ABSTRACT

This article outlines and considers the emergence of (fine art) Experimental Studies at Brighton Polytechnic in 1971, as part of the art school modernisations after the Coldstream Report of 1960. Research, to date, suggests this was the first and maybe the longest-running experimental fine art media course in the UK. The photographic works of artists John Hilliard and Roger Cutforth are discussed as they taught the early years of the course, and Roger Cutforth’s work The Non-Art Project (1970–1971), an offsite project and small black and white photobook gives this article its title. The term non-art, as a category in art history is explored along with Information (Kynaston McShine, MOMA 1970), and both are suggested as an important underpinning for the emergence of Experimental Studies, which became Fine Art Critical Practice (FACP) and was run out to form a general fine art course 2020–2022. The end of the paper looks at a particular FACP student degree show from 2015 which resembles some noteworthy curatorial work of Roger Cutforth from 1971. This visual coincidence is taken as a marker – not of deliberate reference, but of a tradition that can still be used with agency and aesthetic purpose by later generations.

Introduction

This article looks back at the early years of Fine Art Critical Practice (FACP), one of four fine art courses at the University of Brighton. FACP sat alongside Fine Art Painting, Fine Art Sculpture and Fine Art Printmaking. Gathered personal testimony has patched together a narrative of the area of Experimental Studies emerging in 1971 and closing in 2022. What began as a student-claimed ‘clean’ studio, free from open turpentine, wet oil paint, brushes and rags, developed into a separate BA pathway in fine art. ‘What is FACP?’, people asked. Well, it’s not painting, it’s not sculpture and it’s not printmaking was always one possible reply. Turning to new media certainly played a major part in this formation, as did turning away from some traditional distinctions and concerns of modernismFootnote1, see .

Figure 1. Plenary, the first event of the FACP archive research project. Firle, East Sussex, June 2016.

Despite decades of institutional change, successive revalidation exercises and name changes Experimental Studies, Alternative Practice, Critical Fine Art Practice and then FACP, only after 50 years, did FACP give way to restructuring. Research to date suggests that Experimental Studies was one of the first experimental fine art media courses to be established in the UK (Finch Citation2013), it was certainly one of the longest-running. In 2022, the last cohort of Fine Art Critical Studies students graduated and the course merged with Fine Art Sculpture to become a single pathway in fine art.

I have taught fine art at Brighton since the mid-1990s, first in Sculpture, then in FACP, and now in a new course called, simply, Fine Art (Although, that is a misnomer as everyone knows, there is almost nothing of the tradition of the fine arts about the current curriculum). In researching and assembling this narrative my article draws on material uncovered by the FACP Archive Research Project, the main impetus of which came from fine art students in 2014, studying BA FACP at the University of Brighton. A loose coalition of students, ex-students, tutors, ex-tutors and archivists developed the archive to collect course records and testimonials and hold material for further questions on the course’s past. What defines this archiving and collecting is the paucity of the official records of this course and others like it (Salaman Citation2015). Sue Breakell, director of the Design Archives at the University of Brighton, is a co-researcher on the FACP Archive Project, which she writes about in her article ‘Snail trails and alternative momentum: the Fine Art Critical Practice Archive’, also in this volume.

Of the many artists, lecturers and students involved at the start of Experimental Studies, our research to date has yielded interesting information about the particular contribution of two prominent conceptual artists of the time – John Hilliard (born 1945, UK) and Roger Cutforth (1944–2019). Their photographic and moving image work as artists and their approach as teachers at Brighton Polytechnic form a significant area of research for this paper and offer a set of cultural and aesthetic concerns and a recognisable discourse for us today in fine art, laying the groundwork and precedent for certain kinds of art practices and critiques to be included and taken seriously in higher education.

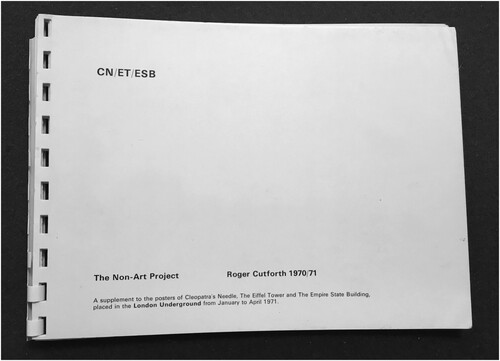

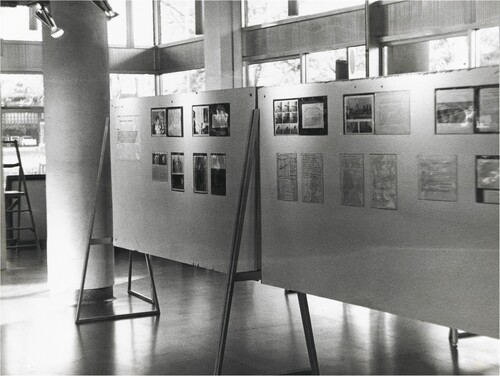

It is Cutforth’s work The Non-Art Project (1970–1971), documented by a small black and white photobook that gives this case study its title. The term non-art, as a category in art history is considered below, as is the paradigmatic exhibition Information, curated by Kynaston Mcshine, at MOMA, New York in 1970. Cutforth participated in Information, and this exhibition taken together with the term non-art seems to offer a context and support for the emergence of Experimental Studies, which persisted over five decades. In the absence of records from these early days, finding evidence of an exhibition Roger Cutforth put together in the foyer of the new art school building on Grand Parade (now called City Campus), has been formative (see ). This image – showing the work of American artist Dan Graham, offers a visual and categorical link to more recent FACP undergraduate work, from 2015, which I bring together to bookend this article.

Figure 2. Roger Cutforth installation photograph Information of recent work of Dan Graham, Brighton Polytechnic, Brighton, England 1970 gelatin silver photograph 16.8 × 22.4 cm (image); 18.1 × 22.4 cm (sheet) National Gallery of Victoria.

Without the institutional history offered by Hilliard in an interview, I would have very little to explore as I offer a brief overview of the changes in the late 1960s and the early 1970s art education in Brighton. Hilliard gave me a first-hand account, having been asked specifically to teach in Experimental Studies because of the work he was then becoming known for. He ran the area until he left for a job in London in the mid-1980s. Hilliard was also able to tell me about the work of Roger Cutforth whose visibility as an artist now is much diminished. I became interested in the term non-art as used by Cutforth. This led me to Thierry DeDuve’s articles on the subject in Artforum (Citation2014) and to Maggie Finch’s research on conceptual art in Australia in the late 1960s and the early 1970s where Cutforth showed his work. Cutforth brought an iteration of both non-art and the exhibition Information into his teaching at Brighton Polytechnic with his ‘displays of information’ (Finch Citation2013). Piecing together the beginnings of a new area of fine art education in Brighton in the early 1970s, I want to suggest the importance of the idea of non-art, current in the early 1970s, and to suggest this idea remained pertinent to the course until it closed in 2022 though more work will need to be done to secure this second claim.

Experimental studies and non-art education

Experimental Studies, as it was first known, emerged at Brighton College of Arts and Crafts out of a sustained period of national, government-funded research, publication, review and implementation of a new qualification in Art, the Diploma in Art and Design (Dip. A.D.), a qualification equal to a BA at a university. The National Advisory Committee on Art Education (NACAE) was set up in 1959, to research and see through the modernisation of art education. It was a public committee chaired by Sir William Coldstream, who with many notable artists and writers of the time, prepared The First Report of the National Advisory Council on Art Education (Citation1960), otherwise known as The Coldstream Report. As a result, art schools around the country were invited to submit new course proposals to the National Council for Diplomas in Art and Design (NCDAD), another committee filled with the great and the good men of culture, also referred to as the Summerson Council after its chair, Sir John Summerson (RIBA). Validation from this committee enabled art schools to receive funding in order to teach and resource the new higher qualification of the Dip. A.D.

In 1962, Brighton College of Art was approved to run the new Dip. A.D. in Fine Art (painting) by the NCDAD, taking in their first students for the new award in September 1963. The graphics course was also approved as was a new course in three-dimensional design in 1965, while ceramics developed an industrial award with a college in Stoke on Trent. The sculpture course, however, did not gain NCDAD approval, though as yet, we do not have research to know why (Lyon and Woodham Citation2009). In 1967, the completion of the new purpose-built art school on Grand Parade provided accommodation for the newly designated department of fine art, in the College of Arts and Craft. Then, in June 1968, in co-ordination with the students at Hornsey, and other art colleges, the college was occupied and large meetings were called by students to demand future student involvement in all levels of decision-making at the college, including in the content of their courses. The students called for art education to be opened to what was happening in the world, to be more up to date with current art and to have access to new media equipment and technology (Salaman Citation2018). Anecdotally the origins of FACP have been linked with the student unrest, but quite how this informed course development is not recorded.

Soon after the Brighton student protests of June 1968, the Department of Education and Science (DES) announced that the art college along with the College of Technology would merge to become Brighton Polytechnic. The art college meanwhile continued its attempt to gain approval for the Dip. A.D. in sculpture (Lyon and Woodham Citation2009). In 1969, the Head of Fine Art, Gwyther Irwin, sought out the British artist John Hilliard to help redraft the course proposal for the Dip. A.D. Sculpture. Hilliard had been a student at St Martins School of Art in London, which, despite the gathering centrality of its New Generation tutors, had, like Brighton, failed to achieve Dip. A.D. status for its sculpture course when it first applied. Frank Martin, head of sculpture at St Martins had appointed Peter Kardia to devise and re-write the course, and in 1964 they succeeded in gaining Dip. A.D. recognition and went on to offer experimental – and soon notorious undergraduate and postgraduate studio courses in Sculpture (Wesley Citation2010). Hilliard was asked to write the proposed sculpture course for Brighton, based on his knowledge and experience of experimental pedagogy and the intellectual range set out by Kardia.Footnote2 This strategy worked, and by the summer of 1970, an undergraduate sculpture course in the newly designated Faculty of Art and Design at Brighton Polytechnic was awarded Dip. A.D. status by the Summerson Committee (NCDAD).

By the time sculpture was validated, it was late in the academic year and in order to run the course in September 1970, places were offered to students who had applied and been rejected from the fine art painting course. Seven students enrolled in the new Sculpture Dip. A.D. and began to work on the projects Hilliard had devised within an experimental/process-based pedagogy. The students sometimes worked blind-folded and a policy of silence was imposed during the making periods, similar to the now infamous Locked Room seminar on the St Martins ‘A’ Course. Projects for students on the new sculpture course in Brighton lasted a week or so and generally had an exploratory dimension and purpose, using an assortment of tools dislocated from their associated materials, craft and application. Hilliard recounts musical instruments and sound being improvised, performance and installation being some of the new directions students explored, with film and photography often documenting experimental actions and journeys.

However, this did not last long. Brighton’s then head of sculpture, James Tower (1919–1988), who was a trained painter but had become a formal ceramicist and sculptor, was not happy with the direction of the new course and made known his preference for more traditional techniques and approaches. At the end of the spring term of 1971, Hilliard was summoned to Gwyther Irwin’s office and told that he would have to resign from Sculpture. Irwin then asked Hilliard if he would teach in the new studio area of fine art developing next to the painting department. As Hilliard was preparing and then delivering the new anti-art sculpture course, a group of students set about organising an anti-art, break-away, ‘clean’ studio space next door to painting, to focus on lens-based work. They wanted access to photographic and film equipment and to investigate current art. So while Hilliard’s own art school experience and institutional expertise helped secure the Dip. A.D. Sculpture award at Brighton was his emerging career as a young experimental artist in photography and film which was sought by the college for the new area of Experimental Studies. The students paved the way for a space for experimental new media art education that Hilliard legitimated with his up-and-coming reputation as an artist. Experimental Studies was not sculpture, was not painting and was not a course, as such, but rather an area of interest and practice that could not be identified in the existing system of fine art education, but, crucially could be recognised in contemporary art.

Hilliard and Cutforth

John Hilliard and Roger Cutforth met at a group show at the Lisson Gallery, London, in the summer of 1971, where they were both showing. The two had much in common. They shared a photographic and moving image practice and an approach to using media as a form of neutral, everyday information. They also found that they would both be teaching at Brighton Polytechnic that coming autumn term, in Experimental Studies. Hilliard brought to this emerging area in the art school a growing reputation as an artist investigating the medium and mechanism of the photographic image at a pivotal moment or crisis in art history and art criticism.Footnote3 His photography work had been quickly picked up as indicative of international conceptual practice, exhibited at Camden Arts Centre in 1969; then the Lisson Gallery, London; Prospect 71, Dusseldorf and The New Art at the Hayward in 1972. His photo work Sixty Seconds of Light (1970) was purchased by the Tate in 1973, one of its earliest acquisitions of photographic conceptualism. Hilliard was still in his twenties. Works such as Sixty Seconds of Light, (1970) and Camera Recording its Own Condition (7 Apertures, 10 Speeds, 2 Mirrors) (1971), employ titles which specify the amount of light, or the length of time the camera shutter was open, with the corresponding test strips shown in series or grids. The titles note what the images are of and how they came about. But at the same time, they bring in aspects of the process of image production that finished photographic images leave out; these works literally document the event of image formation as a self-referential event, an apparatus recording a particular moment rather than a timeless record of light bouncing off an object being focussed through a lens. Other works of this period, such as Through The Valley (1972), consider framing not so much as the edge of composition but a limitation or exclusionary device determining what is not included, what is left out when the camera/lens points in a certain direction or either side of the moment the shutter opens or when the image is cropped for media reproduction. As David Campany writes about these early pieces, ‘Hilliard suspends certainty by undermining a stable relation to the image’ (Campany Citation2003).

Cutforth’s best-known work from this time is Noon Time Piece (April), 1969: a series of 30 colour Polaroids of the sky, straight up, taken from the same place, shown with a calendar of the days the shots were taken, (downtown New York) and map co-ordinates of the site. The different measuring systems all relate to the same space/time that the work records; they have an equivalence or equality of significance. It was this work he showed in the MOMA exhibition Information (McShine Citation1970b), where his associate Joseph Kosuth showed One and Three Chairs (1965). Both works could be understood as part of the drive in conceptual art at that time to bring the image down from its sacred place as the privileged, irreducible centre of transcendental meaning in the visual arts and in art history and bringing text into the artwork as an important register of meaning. Where Kosuth uses a dictionary definition to challenge the visual representation of the chair, Cutforth gives us map co-ordinates and calendar references for the when and the where and also the at-what the polaroid camera points.

While bulky video cameras and recording equipment were emerging technologies that artists were beginning to use in their work, Hilliard and Cutforth were involved with the dominant, everyday visual technology of light-sensitive film inside a dark box. Both their moving image work and their still photographic work used the same camera obscura optical/light-sensitive chemical system. This was the pre-digital era of visual production, a taken-for-granted aspect of the visuality found everywhere in society – images in newspapers, books, advertising, archives, police files, medicine and so forth. Hilliard and Cutforth’s early work used and addressed photography as a non-art image form and as impersonal data. They used the production of photographic information as procedure and practice in their art, borrowing from and playing with scientific surveying, mapping and forensic systems of measurement and evidence gathering. This is not the only approach artists of the time were taking to various recording systems, but it is notably the dominant use of photography in much conceptual art. This placed their work in opposition to art practices based in or understood in terms of gifted self-expression and instead called up the everyday experience of looking at (often mass-produced) images. They both used a medium considered to be not art, to explore an everyday visual form, an everyday encounter – this was not part of post-war modernism or modernist criticism nor was this kind of photography part of the fine art system inherited from the art academy.Footnote4

While Cutforth and Hilliard both used photographic and film media, Cutforth was less critical of the medium of photography itself and more interested in deploying its surveying or mapping, its non-aesthetic traditions and practices to explore philosophical questions concerned with language as the basis of seeing. While in New York in 1969 he formed the short-lived ‘Society for Theoretical Art and Analysis’, with Australian-born artist Ian Burn (1939–1993) and British artist Mel Ramsden (1944), both of whom went on to work with Art & Language in New York (Harrison and Wood Citation2003). Along with other young conceptualists, Cutforth showed in Conceptual Art and Conceptual Aspects (1970) at the New York Cultural Centre, curated by Joseph Kosuth and Ian Burn. He was also invited to show at the Nova Scotia College of Art, Halifax, Canada, in 1971, and featured in Lucy Lippard’s Six Years (Lippard Citation1973, Citation1997). The title for this paper The Non-Art Project is borrowed from a small, black-and-white artist's photobook by Cutforth which Hilliard showed me when I visited him as part of this research. It dates from when Cutforth was asked to teach Experimental Studies at Brighton Polytechnic, fresh from the New York circles of conceptual art (see ).

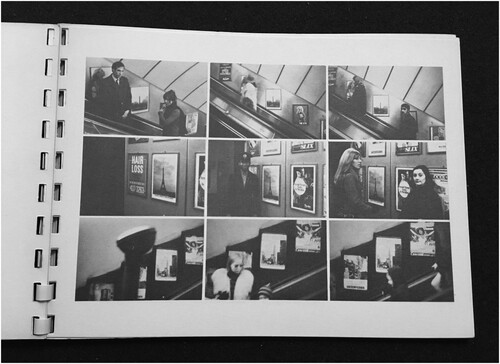

The Non-Art Project (1970/1971) takes the form of a small ring-bound booklet. The text on the front cover proclaims its status as a supplement to a project that took place outside of the gallery. This resonates with the new art practices and categories emerging at the time: off-site, site-specific, land art and systems art all related to conceptual art. All of these terms indicate an absence of the work when the artwork or documentation is shown in a gallery context and the traditional singular object of art, the finished, beautiful object is negated. The non-art booklet documents the photographic work of Cutforth’s; images of three tall monuments – the Eiffel Tower, Cleopatra’s Needle and the Empire State Building, installed temporarily on the walls of the London Underground. Inside pages of the booklet show photographs of these landmark structures side by side with advertising and publicity posters of the same size. London Underground passengers and staff are caught randomly by the candid installation shots as they pass by (see ). As well as documenting a site-specific public project, the booklet itself becomes a non-art art object. It was shown in different iterations in Australia, New York, London and Canada.

Non-art and Information (1970)

Non-art is given a deeper history in Thierry De Duve's Artforum article The Invention of Non-Art (de Duve Citation2014) soon to be out in book-length form. In the first of two articles, she says the terms non-art, anti-art and so on were ‘much in fashion in the art criticism of the 1960s’. He offers a supplementary history to the term – not simply back to Dada, Surrealism and Duchamp and the European avantgarde, but back to the Salon exhibition system in Paris, which, since the nineteenth century (and before) organised a large exhibition of the best academic artworks. The Beaux Arts (and the art academy before it) invited artists to enter a juried competition to determine which works would go on display. Showing at the Salon was important for any artist’s future career. DeDuve suggests that the inclusion/exclusion function of the jury at the Salon, the pinnacle of art education, sponsorship, appreciation and value, combined with the accepted hierarchy of history painting produced a new category of art, a non-art which was considered not good enough or woefully flawed. In 1863 the non-selected artists made such a fuss that a new exhibition was shown alongside the Salon, the Salon de Refusé and amongst these works were later identified key exponents of early modernism, anti-academy art (de Duve Citation2014). As such, these negative prefixes to art, such as non-art could be considered as categories produced by and in art education, exhibition and learning that could themselves contain or describe elements of the new or the avant-garde.

An exhibition which seems less reported on but significant in terms of this emerging context of non-art art, showing artists who like Cutforth and Hilliard had turned away from traditional categories of painting and sculpture and the more rarefied art criticism that attended it, was Information (MOMA 1970).Footnote5 This enormous survey exhibition showed a wide assortment of experimental and conceptual practices that could be seen as paradigmatic of the shifts happening in the art world and bubbling through the counterculture at that time. Information, curated by Kynaston McShine, featured 400 films, image works, performances and publications from over 150 artists, many utilising new communications technology – the Xerox, the fax machine, telephone answer machine, coding and computer language, video tape, jumbo jets – as well as older visual and communications technologies such as printed booklets, printed and written text, magazine inserts, 35 mm photography, Super 8 film, the postal service, topography, surveying techniques, map making and so on. ‘The only common denominator is that all are trying to extend the idea of art beyond traditional categories’ (McShine Citation1970a).

McShine’s curatorial approach was inclusive; some work was provocative and even explicitly political, but the show was nonetheless contained by the institution of MOMA. Hans Haacke, for example, installed a polling booth with an electronic counter, posing the question to visitors; ‘Would the fact that Governor Rockefeller has not denounced President Nixon’s Indochina Policy be a reason for your not voting for him in November?’ This work was direct – with the Vietnam War protests raging while Nelson Rockefeller was the president of MOMA, the museum, he was also an important elected politician. This may have been uncomfortable for MOMA, yet the exhibition ran its course. By contrast, one year later, Haacke’s work Shapolski et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real–Time Social System, as of May 1 1971, (1971), provoked such a crisis at the Guggenheim in New York that Haacke’s retrospective exhibition was cancelled and the curator, Edward Fry was fired. The reason given at the time was that the work was not considered to be art but rather facts. Facts about the behaviour of landlords in New York were not art, they were not welcome and the information was too close for comfort for the existing trustees and corporate elites connected to the museum.Footnote6 Shapolski et al. (1971) was conceived as non-art but it also brought into the gallery the non-art world on its doorstep.

Although the curator of Information, McShine avoided this kind of clash or confrontation with powerful art institutions, he nonetheless did include many artists involved in the counterculture. As he says in a catalogue essay:

The material presented by the artists is considerably varied, and also spirited, if not rebellious, which is not surprising, considering the general social, political and economic crises that are almost universal phenomena of 1970. If you are an artist in Brazil, you know of at least one friend who is being tortured; if you are one in Argentina you probably have had a neighbor who has been in jail for having long hair, or for not being “dressed” properly; and if you are living in the United States, you may fear that you will be shot at, either in the universities, in your bed, or more formally in Indochina. (McShine Citation1970b)

… An intellectual climate that embraces Marcel Duchamp, Ad Reinhardt, Buckminster Fuller, Marshall McLuhan, the I Ching, the Beatles, Claude Levi-Strauss, John Cage, Yves Klein, Herbert Marcusse, Ludwig Wittgenstein and theories of information and leisure inevitably adds to the already complex situation. It is even more enriched by the implications, for example, of Dada, and more recently happenings and Pop and ‘minimal’ art. (McShine Citation1970a)

Information (MOMA 1970) was not a historical survey show where everything was taken safely out of the store and kept in archive conditions as we are accustomed to now when seeing any of this work. This was a survey of artists involved and active in the late 1960s, shown in 1970. Although it was not overtly factional, not obviously connected to one side of the ferocious debates raging or the other, Information (MOMA 1970), nonetheless or perhaps because of its plurality offered a range of new media works and practices that had not, as yet, been taken seriously as art, but which would, at least some of them, soon become known as anti-modernist or anti-aesthetic and so on.Footnote7 This context – this ‘already complex situation’ as McShine calls it above, sees artists critiquing new and older technology, leaving traditional art categories, genres and subjects behind, but not forgotten, while bringing into the art world aspects of the counter culture and new intellectual critiques not yet established in art criticism.

Apparent from our perspective now is the absolute lack of mention of the demands and implications of the women’s liberation movement, and the invisibility of women artists. In a show that numbered 150 participants, I can count only five women in total, and three of them were represented in the catalogue only, not the exhibition. So while the description of the ‘intellectual climate’ that appears in the catalogue essay may resonate with us, it does so without the inclusion of the social movements that we know about from that time, which have over time changed the intellectual climate of the art world, and were already then pressing on America’s streets and universities even if not in a Museum of Modern Art press release, nor the longer essay by McShine, hidden as it was in the Information catalogue (McShine Citation1970a, Citation1970b).

The exhibition catalogue for Information (McShine Citation1970b) and The Non-Art Project 1970/1971 by Cutforth remain good examples of non-art in a number of ways. Firstly, they represent practices coming to prominence at the end of the 1960s already discussed above, secondly, they announce and celebrate not attempting to fit into existing categories of established fine art, or modern art. While consciously negating dominant modernist aesthetics, they are nonetheless, made or represented here for a gallery context, and they became exchanged and exhibited as art fairly quickly. Cutforth’s work here is not by any means unique in its time, this is not the point, rather the work heralds as does the exhibition Information (MOMA, 1970), many aspects of the dematerialisation of the object of art (Lippard Citation1973, Citation1997), which whilst refusing certain categories, such as painting and sculpture, produces new ones in the context of the museum and the art school, and becomes a kind of accepted or at least familiar presence of antagonism. The photograph documenting Cutforth’s curatorial work at Brighton Polytechnic () meanwhile puts much of what McShine notes about the work in Information into practice and into his teaching, in what he calls ‘displays of information’ (Finch Citation2013; McShine Citation1970b).

Displays of Information (1971), Wheely Good Artists (2015)

Cutforth’s close connections with international experimental and conceptual artists became evident in his work at Brighton Polytechnic. He began to organise what he called ‘displays of information’ with artist associates by inviting them to mail him information and images about their work which he organised on notice boards in the foyer of the college (). In a short period, Cutforth displayed information from an impressive list of artists: Dan Graham, Robert Smithson, Ad Rhinehart and Mel Bochner, with more plans that did not materialise. Photographs of these displays came to light as a result of historical research by curator Maggie Finch at The National Gallery of Victoria, on the Australian conceptual artist Ronald Rooney (193717), published in their magazine Art Journal. Finch’s research was sent to me by Dave Cubby, in 2018, as a result of our formalising the FACP Archive Project, and hosting a few events with past students. Cubby was a student at Brighton (1969–1971), one of the art students inventing Experimental Studies, who became a photographer and lecturer resident in Australia. In Rooney’s archive, Finch found letters from Cutforth; they had been in regular correspondence between 1971 and 1978. The photograph, from one such letter, shows a display of works by Dan Graham, sent to Cutforth by post, that Cutforth pinned up, and then photographed to send to Rooney in Australia (1971/1972), inviting Rooney to send his own work.

… … .At a time when such works were not widely distributed beyond their immediate exhibition and reproduction in catalogues with small print runs, the display of work by a leading contemporary artist such as Graham was an extraordinary opportunity to view key international practices. The notion of displaying ‘information’ also demonstrated Cutforth’s understanding of the desire among conceptualists at that time to participate in, and facilitate, a rapid exchange of ideas, to create a dialogue, and to communicate information through networks which, thanks to the largely dematerialised nature of the works, could be both local and international. (Finch Citation2013)

The lack of frames and the simple display system Cutforth used for showing the work – photographs, photocopies, pages, diagrams and serial images pinned to noticeboards has aged well. While evidently from 1971, this work could show up in a contemporary gallery now; it seems fresh and current. These displays are of their time and also read across time in relevance, fit for an informal, conversational teaching or exhibition practice. Sadly, one result of this informality is that records of these shows have not been kept by Brighton University, nor as far as we know, anywhere other than a few photos in an artist’s archive in Australia. As mentioned in the introduction what defines this work of archiving in and for the FACP Archive Project is the scarcity of any trace of its history kept by the institution.Footnote8

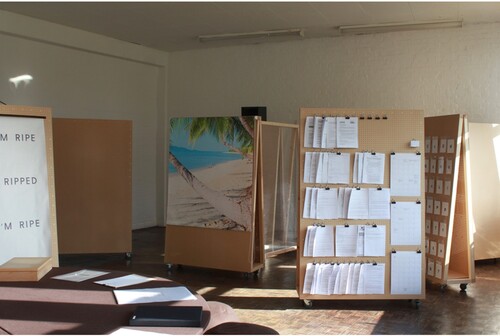

As I studied the photographs of the noticeboard displays set up by Cutforth, I realised a striking resemblance between those triangular structures from 1971 and some recent student studio work from 2015. Tilly Sleven and Lizzy How, who had first proposed a FACP course archive as a studio project in 2014, were active in developing a collaborative design for their final degree show in 2015, called Wheely Good Artists (see ).

Figure 5. Wheely Good Artists FACP Degree Show 2015. Lizzy How presented all the job applications she had written and sent in the time leading up to the degree shows, claiming the letters and the process an artwork. Photo by Naomi Salaman.

This design took the form of wooden framed triangular units, faced with pegboard on both sides, one unit per student. They were on wheels, and could easily be moved or danced around the studio. The triangular display system enabled a degree show to take place that was independent of the studio walls. The design was not so much a sculptural gesture to make objects that were not wall-based as a declaration of separation or independence from the studio and maybe, by extension, of the institution (see ).

Figure 6. Wheely Good Artists FACP Degree Show 2015. Amelia Kidwell ‘The walls of this room watch this happen every year, but this year we are the walls, we are the space, and we are watching’. RIP Tilly Sleven. Photo by Naomi Salaman.

There was a lot of interest in what a support structure consisted of, a pressing question for the cohort of students whose public financial ‘support structures’ had been fully dismantled and rebuilt as individual debt structures.Footnote9 What kind of autonomy was possible without support, and what would an alternative space look like? In this sense, while the studio, the building and the institution itself were housing the student work, the format they built enabled the studio to be seen as a shell. This separation created a consciousness of cycles of repetition, the history and the walls of the space, the studio, the institution and its wider context and change, what had been provided and what has been loaned. The very modular flexibility of these structures was in itself knowing; comic and sad at once (see ).

Figure 7. Wheely Good Artists FACP Degree Show 2015. Molly Maher, above, offered a performance, illustrated with a flip chart of detailed blow-ups taken around the college from odd vantage points. Hers was a psychogeography of the anxious neoliberal educational subject/object split. In her performance, it was never clear who was talking, was it the institution speaking? Or was it a student trying to work out where the institution began and ended, what it knew and did not know in its newly marketised form?

There are many other works in Wheely Good Artists (2015), to mention and other notable FACP group degree shows to discuss, but the point here to emphasise is the visual and categorical coincidence between Cutforth’s 1971 ‘displays of information’ and the design and substance of the 2015 FACP degree show. Certainly, the students had not come across Cutforth’s work, which I only began to research in 2018, so this overlap brings us back to the question and claim of continuity despite the change, that underpins the long-running course. The two display structures are strangely similar, not simply in terms of the formal overlap of the triangular structure and the largely dematerialised practices shown but also that the relations of production implied in both are non-hierarchical and non-professional, based on informal conversations and a temporary community produced and contained by the shell of an educational space and a course provision.

Conclusion

The Information Show, curated by Kynaston McShine at MOMA in 1970 was multifocal, including some deliberately political works that would become known as institutional critique, as well as playful, poetic and conceptual works that brought many forms of technology and many different kinds of objects and subjects into the museum as artworks. In stumbling across this exhibition, through the work of Roger Cutforth, and gathering testimonials from John Hilliard, I now consider Information (1970) a significant exhibition in assembling an art historical context for the FACP course over time. Cutforth’s ‘displays of information’ (1971) can be seen as recognisable objects in this historical discourse, and at the same time as a representative of the early days of the existence of course. These objects are also recognisable from my perspective as a lecturer on the course in its last decade and as a contributor to and researcher of the history of FACP. Of course, there is so much more of this history to fill in. More work of archiving, research and writing up is needed to develop this area, to pin down non-art as art history in the FACP archive, in the course’s history and in the history and accounts of similar experimental courses of that time in the UK.

Experimental Studies developed at the end of the 1960s, at a time of expansion and modernisation of art education in the UK and amidst the counterculture; political upheaval and protest about the war in Vietnam, Civil Rights activism, the Women’s Liberation movement, youth revolt in music, culture, sexuality and gender. Everything has changed since that time. There is the need to take into account the large and oppressive narrative of education cuts and restructuring, which since that time has pressed to reshape arts education right up to our present bleak moment of austerity for all of our public services, education included. It is clear that much of the progressive ground on which a course like this could emerge and be publicly funded as culture and education has fallen away.

What has also changed over this time is the growing awareness of gender, difference and diversity, not only as intellectual and political issues but also as aesthetic and institutional ones. From our research to date – most of the artists and students in the early years of Experimental Studies were white and male. This means that whilst most of the changes in the structure, finance and experimental potential of a course like FACP come as a result of cuts over the last 50 years, the contiguous growth in recognition and value attributed to women artists and women students, BAME artists and students, GBTQI+ artists and students means that the future of Experimental Studies as fine art is far from certain, in a good way.

To collect documents and testimonials from FACP history is meaningful, even if the meaning, or meanings of the continuities and the changes and the tensions between the two are still to be fully teased out. There are many blanks – about who was teaching what to whom, when and what the students did – and trying to fill those blanks is an important reason for developing the FACP Archive Project. Yet these scant records of Experimental Studies have so far yielded vibrant examples of non-art. Further work needs to be done in broadening the art historical and critical bibliography to contextualise non-art discursively in pedagogy and practice. The fact that we can plot the emergence and persistence through time of this area of art education and practice taking place in this particular purpose-built art school building, uncovering material from the past which remains fresh and pertinent today is something to celebrate. We all need something to celebrate.

Photo credits

All photos by N. Salaman, except Steven Connolly, Roger Cutforth installation photograph of Information of recent work of Dan Graham, Brighton Polytechnic, Brighton, England 1971 (thanks to National Gallery of Victoria).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Naomi Salaman

Naomi Salaman is an artist and lecturer. Her work investigates art practice, pedagogy and cultural institutions using historical, critical and feminist perspectives. She has a PhD in Visual Arts Practice, concerning art theory in the art school, called Looking back at the life room, from Goldsmiths College London (2008) supervised by Victor Burgin. She is a senior lecturer on Fine Art at Brighton University and is organising SWEETSHOP, an artist-run window gallery in Lewes, East Sussex, where she lives. https://blogs.brighton.ac.uk/sweetshop/.

Notes

1 The beginnings of the course are discussed by students and staff at a course reunion. First event FACP archive research project, edited audio section, Salaman (Citation2016).

2 The account of John Hilliard's time at Brighton, writing the new Sculpture course and then working on Experimental Studies was given by Hilliard in conversation with the author, 31 October 2018. Some institutional records would be extremely useful here, but nothing has been found, as yet. There has been a growing interest in documenting Kadia’s approach. Hilliard was at pains to say that all this was a long time ago – and of course he did not keep any of the written documents.

3 Jonathan Harris gives a good overview of the elements in the multiple crises going on in art history in the 1970s in New Art History; A Critical Introduction, 2001.

4 There is more to say on the history of photography in the inter war years in Futurism, Surrealism and so on – and then the distinctions created in post war modernism in the USA, where art photography was distinct from modernist art.

5 Compared to say When Attitudes Become Form, curated by Harald Szeemann (1969), Information (1970) has a very low profile. To mention just the best known artists in Information; Vito Acconci, Carl Andre, Keith Arnatt, Art & Language Press, Terry Atkinson, David Bainbridge, John Baldessari, Michael Baldwin, Robert Barry, Bernhard and Hilla Becher, Joseph Beuys, Mel Bochner, Daniel Buren, Victor Burgin, Ian Burn and Mel Ramsden, Hanne Darboven, Walter de Maria, Jan Dibbets, Rafael Ferrer, Barry Flanagan, Group Frontera, Hamish Fulton, Gilbert and George, John Giorno, Dan Graham, Hans Haacke, Michael Heizer, Douglas Huebler, On Kawara, Joseph Kosuth, Christine Kozlov, John Latham, Sol Lewitt, Richard Long, Bruce Mclean, Cildo Meirelles, Robert Morris, N.E. Thing Co. Ltd, Bruce Nauman, Helio Oiticica, Yoko Ono, Panamarenko, Giuseppe Penone, Adrian, Piper, Michelangelo, Pistoletto, Yvonne Rainer, Edward Ruscha, Robert Smithson, Jeff Wall and Lawrence Weiner.

6 Daniel Buren who showed in Information, the following year removed his work from a prestigious show at the Guggenheim, causing another crisis. Together these events are considered, in effect, as Haacke and Buren politicising the gallery space, and launching Institutional Critique, around the time Art &Language formalised their attack on retinal art. See 1971 in Art Since 1900.

7 This is complicated as of course modern art – especially in between the two world wars in Europe – did include new media. But not in post war, cold war, America. See for instance Hall Foster The Anti-easthetic (1985).

8 In contrast the, enormous and impressive tome The Last Art College (Kennedy Citation2012) reconstructs a chronology of visiting artists, projects and exhibitions hosted at Nova Scotia College of Art, from 1968 to 1978. As archival clarity of the provision testify the programme of visiting artists at NSCA was taken very seriously and funded accordingly. The visual records and written transcripts kept of the events that took place are evidence alone that these activities were central to what the school did. The resources for Experimental Studies at Brighton were never as lavish as at Nova Scotia, but there is considerable degree of overlap in terms of artists who passed though both places in the early years of the 1970s. And the teaching of art, whatever that meant, was the framework common to both places.

9 The students had been reading some of the accounts and fragments collected by Céline Condorelli in Support Structures, and in particular an interview with Marc Cousins (Condorelli and Wade Citation2009 Citation2014).

References

- Breakwell, Sue. 2024. “Snail trails and alternative momentum: the Fine Art Critical Practice Archive.” Journal of Visual Arts Practice 23(2): 165–179. doi:10.1080/14702029.2024.2354086.

- Campany, David. 2003. Art and Photogrpahy. London: Phaidon.

- Coldstream, William. 1960. First Report of the National Advisory Council on Art Education, 1960 Great Britain. Ministry of Education.

- Condorelli, Céline, and Gavin Wade. (2009)2014. Support Structures. London: Sternberg Press.

- de Duve, Thierry. 2014. “The Invention of Non-Art; A History.” Artforum, February, March.

- Finch, Maggie. 2013. “Information Exchange; Ronald Rooney and Roger Cutforth.” Art Journal 52. September 24, 2014. https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/information-exchange-robert-rooney-and-roger-cutforth/

- Harrison, Charles, and Paul Wood. 2003. Art in Theory, 1900-2000; an Anthology of Changing Ideas. Oxford: Blackwells.

- Kennedy, Garry Neill. 2012. The Last Art College: Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1968–1978. Cambridge: MIT.

- Lippard, Lucy R. (1973)1997. Six Years: The Dematerialisation the Art Object 1966–1972. London: University of California Press.

- Lyon, Philippa, and Jonathan Woodham. 2009. Art and Design Education at Brighton 1859–2009: From Arts and Manufactures to the Creative and Cultural Industries. Brighton: University of Brighton, CRD.

- McShine, L. Kynaston. 1970a. Information. Press release MoMA 1970. https://assets.moma.org/documents/moma_press-release_326692.pdf.

- McShine, L. Kynaston. 1970b. Information. New York: MoMA 2020 (1970).

- Salaman, Naomi. 2015. “Art Theory - Handmaiden of Neoliberalism?” Journal of Visual Arts Practice 14 (2): 162–173. doi:10.1080/14702029.2015.1060067.

- Salaman, Naomi. 2016. “FACP Archive Research, Edited Audio Section.” https://soundcloud.com/brightonfacultyofarts/fine-art-critical-practice-archive-research.

- Salaman, Naomi. 2018. “We Demand Student Representation on Every Level of the College Management.” May ‘68 Legacies and Futures, May. Symposium University of Brighton.

- Wesley, Hester. 2010. From Floor to Sky: The Experience of the Art School Studio. London: Black.