ABSTRACT

Vezo migrant fishers have played a key role in shaping the seascape and resource use practices in the Southwest of Madagascar. As a population relying mainly on fishing for its livelihood, Vezo people have struggled to maintain their livelihood in the face of resource depletion. They migrate seasonally or long term from their home region on the southwest coast to marine frontiers further north such as the Barren Isles, a remote archipelago in the west of Madagascar. Exploiting sea cucumber and sharks for the global market involves economic and ritual practices that they have maintained in their journeys and constitute their identities as migrant fishers. Within a context of increasing commercialization and depletion of small-scale fisheries, various conservation initiatives have taken place within the migration route of the Vezo including the establishment of Madagascar’s largest marine protected area in the Barren Isles. This article argues that migrant fishers have managed to gain, maintain and control access to marine resources, both by performing ancestral rituals by which newcomers attach themselves to ecological niches, and also by mobilizing an environmentalist identity narrative promoted by the Malagasy government and international NGOs. In this way, Vezo migrant fishers have become key actors in the management of marine resources while maintaining their ancestral practices. This is an important argument discussing the role of local identity narratives in the political economy of global resource appropriation and shows how migrant fishers fit in the contemporary seascapes.

1. Introduction

Small-scale fishing in Madagascar is an important source of livelihood and protein for an underestimated number of more than 100,000 fishers (Ministère des Ressources Halieutiques et de la Pêche (MRHP), Citation2013). While fishing takes place along most of the country’s large coastline, the west coast is where coastal fisheries are the most productive (Harding, Citation2018). Vezo and Sara fishing people (the latter being an ethnic subgroup of the former) migrate from the southwest to the west coast over a distance of 300–500 km (Cripps & Gardner, Citation2016; Muttenzer, Citation2015). As in other African countries, migrant fishers in west Madagascar have been at the forefront of witnessing and enduring the consequences of changing oceans including climate change and especially the depletion of marine resources (Failler & Binet, Citation2010; Failler et al., Citation2020). Changes have also included the increasing enclosure of their marine seascapes either through ocean-based activities like oil exploration and aquaculture or through conservation initiatives that have led to restrictions to fishing activities or on access to fishing areas (Bennett et al., Citation2015). Amidst these challenges, migrant fishers have sustained their livelihoods by adapting fishing techniques and mobility patterns to new market opportunities.

In this article, we will explore the way migrant Vezo fishers of southwest Madagascar have gained and maintained access to the marine frontier of the Barren Isles, a remote archipelago in the west part of Madagascar. The Barren Isles, considered as productive fishing grounds due to their remoteness, have also attracted conservation interests for more than 10 years. The site recently received the status of marine protected area. While migration towards the Menabe and Maintirano region has taken place since around the 1920s, the Barren Isles only became a regular migration destination for the Vezo since the early 1990s for targeting sharks and sea cucumbers (Cripps, Citation2009; Iida, Citation2005). We argue that by mobilizing different identity narratives, Vezo migrant fishers have been able to maintain their access to the Barren Isles marine resources in the face of conservation interests and despite the creation of Madagascar’s largest marine protected area on their fishing grounds.

The case of the Vezo is an interesting one as they rely almost entirely on the ocean to provide their livelihoods and seasonal migration is a key part of this undertaking. While in exceptional cases some Vezo in some areas may forage tubers, plant watermelon as well as raising poultry (as any Malagasy rural household may), their livelihood depends decisively on fishing both for self-consumption and for market sales which are the source of cash to buy non-marine foodstuffs. As ‘semi-nomadic seafaring people’ of south-west Madagascar originally between Toliara and Morombe (Koechlin, Citation1975; Marikandia, Citation2001), they didn’t turn to fishing only after having migrated to marine frontiers, but extended the geographical scope of an already existing seasonal mobility pattern among reef fishers. Through migration, the Vezo territory has been extended to the Androy region further south and the Melaky region in the North (Veriza et al., Citation2018). While some family or descent group narratives mention origins from various other ethnic groups in the South, another common narrative mentions only Vezo ancestry as demonstrated by rituals involving a mermaid and taboos on mutton (Marikandia, Citation2001; Cripps & Gardner, Citation2016). One such group is the Sara whose ancestral land is the village of Anakao south of Toliara (Pascal, Citation2008).Footnote1

It has long been noted that rural Malagasy move around the country freely and settle on available land regardless of ethnic origin (Deschamps, Citation1959). The question is how they can do this without changing the ethnic map. Given that people aren’t obliged but are generally expected to marry into some other family from the same territorial group and thus maintain the ethnic grid unchanged (Bloch, Citation1971; Muttenzer, Citation2020), how can they also be free to migrate and settle far away from their ancestral land? The answer is that they can do so easily because ethnic membership does not depend on where people actually live but rather on the location of their family tombs.Footnote2 So rural people in Madagascar can live in a place they choose for a livelihood but when they die the corpse must be brought back to the ethnic territory and buried in the family tomb. The exception is when migrants decide to build new family tombs in the settlement area. What happens then is that the descent group changes its ethnicity by changing the family tomb location from one territorial group to a different one, and in this way the ethnic map is preserved unchanged (see Bloch, Citation1971). In short, rural migrants avoid changing the family tomb locations in order to avoid having to change the ethnic grid. But when they ultimately do change the tomb location, they thereby also change the ethnicity of the family contained in that tomb, and as a result the ethnic map will not change.

Identity narratives are entertained by descent groups and some of these narratives are shared by several descent groups belonging to the same ethnic territory while excluding other descent groups associated with a different territory. For example, the group narrative may stipulate that if an individual is Vezo (because of either parent’s family tomb location) then that individual should learn how to fish and marry someone who knows how to fish because knowing how to fish is the standard for what makes a Vezo an excellent person (ethnic group member). So it is not quite accurate (even for the Vezo themselves) to say that Vezo identity can be acquired merely by adopting a lifestyle of earning a living from the sea (Astuti, Citation1995; Grenier, Citation2013). If knowing how to fish is ‘what makes Vezo Vezo’ it is rather because there is an identity narrative shared by all individuals whose family tombs are located in Vezo territory and which says that if one is included in that category then she should learn how to fish and stick to fishing as the preferred mode of subsistence. It is likely that this ethnic identity narrative, or what one of us called the ‘fisher ethos’ (Muttenzer, Citation2015, Citation2020), favors the emergence a new kind of local personage, the ‘environmental subject’ (Agrawal, Citation2005) or ‘ocean defender’ (Gardner, Citation2016) who views himself as a steward of the environment and persuades other community members to do so as well.

In reproducing the Vezo identity narrative, rituals concerned with fertility of the ocean and human well-being also play an important role. Specific rites are enacted before, during, and after migration to obtain blessing from a spirit medium and operate a magical charm that ensures the prosperity of the work group. In the Barren Isles migrant fishers publicly acknowledge their relationship to places by performing taboos, offerings and sacrifices at one or several specific sites on each of the islands. Sacred trees are found in areas which are of strategic economic interest to both migrant fishers and conservationists. Sea spirits who are said to own these places reveal themselves to humans through their perceived presence in the landscape, stones, trees, human hosts, and physical appearances of mermaids. People respond to these revelatory signs with appropriate ritual performances. For example, a sacrifice must be performed to cleanse a sacred place from ritual defilement caused by a taboo breach.

Unlike marine protected areas, the performance of taboos and sacrifices at sacred sites is not a rights-based mechanism for securing resource access. Instead of rights the indexical messages communicated by these rituals identify the spirit owners of the land and the order of human occupants in ways that support the latter’s ‘ability to benefit from resources’, which as we shall see is also how Ribot and Peluso (Citation2003) propose to theorize resource access, as against attempts at enclosure of the unenclosed fishery commons. The remainder of this article is organized as follows. We will first present the materials and methods for investigating the ‘ability to benefit’ including the theoretical framework to analyze access regimes and the statistic and ethnographic methods used. This section will then be followed by the presentation of results including the demographic aspects of migration to the Barren Isles, economic benefits generated, and the role of ritually enacted identity narratives in securing access to these benefits. The discussion section analyses how the Vezo sustain access to resources in a seascape where the impact of global markets and conservation enclosures strongly constrain their options. We conclude that migrant fishers in west Madagascar have been able to gain and control access to marine frontiers, not only by performing ancestral rituals that help newcomers construct ecological niches by exploiting natural resources such as sharks and sea cucumbers valued on a global market and located in remote areas of the west coast of Madagascar (Grenier, Citation2013), but also by virtue of an environmentalist identity narrative that constitutes fishing communities as stewards of the environment and praises them as ocean defenders.

2. Materials and methods

In this article we propose to apply Ribot and Peluso’s theory of access to a situation where environmental relations are regulated through a ritual system. Ribot and Peluso (Citation2003, p. 153) define access as ‘the ability to benefit from things – including material objects, persons, institutions, and symbols.’ Here we discuss access to marine resources beyond property rights. Our definition of access includes the ability to have physical access (Schlager & Ostrom, Citation1992) and rights to use the resources (Sikor et al., Citation2017), and the ability to benefit from these resources (Ribot & Peluso, Citation2003). We include in marine resources various marine species and their ecosystems. As highlighted in Andriamahefazafy (Citation2020, p. 140), bringing the focus of access to the question of ability to benefit from resources allows us to highlight ‘social relationships between people’ and the situated power relations that are generated in resource access. The framework of Ribot and Peluso (Citation2003) proposes three stages of analysis. The first is to present the flow of benefits that the resources can generate. The second is to analyze the different rights-based and structural mechanisms mobilized to gain, control and maintain access to the resources. The third is to highlight the political and power relations between actors involved while using these mechanisms.

Furthermore, regarding the two categories of access mechanisms described by Ribot and Peluso, the first category is rights-based access mechanisms. The latter originate from existing laws, local customs or conventions and can include property rights as well as illegal means such as using coercion or stealth (Andriamahefazafy, Citation2020). In our case, the concept of common property, as a rights-based mechanism, is at the center of our investigation. Common property can be defined as a property regime in which the members of a demarked group, considered as owners, are co-equal in their rights to use the resource and have the legal right to exclude non-members of that group from using the resource (Ciriacy-Wantrup & Bishop, Citation1975; Ostrom & Hess, Citation2007). For Vezo fishers in particular, the sea is perceived as belonging to all and where access could not be restricted. The Vezo have held to this conception of property of the sea despite the development of legislation that contradicts it.

The second category is constituted by structural and relational mechanisms which derive from the specific political-economic and cultural context of resource access. They present eight types of structural mechanisms: technology, capital, market, labor, knowledge, authority, social identity and other social relations ().

Table 1. Categories of rights-based, structural and relational mechanisms to access resources from Ribot and Peluso’s framework (Ribot & Peluso, Citation2003), and migrant fishing (this article)

Following this framework of Ribot and Peluso, we first identified two flows of benefits that migrant fishers can gain in the western seascape of Madagascar: the fisheries resources (fish, sea cucumbers and sharks) for their livelihoods and the Barren Isles ecosystems (the islands and the sea) for their shelters and livelihoods. Then, we will discuss how these benefits have been gained and maintained through identity narratives as a key access mechanism. From the data and observations gathered, two narratives have emerged: one of ritual performers and one of environmental defenders. We will argue that these different identity narratives underlie the concept of unenclosed fishery commons and the concept of marine enclosures (protected areas) which have helped the Vezo maintain and control access over the resources.

Within the ritual performers’ narrative, we will highlight how the Vezo have used a ritually established concept of the commons (common property), situated knowledge and rituals to gain and maintain access to the resources.Footnote3 Within the environmental defenders’ narrative, we will look at how the Vezo have engaged with conservation measures and the requirement of the Barren Isles marine protected area (MPA).Footnote4 Finally, we will highlight the various political relations involved in the deployment of these two narratives, mainly political relations between migrant and local fishers, and between fishers (taken as a group targeted by the MPA) and the state and NGOs (taken as an entity that promotes MPAs). We will show that the Vezo have developed situated power relations with various actors through these narratives which allow them to maintain their migrating livelihoods and also have control over the resources. These power relations are not fixed or permanent, they evolve and are reshaped by various drivers. These include the changing ecologies of the marine seascape, interventions of conservation NGOs, and external market pressure over the resources. The use of the theory of access in analyzing Vezo migration therefore allows us to explore through one framework questions of property and access over marine resources but also agency, structures and power relations in the management of a seascape.

The first author learned about Vezo migrant fishers in February 2007 when he visited the group of islands off the west coast of Madagascar for a multidisciplinary research project headed by the Geneva Museum of Natural History that was looking into the ecology of marine turtles. The Barren Isles host important nesting sites for sea turtles. Although the first author went there initially to do a social assessment of planned conservation measures, he became interested in the Vezo as he realized there were many campsites of migrant fishers from the southwest coast and hardly any turtles on these islands. While working on the islands fishers also used to net sea turtles and dig out freshly laid turtle eggs. February is a time of the year when the seasonal migrants are supposed to be home in the ancestral village. Those encountered were people who decided to stay over until the next season, roughly a fifth of the population camping and working there July to November, or mid-December.

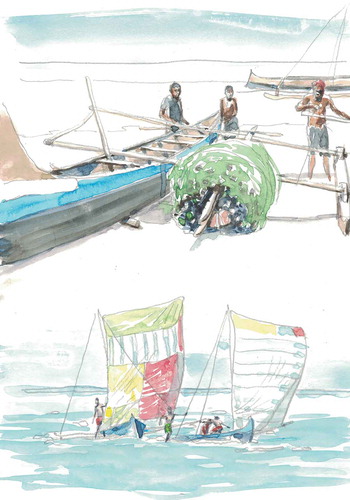

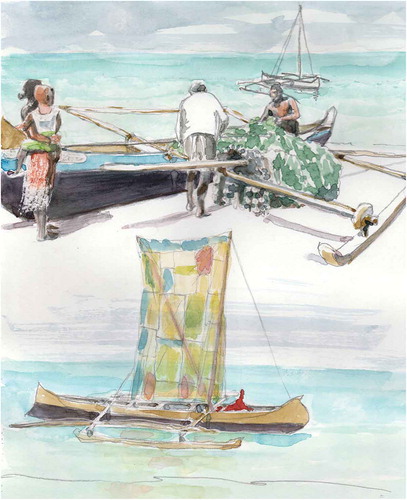

In 2012 a more systematic ethnographic study of migrant fishers in the area was carried out. The total population comprised 300 and 400 sea-going outrigger canoes distributed over 10 islands used as campsites. A sea-going canoe (laka be) carries on average six to seven individuals. The survey included a representative sample of 35 randomly chosen migrant work groups (consisting of at least one and at most two sea-going canoes). The ethnographic questionnaire covered commodity chains, expected gains, skills and gear, the organization of work-groups, access to resources and fishing gear, fishing magic, acknowledged reasons for and alternatives to migration, consumption patterns, marriage strategies, and migrants’ perceptions of marine resource degradation in both the origin region and in the frontier areas.

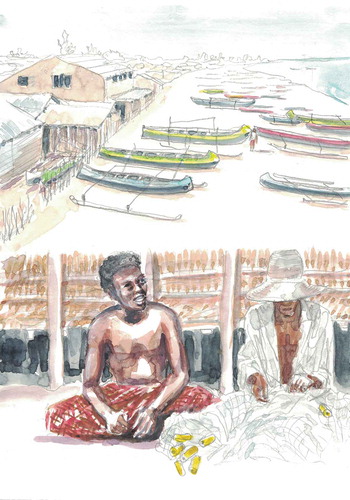

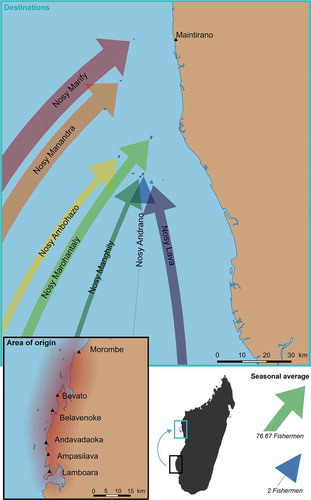

The second author has been involved in the very early stage of the setting up of the marine protected area between 2011 and 2014 when the conservation value of the Barren Isles was promoted nationally and internationally. Reports and promotion documents produced at that time were gathered to present the history of the MPA. Furthermore, information was gathered from key publications about the migration of the Vezo especially in the Barren Isles in the past 10 years. The different publications were used to extract information regarding the different mechanisms of access to the Barren Isles resources. Migration of the Vezo has been widely investigated and covered various topics from identity making (Iida, Citation2005; Marikandia, Citation2001), integration to the global market of marine resources (Grenier, Citation2013), the evolution of the migration over the years (Veriza, Citation2019), the role of migrant fishers in the conservation realm (Cripps & Gardner, Citation2016) and detailed ecological and ethnographic accounts of migrations and Vezo livelihoods (Cripps, Citation2009; Muttenzer, Citation2020). The Maintirano region is one of several marine resource frontiers of West Madagascar used by mobile fishing people from ancestral villages located 300–500 km further south on the west coast. Other popular fishing sites along the way from the southwest coast to Maintirano are found near Morondava, Ambakivao, Beanjavily, and Tambohorano. The Barren Isles are constituted of 10 islands, three of which are uninhabited (Nosy Mavony, Nosy Ampasy and Nosy Dondosy) and one has very low frequentation of fishers (Nosy Andrano). The rest (six islands) all host seasonal migrations of Vezo fishers (). Most islands are vegetated by grass and trees while some are just sub-tidal sand cays. The Barren Isles also host healthy coral reefs, mangrove forests and marine species with conservation interests such as sharks, marine turtles or sea birds.

Table 2. Individual islands of the archipelago most frequented by migrant fishers. (Sources: Cripps, Citation2010; Muttenzer, Citation2020)

As can be seen from , the places the migrants attach themselves to by performing rituals of place are of interest to them as means to access valuable resources such as shark and sea cucumber. The migrants know how to fish and how to ask the place spirits for permission. The isolation of the Barren Isles from the mainland makes them a remote site that local fishers from Maintirano rarely used to visit and there are no access rules other than ritually asking the spirits for permission. For Vezo migrants, permission from local fishers is therefore not required given that permission from spirits is sufficient to access fishing grounds. The migrants already possess the knowledge and skills needed to exploit the most valuable species on the Barren Isles in order to construct an ecological niche (Douglass & Rasolondrainy, Citation2021). The undomesticated nature of the Barren Isles makes it an open frontier or unenclosed commons. This is consistent with how territoriality works in rural Madagascar, where the boundary of unenclosed commons is defined by membership in user groups, and membership in user groups defined by ritual (Muttenzer, Citation2010). The existing taboos, offerings and sacrifices performed at sacred sites took on a new function and significance when the global fishery and conservation-related interests emerged.

3. Results

3.1 Vezo migrations and fishing practices

Vezo fishers migrate along the west coast of Madagascar. Originating from the Fiheregna coast in the southwest (between Toliara and Morombe), they migrate northwards to the Menabe (Morondava) and Melaky (Maintirano) regions (). Vezo from the southwest coast began to move to more distant fishing grounds north of the permanent ancestral settlements around 1990, when sharks became scarcer on the southwest coast (Iida, Citation2005). Pioneering unusually distant marine frontiers is an innovation whereby the existing practice of seasonally mobile foraging (tindroke) is extended to previously unexploited fishing grounds in search of lucrative marketable species. Some individuals take the trip several times over consecutive years, others may stay on for more than one season, and yet others may end up marrying local residents.

Figure 1. Migration route of Vezo fishers to the Barren Isles. Source: Adapted from data presented in Cripps and Gardner (Citation2016) and Cripps (Citation2010)

Seasonal migrations usually take place between March and November but the departure date may vary (). The migration can be divided into two categories. First, there is the migration to target sharks and sea cucumbers around Maintirano. They usually take place around August when the conditions are best for shark fishing and sea cucumber diving (Cripps & Gardner, Citation2016). The second type of migration is the long-distance migration for fin fish. These migrations are often seasonal especially for high-value resources but they can also be definitive towards the mainland or some of the islands of the west coast. Vezo fishers that undertake migrations are organized in teams led by the owner of the boat and fishing gears. The latter then recruits siblings or family members of the spouse. Fishers can also be sponsored by shark fish and sea cucumber buyers that provide fishing boats, material and subsistence. Vezo fishing boats are dug from farafatsy trees (Giviotia madagascariensis). The boats are longer (7–8 m) and deeper-hulled than boats used by fishers in coastal villages. They are more appropriate for long-distance ocean-going (Cripps, Citation2009).

Migrant fishers from the southwest coast access the Barren Isles either directly through ports of call further south on the mainland, or via Ampasimandroro, the large fishing village near Maintirano where most migrant fishers establish a permanent base. The village community of Ampasimandroro near Maintirano consists of local Sakalava people, immigrants of the Sara clan from Anakao (a large Vezo village on the southwest coast near Toliara) who arrived three generations ago, and more recent Vezo immigrants and seasonal migrants. Affiliation to these groups is established bilaterally by maternal and paternal descent. Immigrant Vezo men integrate by marrying local Sakalava women and fathering Sakalava children whereas the local Sakalava fishers also self-identify as Vezo (or ‘Sakalava vezo’, as they say) simply in virtue of being fishing people.

Vezo migrations have been motivated by different factors. The most important is the reduction of marine resources in the Southwest due to the degradation of costal ecosystems but also the rapid population growth and the lack of alternative livelihoods for the Vezo (Cripps & Gardner, Citation2016). The economic factor is also important in the migration. While the Vezo have been involved in trading marine products like shells and dried fish since the 1960s, it is since the 1990s that the seafood market has been highly influential especially with the rise of the lucrative Chinese export market for sharks and sea cucumbers (Grenier, Citation2013; Muttenzer, Citation2015). Migration to the Barren Isles has also been motivated by the higher productivity of the marine ecosystems around the islands due to their remoteness. Authors like Cripps and Gardner (Citation2016) and Muttenzer (Citation2020) have characterized Vezo migration as an adaptive resource management strategy allowing Vezo fishers to benefit from available resources despite existing scarcities. Another factor is social, leading fishers to undertake migrations to fund personal projects or acquire material belongings for their home base in the South.Footnote5

3.2 Marine and coastal resources accessed by migrant fishers

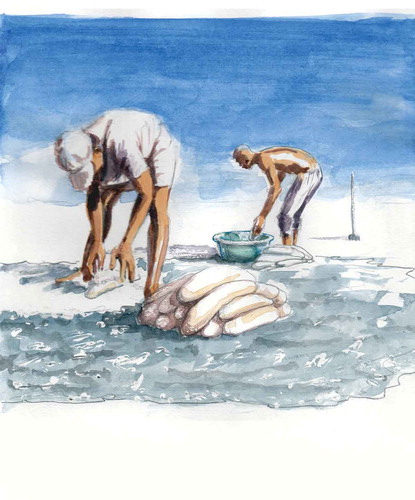

Along their migrations from the south to the west of the Malagasy coast, Vezo migrants have caught various marine species (). Until the 1970s, Vezo migrants targeted marine species for the subsistence both for consumption and exchanges for starch with inland farmers (Iida, Citation2005). On the Barren Isles, shark fishing and sea cucumber diving are the two most important activities of Vezo migrants. Free-diving of sea cucumbers being highly dependent on weather conditions, Vezo fishers often set their shark nets before diving for sea cucumbers (Cripps et al., Citation2015). In 2007 migrant fishers encountered on the islands explained to the first author that people go there to catch sharks. Shark fin is a highly prized product bought by local Chinese traders who then export it. In the meantime, sharks became scarce. At the time of the first author’s second visit to the islands in 2012, migrant fishers had mostly redirected their efforts to certain species of sea cucumbers which are likewise a highly prized product exported to China.

Table 3. Species targeted by Vezo and related fishing gears (Sources: Barnes-Mauthe et al., Citation2013; Iida Citation2005; Muttenzer Citation2015; Grenier Citation2013)

Due to the mobility of the Vezo and remoteness on the Barren Isles, it is difficult to estimate the quantity of marine resources harvested by Vezo fishers in their migration journey. Only estimations on different resources are available. A series of value-chain studies mandated by the FAO discuss shark and sea cucumbers fisheries in Madagascar. It was estimated that in the Maintirano area (the closest city from the Barren Isles), 1,2 to 1,8 tons of shark fins were collected every year (Cripps et al., Citation2015). Fishers interviewed in the study reported catching between 16 and 40 sharks a month (ibid). Similarly, an amount of 1,6 tons of sea cucumbers per year per migrant fisher work group was produced in the same area (Andrianaivojaona, Citation2012). This quantity of sea cucumbers represents double the amount fished by local fishers that do not undertake migration in the remote areas of the Barren Isles. It was also estimated that around 1,100 migrant fishers were involved in sea cucumber diving (ibid).

Beyond livelihoods, Vezo fishers have also used the Barren Isles as shelters, settlements and processing spaces. Vezo settlements are often made from driftwood and grass, using coral rubbles and sometimes masts and sails of their boats (Cripps, Citation2019). Despite the insufficient quality and amount of available drinking water (which has to be shipped from the mainland) and of infrastructures, Vezo fishers are able to accommodate their families. They also use available resources on the islands to build drying pens for processing fish and sea cucumbers.

3.3 Financial benefits

Incomes from these fisheries vary according to productivity of fishing grounds and fishing efforts of fishers. Fresh fish is much less valuable than shark fins and sea cucumbers. Cripps and Gardner (Citation2016) presented that while fresh fish and octopus are priced at 0.5 US$/kg, shark fin are sold at 94–105 US$/kg (dried) and sea cucumber at 13 US$/individual or 17 US$/kg (unprocessed). Andrianaivojaona (Citation2012) established that migrant fisher work groups made a profit of more than $US3,000 (MGA 7,000,000) per year diving for sea cucumber. Cripps et al. (Citation2015) interviewed shark fishers that stated earning between $US 221 (MGA 500,000) and $US 442 (MGA 1 million) for a two-month fishing trip (an equivalent of around $US 990 to $US 1,900 for the 9 months season). Compared to non-migrant fishers, these revenues are important in the Southwest seascape of Madagascar. Barnes-Mauthe et al. (Citation2013) presented that local fishers in the Velondriake area (where many Vezo migrant fishers come from) earned around $US 1,900 for shark fishing and $US 1,300 for sea cucumber diving, per year (around 224 fishing days). Revenue from sea cucumber diving in particular represents more than double of what local fishers would earn in their local village.

3.4 History of the Barren Isles MPA

The Barren Isles represent one of the marine hotspots in Madagascar, covering over 4,300 km2 of coast and ocean. Mainly due to their remoteness, the Barren Isles host not only productive fishing grounds but also many marine species with high conservation value including 39 coral genera and 150 species of fish (). In 2017, the Barren Isles have also been granted the status of wetland area of international importance under the RAMSAR convention.

Table 4. Marine resources and ecosystems with conservation interests on the Barren Isles. (Source: Cripps, Citation2010)

Conservation interests were initially limited to nesting sites of sea turtles and certain bird species, but now include the entire group of islands and large stretches of coral reef. While the site has been recognized by the government for many years as a potential site for a protected area, its conservation was initiated by the WWF and Blue Ventures (BV). BV is a UK-based NGO that had been promoting marine conservation in Madagascar for almost 20 years, originally implementing fisheries temporary closures along the west coast. BV also led the movement of locally managed marine areas (LMMAs) in Madagascar, which has now evolved into an independent network (MIHARI) of more than 220 sites in the country. BV started working towards the protection of the Barren Isles since 2010. They opened a branch office in Maintirano in 2011 and conducted a feasibility study for the MPA mandated by the WWF. In November 2014, the government granted a preliminary protected status as the largest MPA in the country. The MPA is an IUCN multi-use category MPA which allows different uses of the resources according to the zoning of different areas. At the time of writing, the management plan was under development and consultations of local actors are planned by NGOs including on the different uses and zoning in the MPA (NGO staff, personal communication, 30 January 2021).

In 2015, the Vezo Miray Nosy Barren association (VMNB) was created as a co-management group of the MPA and is now officially recognized as a co-manager of the MPA together with BV. The VMNB is constituted by Vezo fishers that have permanently settled the Maintirano region or regularly migrate to the Barren Isles. It is represented by elected leaders from six coastal villages and seven islands. The association has a management committee, a committee in charge of applying the community-based laws (dina), and a group of community monitoring agents. In 2016, the Barren Isles was also part of a regional fisheries management plan established by the Ministry in charge of fisheries. Under the fisheries management plan, different fishing activities such as industrial trawling or use of diving tanks were prohibited within the Barren Isles and local fishing associations were recognized more rights towards the management of the resources (Government of Madagascar (GoM), Citation2016). As part of the management, migrant fishers coming to the Barren Isles were required to register as Barren Isles fishers to the VMNB if they wanted to continue to access the resources. Fishing effort in the area has also been managed by capping the number of fishers allowed to those registered and reviewed every 2 years (Government of Madagascar (GoM), Citation2016, Art. 19, p. 12).Footnote6

3.5 The role of ritual in resource access regimes

Individual fishers in a work group are responsible for performing required rituals and avoiding fights with peers, lest the spirits get angry and their charms will not work (). Anointing their bodies, diving masks and fins with the mixture of holy water and ground wood is part of a ritual cycle through which divers are able to overcome their bodily limitations and gain the power of sight necessary for spotting and spearing the valuable sea cucumbers on the ground of the ocean.Footnote7 There are other conditions for success with sea cucumber diving. To benefit from a fishing charm’s blessing and power, individual migrants must be at peace with their direct family ancestors; they must be at peace with other members of their work group, that is avoid conflicts and work together with them under the influence of the same charm; they must have confidence in themselves, and honour promises they made to spirits; not least, they must submit to the desires of place spirits that ‘own’ the frontier areas used for sea cucumber diving. As for other rural Malagasy, undomesticated nature is seen as abode of spirits that are said to be the owners or masters of the places they inhabit (Faublee, Citation1953; Sodikoff, Citation2012). The specifically Vezo spirits are those associated with the sea. Marine islands, embouchures, and coral reef passes have spirit masters dwelling in trees, rocks or water. These spirit masters appear (miseho) sometimes in the form of mermaids. As Bontira, one key informant and guardian of sacred lore pertaining to the Barren Isles, explained:

On Nosy Lava (Long Island), there are spirit beings which must be served. There are eight of them. Two really are no longer spirit owners. The other six are still worshipped by the people. At the Tamarind tree, and in the waterhole, there are beings (raha) that appear (mitranga), they are ghosts. The taboo being (raha faly) gets angry (meloky) when there is something it doesn’t like. When there is a dead body for example, bringing corpses on land really is something one must absolutely avoid over there on the islands.Footnote8

Among the first seasonal migrant fishers to permanently settle in the region, Bontira said the knowledge of local taboos and sacred lore was handed over to him by a famous masy (diviner and healer). Although not a spirit medium himself, he explains that he ‘talks to’ the mermaids and that one of his daughters is possessed by Soalety, a mermaid child. Bontira is usually approached first by other migrant fishers when some problem requires ritual intervention. For example, in 2008, a migrant fisher drowned while diving on a coral reef next to one of the islands. Fatal accidents happen every year and fortunately in this case, the body could be recovered. The trouble started because the corpse was brought on shore instead of being transported directly to the main coast, likely due to bad weather which forced them to break the taboo on bringing dead bodies ashore on the nearest island:

The custom we enacted to take away the [breach of the] taboo is as follows. We asked for the decision [thought, opinion] of the village elders. Then each of us made a financial contribution so we could buy a bull. The official authorization was already issued by the village president in exercise in those days. But we had not yet gathered enough money to buy the bull for the sacrifice. This was in 2008, when they brought the corpse there on the island. Resamo [a village elder] made the first invocation. The second invocation was made by Bontira [the speaker]. We poured the soft drink into a bucket and we served it to the spirit at the tamarind tree. We offered soft drink mixed with the bull’s blood. We also poured it onto the coral reef that killed the diver. We poured it into the ocean.

The purported effect of the sacrifice, its meaning as described by the speaker, is to cleanse the sacred site that had been defiled by the transgression of the taboo. The other possible paraphrase is that the sacrifice purports to appease the spirit that got angry because there was something it did not like. The two descriptions are synonymous. What is being done to the spirit’s mental state is perceived only through its identification with concrete material actions of first bringing the corpse ashore and then cleansing the defiled place by serving the mixture of blood and soft drink to the angry spirit, and by pouring it onto the coral reef where the diver had drowned.

Bontira described himself as the first seasonal migrant from Andavadoaka, an ancestral Vezo settlement on the southwest coast, who settled permanently in Ampasimandroro, the fishing village near Maintirano. He claims having obtained the needed information about the islands’ taboos and sacred lore from a knowledgeable diviner in Tambohorano who initiated him into guardianship of the sacred sites. While seeming to occupy this role by self-appointment or self-presentation, his authority on ritual matters concerning the islands is widely acknowledged by the migrant fishers, who also consider him as their representative in village administrative matters. The information was presented to the first author as an inventory listing all the sacred sites, including revelatory events and rules to be followed separately for each of the eight islands (see for comparison). Here only a few examples will be quoted for illustration:

Nosy Mangily and Nosin-drano:

On the east side of Nosy Mangily, there is a large Tamarind tree. This island is close to another island called Nosin-drano, where there used to be Tamarind as well, and a large palm tree next to it where people worship the divinities.

We make a request when things don’t go the way they should, for example, we ask for the weather to calm down soon, or sometimes there are newcomers like you, strangers who pass by there and ask if there is any problem about the place, no there is not. Whether one is a foreigner or Malagasy, all of us can make requests. The spirit beings there say they need rice for them to cook and they ask for honey that is not transformed but as it comes from the market. And this honey we use to make requests at the cement block to obtain what is needed. It is the same again in Nosindrano:

There is a female one called Old Lady Knotted Braids (Ndrarahy be mitaly mivoho) and there also is a bald old man whose name is Big White (Foty be). They both lived on Nosilava first, and they also lived on Nosy Abohazo.

You know, these non-Christian spirits still go around freely and some of them are not called upon. In the place where they live there are many species of those beings. But to call them we call the father of those tromba [spirits that possess humans] called Big White and the Grandmother Knotted Braids. They spread the word “there are people calling us, they bring food”. So we call them first “we ask you place spirits (koky be)! Guide us, we who come from here, we come from here walking around, guide us well! Everything’s fine with us here!” That’s what we tell them.

Nosy Manandra:

There is a sacred spirit on Nosy Manandra. Its name is Grandmother Knotted Braids, the one that talks to Bontira. It needs to be given food in clamshells. When you want something, you give it four or six clamshells before you ask. And a coin of 20 Ariary. And honey, it will be eaten you put it in a soup bowl or a plastic cup. It gets angry if it does not eat. For example, when a sea spirit dies it will move like a shark. It likes little children. And it appears to people. Once there was a sea spirit who died, and the mother would appear every day because she was angry. She possessed human hosts [spirit mediums] and cried. It got better only when we made an offering and a request. The local community had to buy soft-drinks. We erected a sacrificial stone and made the request.

Nosy Marify:

On Nosy Marify a sacrificial stone two to 3 m in length has been erected. When people perform a blood sacrifice, things must be brought to the stone. In 2009 a person from Maintirano transgressed a taboo on Nosy Marify. The young lad who had urinated at the taboo stone fell sick. There was no one who dared to do the request to the spirit [to forgive the taboo breach]. In the end Bontira [the speaker] had to do the request. The reason was that he likes the Islands, he knows everything about those islands. When the request was made, the young lad made the sacrifice and became possessed by the spirit he had offended.

The standard rationale for sacrifices performed at these stones is to cleanse a defiled place by apologizing to the spirit because someone voluntarily or involuntarily transgressed its taboos. The case-narratives of revelatory events evoke an array of observable indications revealing the spirit’s presence in the environment and in human beings, its mental states, what to do about them, and so forth:

Everyone already knows, if one needs something from the spirits (to make a request) one follows the Tamarind tree. All people who fish there make requests for obtaining a good harvest. As far as animals are concerned, it is forbidden to kill any kind of animal living there on the islands. There are snakes on Nosin-drano, but there aren’t any on Nosy Dondosy. There are rats everywhere, except on Nosimboro and Nosy Dondosy. If these animals are killed, someone is going to die while on the island, and then, if there is a corpse there, a zebu will have to be sacrificed to make the requests.

Ordinary fishers’ knowledge of sacred lore is limited to taboos and rules for offerings and requests. For the detailed information they defer to Bontira’s authority. In following these ritual rules, seasonal migrants accept the ‘the content of other minds without necessarily knowing the whys and wherefores of the propositions and actions one performs’ (Bloch, Citation2013, p. 17). The deference to Bontira’s authority in ritual matters blocks shared doubt and legitimizes people’s trust in esoteric knowledge. But it does not preclude their understanding what a taboo, offering or sacrifice is about. Ordinary fishers know that killing rats on the islands or bringing corpses ashore may result in more deaths, and that purported consequences of transgressing these taboos can only avoided by a compensatory sacrifice to the offended spirit. What this shows is that ritual agents cannot defer to specialists’ knowledge without having understood the purported consequences of ritual infelicity on their part.

Rituals are an example of actions migrant fishers would not perform or would perform differently if there were no sacred places inhabited and owned by mermaid spirits. Rituals also produce and reproduce such places. Unless people had indications of mermaid spirits, they would neither respect their taboos nor erect sacrificial stones acknowledging their presence at tamarind trees.Footnote9 But there is no reason for associating revelatory experiences exclusively with fishers’ ritual practice rather than with their livelihood practice more generally. In either case the difficulty is to show that indications by spirits are a plausible reason for actions people can be observed to undertake.

4. Discussion

The actions described in the previous paragraphs relate to migration and sea cucumber diving. They raise the question whether and how the performing of rituals might contribute to migrant fishers’ ability to benefit from resources. Migrant fishers causally affect sea cucumber populations through the way they fish. Whether the ritual also makes a difference to how the fishers dive for sea cucumbers is an open question. One of the consequences of ritual performances is that they establish access claims by demonstrating performers’ relationship to the land. But one should keep in mind that the ritual system responsible for this outcome is not literally about access claims or property relations. Its stated purpose rather is to maintain the natural fertility or productivity of the ocean, ensuring that performers will continue to catch marine species understood as gifts from god or lesser spirits active in the environment.

The ethnography presented suggests that specific events in fishers’ livelihoods can affect the practice of taboos and sacrifice in sacred sites. For example, their decision to attribute a deadly accident at sea to a taboo breach rather than a natural cause, or to perform a sacrifice to cleanse a defiled sacred site rather than let things be, is not a matter of blindly following ritual rules. Other circumstances in people’s lives, such as the establishment of a protected area in a marine resource frontier, may also influence their judgment in matters of taboo and sacrifice. For example, because a sacrifice to an offended spirit signals the performers’ relationship to that spirit’s territory, the obligation to perform a sacrifice (after a taboo has been breached) constitutes a unique opportunity for signaling an ownership claim over that territory. Although common property claims are not literally what taboos and sacrifice mean, they can be used to signal common property because the decisions to perform or not to perform a ritual in given situations are matters of judgment, and as such, are necessarily influenced by non-religious considerations as well. One such consideration is the desire of having one’s fishery commons recognized by the protected area association.

The globalization of the fisheries targeted by the Vezo has strongly contributed to the depletion of resources in the Barren Isles. While fishing effort from Vezo fishers is substantial in these remote islands, competition for resources keeps increasing with other fishers including illegal sea cucumber divers.Footnote10 These are often better equipped than the Vezo, diving with scuba gear rather than free diving as the Vezo do traditionally. They are funded and paid by intermediaries and bosses from cities involved in shark fin or sea cucumber trade. This strong impact by the global market requiring a high supply of the resources targeted by the Vezo has led to a more highly paced exploitation of the resources by Vezo and other new actors targeting these resources. While Vezo fishers perceive the sea as inexhaustible and a common property of all (Grenier, Citation2013), resource depletion caused both by their own fishing and by outsiders significantly reduces the flow of benefits from the islands. In their scheme of understanding, the use of rituals acts as a means to maintain well-being by controlling resource access and reducing outside pressures on the resources.

In parallel to seasonal migrations, Vezo fishers have also integrated the conservation movement. There are two drivers behind this integration. One is through the involvement of NGOs such as Blue Ventures especially in the Southwest of Madagascar. Adopting a community-based approach and promoting the need for locally managed marine areas, Blue Ventures has put Vezo fishers in the middle of this management as one of the most important users of the sea. While Vezo originally believed that MPAs are an encroachment on the common property of the sea, the marine conservation movement in Madagascar has made some Vezo into environmental subjects, who now view themselves as stewards of the environment and persuade other community members to do so as well (Agrawal, Citation2005).

A discursive power has emerged following the promotion of the benefits of management to which the Vezo have adhered, and led to their agreement to NGO actions including by actively taking part in the management. The Vezo have become ‘environmental defenders’ of the sea (Gardner, Citation2016). We also argue here, that beyond this ‘environmental subject’ creation, migrant fishers also joined the conservation movement by wanting to be involved in the management decisions of their fishing grounds and ultimately to control access to the marine resources. Being involved in the management of the Barren Isles allows migrant fishers to take part in setting the customary convention (dina) establishing what can be allowed in the area and how actors can access the Barren Isles marine resources. By becoming members of the local association VMNB for example, migrant fishers are also given authority to control and monitor their fishing areas and the number of fishers allowed in the area. While the establishment of MPAs necessarily involves the limitation of access to some fishing grounds, the integration of Vezo fishers in the process of creation of the MPA requires NGOs to carefully choose the no-take-zone areas. These would not undermine access by migrant fishers, respecting sacred sites, while also protecting the marine resources from overexploitation by migrant fishers and other actors such as mining or oil and gas companies prospecting in the area. In the creation of the MPA, the government and conservation NGOs confront local resource users as a single group regardless of origin. But the main two groups of local resource users, Sakalava masters of the land and Vezo migrants or immigrants, are unevenly affected by the marine protected area. Migrant fishers are most directly affected because they have no other activity than diving for sea cucumbers. The Sakalava masters of the land are less affected while acting as intermediaries between governmental agencies and those less established Vezo newcomers.

This political constellation might also explain the specific uses to which taboos and sacrifices are put, namely to establish migrants’ resource access in non-Vezo, Sakalava territory. Sacred sites are found on islands which happen to be of strategic economic interest to migrant fishers. But this coincidence does not mean the ritual can be explained solely by the geopolitical interest people have in these islands. The sacred sites in the Barren Isles were not tabooed because and after migrant fishers started to have an economic interest in selling valuable shark fins and sea cucumbers to Chinese traders. Rather, the existing taboos and sacred sites took on a new function and significance when the global fishery and conservation-related interests emerged. A sacrifice can be used by people to bring about a relationship with the land or assert a claim to access fishery resources without directly saying so. Customary ownership of the land, in rural Madagascar, is part of the indexical messages transmitted by these kinds of sacrifices no matter how many, nor whether any performers consciously intended to show their relationship to the land or make a resource claim.Footnote11

As argued by Rappaport (Citation1979, p. 174), ‘Ritual is without equivalents or even alternatives’, because it can be used to show something or make a point without saying it. It can be used to show these things (i.e. claim access) because of what it is literally about (i.e. appeasing mermaids), which meaning it has even if there are additional goals and reasons that motivate the performers. That the resource claim is indirect and tacit does not mean people are unaware of, or mystified about, the signaling effect of a sacrifice which on the face of it purports only to appease the mermaid. The sacrifice described by the first author can be used to communicate a resource claim precisely because the literal meaning is to appease a specific mermaid from a specific place of which access is contested.

5. Conclusion

In this article, we described the ways in which migrant fishers gain and control access to marine frontiers both by performing ancestral rituals by which newcomers attach themselves to places of economic interest not yet claimed by locals, and by virtue of an environmentalist identity narrative that constitutes both migrants and local fishers as stewards of the environment and praises (or blames) them for their actions based on scientific criteria rather than ritual narratives. In the ritual narrative, common property of fishing grounds is asserted, and livelihood defended by migrant fishers against competing commercial fishing and conservation interests by claiming that the Barren Isles are inhabited and owned by mermaids. Taboos and sacrifices performed at the mermaids’ sacred sites are not explicitly framed as an alternative to marine enclosures. But for the migrant fishers, the ritual addressed to spirits masters of the islands turns out to be a unique way of defending the unenclosed commons against economic competitors, while at the same time being recognized by the protected area as the rightful ‘ancestral owners’ of the fishery commons.

In this way, migrant fishers have become key actors in the management of marine resources while maintaining their ancestral practices. West and Brockington (Citation2006) refer to this transformative aspect of protected areas as ‘virtualism’. The MPA being multi-use it is possible to allow or prohibit things on different zonings. Vezo joined the management association because they were told taboos could be kept. Although the taboos and sacrifice are not conceptualized as an alternative to protected areas or marine enclosures our case study shows that they are a unique way of defending the unenclosed commons against potential access restrictions. Together with community stewardship of the ocean, people invoke taboos and sacrifice to maintain access to the commons. There could be no better safeguard against conservation enclosures. The reason why migrant fishers can keep using these rituals to defend unrestricted access to the unenclosed commons is that the protected area thus far exists mainly on paper.

Blue Ventures’s conservation scientists explain that stopping migration would just make traditional fishers even poorer while marine protected areas help them defend livelihoods from encroachment by outsiders, and that migrant fishers attracted by markets for shark fins and sea cucumbers now join efforts to protect the ecosystem and expel illegal divers (Cripps & Gardner, Citation2016). An ‘environmental subject’, in Agrawal’s (Citation2005) sense, is someone who signals the will to improve the fishery on behalf of other people who count as having the will to improve the fishery by virtue of controlling and maintaining access to fishing grounds of marine protected area. One question raised by our case study is whether ‘taking part in the management’ of a virtual protected area constitutes a good enough reason to praise migrant fishers as environmental stewards and ocean defenders, given that the current ‘virtualism’ (West & Brockington, Citation2006) while waiting for enforceable access restrictions entails little more than simply living and working there.

Conservationists point out that ‘gangs of illegal divers with motorboats and scuba equipment can hoover up sea cucumbers in much greater quantities’ than traditional skin divers, and even that ‘they operate with impunity in a country that lacks the capacity to enforce its fishing regulations’ (Gardner, Citation2016). That the majority of migrant fishers may have an interest in expelling illegal divers using scuba equipment does not necessarily show that they can actually ‘defend the ocean.’ It shows only that they compete with other users and exploitative traders for income from sea cucumbers. The migrant fishers in the Barren Isles MPA also illustrate the parallels between conservation discourse and ancestral discourse and how each side signals commitment to the other, thereby avoiding conflict, without actually committing or believing in the other. Neither side are able to address the root causes of depletion, namely the unregulated market and the exploitation of small-scale migrant fishers within that market.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the editors and the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions that improved the earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by Frank Muttenzer. Mialy Andriamahefazafy has been a former employee and is currently an advisor for Blue Ventures. She co-authored the paper in her capacity as an independent researcher.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Frank Muttenzer

Frank Muttenzer is Privatdozent of Cognitive Anthropology at the University of Lucerne with research interests in the anthropology of religion, human-environment relations, and ethnographic methods of cognitive science. He is the author of Déforestation et droit coutumier à Madagascar, Editions Karthala, 2010, and Being ethical among Vezo People, Rowman & Littlefield, 2020.

Mialy Andriamahefazafy

Mialy Andriamahefazafy is a human geographer specialized in fisheries management and ocean governance. Her interests focus on our relationship with the ocean and its inhabitants through a political ecology lens. Her key researches investigate the politics of tuna fisheries in the Western Indian Ocean and the implementation of SDG 14.

Notes

1. Sara people are a subgroup of the Vezo. In their ancestral village they also have terrestrial sources of livelihoods and they maintain certain cultural aspects specific to them in particular the tendency to marry other Sara. But Sara fishers also identify themselves as Vezo through their livelihood at sea and just like other Vezo they migrate along the southwest and west coast.

2. So-called ‘ethnic groups’ of Madagascar could not be reproduced without such marriage expectations. In fact these groups are better described as inmarrying groups. In order to understand the role of ‘identity narratives’ in fisher migrations along the west coast it is useful to keep in mind that the principles governing descent and ethnicity are the same as elsewhere in Madagascar. While Malagasy ‘ethnic’ groups are territorial groups not descent groups, individual membership in such territorial groups is transmitted by descent. An individual is Vezo (Masikoro, Sakalava, Mahafale, or Sara) if either parent’s family tomb is located on Vezo (Masikoro, Sakalava, or Sara) territory. The ethnic grid is materialized by family tombs which are located on a particular territory, known as the ‘ancestral land’. Territorial group members are supposed to marry into families from the same territorial group whose family tombs are also located on the said ethnic territory, and in this way the territorial ethnic map is preserved unchanged over generations. For example, some of the descent groups with family tombs in Vezo territory, such as the Sara of Anakao and some of the clans described by Marikandia (Citation2001) remember an ancient migration history which tells where a particular descent group came from and how they settled in Vezo territory. Each of those descent groups may in addition have its own taboos (also mentioned in the group narrative). But the important point is that these descent groups all became Vezo once they built family tombs in Vezo territory.

3. The ritual system establishes a common property regime for coral reef fisheries rather than an open access regime to the sea. The unenclosed fishery commons ensure that Vezo migrant fishers may access the fishing grounds along with the Sakalava local resource users. The migrant fishers’ situated knowledge of where to fish what at which period of the year and in accordance with which taboos determines their migration routes and their sites of fishing specific resources. Finally, rituals performed in their migration and within their subsistence activities are understood to allow them to maintain their livelihoods in accordance with their economic needs as participants in global fishery markets and social identity as ‘people of the sea’.

4. The establishment of an MPA in the Barren Isles has put in place access restrictions to fishing grounds and different species. However, the Vezo, either involved by the NGOs or by mobilising the argument of customary access, have taken part toin the setup and/or implementation of these rules. Conservation measures have become one of the ways for the Vezo to have exert control over access to resources in the Barren Isles.

5. Financial benefits obtained from high value resources can also be used by Vezo to complete their house construction, furnish their households with electronics such as TV and speakers or buy living-room sets (Muttenzer, Citation2015).

6. In this context of conservation and management, Vezo continue to access and take part in the management of the Barren Isles by two means, either as members of the VMNB if they have established themselves in the region or by registering as migrant fishers to the local association if they have been regularly (yearly to bi-annually) migrating to the Barren isles.

7. By submitting to the ritual order, performers attribute their individual powers of sight as successful sea cucumber divers to the intervention of external agents such as family ancestors, other work group members, place spirits, spirit mediums, and fishing charms. The performer’s own bodily agency as a diver is amplified and improved through enrolment of other agents external to his body but to whose will his own will is now attuned. Not performing the ritual is tantamount to renouncing the power of sight and having one’s agency restricted by one’s own body. Prior to longer fishing trips, migrants consult the spirit medium where they promise a gift to the spirit in exchange for the charm. The pledge outwardly commits the client to take the necessary steps to confirm what has been foretold during the ceremony. His motivating reason for honouring the pledge is that he expects the diviner to be truthful. At the same time the divination is more likely to come true if the client takes the diviner at her word. In cases of failure it is commonly said that the diviner was not sincere, or that she did not hold the ritual correctly (Muttenzer, Citation2020, chapter 8).

8. The full narrative version of how place spirits behave island by island quoted here is the most detailed information and was recorded from a single informant, Bontira. Migrant fishers from the 35 work groups that were interviewed in the survey described in the methods section all perform the offerings taboos and sacrifice and they usually refer to Bontira for the more detailed knowledge about how to perform the ritual. However, spirit mediums among the fisher work groups on the island also receive new indications about place spirits and the ritual narratives may evolve accordingly.

9. This raises a difficulty. What can be observed ethnographically is not the revelatory experience itself, but only what informants say about such experiences, and the type of actions the reported experience motivates. The fishers themselves encounter the same difficulty. Second or third hand reports of revelatory experiences are mentioned by them as reasons for action even if they personally doubt or disbelieve them but have other reasons for accepting and act on such reports. As argued by Bloch (Citation2013, p. 17), ‘In ritual one accepts that the motivation for meaning is to be found in others one trusts.’ What matters is not the lived experience but that reports of indications are intelligible and seem plausible, because the audience trusts the speaker’s authority.

10. The identity narrative expecting Vezo individuals to ‘live with the sea’ has implications for resource access and the different types of power that can emerge. Migration allows Vezo to access remote and isolated sites of production that are not available to other local fishers, whose training and skills are less specialized than those of the Vezo. The high value of the resources migrant fishers have access to provide them a financial power for both subsistence but also for personal projects. While Vezo are often portrayed as the most vulnerable part of the population due to their dependence on a depleting sea (Moreira et al., Citation2017), they can also accumulate wealth from the migration which is materialized by their fishing gear and household objects brought back to their village of origin. The economic benefits from the Barren Isles marine resources, while maintained by the yearly recurrence of Vezo fishing in the area, are still limited in time and space. Fishing for a specific resource is most productive at specific times of the year (as described in ) and some islands have different resources more productive than others. Similarly, depletion events with regard to certain species such as sharks, as witnessed in the south, have also been observed aroundthe Barren Isles. Fishers have already stated they experienced fishing less and less every year (Humber, Citation2014).

11. Just as a wedding cannot but bring about marriage, ritually appeasing a mermaid from a specific island cannot but bring about a relationship between the ritual appeasers and the island.

References

- Agrawal, A. (2005). Environmentality: Community, intimate government, and the making of environmental subjects in Kumaon, India. Current Anthropology, 46(2), 161–190. https://doi.org/10.1086/427122

- Andriamahefazafy, M. (2020). The politics of sustaining tuna, fisheries and livelihoods in the Western Indian Ocean. A marine political ecology perspective [PhD Dissertation]. Université de Lausanne. https://serval.unil.ch/en/notice/serval:BIB_7E0D668DF275

- Andrianaivojaona, C. (2012). Analyse Globale de la Gouvernance et de la Chaîne d’Approvisionnement de la Pêcherie du Concombre de Mer à Madagascar(SF/2012/25). Report of the Indian Ocean Commission. http://www.fao.org/3/a-az395f.pdf

- Astuti, R. (1995). People of the sea: Identity and descent among the Vezo of Madagascar. Cambridge University Press.

- Barnes-Mauthe, M., Oleson, K. L. L., & Zafindrasilivonona, B. (2013). The total economic value of small-scale fisheries with a characterization of post-landing trends: An application in Madagascar with global relevance. Fisheries Research, 147(2013), 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2013.05.011

- Bennett, N. J., Govan, H., & Satterfield, T. (2015). Ocean grabbing. Marine Policy, 57(2015), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.03.026

- Bloch, M. (1971). Placing the dead: Tombs, ancestral villages, and kinship organization in Madagascar. Seminar Press.

- Bloch, M. (2013). In and out of each other’s bodies: Theory of mind, evolution, truth, and the nature of the social. Paradigm Publishers.

- Ciriacy-Wantrup, S., & Bishop, R. (1975). “Common Property” as a concept in natural resources policy. Natural Resources Journal, 15(4), 713–728. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24880906

- Cripps, G. (2009). Understanding migration amongst the traditional fishers of West Madagascar (Blue Ventures conservation report for ReCoMaP). Blue Ventures.

- Cripps, G.(2010). Feasibility study on the protection and management of the Barren Isles ecosystem, Madagascar (Blue Ventures conservation report). Blue Ventures. https://blueventures.org/publication/feasibility-study-protection-management-barren-isles-ecosystem-madagascar/

- Cripps, G.(2019). Chasing the far, far away fish. Hakai Magazine. https://www.hakaimagazine.com/videos-visuals/chasing-the-far-far-away-fish/

- Cripps, G., & Gardner, C. J. (2016). Human migration and marine protected areas: insights from Vezo fishers in Madagascar. Geoforum, 74(2016), 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.05.010

- Cripps, G., Harris, A., Humber, F., Harding, S., & Thomas, T. (2015). A preliminary value chain analysis of shark fisheries in Madagascar (SF/2015/34). Indian Ocean Commission. http://www.fao.org/3/a-az400e.pdf

- Deschamps, H. (1959). Les migrations intérieures passées et présentes à Madagascar. Berger-Levrault.

- Douglass, K., & Rasolondrainy, T. (2021). Social memory and niche construction in a hypervariable environment. American Journal of Human Biology, 2021, e23557. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.23557

- Failler, P., Binet, T., Agossah, M., Meidinger, A., Turmine, V., & Bailleux, R. (2020). La pêche migrante ouest-africaine: Un secteur refuge à bout de souffle. In V. Mitroï & K. De La Croix (Eds.), Écologie politique de la pêche: Temporalités, crises, résistances et résilience dans le monde de la pêche (pp. 85–105). Presses universitaires de Paris Ouest.

- Failler, P., & Binet, T. (2010). Sénégal. Les pêcheurs migrants: Réfugiés climatiques et écologiques. Hommes & migrations. Revue française de référence sur les dynamiques migratoires, 1284(2010), 98–111. https://doi.org/10.4000/hommesmigrations.1250

- Faublee, J. (1953). Les esprits de la vie a Madagascar. Presses Universitaires de France.

- Gardner, C. J. (2016, June 8). Madagascar’s ‘sea nomads’ are the new ocean defenders. The Ecologist. https://theecologist.org/2016/jun/08/madagascars-sea-nomads-are-new-ocean-defenders

- Government of Madagascar (GoM). (2016). Arrêté ministériel N° 23283/2016 Portant officialisation du plan d’aménagementc oncerté des pêcheries maritimes de la Région Melaky ainsi que des modalités prises pour sa mise en œuvre. http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/Mad179268.pdf.

- Grenier, C. (2013). Genre de vie vezo, pêche ‘traditionnelle’ et mondialisation sur le littoral sud-ouest de Madagascar. Annales De Geographie, 693(5), 549–571. https://doi.org/10.3917/ag.693.0549

- Harding, S. (2018). Chapter 6—Madagascar. In C. Sheppard Ed., World seas: An environmental evaluation (Second ed., pp. 121–144). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100853-9.00005-1

- Humber, F. (2014). A glimpse into shark fishing from Madagascar’s remote islands. Save Our Seas Foundation. https://saveourseas.com/update/a-glimpse-into-shark-fishing-from-madagascar-s-remote-islands/

- Iida, T. (2005). The past and present of the coral reef fishing economy in Madagascar: Implications for self determination in resource use. Senri Ethnological Studies, 67(2005), 237–258. http://doi.org/10.15021/0000/2670

- Koechlin, B. 1975. Les Vezo du Sud-ouest de Madagascar. Contribution à l’étude de l’éco-système de semi-nomades marins. (Cahiers de l’homme No. XV). Mouton.

- Marikandia, M. (2001). The Vezo of the Fihereña coast, Southwest Madagascar: Yesterday and today. Ethnohistory, 48(1–2), 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1215/00141801-48-1-2-157

- Ministère des Ressources Halieutiques et de la Pêche (MRHP). 2013. Enquête cadre nationale 2011–2012

- Moreira, C. N., Rabenevanana, M. W., & Picard, D. (2017). Boys go fishing, girls work at home: Gender roles, poverty and unequal school access among semi-nomadic fishing communities in South Western Madagascar. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 47(4), 499–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2016.1253456

- Muttenzer, F. (2010). Déforestation et droit coutumier à Madagascar: Les perceptions des acteurs de la gestion communautaire des forêts. Karthala.

- Muttenzer, F. (2015). The social life of sea-cucumbers in Madagascar: migrant fishers’ household objects and display of a marine ethos. Etnofoor, 27(1), 101–121. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43410673

- Muttenzer, F. (2020). Being ethical among Vezo people: Fisheries, livelihoods, and conservation in Madagascar. Lexington Books.

- Ostrom, E., & Hess, C. (2007). Private and common property rights. Indiana University, Bloomington: School of Public & Environmental Affairs Research Paper No. 2008-11-01. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.193/6062

- Pascal, B. (2008). De la « terre des ancêtres » aux territoires des vivants: Les enjeux locaux de la gouvernance sur le littoral sud-ouest de Madagascar [PhD thesis], Museum national d’histoire naturelle - MNHN PARIS. https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel–00485894

- Rappaport, R. (1979). Ecology, meaning, and religion. North Atlantic Books.

- Ribot, J. C., & Peluso, N. L. (2003). A theory of access. Rural Sociology, 68(2), 153–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.2003.tb00133.x

- Schlager, E., & Ostrom, E. (1992). Property-rights regimes and natural resources: A conceptual analysis. Land Economics, 68(3), 249–262. https://doi.org/10.2307/3146375

- Sikor, T., He, J., & Lestrelin, G. (2017). Property rights regimes and natural resources: A conceptual analysis revisited. World Development, 93(2017), 337–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.12.032

- Sodikoff, G. M. (2012). Totem and taboo reconsidered: Endangered species and moral practice in Madagascar. In G. M. Sodikoff (Ed.), The anthropology of extinction: Essays on culture and species death (pp. 67–86). Indiana University Press

- Veriza, F., Chazan-Gillig, S., & Manjakahery, B. (2018). Les Vezo du littoral sud-occidental de Madagascar. Journal Des Anthropologues, 154-155(3), 261–283. https://doi.org/10.4000/jda.7337

- Veriza, R. F. (2019). Les yeux de la mer et les médecins de la mer: Des espaces sacrés des ancêtres aux aires marines protégées des vazaha sur le littoral vezo à Madagascar [Doctoral dissertation, Université de Bordeaux 3]. https://www.theses.fr/2019BOR30017

- West, P., & Brockington, D. (2006). An anthropological perspective on some unexpected consequences of protected areas. Conservation Biology, 20(3), 609–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00432.x