulation, delegated legislation or subordinate legislation'—is mainly issued as the result of the primary act and creates legally enforceable regulations and the procedures for implementing them.

9 This act extends only to England and Wales, as Northern Ireland and Scotland have their own legislation.

10 Developed by UNISDR focusing on a set of natural DRR targets and priorities for the countries.

References

- Adger, W. N., Brown, I., & Surminski, S. (2018). Advances in risk assessment for climate change adaptation policy. The Royal Society Publishing.

- Aerts, J. C., Botzen, W. J., Clarke, K. C., Cutter, S. L., Hall, J. W., Merz, B., Michel-Kerjan, E., Mysiak, J., Surminski, S., & Kunreuther, H. (2018). Integrating human behaviour dynamics into flood disaster risk assessment. Nature Climate Change, 8(3), 193–199. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0085-1

- Alexander, M., Priest, S., & Mees, H. (2016a). A framework for evaluating flood risk governance. Environmental Science & Policy, 64, 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.06.004

- Alexander, M., Priest, S. J., Micou, P., Tapsell, S. M., Green, C. H., Parker, D. J., & Homewood, S. (2016b). Analysing and evaluating flood risk governance in England–enhancing societal resilience through comprehensive and aligned flood risk governance arrangements. Middlesex University.

- Arnold, J. L. (1988). The evolution of the 1936 flood control act. Office of History, US Army Corps of Engineers.

- Averchenkova, A., Fankhauser, S., & Nachmany, M. (2017). Trends in climate change legislation. Edward Elgar.

- Bahadur, A. V., Ibrahim, M., & Tanner, T. (2010). The resilience renaissance? Unpacking of resilience for tackling climate change and disasters.

- Béné, C., Wood, R. G., Newsham, A., & Davies, M. (2012). Resilience: New utopia or new tyranny? Reflection about the potentials and limits of the concept of resilience in relation to vulnerability reduction programmes. IDS Working Papers, 2012, 1–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2040-0209.2012.00405.x

- Campbell, K. A., Laurien, F., Czajkowski, J., Keating, A., Hochrainer-Stigler, S., & Montgomery, M. (2019). First insights from the flood resilience measurement tool: A large-scale community flood resilience analysis. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 101257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101257

- Castanheira, M., Rihoux, B., & Bandelow, C. B. (2017). Sustainable governance indicators 2017: Belgium report, Universite Libre de Bruxelles Institutional Repository 2013/262877.

- Clarvis, M. H., Allan, A., & Hannah, D. M. (2014). Water, resilience and the law: From general concepts and governance design principles to actionable mechanisms. Environmental Science & Policy, 43, 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2013.10.005

- Craig, R. K. (2010). Stationarity is dead-long live transformation: Five principles for climate change adaptation law. Harv. Envtl. L. Rev, 34, 9. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1357766

- Crase, L., Connor, J., Michaels, S., & Cooper, B. (2020). Australian water policy reform: Lessons learned and potential transferability. Climate Policy, 20(5), 641–651. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1752614

- CRED, & UNDRR. (2015). The human cost of natural disasters: A global perspective.

- De MoeL, H., Aerts, J. C., & Koomen, E. (2011). Development of flood exposure in the Netherlands during the 20th and 21st century. Global Environmental Change, 21(2), 620–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.12.005

- DFID. (1999). Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets.

- Dieperink, C., Hegger, D. T., Bakker, M., Kundzewicz, Z. W., Green, C., & Driessen, P. (2016). Recurrent governance challenges in the implementation and alignment of flood risk management strategies: A review. Water Resources Management, 30(13), 4467–4481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-016-1491-7

- Doorn-Hoekveld, W. V. (2017). Transboundary flood risk management: Compatibilities of the legal systems of flood risk management in the Netherlands, Flanders and France±A comparison. European Energy and Environmental Law Review, 26, 81–96.

- Ebbesson, J., & Hey, E. (2013). Introduction: Where in law is social-ecological resilience? Ecology and Society, 18(3). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05750-180325

- England, P. (2019). Trends in the evolution of floodplain management in Australia: Risk assessment, precautionary and robust decision-making. Journal of Environmental Law, 31(2), 315–341. https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/eqz012

- Environment Agency, & defra. (2011). Understanding the risks, empowering communities, building resilience: The national flood and coastal erosion risk management strategy for England.

- Garmestani, A. S., & Allen, C. R. (2014). Social-ecological resilience and law. Columbia University Press.

- Garmestani, A. S., Allen, C. R., & Benson, M. H. (2013). Can law foster social-ecological resilience? Ecology and Society, 18(2), 37. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05927-180237

- Gilissen, H. K. (2015). The integration of the adaptation approach into EU and Dutch legislation on flood risk management. Journal of Water Law, 24, 157–165.

- Goytia, S., Pettersson, M., Schellenberger, T., Van Doorn-Hoekveld, W. J., & Priest, S. (2016). Dealing with change and uncertainty within the regulatory frameworks for flood defense infrastructure in selected European countries. Ecology and Society, 21(4). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08908-210423

- Hanger, S., Linnerooth-Bayer, J., Surminski, S., Nenciu-Posner, C., Lorant, A., Ionescu, R., & Patt, A. (2018). Insurance, public assistance, and household flood risk reduction: A comparative study of Austria, England, and Romania. Risk Analysis, 38(4), 680–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12881

- Hartmann, T., & Albrecht, J. (2014). From flood protection to flood risk management: Condition-based and performance-based regulations in German water law. Journal of Environmental Law, 26(2), 243–268. https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/equ015

- Hartmann, T., Slavíková, L., & Mccarthy, S. (2019). Nature-based solutions in flood risk management. Nature-based flood risk management on private land. Springer.

- Heidrich, O., Reckien, D., Olazabal, M., Foley, A., Salvia, M., de Gregorio Hurtado, S., Orru, H., Flacke, J., Geneletti, D., Pietrapertosa, F., Hamann, J. J.-P., Tiwary, A., Feliu, E., & Dawson, R. J. (2016). National climate policies across Europe and their impacts on cities strategies. Journal of Environmental Management, 168, 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.11.043

- Hobbs Jr, G. J. (1997). Colorado water law: An historical overview. U. Denv. Water L. Rev, 1, 1.

- Howarth, W. (2002). Flood defence law. Shaw & Sons.

- Howarth, W. (2017). Integrated water resources management and reform of flood risk management in England. Journal of Environmental Law, 29(2), 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/eqx015

- Howarth, W., & McGillivray, D. (2002). Water pollution and water quality law. European Environmental Law Review, 11.

- IFRC. (2019). Literature review on aligning climate change adaptation (CCA) and disaster risk reduction (DRR). Switzerland.

- IFRC AND PMI. (2014). International Disaster Response Law (IDRL) in Indonesia: An analysis of the impact and implementation of Indonesia’s legal framework for international disaster assistance. Palang Merah Indonesia and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

- IFRC AND UNDP. (2014). Effective law and regulation for disaster risk reduction: A multi-country report. IFRC & UNDP.

- IPCC. (2018). Global warming of 1, 5° C. Special report. IPCC.

- Jongman, B. (2018). Effective adaptation to rising flood risk. Nature Communications, 9(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04396-1

- Keating, A., Campbell, K., Mechler, R., Michel-Kerjan, E., Mochizuki, J., Kunreuther, H., Bayer, J., Hanger, S., McCallum, I., See, L., Williges, K., Atreya, A., Botzen, W., Collier, B., Czajkowski, J., Hochrainer, S., & Egan, C. (2014). Operationalizing resilience against natural disaster risk: Opportunities, barriers, and a way forward. Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/11191/1/zurichfloodresiliencealliance_ResilienceWhitePaper_2014.pdf

- Keating, A., Campbell, K., Szoenyi, M., Mcquistan, C., Nash, D., & Burer, M. (2017). Development and testing of a community flood resilience measurement tool. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 17(1), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-17-77-2017

- Kienzler, S., Pech, I., Kreibich, H., Müller, M., & Thieken, A. H. (2015). After the extreme flood in 2002: Changes in preparedness, response and recovery of flood-affected residents in Germany between 2005 and 2011. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 15(3), 505–526. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-15-505-2015

- Kulp, S. A., & Strauss, B. H. (2019). New elevation data triple estimates of global vulnerability to sea-level rise and coastal flooding. Nature Communications, 10(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07882-8

- Lemos, M. C., & Agrawal, A. (2006). Environmental governance. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 31(1), 297–325. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.energy.31.042605.135621

- Magnan, S. (1995). Catastrophe insurance system in France. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance - Issues and Practice, 20(4), 474–480. https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.1995.42

- Magnuszewski, P., Jarzabe, L., Keating, A., Mechler, R., French, A., Laurien, F., Arestegui, M., Etienne, E., Ilieva, L., & Ferradas, P. (2019). The flood resilience systems framework: From concept to application. Journal of Integrated Disaster Risk Management, 9(1), 56–82. https://doi.org/10.5595/idrim.2019.0348

- Mechler, R., & Hochrainer-Stigler, S. (2019). Generating multiple resilience dividends from managing unnatural disasters in Asia: Opportunities for measurement and policy. Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series No. 601. http://doi.org/10.22617/WPS190573-2.

- Mees, H., Crabbe, A., & Suykens, C. (2018). Belgian flood risk governance: Explaining the dynamics within a fragmented governance arrangement. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 11(3), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12330

- Mees, H., Suykens, C., Beyers, J.-C., Crabbé, A., Delvaux, B., & Deketelaere, K. (2016). Analysing and evaluating flood risk governance in Belgium: dealing with flood risks in an urbanised and institutionally complex country. STAR-FLOOD Consortium.

- Mercer, J. (2010). Disaster risk reduction or climate change adaptation: Are we reinventing the wheel? Journal of International Development: The Journal of the Development Studies Association, 22, 247–264. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1677

- Nachmany, M., Byrnes, R., & Surminski, S. (2019). Policy brief National laws and policies on climate change adaptation: A global review. Grantham Research Institute on Climate change and the Environment, London School of Economics. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/National-laws-and-policies-on-climate-change-adaptation_A-globalreview.pdf.

- Nachmany, M., Fankhauser, S., Setzer, J., & Averchenkova, A. (2017). Global trends in climate change legislation and litigation: 2017 update. Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics. http://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/publication/global-trends-in-climate-change-legislation-and-litigation-2017-update/.

- Nicholls, R. J., Hanson, S., Herweijer, C., Patmore, N., Hallegatte, S., Corfee-Morlot, J., Château, J., & Muir-Wood, R. (2008). Ranking port cities with high exposure and vulnerability to climate extremes: Exposure estimates. OECD Environment Working Papers. No. 1. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/011766488208.

- Olazabal, M., Ruiz De Gopegui, M., Tompkins, E., Venner, K., & Smith, R. (2019). A cross-scale worldwide analysis of coastal adaptation planning. Environmental Research Letters, 14(12), 124056. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab5532

- Osumgborogwu, I., & Chibo, C. (2017). Environmental laws in Nigeria and occurrence of some geohazards: A review. Asian Journal of Environment and Ecology, 2(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.9734/AJEE/2017/34045

- Peel, J., & Fisher, D. (2016). The role of international environmental law in disaster risk reduction. BRILL.

- Pettengel, C., Mcquistan, C., Szönyi, M., Keating, A., Laurien, F., Ianni, F., Etienne, E., Macclune, K., & Bold, R. (2019). Flood Resilience Measurement for Communities: Project set up, study set up, data collection, and grading. In Flood resilience measurement for communities (FRMC) (pp. 1–48). Flood Resilience Alliance.

- The Pitt Review Report. (2008). Learning lessons from the 2007 floods. Cabinet Office.

- Reckien, D., Salvia, M., Heidrich, O., Church, J. M., Pietrapertosa, F., De Gregorio-Hurtado, S., D’Alonzo, V., Foley, A., Simoes, S. G., Krkoška Lorencová, E., Orru, H., Orru, K., Wejs, A., Flacke, J., Olazabal, M., Geneletti, D., Feliu, E., Vasilie, S., Nador, C., … Dawson, R. (2018). How are cities planning to respond to climate change? Assessment of local climate plans from 885 cities in the EU-28. Journal of Cleaner Production, 191, 207–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.220

- Schanze, J. (2017). Nature-based solutions in flood risk management: Buzzword or innovation? Journal of Flood Risk Management, 10(3), 281–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12318

- Schipper, E. L. F., & Langston, L. (2015). A comparative overview of resilience measurement frameworks: Analysing indicators and approaches. Overseas Development Institute—Working Paper, 422, 205.

- Spray, C., Ball, T., & Rouillard, J. (2009). Bridging the water law, policy, science interface: Flood risk management in Scotland. Journal of Water Law, 20, 165–174.

- Stallworthy, M. (2006). Sustainability, coastal erosion and climate change: An environmental justice analysis. Journal of Environmental Law, 18(3), 357–373. https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/eql017

- Surminski, S., & Szoenyi, M. (2019). Nature-based flood resilience: reaping the triple dividend from adaptation. In E. Berglof & T. Thiele (Eds.), From green to blue finance, integrating the ocean into the global climate finance architecture (pp. 22–23). LSE Institute of Global Affairs.https://www.lse.ac.uk/iga/assets/documents/global-policy-lab/From-Green-to-Blue-Finance.pdf

- Surminski, S., & Tanner, T. (2016). Realising the ‘triple dividend of resilience’. Springer.

- Surminski, S., & Thieken, A. H. (2017). Promoting flood risk reduction: The role of insurance in Germany and England. Earth's Future, 5(10), 979–1001. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017EF000587

- Thieken, A. H., Kienzler, S., Kreibich, H., Kuhlicke, C., Kunz, M., Mühr, B., Müller, M., Otto, A., Petrow, T., Pisi, S., & Schröter, K. (2016). Review of the flood risk management system in Germany after the major flood in 2013. Ecology and Society, 21(2), 51. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08547-210251

- Thomalla, F., Downing, T., Spanger-Siegfried, E., Han, G., & Rockström, J. (2006). Reducing hazard vulnerability: Towards a common approach between disaster risk reduction and climate adaptation. Disasters, 30(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2006.00305.x

- Thornton, J., Barnes, K., Boukraa, A., David, S., & Helme, N. (2018). Significant UK environmental law cases 2017/18. Journal of Environmental Law, 31(2), 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/eqz014

- Tierney, K. (2012). Disaster governance: Social, political, and economic dimensions. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 37(1), 341–363. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-020911-095618

- Tingsanchali, T. (2012). Urban flood disaster management. Procedia Engineering, 32, 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2012.01.1233

- UNDRR. (2016). Terminology related to disaster risk reduction: updated technical non-paper.

- Van Rijswick, M., Van Rijswick, H., & Havekes, H. J. (2012). European and Dutch water law. UWA Publishing.

- Wiering, M., Kaufmann, M., Mees, H., Schellenberger, T., Ganzevoort, W., Hegger, D., Larrue, C., & Matczak, P. (2017). Varieties of flood risk governance in Europe: How do countries respond to driving forces and what explains institutional change? Global Environmental Change, 44, 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.02.006

- Wiering, M., Liefferink, D., & Crabbé, A. (2018). Stability and change in flood risk governance: On path dependencies and change agents. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 11(3), 230–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12295