ABSTRACT

On the upper Niger, two river sections in Mali and Guinea are affected by family and entrepreneurial seine fishing practices leading to seasonal migration phenomena. Although the physical, cultural, social and political contexts are obviously not the same, the existence of entrepreneurial fishermen, owners of large seines – the joba – in Mali and of a smaller size in Guinea – the jolé – is the result of similar processes in terms of their economic organisation and their exploitation of the river environment. The different practices of fishing with the jolé and joba seine nets are important technical indicators of the degree of cohesion and consultation between fishing villages in the same region. In fact, the study of their practices and the places where they are practised informs us of the state of power relations existing on the river and the management of common aquatic territories.

1. Introduction

The understanding of fishing systems is linked to the variability of physical space, the mobility of fish stocks. They are thus constitutive of aquatic territories that circulate in both their physical and social dimensions reflecting ‘the nature of the society of “networked flow”’ (Magrin, Citation2013, p. 210). These mobilities for the fishing communities concerned are carried out owing to the village of origin, ‘the “back base” territory’ (Landy, Citation2010), which guarantees a place to retreat. Similarly, the mobility is made possible by family, ethnic and socio-professional networks, which ensure integration into the host territory and the socio-technical environment of fishing regulations. Here we come closer to the particularity of territoriality that J. Bonnemaison emphasises, ‘which is understood much more in terms of the social and cultural relationship that a group has with the network of places and routes that make up its territory […]’ (Bonnemaison, Citation1981, p. 254).

The successive displacement and settlement of the Bozo and Somono continental fishing societies in Mali and Guinea on the Niger River is notably linked to the different periods of political domination that have affected this region since the decline of the Ghana Empire towards the end of the 11th century, and the emergence of the Mali Empire up to the Bambara Kingdom of Segou in the 19th century (Fay, Citation1989a; Conrad et al., Citation2002; Kassibo, Citation1994). The migration of these communities to the West African coastal areas until the beginning of independence in the 1970s was marked by adaptation strategies that were both technical (pirogues, fishing gear, targeted species) and multi-active (agriculture and livestock farming), in contact with local populations and other migrant fishing communities (Bouju, Citation2000). An example of such migration is that of Malian fishermen who continue to move to the Saloum Delta or the Gambian delta to carry out a more lucrative maritime fishing activity (Failler et al., Citation2020), but in view of the political, economic and ecological difficulties faced by these migrant fishermen, they are gradually turning to fish processing when others attempt to leave for Europe (Binet et al., Citation2013).

On a sub-regional scale, the Inner Niger Delta (IND), the main centre of fish production in Mali, was marked by droughts during the 1980s, thus disrupting its hydraulic functioning and its entire ecosystem, which had already been severely altered by the construction of the Markala dam in 1947 and the Sélingué dam in 1981 (Ferry et al., Citation2012). The fishermen populations, politically under-represented and disadvantaged in the decentralization processes (Marie et al., Citation2014), have emerged even more fragile from these upheavals (Droy & Morand, Citation2013; Zwarts, Citation2005) which have forced major adaptation strategies, particularly migratory ones (Fossi et al., Citation2012; Jul-Larsen et al., Citation2001; Laë, Citation1992; Morand et al., Citation2012). Studies have focused on recent seasonal mobility from the inland delta region to strategic fishing points such as the dam reservoirs of Sélingué (Togola, Citation2009), of Manantali (Morand et al., Citation2012), of Talo (UEOMOA Citation2013) or even to urban centres such as Bamako (Croix (de la), et al., Citation2013).

Similarly, movements to collective fishing zones in the Manden region between Mali and Guinea, which can gather more than a hundred pirogues for 2 to 4 months on the upper Niger River, have also been observed (Croix (de la), et al., Citation2013). While the organisation of these collective migratory fisheries seems to respond to a partly egalitarian sharing of the resource and aquatic territories, other seine fishing practices on Guinean and Malian sections of the river are upsetting the established customary systems. These collective fishing campaigns, which are highly profitable because they are effective in relation to the fishing effort invested, are both the object of covetousness and of tension between fishing villages.

Conflicts erupt over both territorial and technical issues, which affect water controlFootnote1 (Fay, Citation1989b): The frequent recourse to state technical services and political representatives for arbitration issues, as well as legal action, attest to the degradation of social contracts uniting the villages together. While it is necessary to move beyond the debate on artisanal fishing, which forcibly refers to poor societies and overexploits the resource (an economic and biological paradigm), we are more in favour of an approach that favours the study of social and institutional mechanisms for maintaining fishing systems (Béné, Citation2003). In the face of environmental (climate change), anthropogenic (damage to aquatic resources) and geopoliticalFootnote2 (IOM, Citation2013) disturbances, we argue that the introduction of new forms of seine fishing, both entrepreneurial and migratory, responds to complex strategies for adapting to these new constraints.

2. Field, methodology and object of study

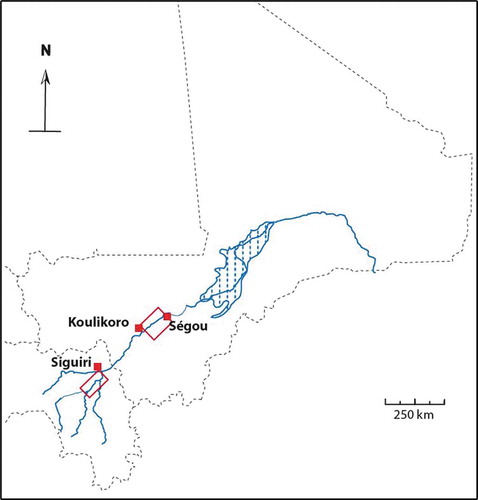

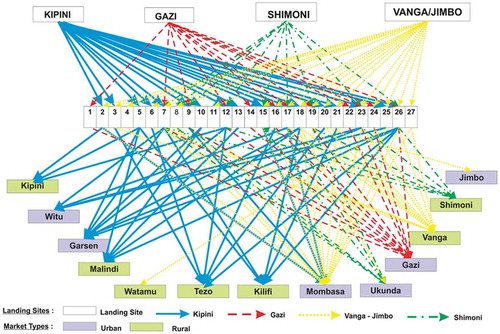

Two river sections of the Niger are concerned by such seine fishing: one in Guinea from the confluence of the Niger with the Niandan to Siguiri (120 km), the upstream limit of our terrain, and the other in Mali, from Koulikoro to Ségou (160 km), its downstream limit (). In order to analyse the different seine fishing practices and to understand the corresponding forms of village authority, exhaustive field work was carried out, allowing direct observation of fishing practices in 82 fishing villages and semi-structured interviews with the customary authorities of the 32 villages with water control in Guinea and Mali. Although the physical, cultural, social and political contexts are obviously not the same, the existence of fishermen-entrepreneurs, owners of large seines – the joba – in Mali and of smaller size in Guinea – the jolé – is the result of similar processes concerning their economic organisation and their exploitation of the river environment.

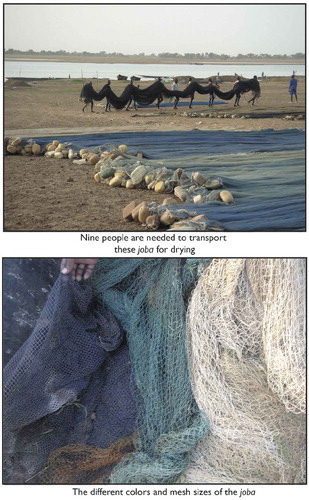

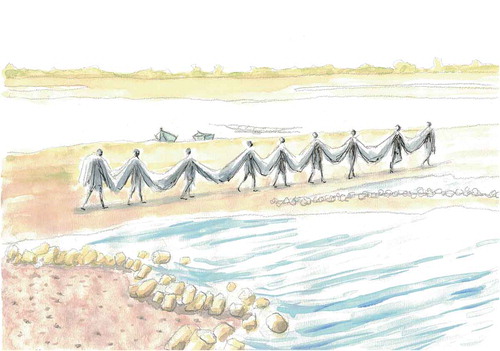

The joba, also called babélé in the Ségou region, are the largest seines that can be seen on the river. They consist of a gillnet piece with a maximum height of ten metres and can be several hundred metres, or even up to one kilometre long. Two ropes run along the top and bottom of the net, to which large floats and large weights are attached respectively. Handling them on land is difficult and requires about ten people (). Their colour varies between blue and green, chosen because, according to the fishermen, they are less detectable by the fish, but also for aesthetic reasons.

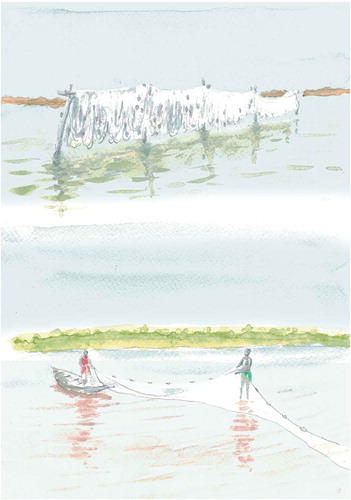

The jolé or joni, are nylon seines of shorter length than the joba, from 100 to 200 metres, but used in the same way. The big difference lies in the smaller number of men needed to handle them: between five and seven fishermen. Due to their much more affordable price and the simpler organisation for their use, the jolé has gradually replaced the joba () in some parts of the river. The lighter weight and smaller dimensions make it possible to set and then haul the net in the direction of the river, with both parts of the net then being pulled from sandbanks. Groups working with this net can thus use it two to four times in the same day. Where the price of a joba requires the pooling of financial resources through village associations or cooperatives, a jolé is often owned by a single person.

These seines are used after a biological rest period, also called ton-ing. These periods correspond to the prohibition of any fishing activity on a section of river bordering deep water areas in order to allow fish to gather and rest there. The success of collective fishing depends on how well these rest periods are maintained. As suggested by E. Baumann (Citation1995), these collective fishing practices not only increase the biomass and facilitate access to the resource thanks to rest periods, but also enable ‘fishermen to reaffirm their identity and strengthen social ties’ (p. 231).

3. The seine, the ‘factory’ of the somonos

3.1. Evolution and organisation of seine fishing systems in Guinea

From joba to jolé, transition from a collective enterprise to a family-run capital-intensive business in the area

The origins of the Somono fishermen settled in the villages along the Niger in the Guinean section are broadly identical. Their Bozo ancestors came from Mali – from the regions of Ségou and Kati – and carried out fishing activities in villages mainly composed of Malinké farmers. The low-water season corresponds to a period of strong migration mainly directed towards the National Park of the Upper Niger – located upstream from Kouroussa over an area of more than 6,000 km2 – where regulated no-take zone create areas full of fish (Saïdou & Djellouli, Citation2011). Seasonal migrations within Haute-Guinée are mainly for jolé fishing organised by the families who own this type of net, which requires many hands for its use.

The joba, shared between several villages, were used on this river section 40 to 50 years ago. At that time, the large seine boat belonged to several villages, whose mutual agreement made it possible to set up various no-take zones and their surveillance, to organise collective fishing, and to redistribute the catches as fairly as possible. These collective fisheries took place from upstream to downstream, in successive biological rest periods under the water control of the villages belonging to one of these union (the term most often used by fishermen to describe these systems). Between the villages of Babila and Kéniéba Koura, we were able to record the existence in the past of three separate village unions which practised this collective fishing with one or two joba ().

Figure 4. Diagram of the former joba fishing unions on the Niger upstream of Siguiri at the confluence with the Niandan River

The only joba still in operation on this Guinean section is in Kéniéba Koura, an important fishing village with 48 pirogues. It shows how difficult it is to implement such a large net in the river, whereas fishing families prefer to invest when they can afford it in smaller seines. Fodémoudou Condé, a dignitary from the village of Kobané, says that this joba fishing has stopped ‘because of the bad understanding’ between the villages, adding that ‘there is no longer any union’. Mamady Camara, customary chief of the village of Dougoura said that ‘with the arrival of nylon and hooks, everyone has equipped themselves’ thus abandoning a collective practice that is too restrictive. Finally, Massiramouran Camara, a Somono fisherman from Noukounkan, states, concerning these former joba fisheries, states ‘the children did not agree to work with this. The children prefer to go on adventures like in Liberia or Côte d’Ivoire’. These few testimonies, unanimously repeated in all the villages concerned, bring together the three reasons for abandoning this practice:

The associations are calling for social mechanisms for agreements and consultations, the sustainability of which can only be guaranteed through recurrent negotiations between the customary authorities. These exchanges concern both the spatial and temporal implications (fishing grounds, choice of dates and duration of enclosed areas), the technical obligations (distribution between seine villages, surveillance, people involved, etc.) as well as daily relations (market, marriage, cousins, etc.) which unite these villages. The maintenance of these social contracts was still the business of the previous generation of today’s active fishermen, but they no longer have the will or a favourable social framework to ensure their sustainability.

Joba fisheries were important periods in the fishing season for the young workers, both for their economic and social aspects. The gradual cessation of these collective practices encouraged young fishermen to leave for neighbouring countries on an ‘adventure’ basis and thus accentuated the abandonment of these seine fishing practices. As the social and financial capital necessary for their life course is no longer built up locally, many of them are encouraged to look for it abroad. Thus, according to the testimonies of not only customary dignitaries but also of active fishermen, the available manpower needed to set the biological rest periods and monitor them as well as to deploy the joba would no longer be sufficient.

Finally, the progressive arrival of nylon netting from the 1950s (Paugy et al., Citation2015) made it possible to manufacture seines at lower cost but made them less resistant than joba rope netting. This innovation led to the reduction of the size of the seines to make them easier to use. Where villages had to join together to buy and maintain a joba worth several tens of millions of Guinean francs, i.e. between 1 and 2.5 million FCFA, the jolé became accessible to families with sufficient savings of their own.

The arrival of the jolé thus changed the social and economic configurations of the fishing systems on this river section in Guinea. There was a shift from collective seine fishing based on efficient social and economic organisation between several villages to collective family seine fishing, following an exclusively private economic and social pattern.

Economic functioning of a family owning jolé

In order to understand the economic as well as the social interest of these seines, we will detail the classical system of distribution of the income from the property of a jolé, in this case that of Sékou Camara, a fisherman from the village of Dougoura. The fishing season lasts, depending on the hydrological conditions, between two and three months spread between March and May; the arrival of the flood marks the end of this practice because of the excessively strong currents. The jolé does not remain inactive while waiting for this period, but it ‘goes on a trip’ out of Dougoura’s aquatic territory in different tributaries – Milo, Niandan, Mafou, Sankarani, Dion – from January until March when it returns to the Niger.

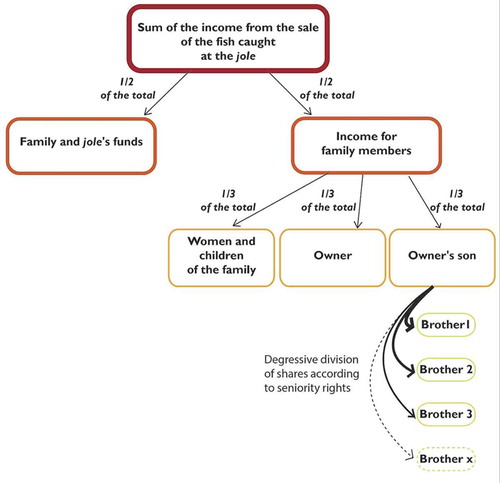

The money from the sale of the fish caught with the jolé is divided in two. One part is divided among the family members and the second part is destined for a specific family fund. The money thus accumulated is used to pay for the cost of repairing the net, but also acts as a reserve for other family expenses: health costs, wedding, motorbike, etc. These family expenses are financed from the reserves on an interest-free credit or even donation basis, with the approval of the head of the family and in consultation with the other members of the family. According to Sékou Camara, this system of cash to finance social expenditure ‘can only work within the same family’ – in contrast to a village-wide application. The money is distributed among the members once a year at the beginning of the rainy season. At this family meeting, an account of the past fishing year is taken and investment decisions for the coming year are then made. The share intended for the remuneration of family members is itself divided into three equal parts: one third goes to the women for themselves and the young children, one third to the owner and one third to the owner’s sons. The sum for the sonsFootnote3 is distributed degressively from the eldest son onwards – the difference in income between two brothers being the same between the first and the second, as between the second and the third, etc. (). This principle of seniority applies even if one of the younger brothers invests in his own jolé, ‘the money is for the older brother, obligatorily’ according to Sékou Camara, and is therefore distributed in the same way.

Words from employees

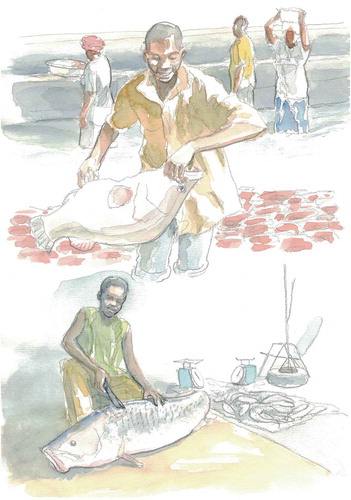

In case of lack of available labour within their own families, the owners of jolé resort to hiring Somono employees during a fishing season for a period of 4 to 5 months. The term ‘employee’ is used by both the jolé owners and the fishermen themselves, either in French, Malinké or Bamanankan – Baarkela. Half of the income goes to the owner of the net, the second half is then divided equally according to the number of employees according to two remuneration systems. At the beginning of the fishing season they make an agreement with the employer to be paid either at the end of the fishing season in one lump sum or after each day of fishing. In the first case the remuneration is monetary, while in the second case it can also be paid by a levy on the fish caught on the same day, which each employee resells on his or her own account. The advantages and disadvantages of these two types of remuneration are numerous. In the case of the single payment, there is no tedious operation of allocating the catch by dividing the pile of fish in two – one for the owner’s family, the other for the employees – and then making as many piles of fish as there are employees, ensuring an equal distribution according to the type and weight of the specimens according to their market value. But the timing of the one-time payment can be a source of tension, as the amount of the cumulative earnings during the low-flow fishing season minus the expenses for food and net maintenance is known only to the owner. In the daily payment system, the main disadvantage is the distribution and marketing of the fish. However, fishermen generally prefer this payment solution because they can negotiate the share of fish based on the day’s catch (). Wage differentials between the two systems can be very large. Mamady Camara, a Somono fisherman from the village of Noura, is employed every year by a family that owns a jolé. His pay is daily, ‘they give me three big fish, three captains’, and is fed by the family. But he explains that this family system of jolé fishing is, according to him, unequal: ‘It allows them to earn money all year round. With jolé, they earn much more than the others! What’s more, the money saved by the jolé owners allows them to buy more and more new nets. They are always richer!’.

3.2. The net of discord: the dominant situation of river seine fishing practices in Mali

The joba: the net of discord

In Mali, these fisheries are on a completely different scale due to the use of much larger seines with smaller joba-type mesh sizes. They take place for about 4 to 5 months between March and June – the arrival of the flood marking the end of their period of use. ‘This is the Somono factory’, and ‘the owner of the joba is the CEO, the director’ say Souleymane Diarra and Bakary Diarra, fishermen from the village of Tamani, respectively, to illustrate the yield of these large nets.

There are two types of properties that apply to these joba. In the first case, the armament, i.e. the ownership and operation of a seine, belongs to a private person and his family. This is the case in the village of Tamani, where there are 10 joba for as many owners, a unique case in Upper Niger. The joba are either inherited or recently bought from networks of urban traders in Bamako, Ségou or Mopti – some buyers turning to second-hand and therefore cheaper seines from the inland delta. The money brought in by the joba is given back to the head of the family, who is in charge of taking care of all the family’s expenses. There is no share reserved for the sons of the family as is the case with the jolé system in Guinea: no redistribution system has been mentioned, but the money from the seine is used to cover the needs for food and other family expenses – schooling, motorbikes, radio, clothes, weddings, etc. – and to cover the costs of the family. The operation of these ‘factories’ requires the hiring of many employees, ‘young people, old people, people who come with their children’ according to Mamadou Kanta, a fisherman in Tamani. Contracts for the day, week, month and fishing season are signed between them and the owners. They are paid either with money or by receiving a share of the daily catch, one or two big fish taken from the day’s catch. The second case is that where a seine net is no longer owned by a private person but by a cooperative. In Koulikoro, for example, the ‘Société Coopérative des pêcheurs de kangeFootnote4 kurun’, a cooperative society of about 40 members, is in charge of ‘promoting fishing production by training and equipping fishermen, as well as promoting the processing and marketing of fish products’ according to one of the Souleymane Kané officials. The distribution of catches also follows a precise system: catches are divided into three: one part is taken for the maintenance of the net, the pirogue and the engine, another part for the oldest fisherman who benefits from a privileged status and finally an equal distribution of the rest among the other cooperative fishermen.

Withdrawal of fishing practices in the fala and trials: the impacts of joba on aquatic territories

The implementation of these joba, a veritable industrial migrant fishing unit during the peak fishing season, has many repercussions on fishing practices and fishing grounds and therefore on the geography of the water controls on the Niger River. The first observation is that of the withdrawal of fishermen who do not own seines into the numerous secondary arms of the river in this section, the fala. If they offer privileged natural places in relation to the main course for the organisation of no-take zones – little sand, deep, sheltered under vegetation, no or little river traffic, etc. – then these are not the only places to be protected. Nevertheless, fishermen are kept away from the main course of the river by the local authorities, who forbid them to organise no-take zones. Indeed, the agents in charge of the fishing sector (local fishing service and the prefecture) only very rarely validate the biological rest period (ton) in the river to prevent possible conflicts between seine fishermen and others. They also justify this decision in order to limit the hindrance to traffic on the river caused by crossing driftnets. The second observation is that the local and customary regulations of the aquatic territories where the seine fishermen come to fish cyclically are not respected. Exploiting the territory as much as possible with nets set with motorised canoes for 2 to 3 days before leaving, no system of taxation or resource sharing is applied to villages with water control. The solutions most often considered by the fishing councils and the Local Fishing Service agents are to divide up the fishing periods: the day is devoted to joba fishing and the night is spent fishing with through nets. However, this solution of successive sharing of the aquatic space does not satisfy the host villages, which feel aggrieved not to receive a real share of the catch or monetary compensation. Finally, the third observation that results from this is the multiplication of conflicts that can lead to lawsuits between customary leaders belonging to the same customary authority on the river and joba owners.

4. Discussion and conclusion

The technical specificities of fishing are witnesses of social action; it reveals the issues inherent in the use of the instruments within its remit (Akrich, Citation2010; Cresswell, Citation2003; Mauss & Schlanger, Citation2012). Seine fishing seasons is well associated with the notions of rhythm, which André Leroi-Gourhan describes as ‘creators of space and time’ (Leroi-Gourhan, Citation1964, p. 135). The rhythm of the use of a trapping instrument, either fixed or mobile, in one or more places (as during a fishing campaign for example), and either individually or collectively, are all technical cadences that contribute to the formation of social time. The different fishing practices using the jolé and joba seine nets are important technical indicators of the degree of cohesion and consultation between fishing villages in the same region. Indeed, the study of their practices and the places where they are practised inform us of the state of the authority of the water Master. In Guinea, the progressive abandonment over two generations of the practice of joba in favour of jolé can be explained in part by the difficulty of maintaining a social contract between several villages responsible for two factors. First, ensuring the development of aquatic territories by organising the no-take zone and collective fishing which can involve more than a hundred participants. Secondly, ensuring the sustainability of an economic system dependent in particular on the costly maintenance of a large net. A village economic model ensuring an equal distribution of aquatic space and fish resources among individuals, but in necessarily limited proportions, has been replaced by an entrepreneurial system of private seine fishing, which ensures the enrichment of its owner and his family members.

If this system does occur without causing conflicts between fishermen who own seine boats and those who do not, it nevertheless tends to impose itself on the river section upstream of Siguiri thanks to two hypotheses that we formulate here:

The employees in these ‘factories’, who are all families, either from the village where the jolé is located or from surrounding villages, receive a relatively large and secure income from this activity. They can supplement this salary by laying their crossing nets themselves at the end of the daytime fishing hours of the jolé. This seasonal work concerns a large number of fishermen throughout this river section who thus see an interest in the sustainability of this system.

The customary authorities normally in charge of the balance between access to aquatic space and technical levelling between fishermen do not seem to be opposed to this type of practice – and for good reason, as many families with a water mastery also own jolé.

In Mali, large joba seines have not disappeared and are on the contrary widespread between Koulikoro and Ségou: their economic model is based either on a fishermens cooperative or on family reunification. Similarly, the intense seine fishing activity downstream of the Markala reservoir and more sporadically in the inland delta, coupled with a network of specialised dealers operating between Bamako, Ségou and Mopti, makes it possible to obtain fishing equipment at lower cost and thus lower management costs compared to the Guinean situation. The weight, both technical (a net of several hundred metres long handled by groups of up to thirty people) and economic (sometimes several million CFA francs in profits generated by the sale of the large quantities fished) seems to weigh on the entire customary system and water control in the aquatic territories concerned.

Does this mean that this liberal economic approach based on the private exploitation of aquatic environments and fish resources confirms the ‘tragedy of the commons’ thesis of Garett Hardin or announced earlier by classical economists such as Gordon (Citation1953, Citation1954) to lead to a situation of waste of these natural resources? Clearly not, although the process of communing aquatic territories is nowadays disrupted by these new fishing practices. On the one hand, the fishermen are bound by fine physical, technical, biological and political regulatory devices mechanisms. Seine fishing migrations only last during the dry season. As soon as the flood arrives, the flow becomes too strong to pull the joba into the river, which reduces the fishing pressure. Moreover, the fala, arms of the river not affected by seine fishing, act as refuge areas for fish during low water and therefore as fall-back territories for other fishermen, who are pushed back from the main bed. On the other hand, the bundle of law (Schlager & Elinor, Citation1992), provides an understanding of the adaptation strategies of regulatory systems. If the authority of the customary leaders is questioned by the forced passage of seine contractors and, more generally, if water mastery is no longer respected, the fishing communities turn to the technical services (the Local Fishing Service), the political services (the Prefect) but also the judicial services (the courts) to try to resolve these conflictual situations due to exploitation considered abusive of the environment.

It is therefore necessary to look more closely at the adaptation capacities of local communities (Cormier-Salem, Citation2000; McCay & Acheson, Citation1996; Ostrom et al., Citation1994), by integrating these new collective migratory processes that are transforming the geography of riverine aquatic territories.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kévin de la Croix

Kévin de la Croix is a Geographer at the University of Paris-Nanterre. He has done his PhD on the Niger fisheries.

Notes

1. The function of water control, jiituya, exercised by the ‘master of the waters’ (jitigi in Bamanankan or jiti in Mandenka), rests on a foundation that is both religious and temporal. It presupposes a pact between him and the deities of the river, as well as an agreement with the sovereign political authorities. The prerogatives of the jitigui extend to all the water spaces that make up its territory: the river arms and channels. In a given space, the relationship between technological imagination, period of the cycle and territoriality is left to the full responsibility and authority of the water master.

2. Mali, and more broadly the Sahelian region, has been in armed conflict since 2012 against pro-independence jihadist groups in a context of Tuareg rebellion against the Bamako government.

3. Sékou Camara has 3 sons working with him: Ladji Camara, Kanyamari Camara and Famady Camara.

4. The term kange refers to a large pirogue designed to transport people or heavy loads, often referred to as a pinasse in French.

References

- Akrich, M. (2010). Comment décrire les objets techniques?. Techniques & Culture, 54–55, 205–219. https://doi.org/10.4000/tc.4999

- Baumann, E. (1995). A chacun son bas de laine : le comportement d’épargne en milieu pêcheur du delta central au Niger (Mali). Cahiers Finance Ethique Confiance, 201–230.

- Béné, C. (2003, juin). When fishery rhymes with poverty: A first step beyond the old paradigm on poverty in small-scale fisheries. World Development, 31(6), 949–975. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00045-7

- Binet, T., Failler, P., Bailleux, R., & Turmine, V. (2013). Des migrations de pêcheurs de plus en plus conflictuelles en Afrique de l’Ouest. Revue Africaine des Affaires Maritimes et des Transports, 5, 51–68.

- Bonnemaison, J. (1981). Voyage autour du territoire. L’Espace géographique, 10(4), 249–262. https://doi.org/10.3406/spgeo.1981.3673

- Bouju, S. (2000). Activité de pêche et instrumentalisation des identités: pêcheurs migrants et pêcheurs nationaux dans la société guinéenne. In M. -J. Jolivet, (Ed.), Les pêches piroguières en Afrique de l’Ouest: dynamiques institutionnelles--pouvoirs, mobilités, marchés (pp. 247–280). KARTHALA Editions.

- Conrad, D. C., Bayo, L., & Camara, S. (2002). Somono Bala of the Upper Niger: River People, Charismatic Bards, and Mischievous Music in a West African Culture. African Sources for African History, v. 1. Brill.

- Cormier-Salem, C. (2000). Appropriation des ressources, enjeu foncier et espace halieutique sur le littoral ouest-africain. In J.-P. Chauveau, E. Jul-Larsen, & C. Chaboud, (Eds.), Les pêches piroguières en Afrique de l’Ouest: dynamiques institutionnelles--pouvoirs, mobilités, marchés (pp. 205–229). Collection “Hommes et sociétés”. IRD; CMI.

- Cresswell, R. (2003). Geste technique, fait social total. Le technique est-il dans le social ou face à lui?. Techniques Culture, 40(1), 8.

- Croix (de la), K., Dao, A., Ferry, L., Landy, F., Muther, N., & Martin, D. (2013). Les systèmes de pêches collectives fluviales somono dans le Manden (Mali) : un révélateur territorial et social unique en sursis sur le Niger supérieur. Dynamiques Environnementales - Journal international des géosciences et de l’environnement, 32, 125–143.

- Croix (de la), K., Ferry, L., Landy, F., Traoré, B., Muther, N., Tangara, B., & Martin, D. (2013, juillet 24). Quelle place pour des pêcheurs urbains? Le cas de Bamako (Mali) Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography, 4(164), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.4000/cybergeo.25977

- Droy, I., & Morand, P. (2013). Les grands aménagements sur le fleuve Niger : atout pour le Mali ou facteur de vulnérabilité pour ses populations rurales?. Mondes en developpement, 164(4), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.3917/med.164.0057

- Failler, P., Binet, T., Agossah, M., Meidinger, A., Turmine, V., & Bailleux, R. (2020). La pêche migrante ouest-africaine : un secteur refuge à bout de souffle. In M. Veronica, & K. Croix, (Eds.), Ecologie politique de la pêche: temporalités, crises, résistances et résiliences dans le monde de la pêche (pp. 85–108). Presses universitaires de Paris Nanterre.

- Fay, C. (1989a). Sacrifices, prix du sang, “eau du maître” : fondation des territoires de pêche dans le delta central du Niger (Mali). Édité par François Verdeaux. Cahiers des Sciences Humaines, 25(1–2), 159–176.

- Fay, C. (1989b). Systèmes halieutiques et espaces de pouvoirs : transformation des droits et des pratiques de pêche dans le delta central du Niger (Mali), 1920-1980. Édité par François Verdeaux. Cahiers des Sciences Humaines, 25(1–2), 213–236.

- Ferry, L., Muther, N., Coulibaly, N., Martin, D., Mietton, M., Coulibaly, Y. C., Olivry, J.-C., Paturel, J.-E., & Barry, N. (2012). Le fleuve Niger de la forêt tropicale guinéenne au désert saharien : les grands traits des régimes hydrologiques. IRD. http://www.documentation.ird.fr/hor/fdi:010059664

- Fossi, S., Barbier, B., Brou, Y. T., Kodio, A., & Mahé, G. (2012, juillet 1). Perception sociale de la crue et réponse des pêcheurs à la baisse de l’inondation des plaines dans le Delta Intérieur du Niger, Mali. Territoire en mouvement, 14-15, 55–72. https://doi.org/10.4000/tem.1739

- Gordon, H. S. (1953, juillet). An Economic Approach to the Optimum Utilization of Fishery Resources. Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, 10(7), 442–457. https://doi.org/10.1139/f53-026

- Gordon, H. S. (1954, avril). The economic theory of a common-property resource: the fishery. Journal of Political Economy, 62(2), 124–142. https://doi.org/10.1086/257497

- IOM. 2013. La crise au Mali sous l’angle de la migration. https://www.iom.int/files/live/sites/iom/files/What-We-Do/docs/Mal_Migration_Crisis_June%202013_FR.pdf .

- Jul-Larsen, E., & Kassibo, B. (2001). Fishing at home and abroad: Access to waters in Niger’s central delta and the effects of work migration. In Benjaminsen and C Lund (Ed.), Politics, Property and Production in the West Africa n Sahel Understanding Natural Resources Management (pp. 208–232). Nordic Africa Institute.

- Kassibo, B. (1994). Histoire du peuplement humain. In La pêche dans le delta central du Niger : approche pluridisciplinaire d’un système de production halieutique (pp. 81–98). Karthala, Paris.

- Laë, R. (1992, avril). Influence de l’hydrologie sur l’évolution des pêcheries du delta central du Niger, de 1966 à 1989. Aquatic Living Resources, 5(2), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1051/alr:1992012

- Landy, F. (2010). Circulation et territoire: freins, frictions et affinités. In V. Dupont, & F. Landy, (Eds.), Circulation et territoire dans le monde indien contemporain (pp. 311–334). EHESS.

- Leroi-Gourhan, A. (1964). Le geste et la parole. 1: technique et langage. Repr. Sciences d’aujourd’hui. Albin Michel.

- Magrin, G. (2013). Voyage en Afrique rentière: une lecture géographique des trajectoires du développement. Territoires en mouvements. Publications de la Sorbonne.

- Marie, J., Morand, P., & N’Djim, H. ( Ed). (2014). Avenir du fleuve Niger. Expertise collégiale. IRD Éditions. http://books.openedition.org/irdeditions/5173

- Mauss, M., & Schlanger, N. (2012). Techniques, technologie et civilisation. Quadrige Série Mauss 8. Presses Univ. de France.

- McCay, B. J., & Acheson, J. M. ( Ed). (1996). The question of the commons: The culture and ecology of communal resources (3rd print ed.) Arizona Studies in Human Ecology. Univ. of Arizona Press.

- Morand, P., Kodio, A., Andrew, N., Sinaba, F., Lemoalle, J., & Béné, C. (2012, décembre 1). Vulnerability and adaptation of African rural populations to hydro-climate change: experience from fishing communities in the inner Niger Delta (Mali). Climatic Change, 115(3), 463–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-012-0492-7

- Ostrom, E., Gardner, R., & Walker, J. (1994). Rules, games, and common-pool resources. University of Michigan Press.

- Paugy, D., Levêque, C., Mouas, I., & Lavoué, S. (2015). Poissons d’Afrique et peuples de l’eau. IRD Éditions. http://books.openedition.org/irdeditions/8336

- Saïdou, D. M., & Djellouli, Y. (2011, mai 9). La gestion dérogatoire : une stratégie associant péniblement l’État et les communautés locales dans le Parc National du Haut Niger (Guinée). VertigO, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.4000/vertigo.10763

- Schlager, E., & Elinor, O. (1992). Property-rights regimes and natural resources: a conceptual analysis. Land Econo-mics, 68(3), 249–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/3146375

- Togola, S. (2009, mai). Les pêcheurs du lac de Sélingué: trajectoires et itinéraires de migration. Hommes & migrations, 1279(1279), 24–37. https://doi.org/10.4000/hommesmigrations.290

- UEMOA. (2013). Atlas UEMOA de la pêche continentale. http://sirs.agrocampus-ouest.fr/atlas_uemoa .

- Zwarts, L. (2005). Le Niger, une artère vivante: gestion efficace de l’eau dans le Bassin du Haut Niger. RIZA - Rijkswaterstaat.