ABSTRACT

Recent years have seen a significant growth in studies of “remote” and “distanced” forms of military intervention. At present however, few analyses have sought to explore the remote character of interventions beyond Western (especially US&UK) cases despite the fact that regional powers in other parts of the world are increasingly militarily active, particularly in the Middle East. This article seeks to look beyond US and UK cases of remote warfare and explore the remote character of the interventions of Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates in Yemen (2015-to date). Using the notion of “practices” that emphasizes both change and continuity in the performance of remote warfare across different contexts, the article shows how Saudi and UAE remote warfare practices show variation both from the US and UK examples and from each other in terms of strategic logics, tactics and the benefits of remoteness. This focus on practices allows us to move beyond debates about what remote warfare is, and who uses it, and permits a broader discussion about change and continuity in the way remote warfare is implemented.

Introduction

In recent years, a new field of scholarship has developed to explore the “distanced” character of contemporary warfare (Watts and Biegon Citation2017; Biegon and Watts Citation2020; Demmers and Gould Citation2018; Krieg and Rickli Citation2018, Citation2019; McDonald Citation2021; Rauta Citation2021; Riemann and Rossi Citation2021; Trenta Citation2021; Waldman Citation2018; Watts and Biegon Citation2021; CitationBiegon, Rauta & Watts 2021). Part of a body of work in Security/War Studies assessing the changing character of war (Holmqvist-Jonsäter and Coker Citation2010; Strachan and Scheipers Citation2013), this research examines how states’ efforts to influence conflicts abroad whilst minimising their physical presence on the ground. This has resulted in a rich, albeit overlapping, set of new “warfare-type” concepts (e.g. remote, surrogate, liquid and vicarious warfare) seeking to explain this phenomenon. Collectively, these concepts explore interveners’ greater reliance on “remote” or “distanced” tactics including airpower and unmanned ariel vehicles (“drones”), special forces, proxies, security cooperation, and private military companies. A separate, but overlapping, literature has also reignited important debates about the growing phenomenon of proxy-warfare in contemporary conflict (Groh Citation2019; Mumford Citation2013; Rauta Citation2020). While several scholars have begun, as this paper does, to examine the use of this mix of military tactics under the broader label of “remote warfare” (Demmers and Gould Citation2020; Knowles and Watson Citation2018; Watts and Biegon Citation2017; Watson Citation2018), debate remains about the most appropriate term.

However, while there are exceptions (Abbot et al. Citation2018; Krieg and Rickli Citation2019), much of the literature on “remote” forms of warfare has focused on “Anglo-Saxon” US/UK operations (Adelman and Kieran Citation2018; Demmers and Gould Citation2018; Waldman Citation2018; Walker Citation2018; Watts and Biegon Citation2017, Citation2021). Far more attention is warranted to “the rest” however, not least because of a significant recent rise in intervention by regional powers. As Leonard (Citation2016) notes: “While the West is losing its appetite for intervention – particularly involving ground troops – countries like Russia, China, Iran and Saudi Arabia are increasingly intervening in their neighbours’ affairs.” While in a historical sense there is nothing new about these states intervening in their neighbourhoods, the remote character of these regional power’s contemporary military operations is currently underexplored.

This article focuses on one of the most significant interventions in the Middle East in recent years – the Saudi-led coalition’s operations in Yemen. This is an important case as it allows us to explore patterns and postures of remoteness on the part of two powerful and influential aspiring regional powers in the Middle East: Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. While the conflict is sometimes described as an instance of Western remote warfare (Hathon et al. Citation2016), in practice these two key players have shown a high degree of agency and are worthy of study in their own right. They have nonetheless adopted several practices generally considered “remote” within the literature such as an (over)reliance on airpower, special forces deployments, security training and the use of proxies, combined with, at times, conventional military operations. They have, however, demonstrated differences from US/UK remote warfare (and from each other), adopting their own particularised patterns of “remoteness.”

To evaluate the remote character of Saudi-led intervention in Yemen, this paper argues that rather than focus on remote warfare as a distinct category of war, it is more useful to explore “remoteness” in warfare as a set of practices (Adler and Pouliot Citation2011; Bueger and Gadinger Citation2015) that share a common core – a desire to achieve military outcomes without large ground deployments – but that vary in implementation between cases, especially in terms of the policy/strategic objectives, the tactics involved, and the benefits accrued. Starting from a “pragmatist” view of practices that emphasises “change and contingency” in human behaviour, we suggest that focusing on remote warfare as a set of practices allows for an effective analysis of the “continuous tension between the dynamic, continuously changing character of [military remote] practice on the one side, and the identification of stable, regulated patterns, routines, and reproduction [of military practices] on the other” (Bueger and Gadinger Citation2015, 455–6). Such a view both de-essentialises remote warfare (i.e. there is no one single model of “remote warfare” even if there is a common thread that runs through different examples) and aligns with the focus on both change and continuity in the recent literature on the character of warfare (Strachan and Scheipers Citation2013). This opens up the study of remote warfare and shifts the question from “what is remote warfare?” to how do states strategically and tactical apply military remoteness in different contexts?

This viewpoint allows us to make several observations about the remote character of the Saudi/UAE intervention in Yemen. Firstly, both states have adopted “remote warfare” practices, yet at the same time they demonstrate differences from both Western (UK/US) examples, and from each other. The primary Western objective of recent remote operations – counter terrorism – is only a marginal driver. The Saudis have sought to continue a history of involvement in Yemeni conflicts going back generations, albeit in a more offensive way than previously, driven partly by the perceived threat of Iran but also the threat of the Houthis themselves. Riyadh has led the air campaign, worked closely with the Yemeni Government and has largely avoided ground troop deployment into major battles in Southern/Central Yemen but have nonetheless been drawn into a challenging ground conflict with the Houthis in their southern border regions with Yemen. The UAE by contrast has had a more problematic relationship with the internationally recognised Government of Yemen, sponsored and developed local forces (largely outside of Yemeni Government structures) and has also been more ready to proactively use ground forces than Saudi Arabia – albeit for limited periods. Remote forms of military operations have helped both states deal with intrinsic weaknesses (less developed ground forces in Saudi Arabia and smaller armed forces in UAE). They, like Western powers, derive certain legitimacy benefits from operating remotely, but also engage in remoteness to retain a large proportion of ground forces ready for any potential conflict with Iran. Finally, the UAE’s use of local “proxies” allows it to pursue its own security interests and further its wider regional position, contrary to the interests of Saudi Arabia and the Government of Yemen.

The article is divided into three sections. The first sets out current understandings of remote warfare in the literature. The second discusses the notion of practices as a way of analysing change and continuity in the character of remote interventions across different contexts. It also discusses methods. The final section explores, respectively, the objectives of Saudi Arabia and the UAE, their remote tactics/operations in Yemen and the benefits remoteness offers in achieving their wider goals.

Remote warfare: strategic objectives, tactics, benefits

This section describes the concept of remote warfare, explaining how the term is understood, noting its contested nature and highlighted the predominant Western-centric focus of the literature. The latter part of this section describes the strategic continuities inherent to “new” (Western) remote warfare approaches, outlines the central focus on tactics within the literature and sets out of some the perceived benefits of this type of conflict. A similar three-part framework is employed in the analysis of Saudi and Emirati remote warfare to follow.

What is remote warfare?

Since the end of the post 9/11 wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, scholars have explored state efforts to shape security outcomes in conflicts abroad whilst limiting their on-the-ground presence (Watson and McKay Citation2021, 7). Watts and Biegon (Citation2017), for example, have explored how the US has targeted terrorist leaders with drones, boosted security cooperation and conducted special forces raids against Al-Qaeda franchises. Demmers and Gould (Citation2018) have noted how, under the “hunting Kony” coalition, the US Africa Command (AFRICOM) increased its base numbers and operational capabilities in order to monitor and disrupt non-state risks. Similarly, Waldman (Citation2018) has examined how the U.S.-led Operation Inherent Resolve against the Islamic State (IS) was conducted through coalition air operations combined with proxy militias supported by SOFs operating out of fortified forward bases run by private military contractors.

A number of scholars have come to describe to this type of activity as “remote warfare” (Watson and McKay Citation2021; Watts and Biegon Citation2017; Biegon and Watts Citation2020; Demmers and Gould Citation2020). Put simply, remote warfare refers to an approach used by states to “counter threats at a distance” where states seek to avoid the physical and political risks inherent to the deployment of ground troops (Watson and McKay 2020, 7). The term is contested, however, with this wider literature generating a number of rich, but overlapping, war-type concepts. Nevertheless, while there are nuanced differences between them, discussions of “remote,” “liquid” “surrogate” and “vicarious” warfare all describe military approaches that allow states to counter threats without the large deployment of ground troops (Waldman Citation2018; Demmers and Gould Citation2018; Donnellan and Kersley Citation2014; Krieg and Rickli Citation2019; Watts and Biegon Citation2017).

While not exclusively so, the current literature on remote warfare is focused largely on Western states. Watson and McKay (Citation2021, 9) note that “remote warfare has come to define the Western style of military engagement in the first quarter of this century.” Overseas troop deployments became increasingly unpopular within Western states during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars and are today politically risky for politicians (Watson and McKay Citation2021). Despite their differences, Presidents Obama, Trump and Biden have all been united in an aversion to ground troop deployments and (discretionary) “on-the-ground” military operations are equally off-limits for most other Western leaders. In this context, remote forms of operations have been the fall back, offering more flexibility, lower costs, both in money and (Western) lives, and less scrutiny.

There has been far less analysis of remote warfare cases outside of this Western core, however. While Krieg and Rickli (Citation2018, Citation2019) have discussed Iranian surrogate warfare extensively and highlighted examples from Russia and the Gulf States, the strategic objectives, tactical mix and potential benefits of non-US/UK remote warfare remains generally understudied (McKay Citation2021, 241; Knowles and Watson Citation2018; Watson Citation2018; Walker Citation2018; Biegon and Watts Citation2020; Watts and Biegon Citation2021). In one sense this a surprise as the Middle East alone provides numerous examples of seemingly “remote” operations. Israel has resorted increasingly to remote tactics (airstrikes, drone technology, targeted assassinations) in response to the limited success of ground incursions in Palestine and Lebanon (Borg Citation2020, 9–10). Likewise, Iran has extensively used, and continues to use, Shia militias in its neighbouring countries to pursue foreign policy goals for several decades now (Krieg and Rickli Citation2018). Turkey has developed advanced Unmanned Ariel Vehicle capabilities in recent years, deploying this technology in Syria and supporting Azeri use of these techniques against Armenia (Synovitz Citation2020). Despite this activity, remote warfare in the Middle East, including in the Gulf, is under-researched at present (especially from a comparative perspective).

Strategic objectives, tactics and benefits of remote warfare

There is a degree of fundamental continuity in the wider strategic goals to which remote warfare approaches are put by the US and UK. The remote warfare label has been used most notably to describe Western counter terrorism operations such as those against IS (Watson and McKay Citation2021). However, in terms of strategic objectives, the US/UK and other Western states have been continuously engaged in counter terrorism since 9/11. While the (increasingly remote) balance between methods varies, there is a continuity of strategic objectives here. Others (Watson and McKay Citation2021, 9) have described NATO’s Libyan campaign, with its use of airpower, special forces operations and support of proxies, as remote warfare. Whether one sees NATO’s Libya campaign as being driven by humanitarian or regime change motivations, there is continuity here also with the strategic, interventionist goals pursued by the West in the 1990–2000s. McKay (Citation2021, 241) has also noted that remote warfare might provide a model for great powers to complete without coming into direct conflict. Again, while the risk of great power conflict is rising, there is nothing new about great powers using indirect/proxy methods against enemies. Indeed, this was core to the practice of Cold War competition (Groh Citation2019). As such, while the literature on remote warfare has focused largely on (Western) counter terrorism efforts, there is no one single “use case” for remote operations and the ends to which remote operations have been directed reflect historical continuities.

A central focus of the literature on remote warfare has been on the remote tactics employed. Remote and liquid warfare both describe a combination of tactics including drone and air strikes, and deployment of special forces, outsourcing to contractors, and security sector cooperation (Watts and Biegon Citation2017; Demmers and Gould Citation2018). “Vicarious” and “surrogate” warfare both describe similar capabilities used to shift the burden of risk and responsibility to “proxies” or “human and technological surrogates” (Waldman Citation2018, 189), and “terrorist organizations, insurgency groups, transnational movements, mercenaries” (Krieg and Rickli Citation2018, 115). Watson and McKay (Citation2021, 8) start an introductory chapter on remote warfare with a list of tactics thought to constitute remote warfare. While there is no definitive list of which tactics are “remote” (or how many should be used in combination to be “remote”), a defining feature of the literature on remote warfare – and a unifying theme between the different concepts – is a focus on these “distanced tactics.” Many of these are not new (drones and cyber probably have the greatest claim there), but the willingness to use these approaches in combination, and as an alternative to ground troops since the Iraq war, is one of the key features of the remote warfare literature.

Additionally, scholars have identified a number of different benefits states derive from operating remotely. Remote warfare enables (Western) states to manage and shape the international security environment whilst avoiding political and financial risks. Remote approaches build the capacity of foreign partners to address security-related threats and reportedly mimic the “shadow” tactics of enemies to concomitantly evade democratic scrutiny (Donnellan and Kersley Citation2014; Watts and Biegon Citation2017; Demmers and Gould Citation2018; Knowles and Watson Citation2018; Krieg and Rickli Citation2018; Waldman Citation2018). Proponents of surrogate warfare (Krieg and Rickli Citation2018) argue that Russia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have similar motivations to “externalise” the burden of war: “discretion” and “deniability,” which blur lines of responsibility and accountability. Remote warfare, thus serves to limits pressure on leaders, minimise the scrutiny generated by high numbers of casualties and reduces the financial burden of war. It also makes disengaging from conflicts easier as security outcomes are not dependent on ground troop presence.

Practice theory and remote warfare

Having set out key aspects of the remote warfare concept, this section describes the conceptual-methodological approach adopted. Rather than offer a new category of war, this article explores “remote warfare” as a set of politico-military practices. As will be discussed below, seeing remote warfare as a set of practices helps to de-essentialise the notion and paves the way for an exploration of both change and continuity in manifestations of “remoteness.” While the development of categories is an important dimension of social science, categorisation also carries risks. As De Langhe and Fernbach (Citation2019) have argued these include “compression” (i.e. minimising variation within categories), “amplification” (i.e. exaggerating differences between categories) and “fossilization” (categories creating a “fixed worldview” that “give(s) us a sense that this is how things are, rather than how someone decided to organize the world)” (De Langhe and Fernbach Citation2019).

The idea of “practices” draws on a “theoretical approach comprising a vast array of analytical frameworks that privilege practice as a key entry point to the study of world politics” (Adler and Pouliot Citation2011, 5). Practices are “performances” that are “patterned” and “competent,” exhibiting regularities that can be explored over time (Adler and Pouliot Citation2011, 8). This is essential in the study of remote warfare across different contexts: If we see no similarities/regularities between cases, in what sense can we talk of both cases being remote warfare? There must be a common core of regularities in practices that we see to be able to describe different cases as examples of remote warfare. Thinking of practices in this way helps focus on the continuities in military practice across time/space whilst guarding against “amplification” and the exaggeration of differences.

However, there is also a strong “pragmatist” tradition in the study of practices that emphasises the continually changing and contingent nature of practices (Bueger and Gadinger Citation2015, 456). As Bueger and Gadinger (Citation2015, 456) note “practices are repetitive patterns. But they are permanently displacing and shifting.” Theorists of practices must be constantly aware of “the tension between the dynamic, continuously changing character of practice on the one side and the identification of stable regulated patterns, routines, and reproduction on the other” (Bueger and Gadinger Citation2015, 456). Drawing on the Clausewitzian distinction between the nature and character of war, Holmqvist-Jonsäter & Coker (Citation2010, 3) argues that war must be understood through both change and continuity. This, in turn, reflects recent discussions on the ontology of war. As Barkawi and Brighton note (Citation2011, 134) knowing what war is, is difficult. While Barkawi and Brighton fix on “fighting” as being at the centre of war’s ontology, Bousquet et al. (Citation2020, 100) suggest that it is impossible to devise a “primary definition of war” but rather that the study of war requires a “strange, paradoxical and provisional ontology that is consonant with the confounding mutability of war” and that the solution is a form of “martial empiricism” that privileges an understanding of war’s continued “becoming” (Bousquet et al. Citation2020, 100). This position aligns with the view of practices here. Exploring remote warfare as a “practice” allows one to explore the commonalities of praxis in conflict (and thus to learn something about how wars are fought in a given period), whilst simultaneously reflecting both the mutability of war and the fact that that these practices are liable to change. From the point of view of the study of remote warfare, this is an important ontological twist that opens the possibility of identifying “family resemblances” (Collier and Mahon Citation1993, 847–8) in remote conflict patterns across different wars, even if not all attributes are shared between all cases. This in turn opens the space for examination of degrees of similarity and difference and change and continuity between multiple instances of “remoteness.”

Finally, being sensitive to the risks of “fossilization,” this approach provides a foundation for the analysis of cases beyond “the West.” As International Relations seeks to move beyond its Euro-centric roots (a task still largely to be undertaken in the remote warfare context), a practices view of remote warfare helps facilitate the comparison of “Western” and other non-Western regional powers’ military interventions. By stripping the ontology of remote warfare down to its core practices and anticipating change and continuity in the way these manifest, this approach opens space for different patterns of remoteness that may (or may not) vary from Western practice. While generalisations about the interventions of other states cannot be made from the set of cases here (and while we do not assume any binary distinction between Western cases those of “the rest”), moving beyond prominent Western examples of remote intervention yields interesting observations that have the potential to open up a new research agenda on instances of remoteness.

Remote warfare as a strategic practice: a three-part framework

We suggest therefore that remote warfare should be understood as a strategic practice: a patterned set of competent, repeated behaviours used by states to achieve policy effects through forms of military intervention that avoid the use of large-scale ground deployments. While this understanding is extrapolated from the existing literature, the focus on practices shifts attention from what remote warfare is and who does it, to the study of how it is implemented and how these practices vary. If one does not see regularised patterned behaviour overtime that seek to shape the outcome of conflicts through military means, but without resorting to the use of large numbers of ground troops, one is not talking of remote warfare. At the same time, the patterns of behaviour therein, including policy objectives, the specific patterns of tactical behaviour used to achieve these objectives and the consequent benefits accrued are likely to be affected by some degree of both contingency and change across cases. This approach thus supports the idea of comparison on the study of remote warfare (here between Western practice and Saudi/UAE cases and between these cases themselves) and rests on a form “martial empiricism” as described by Bousquet et al. (Citation2020).

This understanding of remote warfare as a strategic practice firstly implies that remote warfare is used in a strategic way i.e. it is purposeful and “competent” and targeted towards some end. Secondly, it implies that there are patterns of repeated (tactical) actions that put are put in place to realise these strategic ends. Finally, this approach, implies that states choose (and continue to choose) this remote approach because it provides them with certain benefits. This in turn leads to three mutually supporting stages of analysis employed in the study below: 1) Exploration of the strategic objectives of intervention – to what ends are states using remote warfare and how does this relate both to their historical and wider patterns of security behaviour and to the behaviours of other states? 2) Analysis of the actual patterns of remote tactics employed – what combinations of distanced behaviour are put into practice and, as before, how do these vary? Finally, 3), examination of the patterns of benefits states derive from these activities. Building on the pragmatist observation of practices one would expect to find both commonalities and divergences in the strategic objectives, configuration of remote tactics and benefits derived between cases over time and space.

Data collection and analysis

Conducting interviews in the region has proven impossible due to Covid-19 restrictions. Consequently, we have employed an “open-source investigations” approach to data collection that rests on the piecing together of different data points to reach research conclusions (Marks Citation2007, 3). The research for this article is based on a wide collection of, and triangulation between different publicly available data sources: 1) international and Gulf-based journalistic pieces; 2) analytical articles on the Yemen conflict written by analysts (many of whom are from Yemen); 3) quantitative data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Database (ACLED); and 4) reports from organisations with access to conflict zones (especially the UN Panel of Experts). While this relies only on what data is “out there” already, it allows one to piece together different sources of data to build up a detailed understanding of Saudi and UAE practice. It also means that the data sources used are transparent and traceable. The data was collected by the authors over a period of months and subjected to a simple coding system relating to the key three-part focus of the framework of analysis on the strategic objectives sought, tactics employed, and benefits derived.

Case selection

There are intrinsic and instrumental reasons for choosing the case of the Yemen crisis. Intrinsic motivations are linked to the value of exploring the case itself, whereas instrumental motivations are connected to the broader insights that can be derived from examining the cases in question (Silverman Citation2005, 127). Intrinsically, the question of remote warfare is understudied in the context of the war in Yemen, despite the significance of this conflict. This article approaches this conflict in a new way and therefore contributes to our wider understanding of the character of intervention in this brutal war. However, instrumentally speaking, as a conflict led by two prominent regionally influential states outside of the Western core of the US/UK, these two cases allow us to examine how practices of remote war shift and are localised in previously understudied contexts (like the Middle East). The juxtaposition of the two cases in the same broader coalition, however, also allows us to highlight differences between very similar cases as regards remote warfare practice. Indeed, it is important to note that patterns of military presence on the ground are not uniform. Both countries have operated in different ways, in different parts of the country and towards different ends at times, including supporting different sides who have clashed with each other (Mukhashaf Citation2019). This reflects an interesting feature of this case study however (and furtherance of the overall argument above regarding the mutability of practices): even within the same coalition we see both convergence and divergence in patterns of remote warfare at times.

Finally, some may question whether Saudi and Emirati remote warfare represents a mere extension of US and UK policy in the region. We would argue against that view. While there is clearly a very close working relationship between US and UK forces and the Saudi and Emirati militaries, both states engage in activities that are fundamentally in their interests, rather than those of Western backers and have taken actions that have gone far beyond what would be necessary to satisfy Western interests in Yemen. Furthermore, if these Western states were trying to direct the Saudis and Emiratis in Yemen they have not been very successful, with both carrying out actions that contravene Western norms and policy in Yemen (and raise political costs for both the UK and US governments). Whether the high death tolls from aerial bombing that have alienated US and UK legislators (NPR 2019; UK Parliament 2016) or the contradictory policies adopted by the UAE and the Saudis and the competition between them, it is evident that both states have a high degree of autonomy from Western backers and from each other. As Biddle et al. (Citation2018, 94) have noted, security assistance often does not equate to partners doing as Western states would like them to.

Remote warfare in Yemen

The empirical section below is analysed in terms of the three-part understanding of remote warfare described previously. The first section sets out Saudi/Emirati strategic objectives in Yemen. The second section outlines the tactics employed by both states. The final section explores the question of the benefits of this military activity.

Strategic objectives of the Saudi-led Coalition’s actions in Yemen

The Saudi-led coalition’s objectives in Yemen are complex, demonstrating elements of continuity with the past and new drivers of action. Broadly speaking, coalition members seek to shape the security dynamics in Yemen and to ensure that forces aligned against them are checked. The conflict in Yemen is less about supporting ideologically like-minded leaders (President Hadi is not ideologically aligned with either the Saudi or UAE governments), but rather about opposing the Houthis (and the Islah party in the UAE’s case) who weaken the perceived security and economic interests of both the Saudis and the UAE in Yemen. On closer inspection however, there are nonetheless differences in the policy objectives of the two states.

It is worth noting that animosity between the Houthis and Saudi Arabia is historically rooted, in part ideologically driven and the current conflict is part of a broader pattern of conflicts over multiple decades. The Yemeni government was engaged in a series of wars against the Houthis from the early 2000s (the Sa’dah Wars) and the Saudis were directly involved in these conflicts, clashing with Houthi fighters in the latter confrontations (Hill Citation2017, 194–5). It is worth stressing therefore the recent intervention is the latest in a pattern of interventions going back decades. Saudi Arabia was a key player in the Yemeni Civil War of 1962–70, somewhat ironically fighting on the side of northern Imamate royalists against the republican side (whereas the Saudis now fight with the republican leadership against Houthis who wish to restore the Imamate). While the pattern of Saudi interest in Yemen has been constant, until the recent war, Saudi policy was more defensive in nature aiming to support a Saudi-led status quo. The more recent incursion however lies in part in a wider pattern of more offensive Saudi interventionism under the current (and less restrained) Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman in the face of an increasingly active Iran and an increasingly less committed US.

A crucial additional dimension to Saudi involvement in Yemen is therefore Iran. Iranian involvement in Yemen is controversial. Nonetheless, as Hill (Citation2017) notes there were widespread fears in the region in 2015 that Iran was providing military support to the Houthis. Furthermore, the war in Yemen pitting the Houthis who are Zaidi (a branch of Islam closer to the Shi’ism practiced in Iran) against an opposing Sunni coalition plays directly into the narrative of competition between Sunni and Shia – and Gulf states and Iran – in the wider region. The Saudis and UAE both share a strong desire to avoid Iran developing a foothold in Yemen which would prove a direct threat to them. Iran represents a state threat to both the UAE and the Saudis, but the Iranian revolutionary model (shared in part with the Houthis who have their own revolutionary tradition described below) also presents a normative threat to governments who reject revolutionary Islamist politics (of a Shia or Sunni kind).

Indeed, the Houthis present a challenge to the Saudi leadership, expounding a Zaidi-inspired ideology of revolution “khuruj” against unjust rulers which contrasts significantly with the politically “quietest” form of Salafism favoured by Riyadh. This rhetoric is threatening to the Kingdom (especially given its large restive Shia population) and Houthi territorial claims to southern parts of Saudi Arabia (as part of a “Greater Yemen”) that were ceded to the latter after the Treaty of Ta’if in 1934 (Hill Citation2017, 286; Al-Iryani Citation2020). As Al-Iryani (Citation2020) notes, an emboldened Houthi power to their south could thus put pressure on internal divisions within Saudi Arabia.

In addition to its shared opposition to Iran and the Houthis, analysts suggest that the UAE’s engagement in Yemen reflects a growing assertiveness in foreign policy. The UAE is interested in securing influence in southern and eastern Yemen and the Yemeni island of Socotra as a means of projection into the sea lanes around the Arabian Peninsula allowing for influence over sea routes from the Arabian/Persian Gulf round to the Red Sea (Aboudouh Citation2020). This is in part to deter threats from Iran but also to protect against any future threat from Yemen itself (Younes Citation2019). This has been bolstered by growing UAE presence on the other side of the Red Sea at the al Abbas naval and air base in Djibouti (Mello and Knights Citation2016). Likewise, Riyadh has similar interests in eastern Yemen and the governorate of al-Mahra in particular where Saudi control would permit a possible pipeline from Saudi Arabia to the Arabia Sea/Indian Ocean, bypassing the Gulf and the Iranian threat (Aboudouh Citation2020). It has also been suggested, reflecting a parallel with the most common Western remote warfare strategic goals, that the UAE is also involved in Yemen in order to show its usefulness in counter terrorism to the US via-a-vis other players in the region such as Qatar (Younes Citation2019). In addition to airstrikes in Yemen against al Qaeda, the UAE has also trained up local militias to tackle jihadists in Yemen (Jalal Citation2020).

Reflecting a wider pattern of confrontation, the UAE also opposes the Muslim Brotherhood and has sought to limit the influence of the Islah Party in Yemen (formally an ally of the Yemeni Government) which has a pro-Muslim Brotherhood wing. The appointment of General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, an Islah ally, as Vice-President was likely a turning point for UAE policy towards the Yemeni Government (Jalal Citation2020). He was commander of Northern Yemeni forces in the 1994 Yemeni Civil War and commander of Yemeni Government Forces during the Sa’dah Wars in the 2000s (Delozier Citation2018). Close to Saudi Arabia, some have suggested he may be a future president, something which is an anathema to Southern separatists (because of his role in the Civil War) and the UAE alike (due to his support for Islah and Islamists in general) (Delozier Citation2018). This dimension of UAE policy has risen in importance as the conflict has gone on and lies behind the UAE’s support for Southern separatist forces who oppose the Yemeni Government and who can be used to check the influence of Islah. The UAE even launched airstrikes against the Yemeni Government in recent clashes with Southern separatists – highlighting the level of support for the latter (Delozier Citation2018).

Tactical practices of remoteness in the military operations of the Saudi-led Coalition

One of the most prominent elements of the Coalition’s involvement in Yemen has been its air campaign. The Saudis have flown the largest number of sorties and provided the bulk of aircraft for operations (Knights and Almeida Knights and Almeida, Citation2015a). The initial phases of the campaign were targeted at gaining air supremacy and freedom of air manoeuvre for Coalition airplanes, targeting concentrations of Houthi forces, missile sites and controlled ports (Knights and Almeida Knights and Almeida, Citation2015a). The coalition announced the end of the original operation “Decisive Storm” in April 2015, but the air campaign has continued in practice under the “Operation Restoring Hope” mission, which has been heavily criticised due to high civilian casualties (Reuters Citation2015a).

Overtime, the Saudis developed a two-pronged air campaign. The first supports Saudi troops in clashes with Houthis in the border areas of Saudi Arabia/Yemen (Knights Knights, Citation2018a). Here Saudi forces are engaged in combat with Houthis, who have used the rocky terrain to launch border raids into Saudi Arabia and to stage missile attacks against Saudi targets. The Saudis have also used air strikes to attack Houthi targets and assets (missile launchers, etc.) across Yemen (Knights Knights, Citation2018a). Given its role as the birthplace of the Houthi movement and place on the border of Saudi Arabia, Sa’dah Province in northern Yemen has borne the brunt of the air campaign, seeing twice as many airstrikes as the second and third most-bombed provinces (Sana’a and Taiz).

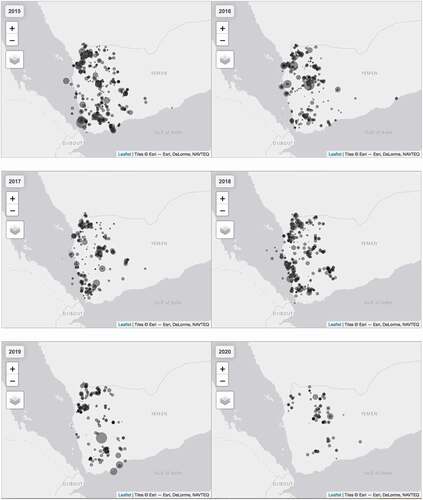

highlights Coalition airstrikes recorded by ACLED between 2015 and 2020. It maps the strikes in the far south in 2015 as the Coalition (including UAE troops) recaptured southern towns from the Houthis, the concentration of strikes in the north throughout the conflict (centred on Sa’dah province) and the increase in strikes between 2017 and 2018 as the Coalition/Yemeni forces sought to gain control of the Western coast.

Figure 1. The Evolution of the Bombing Campaign in Yemen 2015–20 (dots refer to instances of strikes weighted by fatalities). Authors’ own elaboration; Data from ACLED

The UAE has also demonstrated patterns of tactical remoteness. While the UAE has played a significant air role against the Houthis in the Red Sea and alongside US forces against Al Qaeda in Yemen (Knights Knights, Citation2018a), the Emiratis have merged their use of ground troops – see below – with significant support to local actors on the ground. While these include some foreign mercenaries (Hager and Mazzetti Citation2015), the UAE has worked primarily with local Yemeni forces such as the “Security Belt Forces” and “Hadramawt Elite Forces” in Mukalla, the “Shabwani Elite forces” in Shabwah, the “Abu al Abbas Forces” and the West Coast Fighters (Knights Knights, Citation2018b; UN , Citation2020a, 71). While these forces are nominally under Government of Yemen authority, in practice they appear to have operated under UAE control with the Emiratis providing salaries, training and varying degrees of operational command and control (UN , Citation2020a, 71). The lack of direct control over these groups is acknowledged by the Government of Yemen and a major source of tension (Yemen Embassy D.C. Citation2019).

While the Saudis do support a proxy force of Yemenis fighting against the Houthis in Northern Yemen on the border with Saudi Arabia (UN , Citation2020a), overall, the Saudi Government has generally relied more on and worked through the Government of Yemen and President Hadi, rather than set up independent forces outside of Government control. The Government of Yemen forces, while not a direct proxy of the Saudis, do rely substantially on Saudi Arabia for weapons, military support and salaries, and the allegiance of fighters is often highly personalised (UN , Citation2020a).

An additional area of remote activity is the use of UAVs. The UAE and Saudi Arabia have both used UAVs in support of their operations in Yemen. This includes the targeted assassination of Saleh al Sammad, the President of the Houthis Supreme Political Council in Hudaydah in April 2018 (Shaif and Watling Citation2018). Reported evidence of downed Coalition UAVs (capable of both reconnaissance and carrying munitions) has also been released by pro-Houthi news agency al-Masirah (Al-Masirah Citation2020; Middle East Monitor Citation2019).

(A Restricted) Coalition presence on the ground

Despite the large scale of air attacks conducted, the Saudis and the rest of the Coalition have learned (as Western powers have done) that “remote” practices alone are often insufficient to change dynamics on the ground (Schmitz Citation2015). The Saudis have refrained from deploying large numbers of ground troops into combat in Southern Yemen – confining their deployments to the border between Yemen and Saudi Arabia and to other areas of Yemen with limited violence (such as the eastern province of al Mahra – Al-Sewari and Bailey Citation2019). Rather, throughout much of Yemen, in a move similar to Western actors in Syria and Iraq (Votel and Keravuori Citation2018, 42–44) and consistent with strategic remote warfare practice, the Saudis have continued to leave much of the ground fighting to others (principally Yemenis, but also Coalition members the UAE and Sudan). The Saudis appear to have refrained from deploying large numbers of troops on the ground into the most important battles and key junctures of the war such as the battles for Aden, Hudaydah and Taiz (Al-Madhaji Citation2020).

However, this is not the case for the mountainous border region between northern Yemen and southern Saudi Arabia where Riyadh has been involved in direct clashes with Houthis. Much of this has taken place in Saudi Arabia, following cross-border incursions by Houthi forces. In 2019, the Houthis claimed to have killed 500 Saudi soldiers in the border areas (Wintour Citation2019). The numbers are likely inflated, but the clash indicated that the non-remote dimensions of Saudi fighting are intense at times.

The UAE for its part has played a notable, but still restricted, role on the ground in Yemen. The UAE has deployed ground troops (up to 3500 in Yemen), but only for limited periods (Knights Knights, Citation2018b). This included, by mid-2015, a brigade of regular soldiers, SOF teams and a battalion-sized contingent of armoured vehicles including Leclerc tanks and infantry fighting vehicles (Knights and Almeida Knights and Almeida, Citation2015b). The UAE has also employed ground forces directly in the fighting. For example, UAE forces played a key role in the recapture of Aden from Houthi forces in 2015 (Binnie Citation2015). After Yemeni Government forces were pushed largely out of Aden in 2015 by the Houthis, UAE special forces and UAE trained Yemeni forces led the recapture of the city supported by Saudi and Pakistani drones and Saudi and Egyptian naval gunfire (Knights and Almeida Knights and Almeida, Citation2015b). These efforts were later reinforced by the conventional troops and armour described above. Likewise, the UAE played a role on the ground in the recapture of Mocha from the Houthis and in the battle of Hudaydah in 2018 (among others) (Jalal Citation2020; Nissenbaum and Stancati Citation2018). These troops, while strategically consequential, were dwarfed by the numbers of Yemenis fighting however. In April 2020, the UAE announced the completion of its exit plan from Yemen and a reduction in its direct military involvement in the country. This suggests a less direct engagement going forward, but not necessarily less influence given the UAE’s training of more than 90,000 Yemenis (El Yaakoubi Citation2019; Jalal Citation2020).

Another member of the coalition – Sudan – has also played an important role on the ground in Yemen. As Saudi Arabia has sought to avoid major deployments of ground troops (and the risk to its soldiers), it has relied on deployments of other coalition members, including those from Sudan, who have been present particularly in the north and west of Yemen, but also in other parts of the country as well (Kirkpatrick Citation2018). In 2018, the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen noted that Sudanese troops were reportedly deployed on the Red Sea coast in the Hudaydah area (UN , Citation2018b). Many of these fighters are reportedly from the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary counterinsurgency force notorious for its treatment of civilians in the Darfur region of Sudan. These troops operated in place of Saudi troops but came under Saudi command and control. Journalist David Kirkpatrick (Citation2018) interviewed some returned Sudanese fighters who noted that “The Saudis told us what to do through the telephones and devices” and that “They never fought with us.”

The benefits of remote practices

These remote warfare practices offer benefits in terms of realising both governments’ strategic objectives. From Riyadh’s point of view, the use of high-tech airpower plays to Saudi strengths as an extremely wealthy country with an advanced air force, but relatively small ground forces (McDowall et al. Citation2016). The Saudis are one of the world’s biggest defence spenders, with advanced equipment including Eurofighter Typhoons and American F15 jets (Brimelow Citation2017). However, that does not imply that the air campaign has gone well. The campaign has numerous accusations of indiscriminate attacks on civilian targets (McDowall et al. Citation2016). The Saudis have also required extensive support from the US and UK. Nonetheless, acting remotely is a type of fighting that plays to their relative technological strengths. There are thus parallels with Western states who also possess a technological edge in this area.

Importantly, with the use of non-state proxies and the training and financing of state forces involved the coalition, the Saudis can offset the risk of high casualties. The Yemen conflict is not denied, nor is it deniable, given the regular fighting in the south of Saudi Arabia and the repeated rocket attacks on the Kingdom. Using remote practices, however, allows for the Saudis to conduct the war without the delegitimising effect of losing troops. From a different angle, the Houthis often play on the lack of Saudi ground troops in Yemen, highlighting how Yemenis are on the front lines, framing this as both an example of Saudi weakness and morally unacceptable. Their audience is different however, as they are principally speaking to Yemenis rather than the Saudi population (Younes Citation2019).

A remote stance by Saudi Arabia is also thought to have been less likely to trigger a backlash than a ground invasion. One driver of remoteness perhaps overlooked in the literature on Western “remote war” has been the fact that ground-based incursions trigger resistance. The Saudis also felt that an invasion of Yemen by Saudi troops would be counterproductive, fuelling claims of Saudi expansionism and territorial ambitions (McDowall et al. Citation2016). Furthermore, “outsourcing” also allows the Saudis to avoid the fact that their ground armed forces are generally considered to be underprepared to engage effectively in the kind of fighting seen in Yemen. The Saudi military is geared up for high intensity conventional warfare not counter-guerrilla operations (Brimelow Citation2017). The Saudis also do not have an advanced special forces capability (unlike the UAE) which is crucial for this type of conflict (Hill and Shiban Citation2016, 20).

For the UAE, the picture is somewhat different in terms of the performance of its forces. As the UAE forces are capable in this type of war, they have been deployed to the extent they have been because of their ability to support an anti-guerrilla conflict of the type seen in Yemen. As Knights (Knights, Citation2018b) notes:

the UAE has planned dozens of major combat operations in Yemen, including urban warfare, amphibious landings, armoured pursuit operations, precision strike operations with NATO-standard consideration of humanitarian law and non-combatant immunity, stabilisation and reconstruction operations, and unconventional warfare in support of local proxies.

The benefit of remote and limited activity for the UAE comes, not because of capability issues, but because the UAE’s forces are small and therefore large-scale operations would not be possible. Here there are parallels with smaller European Western powers who have relatively small numbers of deployable forces.

A remote involvement in Yemen also presents reputational/legitimation benefits for Abu Dhabi. The As elsewhere, the UAE’s remote operations limit the exposure to troop deaths. However, it should be noted that the government has highlighted the country’s role in Yemen as a means of boosting internal legitimacy and national pride. The outsized performance of Emirati forces is a source of pride for the UAE Government. Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Vice-President and Prime Minister of the UAE and Ruler of Dubai took to twitter in February 2020 to laud soldiers returning from Yemen as “the sons of the homeland” and “the protectors of the union” (Khaleej Times Citation2020).

Remote practices – especially its extensive network of proxies – also allows the UAE to exercise influence towards its coalition “partners” without having to come into direct armed conflict with them (notwithstanding the airstrikes on Yemeni Government forces). Jalal (Citation2020) argues that the UAE can still realise its strategic objectives in Yemen despite drawing down its forces in 2019 precisely because of its continued influence over proxies. These local proxies (combined with other areas of Saudi reliance) allow the UAE to contest Saudi decisions in Yemen and retain access to Yemeni facilities necessary for Abu Dhabi’s regional geo-strategic ambitions (Harb Citation2019).

Finally, for both the UAE and the Saudis, remote practices offer the ability to retain major ground forces ready for any potential threat from Iran. While both states perceive an Iranian threat in Yemen, they have major concerns over the possibility of direct conflict with Iran. This is especially the case since the US has weakened its support for Gulf States under both Obama and Trump. The risk of a conflict with Iran has been cited as a reason for the UAE’s decision to redeploy forces from Yemen in 2019 (El Yaakoubi and Barrington Citation2019).

Conclusion

Over recent years new work on “remote warfare” has enriched our understanding of recent (Western involvement in) conflicts. This article has sought to build on this scholarship, moving beyond the remote interventions of Anglo-Saxon powers, to look at a case of intervention by increasingly military active states in the Gulf: Saudi Arabia and the UAE. In an effort to de-essentialise “remoteness,” this article has explored remoteness as a set of strategic practices – patterned, competent behaviours designed to achieve policy outcomes through military means, without relying on large-scale use of ground forces. Building on practice theory (and the notions of continuity and change therein) it explored the objectives, tactics and benefits of remote warfare in these cases, contrasting them both to Western examples and each other. This approach does not offer a neat binary between remote and non-remote (or “standard”) interventions, but rather permits a nuanced framework of analysis to study the overlaps and differences between remote warfare practices.

In both cases we see clear evidence of attempts to shape military outcomes, whilst limiting ground commitments. While both states have deployed ground troops, for largely defensive reasons in the case of the Saudis and a force multiplier and for command and control in the case of the UAE, both states have sought to rely principally on remote means. In a broad sense this reflects the practice of Western states who have deployed small numbers of ground troops in Iraq/Syria, for example, but relied largely on remote operations. The Saudi border deployments also highlight however the limits of remote-only approaches, especially when conducted in close proximity to home territory.

In terms of strategic objectives, the goals of the Saudis and UAE are not primarily counter-terrorism related nor based on humanitarian motivations, but rather are driven by shared security threats in the form of Iran and the Houthis. At a more fundamental level, like Western states, the use of remote operations demonstrates continuities with past military practice, especially for Saudi Arabia – a longstanding intervener in Yemen affairs. That said, more offensive actions by both the UAE and Saudis reflect recent more ambitious and more aggressive foreign policy shifts on the part of both states (especially the UAE), in the face of a rising Iran and perceptions of changing power balances in the region.

In terms of tactics, one sees a range of actions described in the literature on remote warfare: air campaign, special forces, “drones,” security cooperation, and the extensive “use” of state (Yemeni and Sudanese) and non-state proxies. The balance is different however between the UAE and the Saudis with the latter working more through the air campaign and the Yemeni government, whereas the UAE has proven more ready to deploy soldiers proactively into combat and keen to work extensively with proxies outside of government structures. Such circumstances are not unheard of in Western interventions (c.f. US and UK backing both the Iraq government and Kurdish militias). However, the UAE backing of groups in Yemen in direct conflict with the Government is a significant difference in degree, if not entirely in kind.

Operating remotely presents benefits, reducing exposure to high death tolls among soldiers and playing to Saudi/UAE strengths as cash-rich but troop-poor countries. In the UAE, the government has sought to draw legitimacy from its soldiers’ efforts in Yemen. Neither state wanted to be seen as an occupying force or pulled into a difficult ground war, just as both saw specific military risks in a ground deployment. Remote tactics also mean that both states can keep forces in reserve in case of a major conflagration with Iran (a factor less apparent for Western states, but that might become more prominent if competition with China continues to rise). For the UAE especially, remote intervention in the form of their extensive training and funding of proxies has also permitted a form of inter-coalitional competition with Saudi Arabia and provided an opportunity to assert themselves.

Overall, Saudi and UAE remoteness in Yemen presents an interesting, but complex pattern of similarities and differences with other examples of remote warfare. Employing a practices-based approach helps to focus on the forms of strategic continuity witnessed, whilst also permitting exploration of the local specificities of Saudi and UAE remote warfare. The study of remote warfare outside of Western cases is still in its infancy. While this article has sought to make a contribution here, it is clear that more research is needed, not only comparing Middle Eastern practices to the Western examples that have spawned this literature, but perhaps even more importantly to each other. Indeed, the UAE-Saudi intercoalitional differences between are equally as interesting as the differences between these two and previous examples of remote warfare. More analysis here would significantly further our understanding of remote warfare and the character of conflict in the Middle East more generally.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbot, C., M. Clarke, and S. Hickie 2018. “Remote Warfare and the Boko Haram Insurgency.” Oxford Research Group Accessed 24 August 2020. https://www.oxfordresearchgroup.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=5a9c97dc-cf3e-4e4b-93ac-5ab8b306984c

- Aboudouh, A. 2020. “The Saudi and UAE Cold War in Yemen Will Only Intensify – Even with the Recent Show of Unity.” The Independent Accessed 20 August 2020, April 29. https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/yemen-war-aden-saudi-arabia-uae-separatists-government-stc-a9490546.html

- Adelman, R. A., and D. Kieran. 2018. “Re-Conceptualizing Cultures of Remote Warfare: Editors’ Introduction.” Journal of War & Culture Studies 11 (1): 1–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17526272.2017.1416764.

- Adler, E., and V. Pouliot. 2011. International Practices (Cambridge Studies in International Relations). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Al-Iryani, A. 2020. “Serious Risks in Saudi Options for Leaving Yemen Sana’a Centre.” Sana’a Centre Accessed 24 August 2020, June 5. https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/10147

- Al-Madhaji, M. 2020. “Taiz at the Intersection of the Yemen War.” Sana’a Centre Accessed 20 August 2020, March 26. https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/9450

- Al-Masirah. 2020. “Scenes of Downing, Saudi Operated Spy Drone, Karayel in Hodeidah Sky Accessed 24 August 2020.” https://english.almasirah.net/details.php?es_id=10553&cat_id=1

- Al-Sewari, Y., and R. Bailey 2019. “Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From Isolation to the Eye of a Geopolitical Storm.” Sana’a Centre Accessed 24 August 2020, July 5. https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7606#fn58

- Barkawi, T., and S. Brighton. 2011. “Powers of War: Fighting, Knowledge, and Critique.” International Political Sociology 5 (2): 126–143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-5687.2011.00125.x.

- Biddle, S, J Macdonald, and R. Baker. 2018. “Small Footprint, Small Payoff: The Military Effectiveness of Security Force Assistance.” Journal of Strategic Studies 41 (1–2): 89–142. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2017.1307745.

- Biegon, R., and T. Watts. 2020. “When Ends Trump Means: Continuity versus Change in US Counterterrorism Policy.” Global Affairs 6 (1): 37–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2020.1734956.

- Biegon, Rauta, & Watts. 2021. “Remote Warfare – Buzzword or Buzzkill?”, Defence Studies, Online First

- Binnie, J. 2015. “Emirati Armoured Brigade Spearheads Aden Breakout.” Middle East Transparent Accessed 22 August 2020, August, 7. https://middleeasttransparent.com/en/emirati-armoured-brigade-spearheads-aden-breakout/

- Borg, S. 2020. “Assembling Israeli Drone Warfare: Loitering Surveillance and Operational Sustainability.” Security Dialogue. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010620956796.

- Bousquet, A., J. Grove, and N. Shah. 2020. “Becoming War: Towards a Martial Empiricism.” Security Dialogue 51 (2–3): 99–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010619895660.

- Brimelow, B. 2017. “Saudi Arabia Has the Best Military Equipment Money Can Buy — But It’s Still Not a Threat to Iran.” Business Insider Accessed 24 August 2020, December 16. https://www.businessinsider.com/saudi-arabia-iran-yemen-military-proxy-war-2017-12?r=US&IR=T

- Bueger, C., and F. Gadinger. 2015. “The Play of International Practice.” International Studies Quarterly 59 (3): 449–460. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12202.

- Collier, D., and J. E. Mahon. 1993. “Conceptual ‘Stretching’ Revisited: Adapting Categories in Comparative Analysis.” American Political Science Review 87 (4): 845–855. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2938818.

- De Langhe, B., and P. Fernbach 2019. “The Dangers of Categorical Thinking.” Harvard Business Review Accessed 19 August 2020. https://hbr.org/2019/09/the-dangers-of-categorical-thinking

- Delozier, E. 2018. “Yemen’s Second-in-Command May Have a Second Coming.” The Washington Institute Accessed 22 August 2020, November 9. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/yemens-second-in-command-may-have-a-second-coming

- Demmers, J., and L. Gould. 2018. “An Assemblage Approach to Liquid Warfare: AFRICOM and the ‘Hunt’ for Joseph Kony.” Security Dialogue 49 (5): 364–381. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010618777890.

- Demmers, J., and L. Gould 2020. “The Remote Warfare Paradox: Democracies, Risk Aversion and Military Engagement.” E-IR Accessed 20 August 2020, June 20. https://www.e-ir.info/2020/06/20/the-remote-warfare-paradox-democracies-risk-aversion-and-military-engagement/

- Donnellan, C., and E. Kersley 2014. “New Ways of War: Is Remote Control Warfare Effective?” State Watch Accessed 20 August 2020, October. https://www.statewatch.org/media/documents/news/2014/oct/Remote-Control-Digest.pdf

- El Yaakoubi, A. 2019. “UAE Troop Drawdown in Yemen Was Agreed with Saudi Arabia: Official.” Reuters Accessed 17 August 2020, July 8. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-emirates/uae-troop-drawdown-in-yemen-was-agreed-with-saudi-arabia-official-idUSKCN1U31WZ

- El Yaakoubi, A., and L. Barrington 2019. “Exclusive: UAE Scales down Military Presence in Yemen as Gulf Tensions Flare.” Reuters Accessed 19 August 2020, June 28. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-exclusive/exclusive-uae-scales-down-military-presence-in-yemen-as-gulf-tensions-flare-idUSKCN1TT14B

- Groh, T. 2019. Proxy War, The Least Bad Option. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Hager, E.B., and M. Mazzetti 2015. “Emirates Secretly Sends Colombian Mercenaries to Yemen Fight.” The New York Times Accessed 20 August 2020, November 25. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/26/world/middleeast/emirates-secretly-sends-colombian-mercenaries-to-fight-in-yemen.html?_r=0

- Harb, I. 2019. “Why the United Arab Emirates Is Abandoning Saudi Arabia in Yemen.” Foreign Policy Accessed 15 July 2020, August 1. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/08/01/why-the-united-arab-emirates-is-abandoning-saudi-arabia-in-yemen/

- Hathon, S., S. Hickie, M. Clarke, and C. Abbott 2016. “Remote-control Warfare Briefing #16, June 2016: Increasing Awareness of Risks of Cyber Conflict, Saudi-led Coalition Forces in Yemen Receive US Special Forces Support, Islamic State-linked Group Urges Militants to Secure Their Communications.” Open Briefing Accessed 17 July 2020, June 16. https://www.openbriefing.org/publications/intelligence-briefings/remote-control-warfare-briefing-16-june-2016-increasing-awareness-of-risks-of-cyber-conflict-saudi-led-coalition-forces-in-yemen-receive-us-special-forces-support-islamic-state-linked-group-urges/

- Hill, G., and B. Shiban 2016. “Yemen: ‘A Battle for the Future.’” Oxford Research Group Accessed 20 August 2020, October. https://www.oxfordresearchgroup.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=5c97dda9-912a-4f70-9acd-ed7daa9bb23d

- Hill, G. 2017. Yemen Endures: Civil War, Saudi Adventurism and the Future of Arabia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Holmqvist-Jonsäter, C., and C. Coker. 2010. The Character of War in the 21st Century. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Jalal, I. 2020. “The UAE May Have Withdrawn from Yemen, but Its Influence Remains Strong.” Middle East Institute Accessed 20 August 2020, February 25. https://www.mei.edu/publications/uae-may-have-withdrawn-yemen-its-influence-remains-strong

- Khaleej Times. 2020. “UAE Leaders Welcome Armed Forces Returning from Yemen.” Khaleej Times Accessed 20 August 2020, February 9. https://www.khaleejtimes.com/news/government/uae-leaders-pay-tribute-to-soldiers-returning-from-yemen–

- Kirkpatrick, D. 2018. “On the Front Line of the Saudi War in Yemen: Child Soldiers from Darfur.” The New York Times Accessed 5 August 2020, December 28. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/28/world/africa/saudi-sudan-yemen-child-fighters.html

- Knights, M. 2018a. “Setting Limits on the Saudi Air Campaign in Yemen.” The Washington Institute Accessed 15 August 2020, August 16. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/setting-limits-on-the-saudi-air-campaign-in-yemen

- Knights, M. 2018b. “Lessons from the UAE War in Yemen.” Lawfare Blog Accessed 15 August 2020, August 18. https://www.lawfareblog.com/lessons-uae-war-yemen

- Knights, M., and A. Almeida 2015a. “The Saudi-UAE War Effort in Yemen (Part 2): The Air Campaign.” The Washington Institute Accessed 15 August 2020, August 11. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/the-saudi-uae-war-effort-in-yemen-part-2-the-air-campaign

- Knights, M., and A. Almeida 2015b. “The Saudi-UAE War Effort in Yemen (Part 1): Operation Golden Arrow in Aden.” The Washington Institute Accessed 15 August 2020, August 10. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/the-saudi-uae-war-effort-in-yemen-part-1-operation-golden-arrow-in-aden

- Knowles, E., and A. Watson 2018. “Remote Warfare: Lessons Learned from Contemporary Theatres.” Oxford Research Group Accessed 18 July 2020. https://www.oxfordresearchgroup.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=4026f48e-df60-458b-a318-2a3eb4522ae7

- Krieg, A., and J. Rickli. 2018. “Surrogate Warfare: The Art of War in the 21st Century?” Defence Studies 18 (2): 113–130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2018.1429218.

- Krieg, A., and J. Rickli. 2019. Surrogate Warfare: The Transformation of War in the Twenty-First Century. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Leonard, M. 2016. “The New Interventionists.” European Council on Foreign Relations Accessed 20 July 2020, March 15. https://www.ecfr.eu/article/commentary_the_new_interventionists_6025

- Marks, G. 2007. “Introduction: Triangulation and the Square-root Law.” Electoral Studies 26 (1): 1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2006.03.009.

- McDonald. 2021. “Remote Warfare and the Legitimacy of Military Capabilities”, Defence Studies, Online First

- McDowall, A., P. Stewart, and D. Rohde 2016. “Yemen’s Guerrilla War Tests Military Ambitions of Big-spending Saudis.” Reuters Accessed 20 August 2020, April 19. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/saudi-military/

- McKay, A. 2021. “Conclusion: Remote Warfare in an Age of Distancing and Great Powers.” In Remote Warfare: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by McKay, Alasdair, Abigail Watson, and Megan Karlshøj-Pedersen, 234–251. Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing.

- Mello, A., and M. Knights 2016. “West Suez for the United Arab Emirates.” War on the Rocks Accessed 20 August 2020, September 2. https://warontherocks.com/2016/09/west-of-suez-for-the-united-arab-emirates/

- Middle East Monitor. 2019. “Houthis: Third Saudi Coalition Spy Drone Downed within 24 Hours.” MEMO Accessed 20 August 2020, December 31. https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20191231-houthis-third-saudi-coalition-spy-drone-downed-within-24-hours/

- Mukhashaf, M. 2019. “UAE Carries Out Air Strikes against Yemen Government Forces to Support Separatists.” Reuters Accessed 20 August 2020, August 29. https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-yemen-security/uae-carries-out-air-strikes-against-yemen-government-forces-to-support-separatists-idUKKCN1VJ16T

- Mumford, A. 2013. “Proxy Warfare and the Future of Conflict.” The RUSI Journal 158 (2): 40–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2013.787733.

- Nissenbaum, D., and M. Stancati 2018. “Yemeni Forces, Backed by Saudi-Led Coalition, Launch Assault on Country’s Main Port.” The Wall Street Journal Accessed 19 August 2020, June 13. https://www.wsj.com/articles/yemeni-forces-backed-by-saudi-led-coalition-launch-assault-on-countrys-main-port-1528870659

- Rauta, V. 2021. “A Conceptual Critique of ‘Remote Warfare’”, Defence Studies, Online First

- Rauta, V. 2020. “Framers, Founders, and Reformers: Three Generations of Proxy War Research.” Contemporary Security Policy. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2020.1800240.

- Reuters. 2015. “Saudi-led Coalition Announces End to Yemen Operation.” Reuters Accessed 20 August 2020, April 21. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-saudi/saudi-led-coalition-announces-end-to-yemen-operation-idUSKBN0NC24T20150421

- Reuters. 2019. “Saudi Arabia Boosts Troop Levels in South Yemen as Tensions Rise.” Reuters Accessed 20 August 2020, September 3. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security/saudi-arabia-boosts-troop-levels-in-south-yemen-as-tensions-rise-idUSKCN1VO1FA

- Riemann and Rossi. 2021. “Remote Warfare as ‘Security of Being’: Reading Security Force Assistance as an Ontological Security Routine”, Defence Studies, Online First

- Schmitz, C. 2015. “Misadventures in Violence in Yemen: Operation Resolute Storm.” Middle East Institute Accessed 20 August 2020, April 1. https://www.mei.edu/publications/misadventures-violence-yemen-operation-resolute-storm

- Shaif, R., and J. Watling 2018. “How the UAE’s Chinese-made Drone Is Changing the War in Yemen.” Foreign Policy Accessed 19 August 2020, April 27. https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/04/27/drone-wars-how-the-uaes-chinese-made-drone-is-changing-the-war-in-yemen/

- Silverman, D. 2005. Doing Qualitative Research. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Strachan, H., and S. Scheipers. 2013. “Introduction: The Changing Character of War Strachan, H., and Scheipers, S.” In The Changing Character of War. Oxford: Oxford University Press 1–25 .

- Synovitz, R. 2020. “Technology, Tactics, And Turkish Advice Lead Azerbaijan To Victory In Nagorno-Karabakh.” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Accessed 15 December 2020, November 13. https://www.rferl.org/a/technology-tactics-and-turkish-advice-lead-azerbaijan-to-victory-in-nagorno-karabakh/30949158.html

- Trenta. 2021. “Remote Killing? Remoteness, Covertness, and the US Government’s Involvement in Assassination”, Defence Studies, Online First

- UN. 2018b. “Letter Dated 26 January 2018 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen Mandated by Security Council Resolution 2342 (2017) Addressed to the President of the Security Council.” United Nations Accessed 25 August 2020, January 26. https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_2018_68.pdf

- UN. 2020a. “Letter Dated 27 January 2020 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen Addressed to the President of the Security Council.” United Nations Accessed 25 August 2020, January 27. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/%5BEN%5DLetter%20dated%2027%20January%202020%20from%20the%20Panel%20of%20Experts%20on%20Yemen%20addressed%20to%20the%20President%20of%20the%20Security%20Council%20-%20Final%20report%20of%20the%20Panel%20of%20Experts%20on%20Yemen%20%28S-2020-70%29.pdf

- Votel, J., and E.R. Keravuori. 2018. “The By-with-through Operational Approach.” Joint Forces Quarterly 89: 40–47.

- Waldman, T. 2018. “Vicarious Warfare: The Counterproductive Consequences of Modern American Military Practice.” Contemporary Security Policy 39 (2): 181–205. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2017.1393201.

- Walker, D. M. 2018. “American Military Culture and the Strategic Seduction of Remote Warfare.” Journal of War & Culture Studies 11 (1): 5–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17526272.2017.1416763.

- Watson, A. 2018. “The Perils of Remote Warfare.” The Strategy Bridge Accessed 25 July 2020, December 5. https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2018/12/5/the-perils-of-remote-warfare-finding-a-political-settlement-with-counter-terrorism-in-the-driving-seat

- Watson, A., and A. McKay. 2021. “Remote Warfare: A Critical Introduction.” In Remote Warfare Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by McKay, Alasdair, Abigail Watson, and Megan Karlshøj-Pedersen, 7–34. Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing.

- Watts, T., and R. Biegon 2017. “Defining Remote Warfare: Security Cooperation Briefing Number 1.” Oxford Research Group Accessed 25 July 2020. https://www.oxfordresearchgroup.org.uk/defining-remote-warfare-security-cooperation

- Watts, T., and R. Biegon 2021. “Revisiting the Remoteness of Remote Warfare: US Military Intervention in Libya during Obama’s Presidency”, Defence Studies, Online First

- Wintour, P. 2019. “Houthis Claim to Have Killed 500 Saudi Soldiers in Major Attack.” The Guardian Accessed 20 August 2020, September 29. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/sep/29/houthis-claim-killed-hundreds-saudi-soldiers-captured-thousands

- Yemen Embassy D.C. 2019. Twitter Accessed 20 August 2020, August, 30. https://twitter.com/YemenEmbassy_DC/status/1167565009850916865

- Younes, A. 2019. “Analysis: The Divergent Saudi-UAE Strategies in Yemen.” Al Jazeera Accessed 20 August 2020, August 31. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/08/analysis-divergent-saudi-uae-strategies-yemen-190830121530210.html