We have experienced a time when the majority of trials investigating novel agents for lupus nephritis (LN) did not reach their primary outcomes, despite the pathogenic rationales of the trialed agents were solid and preclinical data robust. Consequently, these negative results raised methodological concerns regarding different aspects of the investigations, including enrollment criteria and study population, SLE heterogeneity, trial design, and endpoints definition [Citation1].

For years, the design of clinical trials investigating novel agents for LN has been based on the paradigm of induction and maintenance phases. New agents, including Immunosuppressants, were mainly trialed as an add-on to induction therapy with the aim to improve renal outcomes compared to standard of care when assessed after 6–12 months of follow-up. The LUNAR trial confirmed this paradigm, failing to prove the efficacy of Rituximab in LN, despite the promising data in both observational and real-life settings [Citation2]. The time has come to finally challenge the concept of the systematic need for both induction and maintenance treatment for LN. When the therapy for LN is started, there should be a dual aim. On one side, the goal for targeting the inflammatory process is limiting kidney injury and to facilitate healing, as well as reducing the SLE activity to ultimately prevent future LN relapses. On the other, minimizing the occurrence of adverse effects related to the prolonged use of immunosuppression and glucocorticoids should be prioritized. Taking these observations into account, novel approaches mainly targeting B-cells have recently demonstrated in randomized studies to be effective and safe options for the management of LN. These approaches have the potential to move forward to a more personalized management of patients with LN and eventually to challenge the traditional scheme of induction and maintenance therapy. Among others, it is worth mentioning the BLISS-LN [Citation3] and the NOBILITY trials [Citation4]. These trials shared some similarities. Firstly, the therapeutic approaches include glucocorticoid and a combination of a conventional immunosuppressive (cyclophosphamide, CYC, or mycophenolate mofetil, MMF) plus an innovative immunosuppressive agent. Secondly, both BLISS-LN and NOBILITY trials incorporated robust glucocorticoid-tapering plans and investigated renal outcomes beyond the typical 12 months (). The success of these trials undoubtedly relies on these methodological mentioned aspects. However, it should be empathized that one peculiarity of these investigations is represented by the prolonged use of biological agents as add-on therapy to conventual background immunosuppression. With the aim of synergistically potentiate the efficacy of Rituximab, while at the same time avoiding the conventional maintenance therapy, we previously reported the promising results of a short-term intensified B cell depletion protocol (IBCDT) [Citation5,Citation6] in patients with severe SLE. IBCDT is a combination of Rituximab (RTX), very low doses of CYC (intended to synergize the lymphocyte depleting effects of RTX), and methylprednisolone pulses (aimed at achieving an immediate anti-inflammatory action). This regimen proved to be effective and well tolerated in a long-term follow-up, despite the absence of any further immunosuppressive therapies. When compared to conventional regimens (induction maintenance) at 12 months, up to 93% of patients treated with IBCDT achieved complete renal response, while 65% and 70% in MMF and CYC-based regimens, respectively. The main strength of this approach relies on the short time of immunosuppression that has been proven to significantly decrease the risk of adverse effects associated to the prolonged use of a combination of steroids and either MMF or CYC, further challenging the paradigm for the need of induction maintenance.

Table 1. Main design characteristics of BLISS-LN, NOBILITY, and IBCDT trials

1. Expert opinion

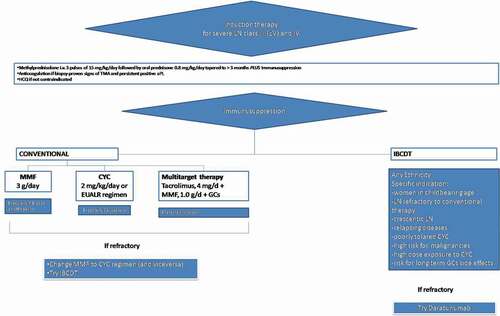

Two conceptually novel approaches are arising in the management of LN. First, using a biological agent at the same dose early and long term has shown successful results in both BLISS-LN and NOBILITY trials. Second, a short-term intensified B-cell depletion protocol has been proved to control disease activity while drastically reducing the total exposure to glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants, albeit future randomized confirmation is required. These experiences challenge the traditional scheme of LN treatments and pave the way to combination therapies of LN as a chronic disease. A possible therapeutic approach is detailed in and summarises the current therapeutic algorithm in place at our centre.

Figure 1. Suggestion of a therapeutic algorithm aiming to a more personalised approach for the management of lupus nephritis. Cyclophosphamide, CYC; mycophenolate mofetil, MMF; glucocorticoids, GCs, LN, lupus nephritis

What have we learned from these trials? The BLISS-LN has shown a consistent effect size up to 12% assessed at 1 year and sustained over a further 12 month-follow-up. As unique for this trial, the effect size was evaluated by Primary Efficacy Renal Response and Complete Renal Response (CRR) definitions that were tailored for this study. When compared to other LN induction trials, outcome measures of positive response include ratio of urinary protein to creatinine of 0.7 or less and an eGFR drop less than 20%. Critically, BLISS-LN did not investigate other endpoints usually considered in LN trials, such as the rate of reduction of proteinuria by 50%. While this might limit results comparability across studies, one should consider BLISS-LN is neither a conventional induction nor a maintenance trial. The mechanisms of action of belimumab support the concept that this agent may actually exert its full effect gradually over time and not necessary accelerate a fast decrease in proteinuria levels early when belimumab has started. With a similar aim, belimumab administration was investigated subsequently to rituximab in order to limit BAFF-driven early B cells repopulation [Citation7]. One could expect that the true added value of belimumab could rely on improving long-term outcomes, e.g. by decreasing the rates of disease flares and improve the maintenance of a sustained remission. Yet, some open questions on the translatability of the results of the BLISS-LN trial into clinical practice have been raised [Citation8]. From this perspective, one should note that clinical benefit for the use of belimumab as add-therapy was mainly observed in the subgroup receiving MMF, not for the group who received CYC as induction therapy [Citation3]. Secondly, cases showing development of active LN during treatment with belimumab in patients who did not have a renal phenotype of SLE prior to belimumab initiation [Citation9] have been reported. In detail, when investigating patients with SLE who received belimumab at five European academic practices, Parodis et al. [Citation9] found 6/66 cases (9.1%) of biopsy-proven de novo LN (4/6 proliferative) among the nonrenal belimumab-treated SLE cases after a median follow-up of 7.4 months.

All in all, even if overall response rates, especially in in certain subset of patients (e.g. patients receiving cyclophosphamide as induction therapy), might have been lower than expected, the BLISS-LN trial represents a unique successful experience in this space.

Thus, proving the net benefit of an add-on biological therapy, a challenge failed by trials exploring the additional value of rituximab, abatacept, and laquinimod [Citation10].

Promising data has been similarly reported by the NOBILITY trial, with an observed effect size for CRR assessed at 76 weeks and as high as 22%. When compared to the LUNAR trail, one should note that glucocorticoids and immunosuppression regimen were less aggressive, probably facilitating the achievement of primary endpoints; nevertheless, consistent with its biological properties, Obinutuzumab seems to have a rapid effect of inducing a sustained CD20 + B cells depletion, even when compared to other B-cell-depleting monoclonal antibodies.

Taken together, both BLISS-LN and NOBILITY suggested the prolonged use of biological agents as add-on therapy to conventual background immunosuppression, being the latest still part of the proposed regimes and continued for years once therapy has started. In the last years, a short intensive B depletion therapy was shown to be safe and effective as the gold standard CYC-based or MMF regimens in controlling LN. Initially tested in refractory cases, the novelty of IBCDT relies on the rate of CRR (even assessed in the long term) despite the lack of an immunosuppressive maintenance regimen. IBCDT remarkably moderates the risk of adverse effects related to the continued use of a combination of glucocorticoids and immunosuppression. Additionally, the biological rational of the IBCDT was confirmed by the observed increase in patients’ Treg number while maintaining a prolonged B-cell depletion [Citation6,Citation7] with a rate of CRR as high as 90% at 1 year with a symptom-free life for more than 120 months.

However, some considerations are worth mentioning when considering differences in trials designs and therapeutic mechanisms of the mentioned schemes. Some limitations in the comparability exist when evaluating the results from an add-on trial design compared to those observed in trials in which different therapeutic schemes are investigated (e.g. IBCDT). Critically, the paradigm of induction-maintenance therapies seems less applicable to ‘add-on’ trials. Similarly, the use of add-on therapies outside the research settings should undergo the conventional regulatory approval. Finally, Although the LUNAR trial failed to meet the primary endpoint, some lessons have been learned from it. In a subsequent a post-hoc analysis Gomez Mendez LM and coworkers [Citation11] showed that the effect might have been dependent on peripheral blood B cell depletion. In line with these observations, a combined IBCDT therapy achieved up to 93% of complete renal response at 12 months while maintaining a prolonged B-cell depletion during the follow-up [Citation6,Citation12]. Besides, LUNAR and NOBILITY trial share some similarities, including drug dosage scheme and time to assess primary outcome (52 weeks). How to move forward and translate these experiences into clinical practice? The challenge for the future is moving from the concept that one therapeutic regime might fit all patients with LN to more tailored, personalized approaches. Data from studies investigating the use of protocolized multiple renal biopsies, along with the availability of reliable biomarkers, will help to identify the subset of LN patients who might benefit from different therapeutic approaches.

Declaration of Interests

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Salmon JE, Niewold TB. A successful trial for lupus - how good is goodEnough? N Engl J Med. 2020 Jan 16;382(3):287–288.

- Rovin BH, Furie R, Latinis K, et al. LUNAR investigator group. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in patients with active proliferative lupus nephritis: the lupus nephritis assessment with rituximab study. Arthritis Rheum. 2012 Apr;64(4):1215–1226.

- Furie R, Rovin BH, Houssiau F, et al. Two-Year, randomized, controlled trial of belimumab in LupusNephritis. N Engl J Med. 2020 Sep 17;383(12):1117–1128.

- Rovin B, Furie R, Aroca G, et al. B-cell depletion and response in a randomized, controlled trial of obinutuzumab for proliferative lupus nephritis [abstract]. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(suppl 3):S352.

- Roccatello D, Sciascia S, Naretto C, et al. A prospective study on long-term clinical outcomes of patients with lupus nephritis treated with an intensified B-cell depletion protocol without maintenance therapy. N Engl J Med. 2021;6(4):1081–1087. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2021.01.027

- Roccatello D, Sciascia S, Baldovino S, et al. A 4-year observation in lupus nephritis patients treated with an intensified B-lymphocyte depletion without immunosuppressive maintenance treatment-Clinical response compared to literature and immunological re-assessment. Autoimmun Rev. 2015 Dec;14(12):1123–1130.

- Atisha-fregoso Y, Malkiel S, Harris KM, et al. CALIBRATE: a phase 2 randomized trial of rituximab plus cyclophosphamide followed by belimumab for the treatment of lupus nephritis[published online ahead of print. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 August 4; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/art.41466.

- Ward M, Tektonidou MG. Belimumab as add-on therapy in Lupus Nephritis. N Engl J Med. 2020 Sep 17;383(12):1184–1185.

- Parodis I, Vital EM, Hassan SU, et al. De novo lupus nephritis during treatment with belimumab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020 Dec 20; keaa796. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa796.

- S. Narain R. Furie Update on clinical trials in systemic lupus erythematosus. CurrOpinRheumatol. 2016;28(5):477–487.

- Gomez Mendez LM, Cascino MD, Garg J, et al. Peripheral Blood B cell depletion after rituximab and complete response in Lupus Nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018 Oct 8;13(10):1502–1509.

- Roccatello D, Sciascia S, Fenoglio A, et al. A new challenge of Lupus Nephritis management: induction therapy without Immunosuppressive maintenance regimen. Autoimmun Rev. 2021;20(7):102844. In press.