ABSTRACT

The study assesses the extent to which public health is integrated into European national and urban climate change adaptation policy and planning. We analyse national adaptation documents from the 27 European Union member states and interview city-level experts (n = 17) on the integration of three categories of adaptation efforts: general efforts to minimize health impacts related to climate change, targeted efforts to enhance resilience in health systems, and supportive efforts to foster the potential of the first two categories. At a national level, general efforts to address vector-borne diseases and heat-related illness are covered comprehensively, whereas efforts addressing several climate-related health risks are neglected (e.g. water-borne diseases, injuries from extreme weather and cardiopulmonary health) or overlooked (e.g. malnutrition and mental health). Targeted efforts to inform policy decisions, such as carrying out research, risk monitoring and assessments, are often described in detail, but efforts to manage day-to-day health care delivery and emergency situations receive little attention. At the urban level, health issues receive less attention in climate adaptation policy and planning. If health topics are included, they are often described as indirect benefits of adaptation efforts in other sectors and not perceived as the priority of the involved authorities. This effectively means that general and targeted efforts are the responsibility of other sectoral departments, while supportive efforts are the responsibility of the national government or external organizations. As a result, at an urban level, climate-related health system adaptation is not a policy aim in its own right, and many potentially high health risks are being ignored. In order for health risks to be better integrated into adaptation policy and planning, it is critical to interconnect national and urban levels, reduce sectoral thinking and welcome external expertize and facilitate large-scale data collection and sharing of health and climate indicators.

We recommend focussing on cooperatively drafting strategies for integrating health issues into climate policy and planning with stakeholders at the national and urban levels, in different policy sectors and in society.

Policy planners can build on the strengths of adaptation documents from other countries or cities and take note of any weaknesses.

We advocate to foster co-benefits for health and climate action of various adaptation measures (e.g. by promoting active mobility and urban greenery, health impacts related to heat, (mental and physical) stress and air pollution are reduced).

Large-scale data collection and sharing of health and climate indicators should be facilitated to support learning and pro-active decision-making.

Key policy insights

1. Introduction

Climate change is recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as one of the greatest threats to human health in the twenty-first century (WHO, Citation2015b). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) supports this statement by providing evidence showing that humans are drastically altering the global climate and thereby impacting human health (IPCC, Citation2021b). In addition, health is often impacted by non-climatic drivers, such as environmental conditions (e.g. geography or vegetation), the social infrastructure in a country and the adaptative capacity of a public health system (Semenza et al., Citation2016; Watts et al., Citation2019).

Strategies aiming to make the health system more climate-resilient are part of the so-called adaptation to climate change, which ensures a system is prepared for changing environmental conditions. Adaptation should go alongside mitigation, i.e. reducing the emissions of greenhouse gases and other environmental impacts to prevent environmental conditions from changing (Smith et al., Citation2014). Several authors point out that successful policies and technologies associated with reducing greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to the consequences are likely to generate health co-benefits (European Commission, Citation2020; Fox et al., Citation2019; Kendrovski & Schmoll, Citation2019; Sharifi et al., Citation2021; Watts et al., Citation2021). Vice versa, promoting the results of health adaptation is a powerful means of highlighting the potential consequences of climate change and promoting adaptation in other sectors (Watts et al., Citation2021).

In 2021, the European Commission brought forward the EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change and Communication on the European Green Deal that commits the EU and member states to continuously strengthen adaptive capacity and consequently climate resilience in health systems (European Commission, Citation2020). The Commission is supported in its efforts by the European Climate and Health Observatory, which provides access to relevant information and fosters information exchange and cooperation between relevant international, European, national and non-governmental actors (European Climate and Health Observatory, Citation2022).

Member states are required to every two years ‘report information to the Commission on their national adaptation planning and strategies, outlining their implemented or planned actions to facilitate adaptation to climate change’ (Regulation (EU) No 525/2013, Citation2013). Mainstreaming of adaptation activities and increased coherence is one of the pillars in the New European Adaptation Strategy (European Commission, Citation2021). To this end, the Commission commits to a ‘Health in all policies approach’ that builds on the idea that improving population health in a changing climate is a cross-border issue (European Commission, Citation2020).

Kendrovski and Schmoll (Citation2019) found that the need to integrate health and climate change in all policies is well recognized and often implemented in cities. However, there is more diversity in adaptation efforts and documents as opposed to a national level and the extent of cross-sectoral involvement varied greatly (Göpfert et al., Citation2019). Similar trends were observed in a study of 200 cities in Europe (Reckien et al., Citation2014), which stands out as the region with the highest percentage of cities (71%) with more than one million inhabitants that have, to some extent, adaptation policies (Araos et al., Citation2016).

Yuille et al. (Citation2021) stated that with regard to health system adaptation, urban policymakers have a feeling of being in unexplored and experimental waters. Despite the ambitious commitments set out in local strategies and knowledge of the health risks resulting from climate change, the understanding of how this should be incorporated in adaptation policy and planning is lacking (Yuille et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, the health impacts of climate change vary greatly across and within cities. If adaptation policy and planning fails to account for such impacts on different subgroups of the population, it might fail to tackle adverse health effects (Kim, Citation2020).

In this context, we set out to determine how public health risks are presently integrated in climate change adaptation documents on the national level in the European Union, how they are integrated in policy and planning on an urban level in the European Union and what the future priorities are on both spatial scales. To answer this, we performed a systematic content analysis of the European climate change National Adaptation Strategies (NASs) and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) and investigated how climate change-related health risks are integrated into these documents. We also carried out semi-structured interviews with experts and policymakers directly involved in the development of climate plans at a local level and interrogated the integration of health aspects into urban adaptation strategies and the future prospects in this field.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, the methodological approach and study design are described, and Section 3 systematically addresses the results of the analyses. In Section 4, we discuss the results in light of previous research and outline policy implications of the study. In Section 5, the conclusions drawn in this study are presented.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

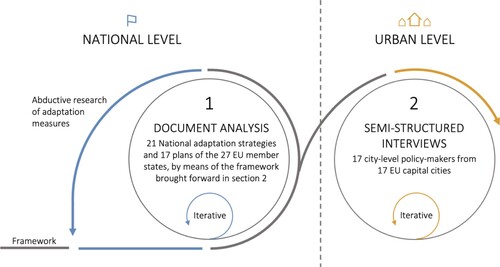

In this study, we built a framework to analyse the integration of health topics in climate change adaptation policy and planning. To this end, we first performed a systematic review of available studies addressing climate-resilience in the health sector, studies that discuss strategies for health system resilience, and studies that describe the costs and benefits arising from the adaptation of health systems. The search was conducted between February 2021 and July 2021 in Google Scholar, PubMed and Web of Science. In addition, indicators for climate-resilience in health systems and best practices for climate-resilience were derived from various health ministries, research papers and multilateral organizations such as the WHO and the Lancet Commission on Health and Climate change. Thereafter, we conducted a detailed analysis of 21 national adaptation strategies and 17 national adaptation plans dating from 2008 to 2020 drafted by member states of the European Union and interviewed city-level experts on the integration of health in climate change adaptation policy and planning. The analysis results in findings on two governance levels: at a national level and an urban level ().

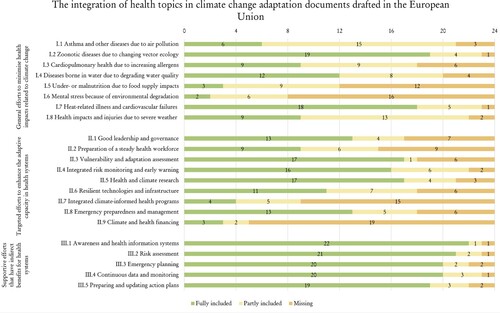

Based on previous approaches to the topic (i.e. Blanchet et al., Citation2017; Cheng & Berry, Citation2013; English et al., Citation2009; European Commission, Citation2021; Watts et al., Citation2021; WHO, Citation2015a), we reasoned that urban or national climate change adaptation documents, policy and planning should cover three categories of climate adaptation efforts and measures to address adverse health impacts (): general efforts to minimize health impacts related to climate change (I), targeted efforts to enhance the adaptive capacity in health systems (II); and supportive efforts that have indirect benefits on health systems (III) (Column 1 in ). For each of the efforts in the three categories, adaptation measures can be taken to cope with the adverse effects (Column 2 in ). A detailed description of the framework can be found in supplementary material 1.

Table 1. Examples of adaptation measures that can be taken to increase climate resilience in health systems.

2.2. Document analysis

In the 27 European member states, 21 national adaptation strategies and 17 national adaptation plans were drafted dating from 2008 to 2020 and analysed in the present paper. Three countries did not publish a formal adaptation document (Greece, Romania and Slovenia), five countries only published an adaptation strategy (Hungary, Italy, Malta, Poland and Slovakia) and three countries only an adaptation plan (Ireland, Latvia and Spain). Three countries integrated the adaptation strategy and plan into one document (Austria, Bulgaria and Luxembourg) (Supplementary material 2).

In the document analysis, processes consisted of collecting the adaptation documents and filtering the relevant information following the research framework introduced in . The colour orange and letter ‘M’ (missing) were assigned when the adverse effects of climate change on health or the health sector were not described in an adaptation document. The colour yellow and letter ‘P’ (partly) were assigned when the negative impacts of climate change on health were recognized, but no measures () were described to minimize these impacts. Lastly, the green colour and letter ‘F’ (fully) were assigned when at least one adaptation measure () was described in an adaptation document (Supplementary material 3). In a subsequent step, the framework was applied again and an explanation provided for why a colour was assigned to an element (Supplementary material 4). Ultimately, it was verified whether the same standard was maintained for all countries throughout the framework and whether the results were coherent was verified. Throughout the process, the framework was subjected to empirical scrutiny and missing adaptation measures were added to .

Table 2. The questions asked during the semi-structured expert interviews.

2.3. Semi-structured expert interviews

At an urban level, we elected to conduct interviews rather than looking at adaptation documents as we did at a national level. This decision was made given that documents at a local level (e.g. climate action plan, climate adaptation plan, climate and energy plans, green city strategies) are considerably more diverse than climate adaptation documents at a national level. As a result, adaptation documents at an urban level were not deemed comparable by means of the framework described in the conceptual basis (Section 2). However, the interview structure was chosen to present results along the lines of the three categories of adaptation efforts described in Section 2.

In total, twelve questions were asked, covering five topics () which are analysed along the lines of the framework and the framework method by Gale et al. (Citation2013). First, the interviewee’s organization’s role and responsibility in relation to climate adaptation and health was ascertained, after which the experts were asked if they faced challenges during the implementation of the adaptation efforts. Subsequently, the collaboration network and research evidence needed to draft and implement the plans was addressed. Lastly, the interviewees were asked if the Covid-19 pandemic had consequences for their adaptation efforts.

We aimed to select experts directly involved in the development of urban climate plans. The interviewees were identified through an internet search of the city departments responsible for the development of urban climate plans in each capital. Experts from the pool of city departments were invited for an interview by email. From the 27 departments we contacted, 18 agreed to an interview, each from a European capital city (Vienna, Zagreb, Sofia, Prague, Amsterdam, Tallinn, Stockholm, Riga, Budapest, Lisbon, Madrid, Helsinki, Rome, Brussels, Copenhagen, Nicosia, Vilnius and Dublin). The departments that declined the interview faced constraints in time, resources, perceived lack of content knowledge or a combination of these constraints. In the end, interviews were held with five climate coordinators, four urban planners, two adaptation specialists, two health care specialists, one green transition strategist, one climate specialist and one climate consultant. The interviews were carried out between 20 April and 3 June 2021 and lasted approximately 45 min each. With the exception of four interviews which were conducted in the local language (Brussels, Amsterdam, Madrid and Rome), the interviews were carried out in English. Prior to the interviews, the experts were informed of their rights and the procedures applied when processing their personal data, which is in accordance with the data protection legislation (the General Data Protection Regulation and Personal Data Act). All interviewees orally agreed to the terms at the start of the interview.

3. Results

3.1. Climate change-related health adaptation on a national scale

In line with the framework ((a)), eight general adaptation efforts to minimize health impacts related to climate change (I1-I8) are needed in an exhaustive climate adaptation strategy or plan. The analysis of the adaptation documents drafted in the European Union yielded mixed results. Regarding the general efforts to minimize health risks of climate change, zoonotic and vector-borne diseases (I.2) and heat-related illness and cardiovascular failures (I.7) are described as adverse health effects in national adaptation documents; and measures are frequently described to monitor disease vectors and develop a heatwave action plan. Water-borne diseases (I.4), health impacts related to severe weather (I.8) and cardiopulmonary health (I.1) are frequently recognized and described as problematic, but less attention is given to measures to tackle these are problems. Measures to protect against environmental stressors are often described, but not complemented by direct interventions in the health sector. Lastly, undernutrition, malnutrition (I.5) and mental stress (I.6) resulting from environmental degradation are poorly recognized ().

Figure 2. The integration of adaptation measures related to health topics described in the 24 national climate adaptation documents drafted in the European Union.

(b) describes nine targeted efforts to enhance the adaptive capacity in health systems (II.1-II.9). Of these, health and climate research (II.5) is most frequently incorporated in adaptation documents, usually through measures that foster international partnerships and cross-border research. Efforts to carry out vulnerability, capacity and adaptation assessments in the health sector (II.3), and integrated risk monitoring and early warning (II.4) are also often included, as measure to monitor allergens, temperatures, pollution rates and vectors. However, the active preparation and management of emergency situations in which environmental stressors are too high (II.8) is often overlooked and remains vague in the documents. It is a mixed picture when analysing measures to safeguard a steady health workforce (II.2) and climate-resilient infrastructure (II.6). Measures are often simple, such as including an education package on climate change and ensuring suitable indoor temperatures in hospitals, rather than being more in-depth, such as ensuring the availability of medical technologies or ample medicine. Lastly, adaptation documents rarely include full information on climate and health financing (II.9) or the preparation of an integrated climate-informed health programme (II.7) ().

In order for efforts in categories I and II to be effective, five supportive efforts that have indirect benefits for health systems (III.1-III.5) also need to be included in adaptation documents ((c)). Fortunately, these are covered comprehensively in most documents, likely as such efforts are often part of the process of drafting an adaptation document. The documents are less detailed regarding the description of efforts to improve emergency planning (III.3) and updating of the adaptation strategies (II.5).

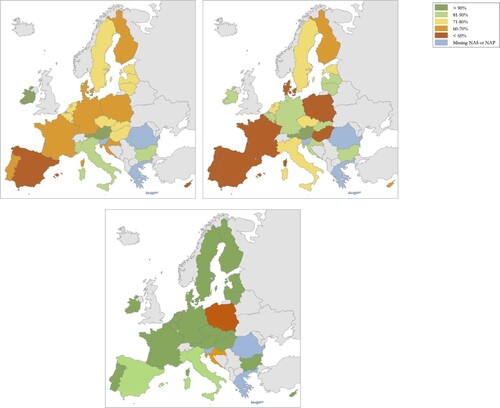

Generally, the above-described adaptation efforts are more frequently and clearly described in the adaptation documents of North-West Europe rather than South-East Europe. However, there are notable exceptions. For example, regarding the general efforts to minimize health impacts related to climate change (I) ((a)), Ireland and Austria demonstrate the most comprehensive coverage, followed by Luxembourg, Italy and Bulgaria. Similar results are found for the targeted efforts to enhance the adaptive capacity in health systems (II) ((b)). Aside from documents developed in France and Denmark, targeted efforts are comprehensively described in most documents drafted in North-West Europe compared to South-East Europe. However, this does not apply to the documents developed in Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Croatia and Italy. Lastly, the assessment of the description of supportive efforts that have indirect benefits for health systems (III) ((c)) showed results at the extremes of the spectrum: either the adaptation documents provide a comprehensive overview of supportive efforts, or the efforts are completely disregarded.

3.2. Climate change-related health adaptation on an urban scale

The integration of health in climate change adaptation policy and planning at an urban level differs from the integration of health in national adaptation documents. With the exception of heat-related illness and cardiovascular failures (I.7), general efforts to minimize health impacts related to climate change (I) are often seen as the responsibility of the national ministries. This is especially true for zoonotic diseases due to changing vector ecology (I.2) and health impacts and injuries as a result of severe weather (I.8). Efforts to enhance cardiopulmonary health due to increasing allergens (I.3) and under- or malnutrition due to food supply impacts (I.5) are rarely mentioned during the interviews, which leads us to believe that such efforts are not included in climate adaptation documents, policy, and planning at an urban level. If efforts are included in urban adaptation policy and planning, they are often included as indirect benefits of other adaptation efforts. As an indication, mental stress (I.6), diseases due to the longer and more intense air pollution (I.1) and to a lesser extent water-borne diseases (I.4) are seen as a benefit of measures that aim to increase urban greening or active mobility. This is especially the case for cities that have an energy action plan, a green infrastructure action plan or a Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP).

As health is only included as an indirect benefit of other climate change adaptation efforts, targeted efforts to enhance the adaptive capacity in health systems (II) are often left unaddressed in cities. As an indication, almost nothing was mentioned in the interviews regarding the preparation of a steady health workforce (II.2), climate-resilient technologies and infrastructure (II.6) and integrated climate-informed health programmes (II.7). Nevertheless, most experts expect that the interconnection between climate and health will become more important in adaptation policy and planning over the next few years. They indicate that the responsibility for drafting and implementing adaptation efforts should be spread out over multiple departments or administrative units. Furthermore, the interviewees also indicated that their departments often work together with external experts, such as energy agencies, waste management organizations, research institutions and emergency rescue teams. Considering the latter, the experts work together on emergency preparedness and management (II.8) and integrated risk monitoring and early warning systems (II.4).

Regarding good leadership and governance (II.1), most interviewees are critical of the current national policy addressing climate adaptation in the health sector. Some, however, are positive. Half the experts indicate there is excessive bureaucracy, and the other half a lack of urgency, at the national level. The excessive bureaucracy can be attributed to a mismatch between adaptation efforts at a national and urban level. The national adaptation documents are usually too broad and not adaptable for the city. Furthermore, a sectoral approach taken nationally, allows sectors to operate in silos at a local level; some silos urgently act upon climate change, whereas others fall behind. The lack of urgency often goes hand in hand with a low budget (II.9). Half of the interviewees have frequent interactions with the ministries of environment or health, and most experts would like to strengthen this cooperation.

In the interviewees’ departments, a wide variety of sources of knowledge are used when drafting adaptation strategies and plans. However, as most urban departments have only recently begun to recognize the connection between climate and health, experts found it difficult to clearly articulate knowledge gaps (II.5). Many experts also suggest that quantitative data, indicators and methods are needed to measure the impacts of climate change on health, especially at a local level. Of note, half of the interviewees said that they would rather receive insights from other cities on their best practices than do more research. Some experts have said that they take health risks into account because they are aware of vulnerable groups (e.g. elderly, disabled, chronically ill, homeless, and mothers with young children). However, a formal vulnerability, capacity, and adaptation assessment (II.3) was rarely mentioned in the interviews.

Except for the development of an assessment of the risks of climate change (III.2), the other supportive efforts that have indirect benefits for health systems (III) are poorly addressed in climate adaptation policy and planning at an urban level. Responsibility for awareness and health information systems (III.1) is often national and the responsibility for emergency planning (III.3) often lies with external organizations. The experts noted that they closely monitor their efforts (III.4) and update documents, policy and planning accordingly (III.5). However, relatively few experts indicate that their department cooperates with hospitals, businesses, citizens, or the media to monitor the results of their efforts on the ground. Encouragingly, most experts would like to broaden their collaboration activities to look for innovative solutions to climate adaptation.

The COVID-19 pandemic created momentum to better integrate health into adaptation policy and planning. In this regard, many experts indicated that they connect health and climate change more frequently as a result of the pandemic and most stressed that the pandemic has led to increased awareness of the adverse effects of climate change on mental health (I.6) and the importance of taking care of vulnerable groups. The adverse mental health effects of the strict lockdowns implemented in many countries are well recognized. This has led to an increased awareness of the importance of a healthy living environment with comfortable living temperatures, low levels of pollution, and ample green and blue infrastructure. As these issues are also tackled by successful climate change adaptation and mitigation efforts, the importance of such efforts seems to be better recognized.

4. Discussion

Integrating public health risks in climate change adaptation policy and planning can boost climate adaptation strategies, while safeguarding climate resilience in health systems and generating many related co-benefits (IPCC, Citation2021a; WHO, Citation2010; Yuille et al., Citation2021). This paper provides a baseline assessment of the integration of public health into climate change adaptation documents, policy and planning in a European context. We outline priorities to help climate and health policymakers take efficient and robust adaptation measures.

The results of the analysis contribute to a substantial body of literature dedicated to facilitating climate resilience in health systems (e.g. Ebi, Citation2013; Otto et al., Citation2017; Berry et al., Citation2018; Runhaar et al., Citation2018; Woodhall et al., Citation2021). The results complement the analysis of the European Environment Agency (EEA) and the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). Specifically, the EEA evaluated all national adaptation policies and addressed infectious disease surveillance, Early Warning Systems for heat waves and climate-resilient health infrastructures. The IISD investigated health adaptation measures in 19 national adaptation documents drafted in developing countries (European Environment Agency, Citation2016; WHO, Citation2021).

Before discussing the results, some limitations need to be considered. First, co-benefits between health and climate change adaptation policy and planning are likely to be most pronounced when adaptation efforts are not only comprehensively documented, but also fully implemented. The framework applied in this study for analysing the documents, and to a lesser extent the interviews, only assesses whether measures are properly documented. But equally, adaptation efforts might be implemented, but not then described in the adaptation documents. A second limitation pertains to the application of the framework. A country’s adaptation efforts were assessed as adequate when at least one adaptation measure () was included. Therefore, it is not possible to distinguish between an authority that is taking just one action and those that are implementing multiple complementary measures.

Analysis of the adaptation documents at a national level and analysis of the interviews at an urban level showed some clear patterns. At a national level, certain general efforts (I), such as those taken to tackle vector-borne diseases and heat-related illnesses, are described comprehensively in the adaptation documents and adaptation measures to address them are outlined. General efforts to respond to water-borne diseases, health impacts related to severe weather and cardiopulmonary health are recognized as critical, but are not described in detail. By contrast, efforts to address undernutrition, malnutrition and mental health are not outlined at all. Targeted efforts (II) to explicitly incorporate the risks of climate change and make informed decisions, such as carrying out research, vulnerability assessments or integrated risk monitoring and early warning, are often described in detail in national adaptation documents. However, efforts to manage day-to-day health care delivery and emergency situations appear to be neglected. Comprehensive and detailed information is rarely provided on climate and health governance, financing, emergency planning or efforts to safeguard the health workforce and climate-resilient infrastructure. The supportive efforts (III) that sustain the success of general and targeted efforts are generally described in a comprehensive manner in the adaptation documents.

When planning and describing adaptation efforts, policy planners can build on the strengths of adaptation documents from other countries, and take note of any weaknesses in those documents. This was also found in a similar assessment that was carried out in Africa, South-America and South-east Asia (WHO, Citation2021): general efforts to address vector-borne diseases and heat-related illness were described in detail, whereas mental health issues were often overlooked. In contrast, efforts to address water-borne diseases, health impacts related to severe weather, malnutrition and food-borne diseases were better described in developing countries. Targeted efforts to safeguard a steady health workforce are also more comprehensively addressed.

In contrast to the national level, where health topics have been incorporated into urban adaptation policy and planning, they are often included as indirect benefits of other adaptation efforts (e.g. by promoting active mobility and urban greenery, health impacts related to heat, stress and air pollution are reduced). As a result, general (I) and targeted (II) efforts are often seen as the responsibility of other departments and administrative units, and supportive efforts (III) are often seen as the responsibility of the national government or external organizations. There are a few exceptions: first, general efforts to address heat-related illness and mental health impacts are often included in urban climate adaptation planning. The same applies to targeted efforts to improve integrated risk monitoring and emergency preparedness. Lastly, cities often develop a risk and vulnerability assessment and monitor the success of their efforts, but public participation in these matters appears to be insufficient.

In order for health risks to be better integrated into urban adaptation policy and planning, it is critical to reduce sectoral thinking, foster collaboration between departments and welcome external expertize to develop ambitious and innovative adaptation commitments. The latter can be implemented by increasing public participation or by strengthening ties with existing communities of practice, such as C40 Cities, Canada’s Climate Change Adaptation Community of Practice and ICLEI. Similarly, Reckien et al. (Citation2015), Aguiar et al. (Citation2018) and Woodhall et al. (Citation2021) call for a strong regulative framework in which cooperation between public authorities is facilitated and coordinated. In addition, Runhaar et al. (Citation2018) call for clear routines, practices, indicators and methods to implement and measure the effectiveness of adaptation efforts.

The interconnection of climate change and health topics at an urban level is also improved by being wary of the mismatch between national and local adaptation needs. Often, national adaptation documents are too broad or non-specific to be adapted at an urban level. As a result, detailed information is lacking on how the magnitude and patterns of climate change interconnect with health issues on a local scale. In this regard, the experts we talked to underlined that for this to happen, it is important to simplify and facilitate large-scale data collection and sharing of health and climate indicators on an urban scale. Similarly, Runhaar et al. (Citation2018) call for clear routines, practices, indicators and methods to implement and measure the effectiveness of adaptation efforts, in combination with more higher-level national and sub-national support. In contrast, Yuille et al. (Citation2021) found that, on the one hand, adaptation efforts in cities are often constrained by national policies but, on the other hand, high-level support can be undermined by a contentious local implementation.

While the focus of this paper is on adaptation, it is important to coordinate both mitigation and adaptation measures and foster synergies between these (Sharifi et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, adaptation might be more successful if ambitious mitigation is in place. Lastly, co-benefits can be found between mitigation and adaptation. For example, promoting active mobility and public transport over individual car use could reduce greenhouse gas emissions and simultaneously reduce the health risks of pollution from cars. In addition, urban green spaces could mitigate the negative health effects of urban pollution and contribute to improved mental health. This need was also recognized by the interviewees, who stressed the importance of a healthy living environment with comfortable living temperatures, low levels of pollution, and ample green and blue infrastructure.

Future work should therefore focus on how to cooperatively draft strategies across national and local levels and thereby facilitate cooperation between society, networks (e.g. C40 and ICLEI), policy sectors, cities and countries. Furthermore, equity and environmental justice should be at the forefront of future adaptation. Societal inequality among populations in urban settings is a major issue and there is increased momentum to involve local communities in adaptation planning and implementation in order to avoid risks of maladaptation and failure (Sharifi et al., Citation2021). In this regard, it would be interesting to look for success cases and build upon the lessons learned in these cases. We thus recommend that future research should focus on the co-benefits of specific adaptation interventions and improving the synergies among different interventions and on different geographic levels.

The COVID-19 pandemic increased awareness about the importance of a healthy living environment for all and thereby created momentum to better integrate health topics into climate change adaptation policy and planning and to take a more sustainable approach. This is especially true of efforts aimed at improving living circumstances to increase mental health and benefit vulnerable groups (Reckien et al., Citation2015). All such efforts, however, need to be underscored by adequate and coordinated adaptation planning at national and local levels.

5. Conclusion

The study assesses the extent to which public health is integrated into European national and urban climate change adaptation policy. We reasoned that policy should cover three categories of climate adaptation efforts to adequately address adverse health impacts, namely: general efforts to minimize health impacts related to climate change (I), targeted efforts to enhance the adaptive capacity in health systems (II); and supportive efforts that have indirect benefits on health systems (III).

The results show different priorities at the national and urban levels. At the urban level, general (I) and targeted (II) efforts are often seen as the responsibility of other departments and administrative units, and supportive efforts (III) are often seen as the responsibility of the national government or external organizations. In turn, at the national level, some aspects are comprehensively described in the adaptation document, whereas others are not.

In order for health risks to be better integrated into adaptation policy and planning, it is critical to interconnect national and urban levels, reduce sectoral thinking and welcome external expertize to develop ambitious and innovative adaptation commitments. The experts we talked to underlined that it would be good to facilitate large-scale data collection and sharing of health and climate indicators. Furthermore, policy planners can build on the strengths of adaptation documents from other countries or cities and take note of any weaknesses.

We recommend focussing on how to cooperatively draft strategies across national and local levels and thereby facilitate joint-up work between society, networks (e.g. C40 and ICLEI), policy sectors, cities and countries. This will also foster health equity and environmental justice, which is critical for successful adaptation. Furthermore, as the COVID-19 pandemic increased awareness about the importance of a healthy living environment (e.g. plenty of green space, healthy air quality and sustainable temperatures) on mental wellbeing and physical health, it is critical to foster co-benefits of various adaptation measures.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (720.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aguiar, F. C., Bentz, J., Silva, J. M. N., Fonseca, A. L., Swart, R., Santos, F. D., & Penha-Lopes, G.. (2018). Adaptation to climate change at local level in Europe: An overview. Environmental Science & Policy, 86, 38–63. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.04.010

- Araos, M., Berrang-Ford, L., Ford, J. D., Austin, S. E., Biesbroek, R., & Lesnikowski, A. (2016). Climate change adaptation planning in large cities: A systematic global assessment. Environmental Science & Policy, 66, 375–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.06.009

- Berry, P., Enright, P., Shumake-Guillemot, J., Villalobos Prats, E., & Campbell-Lendrum, D. (2018). Assessing health vulnerabilities and adaptation to climate change: A review of international progress. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(12), 2626. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122626

- Blanchet, K., Nam, S. L., Ramalingam, B., & Pozo-Martin, F. (2017). Governance and capacity to manage resilience of health systems: Towards a New conceptual framework. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 6(8), 431–435. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2017.36

- Cheng, J. J., & Berry, P. (2013). Development of key indicators to quantify the health impacts of climate change on Canadians. International Journal of Public Health, 58(5), 765–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-013-0499-5

- Ebi, K. L. (2013). Protecting health from climate change: Vulnerability and adaptation assessment. World Health Organization.

- English, P. B., Sinclair, A. H., Ross, Z., Anderson, H., Boothe, V., Davis, C., Ebi, K., Kagey, B., Malecki, K., Shultz, R., & Simms, E. (2009). Environmental health indicators of climate change for the United States: Findings from the state environmental health indicator collaborative. Environmental Health Perspectives, 117(11), 1673–1681. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.0900708

- European Climate and Health Observatory. (2022). About the European Climate and Health Observatory. https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/observatory/About

- European Commission. (2021). Forging a climate-resilient Europe – the new EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change. European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/clima/sites/clima/files/adaptation/what/docs/eu_strategy_2021.pdf

- European Commission. Directorate General for Research and Innovation. & European Commission Group of Chief Scientific Advisors. (2020). Adaptation to health effects of climate change in Europe. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.277730323

- European Environment Agency. (2016). European forest ecosystems state and trends. EUR-OP.

- Fox, M., Zuidema, C., Bauman, B., Burke, T., & Sheehan, M. (2019). Integrating public health into climate change policy and planning: State of practice update. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(18), 3232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183232

- Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., & Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

- Göpfert, C., Wamsler, C., & Lang, W. (2019). A framework for the joint institutionalization of climate change mitigation and adaptation in city administrations. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 24(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-018-9789-9

- IPCC. (2021a). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J. B. R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu and B. Zhou (Eds.)]. Cambridge University Press.

- IPCC. (2021b). The Sixth Assessment Report is underway. https://www.ipcc.ch/assessment-report/ar6/

- Kendrovski, V., & Schmoll, O. (2019). Priorities for protecting health from climate change in the WHO European region: Recent regional activities. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz, 62(5), 537–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-019-02943-9

- Kim, E. J. (2020). Cities, climate change, and public health. Anthem Press.

- Otto, I. M., Reckien, D., Reyer, C. P. O., Marcus, R., Le Masson, V., Jones, L., Norton, A., & Serdeczny, O. (2017). Social vulnerability to climate change: A review of concepts and evidence. Regional Environmental Change, 17(6), 1651–1662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1105-9

- Reckien, D., Flacke, J., Dawson, R. J., Heidrich, O., Olazabal, M., Foley, A., Hamann, J. J.-P., Orru, H., Salvia, M., De Gregorio Hurtado, S., Geneletti, D., & Pietrapertosa, F. (2014). Climate change response in Europe: What’s the reality? Analysis of adaptation and mitigation plans from 200 urban areas in 11 countries. Climatic Change, 122(1-2), 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0989-8

- Reckien, D., Flacke, J., Olazabal, M., & Heidrich, O. (2015). The influence of drivers and barriers on urban adaptation and mitigation plans – an empirical analysis of European cities. PLOS One, 10(8), e0135597. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135597

- Regulation (EU) No 525/2013 (2013) Regulation (EU) No 525/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2013 on a mechanism for monitoring and reporting greenhouse gas emissions and for reporting other information at national and Union level relevant to climate change and repealing Decision, Pub. L. No. No 525/2013.

- Runhaar, H., Wilk, B., Persson, Å., Uittenbroek, C., & Wamsler, C. (2018). Mainstreaming climate adaptation: Taking stock about “what works” from empirical research worldwide. Regional Environmental Change, 18(4), 1201–1210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1259-5

- Semenza, J. C., Lindgren, E., Balkanyi, L., Espinosa, L., Almqvist, M. S., Penttinen, P., & Rocklöv, J. (2016). Determinants and drivers of infectious disease threat events in Europe. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 22(4), 581–589. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2204.151073

- Sharifi, A., Pathak, M., Joshi, C., & He, B.-J. (2021). A systematic review of the health co-benefits of urban climate change adaptation. Sustainable Cities and Society, 74, 103190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.103190

- Smith, K. R., Woodward, A., Campbell-Lendrum, D., Chadee, D. D., Honda, Y., Liu, Q., Olwoch, J. M., Revich, B., & Sauerborn, R. (2014). Human health: Impacts, adaptation, and co-benefits. In: Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. (Contribution of working group II to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change part A: Global and sectoral aspects.). Cambridge University Press.

- Watts, N., Amann, M., Arnell, N., Ayeb-Karlsson, S., Beagley, J., Belesova, K., Boykoff, M., Byass, P., Cai, W., Campbell-Lendrum, D., Capstick, S., Chambers, J., Coleman, S., Dalin, C., Daly, M., Dasandi, N., Dasgupta, S., Davies, M., Di Napoli, C., … Costello, A. (2021). The 2020 report of The lancet countdown on health and climate change: Responding to converging crises. The Lancet, 397(10269), 129–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32290-X

- Watts, N., Amann, M., Arnell, N., Ayeb-Karlsson, S., Belesova, K., Boykoff, M., Byass, P., Cai, W., Campbell-Lendrum, D., Capstick, S., Chambers, J., Dalin, C., Daly, M., Dasandi, N., Davies, M., Drummond, P., Dubrow, R., Ebi, K. L., Eckelman, M., … Montgomery, H. (2019). The 2019 report of The lancet countdown on health and climate change: Ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate. The Lancet, 394(10211), 1836–1878. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32596-6

- WHO. (Ed.). (2010). Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: A handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. World Health Organization.

- WHO. (Ed.). (2015a). Operational framework for building climate resilient health systems. World Health Organization.

- WHO. (2015b). WHO calls for urgent action to protect health from climate change. https://www.who.int/globalchange/global-campaign/cop21/en/

- WHO. (2021). Health in national adaptation plans: Review. (Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.).

- Woodhall, S. C., Landeg, O., & Kovats, S. (2021). Public health and climate change: How are local authorities preparing for the health impacts of our changing climate? Journal of Public Health, 43(2), 425–432. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdz098

- Yuille, A., Tyfield, D., & Willis, R. (2021). Implementing rapid climate action: Learning from the ‘practical wisdom’ of local decision-makers. Sustainability, 13(10), 5687. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105687