ABSTRACT

How do non-governmental organizations (NGOs) target governments for climate shaming? NGOs increasingly function as monitors of states climate performance and compliance with international climate treaties such as the Paris Agreement. Lacking formal sanctioning capacities, NGOs primarily rely on ‘naming and shaming’ to hold states accountable to their commitments in climate treaties and to ramp up their climate mitigation efforts. However, we know little about how and why NGOs engage in climate shaming. This article advances two arguments. First, we argue that NGO climate shaming is likely to be shaped by the international and national climate records of governments. Second, governments’ climate actions can create contradicting expectations by both inviting and repelling NGO climate shaming. To test our arguments, we complied an original global data set on climate shaming events carried out by environmental NGOs. Our empirical analysis suggests that while NGOs are generally more likely to shame climate laggards, climate frontrunners may also be shamed if they engage in non-binding climate commitments.

Key policy insights

Climate laws and international climate treaties are central for our understanding of how NGOs target governments for climate shaming.

NGOs are generally more likely to target climate laggards than frontrunners.

Climate shaming is not only about whether but also how governments participate in global climate governance.

Membership in climate institutions with non-binding commitments attracts NGO climate shaming.

There is a risk that governments sign international climate treaties, without the intention to comply, in order to escape climate shaming.

1. Introduction

How and why do environmental non-governmental organizations (NGOs) select governments for climate shaming? Most global environmental agreements, such as the Paris Agreement, put much of the burden for government accountability and monitoring on NGOs (Falkner, Citation2016). Though they cannot directly punish countries for non-compliance, NGOs’ ‘naming and shaming’ campaigns can hold governments accountable and may be effective in facilitating political action through reputational costs (Franklin, Citation2008; Jacquet & Jamieson, Citation2016; Keck & Sikkink, Citation1998; Taebi & Safari, Citation2017). Given the key role attributed to public NGO shaming for reaching global climate targets (van Asselt, Citation2016; Falkner, Citation2016; Jacquet & Jamieson, Citation2016), accounting for the dynamics of NGO climate shaming is a key research task.

The question of how and why organizations select their targets for shaming campaigns is well-rooted in the political science and sociology literatures. For example, researchers have examined the targeting practices of social movements (Bartley & Child, Citation2014), intergovernmental organizations (Lebovic & Voeten, Citation2009), governments (Koliev, Citation2020), and NGOs (Ron et al., Citation2005). Existing research on NGOs, which focuses mainly on human rights, provides somewhat mixed results. Researchers debate whether NGOs tend to focus on ‘easy cases’ – that is, countries that are already planning to change their policies (Stroup & Wong, Citation2017, p. 66) – or rather target ‘hard cases’ (Koliev, Citation2021, p. 406). Whereas some argue that NGOs tend to shame countries that have restricted political opportunity structures (Murdie & Urpelainen, Citation2015), others do not find such effects (Ron et al., Citation2005, p. 570). In addition, previous studies highlight civil society strength (Meernik et al., Citation2012), governments’ international ties (Hendrix & Wong, Citation2014), and donors’ preferences of NGOs (Koliev, Citation2021) as the main determinants of NGO shaming activities.

We contribute to this literature by examining the climate shaming activities of environmental NGOs. How do NGOs select governments for climate shaming? Do environmental NGOs target climate laggards – i.e. governments that make no or few commitments to international agreements and domestic climate laws – or do they focus more on climate frontrunners, that is, governments that have stronger international and domestic climate credentials? Can governments receive less NGO shaming through other actions than reducing emissions? While the answers to these questions have important implications for the effectiveness and legitimacy of environmental NGOs, we know little about the determinants of climate shaming. Among the few studies that have contributed to knowledge within this field is Murdie and Urpelainen’s (Citation2015) study of environmental NGOs. They find that environmental NGOs primarily target non-democratic states because they lack political opportunity structures that would allow civil society groups to put pressure on their governments (Murdie & Urpelainen, Citation2015, p. 358). However, they also find that environmental NGOs are less likely to criticize countries with high CO2 emissions, suggesting that NGOs may avoid selecting the highest emitters for naming and shaming because they are less likely to change their behavior (Murdie & Urpelainen, Citation2015, p. 365). If high emitters, such as China and Saudi Arabia, escape NGO climate shaming, it could potentially erode the authority and legitimacy of shaming efforts, especially considering the role of NGOs in global agreements based on the ‘pledge and review’ system.

Our study makes several contributions to the literature. First, we move beyond human rights NGO shaming by focusing on environmental NGOs. In contrast to Murdie and Urpelainen (Citation2015), we focus specifically on climate shaming rather than environmental shaming more generally.

Second, theoretically, we consider both domestic and international determinants of NGO climate shaming. We argue that the main factors shaping NGO climate shaming are governments’ international and national climate action records. The international climate action activities relate to the number of climate agreements (ICAs)Footnote1 that a country has signed, while national climate action pertains to the climate laws that a country has passed. Such ‘benchmark’ parameters can be observed with relative ease by NGOs, whereas parameters such as the ‘true’ climate ambitions and capacity of governments are more difficult to observe. However, governments’ climate action activities, or lack thereof, may both invite and avert NGO climate shaming. One key tradeoff is that between shaming climate laggards or forerunners. On the one hand, shaming laggards might be more effective in the sense that even small improvements might entail larger emission reductions. On the other hand, laggards are typically less responsive to shaming, which means that NGOs run the risk of wasting their shaming efforts. Shaming forerunners might seem counterintuitive, but the logic of raised expectations generated by commitments to climate treaties and laws can attract NGO shaming. Moreover, NGOs may have a better chance at gain leverage based on their shaming efforts if governments have made public pledges and commitments to climate action.

Third, we contribute to the literature by generating a novel dataset on climate shaming – defined as public criticism of governments – carried out by over 2000 environmental NGOs during the period 1990–2015. Taken together, this study provides the first systematic analysis of environmental NGOs’ climate shaming activities.

The rest of the article is structured as follows. In section two, we outline our main theoretical expectations. In section three, we present our research design, including methods and data used. Section four presents the findings of the study and section five provides a more extensive discussion of our results. Finally, in section six, we provide our conclusions.

2. Explaining NGO climate shaming

When selecting targets, NGOs must make informed decisions that optimize their chances to achieve their goals. Yet, decisions on whom to target entail prioritization since NGOs operate in an environment where labor, money, time, and media attention are scarce resources (Stroup & Wong, Citation2017). Due to the international nature of the climate change issue area, the major factors shaping the climate shaming decisions of NGOs are likely to reflect governments’ international as well as national climate action performance. At the international level, governments’ commitments to, and participation in, global climate change governance is crucial. Arguably, for NGOs, governments’ commitments to international environmental treaties are an important indicator of their political motivation to combat climate change. A plethora of studies have documented how NGOs both push for ambitious environmental and climate agreements during international negotiations and pressure governments to sign them (Raustiala, Citation1997). Studies on human rights shaming have also found that governments international commitments influence NGO shaming decisions (Koliev, Citation2021, p. 404).

While committing to international treaties is an important step, the international climate regime also stresses the role of domestic climate regulations (Victor, Citation2011). Indeed, NGOs are considered to be the watchdogs of domestic climate law reforms (Betsill & Corell, Citation2001, p. 67; Jacquet & Jamieson, Citation2016). At the national level, then, NGOs are likely to focus on political changes, such as the introduction of climate laws (or lack thereof). The Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) illustrates our rationale. The CPPI was developed by environmental NGOs in order to put the spotlight on governments that address climate issues, and which are lagging behind. To measure governments climate performance, the CPPI index puts heavy weight on yearly emissions, but also on governments’ commitments to international climate treaties and national laws.

Though environmental NGOs may be concerned about governments’ international and domestic climate actions, it is unclear in what way these actions affect NGO climate shaming. The idea that NGOs target climate laggards – merely looking at emissions – may be an oversimplification that ignores the nuances of NGO shaming strategies. Indeed, climate frontrunners or laggards might be rewarded with less criticism by NGOs for some actions, while being punished with criticism for other actions. For a more nuanced picture, then, we need to consider factors at both the international and domestic level. NGOs’ strategic considerations, made in the context of scarce resources and a willingness to achieve results, may lead to the selection of target states that have better or worse climate credentials.

2.1 The case for shaming climate frontrunners

The international and domestic climate activities of governments can create contradicting expectations by both inviting and repelling NGO climate shaming. There are several reasons to expect NGOs to be more likely to criticize climate frontrunners than climate laggards. First, governments that are active in global climate governance attract more NGO scrutiny because their engagement and pledges raise the expectations. Indeed, governments that have signed ICAs are by design held to higher standards that those that have not. Put simply, by promising to combat climate change, governments make themselves the potential targets of NGO climate shaming. Public commitments to global climate action create strong shaming incentives for NGOs because governments that have made promises are easier to criticize and to mobilize domestic public opinion against (Tingley & Tomz, Citation2022). The French government serves as an illustrative case. France had a prominent role in promoting a new global climate agreement – the Paris Agreement – when hosting the 2015 UN Climate Change Conference. After the adoption of the Paris Agreement, the French government pledged to reduce its emissions by 40% by 2030 and to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. But this pledge also came with more intense NGO scrutiny. Environmental NGOs, realizing the discrepancies between what was promised and what has been done, have increasingly criticized the French government for failing to live up to its climate pledges.Footnote2 In other words, by promising to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, governments make themselves more vulnerable to NGO climate shaming.

Second, governments’ domestic activities may also attract more criticism. While decreasing pollution and passing climate laws can be viewed as improvements, paradoxically, this can also lead to increased expectations and, thus, harsher NGO scrutiny. Climate laws expose governments to scrutiny by not only international NGOs, but also domestic actors, such as parliaments and courts, which can initiate more formal investigations (Falkner, Citation2016, p. 1122). Various domestic actors are likely to invoke their rights under climate laws and put more pressure on governments to comply with national laws. These dynamics may generate more information about climate-related issues that attract NGO attention, compared to states where domestic climate laws are not on the agenda. In addition, climate laws may attract criticism in cases where the laws are inadequately designed, or due to an unwillingness to enforce existing climate laws (UNEP, Citation2019, p. 8). For example, in 2021, Germany’s Constitutional Court ruled that the federal Climate Action Law was insufficient and lacked appropriate emissions reduction targets.Footnote3 This was followed by an immediate reaction by the German government, resulting in an amended climate bill. Prior to the ruling, environmental NGOs, including Greenpeace and Germanwatch, had issued several legal cases against the German government and had publicly criticized German climate laws. Based on this discussion, we formulate our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 ‘shaming climate frontrunners’: NGOs are likely to target governments displaying a better climate track record.

2.2 The case for shaming climate laggards

On the other hand, there are reasons to expect that NGOs would be less likely to shame countries that have a better international and domestic climate action record. First, NGOs are likely to shame climate laggards in hope of exhorting them to take action. The role of NGOs in global climate agreement negotiations is another aspect that is likely to make them recognize commitments to ICAs as significant improvements and thus reallocate their attention to governments that have made no or less climate commitments (Allan, Citation2018; Wapner, Citation1996). For example, during the COP summits, the Climate Action Network (CAN) named and shamed governments that were ‘doing the most to achieve the least’ related to climate agreements.Footnote4 Another prominent example is the withdrawal of the U.S. from the Paris Agreements, which brought massive shaming by environmental NGOs. Arguably, even if the US continued with climate reforms and laws to reduce its CO2 emissions, the fact that the U.S. withdrew from a major global climate accord would still attract negative attention.

Second, NGOs have incentives to show their donors and members (Koliev, Citation2021; Prakash & Gugerty, Citation2010) that they can contribute and make a difference in countries that lack ambitious climate action plans. However, achieving results in laggard states can be difficult and may backfire (Spektor et al., Citation2022). Despite this, NGOs might still have incentives to expose laggards to reflect their members and donors’ preferences (Koliev, Citation2021) and to build alliance with like-minded partners. Last but not least, pro-environmental groups in countries that lack climate laws are also likely demand the attention and scrutiny of international environmental NGOs (Keck & Sikkink, Citation1998; Pacheco-Vega & Murdie, Citation2021). Taken together, our expectation is that NGOs target climate laggards more than climate frontrunners.

Hypothesis 2 ‘shaming climate laggards’: NGOs are likely to target governments displaying less ambitious climate track record.

3. Methods

This study generates a novel dataset on climate shaming – defined as public criticism of governments – carried out by over 2000 environmental NGOs during the period 1990-2015.Footnote5 In contrast to previous studies (Murdie & Urpelainen, Citation2015), we utilize natural language processing (NLP) and multiple news sources to identify climate-related shaming events.

3.1 Data

We created an NGO climate shaming dataset to conduct this analysis. The dataset was created in several steps. First, we used the Yearbook of International Organization (YBIO) to identify international environmental NGOs. While there are several sources of data on international NGOs, the YBIO is the most comprehensive with regard to geographic scope and time coverage (Hadden & Bush, Citation2021, p. 210). Using the YBIO database, we searched for all NGOs focused on the environment. In total, we identified 2295 environmental NGOs that have a mission statement focused on core environmental issues. As a result, we included a large sample of different environmental NGOs, including major ones like Greenpeace and the World Wild Fund for Nature as well as smaller and less well-known NGOs, such as the Bears in Mind. We provide the full list of environmental NGOs in Table A1 in the Supplementary Material (SM).

Second, to capture the climate-related issues covered by the NGOs, we created a dictionary with keywords, such as climate change, coal, sea levels, global warming, greenhouse, COP, fossil fuel, and Kyoto Protocol (Table A2 in SM) Third, we define a shaming event as an instance of public criticism toward a government by an NGO. Building on previous work on NGO shaming (Murdie & Bhasin, Citation2011), we generated various keywords that would detect conflictual events, such as ‘demand’, ‘criticize’, ‘accuse’, and ‘fail’ (see Table A3 in SM for the complete list). Fourth, we relied on the established media database Lexis-Nexis to search for all NGO climate shaming activities. Since we are interested in who did what to whom, when and where, we used the Stanford Core NLP tools (Manning et al., Citation2014) to parse the documents. Specifically, we utilized conditional random fields (CRF) based Named Entity Recognizer (NER) and Basic Dependency Parsing to extract the shaming events. For example, consider this typical shaming event in our dataset: ‘Greenpeace sharply criticized China for unveiling ambitious plans to construct 50 coal gasification plants’.Footnote6 Given this sentence, NER identifies ‘Greenpeace’ as type of organization, and ‘China’, as type of target country. With our method, each document is considered as a distinct event in which an NGO identifies (names) and criticizes (shames) a specific state.

While we acknowledge that there could be more than one shaming event in a document, our assumption is reasonable as NGOs usually single out one country as the main subject in a given statement or report. In contrast to existing environmental NGO shaming datasets (Murdie & Urpelainen, Citation2015), our data specifically captures climate-related issues, and, instead of relying on Reuters Global News Data, we used multiple international media sources in the Lexis-Nexis media database. Moreover, existing environmental shaming data rely on the title and lead sentence of Reuters newswire. To save space and attract attention, headlines and lead sentences are often extremely short and miss important elements of shaming event data. Consequently, it is sometimes difficult to capture shaming events properly. For our project, we analyzed entire articles to extract climate shaming events.

One problem with shaming data is that it is likely to suffer from Western reporting bias due to the source material. In our statistical models, we utilize various strategies to account for such bias (see robustness checks).

3.2 The dependent variable and initial descriptive statistics

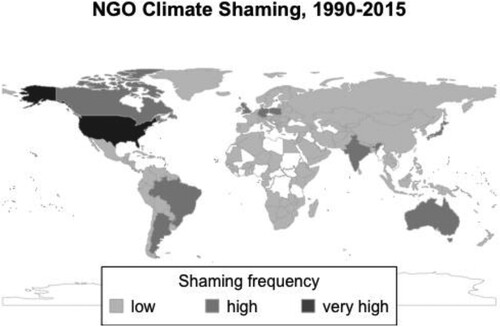

Our final NGO climate shaming dataset contains a total of 12,947 shaming events, directed at 176 countries during the period 1990-2015.Footnote7 Thus, our dependent variable, NGO climate shaming, is a count variable with country-year as the unit of analysis. shows that the most frequently shamed countries are either large or wealthy. These countries are also characterized by high CO2 emissions, in total or per capita. In our dataset, some countries, such as Antigua and Barbuda, Cape Verde, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Liberia, Tanzania, Timor-Leste, and Vietnam, have no climate shaming events for the entire study period. One of the lowest CO2 emitting regions – the African region – is also the least shamed region in our data.

The top 10 most criticized countries in our sample are: U.S., Australia, Poland, Brazil, Argentina, Germany, India, Canada, and United Kingdom (see ). The U.S. is by far the most shamed country in our data, with an average of 1,152 shaming events during the study-period. Other countries included in , are associated with, on average, between 400 and 600 shaming events during the whole period. China is the 15th most criticized country, with around 275 shaming events per year, on average, while Russia is the 20th most criticized country, with 148 shaming events annually, on average. Among the top least shamed countries, we find countries such as Tonga, Mauritania, and Panama, all receiving an average number of shaming events around 1. These countries are characterized by comparatively low CO2 emissions.

Table 1. The top 10 most and least shamed.

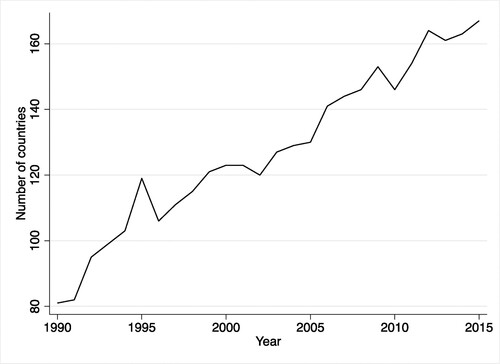

shows that the annual number of countries shamed by environmental NGOs has more than doubled since 1990. This trend can be explained by the expansion of environmental NGOs and an increased focus on climate-related issues (Berny & Rootes, Citation2018, p. 949, 963). The sharp rise in climate shaming events in 1995, for instance, coincides with the first United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) First Conference of the Parties (COP1) meeting in Berlin, Germany.

Out of a total of 2295 environmental NGOs identified in the YBIO database, 640 have been engaged in climate shaming activities. The most active environmental NGOs in our dataset are: Greenpeace (1033 shaming events), followed by more climate-oriented NGOs like Climate Action (763), Responding to Climate Change (RTCC), Climate Action Network (328) and 350.org (273). Taken together, these top five environmental NGOs – measured by number of shaming events undertaken during the period 1990–2015 – represent around 25 percent of all climate shaming events in our data.

3.3 The independent variables

We use several independent variables to test our hypotheses. In line with our theoretical framework, climate frontrunners and laggards are defined in terms of their international and domestic climate credentials. To capture international climate commitments, we include the variable International Climate Agreements (ICAs), which captures the number of ICAs that a country has committed to (Mitchell, Citation2020; Mitchell, Citation2020).Footnote8 Because ICAs do not represent the only way for countries to make climate commitments, we also focus on other climate forums (Keohane & Victor, Citation2011). For this purpose, we also include a variable capturing countries’ membership in global climate institutions (Rowan Sam, Citation2021). There are over 60 non-UN international climate institutions that states are members of and in which they participate in discussions to address climate change.Footnote9 In contrast to UN-led climate treaties (e.g. ICAs), climate institutions have fewer members, and do not create legally binding commitments but rather adopt a soft approach (Hale & Roger, Citation2014). Taken together, these two variables allow us to specifically explore how governments’ climate commitments and participation in climate institutions may influence NGOs’ decisions to target governments for climate shaming.

At the national level, we focus on two climate-related factors that might attract the attention of environmental NGOs. First, to account for national climate legislation, we rely on the Grantham Institute on Climate Change and the Environment (GRI) data on climate laws in over 170 countries (GRI, Citation2020). This variable captures the number of climate laws introduced by a government. The GRI dataset includes climate regulations, laws and executive actions but does not measure the stringency of climate laws. Though we can assume that these climate laws may vary in terms of stringency and ambition, they do represent legislative actions by governments that are likely to be noted by environmental NGOs. Second, we use per capita CO2 emissions from the World Development Indicators (WDI, Citation2020), which is a standard emissions measurement. However, we note that CO2 emissions often reflect the economic power and development level of countries, and that countries have weak control over national emissions in the short term, as these are tied to macroeconomic conditions (Victor, Citation2011). Despite this, the CO2 emissions are at the center of the climate change debate and constitute a visible indicator of countries’ climate performance.

We also add a set of additional variables that may influence NGO climate shaming. Studies have shown that more democratic countries are less likely to be targeted by NGOs (Murdie & Urpelainen, Citation2015). We thus control for regime type in our analysis, using V-Dem’s Liberal democracy index (Coppedge et al., Citation2022). Following previous studies, we control for two main economic variables: GDP per capita and trade as a percentage of GDP (WDI, Citation2020). This is because previous studies have found that NGOs are likely to target rich countries and countries that are more open to trade (Franklin, Citation2008). Lastly, we also account for the population size of countries as populous countries usually attract the attention of NGOs (Ron et al., Citation2005). Summary statistics of all variables are presented in Table A4 in SM.

3.4 Model

Given the nature of our dependent variable, we need to consider statistical models dealing with count data. Poisson regression is the traditional model for estimating outcomes that are measured as counts. But because our data is also over-dispersed – with a variance much larger than the mean – the standard Poisson models will generate biased standard errors. Therefore, we opt for negative binomial regressions that can model overdispersion. In the robustness checks section, we also employ other models. Moreover, we include a lagged dependent variable (LDV) to account for possible autocorrelation.Footnote10 In addition, we employ robust standard errors clustered on countries and include yearly fixed effects to account for temporal changes across our study period. In some models, we also utilize region fixed effects to control for variation in shaming, determined by characteristics that vary across regions but are constant over time. All independent variables are lagged by one year to control for possible simultaneity bias.

4. Findings

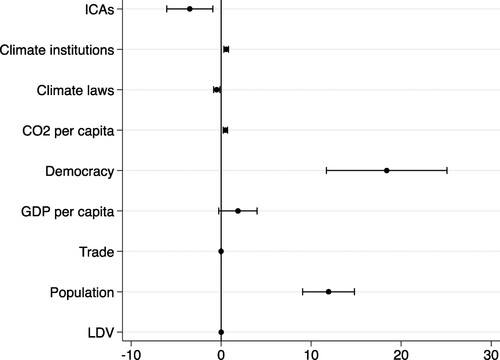

We present our main analysis in . Overall, our empirical results lend more support to hypothesis 2 (shaming climate laggards), while hypothesis 1 (shaming climate frontrunners) receives weak support. At the international level, NGOs are less likely to target governments that have committed to ICAs.

Table 2. Negative binomial regression analysis.

More precisely, a one-unit change in ICAs decreases the expected number of climate shaming by 36 percent (based on Model 4 in ). A one unit increase in climate laws decreases climate shaming by 7 percent. This suggests that environmental NGOs focus their scrutiny on climate laggards so as to exhort them to take action (H2). However, climate frontrunners are not treated entirely leniently by NGOs. Governments’ involvement in non-UN climate institutions increases the expected number of NGO climate shaming by 7.3 percent. This indicates that environmental NGOs tend to publicly criticize those governments that engage in weak climate action as these non-UN climate institutions are characterized by legally non-binding commitments and a lack of robust monitoring procedures.

The marginal effects on the predicted number of climate shaming events, in , reinforce the main findings in . The results also reveal other sources of influence on NGO climate shaming. Wealth, CO2 emissions per capita and population size are important determinants of NGO shaming. The predicted number of climate shaming events is around 12 for populous countries, 0.46 for large emitters and about 7.2 for richer countries. With respect to size and wealth, the results reinforce the findings of previous studies on corporate climate shaming by social movements (Bartley & Child, Citation2014; Bloomfield, Citation2014) and on government shaming by intergovernmental organizations (Koliev & Lebovic, Citation2018).

Regime type, or the level of democracy, has a more substantial impact on climate shaming than other factors. This research shows that, in general, environmental NGOs are likely to target democratic over non-democratic countries, which contradicts the findings of previous studies (Murdie & Urpelainen, Citation2015; Ron et al., Citation2005). One viable explanation for this is that environmental NGOs strategically shame those countries that are likely to be more responsive to international criticism (Keck & Sikkink, Citation1998, pp. 28–29).

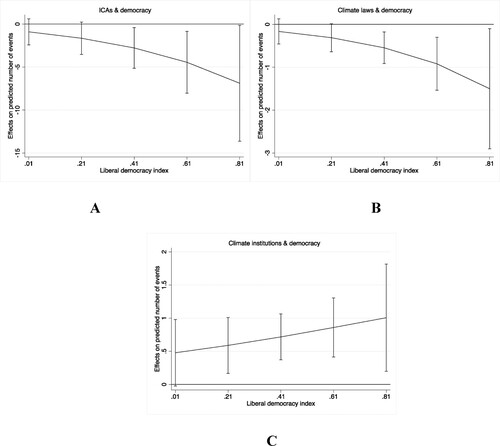

The relationship between regime type and NGO shaming, however, deserves additional analysis because of the expectations in the literature that democratic governments are more responsive to climate shaming than non-democracies, especially if they have made public commitments. We thus perform additional analyses interacting countries’ international and domestic climate actions with their regime type, which allows us to test whether these factors exert similar effects in democracies and non-democracies.

(A,B) show that NGOs are less likely to shame democratic states that sign more ICAs and pass climate laws. That is, environmental NGOs do not target countries only because of their restricted political environment for domestic activism (Murdie & Urpelainen, Citation2015), but rather in combination with their commitments to international and national climate action. NGOs may, for instance, expect less compliance with international commitments by non-democratic governments because they are less likely to be held accountable to their promises by domestic actors – compared to democratic governments. However, (C) shows that democratic states are more scrutinized and to a greater extent held accountable for their involvement and participation in non-UN climate institutions than non-democratic countries are. We speculate that democratic governments’ ambitious climate pledges within these non-binding climate institutions, coupled with the lack of monitoring and evaluation processes incorporated into these ‘soft’ agreements, attract the attention of environmental NGOs.

Figure 4. A–C. Marginal Effects of ICAs (A), Climate laws (B), Climate membership (C) as countries become more democratic.

4.1 Robustness checks

We perform multiple robustness tests and report the full results in SM (Tables A5 and A6). Overall, the tests suggest that our main results are robust and statistically significant across different specifications.

More specifically, we perform five different robustness tests. First, we re-estimate our analysis including only a developing country sample (Model 1, in Table A5). Second, we exclude the US from the whole sample as it is a clear outlier (M2, Table A5). The results from these two models indicate that our findings are robust even when we exclude rich countries and the US. Third, we restrict the time period of the analysis to 2000–2015 (M3, Table A5). We obtain similar results, suggesting that our results are not sensitive to the specific study period. Fourth, to determine whether there is a non-linear (i.e. curvilinear) relationship between the number of signed ICAs and NGO climate shaming, we add a squared term of ICAs – the results suggest no evidence of curvilinearity (M4, Table A5). Moreover, we include a variable measuring the percentage of signed ICAs among those open for signature – instead of the number of signed ICAs – and the findings are robust and close to identical (M5, Table A5). Fourth, we estimate our models using Zero-inflated binomial models, which allows us to test whether the excess zeros are generated by different mechanism than count values. Effectively, the first process is a count model predicting the number of shaming events, and the second process is a logit model (inflation equation) predicting the excess of zeros. We include various inflation factors, such as population, CO2 emissions (M1, Table A6) and the number of International Environmental Agreements that a country has committed to (M2, Table A6). Our results remain robust. Finally, we run conditional mean Poisson (fixed-effects) models as a conservative test. Though standard Poisson models assume equality between the mean and the variance, fixed-effects Poisson models can produce consistently estimated coefficients (Guimarães, Citation2008). The results show substantively similar effects though the variable climate laws is not significant in this alternative model (M3, Table A6).

5. Conclusions

At a general level, our study identifies five key insights. First, NGOs are likely to target climate laggards so as to prompt them to take action. Second, climate laws and international climate treaties are central for our understanding of how environmental NGOs target governments. Third, NGO climate shaming is not only about whether but also about how governments participate in global climate governance. Fourth, and relatedly, membership in climate institutions with non-binding commitments attracts NGO climate shaming. Finally, governments that commit to international agreements and introduce national climate laws may do so in order to avoid negative publicity by NGOs, without the intention to comply. Future studies could show, for instance, to what extent governments commit to climate norms in order to escape reputational costs.

As the first systematic study of NGO climate shaming activities, our study also offers more specific implications. While we find that climate frontrunners are shamed less than laggards because they make more commitments to ICAs and pass more laws – our analysis also shows that frontrunners are more scrutinized by NGOs when they engage in non-UN climate institutions – e.g. when engaging in weak climate action. This implies that so called ‘low-cost institutions’ (Abbott & Faude, Citation2021) do not escape the attention of NGOs. This also emphasizes the importance of paying attention to the type of commitments (Cole, Citation2009) that governments make when examining how climate shaming is occurring and what is driving it. This is potentially good news, indicating that empty climate pledges incur costs. Examining such targeting practices in other areas, such as corporate shaming (Bartley & Child, Citation2014), is important as criticism of governments or corporations that engage in weak commitments, or selective disclosure in the case of corporations (Marquis et al., Citation2016), raises the reputational costs and can prompt changes in policy behavior (Franklin, Citation2008; Jacquet & Jamieson, Citation2016; Taebi & Safari, Citation2017).

In addition, our results suggest that environmental NGOs substitute for the lack of domestic pressure by shaming governments that commit to international and national climate action and have restricted environments for domestic activism. Such behavior reveals that environmental NGOs target non-democratic countries based on the concept of leverage politics (Hendrix & Wong, Citation2014, p. 31), that is, when governments make public commitments to climate action.

We also raise caution with regard to some issues. First, governments that sign ICAs and introduce national climate laws can to some extent escape NGO climate shaming. This is potentially problematic if governments decide to commit to ICAs without the intention to comply, but to deflect potential international climate shaming or boost their short-term reputation. As stated by the secretary-general of the UN: ‘Signing the declaration is the easy part’.Footnote11 At the same time, signing ICAs is an act that invites reputational costs if governments choose not to comply with them. Second, and relatedly, although some studies have shown that national climate laws can reduce CO2 emissions (UNEP, Citation2019), our findings might be bad news for those who want to put more pressure on climate frontrunners, especially democratic governments. A more positive implication is that institutions and actors in democratic countries still can act and hold their governments to account. In this context, the finding that NGOs focus their criticism on governments that lack climate laws is good news. Finally, caution should also be raised regarding conclusions about the potential reasons behind the targeting patterns revealed in quantitative studies. Regression models cannot tell us about the specific motives or considerations of NGOs. Here, qualitative studies can contribute by unpacking various dynamics, for example why environmental NGOs target democracies that engage in weak climate action. While such an approach is needed, it is also worth noting that previous studies of NGOs have revealed that NGO staff are often unaware of the targeting practices and that NGO strategies often are not explicit (Cooley & Ron, Citation2002; Tallberg et al., Citation2018). Still, a variety of methods can be useful to enhance the understanding of the determinants of shaming, including experiments, observational and interview-based studies.

Our study generates several potential new pathways for future studies. First, an important task for future studies is to examine if and under what conditions NGO climate shaming can enhance governments’ climate change actions. Second, researchers could assess if climate shaming leads to ambitious and stringent climate laws or to weak laws, allowing some governments to avoid reputational costs. Finally, another important task for future research is to further improve the data on shaming events. One possible way forward here is to distinguish between more harsh and more lenient types of shaming events as governments may respond differently depending on the severity of shaming campaigns.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (36.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This includes United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Regional Convention on Climate Change, and other agreements, protocols and amendments under the UNFCCC. For detailed information see Mitchell (Citation2020).

2 https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/feb/03/court-convicts-french-state-for-failure-to-address-climate-crisis (October 19, 2021); https://www.euronews.com/2021/02/09/over-100-ngos-criticise-france-s-lack-of-ambition-over-draft-climate-bill (October 19, 2021)

3 https://www.cleanenergywire.org/news/landmark-ruling-german-top-court-key-climate-legislation-falls-short (October 19, 2021)

4 https://climatenetwork.org/cop26/fossil-of-the-day-at-cop26/ (June 22, 2022).

5 Our original climate shaming data covers the period 1990–2020. However, we restrict our analysis to the period 1990–2015 because we lack data covering recent years for some of our main explanatory variables.

6 https://www.heartland.org/news-opinion/news/greenpeace-blasts-chinas-coal-plans (October 21, 2021)

7 Our original climate shaming data covers the period 1990-2020. However, we restrict our analysis to the 1990–2015 period because we lack data, for recent years, for some of ours main explanatory variables.

8 For detailed information, see the codebook of Global climate governance dataset (Rowan Sam, Citation2021).

9 For example: Clean Energy Ministerial, Climate Vulnerable Forum, and the Green Climate Fund.

10 The results remain almost identical without the inclusion of the LDV.

11 The UN climate process is designed to fail. Financial Times. Accessed: 2021/11/19.

References

- Abbott, K., & Faude, B. (2021). Choosing low-cost institutions in global governance. International Theory, 13(3), 397–426. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752971920000202

- Allan, J. I. (2018). Seeking entry: Discursive hooks and NGOs in global climate politics. Global Policy, 9(4), 560–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12586

- Bartley, T., & Child, C. (2014). Shaming the corporation. American Sociological Review, 79(4), 653–667. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122414540653

- Berny, N., & Rootes, C. (2018). Environmental NGOs at a crossroads? Environmental Politics, 27(6), 947–972. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1536293

- Betsill, M. M., & Corell, E. (2001). NGO influence in international environmental negotiations: A framework for analysis. Global Environmental Politics, 1(4), 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1162/152638001317146372

- Bloomfield, M. J. (2014). Shame campaigns and environmental justice: corporate shaming as activist strategy. Environmental Politics, 23(2), 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2013.821824

- Cole, W. M. (2009). Hard and soft commitments to human rights treaties, 1966-2000. Sociological Forum, 24(3), 563–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1573-7861.2009.01120.x

- Cooley, A., & Ron, J. (2002). The NGO scramble: Organizational insecurity and the political economy of transnational action. International Security, 27(1), 5–39. https://doi.org/10.1162/016228802320231217

- Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Altman, D., … Ziblat, D. (2022). V-dem Codebook v12.

- Falkner, R. (2016). The Paris Agreement and the new logic of international climate politics. International Affairs, 92(5), 1107–1125. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12708

- Franklin, J. C. (2008). Shame on You: The impact of human rights criticism on political repression in Latin America. International Studies Quarterly, 52(1), 187–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00496.x

- GRI. (2020). Climate Change Laws of the World. Grantham Reseach Insitute on Climate Change and the Environment.

- Guimarães, P. (2008). The fixed effects negative binomial model revisited. Economics Letters, 99(1), 63–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2007.05.030

- Hadden, J., & Bush, S. S. (2021). What’s different about the environment? Environmental INGOs in comparative perspective. Environmental Politics, 30(1), 202–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2020.1799643

- Hale, T., & Roger, C. (2014). Orchestration and transnational climate governance. The Review of International Organizations, 9(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-013-9174-0

- Hendrix, C. S., & Wong, W. H. (2014). Knowing your audience: How the structure of international relations and organizational choices affect amnesty international’s advocacy. The Review of International Organizations, 9(1), 29–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-013-9175-z

- Jacquet, J., & Jamieson, D. (2016). Soft but significant power in the Paris Agreement. Nature Climate Change, 6(7), 643–646. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3006

- Keck, M., & Sikkink, K. (1998). Activists beyond borders: Advocacy networks in international politics. Cornell University Press.

- Keohane, R., & Victor, D. (2011). The regime complex for climate change. Perspectives on Politics, 9(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592710004068

- Koliev, F. (2020). Shaming and democracy: Explaining inter-state shaming in international organizations. International Political Science Review, 41(4), 538–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512119858660

- Koliev, F. (2021). Where help Is needed most? Explaining reporting strategies of the international trade union confederation. Political Studies, 69(2), 390–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321720903244

- Koliev, F., & Lebovic, J. H. (2018). Selecting for shame: The monitoring of workers’ rights by the International Labour Organization, 1989 to 2011. International Studies Quarterly, 62(2), 437–452. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqy005

- Lebovic, J. H., & Voeten, E. (2009). The cost of shame: International organizations and foreign Aid in the punishing of human rights violators. Journal of Peace Research, 46(1), 79–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343308098405

- Manning, C., Surdeanu, M., Bauer, J., Finkel, J., Bethard, S., & McClosky, D. (2014). The stanford corenlp natural language processing toolkit, in ‘Proceedings of 52nd annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics: system demonstrations’, pp. 55–60.

- Marquis, C., Toffel, M. W., & Zhou, Y. (2016). Scrutiny, norms, and selective disclosure: A global study of greenwashing. Organization Science, 27(2), 483–504. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2015.1039

- Meernik, J., Aloisi, R., Sowell, M., & Nichols, A. (2012). The impact of human rights organizations on naming and shaming campaigns. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 56(2), 233–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002711431417

- Mitchell, R. B. (2020). IEA Membership Count Dataset from the International Environmental Agreements Database Project (Version 20200214). Eugene: IEADB Project. Dataset generated on: 14 February 2020.

- Murdie, A., & Bhasin, T. (2011). Aiding and abetting: Human rights INGOs and domestic protest. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 55(2), 163–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002710374715

- Murdie, A., & Urpelainen, J. (2015). Why pick on Us? Environmental INGOs and state shaming as a strategic substitute. Political Studies, 63(2), 353–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12101

- Pacheco-Vega, R., & Murdie, A. (2021). When do environmental NGOs work? A test of the conditional effectiveness of environmental advocacy. Environmental Politics, 30(1), 180–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2020.1785261

- Prakash, A., & Gugerty, M. K. (2010). Advocacy organizations and collective action. Cambridge University Press.

- Raustiala, K. (1997). States, NGOs, and international environmental institutions. International Studies Quarterly, 41(4), 719–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2478.00064

- Ron, J., Ramos, H., & Rodgers, K. (2005). Transnational information politics: NGO human rights reporting, 1986-2000. International Studies Quarterly, 49(3), 557–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2005.00377.x

- Rowan Sam, S. (2021). Does institutional proliferation undermine cooperation? Theory and evidence from climate change. International Studies Quarterly, 65(2), 461–475. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqaa092

- Spektor, M., Mignozzetti, U., & Fasolin, G. N. (2022). Nationalist backlash against foreign climate shaming. Global Environmental Politics, 22(1), 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00644

- Stroup, S. S., & Wong, W. H. (2017). The authority trap: Strategic choices of international NGOs. Cornell University Press.

- Taebi, B., & Safari, A. (2017). On effectiveness and legitimacy of ‘shaming’ as a strategy for combatting climate change. Science and Engineering Ethics, 23(5), 1289–1306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9909-z

- Tallberg, J., Dellmuth, L., Agné, H., & Duit, A. (2018). Ngo influence in international organizations: Information, access and exchange. British Journal of Political Science, 48(1), 213–238. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712341500037X

- The World Bank Group and World Development Indicators. WDI. (2020). World development indicators. The World Bank Group.

- Tingley, D., & Tomz, M. (2022). The effects of naming and shaming on public support for compliance with international agreements: An experimental analysis of the Paris agreement. International Organization, 76(2), 445–468. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818321000394

- UNEP. (2019). Enviromental Rule of Law. First Global Report. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, Kenya.

- van Asselt, H. (2016). The role of Non-state actors in reviewing ambition, implementation, and compliance under the Paris agreement. Climate Law, 6(1-2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1163/18786561-00601006

- Victor, D. (2011). Global warming gridlock: Creating more effective strategies for protecting the planet. Cambridge University Press.

- Wapner, P. (1996). Environmental activism and world civic politics. State University, New York Press.