ABSTRACT

Climate change has compounding effects on development, including direct and indirect impacts on food systems and human health. In the Pacific Islands region, the incidence of non-communicable diseases is among the highest in the world. Additionally, in policy documents, climate change features prominently among the issues most responsible for hindering development in the Pacific. Global discussions are now shifting towards a greater understanding and emphasis on the links between climate change, food systems, nutrition, health, and development. While these links are increasingly appreciated in research and practice, there is a need to understand which types of policy frameworks are best suited to address these issues in an integrated manner. This study was conducted by analyzing policy alignment and coherence in national level strategic planning instruments (policies, plans, and strategies) for two countries in the Pacific Islands region: Fiji and Vanuatu. Documents in the policy domains of development, agriculture, nutrition, health, and climate change were assessed to identify evidence of vertical (national to local), horizontal (between sectors), and integration across different thematic policy approaches (e.g. between economic development sustainable development approaches). By deconstructing the aims of different planning approaches and documents, and by mapping the relationships among them, it is possible to identify opportunities and gaps in the policy architecture that could be addressed in future planning cycles. The study identifies that policy alignment and coherence need to be explicitly addressed in the policy and planning design stage and included in monitoring and evaluation frameworks. The study also highlights the lag in the design and implementation of comprehensive food and nutrition security strategies in both countries and these lags can be linked to policy solutions for agriculture, health, and climate change.

Key policy insights

There is a need to explicitly consider policy alignment in the design stages of the policy cycle and set policy coherence as an explicit outcome to also be included in monitoring and evaluation frameworks.

A lack of consideration of vertical, horizontal, and approach integration in planning and policy processes can lead to failures in the implementation of climate policy, thus delaying countries’ efforts towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Pacific Island countries have an opportunity to work towards use of policy frameworks that are able to provide comprehensive responses to the compounding effects of climate change on food systems, diets, health, and, more broadly, on development.

1. Introduction

Dietary risk factors and malnutrition in all its forms are among the highest contributors to non-communicable disease (NCD) mortality around the world (Afshin et al. Citation2019). Further, anthropogenic climate change is directly implicated in the reduction of agricultural productivity globally, hindering development and progress towards eradicating poverty and hunger (Ortiz-Bobea et al. Citation2021). In addition, the stability of the global food supply is expected to be affected by the disruption of food chains, caused by an increase in the magnitude and frequency of extreme events (IPCC Citation2019). Recent research has renewed interest in food systems and how they can be utilized as entry-points for solving some of the most pressing global concerns impacting human and environmental health (Fanzo, Hood, and Davis Citation2020; Lang and Mason Citation2018).

The Pacific Islands region is an area where climate change and food insecurity are pressing concerns, and where there is also an urgent need for integrative approaches to address food insecurity, health, diets, and climate change challenges (Medina Hidalgo et al. Citation2020; Savage, McIver, and Schubert Citation2020b). Emerging approaches recognize the importance of an enhanced understanding of the interventions needed for food systems to effectively support human health and environmental outcomes (Da Silva Citation2019; Seekell et al. Citation2017; Swinburn et al. Citation2019). Previous studies conducted in Fiji and Vanuatu highlight the lack of a systematic approach to address the connections between food systems and climate change and in policy (Savage, Huber, and Bambrick Citation2020a; Savage et al. Citation2020c; Shah, Moroca, and Bhat Citation2018).

A key requirement to facilitate required food system transformations is assessing the degree to which existing policy frameworks provide a coherent and aligned response, as well as determining the optimal policy architecture that can accommodate such complex and interconnected issues (Lang and Mason Citation2018; Leach et al. Citation2020). One of the most highlighted failures of current policies and institutions dealing with complex issues such as climate change is that governance systems are usually fragmented and operate in silos (Golcher and Visseren-Hamakers Citation2018; Oseland Citation2019). This has also been acknowledged at international level discussions, particularly within the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which has been advocating for policy coherence in assessments of development interventions for over 20 years (OECD Citation2001).

The climate policy integration literature focuses on understanding the degree to which climate change objectives are integrated with other policy domains and across government levels to: avoid incongruities in policy objectives, reduce institutional inefficiencies, and to ensure optimal alignment of climate policies and sustainability goals in the context of high competition for limited resources and priorities (Plank et al. Citation2021). As countries continue to work towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), issues of policy integration are starting to resurface (Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, Dahl, and Persson Citation2018). Yet, the literature on climate policy integration highlights the lack of standardized methods to assess policy alignment and coherence between multiple policy domains (Medina Hidalgo, Nunn, and Beazley Citation2021a).

The aim of this study is to draw insights from research into both climate policy integration and policy coherence (Adelle and Russel Citation2013; Candel and Biesbroek Citation2016; Nilsson et al. Citation2012), to assess the policy arrangements that currently exist in support of integrative approaches to development, climate change adaptation, agriculture, nutrition, and health in the Pacific Island nations of Fiji and Vanuatu. The analysis focuses on assessing the consistency of multiple policy objectives and specific measures expressed through national and sectoral level strategic planning documents across a range of different policy domains. In addition, the study aims to assess policy coherence within climate adaptation documents (internal coherence) and across climate adaptation and development documents (coherence among policy domains).

1.1. Analytical framework

The framework used to analyse the multiple documents is comprised of two main components: policy coherence (internally and across domains) and policy alignment (across domains). The following section explains how coherence and alignment are conceptualized and assessed in this study.

Internal coherence is assessed in this study by identifying the approaches to climate change adaptation being promoted in each document (in the goals and vision statements) and determining if they are consistent with the types of adaptation policies, measures, and specific actions being proposed in the same document. Approaches to adaptation can be understood as the way in which climate adaptation is framed, hence influencing how adaptation strategies are designed and managed (McEvoy, Fünfgeld, and Bosomworth Citation2013; Medina Hidalgo et al. Citation2021c). Examples of approaches to adaptation frequently utilized in climate adaptation planning in the Pacific are ecosystems-based adaptation, community-based adaptation, and disaster risk reduction or resilience frameworks (Medina Hidalgo et al. Citation2021c). The typology developed by Biagini et al. (Citation2014) is utilized to classify adaptation actions. This typology classifies adaptation actions into ten types of actions depending on the nature of change or action they target (refer to Supplementary material 1 for examples of each type of action).

To assess coherence of policies among multiple policy domains, the framework proposed by Widmer (Citation2018) is utilized. This framework uses the level and approach to climate change adaptation mainstreaming to define integration or coherence between climate change and other policy domains. This is achieved by identifying levels of integration and approaches to integration present in policy and planning instruments. In addition, climate integration actions were classified into vertical, horizonal, and approach integration according to the definitions provided by Adelle and Russel (Citation2013) and Di Gregorio et al. (Citation2017). presents the key definitions of the concepts used to assess and classify policy integration.

Table 1. Definitions of policy integration concepts used in the analysis.

Policy alignment was identified by searching for explicit reference of climate change related policy mandates and goals for the implementation of measures across six policy domains: agriculture (including livestock and fisheries), nutrition, disaster risk reduction, national development, and health. This approach has previously been used to assess the alignment of climate policies in other studies (Antwi-Agyei et al. Citation2018; Hsu, Weinfurter, and Xu Citation2017). Policies from the disaster risk reduction domain were also included because these are closely linked to climate change adaptation in several countries, particularly in the Pacific Islands region, which have signed the Sendai Framework (Kelman Citation2015; Nalau et al. Citation2016). Comprehensive definitions of the concepts used in the analytical framework, the different approaches to adaptation, as well as examples from the coded text are presented in detail in Supplementary material 1.

2. Methods

2.1. Study area

The study is conducted by analyzing national level strategic planning instruments (policies, plans, and strategies) for Fiji and Vanuatu. Both nations are part of the sub-region known as Melanesia and are in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. In Vanuatu, approximately 39% of the working population 15 years and older are employed in the agriculture, forestry, and fishing industry (Vanuatu National Statistics Office Citation2020). In Fiji, approximately 29% of the employed population works in the agriculture sector (including commercial and subsistence-based activities) (Fiji Bureau of Statistics Citation2021). There is evidence that both countries are undergoing profound livelihood transformations due to climate change (Jackson, McNamara, and Witt Citation2017; Medina Hidalgo, Nunn, and Beazley Citation2021b). Additionally, in both, national health indicators related to the prevalence of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) have become a growing development and health concern (Savage et al. Citation2020b). Fiji and Vanuatu were selected for this study because they are representative of the challenges associated with climate change, food, and health in the Pacific Islands region. They are high-island nations, where agriculture is still practiced across most of the populated islands. These two countries also present the opportunity to contrast results in countries with a different development status. According to the World Bank’s country classifications by income level, Fiji is classified as upper-middle income, while Vanuatu is considered to have a lower-middle income economy (The World Bank Citation2020).

2.2. Data and analysis

The documents analyzed in this study refer to the various policy domains dealing with climate change adaptation in health, agriculture, and nutrition. In addition, national development plans were included in the analysis to identify the alignment and coherence between development goals, climate change adaptation targets, and particular sectoral goals. The planning instruments were sourced from the relevant websites of the sectoral ministries in each country. When documents (or the latest versions of documents) were not available through the websites, government officials in both countries were contacted to provide these. A final list of all documents included in the study was also corroborated with country officers to verify that these documents represent all that correspond to the studied policy domains at the national level. All documents included in the analysis are listed and summarized in Supplementary material 2.

Content analysis was conducted using a deductive thematic analysis approach. The process followed the six standard phases of thematic analysis: data familiarization, generation of codes or coding structure, development of themes, revision of themes, definition of themes, and report production (Clarke and Braun Citation2017; Nowell et al. Citation2017). Each document was read and coded using a predetermined coding structure. For Fiji, two development planning instruments (5-year & 20-year National Development Plan and Green Growth Framework) and the National Adaptation Plan (NAP) were used to assess coherence between development and climate goals/actions being prioritized for food systems, health, and nutrition. In the case of Vanuatu, the National Sustainable Development Plan (NSDP) and the National Adaptation Programme for Action (NAPA) were used for the analysis. The actions, goals, and policy objectives that refer to aspects of health, agriculture (including fisheries, livestock, and forestry), and food security were extracted from the documents and categorized to isolate the different priorities. Strategic planning documents from each policy domain were screened to identify explicit mentions of alignment with all other documents. These connections were then mapped to show how the different planning instruments connect to each other and those that lead the determination of priorities.

3. Results

The results are presented first by showing findings related to policy alignment for each country (3.1) and then by a synthesis of the approaches to climate change adaptation across the multiple policy dimensions studied here (3.2). The last section here focuses on characterizing how climate policy integration is characterized in strategic planning documents.

3.1. Policy alignment

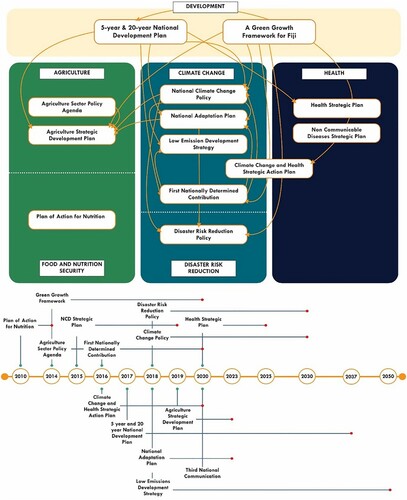

3.1.1. Policy mapping and timeline in Fiji

shows the mapping exercise for the different policies in Fiji. It shows how the Agriculture Strategic Development Plan (Ministry of Agriculture Citation2019) has the most explicit alignment to other existing planning instruments, particularly those from the climate change and development domains. The Green Growth Framework for Fiji (Republic of Fiji Citation2014) is also shown to be instrumental in guiding the design of many other planning documents, including the current National Development Plan (Republic of Fiji Citation2017).

This alignment demonstrates that the policy architecture in Fiji is based on mandates that primarily emerge from the national development planning domain. Both development plans in Fiji have prioritized actions relevant to nutrition, health, agriculture, and climate change. Only two documents did not contain explicit mention or connection to other policies and plans: the Plan of Action for Nutrition and the Non-Communicable Diseases Strategic Plan (Ministry of Health Citation2010, Citation2014). In the case of the Plan of Action for Nutrition, this can be explained by the fact that the document predates all other plans. Nevertheless, the Green Growth Framework (Republic of Fiji Citation2014) explicitly highlights the fact that Fiji does not yet possess an overarching national policy on food security that effectively integrates agriculture, fisheries, biosecurity, health, nutrition, and education.

The timeline of the documents analyzed date from 2010 to 2050. provides an overview of the overlapping timeframes included in the different planning instruments. Most climate change planning documents were developed in 2018, which could be explained as a response emanating from Fiji’s proactive response to the ratification of the Paris Agreement. The Climate Change and Health Strategic Action Plan from the Health Ministry predates most of the major climate change documents (Ministry of Health Citation2016a). The timeline also shows that the Green Growth Framework precedes most of the other planning documents, explaining its use for generating the mandates and establishing the priorities for most of the other sectoral planning instruments (Republic of Fiji Citation2014).

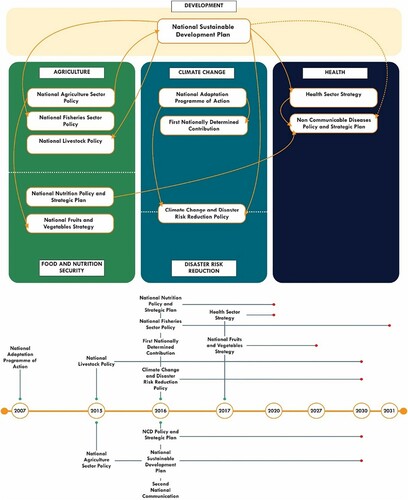

3.1.2. Policy mapping and timeline in Vanuatu

In Vanuatu, the main development planning instrument is the National Sustainable Development Plan (NSDP) (Republic of Vanuatu Citation2016). As shown in , this plan was directly influenced by goals already set out in the National Agriculture Sector Policy (Ministry of Agriculture Citation2015). The dotted line connecting the NSDP and the NCD Policy and Strategic Plan represents the finding that these plans are not explicitly connected, despite the NCD Policy stating that outcomes from the NSDP should be included in it once made official (Ministry of Health Citation2016b; Republic of Vanuatu Citation2016). This is explained by the fact that the NCD Policy was released before the NSDP was officially released and ratified, a situation which exemplifies the challenges of aligning timeframes in the planning cycles of multiple policy domains. In the case of Vanuatu, there are explicit connections and alignments between agriculture, food security, and health planning documents. Yet, there are no explicit connections between health and climate change planning documents and vice versa. Climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction approaches are integrated in a single planning instrument, which combines mandates directed by the NSDP and the NAPA (Republic of Vanuatu Citation2007, Citation2016).

The timeline of the documents analyzed extends from 2007 to 2031. shows most planning documents for Vanuatu were developed in 2016, covering mid-term and long-term timeframes. The timeline also shows that the NAPA precedes most of the other planning documents, but was not developed to be a strategic planning document and therefore did not specify explicit timeframes for the completion of the activities (Republic of Vanuatu Citation2007).

3.2. Policy coherence

3.2.1. Approaches to adaptation

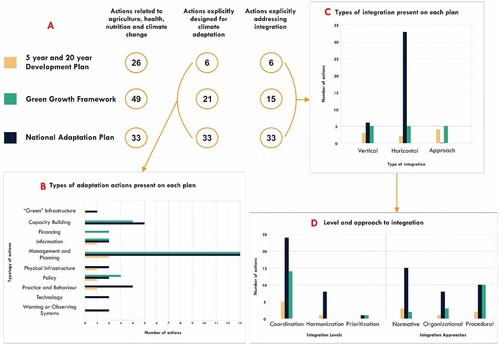

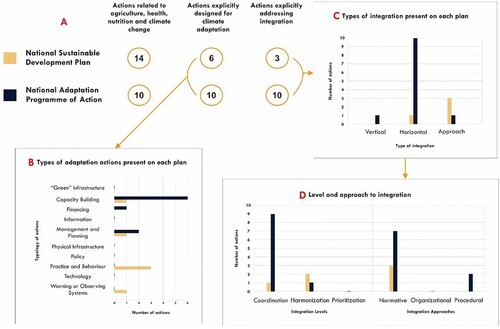

The three national development strategic planning documents analyzed for Fiji and Vanuatu recognize and emphasize climate hazards – such as tropical cyclones, storm surges, and increases in temperature and rainfall variability attributable to climate change – as key events to drive policy. All three plans identify climate change as an issue of strategic national priority. The National Development Plan in Fiji articulates specific climate change related policies within the plan’s goals: ‘access to quality health facilities necessary to good health and to health care services, including reproductive health care’ (Republic of Fiji Citation2017, 40) and ‘promoting equal opportunities, access to basic services and building resilient communities’ (Republic of Fiji Citation2017, 103). In the case of the Green Growth Framework in Fiji, climate change is considered within the thematic policy areas of ‘building resilience to climate change and disaster’ (Republic of Fiji Citation2014, 29) and ‘food security’ (Republic of Fiji Citation2014, 62) detailing six concrete climate related actions (A). For Vanuatu, the NSDP addresses climate change in the thematic areas of ‘food and nutrition security’ (Republic of Vanuatu Citation2016, 13) and ‘climate and disaster resilience’ (Republic of Vanuatu Citation2016, 14), also containing six climate adaptation actions (A).

Figure 3. Analysis of climate integration actions in Fiji: section A presents the 3 documents assessed for coherence across domains with the numbers of actions identified in each document that address either adaptation, integration explicitly or inter-sectoral goals. In sections B, C and D the colours of the bars represent each of the documents as presented in section A. Sections C and D present the results for the characterization of climate change integration.

Figure 4. Analysis of climate integration actions in Vanuatu: section A presents the 2 documents assessed for coherence across domains with the numbers of actions identified in each document that address either adaptation, integration explicitly or inter-sectoral goals. In sections B, C and D the colours of the bars represent each of the documents as presented in section A. Sections C and D present the results for the characterization of climate change integration.

In all the sectoral planning documents analyzed for both countries, the main motivation to address climate change appears to be a recognition of the potential of climate change to hinder the achievement of development goals. A second explicit motivation and mandate to address global climate change, which is evident mostly in the stand-alone national adaptation plans and policies, is the need to comply with international level agreements under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The planning documents of Fiji and Vanuatu highlight the importance of utilizing ecosystem-based and community-based approaches to climate change adaptation. In the case of Fiji, adaptation is also framed as synonymous with ‘climate-resilient development’. In Fiji’s Climate Change Policy and NAP, the concept of resilience is presented as a central approach to deal with climate change (Government of the Republic of Fiji Citation2018; Republic of Fiji Citation2018). In addition, the NAP highlights the need to integrate gender and human rights approaches into adaptation planning. In Vanuatu, there is greater emphasis placed on integrated climate change and disaster risk reduction approaches and the associated need to develop and apply loss and damage accounting and financial mechanisms.

3.2.2. Coherence between development and climate change adaptation goals for agriculture, health, and nutrition in Fiji

All of Fiji’s national development and adaptation planning documents identify health, nutrition, and agriculture as priority areas for action. Fiji’s NAP contains 160 adaptation measures in total, with 33 of these measures addressing adaptation in these three sectors (A) (Government of the Republic of Fiji Citation2018). As shown in B, most actions prioritized are management and planning types of activities, followed by capacity building (Government of the Republic of Fiji Citation2018; Republic of Fiji Citation2014, Citation2017).

Most proposed actions aspire to integrate a response to climate change in the form of coordination between sectoral or national development objectives and climate change adaptation objectives. The prioritization of climate change adaptation is pursued only in one measure from the Green Growth Framework and one from the NAP (D) (Government of the Republic of Fiji Citation2018; Republic of Fiji Citation2014). Furthermore, the integration approach most commonly used in the National Development Plan and the NAP is a normative approach (50% and 45% of integration actions, respectively) in contrast to the Green Growth Framework in which the procedural approach is more prominent, accounting for 67% of climate integration measures (Government of the Republic of Fiji Citation2018; Republic of Fiji Citation2014, Citation2017).

The NAP in Fiji also outlines a series of measures which are not linked to specific sectors and are referred to in the plan as ‘system components’ (Government of the Republic of Fiji Citation2018). Horizontal and vertical integration are included in these system components and associated with a total of 21 concrete actions. There are 11 actions focusing on horizontal integration and 10 on vertical integration in addition to the actions presented in C. As shown in D, most integration actions seek coordination (81%), followed by harmonization (14%) and prioritization (5%). In terms of approaches to integration, the procedural approach accounts for 48% of actions, followed by the normative and organizational approaches (38% and 14%, respectively).

3.2.3. Coherence between development and climate change adaptation goals for agriculture, health, and nutrition in Vanuatu

In the case of Vanuatu, agriculture, health, nutrition, and climate change actions are present in both the NSDP and the NAPA, with 14 and 10 concrete actions, respectively (A) (Republic of Vanuatu Citation2007, Citation2016). Of the actions that focus on climate change adaptation for the agriculture, nutrition, and health sectors, most are centred on capacity building, followed by practice and behaviour approaches (B). The most prominent type of integration presented in the NAP is horizontal (C). Integration of climate change adaptation in Vanuatu is primarily conducted through coordination between sectoral and development priorities (D). In addition, most integration actions follow the normative approach, with only two actions using procedural and none using organizational (D).

3.2.4. Typology and prioritization of adaptation actions promoted in sectoral planning documents in Fiji

Climate change adaptation is integrated through specific actions in Fiji’s sectoral planning instruments for agriculture and health. In the case of the agricultural sector, actions focus on the introduction or promotion of certain practices and behaviours, including conservation agriculture, agroforestry, soil and water management practices, and the diversification of farming systems. In addition, the agriculture sector documents highlight the need to establish management and planning actions that can inform evidence-based planning. These focus on the incorporation of research into the development of new crop and livestock varieties and breeds, and the formation of social safety nets and market mechanisms to help farmers cope with the effects of climate change.

In the case of the health sector, Fiji has developed the Climate Change and Health Strategic Action Plan; climate change is also prioritized in the Health Strategic Plan (Ministry of Health Citation2016a, Citation2017). Actions promoted in these plans mostly focus on management, planning, and capacity building activities intended to increase the capacity of organizations and stakeholders from the health sector to incorporate climate change adaptation considerations into the services they provide. Other types of activities include the development of monitoring and early warning systems for climate related diseases, the development and implementation of new technologies, and securing financial support from domestic and international sources to enable the implementation of desired activities.

3.2.5. Typology and prioritization of adaptation actions promoted in sectoral planning documents in Vanuatu

In Vanuatu, sectoral planning documents from both agriculture and health also incorporate climate change adaptation activities. Agriculture sector documents stress the need to integrate both climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction in all initiatives aimed at supporting agriculture and rural development, promoted by both the government and development agencies. Other activities include capacity building to increase farmers’ ability to cope with extreme weather events, as well as the development of research activities to further understand climate impacts and risks for fisheries resources. The two health sector planning documents address climate change by suggesting coordination with other ministries and operationalizing a task force to assess the potential health impacts of climate change and the actions thereby required to be incorporated into health programme development (Ministry of Health Citation2016b, Citation2017).

4. Discussion

In the national level development documents analyzed, development goals are given top priority, whereas climate change adaptation is viewed as necessary to ensure that progress in achieving these goals is not hindered by climate impacts. In Fiji, there is clear policy alignment between agriculture and climate domains and health and climate domains. Yet, there is no explicit alignment of plans between agriculture, health, and nutrition domains. In Vanuatu, there is a clearer alignment among policies and plans from the agriculture, health, and nutrition domains. Additionally, in Vanuatu, the National Agriculture Sector Policy, which preceded the NDSP, has put strong emphasis on the contribution of agriculture to the attainment of SDGs (Ministry of Agriculture Citation2015; Republic of Vanuatu Citation2016). In both countries, NCDs planning instruments are not directly aligned to the agricultural, climate, or development planning instruments, which shows a clear opportunity for higher levels of integration of policy goals for the management and prevention of NCDs into these other related policy arenas.

For both countries, climate change adaptation is explicitly addressed in agriculture and health sectoral plans, but not in nutrition plans. Yet links between agriculture, food, and nutrition security as well as health are explicit within national level plans. This highlights an opportunity to achieve a more consistent alignment between development, climate, agriculture, nutrition, and health objectives across sectors and governance levels.

Differences in time horizons and timing of the policy cycles across different sectors can affect the degree to which goals from multiple policy domains are aligned and integrated (Saito Citation2013; Singh-Peterson et al. Citation2013). In both Fiji and Vanuatu, strategic planning has not advanced at the same pace in all sectors. In Fiji, this is most evident in nutrition and food security, for which the latest strategic planning document was produced in 2010. In Vanuatu, the largest planning gap lies within climate change adaptation, with the latest actionable plan developed in 2007. In addition, planning instruments from the climate and health sectors are not explicitly integrated with each other. While Vanuatu developed its Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction Policy in 2016, this document sets out only general priorities and, in fact, mandates the creation of a National Adaptation Plan to replace and update measures prioritized by the NAPA of 2007 (Government of the Republic of Vanuatu Citation2015; Republic of Vanuatu Citation2007).

The agreed development of the NAPA in Vanuatu was prompted by the LDCs’ work programme agreed in 2001 under the UNFCCC. Under the programme, LDCs were encouraged to present NAPAs to the UNFCCC to identify their most urgent and immediate adaptation needs (UNFCCC Citation2020). Research conducted about this NAPA process in other LDCs shows that NAPAs were primarily driven by external funders and mandates, which resulted in a largely short-term and disconnected approach to climate change adaptation planning (Gwimbi Citation2017; Nagoda Citation2015). In the case of the NAPA in Vanuatu, the processes produced a set of isolated projects and actions instead of a comprehensive plan or strategy which integrated all sectoral and national needs and priorities, a contrast to the case of the NAP for Fiji.

In the climate change planning documents of both Vanuatu and Fiji, ecosystem-based approaches (EBAs) and community-based approaches (CBAs) to adaptation feature prominently. These are common approaches prioritized in many other developing country contexts (Piggott-McKellar et al. Citation2019; Wamsler et al. Citation2016). In addition to these approaches, Fiji also prioritizes a resilience building approach, while Vanuatu centres more on melding climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction approaches. Yet, there is no evidence in the climate change plans of concrete measures that would support approaches like EBAs or CBAs, which suggests a lack of internal coherence between the approaches and measures prioritized.

In both countries, the integration of climate change adaptation is done primarily by means of coordination. Widmer (Citation2018) refers to this level of integration as a form of weak integration. This is because it implies that planning instruments keep sectoral and national goals and priorities unchanged, and that a desire for integration is mostly to avoid contradictions and facilitate synergies. Only a few activities within the studied documents show strong integration by prioritizing climate change goals or placing them on equal terms with other objectives (Widmer Citation2018). Additionally, in both countries, climate change is integrated across policy domains using a predominantly normative approach. This normative approach focuses on either the development of new climate change strategies or the provision of mandates to deal with climate change within existing legislation and planning documents (Somorin et al. Citation2016; Wejs Citation2014). While normative approaches are necessary to set priorities, organizational and procedural approaches are required to guarantee that policies and strategies are supported by the institutional structures and mechanisms that drive their implementation (Goepfert, Wamsler, and Lang Citation2019; Nemakonde and Van Niekerk Citation2017).

Conversely, organizations and procedures without clear mandates are unlikely to gain enough consistent political traction and resources to achieve the desired outcomes (Biesbroek and Candel Citation2020; Pilato, Sallu, and Gaworek-Michalczenia Citation2018). The results presented in this study highlight the need to better balance these three approaches – normative, organizational, and procedural – in future iterations of planning. Monitoring and evaluation frameworks for the plans already in place would also benefit from including assessments of which levels and approaches to integration were effective in facilitating implementation and coordination across governance levels.

Most of the research conducted in the climate policy integration arena has focused on the integration of climate change adaptation and development in general (Dany and Lebel Citation2020; Gwimbi Citation2017; Hardee and Mutunga Citation2010). This study is innovative in that it concentrates on assessing to what degree development, climate change, agriculture, nutrition, and health domains are all linked in policy and planning. At the local level, communities in the Pacific Islands region favour approaches centred on livelihoods, integrating those domains (Medina Hidalgo et al. Citation2021c; Piggott-McKellar, McNamara, and Nunn Citation2020; Westoby et al. Citation2020). It therefore makes sense that future policies should be designed in a way that not only promotes these integrated approaches, but puts in place the organizational and procedural structures that can facilitate coordination and cooperation among stakeholders. This is a key step to secure implementation of integrated policies and to better support local communities in their efforts to adapt to a shifting environmental regime (Nunn Citation2009).

As has been argued by others, the achievement of climate policy outcomes is not necessarily only achieved by mainstreaming climate change objectives into other policy domains (Candel and Biesbroek Citation2016). Stand-alone climate planning documents can effectively and consistently address the issues, even if some (dis)integration is required for necessary climate governance systems to operate (Biesbroek and Candel Citation2020; Candel and Biesbroek Citation2016; Uppanunchai, Chitmanat, and Lebel Citation2018). In Fiji, the NAP partially serves that purpose by outlining vertical and horizontal integration objectives. Yet, in the section of the NAP addressing integration, emphasis is placed on procedural approaches. In addition, proposed measures have a generic nature and do not provide clear mandates to specific sectors nor to governance levels, which could hinder implementation.

4.1. Opportunities for future research

Research on policy integration across climate, food, diet, and health policy domains is an area of opportunity for all countries beyond the Pacific Islands region, as they embark on the task of achieving global targets such as the SDGs (Koff, Challenger, and Portillo Citation2020). Climate change has direct impacts on food systems, health, and nutrition; additionally, solutions to the prevalence of NCDs in the Pacific can be fully addressed only by coordinating actions in the health, nutrition, and agriculture sectors. Determining what has already been achieved by existing policy frameworks and how to improve the process remains a key contribution towards supporting Pacific Island countries in their efforts to achieve food and nutrition security in the face of climate change.

This study does not assess the level of implementation of the planning documents nor the enabling conditions and barriers to achieving the stated goals. Future research in this area should aim to provide greater understanding about those elements that need to be modified at the design stage of the process to enable more explicit and actionable links between food systems, nutrition, and health. Of special interest would be an analysis of which organizational structures and mechanisms for cooperation and coordination end up being established because of the integration measures contained in the plans and their role in achieving the goals. Recent research in rural Vanuatu showed a widespread ignorance of national sustainability policy, yet an extraordinary alignment with traditional (kastom) practices, showing an opportunity for a future engagement of culture by policy in the sustainability area (Rantes, Nunn, and Addinsall Citation2022).

Identifying and documenting best practices in implementation would improve the efficiency and efficacy of strategic planning to address challenges emerging from overlapping impacts on food systems, nutrition, and health. This is an exercise that could be usefully developed for other Pacific Island countries, as this study reveals that despite some similarities in the nature and importance of the problems, the policy architecture in Fiji and Vanuatu is very dissimilar. Therefore, the policy gaps and opportunities are also likely to be diverse for each country in the Pacific Islands region.

5. Conclusions and policy recommendations

The findings of this study confirm the need to improve planning processes so that policy coherence and alignment are explicitly factored in as outcomes during the design stage of the policy cycle, becoming part of the monitoring and evaluation frameworks. In both Fiji and Vanuatu, external cooperation agencies have provided financial and technical support for development of most of the planning instruments studied. As financial and technical aid continues to support these planning processes, an opportunity arises to assist and facilitate them to further support strategic planning for nutrition in a way that explicitly and effectively connects interventions to development, climate change adaptation, agriculture, and health goals. Future iterations of policy and planning cycles in the studied domains should place greater focus on achieving coherence across different policy domains and internal coherence within each planning document. This means the vision and implementation of planned measures should match the level of change and transformation required for a more integrated way of addressing climate change across levels of governance (vertical governance) and across sectors (horizontal governance).

While conceptually the relationships between food systems, climate change, diets, and health are becoming more prominent in research, there is still a latent opportunity in policy frameworks to make these links more explicit, to coordinate and drive more coherent actions across these different policy arenas. The largest gaps in alignment in this study were found between the NCD and nutrition domains and all the other domains, including climate policy. By deconstructing the aims of different planning documents across different policy arenas – and mapping relationships among them – this study identifies opportunities and gaps in the policy architecture that can be addressed in coming planning cycles. The study concludes that it is important to verify that the types of measures proposed match or are fully consistent with the climate change adaptation approaches, which the plans purportedly promote. In addition, some sectoral and development plans frame climate change as a priority issue, yet integration is primarily proposed by means of coordination. To achieve more transformative climate adaptation measures, prioritization and further harmonization need to occur. Furthermore, normative approaches need to be better balanced with organizational and procedural approaches to facilitate implementation of climate actions across multiple domains and levels of governance. Addressing the alignment and coherence gaps identified in this study has the potential to support the achievement of multiple SDGs and to limit the lag in planning and policy development for the food and nutrition security domain.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (158.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adelle, C., & Russel, D. (2013). Climate policy integration: A case of déjà Vu? Environmental Policy and Governance, 23(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1601

- Afshin, A., Sur, P. J., Fay, K. A., Cornaby, L., Ferrara, G., Salama, J. S., Mullany, E. C., Abate, K. H., Abbafati, C., Abebe, Z., Afarideh, M., Aggarwal, A., Agrawal, S., Akinyemiju, T., Alahdab, F., Bacha, U., Bachman, V. F., Badali, H., Badawi, A., … Murray, C. J. L. (2019). Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. The Lancet, 393(10184), 1958–1972. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8

- Antwi-Agyei, P., Dougill, A. J., Agyekum, T. P., & Stringer, L. C. (2018). Alignment between nationally determined contributions and the sustainable development goals for West Africa. Climate Policy, 18(10), 1296–1312. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1431199

- Biagini, B., Bierbaum, R., Stults, M., Dobardzic, S., & McNeeley, S. M. (2014). A typology of adaptation actions: A global look at climate adaptation actions financed through the global environment facility. Global Environmental Change, 25, 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.01.003

- Biesbroek, R., & Candel, J. J. L. (2020). Mechanisms for policy (dis)integration: Explaining food policy and climate change adaptation policy in the Netherlands. Policy Sciences, 53(1), 61–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-019-09354-2

- Candel, J. J. L., & Biesbroek, R. (2016). Toward a processual understanding of policy integration. Policy Sciences, 49(3), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-016-9248-y

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

- Dany, V., & Lebel, L. (2020). Integrating concerns with climate change into local development planning in Cambodia. Review of Policy Research, 37(2), 221–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12367

- Da Silva, J. G. (2019). Transforming food systems for better health. The Lancet, 393(10173), e30–e31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33249-5

- Di Gregorio, M., Nurrochmat, D. R., Paavola, J., Sari, I. M., Fatorelli, L., Pramova, E., Locatelli, B., Brockhaus, M., & Kusumadewi, S. D. (2017). Climate policy integration in the land use sector: Mitigation, adaptation and sustainable development linkages. Environmental Science & Policy, 67, 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.11.004

- Fanzo, J., Hood, A., & Davis, C. (2020). Eating our way through the anthropocene. Physiology & Behavior, 222, 112929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.112929

- Fiji Bureau of Statistics. (2021). 2019-20 Household income and expenditure survey: main report https://www.statsfiji.gov.fj/images/documents/HIES_2019-20/2019-20_HIES_Main_Report.pdf.

- Goepfert, C., Wamsler, C., & Lang, W. (2019). A framework for the joint institutionalization of climate change mitigation and adaptation in city administrations. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 24(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-018-9789-9

- Golcher, C. S., & Visseren-Hamakers, I. J. (2018). Framing and integration in the global forest, agriculture and climate change nexus. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 36(8), 1415–1436. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654418788566

- Government of the Republic of Fiji. (2018). Republic of Fiji national adaptation plan: A pathway towards climate resilience. Government of the Republic of Fiji.

- Government of the Republic of Vanuatu. (2015). Vanuatu climate change and disaster risk reduction policy 2016-2030. Fiji Secretariat of the Pacific Community.

- Gwimbi, P. (2017). Mainstreaming national adaptation programmes of action into national development plans in lesotho. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 9(3), 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-11-2015-0164

- Hardee, K., & Mutunga, C. (2010). Strengthening the link between climate change adaptation and national development plans: Lessons from the case of population in National Adaptation programmes of action (NAPAs). Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 15(2), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-009-9208-3

- Hsu, A., Weinfurter, A., & Xu, K. (2017). Aligning subnational climate actions for the new post-Paris climate regime. Climatic Change, 142(3-4), 419–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-1957-5

- IPCC. (2019). Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate change and land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems (P. R. Shukla, J. Skea, E. Calvo Buendia, V. Masson-Delmotte, H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, P. Zhai, R. Slade, S. Connors, R. van Diemen, M. Ferrat, E. Haughey, S. Luz, S. Neogi, M. Pathak, J. Petzold, J. Portugal Pereira, P. Vyas, E. Huntley, K. Kissick, M. Belkacemi, & J. Malley Eds.).

- Jackson, G., McNamara, K., & Witt, B. (2017). A framework for disaster vulnerability in a small Island in the southwest pacific: A case study of emae Island, Vanuatu. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 8(4), 358–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-017-0145-6

- Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S., Dahl, A. L., & Persson, Å. (2018). The emerging accountability regimes for the Sustainable Development Goals and policy integration: Friend or foe? Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 36(8), 1371–1390. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654418779995

- Kelman, I. (2015). Climate change and the sendai framework for disaster risk reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 6(2), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-015-0046-5

- Koff, H., Challenger, A., & Portillo, I. (2020). Guidelines for operationalizing policy coherence for development (PCD) as a methodology for the design and implementation of sustainable development strategies. Sustainability, 12(10), 4055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104055

- Lang, T., & Mason, P. (2018). Sustainable diet policy development: Implications of multi-criteria and other approaches, 2008–2017. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 77(3), 331–346. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665117004074

- Leach, M., Nisbett, N., Cabral, L., Harris, J., Hossain, N., & Thompson, J. (2020). Food politics and development. World Development, 134, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105024

- McEvoy, D., Fünfgeld, H., & Bosomworth, K. (2013). Resilience and climate change adaptation: The importance of framing. Planning Practice and Research, 28(3), 280–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2013.787710

- Medina Hidalgo, D., Nunn, P. D., & Beazley, H. (2021a). Challenges and opportunities for food systems in a changing climate: A systematic review of climate policy integration. Environmental Science & Policy, 124, 485–495. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.07.017

- Medina Hidalgo, D., Nunn, P. D., & Beazley, H. (2021b). Uncovering multilayered vulnerability and resilience in rural villages in the pacific: A case study of Ono island, Fiji. Ecology and Society, 26(1), https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12197-260126

- Medina Hidalgo, D., Nunn, P. D., Beazley, H., Sovinasalevu, J. S., & Veitayaki, J. (2021c). Climate change adaptation planning in remote contexts: Insights from community-based natural resource management and rural development initiatives in the Pacific islands. Climate and Development, 909–921. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2020.1867046

- Medina Hidalgo, D., Witten, I., Nunn, P. D., Burkhart, S., Bogard, J. R., Beazley, H., & Herrero, M. (2020). Sustaining healthy diets in times of change: Linking climate hazards, food systems and nutrition security in rural communities of the Fiji islands. Regional Environmental Change, 20(3), 73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01653-2

- Ministry of Agriculture. (2015). Vanuatu agriculture sector policy. Vanuatu.

- Ministry of Agriculture. (2019). 5 year strategic development plan 2019-2023. Fiji.

- Ministry of Health. (2010). The Fiji plan of action for nutrition 2010-2014. Fiji.

- Ministry of Health. (2014). Non-communicable diseases strategic plan 2015-2019. Australian Aid.

- Ministry of Health. (2016a). Climate change and health strategic action plan 2016-2020. Fiji.

- Ministry of Health. (2016b). Vanuatu Non-communicable disease policy & strategic plan 2016-2020. Vanuatu.

- Ministry of Health. (2017). Health sector strategy 2017-2020. Vanuatu.

- Nagoda, S. (2015). New discourses but same old development approaches? Climate change adaptation policies, chronic food insecurity and development interventions in northwestern Nepal. Global Environmental Change, 35, 570–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.08.014

- Nalau, J., Handmer, J., Dalesa, M., Foster, H., Edwards, J., Kauhiona, H., Yates, L., & Welegtabit, S. (2016). The practice of integrating adaptation and disaster risk reduction in the south-west pacific. Climate and Development, 8(4), 365–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2015.1064809

- Nemakonde, L. D., & Van Niekerk, D. (2017). A normative model for integrating organisations for disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation within SADC member states. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, 26(3), 361–376. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-03-2017-0066

- Nilsson, M., Zamparutti, T., Petersen, J. E., Nykvist, B., Rudberg, P., & McGuinn, J. (2012). Understanding policy coherence: Analytical framework and examples of sector–environment policy interactions in the EU. Environmental Policy and Governance, 22(6), 395–423. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1589

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Nunn, P. (2009). Responding to the challenges of climate change in the Pacific Islands: Management and technological imperatives. Climate Research, 40(2/3), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.3354/cr00806

- OECD. . (2001). The DAC guidelines: poverty reduction: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- Ortiz-Bobea, A., Ault, T. R., Carrillo, C. M., Chambers, R. G., & Lobell, D. B. (2021). Anthropogenic climate change has slowed global agricultural productivity growth. Nature Climate Change, 11(4), 306–312. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01000-1

- Oseland, S. E. (2019). Breaking silos: Can cities break down institutional barriers in climate planning? Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(4), 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1623657

- Piggott-McKellar, A. E., McNamara, K. E., & Nunn, P. D. (2020). Who defines “good” climate change adaptation and why it matters: A case study from abaiang island, Kiribati. Regional Environmental Change, 20(2), 43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01614-9

- Piggott-McKellar, A. E., McNamara, K. E., Nunn, P. D., & Watson, J. E. (2019). What are the barriers to successful community-based climate change adaptation? A review of grey literature. Local Environment, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2019.1580688

- Pilato, G., Sallu, S. M., & Gaworek-Michalczenia, M. (2018). Assessing the integration of climate change and development strategies at local levels: Insights from muheza district, tanzania. Sustainability, 10(1), https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010174

- Plank, C., Haas, W., Schreuer, A., Irshaid, J., Barben, D., & Görg, C. (2021). Climate policy integration viewed through the stakeholders' eyes: A co-production of knowledge in social-ecological transformation research. Environmental Policy and Governance, https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1938

- Rantes, J., Nunn, P. D., & Addinsall, C. (2022). Sustainable development at the policy-practice nexus: Insights from south west Bay, malakula island, Vanuatu. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 46(2), 234–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2021.1979706

- Republic of Fiji. (2014). A Green Growth Framework for Fiji: Restoring the balance in development that is Sustainable for Our future. Ministry of Strategic Planning, National Development and Statistics.

- Republic of Fiji. (2017). 5-year & 20-year National Development Plan: Transforming Fiji. Ministry of Economy.

- Republic of Fiji. (2018). Republic of Fiji national climate change policy 2018-2030. Ministry of Economy.

- Republic of Vanuatu. (2007). National adaptation programme for action (NAPA). Vanuatu.

- Republic of Vanuatu. (2016). Vanuatu 2030: The people's plan, National Sustainable Development Plan 2016-2030. Department of Strategic Policy, Planning and Aid Cooperation.

- Saito, N. (2013). Mainstreaming climate change adaptation in least developed countries in south and Southeast Asia. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 18(6), 825–849. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-012-9392-4

- Savage, A., Huber, C., & Bambrick, H. (2020a). Integration of climate change adaptation, disaster risk reduction and development in Vanuatu: A systems perspective. In L. Briguglio, J. Byron, S. Moncada, & W. Veenendaal (Eds.), Handbook of governance in Small states (pp. 151–166). Routledge.

- Savage, A., McIver, L., & Schubert, L. (2020b). Review: The nexus of climate change, food and nutrition security and diet-related non-communicable diseases in Pacific Island countries and territories. Climate and Development, 12(2), 120–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2019.1605284

- Savage, A., Schubert, L., Huber, C., Bambrick, H., Hall, N., & Bellotti, B. (2020c). Adaptation to the climate crisis: Opportunities for food and nutrition security and health in a Pacific small island state. Weather, Climate, and Society, 12(4), 745–758. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-19-0090.1

- Seekell, D., Carr, J., Dell’Angelo, J., D’Odorico, P., Fader, M., Gephart, J., Kummu, M., Magliocca, N., Porkka, M., Puma, M., Ratajczak, Z., Rulli, M. C., Suweis, S., & Tavoni, A. (2017). Resilience in the global food system. Environmental Research Letters, 12(2), 025010. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa5730

- Shah, S., Moroca, A., & Bhat, J. A. (2018). Neo-traditional approaches for ensuring food security in Fiji islands. Environmental Development, 28, 83–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2018.11.001

- Singh-Peterson, L., Serrao-Neumann, S., Crick, F., & Sporne, I. (2013). Planning for climate change across borders: Insights from the gold coast (QLD) - tweed (NSW) region. Australian Planner, 50(2), 148–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.2013.776980

- Somorin, O. A., Visseren-Hamakers, I. J., Arts, B., Tiani, A.-M., & Sonwa, D. J. (2016). Integration through interaction? Synergy between adaptation and mitigation (REDD+) in cameroon. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 34(3), 415–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X16645341

- Swinburn, B. A., Kraak, V. I., Allender, S., Atkins, V. J., Baker, P. I., Bogard, J. R., Brinsden, H., Calvillo, A., De Schutter, O., & Devarajan, R. (2019). The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: The lancet commission report. The Lancet, 393(10173), 791–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32822-8

- The World Bank. (2020). World Bank country classifications by income level: 2020-2021. https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2020-2021.

- UNFCCC. (2020). National Adaptation Programmes of Action. https://unfccc.int/topics/resilience/workstreams/national-adaptation-programmes-of-action/introduction.

- Uppanunchai, A., Chitmanat, C., & Lebel, L. (2018). Mainstreaming climate change adaptation into inland aquaculture policies in Thailand. Climate Policy, 18(1), 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2016.1242055

- Vanuatu National Statistics Office. (2020). National population and housing census https://vnso.gov.vu/index.php/en/statistics-report/census-report/national-population-and-housing-census/province.

- Wamsler, C., Niven, L., Beery, T., Bramryd, T., Ekelund, N., Jönsson, K., Osmani, A., Palo, T., & Stålhammar, S. (2016). Operationalizing ecosystem-based adaptation: Harnessing ecosystem services to buffer communities against climate change. Ecology and Society, 21(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08266-210131

- Wejs, A. (2014). Integrating climate change into governance at the municipal scale: An institutional perspective on practices in Denmark. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 32(6), 1017–1035. https://doi.org/10.1068/c1215

- Westoby, R., McNamara, K. E., Kumar, R., & Nunn, P. D. (2020). From community-based to locally led adaptation: Evidence from Vanuatu. Ambio, 49(9), 1466–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01294-8

- Widmer, A. (2018). Mainstreaming climate adaptation in Switzerland: How the national adaptation strategy is implemented differently across sectors. Environmental Science & Policy, 82, 71–78. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2018.01.007