ABSTRACT

The People’s Republic of China (China) is a key country for achieving the global 1.5°C climate target. Since 2006, it has become the world's largest emitter of greenhouse gases (GHG). Despite this increased relevance of China for effective climate governance, we lack a holistic understanding of China’s factual role in climate governance, both domestically and on the international stage. To advance our knowledge of China’s role and relevance in climate governance, we perform a systematic literature review in the field of climate governance between 2009 and 2019. We identify four main research themes that structure the scholarly debate on China's climate governance, distilled from a review of 250 articles. These are: a) the motivations behind China’s climate action; b) available policy instruments for governing climate change; c) the role of non-state actors; and d) comparative analysis between China and other countries. We found that the current literature focuses predominantly on how to govern climate change at specific levels through a range of case studies. What is missing is an assessment of the coherence, or lack thereof, among different policy levels and policy instruments, as well as a detailed analysis of the role and relevance of non-state actors in China’s climate governance. We encourage scholars to factor in these gaps when developing future research.

Key policy insights

The main motivations behind China’s climate action are domestic considerations, in particular, the need to decouple economic growth from emissions.

In general, China has addressed climate change by leveraging existing institutional arrangements. These institutions are instruments of public policy and remain the primary mechanism for managing climate mitigation and adaptation in China.

The key to implementing climate policy in China lies in local governments. How local governments perceive, behave, and balance different priorities affects the final outcome.

Non-state actors do have opportunities to participate in climate governance in China. However, participation is limited to actors with economic or technological expertise, such as large domestic firms, research institutes, international development banks, and transnational companies.

Countries adopt similar climate policy instruments despite their various institutional composition.

1. Introduction

Reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to mitigate climate change requires immediate and drastic action from all nations, but especially the world’s major emitters. The People’s Republic of China (in short: China) is one of the most important actors in global climate governance due to the size of its economy and the resulting emissions (Zhang & Orbie, Citation2019). As of 2020, China tops the list of global polluters with 10,065 million tons of CO2 released. As a consequence, scholars of global environmental governance have started to scrutinize China’s climate governance at different levels, often using a case study approach (Chen et al., Citation2017; Chu & Schroeder, Citation2010; Li et al., Citation2017; Li et al., Citation2019; Urban et al., Citation2018; Westman & Broto, Citation2018; Westman & Broto, Citation2019). What is missing, however, is a more aggregated and systematic overview of the state of knowledge on climate change governance in and by China.

Consequently, we explore the state of knowledge on Chinese climate governance since the Conference of Parties (COP) 15 in Copenhagen in 2009. We employ a broad understanding of climate governance, focusing on the multi-dimensional and multi-actor levels of governance related to China. Specifically, we are interested in the process through which climate governance takes place; by whom climate governance is being undertaken; and why and with what implications the governing of climate change is taking particular forms (Bulkeley and Newell, Citation2010). Through a systematic review of 250 articles on China’s climate governance, published in English language peer-reviewed journals between 2009 and 2019, we address the questions: What is the state of China’s current climate governance (both as a domestic and an international policy arena), and what do we know about coherence/incoherence of existing governance approaches across various levels of governance and policy instruments?

This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we elaborate on why a systematic review of the literature on China’s climate governance is relevant to today’s policy debate. Section 3 presents our methodology for the systematic literature review. Section 4 summarizes the results from our qualitative analysis, where we identify four broad areas of research and associated findings: a) the motivations behind China’s climate action; b) available policy instruments for governing climate change; c) the role of non-state actors; and d) comparative analyses between China and other countries. Section 5 concludes by unpacking and reflecting on key findings from the four research themes and provides suggestions for future research.

2. The increased relevance of China in global climate governance

China has been the world’s largest carbon dioxide emitter since 2006 and is responsible for a growing share of future global emissions that account for roughly one-third of global CO2 emissions in 2022 (Chiu, Citation2017; IEA, Citation2021b).It is depicted as ‘the best and worst hope for climate mitigation’ as China is also the world’s largest producer of wind and solar energy (Chiu, Citation2017; IEA, Citation2021b; Niiler, Citation2018). The past decade has witnessed numerous milestones and key turning points in terms of China’s climate governance, both at the global and domestic levels, which will dramatically affect the overall performance of global climate governance.

Internationally, since the Copenhagen Climate Summit in 2009, China has become an increasingly proactive player in the negotiations of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The US–China climate pledge in 2014 is commonly highlighted as a game-changer, paving the way for the subsequent 2015 Paris Agreement. In 2017, China positioned itself as a positive counterbalance to the withdrawal of the US government from the Paris Agreement (Eckersley, Citation2020; House, Citation2014; TheWhiteHouse, Citation2014). During the same ten-year period, China has become the largest wind energy provider and leading installer of solar photovoltaics (Kostka & Zhang, Citation2018). In September 2020, China pledged to become carbon neutral in 2060 and confirmed that it will strive to peak its carbon emissions before 2030 (ChinaDaily, Citation2020). According to a 2021 report from the International Energy Agency (IEA), China’s existing policies put its CO2 emissions on track to peak by even the mid-2020s (IEA, Citation2021a). On the surface, at least, it would seem that China is changing its position at the international level from a recalcitrant country in the negotiations to a proactive and ambitious player.

Similar positive developments can be observed at the domestic level. In 2015, China released its National Master Plan to realize the core narrative of ‘ecological civilization (sheng tai wen ming 生态文明),’ the overall ideological framework for the country’s environmental policy, laws, and education. This narrative interprets the Party’s long-term vision of a more sustainable China, which was both added to the Communist Party of China’s (CPC) Constitution and the Chinese Constitution, respectively, in 2012 and 2018 and is seen as the most important political signal in the environmental area (Geall & Ely, Citation2018; Hansen et al., Citation2018; Schreurs, Citation2017; TheStateCouncil, Citation2015; XinhuaNet, Citation2018). Recent institutional reforms are consistent with the Master Plan. For example, in 2018, China reshaped its ministries. The newly established Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) took full responsibility for climate change issues from the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the most powerful ministry responsible for making national economic and social development plans. The central government’s choice to move the responsibility of climate change issues from the NDRC to the newly established MEE can be read as a sign of the increased importance of environmental issues (Li, Citation2018). In 2009, the Chinese media espoused the view that climate change was a conspiracy led by developed countries designed to inhibit the economic growth of developing countries. There has since been a dramatic shift in such narratives to one that now calls for the widespread adoption/incorporation of a ‘low carbon’ development strategy (Li, Citation2019).

More than ten years after the Copenhagen climate summit in 2009, it is time to take stock of the knowledge generated from peer-reviewed research. This literature review covers the period from 2009 to 2019 to capture changes in Chinese climate governance. Based on current knowledge as reflected in the academic literature, what robust findings have emerged, and what research questions remain to be answered in the future? To answer these questions, we now move to our methodology.

3. Methodology

The systematic literature review consists of three steps. First, we identify potentially relevant articles using search strings in combination with relevant disciplines in Web of Science. Second, we screen the articles from step 1 to determine which ones fit our purpose and definitions. Third, we read and code articles from step 2, using inductively generated keywords, and then we report on the key research findings in the period 2009–2019 along four broad themes. The methodology is explained in more detail below and further elaborated upon in the results section.

The first challenge is to identify articles that focus on Chinese climate policy and governance within the relevant time-period, 2009 to 2019. To arrive at potentially relevant articles, we entered two different search strings into the advanced search function on Web of Science. The reason for using two search strings was because a broad search string including publications from all academic disciplines rendered an unmanageable number of results of some 7000 articles. Instead, we first restrict the key words and, second, the academic disciplines. The first search string was designed to be narrow in terms of key words and broad in disciplines. The time-period was set to 01-01-2009 to 31-12-2019, and the language to ‘English’. The search strings, disciplines, and number of results are presented in below.

Table 1. Overview of the first search string data collection process, including numbers of publications per search step.

The search string was selected using combinations of words related to climate change policy and governance in China, leading to some 129 articles that were subsequently manually analyzed for relevance, resulting in 99 articles. The references of those 99 articles were scanned for possible additional articles that fit the search criteria, resulting in 25 additional articles. The first search string and subsequent manual assessment consequently yielded 124 relevant articles on Chinese climate policy and governance for the period 2009–2019.

Second, we cast a wider net in terms of search string but narrowed the list of relevant disciplines to identify articles that discuss climate policy and governance in China and merge those with the results from step 1 to exclude duplicates. The results of the second search string are presented in below.

Table 2. Overview of the second search string data collection process, including numbers of publications per search step.

This second search generates 516 articles that were subsequently merged with the articles from step 1 after screening for relevance and duplicates and manually checking for additional references that meet our criteria, generating 126 new articles. In total, the final number of articles is 250 (124 from the first search string plus 126 from the second search string).

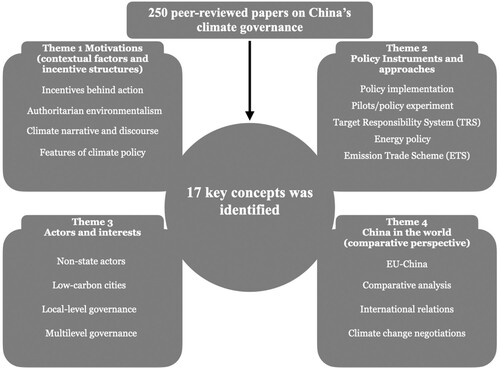

Third, the 250 articles were read, coded, and subsequently assigned to one or more out of four different themes based on 17 key words. The key words were identified via an inductive coding process using a random sample of 25 articles. Subsequently, the key words were applied to all articles in the sample in order to analyze their contribution to the literature. To report the main findings, the key words were clustered into themes by the research team, demonstrates the construction of heuristic themes from key words. The four themes used to report our findings are: Motivations (articles discussing why China would act on climate change); Instruments (articles discussing what instruments China uses to mitigate climate change); Actors (articles discussing the key actors in Chinese climate governance); and China and the world (articles discussing Chinese climate governance in relation to other countries and/or the international arena). Note that multiple themes per article are possible. The main research findings per theme are further elaborated in the results section (4).

4. What do we know about Chinese climate governance in the period 2009–2019?

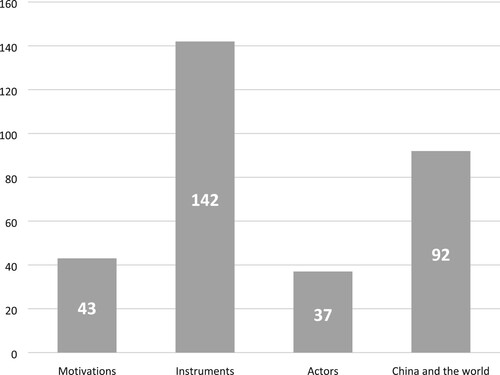

When analyzing the articles for their contribution to our state of knowledge, four main themes emerge (based on our inductive identification of key words). First, papers that address the motivations and interests behind China’s climate change action, including domestic considerations, climate vulnerability, international pressure, and elite interests, to name a few. Second, papers that discuss specific climate policy instruments applied in the Chinese context. Third, articles that investigate the changing landscape of China's climate governance, particularly regarding the increasing visibility of non-state actors in climate governance. And fourth, comparative research papers on China and other countries/regions with regard to governing climate change. Most of the reviewed research falls into the theme of policy instruments, in particular, dealing with questions around emission trading systems (ETS) (142 articles), followed by the (comparative) analysis of China at the international level (92 articles); then comes motivations and incentives behind China’s climate action (43 articles), and lastly key actors (37 articles). provides an overview of the number of articles reviewed, organized by theme. Below we discuss results for each theme in more detail, reporting on the key scientific findings of 250 articles reviewed here, all published in the period 2009–2019.

4.1. Why act on climate change? Motivations behind China’s climate change actions

The first theme identified engages with the ‘why?’ question of climate governance, analyzing the intentions underpinning China’s seemingly more ambitious climate policies, both at home and abroad. Two explanations stand out. First, domestic pressures, ranging from economic transition to environmental considerations. The climate change agenda fits into the broader ongoing transition of China’s development model from a ‘develop at all costs’ model to a more sustainable economic development. Climate change policy is identified as a new engine in the next phase of prosperity and, at the same time, aligns with the need to ease the pressure from hazardous climate risks the country has faced (Beeson, Citation2018; Chmutina et al., Citation2012; Lo, Citation2015; Lo, Citation2015; Lo & Howes, Citation2015; Zhang & Orbie, Citation2019). Economic growth is identified as the core motivation for action on climate change, and the market power storyline creates a positive linkage between national development and carbon markets as it creates new sites for profitable investment and economic growth (Green & Stern, Citation2016; Kwon & Hanlon, Citation2016; Lo & Howes, Citation2015). As Hilton and Kerr argue (Citation2017), China has stepped into the economic ‘new normal’, which requires slowing down development speed, upgrading the domestic industrial structure, and supporting more sustainable and innovation-driven development patterns. China views low-carbon technologies as the future ‘sunrise’ industry, as there is an opportunity to catch up and establish its dominance as an innovator, manufacturer, and exporter (Hilton, Citation2016; Shen & Xie, Citation2018). Shen and Xie (Citation2018) state that new investment in climate projects such as wind or solar farms also provides strong incentives for subnational governments. Investments in low-carbon technologies usually come with GDP growth, employment, and tax income, key indicators for the communist party cadre’s performance evaluation and promotion. In this sense, the central and local interests are in-sync. In addition, China is one of the most vulnerable countries to the adverse impacts of climate change, from agriculture, water resources, ecosystem, coastal and offshore ecosystems, and suffers severely from extreme climate events. China is also facing unprecedented environmental problems due to its rapid economic growth and urbanization over the past four decades. The close interlinkages between climate change and air pollution and potential synergies by ‘killing two birds with one stone’ are also identified as the key motivation (Jiang et al., Citation2013; Men, Citation2014; Schreurs, Citation2017; Wang et al., Citation2018). As Chinese President Xi Jinping has emphasized several times on different occasions, ‘addressing climate change should not be done at other’s requests but on our own initiative’ (XinhuaNet, Citation2021).

The second explanation for China’s more proactive stance on climate change identifies external pressures stemming from the international community. In more detail, three motivations can be discerned in the literature. First, China has emerged as the largest global emitter of GHGs since the first decade of the 2000s, making it difficult to shift the blame to others (Wang et al., Citation2018). Second, as Zhang and Orbie (Citation2019) observe, China has gradually realized the tactical benefits of taking a more ambitious position, utilizing its institutional and discursive power in setting agendas, forming decisions, creating and improving rules, interpreting, and applying regulations. And third, the increasing politicization of discourse on China and the emergence of a ‘new Cold War’ narrative between the US and China puts great pressure on China’s diplomacy. Therefore, it is interested in securing international partners (ChinaDialogue, Citation2020), and climate change has emerged as a topic where China sees potential common interests with international partners and consequently seeks collaboration in the global arena.

Analysts agree that both domestic and international pressures influence China’s participation in global climate change, but as Kwon and Hanlon (Citation2016) argue, the main motivation might be to protect the Chinese Communist Party’s political legitimacy and the stability of the political system. On this account, anything that might jeopardize or harm the legitimacy of the Party will be addressed. In the case of climate governance, when combating climate change aligns with the interests of political elites in China, it increases the issue’s policy priority as the political elites make trade-offs on weighing the cost and benefit of climate action (Kostka & Zhang, Citation2018; Marks, Citation2010). However, as Li and Shapiro (Citation2020) argue, if the decisions are made mainly based on the alignment with the countries’ elites’ interests, then the interests of people outside this elite circle might be left unattended, and this, in turn, might cause inequality when the government tries to address climate change.

4.2. What policy instruments are in the climate governance toolbox?

A second theme in the literature on Chinese climate governance focuses on ‘what’ and ‘how’ questions, that is, the concrete policy instruments and approaches available for mitigation and adaptation. More than half of the papers analyzed in this article focus on identifying or evaluating policy instruments used to govern climate change in China. He (Citation2010) argues that policy instruments remain the primary pathway for managing mitigation and adaptation in China. Guan and Delman (Citation2017) state that although China is ruled under an authoritarian one-party regime, there do not seem to be ideological barriers to the choice of policy instruments. In general, as Harrison and Kostka (Citation2019) show, China has sought to address climate change by integrating mitigation and adaptation into broader incentive systems and leveraging existing institutional structures to deliver policy objectives.

Three key policy instruments emerge from our systematic literature review. The first two instruments are ‘top-down target-setting’ and ‘strategic narratives’. Scholars focus mainly on questions about how the authoritarian political system governs climate change in China and the effectiveness of associated traditional policy instruments (Li et al., Citation2016; Lo, Citation2015; Qi & Wu, Citation2013). The third instrument, the ‘market-based approach’, and primarily the newly established Emission Trading Scheme (EST), also attracts much attention. In this line of research, scholars are most interested in how market mechanisms can fit into the specific political-economic and ideological context of China (Chen et al., Citation2017; Francesch-Huidobro, Citation2012; Jiang et al., Citation2016; Lo, Citation2015; Lo, Citation2016; Lo et al., Citation2018; Lo & Francesch-Huidobro, Citation2017; Lo & Howes, Citation2013; Shen & Wang, Citation2019). We will now briefly discuss each policy instrument.

A central policy instrument adopted by the authoritarian political system is target-setting. China has relevant experience with governing through target-setting since 1949; its very foundation is setting a Five-Year-Plan (FYP) to govern China’s social and economic development. These targets were disaggregated into province-level goals, which were further broken down into local level goals (Li & Shapiro, Citation2020). Zooming in on the environmental domain, Kostka (Citation2016) states that the government monitors environmental conditions and enforces environmental standards by setting a set of quantitative goals. The primary structure of realizing the climate target in each FYP is the ‘target responsibility system’ (TRS) established in 2007 as the basic energy policy implementation mechanism. TRS marked the transition of China’s climate governance structure from a line-based to a block-based one since responsibilities are divided based on different administrative regions instead of a hierarchical political system (Kostka & Zhang, Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2016; Qi & Wu, Citation2013). The TRS is considered the most important institutional mechanism through which the central government can ‘command and control’ the local government’s climate action via the vertical transfer of targets and evaluating the extent to which the local government achieves the energy conservation target (Westman et al., Citation2019). Under the TRS, the national energy intensity reduction targets are realized through ‘responsibility contracts’, assigning energy-saving targets to lower levels of governments and major energy-consuming enterprises. The Statistics Indicators, Monitoring, and Examination (SME) system keeps track and evaluates yearly performance (Li et al., Citation2016). Thus, each level of administration and business is responsible for achieving its own mandated target.

The embedding of environmental targets in the cadre management system gives officials further incentives to implement climate policy. Chinese officials are promoted based on how they perform on a bundle of targets assigned to them from above, including the targets related to climate change (Kostka, Citation2016). Failing to meet the target would lead to inadequate end-of-term performance evaluations that directly influence local leaders’ career paths (Lo, Citation2014). In this way, the TRS, formed by a pressure-response mechanism and an information feedback system, establishes political incentives for local governments to implement climate policy (Kostka, Citation2016; Li et al., Citation2016; Ran, Citation2013). Studies on how this pressure system works when addressing climate change mainly focus on how the central government has translated the national climate mitigation targets into the domestic contexts and how local governments have perceived and behaved towards different balanced priorities to achieve those targets.

Related to the policy instrument of target-setting, a number of studies (Kostka, Citation2016; Lo, Citation2014; Ran, Citation2013) find a significant gap between policy and its implementation. For example, research finds that local governments and leaders have a huge influence on the successful implementation of a policy (Fan & Wang, Citation2016; Kostka & Hobbs, Citation2012). More specifically, local Environmental Protection Bureaus (EPBs) have gained independence in determining priorities and financing arrangements while being held to stricter performance standards, and the outcome orientation gives them a high level of flexibility and adaptability in enforcing environmental regulation (Li & Shapiro, Citation2020; Westman & Broto, Citation2018). Four main factors are related to the implementation gap at the local level. First, local leaders’ lack of political interest in implementing climate policy as the National Cadre Evaluation System (the major institutional mechanism for distributing political incentives from Central to local officials who implement Beijing’s policies) continues to place heavier emphasis on economic growth than on environmental protection (Francesch-Huidobro, Citation2012; Francesch-Huidobro & Mai, Citation2012; Lo, Citation2014; Marks, Citation2010; Ran, Citation2013; Wu, Citation2013; Wu et al., Citation2013). Second, Lo (Citation2015) reports that the cadre evaluation system has shortcomings as the scoring system’s criteria are vague and symbolic, lacking certainty, which can be easily achieved by the wording. The energy intensity index is an indirect statistical index and makes it difficult to observe by the central government, and the enterprise-level contribution is also hard to measure (Kostka, Citation2016; Li et al., Citation2014; Li et al., Citation2016; Lo, Citation2014). Limited capacity and rampant data manipulation have turned the compilation of local energy statistics into a numbers game, and the asymmetry between pressure and ability is an important reason why data is distorted (Li et al., Citation2016; Qi & Wu, Citation2013; Ran, Citation2013). Third, Eaton and Kostka (Citation2014) argue that cadre rotation affects cadres’ incentives and implementation capacities; high cadre turnover has significant negative consequences as local cadres tend to select cheap and quick approaches to environmental policy implementation. Besides institutional factors, Zhang and colleagues (Citation2018) observe that local leaders’ educational level and age can heavily affect the percentage of environmental concerns in overall city planning, especially if they have environmentally-related majors.

We now turn to ‘strategic narrative’ as the second type of top-down policy instrument adopted in China. Narratives profoundly shape individuals’ views on climate change, and strategic narratives play an important role in Chinese politics where they function as a form of state power. By determining ‘(in)appropriate’ formulations, the Chinese government regulates what is being said and written and, by extension, what is possible within the Chinese political system (Geall & Ely, Citation2018; Schoenhals, Citation1992). Zhang and Orbie (Citation2019) argue that China’s climate discourse coalition consists of four sources of strategic narratives, ranging from top leaders’ speeches, Chinese climate negotiators’ statements, climate experts’ opinions, and official newspapers’ coverage. Shen and Wang (Citation2019) claim that the central-level narratives and policy documents mainly serve as political announcements that exhibit the ambition and sincerity of Chinese leadership. Geall and Ely (Citation2018) use the ideological narrative of ‘ecological civilization’ as an example, as it proposes to build specific transition pathways and foster potential system innovations.

Alongside target-setting and strategic narratives, a growing strand of research has examined market-based mechanisms as an important way of mitigating climate change and as a necessary complement to the traditional command-and-control approach. Within this line of research, scholars focus mainly on whether market mechanisms can fit into the unique Chinese political-economic context (Delman, Citation2011; Lo, Citation2013; Lo & Howes, Citation2013, Citation2015). Emission trading scheme (ETS) has been imported into China starting in 2013 as an important approach to mitigate climate change in China. Seven pilot sites, including two provinces (Hubei and Guangdong) and five major cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Chongqing, and Shenzhen), have been approved and given considerably leeway to design and operate their own schemes, de-facto experimenting with this rather innovative instrument in the context of China (Munnings et al., Citation2016; Shen & Wang, Citation2019; Zhang, Citation2015). In 2017, the central government has confirmed its plan to construct a national ETS system based on the lessons and experience gathered from previous pilot experiments, may eventually become the world’s second-largest after the EU ETS, viewed as a major step forward in creating a global carbon market (Lo, Citation2016). The preparation and construction of this new mechanism are notably efficient and implemented in a typical top-down fashion, combined with the abundant knowledge and practices of ETS around the world, especially from the EU, through a large number of capacity building programmes, often co-developed by international and EU organizations and experts on emission trading (Jiang et al., Citation2016; Munnings et al., Citation2016). Gilley (Citation2012) suggests that the neoliberal logic of the carbon market is not fully compatible with China’s authoritarian tradition of climate governance.

This body of work also led to a better understanding of the obstacles to an effective Chinese carbon market. For example, Lo (Citation2016) outlines the four major deficits of Chinese ETS: inadequate domestic demand, limited financial involvement by private finance, incomplete regulatory infrastructure, and excessive government intervention. On the question of why the Chinese ETS lack adequate demand, Lo (Citation2015) shows that the absence of a nationwide emission cap leads to weak demand for emission allowances or offset, since firms are under no obligation to reduce carbon emissions. From the institutional perspective, Lo (Citation2016) argues that the existing regulatory infrastructure of the Chinese carbon market is far from complete compared with a rather accurate and consistent system for measurement, monitoring, reporting and verification. In addition, permit allocation remains arbitrary. The excessive state intervention also causes doubts as prices are regulated by the central authority, and price control means that carbon prices under the ETS would reflect political judgment rather than the marginal cost of production (Lo, Citation2016). Some scholars (Goron & Cassisa, Citation2017; Lo et al., Citation2018) interpret the existing ETS pilots an emerging ‘climate capitalism with Chinese characteristics.’

Some research gaps in this area can be identified. First, the interaction between new market mechanism and the pre-existing climate policies and the overall institutional landscape call for more in-depth analysis. Second, research should scrutinize more carefully how varying experiences and lessons contribute to building a national ETS. Finally, the question of whether the Chinese ETS has contributed to the transition to low-carbon development in China and how to measure the outcome also needs further investigation.

4.3. Who is governing climate change?

It is increasingly recognized that states are limited in the degree to which they can directly influence the GHG emissions within their territory as well as the ability of societies to adapt to climate change as emissions are the product of billions of decentralized and independent decisions by non-state actors (Bulkeley & Newell, Citation2010; Heal, Citation1998-12). China’s recently revised Environmental Protection Law points to the importance of public participation and highlights the role of society in protecting public interests (Westman & Broto, Citation2019).

Consequently, a third theme emerging from our systematic literature review is the changing landscape of actors who participate in climate governance. However, only a limited number of papers scrutinize the role of non-state actors as relevant stakeholders. More frequently, studies address the structure and power dynamic of state actors vis-à-vis society at large. As Qi and Wu (Citation2013) argue, state actors still take centre stage in combating climate change in China. However, Mol (Citation2009) and Kwon and Hanlon (Citation2016) observe a clear trend towards more room for citizens to organize themselves in the policy process since the first decade of the 2000s. At the same time, Kostka and Zhang (Citation2018) insist that developments in the environmental field of China in the past decade show a centralization tendency characterized by the reinforcement of top-down management, alongside ever tighter controls on civil society and public participation. This does not mean that there is no research addressing non-state actors in China. In fact, we notice substantive discussions on the emerging ‘green civil society’ consisting of five different non-state actors: Chinese and international environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs), scholars, business actors, media, and the general public. Researchers investigate the different roles and relevance of non-state actors, and to what extent they create real impact. To answer those questions, researchers started with distinguishing different non-state actors and their way of realizing influence.

A number of articles focus on the role of Chinese and international ENGOs in governing climate change in China. Liu and colleagues (Citation2017) summarize three main functions of Chinese green NGOs under the authoritarian context of China, including government engagement, professional and financial capacity enhancement, and public opinion and awareness shaping. International ENGOs like Greenpeace and the World Resources Institute (WRI) fit into a unique niche in China as they enjoy competitive edges when compared with their Chinese counterparts in terms of sufficient funding and professional capacity. Westman and Broto (Citation2019) argue that international ENGOs are gaining an increasingly visible position in Chinese environmental politics through campaigns, research, and local projects. Research also identifies challenges the ENGOs face when addressing climate change in China, typically including: limited political space, insufficient professional capacity, shortage of funding, and weak public awareness of climate change (Ibitz, Citation2011; Liu et al., Citation2017). Due to those obstacles, when compared with their Western counterparts, Liu and colleagues (Citation2017) conclude that Chinese ENGOs are mainly involved in lobbying and implementation instead of monitoring the central government’s performance, and in technical fixes for practical problems rather than targeting institutional weaknesses. Ibitz (Citation2011) argues that China’s non-state actor landscape is relatively underdeveloped and restricted, and there is little room for non-state actors to gain leverage on political decision-making in a bottom-up manner. Besides all the challenges and obstacles, scholars find that ENGOs do play a part as bottom-up drivers of climate change policy, supervising local governments and mobilizing public support for the implementation of specific climate policies; they also try to keep the appropriate balance between political mobilization and public advocacy (Bernauer et al., Citation2016; Kwon & Hanlon, Citation2016; Liu et al., Citation2017; Nonneman, Citation2009).

Another important non-state actor is China’s climate change expert community, which provides consultancy and technical advisory services to political leaders, thereby significantly influencing agenda-setting and policymaking (Wubbeke, Citation2013a, Citation2013b). There are three pathways for experts and scholars to exert influence on climate agenda-setting and policymaking. First, by participating in government-sponsored research, experts can deliver their knowledge through internal meetings with high-level officials, by writing internal reports, or even more directly by contributing to official policy documents. Second, joining a government-funded advisory committee is another way of influencing climate policy. It is currently the most direct and consequential instrument for climate experts to communicate with the government with stable access to leadership (Wubbeke, Citation2013a). The selection of qualified experts is highly restrictive. Only a limited number of prestigious scientists can gain access to influential institutions such as the General Assembly from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). CAS operates as a think-tank and provides decision-making support for national climate policy, such as the National Program on Addressing Climate Change. The third pathway of gaining influence as a scientist is by working as an ‘expert-negotiator’ in the Chinese delegation to the Conference of the Parties (COP) of the UNFCCC. The increasing number of negotiation topics during any one COP and the limited technical capacity of the national delegation, give experts a competitive edge on specific technical issues. Research has found that on average, around 15 to 20 experts join the official negotiators during a COP event, accounting for one-third of the entire delegation (Wubbeke, Citation2013a). The contradictory part is that the closer one expert links to the government, the greater influence it can yield but with more difficulty to challenge and question its policy and action. Wubbeke (Citation2013a) uses the case of Hu Angang, one of the most influential experts in the climate policy domain, who failed to persuade the Chinese government to accept internationally binding targets in the run-up to the Copenhagen Conference in 2009. In general, only a small number of experts closely affiliated with the government have the ability to significantly influence climate policy decisions, and their impact is limited to certain foundational principles within China's approach to addressing climate change.

Business actors, particularly those in the energy and energy-intensive sector (iron, steel, cement, and electricity production), banks, and real estate companies, play an important role in city-level climate governance. Given their influential role, they usually enjoy a hybrid role as both the governance taker and maker in the policy process. (Guan & Delman, Citation2017; Shen, Citation2015; Wang et al., Citation2018; Westman & Broto, Citation2018). The interactions between local government and economic actors might hold the key to climate mitigation. However, local government finds itself in a difficult position, as regulating economic actors could undermine the local government’s ability to finance the low-carbon transition due to the lack of tax revenue. (Guan & Delman, Citation2017; Westman et al., Citation2019). For example, Westman and colleagues (Citation2019) show that a local steel factory has a significant impact on the municipal government’s potential to pursue a low-carbon agenda as the steel factory shares a dual role as the main source of local tax income and as the main driver of emissions. In more cases, engagement with economic actors positively works as the governance maker. Guan and Delman (Citation2017), for example, use the case of the Hangzhou city energy efficiency initiative to show how energy service companies participate in climate governance by providing independent technology consultancy and supporting project implementation. Many studies also focus on economic actors’ role as governance takers. Wang and colleagues (Citation2018) argue that enterprises work with the government through a public-private partnership, in which the government provides financial and policy support for enterprises’ energy-saving activities. In return, firms are required to improve their energy efficiency, cut emissions, and meet the targets set by the government. In low-carbon technology transfer projects, Chinese companies collaborate with foreign firms to import facilities (e.g. wind turbines and district heating and cooling technology), giving companies a unique niche to fit in the local level climate governance (Westman & Broto, Citation2018).

The media, especially the internet-based media, is identified as another actor who yields limited influence on climate governance through monitoring local government practices and fostering public awareness on climate change issues (Eberhardt, Citation2015; Gilley, Citation2012; Wang et al., Citation2018). Often, media provides a platform for other types of non-state actors in governing climate change. Academics shape public opinion through social media and also make their climate expertise known to policymakers (Wang et al., Citation2018). Liu and colleagues (Citation2017) also indicate that Chinese NGOs active in the climate field have made ample use of media to gain more autonomy and agenda-setting power over the last decade. However, scholars tend to view the media in China as having failed in supervising and challenging public policies (Ellermann, Citation2013; Gilley, Citation2012). Among them, the official media occupies a special role in governing climate change in China. One of the most important and well-recognized functions is legitimizing the messages communicated by the top leadership. Another function is filling in the substance of the rather vague concept provided by top leaders to make them more clearly defined (Ellermann, Citation2013). In general, China’s official media works as tools through which the Chinese government can project its national image outwards and build its identity domestically.

Outside the circle of political and scientific elites, the general public also has access to environmental deliberations, in particular through online discussion forums, referred to as the ‘green public sphere’ (Sun et al., Citation2018). Researchers argue that the general public only plays a marginal role in climate issues for two reasons: first, due to their lack of expertise, citizens are considered illegitimate participants in climate policymaking (Westman & Broto, Citation2019); second, citizens are more engaged in environmental issues, such as air pollution or habitat resettlement compared to climate change, as these topics more directly influence people’s well-being (Zhang & Orbie, Citation2019). Citizens are encouraged to follow existing policies and to be model consumers with a low-carbon footprint but do not have a significant impact on policymaking. Therefore, climate change in a sense becomes an issue that both is public and is not public at the same time (Eberhardt, Citation2015).

In a nutshell, only a very limited number of non-state actors are found to meaningfully participate in governing climate change in China. Actors who lack expertise or impact are unlikely to participate or be influential in the governing process. Regarding research gaps in this area, we find that a limited number of publications to date focus on the dual role of non-state actors in China both as governance makers and takers and their potential to optimize the governance process. Also, how existing bottom-up hybrid initiatives work in the unique context of China, and whether those collaborations are enough to integrate broader societal concerns and trigger changes that enable a transformation for sustainability, calls for further investigation.

4.4. How does China compare with other countries and regions?

The fourth and final theme identified in this literature review concerns comparative analysis among regions and groups of countries with similar features. This line of research is driven by a few main research concerns: Why do countries perform differently on climate change mitigation? How have power dynamics changed under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), and how do these changes in relative power translate into policy outcomes?

Frequently analyzed comparative groups of states include those within or among the BASIC countries (Brazil, India, South Africa, and China) or regional/ geopolitical groups such as those in East Asia. They also include comparisons of China and among major superpowers (e.g. China–EU and/or China–US). Common comparative aspects include: comparing climate governance at different levels, such as institutional structure and policy patterns across countries (Aamodt & Stensdal, Citation2017; Barbi, Citation2016; Ferreira & Barbi, Citation2016; Gabriel & Schmelcher, Citation2018; Gilley, Citation2017; Gladun & Ahsan, Citation2016; He, Citation2018; Liu et al., Citation2013; Pittock, Citation2011; Schmitz, Citation2017; Schreurs, Citation2010; Scott, Citation2009; Viola & Basso, Citation2016); comparing a specific climate policy areas among countries (de Jong et al., Citation2017; Harrison & Kostka, Citation2014; Liu et al., Citation2019; Stevens, Citation2019; Thavasi & Ramakrishna, Citation2009; Valenzuela & Qi, Citation2012; Zhao & Alexandroff, Citation2019), for example policies on green buildings or on energy efficiency; countries’ positions in the international climate negotiation (Banerjee, Citation2012; Gilley, Citation2017; Hallding et al., Citation2013; Hochstetler & Milkoreit, Citation2014; Lachapelle & Paterson, Citation2013; Shi et al., Citation2015; Stokes et al., Citation2016; Terhalle & Depledge, Citation2013; Weiler, Citation2012); and rethinking existing conceptualization or theories based on country case studies (Prendeville et al., Citation2018; Proskuryakova, Citation2018; Zhang, Citation2015).

What can be learned from a comparative perspective on climate governance across countries? Several studies focus on countries’ choices (when compared with China) of policy instruments and factors that can explain observed differences in policy choices, including countries’ comparative politics, domestic energy structure, financial capacity, and state-business-civil society relations. Three main findings emerge from this comparative politics literature when investigating explanations for variation in policy choices and performance. First, scholars argue that specific national circumstances affect countries’ instrument choices. Liu and his colleagues (Citation2013) argue that countries’ administrative systems play an important role in governing climate change as its adaptiveness determines the bottom-up local mitigation activities; for example, both China and Japan are shown to face difficulties in advancing from ‘making plans’ to ‘taking actions’. Lachapelle and Paterson (Citation2013) state that many policy instruments (e.g. regulation and standards, economic incentives) are relatively indiscriminate concerning the various comparative features of the state, and structural impediments due to different institutional settings are not obvious. In this sense, they argue that cooperation across countries could enhance the performance of climate policies and broaden the adoption of the available range of policies. Second, Never and Betz (Citation2014) found that among emerging economies, high production of fossil fuels, limited financial capacity, and a weak influence of NGOs are sufficient conditions leading to weak performance. Yet, they also find that a limited local green industry and weak global negotiation influence only partially account for inadequate climate change governance. In the area of adaptation, He (Citation2018) argues that a complex combination of factors leads to differences in adaptation responses, including climate politics and awareness of adaptation, the status of environmental principles, and the judiciary’s role. The differences and interplay between these factors are key drivers determining how governments react to adaptation challenges, particularly when faced with legislative gridlock and scientific uncertainty.

A handful of studies focus on international climate negotiation where China interacts with other countries and on how this affects the negotiation outcomes. Research questions discussed include: how power dynamics have changed since the Copenhagen Climate Conference; the determinants of bargaining success in climate negotiations; how the domestic settings interact and affect countries’ international stance; and to what extent international commitment can be translated into actual policy output.

Lachapelle and Paterson (Citation2013) argue that the traditional ways of classifying climate coalitions (North–South divide) fall short of capturing the ongoing changes in country-level emissions trajectories and that policy divergence across developed and developing countries also appears less substantive than has traditionally been assumed. Hochstetler and Milkoreit (Citation2014) insist that the emergence of a third category of country, one that is neither developed nor developing, offers opportunities for novel governance arrangements, the redistribution of rights and obligations, and the burden-sharing arrangements for the provision of global public goods.

Many scholars focus on BASIC countries’ role and cooperation in climate negotiations, what brought them together, and whether the cooperation will continue. BASIC countries provide an important platform for joint emerging power interests and security for bottom-line issues for developing countries (Banerjee, Citation2012; Hallding et al., Citation2013). Hochstetler and Milkoreit (Citation2014) argue that the BASIC group clearly shows the aggregation strains that are possible when trying to develop joint identities, and their different understandings of the behavioural expectation for emerging powers has introduced productive tension into negotiations, pushing more reluctant members to cooperative action at crucial points in time. For example, Banerjee (Citation2012) also finds an apparent deviation within this group when China gradually adopted a more open stance regarding Durban’s legally binding treaty. Hallding and colleagues (Citation2013) argue that the cooperation will likely continue on ‘agreed on’ issues as they share the identity of big emitters and emerging economies.

Research on the determinants of bargaining success in climate change negotiations also stands out in the literature. Weiler (Citation2012) observes that the influence of powerful nations in climate change negotiations, such as the US and China, may not be as strong as previously assumed. The considerable share of GHG emissions and the extremity of the negotiation positions were found to be detrimental to their bargaining success. Terhalle and Depledge (Citation2013), for example, argue that the traditional material power structures and the normative beliefs underlying the Western order have been contested, with real repercussions for global climate governance regimes. On that account, the slow progress of climate change negotiations is due not just to the politics itself but also to the absence of a new political bargain on material power structures, normative beliefs, and the international order.

When investigating the actual influence that international negotiations have on policy outcomes, Gilley (Citation2017) observes that international negotiations have very little to do with mitigation outcomes in either China or India; what makes governance effective has more to do with local political economy and culture, cosmopolitan influences, and administrative networks. In this sense, international partners should pay more attention to policy diffusion and learning opportunities for local leaders to identify low carbon policy ideas from abroad. Lachapelle and Paterson (Citation2013) argue that the evolving patterns in emissions and policy are important background features within countries’ domestic structures and that international climate change negotiations are unlikely, at least in the short term, to change such patterns.

5. Conclusions

Four research themes emerge from our systematic literature review of 250 articles on climate change governance in China (2009 – 2019): a) the motivations behind China’s climate action; b) available policy instruments for governing climate change; c) the role of non-state actors; and d) comparative analysis between China and other countries. Regarding the incentives behind climate change action, the main motivations are found to be domestic considerations. Economic growth is still a conflicting factor that often contradicts and constrains both the central and local governments from taking more significant actions regarding climate governance. Further reconciliation between economic growth and climate change mitigation is needed. A strong focus on motivations shows increasing interest from the outside world (as all the publications are mainly for English readers), as it attempts to understand and interpret China’s climate actions, which are increasingly proactive and visible within the specter of global climate governance. China may need to rethink its outward-looking communication strategy on climate change, instead of its current singular strategy of promoting itself to a restricted audience through limited means (national media or top leaders’ speeches). Alternatively, the country could adopt more diverse approaches to communication and seize the opportunity of important international platforms (e.g. COPs) to showcase its motivations behind its climate policy.

With regard to the policy instruments, although China’s national climate governance is highly authoritarian, at the local level, practice is more complex, with a mixture of both authoritarian and liberal features. The benefits and pitfalls of this institutional setting are however clear. The authoritarian system has the advantage of being quick to respond and take action. This is particularly important in the face of global climate change, where there's an urgent need to rapidly decrease China's emissions. This highly centralized style of governance at the national level, embedding cadre management with a target responsibility system, can lead to quick action in the early phase of governance, and achievement of some short-term mitigation goals. However, due to the absence of careful policy planning and the promotion-driven strategy adopted by local governments, the current approach is ineffective in creating adaptable policies with continuous incentives. As a result, this approach hinders the establishment of a sustainable climate policy and falls short of facilitating a long-term shift to a low-carbon transition. Considering the unique political context of China, a future research issue may be to what extent the degree of authoritarianism impacts positively on the effectiveness of climate governance in China.

Several studies also show that non-state actors do have the chance to participate but that they are limited largely to actors possessing economic or technological expertise and influence. These actors include large domestic firms, research centres, international development banks, and multinational companies. The Chinese government still occupies a central and prominent role in climate mitigation, mainly through state-led investment and through its network of state-owned enterprises. The limited involvement of non-state actors also reflects the current elite-lead features of the governance system. A limited number of papers focused on non-state actors’ roles in China, how they make real impacts, and how the issues of climate justice are addressed during the governance process. Therefore, we implore the need for further research to focus on non-state actors’ dual roles in China, both as governance makers and governance takers.

Comparative studies concerning China and other countries’ strategies and performance in mitigating climate change have shown that despite differences among countries, the adoption of policy tools has sufficient similarities to provide hope for collaboration among countries in governing climate change. This line of research faces one key challenge: lacking reliable and consistent data to reach comparable results looking across countries. Also, some studies simply aggregate the results of separate country studies together, which cannot fully answer the question of why some countries perform better than others; nor do they offer explanations that might improve global climate governance. Though the comparison with other countries’ information dilutes the content of insights into China, such comparative research does provide a valuable external perspective for studying China’s climate governance. Comparing China with other countries in climate governance can corroborate some arguments on similar issues, or it can highlight conflicts and differences to stimulate further investigation. However, most literature on this research theme was published before 2015, and we thus lack updated information on how different coalitions and power dynamic landscapes have changed after the Paris Agreement. For future research, we encourage a more current and thorough examination of the interactions and relationships between China and other nations within the realm of climate governance. We also suggest the need for more investigation into institutional obstacles and opportunities that are produced by the varying features of different states in terms of collective action and coordination among different countries.

Concerning the theories adopted in the literature, most political theories and concepts are originally derived from Western, liberal democratic contexts. Therefore, they sometimes fail to fully explain practice in non-Western contexts; they cannot consider both the historical and geographical aspects, and the nature of state power that is exercised in such non-Western contexts. The case studies sometimes only focus on a certain level of governance, overlooking the broader context, and lack adequate consideration of the interlinkage and coherence between different levels of governance. As a result, these studies struggle to interpret more complex realities on the ground and fail to go beyond generic recommendations. This is also why a review such as this one is necessary, given the fragmented form of information and knowledge that we currently have. In future research, we encourage climate governance scholars to investigate the coherence and interlinkages among different levels of climate governance as China develops different roles for its various actors and adopts different strategies from local to global scale.

Exploring the various levels of China’s climate governance is both important and necessary, especially for readers outside of China. China is unique in terms of its institutional setting, history, culture, and role in global climate governance. An updated and comprehensive understanding of China’s diverse role in governing the climate challenge contributes to the field’s expanding knowledge base and improves the communication between China and the rest of the world.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (45.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (61 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Dr. Piero Morseletto, Cornelia Fast, Daniel Petrovics, and Daniel Pennifold for their valuable comments in shaping and improving this paper. Additionally, the authors wish to acknowledge the invaluable contributions of the three anonymous reviewers and the diligent editorial team, whose constructive feedback and guidance played a pivotal role in enhancing the quality of our work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aamodt, S., & Stensdal, I. (2017, September). Seizing policy windows: Policy influence of climate advocacy coalitions in Brazil, China, and India, 2000–2015. Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions, 46, 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.08.006

- Banerjee, S. B. (2012, December). A climate for change? Critical reflections on the Durban United Nations climate change conference. Organization Studies, 33(12), 1761–1786. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840612464609

- Barbi, F. (2016, September). Governing climate change in China and Brazil: Mitigation strategies. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 21(3), 357–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-016-9418-y

- Beeson, M. (2018, January). Coming to terms with the authoritarian alternative: The implications and motivations of China's environmental policies. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 5(1), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/app5.217

- Bernauer, T., Gampfer, R., Meng, T. G., & Su, Y. S. (2016, September). Could more civil society involvement increase public support for climate policy-making? Evidence from a survey experiment in China. Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions, 40, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.06.001

- Bulkeley, H., & Newell, P. (2010). Governing climate change. Routledge.

- Chen, B., Shen, W., Newell, P., & Wang, Y. (2017). Local climate governance and policy innovation in China: A case study of a piloting emission trading scheme in Guangdong province. Asian Journal of Political Science, 25(3), 307–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185377.2017.1352524

- ChinaDaily. (2020). Full text: Statement by Xi Jinping at General Debate of 75th UNGA https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202009/23/WS5f6a640ba31024ad0ba7b1e7.html

- ChinaDialogue. (2020). Questions of climate leadership: The case of the EU and China.

- Chiu, D. (2017). The east Is green: China’s global leadership in renewable energy. Center for Strategic and International Studies(CSIS). Retrieved March 24, from https://www.csis.org/east-green-chinas-global-leadership-renewable-energy

- Chmutina, K., Zhu, J., & Riffat, S. (2012). An analysis of climate change policy-making and implementation in China. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 4(2), 138–151. https://doi.org/10.1108/17568691211223123

- Chu, S. Y., & Schroeder, H. (2010). Private governance of climate change in Hong Kong: An analysis of drivers and barriers to corporate action. Asian Studies Review, 34(3), 287–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2010.507863

- de Jong, M., Stout, H., & Sun, L. (2017, February). Seeing the people's republic of China through the eyes of Montesquieu: Why Sino-European collaboration on Eco city development suffers from European misinterpretations of “good governance”. Sustainability, 9(2), Article 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9020151

- Delman, J. (2011). China’s “radicalism at the center”: regime legitimation through climate politics and climate governance. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 16, 183–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-010-9128-9

- Eaton, S., & Kostka, G. (2014). Authoritarian environmentalism undermined? Local leaders’ time horizons and environmental policy implementation in China. The China Quarterly, 359–380. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741014000356

- Eberhardt, C. (2015). Discourse on climate change in China: A public sphere without the public. China Information, 29, 33–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203X15571261

- Eckersley, R. (2020, December). Rethinking leadership: Understanding the roles of the US and China in the negotiation of the Paris agreement. European Journal of International Relations, 26(4), 1178–1202. Article 1354066120927071. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066120927071

- Ellermann, C. (2013). Climate change politics with Chinese characteristics: From discourse to institutionalised greenhouse gas mitigation [PhD thesis, University of Oxford, UK]. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:accc3067-0525-46e5-bc43-bf7931f35529

- Fan, X. C., & Wang, W. Q. (2016, February). Spatial patterns and influencing factors of China's wind turbine manufacturing industry: A reviews. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews, 54, 482–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.10.020

- Ferreira, L. D., & Barbi, F. (2016, December). The challenge of global environmental change in the Anthropocene: An analysis of Brazil and China. Chinese Political Science Review, 1(4), 685–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0028-9

- Francesch-Huidobro, M. (2012). Institutional deficit and lack of legitimacy: The challenges of climate change governance in Hong Kong. Environmental Politics, 21(5), 791–810. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2012.686221

- Francesch-Huidobro, M., & Mai, Q. (2012). Climate advocacy coalitions in guangdong, China. Administration & Society, 44(6_suppl), 43S–64S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399712460068

- Gabriel, J., & Schmelcher, S. (2018, March). Three scenarios for EU-China relations 2025. Futures, 97, 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2017.07.001

- Geall, S., & Ely, A. (2018, December). Narratives and pathways towards an ecological civilization in contemporary China. China Quarterly, 236, 1175–1196. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741018001315

- Gilley, B. (2012). Authoritarian environmentalism and China's response to climate change. Environmental Politics, 21(2), 287–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2012.651904

- Gilley, B. (2017, September). Local governance pathways to decarbonization in China and India. China Quarterly, 231, 728–748. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741017000893

- Gladun, E., & Ahsan, D. (2016). Brics countries’ political and legal participation in the global climate change agenda. Brics Law Journal, 3(3), 8–42. https://doi.org/10.21684/2412-2343-2016-3-3-8-42

- Goron, C., & Cassisa, C. (2017, February). Regulatory institutions and market-based climate policy in China. Global Environmental Politics, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00392

- Green, F., & Stern, N. (2016). China's changing economy: Implications for its carbon dioxide emissions. Climate Policy, 17, 423–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2016.1156515

- Guan, T., & Delman, J. (2017). Energy policy design and China's local climate governance: Energy efficiency and renewable energy policies in Hangzhou. Journal of Chinese Governance, 2(1), 68–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/23812346.2017.1284430

- Hallding, K., Jurisoo, M., Carson, M., & Atteridge, A. (2013, September). Rising powers: The evolving role of BASIC countries. Climate Policy, 13(5), 608–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2013.822654

- Hansen, M. H., Li, H., & Svarverud, R. (2018, November, 01). Ecological civilization: Interpreting the Chinese past, projecting the global future. Global Environmental Change, 53, 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.09.014

- Harrison, T., & Kostka, G. (2014, March). Balancing priorities, aligning interests: Developing mitigation capacity in China and India. Comparative Political Studies, 47(3), 450–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013509577

- Harrison, T., & Kostka, G. (2019, June). Bureaucratic manoeuvres and the local politics of climate change mitigation in China and India. Development Policy Review, 37, O68–O84. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12386

- He, L. (2010). China's climate-change policy from Kyoto to Copenhagen: Domestic needs and international aspirations. Asian Perspective, 34(3), 5–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42704720

- He, X. B. (2018, July). Legal and policy pathways of climate change adaptation: Comparative analysis of the adaptation practices in the United States, Australia and China. Transnational Environmental Law, 7(2), 347–373. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2047102518000092

- Heal, G. M. (1998-12). New strategies for the provision of global public goods: Learning from the international environmental challenge. Paine Webber Working Paper No. PW-98-11. Available at SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=279192

- Hilton, I. (2016). China emerges as global climate leader in wake of Trump’s triumph. Guadian Environment Network. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/nov/22/donald-trump-success-helps-china-emerge-as-global-climate-leader

- Hilton, I., & Kerr, O. (2017). The Paris agreement: China's ‘New normal’ role in international climate negotiations. Climate Policy, 17(1), 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2016.1228521

- Hochstetler, K., & Milkoreit, M. (2014, March). Emerging powers in the climate negotiations: Shifting identity conceptions. Political Research Quarterly, 67(1), 224–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912913510609

- House, T. W. (2014). FACT SHEET: U.S.-China Joint Announcement on Climate Change and Clean Energy Cooperation. Retrieved March 16, from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/11/11/fact-sheet-us-china-joint-announcement-climate-change-and-clean-energy-c

- Ibitz, A. (2011, June). China's climate change mitigation efforts from an ecological modernization perspective. Issues & Studies, 47, 151–203. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000297235200005.

- IEA. (2021a). An Energy Sector Roadmap to Carbon Neutrality in China. IEA. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/9448bd6e-670e-4cfd-953c-32e822a80f77/AnenergysectorroadmaptocarbonneutralityinChina.pdf

- IEA. (2021b). Total CO2 emissions, China (People's Republic of China and Hong Kong China) 1990–2019. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-browser/?country=CHINAREG&fuel=CO2%20emissions&indicator=TotCO2

- Jiang, J. J., Xie, D. J., Ye, B., Shen, B., & Chen, Z. M. (2016, September). Research on China's cap-and-trade carbon emission trading scheme: Overview and outlook. Applied Energy, 178, 902–917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.06.100

- Jiang, P., Chen, Y., Geng, Y., Dong, W., Xue, B., Xu, B., & Li, W. (2013). Analysis of the co-benefits of climate change mitigation and air pollution reduction in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 58, 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.07.042

- Kostka, G. (2016). Command without control: The case of China's environmental target system. Regulation & Governance, 10(1), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12082

- Kostka, G., & Hobbs, W. (2012, September). Local energy efficiency policy implementation in China: Bridging the Gap between national priorities and local interests. China Quarterly, 211, 765–785. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741012000860

- Kostka, G., & Zhang, C. M. (2018). Tightening the grip: Environmental governance under Xi Jinping INTRODUCTION. Environmental Politics, 27(5), 769–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1491116

- Kwon, K. L., & Hanlon, R. J. (2016, August). A comparative review for understanding elite interest and climate change policy in China. Environment Development and Sustainability, 18(4), 1177–1193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-015-9696-0

- Lachapelle, E., & Paterson, M. (2013, September). Drivers of national climate policy. Climate Policy, 13(5), 547–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2013.811333

- Li, H., Zhao, X., Yu, Y., Wu, T., & Qi, Y. (2016). China's numerical management system for reducing national energy intensity. Energy Policy, 94, 64–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2016.03.037

- Li, H. M., Wu, T., Zhao, X. F., Wang, X., & Qi, Y. (2014, March). Regional disparities and carbon “outsourcing”: The political economy of China's energy policy. Energy, 66, 950–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2014.01.013

- Li, J. (2018). China’s new environment ministry unveiled, with huge staff boost. Retrieved March 16, from.

- Li, J. (2019). Xie Zhenhua: China’s top climate negotiator steps down. Retrieved March 16, from https://chinadialogue.net/en/climate/11717-xie-zhenhua-china-s-top-climate-negotiator-steps-down-2/

- Li, Y., Beeton, R. J. S., Sigler, T., & Halog, A. (2019, April). Enhancing the adaptive capacity for urban sustainability: A bottom-up approach to understanding the urban social system in China. Journal of Environmental Management, 235, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.01.044

- Li, Y., & Shapiro, J. (2020). People’s republic of China goes green: Coercive environmentalism for a troubled planet. WILEY. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/China+Goes+Green%3A+Coercive+Environmentalism+for+a+Troubled+Planet-p-9781509543137

- Li, Z. J., Galvan, M. J. G., Ravesteijn, W., & Qi, Z. Y. (2017, January). Towards low carbon based economic development: Shanghai as a C40 city. Science of the Total Environment, 576, 538–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.034

- Liu, L., Wang, P., & Wu, T. (2017, November-Dec). The role of nongovernmental organizations in China's climate change governance. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Climate Change, 8(6), Article UNSP e483. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.483

- Liu, L. X., Matsuno, S., Zhang, B., Liu, B. B., & Young, O. (2013). Local governance on climate mitigation: A comparative study of China and Japan. Environment and Planning C-Government and Policy, 31(3), 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1068/c11246

- Liu, Y. X., Lu, Y. J., Hong, Z. S., Nian, V., & Loi, T. S. A. (2019, March). The “START” framework to evaluate national progress in green buildings and its application in cases of Singapore and China. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 75, 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2018.12.007

- Lo, A. Y. (2013). Carbon trading in a socialist market economy: Can China make a difference? Ecological Economics, 87, 72–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.12.023

- Lo, A. Y. (2015, March). National development and carbon trading: The symbolism of Chinese climate capitalism. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 56(2), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2015.1062731

- Lo, A. Y. (2016, January). Challenges to the development of carbon markets in China. Climate Policy, 16(1), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2014.991907

- Lo, A. Y., & Francesch-Huidobro, M. (2017, December). Governing climate change in Hong Kong: Prospects for market mechanisms in the context of emissions trading in China. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 58(3), 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12166

- Lo, A. Y., & Howes, M. (2013, August). Powered by the state or finance? The organization of China's carbon markets. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 54(4), 386–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2013.870794

- Lo, A. Y., & Howes, M. (2015). Power and carbon sovereignty in a Non-traditional capitalist state: Discourses of carbon trading in China. Global Environmental Politics, 15(1), 60–82. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00272

- Lo, A. Y., Mai, L. Q. Q., Lee, A. K. Y., Francesch-Huidobro, M., Pei, Q., Cong, R., & Chen, K. (2018, June). Towards network governance? The case of emission trading in Guangdong, China. Land Use Policy, 75, 538–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.04.021

- Lo, K. (2014, April). China's low-carbon city initiatives: The implementation gap and the limits of the target responsibility system. Habitat International, 42, 236–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.01.007

- Lo, K. (2015, December). How authoritarian is the environmental governance of China? Environmental Science & Policy, 54, 152–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.06.001

- Marks, D. (2010). China's climate change policy process: Improved but still weak and fragmented. Journal of Contemporary China, 19, 971–986. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2010.508596

- Men, J. (2014). Climate change and EU–China partnership: Realist disguise or institutionalist blessing? Asia Europe Journal, 12, 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-014-0373-y

- Mol, A. P. (2009). Urban environmental governance innovations in China. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 1(1), 96–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2009.07.002

- Munnings, C., Morgenstern, R. D., Wang, Z., & Liu, X. (2016). Assessing the design of three carbon trading pilot programs in China. Energy Policy, 96, 688–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2016.06.015

- Never, B., & Betz, J. (2014, July). Comparing the climate policy performance of emerging economies. World Development, 59, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.01.016

- Niiler, E. (2018, December 04). China Is Both the Best and Worst Hope for Clean Energy. https://www.wired.com/story/china-is-best-worst-hope-at-cop24-climate-summit/

- Nonneman, G. (2009, November). International society and the Middle East: English school theory at the regional level. International Affairs, 85(6), 1249–1250. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000271416600010. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2009.00860.x

- Pittock, J. (2011). National climate change policies and sustainable water management: Conflicts and synergies. Ecology and Society, 16(2), Article 25. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000292462800008. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04037-160225

- Prendeville, S., Cherim, E., & Bocken, N. (2018, March). Circular cities: Mapping Six cities in transition. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 26, 171–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2017.03.002

- Proskuryakova, L. (2018, October). Updating energy security and environmental policy: Energy security theories revisited. Journal of Environmental Management, 223, 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.06.016

- Qi, Y., & Wu, T. (2013, July-August). The politics of climate change in China. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Climate Change, 4(4), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.221

- Ran, R. (2013). Perverse incentive structure and policy implementation gap in China's local environmental politics. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 15(1), 17–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2012.752186

- Schmitz, H. (2017). Who drives climate-relevant policies in the rising powers? New Political Economy, 22(5), 521–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1257597

- Schoenhals, M. (1992). Doing things with words in Chinese politics: Five studies (Vol. 41). Engels.

- Schreurs, M. (2017). Multi-level climate governance in China. Environmental Policy and Governance, 27(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1751

- Schreurs, M. A. (2010, June). Multi-level governance and global climate change in East Asia. Asian Economic Policy Review, 5(1), 88–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-3131.2010.01150.x