ABSTRACT

Territorial classifications are routinely used in public policy. In Scotland, the primary classification used to delimit what, where and who is ‘rural’ is the Scottish Government’s Urban Rural Classification, introduced in 2003. However, in the recent past, there appears to have been a reframing of ‘rural definitions’ in the Scottish policy context. We highlight some of the challenges associated with developing a more nuanced framing of ‘rural’, drawing upon an analysis of responses to the statutory consultations associated with three recent items of draft legislation: namely, the 2015 consultation on provisions for a future Islands Bill, the 2019 consultation on a proposal for a Remote Rural Communities Bill, and the 2020–2021 consultation to support the preparation of the Fourth National Planning Framework. Implications of these new framings for rural policy, planning and development are discussed. Our conclusion is that, while no territorial classification system is perfect, extending the use of existing tools may offer both robust policy support as well as meaningful insights that differentiate types of ‘rural’ in a way that is a better fit for current purposes.

Introduction

There is a need for precise definitions in many domains of public policy, in large part clearly to delimit what, where and who certain policies apply to and how public funding is allocated. Territorial classifications are routinely used in public policy; one such example is the use of an urban-rural classification, versions of which are mobilised by many national governments and by supranational institutions such as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (hereafter OECD) and the European Union (hereafter EU). As Johnston (Citation1976) observed, such classifications may serve analytical, functional or political purposes: potentially, they may service more than one purpose. In Scotland, a District CouncilFootnote1 level classification of ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ was developed in the mid-1980s and, since then, exploiting developments in spatial analysis techniques, more sophisticated measures have been developed and deployed. In practice, such classifications are valuable tools for assessing the socio-economic performance (Thomson et al., Citation2014), sustainability (Copus & Crabtree, Citation1996), fragility (Highlands and Islands Enterprise, Citation2014) and disadvantage faced by rural communities (Pacione, Citation2004), and are used to direct support, resources and interventions where they are needed most. It is therefore important that they are well-considered and robustly defined. The Scottish Government’s Urban Rural Classification was introduced in 2003 and remains in use today (Scottish Government, Citation2022a). However, in the recent past, there appears to have been a reframing of what is rural, where is rural and who is rural in the Scottish policy context. This paper reviews this evolution in the context of the purpose of rural classifications and associated implications for rural policy, planning and development.

Our contribution is structured as follows. Firstly, we trace the development of definitions of ‘rural’, consider how these align with the development of spatial and typological classifications, and ask what were the purpose of these definitions. We then turn to review three contemporary examples that illustrate how, in the recent past, new framings of ‘rural’ have appeared in Scottish policy. Finally, we discuss the implications of these new framings for rural policy, planning and development, and conclude by suggesting that, while no single classification system is perfect, extending the use of existing tools may offer both robust policy support as well as meaningful insights that differentiate types of ‘rural’ in a way that is more fit for current purpose.

Defining ‘rural’

For more than a century the rural studies literature has included debates around questions such as what is rural?, where is rural? and who is rural? Overviews of key debates from a geographical perspective are offered in, for example, Hoggart (Citation1990), Halfacree (Citation1993), Cloke (Citation1994), Cloke and Thrift (Citation1994), Marsden (Citation1998), Woods (Citation2005; Citation2011), and Shucksmith (Citation2018). Debates that have shaped definitions, classifications and conceptualisations of ‘rural’ are now considered.

Understanding rurality

The nature of ‘rural’ has been debated since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, with rural regarded as a baseline against which to measure the changes emerging in cities (Hillyard, Citation2007, p. 1). Typically, rural regions were assumed to house close-knit communities displaying interdependence and tradition, while urban regions had looser, more transitory social structures (Durkheim, Citation[1893] (1997); Tönnies, Citation[1887] (1957)) and a faster pace of life (Simmel, Citation[1903] 1997). This way of thinking influenced a flurry of mid-twentieth century community studies in Britain which focused on ‘town and country’ (Frankenberg, Citation1966).

The 1960s and 1970s saw some questioning of this binary treatment of urban and rural, with community studies criticised for being ‘descriptive, static, homogenising, traditional, unscientific, abstractly empiricist and even premodern’ (Panelli, Citation2006, p. 68). Pahl (Citation1966) argued, for example, that the ‘uncritical glorifying of old-fashioned rural life’ (p. 265) and the urban–rural cleavage it champions are too simplistic. ‘Rural’ was questioned as a unit of study (Hoggart, Citation1990) and even dismissed as a ‘chaotic conception’ (Urry, Citation1984), leaving a ‘theoretical vacuum’ (Newby, Citation1977, p. 99).

The ‘cultural turn’ ushered in fresh perspectives to rural studies, foregrounding the subjective meanings that people attach to rural life (Bourdieu, Citation1977; Cloke, Citation1997; Foucault, Citation1977; Geertz, Citation1973; Jones, Citation1995; Mormont, Citation1990). This injection of a cultural dimension into rural studies led to a radical shift of focus away from physical settlements and social structures as the loci of social relations towards ‘constructed and contested notions of rurality, nature, landscape, difference, identity and otherness’ (Panelli, Citation2006, p. 81), and the rural was now positioned ‘as a series of cultural constructs, rather than a set of geographically bounded places’ (Gregory et al., Citation2009, p. 659). Far from disappearing as a significant conceptual category, ‘rural space’ as the focus of the investigation was reinvigorated, with ‘rural’ retaining what Sarah Whatmore (Citation1993, p. 605) termed an ‘unruly and intractable … significance’, both within everyday life and for our academics. Rural was hence re-established as a unit of analysis, albeit a complex and nuanced one, and new framings of rural have fused cultural elements with material and social dimensions (Halfacree, Citation2006; Liepins, Citation2000a). Most recently, academics have offered critical reflections on how terminology used to describe non-urban places in one nation does not necessarily travel well into another national context. In international policy and scholarship, this linguistic divide can create confusion and misunderstandings about where, who and what is ‘rural’ (Ghartzios et al., Citation2020; Pelucha & Kasabov, Citation2021).

Classifications

Classification can be seen as an important stage of developing the ‘modern’ academic social science disciplines (De Geer, Citation1923; Semple & Green, Citation1984), including disciplines concerned with the rural, such as geography and sociology. Classifications have variously imposed hierarchical understandings of the rural (Semple & Green, Citation1984), offered understandings of the similarities and differences between places, and pointed to ‘essential’ characteristics of particular kinds of places (Clarke, Citation1980) and ‘types’ of rural.

Cloke’s (Citation1977) ‘index of rurality’ for England and Wales is a classic example of the application of quantitative approaches to define and classify ‘rural spaces’. Geodemographic variables continue to be used to produce knowledges utilised in a variety of commercial, political, and planning contexts, while spatial analysis techniques have allowed for the inclusion of increasingly diverse indicators that represent characteristics of places and their surrounding environments (Blunden et al., Citation1998; Singleton & Spielman, Citation2014). Internationally, both hierarchical and typological classifications are important tools used in rural planning and development. Despite the objectivity that the use of numerical techniques may infer, classification is best understood as a subjective process (Johnston, Citation1968). Data-based approaches for defining ‘geographies’ are still shaped by decisions made by those who collect and collate the data, by the stated purpose of the classification, and by how criteria used in the classification are determined. Semple and Green (Citation1984, p. 56) argue that ‘classifications should be designed for a specific purpose; they rarely serve two purposes equally well. Purpose and use must be linked’. The importance of understanding determinants of the purpose of any geographical classification was highlighted by Johnston (Citation1976), who suggested that purpose, whether that be analytical, functional, political, or otherwise, should be made explicit. That said, in practice, classifications and the types within them are often appropriated by third parties and used for reasons sometimes far removed from the original purpose. They can create artificial boundaries which become contested and politicised as new knowledge about the nature of the places they delineate emerges (Duffy & Stojanovic, Citation2018).

Within a policy and planning context, attempts to identify socio-economic problems ‘on the ground’, to organise and disburse resources and to generate actions and interventions can be inherently spatial activities, underpinned by the application of spatial classifications which, inevitably, reflect imperfect conceptualisations of the rural (Cloke, Citation2006). But how are specific places delimited for such purposes? We now provide an account of the evolution of rural classifications in the Scottish context, classifications which are socially constructed representations of space (Halfacree, Citation2006) and primarily deployed as a functional tool for planning and policy, before considering recent re-framings of rural and their implications for policy.

Rural definitions within the Scottish context: 1980s and 1990s

What is now referred to as the Randall definition was conceived to support statistical reporting of economic trends in a manner that would allow needs in rural Scotland to be identified (Randall, Citation1985) and adopted in a number of policy areas overseen by the Scottish Office. It defined ‘rural’ Scotland as those District Council areas with a population density of less than one person per hectare, using 1981 census data. This population sparsity measure, illustrative of a combined administrative and morphological approach to constructing rurality (Férat et al., Citation2020), was not without limitations. These included the use of blunt population thresholds, a well-documented weakness of largely descriptive definitions of ‘rural’ (see Woods, Citation2005), and the use of local government Districts as the geographical unit of analysis which concealed variations within these areas (c.f. Shucksmith et al., Citation1996). Despite these limitations, however, this definition served an analytical purpose, underpinning the analysis of socio-economic data which could differentiate between attributes of ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ Scotland. As noted by Pacione (Citation2004, p. 378), ‘while there is no standard definition of rural Scotland … that proposed by Randall (Citation1985) … attained widespread acceptance’.

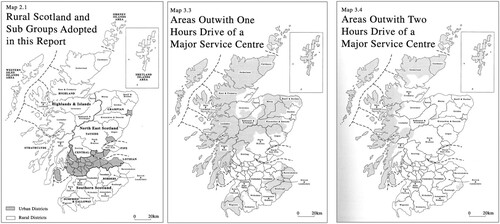

To support the preparation of the 1995 White Paper Rural Scotland: People Prosperity and Partnership (Scottish Office, Citation1995), the Rural Affairs Division of the Scottish Office Environment Department commissioned research reported in the 1992 publication Scottish Rural Life: A socio-economic profile of rural Scotland. Here it was noted that more remote areas, defined as those outwith a one-hour drive of a major service centre, ‘often display symptoms of under-development and economic and social disadvantage’ (Scottish Office, Citation1992, p. 13). A refinement to the Randall definition was hence presented which introduced two accessibility indicators – physical remoteness parameters – to the classification of rurality across Scotland: (i) areas outwith a one-hour drive and (ii) areas outwith a two-hour drive of a major service centre. This change marked the beginning of moves within Government-sponsored research formally to classify different types of ‘rural’ areas across Scotland using population and accessibility metrics. An update to the Scottish Rural Life report was published in 1996 (Shucksmith et al., Citation1996). It included the maps reproduced in , while the Executive Summary proposed that areas outwith a one-hour drive of a major service centre be considered ‘remote’ and those outwith a two-hour drive ‘very remote’.

Figure 1. Maps showing which urban and rural districts and areas of Scotland outwith one and two hours drive of a major service centre. Reproduced from Scottish Rural Life Update 1996.

Using 1991 Census data, the General Register Office Scotland (GRO-S) introduced a postcode unit based, sub-District Council level classification of urban and rural areas. This allowed settlements of various sizes (the smallest being those with populations of between 500 and 999) and the population living in communities with fewer than 500 persons to be identified. This development provided a much more nuanced spatial classification of area types than had previously been achieved, facilitating analysis of socio-economic data that could illustrate the heterogeneity of rural across Scotland. It did not, however, directly engage with more conceptual quandaries such as at what point does a settlement become large enough to be classed ‘urban’?

The Scottish Rural Life and Scottish Rural Life Update reports both pointed to a need to classify rurality in a manner that recognised: (a) population density in itself was an insufficient measure; (b) Distinct Council areas were too large a spatial unit to distinguish meaningfully between urban and rural areas of Scotland; and (c) distance from major service centres is an important dimension of rurality and, as such, should be considered in classifications of rural to allow different types of rural area to be distinguished. It is within this context that the Scottish Urban Rural Classification, discussed below, was developed.

The Scottish Urban Rural Classification

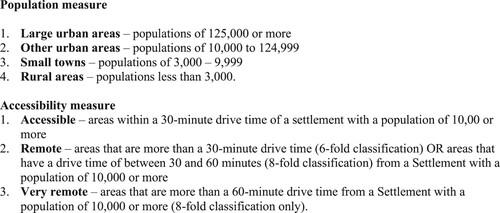

Developed in 2000, and with classifications available from 2003, the Scottish Urban Rural Classification is based on two main criteria, (i) population and (ii) accessibility, and has been updated biennially. The population measure is derived from the Settlements dataset produced by the National Records of Scotland, which aligns with the GRO-S settlement classification described above. The accessibility measure is based on drive times to an urban area ‘calculating 30- and 60-minute drive times from the population-weighted centroids of Settlements with a population of 10,000 or more’ (Scottish Government, Citation2022a, p. 4). Details of the population and accessibility measures are presented in . The Scottish Urban Rural Classification ‘provides a consistent way of defining urban and rural areas across Scotland. The classification aids policy development and the understanding of issues facing urban, rural and remote communities’ (UK Government, Citation2022, ‘Summary’ para.1).

Figure 2. Attributes of the population and accessibility measures used in the Scottish Urban Rural Classification. Source: Scottish Government (Citation2022b), p4.

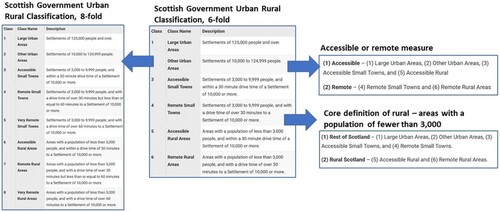

The Scottish Urban Rural Classification was influenced by – and needed to align with – territorial classifications deployed by the EU, ones reflecting OECD typologies (see Férat et al., Citation2020, for an overview of the evolution of OECD typologies and how these influenced EU classifications). In combining population and accessibility measures, the Scottish classification conforms with the approach developed by the OECD in the 1990s to produce a three-fold rural classification distinguishing between types of rural areas on the basis of their proximity to ‘functional urban areas’, and it is broadly compatible with the version of the EU’s NUTS 3 urban-rural typology, introduced in 2003, that incorporates an accessibility measure. The Scottish Urban Rural Classification is hierarchical, containing 2-, 3-, 6- and 8-fold territorial classifications (see and maps available at https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-government-urban-rural-classification-2020/pages/2/.). Compatibility with the NUTS 3 classification served broadly political imperatives, ensuring that Scotland’s territorial classification met requirements associated with spatial policies such as the Structural Funds through which significant sums of money supported rural development activities in areas of Scotland – such as those that were eligible for ‘Objective 1’ (such as the Highlands and Islands) and ‘Objective 5b’ (such as Dumfries and Galloway) – funding in the 1990s and 2000s.

Figure 3. Hierarchies within the Scottish Government Urban Rural classification. Source: adapted from content available at https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-government-urban-rural-classification-2020/pages/2/.

The Scottish Urban Rural Classification has proven useful to policy-makers and to others who make use of spatial statistics, but it does have limitations. For example, small towns are routinely excluded from official ‘rural’ statistics: in the biennial Rural Scotland Key Facts reports, small towns, home to around 11% of the national population, are bundled up with ‘rest of Scotland’ in the 3-fold classification. Across Scotland, small towns are important service and employment centres serving both their own residents and the populations residing in their hinterlands. An argument can be made that they are an intrinsic element of rural Scotland and that, by amalgamating them with cities and other urban areas, a distorted picture of rural Scotland is presented. Another limitation is that the attributes of Scotland’s inhabited islands, and by inference the challenges they face, are not adequately captured in the classification. Likewise, attributes of the most remote mainland communities can be overlooked if statistical reporting fails to use the 8-fold variant’s ‘very remote’ definition. Nonetheless, despite these limitations, the Scottish Urban Rural Classification offers a clearly defined, consistent approach to the classification of different types of rural areas across the country.

New framings of ‘rural’ in Scottish policy

There have been attempts to unpack ‘the rural’ in Scottish policy over the past decade or so. This unpacking has, to varying degrees, allowed for different manifestations of rural across Scotland’s non-urban territory to be recognised. Reference to coastal places emerged in National Planning Framework 2 (Scottish Government, Citation2009). This document also made reference to ‘rural and remote communities’, with the Western Isles cited as an illustration of this term. These changes reflect refinements to what remain functional approaches to classifying geographical space. More recently, islands have received prominence, with references to ‘rural’ being replaced by ‘rural and island’ in policy discourse, a response to increasing political visibility of islands and island issues and, in consequence, an illustration of (largely political party neutral) political imperatives influencing spatial classification. How did this shift come about? What are the possible implications? Does this change muddy definitions of rural such as those expressed in the Urban Rural Classification?

Responses to the statutory consultations associated with three recent items of draft legislation highlight some of the challenges associated with developing a more nuanced framing of rural in a Scottish policy context. The responses we consider belowFootnote2 are those submitted to: (i) the 2015 consultation on Provisions for a Future Islands Bill (which led to the Islands (Scotland) Act in 2018); (ii) the 2019 proposal for a Remote Rural Communities Bill; and (iii) preparations for the Fourth National Planning Framework (NPF4). Our methodological approach is outlined in the following section.

Insights from three public consultations: our approach

A public consultation Provisions for a Future Islands Bill took place between September and December 2015. It received 192 responses from a range of individuals, groups and organisations (see ), of which 181 were attributed and 11 anonymous responses, all published online. Our analysis of the published responses focused on responses to question 1: ‘Is the concept of “Island-Proofing” something the Scottish Government should consider placing in legislation through the proposed Islands Bill?’, to which 128 respondents provided a comment. In the first stage of the analysis, all published responses to this question were read to give a sense of the range of perspectives expressed. In the second stage anonymous responses were excluded, leaving 96 responses from a range of individuals, organisations and geographies which were read more closely and then coded and synthesised, identifying broad themes (after Charmaz, Citation2006).

Table 1. Responses to the Consultation on Provisions for A Future Islands Bill, Safeguarding Scotland’s Remote Rural Communities Consultation and National Planning Framework Four Consultation by respondent type.

A public consultation Safeguarding Scotland’s remote rural communities (Ross, Citation2019) was opened in October 2019 as part of the formal process of developing a Remote Rural Act, proposed by (now former) Memberof the Scottish Parliament (MSP) Gail Ross in response to calls from within the Scottish Parliament for mainland remote rural areas of Scotland to be afforded similar provisions to those given to island communities in the Islands (Scotland) Act. This consultation received 173 responses from individuals and a variety of stakeholders (see ). Of these, 155 were published online, all of which were read to give a sense of the range of perspectives expressed. Secondly, excluding responses from individual private citizens and anonymised responses, 50 responses were reviewed with a focus directed to the 28 which explicitly referred to attributes, characteristics or definitions of rurality, broadly defined.

National Planning Framework 4 (NPF4) is the ‘national spatial strategy for Scotland. It sets out our spatial principles, regional priorities, national development and national planning policy’ (Scottish Government, Citation2023, ‘Publication – Strategy/plan’ para. 1). A public consultation on the content of the draft version of NPF4 (Scottish Government, Citation2022b) ran between November 2021 and March 2022. It attracted over 750 responses, of which 695 from individuals and a variety of stakeholders (see ) were published online. Excluding responses from individuals, a fifth were submissions from organisations aligned with a broadly defined ‘rural sector’ and considered likely to be interested in draft Policy 31: Rural Places and the accompanying consultation question ‘Do you agree that this policy will ensure that rural places can be vibrant and sustainable?’. From the ‘rural sector’ responses, a sample of a third (n = 33) was selected to illustrate the most common respondent types and, where appropriate, to illustrate responses from different locations across rural Scotland. Their responses to the consultation question linked to draft Policy 31 were read in full, following which the text of 16 submissions in which specific reference was made to the terminology used to describe rural places was coded and synthesised, identifying broad themes.

We turn now to present and discuss the themes identified in our analysis of consultation responses.Footnote3 Care has been taken to represent a range of rural and island groups and stakeholder organisations across the three consultations as we move to discuss our findings below.

The Provisions for a Future Islands Bill consultation

Historically, in terms of policy, Scotland’s islands have not been distinguished from other areas of Scotland. For some time, the three island authorities (N-ha Eilean Siar, Orkney Islands and Shetland Islands councils respectively) have argued that islands face unique challenges that warrant separate consideration in the development and rollout of policy. The origins of the case for considering islands as a distinct type of rural place in policy can be traced back to the 1973 Local Government (Scotland) Act. This legislation created three ‘all-purpose’ unitary authorities for Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles respectively , authorities which remained unaltered in subsequent local government reorganisation in the 1990s.

The unique placement of the islands in the new framework was reviewed by a Committee of Inquiry into the Functions and Powers of the Islands Councils of Scotland (Montgomery Committee) which was asked to recommend any legislative changes that would be in the interests of the islands or the nation. The Committee deemed the creation of the island councils as all-purpose authorities a ‘great success’ and recommended that ‘the opportunity should be taken whenever possible to consolidate, develop and extend these powers’ (Macartney, Citation1985, p. 310). Considering islands in the context of national policy, the Montgomery Committee made two recommendations that laid the groundwork for future consultations and legislation:

In future consultations between the Scottish Office and local authorities, Scottish Office departments should, as a matter of course, give consideration as to whether there might be grounds for asking for a separate islands councils view to be included in any collected response from local authorities. … There may be circumstances in which Acts of Parliament should include a provision to allow the Secretary of State to vary their application to the island areas, and such provisions should in future be considered in relation to all Scottish legislation at an early stage in its preparation. (Macartney, Citation1985, pp. 310–311)

The Scottish Government responded with the Lerwick Declaration, which led to the establishment of an Island Areas Ministerial Working Group which developed the Empowering Scotland’s Island Communities prospectus, published in June 2014 (Scottish Government, Citation2014). The prospectus committed the Scottish Government to producing a Bill for an Islands Act to ensure that island communities are represented in government, and that all of Scotland’s inhabited offshore islands (currently 93) – not just those within the jurisdiction of the three island-only authorities – are properly considered in policies and service provision decision making.

Analysis of responses submitted to the Provisions for a Future Islands Bill identified overwhelming agreement that the Scottish Government should consider placing the concept of ‘island-proofing’ in legislation, whereby relevant authorities must consider: (a) whether policies, strategies or services could impact islands differently from other communities; and (b) how policies, strategies or services can be developed in such a way that they improve or mitigate negative outcomes for island communities (Scottish Government, Citation2016). Respondents whose submissions supported the island-proofing concept felt that islands have particular, multiple challenges (including, for example, transport, weather, cost of living and population sparsity) distinct from mainland communities and particularly mainland urban communities. These challenges are many and wide-ranging. Many respondents felt that, because of these challenges, a ‘one size fits all’ approach to policy and legislation across the whole of Scotland is inappropriate, and that national solutions often fail to take account of island issues. There is thus a need for tailored legislation, policy and service design:

The ‘one size doesn’t fit all’ argument is compelling. Island proofing would ensure that policies set at national level would be subject to greater due diligence than at present, thereby effectively taking the islands’ situation into account. If implemented effectively, it would have the merit of systematically reminding policymakers about the island dimension of their decisions. (Orkney Islands Council, Response 255077879)

However, other respondents highlighted the danger that island-proofing may not account for the diversity of island challenges and experiences. For example, an individual respondent (Response 832437564) noted that some islands lie within the jurisdiction of exclusively island authorities, while others such as those in Argyll and Bute lie within local authorities that also span mainland areas. The latter requires the needs of very different communities to be balanced, and a perception was expressed in some quarters that it is easier, and more economic, for these authorities to focus their efforts on more populated parts of the mainland. In addition, Tiree Community Council, and representatives from other small islands, felt that it is difficult for the voice of smaller islands to be heard amidst the louder voices of the bigger islands, whose concerns can be quite different. To counter these challenges the creation of a single Islands Authority, and direct representation for every island within the existing local government structure, was proposed:

[We] would wish to see smaller populated islands, such as Tiree, being either directly represented, or becoming part of a larger existing, or newly formed Islands Authority. Only by this measure will we achieve constitutional representation, and additionally a real say in what happens to our island. (Tiree Community Council Response 498340105)

Despite majority agreement that island-proofing is desirable in principle, several respondents to the consultation, island stakeholders and others, expressed some concern that it could lead to the needs of mainland rural communities, remote rural areas in particular, being overlooked. For example:

It is important to recognise that many of the challenges faced by island communities, demographic change, transport links, access to services and employment opportunities and higher costs of living are also faced by remote mainland communities. Any additional measures considered by Government should aim to achieve better outcomes for all communities facing similar challenges. (Highlands and Islands Enterprise, Response 720250070)

It is clear that a distinction should not be made between island and mainland communities where this could lead to disparities in the opportunities, support and powers afforded to island communities and not to others. (Society of Local Authority Lawyers and Administrators in Scotland (SOLAR), Response 385295202)

The Islands (Scotland) Act has raised the profile of the inhabited islands, formally recognising this type of place as distinctive and foregrounding awareness of island challenges and opportunities in a policy context. But what about other types of rural area and their needs? In recognising the Scottish inhabited islands as being distinct from mainland rural Scotland, is there indeed a risk – as noted above – that the challenges and opportunities of remote (mainland) rural Scotland, in particular, will be overlooked? It is within this context that we turn to consider the proposal for a Remote Rural Communities Bill.

Proposal for a Remote Rural Communities Bill

In 2019, Gail Ross MSP proposed a Members’ Bill in response to calls from within Parliament for mainland remote rural areas of Scotland to be afforded similar provisions to those given to island communities in the Islands (Scotland) Act. Documentation supporting the Safeguarding Scotland’s remote rural communities consultation stated: ‘In considering this Bill [The Islands Bill] it became clear that many of the issues being considered in the context of our island communities were equally relevant to our mainland communities’ (Ross, Citation2019, p. 2). The consultation for a Remote Rural Bill was thus explicitly framed as being complementary to the Islands (Scotland) Act. It focused on three key aspects of safeguarding remote rural communities in Scottish policy making, through: (1) remote rural proofing; (2) empowering remote rural communities; and (3) proposing the development of a National Remote Rural Plan, to match provisions of the Islands Bill to develop a National Islands Plan. The consultation defined remote rural areas using the 6-fold version of the Scottish Urban Rural Classification. While it was recognised that this classificatory system provided a working definition, possible limitations were acknowledged, inferring that if a Bill were to proceed the definition of ‘remote rural’ and further specificity regarding what is ‘remote rural’ could both be reviewed, as suggested below:

This is the Scottish Government’s definition of remote and rural areas, although there is an opportunity for us to redefine what the boundaries of these communities should be. With this proposed legislation, as with any legislation or policy that puts a line on a map, some communities may be geographically more accessible, but still feel remote from centres of population. On the other hand, we may pinpoint a community as ‘remote’ but the people that live there may not recognise that classification. There are other classifications that take into account socio economic factors which, instead of travel time to the next settlement of 10,000 people, take into account travel time into one of Scotland’s seven cities. (Ross, Citation2019, p. 15)

The importance of using a clear and consistent definition of remote rural in the Bill was noted by the Law Society of Scotland, who stated:

During the passage of the Islands (Scotland) Act 2018, we noted that the Bill covered a disparate set of issues and that many of the issues identified in the policy memorandum – ‘geographic remoteness, declining populations, transport and digital connections’ – were also relevant to rural communities more generally. It is important that there is clarity, certainty and consistency in the law. It is therefore crucial that there is a clear definition of remote rural communities in the context of this proposed Bill. (Law Society of Scotland, Response No. 171 – NO ID)

Other consultation responses did not, however, support legislating for a specific type of ‘rural’, indicating a preference for a homogenous approach to ‘rural’ policy that was associated with concerns about applying the existing Urban Rural Classification to distinguish between different types of rural Scotland. For example, responses from Paths for All and the National Rural Mental Health Forum, both organisations with an interest in the wellbeing of rural communities, highlighted the need to consider vulnerable people regardless of where they live. The National Rural Mental Health Forum (Response No. 122, ID:133575050) made reference to the fact that drive times used in the Urban Rural Classification to differentiate between accessible and remote rural areas overlook mobility realities for those without access to a car.

Dumfries and Galloway LEADERFootnote5 Local Action Group (LAG) went further. Their support for the Bill was conditional on the remote rural definition being revisited because they felt that the Urban Rural Classification was too blunt a measure to accommodate attributes of South-West Scotland, noting: ‘DG LAG successfully included our 2 urban areas in our Local Development Strategy because they are small and significantly affect areas of urban and remote rural designation in the LEADER programme’ (Dumfries and Galloway LEADER Local Action Group, Response No. 151, ID 134732261).

Despite broad support (from 97% of consultation respondents) for ‘rural-proofing’ in a Scottish policy context, a move which would afford mainland rural communities protections that island-proofing offers, the proposal for a Remote Rural Bill did not progress beyond the consultation phase. While the Urban Rural Classification’s distinction between ‘accessible’ and ‘remote’ rural Scotland did not receive universal support, the importance of using a consistent definition of ‘rural’ continued to be evident in many consultation responses. We now turn to consider (a lack of) consistent definitions, based on the process of developing Scotland’s Fourth National Planning Framework.

The Fourth National Planning Framework Consultation

National Planning Framework Four (NPF4) brings together a ‘long-term spatial strategy with a comprehensive set of national planning policies to form part of the statutory development plan’ (Scottish Government, Citation2023, ministerial forward). Spatial planning and spatial strategies are not detailed directives for local development; instead, they establish a direction of travel for multi-sectoral policies designed and delivered by different tiers of government. As observed by Woods (Citation2019, p. 623), ‘Spatial planning is critical to the reconfiguration of rural-urban relations, and to questions of rural economic development, infrastructure and service delivery, and the provisioning of new resource demands, including for ecosystem services’. As such, NPF4 will influence national and local planning decisions across Scotland that affect urban, rural and island communities. Across Europe it is common for ‘planning authorities [to] use typologies in their identification of areas in strategic planning and implementation of spatial policy’ (Férat et al., Citation2020, p. 6). The NPF4 draft (Scottish Government, Citation2021), however, did not use or reference the Scottish Urban Rural Classification or classifications deployed by, for example, the OECD. Analysis of responses submitted by groups associated with the rural sector voiced concerns that priorities set out in NPF4 draft Policy 31: Rural Places would introduce ill- or undefined rural definitions into national planning policy which could lead to inconsistent application of rural development policy and decision-making at the local level.

Scottish Rural Action’s submission (Response 191663936) flagged that the classifications of ‘accessible, intermediate and remote areas across the mainland and islands’ were not defined, adding ‘they are not aligned with the Scottish Government’s Urban Rural Classification System’. They expressed the opinion that, contrary to what was set out in the draft policy, the requirement for planners to identify these three classes of area in local development plans should be removed. Rural Housing Scotland (Response 288992245) also noted that the three categories referred to by Scottish Rural Action were not defined, did not align with the Scottish Urban Rural Classification and should be defined in the NPF4 documentation The South of Scotland Enterprise (SOSE) submission welcomed draft Policy 31: Rural Places but with the caveat that the policy would benefit from refinement to align development plan policies with definitions for the spatial terminology used:

… in particular, definition and clarification of the key words and phrases that underpin the policy – ‘Rural Places’, ‘Accessible, intermediate and remote areas’, ‘Remote Rural Areas’ – is required. The term ‘rural’ is not a one size fits all definition, and rurality can mean significantly different things depending on location. (South of Scotland Enterprise (SOSE), Response 701447331)

Strongly worded criticism of the use of other terminology without accompanying definitions was made in Scottish Rural Action’s submission which stated:

Other parts of Policy 31 introduce further rural and island area concepts, such as ‘areas under pressure or in decline’, ‘fragile’ areas, and ‘previously inhabited areas’. These areas will all be difficult to define, implement, and monitor. The invention of new, un-defined rural area policy concepts is both unhelpful and likely to conflict with the policy goals. (Scottish Rural Action, Response 191663936)

Concerns expressed by the rural sector and others, such as those illustrated above, were acknowledged in Government’s published analysis of consultation responses which informed the preparation of the final version of NPF4 that was laid before the Scottish Parliament in November 2022 (Scottish Government, Citation2022b). This analysis noted that around 275 respondents answered the question linked to draft Policy 31: Rural Places, many of whom raised concerns about the content of NPF4 as it would apply to rural areas, including impressions that the policy was weak, overlooked the potential for rural communities to contribute to national strategic objectives and that NPF4 as a whole had not been effectively ‘rural-proofed’. The lack of precision or reference to definitions for terminology used in draft Policy 31: Rural Places identified in our analysis was also noted, indicating that what was meant by ‘rural areas’, ‘rural places’, ‘accessible’, ‘intermediate’, ‘remote’, ‘areas of pressure and decline’ ‘accessible’, ‘intermediate’, ‘remote’ and ‘areas of pressure and decline’ should all be clarified and ‘which form of the Scottish Government’s Urban/Rural Classification is to be applied’ (ibid. p. 292) should be made clear. In the context of draft Policy 31 (g) Development proposals in remote rural areas, where new development can often help to sustain fragile communities, a request for a definition of ‘remote rural areas’ was also identified.

Did this consultation influence the final version of NPF4? It did, in part. The word ‘intermediate’ does not appear anywhere in NPF4. ‘Accessible’ is used, but never linked to ‘rural’. The meaning of ‘remote rural’ is specified on two occasions, in the preambles to Policy 17: Rural Homes (p. 65) and Policy 29: Rural Development (p. 86) which both state: ‘the Scottish Government’s 6-fold Urban Rural Classification 2020 should be used to identify remote rural areas in Local Development Plans’ (Scottish Government Citation2023b, p. 65 and p. 68). A definition for ‘rural areas’ is not offered but islands are treated as a distinct spatial type in the text, reflecting the special status afforded to islands following the passing of the Islands (Scotland) Act 2018. The revised Glossary of definitions does not include terminology related to rural classifications or provide the reader with any details of the categories used in the Scottish Urban Rural Classification. Spatial terminology associated with (mainland) rural places remains ambiguous and potentially open to multiple interpretations by those who will use NPF4.

Discussion

The Scottish Urban Rural Classification has been used for two decades as a tool to facilitate geographically differentiated reporting of national statistics and allocating resources and support. It offers a consistent means of distinguishing between different types of place, and the 6- and 8-fold versions allow, albeit to a limited degree, the heterogenous nature of ‘rural’ to be expressed. Regular updates mean that changes in population and accessibility have been reflected in successive versions of the Classification, while further changes in the status of places across Scotland are likely once 2022 Census data becomes available and road improvement schemes such as the dualling of the A9 are completed.

As described above, new framings of rural in a policy context have emerged recently as some communities and territorially based stakeholders have called for greater consideration of the attributes, opportunities and challenges of specific types of ‘rural’, arguing in particular that the challenges presented by their geography are not being sufficiently recognised and addressed in policy. This may be read as a political (largely political party neutral) endeavour, a call for rural places and rural communities to become more visible in national debates and their needs better reflected in policy-related decision-making. The clearest example of this aspect is the reframing of ‘islands’ in policy circles. Legislation (the Islands (Scotland) Act) and the renaming of the biennial Scottish Rural Parliament, an event now known as the Scottish Rural and Islands Parliament, illustrate the foregrounding of islands as places different but related to ‘rural’. As illustrated in our analysis, the recognition of islands as a separate geographical category has been generally welcomed.

Proposed as a stream of work undertaken as part of the Scottish Government Strategic Research programme 2022–2027, the so-called NISRIEFootnote6 analytical framework extends the 8-fold Urban Rural Classification to a 10-fold classification that distinguishes between mainland and island very remote rural and between mainland and island very remote small towns (Thomson et al., Citation2023, p. 14). The NISRIE framework could easily be adopted in the next update of the Urban Rural Classification, enhancing its functional purpose and, in separating islands from mainland rural, responding in part to the political imperative to raise the profile of Scotland’s islands. The arguments underpinning the NISRIE framework could also be used to encourage Government to report, as a matter of routine, socio-economic data about Scotland’s small towns, be they in accessible, remote or island contexts, something that has, to date, been lacking (the 2- and 3-fold iterations of the Urban Rural Classification bundle small towns alongside much larger urban communities in the ‘urban’ category: see ).

Responses to the Islands Bill considered above included calls to recognise that Scotland’s islands are heterogenous. Illustrating an approach that recognises this diversity, the 9-fold island subregions created by Wilson et al. (Citation2021) in their analysis of responses to the first National Islands Plan Survey distinguished between: (i) mainland islands of Orkney and Shetland and islands connected to mainland islands by fixed link; and (ii) the ferry connected islands in these archipelagos. National Records of Scotland has recently adopted the subregions as an official geography, the ‘Scottish Island Regions’, and this provides a framework for collecting, analysing and reporting data designed to ‘help our understanding of the issues faced by the population of Scotland’s islands’ (Scottish Government Rural and Environmental Science and Analytical Services, Citation2023, p. 8). It could be used alongside the NISRIE classification and the Gow Typology (Gow et al., Citation2023) to assist those charged with preparing Island Communities Impact Assessments (a form of ‘island-proofing’), a statutory requirement designed to ensure that new policies are sensitive to the differences between islands and mainland communities.

The differentiation of islands from mainland rural Scotland has, however, opened up a ‘can of worms’ with respect to the treatment of mainland rural places and communities in policy. As was noted in the rationale for proposing a Remote Rural Communities Bill. islands arguably share many of their challenges or – to use the terminology of the Lisbon Treaty – ‘handicaps’ with remote rural communities on the mainland. Even the Scottish Islands Federation (a ‘voice for the Scottish islands’) expressed this view in the consultation on a future Islands Bill, and other respondents voiced concern that the Islands Bill could introduce disparities in opportunities between islands and other rural contexts by promoting the needs of islands over mainland communities. That said, responses to the second consultation that we have considered in this contribution reported mixed opinions about the desirability of legislating for remote mainland rural communities. As noted above, there were calls for a consistent approach to distinguishing between different ‘types’ of rural (c.f. the response from the Law Society of Scotland). The nuance offered by statistical reporting which distinguishes between accessible, remote and very remote rural areas is lost by the routine amalgamation of these groups into a single ‘rural’ category for statistical reporting. Reporting which does not differentiate between Scotland’s small towns and much larger urban centres also overlooks the fact that, as functional entities, most small towns have strong relationships with their rural hinterlands and, arguably, are more part of the landscape of rural Scotland than of urban Scotland. Such differentiation could be achieved if more widespread use was made of all the categories contained in the existing 8-fold Urban Rural Classification or the NISRIE variant. Analytical opportunities are presented by using these spatial classifications which would allow further understanding of the heterogeneity of contemporary rural Scotland to emerge.

An alternative means by which different types of rural could be distinguished would see more use being made of Copus and Hopkins' (Citation2017) Sparsely Populated Areas (SPA) classification to facilitate better policy-making and to promote targeted rural development plans. Unlike the EU’s approach to defining sparsely populated areas, based on population density, the Scottish SPA tool is based on population potential, an approach which classifies areas ‘in terms of the number of persons who reside within a certain distance … [and] takes account of both low density within the immediate areas and access to adjacent populations’ (ibid., p. 4). In considering access to adjacent populations, Hopkins and Copus (Citation2018, p. 22) argued that their SPA classification ‘better represents the real economic and social implications of sparsity’ and helps to elucidate attributes of and challenges facing those areas of Scotland – island and mainland – with the smallest populations. Using the Scottish SPA and the NISRIE 10-fold classification could assist the application of ‘rural mainstreaming’, a requirement of the National Performance Framework designed to ensure the needs of rural Scotland are taken into account within all domains of Government, foregrounding the variety of attributes associated with places and communities across contemporary rural Scotland and thus supporting the articulation of more nuanced decision-making in, for example, the currently under development Rural Delivery Plan (Scottish Government, Citation2023a).

Our analysis of consultation responses to draft NPF4 illustrates a case where use is made of spatial terminology without this terminology being defined or clearly aligning with existing spatial classifications. Can the Scottish Government’s requirement that the needs of rural Scotland are ‘mainstreamed’ in all policies, as set out in the National Performance Framework, be achieved if the spatial development strategy does not provide a clear definition of what comprises rural Scotland and its subdivisions? Whilst we recognise a need for planning and development professionals to be able to respond to the local context, the lack of clearly defined and consistently applied rural definitions in NPF4 could hinder equitable translation of national strategic planning ambitions into local development activities. With islands now having a distinct place within Scottish legislation, our concern is primarily that the differentiated needs of mainland rural communities could be overlooked. Official guidance directing planners to consider the diverse attributes and needs of rural communities could suggest routine use is made of the 6- and 8-fold urban rural classification and/or other typologies such as the SPA classification or those produced by the OECD, ESPON or Eurostat (see Férat et al., Citation2020 for an overview). This approach could enable the same care and consideration afforded to the islands to be given to mainland rural areas, the more physically remote and sparsely populated in particular.

Conclusion

This paper has considered recent reframing of what is rural, where is rural and, by inference, who is rural in a Scottish policy context and reflected on some associated implications of this reframing for rural policy, planning and development. No territorial/spatial classification system/ typology is perfect. Such measures cannot account for experiential and cultural accounts of contemporary rural places and communities, the importance of which many academic contributions have highlighted. The variables they include are limited to those for which robust data for small spatial units is available and the cut-off points they use within variables such as total population, beyond which a small town becomes ‘other urban’, are blunt. They are, however, something of a necessity if society and by extension politicians and policy-makers accept that ‘rural’ has different attributes to ‘urban’, and that opportunities and challenges can be shaped by geography. To this end, we conclude this paper by stating that we are convinced of the utility of continuing to use a functional Urban Rural Classification to support policy-making and evaluation in Scotland but contend that the existing Urban Rural Classification should be modified: adopting the NISRIE extension to the 8-fold Urban Rural classification would be a useful starting point. This would accommodate the more political imperative to raise the profile and recognise the needs of, Scotland’s island communities. Insights offered in Copus and Hopkins’s (Citation2017) SPA classification could also be incorporated, along with the use of the Island Regions geographical classification. These moves would go some way to ensuring that remote rural mainland needs become more to the fore in decision-making, a counterweight to mainland rural needs being potentially marginalised if more prominence is given to islands. Such a revised and then consistently applied Scotland-wide Urban Rural Classification will be a useful tool to support rural policy and planning in the second quarter of the twenty-first century.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their thanks to fellow participants at the ESRS 2022 satellite event ‘Transitioning Rural Futures’ for their supportive conversations and feedback on an early version of this work. Insightful comments from two anonymous reviewers, the special section editor Mags Currie and SGJ Editor-in-Chief Chris Philo have been exceedingly helpful in guiding revisions to the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 District Councils were the lower level of the two-tier local government structure in place across Scotland between 1975 and 2006. The Local Government etc. (Scotland) Act 1994 legislated for the replacement of the District and Region structure with a single tier local authority structure in 1996.

2 Responses to the three consultations from individuals and organisations that gave permission for their submission to be published are available to downloaded from: (1) https://consult.gov.scot/islands-team/islands-bill-consultation/consultation/published_select_respondent; (2) https://gailrossremoteruralcommunities.wordpress.com/proposed-remote-rural-communities-scotland-bill-gail-ross-msp/; and (3) https://consult.gov.scot/local-government-and-communities/draft-national-planning-framework-4/consultation/published_select_respondent.

3 Quotations extracted from individual consultation responses presented in this paper are attributed to respondents in a manner that allows the responses to be identified in the publicly available documentation supporting each consultation. Please note that the attribution style varies because the three sets of consultation materials do not use the same attribution nomenclature.

4 The Treaty of Lisbon is an agreement amending previous treaties forming the constitutional basis of the European Union (EU), signed by EU member states in December 2007 and entering into force in December 2009.

5 LEADER is a local development method, centring on local action groups (the LAGs), that has been deployed across the EU for over 30 years, acting as a vehicle for distributing and deploying funds intended to support rural areas. The term ‘LEADER’ originally came from the French acronym for Liaison Entre Actions de Développement de l'Économie Rurale, meaning 'Links between the rural economy and development actions'.

6 NISRIE - which stands for Novel Insights on Scottish Rural and Island Economies - is a project funded as part of the eScottish Government’s 2022–2027 Strategic Research Programme on Environment, Natural Resources and Agricultur: for details, see https://www.nisrie.scot.

References

- Blunden, J. R., Pryce, W. T. R., & Dreyer, P. (1998). The classification of rural areas in the European context: An exploration of a typology using neural network applications. Regional Studies, 32(2), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409850123035

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge University Press.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

- Clarke, J. I. (1980). Population geography. Progress in Human Geography, 4(3), 385–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/030913258000400305

- Cloke, P. (1977). An index of rurality for England and Wales. Regional Studies, 11(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595237700185041

- Cloke, P. (1994). Rural. In R. Johnston, D. Gregory, & D. Smith (Eds.), The dictionary of human geography (3rd edition, pp. 536–537). Blackwell Reference.

- Cloke, P. (1997). Country backwater to virtual village? Rural studies and ‘the cultural turn’. Journal of Rural Studies, 13(4), 367–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-0167(97)00053-3

- Cloke, P. (2006). Conceptualizing rurality. In P. Cloke, T. Marsden, & P. Mooney (Eds.), The handbook of rural studies (pp. 18–28). Sage.

- Cloke, P., & Thrift, N. (1994). Introduction: Refiguring the ‘rural’. In P. Cloke, M. Doel, D. Matless, M. Phillips, & N. Thrift (Eds.), Writing the rural five cultural geographies (pp. 1–6). Chapman.

- Copus, A., & Crabtree, J. (1996). Indicators of socio-economic sustainability: An application to remote rural Scotland. Journal of Rural Studies, 12(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/0743-0167(95)00050-X

- Copus, A., & Hopkins, J. (2017). Outline conceptual framework and definition of the Scottish sparsely populated area (SPA) RESAS RD 3.4.1 demographic change in remote areas woking paper 1. James Hutton Institute. November 2017. https://www.hutton.ac.uk/sites/default/files/files/RD%203_4_1%20Working%20Paper%201%20O1_1%20161117.pdf.

- De Geer, S. (1923). On the definition, method and classification of geography. Geografiska Annaler, 5(1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/20014422.1923.11881066

- Duffy, P., & Stojanovic, T. (2018). The potential for assemblage thinking in population geography: Assembling population, space, and place. Population, Space and Place, 24(3), e2097. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2097

- Durkheim, E. ([1893] (1997)). In W. D. Halls (Trans.), The division of labor in society. Free Press.

- European Union. (2007). Consolidated version of the treaty on the functioning of the European Union – Part Three: Union policies and internal actions – Title XVIII: Economic, social and territorial cohesion – Article 174 (ex Article 158 TEC).

- Férat, S., Berchoux, T., Requier, M., Abdelhakim, T., with Slätmo, E., Chartier, O., Nieto, E., & Miller, D. (2020). D3.2 Framework Providing definitions, review and operational typology of rural areas in Europe. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5337099.

- Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Random House.

- Frankenberg, R. (1966). Communities in Britain: Social life in town and country. Penguin.

- Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. Perseus.

- Ghartzios, M., Toish, N., & Woods, M. (2020). The language of rural: Reflection towards and inclusive rural social science. Journal of Rural Studies, 78, 325–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.06.040

- Gow, K., Currie, M., Duffy, P., Wilson, R., & Philip, L. J. (2023). Gow’s typology of Scotland’s islands: Technical notes. University of Aberdeen.

- Gregory, D., Little, J., & Watts, M. (2009). Rural geography. In D. Gregory, R. Johnston, G. Pratt, M. Watts, & S. Whatmore (Eds.), The dictionary of human geography (5th Edition, pp. 659–660). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Halfacree, K. (2006). Rural space: Constructing a threefold architecture. In P. Cloke, T. Marsden, & P. H. Mooney (Eds.), Handbook of rural studies (pp. 44–62). Sage.

- Halfacree, K. H. (1993). Locality and social representations: Space, discourse and alternative definitions of rural. Journal of Rural Studies, 9(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/0743-0167(93)90003-3

- Highlands and Islands Enterprise (HIE). (2014). Review of fragile areas and employment action areas in the Highlands and Islands: Executive summary. https://www.hie.co.uk/media/3105/reviewplusofplusfragileplusareasplusandplusemploymentplusactionplusareasplusinplustheplushighlandsplusandplusislandsplus-plusexecutiveplussummaryplus-a2363434.pdf.

- Hillyard, S. (2007). The sociology of rural life. Berg.

- Hoggart, K. (1990). Lets do away with rural. Journal of Rural Studies, 6(3), 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/0743-0167(90)90079-N

- Hopkins, J., & Copus, A. (2018). Definitions, measurement approaches and typologies of rural areas and small towns: A review. James Hutton Institute. www.sruc.ac.uk/downloads/file/3810/342_definitions_measurement_approaches_and_typologies_of_rural_areas_and_small_towns_a_review.

- Johnston, R. J. (1968). Choice in classification: The subjectivity of objective methods. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 58(3), 575–589. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1968.tb01653.x

- Johnston, R. J. (1976). Classification in geography. Geo Abstracts Ltd.

- Jones, O. (1995). Lay discourses of the rural: Developments and implications for rural studies. Journal of Rural Studies, 11(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/0743-0167(94)00057-G

- Liepins, R. (2000a). New energies for an old idea: Reworking approaches to ‘community’ in contemporary rural studies. Journal of Rural Studies, 16(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-0167(99)00042-X

- Macartney, A. (1985). Island Councils & the Montgomery Inquiry. In D. McCrone (Ed.), The Scottish Government Yearbook 1985 (pp. 310–316). Unit for the Study of Government in Scotland, University of Edinburgh.

- Marsden, T. (1998). New rural territories: Regulating the differentiated rural spaces. Journal of Rural Studies, 14(1), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-0167(97)00041-7

- Mormont, M. (1990). Who is rural? Of How to be rural: Towards a sociology of the rural. In T. Marsden, P. Lowe, & S. Whatmore (Eds.), Rural restructuring: Global processes and their responses (pp. 21–44). David Fulton Publishers.

- Newby, H. (1977). The deferential worker: A study of farm workers in East Anglia. Allen Lane.

- Our Islands, Our Future. (2014). Constitutional change in Scotland – Opportunities for islands areas. Joint Position Statement. Available at https://www.cne-siar.gov.uk/media/7964/jointpositionstatement.pdf.

- Pacione, M. (2004). The geography of disadvantage in rural Scotland. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 95(4), 375–391.

- Pahl, R. E. (1966). The rural-urban continuum. Sociologia Ruralis, 6(3), 299–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.1966.tb00537.x

- Panelli, R. (2006). Rural society. In P. J. Cloke, T. Marsden, & P. Mooney (Eds.), The handbook of Rural Studies (pp. 63–91). Sage.

- Pelucha, M., & Kasabov, E. (2021). Defining rural areas: A never-ending exercise? In M. Pelucha, & E. Kasabo (Eds.), Rural development in the digital Age. Exploring neo-productivist EU rural policy (pp. 15–35). Routledge.

- Randall, J. N. (1985). Economic trends and support to economy activity in rural Scotland. Scottish Economic Bulletin, HMSO, No31 1985.

- Reid-Howie Associates Ltd. (2016). Consultation on provisions for a future islands bill. Analysis of responses. https://www.gov.scot/publications/consultation-provisions-future-islands-bill-analysis-responses/documents /.

- Ross, G. (2019). Safeguarding Scotland’s remote rural communities. A proposal for a Bill to enhance the consideration given to remote rural mainland communities by public bodies in Scotland Consultation by Gail Ross MSP, Member of the Scottish Parliament for Caithness, Sutherland and Ross October. https://archive2021.parliament.scot/S5MembersBills/GR_Consultation_Final.pdf.

- Scottish Government. (2009). National planning framework 2. https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-planning-framework-scotland-2/.

- Scottish Government. (2014). Empowering Scotland's island communities prospectus, June 2014. https://www.gov.scot/publications/empowering-scotlands-island-communities/.

- Scottish Government. (2016). Consultation on provisions for a future islands bill. https://consult.gov.scot/islands-team/islands-bill-consultation/.

- Scottish Government. (2019). National plan for Scotland’s islands. https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-plan-scotlands-islands/.

- Scottish Government. (2021). Scotland 2045 – Our fourth national planning framework draft. https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotland-2045-fourth-national-planning-framework-draft/documents/.

- Scottish Government. (2022a). Our fourth national planning framework. Analysis of responses to the consultation exercise. Analysis Report. Scottish Government, Edinburgh. https://www.gov.scot/publications/draft-fourth-national-planning-framework-analysis-responses-consultation-exercise-analysis-report/documents/.

- Scottish Government. (2022b). Scottish government urban rural classification 2020. Geographic information science and analysis team and rural and environment science and analytical services division. May 2022. https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-government-urban-rural-classification-2020/documents/.

- Scottish Government. (2023a). Equality, opportunity, community. New leadership – A fresh start. Scottish Government, Edinburgh. https://www.gov.scot/publications/equality-opportunity-community-new-leadership-fresh-start/documents/.

- Scottish Government. (2023b). National planning framework 4. https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-planning-framework-4/.

- Scottish Government Rural and Environmental Science and Analytical Services. (2023). Scottish island regions (2023): Overview. https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-island-regions-2023-overview/documents/.

- Scottish Office. (1992). Scottish rural life: A socio-economic profile of rural Scotland. HMSO.

- Scottish Office. (1995). Rural Scotland people prosperity and partnership. HMSO.

- Scottish Parliament. (2018). Meeting of the Parliament, 30 May 2018: Official Report, p. 74. https://www.parliament.scot/api/sitecore/CustomMedia/OfficialReport?meetingId=11570.

- Semple, R. K., & Green, M. B. (1984). Classification in human geography. In G. L. Gaile, & C. J. Willmott (Eds.), Spatial statistics and models (pp. 55–79). D. Reidel Publishing Company.

- Shucksmith, M. (2018). Re-imagining the rural: From rural idyll to good countryside. Journal of Rural Studies, 59, 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.07.019

- Shucksmith, M., Gemmell, A., Edmond, H., & Williams, N. (1996). Scottish rural life update. A revised socio-economic prolife of rural Scotland. The Scottish Office.

- Simmel, G. ([1903] 1997). The metropolis and mental life. In D. Frisby & M. Featherstone (Eds.), Simmel on culture (pp. 174–185). Sage.

- Singleton, A. D., & Spielman, S. E. (2014). The past, present and future of geodemographic research in the United States and United Kingdom. The Professional Geographer, 66(4), 558–567.

- Thomson, K., Vellinga, N., Slee, B., & Ibiyemi, A. (2014). Mapping socio-economic performance in rural Scotland. Scottish Geographical Journal, 130(1), 1–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2013.848764

- Thomson, S., Atterton, J., Tiwasing, P., McMillan, J., Pate, L., Vuin, A., & Merrell, I. (2023). Rural and Islands Report: 2023 – An Insights Report. A SRUC output from the NISRIE project funded by the Scottish Government. https://doi.org/10.58073/SRUC.23807703.

- Tönnies, F. ([1887] (1957)). In C. P. Loomis (Ed. And Trans.), Community and society. David & Charles.

- UK Government (June. (2022)). Urban rural classification – Scotland. https://www.data.gov.uk/dataset/f00387c5-7858-4d75-977b-bfdb35300e7f/urban-rural-classification-scotland.

- Urry, J. (1984). Capitalist restructuring, recomposition and the regions. In T. Bradley & P. Lowe (Eds.), Locality and rurality (pp. 45–65). GeoBooks.

- Whatmore, S. (1993). On doing rural research (or breaking the boundaries). Environment and Planning A, 25(4), 605–607.

- Wilson, R., Hopkins, J., Currie, M., Potts, J., Somervail, P., & Stevenson, T. (2021). The National Islands Plan Survey: Final Report. ://www.gov.scot/publications/national-islands-plan-survey-final-report/documents/.

- Woods, M. (2005). Rural geography. Sage.

- Woods, M. (2011). Rural. Oxon.

- Woods, M. (2019). The future of rural places. In M. Scott, N. Gallent, & M. Gkartzios (Eds.), The Routledge companion to rural planning (pp. 622–663). Routledge.