ABSTRACT

Little evidence is available on the gendered dimensions of fisherfolk migration beyond the view that it is mainly male fishers who migrate. This article investigates how the gendered experience of fisherfolk migration influences societal change in the fishing communities of Lake Victoria, East Africa. It draws on primary data from several studies, supplemented by secondary sources, to report on the gendered experience of fisherfolk migration and implications of this for fishing households and communities. Lake Victoria is bordered by three countries, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda, and about 50% of boat crew move between landing sites over the course of a year. Movement into and around the fisheries over time has led to a situation of dynamic social norms and practices, abandoning more traditional norms such as those associated with women’s domestic rather than economic roles and contributing to the practice of transactional sex for access to fish. Fishing communities are also affected by changing population size, as limited provision of public services and development is attributed to local government perceptions of fluctuations in population resulting from the migration of male fishers.

1. Introduction

Fisherfolk in many parts of the world are reported to move within and between water bodies in search of better fish catches and prices, away from their main fishing site for months at a time. The ability to move fishing activities is possible in many contexts because fishing grounds often operate as open access and governance controlling access and use rights is absent or weak (Njock & Westlund, Citation2010; Wanyonyi,

Wamukota, Mesaki et al., Citation2016). Such movement is facilitated by social networks and capital, with friends, relations and associates assisting migrating fishers to gain physical access to fisheries as well as to housing in new locations, and enabling acceptance of the migrants within established communities. Fishing communities are affected by the departure and arrival of fisherfolk, as the population size and composition changes and the arrival of newcomers may alter social norms and relations. This suggests that gendered relations and norms will be affected by and will influence both the movement of fisherfolk and how such movement affects fishing communities. Whilst there is evidence of a range of impacts resulting from fisherfolk migration (Njock & Westlund, Citation2010; Wanyonyi, Wamukota, Tuda et al., Citation2016), there is limited discussion on how migration in fisheries results in societal change, including from a gendered perspective. The focus of this article is to address this gap, investigating how the gendered experience of fisherfolk migration influences societal change in the fishing communities of Lake Victoria, East Africa.Lake Victoria was chosen as a case study as its fisheries are extremely important for the three countries that border the lake, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. Lake Victoria is the second largest freshwater body in the world and three main commercial fisheries are associated with the lake: Nile perch, Lates niloticus, Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, and the smaller, sardine-like cyprinids known as dagaa, Rastrineobola argentea. Most of the Nile perch is bought by fish agents on behalf of fish processing factories, with fresh and frozen fillets and other products being exported, principally to Europe. The Nile perch industry boomed in the 1990s, following the introduction of Nile perch into the lake in the 1950s, leading to the establishment of processing plants and reducing access to Nile perch for local processors, many of whom were women (Abila & Jansen, Citation1997). The lake fisheries are estimated to employ 800,000, around 200,000 of whom are male fishers, a category including both boat owners and boat crew, or labourers, (LVFO, Citation2015) and around 50% of the boat crew move between fish landing sites, motivated by higher fish catches and prices elsewhere and to avoid bad weather conditions (Nunan, Citation2010). Migration of fisherfolk is highly gendered, as are the fishing communities, with gendered relations and norms influencing occupation, practices and livelihood outcomes.

The article draws on data collected from several studies and from published literature. The studies drawn on are: a lakewide qualitative study conducted in 2007 on the effects of migration of fisherfolk for the structures and practice of fisheries co-management and livelihoods, reported on in Nunan (Citation2010) and Nunan et al. (Citation2012); a large-scale survey conducted in 2008 under the remit of the Implementation of a Fisheries Management Plan project of the Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation (LVFO), to generate baseline socio-economic information for the project; and, mixed-methods research conducted in 2015 in the three countries at 18 landing sites in total that generated data on the personal networks of fisherfolk and on their occupational experience, reported on in Nunan et al. (Citation2018) and Nunan and Cepić (Citation2020).

2. Gender and migration in fisheries

Migration can take many forms, characterised in particular by duration and destination. It may be permanent, temporary, seasonal, circular, international, national or local, short-term or long-term (Njock & Westlund, Citation2010). The form and duration of migration influences the nature and extent of influence that migration has on societal change in both the communities left behind and in the destination communities. Of particular relevance to the nature and extent of societal change associated with fisherfolk migration is the gendered dimension of migration. Fisherfolk migration has tended to be discussed in terms of the experience of ‘fishers’ or ‘fishermen’ (Duffy-Tumasz, Citation2012; Wanyonyi, Wamukota, Mesaki et al., Citation2016; Wanyonyi, Wamukota, Tuda et al., Citation2016). Where women are discussed, it has been observed that women are less likely to migrate than men and, when they do, it is either associated with their involvement in fish trade or because they are accompanying their husbands (Njock & Westlund, Citation2010). As Weeratunge et al. (Citation2010, p. 410) observe, ‘for fishing/aquaculture communities, the gendered patterns of migration are still relatively unknown’.

Many fishers, or fishermen, are reported to regularly migrate in search of better fish catches and prices for fish (Marquette et al., Citation2002; Randall, Citation2005; Wanyonyi, Wamukota, Tuda et al., Citation2016), though over time, migration may become a way of life (Wanyonyi, Wamukota, Mesaki et al., Citation2016). There are often regular patterns of movement and regular, or repeated, routes and destinations. This suggests that receiving communities expect to receive an influx and departure of fisherfolk. There is mixed evidence in the literature on fisherfolk migration, however, on how migrants are received in fishing communities. Njock and Westlund (Citation2010) observe that experience in West Africa suggests that integration into coastal communities is not always easy and that payment of a ‘symbolic tithe’ to temporarily settle may be required. Difficulties in integration result from competition for jobs and fish and there being different languages, norms and traditions, and these difficulties may contribute to constraints in accessing services such as education and health care (Njock & Westlund, Citation2010). Wanyonyi, Wamukota, Tuda et al. (Citation2016) also found evidence of conflict and lack of integration being associated with fisher migration in Zanzibar. Despite evidence of difficulties in integration, Njock and Westlund (Citation2010) also found in West and Central Africa that new relationships are formed between men and women as a result of migration, with cohabitation and frequent change of partners, as well as polygamy being associated with migration.

As well as influencing practices and conditions in the receiving location, the migration of fisherfolk has consequences for those they leave behind. Njock and Westlund (Citation2010) found that money sent home by male fishers who have migrated is often invested in small businesses by their wives. Wanyonyi, Wamukota, Tuda et al. (Citation2016) found in their research in Zanzibar that migration was associated with increased income and savings, with benefits for the wider communities as well as households. The financial benefits associated with fisherfolk migration can therefore be experienced in the originating communities as well as in the destination communities.

Negative effects on households and communities left behind have also been recorded in relation to the migration of fishermen. These include an increased burden of work on the family left behind (Wanyonyi, Wamukota, Tuda et al., Citation2016) and disruption to family life (Bennett, Citation2005). A significant challenge affecting fishing communities associated with migration is high levels of HIV/AIDS in fishing communities (Allison & Seeley, Citation2004; Kissling et al., Citation2005; Weeratunge et al., Citation2010). High levels of HIV/AIDS prevalence are described as being associated with ‘mobility and absence from home, cash income and a masculine subculture that encourages hard-drinking and casual sexual encounters’ (Allison & Seeley, Citation2004, p. 220). Allison and Seeley (Citation2004) caution against generalising about all fishing communities and not investigating and addressing other, or related, causes, such as the lack of savings facilities at the landing sites and lack of access to alternative employment or income generating sources. High levels of HIV/AIDS prevalence have also been related to the practice of ‘fish-for-sex’, where women are reported to engage in sexual relationships with male fishers to gain and maintain access to fish (Béné & Merten, Citation2008; MacPherson et al., Citation2012).

Transactional sex has been frequently observed within fisheries and linked to migratory behaviour (Béné & Merten, Citation2008; Fiorella et al., Citation2015; Kissling et al., Citation2005). Fiorella et al. (Citation2019, p. 1809) consider several explanations for the perceived higher rate of observations of transactional sex in fisheries as: ‘(1) transactional sexual relationships may be under-reported or subject to observer bias in settings where HIV prevalence is high, (2) transactional sex may be an overstatement of ordinary relationships or (3) fishing economies may uniquely motivate transactional sex’. Considering each in turn, Fiorella et al. (Citation2019) offer caution in interpreting relationships and reported prevalence, observing that context matters and translation between languages and cultures must be carried out with care. They do, however, also observe that the ‘distinct hierarchical gender dynamic’ (2019, p. 1809) of fishing economies, where men tend to be, though not exclusively, the harvesters, and women the processors, enables this transactional relationship.

The nature of fisherfolk migration and its influence on societal change therefore has multiple gender dimensions. The very practice of migration is perceived to be gendered, with men more likely to move than women, and implications are gendered in terms of who is affected, how and how they respond. Gender has been defined as ‘the full ensemble of norms, values, customs and practices by which the biological difference between the male and female of the human species is transformed and exaggerated into a very much wider social difference’ (Kabeer, Citation1999, p. 4). This social difference generates gender relations, a form of social relations which are ‘constituted through the rules, norms and practice by which resources are allocated, tasks and responsibilities assigned, value is given and power is mobilised’ (Kabeer, Citation1999, p. 12).

Taking a social relational perspective to the analysis of gender relations is therefore critical in studying the influence of fisherfolk migration on societal change. Such a perspective recognises the constraints of social norms on men and women (Locke et al., Citation2017), particularly on women given gender inequalities associated with social norms and relations, resulting in women having less capability to act as they would wish (Lawless et al., Citation2019).

Social norms shape opportunities and constraints that men and women face, with differences in experience and implications resulting from a range of social factors, including gender, age and ethnicity. Social norms are understood to be rules of behaviour ‘such that individuals prefer to conform to it on condition that they believe that (a) most people in their reference network conform to it (empirical expectation), and (b) most people in their reference network believe they ought to conform to it (normative expectation)’ (Bicchieri, Citation2017, p. 35, original italics). Boudet et al. (Citation2013) observe that gender norms are particularly unchanging, ascribing this to such norms being widely held, frequently practised, representing the interests of those with power and because they are associated with biases linked to genders making conforming more likely.

From this review of literature, it can be concluded that fisherfolk migration is a highly gendered phenomenon, with gender norms and relations shaping who migrates, the relations between male fishers and women fish processors in hierarchical fishing economies and consequences for fishing communities.

3. Lake Victoria fisheries

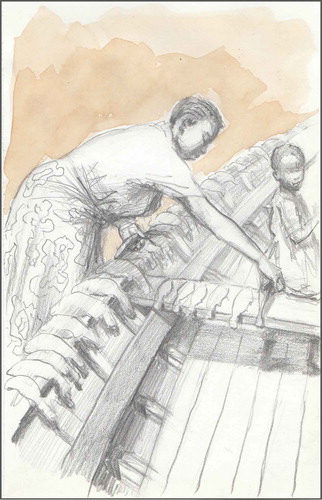

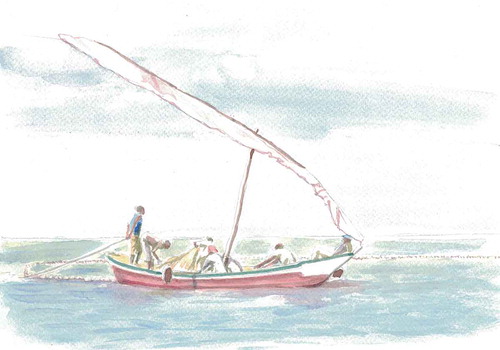

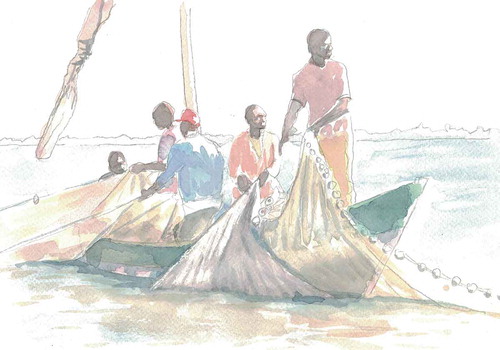

Fishing on Lake Victoria is ‘artisanal’ in that the boats are locally made and are operated by a small number of crew; however, there is increasing use of outboard engines, enabling greater reach of boats. In 2014, almost 70,000 vessels were recorded to be operating on the lake, with around 30% of these propelled by outboard engines, compared to 10% in 2000 (LVFO, Citation2015). There are a number of subsidiary occupations at the landing sites, such as boat makers, net repairers and gear sellers, that form part of the fisheries sector and communities. LVFO (Citation2015) recorded just over 200,000 fishers (boat crew and boat owners) on the lake, with around 70% being boat crew (LVFO, Citationn.d.). Under 1% of these fishers are women, demonstrating the clear male dominance of the catch sector. Almost all boat crew are male, with just a few women owning boats.

There are around 1,500 landing sites around Lake Victoria. These landing sites vary in population and degree of permanency. On the Tanzanian shore of the Lake, some boat owners set up ‘fishing camps’ independent of, or sometimes close to, villages, made up of fishers who move together, whilst other landing sites may be more akin to a village or be permanently associated with a village. Landing sites vary between very small, temporary settlements (Beuving, Citation2010) to more established, larger and permanent settlements with facilities such as bars, primary schools and health clinics.

From the late 1990s, everyone working within fisheries at the beach level was required to register with a Beach Management Unit (BMU), a community-based organisation formed under the national department of fisheries to work with the government in managing the fisheries. BMUs were formed at landing sites with at least 30 boats, with some BMUs including more than one landing site. Each BMU consists of all those registered to operate within fisheries at that beach, who meet as a BMU Assembly periodically, and an elected committee, with national regulations setting out the required composition of the committee. One of the responsibilities of BMUs is to issue letters to those fishers wishing to move to another landing site for a period of time and to receive those letters from incoming fishers. This enables fishers to be formally ‘vetted’ and welcomed at a receiving landing site and this practice therefore facilitates fisherfolk migration.

Fishers tend to go out on fishing trips on average five times a week on single-day trips, with two days off for rest (LVFO, Citation2008). Boat crew were generally paid each fishing trip as a proportion of the value of the catch. This meant that income was variable, but regular, and crew had a reputation within the fishing communities of being willing to spend, knowing that they will be out on the lake again very soon, gaining more income.

4. Experience and implications of fisherfolk migration on Lake Victoria

The experience and implications of fisherfolk migration for fishing communities are explored within the three areas identified from the literature review: gendered migration of fisherfolk; gendered relations within fishing communities; and, impacts on family life and on communities resulting from fisherfolk migration.

4.1 Gendered migration of fisherfolk

The gendered division of labour within Lake Victoria fisheries is reflected in who migrates between landing sites and for how long. Around 50% of boat crew interviewed in the 2007 study reported to move between landing sites, usually spending 3 to 4 months away from their permanent landing site (Nunan, Citation2010). Far fewer women reported to move between landing sites, with around 9% reporting to do so in a quantitative survey carried out in 2008, working on two to three beaches a year (LVFO, Citation2008). Women who do move either move with their husbands or as a trader to buy fish. In Kenya, data showed that the average of 50% of boat crew moving between landing sites was almost consistent for fishers targeting different species, with 43% of Nile perch fishers moving, 44% of those targeting Tilapia and 57% targeting dagaa (Lwenya et al., Citation2008).

Boat crew may either move with the boat owner they have been working for or may move to another site and seek employment once they get there. Having contacts or being known because they have stayed there before is helpful to gaining employment and being accepted by the receiving community. No barriers to gaining employment for migrants were cited in any of the studies based on being a migrant; opportunities were dependent on demand for crew, in turn at least in part dependent on fish catches. In the fieldwork carried out in 2015, it was widely confirmed that incoming fishers present themselves with a letter to the BMU Chair, registering their gears as well as themselves. The importance of this practice is reflected in an observation by one boat owner that ‘once migrant fishers registered their gears to BMUs and found to be legal, we interact very well with them’ (interview with Boat Owner, Tanzania, 2015). The practice was further elaborated on by a boat owner in Uganda who explained

When a new migrant comes he is asked to introduce himself, he is asked where he is coming from and show his documents to the relevant authorities. If he is a fisherman he reports to BMU, asked where he comes from, asked for the necessary documents and the method of fishing he is using. He is then allowed to fish. (Interview with Boat Owner, Uganda, 2015)

Women do not generally move from one landing site to another, largely due to domestic responsibilities and keeping children in school, but also because of other social norms. Some women were not keen on their husbands moving to another landing site as they were aware of the potential for them to become involved with other women and perhaps marrying another wife (Lwenya et al., Citation2008). Camlin et al. (Citation2013, Citation2014) report on a study investigating the mobility and migration of women fish traders and found that there are a number of patterns of mobility of women involving short stays, for example, between the landing site and village for farming and where their families stay, or between the landing site and urban centres or other fish markets. They found that migration to the landing sites, that is women moving into fisheries, often resulted from separation, divorce, death of their partner or domestic violence.

Z. Kwena et al. (Citation2020) found in their research in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda that women make circular trips between fish landing sites on Lake Victoria to buy and sell fish, and also visit families and their villages away from the lake. The size of the fishing business influenced the distance travelled and the amount of time away, with those operating on a larger scale travelling further and being away for longer than those with a medium-sized business. This corresponds with Medard et al.’s (Citation2019) findings from research on Lake Victoria in Tanzania, where women fish traders from the Democratic Republic of Congo were engaged in larger scale trade of sun-dried and salted Nile perch (known as kayabo), moving considerable distances, supported and protected by a network of businessmen and male fish traders. In contrast, local Tanzanian women fish traders dealt with smaller quantities of fish and travelled less distance.

Whilst the main driver for migration appeared to be the search for better fish catches and prices, boat crew also reported that working at other landing sites enabled them to gain experience within their occupation (Luomba, Citation2007b; Lwenya et al., Citation2008; Odongkara & Ntambi, Citation2007). This can help them secure employment, as boat owners are keen to employ skilled, experienced boat crew (Nunan et al., Citation2018).

4.2 Gendered relations within fisheries

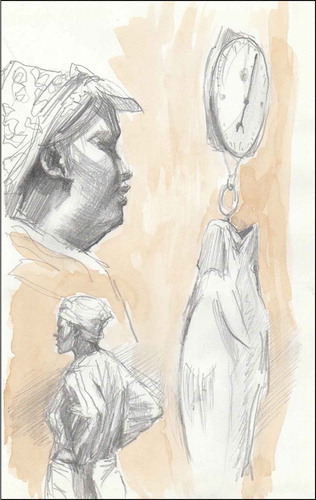

The gendered nature of fisherfolk migration reflects the gendered division of labour within the fisheries of Lake Victoria and as found in many other fisheries. The lakewide survey in 2008 included stratified samples of boat crew, boat owners, women and male fish traders. Around 90% of the 609 women in the sample were fish processors, fish traders or carried out both activities, and 5% were boat owners (LVFO, Citation2008). The final 5% were engaged in other occupations, mainly petty trading in goods other than fish. Men were also involved in fish trading, as local traders, buying fish directly from boat owners, as traders buying fish from local traders to take to markets beyond the landing site and as fish agents, buying Nile perch on behalf of fish processing plants. Other studies found that around 97% of fish agents are men (Luomba, Citation2007a; Lwenya et al., Citation2007). Women also generated income by cooking and renting out rooms at the landing sites, a particularly important service for migrant fishers (Z. Kwena et al., Citation2020). In the Dagaa fishing camps in Tanzania, many of the women who were working as cooks were either widowed or divorced (Medard, Citation2015).

Such gendered division of labour is reflected in access to fish being often dependent on the female processors/traders engaging in sexual relations with fishers. Having money to buy fish is often not sufficient, as observed by Fiorella et al. (Citation2015, p. 326) respondents in their survey in Kenya confirmed that ‘a sexual relationship with a fisherman is often necessary to be allowed to make the purchase’. In her more ethnographic study in Tanzania, Medard (Citation2015, p. 152) observed that ‘women off-loaders are expected to offer sex to men in the Dagaa fishery, but that there is no shame in it: it is just part of a woman’s life and there is no need to hide it’. The need to engage in sexual relations with fishers stems from there being competition for fish due to reduced stocks and high demand, and close relationships between mainly male fish agents and boat owners, with good quality and correct size Nile perch sold to fish agents in exchange for access to credit to buy gears and repair boats rather than local, mainly female, traders (Pearson et al., Citation2013).

Fishing on the lake is viewed as a dangerous, risky occupation, with much concern amongst fishers about the potential to drown in stormy weather (Kobusingye et al., Citation2016). Despite this view of fishing, boat crew are still willing to go out onto the lake, often without a life jacket or being able to swim (Kobusingye et al., Citation2016). This risk-taking attitude reflects masculine identity associated with fishing, reinforced by frequent interaction with fellow male boat crew, as the personal networks of boat crew have been shown to comprise mainly of fellow boat crew and some boat owners, with few women (Nunan et al., Citation2018). Such networks can be very helpful, facilitating the movement of fishers and traders. Boat crew share information on catches and prices with other crew they meet on the lake and traders share information through trading relationships (Nunan, Citation2010).

Gendered relations and norms pervade fisheries on the lake in terms of occupation and practices. Access to fish by female fish processors and traders is reported to be often dependent on transactional sexual relationships, being linked to migration of fishers away from their families and permanent landing site and consequently to high levels of HIV/AIDS (Z. Kwena et al., Citation2020; Z. A. Kwena et al., Citation2019).

4.3 Impacts on households and communities

Fisherfolk migration is associated with societal change in the fishing communities in a number of ways, particularly associated with changing and diverse social norms associated with people moving into and between fish landing sites. At some locations, social norms are relatively unchanging, associated with ongoing dominance of one ethnicity and cultural identity. Shared kinship has been associated with enabling fisher migration (Nunan, Citation2010) and facilitates shared norms. However, there are also many landing sites that have a mix of people from many ethnic groups, with greater potential to challenge social norms and practices and create new or hybrid norms and practices. Norms and practices are exchanged and influenced through the movement of fisherfolk between landing sites, as fisherfolk bring with them their beliefs and ways of doing things that may influence people at the landing site to which they have moved (Nunan et al., Citation2015).

The reported behaviour of many boat crew is cited as evidence of changing social and cultural norms. Boat crew are reported to be inclined to spend income regularly, exacerbated by a lack of facilities to save money, opportunities for high alcohol consumption, presence of commercial sex workers at many landing sites and the practice of transactional sex (Sileo et al., Citation2016). Alcohol use is said to be prevalent at many landing sites, creating health and social problems, though is an important source of livelihood for women. Reasons cited for relatively high levels of alcohol use have been given as awareness of the danger of potential drowning when fishing and fluctuating income resulting from fluctuating catches (Sileo et al., Citation2016). Regular spending of daily cash income, alcohol consumption and transactional sex are cited as evidence that fisheries communities are places where cultural norms have been left behind and new norms and practices taken up (Camlin et al., Citation2014).

Changes in social norms can present people with opportunities that they may otherwise be denied. Landing sites offer people who have experienced problems in gaining a livelihood and being settled elsewhere the chance to generate income (Pearson et al., Citation2013). The potential for daily income associated with daily fish catches and availability of cash has encouraged influx of single, divorced and widowed women to the landing sites. Such women, through their independent economic enterprises such as petty trading and cooking for migrant fishers, challenge social norms and practices by not conforming to gendered domestic roles (Z. Kwena et al., Citation2020; Pearson et al., Citation2013). In a similar vein, reported abandonment of social norms has also been attributed to high levels of consumption of locally brewed alcohol (Pearson et al., Citation2013).

Migration between fish landing sites presents both means of reducing and increasing the livelihood vulnerability of fisherfolk households and communities. Nunan (Citation2010) suggests that boat crew and women exchange sources of vulnerability and risk through migration, from vulnerability due to fluctuating fish stocks, catches and income to vulnerability due to unprotected sex with multiple partners and exposure to HIV/AIDS. For boat crew, their precarious employment with no formal contracts are linked to fish catches. If catches reduce, the number of boat trips per week may reduce and their income, which is catch dependent, will reduce. Whilst improved income then is a motivation for moving, additional costs are incurred, such as renting a room and buying food.

‘Fish-for-sex’ transactions on Lake Victoria have been strongly linked to the practice of movement of fishers between fish landing sites (Camlin et al., Citation2013, Citation2014; Fiorella et al., Citation2015; Medard, Citation2015; Z. A. Kwena et al., Citation2019; Z. Kwena et al., Citation2020) and to the prevalence of HIV, which is reported to be higher in fishing communities than elsewhere in East African countries, with implications for the health of communities and caring responsibilities. Opio et al. (Citation2013) recorded a rate of 22% amongst fishing communities on Lake Victoria in Uganda, a rate three times that of the wider population as found in the 2011 Uganda AIDS Indicators Survey. Kamali et al. (Citation2016), however, estimated that the HIV incidence rate within the fishing communities studied in Uganda was 11 times higher than in adjacent rural, non-fishing, population. Chang et al. (Citation2016) also found a similar situation in Rakai, in Uganda, where HIV in Africa was first detected, where the fishing communities had a higher prevalence of HIV/AIDS and of higher levels of risky behaviour than the trading and farming communities also studied. Evidence from research in Uganda has linked high prevalence of HIV/AIDS within in the fishing communities of Lake Victoria to unprotected sex with different partners, including with commercial sex workers, and to high levels of alcohol use (Sileo et al., Citation2016; Tumwesigye et al., Citation2012).

Transactional sex reflects and influences power relations between men and women, manifested in other aspects of social relations within the communities. Camlin et al. (Citation2013) confirmed that women who engage in fish-for-sex in Kenya on Lake Victoria were considered to have had no choice, given competition amongst traders, by their study respondents, but many women involved in this practice reflected on the independence it had brought them by providing access to fish and hence income. This suggests that the power dynamics may be complex and multifaceted, reflecting a diversity of experiences in gender relations. Initiatives have been taken, however, to combat the practice through women owning boats, such as the ‘No fish for sex program’ in Nduru Beach, Kenya, though the impact of the programme was challenged in 2020 by floods in the region which destroyed the boats (NPR, Citation2020). This example suggests a desire by women to have more agency and greater direct benefit from the fisheries, as well as avoid transactional sex.

Fishing communities are also impacted by the migration of fisherfolk by the perceived temporary nature of settlements and fluctuating population levels. The migration studies of 2007 reported significant variations in population sizes at the sampled landing sites at different points in a year (Luomba, Citation2007b; Lwenya et al., Citation2008; Odongkara & Ntambi, Citation2007), making planning and service delivery challenging. It was further reported by Nunan (Citation2010) that the fluctuation in population at landing sites was used as a reason by governments to do little to extend services to landing sites. Examples of the poor service provision at landing sites are shown in the lack of access to potable drinking water, with around 14% of landing sites having potable water in 2014, not many more than the 12% in 2008, and 39% of landing sites were accessed via an all-weather road, compared to 32% in 2008 (LVFO, Citation2015). The number of landing sites with a health clinic improved however, from 36% in 2008 to 46% in 2014 (LVFO, Citation2015), though these are likely to be privately owned rather than provided by government.

Although fishing communities are affected by changing social norms and fluctuating population, there appear to be good relations between permanent and migratory fisherfolk. Research carried out at 18 landing sites around the lake in 2015 asked respondents about relations between permanent residents at the landing sites and migrants. Respondents were overwhelmingly positive about migrant fisherfolk, stating, for example, that ‘there are no differences with people from elsewhere and people of this area. We just operate as team’ (interview with Boat Crew, Kenya, 2015) and ‘we interact very well; we are the one telling the migrant fishers where to fish’ (interview with Boat Crew, Tanzania, 2015). This acceptance was at least in part explained by the observation that these respondents too move between beaches, ‘this work we have to work together and not have boundaries because even us we sometimes land at other beaches’ (interview with Boat Crew, Kenya, 2015) and ‘even some of our colleagues go to places from where these in-migrants come from so we can’t mistreat them’ (interview with Boat Crew, Uganda, 2015). However, one boat owner observed that migrant fishers tend to keep to themselves, explaining that ‘those who migrate to this landing beach tend to stay together, do their own things together, they take care of themselves. This is what fishers do when they go to distant places away from home’ (interview with Boat Owner, Tanzania, 2015). Such quotes suggest then that whilst there is acceptance of migrating fisherfolk, there is not necessarily considerable integration.

For boat crew and boat owners who preferred not to move between landing sites, they saw benefits from staying at the landing site as being able to combine their income generation from fishing with other activities, particularly farming, and were able to oversee any investment they may have such as house construction and farming, as well as support their families. Access to credit was felt to be harder when moving to a new landing site, as credit is often provided by a fish agent or trader to boat owners and by boat owners to crew. Such provision of credit facilitates loyalty in trading and labour relations and may be harder to maintain when fishers move to another landing site, even more so if crew move to employment by another boat owner. Mobile phone use is high in fisheries, with the majority of landing sites having mobile phone coverage (LVFO, Citation2015). As well as using mobile phones to discuss where fish catches and prices are higher with their contacts, migrant fishers use their phones to keep in touch with families, meaning that they can stay away for longer at times (LVFO, Citation2008).

5. Conclusion

This investigation into the gendered experience of fisherfolk migration and its influence on societal change in the fishing communities of Lake Victoria has demonstrated that such influence is manifested in challenges to social norms and relations, the implications of changing social norms and in perceptions of changing population at landing sites.

There was evidence of both continuing and dynamic social norms associated with fisherfolk migration. Stable social norms and practices enable those resident at fish landing sites to welcome and work with migrant fisherfolk, recognising the income they bring through fish catches. However, migration has also challenged social norms and practices. This is manifested in several ways. Firstly, incoming male fishers increase the generation of daily cash income, attracting women involved in fish trade, cooking for fishers, petty trading and commercial sex. Women moving to the fish landing sites for economic enterprises were frequently described as being single, widowed and divorced, attracted by the opportunity to generate income independently and quickly. The presence and economic behaviour of women migrating to the landing sites challenges gender norms and relations. Secondly, the increased generation of cash on a daily basis was associated with increased consumption of alcohol and commercial and transactional sex, challenging social norms on acceptable behaviour. Finally, migration itself challenges social norms through the formation of new relationships between men and women to facilitate economic relations, which at times involved the formation of new relationships or transactional sex.

The conditions within fishing communities of high levels of migration, daily cash income and people from different cultural backgrounds, potentially away from close family, enable people to challenge and even reject social norms of behaviour. Challenging and rejecting social norms suggests that there is shared belief that others in a reference network (Bicchieri, Citation2017) will also not conform. However, there is no strong evidence that gender norms had significantly altered, despite the economic independence of some women, supporting Boudet et al.’s (Citation2013) findings that gender norms are particularly unchanging, attributed to the power that men hold and want to maintain and the ingrained biases associated with expected behaviour of men and women.

The influence of gender norms and the ‘distinct hierarchical gender dynamic’ of fisheries (Fiorella et al., Citation2019, p. 1809) is manifest in the reported prevalence and ongoing practice of transactional sex, or ‘fish-for-sex’, reflecting how gender norms place constraints on both men and women (Locke et al., Citation2017) and gender inequalities can limit the agency of women (Lawless et al., Citation2019). Such transactional sex was consistently linked to the migration of male fishers, as well as changing social norms linked to cash income and alcohol consumption, and to the reported high rates of HIV/AIDS within fishing communities, relative to other communities. This suggests that societal change associated with fisherfolk migration could carry a high cost.

Such a high cost associated with relatively high levels of HIV/AIDS is exacerbated by the poor provision of public services to fish landing sites. Such limited provision of public services, including of health care, was also attributed to migration, with changing population size and composition cited as a reason for not providing landing sites with adequate services.

Fisherfolk migration is evidently a strongly gendered dynamic and has implications for social norms and practices that in turn have implications for fishing communities. These implications can be experienced positively in terms of increased cash available and livelihood opportunities, but also as more challenging in terms of expectations for transactional sex and associated implications for health and wellbeing.

The findings demonstrate how ingrained gender norms are within fisheries but that other social norms concerning behaviour have been challenged. They suggest that interventions that aim to support the health and wellbeing of fisherfolk must appreciate the strength of gender norms and the dynamism of social norms resulting from fisherfolk movement and regular cash income.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fiona Nunan

Fiona Nunan is Professor of Environment and Development, at the International Development Department, University of Birmingham, UK. Her research interests lie in the governance and livelihoods associated with renewable natural resources in low-income countries, particularly inland fisheries and coastal ecosystems. She worked on two fisheries and lake management projects in East Africa between 2003 and 2008, supporting the implementation of fisheries co-management and undertaking policy advocacy and socio-economic research. Returning to academia in 2008, Professor Nunan has undertaken research in Kenya, Zanzibar and Sri Lanka into governance arrangements in coastal ecosystems, and into social networks and fisheries co-management on Lake Victoria, East Africa. Her current research examines how the governance of renewable natural resources can be supported to become more sustainable and effective over time. In addition to a substantial body of peer-reviewed journal articles, Professor Nunan has published three books: Understanding Poverty and the Environment: Analytical frameworks and approaches (2015), Making Climate Compatible Development Happen (2017) and Governing Renewable Natural Resources: theories and frameworks (2020).

References

- Abila, R. O., & Jansen, E. G. (1997). From Local to Global Markets: The Fish Processing and Exporting Industry on the Kenyan part of Lake Victoria – Its Structure, Strategies and Socio-Economic Impacts (University of Oslo Working Paper 1997.8). University of Oslo.

- Allison, E. H., & Seeley, J. A. (2004). HIV and AIDS among fisherfolk: A threat to ‘responsible fisheries’? Fish and Fisheries, 5(3), 215–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2679.2004.00153.x

- Béné, C., & Merten, S. (2008). Women and fish-for-sex: Transactional sex, HIV/AIDS and gender in African fisheries. World Development, 36(5), 875–899. https://doi.org/org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.05.010

- Bennett, E. (2005). Gender, fisheries and development. Marine Policy, 29(5), 451–459. https://doi.org/org/10.1016/j.marpol.2004.07.003

- Beuving, J. J. (2010). Playing pool along the shores of Lake Victoria: Fishermen, careers and capital accumulation in the Ugandan Nile perch business. Africa, 80(2), 224–248. https://doi.org/org/10.3366/afr.2010.0203

- Bicchieri, C. (2017). Norms in the wild: How to diagnose, measure, and change social norms. Oxford University Press.

- Boudet, A., Petesch, P., & Turk, C., with Thumala, A. (2013). On norms and agency: Conversations about gender equality with women and men in 20 countries. In Directions in Development. World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-9862-3

- Camlin, C. S., Kwena, Z. A., & Dworkin, S. L. (2013). Jaboya vs. Jakambi: Status, Negotiation, and HIV Risks Among Female Migrants in the “Sex for Fish” Economy in Nyanza Province, Kenya. AIDS Education and Prevention, 25(3), 216–231. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2013.25.3.216

- Camlin, C. S., Kwena, Z. A., Dworkin, S. L., Cohen, C. R., & Bukusi, E. A. (2014). “She mixes her business”: HIV transmission and acquisition risks among female migrants in western Kenya. Social Science and Medicine, 102, 146–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.004

- Chang, L. W., Grabowski, M. K., Ssekubugu, R., Nalugoda, F., Kigozi, G., Nantume, B., & Wawer, M. J. (2016). Heterogeneity of the HIV epidemic in agrarian, trading, and fishing communities in Rakai, Uganda: An observational epidemiological study. Lancet HIV, 3(8), e388–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(16)30034-0

- Duffy-Tumasz, A. (2012). Migrant fishers in West Africa: Roving bandits? African Geographical Review, 31(1), 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2012.680860

- Fiorella, K. J., Camlin, C. S., Salmen, C. R., Omondi, R., Hickey, M. D., Omollo, D. O., Milner, E. M., Bukusi, E. A., Fernald, L. C. H., & Brashares, J. S. (2015). Transactional fish-for-sex relationships amid declining fish access in Kenya. World Development, 74, 323–332. https://doi.org/org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.05.015

- Fiorella, K. J., Desai, P., Miller, J. D., Okeyo, N. O., & Young, S. L. (2019). A review of transactional sex for natural resources: Under-researched, overstated, or unique to fishing economies? Global Public Health, 14(12), 1803–1814. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2019.1625941

- Kabeer, N. (1999). From Feminist Insights to an Analytical Framework: An Institutional Perspective on Gender Inequality. In N. Kabeer & R. Subrahmanian (Eds.), Institutions, Relations and Outcomes: Framework and Case Studies for Gender-Aware Planning (pp. 3–48). Zed Books.

- Kamali, A., Nsubuga, R. N., Ruzagira, E., Bahemuka, U., Asiki, G., Price, M. A., … Fast, P. (2016). Heterogeneity of HIV incidence: A comparative analysis between fishing communities and in a neighbouring rural general population, Uganda, and implications for HIV control. Sex Transmitted Infections, 92(6), 447–454. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2015-052179

- Kissling, E., Allison, E. H., Seeley, J. A., Russell, S., Bachmann, M., Musgrave, S. D., & Heck, S. (2005). Fisherfolk are among groups most at risk of HIV: Cross-country analysis of prevalence and numbers infected. AIDS, 19(17), 1939–1946. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000191925.54679.94

- Kobusingye, O., Tumwesigye, N. M., Magoola, J., Atuyambe, L., & Olange, O. (2016). Drowning among the lakeside fishing communities in Uganda: Results of a community survey. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion, 24(3), 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457300.2016.1200629

- Kwena, Z., Nakamanya, S., Nanyonjo, G., Okello, E., Fast, P., Ssetaala, A., Oketch, B., Price, M., Kapiga, S., Bukusi, E., & Seeley, J., & the LVCHR. (2020). Understanding mobility and sexual risk behaviour among women in fishing communities of Lake Victoria in East Africa: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 944. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09085-7

- Kwena, Z. A., Njuguna, S. W., Ssetala, A., Seeley, J., Nielsen, L., De Bont, J., Bukusi, E. A., & Lake Victoria Consortium for Health Research (LVCHR) Team (2019). HIV prevalence, spatial distribution and risk factors for HIV infection in the Kenyan fishing communities of Lake Victoria. PLoS ONE, 29(5), e0214360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2004.07.003

- Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation, (LVFO). (n.d.). People in Lake Victoria Fisheries: Livelihoods, Empowerment and Participation (Information Sheet 1). Implementation of a Fisheries Management Plan, LVFO.

- Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation. (2008). Regional Synthesis of the 2008 socio-economic monitoring survey of the fishing communities of Lake Victoria.

- Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation. (2015). Regional Status Report on Lake Victoria Bi-ennial Frame Surveys between 2000 and 2014. Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda.

- Lawless, S., Cohen, P., McDougall, C., Orirana, G., Siota, F., & Doyle, K. (2019). Gender norms and relations: Implications for agency in coastal livelihoods. Maritime Studies, 18(3), 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-019-00147-0

- Locke, C., Muljono, P., McDougall, C., & Morgan, M. (2017). Innovation and gendered negotiations: Insights from six small-scale fishing communities. Fish and Fisheries, 18(5), 943–957. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12216

- Luomba, J. (2007a). A report on fish agents survey in Lake Victoria, Tanzania. Tanzania Fisheries Research Institute.

- Luomba, J. (2007b). A report of the mobile fishers survey carried out in Lake Victoria, Tanzania. Tanzania Fisheries Research Institute.

- Lwenya, C., Yongo, E., & Abila, R. (2007). A report on fish agents survey: Kenya. Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute.

- Lwenya, C., Yongo, E., & Abila, R. (2008). Mobile Fishers: The scale and impact of movement of fishers on fisheries management in Lake Victoria. Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute.

- MacPherson, E., Sadalaki, J., Njoloma, M., Nyongopa, V., Nkhwazi, L., Mwapasa, V., Lalloo, D. G., Desmond, N., Seeley, J., & Theobald, S. (2012). Transactional sex and HIV: Understanding the gendered structural drivers of HIV in fishing communities in southern Malawi. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 15(Suppl 1), 17364. http://dx.doi.org/10.7448/IAS.15.3.17364

- Marquette, C. M., Koranteng, K. A., Overå, R., & Aryeetey, E. B. D.. (2002). Small-scale Fisheries, Population Dynamics, and Resource Use in Africa: The Case of Moree, Ghana. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 31(4), 324–336. https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447-31.4.324

- Medard, M. (2015). A social analysis of contested fishing practices in Lake Victoria, Tanzania. PhD Thesis. Wageningen University.

- Medard, M., van Dijk, H., & Hebinck, P. (2019). Competing for kayabo: Gendered struggles for fish and livelihood on the shore of Lake Victoria. Maritime Studies, 18(3), 321–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-019-00146-1

- Njock, J.-C., & Westlund, L. (2010). Migration, resource management and global change: Experiences from fishing communities in West and Central Africa. Marine Policy, 34(4), 752–760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2010.01.020

- NPR (2020) Life Was Improving For ‘No Sex For Fish.’ Then Came The Flood. 1 November 2020. Washington, D.C. Available: https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/11/01/928661350/life-was-improving-for-no-sex-for-fish-then-came-the-flood?utm_campaign=storyshare&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_medium=social&t=1604319004581 Accessed 2 November 2020.

- Nunan, F. (2010). Mobility and fisherfolk livelihoods on Lake Victoria: Implications for vulnerability and risk. Geoforum, 41(5), 776–785. https://doi.org/org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.04.009

- Nunan, F., & Cepić, D. (2020). Women and fisheries co-management: Limits to participation on Lake Victoria. Fisheries Research, 224, 105454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2019.105454

- Nunan, F., Cepić, D., Mbilingi, B., Odongkara, K., Yongo, E., Owili, M., Salehe, M., Mlahagwa, E., & Onyango, P.. (2018). Community cohesion: Social and economic ties in the personal networks of fisherfolk. Society and Natural Resources, 31(3), 306–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2017.1383547

- Nunan, F., Hara, M., & Onyango, P. (2015). Institutions and co-management in East African inland and Malawi fisheries: A critical perspective. World Development, 70, 203–214. https://doi.org/org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.01.009

- Nunan, F., Luomba, J., Lwenya, C. A., Yongo, E., Odongkara, K., & Ntambi, B.. (2012). Finding space for participation: Fisherfolk mobility and co-management of Lake Victoria fisheries. Environmental Management, 50(2), 204–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-012-9881-y

- Odongkara, K., & Ntambi, B. (2007). Migration of Fishermen and its impacts on fisheries management on Lake Victoria, Uganda. Implementation of a Fisheries Management Plan, National Fisheries Resources Research Institute.

- Opio, A., Muyonga, M., Mulumba, N., & Cameron, D. W.. (2013). HIV Infection in Fishing Communities of Lake Victoria Basin of Uganda – A Cross-Sectional Sero-Behavioral Survey. PLoS ONE, 8(8), e70770. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0070770

- Pearson, G., Barratt, C., Seeley, J., Ssetaala, A., Nabbagala, G., & Asiki, G. (2013). Making a livelihood at the fish-landing site: Exploring the pursuit of economic independence amongst Ugandan women. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 7(4), 751–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2013.841026

- Randall, S. (2005). Review of Literature on Fishing Migrations in West Africa – From a Demographic Perspective. Sustainable Fisheries Livelihoods Programme. FAO/DFID.

- Sileo, K. M., Kintu, M., Chanes-Mora, P., & Kiene, S. M. (2016). “Such Behaviors Are Not in My Home Village, I Got Them Here”: A Qualitative Study of the Influence of Contextual Factors on Alcohol and HIV Risk Behaviors in a Fishing Community on Lake Victoria, Uganda. AIDS Behavior, 20(3), 537–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1077-z

- Tumwesigye, N. M., Atuyambe, L., Wanyenze, R. K., Kibira, S. P. S., Li, Q., Wabwire-Mangen, F., & Wagner, G. (2012). Alcohol consumption and risky sexual behaviour in the fishing communities: Evidence from two fish landing sites on Lake Victoria in Uganda. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 1069. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-1069

- Wanyonyi, I. N., Wamukota, A., Mesaki, S., Guissamulo, A. T., & Ochiewo, J. (2016). Artisanal fisher migration patterns in coastal East Africa. Ocean & Coastal Management, 119, 93–108. https://doi.org/org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.09.006

- Wanyonyi, I. N., Wamukota, A., Tuda, P., Mwakha, V. A., & Nguti, L. M. (2016). Migrant fishers of Pemba: Drivers, impacts and mediating factors. Marine Policy, 71, 242–255. https://doi.org/org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.06.009

- Weeratunge, N., Snyder, K. A., & Sze, C. P. (2010). Gleaner, fisher, trader, processor: Understanding gendered employment in fisheries and aquaculture. Fish and Fisheries, 11(4), 405–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2010.00368.x