ABSTRACT

On the one hand, a large number of companies have committed to achieve net zero emissions and many of them foresee to offset some remaining emissions with carbon credits, suggesting a surge of future demand. Yet, the supply side of the voluntary carbon market is struggling to align its business model with the new legal architecture of the Paris Agreement. This article juxtaposes these two perspectives. It provides an overview of the plans of 482 major companies with some form of neutrality/net zero pledge and traces the struggle on the supply side of the voluntary carbon market to come up with a viable business model that ensures environmental integrity and contributes to achieving the objectives of the Paris Agreement. Our analysis finds that if carbon credits are used to offset remaining emissions against neutrality objectives, these credits need to be accounted against the host countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to ensure environmental integrity. Yet, operationalizing this approach is challenging and will require innovative solutions and political support.

Key policy insights

There is a growing mismatch between the faith placed in carbon credits by private sector companies and the continued quest for a common position of the main suppliers of the voluntary carbon market.

The voluntary carbon market has not yet found a way to align itself with the new legal architecture of the Paris Agreement in a credible and legitimate way.

Public policy support at the national and international level will be needed to operationalize a robust approach for the market’s future activities.

1. Introduction

Since the adoption of the Paris Agreement under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in December 2015, the number of major companies that have put forward pledges to achieve net zero emissions has been growing significantly (Black et al., Citation2021). The vast majority of companies pledging for neutrality rely on some form of compensation for remaining emissions through offsetting. These pledges could have a strong impact on the voluntary carbon market, a market which in its most original form allows individuals or organizations to buy carbon credits issued by privately organized certification schemes to voluntarily offset their carbon footprint for a multitude of reasons, including but not limited to ethical considerations. If the pledges translate into actual demand for carbon credits, the voluntary carbon market could grow to another order of magnitude compared to current levels, at least in theory. In practice, however, the market is confronted with new challenges, particularly on the supply side. The Paris Agreement’s universal sway and transformative ambition requires private carbon credit providers to think in new ways (Hermwille & Kreibich, Citation2016; Kreibich & Obergassel, Citation2019a).

This article explores the voluntary carbon market understood as comprising all transfers of mitigation outcomes for non-compliance purposes. It brings together the perspectives of the demand and the supply sides of the voluntary carbon market by juxtaposing a survey of the potential demand for carbon credits from large greenhouse gas (GHG) emitting companies with the struggle on the supply side in dealing with the changed circumstances of the Paris Agreement. In doing so, the article discloses the entire spectrum of the voluntary market’s current situation.

The voluntary carbon market has been subject to academic and grey literature in the past. In particular, early literature studied the functioning of the voluntary carbon market and its potential benefits and challenges in the broader context of the emerging practice of carbon offsetting (Bellassen & Leguet, Citation2007; Bumpus & Liverman, Citation2008; Corbera et al., Citation2009; Gillenwater et al., Citation2007). By analysing narratives and discourses, several scholars explored the legitimacy of voluntary carbon offsetting (Bäckstrand & Lövbrand, Citation2006; Blum & Lövbrand, Citation2019; Lovell et al., Citation2009), including in the post-Paris era (Blum, Citation2020; Blum & Lövbrand, Citation2019), and even identified different ‘thought spaces’ of how the voluntary carbon market could be conceptualized in the future (Lang et al., Citation2019). Some scholars have also explored the voluntary carbon market’s potential to raise climate ambition (Kreibich & Obergassel, Citation2019a; Streck, Citation2021). While the more recent academic contributions touch upon the repercussions the Paris Agreement might have on the functioning of the voluntary carbon market, more detailed analyses of the accounting challenges have not yet found their way into the academic debate, albeit with notable exceptions (Fearnehough et al., Citation2020; Michaelowa et al., Citation2018).

Our analysis aims at filling this void by presenting the different approaches currently discussed and by tracing the discourse within the voluntary carbon market on how to deal with the Paris Agreement. By including the demand side, our analysis further contributes to a better understanding of the buyer’s future demand, a research gap that has been identified in previous work (Lang et al., Citation2019). The contribution of our analysis should also be seen in the context of a renewed interest in the voluntary carbon market, where there is an increased need of investors for advice. An indication of this need is the more recent publication of guidance documents that are to assist companies and organizations seeking to buy carbon offsets (Broekhoff et al., Citation2019; Schneider, Healy, et al., Citation2020).

The findings indicate that the voluntary carbon market as a whole has not yet found a way to align itself with the new legal architecture of the Paris Agreement in a credible and legitimate way; it seems to be caught in between credibility and feasibility. The growing mismatch between the faith placed in carbon credits by private sector companies to achieve their net zero or neutrality pledges and the continued quest for a common position of the main suppliers of the voluntary carbon market is cause for concern. There is a risk that the current discursive stalemate turns into a race to the bottom in which the voluntary carbon market undermines the objectives of the Paris Agreement instead of supporting the required transformational change.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 details the materials and methods used to conduct the analysis. Section 3 provides an overview of the status quo of the voluntary carbon market and the prospects of future demand by analysing existing corporate net zero pledges. Section 4 then lays the foundation for the subsequent analysis by reviewing key features of the Paris Agreement as they are relevant for the voluntary carbon market. On that basis, Section 5 traces the debate within the voluntary carbon community and its struggle for finding a model that is commensurate with the Paris Agreement. Section 6 concludes with a brief discussion of the results.

2. Material and methods

This article brings together the demand and the supply side of the voluntary carbon market by combining quantitative and qualitative methods. In order to capture the potential demand for carbon credits, existing analysis by Donofrio et al. (Citation2019), NewClimate Institute (Citation2020) and WEF (Citation2019) has been complemented with additional research by collating a list of 482 large companies with annual revenue of more than US$1 billion. The dataset was compiled building on existing databases by ECIU and Oxford Net Zero (ECIU, Citation2021), NewClimate Institute (Citation2020) and the UNFCCC’s NAZCA Platform (UNFCCC, Citation2020), as well as additional inquiry by the authors. The company pledges were categorized by sector, scope and type of emissions covered, time horizon and most importantly their intended use of offsets.

To scrutinize the voluntary carbon market’s quest for new solutions that are compatible with the architecture of the Paris Agreement, the debate among key stakeholders in the voluntary carbon market has been traced. Our study was carried out in four methodological steps:

Firstly, the main discursive arenas were identified. While the voluntary carbon market is characterized by a strong fragmentation that leads to a considerable lack of transparency, in particular on the demand side, there seems to be a consolidation of offset providers and intermediaries (Donofrio et al., Citation2019). We suggest that this consolidation together with the increased interconnectedness of organizations allows us to identify three main discursive arenas that bring together key stakeholders of the voluntary carbon market. Namely these are: (1) International Carbon Reduction and Offset Alliance (ICROA), (2) Voluntary Carbon Market Working Group (VCM-WG), and (3) Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets (TSVCM).

Secondly, the research material was compiled. Documents resulting from the debates within these three arenas as well as pertinent publications of their individual members published between late 2015 and early 2021 were considered. Our analysis in Section 5 was informed by a total of 15 policy documents and position papers.

Thirdly, we categorized the main approaches to the voluntary carbon market according to key features in order to identify their commonalities and differences. The approaches were then put in chronological order, allowing to trace the discourse and to delineate its different stages.

Finally, the approaches were analysed and assessed by building upon a broad range of literature that discusses the changes introduced with the Paris Agreement and their political as well a technical consequences for the future operation of the carbon market (e.g. Hermwille & Kreibich, Citation2016; Michaelowa et al., Citation2018; Obergassel et al., Citation2015; Schneider, Füssler, La Hoz Theuer, et al., Citation2017; Schneider et al., Citation2019). The analysis was further complemented by insights from the peer reviewed literature (inter alia:, Blum, Citation2020; Blum & Lövbrand, Citation2019; Lang et al., Citation2019) as well as the literature cited therein] as well as from conducting participatory observation of several pertinent UNFCCC side events, expert workshops and webinars organized by ICROA. The authors observed and contributed to these discussions in their role as experts.

3. Current status of the voluntary market

After some strong initial growth, further expansion of the voluntary carbon market has been stymied for over a decade. Both market volume and market value have been in steady decline since the global economic and financial crisis of 2008/09 (Donofrio et al., Citation2019). This trend continued even after the successful adoption of the Paris Agreement. This may be explained with the continued uncertainty about the viability and legitimacy of voluntary offsetting under the new legal architecture (Hermwille & Kreibich, Citation2016, see also discussion below). The outlook has changed only recently. In 2018 and 2019, the voluntary carbon market saw an increase in both market value and volume after six consecutive years of decline. Overall, voluntary credits representing 104 MtCO2e were traded in 2019 amounting to a cumulative market value of US$320 million (Donofrio et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b).

Especially in its initial phase, demand in the voluntary carbon market was driven by public institutions, namely the World Bank (Bumpus & Liverman, Citation2008). But future demand will be driven in all likelihood by private companies, an increasing number of which have taken on far-reaching net zero or neutrality commitments (Donofrio et al., Citation2020b). Our analysis of 482 large companies that have pledged some form of net zero or neutrality commitment by 2050 or earlier is illustrative in this regard. Collectively, these companies account for annual revenues of more than US$16 trillion, exceeding the gross domestic product (GDP) of China (UN Data, Citation2020). And the number of companies to be included in our analysis grew almost on a weekly basis during our research. Due to the highly dynamic developments and the scarce and dispersed information available, the list should not be considered comprehensive.

All companies we analysed have announced some form of neutrality target, but many of the targets lack clarity in key aspects (Rogelj et al., Citation2021). Moreover, they differ in several ways: Some companies explicitly include all GHG emissions (climate or GHG neutrality), whereas others focus on CO2 emissions only (carbon neutrality). For 97 companies, it remained unclear which GHGs are covered in the commitment. Moreover, while most companies consider all direct and indirect emissions of their own operations (scope 1 and 2), some companies seek to work with their business partners and even include emissions that occur further up or down the supply chain and are beyond their direct control (scope 3). This latter aspect is particularly relevant for several companies of the financial industry, many of which have pledged to extend their commitments to their entire investment portfolios (UNEP Finance Initiative, Citation2020). Also, the pledges differ in their timing. While the vast majority of the companies included in our dataset have a 2050 horizon, some companies, including two of the largest companies in the list, Google and Microsoft, claim that they have already achieved carbon neutrality.Footnote1

For the purpose of this study, the companies’ intention to utilize offsets is the most important difference. Only a small minority of 36 companies have explicitly excluded the use of offsets. 216 companies with a combined annual revenue of more than US$7.5 trillion explicitly intend to offset some remaining emissions. For the remaining 230 companies in our dataset the utilization of offsets remains unclear.

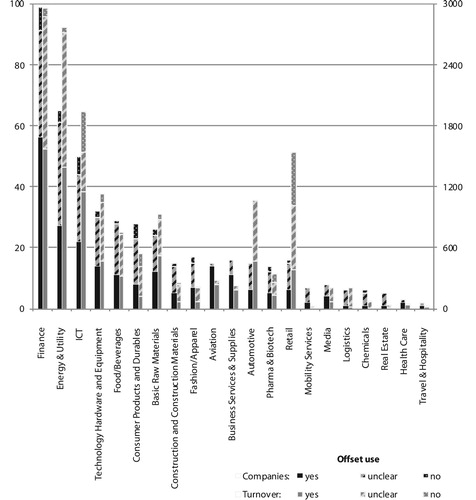

Companies included in the dataset cover a wide range of sectors (see for a breakdown, a complete list is available as supplementary material). For some of these sectors, it may be relatively easy to phase out GHG emissions, e.g. by procuring electricity from renewable energy sources and electrifying transport. This is, for example, the case for companies from the information and communication technology (ICT) industry, manufacturers of technological equipment and hardware, or the financial industry. For these companies, the use of offsets might at most be an interim solution on their way to a full decarbonization of their own operations.

Figure 1. Number of companies with climate/carbon neutrality pledges, their collective annual revenue and their intended use of carbon offsets by industry. Source: Own illustration building on data from ECIU and Oxford Net Zero (ECIU, Citation2021), NewClimate Institute (Citation2020) and the UNFCCC’s NAZCA Platform (UNFCCC, Citation2020).

Meanwhile, the dataset also includes companies whose business model is much more strongly linked to GHG emissions, either because they feature very high GHG emissions per value added and have still a very long path towards decarbonization, or because zero emission alternatives are just not commercially available and, in some cases, not even technically feasible. Examples for the former case include energy industry companies such as Shell, BP or Repsol, mining giant Rio Tinto, or members of the chemical industry such as AkzoNobel. Examples for the latter group include companies from the steel industry, cement industry, aviation industry, or milk and dairy industry. For all of these companies, the use of offsets seems to be the only viable option to achieve carbon or climate neutrality from today’s point of view.

While all these pledges are laudable, significant doubt remains whether the companies will actually implement the necessary instruments to actually achieve them. Machnik et al. (Citation2020), who have reviewed the climate pledges of 44 major European companies, find that their commitments are still not aligned with the objectives of the Paris Agreement and that they are particularly weak in the short term, indicating that major transformations are being postponed. Similarly, Tong and Trout (Citation2020) survey major oil and gas companies and find that across the board they fail to meet minimum criteria such as stopping the exploration of new reserves for credible implementation of their climate pledges (see also Kachi et al., Citation2020). In any case, it is safe to say, that for the majority of the companies listed in our dataset, offsetting will be a key strategy for meeting their commitments. If these plans are implemented, global demand for carbon credits is predicted to grow by several orders of magnitude.

4. The Paris Agreement: a new climate policy paradigm

The adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015 was celebrated as an historic achievement of global climate governance. While the voluntary carbon market mainly evolved in parallel to the international negotiations and is not subject to the UNFCCC rulings, the agreement fundamentally altered the context and the legal architecture under which it operates. In this section, we briefly discuss some of the key features of the Paris Agreement and the changes they brought compared to the previous legal architecture under the Kyoto Protocol that have particular ramifications for the voluntary carbon market.

4.1. Transformative ambition

The Paris Agreement recognizes that climate change is no longer an isolated environmental problem but constitutes a fundamental transformation challenge. Unabated climate change will transform our global economies and societies by a series of unprecedented disasters and slow onset events. A safe and sustainable future can only be achieved through a fundamental transformation into low emission and climate-resilient economies and societies (Hermwille, Citation2016; Kinley, Citation2017).

The transformational ambition of the Paris Agreement is implicit in its long-term objectives. The goal of limiting global warming to ‘well below 2 °C and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels’ (Art. 2.1a, PA, UNFCCC, Citation2016), not only represents a quantitative increase compared to the previous wording but also a re-interpretation of the ultimate objective of the UNFCCC, to avoid dangerous climate change. The long-term goal of the Paris Agreement can only be understood one way: any further global warming is dangerous. It recognizes that the objective is not to gradually reduce emissions but to eradicate them altogether.

For the voluntary carbon market as much as for any other offsetting mechanism this bears the question what ‘additional’ contribution these schemes can deliver when the benchmark for Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) is already to ‘reflect the highest possible ambition’ (Art. 4.3, PA, UNFCCC, Citation2016, see also Michaelowa et al., Citation2019a). In any case, a legitimate use of offsetting under the Paris Agreement needs to contribute to host countries embarking on a transformational pathway. And it must not contribute to further entrench existing high-carbon path dependencies.

This may relate to individual mitigation activities that help to gradually reduce emissions in the short term but lock-in continued emissions for a long period. A drastic example for this would be the building of highly efficient coal power plants. While these may reduce emissions compared to current inefficient generation technologies, it would also cement the continued and unabated consumption of coal and the corresponding carbon emissions for the technical lifetime of the plant. On the other hand, it calls into question the legitimation of the offsetting mechanism itself, if the use of offsets serves as an excuse to continue high-carbon activities and relieves the pressure for low-carbon innovation (see also Carrillo Pineda & Faria, Citation2019).

4.2. Universal scope

One of the reasons for the enthusiastic reactions to the adoption of the Paris Agreement was that it did away with the static differentiation between developing and developed countries (Obergassel et al., Citation2015). The Paris Agreement requires all Parties to ‘prepare, communicate and maintain successive nationally determined contributions [and to] pursue domestic mitigation measures, with the aim of achieving the objectives of such contributions’ (Article 4.2, PA, UNFCCC, Citation2016). This means that all Parties will pursue some type of mitigation activity. At the same time, however, there is no legal obligation for Parties to achieve the mitigation targets adopted as part of their NDCs (Oberthür & Bodle, Citation2016).

This contrasts with the architecture of the Kyoto Protocol, where only Parties listed in Annex B of the protocol – mainly developed countries – had adopted legally binding mitigation targets, leaving a large part of the world unregulated, the so called ‘uncapped environment’. In the past, this uncapped environment was the main source of supply of both the compliance and the voluntary carbon markets. Carbon finance was particularly attractive for host countries without mitigation obligations as they could export the mitigation outcomes achieved by these activities without having to account for the exports. This situation has fundamentally changed under the Paris Agreement: former host countries without mitigation commitments now face an obligation to develop and communicate NDCs which will cover large parts of their economy and implement respective policies. Therefore, the uncapped environment will be much smaller in size, and is set to become even smaller in the future as all Parties are supposed to move towards economy-wide NDCs, as envisaged by the Paris Agreement (Art. 4.4 PA, UNFCCC, Citation2016). The reduced size of the uncapped environment does not necessarily translate into a decrease in supply of carbon credits as these could also be generated from sources covered by an NDC. However, it requires the voluntary carbon market to rethink its business model based on sourcing carbon credits from the uncapped environment.

4.3. Issues with environmental bookkeeping

Mitigation activities implemented within the capped environment contribute (at least in theory) automatically towards the achievement of the host Party’s NDC. The mitigation outcomes generated by a mitigation activity would be claimed against the national target. If the same mitigation outcomes are also claimed on the demand side by the investor (another country or a private sector actor) of the mitigation activity, there would be double claiming, which is considered one form of double counting in the academic literature (Hood et al., Citation2014; Prag et al., Citation2013; Schneider et al., Citation2019). Depending on how the mitigation outcomes are used on the demand side, double counting could raise problems of environmental integrity. If the mitigation outcomes are used by another country for NDC attainment while the reductions are still reflected in the host country’s inventory, double claiming would lead to a net increase in emissions and thereby undermine environmental integrity (Hood et al., Citation2014; Kreibich & Hermwille, Citation2016; Prag et al., Citation2013; Schneider et al., Citation2017; Schneider et al., Citation2019). If, by contrast, mitigation outcomes are used for non-compliance purposes, such as private entities claiming carbon neutrality, double claiming does not automatically lead to a net increase in emissions that undermines environmental integrity, but impacts can be expected to be more nuanced and indirect. In the worst case, global emissions could increase compared to a situation in which a voluntary offset project was not implemented. This can be the case if voluntary activity prompts the host country to relax its own domestic climate ambition (because so much was already achieved by voluntary projects) and emissions also increase in the country in which the buyer is based because demand for high-carbon products and services increases as they are marketed as ‘carbon neutral’, e.g. increased demand for ‘carbon neutral’ flights at the expense of much lower carbon train rides (for a detailed assessment of climate impacts of double claiming see Fearnehough et al., Citation2020).

Despite these different impacts, solutions to avoid double claiming have in the past been developed both within the compliance and the voluntary carbon markets. When Parties negotiated the Paris Agreement and created the possibility for Parties to cooperate in the achievement of their NDCs under Article 6, there was a common understanding that double counting of mitigation outcomes must be avoided. Article 6.2 requires Parties to apply robust accounting when transferring internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs) (Art. 6.2 PA, UNFCCC, Citation2016). Emission reductions from the Article 6.4 mechanism cannot be used ‘to demonstrate achievement of the host Party’s [NDC] if used by another Party to demonstrate achievement of its [NDC]’. With the accompanying decision from Paris, Parties had also agreed that double counting under Article 6.2 should be avoided through ‘corresponding adjustment’, a concept that was explored by many scholars in search for applicable solutions (Greiner et al., Citation2019; Müller & Michaelowa, Citation2019; Schneider et al., Citation2016; Schneider, Füssler, Kohli, et al., Citation2017; Schneider et al., Citation2019). With the adoption of the Katowice climate package at COP24, Parties have partially operationalized the safeguards to prevent double counting under Article 6.2 by requiring Parties to report an emissions balance adjusted on the basis of corresponding adjustments (Kreibich & Obergassel, Citation2019b).

While becoming more salient under the Paris Agreement due to its universal scope, the double claiming risk is not new. Within the compliance markets established under the Kyoto Protocol, a double claiming risk existed for mitigation activities implemented in countries that had adopted mitigation targets: crediting activities hosted by Annex B countries that were registered under Joint Implementation (JI) could issue Emission Reduction Units (ERUs) for every abated ton of CO2e. In order to avoid double counting, the Kyoto Protocol required that Assigned Amount Units (AAUs) equivalent to the amount of ERUs exported to be subtracted from the host country’s account (Foucherot et al., Citation2014; Kreibich & Obergassel, Citation2016).

Under the Kyoto Protocol, the voluntary carbon market also gained experience in dealing with the double claiming risk. Private certification standards, however, adopted different approaches to address the risk. The most prolific voluntary carbon market standard, the VCS, followed the JI principle, requiring an official document from the host country certifying that an amount of AAUs equivalent to the number of credits to be issued had been cancelled (VCS, Citation2012). Under the Gold Standard, a desk-review is conducted to establish if there is a risk of double counting. If the review finds that there is a double counting risk, the project proponent must either demonstrate that this risk does not exist, it has been addressed externally, or it commits to cancel AAUs in lieu of the Gold Standard voluntary mitigation outcomes to be issued (Gold Standard, Citation2015). The CCB Standards require convincing proof that the issue of double counting has been avoided, while under the CarbonFix Standard the issue is resolved by negotiations on a case-by-case basis with the authorities during certification (see Foucherot et al., Citation2014). So while the private certification standards of the voluntary carbon market used different approaches in dealing with the double claiming risk (Michaelowa et al., Citation2018), this can be seen as an indication of the consciousness among voluntary carbon market participants to address the double claiming risk.

In conclusion, this allows us to draw the following observations: under the Kyoto Protocol, there was a common understanding that double claiming is a risk that should be avoided and private certification standards have developed different approaches to deal with the issue. With the adoption of the Paris Agreement, there is a general agreement that double claiming must also be avoided in future compliance markets.

5. In search of solutions: tracing the debate

This section traces the debate within the voluntary carbon market community on how to deal with the double claiming issue. It analyses the debate in three main discursive arenas: ICROA, the VCM-WG and the TSVCM.

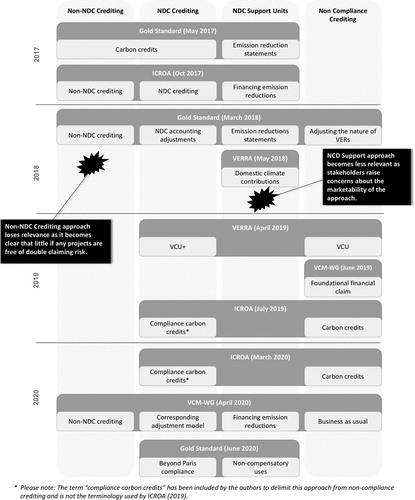

ICROA is a network organization comprising the largest offset providers and certification standards in the voluntary carbon market. The VCM-WG was convened by the Gold Standard with the support of the German government, bringing together civil society organizations, carbon market actors from the private sector and private certification standards, to reflect on the role and design of the voluntary carbon market post-2020.Footnote2 The TSVCM is a private-sector initiative working to scale and consolidate the voluntary carbon market to help meet the objectives of the Paris Agreement. It was initiated by Mark Carney, UN Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance Advisor to UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson for the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26). The Taskforce’s members represent buyers and sellers of carbon credits, standards setters, the financial sector as well as market infrastructure providers (TSVCM, Citation2021). Unlike ICROA and the VCM-WG, the TSVCM therefore also includes private companies from the demand side. This is remarkable, as in the past these actors have not engaged directly in the debate and their views were mainly brought forward by carbon credit suppliers and certification standards. The analysis traces the debate in these three arenas and how it evolved over time. Overall four different approaches for the future of the voluntary carbon market in the Paris era have been proposed. provides an overview of their main chararcteristics. The subsequent analysis traces the debate through six stages. It should be noted though, that these stages do not follow a strict chronological order and that there are overlaps between them.

Table 1. Overview of main approaches currently under discussion. As can be seen, the ‘non-compliance credits’ approach combines characteristics of two other approaches.

5.1. Understanding the challenge

Soon after the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015, key voluntary carbon market participants realized the implications the new agreement with its global scope could have on their business models. Among the first was the Gold Standard, identifying the double counting risk as a ‘life-threatening challenge’ (Gold Standard, Citation2017) for the voluntary carbon market, a perception shared by several other market participants. In a survey by market observer Ecosystem Marketplace, double claiming and double counting are perceived as the main risks for the voluntary market post-2020 (see also Hamrick & Gallant, Citation2017; Hermwille & Kreibich, Citation2016).

With the broader realization of this threat, thinking about alternative approaches kicked-off. Shifting from the mere offsetting logic towards assisting developing countries in achieving their NDC has been identified as one idea in the legitimation process (Blum, Citation2020). In this process, the Gold Standard suggested the development of ‘certified statements of emission reductions’ as a new product that would certify a contribution to achieving the host country target but could not be used as offsets to support neutrality claims. For this approach, which is also referred to as financing emission reductions model or contribution claim approach, we will use the term ‘NDC support units’. Notably, these new statements are seen as an addition and not a substitute for carbon credits. Carbon credits would still be issued on the basis of corresponding adjustments and could still be used for claiming carbon neutrality (Gold Standard, Citation2017).

5.2. A first phase of consolidation

In what could be described as a first phase of consolidation, ICROA published a guidance document providing an overview on the different approaches currently under discussion. The document makes a more nuanced differentiation between the possible solutions, clearly highlighting where corresponding adjustments are needed and what this could mean for carbon neutrality claims. The guidance document proposes three approaches: (1) an NDC crediting model that would require the implementation of corresponding adjustments, (2) a non-NDC crediting model where mitigation outcomes are generated outside the scope of NDCs, and (3) a financing model where mitigation outcomes would be owned by the host country.

According to this guidance document, only the first two models could be used for carbon neutrality purposes, requiring mitigation outcomes to be either achieved outside the scope of Parties’ NDCs (non-NDC crediting) or accounted for through corresponding adjustments (NDC crediting model). The financing mitigation outcomes model, by contrast, ‘would not allow non-state actors to make environmental claims, such as being carbon neutral. This is because the Party is receiving private sector assistance to achieve its climate goals, and that action does not create reductions beyond the target’ (ICROA, Citation2017).

5.3. Disillusionment and emergence of new ideas

In 2018, the Gold Standard together with other organizations developed and tested a tool to assess the exposure of voluntary market projects to double claiming. The tool was to answer whether the mitigation outcomes to be issued could also be captured under the host country NDC, thereby leading to double claiming. The findings of the test, which were summarized in a publicly available report (Gold Standard, Citation2018), clearly show that there are only very rare cases where it can be demonstrated that double counting is ruled out with certainty. The report also highlighted that it will be difficult to ensure that the host country will not account for the impact of the voluntary project in the future. This indicates that double claiming will be an issue for many, if not all projects (Gold Standard, Citation2018).

While the testing of the tool highlighted the practical challenges of the non-NDC crediting approach, political concerns about this approach had already been raised earlier. Numerous observers had highlighted the risk that non-NDC crediting could lead to disincentives for host countries to expand the scope of their NDCs (see e.g. Kreibich, Citation2018; Schneider & La Hoz Theuer, Citation2018; Spalding-Fecher, Citation2017; Warnecke et al., Citation2018). New accounting approaches emerged that called for mitigation outcomes to be accounted for through corresponding adjustments even if generated outside the scope of an NDC (Japan, Citation2017, for an overview see: Schneider, La Hoz Theuer, et al., Citation2020). While originating in the context of the Article 6 rulebook, these discussions also found their way into the voluntary carbon market discourse (see ICROA, Citation2017).

With this, the non-NDC crediting model significantly lost relevance in the discussion while the NDC support model gained more ground within the community. In a proposal for public consultation, VERRA – the organization managing the VCS Standard – outlines the idea of creating Domestic Climate Contributions (DCCs) under their VCS Programme as a means to avoid the need for securing corresponding adjustments and developing double counting rules (VERRA, Citation2018).

The disillusionment regarding the operationalization of the non-NDC crediting, however, did not lead to the emergence of a binary model with NDC support units as an alternative to carbon credits used for offsetting. Instead, the concept of a new type of ‘voluntary credit’ that does not require the implementation of corresponding adjustments was introduced. This emerged in the context of the stakeholder discussions led by the Gold Standard. The new credit type would presumably not be applicable to carbon neutrality claims in their current form, but instead require a change in the definition of carbon neutrality (Gold Standard, Citation2018). Clarity on how carbon neutrality could be redefined is, however, lacking (Carrillo Pineda & Faria, Citation2019; Luhmann & Obergassel, Citation2020). With this new approach, the clear distinction between credits certifying ownership of mitigation outcomes that could be used for offsetting on the one hand, and attribution of mitigation outcomes to be used for claiming a financial contribution on the other, was increasingly blurred.

5.4. Disclosure of diverging positions

The idea to issue carbon credits without having to implement corresponding adjustments and to introduce an attribute that distinguishes these carbon credits from those backed by corresponding adjustments was also taken up by VERRA in 2019. One reason for exploring this route was the feedback received from stakeholders, who feared difficulties of introducing emission reductions statements as a new product to the market (VERRA, Citation2019). These concerns are shared by numerous players in the market, who highlight that it had taken more than a decade to establish the concepts of offsetting and carbon neutrality (Kreibich & Obergassel, Citation2019a).

Given these challenges, VERRA put its financing mitigation outcomes model (the DCCs proposal) on hold and instead started thinking about introducing an attribute to distinguish a VCU from a new compliance-grade unit (VCU+). While an existing credit ‘would remain a purely voluntary unit as it always has’ (VERRA, Citation2019), a VCU+ would comply with any requirements of future compliance regimes, such as the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), including corresponding adjustments. This implies that conventional carbon credits used for voluntary purposes would not require corresponding adjustments to be implemented. If adopted, VCS would clearly deviate from the current approach of addressing double claiming (see above for the VCS accounting provisions under the Kyoto Protocol). However, VERRA underscores that the use of carbon credits for specific claims by corporate users is still under discussion and that thinking on this concept is early and ongoing (VERRA, Citation2019).

The idea to establish two types of carbon credits – one for compliance use and one for purely voluntary use – continued to dominate the debate among voluntary carbon market players through early 2019, also finding its way into a broader consultation process supported by the German government. In June 2019, the VCM-WG published a first statement for consultation with the broader community. The statement, which was explicitly not labelled as a formal position of the individual members of the group, differentiates between voluntary credits for compliance use and purely voluntary credits, putting the focus on the latter. For these credits, the statement proposes to retain the infrastructure of the voluntary carbon market – including the issuance of carbon credits – while at the same time avoiding the need to implement corresponding adjustments. While the document puts the financial claim at its centre, it does not explicitly rule-out the possibility for these voluntary credits to be used for offsetting and carbon neutrality claims, but instead indicates that claims would have to be reviewed and potentially adjusted at a later stage (VCM-WG, Citation2019c).

The document was presented in a public webinar (VCM-WG, Citation2019b) in June 2019 and written feedback from stakeholders was sought in a public consultation, displaying a large diversity of views (VCM-WG, Citation2019a). In light of the continued relevance of offsetting, some organizations criticized the fact that the approach put forward by the VCM-WG does not explicitly rule out offsetting on the basis of credits that are not backed up by corresponding adjustments and that the document does not answer the question of which claims investors can make (atmosfair, Citation2019; VCM-WG, Citation2019a). On the other side of the spectrum, some organizations called for the document to more explicitly allow for double claiming (I4CE in VCM-WG, Citation2019a).

Following the debate among voluntary market participants, the VCM-WG statement was updated in October 2019 (VCM-WG, Citation2019d). The updated version acknowledges that the predominant use of the voluntary carbon market is currently for offsetting and that it will explore ‘what further provisions the credits may require in order to be used in the context of offsetting’ (VCM-WG, Citation2019d). Thus, while the document itself was ambiguous regarding how to deal with double claiming, it nurtured the discussion within the community showing that some organizations are clearly opposing any type of double claiming while others think that double claiming should be allowed.

5.5. Cutting corners

Allowing for double claiming within the voluntary carbon market is also the position included in ICROA’s position paper from July 2019 (ICROA, Citation2019). With this document, ICROA abandons positions included in its earlier guidance document from 2017. While also differentiating between mitigation outcomes for compliance purposes and voluntary carbon credits, ICROA argues in favour of voluntary credits being used to make carbon neutrality claims even without corresponding adjustments having been implemented. One of ICROA’s key arguments why the integrity of voluntary action and carbon neutrality claims under the Paris Agreement is maintained without corresponding adjustments is that mitigation outcomes are only counted once at the UN level: mitigation outcomes are not exported from the host country to the jurisdiction in which the corporate buyer is based and only the host country reports the reductions to the UNFCCC, while corporate GHG accounts are not reported and aggregated to a country level.

In its position paper published in March 2020 (ICROA, Citation2020), ICROA reiterates and reinforces its previous position not to require corresponding adjustments in the context of the voluntary use of carbon markets. The paper builds on ICROA’s previous argument that the mitigation outcomes used for non-compliance purposes are only recorded once at the UNFCCC level and can therefore not lead to double counting, which allows to preserve the integrity of the voluntary carbon market without requiring corresponding adjustments. The paper reinforces this argument by showing that double claiming is already happening today in jurisdictions where unregulated corporates voluntarily reduce their emissions to achieve a voluntary climate target, such as a Science-Based Target. The mitigation outcomes generated by the voluntary action will not only be claimed by the corporate to meet its voluntary target but also by the government of the country where the corporate is based, as the reductions will be reflected in its inventory and hence reported to the UNFCCC. According to ICROA, this situation is comparable to double claiming within the voluntary carbon market (ICROA, Citation2020).

5.6. Finding common ground

Discussions within and between organizations are ongoing. The latest statement by the VCM-WG published in May 2020 reflects the latest status of the debate and brings together the diverse approaches discussed over the last years:

non-NDC crediting,

NDC crediting, now renamed corresponding adjustment model,

NDC support, now called financing emission reductions model, and

non-compliance crediting, discussed as ‘business as usual model’.

In this paper, the working group distances itself from the first version of its 2019 statement that left open whether credits without corresponding adjustments could be used for offsetting and claiming carbon neutrality. In stark contrast to this earlier statement, the latest paper highlights risks associated to crediting without corresponding adjustments and differentiates double claiming in the carbon market from other forms of ‘double reporting’. Notably and in stark contrast to ICROA’s position paper, the VCM-WG highlights that ‘there is a key difference between [these types of double reporting] and the carbon market in that they do not represent double claiming at a “target” level and do not make claims that the impact being driven by the action is “additional” to the efforts at country level’ (VCM-WG, Citation2020). While highlighting that there is no agreement within the working group and among stakeholders,Footnote3 the VCM-WG paper finally outlines a transition towards a future voluntary carbon market in which corresponding adjustments are required for credits used for offsetting and which operates in parallel to a financing mitigation outcomes model.

This vision of a future that differentiates between two claims is made more explicit in the Gold Standard document published in June 2020 for consultation. In this document, the Gold Standard promotes a differentiation between ‘Beyond’ Paris-compliance units for use in offsetting claims and units for other uses that have non-compensatory benefits (Gold Standard, Citation2020).

While discussions about the future role of carbon markets are ongoing, a new taskforce was formed in September 2020. This Taskforce for Scaling the Voluntary Carbon Markets published a consultation document in November 2020 (TSVCM, Citation2020). Notably, the focus of the document is mainly on procedural and contractual issues while key open questions regarding the future operation of the voluntary carbon market along host Parties’ NDCs are not part of the consultation. The document states that the taskforce cannot deliver policy guidance on corresponding adjustments as this is a matter subject to ongoing international negotiations. At the same time, however, it states that ‘corporate and national emissions accounting can exist separately’ and that carbon neutrality claims could be made on the back of mitigation outcomes if claims indicate that mitigation outcomes will remain part of the host country’s emissions balance. The document further states that double counting at the national level should be avoided, which implies that double counting between the corporate level (on the demand side) and the national level (on the supply side) could be allowed. Strikingly, the consultation note considers corresponding adjustments only as an ‘additional attribute’ and not as one of the core carbon principles to which all credits, supporting standards and methodologies must adhere.

In January 2021, the TSVCM published a final report also reflecting the responses received during the public consultation. However, the taskforce has not compiled and published the more than 160 responses received during the process, which does not allow for an in-depth analysis of respondents’ positions regarding corresponding adjustments. Yet, the text sections referring to the role of corresponding adjustments included in the final report remain unchanged from those in the consultation document. The taskforce instead commissioned the consultancy firm Trove Research to further explore the issue of corresponding adjustments by evaluating the implications of the Article 6 negotiations on the voluntary carbon market (TSVCM, Citation2021).

6. Discussion and conclusions

In this paper, we have outlined how the context of the voluntary carbon market has changed with the adoption of the Paris Agreement and we have traced the struggle of the main actors in dealing with these changes in order to reposition the voluntary carbon market.

A key question to be answered in light of the Paris Agreement’s transformative ambition is whether voluntary carbon offsetting can support the transition on the demand side, the transition of the companies that purchase the offsets. Our analysis shows that there is a growing interest among the private sector to become carbon or climate neutral: as of April 2021, 482 companies accounting for an estimated annual revenue of US$16 trillion have adopted some kind of neutrality target. Many companies have included offsetting as a key component of their climate change mitigation strategy.

While these numbers are impressive and might indicate the emergence of an unprecedented future demand for carbon credits, the role of credits within corporate climate strategies should be observed cautiously. A situation must be avoided in which companies use voluntary carbon offsetting as an ‘easy’ way out of their responsibility to act on climate change. One idea that has been proposed in this context is to make the use of carbon credits conditional on the adoption of science-based targets for the respective company. While such a provision would not per se address the issue of double counting it could prevent companies from using carbon credits instead of implementing mitigation activities within their own operations. However, a question still to be answered is how such a provision could be effectively enforced. While certification schemes could in principle establish such requirements for the use of the credits they issue, it does not seem plausible that they can effectively enforce the provision on their own. Instead, a collaboration between major private certification schemes and corporate climate action initiatives seem promising in this regard, such as the cooperation between Gold Standard and the Science-Based Targets initiative that has already been initiated (Gold Standard, Citation2020).

The second major issue to be discussed is whether the voluntary carbon market has found its place within the architecture of the Paris Agreement, a place that acknowledges the universal scope of the Agreement and ensures the overall integrity of climate action. The analysis of the debate within the voluntary carbon market shows that different approaches for dealing with the double claiming issue have emerged, each of them having its own characteristics in terms of environmental integrity, practicality and marketability.

Non-NDC crediting, i.e. crediting projects in the ‘uncapped environment’ outside the scope of the host country’s NDC without implementing corresponding adjustments, is severely limited in scope and can cause perverse incentives on host countries (not) to extend their policies and targets. Moreover, there are considerable practical challenges that raise doubts. As discussed above, it appears to be challenging to clearly establish what is inside or outside both the current NDC, because in many cases the information provided in the NDCs is insufficient to draw clear boundaries, as well as in future NDCs (Schneider, La Hoz Theuer, et al., Citation2020).

Most importantly, though, the non-NDC crediting approach is incommensurate with the ambition of the Paris Agreement, at least in the long run. Art. 4.4 of the Paris Agreement stipulates that Parties are ‘encouraged to move over time towards economy-wide emission reduction or limitation targets’. If we take this aspect of the Paris Agreement’s ambition mechanism seriously, the already limited scope will be diminished further.

NDC support units that provide a label for projects that contribute to the achievement of a host country’s NDC but cannot be used for compensation purposes do not seem to be in demand. Establishing this new product on the market would require significant (and joint) efforts from all market participants. This approach, which is also referred to as the financing emission reductions model or contribution claim approach would essentially constitute a form of private results-based climate finance. This potential new market can by definition not meet the demands from companies trying to meet their net zero commitments as the units must not be used for neutrality claims. Still, there might be a niche market for such products in the future. Findings from previous research indicate that large companies, in particular those operating at a global level, might be interested in supporting a specific country in implementing its NDC. The model might also find the interest of companies and individuals that have in the past refrained from investing in carbon offsets due to environmental justice debates surrounding the offsetting approach. Buyers whose business model builds on the provision of carbon neutral products, by contrast, can be expected to be more reluctant to buy this new type of product (Kreibich & Obergassel, Citation2019a).

Non-compliance credits, i.e. units that can be used to support neutrality claims but are not reflected through corresponding adjustments in the official emissions bookkeeping under the UNFCCC, face serious legitimacy concerns and lead to double claiming which in turn could result in increased emissions overall. Not only is it questionable to what extent they can actually address financial or reputational risks of companies buying those credits, but it can also distort our perception of global collective action.

Finally, we deem that NDC crediting with corresponding adjustments is the only solution that strengthens and protects the legitimacy of using carbon credits for offsetting in the context of carbon neutrality targets while ensuring a high degree of environmental integrity. Whether it will be feasible for the voluntary carbon market is not a technical question, but a political one, as it remains to be seen whether and when host countries will actually be willing to implement corresponding adjustments. Since corresponding adjustments will make NDC attainment more difficult, host countries can be expected to be unwilling to implement these adjustments unless the mitigation outcomes are generated by activities that are truly additional and help them to stay on their long-term decarbonization pathway (for a discussion on how to deal with additionality under Article 6 see: Michaelowa et al., Citation2019b).

above illustrates the evolution of the discourse on the future of the voluntary carbon market. The analysis of the discourse finds that the perceived risk associated to double claiming varies significantly among key stakeholders of the voluntary market resulting in a stalemate that prevented the development of a common position. It also reveals that the position of some stakeholders has changed fundamentally in the course of the debate when it became apparent that buyers had little appetite to invest in alternative products such as NDC support units and that the implementation of corresponding adjustments under the Paris Agreement could be associated with practical challenges.

Figure 2. Role of individual approaches in the evolution of the discourse on the future of the voluntary carbon market. Source: own illustration. * Please note that the term ‘compliance carbon credits’ was included by the authors to delimit this approach from non-compliance crediting. It is not the terminology used by ICROA (2019).

The challenges with the NDC crediting approach are largely political and cannot be resolved by the voluntary carbon market on its own. There is a need for support through public policy to assist the implementation of the approach. At the international level, policymakers will have to make sure that the accounting framework for Article 6 enables corresponding adjustments for voluntary purposes and that it can be easily used by the countries hosting voluntary market activities.

Furthermore, bilateral policy activities could assist the voluntary market in dealing with the expected difficulties in obtaining a permission from host countries to export mitigation outcomes backed by corresponding adjustments. One possible solution in dealing with this problem could be bilateral agreements between host countries and those countries where the buyer of the offset credit is based. Such an agreement could be useful despite the fact that the use of mitigation outcomes for voluntary purposes (as well as for CORSIA) does only require an adjustment of the emissions balance by the host country while no such adjustment is needed from the country in which the buyer is based. Obtaining such a ‘unilateral corresponding adjustment’ could be facilitated through a bilateral agreement between governments. More generally, public policy could take a supportive role by publicly endorsing the NDC crediting model as the only approach that should be used in the context of carbon neutrality claims. Such an approach is not unprecedented: for example, the UK government has not allowed companies to use Woodland Carbon Units for carbon offsetting purposes, as the underlying mitigation impact would also contribute to UK’s mitigation targets under the UNFCCC (HM Government, Citation2019).

While the NDC crediting approach requires political support from potential host countries, project developers and offset providers are not altogether incapacitated to further advance the approach. As a first step, voluntary market actors could agree on making corresponding adjustments a requirement for the issuance of all credits, irrespective of their origin. Once this decision has been taken, innovative solutions that make it easier for host countries to commit to making corresponding adjustments could be developed. A straightforward way of doing so would be to issue carbon credits only retroactively after the conclusion of the NDC period and on the condition that the host country has (over)achieved its NDC. Of course, this would pose a considerable risk for project developers and investors. But there might also be advanced solutions involving some form of insurance or pool reserve to share the risk of overselling between host countries and project developers.

Overall, our analysis highlights a big discrepancy between the seemingly gigantic potential demand for carbon credits and the ability of the established certification schemes to supply credits legitimately and in a way that supports the objectives of the Paris Agreement without undermining them. It is encouraging that the main actors are participating in structured debate even if no common position has been found to date. Still, the voluntary market stands at a crossroads with key actors looking in opposite directions. On the one hand, some actors continue promoting the non-compliance credits approach, a proposal that in our view does not only pose serious integrity risks but could also undermine the credibility of the entire voluntary carbon market. On the other hand, several entities are exploring possibilities to establish NDC support units as a new product on the market which would be traded in parallel to voluntary offsetting credits backed by corresponding adjustments. Discussions are ongoing and new initiatives, such as the public consultations recently launched by VERRA (Citation2020), the Gold Standard (Citation2021) and Trove Research (Citation2021), could contribute to finding a common position among key voluntary carbon market players. If, however, the main actors in the voluntary carbon market do not unite behind an approach based on corresponding adjustments, they risk losing ground altogether. If they fail to get the required political support, the voluntary carbon market may become obsolete or worse, a threat to effective climate change mitigation.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (66.6 KB)Acknowledgements

This article builds on research carried out in the context of the project listed under ‘funding’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Obviously, the differences in the various net zero or neutrality strategies may have significant implications for the future demand of offsets. But since we were even unable to obtain complete and reliable data on the current GHG emissions of the listed companies, we decided not to further differentiate between the different strategies in our analysis.

2 The VCM-WG comprises WWF, The Nature Conservancy, World Resources Institute, CDP, Carbon Market Watch, ICROA, Gold Standard and Verra.

3 According to the VCM-WG, three groups can be differentiated: (1) a group calling for corresponding adjustments to be required for all internationally transferred credits, (2) a group supporting the transition towards corresponding adjustments, and (3) those maintaining that double claiming is not an issue and therefore advocate for the continuation of ‘business as usual’.

References

- atmosfair. (2019). Feedback of atmosfair responding to the Gold Standard public consultation on the “Working group statement on the future role and design of the voluntary carbon market to support the goals of the Paris Agreement”. Received March 23, 2020, from https://www.atmosfair.de/wp-content/uploads/atmosfair-feedback-vcm-post2020-1.pdf

- Bäckstrand, K., & Lövbrand, E. (2006). Planting trees to mitigate climate change: Contested discourses of ecological modernization, green governmentality and civic environmentalism. Global Environmental Politics, 6, 50–75. Received February 15, 2021, from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2006.6.1.50

- Bellassen, V., & Leguet, B. (2007). The emergence of voluntary carbon offsetting. (Report No.: 11). auto-saisine; p. 36. Received February 19, 2021, from https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01190163

- Black, R., Cullen, K., Fay, B., Hale, T., Lang, J., Saba, M., Smith, S. (2021). Taking stock: A global assessment of net zero targets. Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit and Oxford Net Zero. Retrieved March 29, 2021, from https://ca1-eci.edcdn.com/reports/ECIU-Oxford_Taking_Stock.pdf?mtime=20210323005817&focal=none

- Blum, M. (2020). The legitimation of contested carbon markets after Paris – empirical insights from market stakeholders. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(2), 226–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1697658

- Blum, M., & Lövbrand, E. (2019). The return of carbon offsetting? The discursive legitimation of new market arrangements in the Paris climate regime. Earth System Governance, 2, 100028. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2589811619300278. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esg.2019.100028

- Broekhoff, D., Gillenwater, M., Colbert-Sangree, T., Cage, P. (2019). Securing climate benefit: A guide to using carbon offsets. 60. http://www.offsetguide.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Carbon-Offset-Guide_3122020.pdf

- Bumpus, A. G., & Liverman, D. M. (2008). Accumulation by decarbonization and the governance of carbon offsets. Economic Geography, 84, 127–155. Retrieved February 19, 2021, from http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2008.tb00401.x

- Carrillo Pineda, A., & Faria, P. (2019). Towards a science-based appraoch to climate neutrality in the corporate sector. Science-based Targets Initiative | CDP. Retrieved May 5, 2020, from https://sciencebasedtargets.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Towards-a-science-based-approach-to-climate-neutrality-in-the-corporate-sector-Draft-for-comments.pdf

- Corbera, E., Estrada, M., & Brown, K. (2009). How do regulated and voluntary carbon-offset schemes compare? Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences, 6, 25–50. Retrieved February 19, 2021, from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15693430802703958

- Donofrio, S., Maguire, P., Merry, W., Zwick, S. (2019). Financing emissions reductions for the future – state of the voluntary carbon markets 2019. Forest Trends. Retrieved March 30, 2020, from https://hubs.ly/H0m5qf60

- Donofrio, S., Maguire, P., Zwick, S., Merry, W. (2020a). Voluntary carbon and the post-pandemic recovery. Forest Trends. Retrieved March 30, 2020, from https://www.ecosystemmarketplace.com/carbon-markets/

- Donofrio, S., Maguire, P., Zwick, S., Merry, W. (2020b). The only constant is change – state of the voluntary carbon markets 2020, Second Installment. Forest Trends, p. 23. Retrieved February 24, 2021, from https://share.hsforms.com/1FhYs1TapTE-qBxAxgy-jgg1yp8f

- ECIU. (2021). Oxford Net Zero. Net Zero Tracker. Retrieved April 6, 2021, from https://eciu.net/netzerotracker

- Fearnehough, H., Kachi, A., Mooldijk, S., Warnecke, C., Schneider, L. (2020). Future role for voluntary carbon markets in the Paris era. 94. https://www.carbon-mechanisms.de/fileadmin/media/dokumente/Publikationen/Bericht/2020_11_19_cc_44_2020_carbon_markets_paris_era.pdf

- Foucherot, C., Grimault, J., & Mo, R. (2014). Contribution from I4CE on how to address double counting within voluntary projects in Annex B countries. Retrieved March 30, 2020, from https://www.i4ce.org/wp-core/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/I4CE-Note-UQA-Nov2015-VA-291015.pdf

- Gillenwater, M., Broekhoff, D., Trexler, M., Hyman, J., & Fowler, R. (2007). Policing the voluntary carbon market. Nature Climate Change, 1(711), 85–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/climate.2007.58

- Gold Standard. (2015). Double counting guideline. Retrieved March 24, 2020, from https://www.goldstandard.org/sites/default/files/documents/2015_12_double_counting_guideline_published_v1.pdf

- Gold Standard. (2017). A new paradigm for voluntary climate action: ‘Reduce within, finance beyond’. Retrieved February 16, 2018, from https://www.goldstandard.org/sites/default/files/documents/a_new_paradigm_for_voluntary_climate_action.pdf

- Gold Standard. (2018). Future proofing the voluntary carbon markets – double counting Post-2020 – a tool for assessing the exposure of projects to double counting. Retrieved February 12, 2020, from https://www.goldstandard.org/sites/default/files/documents/future_proofing_the_voluntary_carbon_market_double_counting_final_report.pdf

- Gold Standard. (2020). Operationalising and scaling Post-2020 voluntary carbon market – consultation. p. 19. https://www.goldstandard.org/sites/default/files/documents/2020_gs_vcm_policy_consultation.pdf

- Gold Standard. (2021). Integrity for scale: Aligning Gold Standard projects with the Paris Agreement. Retrieved February 22, 2021, from https://www.goldstandard.org/our-work/innovations-consultations/integrity-scale-aligning-gold-standard-projects-paris-agreement

- Greiner, S., Chagas, T., Krämer, N., Michaelowa, A., Brescia, D., Hoch, S. (2019). Article 6 corresponding adjustments: Key accounting challenges for Article 6 transfers of mitigation outcomes. Climate Focus and Perspectives Climate Group. https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-175360

- Hamrick, K., & Gallant, M. (2017). Unlocking potential – state of the voluntary carbon markets 2017. http://www.forest-trends.org/documents/files/doc_5591.pdf

- Hermwille, L. (2016). Climate change as a transformation challenge – a new climate policy paradigm? GAIA – Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 25(1), 19–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.25.1.6

- Hermwille, L., & Kreibich, N. (2016). Identity crisis? Voluntary carbon crediting and the Paris Agreement. Wuppertal. http://www.carbon-mechanisms.de/en/2017/what-future-for-voluntary-carbon-markets/

- HM Government. (2019). Environmental reporting guidelines: Including streamlined energy and carbon reporting guidance, p. 152. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/850130/Env-reporting-guidance_inc_SECR_31March.pdf

- Hood, C., Briner, G., & Rocha, M. (2014). GHG or not GHG: Accounting for diverse mitigation contributions in the Post-2020 climate framework. OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development)/IEA (International Energy Agency). Retrieved September 10, 2015, from http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/file/GHG%20or%20not%20GHG.pdf

- ICROA. (2017). Guidance report: Pathways to increased voluntary action by non-state actors. Retrieved March 6, 2018, from http://www.icroa.org/resources/Documents/ICROA_Pathways%20to%20increased%20voluntary%20action.pdf

- ICROA. (2019). ICROA’s position on scaling private sector voluntary action post-2020. Retreived July 1, 2021, from https://www.icroa.org/resources/Documents/ICROA_Voluntary_Action_Post_2020_Position_Paper_July_2019.pdf

- ICROA. (2020). ICROA’s position on scaling private sector voluntary action post-2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020, from https://www.icroa.org/resources/Documents/ICROA_Voluntary_Action_Post_2020_Position_Paper_March_2020.pdf

- Japan. (2017). Japan’s submission on SBSTA item 10(a) – guidance on cooperative approaches referred to in Article 6, paragraph 2, of the Paris Agreement (2 October 2017). Retrieved March 7, 2018, from http://www4.unfccc.int/sites/SubmissionPortal/Documents/579_344_131516859040704385-Japan_Submission_6.2_20171002.pdf

- Kachi, A., Mooldijk, S., & Warnecke, C. (2020). Climate neutrality claims. NewClimate Institute, p. 23. Retrieved October 5, 2020, from https://newclimate.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Climate_neutrality_claims_BUND_September2020.pdf

- Kinley, R. (2017). Climate change after Paris: From turning point to transformation. Climate Policy, 17(1), 9–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2016.1191009

- Kreibich, N. (2018). Raising ambition through cooperation: Using Article 6 to bolster climate change mitigation. Wuppertal Inst. for Climate, Environment and Energy.

- Kreibich, N., & Hermwille, L. (2016). Robust transfers of mitigation outcomes – understanding environmental integrity challenges (Report No.: 02/2016). Wuppertal Institut für Klima, Umwelt, Energie. Retrieved August 8, 2016, from https://www.carbon-mechanisms.de/en/publications/details/?jiko%5Bpubuid%5D=464

- Kreibich, N., & Obergassel, W. (2016). Carbon markets after Paris – how to account for the transfer of mitigation results? (Report No.: 01/2016). Retrieved January 1, 2017, from http://www.carbon-mechanisms.de/en/publications/details/?jiko%5Bpubuid%5D=131&cHash=ed81ec1a196649472c70989842b1889f

- Kreibich, N., & Obergassel, W. (2019a). The voluntary carbon market: What may be its future role and potential contributions to ambition raising? German Emissions Trading Authority (DEHSt). https://www.dehst.de/SharedDocs/downloads/EN/project-mechanisms/discussion-paper_bonn-2019_4.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2

- Kreibich, N., & Obergassel, W. (2019b). Article 6.2 and the Transparency Framework. p. 38.

- Lang, S., Blum, M., & Leipold, S. (2019). What future for the voluntary carbon offset market after Paris? An explorative study based on the discursive agency approach. Climate Policy, 19(4), 414–426. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1556152

- Lovell, H., Bulkeley, H., & Liverman, D. (2009). Carbon offsetting: Sustaining consumption? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 41(10), 2357–2379. Retrieved February 19, 2021, from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1068/a40345 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/a40345

- Luhmann, H.-J., & Obergassel, W. (2020). Klimaneutralität versus Treibhausgasneutralität: Anforderungen an die Kooperation im Mehrebenensystem in Deutschland. GAIA – Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 29(1), 27–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.29.1.7

- Machnik, D., Sun, P., & Tänzler, D. (2020). Climate neutrality targets of European companies and the role of carbon offsetting. Adelphi, p. 60.

- Michaelowa, A., Hermwille, L., Obergassel, W., & Butzengeiger, S. (2019a). Additionality revisited: Guarding the integrity of market mechanisms under the Paris Agreement. Climate Policy, 19(10), 1211–1224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1628695

- Michaelowa, A., Hermwille, L., Obergassel, W., & Butzengeiger, S. (2019b). Additionality revisited: Guarding the integrity of market mechanisms under the Paris Agreement. Climate Policy, 1–14. Retrieved September 24, 2019, from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14693062.2019.1628695

- Michaelowa, A., Shishlov, I., & Espelage, A. (2018). Theory and international experience on voluntary carbon markets, p. 50. https://www.perspectives.cc/fileadmin/Publications/Michaelowa_et_al._2019_-_Theory_and_international_experience_on_VCMs.pdf

- Müller, B., & Michaelowa, A. (2019). How to operationalize accounting under Article 6 market mechanisms of the Paris Agreement. Climate Policy, 1–8. Retrieved May 6, 2019, from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14693062.2019.1599803

- NewClimate Institute. (2020). Ambitious climate actions and targets by countries, regions, cities and businesses. Retrieved April 2, 2020, from https://newclimate.org/ambitiousactions

- Obergassel, W., Arens, C., Hermwille, L., Kreibich, N., Mersmann, F., Ott, H. E., Wang-Helmreich, H. (2015). Phoenix from the ashes: an analysis of the Paris Agreement to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; part 1. Environmental Law and Management, 27, 243–262.

- Oberthür, S., & Bodle, R. (2016). Legal form and nature of the Paris outcome. Climate Law, 6(1-2), 40–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1163/18786561-00601003

- Prag, A., Hood, C., & Barata, P. M. (2013). Made to measure: Options for emissions accounting under the UNFCCC. Retrieved August 12, 2015, from http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/environment-and-sustainable-development/made-to-measure-options-for-emissions-accounting-under-the-unfccc_5jzbb2tp8ptg-en

- Rogelj, J., Geden, O., Cowie, A., & Reisinger, A. (2021). Net-zero emissions targets are vague: Three ways to fix. Nature, 591(7850), 365–368. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-00662-3

- Schneider, L., Broekhoff, D., Cames, M., Füssler, J., La Hoz Theuer, S. (2016). Robust accounting of international transfers under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement – Preliminary Findings Discussion Paper. Umweltbundesamt.

- Schneider, L., Duan, M., Stavins, R., Kizzier, K., Broekhoff, D., Jotzo, F., Winkler, H., Lazarus, M., Howard, A., & Hood, C. (2019). Double counting and the Paris Agreement rulebook. Science, 366(6462), 180–183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay8750

- Schneider, L., Füssler, J., Kohli, A., Graichen, J., Healy, S., Broekhoff, D. (2017). Discussion paper: Robust accounting of international transfers under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, p. 69. https://www.dehst.de/SharedDocs/downloads/EN/project-mechanisms/discussion-papers/Differences_and_commonalities_paris_agreement2.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4

- Schneider, L., Füssler, J., La Hoz Theuer, S., Kohli, A., Graichen, J., Healy, S., Broekhoff, D. (2017). Environmental Integrity under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement Discussion Paper. German Emissions Trading Authority (DEHSt).

- Schneider, L., Healy, S., Fallasch, F., de Leon, F., Rambharos, M., Schallert, B., Holler, J., Kizzier, K., Petsonk, A., Hanafi, A. (2020). What makes a high-quality carbon credit? https://www.oeko.de/fileadmin/oekodoc/What-makes-a-high-quality-carbon-credit.pdf

- Schneider, L., & La Hoz Theuer, S. (2018). Environmental integrity of international carbon market mechanisms under the Paris Agreement. Climate Policy, 19(3), 386–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1521332

- Schneider, L., La Hoz Theuer, S., Howard, A., Kizzier, K., & Cames, M. (2020). Outside in? Using international carbon markets for mitigation not covered by nationally determined contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement. Climate Policy, 20(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1674628

- Spalding-Fecher, R. (2017). Article 6.4 crediting outside of NDC commitments under the Paris Agreement: issues and options. 17.

- Streck, C. (2021). How voluntary carbon markets can drive climate ambition. Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law, 1–8. Retrieved February 22, 2021, from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02646811.2021.1881275

- Tong, D., & Trout, K. (2020). Big oil reality check – assessing oil and gas company climate plans. Oil Change International. Retrieved October 1, 2020, from http://priceofoil.org/content/uploads/2020/09/OCI-Big-Oil-Reality-Check-vF.pdf

- Trove Research. (2021). VCM and Article 6 interaction: Discussion paper on the use of corresponding adjustments for voluntary carbon credit transfers. Retrieved February 18, 2021, from https://globalcarbonoffsets.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/VCM-and-Article-6-interaction-6-Jan-2021-1.pdf

- TSVCM. (2020). Consultation document. Taskforce on scaling voluntary carbon markets. Retrieved February 10, 2021, from https://www.iif.com/Portals/1/Files/TSVCM_Consultation_Document.pdf

- TSVCM. (2021). Final report. Taskforce on scaling voluntary carbon markets. Retrieved February 4, 2021, from https://www.iif.com/Portals/1/Files/TSVCM_Report.pdf

- UN Data. (2020). GDP by type of expenditure at current prices – US dollars. Retrieved May 5, 2020, from http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=SNAAMA&f=grID%3a101%3bcurrID%3aUSD%3bpcFlag%3a0

- UNEP Finance Initiative. (2020). The portfolio decarbonization coalition. Retrieved April 9, 2020, from https://unepfi.org/pdc/

- UNFCCC. (2016). Paris Agreement, Retrieved March 3, 2016, from http://unfccc.int/files/meetings/paris_nov_2015/application/pdf/paris_agreement_english_.pdf

- UNFCCC. (2016, January 29). Report of the conference of the Parties on its twenty-first session, held in Paris from 30 November to 13 December 2015, Addendum, Part two: Action taken by the Conference of the Parties at its twenty-first session, FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1. UNFCCC; 2016. Report No.: FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1.

- UNFCCC. (2020). NAZCA platform. Retrieved April 9, 2020, from http://climateaction.unfccc.int/

- VCM-WG. (2019a). Consulation feedback. https://www.goldstandard.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019_07_envisioning_statement_consultation_tracker.xlsx

- VCM-WG. (2019b). Envisioning the role of the voluntary carbon market post 2020 – Webinar. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xPqe_m86Sjc&feature=youtu.be

- VCM-WG. (2019c). Envisioning the voluntary carbon market post-2020 – a working group statement for consultation on the future role and design of the voluntary carbon market to support the goals of the Paris Agreement. Retrieved March 18, 2020, from https://www.goldstandard.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019_06_envisioning_the_vcm_statement_consultation_0.pdf

- VCM-WG. (2019d). Envisioning the voluntary carbon market post-2020 (updated). Retrieved March 23, 2020, from https://www.goldstandard.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019_10_envisioning_vcm_statement_phase_1.pdf