ABSTRACT

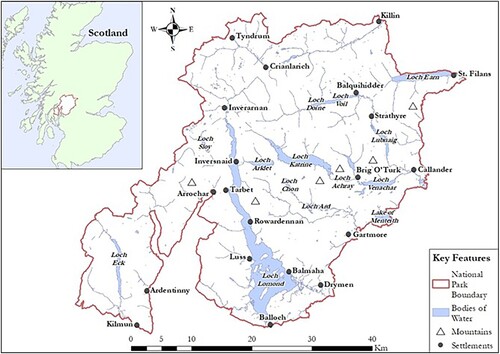

This study spatially analyses aesthetic terms in historical travel accounts of the landscapes of Loch Lomond and the Trossachs from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. We applied a hybrid approach, combining qualitative methods of textual analysis with quantitative techniques of a Geographical Information System (GIS), to a corpus of 38 digitised works featuring a range of historic guidebooks and travelogues. To identify relationships between place names, landscape features and the aesthetic terms beautiful, magnificent, picturesque, romantic and sublime, we first analysed how these terms occurred together in the text. We also used digital terrain model data in GIS to explore relationships between the aesthetic terms and the elevation of place names and landscape features. The results provide evidence that the aesthetic terms magnificent and sublime were applied to describe places and landforms at higher elevations, whilst beautiful, picturesque and romantic were applied to lower-lying regions of the Loch Lomond and the Trossachs landscapes. Our findings illustrate how the cartographic capabilities of GIS, combined with text analysis, can shed light on how landscapes were historically represented in travel literature.

Introduction

Scotland and its landscapes are of high touristic interests and millions of visitors, domestic and international, are contributing to the tourist industry both pre- and post-pandemic (Allan et al., Citation2022). The development of tourism in Scotland is closely linked with landscape appreciation and how Scottish landscapes are experienced, seen, talked and written about (Bohls, Citation2015; Grenier, Citation2005b; McCracken Fletcher, Citation2018). In turn, we can learn about how landscapes are appreciated by investigating how people write about their experience in visiting those landscapes, providing a glimpse into past landscape aesthetic experience and historical cultural landscape values. In this study, we focus on what today is known as the Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park. As Scotland’s first National Park, it is considered to be rich in cultural, economic and ecological value, with a long history of touristic appeal and travel writings that started to emerge in the eighteenth century (Durie, Citation2003; Grenier, Citation2005b).

This study utilises historical travel writing for exploring how written narratives use aesthetic terminology to communicate landscape aesthetic experiences. Through employing both qualitative and quantitative research methodologies and building a corpus of publications which spans four centuries (from 1771 to 1934), this research seeks to characterise how Loch Lomond and the Trossachs was historically constructed, perceived, and aesthetically represented in travel literature. Specifically, this study applies the methodology described by Donaldson et al. (Citation2017b) using GIS to spatially contextualise key aesthetic terms that are commonly associated with landscape appreciation in historic writing. Namely, the aesthetic terms beautiful, magnificent, picturesque, sublime (Donaldson et al., Citation2017b) and romantic (Jones et al., Citation2022) are analysed to explore the relation between aesthetic diction and named locations, featured and landforms. In doing so, we aim to address the following research questions for our study area of Loch Lomond and The Trossachs:

What is the relationship between landscape aesthetic terms in a corpus of travel writing and the named locations and geographical features/landforms they are associated with?

What is the relationship between the topographical elevation of named locations/geographical features/landforms and aesthetic terminology they are associated with?

In the following, we present a brief overview over the links between tourism and travel writing, as well as methodologies to analyse such writings and landscape terminology in the research areas of digital and spatial humanities and literary GIS.

Background

Landscape aesthetics and the development of tourism in Scotland

In Scotland, perceptions of landscapes underwent a mass socio-cultural paradigm shift at the turn of the eighteenth century. Regions that were once seen as wild, hostile, foreign and frightening places became cast as worthy of aesthetic appreciation and exploration (Grenier, Citation2005b). Consequently, Scotland saw an increase in visitors in the eighteenth century linked to picturesque travel by people who were interested in exploring lesser known, scenic parts of Britain who described their travels and routes taken, such as Dorothy Wordsworth, Thomas Pennant, James Boswell, and others (Bohls, Citation2015; Grenier, Citation2005b). The travel accounts these authors published in turn provided the foundations for an increased interest in Scotland, at a time when the wars during the French Revolution and Napoleon forced venturesome travellers to avoid the European continent (Grenier, Citation2005a). Brown (Citation2012) further notes the influence of the 1746 Disarming Act that aimed at removing symbols of Highland and Gaelic culture, including the carrying of arms that aimed at pacifying the Gàidhealtachd regions of Scotland, and where the development of tourism can thus also be understood as a means to further an imperialist narrative to exoticize Highland Gaelic culture.

Imperialism, the search for picturesque aesthetics and politics are therefore argued to have shaped the image of Scotland for those who read traveller’s accounts, poetry and other literary works, before Sir Walter Scott started making his influential contributions to further the image Scotland as a place to discover (Brown, Citation2012; Durie, Citation2003). Watson asserts that Scott was not the one to pioneer tourism to Loch Katrine and The Trossachs, but that he himself had chosen a setting for his writing that was already famed for picturesque and sublime scenery (Watson, Citation2010). Nonetheless, the publication of Scott’s The Lady of the Lake (1810) exerted considerable influence on how the Loch Lomond and the Trossachs area was subsequently viewed, experienced, painted and written about, and ultimately visited, further popularising tourism to Scotland and the Loch Lomond and the Trossachs area in particular (McCracken Fletcher, Citation2018).

The arrival of increasing numbers of tourists also brought along developments in associated industries. While visitors in the eighteenth century had seen themselves as explorers of unknown territories, with little touristic infrastructure, Scotland in the nineteenth and twentieth century provided a very different touristic experience with the development of railroad infrastructure, steamboat companies, offerings of horses and carriages, as well as new inns and hotels, and catered package tourism, such as those of Thomas Cook, which heralded in a new era of mass tourism at the turn of the twentieth century. However, in travel literature, much of the focus continued on the aesthetisation of landscapes and guiding the gaze of visitors away from infrastructure and other tourists ‘spoiling’ the experience towards the aesthetically pleasing aspects of the scenery (Grenier, Citation2005a).

In the following, we now briefly outline how the field of literary geography, and the spatial and digital humanities can help analysing literary constructions of landscapes in historical travel writing.

Literary geography

Travel guides consist of written experience, which offer a unique insight to how direct observations are processed and relayed in a literary form (Hose, Citation2016). The interdisciplinary field of literary geography ‘brings together geographical interest in literary texts and a more recent interest in geography and spatiality within literary studies’ (Hones, Citation2022, p. 1), and offers a theoretical basis to analyse how landscapes are constructed in literature. According to Crang (Citation2013), travel literature holds significant value within literary geography, due to the power of language and its ability to communicate emotions attached to landscapes.

For Scotland, research has highlighted the importance of literature, including guidebooks, poetry and (historical) fiction, in shaping landscape perceptions of visitors, from Burns and his poetry, to Sir Walter Scott, and Diana Gabaldon and her ‘Outlander’ books and TV adaptations (Bohls, Citation2015; Grenier, Citation2005b; McCracken Fletcher, Citation2018), even though these works may not explicitly use the framework of literary geography. For the Loch Lomond area, literary tourism was shown to be of particular importance due to the seminal works of Sir Walter Scott, amongst others, in shaping landscape perception (Brown, Citation2012). At the turn of the twentieth century the Loch Lomond and the Trossachs area, as other highly frequented areas in Scotland such as Skye, saw critiques of the this touristic development as destroying the very foundation it was built on (Grenier, Citation2005a). Complaints included that other visitors and infrastructure were spoiling the aesthetic experience, with for example Henry Cockburn (Citation1889) lamenting the sound of coach horns edible in the Trossachs all day.

In this respect, guidebooks played an important role in focusing the attention of their readers away from the busy crowds and touristic infrastructure, instead providing highly detailed characterisations of landscapes and telling readers how ‘picturesque’ or ‘romantic’ those were (Grenier, Citation2005a, p. 79). While traditional close-reading techniques in the humanities have enabled nuanced accounts of the creation of the relationship between tourism, literature and identity in Scotland (Brown, Citation2012; Deans & Leask, Citation2016; Durie, Citation2003; Grenier, Citation2005b, Citation2006; Watson, Citation2009; Wilson-Costa, Citation2009), novel digital methods enable different types of analyses and ways of engaging with historical texts.

In this regard, the digital humanities, a broad and interdisciplinary field concerned with the use computational tools and methods in the humanities (Schreibman et al., Citation2008), offers novel avenues for analysing historical travel writings that are becoming increasingly available to scholars in digitised formats (Jones et al., Citation2022). Thus, through merging Geographical Information System (GIS) frameworks with literary data, combining digital and spatial approaches in the humanities, scholars can explore the spatial dimensions of how past perceptions, experiences, and understandings of landscapes are described in travel writing (Anderson et al., Citation2017).

This has been explored, for instance, in analyses of the English Lake District (Cooper & Gregory, Citation2011; Donaldson et al., Citation2017b, Citation2017a; Gregory & Cooper, Citation2009; Gregory & Donaldson, Citation2016; Smail et al., Citation2019) demonstrating the value of incorporating quantitative spatial approaches into qualitative textual analysis of travel writing and topographical literature. For Scotland, a chapter in the edited volume Environmental Narratives (Purves et al., Citation2022) on a hybrid methodology to analyse historical travel literature for Loch Lomond provided a proof of concept using ten sources of digitised travel writing for analysis of co-occurrences (Jones et al., Citation2022). We take the previous work on literary geographies in the Lake District and expand on the sample and analysis by Jones et al. (Citation2022) by adding a larger sample of texts and additional topographic and GIS analysis, to present a literary geography study using digital and spatial humanities approaches for analysing historical travel accounts in the Loch Lomond and Trossachs area.

Materials and methods

The methodology applied in this study is based on the seminal work by researchers using digital and spatial humanities approaches to study historical textual descriptions of the English Lake District (Cooper & Gregory, Citation2011; Donaldson et al., Citation2017b) and a proof-of concept by Jones et al. (Citation2022) using ten sources to demonstrate the potential of this approach for the Loch Lomond and The Trossachs area. We follow the methodology outlined in Donaldson et al. (Citation2017b) to a large extent, but for our relatively small corpus we used a manual approach to identify landscape features, place names and aesthetic terms, instead of a computational approach, and incorporate more qualitative analysis (close reading). The novelty of this study is thus the application of an established methodology to a new geographical and political context of the Loch Lomond and the Trossachs, and to compare whether the genre follows similar patterns and tendencies of aesthetic description and linkages between terminology and physical-geographical features as in the English Lake District.

Data collection: building a corpus

To build a digitised corpus, we first selected a range of travel literature from several online archives (Internet Archive, Project Gutenberg, Hathi Trust and Google Books). Searching for key terms including ‘Loch Lomond’, ‘the Trossachs’, ‘Western Highlands’, ‘Loch Katrine’ and ‘Balloch’, we built a corpus consisting of 38 digitised works (, full references provided in Appendix 1). We accumulated historical publications which span over four centuries: from 1771 to 1934, including the Age of Sensibility (1745–1798), the Romantic Period (1798–1837), the Victorian Period (1837–1901) and the Age of Modernism (1901-1939). Although some of the publications featured in the corpus are only partially concerned with our study area – for example, Thomas Pennant’s A Tour in Scotland (1771) – we manually checked that each publication had substantial, relevant content for analysing.

Table 1. Corpus of ‘Loch Lomond and the Trossachs’ travel writing (sorted by publication year).

We chose five aesthetic terms – beautiful, magnificent, picturesque, romantic, and sublime – as they can be considered exemplary terminology, representing the new language of landscape appreciation which seemingly emerged throughout Britain in the late-eighteenth century (Donaldson et al., Citation2017b). As each term holds varied connotations and distinct meaning, this research investigates how these aesthetic terms were historically defined, understood, and applied across our corpus, and to draw conclusions if, and how this use varies compared to established literature on English aesthetic landscape descriptions from the Lake District.

Identifying place names and aesthetic descriptions

To determine the geographies associated with the five aesthetic terms, we first needed to identify the named locations (e.g. Arrochar), water bodies (e.g. Loch Lomond) and landforms (e.g. Ben Lomond; Glen Finglas) to which these terms refer to in our corpus. Using the boundaries of the contemporary Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park, we defined the spatial extent of our study area. We then compiled a list of named entities within the boundary using the National Park’s official website (https://www.lochlomond-trossachs.org/), which resulted in a list of 45 place names/settlements, 18 bodies of water, 13 mountains and 11 glens (see Appendix 2). Named locations that we later found associated with aesthetic description in the corpus, but that did not fit into one of the above classifications, were added as ‘Points of Interest’. Those included Firkin Point, Callander Bridge, Pass of Leny, Duke’s Pass, Rossdhu House and Rob Roy’s Cave.

We then identified sections that contained descriptions of named locations, water bodies and landforms using the ‘Search in Text’ feature, or each publication’s contents page, if applicable. In the absence of a contents page, we manually identified relevant sections in the corpus. The first author then manually transcribed the relevant sections of text into Microsoft Word documents and read through them to identify every instance where a named location, feature and landform occurred both individually, and in association with one of our aesthetic search terms. It must be noted that not every descriptive section concerning an entity (e.g. Loch Lomond) contained the name of the entity itself. We therefore strove to ensure that all relevant sections were included in the analysis, whether they included the relevant name or not. Although this approach is more labour-intensive, we deem it feasible for a small corpus as the one we used in this study.

Another advantage of manually identifying aesthetic descriptions also allowed us to identify incorrect spelling (often caused by optical character recognition or OCR, which is used to digitise historical literature), alternative terminology and spelling variations. As the writers of many earlier works in the corpus relied on oral sources for place names, several of these names are spelt with phonetic influence, which differ from contemporary spellings (, see examples of historic spellings in ). Due to the size of the corpus, this was a time-intensive task, but ensured high levels of accuracy and consistency. Furthermore, through manually extracting and inputting this data, we were able to disambiguate place names and personal names consistently (e.g. Sir James Colquhoun of Luss refers to a person, and not the place Luss). Our manual analysis also allowed us to exclude negated instances of aesthetic search terms (see examples in ). Additionally, close reading highlighted several occasions where travel guides described tour times, schedules, or itineraries, which referenced the named entities that are located within the study area’s boundary. As these were not descriptive, nor relevant in the search for aesthetic context, we excluded them from the textual analysis. Similarly, we excluded advertisements and descriptions outside the study area. We geolocated all identified places, water bodies and landforms by assigning them co-ordinates based on Google Maps. We noted all occurrences of an entity alongside their textual context and the year of publication. This information was transferred into spreadsheets; later allowing us to filter through search terms, and easily draw out both contextual and spatial data for the more in-depth, qualitative analysis.

Table 2. Spelling variations of named locations, water bodies and landforms found in historical travel accounts of Loch Lomond and the Trossachs.

Table 3. Examples of negated instances of the beautiful, magnificent, picturesque, romantic and sublime.

Co-occurrences of landscape elements, locations and aesthetic terms

We assessed the frequency with which named entities in the corpus co-occurred with one or more of the five chosen aesthetic terms in Microsoft Excel. First, a single named entity was selected, then every written section concerning said entity was dissected to draw out any co-occurrences between one of our aesthetic search terms and geographical feature/location, allowing for statistical testing of significant relationships. We then compared the frequency of co-occurrences with the total number of aesthetic term instances in the whole corpus, using t-scores as a statistical measurement: t-scores are used in this study as they tend to be reliable when detecting frequencies that are expected to be relatively low, which is often the case in research of this nature, as we were searching for instances of specific terminology that co-occur with a distinct set of named locations, water bodies and landforms (Donaldson et al., Citation2017b). We used a t-score of 2.0 to determine statistical significance, allowing comparison with previous research (Donaldson et al., Citation2017b). This enabled co-occurrences to be tested and deemed statistically significant if one of more of aesthetic terms was associated with a named entity more often than would be expected, given the total number of instances that a search term appeared in the corpus.

Spatially analysing aesthetic terminology

We explored the spatial patterns and relationships that occurred between aesthetic terms and named locations, water bodies and landforms using GIS. We imported all our entities, with their assigned co-ordinates, to ArcMap 10.7 (ESRI 2022). We used density smoothed mapping to visually identify clusters of co-occurrences. The higher both the t-score and frequency of an aesthetic term with a named entity, the denser the clustering appeared around the data point. However, the visual outlines created by density smoothing are affected by the underlying spatial geography of the corpus, as the number of times a named entity appears in the corpus has the potential to influence the results of statistical analysis. We therefore applied Martin Kulldorf’s spatial scan statistic (Kulldorff, Citation1997), as it had been successfully applied in literary GIS analysis (Donaldson et al., Citation2017b). This statistical spatial scan recognises where an uneven representation of search terms has been affected by the frequency of named entities. The hot spot describes any data point the spatial scan flags up as having higher co-occurrence frequencies than would be initially expected, given the spatial characteristics of the corpus, whereas a cold spot correspondingly describes a data point with fewer co-occurrence frequencies than expected. Whenever a density smoothed cluster overlaps with a hot spot, the co-occurrence between an aesthetic term and named location, water body or landform, can be considered statistically significant (Donaldson et al., Citation2017b).

Integrating topographical data: digital terrain models

Digital terrain models (DTMs) can unveil another dimension of aesthetic application in literary analysis. Through taking topographical relief into account, DTMs enable us to understand if, and/or how, physical geography has influenced the descriptive language used in landscape narratives (Donaldson et al., Citation2017b). By integrating raster-based data of Loch Lomond and the Trossachs’ terrain into GIS, elevation data can then be extracted from the DTM layer. We used the Ordnance Survey OS Terrain® 50 data (https://osdatahub.os.uk/downloads/open/Terrain50, last accessed 4.9.2023) for this study, with a 50 m resolution. We overlaid the terrain data with our co-ordinates of places, water bodies and landforms to map the geographies of these landscape aesthetic terms and determine if there were any relationships between the co-occurrences of aesthetic diction and the elevation of the landscape.

Results

In the following sections, we first introduce our findings from distant reading of the corpus, before highlighting results from our hybrid approach which combined close and distant reading techniques.

Distant reading: frequencies and co-occurrences of aesthetic terms and landscape features

All aesthetic terms analysed in this study are predominantly used to describe landscapes and surrounding scenery (). Specifically, the co-occurrence analysis indicates a prominent descriptive application of the term romantic to landscapes. Romantic shows the highest co-occurrence frequency with over 90% of cases where it co-occurs with a landscape element or place, despite having one of the lowest total instances of aesthetic terms in the corpus. This means that, although the term romantic is used less frequently in the corpus compared to the other aesthetic terms, on the occasions where it is applied, it is used to describe the landscape. The term sublime, by comparison, has the same number of total instances as romantic, yet has the lowest co-occurrence frequency of all five aesthetic terms. This implies that, although it occurs the same number of times as romantic, when sublime is applied in the text, it describes the landscape in fewer cases, namely 74.8% of the time. The term beautiful occurs more than twice the number of times as romantic or sublime but has a co-occurrence frequency of 78.1%. This suggests that, although it is the most used of the investigated aesthetic terms, it is not used as frequently in a landscape-oriented, descriptive context as romantic or picturesque.

Table 4. Total instances, co-occurrences and co-occurrence frequencies for each search term.

Hybrid approach: the geographies of landscape aesthetics

In the following sections, we present our results that combine a traditional close reading methodology with distant reading and GIS analysis of aesthetic terminology.

Beautiful

Landscapes, locations, features and landforms tend to be visually judged as beautiful if a scene, or object, is of the ‘perceived quality of being placed on a postcard’ (Kirillova et al., Citation2014, p. 284). For instance, it seems that term can be used to describe vast, indistinct phenomena, as depicted in James Denholm’s 1804 A Tour to the Principal Scottish and English Lakes where he describes his journey North to proceed ‘through a beautiful, varied scene of mountains’ (p. 25). He also, however, uses the term to describe individual entities: for example, he depicts Loch Katrine as a ‘beautiful expanse of water’ (p.50). As inferred by Donaldson et al. (Citation2017b, p. 48), beautiful tends to be ‘associated with an emotional disposition’, but it is also commonly linked to ‘objects and appearances, that induce that disposition’, indicating where the above differences may lie in contextual expression. For Edmund Burke, the term is used to describe phenomena which are capable of ‘stimulating love’ and ‘relaxing’ the mind, hence why the term may be used to describe bodies of water, which are often suggested to generate similar physiological effects in touristic experience (Burke, Citation1757).

Our close reading, combined with an analysis of co-occurrences, showed that a high number of named entities co-occurring with beautiful was likely influenced by cases of reprinting in travel guides. Several works in the corpus contain re-published phrases, passages, or even entire sections of the text from previously published accounts. In some instances, these earlier publications feature in the corpus as well. For example, the observed co-occurrence of beautiful and Loch Lomond has been influenced by the following excerpt which first appears in Black’s Picturesque Guide to the Trossachs (1853, p. 159): ‘on the east side of Loch Lomond, where that beautiful lake stretches into the dusky mountains of Glen Falloch.’ It is then reprinted in both Nelson’s Tourist Guide to the Trossachs and Loch Lomond (1858) and in Cuthbert Bede’s A Tour in Tartan Land (1863). As these duplications influence both the density smoothed results and Kulldorff’s spatial scan statistic, one might be inclined to remove instances of repetition from the literary analysis. To do so, however, risks removing a key feature of a historical corpus: its intertextuality (Greco & Shoemaker, Citation1993). This ‘feeding off’ of other publications can even be seen as an essential feature of travel literature for eighteenth and nineteenth century writers (Brewer, Citation2013).

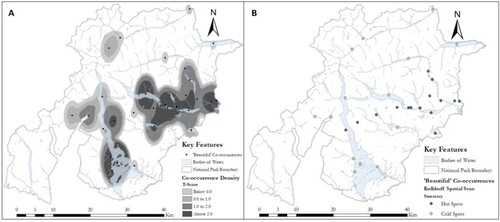

The density smoothed dot map for all 107 co-occurrences of the term beautiful (A) shows discernible clusters in several locations. To the South, there is a cluster around Loch Lomond, including Luss and Rossdhu House. Another cluster includes Ben Lomond and Loch Katrine, and a third the Trossachs region, including Loch Achray, Brig O’Turk and Glen Finglas. Finally, there is a cluster to the Eastern region around Callander and Kilmahog. The Kulldorf spatial scan (B) shows high-density clusters around Ben Lomond, Loch Achray, the Trossachs, Glen Finglas, Brig O’Turk, Callander and Kimahof, which are hot spots, as they overlap with the co-occurrences on the density smoothed map, indicating the statistical significance of these clusters. However, we identified no hot spots in the spatial scan around Loch Lomond, or around Loch Katrine and Loch Ard, indicating that these clusters are not statistically significant. Despite each of these entities being described as beautiful in the corpus, the clustering of these co-occurrences, shown in A, appear to owe much of their power to the amount of literary consideration that these entities received in the past, rather than any strong associations with aesthetic terminology.

Magnificent

Samson (1867, pp. 162–163) highlights that the term magnificent is most commonly used in reference to ‘grand’ objects which possess features worthy of ‘brilliant display’. Through close reading of our corpus, we can see that the term has been applied to collective landform formations and individual entities; both of which encompass elements of ‘grand’ prospects that Samson defines. In Our Western Hills (1892), for example, the author illustrates how ‘the mountain scene here is simply magnificent’ (p.110). This extract depicts the term being used to describe a collection of features as they appear ‘grand’ in the traveller’s eye, rather than any specific entities. In The Picture of Glasgow and Stranger’s Guide (1818, p. 298). R. Chapman claims that ‘Loch Lomond, whether regarded an account of its magnitude, or the diversity and grandeur of its scenery, is, doubtless, the most interesting and magnificent of all the British lakes.’ This depicts the connotations of the term magnificent as ‘brilliant display’ according to Samson (1867).

Although many other locations around Loch Lomond and Ben Lomond were described as magnificent (A), they were statistically less strongly associated with the term and not highlighted in the Kulldorff spatial scan. Instead, the spatial scan statistic (B) illustrates two high-density clusters of magnificent around Loch Katrine and the Trossachs.

Picturesque

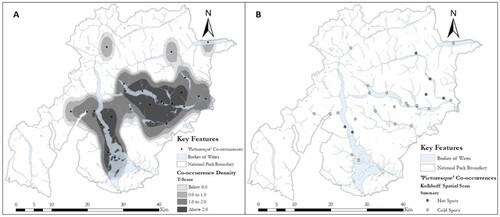

The term picturesque was coined in the eighteenth century by William Gilpin, who defined the term to be ‘expressive of that peculiar kind of beauty which is agreeable in a picture’ (Gilpin, Citation1867). This definition can apply to both individual entities and vast sceneries as a whole; examples of both are included in our corpus. As depicted by R. Chapman in The Picture of Glasgow and Strangers Guide (1818, p. 315), he refers to his journey around Loch Achray as ‘having passed the eastern extremity of this picturesque lake.’ The term is also used in Lumsden and Son’s Guide to the Romantic Scenery of Loch Lomond, Loch Katrine and the Trossachs (1844, p. 51) in a more sweeping, descriptive manner where the general scenery of Glen Finglas ‘at every step, becomes more and more picturesque.’ Although picturesque is said to traditionally emphasise ‘form and composition’ (Bohls, Citation1995, p. 15), it may also be used in a complementary manner, in junction with the other aesthetic terms we explore in this study. On many occasions where the term is used in association with another aesthetic term, the phenomena described tend to allude ‘form and composition’. In An Account of the Principle Pleasure Tours in Scotland (1819, p. 35), for example, Loch Lomond is said to compose a scene that ‘combines at once, the beautiful and picturesque.’ Again, in Our Western Hills (1892, p. 99), the author describes the cliffs of Glen Croe to be ‘at once, picturesque and sublime.’ The repetition of the phrase ‘at once’ in both of these extracts suggests that the composition of the scene, as experienced by the traveller, is key in their associations of the picturesque and the overall form of the landscape. Our spatial analysis (A) shows the density smoothed locations for the 61 co-occurrences with picturesque within the spatial boundary. Two main density clusters can be identified: one around Loch Lomond, Luss, Rowardennan and Firkin Point, and another around Stronachlachar, Loch Katrine, Ben Venue, Loch Ard, Ben Ledi and the Trossachs. In B three hot spots overlap these clusters; these are the data points representing Rowardennan, Firkin Point and Ben Ledi. The spatial scan also reveals a concentration of cold spots, which overlap with the density clusters around Loch Katrine and the Trossachs (A). This suggests that the frequency of picturesque co-occurrences is ultimately influenced by the number of times the entities in the Eastern cluster were mentioned in the corpus, rather than their associations with the aesthetic term.

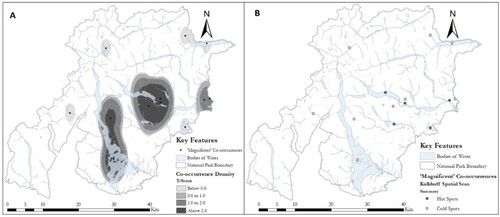

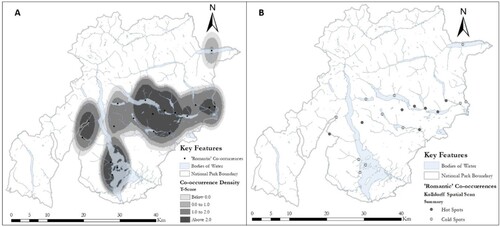

Romantic

For human geographer Tuan (Citation2013, p. 6), similarities can be found between the romantic and sublime through inclinations of ‘extremes in feeling’. Yet, Tuan claims, the term romantic ‘seeks not so much pretty or the classically beautiful’ as the sublime, indicating where the terms may differ in the context of aesthetic theory and literary application; particularly, in the context of landscape descriptions’ (p.6). Although some co-occurrences correlate with Tuan’s philosophical definition of the term, depicting elements which are not so ‘classically beautiful’, there are occasions where the terms romantic and beautiful are used in a complementary manner. For example, the geographical situation of Arrochar is described as ‘beautiful and romantic’ in A Tour to the Principal Scottish and English Lakes (1804, p. 55), whilst the Midland and North British Railways Tourist Guide to the Land of Scott (1890) uses ‘romantic beauty’ to describe the views of the Trossachs region. These extracts show that the philosophical definitions of aesthetic diction are not always translated in the contextual application within the literature. Our spatial analysis (A) indicates the presence of four density smoothed clusters for the 46 romantic co-occurrences appearing around the Southern portion of Loch Lomond, including Luss and Rossdhu House. There is a cluster of Glen Douglas and Arrochar as well as in the East, with the largest surrounding Loch Katrine, Ben Venue, the Trossachs, Glen Finglas, Aberfoyle, and Loch Venachar. Lastly, there is a cluster surrounding Kilmahog and Callander to the far East at the border of the study area. B displays the results of Kulldorff’s spatial scan statistic, which highlights an overlap in hot spots and density clusters for several locations. These are: Ben Venue, the Trossachs, Aberfoyle, Glen Finglas and Loch Venachar, suggesting these locations have statistically significant co-occurrence relationships with the term romantic.

Sublime

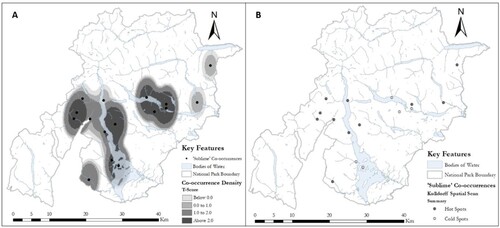

For Bohls, by the end of the eighteenth century, the term sublime was ‘primarily an affective category’ (Citation1995, p. 14). According to Krathwohl’s Taxonomy of Affective Domain, affective categories in human thought include ‘responding to phenomena’ meaning it would be expected for sublime to be commonly used in juncture with descriptions of scenic landscapes, as a whole (Krathwohl et al., Citation1964). A highlights the presence of three density smoothed clusters. One encompasses Loch Katrine, Ben Venue, the Trossachs and Ben A’an, whilst the second contains Loch Lomond, Luss, Firkin Point and Ben Lomond. For the third, there is immediately a visual difference for this term, as there is a cluster which includes Glen Croe and the Cobbler; locations which have not been included in previously discussed analysis, suggesting that sublime is of geographic and spatial variance to the four other aesthetic terms.

Figure 6. A: Density smoothed map of sublime co-occurrences B: Kulldorff’s spatial scan statistic of sublime co-occurrences.

B highlights the results from the Kulldorff spatial scan statistic, which reveals five overlapping hot spots with the density smoothed clusters; these are around Glen Croe, the Cobbler, Ben Lomond, Firkin Point and Ben A’an. It is worth noting that four of these five hot spots appear to be data points which represent relatively high elevations. This is not surprising when we consider the philosophical definitions of the term and how it was historically understood. Closer textual analysis reveals that writers tend not to label individual summits as sublime; rather, they tend to use the term to describe multiple landforms which appear massed together, often in one perspective scene. An example of this is detailed by James Denholm in A Tour to the Principal Scottish and English Lakes (1804, p. 47), where he claims that ‘the grand and towering appearance of the mountains conspired to present a prospect, highly picturesque and sublime.’ The same effect of the term being applied to indistinct entities can be seen in Lumsden and Sons Guide to the Romantic Scenery of Loch Lomond, Loch Katrine and the Trossachs (1844, p. 55), where a scene is depicted to be ‘enriched by a multiplicity of sublime objects, calculated to captivate the eye, and to afford pleasing subjects of admiration to the mind.’ These examples demonstrate the form of sublimity as illustrated by Edmund Burke in his literary defining aesthetic treatise A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1758). Burke speaks of the sublime to be associated with ‘masculinity and power’, capable of ‘exciting horror.’ The feeling of sublime is indicated to be triggered by extremes, which include ‘vastness’ and ‘extreme height’ (Burke, Citation1757), both of which are represented in the above examples. In addition to being strongly associated with sites of high elevation, especially around the Eastern region of the study area, it seems that sublime is frequently used in our corpus to describe groups of geographic features, whose undifferentiated massiveness overwhelms the eye. In both aspects, the use of sublime is distinct from that of beautiful and picturesque.

Literary geography in 3D: the relation between elevation and aesthetic terminology

In both The Genius of Scotland or Sketches of Scottish Scenery (1848) and Brydone’s Guide to the Trossachs (1856), when referencing Loch Lomond, the authors suggest that the upper, Northern parts of the lake are ‘sublime’, whilst the lower, Southern parts of the lake are the most ‘beautiful’. These descriptions are examples from our close reading where the authors deem the terms ‘beautiful’ and ‘sublime’ to have different meanings, worthy of distinct literary application. We now here present results from a quantitative, spatial analysis of these relationships (). The difference between the co-occurrence frequencies for each aesthetic term and the co-occurrence frequencies for the corpus to allow us to assess the degree to which the percentage of beautiful, magnificent, picturesque, romantic, and sublime co-occurrences in each elevation category either exceeds or falls short of the corpus average. This analysis confirms that the terms beautiful, picturesque, and romantic tend to co-occur with locations situated at lower elevations more often than magnificent and sublime. In contrast, the terms magnificent and sublime are most strongly associated with features which lie above 700 m ().

Table 5. Co-occurrence frequencies for each landscape aesthetic term by elevation.

Discussion and conclusion

Through a hybrid methodology, incorporating both GIS and literary analysis, we explored the geographies of landscape aesthetics related to what today is known as the Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park in historical travel writings. This study reveals how the beautiful, magnificent, picturesque, romantic, and sublime exhibit, with some nuances, similar geographies, in that they are applied to similar geographic locations, water bodies and landforms, despite their varying definitions in aesthetic research. This lends support to the observation by writers in the English Lake District that, despite the various definitions and precision in how to apply aesthetic terms to different sensations (Burke, Citation1757), people did not always use them in such a strict manner when speaking or writing about the landscape (Donaldson et al., Citation2017b). Nonetheless, mapping the geographies of these landscape aesthetics term does highlight some variation between the terms in the study area. When mapping hot spots, we found significant relationships between places or geographic features: for instance, Ben Lomond and the terms beautiful and sublime, or Loch Katrine and the term magnificent. These results indicate that Ben Lomond and Loch Katrine owe much of their statistically significant co-occurrences to the strong literary relationships between aesthetic terms and literary description. Furthermore, through incorporating elevation data, our analysis also revealed distinct geographies of terms related to elevation, where the terms magnificent and sublime were applied to higher elevations, whilst beautiful, picturesque, and romantic were applied to the lower-lying regions of the study area. This finding is in accordance with previous studies of aesthetic terminology and elevation in the Lake District, where Donaldson et al. (Citation2017b) found that the terms beautiful and picturesque were also often associated with lower-lying features in the Lake District, and highlighted that sublime was more commonly applied to features that are massed together. Despite the different histories and geographical settings for Scottish tourism development (Brown, Citation2012), our findings align with this previous work in the English Lake District, as we found the term sublime to cluster around landforms such as the Cobbler and Glen Croe, features not associated with the other aesthetic terms such as beautiful, romantic or picturesque. We thus find evidence that in both the Lake District and the Loch Lomond and the Trossachs, the geographies of sublime differ from other aesthetic terminologies.

Donaldson et al. (Citation2017b) found that each aesthetic term was associated with slightly distinctive geographies, which was also the case in our study, but a comparison between the elevations of these distinct geographies shows similarities across the two studies. We hypothesise that this could be a result of both corpora consisting of touristic narratives, which are normalised as a genre and use of their terminology, leading to similar descriptions and geographies of these landscape aesthetic terms, whereas local perspectives that did not find their way into written guidebooks may differ more between the two landscape settings. However, as the writers of travel literature were in a social and economic position to afford travelling, and with the rise of domestic tourism in eighteenth century Britain, many authors of travel literature were likely to visit, and record their impressions of Loch Lomond and the Trossachs after they had already visited English scenic areas such as the Lake District. By doing so, their descriptions of Scotland’s landscapes are likely to be influenced by their previous experiences with similar scenic regions. As such, the results from the Lake District study are very similar to our own conclusions of Loch Lomond and Trossachs historical writings, due to the nature of travel writing and descriptions from a (outsider) visitors’ gaze. Our findings also support the notion of scenic appreciation as part of a touristic development that sought to expand into formerly ‘hostile’ and ‘wild’ geographies of Scotland, ones which were rendered worthy of visitation through the application of aesthetic terminology that was well-known to a domestic tourist familiar with scenic appreciation and its vocabulary such as in travel literature about the English Lake District.

Methodologically, our results demonstrate the capabilities of integrating qualitative frameworks in GIS analysis. Several academic critiques exist for the use of GIS in literary geographies, however, and, as Drucker (Citation2017, p. 629) observes, ‘computers do not interpret, they simply find patterns.’ As such, because computers have no conception of human reality, they are often unable to comprehend how language is used in literary narratives, requiring manual analysis to complement computational analysis. Although GIS has furthered our understandings of the ways in which the socio-spatial history of Loch Lomond and the Trossachs has been moulded by aesthetic diction, we acknowledge the critiques that the (sole) use of GIS risks ‘flattening the complex understandings of geographical experience as they are described in literary works’ (Taylor et al., Citation2018, p. 14). A combination of GIS with close readings thus allows researchers to discover, or create, new interpretations of literature, that were not evident before (Chesnokova et al., Citation2019).

Limitations and further research

This study is limited by the use of historical sources that were already available in digital format. To develop a larger and more comprehensive corpus, including non-digitised texts, would require scanning and processing non-digitised library holdings. A larger corpus would reduce the bias in selecting only digitised historical accounts and allow further more in-depth analysis. For instance, given the limited availability of digitised material, we did not undertake a quantitative comparison between the different literary periods contained in our corpus, which would require larger corpora for each of the literary period under analysis. Future work that expands the corpus may thus analyse changes and differences between literary periods in the geographies of landscape aesthetics in travel writing.

The literary works that are available as guidebooks and printed literature are examples that privilege certain perspectives, namely those of comparatively well-educated and wealthy people able to travel and experience distant, previously unfamiliar landscapes, which they comprehend in terms of aesthetics through guidebooks (Grenier, Citation2005b). Essentially, though, they remain ‘outsider’ (Butler, Citation2016) perspectives imposed on a landscape where people live and work, and whose views are not incorporated. To provide a different window on landscapes and people-place relations, such perspectives could be taken into account, maybe through incorporating local writings in the form of newspaper articles of local news outlets. Furthermore, we suggest that further research should incorporate aesthetic terminology or other descriptive language which can be used to encapsulate landscape aesthetics, such as the terms ‘wild’ or ‘natural’, and how their geographies have changed over time.

In summary, through qualitatively and quantitively analysing the spatial application of aesthetic terms in historic travel writing of Loch Lomond and the Trossachs, this study has afforded new insights into geographies of landscape aesthetic terminology, and how the landscapes of Loch Lomond and The Trossachs were historically perceived and represented in published travel literature.

Acknowledgements

Ogg.: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Visualisation, Writing – Original Draft Preparation. Wartmann.: Conceptualisation, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Allan, G., Connolly, K., Figus, G., & Maurya, A. (2022). Economic impacts of COVID-19 on inbound and domestic tourism. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 3(2), 100075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annale.2022.100075

- Anderson, C., Ceserani, G., Donaldson, C., Gregory, I. N., Hall, M., Rosenbaum, A. T., & Taylor, J. E. (2017). Digital humanities and tourism history. Journal of Tourism History, 9(2-3), 246–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/1755182X.2017.1419455

- Bohls, E. A. (1995). Women travel Writers and the language of aesthetics, 1716-1818 (Issue 13). Cambridge University Press.

- Bohls, E. A. (2015). Picturesque travel: The aesthetics and politics of landscape. In C. Thompson (Ed.), The Routledge Companion to travel writing (pp. 246–257). Routledge.

- Brewer, J. (2013). The pleasures of the imagination: English culture in the 18th century. Routledge.

- Brown, I. (2012). Literary tourism, the trossachs, and Walter Scott. Association for Scottish Literary Studies.

- Burke, E. (1757). A philosophical enquiry into the origin of our ideas of the sublime and beautiful. Columbia University Press.

- Butler, A. (2016). Dynamics of integrating landscape values in landscape character assessment: the hidden dominance of the objective outsider. Landscape Research, 41(2), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2015.1135315

- Chesnokova, O., Taylor, J. E., Gregory, I. N., & Purves, R. S. (2019). Hearing the silence: finding the middle ground in the spatial humanities? Extracting and comparing perceived silence and tranquillity in the English lake district. International Journal of Geographical Information Science, 33(12), 2430–2454. https://doi.org/10.1080/13658816.2018.1552789

- Cockburn, L. H. C. (1889). Circuit journeys. D. Douglas.

- Cooper, D., & Gregory, I. N. (2011). Mapping the English lake district: a literary GIS. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 36(1), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2010.00405.x

- Crang, M. (2013). Cultural geography. Routledge.

- Deans, A., & Leask, N. (2016). Curious travellers: Thomas Pennant and the Welsh and Scottish tour (1760-1820). Studies in Scottish Literature, 42(2), 164–172.

- Donaldson, C., Gregory, I. N., & Taylor, J. E. (2017a). Implementing corpus analysis and GIS to examine historical accounts of the English Lake District.

- Donaldson, C., Gregory, I. N., & Taylor, J. E. (2017b). Locating the beautiful, picturesque, sublime and majestic: spatially analysing the application of aesthetic terminology in descriptions of the English Lake District. Journal of Historical Geography, 56, 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2017.01.006

- Drucker, J. (2017). Why distant reading isn’t. PMLA, 132(3), 628–635.

- Durie, A. J. (2003). Scotland for the holidays: a history of tourism in Scotland, 1780-1939. Tuckwell.

- Gilpin, W. (1867). Elements of Art criticism: Comprising a treatise on the principles of man’s nature as addressed by Art, together with a historic survey of the methods of Art execution in the departments of drawing, sculpture, architecture, painting, landscape gardening. JB Lippincott & Company.

- Greco, G. L., & Shoemaker, P. (1993). Intertextuality and large corpora: A medievalist approach. Computers and the Humanities, 27(5-6), 349–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01829385

- Gregory, I. N., & Cooper, D. (2009). Thomas Gray, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and geographical information systems: A literary GIS of two lake district tours. International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing, 3(1-2), 61–84. https://doi.org/10.3366/ijhac.2009.0009

- Gregory, I. N., & Donaldson, C. (2016). Geographical text analysis: Digital cartographies of lake district literature. In D. Cooper, C. Donaldson, & P. Murrieta-Flores (Eds.), Literary mapping in the digital age (pp. 85–105). Routledge.

- Grenier, K. H. (2005a). The development of mass tourism, 1810-1914. In K. H. Grenier (Ed.), Tourism and identity in Scotland 1770-1914: Creating caledonia (pp. 49–92). Asghate Publishing Ltd.

- Grenier, K. H. (2005b). Tourism and identity in Scotland, 1770–1914: Creating caledonia. Ashgate.

- Grenier, K. H. (2006). “Scottishness”, “britishness,” and Scottish tourism, 1770–1914. History Compass, 4(6), 1000–1023. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-0542.2006.00357.x

- Hones, S. (2022). Literary geography. Routledge.

- Hose, T. A. (2016). Three centuries (1670–1970) of appreciating physical landscapes. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 417(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP417.15

- Jones, K., Maynard, D., & Wartmann, F. M. (2022). Best practice for forensic fishing: Combining text processing with an environmental history view of historic travel writing in Loch Lomond, Scotland. In R. S. Purves, O. Koblet, & B. Adams (Eds.), Unlocking environmental narratives: Towards understanding human environment interactions through computational text analysis (pp. 127–153). Ubiquity Press. https://doi.org/10.5334/bcs.

- Kirillova, K., Fu, X., Lehto, X., & Cai, L. (2014). What makes a destination beautiful? Dimensions of tourist aesthetic judgment. Tourism Management, 42, 282–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.12.006

- Krathwohl, D. R., Bloom, B. S., & Masia, B. B. (1964). Taxonomy of educational objectives: Handbook II: Affective domain. David McKay Co.

- Kulldorff, M. (1997). A spatial scan statistic. Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods, 26(6), 1481–1496. https://doi.org/10.1080/03610929708831995

- McCracken Fletcher, L. (2018). “Scott-land” and outlander. Inventing Scotland for armchair tourists. In B. de Ruiter, C. R. Deuter, B. Goodwin-Hawkins, D. Griffin, E. K. Kelly, H.-G. Millette, L. M. Neckar, S. T. Reno, G. Roddy, & S. Whitney (Eds.), Literary tourism and the British Isles: History, imagination, and the politics of place (pp. 191–220). Lexington Books.

- Purves, R S, Koblet, O & Adams, B. (Eds.). (2022). Unlocking Environmental Narratives: Towards Understanding Human Environment Interactions through Computational Text Analysis. London: Ubiquity Press.https://doi.org/10.5334/bcs

- Schreibman, S., Siemens, R., & Unsworth, J. (2008). A companion to digital humanities. Wiley Blackwell.

- Smail, R., Gregory, I. N., & Taylor, J. E. (2019). Qualitative geographies in digital texts: Representing historical spatial identities in the lake district. International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing, 13(1-2), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.3366/ijhac.2019.0229

- Taylor, J. E., Donaldson, C. E., Gregory, I. N., & Butler, J. O. (2018). Mapping digitally, mapping deep: exploring digital literary geographies. Literary Geographies, 4(1), 10–19.

- Tuan, Y.-F. (2013). Romantic geography: in search of the sublime landscape. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Watson, N. J. (2009). Literary tourism and nineteenth-century culture. Springer.

- Watson, N. J. (2010). Readers of romantic locality: Tourists, loch Katrine and The lady of the lake. In C. Bode, & J. Labbe (Eds.), Romantic localities: Europe writes place (pp. 67–79). Pickering and Chatto.

- Wilson-Costa, K. (2009). The land of burns: Between myth and heritage. In N. J. Watson (Ed.), Literary tourism and nineteenth-century culture (pp. 37–48). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Appendices

APPENDIX 1. References for the Historical Sources that make up the corpus of Loch Lomond and the Trossachs Travel Writing:

A Glasgow Pedestrian (1892). Our Western Hills. [online] Glasgow. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/62811/62811-h/62811-h.htm [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Abbott, J. (1848). Summer in Scotland. [online] Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433069350159&view=1up&seq=11 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Anderson, M. (1819). An Account of the Principle Pleasure Tours in Scotland 1819. [online] Edinburgh: J. Thomson & Co. Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433069350167&view=1up&seq=8 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Bede, C. (1863). A Tour in Tartan-Land. [online] London. Available at: https://archive.org/details/atourintartanla00bedegoog/page/n12/mode/2up [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Bell, J.J. (1934). Scotland in Ten Days. [online] London. Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$b755745&view=1up&seq=9 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Black, A. (1861). Black’s Picturesque Tourist of Scotland. [online] Edinburgh. Available at: https://archive.org/details/blackspicturesq01firgoog/page/n10/mode/2up [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Black’s Picturesque Guide to the Trossachs. (1853). [online] Edinburgh. Available at: https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Black_s_Picturesque_Guide_to_the_Trosach/ILQHAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Boswell, J. (1785). The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides. [online] T. Cadell and W. Davies. Available at: https://gutenberg.org/cache/epub/6018/pg6018.html [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Brydone’s Guide to the Trossachs, Loch Lomond, the Highlands of Perthshire etc. (1856). [online] Available at: https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Brydone_s_Guide_to_the_Trosachs_Loch_Lom/wbJYAAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Caledonian Railway Company (1906). Tourist’s Guide. Season 1906. West Coast Route between Scotland and England. [online] Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433000643019&view=1up&seq=79&q1=loch%20lomond [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Chapman, R. (1818). The Picture of Glasgow and Stranger’s Guide. [online] Glasgow. Available at: https://archive.org/details/pictureofglasgow00unse/page/n7/mode/2up [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Croal, T. (1882). Scottish Loch Scenery. [online] Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/39892/39892-h/39892-h.htm#LOCH_LOMOND [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Denholm, J. (1804). A Tour to the Principal Scottish and English Lakes. [online] Glasgow: A. Mcgoun. Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hxjfps&view=1up&seq=9 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Fleming, J. and Swan, J. (1834). Select Views of the Lakes of Scotland from Original Paintings. [online] Glasgow. Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044024274763&view=1up&seq=1 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Johnson, J. (1834). Autumnal Relaxation in the Highlands and Lowlands. [online] London: Longman & Co. Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t0ht2hr0j&view=1up&seq=5 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Johnson, S. (1775). A Journey to the Western Isles of Scotland. [online] T. Cadell. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2064/2064-h/2064-h.htm [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Keddie, W. (1873). Edinburgh and Glasgow to Stirling, Doune, Callander, Lake of Menteith, Loch Ard, Loch Achray, the Trossachs, Loch Katrine and Loch Lomond. [online] Available at: https://archive.org/details/edinburghglasgowkedd/page/n9/mode/2up [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Leigh’s New Pocket Roadbook of Scotland. (1836). [online] Leigh and Son. Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433003276726&view=1up&seq=7 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Leighton, J.M. and Wilson, P. (1836). Swan’s View of the Lakes of Scotland. [online] Glasgow. Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112044868245&view=1up&seq=10.

Lumsden and Son (1844). Lumsden and Son’s Guide to the Romantic Guide to the Romantic Scenery of Loch Lomond, Loch Ketturin and the Trossachs. [online] Glasgow. Available at: https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Lumsden_Son_s_Guide_to_the_Romantic_Scen/4LhYAAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

MacCulloch, J. (1822). The Highlands and Western Isles of Scotland. [online] London. Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hxjuif&view=1up&seq=11 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Menzie (1852). Menzie’s Pocket Guide to the Trossachs, Loch Katrine and Loch Lomond. [online] Available at: https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Menzies_Pocket_Guide_to_the_Trosachs_Loc/grJYAAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Menzies, J. (1890). Macleod’s Tourist’s Guide through Edinburgh and Glasgow, to Loch Lomond: by four favourite routes: Balloch, Loch Long, Aberfoyle and Loch Katrine. [online] Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x001134081&view=1up&seq=11 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Miller, J. (1890). Midland and North British Railways Tourist Guide to the Land of Scott. [online] Glasgow. Available at: https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Midland_and_North_British_Railways_Touri/ChcvAAAAMAAJ?hl=en [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Mitton, G.E. (1911). The Trossachs. [online] London. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/57004/57004-h/57004-h.htm [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Murray, J. (1875). Handbook for Travellers in Scotland. [online] Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nnc2.ark:/13960/t4wh2qt86&view=1up&seq=9 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Nelson (1858). Nelson’s Tourist’s Guide to the Trossachs and Loch Lomond. [online] London. Available at: https://archive.org/details/nelsonstouristsg00thom/mode/2up [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Nodier, C. (1822). Promenade from Dieppe to the Mountains of Scotland. [online] Edinburgh: W. Blackwood. Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t4pk1137g&view=1up&seq=9 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Paterson, W. (1875). The Tourist’s Handy Guide to Scotland. [online] Edinburgh. Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.32106008919307&view=1up&seq=8 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Pennant, T. (1771). A Tour in Scotland. [online] Edinburgh: B. White. Available at: https://archive.org/details/tourinscotland1700pennuoft [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Robertson, J. (1857). Robertson’s Tourist Guide to the Beautiful and Romantic Scenery of Loch Lomond. [online] Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnzue4&view=1up&seq=9 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Shearer (1895). Shearer’s Guide to Stirling, Dunblane, Callander, the Trossachs and Loch Lomond, Killin, Loch Tay, Loch Awe, Crianlarich and Oban. [online] Stirling: R.S. Shearer & Son. Available at: https://archive.org/details/shearersguidetos00shea [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Sir J. Causton & Sons (1894). “Mountain, Moor and Loch” illustrated by pen and pencil on route of the West Highland Railway. [online] London. Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t19k4ck5t&view=1up&seq=1&q1=loch%20lomond [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Stirling & Kennedy (1831). The Scottish Tourist and Itinerary. [online] Edinburgh. Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433003277385&view=1up&seq=9 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Turnbull, R. (1848). The Genius of Scotland. [online] New York. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/38822/38822-h/38822-h.htm [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Ward, L. (1906). A Pictorial and Descriptive Guide to Oban, Fort William, the Caledonian Canal, Iona, Staffa and the Western Highlands with appendices for anglers, cyclists and motorists and golfers. [online] London. Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101076873502&view=1up&seq=7 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Wilson, G.W. (1868). Photographs of English and Scottish Scenery; Trossachs and Loch Katrine. [online] London. Available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=gri.ark:/13960/t11p0s520&view=1up&seq=19 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].

Wordsworth, D. (1974). Recollections of a Tour made in Scotland. [online] Edinburgh. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/28880/28880-h/28880-h.htm#page71 [Accessed 30 Jan. 2022].