ABSTRACT

The goals of the Paris Agreement (PA) on collectively managing climate change can only be reached if all parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) commit to actions supporting their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Developing-economy nations play a crucial role in reaching the PA targets, particularly in the Agriculture, Forest, and Other Land Uses (AFOLU) sector. However, developing country Parties also face several constraints in tracking and communicating progress towards their climate policy targets and implementation of their NDCs. The operationalization of Biennial Transparency Report (BTR) and Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF) under the PA will bring stricter reporting timeframes and advanced transparency for all parties. With these requirements rapidly coming into force, addressing reporting gaps is now a pressing priority. The present study analyzes the NDCs, and Biennial Update Reports (BURs) submitted by developing country Parties under the UNFCCC. In an illustrative exercise, our in-depth analysis concentrates on reporting on the AFOLU sector and identifies issues impeding a comprehensive and comparable Global Stock Take (GST): (i) issues of consistency in reporting timeframes (ii) issues in transparency of reporting on mitigation sectors and on relevant progress indicators (iii) incomparability of methodological approaches proposed and used, and (iv) the implications of limited national capacity for transparent reporting. The UNFCCC and developed country Parties now have the opportunity of providing specialized support for developing country Parties. This could include tailored guidance to address gaps in both greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions accounting, and reporting challenges, to ensure consistent, comprehensive, and transparent reporting to reinforce capacities moving forward following the next GST.

Key policy insights:

The lack of consistent, transparent, and comparable communication from developing country Parties on NDC progress for key climate change impact mitigation sectors, such as AFOLU, has implications for operationalization of the GST.

Delayed and inconsistent reporting are expected to affect the aggregation and consolidation of information across countries to inform global progress.

Increased support for tailored capacity building and data gathering is required to enable transparent communication on progress in NDC implementation, monitoring, and reporting.

Developing country groups will need to improve the transparency of reporting progress on the implementation and achievement of their NDCs to match the expected increase in carbon footprints with growing economies.

1. Introduction

Since the early 1990s, member states to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) have participated in negotiations around climate change mitigation, and many have committed to reduced emissions from different sectors (Maizland, Citation2021). Several pledges have been made in successive UNFCCC global meetings. The Paris Agreement (PA) sets the most recent and critical milestone for parties to reach a commitment of limiting global warming to well below 2°C, compared to pre-industrial levels to ensure global wellbeing. Parties are expected to set targets and communicate progress towards realizing the global climate-mitigation or adaptation goals by reducing greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions and improving resilience in the face of climate change.

Transparently communicating NDC targets and progress towards them is at the core of the PA, along with tracking of global progress in climate actions (Taibi & Konrad, Citation2018). The PA sets criteria regarding transparent communication for tracking progress towards NDCs mainly across Articles 4, 6, and 13. Article 4, for example, requires countries to provide ‘information necessary to track progress made in implementing and achieving its nationally determined contribution’, through the Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF) (Article 13.7b). The ETF requires parties to regularly and transparently report necessary information that allows tracking progress in implementation and achievements of NDCs. Specifically, all Parties, except least developed country (LDC) Parties and Small Island Developing States (SIDS), shall submit information reported under Article 13.7 ‘no less frequently than on a biennial basis’. Article 4 further requests all parties to prepare and communicate NDCs. Article 6 also requires a robust accounting to communicate internationally transferred mitigation outcomes and avoidance of double counting in reporting on GHG emissions. Article 13 requests the development of modalities, procedures, and guidelines (MPGs) under the ETF to communicate the progress towards implementation and achievements of NDCs.

As indicated in Article 13 (para. 5 and 6), the ETF is informing the Global Stock Take (GST) (Article 14). The GST encompasses the process for taking stock of collective progress towards achieving the PA goals (Northrop et al., Citation2018). Meeting the PA transparency requirements thus contributes towards a successful GST. The first GST is to conclude at the COP 28, and will be repeated every 5 years thereafter; it is thus essential that collective progress from both developed and developing country Parties is regularly and consistently communicated. The report from the technical dialogue of the first global stocktake encourages increased ambitions in successive NDCs and emphasized that enhanced transparency from upcoming BTRs and NDCs can help track progress (UNFCCC, Citation2023). Consistently communicating NDC updates, as well as submitting timely, and complete reporting of other inputs are essential for the GST and for assessing global progress. Using comparable, complete, accurate, and verifiable approaches to reporting, and quantitative progress indicators is also required for transparent accounting of GHG emissions by sources and removals by sinks. Efficient monitoring and reporting will depend on the emergence of national measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) capacities. Developing country Parties are expected to communicate in submitted NDC and BUR documents their needs for finance, and capacity building as well as progress made on mitigation and adaptation implementation.

Parties’ reporting was initially guided under the Kyoto Protocol and later the Copenhagen agreement by the concept of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities’, where differentiated reporting requirements and timetables were assigned depending on the status of Parties: Annex I (developed country) versus non-Annex I (mostly developing country) Parties. Developed country Parties were subject to more detailed requirements and stricter timelines in reporting under the UNFCCC. By contrast, developing country Parties, especially least developed countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS), are less restricted on reporting details under the UNFCCC, where biennial update reports (BURs) are subject to review processes, which are less rigorous compared to developed country Parties Biennial Reports (BRs). However, developing country Parties are facing requirements since the 2010 Cancun agreement that are now becoming increasingly demanding and stringent.

Along with PA implementation, a more consistent reporting and reviewing approach is requested across all Parties today. It establishes ETF, where all Parties need to submit a Biennial Transparency Report (BTR), which supersede BURs and BRs, and are prepared in accordance with modalities, procedures, and guidelines (MPGs)Footnote1 that supersede the existing MRV requirements. Parties to the convention communicate their mitigation targets and time frames, key information on scope and coverages, assumptions and methodological approaches, as well contributions towards achieving the PA goals through their submission of NDCs. Parties summarize the description of their NDC in their BTR against which progress made in implementation and achievement of their NDC will be tracked. Yet, the PA also accommodates a ‘built-in flexibility’, where the varying capacities of developed- versus developing country Parties are considered. However, it is argued that such a bifurcation of Annex I and non-Annex I Parties (or developed- and developing country Parties) under the UNFCCC will influence the level of global transparency that can be achieved. This also considers the flexibilities the PA sets out for developing countries bearing in mind their more limited reporting capacities.

Several studies and platforms track global progress towards implementation of NDCs, mainly looking into submitting NDCs, updating targets, focusing on GHG emission trends, and sectors considered. However, an in-depth synthesis of submitted documents for developing countries does not exist. This is needed for identifying where and which developing country Parties are providing transparent information (or not), and what the implications are for a GST. Developing country Parties appear to have specific sets of challenges that stem from their financial and technological status, and the complexity of sectors contributing to GHG emissions and removal. Importantly, the Agriculture, Forest, and Other Land Uses (AFOLU) sector – which accounts for about 32% of GHG emissions from developing country parties (FAO, Citation2023) – requires advanced methodologies and datasets for estimating complex carbon dynamics originating from varying natural and anthropogenic processes (Perugini et al., Citation2021). Such reporting and emission accounting challenges can hinder capabilities to comply with advanced MPG guidelines and prevent generating required datasets with the expected level of accuracy and consistency (Vaidyula & Rocha, Citation2018). Experiences derived from current reporting should inform future directions for the ETF, which is already requiring more detail and increased frequency of reporting than previously (Hattori & Umemiya, Citation2020).

This study synthesizes the communication and transparency of reporting on NDC progress from non-Annex I Parties,Footnote2 from here on referred as developing county Parties. In doing so, it aims to identify: (i) the reporting consistency of developing country Parties on NDC progress; (ii) how transparently targets, and mitigation sectors are being communicated; (iii) whether comparable methods and indicators are being applied across developing country Parties’ reporting; and (iv) what implication differences in national measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) capacities and performance have for developing country Parties’ reporting. This synthesis gives an overview of the compliance of developing country Parties with NDC progress reporting requirements under existing communication and transparency arrangements. It also indicates the reporting potential and the capacity of developing country Parties to manage their transition into the ETF under the PA, and thus contribute towards the GST exercise.

2. Methods and approaches

The UNFCCC database (UNFCCC, Citation2021a, Citation2021b) was explored to obtain details on NDC and BUR submissions, and to establish track records on communication through counting key documents submitted by developing country Parties. An open-source database that summarizes BURs (8th version) (Hattori & Umemiya, Citation2021) and NDCs (Ikeda & Hattori, Citation2021) from the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES) was used to establish the synthesis framework for this study.

The UN standard country or area codes for statistical use (also known as M49) (UN, Citation2018) has been adopted to group developing country Parties with similar profiles to summarize results, identify patterns, and provide tailored recommendations (). Accordingly, even though Parties can belong to multiple groups, for the purpose of this study they were grouped under the following exclusive categories: Least Developed Countries (LDC); Landlocked Developing Countries (LLDC); Developing Regions (DINGR); Small Island Developing States (SIDS); and Developed Regions (DR). DINGR countries that have also been classified as LLDC or LDC under the UN M49 are categorized here as LDCs. From each country category, the top five countries that have the highest AFOLU share to total national CO2 emissions (in 2020 were chosen to further discuss and compare findings (FAO, Citation2023). This choice of selected countries and sector was made to explore transparency in some depth and in an illustrative way.

Table 1. Country groups of non-Annex I Parties.

A total of 307 NDCs and updates (including INDCs, updated NDCs and, new first NDCs) from all 154 developing country Parties, and 107 BURs from 64 of these countries were submitted to the UNFCCC between 2014 and June 2021. These were reviewed to synthesize elements of communication and transparency of NDC reporting (see ).

Table 2. Review approaches used to extract elements of communication and transparency.

This study enriches the existing IGES database by including details of communication and transparency indicators. These are details that align with Article 4 and 13 requirements set for tracking progress in NDC design, communication, and implementation. Consistency in communication was assessed by using indicators that include: the number of reports submitted; reporting intervals; time lag between inventory and reporting periods; and updates of mitigation targets across consecutive NDCs. Specific chapters from latest BURs were also carefully reviewed through keyword search and content analysis to assess information related to transparency and capacity. These chapters included: mitigation actions; finance, technology, and capacity building; needs and support received; and domestic measurement, reporting and verification. Details on transparency were explored by deep diving into BURs and taking the AFOLU sector as an example to assess the transparency of communication on progress indicators. Quantitative indicators that measure changes of mitigation include how the area and volume of emissions are reported and how emission-related entities are classified. The latter can be considered as a continuous quantitative indicators, while those that captured implementation of interventions such as policy/law, and market elements are regarded as discrete quantitative indicators. The analysis also considered whether IPCC GHG emission reporting guidelines (Buendia et al., Citation2019) were adopted, and if so which tier of reporting was used. Finally, countries’ capacity to monitor and report progress on NDCs was evaluated by analyzing the information provided through BURs; this includes information regarding the availability of national MRV protocols as well as on MRV support needed and received, and on the state of institutional capacity for preparation of NDCs ().

3. Results

3.1. Reporting consistency

3.1.1. Track record of developing country Parties’ reporting to the UNFCCC

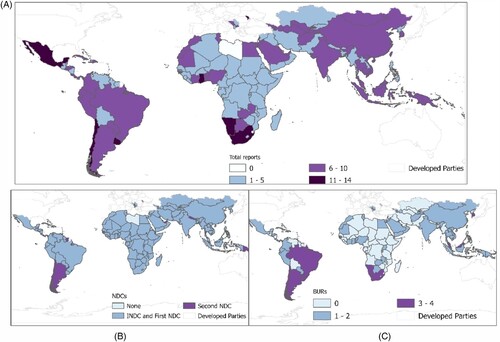

Developing country Parties’ track records in communicating progress on climate actions, between December 1997 and June 2021 shows that frequent reporting is coming from LLDC, DINGR, and DR groups which on average submitted six reports, while LDC and SIDS groups have made an average of five reports (). Countries like Chile, Moldova, Namibia, and Uruguay have the highest submission of communication documents, while the least number of submissions are coming from Angola, Iraq, and State of Palestine, with no submission made from Libya.

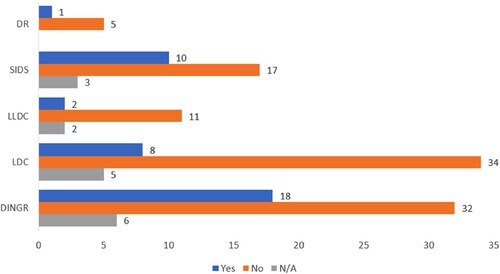

Specifically, through INDCs, communication of proposed climate actions by countries ahead of the PA were submitted by all developing country Parties except Libya (). After this, NDC submissions were made after countries formally joined the PA; these being made by the majority of developing country Parties, except a few DINGR countries. Second NDCs, which are expected to represent improved ambitions are submitted by only 6% of the developing country Parties, mostly from the SIDS group (). In total, the countries that made the least submission of NDCs are mostly from DINGR groups despite the group comprise countries undergoing dynamic economic development that can have associated implications on climate actions.

As for the BURs, despite UNFCCC guidelines, where expectations are to have four submissions per country by 2021, more than half (60%) – mostly countries from of LDC and SIDS groups – have not made submissions. While only DINGR and DR groups submitted two reports on average, the rest have submitted only one NDC.

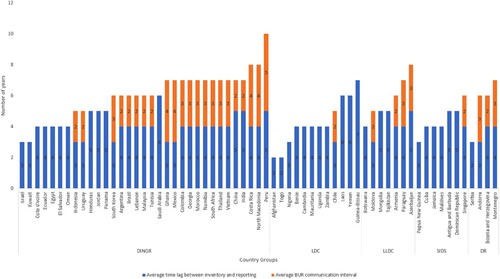

Results on the temporal consistency in communication of BURs by developing country Parties show that the recommended 2-year interval between consecutive reporting have not been met, and the average interval is 3 years (). Similarly, a large time lag exists between inventory time and reporting year. Looking across all country categories, they reported with an average 4-year time lag. Several SIDS and LDC countries exhibit time lags ranging from 5 to 7 years. Only two countries: Afghanistan, and Togo (both LDCs) reported their inventories with a 2-year time lag.

Figure 2. Average time lag interval between consecutive BURs and the average time lag between inventory time and BUR communication year of developing country Parties (n = 64).

Note: Developing country Parties are organized here by type: Least Developed Countries (LDCs), Landlocked Developing Countries (LLDC), Developing Regions (DINGR), Small Island Developing States (SIDS), and Developed Regions (DR).

3.2. Transparency in reporting

3.2.1. Communicating mitigation targets and updates

Most developing country Parties (138 out of 154) report on quantitative mitigation targets, setting clear baselines for tracking progress in NDCs. Many have set absolute emission-reduction targets against a specific base year, while some have expressed relative targets to reduce emissions below ‘business as usual’ scenarios. The few Parties that did not communicate quantitative targets included other strategies, policies, and actions to enforce low emissions. With the submission of consecutive NDCs less than half of the reporting countries from DINGR and SIDS groups updated their NDC targets. Only a few countries from the LDC group were able to update their targets (). No quantitative targets or updates are communicated by about 10% of all developing country Parties, except for DR. About 77% of the mitigation target updates were made between INDC and first NDCs, while the rest of the target updates were made with second NDCs submissions.

Figure 3. NDC quantitative mitigation targets set and updated by developing country Parties.

Note: Countries are organized by type: Least Developed Countries (LDC), Landlocked Developing Countries (LLDC), Developing Regions (DINGR), Small Island Developing States (SIDS), and Developed Regions (DR). N/A: countries did not communicate quantitative targets.

3.2.2. Communicating mitigation sectors and indicators chosen

Looking into the sector-specific mitigation measures that countries communicated in their NDCs towards achieving their targets, almost all Parties transparently specified the sectors of importance. AFOLU is the second largest in terms of frequency of covered sectors by developing country Parties, following only energy ().

Figure 4. IPCC sectors covered in developing country Parties’ NDCs of (n = 154).

Note: ‘AFOLU and other sectors’: AFOLU is one among a range of other sectors being reported, ‘Other sectors, no AFOLU’: Energy (or other sectors) but without any AFOLU reporting, ‘Not Available’ refers to countries that did not provide information on mitigation sectors.

The level of detail Parties provide on mitigation measures, and accounting for progress for these at the sectoral level, varies substantially across countries. Taking the AFOLU sector as an example, some parties provide details in their NDC and BUR documents, including indicators and information on how they adapted and used IPCC accounting methodologies. However, most reporting countries lack specificity and clarity in how they communicate such essential components to track progress from the AFOLU sector.

Most Parties provide AFOLU-related mitigation action indicators on forest and agriculture sub-sectors that measure area and/or volume of AFOLU activity, related actions, products, and emissions (). They use quantitative variables such as: annual change in forest cover, expansion of protected areas, number of livestock, and reduced emissions, respectively. Discrete quantitative variables are also in use and these mainly measure the number of policies and laws introduced. Other indicators track market and investment related developments. Here, variables include the number of laws passed and tenure titles issued, as well as amounts of resources mobilized, and jobs created.

Table 3. AFOLU-related mitigation indicators reported in latest BURs by developing country Parties, with details on top five countries having the highest share of AFOLU to national CO2 emission.

Improved agricultural inputs and infrastructure in support of agricultural production are also taken as key indicators. Policy and law, as well as market and consumption variables are among the least-used indicators across country groups in support of quantifying progress. However, integration of different types of indicators to cover the scope of sector activity was minimal across most groups. Only a few countries, such as Brazil, Colombia, and India, consider how to measure changes using the combination of physical as well as policy and market indicators.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization Corporate Statistical (FAOSTAT) global emissions databases (FAO, Citation2023) for the years 2012–2017, DINGR countries contributed to 66% of AFOLU emissions from developing parties, followed by LDC (28%), LLDC (5.4%), SIDS (0.5%), and the DR (0.1%). Zooming in to understand how transparent countries are communicating progress from the AFOLU sector, the analysis shows only countries from the DINGR group provided details on indicators use (out of the top countries with the highest CO2 emissions from the AFOLU sector). However, only one of the top five high CO2-emitting countries from AFOLU in the SIDS and LDC group was transparent about indicators in use. Most (60%) reporting SIDS countries had missing information on AFOLU indicators, even though, on average, forests cover around 70% of their total land area.

3.2.3. Communicating MRV standards and protocols

The selection of the IPCC tiers (Buendia et al., Citation2019) for the AFOLU reporting is an indicator of the accuracy and level of detail of emissions estimates in national GHG inventories. In brief, Tier 1 approaches apply global default values and are easiest to apply, as they require the least-detailed knowledge about emitting activities. Tier 1 methods are widely used across country groups. Higher tiers require more knowledge: Tier 2 uses country-specific data and Tier 3 goes further to apply detailed modelling and data-driven methods. Tier 3 methods are typically in use only by DINGR and LLDC groups. For instance, all the top five CO2-emitting countries from the DINGR group combined Tier 1 and Tier 2 approaches (). LDC and SIDS groups provide limited information on approaches used for carbon-stock accounting and reporting. None of the top AFOLU CO2-emitting countries provided explicitly reported on which Tier they used (except Nigeria of the LDC group). Similarly, information on IPCC good practice guidelinesFootnote3 (GPG) is lacking for more than half of the LDC and SIDS countries. This review shows that most countries that provided information used the 2006 IPCC GPG as per the PA stipulation.

Table 4. Transparency on standards used for measuring AFOLU emissions and mitigation actions by developing country Parties as indicated in NDC and BUR reports.

3.3. National monitoring and reporting capacities

Countries also report on their own national ability to track and report progress on NDC implementation (). This was reported as weak by the majority of countries in the LDC (72%) and SIDS (76%) groups, while the majority of the DR (83%), and DINGR (59%) countries have not provided clear information in their NDCs about their reporting capacity. Suriname is the only country among the top five high CO2-emitting countries from the AFOLU sector that have reported a strong capacity. The corresponding information provided on BURs regarding the availability of an MRV protocol shows that majority of the countries in the DINGR and DR group have a system in place, while majority of the countries from LDC, LLDC, and SIDS groups have not provided explicit information.

Table 5. Developing country Parties own reporting of capacity to monitor and report progress on NDCs, as indicated in NDC and BUR reports.

3.3.1. Support needed and received

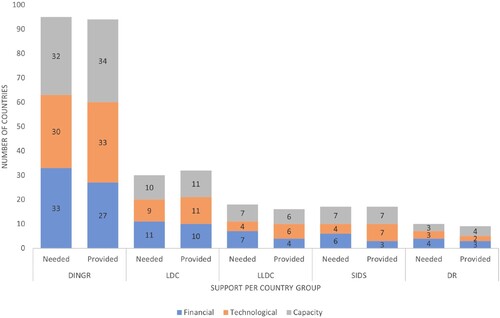

The synthesis of latest BUR reports shows that overall, developing countries Parties have expressed more demand for finance in support of NDC implementation; this is followed by demand around needs for technological transfer and capacity building.

Even though quantitative figures are not compared between demands made (and the estimate of needs) and support provided, financial support is mostly reported by parties as provided (94%), followed by technology support (78%) and capacity building support (74%) (). There are relatively more unmet financial needs across all country groups. Mismatches between support needed and provided was found higher for technological support for DINGR, LDC, and LLDC groups, while the gap on capacity building and financial support was highest for SIDS and DR groups, respectively.

Figure 5. Developing country Parties reporting in BURs on support needed and received for implementing and communicating nationally determined contributions.

Note: Reporting countries: Least Developed Countries (LDC = 47), Landlocked Developing Countries (LLDC = 15), Developing Regions (DINGR = 56), Small Island Developing States (SIDS = 30), and Developed Regions (DR = 6).

4. Discussion

The documentation linked to NDCs should provide clear, transparent, and understandable information for ensuring comparability and accountability in tracking national progress towards mitigation targets among other climate policy goals. Our findings from the analysis of NDC and BUR reports of developing country Parties traces sources of inconsistencies in communication that could adversely affect GST exercises. These include temporal inconsistencies and time lags in reporting; lack of clarity in describing targets and approaches used with estimation of GHG emissions and removals; and gaps in MRV national-level capacities. These inconsistencies are underlying factors that can jeopardize the tracking of global progress towards the PA mitigation goals. The gaps in NDC communication observed from this study can be summarized around the three principal elements of effective communication and transparency: consistency; comparability; and capacity.

4.1. Consistency

Our study reveals that communication of NDC progress varies not only between developed- and developing country Parties (Pauw et al., Citation2019), but also among groups of developing country Parties ( and ). It appeared that mostly the DINGR and DR groups perform better in consistency and completeness of reporting compared to other groups. However, it is acknowledged that timely and reliable reporting from all developing country Parties is essential. As per FAO's statistics on emission shares (FAO, Citation2023) developing country Parties contribute to 95% of global GHG emissions from the AFOLU sector, and missing communications from these Parties will omit substantial information on emissions and removal.

Figure 1. Number of key reports from developing country Parties (n = 154) submitted to the UNFCCC between December 1997 and June 2021.

Note: (A) Total climate action related reports submitted (i.e. Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), Biennial Update Reports (BURs), National Communications (NCs), Technical Annex on REDD+, Greenhouse-Gas Inventories (GHGI) and National Inventory Reports (NIR)); (B) NDCs submitted, (C) BURs submitted.

This analysis also reveals that the UNFCCC guidelines for developing country Parties to submit consequent BURs every 2 yearsFootnote4 might not be realistic. This review shows an overall 3-year average BUR reporting interval, and that many countries report less frequently. In addition, the large time lag observed between the inventory period and reporting year are likely to produce discrepancies that undermine global accounting and collective progress, particularly as we approach the target year of 2030. Vaidyula and Rocha (Citation2018) discussed a similar finding from 94 developing country Parties that submitted inventory data in national communications (NCs) or BURs published in 2015 or later. They found that only 1% of these countries reported data for the period ending X-2, 17% for X-3, 20% for X-4, 16% for X-5 and 46% for X-6 or older. Our assessment shows a similar pattern but with a moderate improvement, where there is an overall average of 4 years lag, with only 2% reporting with a 2-year lag frame; many SIDS and LDC countries had a delay of 5–7 years. In comparison, developed country Parties routinely report on emissions for year X-2 at year X in their GHG emissions inventories (Vaidyula & Rocha, Citation2018).

Capturing the most recent information will be challenging for developing country Parties, considering the length of time it takes to compile inventories and prepare BUR documents. Other studies have also tracked progress towards completing NDCs, covering both developed- and developing country Parties. These show how flexibilities offered for developing country Parties can lead to incomplete and incomparable information for the GST (Vaidyula & Rocha, Citation2018; Weikmans et al., Citation2020). Doyle (Citation2019) and Vaidyula and Rocha (Citation2018) reasoned that the differences in reporting experience originates from the more stringent reporting requirements that developed country Parties had to follow since implementation of the 1992 Climate Convention. Overcoming such communication challenges and reporting discrepancies will require an increased effort in aligning all NDC reporting according to a common time frame. This in turn will assist the GST in providing an accurate and consistent picture of progress, so that parties can make informed decisions when updating and upgrading NDCs (Dagnet & Cogswell, Citation2019).

Encouragingly, 138 countries out of the 154 developing country Parties provided communications on NDC quantitative targets. Such transparent communication of concrete and time bound targets is essential to provide baseline against which progress can be tracked. However, the update of NDC targets with subsequent NDC submissions appears limited as only a quarter of the Parties provided enhanced updates. Different studies have indicated underlying motivating factors that can lead to increased mitigation ambitions. The synthesis by Fransen et al. (Citation2022) explored how lowered cost of technologies, as well as greater availability of improved data and models could encourage countries to establish ambitious targets, and make realistic assessments of their implementation plans. Aggarwal et al. (Citation2022) and Weikmans et al. (Citation2020)), advised that a well-informed general public will also play a key role in challenging and holding governments accountable in meeting their targets as well as encouraging them to become more ambitious. However, this also depends on reliable information generated by the ETF to enhance public understanding and engagement in climate actions. It is also reported that ambitious NDCs can also be restricted due to lack of access to finance (Doyle, Citation2019).

Clarity is also missing in most cases in communicating the sub-sectors and indicators considered in the AFOLU sector ( and ) even though AFOLU came out as the second most important mitigation sector for developing country Parties. This finding is reinforced by the latest NDC synthesis report by UNFCCC (UNFCCC, Citation2021b) and the African, Caribbean and Pacific groups (ACP, Citation2018). This review shows the lack of clarity is especially true for the agriculture sub-sector and in the case of LDC, and SIDS country groups. Fransen et al. (Citation2022) also state that a quarter of current NDCs with land-use, land-cover and forest (LULCF) targets lack the specificity and clarity required for informing planned NDC implementation and tracking of progress. The UNFCCC (Citation2017) guidelines for developing country Parties on BUR preparations advises that progress indicators are key for describing mitigation actions and due attention should be given in providing associated details. Compared to forest actions however, few indicators are used in the BUR to track progress from agriculture-related actions. This could be due to challenge of acquiring necessary data to estimate emissions factors and other indicators for agricultural mitigation activities and the complexity (ecological, social, and economic) of agricultural landscapes (Ross et al., Citation2019).

4.2. Comparability

The methodologies and approaches used by developing country Parties for tracking carbon-stock change from mitigation progress, mostly appear incomplete and incomparable across groups (). The PA requiring each party to use the 2006 IPCC Guidelines (Article 13, Paragraph 20) to compile their emissions inventory and for reporting is likely to be achieved. Most reporting from developing country Parties indicates that they are already using it. However, it will be difficult to integrate information from LDC and SIDS countries, as the majority did not communicate which IPCC approaches they used as their guidance. Lacking such information will obscure understanding of the approaches used for data collection, and uncertainty and quality assurance analysis.

Higher accuracy should be achieved in moving to higher tiers of methods for inventory preparation, yet capacity for these is lacking. This is especially true in LDC and SIDS countries, while the LLDC group showed better performance using Tier 2 and Tier 3 approaches. Romijn et al. (Citation2012) linked this challenge with expense. It is costly to move from using global default values to using higher tier methods with intensive data requirements for monitoring local variables. Chen and Dietrich Brauch (Citation2021) examined the national Inventory Reports (NIRs) of developed country Parties. They found significant differences in the GHG emissions reported, mainly originating from the differences in GHG-accounting methodologies and approaches across countries. Considering the need for consistent and comparable inventories across countries, the study stressed the need for a harmonized GHG-accounting framework, both for developed- and developing country Parties.

Crumpler et al. (Citation2020) on the other hand proposed to unpack NDCs into five main pillars and sub-areas specific to AFOLU. This aimed to overcome the data aggregation and analysis challenges originating from heterogeneity of NDCs’ scope, format, and level of detail. However, this only gives qualitative and categorical information on progress and communication transparency, and not the quantitative solution to aggregate and interpret efforts with varying proportions. The UNFCCC's is developing outlines for the Biennial Transparency Report (BTR), National Inventory Document (NID), and Common Reporting Tables (CRTs) in support of the ETF. These efforts are essential to help resolve some key challenges with methodology comparability issues (Rocha, Citation2019).

4.3. Capacity

The direct effect of national capacity on reporting has come to light in our study, where the LDC and SIDS groups self-reported that they have weak country capacity to implement and monitor NDC progress. Indeed this analysis shows they have lower performance in consistency, transparency, and comparability of NDC reporting. These groups are also said to have unique capacity constraints in implementing the ETF under the new guidance of MPGs in preparation of their expected BTRs in 2024 (IIED, Citation2019). Several studies have similarly-associated capacity issues as an underlying factor affecting reporting capabilities. Romijn et al. (Citation2012) stated that the majority of developing country Parties have limitations in providing complete and accurate estimates of forest loss and GHG emissions. In addition, the study showed that net forest gain was reported from only the few countries that had a very small capacity gap, while all the rest reported forest loss, which could bring into question the accuracy of reporting coming from low-capacity countries. Financial and technical capacities of developing countries are also conditional factors for fulfilling NDC commitments (Fransen et al., Citation2022). Thus, most countries report on the gaps associated with financial needs, capacity building, and technology transfer as part of their NDC communication (). A synthesis of ACP reporting (ACP, Citation2018) further indicated that despite the urgent need to strengthen MRV systems in developing countries, most of these countries are not transparent in communicating details on their MRV system or on its key challenges. The synthesis by Fransen et al. (Citation2022) explored how lower technology costs, as well as increased availability of improved data and models could also encourage countries to establish ambitious targets, and make realistic assessments of their implementation plans. Aggarwal et al. (Citation2022) and Weikmans et al. (Citation2020) advised that a well-informed general public will also play a key role in challenging and holding governments accountable in meeting their targets, as well as encouraging them to be more ambitious. However, this also depends on reliable information generated by the ETF to enhance the understanding and engagement of the general public in climate actions. It is also reported that ambitious NDCs can also be restricted due to the lack of access to finance (Doyle, Citation2019).

Observed gaps in the availability of national MRV protocols and in country capacities (), as well as in corresponding gaps between support needed and received () undoubtedly reduce quality and frequency of observed reporting from LDC and SIDS countries. UNFCCC timelines lay out expectations for receiving the final BURs and the first BTRs from voluntary developing countries by no later than 31 December 2024 and the production of the next GST by 2028. However, considering limited progress with current BUR reporting, most developing country Parties need to increase their reporting frequencies and improve the transparency of what they are reporting. This could be made possible through enhancing national capacities and establishment of robust national MRV systems (Hönle et al., Citation2019). For example, a study by Nesha et al. (Citation2021) showcased how capacity supportFootnote5 resulted in improved forest monitoring and reporting in tropical countries. FAO’s (Citation2019) case study on Mongolia similarly indicated the crucial role of capacity, where an under-developed MRV capacity was observed in the sector. This resulted in high uncertainties in estimating GHG emissions, thus challenging reliable NDC reporting. Active support for strengthening institutional setups and capacity building is ongoing through the UNFCCC, as well as different bilateral and multilateral agencies (Supplementary material II). Yet, such efforts should advisedly follow a new framework to transition from a short-term and project-based nature to a demand-driven and country-owned long-term system that is also tailored to different groups within developing country Parties (Khan et al., Citation2020). Further funds mobilization is needed to support generating reliable data and enhancing reporting capacity in developing country Parties, for example through South–South collaboration. Continued support is also needed to address institutional and capacity needs for establishing better-informed targets, and for developing and communicating tailored monitoring approaches across mitigation sectors (FAO, Citation2019). The technical dialogue report from the first GST similarly recognizes the need addressing locally determined needs, enhancing climate finance, and the need for coherence and coordination of support in capacity building towards developing countries (UNFCCC, Citation2023).

5. Conclusion

The PA has set strong global commitments along with requirements for transparent approaches for acquiring reliable information on progress in generating NDCs with implications for wider global mitigation progress. However, conducting GST with up-to-date and reliable information could be difficult, since most developing country Parties struggle with poor MRV systems, weak national NDC implementation approaches, and limited reporting capacity, as well as unmet needs for financial support, access to technology, and technical capacity. Considering the current state of reporting, NDC reports from developing country Parties did not meet the required level of completeness, consistency, and comparability required to fully inform the current GST. Our results highlight the need for improved support as countries continue to make progress towards achieving 2030 emissions reduction targets and reporting on these.

The policy priorities for increasing transparency need to start with quantified targets and focus on good metrics for measuring progress. Yet, in the key sector of AFOLU, national land-classification systems are not always consistent with IPCC categories. Importantly, remote sensing can help with assessing land-use and land-use change and some aspects of assessing changes in agricultural land management for better consistency with UNFCCC Common Reporting Tables. Additionally, countries should focus on developing consistent time series from 2020 onwards. Stepwise approaches, building on national strengths and making progress in priority areas such as AFOLU, can help reduce uncertainty and offer achievable and progressive improvement of country monitoring of progress and reporting.

Our analysis focused on data and reporting outcomes, and we did not look at institutional issues. However, we know from ongoing consultations in the UNFCCC that institutional issues, and issues related to national capacity, continue to be a bottleneck. Accelerating capacity building and sharing of best practices in methodology, data collection and analysis, and reporting from countries with stronger capacity, could help accelerate progress, particularly when best practices can be shared among countries with similar emissions’ profiles.

UNFCCC's direction on flexibility for developing country Parties’ reporting also needs to be well defined to ensure that it leads to reliable accounting of global emissions. In addition, it is important to address the issues that reporting time lags have for the aggregation and consolidation of information across countries. Establishing a clear understanding of the expected timeline for submitting recent inventory dataFootnote6 can support the GST to capture up-to-date information.

Addressing the main pillars of transparency (i.e. MRV, institutional arrangements, and country capacity), as well as incorporation of new data sources, can lead to better reporting and more reliable communication of NDC progress from developing country Parties. This will require meeting requests from developing country Parties for support (in finance, capacity, and technology). Here it will be necessary to use the several available international and regional platforms to help facilitate, support, and improve NDC progress reporting. Developing country Parties that comply with current BUR reporting requirements are expected to be better placed to submit the first BTR under the Paris Agreement in 2024. On the other hand, the many gaps observed in reporting leading up to the first GST suggests that the GST is undoubtedly incomplete. Thus, a priority in the coming years is to strengthen ways of working with developing countries to fill these gaps and improve the quality of reporting.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the editorial support of Vincent Johnson, consultant editor to the Alliance Bioversity-CIAT Science-Writing Service.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

3 To guide AFOLU sector accounting for carbon pools and fluxes.

4 Except for LDCs and SIDS, who may submit BURs at their own discretion.

5 Provided for a growing integration of remote sensing and national forest inventories.

6 Less than or equal to 4 years prior to the current reporting year, as per COP-17 decision.

References

- ACP. (2018). Climate ambitions: An analysis of nationally determined contributions (NDCs) in the ACP group of states. https://intraacpgccaplus.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/NDC_long_report_EN.pdf

- Aggarwal, J., Bhasin, S., & Sumit, P. (2022). Communicating climate action effectively: Reporting framework for nations to inform the public.

- Buendia, E., Tanabe, K., Kranjc, A., Jamsranjav, B., Fukuda, M., Ngarize, S., Osako, A., Pyrozhenko, Y., Shermanau, P., & Federici, S. (2019). 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories.

- Chen, S., & Dietrich Brauch, M. (2021). Comparison between the IPCC reporting framework and country practice.

- Crumpler, K., Meybeck, A., Federici, S., Salvatore, M., Damen, B., Gagliardi, G., Dasgupta, S., Bloise, M., Wolf, J., & Bernoux, M. (2020). A common framework for agriculture and land use in the nationally determined contributions (Vol. 85). Food and Agriculture Organization.

- Dagnet, Y., & Cogswell, N. (2019). Setting a common time frame for nationally determined contributions.

- Doyle, A. (2019). The heat is on: Taking stock of global climate ambition. NDC Global Outlook Report, United Nations Development Programme and United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

- FAO. (2019). Enhancing transparency in the agriculture, forestry and other land use sector for tracking nationally determined contribution implementation in Mongolia. http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/CA7185EN/

- FAO. (2023). FAOSTAT emissions shares. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/EM

- Fransen, T., Henderson, C., O’Connor, R., Alayza, N., Caldwell, M., Chakrabarty, S., Dixit, A., Finch, M., Kustar, A., & Langer, P. (2022). The state of nationally determined contributions: 2022.

- Hattori, T., & Umemiya, C. (2020). Can developing countries meet the reporting requirements under the Paris Agreement? In IGES discussion paper.

- Hattori, T., & Umemiya, C. (2021). IGES BUR database.

- Hönle, S. E., Heidecke, C., & Osterburg, B. (2019). Climate change mitigation strategies for agriculture: An analysis of nationally determined contributions, biennial reports and biennial update reports. Climate Policy, 19(6), 688–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1559793

- IIED. (2019). Meeting the enhanced transparency framework: what next for the LDCs? .

- Ikeda, E., & Hattori, T. (2021). IGES NDC database. In 2021 [2021-06-20]. https://pub.iges.or.jp/pub/iges-ndc-database

- Khan, M., Mfitumukiza, D., & Huq, S. (2020). Capacity building for implementation of nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement. Climate Policy, 20(4), 499–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1675577

- Maizland, L. (2021). Global climate agreements: Successes and failures (p. 25). Council on Foreign Relations.

- Nesha, M. K., Herold, M., De Sy, V., Duchelle, A. E., Martius, C., Branthomme, A., Garzuglia, M., Jonsson, O., & Pekkarinen, A. (2021). An assessment of data sources, data quality and changes in national forest monitoring capacities in the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2005–2020. Environmental Research Letters, 16(5), 054029. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abd81b

- Northrop, E, Dagnet, Y, Höhne, N, Thwaites, J, & Mogelgaard, K. (2018). Achieving the ambition of Paris: Designing the global Stocktake. World Resources Institute (WRI).

- Pauw, Pieter, Mbeva, Kennedy, & van Asselt, Harro. (2019). Subtle differentiation of countries’ responsibilities under the Paris Agreement. Palgrave Communications, 5(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0298-6

- Perugini, L., Pellis, G., Grassi, G., Ciais, P., Dolman, H., House, J. I., Peters, G. P., Smith, P., Günther, D., & Peylin, P. (2021). Emerging reporting and verification needs under the Paris Agreement: How can the research community effectively contribute? Environmental Science & Policy, 122, 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.04.012

- Rocha, M. (2019). Reporting tables – Potential areas of work under SBSTA and options – Part I: GHG inventories and tracking progress towards NDCs.

- Romijn, E., Herold, M., Kooistra, L., Murdiyarso, D., & Verchot, L. (2012). Assessing capacities of non-Annex I countries for national forest monitoring in the context of REDD+. Environmental Science & Policy, 19-20, 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.01.005

- Ross, K., Hite, K., Waite, R., Carter, R., Pegorsch, L., Damassa, T., & Gasper, R. (2019). Enhancing NDCs: Opportunities in agriculture.

- Taibi, F.-Z., & Konrad, S. (2018). Pocket guide to NDCs under the UNFCCC.

- UN. (2018). M49 standard. UN statistics division. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/#ldc

- UNFCCC. (2017). Training material for the preparation of biennial update reports from non-Annex I parties: Reporting mitigation actions and their effects.

- UNFCCC. (2021a). BUR registry. https://unfccc.int/BURs

- UNFCCC. (2021b). NDC registry. https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/NDCStaging/Pages/All.aspx

- UNFCCC. (2023). Technical dialogue of the first global stocktake. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/sb2023_09_adv.pdf

- Vaidyula, M., & Rocha, M. (2018). Tracking progress towards NDCs and relevant linkages between Articles 4, 6 and 13 of the Paris Agreement.

- Weikmans, R., van Asselt, H., & Roberts, J. T. (2020). Transparency requirements under the Paris Agreement and their (un)likely impact on strengthening the ambition of nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Climate Policy, 20(4), 511–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1695571