Abstract

This paper studies the ways in which field researchers engage in videoing mobile activities in a collaborative fashion. Rooted in ethnomethodology and conversation analysis, this study documents video data collecting practices of social activities, and reflects on their methodological and analytical relevancies. We demonstrate that camerapersons coordinate themselves and their cameras views, while constantly adjusting to the emergent details in the video-recorded social activities. While collaboratively videoing mobile activities, camerapersons engage in the practical work of producing complementary views, capturing the scene in a relevant way, and avoiding the presence of one another in their views. Our analysis shows that camerapersons frame the target events, exploiting the features of the camera optics and categorizing what belongs to the center and the margins of their camera views. <Collaboratively videoing involves the coordination between recorded and recording activities, which reflexively elaborate upon each other.

1. Introduction

Film and video data have constituted important advances in the methodology of the social sciences, beginning with visual anthropology and ethnographic film (Banks and Ruby Citation2011; Ruby Citation2000), but then also within visual sociology (Harper Citation2012; Knoblauch et al. Citation2006), and video-based geographic research (Garrett Citation2011). Film and video are not only used across disciplines but also within different epistemological sensibilities, especially more recently in non-representational, more-than-visual, sensorial research (Pink Citation2009; Vannini Citation2015). These approaches have produced a renewed interest in the body, within a diversity of video methods, going from interviews to video diaries, and naturalistic recordings. In this paper, we focus on the latter, prized by ethnomethodology and conversation analysis (EMCA). Since its inception as a field, EMCA has extensively used recording technologies for documenting social activities in a naturalistic way as they happen. Audio, film and later video recordings have always been key for investigating how talk, the body and the material environment are indissociable, how embodied resources feature in intersubjectively produced and recognized social actions, and how the situatedness of social interaction is embedded in local ecologies (Cekaite and Mondada Citation2020; Deppermann and Streeck Citation2018; Goodwin Citation1981; Haddington, Mondada, and Nevile Citation2013; Heath Citation1986; Nevile et al. Citation2014; Streeck, Goodwin, and LeBaron Citation2011). In this sense, EMCA contributes in a central way to the development of video studies in the social sciences.

Disciplinary, theoretical, analytical perspectives produce distinctive video data, coherent with their conceptual and methodological requirements. For instance, video data generated by EMCA research are characterized by their interest in seen-but-unnoticed and only to be discovered but not imagined phenomena (Garfinkel Citation1967; Sacks Citation1984). Video data in EMCA research documents social interaction by giving special attention to the participation framework characterizing the recorded events, as well as the continuous temporality of the unfolding actions, the multimodal resources – that is, talk, gaze, gesture, body posture, and movements – mobilized by the participants to build the accountability of their actions, and the relevant features of the material and spatial environment of these actions (Heath, Hindmarsh, and Luff Citation2010; Mondada Citation2012). According to these analytical and conceptual principles, video practices in EMCA have been developing in a variety of ways, using one or more cameras (Mondada Citation2012, Citation2014), and other video recording devices (McIlvenny Citation2019, Citation2020).

The use of video for documenting the embodied details of social actions has sparked an interest in video practices themselves. This interest has generated a rich methodological literature in numerous fields, instructing how to use video (Heath, Hindmarsh, and Luff Citation2010; Pink Citation2012; Vannini Citation2020). In this paper, we do not address methodological issues but rather we treat video as a topic of investigation in its own (Broth, Laurier, and Mondada Citation2014). This way to ‘turn the ‘optic’ around’ and ‘reflect upon audio-visual material to develop one’s sense of implication in how the research is conducted’ (Paterson and Glass Citation2020, 8–9), has been considered in diverse ways within different approaches of video. In terms of reflexivity and positionality, it has generated insights about the experience of the researcher, and the situatedness of knowledge in relation to both power and place (Paterson and Glass Citation2020; Rose Citation1997), mainly in the form of introspective reflections about fieldwork. It has also generated video experiments in participatory films (for early proposals, see Rouch Citation1974; Worth and Adair Citation1972) as well as in explorations of sensuous aspects escaping traditional visual representations (Merchant Citation2011; Sikand Citation2015). This paper explores a third avenue for this conceptual switch from video methods to video as an object of study, by centering its analytical focus on the actions of the camerapersons, considering videoing as a powerful sense-making and categorizing practice that can be documented and subjected to analytical scrutiny (see Mondada Citation2003, Citation2006, Citation2014).

The originality of this approach consists in analyzing video practices as other social practices, focusing on embodied situated actions, submitted to multimodal analysis, that is, the detailed analysis of the intertwining of talk, gesture, head movements, and body postures and movements in space (Goodwin Citation2018; Mondada Citation2014, Citation2018; Streeck, Goodwin, and LeBaron Citation2011). For doing so, the paper elaborates on previous work, investigating the embodied production of video shootings for EMCA research, and identifying a variety of situated micro-practices whereby a cameraperson in a mobile setting adjusts to participants’ visible social actions and projections of next actions (Mondada Citation2014). These methodically deployed embodied movements of the cameraperson include projecting and following participants’ walking and stopping, manipulating the camera and adopting a particular perspective, identifying and capturing the relevant participation framework(s), and so on: ‘[t]he cameraperson orients to the embodied movements of the participants, to the structure of their activity, and to the sequential organization of their talk and action’ (Mondada Citation2014, 57). Inspired by Macbeth (Citation1999), this analysis considers camerawork ‘as a form of embodied proto-analysis’ (2014: 58), that is, as an immediate and contingent form of professional vision (Goodwin Citation1994) exerted in situ on filmed actions, demonstrating not only how it is practically accomplished but also the fundamental features it reveals about the social and sequential organization of interaction.

Turning video practices into a topic of analysis — rather than just a methodological issue — responds to a double interest: on the one hand, it fuels, within a form of social studies of science and studies of work, an interest in how social researchers produce their empirical data (Garfinkel Citation2022; Lynch Citation1993; Lynch and Woolgar Citation1990); on the other hand, it motivates an interest in how video practices actively establish the intelligibility of the phenomena studied. Ultimately, the original focus of this approach consists not only in showing how recording practices work, but also in revealing how recorded practices are seen and reflexively shaped by the researchers videoing them (in the sense of reflexivity inspired by Garfinkel Citation1967 rather than an introspective reflexivity).

This paper aims at furthering the interest in video practices, by considering them not as individual actions, but as team practices, investigating the coordination of camerapersons and their camera shots. In so doing, it reveals features of team collaboration in social research, as well as how, in a situated manner, camerapersons frame their object of study and coordinatedly adjust to the local contingencies and the emerging features of the social activities they document. The focus on mobile camerapersons videoing mobile participants, enables to document how camerapersons deal with practical problems such as how to adapt to the mobility of the participants and their transitions from one phase of the activity to another, how to document both the participants and the detail of the artefacts they use, and how to follow participants within complex material ecologies. This makes possible an analysis of the local solutions found by the camerapersons producing complementary views, framing the scene in a relevant way, and avoiding the presence of the other cameraperson in the frame. As we shall see below, the study of videoing enables and supports a better understanding of both the scientific recording practices and the recorded practices to be analyzed.

2. Data: The Mobile Activities Studied, and the Challenges Of Videoing

This paper focuses on mobile activities filmed with handheld cameras operated by a team of camerapersons. These activities make coordinated and collaborative camera work particularly observable, as well as the problems faced by the camerapersons and the practical solutions they find in situ. By contrast with video recording with fixed cameras, where the field researchers have to make decisions - choosing the position, orientation, and frame of camera shot - before the recorded events happen, videoing with mobile cameras rather implies the camerapersons closely following the recorded events as they happen. Mobility further highlights the work of videoing as embodied work with a camera, in which the cameraperson looks through the camera while monitoring what happens on the field, holding and manipulating the camera and moving with the camera. This motivates our choice to focus on mobile camerawork and describe its subtleties.

The analyses rely on the views produced by the camerapersons as well as, in some cases, on a ‘meta-camera’ (see Mondada Citation2014) documenting the work of the camerapersons. The first type of evidence enables us to indirectly reconstruct the camera movements; the second type of evidence enables us to directly observe the embodied work of the camerapersons (for these distinctions, see Broth, Laurier, and Mondada Citation2014).

The data studied here come from three mobile activities. First, we concentrate on outdoor family photography sessions, on the basis of video recordings of photo shootings with professional photographers in the countryside. In order to record these activities, two mobile cameras, focusing on the photographer and the photographed party often facing one another, and one meta-camera, adopting a more comprehensive view of both the recorded photographing activities of participants and the recording activities of camerapersons, were used. Second, geocaching games, outdoor treasure hunting activities in which participants search for hidden objects in the environment with the help of technological devices such as GPS, were videoed by two mobile camerapersons. Third, construction work in a museum reassembling an art installation for an exhibition was documented by several cameras recording a team transporting, unpacking and reconstructing the pieces of a complex art installation. The selection of these activities for the analyses developed in this paper is grounded on the fact that they present instances of collaborative videoing of mobile activities in complex environments. These circumstances make the work of the camerapersons both challenging and observable, enabling us to turn this work from a methodological resource into an analytical topic (Zimmerman and Pollner Citation1970).

In these mobile activities, the camerapersons face various practical problems. As participants are mobile with sometimes unpredictable movement trajectories, the camerapersons need to position their cameras and adjust their angles adapting to the participants’ movements in order to produce an adequate framing of the activities. We focus here on teams engaged in collecting video data within a EMCA perspective: they orient to preserving the global participation framework in a continuous manner and to maximizing the continuous access to the relevant multimodal details of the unfolding actions. At the same time, they also orient to organizing the complementarity of their camera perspectives, avoiding redundant views, and the invisibility of the camerapersons on the recorded views. As the action within the global participation framework dynamically evolves, camerapersons establish, and re-establish, the coordination with one another. Thus, camerawork addresses and reveals a double set of contingencies: the activities of the participants, in their situatedness and emergence, and the mutual coordination of the videoing team, adjusting to them.

The analysis deals with these two orientations, and the relation between the recording and the recorded activities. We first focus (§3) on how camerapersons coordinate and orchestrate the complementarity of their views, both taking into consideration their relative positions and the spatial distribution of the recorded activities, and introduce a specific arrangement, the ‘V-formation’. Second (§4.1), we analyze the practices of camerapersons dealing with the practical problem of having the other cameraperson on their view, resolved by panning out and reframing the camera view. Third (§4.2), we investigate how the spatial disposition and other details of the local ecology are exploited by camerapersons both to enhance the focus on the details of the ongoing activity and to cover the other team member. In all the cases, the practical problems of the camerapersons are systematically related to relevant features of the changes in the recorded activities, which contribute to reveal them.

The analysis is based on multimodal transcriptions (see Appendix for transcription conventions) that consider the activities of the participants as well as the activities of the camerapersons. In particular, the annotations of the embodied details of both activities are integrated in the transcripts — in a symmetric treatment of the observers and the observed. Textual annotations are supplemented by screen-shots: the figures reproduced in the transcripts are either the full image captured by the video, showing how it was framed (§4.1) or part of the images filmed, which, in order to enhance their intelligibility, have been cropped in a way that is relevant for the focus of the analysis (§3 and §4.2). Moreover, in a number of cases, various views of the same instant are offered (labeled A/B/C), whereas in other cases only one view is considered.

Our analysis of videoing practices aims at describing the subtleties of camera work, revealing at the same time how these subtleties exhibit the organizational details of the activities documented. Recording and recorded activities reflexively elaborate upon each other and reveal their accountability.

3. Orchestrating and Coordinating Complementary Views

In outdoor activities, mobile camerapersons constantly adjust to the mobility of the participants in the recorded activity. Orienting to various constraints and possibilities, they find emergent solutions addressing local practical problems. Adjusting to the filmed events also generates practical issues for the camerapersons coordinating together. We discuss these issues on the basis of video recordings done by two mobile cameras of family photography sessions in the country side, further documented by a meta-camera. The participation framework of the photography session is characterized by two parties, the photographer and the photographed, facing each other at some distance. This participation framework might be relatively stable during the shooting, but is dynamically rearranged and reorganized at other moments, for instance, when the pose is orchestrated, or in the transition from one pose to the other. These transitions occasion some adjustments for the camerapersons who reposition themselves in coordination with one another.

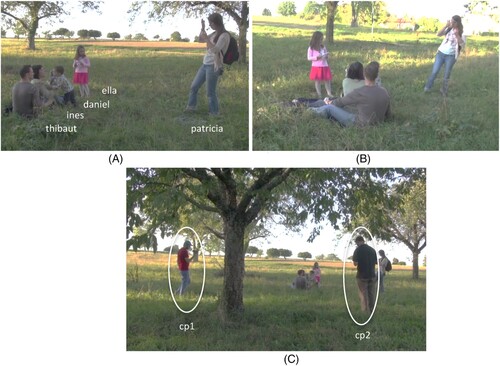

The issues faced are observable in the following extract: The photographer (Patricia) is instructing the family (Thibaut, Ines, Daniel and Ella) to sit on a blanket. The camerapersons are disposed around them, positioned perpendicularly, adopting a complementary view: one is more focused on the family (A, filmed by Cameraperson1), while the other focuses more on the photographer (B, filmed by Cameraperson2). These two possible complementary views on the participation framework are captured by the meta-camera (C).

As the action unfolds, the arrangement of the pose is completed and Patricia takes a shooting position. The camerapersons orient to the relevance of a reorganization of their respective positions. This not only enables them to better configure the complementary of their views, but also to take into consideration an extra constraint, which is the visual angle of the photographer who directs her camera towards a portion of the landscape suitable for her picture and free of any other person. Cameraperson1 runs the risk of being on the camera of the photographer and consequently moves away, radically changing his position. He coordinates with Cameraperson2 in an explicit way, pointing towards the direction he is moving.

Extract 1 | PHO_BS_240916_001220

As Patricia arranges the positioning of Ella (1-7), both camerapersons have already established their bodily positions with respect to the recorded activity, complementarily arranging in a perpendicular way (C). While Ella gets her place in the pose, Cameraperson1 begins to gaze at Cameraperson2 (). As the arrangement of the pose continues, when Cameraperson2 looks towards Cameraperson1, and once they establish mutual gaze, Cameraperson1 points forward (), performing an explicit instructing gesture, while Patricia moves towards her shooting position. Both camerapersons begin to walk quickly (), and, still focusing their cameras on the recorded activity, they radically change their position. They move to the other side of the interactional space of the photo-shooting where they stabilize their positionings. The final arrangement not only avoids interfering with the view of the photographer, but also enables the camerapersons to adopt two complementary views (A), one focusing on the family (B), the other on the photographer (C).

This rearrangement of the camerapersons’ positions around the participants who are getting ready for the next shot reveals how they take into consideration both the constraints of the recorded scene and their mutual coordination. The camerapersons adopt complementary positions, respectively facing each of the parties in the recorded activity, documenting their embodied actions in the fullest way. Thus, the team members do not record from the same perspective, which would miss embodied details and result in redundant views; they do not face each other, which would result in each featuring on the other’s camera view; they rather adopt what we call a V-formation: a distribution that forms a V with respect to their focus. The V-formation, which can be narrower or wider depending on the circumstances, is a practical solution to the issues of adequately documenting the action while being both complementary and mutually invisible.

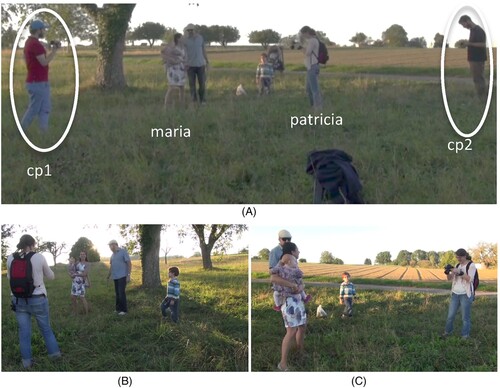

Likewise, the following example shows another transition from one shot to the next: the camerapersons change their position in a way that repristinates their V-formation. The photographer (Patricia) has snapped some photographs of mom (Maria) with her little daughter (Monica) in her arms, during which the camerapersons have positioned themselves in a way that affords complementary views (A, B and C). We join the action as Maria is moving away and the family is getting recomposed for the next shot:

Extract 2 | PHO_BS_240916_003925

As Patricia addresses Monica (1-2), Maria, together with other family members, begin to move (A). This prompts Cameraperson1 to step backward (). Then, Patricia, asking the family to stay where they are (9), walks towards her left to get a chair, used for shots from an elevated position (11). This prompts Cameraperson2 to step backward. As Patricia gets her chair, Cameraperson1 starts to walk forward (). This is noticed by Cameraperson2 who begins to walk forward, too (). Moving forward, both camerapersons position themselves in the other side of the interactional space of the photographing activity (A). When Patricia comes back with the chair and gets ready to shoot, both camerapersons stabilize their positions by re-establishing a new V-formation in which they record the target activity with complementary views (B and C).

In this case, the movement of the participants, dissolving and re-establishing the interactional space of the photo-shooting activity, is closely attended to by the camerapersons. As soon as the participants get in motion, the camerapersons respond to, stepping backward or forward, enlarging or narrowing their views. When one cameraperson initiates walking forward, projecting a change in their shooting direction, the other follows and walks forward (cf. extract 1 in which there is an instruction from one team member to the other). This is done at the precise moment at which the photographer is momentarily away from shooting to get her chair. As in the previous extract, both camerapersons manage to radically change their positions, moving to the other side of the interactional space, adjusting to what happens and projecting the next shot. While doing so, they still display an orientation to re-establish their V-formation with respect to both themselves and the recorded activity (A and A). This shows that the V-formation is flexibly sustained by the camerapersons, dynamically adjusting to the emerging bodily formations of participants in the recorded activity.

This section has shown that changes in the participation framework and transition moments in the recorded activity generate an adjustment of the camerapersons, and thus challenge their coordination and search for a new adequate position relatively to the scene. The practical solution is the adjustment of the positions and perspectives of camerapersons, still preserving or re-establishing their V-formation.

4. Organizing the Invisibility of the Camerapersons

The previous section has analyzed how the team achieves collaboratively their views on the recorded activity, orienting to and actively arranging their complementarity, adopting, and transforming, when necessary, a V-formation. The coordination problems they encounter, however, do not concern only their complementary (re)positioning around the videoed scene; they also concern their respective positions relative to the videoed image. In this respect, camerapersons do not only orient to documenting the scene in a relevant way; they also orient towards videoing it without any trace of the recording activity. This is observable in two camera movements we will describe in the next two sections: panning out the other cameraperson from the videoed view, and covering the other by adopting a perspective that uses a material object or a person to hide the other. We will ground these analyses on the recorded views.

4.1. Panning out the Other Cameraperson

Video recording mobile participants walking in the environment raises challenges for the mobile camerapersons shadowing, following, and adjusting to them in the ways that anticipate their trajectories of action — in a configuration in which both the recorded scene and the recording image are moving. In this case, the camerapersons face a double problem of coordination that involves both maintaining their complementary views and avoiding to feature in the view of the other. This implies a constant monitoring of the participants’ mobile trajectories, the other cameraperson’s movements, and the image recorded, within a double look at the environment and at the camera monitor. The eventual presence of the other cameraperson on the image can be possibly inferred from their relative position within the environment, but can be certainly checked by looking at the recorded image. In this section, we focus on cases in which this monitoring reveals that the other cameraperson is momentarily visible on the footage from the camera, and the resulting practical solution adopted — panning the companion out from the image. This practice is visible in the margins of the image shot. In this section, for each screen-shot, we reproduce the entire framed image as it has been captured by the camera. Moreover, the screen-shots are annotated visually so to indicate visible camerapersons (white-lined shapes), and indicate the direction of ongoing micro-adjustments (horizontal arrows) of the cameras’ framings (delimited by black-lined rectangles).

The geocaching data show exemplary occurrences of mobility problems, since they involve participants walking around, either to search for hidden objects (extracts 3-4) or to hide objects to be found in a subsequent search (extract 5). Two camerapersons follow them, orienting to the production of complementary views, such as one camera focusing on a detail of the cached object and the other on the participation framework, or one camera focusing the participants’ bodies and the other the global ecology of the scene.

In the next extract, two young visitors, Françoise and Gaston, are guided by Marc on a geocaching search for a hidden object. They find a wall with a plaque containing a set of letters that are to be converted into elements of a GPS coordinate. We join the action as Marc reads aloud the inscription on the plaque, prompting Gaston to write it down.

Extract 3 | GEO_STR_150215_E2_2036

As the participants read aloud the letters on the plaque (1-2), Marc prompts Gaston to write them down (3, ), and reaches for the GPS device being held by Françoise. Closely standing on the side of the participants, Cameraperson1 walks closer to them and repositions her camera view, ensuring the visibility of the three participants’ faces and gestures (A). But, in doing so, she becomes partially visible on the right margin of the view produced by Cameraperson2 (B), who stands at a distance behind the participants. While Cameraperson1 stands still, Cameraperson2 takes a step back and pans her camera to the left, excluding Cameraperson1 from appearing in her framed image while preserving the visibility of the three participants standing in front of the wall (B and B).

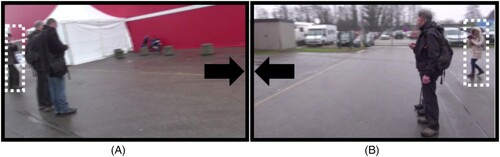

The next extract shows similar problems, related to the participants — Marc, a geocaching guide, and Guy, a young visitor — transiting from stopping and looking at their GPS to walking away. The camerapersons adopt complementary views on them: one from behind (cp1) and the other approaching aside (cp2), zooming on their instrument. When the participants project walking, the camerapersons adjust to their movement, but end up filming each other. The problem is, again, resolved by panning the other cameraperson out:

Extract 4 | GEO_FR_STR_150215_1913

After checking the GPS device on his hand (and referring to it, 1), Marc verbally locates the georeferenced spot as proximal (‘it is not far away’, 3) and, pointing with the chin in its direction, projects a shift towards walking there. Standing close to the participants and framing the participants’ embodied orientation to the GPS device Marc hands to Guy (), Cameraperson2 follows the participants as they prepare to walk away from their current position. He operates a series of microadjustments of his view, which increases the visibility of Marc and Guy’s faces and bodies as well as of the surrounding environment (B). In the midst of these microadjustments, Cameraperson2 becomes visible on Cameraperson1’s view (B) who then horizontally pans the camera to the right, repositioning his team companion out of the frame (B and B).

This extract further shows how emerging transformations in and of the interactional space occasion a series of adjustments by the camerapersons following the participants which, in turn, may result in the on-screen visibility of the recording activity. Providing a practical solution to this problem, panning out constitutes a skillful exploitation of the design features of handheld cameras, whose ergonomy facilitates the manual production of microadjustments of the camera’s position while looking at the external monitor, hence providing for the ad hoc positioning of visible elements within or beyond the edges of the camera view’s rectangular frame.

In the next extract, the videoing team follows two geocachers, Joël and Bob, walking. As they notice a place where to put a cache hint, they progressively slow down and end up stopping, looking and pointing at a barrack on their right. This occasions several practical problems for the camerapersons: they do not just adjust the speed of their walk to the filmed participants, but also one of them rearranges his position, through which his camera captures both the participants and the object they look at. For doing so, he moves around them, occasioning his inclusion in the other’s view.

We join the action as Joël and Bob stop walking and the latter checks his phone, occasioning the camerapersons’ further adjustment of their positions and camera views:

Extract 5 | GEO_STR_140215_2308

Whereas Cameraperson1 stands still and adjusts her camera view so to show the participants from the side, producing a clear view of their faces and bodies (A), Cameraperson2 begins to walk forward along participants’ left side, adjusting his camera’s view so that it shows the barrack on the participants’ right side (B) without getting in their way of visually inspecting it. As Cameraperson2 walks forward, Cameraperson1 begins to show on the right side of his view, and likewise he begins to show on the left side of hers. Cameraperson1 pans Cameraperson2 out of his camera view by aligning the right margin of his frame with Joel and Bob’s backs (A).

Reflexively adjusting to her counterpart, Cameraperson1 likewise begins to walk around the participants but in the opposite sense, i.e. backwards. While walking around Joël and Bob, the two camerapersons produce a series of reflexive micro-adjustments on their cameras’ views, slightly panning them against the direction where their counterpart is visible so that it no longer does (A/B and A/B). Joel and Bob continue to look at the barrack and prepare to take a photo of it. Positioned left to the participants and framing their side and the barrack, Cameraperson2 stops walking, aligning the right margin of his view close to the participants’ backs. At the same time, Cameraperson2 walks some more steps while panning Cameraperson1 out of her view, stopping once her colleague researcher is no longer visible, as her view shows the participants’ back and a clear image of the barrack (A/B).

To sum up, the extracts in this section show how camerapersons deal with the practical problems they face when the mobile participants they follow are walking and stopping, or the reverse. These transitions occasion movements of the camera that might include the other cameraperson in the view. By slightly panning the camera, camerapersons produce moment-by-moment micro-adjustments in the resulting camera view, maximizing the visibility of the recorded activity (two persons searching for a hidden object) and minimizing the visibility of the other cameraperson’s body (and hence of the recording activity) on their camera view. Thus, such work of framing bodies in or out of the camera angle reveals the categorizing activity of camerapersons, treating the visible bodies of participants and their ongoing actions as either belonging to the recorded activity, and calling for a maximal visibility given its importance for future analysis, or as belonging to the recording activity and hence as not only irrelevant but intrusive to the other activity and its optimal visibility.

4.2. Covering the Other Cameraperson

The moment-by-moment mutual adjustment of the camerapersons shows both the plasticity of their practices, and the systematicity of their orientations to possible emergent problems. It also shows how the camerapersons notice and treat their self and other positionings in similar ways, without needing to explicitly coordinate. These views adapt not only to the walking trajectories of the participants, but also to the local environment and its relevance for the ongoing action.

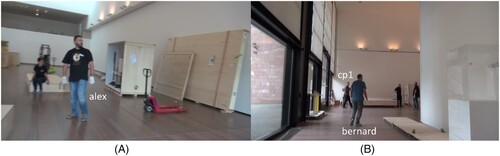

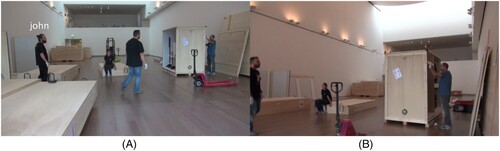

The next extract is taken from a construction work assembling an exhibition in a museum, for which a team of workers is taking art objects out of boxes to place them on the installation. Cameraperson1 is following Alex (A) in a room where various boxes are stored and emptied, under his management. Cameraperson2 is following Bernard, who is joining Alex, coming from another room. The extract begins as Bernard enters the room (B) and asks a question to Alex concerning the progression of his work, while approaching a box that has been opened but not yet emptied:

Extract 6a | BEN_day3_025235

Bernard’s arrival in the room is oriented to by Cameraperson1 who turns his head towards him (B) and begins to walk backwards towards the windows. This movement enables the Cameraperson1 to be minimally visible on the shot of Cameraperson2. Contrary to the practice discussed above (§4.1), where one cameraperson pans out the other one, here the practice consists in one cameraperson moving to avoid being on the other’s view.

The local ecology of action and of videoing is changing rapidly: Bernard’s actions (asking a question, projecting a negotiation on what to do next) and movements (walking to the side of the box in front of the wall) make relevant for Alex to move there, too. This generates a converging movement of both participants towards the same place (A and B), joined by two other members of the team (John, 6, and later Yves, 12). Each cameraperson following them focuses on the same side of the box: when Cameraperson2 stops along the wall (9), Cameraperson1 begins at almost the same time (9) to move forward towards the box. These convergent movements of the participants and the camerapersons manifest a shared understanding of where the focus of the action is and will continue to be, and of the fact that the ongoing discussion — about the relevance of the contents of the box for the organization of the next steps of the work — might go on for a while there.

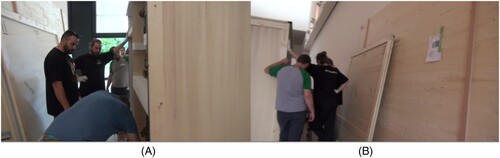

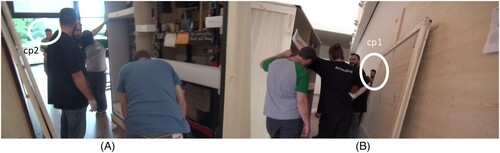

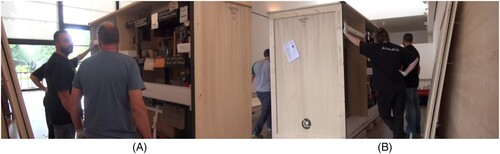

This convergence of the participants and their focus of attention produce a situation in which the two camerapersons (who were following two persons engaged in different tasks at different places) end up filming substantially the same view (A and B) from two very similar perspectives, both focused on a narrow and crowded space. This generates a dilemma: either both hold the same position or one changes it. Cameraperson1 moves away:

Extract 6b

Cameraperson1 approaches the box and stops (15) for a moment (until 18). This stop enables Cameraperson1 to realize that he occupies a very similar position as Cameraperson2, and that the discussion about the box can be anticipated to continue for a while (at this point, no decision has been reached about whether and how to empty this part of the box), making the contents of the box relevant for the next actions (the participants’ visual attention is focused on details of its contents). Cameraperson1 moves away (18) and begins to circumvent the box. He reaches the other side (26), while the participants continue to inspect the interior of the box and ask questions about its content.

The new position of Cameraperson1 enables a new distribution of the camera views (A and B). Each camera focuses on another extremity of the narrow corridor between the box and the wall, making a diversity of contents visually accessible. Their views are complementary, but they are also frontal. This generates a problem for the camerapersons, which emerges immediately after Cameraperson1 has stopped: Cameraperson1 appears on Cameraperson2’s view, and vice-versa (27, A and B). This is oriented by both camerapersons, as demonstrated by in the fact that Cameraperson2 pans immediately to the left (27, see B) and that Cameraperson1 adjusts his position just after (30, see A). Both camerapersons adopt the same solution: they pan their camera in such a way to maximally orient it towards the box, while positioning themselves against the wall, behind some plank that lies on the wall. This enables them to maximize both the visible focus on the action and their own invisibility. In this way, they also transform the frontal formation into a V-formation.

The camerapersons adapt not only to the emerging interactional space around the box, where the attention of the participants is focused, but also to their respective perspectives. They use the details of the local ecology — for example, the walls, but also the objects — for taking positions that maximize the perspective on the participation framework and minimize the possibility of featuring on the other’s view. The camera positions and views embody the ongoing skilled and adjusted vision of the camerapersons on the evolving action.

5. Conclusion

The paper contributes to a better understanding of video recording practices through their video documentation and multimodal analysis by providing a double focus, shedding light both on the detailed practices deployed in videoing social activities and on the fundamental features of videoed human action that they reveal in this way. In this sense, the analyses contribute both to the study of scientific practices in the social sciences and to the study of multimodal practices in social interaction. In order to video-record social actions, the camerapersons rely on the linguistic and embodied resources used by participants to make them intelligible: the camerapersons overhear and oversee these actions and adjust to them in real time. The analysis of these adjustments document the local interpretation and understanding of social interaction, for the all practical purposes of producing an adequate video-record of it.

The study has shown how collaboratively videoing is organized around complex and intertwined participation frameworks and interactional spaces and how it involves a finely-tuned embodied coordination between recorded activities and recording activities, which ultimately results in the production of scientifically exploitable video data for the analyses.

Camerapersons engaged in the production of EMCA-relevant records of social activities orient to offering maximal complementarity between relevant views on the recorded activity, while minimizing the visibility of the recording activity. These orientations are implemented by camerapersons in situated embodied practices such as:

establishing a ‘V-formation’ by walking and stopping so to position and adjust their bodies and cameras relatively to each other in a way that captures complementary views adjusted to the participant framework, without being mutually visible on the others’ camera;

producing panning movements of the cameras so to pan out the other cameraperson from the images produced by the recording device and, thus, minimize the visibility of the recording activity and maximize the visibility of the relevant participants.

navigating and exploiting details of the local environment in a way that similarly maximizes the complementarities and relevance of the views on the relevant ecology and minimizes the visibility of the camerapersons.

These practices reveal how the coordination between camerapersons is locally organized, as team members work orienting to each other, and to the distribution and economy of their work, while adopting similar ways of listening and looking at the unfolding events.

These practices share several important features. They sharpen the boundaries between what belongs to the recorded activity vs. the recording activity. They organize the camera views in a way that is centered on, and therefore reveals, the relevant elements of the activity (the participants and their interactions but also relevant objects and spatial details). Conversely, they also organize the camera views in a way that puts on the margins, or pans out, other less relevant and interfering elements (such as parallel activities, passers-by, objects not used within the activity at that point, and the camerapersons and their activity).

In this way, the camerapersons’ practices situatedly exploit the particular technology of the miniaturized portable video camera, which enables continuous movements and stabilizations adjusting to the events. The camera has also a particular format, a rectangular 3/4 or 6/9 frame, that is constantly checked through the camera monitor, and shapes the visual perception of the action in the field. This enables the work of framing the event, actively categorizing, through movements and stabilizations, as well as zooming in and out, exploiting the features of the camera optics, what features in the center of the view and what belongs to its periphery – in other words, what belongs to focused interaction vs. to mere co-presence (Goffman Citation1963). Contrary to other, more immersive views, such as those produced by 360° cameras and immersive VR, the classical camera is a technology that enables locally situated practices of framing, focusing, centering — of choosing what to include in the view and what not, what belongs to the participation framework, the interactional space, and the relevant material ecology, and what not. These technological features are not merely determining the professional gaze of the camerapersons. Rather, they are resources camerapersons exploit in their embodied and situated work, in their moment-by-moment organization of walking, looking and videoing in a collaborative manner.

The double focus on the recorded activity and the recording activity not only shows the complexity of the camera work as a form of situated proto-analysis (Macbeth Citation1999; Mondada Citation2006), including an embodied engagement in fieldwork — thus contributing to the study of the situated practices of producing relevant data for scientific purposes. It also reveals the detailed organization of the video recorded actions. This provides contributions to video studies and the study of social actions and activities in two ways. On the one hand, we have highlighted some recurrent methodic videoing practices, producing the analyticity and also the professional aesthetics of the camera views. This perspective provides for original materials for video studies of scientific work as a set of embodied practices (Garfinkel Citation2022). On the other hand, we have demonstrated the relevance of integrating — in the analysis but also in the transcription — the multimodal details of the ongoing action and the details of the activity documenting it. This enables a more comprehensive understanding of complex phenomena such as mobility, activity transitions, embodiment and materiality, participation frameworks and interactional spaces, at the same time as videoing, coordinating and collaborating, and the professional practices of field researchers.

Transcription Conventions

Transcription of talk follows the conventions of Jefferson (Citation2004), and transcription of embodied conduct follows the conventions of Mondada (Citation2018).

Conflict of interests

None.

Acknowledgements

Data collection and analyses have been supported by FiDiPro project ‘Multimodality’, funded by the Academy of Finland and the University of Helsinki (Finland) (project no 282931) and the University of Basel (NGK1382/DGK2589). A previous version of the paper was presented at the 15th International Pragmatics conference held in Belfast in 2017, and benefitted from discussions with the participants therein.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lorenza Mondada

Lorenza Mondada is professor for linguistics at the University of Basel. Her research deals with social interaction in a variety of ordinary, professional and institutional settings, within an ethnomethodological and conversation analytic perspective. Her specific focus is on video analysis and multimodality, integrating language and embodiment in the study of human action, as well as social relations, materiality and sensoriality.

David T. Monteiro

David T. Monteiro is a post-doctoral researcher in Social Work at GEACC-CLISSIS, Lusíada University of Lisbon. His research focuses on social interaction and the interplay between language, bodies and material environment, with a special concern with the interactional organization of professional-client encounters in healthcare and social intervention settings.

Burak S. Tekin

Burak S. Tekin is currently a lecturer at Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University. He obtained his PhD at the University of Basel, examining video game playing activities from an interactional perspective. His research primarily focuses on human sociality and the interplay of language, bodies and technology.

References

- Banks, M., and J. Ruby. 2011. Made to be Seen. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Broth, M., E. Laurier, and L. Mondada. 2014. Studies of Video Practices: Video at Work. London: Routledge.

- Cekaite, A., and L. Mondada. 2020. Touch in Social Interaction: Touch, Language, and Body. London: Routledge.

- Deppermann, A., and J. Streeck. 2018. Time in Embodied Interaction. Benjamins: Amsterdam.

- Garfinkel, H. 1967. Studies in Ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

- Garfinkel, H. 2022. Studies of Work in the Sciences. London: Routledge.

- Garrett, B. L. 2011. “Videographic Geographies: Using Digital Video for Geographic Research.” Progress in Human Geography 35 (4): 521–541.

- Goffman, E. 1963. Behavior in Public Places. New York: The Free Press.

- Goodwin, C. 1981. Conversational Organization: Interaction Between Speakers and Hearers. London: Academic Press.

- Goodwin, C. 1994. “Professional Vision.” American Anthropologist 96 (3): 606–633.

- Goodwin, C. 2018. Co-Operative Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Haddington, P., L. Mondada, and M. Nevile. 2013. Interaction and Mobility: Language and the Body in Motion. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Harper, D. 2012. Visual Sociology. London: Routledge.

- Heath, C. 1986. Body Movement and Speech in Medical Interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Heath, C., J. Hindmarsh, and P. Luff. 2010. Video in Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

- Jefferson, G. 2004. “Glossary of Transcript Symbols with an Introduction.” In Conversation Analysis: Studies from the First Generation, edited by Gene H. Lerner, 13–31. Benjamins: Amsterdam.

- Knoblauch, H., B. Schnettler, J. Raab, and H.-G. Soeffner. 2006. Video Analysis: Methodology and Methods. Berlin: Peter Lang.

- Lynch, M. 1993. Scientific Practice and Ordinary Action: Ethnomethodology and Social Studies of Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lynch, M., and S. Woolgar, eds. 1990. Representation in Scientific Practice. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Macbeth, D. 1999. “Glances, Trances and Their Relevance for a Visual Sociology.” In Media Studies: Ethnomethodological Approaches, edited by Paul L. Jalbert, 135–170. Washington: University Press of America.

- McIlvenny, P. 2019. “Inhabiting Spatial Video and Audio Data: Towards a Scenographic Turn in the Analysis of Social Interaction.” Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality 2 (1).

- McIlvenny, P. 2020. “The Future of ‘Video’ in Video-Based Qualitative Research is not ‘Dumb’ Flat Pixels! Exploring Volumetric Performance Capture and Immersive Performative Replay.” Qualitative Research 20 (6): 800–818.

- Merchant, S. 2011. “The Body and the Senses: Visual Methods, Videography and the Submarine Sensorium.” Body & Society 17 (1): 53–72.

- Mondada, L. 2003. “Working with Video: How Surgeons Produce Video Records of Their Actions.” Visual Studies 18 (1): 58–73.

- Mondada, L. 2006. “Video Recording as the Reflexive Preservation and Configuration of Phenomenal Features of Analysis.” In Video Analysis: Methodology and Methods: Qualitative Audiovisual Data Analysis in Sociology, edited by Hubert Knoblauch, Bernt Schnettler, Jürgen Raab, and Hans-Georg Soeffner, 51–67. Bern: Lang.

- Mondada, L. 2012. “The Conversation Analytic Approach to Data Collection.” In The Handbook of Conversation Analysis, edited by Jack Sidnell, and Tanya Stivers, 32–56. London: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Mondada, L. 2014. “Shooting Video as a Research Activity: Video Making as a Form of Proto-Analysis.” In Studies of Video Practices: Video at Work, edited by Mathias Broth, Eric Laurier, and Lorenza Mondada, 33–62. London: Routledge.

- Mondada, L. 2018. “Multiple Temporalities of Language and Body in Interaction: Challenges for Transcribing Multimodality.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 51 (1): 85–106.

- Nevile, M., P. Haddington, T. Heinemann, and M. Rauniomaa. 2014. Interacting with Objects: Language, Materiality and Social Activity. Benjamins: Amsterdam.

- Paterson, M., and M. R. Glass. 2020. “Seeing, Feeling, and Showing ‘Bodies-in-Place’: Exploring Reflexivity and the Multisensory Body Through Videography.” Social & Cultural Geography 21 (1): 1–24.

- Pink, S. 2009. Doing Sensory Ethnography. London: Sage.

- Pink, S. 2012. Advances in Visual Methodology. London: Sage.

- Rose, G. 1997. “Situating Knowledges: Positionality, Reflexivities and Other Tactics.” Progress in Human Geography 21 (3): 305–320.

- Rouch, J. 1974. “The Camera and man.” Studies in Visual Communication 1 (1): 37–44.

- Ruby, J. 2000. Picturing Culture: Explorations on Film and Anthropology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Sacks, H. 1984. “Notes on the Methodology.” In Structures of Social Action, edited by J. Maxwell Atkinson, and John Heritage, 21–28. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sikand, N. 2015. “Filmed Ethnography or Ethnographic Film? Voice and Positionality in Ethnographic, Documentary, and Feminist Film.” Journal of Film and Video 67 (3-4): 42–56.

- Streeck, J., C. Goodwin, and C. LeBaron. 2011. Embodied Interaction: Language and the Body in the Material World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Vannini, P. 2015. Non-Representational Methodologies: Re-Envisioning Research. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Vannini, P. 2020. The Routledge International Handbook of Ethnographic Film and Video. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Worth, S., and J. Adair. 1972. Through Navajo Eyes: An Exploration in Film Communication and Anthropology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Zimmerman, D. H., and M. Pollner. 1970. “The Everyday World as a Phenomenon.” In Understanding Everyday Life: Toward the Reconstruction of Sociological Knowledge, edited by J. D. Douglas, 80–103. Chicago: Aldine.