1. Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronically relapsing inflammatory disease of the colonic mucosa. It affects genetically susceptible hosts that are influenced by environmental factors and contributions by the individual´s microbiome. Hallmark feature of UC is a dysbalanced immune response at the mucosal surface of the large intestine. Bloody diarrhea is the characteristic symptom of the disease, which is often accompanied by abdominal pain. Despite these signs of active inflammation that severely impact the quality of life of UC patients, there are long-term complications that have to be taken into account as well. These include functional loss of bowel function by fibrosis and elevated risk for colorectal cancer.

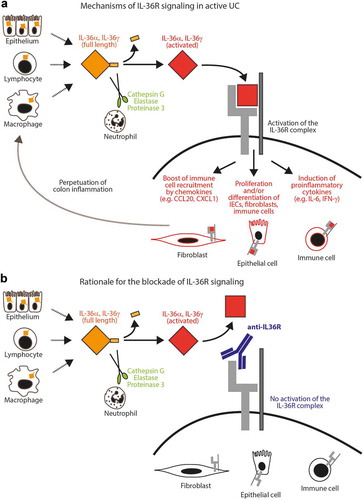

Figure 1. Model for the role of IL-36R signaling in UC.

(A) Full-length IL-36α and IL-36γ are released by different gut residing cells and are then enzymatically processed by extracellular neutrophil proteases into highly active IL-36R agonists. Ligand binding to the IL-36 receptor complex results in active signaling and thereby stimulation of various arms of pro-inflammatory effector mechanisms in fibroblasts, intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) and immune cells. Attraction of additional immune cells further promotes the perpetuation of intestinal inflammation. (B) Upon blockade of the IL-36R by a neutralizing anti-IL-36R antibody, signaling through the IL-36R is inhibited preventing pro-inflammatory loop amplification in the colon.

Recent advances in understanding the immunopathogenesis of UC have led to the development of targeted biological therapies, which have become a mainstay in the induction and maintenance treatment of UC. This considerable therapeutic progress has been achieved in particular by the implementation of inhibitory agents that specifically block pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling (e.g. anti-TNF antibodies, antibodies directed against the common p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23 and small molecules that inhibit the JAK/STAT signaling pathway), or immune cell trafficking (e.g. antibodies directed against the α4β7 integrin). Nevertheless, rational treatment of UC patients still remains a major clinical challenge, as available therapies are only efficacious in a subgroup of patients and long-term use is often associated with secondary non-response. Furthermore, most of the aforementioned substances harbor the risk of sometimes severe side-effects. There is, therefore, the unmet clinical need for novel treatments with an improved efficacy and safety profile [Citation1]. Recent insights into pathophysiological mechanisms at the intestinal mucosa suggest a critical role of IL-36R signaling in colonic inflammation, tissue remodeling and fibrosis [Citation2–Citation4].

2. Rationale for targeting the IL-36R signaling pathway in ulcerative colitis

Cytokines are considered key players during the perpetuation vs. resolution of intestinal inflammation in IBD and a balanced regulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory effector mechanisms is critical for the immune homeostasis at mucosal surfaces in the healthy individual [Citation5,Citation6]

Interleukin 36 (IL-36) is a group of closely related molecules that belong to the IL-1 family of pro-inflammatory cytokines. IL-36α (IL-1F6), IL-36β (IL-1F8), and IL-36γ (IL-1F9) are activators of the IL-36 receptor (IL-36R), whereas IL-36Ra (IL-1F5), and IL-38 (IL-1F10) are two naturally occurring inhibitors blocking IL-36 receptor (IL-36R) signaling. The clinical importance of a tightly regulated balance of IL-36R signaling was initially highlighted by an autosomal recessive disease in individuals carrying loss-of-function mutations in the IL36RN [Citation7]. This genetic alteration is the molecular basis for the deficiency of IL-36 receptor antagonist (DITRA) syndrome, representing a group of patients suffering from generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP). GPP/DITRA syndrome is the prototypical IL36-mediated disease, which is characterized by recurrent flares of pustular, erythematous rashes of the skin, often resulting in life-threatening consequences [Citation7].

Several studies have recently addressed the expression of IL-36 family members in IBD, demonstrating upregulation of IL-36R agonists during ongoing intestinal inflammation. In particular, both IL-36α and IL-36γ were found at increased mucosal expression levels in active UC in different patient cohorts all over the world, highlighting modulation of IL-36R as a common feature in UC [Citation2,Citation4,Citation8–Citation10]. Strikingly, IL-36R ligands can be expressed by various gut cells including lymphocytes, macrophages and the intestinal epithelium [Citation8,Citation10]. Whereas it is believed that both IL-36α and IL-36γ can be released upon cellular disintegration during necrotic cell death, mechanisms that can guide the secretion of the IL-36 family members have not been clearly elucidated. Nevertheless, full activation of IL-36R ligands requires processing by proteolytic cleavage and truncated proteins exhibit an up to 1000fold increase in specific activity/potency [Citation11]. Although IL-36α and IL-36γ lack typical protease cleavage sites, recent work could identify a number of extracellular neutrophil proteases, including Cathepsin G, Elastase and Proteinase 3 that are able to process and thereby efficiently regulate the activity of these cytokines [Citation12]. Thus, activated neutrophils release multiple proteases into the extracellular space, which can then enzymatically truncate and activate IL-36R ligands if locally present. In line with current concepts, some of the enzymes mediating IL-36α and IL-36γ processing have been reported at elevated expression levels in IBD [Citation13]. Interestingly, localization of IL-36γ has been observed not only in the cytosol but also in the nucleus suggesting additional potential roles in gene transcription.

IL-36R activation induces activation of NF-kappaB and MAPKs in a MYD88 dependent manner resulting in the induction of different pro-inflammatory effector mechanisms by the target cells. These consist of immune and nonimmune cells residing in or trafficking to the colon, including intestinal epithelial cells, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts.

Whereas the pathophysiological role of dysregulated IL-36R signaling is well accepted in skin diseases such as the GPP/DITRA syndrome, the functional consequences of persistent IL-36R activation in gut disorders such as IBD have recently gained growing attention. A couple of in vivo studies addressed the role of IL-36 in the intestine during the past years, highlighting a critical role of IL-36R activation during colon inflammation. In fact, the inhibition of IL-36R signaling diminished experimental colitis in different models suggesting a rather ‘global’ mechanism of action [Citation2–Citation4]. Nevertheless, the pathophysiological role of IL-36R signaling in the colon appears to be influenced by the specific molecular context as demonstrated by studies showing that the blockade of IL-36R is connected to compromised intestinal wound healing [Citation9,Citation10].

Mechanistically it has been shown, that IL-36R activation can enhance the proliferation of gut cell populations including immune and nonimmune cells, and this effect can be mediated directly and/or by indirect means, e.g. through the modulation of IL-2 promoting the proliferation of lymphocytes. Moreover, the activation and functional modulation of intestinal fibroblasts with concurrent boost of cytokines (IL-6, IL-1, GM-CSF), chemokines (CCL2, CXCL1, CXCL2) and additional pro-inflammatory effector molecules guide further recruitment and activation of innate and adaptive immune cells to the colon. Altogether, these IL-36R associated mechanisms are believed to amplify pathophysiological loops that perpetuate colonic inflammation and interfere with mechanisms guiding the resolution of inflammation (). Moreover, persistent IL-36R signaling in colon fibroblasts drives fibrosis-associated molecular mechanisms, e.g. by induction of types 6 and 1 collagen. In addition, the differentiation of T cells is influenced by the activation of the IL-36R driving pro-inflammatory Th1 and Th9 responses [Citation3,Citation14]. Correspondingly, it was proposed that the IL-36R axis can control the balance between anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells and pro-inflammatory Th9 cells [Citation3].

In addition to its role in immune modulation by guiding inflammatory programs in lymphocytes and fibroblasts, IL-36R activation was also shown to modulate the production of anti-microbial proteins such as LCN2 in intestinal epithelial cells [Citation10], suggesting additional regulation of the microflora which is known to guide the course of gut inflammation. Correspondingly, it was recently demonstrated that IL-36 cytokines are able to alter colonic mucus secretion and outgrowth of A. muciniphila [Citation15]. In conclusion, various lines of evidence suggest that the modulation of the IL-36R pathway represents a promising therapeutic approach in the treatment of colonic inflammation, e.g. in UC.

3. Clinical trials with an anti-IL36R antibody in ulcerative colitis

The afore-described immunopathological implications have led to the development of therapeutic interventions that specifically aim to block IL-36R dependent signaling (). The humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody spesolimab (BI655130) that is directed against the IL-36R, recently demonstrated therapeutic efficacy in a phase 1 proof-of-concept study involving patients who presented with a GPP flare, thus providing the first evidence for clinical efficacy of IL-36 blockade in human inflammatory conditions [Citation16]. Spesolimab is currently also tested in Crohn’s disease and palmoplantar pustulosis patients and has entered phase II trials in active UC patients. Blockade of the IL36R by the antagonistic antibody aims to prevent subsequent activation of pro-inflammatory and tissue remodeling pathways in UC. In an ongoing phase II induction study (NCT03482635; estimated completion date: 05/2022), clinical activity of spesolimab is analyzed in moderate to severely active UC patients who have failed previous biological therapy. Long-term efficacy and safety of IL-36R blockade with spesolimab is furthermore studied in a subsequent open-label phase II trial with UC patients that completed previous trials (NCT03648541; estimated completion date: 03/2031). Moreover, possible synergistic effects of IL-36R activation with TNF signaling suggest a therapeutic potential for double targeting of IL-36R along with already established anti-TNF treatment options. Therefore, a proof-of-concept phase II study (NCT03123120; estimated completion date: 09/2020) with spesolimab as add-on treatment in mild-to-moderately active UC patients during ongoing anti-TNF inhibitor therapy is currently conducted as well.

4. Expert opinion

The inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling, and the blockade of immune cell trafficking have emerged as two potent strategies of currently approved UC therapies. Blockade of the IL-36R pathway, which is dysregulated in active inflammation at outer and inner surfaces of the body including UC, can act mechanistically on both levels. Thus, inhibition of IL-36R dependent signaling emerges as a very attractive target for the treatment of UC, as it has been implicated to be centrally involved in UC disease pathogenesis at different levels. Correspondingly, blockade of the IL-36R by neutralizing antibodies is currently tested in ongoing clinical trials inactive UC patients.

Apart from anti-inflammatory mucosal effects that might be elicited by IL-36R inhibition, therapeutic rationale for this approach is further strengthened by possible effects on intestinal myofibroblasts in UC patients. It has been observed that IL-36-induced genes are upregulated in human (myo)fibroblasts [Citation4,Citation17], which not only release pro-inflammatory cytokines but also tissue remodeling related mediators (e.g. tissue growth factor, TGF-ß and matrix metalloproteinases). Inhibition of IL-36R could therefore not only lead to anti-inflammatory effects but might also elicit anti-fibrotic signals. Specific anti-fibrotic therapy approaches would target a currently unmet clinical need, as fibrosis has been shown to progress independently from inflammatory activity and suppression of inflammation alone conversely failed to prevent or treat fibrosis. Fibrosis is an important issue not only in structuring Crohn’s disease but also in UC, which similar progressive disease nature is best reflected by submucosal fibrosis and muscularis mucosae thickening, which are both associated with severity of disease. These tissues remodeling features lead to heightened stiffness of the mucosal wall, which becomes clinically evident by heightened rectal urgency and incontinence in affected UC patients [Citation18].

Clinical trial activities, where inhibition of the IL-36R is combined with existing anti-TNF antibody therapy, reflect ongoing therapeutic approaches where combination of biologic therapies is tested to improve therapeutic outcomes. Therapeutic efficacy of this specific approach would also offer valuable mechanistic insights into IL-36R dependent molecular mechanisms that might drive resistance to anti-TNF therapy. Nevertheless, further trials to assess the efficacy and long-term safety of biologic combination treatment are needed to clarify potential synergistic therapeutic effects.

In the developing era of personalized medicine, testing the dysregulation of specific pathways in the treatment of biological naïve or refractory UC patients might identify individuals, which could particularly benefit from therapies blocking the IL-36R pathway. Of note, different IL-36 family members are existing which can be released by various gut resident cell types. In addition, stepwise processing of the ligands is required, and IL-36 signaling occurs through a heterodimeric receptor complex which is expressed on different immune and nonimmune cells. These characteristics offer multiple possibilities for drug developments and targeting the IL-36 signaling in the colon, e.g. by the blockade of the receptor or its co-receptor, neutralization of individual IL-36 family members or the inhibition of activating enzymes. Recently, efficient targeting of IL-36 cytokine activation was demonstrated by small-molecule elastase inhibitors [Citation19]. Nevertheless, future studies will need to show whether these promising strategies are successful and if so, which way of inhibition will facilitate the most powerful treatment option for the individual patient.

Declaration of interest

C Neufert, MF Neurath and R Atreya served as advisors to Boehringer-Ingelheim. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose

Additional information

Funding

References

- Atreya R, Neurath MF. Mechanisms of molecular resistance and predictors of response to biological therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(11):790–802.

- Russell SE, Horan RM, Stefanska AM, et al. IL-36alpha expression is elevated in ulcerative colitis and promotes colonic inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:1193–1204.

- Harusato A, Abo H, Ngo VL, et al. IL-36gamma signalling controls the induced regulatory T cell-Th9 cell balance via NFkappaB activation and STAT transcription factors. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10:1455–1467.

- Scheibe K, Kersten C, Schmied A, et al. Inhibiting Interleukin 36 receptor signaling reduces fibrosis in mice with chronic intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(4):1082–1097.

- Neurath MF. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(5):329–342.

- Neurath MF. Targeting immune cell circuits and trafficking in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Immunol. 2019;20(8):970–979.

- Marrakchi S, Guigue P, Renshaw BR, et al. Interleukin-36-receptor antagonist deficiency and generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:620–628.

- Nishida A, Hidaka K, Kanda T, et al. Increased expression of Interleukin-36, a member of the Interleukin-1 cytokine family, in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(2):303–314.

- Medina-Contreras O, Harusato A, Nishio H, et al. Cutting edge: IL-36 receptor promotes resolution of intestinal damage. J Immunol. 2016;196(1):34–38.

- Scheibe K, Backert I, Wirtz S, et al. IL-36R signalling activates intestinal epithelial cells and fibroblasts and promotes mucosal healing in vivo. Gut. 2017;66(5):823–838.

- Towne JE, Renshaw BR, Douangpanya J, et al. Interleukin-36 (IL-36) ligands require processing for full agonist (IL-36α, IL-36β, and IL-36γ) or antagonist (IL-36Ra) activity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(49):42594–42602.

- Clancy DM, Sullivan GP, Moran HBT, et al. Extracellular neutrophil proteases are efficient regulators of IL-1, IL-33, and IL-36 cytokine activity but poor effectors of microbial killing. Cell Rep. 2018;22(11):2937–2950.

- Vergnolle N. Protease inhibition as new therapeutic strategy for GI diseases. Gut. 2016;65(7):1215–1224.

- Vigne S, Palmer G, Lamacchia C, et al. IL-36R ligands are potent regulators of dendritic and T cells. Blood. 2011;118(22):5813–5823.

- Giannoudaki E, Hernandez-Santana YE, Mulfaul K, et al. Interleukin-36 cytokines alter the intestinal microbiome and can protect against obesity and metabolic dysfunction. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):4003.

- Bachelez H, Choon SE, Marrakchi S, et al. Inhibition of the Interleukin-36 pathway for the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(10):981–983.

- Kanda T, Nishida A, Takahashi K, et al. Interleukin(IL)-36α and IL-36γ induce proinflammatory mediators from human colonic subepithelial myofibroblasts. Front Med. 2015;22(2):69.

- Rieder F, Fiocchi C, Rogler G. Mechanisms, management and treatment of fibrosis in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:340–350.

- Sullivan GP, Davidovich PB, Sura-Trueba S, et al. Identification of small-molecule elastase inhibitors as antagonists of IL-36 cytokine activation. FEBS Open Bio. 2018;8(5):751–763.