ABSTRACT

Introduction

Approximately 20–30% of the patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) may present with isolated proctitis. Ulcerative proctitis (UP) is a challenging condition to manage due to its significant burden in terms of disabling symptoms.

Areas covered

PubMed was searched up to March 2024 to identify relevant studies on UP. A comprehensive summary and critical appraisal of the available data on UP are provided, highlighting emerging treatments and areas for future research.

Expert opinion

Patients with UP are often undertreated, and the disease burden is often underestimated in clinical practice. Treat-to-target management algorithms can be applied to UP, aiming for clinical remission in the short term, and endoscopic remission and maintenance of remission in the long term. During their disease, approximately one-third of UP patients require advanced therapies. Escalation to biologic therapy is required for refractory or steroid dependent UP. For optimal patient care and management of UP, it is necessary to include these patients in future randomized clinical trials.

1. Introduction

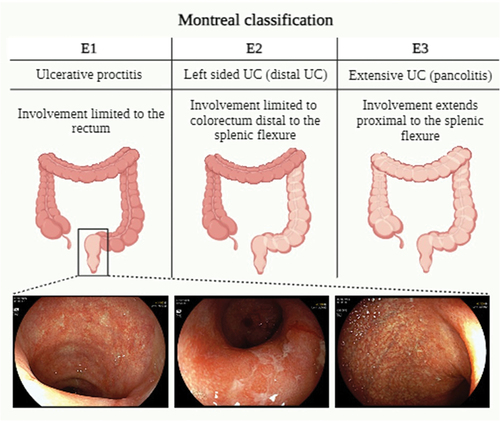

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an inflammatory bowel disease of unknown origin with a multifactorial and immuno-mediated pathogenesis [Citation1]. It manifests as a persistent condition marked by alternating phases of symptoms exacerbation and relief [Citation2]. Typically, the mucosal inflammation in UC starts distally in the rectum and can extend proximally to involve the whole colon in a continuous fashion [Citation3]. According to the Montreal classification (), UC can be subdivided into ulcerative proctitis (E1), with involvement limited to rectum/rectosigmoid junction, left-sided ulcerative colitis (E2), with involvement limited to a portion of colorectum distal to splenic flexure, and extensive ulcerative colitis (E3), with involvement extends proximally to splenic flexure [Citation4]. The extent of the disease affects the treatment plan and the optimal route of drug administration. At the time of diagnosis, 25–55% of the patients exhibit ulcerative proctitis (UP) [Citation5], and usually present highly debilitating symptoms [Citation6].

Figure 1. The Montreal classification of ulcerative colitis.

The most common symptoms described in UP are bloody stools (approximately 86%) and mucus (93%), followed by rectal urgency (43%) [Citation7]. Urgency is currently considered one of the patient-reported outcomes (PROs) mostly associated with compromised quality of life [Citation8], posing the most significant challenge for IBD clinicians. Other typical presentations include loose stools, increased bowel frequency, rectal bleeding, tenesmus, and incontinence as a consequence of chronic inflammation and subsequent scarring, resulting in a noncompliant rectum [Citation9]. Interestingly, a subgroup of patients may present with constipation [Citation10].

Generally, UP follows an indolent course with a good response to topical treatment and a low risk of morbidity/mortality [Citation10] compared with the most frequent aggressive course that characterizes left-sided UC and pancolitis. Furthermore, UP displays an extremely low rate of colectomy at 1, 2, and 5 years after diagnosis [Citation11]. However, UP does not always remain stable over time and can extend proximally assuming a subsequent more severe clinical course and increased risk of morbidity (i.e. hospitalization, drug escalation) and complications (i.e. acute severe UC, dysplasia, colorectal cancer) [Citation12]. Cumulative rates of proximal extension vary from 20 up to 80% progressively after 5 to 20 years of disease [Citation13,Citation14]. The predictable risk factors associated with the development of more extensive forms are as follows: 1) one or more flares in the first year following diagnosis, 2) disease severity at diagnosis, 3) need for corticosteroids at diagnosis, 4) chronic active disease, 5) undertreated and uncontrolled disease [Citation15].

Effective and timely treatment can potentially prevent or delay proximal disease extension and associated short- or long-term complications [Citation16], as well as act on symptom control and improve the quality of life of these patients.

The management of UP primarily involves the use of topical and oral formulations containing 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) and corticosteroids. In general, locally applied 5-ASA preparations have demonstrated greater efficacy compared to oral compounds [Citation17]. When these conventional treatments fail to induce and maintain remission, the UP is defined ‘refractory proctitis’ [Citation9], and its incidence is estimated to be as high as 31%, needing the use of immunomodulators or biological therapies [Citation18].

Risk factors that increase the likelihood of developing refractory disease over time include younger age, male gender, and longer disease duration [Citation19].

Over the past two decades, there has been a significant increase in the treatment options for refractory UP, but evidence of the efficacy of these advanced therapies in UP is limited to a few observational studies due to its exclusion from most randomized controlled trials. Therefore, managing refractory UP remains difficult.

In this review, we aim to summarize the current knowledge on the natural history and pharmacological treatment of UP, and to discuss the advancements and potential gaps of knowledge in the management of UP.

2. Methods

For this narrative review, PubMed was searched up to March 2024. The following text words and corresponding Medical Subject Heading/Entree terms were used: ‘ulcerative proctitis,’ ‘refractory ulcerative proctitis,’ ‘proctitis extension,’ and ‘management’ and/or ‘topical therapy,’ and/or ‘biologic therapy’ to identify pertinent publications exploring the definition, current management, and emerging treatments of UP. A hand-search of abstracts from the annual meetings of Digestive Disease Week, the American College of Gastroenterology, the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization and the United European Gastroenterology Week up to 2024 was also employed. Both animal and human studies were included.

3. Epidemiology, natural history, and disease extension

3.1. Epidemiology

According to a recent consensus, UP is characterized and defined by macroscopic lesions confined to a distance of 15 cm from the anal verge in adults [Citation9]. Considering that the prevalence of UC in 2023 has been estimated at 5 million people worldwide, with a rising global incidence rate, upon presentation already about 30% of the patients have inflammation limited to the rectum alone [Citation20].

As for UC, UP can occur at any age, with a peak incidence between the second and fourth decades of life, with a similar incidence between men and women [Citation21]. Some studies have suggested a bimodal distribution of incidence, with a second smaller peak occurring in the sixth to seventh decade of life, resulting in 10–15% of new diagnoses after 60 years of age [Citation22].

As recent Dutch data show, the incidence of IBD has increased significantly over time, as well as the proportion of UP at their first presentation [Citation23]. In population-based studies, between 22% and 60% of the patients with UC exhibited only UP at the time of diagnosis [Citation24].

3.2. Natural history and disease extension

Despite generally showing a mild disease course, it is known that the cumulative rate of relapse being 42%, 57%, and 84% at 2, 5 and 10 years, respectively [Citation25,Citation26].

The complete understanding of the process by which disease progresses proximally remains elusive. A combination of genetic and environmental factors plays a role in the extension of the disease. To date, several predictive factors of disease extension have been identified (). In a recent retrospective cohort study, in comparison to patients with a BMI below 25 kg/m2, the adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) for disease extension were 1.75 (95% CI, 0.95–3.23) and 2.77 (95% CI, 1.07–7.14) among overweight individuals (BMI of 25–29.9 kg/m2) and obese individuals (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), respectively (p = 0.03) [Citation27]. A twofold increase in the risk of extension was reported in UP patients with previous appendectomy or moderate-to-severe endoscopic activity at the time of diagnosis (adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) = 2.74, 95% CI 1.07–7.01, and aHR = 1.96, 95% CI 1.05–3.67, respectively) [Citation27]. Appendectomy, in this already altered immunological environment, may act as a trigger for more serious disease, and proinflammatory changes in the microbiome that have not yet been explained could occur [Citation28]. Endoscopic severity of disease had been extensively studied as a predictor of extension in UP in several previous retrospective studies [Citation15].

Table 1. Risk factors positively related to proximal disease extension in ulcerative proctitis.

Another cohort study analysis was conducted using data from Swiss IBD to identify potential factors associated with a change in disease extent. Using logistic regression modeling, the following factors were found to be associated with the outcome ‘disease progression:’ treatment with systemic glucocorticoids (OR: 2.077, p = 0.001), treatment with any glucocorticoids (OR: 1.533, p = 0.059), treatment with immunomodulators (OR 1.647, p = 0.011), treatment with TNF antagonists (OR: 1.668, p = 0.022), and treatment with calcineurin inhibitors (OR: 3.159, p < 0.001) [Citation29].

A retrospective study showed a greater tendency toward endoscopic progression in patients who presented one or more flares during the first year than those who had no flares (OR 5.33, 95% CI, 1.55–18.23, p = 0.008), and in patients with a longer period of endoscopic follow-up compared to those with a shorter one (OR 1.01, 95% CI, 1–1.02, p = 0.015) [Citation15].

With respect to histology, the occurrence of histological inflammation (graded according to the Nancy score) in mucosa deemed endoscopically uninflamed at the time of diagnosis was correlated with poorer outcomes in UP patients (adjusted hazard ratio, 4.79; 95% CI 1.10–20.9; p = 0.04) [Citation30].

In addition, the presence of basal plasmacytosis in rectal biopsies obtained during remission in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) has been indeed linked to the likelihood of disease relapse [Citation31].

Conversely, endoscopic and microscopic appendiceal orifice inflammation, considered in some studies as possible predictor of extension [Citation32], has been lately endorsed as having no prognostic implications on proximal disease extension in UP patients [Citation33,Citation34].

Finally, among genetic factors possibly conferring additional susceptibility for extension of UP, MHC genes have been investigated. The MHC class I chain-related gene A (MICA) in particular the MICA-A5.1 allele has been demonstrated to be protective against proximal extension (OR = 3.82, p = 0.015), while MICA-A5 has been linked to a more unfavorable disease progression (OR = 2.4, p = 0.02) [Citation35].

More recently, Argmann and colleagues preliminarily described some of the molecular changes underlying disease extension in UP, specifically investigating genes expression related to IFN signaling in the more proximal biopsy specimens of UP patients compared to healthy controls [Citation36]. In detail, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 14 (PARP14) was identified as a predictive and key driver gene of UP extension [Citation36]. A more prominent activity of PARP14 was found in individuals who subsequently experience UP extension, as opposed to those who do not extend, and immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated increased nuclear expression of PARP14 in inflamed biopsy specimens of UP patients who later extended [Citation36].

These data on genetic susceptibility suggest that certain environmental factors might initiate the extension of the proximal colon in individuals with a genetically permissive makeup [Citation37].

4. Conventional therapy

The immediate objective of treating UP is to achieve remission, with the overarching, long-term goals being the sustenance of remission, improving patients’ quality of life and the prevention of disease proximal advancement. The backbone of UP treatment in mild-to-moderate forms is topical agents (i.e. mesalamine and steroids). The effectiveness and safety of topical therapy have been demonstrated by a vast body of literature, including numerous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses [Citation38].

Topical agents administered rectally are the primary therapeutic choice for proctitis, as they directly address the inflammation site when given sufficient contact time to attain effective mucosal drug concentrations. In fact, higher mucosal drug concentrations have been associated with improved endoscopic and histological outcomes [Citation39].

Furthermore, side effects are infrequent with rectal agents, given their rare association with significant serum concentrations.

Formulations like suppositories, foam, and enema facilitate tailored delivery to the affected mucosa. Suppositories appear more suitable than enemas for proctitis treatment since the concentrate distally, while enemas may reach the splenic flexure and exhibits maximum spread within the range of 11–40 cm from the anal verge, as demonstrated by scintigraphy studies [Citation40–44]. Moreover, suppositories are reported by patients as the preferred formulations compared to enemas and foams [Citation45,Citation46].

Effective treatment of UP is essential to prevent or delay proximal extension of the disease. A retrospective study of 138 patients found that prolonged treatment with oral mesalamine protected against further rectal inflammation [Citation47]. A more recent retrospective study of 116 patients suggested that using a combination of oral and rectal mesalamine was more effective in preventing disease spread than using rectal mesalamine alone [Citation48].

4.1. 5-Aminosalicylates

In a meta-analysis of 11 studies including 778 patients, topical treatment with 5-Aminosalicylates (5-ASA) induced remission in approximately 31–80% (median 67%) of patients with UP and left-sided colitis compared with 7–11% of those who received placebo [Citation49].

The dosage of 1 g daily of 5-ASA suppository has been demonstrated to be equally effective and better tolerated than 500 mg 5-ASA suppository administered twice or thrice daily [Citation50–52].

The efficacy of 5-ASA suppositories was first confirmed in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Japanese study, with an endoscopic remission rate of 83.8% in the 5-ASA suppository arm versus 36.1% in the placebo arm (p < 0.0001), exacerbating the importance of endoscopic remission as a therapeutic goal [Citation53]. Of note, the proportion of patients experiencing no rectal bleeding was notably higher as early as the third day of treatment [Citation53].

The efficacy of topical 5-ASAs in treating proctitis surpasses that of oral 5-ASAs, likely attributed to their rapid transit, reduced contact time with inflamed mucosa, and the comparatively lower drug concentration reaching the rectum [Citation54–56].

In a randomized, single-blind, 4-week trial comparing oral mesalamine (800 mg tablet taken three times daily) with rectal suppository mesalamine (400 mg suppository administered 3 times daily), clinical, endoscopic, and histologic remission rates were significantly higher with suppository mesalamine than with oral mesalamine [Citation55].

Although the drug is the same, the mode of administration and patient compliance should not be overlooked. In this regard, a prospective cohort study evaluated the adherence of 70 patients treated with rectal mesalamine. By interviewing patients, it was found that 55% self-reported occasional nonadherence at the time of enrollment, and surprisingly, 71% of all subjects were found to be nonadherent to the prescribed regimen. The reasons for nonadherence were transanal mode of administration, as opposed to simple oral tablet administration, and hectic lifestyle [Citation57].

However, using a combination of both oral and topical 5-ASA leads to prolonged exposure of the rectum and sigmoid to the active substance and to earlier and deeper remission in left-sided ulcerative colitis [Citation58,Citation59]; still, no dedicated trials have evaluated the combination therapy of topical and oral 5-ASA in UP and the enhanced efficacy and better outcomes are yet to be proven.

4.2. Steroids

In the case of non-response to topical 5-ASA, topical steroids can be used as a second-line therapy and are effective in inducing remission in UP. Corticosteroids that undergo rapid metabolism with low systemic bioavailability, like beclomethasone dipropionate (BDP), led to diminished adrenal suppression when compared to prednisolone enemas [Citation60]. BDP enemas demonstrated comparable efficacy to both prednisolone and topically administered 5-ASA in alleviating symptoms and inducing remission [Citation61].

A combination of topical 5-ASA and steroid treatment could prove advantageous. In a multicenter randomized double-blind study, the effect of BDP enema with 5-ASA enemas and enemas with a combination of BDP/5-ASA was compared. After 28 days of treatment, clinical improvement was 100% with BDP/5-ASA compared with 70% in BDP and 76% in 5-ASA); endoscopic improvement 100% in BDP/5-ASA compared with 75% in BDP) and 71% in 5-ASA); histologic improvement 95% for BDP/5-ASA compared with 50% in BDP and 48% in 5-ASA. After 4 weeks of treatment, 37% of patients treated with BDP/5-ASA were endoscopically healed, compared with 30% of patients treated with BDP and 10% of patients treated with 5-ASA. The combination of BDP and 5-ASA was significantly better than single-agent therapy in improving sigmoidoscopic and histologic scores. The study results indicate that topical treatment with either 5-ASA or BDP is equally effective. However, combination therapy with BDP/5-ASA appears to be superior to single-agent therapy [Citation62].

Budesonide rectal foam demonstrated statistically significant greater effectiveness than a placebo in inducing remission among patients with mild-to-moderate UP and ulcerative proctosigmoiditis (at week 6 of treatment 38.3–44.0% vs. 22.4–25.8%, p < 0.0001), with satisfactory tolerability [Citation62].

Further studies assessed a significantly higher rate of complete endoscopic remission achieved in UP patients receiving budesonide foam twice daily compared to those with once-daily administration or placebo [Citation63,Citation64].

Liquid suspension enemas pose a risk of nonadherence as patients with active disease may struggle to retain larger volumes. Suppositories offer an easier application than enemas, ensuring more precise drug delivery to the rectum, which enemas are less likely to achieve [Citation57]. Budesonide suppositories provide an alternative therapeutic option to mesalamine for the topical treatment of proctitis with high proportions of patients with deep (defined by the improvement of both clinical and endoscopic subscore), clinical, or endoscopic remission [Citation65].

A more recent RCT proved the efficacy, safety, and patient preference of a novel formulation of budesonide suppository (4 mg) in the treatment of mild-to-moderate UP [Citation46]. In deeper detail, in comparison to 2 mg budesonide rectal foams, the 4 mg budesonide suppository fulfilled the predefined non-inferiority criterion for both clinical remission and endoscopic remission (78.8% vs. 74.3%, 81.2% vs. 81.2%, p = 0.00007 and 0.00224, respectively) [Citation65]. The formulation was well received, with only 4.2% of the patients finding that taking it in the morning significantly interfered with their daily routine. Therefore, for patients who do not respond well to or cannot tolerate mesalamine therapy, these new suppositories provide a more attractive option for those suffering from proctitis [Citation65].

4.3. Other topical treatments

Some pilot studies have examined the efficacy and safety of topical calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus). Topical tacrolimus preparations (not commercially available) induced remission in left-sided UC at a low dose of 1.8–4 mg, without causing significant side effects [Citation66]. Two studies reported clinical improvement or remission in patients with left-sided colitis [Citation67,Citation68].

In a case series of patients with inflammation limited to a maximum of 30 cm from the anal verge, after 8 weeks of treatment with topical tacrolimus, 75% achieved remission, with no significant adverse effects [Citation67]. Similar data on clinical improvement and remission in 10/12 proctitis after 4 weeks of local tacrolimus treatment were described in a later series [Citation68].

Finally, in a four-week randomized controlled trial, patients with ulcerative proctitis refractory to 5-ASA exhibited comparable clinical and endoscopic responses when treated with tacrolimus and beclomethasone suppositories [Citation69]. Adverse effects of rectal tacrolimus were confined to the site of administration and included burning, itching, hemorrhoids, and anal fissuring. Systemic exposure to tacrolimus after rectal application was minimal, with 74.2% of the detected levels being undetectable or <5 ng/mL. Overall, no significant systemic adverse safety signals were identified, likely due to limited systemic absorption [Citation69].

Other potential topical therapies for refractory proctitis have been studied, including acetarsol (an arsenic compound with antiprotozoal and antihelminthic properties). A double-blind trial concluded that acetarsol suppositories were as effective as prednisolone suppositories [Citation70]. Retrospective studies have shown that acetarsol may play a role in the therapeutic algorithm for UP and IBD, but the quality of the existing data is considered to be very low. Possible side effects include headache, vomiting, perianal pruritus, paresthesia, blepharitis, sweating, palpitations, and weakness. All short-term side effects disappeared when treatment was stopped, and no malignancies or long-term complications were reported [Citation71].

4.4. Thiopurines

A retrospective noninterventional study assessing the efficacy of immunomodulator therapies [Citation72]. In a retrospective study conducted across three French referral centers between 2002 and 2012, patients receiving azathioprine (AZA) for refractory UP were assessed, and it was found to be effective in maintaining clinical response in 20% of the patients. Of the 1279 patients with UC, 25 were treated with AZA for refractory UP. Of these, four had no short-term clinical evaluation, four were primary non-responders to AZA, seven discontinued AZA for adverse events, and ten showed clinical improvement. At the long-term evaluation, 5 patients had therapeutic success and were still on AZA, while the remaining 20 failed treatment (5 for adverse events and 15 were treated with infliximab) [Citation73].

4.5. Appendectomy

In a prospective case series, 30 adult patients with ulcerative proctitis underwent an appendectomy, in the absence of history suggestive of previous appendicitis, in order to evaluate its potential therapeutic role [Citation74]. After an appendectomy, the clinical activity index, calculated with the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index, improved significantly in 27 out of 30 patients (90%), while the index remained unchanged in the remaining 3 out of 30 patients (10%) [Citation74]. In addition, 12 of 30 patients (40%) had complete resolution of symptoms within 12 months, such that all drug treatments could be discontinued, and remained in remission from all previous treatments for a median of 9 months (range 6–25 months) [Citation74]. The time required for a complete resolution of symptoms after an appendectomy ranged from 1 to 12 months (median 3 months) [Citation74].

In another case series of eight patients treated for refractory ulcerative proctitis, elective appendectomy was performed without symptoms of appendicitis. All patients had a Mayo score at endoscopy of 1 or greater and had healing of the proctitis mucosa, with a follow-up of 3.6 years. Four patients had a single moderate flare-up that responded to topical therapy; four of the eight appendixes removed were macroscopically normal, while the others had a macroscopically inflamed appendix. All patients had signs of acute mucosal inflammation and a transmural neutrophilic infiltrate, typical of acute appendicitis [Citation75].

These studies provided the rationale for conducting controlled trials to properly evaluate the role of appendectomy in the treatment of UP.

5. Advanced therapies

5.1. Biologic therapy

UP that remains active despite rectal and oral therapy with 5-ASA and corticosteroids is termed refractory UP and may require treatment with intravenous steroids, immunomodulators, or biologicals. Meta-analyses have assessed clinical remission rates up to 50–69% for tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor therapies (anti-TNFs) in UP.

Two large randomized double-blind placebo-controlled studies, Active Ulcerative Colitis Trials 1 and 2 (ACT 1 and ACT 2), demonstrated the efficacy of infliximab in inducing and maintaining clinical remission in UC [Citation76,Citation77]. In deeper detail, in the ACT 1 and 2 trials 55% of the patients presented with left-sided or distal colitis [Citation78] but patients with UP were excluded.

Anti-TNFs agents, such as infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab, are drugs approved for use in moderate-to-severe UC. Nevertheless, most prospective randomized controlled trials on anti-TNF therapy excluded patients with UP [Citation79,Citation80].

In a French retrospective cohort study of 104 consecutive UP patients, refractory to conventional therapies, that were treated with anti-TNFs, clinical response and remission rates were assessed by 77% and 50%, respectively () [Citation82]. Moreover, approximately 60% of the treated patients obtained endoscopic remission within 2 years, and continued the treatment over the follow-up [Citation82].

Table 2. Biological and small molecules treatments in patients with ulcerative proctitis.

In a monocentric retrospective study, including 118 patients with UP, 28% required biological therapy [Citation18]. Among these, 42% obtained clinical remission with their initial biological treatment (either anti-TNFs or vedolizumab) [Citation18]. In total, anti-TNF therapy was administered to 26 patients, with remission rates by 50% of the cases after a median follow-up of 21 months () [Citation18].

Similar rates of complete response (69%) and of primary non-responders (15%) was observed in further retrospective studies [Citation81]. In a recent Belgian multicenter retrospective cohort study including 167 refractory UP patients, short-term steroid-free clinical remission was documented in more than one-third of the patients, and was more likely associated with biologicals non-exposure and with vedolizumab treatment (p = 0.001) [Citation84]. In this cohort, UP patients treated with vedolizumab exhibited significantly higher drug persistence (p < 0.001), along with those with a shorter disease duration (p = 0.006) () [Citation84]. Remission rates of treatment with vedolizumab in UP, derived from retrospective cohorts, have been estimated by 65–70% [Citation18,Citation82]. From the UNIFI trials, no reports are available regarding the effectiveness of ustekinumab in UP since patients with disease limited to the rectum were excluded [Citation86].

5.2. Small molecules

Tofacitinib is a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor that selectively targets JAK1 and JAK3. The success of this medication has been established in the treatment of moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis [Citation87]. The efficacy of tofacitinib also as a therapeutic option for refractory UP patients was evaluated in a retrospective multicenter study conducted at 17 centers: the results unequivocally suggest that it is indeed a viable treatment option for these patients. In this study, 35 patients were enrolled who had previously undergone anti-TNF therapy, and 88.6% of them had been exposed to at least two biological lines. After induction (W8-W14), 42.9% and 60.0% of the patients achieved steroid-free remission and clinical response, respectively. At the one-year mark, 39.4% of the patients achieved steroid-free clinical remission and 45.5% achieved clinical response. Additionally, 51.2% (17/33) of the patients were still receiving tofacitinib treatment [Citation83]. Other very encouraging results emerged from a recent prospective cohort study, in which the efficacy of tofacitinib in inducing and maintaining clinical remission was greater in patients with UP, compared with left colitis and pancolitis, with also a lower incidence of adverse effects [Citation88].

Finally, according to a recent meta-analysis, etrasimod, a small-molecule selective sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulator, demonstrated superiority over placebo for both the induction (RR 4.71, 95% CI 1.2–18.49) and maintenance of remission (RR 2.08, 95% CI 1.31–3.32) [Citation38,Citation85]. Importantly, etrasimod has currently been approved for moderate-to-severe UC by regulatory authorities (EMA) and two randomized controlled clinical trials evaluated its efficacy by including a cohort of patients with isolated UP [Citation85].

6. Proctitis in clinical trials

In addition to the fact that most induction and maintenance trials with biologic and small molecules exclude UP patients, among the few available, there is considerable heterogeneity in terms of defining UP itself and endpoints [Citation89]. According to the data updated to 2021 and reviewed in 2023, a total of 53 randomized controlled trials with 4096 UP patients, conducted from 1962–2023, are available [Citation38,Citation89].

Truelove et al. conducted the first uncontrolled clinical trial in 1959 to evaluate the effectiveness of suppositories containing hydrocortisone and prednisolone in treating UP twice daily. Out of 22 patients, 14 of them experienced symptomatic and endoscopic remission, all were free of symptoms within less than 2 weeks [Citation90].

Connell et al. reported the first double-blind controlled study in 1962 of prednisolone suppositories in the treatment of UP twice a night for 3 weeks. In this study, both clinical and endoscopic responses were assessed. Sigmoidoscopic improvement was observed in 75% of the patients treated with prednisolone, while 87.5% of the patients experienced symptomatic improvement [Citation70].

None of the included RCT assessed biological therapy for the treatment of UP. Among small molecules the only RCTs including UP were the ELEVATE trials, where UP patients represented 15% of the total inclusions [Citation85]. Both in the induction and maintenance phase (week 12 and week 52), clinical remission and endoscopic remission was observed in approximately one-third of UP patients treated with etrasimod (p < 0.0001) [Citation85]. Combined endoscopic and histologic improvements were assessed in 21% and 27% of UP patients treated with etrasimod (2 mg/day) after 12 and 52 weeks of treatment, respectively (p < 0.0001) [Citation85].

Several efforts have been made by the scientific community to improve the inclusion of UP in clinical trials and an international expert consensus proposed by the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IOIBD) was recently published [Citation9]. Most of the standardized endpoints currently available for UC have been proposed and adapted to UP. In particular, the endoscopic improvement in UP is defined by a Mayo endoscopic subscore of 0 to 1, and endoscopic remission in UP is defined as a Mayo endoscopic subscore of 0 [Citation9]. Finally, this consensus suggested that disability, fecal incontinence, and urgency should be included as secondary endpoints in dedicated RCTs.

Currently, at least 17 RCTs are registered, specifically addressing UP (https://clinicaltrials.gov/search?cond=Ulcerative%20Proctitis) most of them assessing the efficacy of different topical formulations.

Of note, in the last year some phase III trials (i.e. I6T-MC-AMBZ – ClinicalTrials.gov – NCT05767021) have been specifically designed to address the bowel urgency and quality of life, with attractive endpoints that may potentially apply to patients with UP.

7. Expert opinion

UP remains a demanding condition even for dedicated IBD physicians, especially in terms of management. UP is often under-treated and under-considered according to its extremely limited extension; however, this entity demonstrates that disease location rather than extension is a main determinant of severity and burden of disease.

Despite representing up to 30% of the whole UC patients, both real-world studies and RCTs exploring advanced therapies in UP are scanty.

Recent data showed that, although usually only conventional, and mainly topical treatments are recommended in UP, around one-third of UP patients require advanced therapies during their disease course [Citation91].

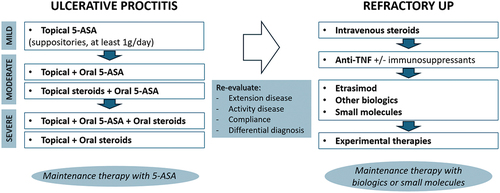

In , we provide a clear explanation of how the UC and treat-to-target management algorithms can be applied to UP [Citation92]. The immediate objective of treating proctitis is to achieve remission, while the overarching aims in the long run involve sustaining remission and halting disease advancement. Re-evaluation after the first or the first enhanced cycle of topical therapy is crucial to distinguishing refractory UP.

Figure 2. A proposed management algorithm for ulcerative proctitis.

Refractory UP owns the same complication rates (i.e. hospitalizations, steroid needs, surgery rates) as UC, requiring a pro-active management and prompt treatment escalation to systemic steroids and/or advanced therapies.

In mild-to-moderate UP long-term maintenance therapy, particularly using topical 5-ASA treatment, is advised. Nonetheless, adherence to long-term topical treatment is often less than optimal. Biologics and small molecules must be considered for maintenance in moderate-to-severe and refractory UP.

Bowel urgency, representing one of the most complained symptoms in UP (reported in 50–60% of the cases) dramatically impacts on quality of life. Notably, bowel urgency can be temporally independent from active disease being reported in up to 88% of UP patients even during their remission’s phases [Citation93]. A main limitation of evaluating bowel urgency during the medical visits, is that it is not included as item in the clinical scores available for UC (i.e. global Mayo score). To date, many efforts have been made to incorporate bowel urgency as a PRO and some numeric scales are under validation [Citation94,Citation95].

With respect to cancer risk, UC disease extent and disease duration are well recognized and independent risk factors in UC-associated dysplasia development. Evidence and guidelines exclude UP patients from regular endoscopic surveillance; still, many open questions remain on the true increased risk of CRC in UP patients and no data are available on the specific risk of rectal cancer in UP.

The precise definition of ulcerative proctitis is still heterogeneous, making it crucial to establish a clear, shared definition. This is important for ensuring that therapies can be compared and for evaluating new treatments to include in studies and endpoints used to measure clinical success. Establishing a clear definition will help generate high-level evidence for managing this clinical condition. To conclude, initial standardized definitions and endpoints are currently available for UP, however additional research is required to refine the methodologies for assessing these outcomes and to validate measurement instruments used for UP patients.

Article highlights

Ulcerative proctitis (UP) can be distinguished as a distinct clinical entity and it is therefore important to define it properly and to assess its incidence and prevalence worldwide.

The aim of treating UP is first to induce symptoms relief, followed by maintaining remission and preventing disease progression.

Mild proctitis can usually be treated with topical 5-ASA as a first-line treatment. For moderate-to-severe proctitis, a combination of oral and topical 5-ASA is recommended. For severe proctitis, topical and oral corticosteroids should be considered.

For refractory proctitis, defined as when conventional therapies fail to improve symptoms, anti-TNF with or without thiopurines in combination, as well as small molecules and other biologics should be used.

Ongoing randomized clinical trials are focused on understanding and improving the management of UP. In the future, priority should be given to including UP in trials to improve the efficacy and specificity of treatment.

Declaration of interests

A Armuzzi has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Amgen, Arena, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Celltrion, Eli-Lilly, Ferring, Galapagos, Gilead, Janssen, MSD, Mylan, Pfizer, Protagonist Therapeutics, Roche, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz and Takeda; speaker’s fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Arena, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli-Lilly, Ferring, Galapagos, Gilead, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, Takeda, and Tigenix; and research support from Biogen, MSD, Takeda, and Pfizer. C Bezzio received lecture fees and served as a consultant for Takeda, MSD, Ferring, AbbVie, Galapagos and Janssen. R Gabbiadini has received speaker’s fees from Pfizer, MSD and Celltrion. A Dal Buono has received speaker’s fees from AbbVie, Galapagos and Celltrion. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed support from AbbVie, Amgen, Celltrion Healthcare, Ferring, Galapagos, Janssen, Lilly, NordicPharma, Pfizer, and Takeda. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Author contributions

Guarantor of the article: A Armuzzi. Author contributions: D De Deo and A Dal Buono performed the research and wrote the manuscript. A Armuzzi, R Gabbiadini, P Spaggiari and C Bezzio critically reviewed the content of the paper. A Armuzzi conceived the subject of the paper, contributed to the critical interpretation, and supervised the project. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Feuerstein JD, Moss AC, Farraye FA. Ulcerative Colitis. Mayo Clin Proc [Internet]. 2019;94:1357–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.01.018

- Adams SM, Close ED, Shreenath AP. Ulcerative colitis: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2022;105(4):406–411.

- Segal JP, Jean-Frédéric LeBlanc A, Hart AL. Ulcerative colitis: an update. Clin Med J R Coll Physicians London. 2021;21(2):135–139. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2021-0080

- Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, et al. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55(6):749–753. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.082909

- Gaweł K, Dąbkowski K, Zawada I, et al. Progression risk factors of ulcerative proctitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2022;57(12):1406–1411. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2022.2094726

- Kiss LS, Lakatos PL. Natural history of ulcerative colitis: current knowledge. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12(10):1390–1395. doi: 10.2174/138945011796818117

- Attauabi M, Madsen GR, Bendtsen F, et al. P238 Symptom burden and indolent disease in newly diagnosed patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease–a Copenhagen IBD inception cohort study. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2022;16:i285–i287. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab232.365

- Sninsky JA, Barnes EL, Zhang X, et al. Urgency and its association with quality of life and clinical outcomes in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(5):769–776. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001685

- Caron B, Abreu MT, Siegel CA, et al. IOIBD recommendations for clinical trials in ulcerative proctitis: the PROCTRIAL consensus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(11):2619–2627.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.02.032

- Michalopoulos G, Karmiris K. When disease extent is not always a key parameter: management of refractory ulcerative proctitis. Curr Res Pharmacol Drug Discov [Internet]. 2022;3:100071. doi: 10.1016/j.crphar.2021.100071

- Burisch J, Katsanos KH, Christodoulou DK, et al. Natural disease course of ulcerative colitis during the first five years of follow-up in a European population-based inception cohort – An Epi-IBD Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13(2):198–208. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy154

- Gajendran M, Loganathan P, Jimenez G, et al. A comprehensive review and update on ulcerative colitis [Internet]. Disease-A-Month. 2019;65(12):100851. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2019.02.004

- Henriksen M, Jahnsen J, Lygren I, et al. Ulcerative colitis and clinical course: results of a 5-year population-based follow-up study (the IBSEN study). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12(7):543–550. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000225339.91484.fc

- Burisch J, Ungaro R, Vind I, et al. Proximal disease extension in patients with limited ulcerative colitis: a Danish population based inception cohort. J Crohn‘s Colitis. 2017;11(10):1200–1204. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx066

- Huguet JM, Ferrer-Barceló L, Suárez P, et al. Endoscopic progression of ulcerative proctitis to proximal disease. Can we identify predictors of progression? Scand J Gastroenterol. [Internet]. 2018;53:1286–1290. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2018.1524026

- Kim B, Park SJ, Hong SP, et al. Proximal disease extension and related predicting factors in ulcerative proctitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49(2):177–183. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.867360

- Kato S, Ishibashi A, Kani K, et al. Optimized management of ulcerative proctitis: when and how to use mesalazine suppository. Digestion. 2018;97(1):59–63. doi: 10.1159/000484224

- Dubois E, Moens A, Geelen R, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with ulcerative proctitis: analysis from a large referral centre cohort. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2020;8(8):933–941. doi: 10.1177/2050640620941345

- Raine T, Verstockt B, Kopylov U, et al. ECCO topical review: refractory inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(10):1605–1620. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab112

- Hochart A, Gower-Rousseau C, Sarter H, et al. Ulcerative proctitis is a frequent location of paediatric-onset UC and not a minor disease: a population-based study. Gut. 2017;66(11):1912–1917. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311970

- Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(6):1785–1794.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.055

- Charpentier C, Salleron J, Savoye G, et al. Natural history of elderly-onset inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study. Gut. 2014;63(3):423–432. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303864

- van den Heuvel Tra, Jeuring SFG, Zeegers MP, et al. A 20-year temporal change analysis in incidence, presenting phenotype and mortality, in the Dutch ibdsl cohort – can diagnostic factors explain the increase in IBD incidence? J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(10):1169–1179. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx055

- Meucci G, Vecchi M, Astegiano M, et al. The natural history of ulcerative proctitis: a multicenter, retrospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(2):469–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.t01-1-01770.x

- Ayres RC, Gillen CD, Walmsley RS, et al. Progression of ulcerative proctosigmoiditis: incidence and factors influencing progression. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8(6):555–558. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199606000-00011

- Anzai H, Hata K, Kishikawa J, et al. Clinical pattern and progression of ulcerative proctitis in the Japanese population: a retrospective study of incidence and risk factors influencing progression. null Dis. 2016;18(3):O97–O102. doi: 10.1111/codi.13237

- Walsh E, Chah YW, Chin SM, et al. Clinical predictors and natural history of disease extension in patients with ulcerative proctitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(11):2035–2041. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001214

- Parian A, Limketkai B, Koh J, et al. Appendectomy does not decrease the risk of future colectomy in UC: results from a large cohort and meta-analysis. Gut. 2017;66(8):1390–1397. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311550

- Safroneeva E, Vavricka S, Fournier N, et al. Systematic analysis of factors associated with progression and regression of ulcerative colitis in 918 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42(5):540–548. doi: 10.1111/apt.13307

- Frias Gomes Cg D, De Almeida ASR, Mendes CCL, et al. Histological inflammation in the endoscopically uninflamed mucosa is associated with worse outcomes in limited ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28(3):350–357. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izab069

- Bitton A, Peppercorn MA, Antonioli DA, et al. Clinical, biological, and histologic parameters as predictors of relapse in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(1):13–20. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.20912

- Anzai H, Hata K, Kishikawa J, et al. Appendiceal orifice inflammation is associated with proximal extension of disease in patients with ulcerative colitis. Null Dis Off J Assoc Coloproctology Gt Null Irel. 2016;18(8):O278–82. doi: 10.1111/codi.13435

- Byeon J-S, Yang S-K, Myung S-J, et al. Clinical course of distal ulcerative colitis in relation to appendiceal orifice inflammation status. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11(4):366–371. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000164018.06538.6e

- Kuk KW, Gwon JY, Soh JS, et al. Clinical significance and long-term prognosis of ulcerative colitis patients with appendiceal orifice inflammation. BMC Gastroenterol. [Internet]. 2022;22(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12876-022-02627-w

- Fdez-Morera JL, Rodrigo L, López-Vázquez A, et al. MHC class I chain-related gene a transmembrane polymorphism modulates the extension of ulcerative colitis. Hum Immunol. 2003;64(8):816–822. doi: 10.1016/S0198-8859(03)00121-6

- Argmann C, Tokuyama M, Ungaro RC, et al. Molecular characterization of limited ulcerative colitis reveals novel biology and predictors of disease extension. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(6):1953–1968.e15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.08.053

- Walker DG, Williams HRT, Kane SP, et al. Differences in inflammatory bowel disease phenotype between south asians and northern Europeans living in north west London, UK. Am J Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2011;106:1281–1289. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.85

- Aruljothy A, Singh S, Narula N, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: medical therapies for treatment of ulcerative proctitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2023;58(8):740–762. doi: 10.1111/apt.17666

- Frieri G, Giacomelli R, Pimpo M, et al. Mucosal 5-aminosalicylic acid concentration inversely correlates with severity of colonic inflammation in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2000;47(3):410–414. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.3.410

- Campieri M, Corbelli C, Gionchetti P, et al. Spread and distribution of 5-ASA colonic foam and 5-ASA enema in patients with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37(12):1890–1897. doi: 10.1007/BF01308084

- Wilding IR, Kenyon CJ, Chauhan S, et al. Colonic spreading of a non-chlorofluorocarbon mesalazine rectal foam enema in patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9(2):161–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00365.x

- Brown J, Haines S, Wilding IR. Colonic spread of three rectally administered mesalazine (Pentasa) dosage forms in healthy volunteers as assessed by gamma scintigraphy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11(4):685–691. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00193.x

- Van Bodegraven AA, Boer RO, Lourens J, et al. Distribution of mesalazine enemas in active and quiescent ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10(3):327–332. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-0673.1996.00327.x

- Brunner M, Vogelsang H, Greinwald R, et al. Colonic spread and serum pharmacokinetics of budesonide foam in patients with mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22(5):463–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02571.x

- Marshall JK, Thabane M, Steinhart AH, et al. Rectal 5-aminosalicylic acid for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD004115. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004115.pub2

- Kruis W, Siegmund B, Lesniakowski K, et al. Novel budesonide suppository and standard budesonide rectal foam induce high rates of clinical remission and mucosal healing in active ulcerative proctitis: a randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16(11):1714–1724. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac081

- Pica R, Paoluzi OA, Iacopini F, et al. Oral mesalazine (5-ASA) treatment may protect against proximal extension of mucosal inflammation in ulcerative proctitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10(6):731–736. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200411000-00006

- Cuomo A, Sgambato D, D’Auria MV, et al. Multi matrix system mesalazine plus rectal mesalazine in the treatment of mild to moderately active ulcerative proctitis. Dig Dis. 2018;36(2):130–135. doi: 10.1159/000485614

- Marshall JK, Irvine EJ. Rectal aminosalicylate therapy for distal ulcerative colitis: a meta‐analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9(3):293–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00384.x

- Lamet M. A multicenter, randomized study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of mesalamine suppositories 1 g at bedtime and 500 mg twice daily in patients with active mild-to-moderate ulcerative proctitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(2):513–522. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1334-y

- Andus T, Kocjan A, Müser M, et al. Clinical trial: a novel high-dose 1 g mesalamine suppository (Salofalk) once daily is as efficacious as a 500-mg suppository thrice daily in active ulcerative proctitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16(11):1947–1956. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21258

- Cohen RD, Woseth DM, Thisted RA, et al. A meta-analysis and overview of the literature on treatment options for left-sided ulcerative colitis and ulcerative proctitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(5):1263–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01940.x

- Watanabe M, Nishino H, Sameshima Y, et al. Randomised clinical trial: evaluation of the efficacy of mesalazine (mesalamine) suppositories in patients with ulcerative colitis and active rectal inflammation – a placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38(3):264–273. doi: 10.1111/apt.12362

- Varum F, Thorne H, Bravo R, et al. Targeted colonic release formulations of mesalazine – a clinical pharmaco-scintigraphic proof-of-concept study in healthy subjects and patients with mildly active ulcerative colitis. Int J Pharm. 2022;625:122055. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2022.122055

- Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Venturi A, et al. Comparison of oral with rectal mesalazine in the treatment of ulcerative proctitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41(1):93–97. doi: 10.1007/BF02236902

- Hebden JM, Blackshaw PE, Perkins AC, et al. Limited exposure of the healthy distal colon to orally-dosed formulation is further exaggerated in active left-sided ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14(2):155–161. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00697.x

- Boyle M, Ting A, Cury DB, et al. Adherence to rectal mesalamine in patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(12):2873–2878. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000562

- Frieri G, Pimpo MT, Palumbo GC, et al. Rectal and colonic mesalazine concentration in ulcerative colitis: Oral vs. oral plus topical treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13(11):1413–1417. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00642.x

- Safdi M, DeMicco M, Sninsky C, et al. A double-blind comparison of oral versus rectal mesalamine versus combination therapy in the treatment of distal ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(10):1867–1871.

- Campieri M, Cottone M, Miglio F, et al. Beclomethasone dipropionate enemas versus prednisolone sodium phosphate enemas in the treatment of distal ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12(4):361–366. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00299.x

- Biancone L, Gionchetti P, Blanco GDV, et al. Beclomethasone dipropionate versus mesalazine in distal ulcerative colitis: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind study. Dig Liver Dis Off J Ital Soc Gastroenterol Ital Assoc Study Liver. 2007;39(4):329–337. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.01.012

- Sandborn WJ, Bosworth B, Zakko S, et al. Budesonide foam induces remission in patients with mild to moderate ulcerative proctitis and ulcerative proctosigmoiditis. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(4):740–750.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.037

- Naganuma M, Aoyama N, Suzuki Y, et al. Twice-daily budesonide 2-mg foam induces complete mucosal healing in patients with distal ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(7):828–836. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv208

- Naganuma M, Aoyama N, Tada T, et al. Complete mucosal healing of distal lesions induced by twice-daily budesonide 2-mg foam promoted clinical remission of mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis with distal active inflammation: double-blind, randomized study. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(4):494–506. doi: 10.1007/s00535-017-1376-4

- Kruis W, Neshta V, Pesegova M, et al. Budesonide suppositories are effective and safe for treating acute ulcerative proctitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2019;17(1):98–106.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.04.027

- Frei P, Biedermann L, Manser CN, et al. Topical therapies in inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion. 2012;86(Suppl. 1):36–44. doi: 10.1159/000341947

- Lawrance IC, Copeland T-S. Rectal tacrolimus in the treatment of resistant ulcerative proctitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(10):1214–1220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03841.x

- van Dieren JM, van Bodegraven AA, Kuipers EJ, et al. Local application of tacrolimus in distal colitis: feasible and safe. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(2):193–198. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20644

- Lie MRKL, Kreijne JE, Dijkstra G, et al. No superiority of tacrolimus suppositories vs beclomethasone suppositories in a randomized trial of patients with refractory ulcerative proctitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2020;18(8):1777–1784.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.09.049

- Connell AM, Lennard-Jones JE, Misiewicz JJ, et al. Comparison of acetarsol and prednisolone-21-phosphate suppositories in the treatment of idiopathic proctitis. Lancet. 1965;1(7379):238. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(65)91523-0

- Argyriou K, Samuel S, Moran GW. Acetarsol in the management of mesalazine-refractory ulcerative proctitis: a tertiary-level care experience. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;31(2):183–186. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001326

- Raja SS, Bryant RV, Costello SP, et al. Systematic review of therapies for refractory ulcerative proctitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. [Internet]. 2023;38(4):496–509. doi: 10.1111/jgh.16111

- Mallet AL, Bouguen G, Conroy G, et al. Azathioprine for refractory ulcerative proctitis: a retrospective multicenter study. Dig Liver Dis [Internet]. 2017;49:280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2016.12.001

- Bolin TD, Wong S, Crouch R, et al. Appendicectomy as a therapy for ulcerative proctitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(10):2476–2482. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.388

- Bageacu S, Coatmeur O, Lemaitre JP, et al. Appendicectomy as a potential therapy for refractory ulcerative proctitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(2):257–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04705.x

- Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2462–2476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050516

- Reinisch W, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, et al. Long-term infliximab maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis: the ACT-1 and -2 extension studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(2):201–211. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21697

- Moss AC, Farrell RJ. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(5):1649–1651. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.039

- Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Marano C, et al. Subcutaneous golimumab induces clinical response and remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(1):85. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.05.048

- Reinisch W, Sandborn WJ, Hommes DW, et al. Adalimumab for induction of clinical remission in moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results of a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2011;60(6):780–787. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.221127

- Bouguen G, Roblin X, Bourreille A, et al. Infliximab for refractory ulcerative proctitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(11):1178–1185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04293.x

- Pineton de Chambrun G, Amiot A, Bouguen G, et al. Efficacy of tumor necrosis factor antagonist treatment in patients with refractory ulcerative proctitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(3):620–627.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.05.060

- Uzzan M, Nachury M, Nuzzo A, et al. Tofacitinib for patients with anti-TNF refractory ulcerative proctitis: a multicenter cohort study from the GETAID. J Crohn’s Coli. 2023;18(3):424–430. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjad169

- Lemmens P, Louis E, Van Moerkercke W, et al. Outcome of biological therapies and small molecules in ulcerative proctitis: a Belgian multicenter cohort study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol [Internet]. 2024;22(1):154–163.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.06.023

- Sandborn WJ, Vermeire S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Etrasimod as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis (ELEVATE): two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies. Lancet. 2023;401(10383):1159–1171. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00061-2

- Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(13):1201–1214. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900750

- López-Sanromán A, Esplugues JV, Domènech E. Farmacología y seguridad de tofacitinib en colitis ulcerosa. Gastroenterología y Hepatología. 2021;44(1):39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2020.04.012

- Singh A, Mahajan R, Midha V, et al. Effectiveness of tofacitinib in ulcerative proctitis compared to left sided colitis and pancolitis. Dig Dis Sci. [Internet]. 2024;69(4):1389–1402. doi: 10.1007/s10620-024-08276-1

- Caron B, Sandborn WJ, Schreiber S, et al. Drug development for ulcerative proctitis: current concepts. Gut. 2021;70(7):1203–1209. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324108

- Truelove SC. Suppository treatment of haemorrhagic proctitis. Br Med J. 1959;1(5127):955–958. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5127.955

- Armuzzi A, Danese S, Barreiro-de Acosta M, et al. P931 burden of disease among ulcerative colitis patients with isolated proctitis in the United States and Europe. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2024;18(Supplement_1):i1694–i1696. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjad212.1061

- Pineton de Chambrun G, Tassy B, Kollen L, et al. Refractory ulcerative proctitis: how to treat it? best pract res clin gastroenterol [Internet]. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;32–33:49–57. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1521691818300258

- Nigam GB, Limdi JK, Bate S, et al. Fecal urgency in ulcerative colitis: impact on quality of life and psychological well-being in active and inactive disease states. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.12.019

- Dubinsky MC, Irving PM, Panaccione R, et al. Incorporating patient experience into drug development for ulcerative colitis: development of the urgency numeric rating scale, a patient-reported outcome measure to assess bowel urgency in adults. J Patient-Reported Outcomes. 2022;6(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s41687-022-00439-w

- Dubinsky MC, Newton L, Delbecque L, et al. Exploring disease remission and bowel urgency severity among adults with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis: a qualitative study. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2022;13:287–300. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S378759