ABSTRACT

Drawing on the theory of representative bureaucracy, which shows that minority bureaucrats will actively represent the interests of minorities from the same socio-demographic group, we argue that institutions could use active representation for institutional performative goals through identity taxation resulting in an unintended outcome of representative labour. We contribute a novel conceptual model of representative labour, enhancing the understanding of the individual–organizational interface, through research involving 35 interviews with academics and professionals, who have a role in addressing gender inequality in British and Irish higher educational institutions through an equality charter award scheme, namely Athena SWAN.

Introduction

According to Park (Citation2021) a future research agenda of gender in public organizations should include interpretive and narrative approaches; identify conditional effects on gender; examine the outcomes of individual–organizational effects; assess gender disparities in the public workplace; and how to achieve equitable representation. Park (Citation2021, 942) states that future research should ‘look beyond mere numbers … to clearly define, conceptualize, and operationalize gender and gender representation to advance our understanding of gender effects in different contexts’. We address this call by going beyond the numbers with an interpretive, qualitative exploratory study to advance the understanding of the individual–organizational interface of gender representation and highlighting gender disparities in the workplace. We conceptualize representative labour as an unintended outcome when women’s active representation, through identity taxation, is not rewarded, but their labour in representing those of the same socio-demographic group is captured to achieve institutional goals rather than equality per se.

Although there has been much research on gender inequality and explanations for the lack of career progression of women in higher education (see Bagilhole and Goode Citation2001; Davies and Thomas Citation2002; Deem Citation2018; Yarrow Citation2021), there is a lack of research on the impact of active representation on the careers and personal lives of women that actively represent women students and faculty (and other minorities). Thus, to explore active representation we draw on the theory of representative bureaucracy as the core theoretical framework underpinning the paper. Specifically, in order to understand the impact on women who actively represent other women, we draw upon the lived experiences of women who have a role in addressing gender inequality in their institutions. We locate the research in the UK and Irish higher education sector since it has a gender equality scheme – Athena SWAN – with the goal of creating a more gender inclusive environment. The gender equality scheme, which has been operational since 2005, is led mostly by women academic and professional staff known as champions for gender equality (Munir et al. Citation2013).

Athena SWAN has been adopted in various forms in several countries (Gibney Citation2017; Schmidt et al. Citation2020) and offers an opportunity to understand the gender effects of equality schemes in multiple contexts (see Park Citation2021). For example, in Australia, the Australian Academy of Science and the Australian Academy of Technology and Engineering adopted Athena SWAN as part of the Science in Australia Gender Equity programme (Schmidt et al. Citation2020). Further, adapted versions of Athena SWAN are being implemented in India, Japan, New Zealand, Sweden and Norway (Caffrey et al. Citation2016; Ovseiko, Godbole, and Latimer Citation2017; Schmidt et al. Citation2020). In the USA, the American Association for the Advancement of Science uses an Athena SWAN approach as part of its STEM Equity Achievement (SEA) Change programme (Schmidt et al. Citation2020). The Canadian government has also announced its commitment to implementing Athena SWAN (see Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Citation2021). Athena SWAN has become an influential global movement (Xiao et al. Citation2020). Globally, although there has been an increasing number of women students and employment of women in higher education sector, the under-representation of senior women faculty is an enduring trend (UNESCO Citation2021). For example, in the UK 73.3% (Advance Citation2021) and in Ireland 76% (Higher Education Authority Citation2018) of professors are men. Data show the under-representation of women at senior academic grades and a ‘leaky pipeline’ of women students into academic careers, particularly in STEMM disciplines (Hirshfield and Glass Citation2018). We acknowledge a limitation of the research is that it draws solely on the UK and Irish context. This may be countered by the fact that Athena SWAN has been implemented in the UK and Ireland since 2005 and as such serving as a context where change and experience are most established.

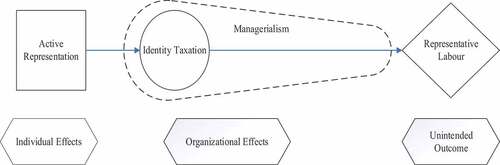

The research sought to answer a two-fold question: (1) does active representation lead to representative labour; (2) and what is the impact of active representation on the careers and lives of champions of equality? At the core of the question is the theory of representative bureaucracy in order to understand the effects of individual–organizational (Park Citation2021) interfaces of active representation on the careers and lives of Athena SWAN champions who actively represent women within educational institutions. The first section of the paper provides a theoretical framing, and the second section contextualizes the research by providing a description of Athena SWAN as a case of equality charter mark schemes within the public sector. Further sections include the research methods and the findings with a discussion thereof. We conclude with a conceptual model that highlights the institutional capture of active representation through identity taxation in the context of managerialism to achieve institutional goals, which has an outcome of representative labour. This serves to be a further deleterious outcome for already marginalized groups.

Representative bureaucracy theory

The theory of representative bureaucracy purports that a bureaucracy that shares the same demographic identity as the public it serves will act in a way that benefits the demographic group (Mosher Citation1968). The premise of representative bureaucracy theory is that shared socio-demographic identities affect decisions made by and actions taken by bureaucrats who share the same socio-demographic identities as beneficiaries of a public organization (Meier and Nicholson-Crotty Citation2006). A bureaucracy is passively representative to the extent that it employs minorities and/or women in numbers proportionate to the share of the population (Bradbury and Kellough Citation2011), while active representation is the extent to which bureaucrats act, consciously or unconsciously, in the interests of citizens who share group identities (Bradbury and Kellough Citation2011). The shared identity is based on demographic and social groups that have the same attitudes, values and beliefs (Pitkin Citation1967).

According to Mosher (Citation1968) passive representation, the proportion of minority bureaucrats employed in a public organization, leads to active representation when a minority bureaucrat makes decisions in the interest of the same minority socio-demographic group. Active representation involves a bureaucrat standing for a socio-demographic group because they share an identity (Pitkin Citation1967) and press for the interests of those that share the same identity (Mosher Citation1968). Thus, while passive representation is the extent to which a public organization includes specified socio-demographic identities within its ranks, active representation is when a bureaucrat acts to see the interests of individuals who share their socio-demographic identities are not overlooked in decisions by the public organization (Bradbury and Kellough Citation2011). Thus, bureaucrats who are women, racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to act in the interests of women, racial or ethnic minorities as beneficiaries of a public service organization.

An important condition for passive representation to lead to active representation is discretionary power (Meier and Bohte Citation2001). Several studies demonstrated that when bureaucrats have the discretion to make decisions, they will do so in the interest of the minority group with a shared identity (Selden Citation1997; Sowa and Selden Citation2003). Furthermore, the salience of a policy issue is important for the translation of passive to active representation (Keiser et al. Citation2002). Thus, women bureaucrats are more likely to actively represent women if the policy affects women; there is a gender identity between the bureaucrat and the public service beneficiary; and there is an issue identified as affecting women (Keiser et al. Citation2002).

Active representation has been demonstrated in research when the passive representation of ethnic minority teachers and administrators in public schools resulted in better outcomes for ethnic minority students (see Meier, Stewart, and England Citation1990; Meier and Stewart Citation1992; Meier, Wrinkle, and Polinard Citation1999). Other studies found that women who were child support officers made decisions that resulted in the increase of child support, benefitting mothers and their children (see Wilkins and Keiser Citation2004; Wilkins Citation2006). Women child support officers as passively represented minority bureaucrats, actively represented the interest of women and their dependent children. Studies have shown that women bureaucrats were more likely to actively represent women if the policy affected women, i.e. there was a gender identity between the bureaucrat and the public service beneficiary (Keiser et al. Citation2002). For example, women police officers acted in the interests of women as victims of gender-based violence (see Meier and Nicholson-Crotty Citation2006; Andrews and Johnston Miller Citation2013). Much of the research has demonstrated positive outcomes of active representation for women and minorities and for public service organizations, such as better performance, responsiveness, and trust and legitimacy (see Riccucci, Van Ryzin, and Lavena Citation2014; Bishu and Kennedy Citation2020; Dantas Cabral, Peci, and Van Ryzin Citation2021; Ding, Lu, and Riccucci Citation2021).

The research is mostly located in the USA with a focus on race or ethnicity, and the benefits to the minority group, the public and public organizations (Bradbury and Kellough Citation2011; Bishu and Kennedy Citation2020). Seldom is there research on the effect of active representation for the minority bureaucrat and their careers. Whilst there have been numerous studies on representative bureaucracy demonstrating the relationship between passive and active representation, and the circumstances under which representation produces positive outcomes for minority groups (Bishu and Kennedy Citation2020), there is a dearth of the literature on the effect of active representation on those who represent women and minorities, and it is here where this research makes a novel empirical and theoretical contribution.

Identity taxation

A psychological theory that sought to examine the effects of representation on minorities was identity taxation, and we therefore draw upon identity taxation theory to further improve our understanding of representation within the individual–organizational interface (see Park Citation2021). Padilla (Citation1994), reflecting on his own experiences as an ethnic minority academic in US universities, observed an imposition of taxation in academia such as assuming that ethnic minorities are best suited for specific tasks because of racial or ethnic background and presumed knowledge of diversity. The taxation took the form of being called upon to (1) be the expert on diversity within the organization although the minority employee may not be knowledgeable on the issues or comfortable in the role; (2) educate the majority group about diversity although this is not part of the job description and not given any authority or recognition for the additional responsibility; (3) serve on committees or task forces with little real structural change to the organization; (4) serve as the liaison between the organization and the ethnic community, but the minority employee may not agree with the organizational policies and its impact on minorities; (5) sacrifice their own work to serve as a problem solver or negotiator for disagreements and (6) to translate official documents or serve as interpreters when non-English-speaking clients, visitors, or dignitaries visit the organization (Padilla Citation1994). However, this did not necessarily lead to rewards, such as promotion, but is seen more as an obligation to demonstrate good citizenship towards the organization or commitment to diversity, which brings recognition to the organization (Padilla Citation1994).

Identity taxation involves bureaucrats of minority or marginalized groups undertaking additional institutional tasks and responsibilities because of their identity. This additional work, i.e. service work, was expected by their institution by virtue of the minority’s identity, but is not rewarded and hence is a taxation (Wijesingha and Ramos Citation2017). Hirshfield and Joseph (Citation2012, 214) argue that identity taxation occurs ‘ … when faculty members shoulder any labour – physical, mental, or emotional – due to their membership in a historically marginalized group within their department or university, beyond that which is expected of other faculty members … ’ Furthermore, this additional labour differentially influences a faculty member’s academic productivity and social integration within the university (Hirshfield and Joseph Citation2012). Hirshfield and Joseph (Citation2012) found that gendered identity taxation is experienced by women faculty in three ways: (1) they felt like tokens; (2) they were expected to take on a greater proportion of mentorship and advising women students than male colleagues and (3) they experienced prejudice and discrimination about their intellectual abilities and skills.

Similarly, Rideau (Citation2019) found that African-American women faculty, within the context of historically white colleges, experienced identity taxation. The women reported being over-burdened with additional, unpaid and unrewarded work (Rideau Citation2019). This work involved caring for marginalized students, over-burdened with institutional services such as being appointed to committees to ensure a diverse composition, and an obligation to teach colleagues about race and racism (Rideau Citation2019). Rideau’s (Citation2019) study also demonstrated that women faculty of colour had to bear the burden of others to the sacrifice of their well-being. Eagan and Garvey (Citation2015) also found that faculty from historically marginalized groups have greater service work and institutional roles, which is more heavily expected from them than peers from the majority group. This over-burden, but undervaluing of institutional service work, revealed significant and positive associations between stress of family obligations and faculty participation in this service work (Eagan and Garvey Citation2015).

Rideau’s (Citation2019, 10) found that rejecting this institutional service work reinforced the gendered notion of women as ‘not being a team player’ or as ‘challenging’. However, accepting identity taxation rarely led to promotion or tenure, but white colleagues were either immune to identity taxation or if they assumed roles on diversity committees were protected, privileged and rewarded (Rideau Citation2019). Wijesingha and Ramos (Citation2017) and Guillaume and Apodaca (Citation2020) also found that institutional service work prevented minorities from achieving promotion and tenure, concluding that promotion and tenure processes do not value service work as much as the evaluative benchmarks of research and teaching. The extant research demonstrates that identity taxation within the public sector workplace has the potential to increase administrative burdens for women and minority bureaucrats who actively represent women and minorities.

Athena SWAN: gendered representative labour?

Athena SWAN, as a gender equality award scheme, offers the opportunity to advance the understanding of the individual–organizational interface between gender representation and gender disparities in the public organizations (see Park Citation2021) and the active representation of women. Athena SWAN seeks to advance the careers of women in academia, led by a champion in an institution, it is an award to institutions for addressing gender inequality in relation to representation and progression of women staff and students. Institutions receive a bronze, silver and gold awards depending on an assessment of the credibility of gender equality data and an action plan to address gender inequality (Barnard Citation2017).

The incentive to apply for an award is recognition within the sector for gender equality is, in part, linked to research funding (Tzanakou and Pearce Citation2019). In 2011, research funding councils made an Athena SWAN award a requirement for research grants (Gibney Citation2017). In 2016, the National Institute for Health Research, a major funder of clinical research, announced that it would no longer provide funding for institutions unless it held an Athena SWAN award (Gregory-Smith Citation2018), and in 2019 Research England announced that as part of the government’s performance assessment of research, the Research Excellence Framework, consequent awarding of quality research funding, universities and research institutes had to evidence equality and diversity with an Athena SWAN award being one such metric. Thus, serving as an example of how Athena SWAN is being mobilized for performance assessments. The European Commission (Citation2022) has made a gender equality plan, modelled on Athena SWAN, an eligibility criterion for research and innovation grant awards. Athena SWAN is therefore being increasingly mobilized around the world and serves to demonstrate the wider international relevance of the findings of this research.

Athena SWAN has however not been without criticism. Munir et al. (Citation2013) for example, found that although Athena SWAN improved opportunities for training and development, and knowledge of promotion processes for women faculty, the scheme did not address persistent barriers and institutional cultural change. Athena SWAN champions, as passive representatives of women, were mostly white women faculty and who reported an administrative burden of undertaking the role, i.e. an increased administrative workload associated with the Athena SWAN role, which became burdensome in addition to teaching and research roles within their institutions (Munir et al. Citation2013; Caffrey et al. Citation2016; Pearce Citation2017; Ovseiko, Godbole, and Latimer Citation2017). For example, Athena SWAN champions saw a dramatic increase in their workload leading to over-time and weekend work (Caffrey et al. Citation2016). According to Caffrey et al. (Citation2016) Athena SWAN reinforced a gendered division of labour in higher education with women engaged in administrative service work. This reinforced gender inequality since women’s participation in championing gender equality disadvantaged their career progress (Caffrey et al. Citation2016). Ovseiko, Godbole, and Latimer (Citation2017) also found Athena SWAN work negatively impacts upon women’s research productivity, which in turn affected their career progression as research is a pathway to promotion. There is little research on the impact of Athena SWAN on student representation and whether it has stemmed the ‘leaky pipeline’. Rosser et al. (Citation2019) in their review of Athena SWAN conclude that while there is no evidence for the impact of Athena SWAN and ADVANCE in the case of the USA on the representation of women faculty and students, it does allow for the benchmarking and tracking of gender across institutions, and for some women it provides an opportunity to demonstrate and develop administrative skills and visibility in their institutions.

Tzanakou and Pearce (Citation2019) argued that Athena SWAN involves moderate feminism where the scheme enables women to make a business case for gender equality with moderate, safe and reasonable arguments leading to the development of new competitiveness metrics in higher educational institutions. In other words, Athena SWAN allows for moderate feminism whereby women can make gender equality gains by appealing to universities’ performative and neoliberal goals. Xiao et al. (Citation2020) examined the relationship between Athena SWAN and university performance, and notably there was greater representation of women in institutions that were not Athena SWAN awardees. They did however show that institutions with awards had a slight increase in women faculty over time, suggesting that the Athena SWAN award has a positive effect (Xiao et al. Citation2020). Thus, although there is mixed evidence of the efficacy of Athena SWAN in achieving gender equality goals, suggestions of identity taxation with regard to administrative burdens, and criticisms of a gendered division and disparities of labour of Athena SWAN work, the impact on champions as active representatives of gender equality deserves further exploration. As Portillo, Humphrey, and Bearfield (Citation2022) argue, the implementation of whiteness and masculinity in public organizations remains underexplored, while the burden of resolving equality issues is placed on marginalized groups. The next section outlines the research method to address our research questions.

Research method

The sample (see ) consisted of 35 Athena SWAN champions from all four nations of the UK and the Republic of Ireland. The sampling procedure was a random sampling of Athena SWAN champions. We included the type of institution in our analysis as Russell Group institutions are more research-intensive universities with more of an imperative to secure Athena SWAN awards given the link to research funding (Gibney Citation2017), and we were interested to explore if there were any effects on the lived experiences of champions in these types of institutions. The skewness of the sample in terms of gender reflects extant research (see Munir et al. Citation2013) that Athena SWAN champions are mostly women. Some men in the sample identified themselves as being from the LGBTQ+ community. As participants, irrespective of the type of institution and position, identified themselves as a marginalized identity and as a champion, comparisons could be drawn as participants could comment on their lived experience as an Athena SWAN champion.

Table 1. Sample descriptives.

The overarching research question of this research was driven by a better need to understand the lived experiences of Athena SWAN champions and the impact of active representation on Athena SWAN champions. We know from existing research that it is disproportionately women and other minority groups that conduct service work, thus predicating identity taxation. We mobilize our interpretation and analysis of active representation, as a part of Athena SWAN work, as a contemporary form of theory building (Doty and Glick Citation1994), and to contribute to existing understandings of representative bureaucracy, and thereby contributing empirically to Park’s (Citation2021) research call of understanding individual–organizational effects on gender representation and gender disparities in the workplace.

Our ontological and epistemological position grounded in subjectivist interpretivism draws on representation as a socially constructed notion and universities as sites of discrimination of minorities (Padilla Citation1994). Our interpretivist approach enabled the collection of in-depth, qualitative insights into Athena SWAN champions’ lived experiences across a range of institutions in the UK and the Republic of Ireland.

This research was conducted during the covid-19 pandemic, and thus all interviews were conducted online, audio recorded and transcribed in full. Participants were selected from the publicly available online list of Athena SWAN champions and using an online random sampling tool to ensure random selection from the sample overall. Semi-structured interviews enabled flexibility for both the covering of the deductive themes, allowing for emergent themes, as well as providing scope for areas to emerge that were not included in the interview guide. Two pilot interviews were conducted prior to the main research being undertaken, which enabled the refining of the interview questions and their suitability. Full ethical approval was gained from the authors’ institution, and all participants were provided with a consent form, as well as a participant information sheet. All participants were anonymized and any identifiers were redacted during the transcription stage in order to provide ethical protection.

All data were analysed within NVivo12 and initially coded into a categorization strategy, followed on by a connecting strategy (Maxwell and Miller Citation2008), to develop insights into the linkages between active representation and identity taxation. Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2019) six phases of thematic analysis were followed in order to ensure a systematic and robust mode of analysis and to further ensure the credibility of the findings (Polit et al. Citation2008). Both researchers cross-checked each other’s coding, refining shared codes and themes through joint agreement (O’Connor and Joffe Citation2020) acting as a peer review of coding. The text of transcripts were coded to the concepts of identity taxation and active representation. The analysis involved a frequency analysis of stem words (e.g. burden, burdensome and over-burdened) and intensity analysis of words. NVivo12 allows for the accessing of text from a frequency and intensity analysis, which enabled the analytical selection of quotes to capture the lived experience of champions (see Appendices).

Findings

Similarly, to extant research, we found that the majority of Athena SWAN work was being undertaken mostly by women. They took on the role, voluntarily or appointed, as Athena SWAN champions to actively represent women and advance gender equality goals. All champions expressed a commitment to active representation. For example, participants stated that they were ‘passionate about gender equality and diversity’ or the role was ‘an opportunity to make a difference or change’ in representing women. However, all participants found the role of champion or undertaking equality work in general to be time-consuming and an administrative burden involving high workloads and bureaucratic red-tape. The most frequently mentioned burden was administrative. This involved time and the arduous task of data collection and analysis, the application process for Athena SWAN awards, implementing action plans and engaging with people or colleagues (see Appendix 1), as a participant stated:

So, Athena Swan becomes this other thing that we, that’s added to the burden in a, in a day where there’s not enough hours in the day already … people are prioritizing teaching, research, networking, and all the other things that they need to do. And I think one of the things Athena Swan fails to do is look at workload balance in an appropriate way.

The quote is a recurrent example of the administrative burden experienced by participants. A further theme was the lack of reward for doing the work that brought recognition to the organization. Many participants spoke of the increased labour and stress involved in an Athena SWAN application and being a champion of gender equality. For example, a participant stated:

I actually have an emotional physiological response just thinking about that. It, it is horrendous and error-prone and, just takes far more time than it should … I’ve grown a little frustrated with it, of course equality and diversity is many things to many people and it, it’s always, the remit seems to be increasing all the time, and whilst I’m sympathetic to all of that, that’s very difficult to manage.

Participants commented on the managing of workloads and associated stress while simultaneously demonstrating they were ‘team players’. The role involved long working hours, an over-burdened workload and work–life conflict, often leading to stress for many participants. A participant reflecting on a fellow champion’s experience stated:

‘ … when she was up at three am in the morning writing the section on flexible working you know, and she said you know it, she said it just seemed absurd to her, and that is, I thought was a brilliant example about that whole you know, how that you know is completely contradictory isn’t it’.

Although champions were committed to actively represent women faculty and students, this came at a cost. The administrative burden created time poverty, a lack of the work–life balance and an opportunity cost to undertake scholarly work such as research. Participants seldom saw rewards for active representation. As the following participants explained:

‘Athena Swan you’ll get, you get a pat on the back but it actually doesn’t mean anything for you as an individual, a job well done but, it gets a kind of well done’

I think the whole recognition and valuing Athena Swan work specifically is still problematic, because I think more and more departments do see it as a sort of significant admin position.

All participants felt that there was an inequity because the administrative burden involved in the application and implementation of action plans were not matched by institutional rewards. Participants’ perceptions and experiences by gender revealed an imbalance of the administrative burden on women, many of whom were not allocated workload hours for their Athena SWAN work, rather the role is often performed as a form of additional labour; a participant stated:

I feel that women tend to volunteer for these roles … whereas men they see it as a means of getting promotion, so they’re seeing as something that will look good on their CV, that’s my personal opinion and, and that’s why they take on this role.

Approximately, 55% of participants expressed such disillusionment and frustration. They often perceived the irony of Athena SWAN, which is supposed to enable the career progression of women, but did not result in them being rewarded with a promotion for their active representation of women. Notably, the majority of participants did not receive a time allowance in their workload for the Athena SWAN work and the work became an additional burden to their academic roles. Of the 35 participants, only three were promoted because of their role in Athena SWAN. With the exception of four participants (three women and one man), most participants did not have positive comments and were critical of their institutions for the lack of reward or recognition for their Athena SWAN work. As a participant stated:

‘ … a real problem because who benefits from the awards, the institution does you know, the women don’t necessarily benefit’

Almost 88% of participants felt that being involved in Athena SWAN came as a career sacrifice. Athena SWAN work distracted from time to devote to research, grant applications and publications, which are rewarded by institutions. Participants felt that Athena SWAN inhibited their chances of promotion and career advancement as described by the following participant:

I was passionate about Athena Swan principles but I think it was a very, very, very demanding role because there was really no support … I had to do all the sort of spade work … and that took a very, very long time, and as I said it took me away from my research, so I had to put my research on the backburner for about a year whilst I totally focused on the submission … the administrative side for me did take a very, very long time, and it took me away from my research.

The following participants, alongside many in the sample, highlighted that the level of involvement and engagement with Athena SWAN is detrimental to individuals’ careers, potentially serving as a multiplier effect and exacerbating existing inequalities:

… it’s damaged the careers of some early middle career people … women, who threw themselves into Athena Swan activities in their departments. We’re not adequately remunerated as it were through work allocation models.

… it’s a huge amount of work that detrimentally impacts on your work … I’m a research member of staff so I’ve got to do teaching, research and admin, and I was thinking well if I didn’t have Athena Swan and I had a whole year sabbatical to do research, like how many grants could I pull in, and how much papers could I put out, and that kind of thing, which you know would be more, perhaps more productive to my career than writing this Athena Swan document.

‘ … it impacts on your ability to do all of the other stuff that would potentially get you promoted or, for a better career, and it becomes deeply frustrating and I guess it becomes a burden … it’s often seen that work’s done altruistically … of course I want academia to be better for myself and for people who come before me, but the fact that I’m having to drive these conversations with very little support in terms of time, resource, and I think often it’s overlooked, and I don’t think that in my school it was recognized as big a job as it actually was’.

Despite Athena SWAN champions actively representing women faculty and students, it did not necessarily result in career rewards, but rather accrued rewards for their respective institutions. A consistent theme that emerged from the interviews is that Athena SWAN was part of a performance ‘metric’ as a managerial exercise to ‘tick a box’ for the institution to be recognized for gender equality (see Appendix 2). Participants expressed the view that Athena SWAN was a ‘badge’ for institutions and were concerned that Athena SWAN was being used to achieve performative ‘targets’ and awards rather than gender equality per se. Participants were of the opinion that although a positive aspect of Athena SWAN was to put gender on the agenda and helped with the rethinking of human resource policies and practices, it did not fundamentally challenge the patriarchy within the organization. Thirty participants made a higher frequency of comments (109 references) on managerialism such as performance management, use of metrics and measurements, accountability and competition in relation to the organizational goal of achieving an Athena SWAN award. A participant encapsulated the sentiment by stating:

… we have a dean who frankly I think is not remotely concerned with equality and diversity, he’d be very happy if he never had to deal with any E&D stuff at all, but start handing out gongs and setting up a competition between universities and he suddenly you know, he’ll buy in for the sake of not wanting to be you know the worse faculty in the country when it comes to Athena SWAN.

For the higher education sector, Athena SWAN became a performative competition where the incentives are reputation and financial rewards. Twelve participants were of the opinion that Athena SWAN became a way to tick an ‘equality box’ which at the same time disproportionately overburdens those for whom it is intended to benefit. Thirty participants viewed Athena SWAN as a performance management exercise of metrics and managerialism to achieve institutional neoliberal goals of financial reward and enhance reputation in an increasingly competitive higher education market. As the following participants stated:

‘ … it gets senior management to take notice, yeah cos you have to kind of go to senior management with the carrot otherwise they’re, with the equality stuff they’ll just be like it doesn’t matter, until you go and say this is important because this means we might get funding through this or, so it does do well for that’.

I’m putting it a little bit bluntly but fundamentally it’s like if this is, if this is something that can enhance or damage our reputation then we’re going to pay attention to it … .

… they really wanted it because it’s still an award, an accolade that they can put on their website to say that they’re, they’re towards better equality and diversity.

Discussion

To address the first research question, the findings suggest that active representation may lead to representative labour if an organization captures active representation through identity taxation for its organizational goals in the form of reputational and financial rewards, rather than achieving equality per se. Thus, while we found that Athena SWAN champions, as passive representatives of women, were passionate to actively represent women and committed to achieving gender equality, institutions captured this additional labour through identity taxation to achieve performative managerial goals. We propose the following conceptual model of representative labour (see ) to contribute to the understanding of the individual–organizational interface to achieve gender equality, which has unintended outcomes of reproducing gender disparities and inequalities in the form of representative labour.

Active representation is when bureaucrats, with no expectation of institutional reward and demands, act in the interest of minorities and there is no institutional expectation or capture of additional labour for institutional benefit. In other words, a bureaucrat who shares the same socio-demographic identity as those they serve, voluntarily acts or exercises discretion in ways that would benefit the socio-demographic group (Mosher Citation1968). In other words, women as passive representatives exercise discretionary power to act in the interests of women. In this case, it is academic and professional women, passive representatives, in an educational institution representing women within the faculty and students to achieve gender equality, that is active representation. However, active representation is captured by an institution through identity taxation to achieve performative managerial goals. We argue that when active representation through identity taxation is captured for performative managerial goals, representative labour occurs. In other words, active representation can be an independent, discretionary act at an individual level, but representative labour occurs when the organization captures active representation to extract additional labour through identity taxation in the context of managerialism to achieve its performative goals. The labour is not rewarded nor does it necessarily address structural gender inequalities and may even reinforce gender disparities through a gendered division of labour and the lack of rewards for active representation. The organizational effects are such that the institution imposes identity taxation and managerialism on a passive representative’s discretionary active representation to achieve institutional goals rather than equality per se. The implication is that that the unintended outcome is representative labour.

The findings show that there is a benefit to the organization in the form of financial rewards and recognition to achieve performative goals (see Deem, Hillyard, and Reed Citation2007). Furthermore, Athena SWAN does not address patriarchy (Tzanakou and Pearce Citation2019) or structural power inequalities, such as the gender pay gap and sexual harassment (Tsouroufli Citation2019), and as research has shown there is a ‘leaky pipeline’ and paucity in women career progression in universities. Participants commented on links between managerialism, performance management, ‘macho’ management and organizational patriarchy (see Thomas and Davies Citation2002; Deem, Hillyard, and Reed Citation2007). Thus, the implication is that, despite Athena SWAN champions’ active representation, their work is not rewarded nor does it address institutional structural barriers such as gender disparities and managerialism, which reproduces and serves to further entrench gender inequalities. In other words, Athena SWAN reinforces a gendered division of labour in higher education (Caffrey et al. Citation2016).

Extant research in the higher education sector has shown sufficient evidence of managerialism which reproduces gender inequality within the sector (see Davies and Thomas Citation2002; McTavish, Miller, and Pyper Citation2006; Deem Citation2018; Mastracci and Bowman Citation2015; Jones et al. Citation2020). For example, Shin and Jung’s (Citation2014) study of higher education systems across 19 countries found that managerialism impacts upon academics’ quality of working life and that more market-driven and competition-orientated countries are in the high-stress group with poor quality of working life. Thomas and Davies (Citation2002) argue that in the higher education sector increased academic stress and lower work–life balance is due to managerialism, which encompasses masculinity of competition and performative pressure. The gendered subtext of academia is a context marred by competitive masculinity, characterized by long working hours, visibility, self-sacrifice and a lone, unencumbered academic with no other commitments beyond work (Thomas and Davies Citation2002), managerialism and an audit culture, which negatively impact women because institutions evaluate motherhood as an interruption of productivity (Santos Citation2016). Athena SWAN champions expressed the view that Athena SWAN has become a ‘tick box’ exercise to satisfy a performative culture of metrics and audits, with women’s productivity captured to achieve managerial goals.

To address the second research question, the findings show that although all participants expressed a commitment to gender equality and hence an active representative role as Athena SWAN champions, the administrative and workload burden came as a personal and career sacrifice. Those involved in Athena SWAN work reiterated the burden of active representation at the expense of productivities (e.g. research publications), which they recognized is more valued by the organization and more likely to contribute to career progression (see Weisshaar Citation2017; Guillaume and Apodaca Citation2020). The implication is that Athena SWAN ironically is supposed to advance the careers of women in the academy and address gender inequality, yet as the research shows it negatively impacts upon women’s careers in academia, reproducing gender inequality.

Arguably, Athena SWAN could be considered as part of a performative culture (see Deem, Hillyard, and Reed Citation2007) with performance metrics, data and quantifiable targets creating a technical abstraction and so-called ‘objective’ and ‘neutral’ measurements, which turns employees into governable subjects (Jones et al. Citation2020; Taberner Citation2018). Athena SWAN does not necessarily address structural power inequalities but has the unintended outcome of representative labour for women. We therefore conceptualize representative labour as the capture of active representation through identity taxation by managerialism, to the cost of the minority bureaucrat, but to the benefit of the public organization to achieve performative goals. The findings suggest the active representative labour of women, who conduct the majority of Athena SWAN work, which often increased their administrative and workloads burdens, but who continue to be disadvantaged, paid less than their male counterparts against a background of vertical and horizontal gender segregation (Johnston, Citation2019) and managerialism (Deem, Hillyard, and Reed Citation2007). Portillo, Humphrey, and Bearfield (Citation2022) argue that despite the volume of representative bureaucracy research, scholars have failed to recognize the harm marginalized communities and public servants face, resulting in incomplete understandings of the systemic problem of underrepresentation.

Conclusion

While there has been much research on representative bureaucracy, there has been less research on the impact of active representation on those that champion equality. In the case of Athena SWAN, a gender charter mark equality scheme increasingly being implemented in the higher education sector across the world, shows that the active representation of women through identity taxation is captured by institutions to achieve performative goals leading with the unintended outcome of representative labour. We therefore contribute to the theoretical and contemporary understandings of the unintended outcomes of active representation, which can be captured to benefit institutions in terms of accolades and awards for the purpose of accreditation and reputation.

We believe representative labour has important public management and policy implications as equality and diversity policies are increasingly being adopted and implemented in public organizations. The first implication is caution should be exercised to avoid representative labour of women and minorities, and secondly, organizations should recognize active representation, avoid identity taxation, reward and actively value those engaged in active representation, or risk representative labour, and further entrench existing inequalities. Furthermore, affecting women’s productivity and social integration within an institution (Hirshfield and Joseph Citation2012), and in the longer term, women’s progression to senior and leadership positions; representative labour is at odds with the aims and objectives of equality and diversity schemes. Thus, as a practical implication it is suggested that active representation be institutionally valued and rewarded.

In this paper, we contribute to the theory of representative bureaucracy by demonstrating that there is the potential for unintended outcomes if active representation is captured by an organization for the benefit of its performative goals. The research makes an original theoretical and empirical contribution by identifying and evidencing representative labour, its impact, developing a conceptual model, and conceptualizing representative labour. It is suggested that future research should explore the conceptual model with regard to intersectional identities, and in other public sector and international contexts.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (387.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2022.2126881

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Karen Johnston

Karen Johnston is Professor of Organisational Studies at the University of Portsmouth with a research focus on public management, governance, representative bureaucracy and gender. She has published in peer-reviewed, highly respected journals and books. Prof. Johnston was made a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences for her contribution to the study of gender equality in public management, and in 2018, the American Society for Public Administration awarded me the prestigious Julia J. Henderson award for my outstanding contribution to public administration scholarship.

Emily Yarrow

Emily Yarrow is Senior Lecturer in Management and Organisations at the Newcastle University Business School. Her research is focused on human resource management, equality and diversity, organizational behaviour/theory, and cross-cultural management. To date, my work has focused on the impact of research evaluation on female academic careers (exploring the UK Research Excellence Framework), pensions and the experiences of older workers, and human resource management (HRM) practices more broadly. Her work contributes to contemporary understandings of gendered organizational behaviour and women’s lived experiences of organizational life, which has been published in peer-reviewed, quality journals.

References

- Advance, HE. 2021. ”Equality + Higher Education Staff Statistical Report 2020.”Accessed June 14 2021. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/equality-higher-education-statistical-report-2020.

- Andrews, R., and K. Johnston Miller. 2013. “Representative Bureaucracy, Gender and Policing: The Case of Domestic Violence Arrests.” Public Administration 91 (4): 998–1014. doi:10.1111/padm.12002.

- Bagilhole, B., and J. Goode. 2001. “The Contradiction of the Myth of Individual Merit, and the Reality of a Patriarchal Support System in Academic Careers: A Feminist Investigation.” European Journal of Women’s Studies 8 (2): 161–180. doi:10.1177/135050680100800203.

- Barnard, S. 2017. ”The Athena SWAN Charter: Promoting Commitment to Gender Equality in Higher Education Institutions in the UK.” In Gendered Success in Higher Education, edited by K. White, P. O’Connor, K. White, and P. O’Connor 155–174. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 10.1057/978-1-137-56659-1_8.

- Bishu, S., and A.R. Kennedy. 2020. “Trends and Gaps: A Meta-Review of Representative Bureaucracy.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 40 (4): 559–588. doi:10.1177/0734371X19830154.

- Bradbury, M., and J.E. Kellough. 2011. “Representative Bureaucracy: Assessing the Evidence on Active Representation.” The American Review of Public Administration 41 (2): 157–167. doi:10.1177/0275074010367823.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Caffrey, L., D. Wyatt, N. Fudge, H. Mattingley, C. Williamson, and C. McKevitt. 2016. “Gender Equity Programmes in Academic Medicine: A Realist Evaluation Approach to Athena SWAN Processes.” BMJ Open 6 (9): 012090. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012090.

- Dantas Cabral, A., A. Peci, and G.G. Van Ryzin. 2021. “Representation, Reputation and Expectations Towards Bureaucracy: Experimental Findings from a Favela in Brazil.” Public Management Review 1–26. doi:10.1080/14719037.2021.1906934.

- Davies, A., and R. Thomas. 2002. “Managerialism and Accountability in Higher Education: The Gendered Nature of Restructuring and the Costs to Academic Service.” Critical Perspectives on Accounting 13 (2): 179–193. doi:10.1006/cpac.2001.0497.

- Deem, R. 2018. “The Gender Politics of Higher Education.” In Handbook on the Politics of Higher Education, edited by B. Cantwell, H. Coate, and R. King, 431–448. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781786435026.00035

- Deem, R., S. Hillyard, and M. Reed. 2007. Knowledge, Higher Education, and the New Managerialism: The Changing Management of UK Universities. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199265909.001.0001.

- Ding, F., J. Lu, and N.M. Riccucci. 2021. “How Bureaucratic Representation Affects Public Organizational Performance: A Meta‐analysis.” Public Administration Review 81 (6): 1003–1018. doi:10.1111/puar.13361.

- Doty, D. H., and W. H. Glick. 1994. “Typologies as a Unique Form of Theory Building: Toward Improved Understanding and Modelling.” Academy of Management Review 19 (2): 230–251. doi:10.5465/amr.1994.9410210748.

- Eagan, M., Jr, and J. Garvey. 2015. “Stressing Out: Connecting Race, Gender, and Stress with Faculty Productivity.” The Journal of Higher Education 86 (6): 923–954. doi:10.1080/00221546.2015.11777389.

- European Commission. (2022). “The Commission’s Gender Equality Strategy.” Accessed July 11 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/info/research-and-innovation/strategy/strategy-2020-2024/democracy-and-rights/gender-equality-research-and-innovation_en#gender-equality-plans-as-an-eligibility-criterion-in-horizon-europe

- Gibney, E. 2017. “UK Gender Equality Scheme Spreads Across the Globe.” Nature News and Comment 549: 1–3. doi:10.1038/549143a.

- Gregory-Smith, I. 2018. “Positive Action Towards Gender Equality: Evidence from the Athena SWAN Charter in UK Medical Schools.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 56 (3): 463–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjir.12252

- Guillaume, R., and E. Apodaca. 2020. “Early Career Faculty of Color and Promotion and Tenure: The Intersection of Advancement in the Academy and Cultural Taxation.” Race Ethnicity and Education 1–18. doi:10.1080/13613324.2020.1718084.

- Higher Education Authority. 2018. Higher Education Institutional Staff Profiles by Gender. Accessed June 4, 2021. https://hea.ie/assets/uploads/2018/01/Higher-Education-Institutional-Staff-Profiles-by-Gender-2018.pdf

- Hirshfield, L.E., and E. Glass. 2018. “Scientific and Medical Careers: Gender and Diversity.” In Handbook of the Sociology of Gender. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research, edited by B. Risman, C. Froyum, and W. Scarborough, 479–491. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-76333-0_35.

- Hirshfield, L., and T. Joseph. 2012. “‘We Need a Woman, We Need a Black Woman’: Gender, Race, and Identity Taxation in the Academy.” Gender and Education 24 (2): 213–227. doi:10.1080/09540253.2011.606208.

- Johnston, K. 2019. “Women in Public Policy and Public Administration?” Public Money & Management 39 (3): 155–165. doi:10.1080/09540962.2018.1534421.

- Jones, D.R., M. Visser, P. Stokes, A. Örtenblad, R. Deem, P. Rodgers, and S.Y. Tarba. 2020. “The Performative University: ‘Targets,’ ‘Terror’ and ‘Taking Back Freedom’ in Academia.” Management Learning 51 (4): 363–377. doi:10.1177/1350507620927554.

- Keiser, L.R., V.M. Wilkins, K.J. Meier, and C.A. Holland. 2002. “Lipstick and Logarithms: Gender, Institutional Context, and Representative Bureaucracy.” The American Political Science Review 96 (3): 553–564. doi:10.1017/S0003055402000321.

- Mastracci, S., and L. Bowman. 2015. “Public Agencies, Gendered Organizations: The Future of Gender Studies in Public Management.” Public Management Review 17 (6): 857–875. doi:10.1080/14719037.2013.867067.

- Maxwell, J. A., and B. A. Miller. 2008. “Categorizing and Connecting Strategies in Qualitative Data Analysis.” In Handbook of Emergent Methods, edited by S. N. Hesse-Biber and P. Leavy, 461–477. New York: The Guilford Press.

- McTavish, D., K. Miller, and R. Pyper. 2006. “Gender and Public Management: Education and Health Sectors.” In Women in Leadership and Management, edited by D. McTavish and K. Miller, 181–203. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Meier, K.J., and J. Bohte. 2001. “Structure and Discretion: Missing Links in Representative Bureaucracy.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 11 (4): 455–470. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a003511.

- Meier, K.J., and J. Nicholson-Crotty. 2006. “Gender, Representative Bureaucracy, and Law Enforcement: The Case of Sexual Assault.” Public Administration Review 66 (6): 850–860. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00653.x.

- Meier, K.J., and J. Stewart Jr. 1992. “The Impact of Representative Bureaucracies: Educational Systems and Public Policies.” The American Review of Public Administration 22 (3): 157–171. doi:10.1177/027507409202200301.

- Meier, K.J., J. Stewart, and R.E. England. 1990. Race, Class, and Education: The Politics of Second-Generation Discrimination. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Meier, K.J., R.D. Wrinkle, and J.L. Polinard. 1999. “Representative Bureaucracy and Distributional Equity: Addressing the Hard Question.” The Journal of Politics 61 (4): 1025–1039. doi:10.2307/2647552.

- Mosher, F. C. 1968. Democracy and the Public Service. New York, NY: Oxford University.

- Munir, F., C. Mason, H. McDermott, J. Morris, B. Bagilhole, and M. Nevill. 2013. Advancing Women’s Careers in Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics and Medicine: Evaluating the Effectiveness and Impact of the Athena SWAN Charter. London: Equality Challenge Unit.

- Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. 2021. Made-In- Canada Athena SWAN Consultation. Accessed July 22, 2021. https://www.nserc-crsng.gc.ca/NSERC-CRSNG/EDI-EDI/Athena-SWAN_eng.asp

- O’Connor, C., and H. Joffe. 2020. “Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 19: 1609406919899220. doi:10.1177/1609406919899220.

- Ovseiko, P.V., R.M. Godbole, and J. Latimer. 2017. “Gender Equality: Boost Prospects for Women Scientists.” Nature 542 (7639): 31. doi:10.1038/542031b.

- Padilla, A.M. 1994. “Research News and Comment: Ethnic Minority Scholars; Research, and Mentoring: Current and Future Issues.” Educational Researcher 23 (4): 24–27. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1176259.

- Park, S. 2021. “Gender and Performance in Public Organizations: A Research Synthesis and Research Agenda.” Public Management Review 23 (6): 929–948. doi:10.1080/14719037.2020.1730940.

- Pearce, R. 2017. Certifying Equality? Critical Reflections on Athena SWAN and Equality Accreditation. Coventry: Centre for the Study of Women and Gender.

- Pitkin, H. 1967. The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Polit, D. F., and C. T. Beck. 2008. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. 8th. D. F. Polit and C. T. Beck. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

- Portillo, S., N. Humphrey, and D.A. Bearfield. 2022. “Representative Bureaucracy Theory and the Implicit Embrace of Whiteness and Masculinity.” Public Administration Review 82 (3): 594–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13477

- Riccucci, N. M., G. G. Van Ryzin, and C. F. Lavena. 2014. “Representative Bureaucracy in Policing: Does It Increase Perceived Legitimacy?” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 24 (3): 537–551. doi:10.1093/jopart/muu006.

- Rideau, R. 2019. “‘We’re Just Not Acknowledged’: An Examination of the Identity Taxation of Full-Time Non-Tenure-Track Women of Color Faculty Members.” Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 14 (2): 161–173. doi:10.1037/dhe0000139.

- Rosser, S.V., S. Barnard, M. Carnes, and F. Munir. 2019. “Athena SWAN and ADVANCE: Effectiveness and Lessons Learned.” TThe Lancet 393 (10171): 604–608. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33213-6.

- Santos, G.G. 2016. “Career Barriers Influencing Career Success: A Focus on Academics’ Perceptions and Experiences.” Career Development International 21 (1): 60–84. doi:10.1108/CDI-03-2015-0035.

- Schmidt, E.K., P.V. Ovseiko, L.R. Henderson, V. Kiparoglou, L. Wolfenden, F. van Nassau, and N. Orr. 2020. “Intervention Scalability Assessment Tool: A Decision Support Tool for Health Policy Makers and Implementers.” Health Research Policy and Systems 18 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1186/s12961-020-0527-x.

- Selden, S.C. 1997. The Promise of Representative Bureaucracy. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

- Shin, J.C., and J. Jung. 2014. “Academics Job Satisfaction and Job Stress Across Countries in the Changing Academic Environments.” Higher Education 67 (5): 603–620. doi:10.1007/s10734-013-9668-y.

- Sowa, J.E., and S.C. Selden. 2003. “Administrative Discretion and Active Representation: An Expansion of the Theory of Representative Bureaucracy.” Public Administration Review 63 (6): 700–710. doi:10.1111/1540-6210.00333.

- Taberner, A.M. 2018. “The Marketisation of the English Higher Education Sector and Its Impact on Academic Staff and the Nature of Their Work.” International Journal of Organizational Analysis 26 (1): 129–152. doi:10.1108/IJOA-07-2017-1198.

- Thomas, R., and A. Davies. 2002. “Gender and New Public Management: Reconstituting Academic Subjectivities.” Gender, Work & Organization 9 (4): 372–397. doi:10.1111/1468-0432.00165.

- Tsouroufli, M. 2019. ”An Examination of the Athena SWAN Initiatives in the UK: Critical Reflections.” In Strategies for Resisting Sexism in the Academy, edited by G. Crimmins 35–54. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tzanakou, C., and R. Pearce. 2019. “Moderate Feminism Within or Against the Neoliberal University? The Example of Athena SWAN.” Gender, Work, and Organization 26 (8): 1191–1211. doi:10.1111/gwao.12336.

- UNESCO. 2021. Women in Higher Education: has the female advantage put an end to gender inequalities?. Accessed March 8, 2021. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377182.

- Weisshaar, K. 2017. “Publish and Perish? An Assessment of Gender Gaps in Promotion to Tenure in Academia.” Social Forces 96 (2): 529–560.

- Wijesingha, R., and H. Ramos. 2017. “Human Capital or Cultural Taxation: What Accounts for Differences in Tenure and Promotion of Racialized and Female Faculty?” CCanadian Journal of Higher Education/revue Canadienne d’enseignement Supérieur 47 (3): 54–75. https://doi.org/10.7202/1043238ar

- Wilkins, V M. 2004. Linking Passive and Active Representation by Gender: The Case of Child Support Agencies. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 16(1): 87–102. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mui023.

- Wilkins, V. M. 2006. “Exploring the Causal Story: Gender, Active Representation, and Bureaucratic Priorities.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 17 (1): 77–94. doi:10.1093/jopart/muj012.

- Wilkins, V.M., and L.R. Keiser. 2004. “Linking Passive and Active Representation by Gender: The Case of Child Support Agencies.” JJournal of Public Administration Research and Theory 16 (1): 87–102. doi:10.1093/jopart/mui023.

- Xiao, Y., E. Pinkney, T.K.F. Au, and P.S.F. Yip. 2020. “Athena SWAN and Gender Diversity: A UK-Based Retrospective Cohort Study.” BMJ Open 10 (2): e032915. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032915.

- Yarrow, E. 2021. “Knowledge Hustlers: Gendered Micro‐politics and Networking in UK Universities.” British Educational Research Journal 47 (3): 579–598. doi:10.1002/berj.3671.