ABSTRACT

This paper offers a critical consideration of the proliferation of art museums situated in shopping malls in China. Creating interventions of art and the art museum within retail structures can be conceptually understood as a synthesis development model, whereby the combination of art and commerce is adopted by real estate enterprises in China. The operational characteristics of mall museums reflect a growing tendency for art to be used instrumentally to align with everyday life: an aestheticisation of the ordinary. In the late twentieth century, postmodernism placed great emphasis on the blurring of boundaries between art and everyday life, signalling the collapse of the distinction between high art and mass/popular culture [Baudrillard, Jean. 1983. Simulations. New York: Semiotext; Featherstone, Mike. 1990. Consumer Culture and Postmodernism, 64–80. London: SAGE Publications]. Nonetheless, through the example of the Chi Shanghai K11 Art Mall, this paper considers public engagement practices where ‘art is for the masses’ within such structures to explore whether curatorial strategies and art practices are influenced through a constant adaptation into ‘art museum retail’. It also aims to consider whether the development of these ‘persuasive spaces’ thus has the potential to include experimentation and knowledge production.

Introduction

In China, private art museums belonging to real estate developments are distinctive in the extent to which they patronise the arts sphere. The placement of art museum structures within shopping malls can be regarded as a form of strategic art sponsorship in order to attract visitors through advertising retail. Due to the booming development of the museum-retail concept within the real estate business in China, numerous private art museums were consecutively constructed and operated strategically aligning to luxury retail outlets. Although lagging behind Western patronage, Chinese real estate enterprises and individuals set up art museums through a trend of ‘Museumification’.Footnote1 Not only does art intervene in urban development, as a symbol of aesthetics of the everyday,Footnote2 it is also one of the mainstream approaches that incorporates patronage of the arts into the Chinese socioeconomic context. As the main type of corporate art patronage, art museums within shopping malls – called urban commercial complexesFootnote3 – was a particular convergence space which emerged in the process of culture-led regeneration.Footnote4 This type of art-led urban commercial complex is a close and highly involved collaboration between art and business, regardless of physical form, interactive model or commercial return.

The case study of Shanghai K11 Art Mall is a useful example of this art-led structure and was established in Huaihai Road, in a central location surrounded by numerous luxury shopping malls. The K11 Art Mall is the first ‘artistic’ shopping mall in mainland China utilising the strategy of ‘art museum retail’ in order to differentiate it from other shopping experiences and gain a competitive edge. The creation of the K11 Art Mall was based on an idea of integrating contemporary art into a luxury retail space, putting art at the centre of the shopping experience, and was subsequently copied by other developers to varying levels of success. Covering a total area of 400,000 square feet, including six ground and three underground floors, it houses the Chi K11 Art Museum, the K11 Art Store, the K11 Design Store, the K11 Select Store, restaurants and an office building. The Chi K11 Art Museum, which is registered as a private art museum, is located on Level B3 with a total floor area of 32,000 square feet (K11 Citation2017). The high visitor numbers and sound financial turnover of the K11 Shanghai corresponds with Adrian Cheng Chi Kong’s statement, that ‘they have embraced with enthusiasm the concept of infusing culture and art into the shopping experience’ (Forbes Citation2018). The Chi K11 Art Museum was founded in 2013 and made its initial splash with a Claude Monet exhibition in 2014, which drew large crowds; however, the visitors were not simply there for the exhibition itself, and this is only the beginning of the K11 story.

When aesthetic experience becomes more central to consumption, shopping, and leisure, the transformation of these areas into experience environments exhibits an aesthetically-driven transformation (Schulze Citation1992). Not only shopping malls, urban architecture, and individual appearance, aestheticisation also affects material, social, and subjective reality through technology, media, and style (Welsch Citation1996). Along with this, art in the shopping mall can be seen as part of a wider trend of the aestheticisation of everyday life (Baudrillard Citation1983; Featherstone Citation1990), making art-viewing part of the extended shopping experience, with some malls devoting themselves equally to organising exhibitions and activities in their art museums. Further, the social control provided by malls has emerged in mall designs that enables mall designers explicitly or implicitly to achieve the goal of social control. John Manzo (Citation2005), in the paper titled ‘Social Control and the Management of “Personal” Space in Shopping Malls', examines design innovations and social control phenomenon of shopping malls, which put forward the idea of innovations in mall design to facilitate commerce and to encourage longer stays in the malls for increasing sales. Leading new players, such as the Shanghai K11 Art Mall, introduced art infused into a luxury retail strategy by housing an art museum in the heart of a luxury shopping centre, while seeking to engage the rapidly growing number of billionaires in China’s cities, blurring the lines between art and high commerce. Codignola and Rancati (Citation2016) argue that association with contemporary art makes customer perceptions of a luxury band more positive, attracting a wider audience group without diminishing the brand’s aura. For luxury retailers, such as Louis Vuitton, Chanel and Gucci, the frontiers between art and commerce become even more blurred. In the research ‘Consumer Perceptions of How Luxury Brand Stores Become Art Institutions' (Joy Citation2014), which argued that consumers are compliant with retailers in the construction of their own (art) experiences because luxury stores have become contemporary art institutions. In the K11 Art Mall Shanghai, the luxury retail offerings displayed alongside actual art render both equal in value. Employees in the mall sometimes function as curators, offering guidance and knowledge for both retail goods and artwork. Rare and highly priced art is part of the circulation of luxury goods and due to this symbolic nature of art as luxury commodity – the art world has acted to feed this desire, which in return feeds the retail sector in this interactive business relationship. However, it is still insufficient to say that luxury stores can be compared to contemporary art institutions. From my point of view, as a marketing strategy and branding tool, art sponsored in this way evokes particular desires from the consumer, led by art savvy retailers, by enhancing customer experiences with art in a luxury shopping environment. It stresses the collaborative effort between art and business with an expectation of mutual success. Art exhibited in the shopping mall has taken new forms in the context of the curation of contemporary art in China. There might be an effect from these retail strategies that might be influencing how art is being curated and this might also be seen as a space between the function and positioning of the art fair in relation to the art exhibited in the shopping mall.

In order to investigate this phenomenon, and explore how art and business interact together to promote art, the Chi K11 Art Museum has been selected as a case study. Methodologically, this section is mainly developed from semi-structured interviews and a literature review of first and secondary source material, including the definition of key terms, details of past exhibitions, and financial data analysis. In this case study, the examined elements will include: how contemporary art exhibitions and public engagement practices have been driven by business in luxury shopping malls in China and how the curatorial strategy brings art together with real estate business. Additionally, the question of whether artistic intervention in the urban commercial complex resulted in an increased ‘commercialisation’ of art will also be examined in the research.

A blockbuster-centric curatorial strategy

The first exhibition in Mainland China devoted to the works of the iconic French Impressionist Claude Monet was a strange contradiction, with priceless artworks located in the basement of a downtown shopping centre. The exhibition Monet: Master of Impressionism was shown at the Shanghai K11 Art Mall in 2014, and included 40 original Monet artworks – the largest ever show of the Impressionist’s works in the country. During its three-month run, it attracted 400,000 visitors (Jia Citation2015, 129) and thousands of people lined up every day to purchase tickets costing 100 Chinese renminbi and after leaving the show, visitors were able to further purchase Monet themed ephemera, such as framed posters of Water Lilies, at the gift shop.

It is worth mentioning that, in 2014, the Notice of the Ministry of Culture, the State Administration of Cultural Heritage on the Free Opening of Public Facilities to Minors and other Social Groups identified by the Ministry of Culture and National Cultural Heritage Administration actively set cheap entrance prices to public cultural facilities encroaching on the financial operations of institutions and events by the government. Reducing ticket prices has considerable effects on the ability to hold profitable exhibitions in public art museums. Following the promulgation of this specific cultural policy, contractors were no longer able to recover their costs or profit extensively from the cost of holding an art exhibition in a public art museum. Therefore, private art museums became the perfect environment for exhibitions, especially retail-exhibitions mixing art and business. For this exhibition, the K11 shopping mall provided a venue (on the B3 floor) free of charge and took no share of any revenue. Instead, its benefits came mainly from the conversion of exhibition audiences into shopping mall customers. During this exhibition, the turnover of the K11 Art Mall Shanghai increased by 20% (Jia Citation2015, 142) and commercial rents were raised by 70%, generating an income of approximately £4 million. Clearly, K11 found that bringing such artistic marvels to the public sphere rendering shopping more enchanting.

The Monet masterpieces on loan from the Paris Marmottan Monet MuseumFootnote5 included the iconic Water Lily and Wisteria paintings, plus 15 works by other masters, such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Instead of being an exhibition full of obscure research and scholarship, it featured a number of works relevant to everyday life, which K11 made easily accessible by relating them to five keywords ‘friends’, ‘cartoons’, ‘travel’, ‘garden’ and ‘old age’. Claude Monet makes a regular appearance in the top ten of the most popular artists of all time, and the exhibition was undoubtedly a massive success, attracting a huge number of visitors due to the general popularity of the artists. Here, specifically, a blockbuster-curatorial centric strategy can be defined as using people’s undiluted enthusiasm for influential and highly popular artists and professionals in art history.

The solution here for the curators it is to find a midway point between the artist and the public. It is in this approach that an exhibition becomes a meeting-point, not only between art museum and visitors but also between art and the real estate business that will turn the site and exhibition into a living entity of everyday life through a shopping experience. Clearly, staging blockbuster exhibitions with entry fees is one of the most successful ways for institutions to supplement their funding and generate revenue. Only those art exhibitions which inhabit a commercial space are able to fulfil the dual mission of being profitable and acting as an ambassador for the retailer.

When tasked with art dissemination in a commercially charged or complex site, how should curators respond to their surroundings? How should one stage an exhibition in such a place and place, while retaining an accessible connection and a dialogue with a larger audience group? As expressed by John Patrick Leary (Citation2019) in his book Keywords: The New Language of Capitalism, that pointed out the duality of curation in the new environment: ‘Like entrepreneurship and innovation, curating as a business practice presents profit-seeking activities as the pursuit of truth and beauty’. When there are gaps between curatorial responsibilities and general demands – locale, knowledge production and finance – it becomes the duty of the curator to find a balance. Branston (Citation2013) states that ‘curation is one of the strategies helping stores to thrive in this changing environment’ (GCI, July/August 2013). The curator of a shopping mall, such as K11, must rely on a range of avant-garde or world-class artists to realise an exhibition, particularly when a show is destined to be staged on a particular site or meant to fulfil targets with multiple goals.

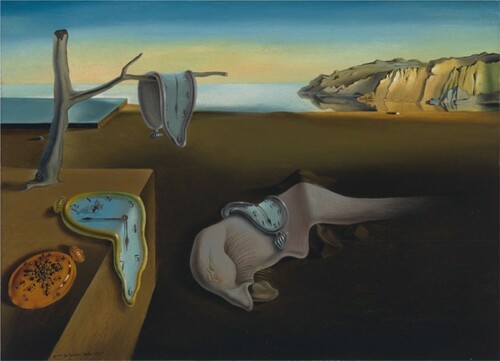

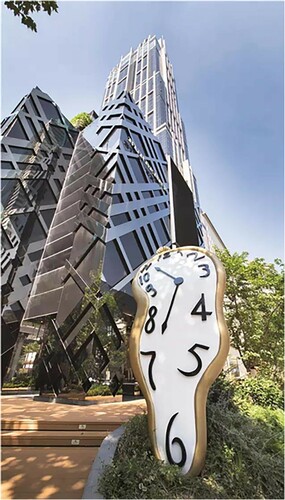

Following the Monet blockbuster of 2014, the curatorial team landed an exhibition featuring works of the iconic Spanish Surrealist artist Salvador Dalí in 2015. The Surrealist exhibition Media-Dalí featured 240 original artworks, media works and some of the artist’s private belongings, and was co-curated and co-produced by K11 and the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation. Central to the exhibition were pieces linking Dalí’s media work with his signature visual language, including elephants, melting clocks and egg-shaped forms, which were positioned both inside and outside the mall.

The melting clocks, as depicted in The Persistence of Memory (1931), became not only one of the most characteristic and original images of Dalí’s visual world but also one of the most recognisable, popular and historically important pieces of modern art in the world (Rothman Citation2012, 9). Rothman (Citation2012, I) said of Salvador Dalí, ‘his love of little things, on the other hand – of things that exist at the boundary of perception and on the edge of cognition – was a love Dalí never abandoned’. The exhibition at the Shanghai K11 responded to the concept that the Dalínian clocks function in radically different ways, linking a wide range of contradictory orientations and perspectives. Dalí expressed his contempt and fondness for the aesthetics of soft and hard objects by employing the melting clock. As shown in , a giant melting clock was set up in the main entrance on Huaihai Road in the downtown area, which became an interweaving structure of urban everyday life and urban living space. Similarly, the main plaza was dominated by sculptural elephants () – a recurring theme in Dalí’s works The Temptation of Saint Anthony and Swans Reflecting Elephants. These extensions of his artwork show a curatorial strategy for bringing aspects of the art into the functional spaces: and as an aestheticisation of the ordinary motifs in these works back into relation to the day-to-day. Whether the artworks or the venue, the contradictions of them became one of themes that echoed throughout the exhibition, from the public square through to the art museum spaces (). As such, the artwork performs dual ‘responsibilities’: both aestheticised and isolated from its original function. As expressed by Stephen Wright (Citation2013), artistic propositions can be described in different ways, it depends on what set of properties (or allure) one wishes to highlight. They can have a double ontology: a primary ontology and a secondary ontology as artistic propositions of that same thing.

Figure 1. Salvador Dalí, The Persistence of Memory (1931), oil on canvas, 24.1 × 33 cm. Photo: courtesy of MoMA.

Figure 2. Sculpture in the outside space (2015), installation view, dimensions variable. Photo: courtesy of the K11 Art Foundation.

Figure 3. Sculptures at the Media-Dalí Surrealist Exhibition (2015), installation view, dimensions variable. Photo: courtesy of the K11 Art Foundation.

Salvador Dalí, a master of self-promotion, was unflinchingly committed to commercial endeavours, something which was echoed in the exhibition’s venue. As explained by the exhibition curator, Montse Aguer:

Dalí was very intelligent. He defined himself as a thinking machine and gave us this image of ‘showman’, but that’s not real. He arrived in the US in the ’40s, while a World War was happening in Europe, thinking this was the centre of the world – ‘I need to self-promote, I need to help audiences approach my art.’ (Arnold Citation2015)

While the majority of art museums in Mainland China use social mediaFootnote6 to promote their exhibitions, the way in which they curate and plan exhibitions appears to be readily and increasingly influenced by social media, in particular WeChat.Footnote7 Directors and curators put emphasis on WeChat Moments, taking into careful consideration the social feed when designing the audience experience. With a billion monthly users, it was inevitable that WeChat would shake up the art world in China – it is changing the way we experience and share our visits to exhibition, and how we perceive art. According to Lefebvre’s dialogue on space, he analyses the discourse on space as a three-part dialectic. Digital space created over the internet and most recently the social media networking which constitute a third area of space. As Hadi and Ellisa (Citation2019) said, ‘information and communication technology (ICTs) is making life easier to connect. Nowadays, ICTs can be used to establish the relationship between the third place and the people, as well as the relationship between the people and the community’. Therefore, the exhibition presented by artist Katharina Grosse becomes understandable that using the Internet and social media to engage with more audiences in the digital era.

Katharina Grosse, the acclaimed German artist, uses a spray gun as her primary painting tool, and featured in five site-specific installations, entitled Mumbling Mud (), in November 2018. Grosse attracts a strong WeChat fanbase to her exhibitions and the show included WeChat-friendly displays to enable the audience to immerse themselves into a 1,600 square feet immersive space. The dissensual order of reality offered photo opportunities to a hungry market, and a great number of fans creatively immersed themselves in Grosse’s works and posted the images on WeChat. In this sense, the social media platform WeChat offered visitors authority and agency in sharing their aesthetic experiences.

Figure 4. Katharina Grosse, Mumbling Mud (2018), mixed media, dimensions variable. Photo: courtesy of JJYPhoto.

This artistic approach emphasises the criticality of material in relation to the city and the space, with Grosse taking piles of dirt, soil, crates, wires, ladders and building materials from the local market in Shanghai and reassembled them within a texturally earthy and raw ‘mud’ installation, which was then covered with colourful paint. The work was subdivided into a five-part installation, curated in a maze of primordial chaos that illuminated a kind of surreal creative wonderland, inviting visitors to discover new aspects of the site at each turn. Integral to this spectacle was the mixing of surrealism and reality with affirming coherence and beauty, as site specificity acting both physically and conceptually.

Showroom, one of the large-scale installations produced on-site in the exhibition, featured coloured swathes of paint that passed across a sofa, bed, bookshelf, tree trunks and variously arranged domestic objects. The intention of the piece was to reconnect the exhibition site to the re-creation of a familiar daily scene with the artist’s signature aesthetic of the use of the spray gun. Amidst the domestic objects, the everyday commonality attached to commodity and the position of art in everyday life became a visualisation of a fundamental ambiguity by the artist fusing the edge of art and that of daily life blurred together. The unresolved clash between the world of painting and the world of lifestyle objects I think posed urgent questions about the position of art in everyday life and everyday life as art.

Grosse (Citation2018) insisted on her ideology in the exhibition and commented: ‘a painting can land anywhere: on an egg, in the crook of the arm, along a train platform, in snow and ice, or on the beach’. The title Mumbling Mud alluded to this fundamental ambiguity: ‘mumbling’ lies at the middle area of quietness, and the blatant ‘mud’ implies somewhere between the fluid and the solid – the intermediate zone. Ultimately, the boundary of site attributes and objects reset the rationality of spatial order through the painterly precipitation performed by the artist. Not only did Grosse create an experience of immersing the familiar in novel ways, but also reworked the established functions and attributes of the shopping mall in which the exhibition spaces were located. The works functioned as a response to the divisions that cut across the art and business worlds.

Stomach (), was another labyrinthine installation in a tactile chasm of colour – performed by over 100 metres of amorphous, coarse cloths twisted and hanging from the ceiling – offered an overwhelming experience in terms of the audience’s perception. Based in a heavily frequented shopping mall in downtown, the work was aesthetically appealing and inherently immersive, and enabled visitors to digest an artistic encounter with their bodies and through physical feelings. The significance of physical experience was further expanded by the artist, with the work enveloping audiences in various structures. It is noticeable, however, that amongst the rising popularity of virtual forms of digital media, human tactility became a neglected part of the art-viewing experience. The installation Stomach invited and immersed audiences, enabling them to wander, physically touch and observe throughout the labyrinthine passage. Through WeChat Moments, audiences were invited to participate in this immersive experience both virtually online and physically on-site ().

Figure 5. Katharina Grosse, Stomach (2018), mixed media, dimensions variable. Photo: courtesy of JJYPhoto.

Figure 6. A screen shot of the WeChat Moment audience sharing the Katharina Grosse exhibition. Photo: photographed by the author.

The dual role of the exhibition space, i.e. having an engaging, immersive, experiential, viewer-centric exhibition, is critical to what the business entity strives to achieve. The National Online Research Study (2017) found that when participants engage in cultural events, such as exhibitions, they prefer to be entertained and able to socially interact rather than be educated or quietly reflective (LaPlaca Cohen Citation2017). In the Chinese context, the use of WeChat Moments reinforces the necessity of the audience’s presence. It brings together a blockbuster exhibition, co-curated by the curator and the artist, with social media to fuel engagement with new audiences. Bourriaud (Citation1998) stated, ‘We can no longer treated contemporary work as a space for experience, but a time of experience, like an opening for unlimited discussion’. In this research, therefore, I define the blockbuster-centric curatorial strategy applied to K11 as a ‘WeChat-friendly’ exhibition, in which audiences take their relationship with WeChat to a new level and can actively curate an exhibit through ‘likes’ on their social feeds. Also, WeChat Moment constitutes another ‘persuasive space’ online to share images, videos and comments from visitors which feeds back into the curatorial language itself.

According to David Fleming (Citation2002), for the purpose of financial viability, museums in part need to meet the needs and interests of educated, middle-class and wealthy people. Cultural elitism can be seen as the gap between the art museums and the masses, and expresses a view that art can only be appreciated in a particular orthodox manner. K11 has shown the potential to bring a new dimension to the relationship between artist, curator and visitor. In the emerging commercial mix-used spaces, such as K11, curators are making use of WeChat to inform how they plan their exhibitions. It is undeniable that this curatorial strategy can help build new audiences and strengthen connections with existing visitors, even with something as simple as providing audiences with opportunities for a good selfie backdrop. Curators strongly believe that the blockbuster strategy combined with the creative marriage of art and marketing is an effective means for real estate businesses to build deeper connections with their consumers and visitors.

Through intervention, the values of art become those of commerce, meaning that real estate developers have more knowledge of how to create bridges between people and the business world. Adrian Cheng stresses that the private art museum investors should consider how they can make money or receive tax extensions in the Chinese context (Wang Citation2017, 168). Furthermore, Adrian Cheng added that:

An audience’s appreciation is always very important. Even though the new generation wants to appreciate art, how can you appreciate art when there is no tradition of going to museums or galleries? Integrate a proper program inside of what we think that will achieve the purposes, right? Expose your democratised art in places where people go. (Wang Citation2017, 167)

A ‘persuasive space’ in the mall

As events and shows that displayed a crossover between luxury brands and art have emerged and evolved, K11 has broken some of the fundamental rules and traditional ideas of what an art museum is supposed to be. Previously, it was commonly accepted that an art museum was an art-led space which included retail outlets to assist with sustainable operation, such as an art store, a coffee shop or canteen. In contrast, the K11 Art Mall acts as a ‘persuasive space’, in which the curators and artists are invited to create projects in relation to the luxury brands based in the mall. Thereby, its role and responsibility have shifted from a space where artworks are exhibited, to a space where they are an advocate for and engage with the luxury brands on sale in the mall. In this new museology, the social range of material culture that the art museum might exhibit has also been expanded, with the aim of showcasing popular culture and the histories of the non-elite social classes, as opposed to focusing solely on the world views of elite culture (Ross Citation2004, 84–85). To reach a wider audience, art museums must knock down the cultural barriers and pay greater attention to community-and visitor-focussed activities (Lawley Citation1992, 38). In this way, artists and artworks introduced new forms and experiences with art in the persuasive space. It was the belief that art makes shopping more eye-catching that made the persuasive space boldly integrated the brand spirit with exhibition topic to attract visitors who with ‘double identities’.

As an iconic British fashion brand, Vivienne Westwood is known for designing with a very distinctive personality of the designer, strengthened by a reputation as an outspoken, quintessentially British style, with a strong set of values. Even though it has now become a global brand, its iconic style and identity have remained firmly rooted in its British heritage. The Vivienne Westwood store in the Shanghai K11 Art Mall opened in 2013, and at the time was the brand’s largest flagship store in the world – with over 6,000 square feet of pure Westwood – before a further two stores were established in Paris and London. Two years later, the world’s first Vivienne Westwood café opened in K11. In terms of business performance, Vivien Westwood made serious inroads into a receptive Chinese market, with 8–10% of the brand’s worldwide sales happening in Mainland China (Rapp Citation2016). Then, in 2016, the Vivienne Westwood brand and the K11 Art Foundation co-curated an exhibition entitled Get A Life! to raise awareness about climate change (discussed in further detail below). The exhibition became a discursive event and its eye-catching visuals persuading visitors to attend, and, with an eye to the future, the brand utilised the store and café in K11 Shanghai as part of an embedded strategy in engaging in this market.

The exhibition at K11 also made an essential statement – that in the future this kind of visitor-as-consumer exhibition, fusing art appreciation and consumption, could become the new normal. When interviewed, the art museum manager, Huang Shengzhi, commented that the role of the art museum – and that of its staff – was becoming challenging, especially when faced with the concept of the visitor as a consumer. Professionals in the field of art museum operations have had to deviate from their previous roles as educators of the public in order to react to emerging demands from both the market and the state (Ross Citation2004). In this new museology context, art museums not only function as public educational spaces; but increasingly, draw attention to the transformation from a collection-centred ethos to one that is visitor-centred, by creating multi-element spaces for customers featuring different cultural landscapes as a process of urban regeneration. Furthermore, exhibitions provide helpful footnotes to consumers’ conceptualisation of retailers; they can perhaps see this collaboration as a mode of ‘persuasive art museum’.

However, before engaging with the Chinese market, ‘negotiation’ with the government in the name of building trust is a compulsory route that international brands need to take. When adapting to Chinese-style ‘negotiations’, an international brand needs to be localised. As a general understanding, marketing ‘localisation’ implies marketing knowledge of cultural and social norms, language, habits, preferences and especially understanding and navigating the prevailing taboos of the target market. Adherence to the party line is one of, if not the key component in making an international brand successful in China. This can be incredibly important in guiding marketing strategies and informing the brand of what not to include in their marketing campaigns. From a Chinese perspective, this means that all content produced within the country should be censored. Therefore, international brands should actively develop adaption strategies to deal with China’s particular political environment.

It is interesting to note that the websites of international fashion brands, such as the English brand Vivienne Westwood, display different content in China and outside of China. When entering the Chinese market digitally, it is important to fully grasp the concept of ‘ideological security’Footnote8 that is put forward by the CCP. This is recognised as the first step in which international fashion and lifestyle brands must negotiate and navigate through the Chinese political context.

Also, Vivienne Westwood has teamed up with Chinese contemporary artists on environmental topics. As briefly introduced earlier, the 2016 exhibition Get A Life! is one example of a project based on the idea of ‘persuasive art’ (). The exhibition – co-curated by Alex Krenn, the head designer of the Westwood fashion house, and the K11 Art Foundation – sought to raise awareness about climate change through six themes, from cutting edge fashion to environmental advocacy. In a joint response to the theme, Vivienne Westwood teamed up with seven contemporary Chinese artists and an artist group to simultaneously create a vision within the same space. The exhibition Monument of the Peach Blossom Valley, which included work by Wu Junyong, Zhang Ruyi, Yu Honglei, Wang Congyi, Nathan Zhou and Zhu Xi, showcased an array of paintings, video works, sculptures and installations. The statement ‘get a life’ of this eco-activist exhibition appealed to people's environmental consciousness about the deterioration of their living conditions, and acted as a call for action to ensure a good life for the next generation whilst raising environmental concerns in China. As a manufacturing superpower, China has the highest global carbon emissions (Gardiner Citation2017); intense pollution and excessive carbon dioxide emissions as a result of and as a glaring conflict between economy and living environment. K11 founder Adrian Cheng stated: ‘Chinese consumers and Chinese stakeholders are very into sustainability, green issues, and how to conserve the world.’ On the Vivienne Westwood exhibition, Cheng (Citation2017) commented: ‘That’s a big paradigm shift, and we are using art and Vivienne’s voice to create that message.’ In fact, there was a massive ready audience of luxury fashion-hungry Chinese shoppers waiting to consume the vast array of eco-conscious projects and products available at the K11 Art Mall.

Figure 7. Vivienne Westwood: Get A Life! (2016), installation views, dimensions variable. Photo: courtesy of the K11 Shanghai.

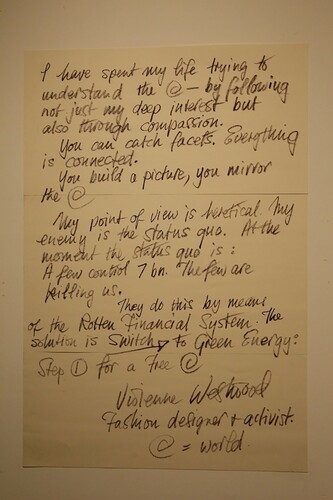

In her usual trademark manner, Westwood lent her outspoken voice to the climate change manifesto by means of handwritten notes to visitors, which are featured in the exhibition. These striking poster-sized, black crayon-scrawled, handwritten messages feature questions and statements, such as ‘Who Are Our Rulers?’, ‘climate revolution’ and ‘hazardous fracking’ alongside images of doves and graphic signs to form the silent scream of her Climate Revolution Charter. One of the photography exhibits, on the theme of ‘Who Are Our Rulers?’, captured Vivien Westwood driving a tank to the home of the British Prime Minister, David Cameron, in an anti-fracking protest on 9 September 2015. Westwood was demonstrating against the fact that the British government had offered licenses for fracking (the controversial method of extracting gas from deep beneath the ground, which is associated with serious water pollution and a cause of minor earthquakes in the UK). This portrait of her – as the pioneer environmental activist – created an influential and persuasive artistic persona whose cause people wanted to join. Get A Life! revealed numerous ironies and encouraged activist trends that have since been adopted in other commercial and pop-orientated activism; here effecting an expression of empathy in relation to a topical subject in a country severely affected by pollution which has helped to stir a mass audience in China.

By targeting the specific Chinese context and employing this in the campaign, Westwood used political and environmental declarations as a medium through which she could make bold statements to bridge the gap between activism and individual consumption, creating affinity and compassion along the way. As the ultimate face of the brand, Westwood explored the persona of an eco-friendly activist building on her desire to make a statement. Westwood states, in a loosely handwritten paragraph on the wall of the exhibition’s entrance:

I have spent my life trying to understand the world – by following not just my deep interest but also through compassion … My point of view is heretical. My enemy is the status quo. At the moment the status quo is: A few control 7bn. The few are killing us. They do this by means of the Rotten Financial System. The solution is to switch to Green Energy ().

Figure 8. Vivienne Westwood, Handwritten Message (2016), paper. Photo: courtesy of the K11 Shanghai.

In this persuasive space, the curator materialises the other side of the designer’s voice, as another art museum experience and a ‘persuasive process’. By the use of simplified slogans such as ‘Live the Arctic’ and ‘Climate Revolution’, Westwood momentarily steps back from her leading role in the punk revolution of the 1970s, to become an ecological activist, creating a loose discursive style but in a materialist way to deliver her fashion aesthetics.

Noticeably, the ‘Buy Less Choose Well’ slogan occurs here, as a reaction to the brand’s reduced clothing line, in order to persuade her fashion followers to buy quality rather than quantity. The Get A Life! theme was a clear attempt to stir a mass audience in the name of environmentalism while also aligning with the idea that the daily activity of life was being connected to in new ways via this shopping experience, which is clearly incompatible between the shopping behaviours and environmentally friendly practices in these ‘persuasive spaces’. As a curation strategy, the environmental theme was used for curating, persuading, and rationalising shopping behaviours, by aligning ethical characteristics to the buying of products. However, the activist intention of the flagship store and coffee shop of Vivienne Westwood in K11 cannot cover up the radical conflict between economy development and serious environmental problem. In this context, ‘What’s good for the planet is good for the economy’ became a paradox and a persuasive philosophy of the brand.

The constant controversy surrounding Westwood may be part of what makes her fashion brand so appealing. In the luxury urban complex of the K11 Art Mall, visitors to the exhibition were defined as potential consumers, and this dual identity poses questions and prompt debates: did the Vivienne Westwood brand act as a vehicle that conflated art museum visitors and fashion consumers with eco-consciousness? Although the connection between the green movement and consumption remains tenuous, environmental awareness is deemed as an effective marketing discourse when faced with youth culture in global conversations (Landbrecht Citation2017). However, while Chinese consumers still have a way to go before they are in a position to make purchasing decisions that reflect eco-consciousness, the Vivienne Westwood brand humbly used an aestheticised vision of environmental consciousness as a platform to build affinity among its followers. Get A Life! promoted discussions about eco-conscious practices and campaigns, whilst activism possesses new buying power that contributes to the brand and commercial growth.

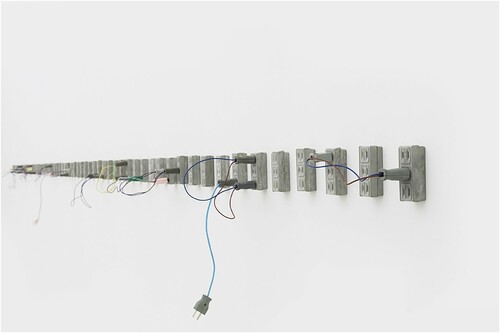

Within the same gallery, further exhibitions have gathered contemporary Chinese artists to respond to the considerations of nature, humanity and climate change – as reflected in Westwood’s fashion-as-activism – in order to foster locally engaged and cross-cultural dialogue. The exhibition not only had K11 presented works by Vivienne Westwood, but contemporary Shanghai artists, Zhang Ruyi and Nathan Zhou were also invited. They constituted the medium of commercialisation of art in the ‘persuasive space’ together. The artworks by Zhang and Zhou initiated dialogue with Vivienne Westwood’s Get A Life! environmental ideas by using environmentally friendly materials, visual metaphorical symbolism and imaginative meaning ().

Figure 9. Zhang Ruyi, Flow Away (2016), installation view, cement, plug, electric coil, dimension variable. Photo: courtesy of the Zhangruyi.com.

Zhang Ruyi reviewed the connection between intangible and tangible objects by bridging them to create the sculpture Flow Away. As a reference to modern society, electrical sockets and plugs linked together to illustrate an aspect of the functioning of the real world. The artist used environmental-friendly materials, second-hand electric plugs and cement to create dozens of old-fashioned sockets. These sockets were lined up on the wall, with some plugs connected in pairs and others hanging free. In my point of view, Zhang’s artwork, based on industrial reality, captures a co-evolutionary fragment of the visible and invisible parts to create an instant ‘pause’ of emotion. In an intangible way, the electricity delivered by the plugs and sockets constitutes how people are reliant on the living environment. In comparison, not only is an intangible message voiced by Vivienne Westwood in a discursive way, but also the material work and activist action are stated in a materialist approach. In a direct link with Westwood’s environmental actions, Zhang suspended electricity as a manifestation of her ambitions to prompt dialogue with Vivienne Westwood’s Get A Life! environmental materialism and beyond.

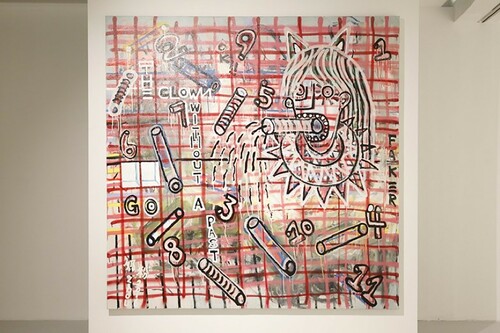

The exhibition also featured another artwork in this ‘persuasive space’, A Clown without a Past, presented by the young Chinese artist Nathan Zhou, who is known for graffiti-esque visuals. Renowned for his impactful colour and intuitive style, the artist layered a number of metaphorical visual symbols, taken from his life experiences, onto the canvas, to depict a space imbued with imaginative meaning (). Zhou’s methodology points to the world, where reality and illusion are united as a painting language by a semiotic category that describes the different levels of interpretation of a message by the audience. Graffiti, images, numbers and his unique language are interwoven into a code that needs to be deciphered. This entwined graffiti and collage technique, which originated from subcultures and underground movements, brims with painting language – echoing the hand-drawn graphics and ecological philosophies featured in Westwood’s Get A Life! exhibition.

Figure 10. Nathan Zhou, A Clown without a Past (2016), acrylic on canvas. Photo: courtesy of the K11 Shanghai.

Ambitious to get in touch with a mass audience (Forbes Citation2018), and convinced of the strength of art, the K11 Art Mall tries to commercialise the art museum experience. In this context, consumers of the shopping mall are equal to the audiences of the art museum. Inevitably, artistic intervention in an urban commercial complex has the potential to result in the increased commercialisation of art. The traditional characteristics of the non-profit organisations, and the roles they have played in society, have been totally changed over the past decade (Ross Citation2004) as they have experienced a ‘commercial transformation’ (Weisbrod Citation1998). K11’s founder, Adrian Cheng, believes that by filling a commercial space with art, customer consumption is enhanced by art engagement. Art is made more accessible to those who are unfamiliar with it, and, in this case, the main characteristics of the art museum space are gradually transformed into the persuasive function in the rapid urban regeneration. Does commercialism ruins art? Must art be separated from commerce to be genuine, or is commerce a catalyst for art and art world? Even though I understand that commercialisation of the art allows individuals and enterprises to dominate the art world, winning great financial benefits when mass commercialism and art mix. But this leads me to the argument put forward by David L.Neumann in his ‘The Commercialization of the Arts', which is still true today. Neumann (Citation1932) stated:

Genius is able to produce its best when working for money. Working for money is a privilege implying that the purchaser values the work sufficiently to be willing to give for it praises more solid than the most enthusiastic critic. Some of the greatest artistic works were produced in periods of very highly developed commercialization. At these times the greatest artists were at once business men and the heads of organized functioning places of business.

Conclusion

As stated throughout the case study examinations, art museums invested in and operated by real estate developers act as a new model of corporate sponsorship via a strategy of reciprocal symbiosis rather than philanthropy without profitability. By considering this collaborative effort between art and business, as well as the relationship developed between corporate and public awareness in China, the concept of ‘art museum retail’ has been developed. From the perspective of a double ontology of the artwork, this research suggests that exhibitions with a blockbuster-centric strategy are effective means for real estate developers to not only evoke desire from consumers but to also enhance customer experiences provided by art savvy retailers. Also, that persuasive strategies have been identified and I describe how art can engage with commerce in the Chinese context: firstly, as artworks that include materials and manifestations that enable them to develop persuasive strategies and where the artist can foster multiple and new forms of persuasive space in the public realm, such as the Katharina Grosse exhibition. Another persuasive strategy, allowing brand spirit and exhibition topic to blend seamlessly, such as the exhibition of Vivienne Westwood. Barber (Citation2011) in describing how artists use persuasive strategy to engage for commercialising art says ‘the modern popular artist does not get bought without his knowledge or complicity, however; he offers herself willingly but signals his originality by making his sell-out into an artistic statement and his statement into a brand’.

As Henri Lefebvre clarifies the idea of abstract spaces in his book The Production of Space,

The same abstract space may serve profit […] Any relationship to things in space implies a relationship to space itself (things in space dissimulate the ‘properties’ of space as such; any space infused with value by a symbol is also a reduced – and homogenised – space). (Lefebvre [Citation1974] Citation1991)

As exhibition locations and curatorial strategies are currently influenced and constantly adapted by ‘art museum retail’, the development of the persuasive space, therefore, has potential to include experimentation and knowledge production. These art museums have influenced different levels of contemporary art and the development of urban culture. Shopping malls contribute to the increased privatisation of public space and the loss of public space (Voyce Citation2006), this trend has even been emphasised as ‘end of public space’ (Low and Smith Citation2006; Mitchell Citation1995; Sorkin Citation1992). Nevertheless, as the most important contemporary leisure activities, it can hardly be denied that shopping is a dominant mode of contemporary public life, and mostly take place in the shopping mall (Goss Citation1993). Also, as found in the research on the commercialisation of art phenomena in the K11 Art Museum, the real estate developer tried to establish a space of artistic intervention utilising approaches of persuasion to effect a mass audience. In this ‘persuasive space’, invested in by the real estate developer, the exhibition, activity and artwork become embodied as the medium of commercialisation of art and art world. The commercialisation of art here can be seen also contribute to a trend in democratising art. In this process, curators, artists and artworks have realigned themselves through the application of persuasive strategies of the business lobby, consumption culture, and business propaganda, which aims to assist the shopping mall retailers in the process of enhanced capitalism. It should also be noted that any democracy of art described here does not develop artistic taste of the mass audience in a direct way. Therefore, the democracy of art is not only a direction taken to cater to mass preferences and tastes, but also seeks to shape these artistic tastes while honours the creation of more favourable conditions to experience art.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nuo Lin

Nuo Lin is a lecturer in Art Management at Xinghai Conservatory of Music. She completed her PhD at the Faculty of Arts, Design and Media, Birmingham City University. Her doctoral study explored the feasibility and sustainability for democratisation of arts that China could promote by the type of art museums established by real estate merchants: how the private museums have been established, operated and sustained alongside the property development in the context of extensive urbanisation in China. Ms. Lin served as media manager in Guangzhou Live3 collaborating with Jonas Stampe. She also participated in a collaborative urban design programme in India. Her research interest is on the sustainable operation of cultural institutions in China. Considering the latest construction fever of private art museum in China, she concentrates on the investigation of the operation methods with local appropriateness.

Notes

1 According to Jeffrey Johnson and Florence (Citation2013), Director of Columbia University’s China Megacities Lab, museumification refers to the

aggressive proliferation of institutions, i.e. the ‘museumification’ of China. It is an aggressive plan to fast-forward the development of the cultural sphere. China plans to elevate the per-capita number of museums to equal international levels. The short-term goal is to have one museum per 250,000 people.

2 The theory aesthetic of everyday life was originally developed by Henri Lefebvre and other Modernist theorists. It refers to the blurring of the boundary between art and everyday life, the collapse of the distinction between high art and mass/popular culture (Baudrillard Citation1983; Featherstone Citation1990). As underlined by Lash (Citation1990, 11), Postmodernism involves a dissolving of the boundaries de-differentiation and the mutual convergence, not only between high and low cultures but also between different culture forms. The effacement of the boundary between art and shopping signals as cultural elements.

3 As the art museums are based on commercial real estate developments, joint ventures between art museums and shopping malls appeared. A space for art intervention, with an art museum retail concept, is a synthesis development model of art and commerce adopted by real estate enterprises in post-industrial cities. These mall museums share common characteristics including spaces, facilities and functions. In order to attract the middle class back to the city centre, mixed-use centres (normally called urban commercial complexes) emerged in western China, blending commercial, cultural and entertainment functions, physically and functionally. La Defense in Paris was the first mixed-use centre in the world, followed successively by Roppongi Tokyo, the Sony Centre Berlin and the K11 Shanghai.

4 Evans (Citation2005, 968) defined culture-led regeneration as ‘culture as catalyst and engine of regeneration’. Referenced by developments in Britain during the 1990s, cultural facilities ‘could be either a preliminary to, or an integral part of, a broader urban regeneration project, usually in the form of a development and reconstruction of part of a city centre’ (Vickery Citation2007, 19). From this point of view, it could be observed that private art museums have been driven by real estate business as a key element for urban regeneration. The aggressive proliferation of art museum establishments, including art galleries, museums and cultural districts, is associated with rapid urbanisation in China, intended to create a cultural infrastructure which meets the same standards as China’s international counterparts (Johnson and Florence Citation2013). As defined in this research, culture-led regeneration means that art museums are fully integrated into an area regeneration strategy; where art museums are a tool to collaborate with real estate development, and are indissoluble from a way of living, shopping and using social space. Culture-led regeneration is increasingly seen as the strategy for achieving economically competitive urban revival, especially in the Chinese context.

5 Paris Marmottan Monet Museum has a collection of over 300 Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings by the artist Claude Monet – the largest collection of Monet’s work in the world.

6 It should be noted that Instagram, Facebook, Twitter are all banned in mainland China. Wechat is the largest social media platform in China now.

7 WeChat is China’s most popular social media, and has more than a billion monthly users. It offers more than just messaging. WeChat Moments serves as a social-networking function on the app, allowing its users to share pictures and videos with all of the user’s friends (similar to Facebook and Instagram). At the same time, users can ‘like’ and ‘comment’ on friends’ posts. Today, WeChat Moments functions as the most common access to information for Chinese people.

8 Tang (Citation2019) argued that ideological security refers to ‘the situation wherein the state’s dominant ideology is relatively secure and free from internal and external threats as well as to the ability to ensure a continuous state of security’.

9 According to the PwC 2021 Global Consumer Insights Survey China report (PwC Citation2021), 72% of Chinese surveyed consumers said they buy from companies that are conscious and supportive and protecting the environment.

10 According to the 2021 Shopping Mall Green Consumption Report (Southern Weekly and New Retail Think Tank Citation2021), the shopping mall is a crucial place for Chinese consumers to make environmentally protective consumption.

References

- Arnold, Frances. 2015. “Sell-Out Surrealism: Dalí at K11.” Smart Shanghai. Accessed April 2021. http://www.smartshanghai.com/articles/activities/sell-out-surrealism-dal-at-k11.

- Barber, Benjamin. 2011. “Patriotism, Autonomy and Subversion: The Role of the Arts in Democratic Change.” Salmagundi 1 (1): 109–130.

- Baudrillard, Jean. 1983. Simulations. New York: Semiotext.

- Bourriaud, Nicolas. 1998. Relational Aesthetics. Dijon: Les Presse Du Reel.

- Branston, A. 2013. “The Rise of ‘Curation’: Product Mix Tailoring Reshaped for Today’s Retail World.” Accessed November 2021. http://www.gcimagazine.com/marketstrends/channels/departmentstores/The-Rise-ofCuration-Product-Mix-Tailoring-Reshaped-for-Todays-Retail-World-205860861.html.

- Cheng, Adrian. 2017. “Vivienne Westwood and K11 Collaborate to Raise Awareness About Climate Change.” Accessed April 2021. https://news.artnet.com/exhibitions/vivienne-westwood-k11-climate-806567.

- Codignola, Federica, and Elisa Rancati. 2016. “The Blending of Luxury Fashion Brands and Contemporary Art: A Global Strategy for Value Creation.” In Handbook of Research on Global Fashion Management and Merchandising, edited by Alessandra Vecchi and Chitra Buckley, 50–76. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Evans, Graeme. 2005. “Measure for Measure: Evaluating the Evidence of Culture's Contribution to Regeneration.” Urban Studies 42 (5/6): 968.

- Featherstone, Mike. 1990. Consumer Culture and Postmodernism. London: Sage.

- Fleming, David. 2002. “Positioning the Museum for Social Inclusion.” In Museums, Society, in Equality, edited by Richard Sandell, 213–224. London: Routledge.

- Forbes, Alexander. 2018. “Adrian Cheng is Building a New Culture for Chinese Millennials—One Art Mall at a Time”. Artsy. Accessed February 2021. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-adrian-chengbuilding-new-culture-chinese-millennials-one-art-mall-time.

- Gardiner, Beth. 2017. “Three Reasons to Believe in China’s Renewable Energy Boom.” National Geographic News. April 2021. https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/05/china-renewables-energyclimate-change-pollution-environment/.

- Goss, Jon. 1993. “The ‘Magic of the Mall’: An Analysis of Form, Function, and Meaning in the Contemporary Retail Built Environment.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 83 (1): 18–47.

- Grosse, Katharina. 2018. “Chi K11 Art Space Presents ‘Katharina Grosse: Mumbling Mud’ in Guangzhou”. CAFA Art Info. Accessed April 2021. http://en.cafa.com.cn/chi-k11-art-space-presents-katharinagrosse-mumbling-mud-in-guangzhou.html.

- Hadi, R. F. P., and E. Ellisa. 2019. “Rethinking Third Place in the Digital Era.” International conference on informatics, technology and engineering, Bali.

- Jia, Bu. 2015. Times of Feature Exhibition: Research on Feature Exhibition Industry in Shanghai 2014-2015. Shanghai: Tongji University Press.

- Johnson, Jeffrey, and Zoe Alexandra Florence. 2013. “The Museumificiation of China.” Leap. Accessed February 2021. http://leapleapleap.com/2013/05/the-museumification-of-china.

- Joy, Annamma. 2014. “Consumer Perceptions of How Luxury Brand Stores Become Art Institutions.” Journal of Retailing 90 (3): 347–364.

- K11. 2017. “About K11: Brand Story.” K11 Corporation. Accessed December 2017. http://hk.k11.com/en/About-K11/About.aspx.

- Kan, Haidong. 2009. “Environment and Health in China: Challenges and Opportunities.” Environmental Health Perspectives 117 (12): 530.

- Landbrecht, Christina. 2017. “Vivienne Westwood: Get a Life!” Journal of Curatorial Studies 6 (2): 279.

- LaPlaca Cohen. 2017. “Culture Track 2017 (National Online Research Study).” LaPlaca Cohen, https://culturetrack.com/.pdf.

- Lash, Scott. 1990. Sociology of Postmodernism. London: Routledge.

- Lawley, I. 1992. “For Whom we Serve.” The New Statesman and Society 17 (7): 38.

- Leary, Patrick J. 2019. Keywords: The New Language of Capitalism. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

- Lefebvre, H. (1974) 1991. The Production of Space. Translated by D. Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Low, Setha, and Neil Smith. 2006. The Politics of Public Space. London: Routledge.

- Manzo, John. 2005. “Social Control and the Management of ‘Personal’ Space in Shopping Malls.” Space & Culture 8 (1): 83–97.

- Mitchell, Don. 1995. “The End of Public Space? People’s Park, Definitions of the Public, and Democracy.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 85 (1): 108–133.

- Neumann, David L. 1932. “The Commercialization of the Arts.” New Mexico Quarterly 2 (3): 224–230.

- PwC. 2021. “2021 Global Consumer Insights Survey China Report.” PwC. Accessed November 2021. https://www.pwccn.com/en/industries/retail-and-consumer/publications/consumer-insightssurvey-2021-china-report.html.

- Rapp, Jessica. 2016. “Vivienne Westwood, K11 Team Up with Chinese Contemporary Artist to Get Consumers Thinking About Climate Change.” Jing Daily. Accessed April 2021. https://jingdaily.com/viviennewestwood-k11-climate-change/.

- Ross, Max. 2004. “Interpreting the New Museology.” Museum and Society 2 (2): 84–100.

- Rothman, Roger. 2012. Tiny Surrealism: Salvador Dali and the Aesthetics of the Small. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Schulze, Gerhard. 1992. Die Erlebnisgesellschaft: Kultursoziologie der Gegenwart. Frankfurt am Main: Campus.

- Sorkin, M. 1992. Variations on a Theme Park: The New America Cities and the End of Public Space. New York: Hill and Wang.

- Southern Weekly and New Retail Think Tank. 2021. “2021 Shopping Mall Green Consumption Report.” Accessed November 2021. https://www.163.com/dy/article/GAP3UMTP05118FFD.html. NetEase.

- Tang, Aijun. 2019. “Ideological Security in the Framework of the Overall National Security Outlook.” Socialism Studies (5): 49–55.

- Vickery, Jonathan. 2007. The Emergence of Culture-led Regeneration: A Policy Concept and its Discontents. Coventry: University of Warwick, Centre for Cultural Policy Studies.

- Voyce, M. 2006. “Shopping Malls in Australia: The End of Public Space and the Rise of ‘Consumerist Citizenship’?” Journal of Sociology 42 (3): 269–286.

- Wang, Shaun. 2017. Snapshot: Independent Investigative Interviews on Chinese Contemporary ‘Private Museums’. Beijing: Beijing Topworld Color Printing.

- Weisbrod, B. A. 1998. To Profit or Not to Profit: The Commercial Transformation of the Nonprofit Sector. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Welsch, Wolfgang. 1996. “Aestheticization Processes: Phenomena, Distinctions and Prospects.” Theory, Culture & Society 13 (1): 1–24.

- Wright, Stephen. 2013. Toward a Lexicon of Usership. Eindhoven: Van Abbemuseum.