Abstract

This visual essay explores the intertwining relationships between urban transformation, homes (the physical dwellings), and imagination in Beijing over a time span of 12 years. The visual materials used in this study are photographs taken in and around the city of Beijing from the time leading up to the 2008 Olympic Games, in 2007, up to the pre-COVID-19 period. Inspired by Arjun Appadurai’s (Citation1996) writing on the social practice of imagination, this article explores the ways in which the imagination – the image, the imagined, and the imaginary – reflects, as well as constructs, the discursive practices of ‘the good life’ in dwellings. The images of the ordinary home not only help investigate the practices of imagination in ordinary life, but more importantly, they serve as a tactical intervention that encourages as well as urges us to contemplate and reflect on the transformation of China. They compel us to ask questions. How do the politics of the spectacular Beijing intersect with the politics of non-spectacular, ordinary everyday life? How have imaginations of the good life that drive support for the state-orchestrated development been displayed, constructed, disseminated, and materialised in the social lives of the ordinary? I argue that imagination of the good life carries the potential to aspire and transform; yet, it can also impose control, and subjugate one to the network of power relations that produces order and normativity.

Not Home Alone

This visual essay explores the intertwining relationships between urban transformation, imagination, and homes (the physical dwellings) in Beijing over a time span of 12 years. Inspired by Arjun Appadurai’s (Citation1996) writing on the social practice of imagination, this essay unpacks the ways in which the imagination – the image, the imagined, and the imaginary – reflects as well as constructs the discursive practices of the good life (美好生活) in the private realm of the home. The imagination, especially in collective forms, is ‘a staging ground for action’ (Appadurai Citation1996, 7). The dwelling/home is a personal private space, where the social practices of imagination are displayed, constructed, and materialised. Home is also the space that has been intimately connected with the political initiatives in China, from Reform and Opening policy (1978) to the ‘Chinese Dream’ (2012), that have advanced the country’s economic and political development (Chong Citation2020). Culturally speaking, home/housing is one of the four essential items (衣食住行, food, clothing, housing, and transportation) according to a common Chinese idiom, which presents the basic principle for an individual’s self-management.

This visual essay does not intend to make any claims of ‘truth’, rather it is an explorative and reflexivity essay aiming to trace the workings of the imagination in ordinary everyday life and elucidate how they drive the state-led development. The visual materials are photographs taken in and around the city of Beijing from the months leading up to the 2008 Olympic Games, in 2007, up to the pre-COVID-19 period. Photographs help document a particular movement and time, offering contextualised empirical data that cannot be captured by quantitative approaches (cf. Pauwels Citation2019; cf. Harper Citation2002).

These photographs not only help investigate the practices of imagination in ordinary life, but they also serve as a tactical intervention that encourages as well as urges us to contemplate and reflect on the transformation of China. They compel us to ask questions. How do the politics of the spectacular Beijing intersect with non-spectacular, ordinary everyday life? How have imaginations of the good life that drive support for the state-orchestrated development been displayed, constructed, disseminated, and materialised in the social lives of the ordinary?

The ‘visual dependencies’ (Zuev and Bratchford Citation2021, 8) in my research are built upon three reasons. First, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been actively mobilising visual strategies – posters, banners, Public Services Advertisements (PSA), documentaries, exhibitions, propaganda movies – in its public communication with the population since its establishment (cf. Galimberti, de HaroGarcía, and Scott Citation2020). Visual research is indispensable. Second, of relevance, the promotion of the 2008 Olympics, which was my first research project, involved a huge number of visual promotional materials. The sheer quantity and diversity of materials, and the specific time frame of a mega-event made photographic practice necessary. Third, China has been developing at such a fast rate and scale that the capturing of visual records is essential.

This visual essay is a work with images (Zuev and Bratchford Citation2021; Traue, Blanc, and Cambre Citation2019). As Bratchford rightly points out, a photograph ‘only momentarily disrupts movement and time’ (Citation2018, 395), its particularistic nature can be a limitation. Interdisciplinary (or, post-disciplinary) approaches that combine mixed methods are crucial (cf. Pink Citation2003; Zuev and Bratchford Citation2021) to make the ‘invisible’/the ‘hidden’ traceable. The photographs of homes around the period of the 2008 Olympics were initially taken out of curiosity. By combining ethnographic observations and semi-structured interviews with photographic practice, this essay connects the particularities of these images to the broader socio-political and urban development in China over a period of 12 years before the Covid-19. Based on photographs taken between 2007 and 2010, I developed a research project on physical dwellings and studies on smart home technology.Footnote1 The photographs here are a ‘subjective’ selection, based on ethnographic observations of, first, what I experienced as being representative of Chinese urbanity; and, second, their presentation of the regularities of daily life.

This essay allows the visual images to drive this personal and academic study, leading us to reflect on the changing politics of cultural governance. It draws us to rethink the dyadic relationship between centre/periphery, showcasing/concealing, familiar/strange, certainty/uncertainty, security/insecurity, control/resistance, faith/disappointment, (hyper-)visibility/invisibility, China/the World, local/global, permanent/temporary, inside/outside, inclusion/exclusion, macro-political economy/micro-ordinary daily lives, and optimism/pessimism. I argue that the imagination of the good life carries the potential to aspire and transform; yet, it can also impose control, and subjugate one to the network of power relations that produces order and normativity, here, the state-driven economic growth and stability.

The 2008 Olympics: A City of Imaginations

The visual exploration started with the Beijing Olympics as a global media spectacle that was meant to signify China’s ascendency in the global arena. Visuality played a central role in moulding the collective imagination of a ‘new’ Beijing and China. The city underwent a massive programme of demolition and gentrification for this visually-driven political performance. The erasure of ‘the old’ illustrated the state’s determination to construct what it envisioned how a world city should look: iconic architecture designed by celebrity architects (e.g. CCTV headquarters, designed by Rem Koolhaas), gentrified hutong(alleys formed by traditional courtyard houses)-shopping streets, such as Qianmen-Dashilan (前门–大栅栏)Footnote2 and Nanluoguxiang (南锣鼓巷),Footnote3 and a modern infrastructure, exemplified by the new subways (Ren Citation2008; Broudehoux Citation2007; Chong Citation2017).

Cultural critics, such as artists, photographers, and filmmakers, also widely mobilised visual strategies – visual arts, graffiti, documentary films – to critique and contest these rapid changes. Despite their contesting voices, these visual arts have also participated over the years in the making of the Olympics spectacle and the city of Beijing, and the urbanisation of China (cf. M. Wang and Valjakka Citation2015; Braester Citation2010; Visser Citation2004; de Kloet and Scheen Citation2013).

Homes, be they in hutongs or high-rises, were inseparable from the state-led urban transformation. The successful bid to host the Beijing Olympics in 2001 generated intense interests in ‘homes’: residents were actively talking about, and for some excitedly expecting, a lucrative rise of property value, as the Olympic Games were expected to attract visitors, and in the long run, boost Beijing’s status as a global city.

This apartment shown in was inside a gated community, Pinguo Shequ (苹果社区), completed in 2004 in Chaoyang District (朝阳区), the most populous and core district where the Central Business District (CBD) and foreign embassies are located. This estate was 10–15 mins walking distance to CBD, with subway stations nearby. The mainly ‘Western’ furnishings – IKEA fabric sofa, the lighting (a chandelier and an IKEA floor lamp), the wood-coloured laminate floor, the paintings on the wall, and the big living room window – and tidiness suggest an aspiring middle-class home. This home, displayed for potential tenants’ viewing, offered a sense of quality living, with a lifestyle that encompassed leisure and time. The floor-to-ceiling window was like a canvas presenting growth potentials: modern skyline, with high-density, high-rise apartment blocks suggest the booming development around it. Yet, the lower half of this canvas was darkened by the grey, low-rise buildings right next to it. This contrast whispers inconsistency in style and development, and likely the discords in design and planning. The proximity indicates this dwelling was on a lower floor: restricted views with lower market value. The dwellers were aspired to look up and far for growth, while reminded of, confined but also motivated by the less bright surroundings.

FIGURE 1. An apartment inside a gated community in Chaoyang District, the largest urban district in Beijing.

The studio-apartment shown in was an empty serviced apartment, completed in 2008, in Chaoyang District. Fully furnished, and with a generic modern design (e.g. open-kitchen, white furniture, wooden floor, modern electric heating system) in all the units, these apartments were meant to capitalise, first, on the incoming visitors for the Olympics; and second, on the rise in property value in the long run. The excitement about the potential growth in property value was dashed by the intensified global contestations during the Olympic torch relay that resulted in the subsequent strict controls on the granting of overseas visas for China, and on incoming visitors from other parts of China. Two land agents in suits attended this viewing. Their causal chatting postures suggested an imbalance of supply and demand: insufficient tenancy/sale appointments versus a surplus of agents. Many of these blocks remained underoccupied during the Olympics, but sales increased again over the years as the economy grew.

was a detailed scale model of the Dream World 2008 (国奧村 2008), the Olympic Village that housed the international athletes during the 2008 Games. The Dream World 2008 was developed as a post-Olympic residential project for locals. Detailed scale models have become common displays in Beijing and China, in a range of contexts from official venues, such as the Beijing Urban Planning Exhibition in Qianmen, to commercial development projects. These models visually materialise an overview – a complete picture with lightings, nearby facilities like roads and green areas – of a development that is strategically coordinated with the state-orchestrated ideas of looking at the big picture, and the impressive growth. The layouts of the apartments were imagined and displayed in separate models – similar to a doll’s house shown in – that visually zoomed in on the domestic home setting, an image for building more imaginations.

FIGURE 4. A model of the interiors of the apartment displayed for the Dream World 2008 (国奧村 2008), the Olympic Village.

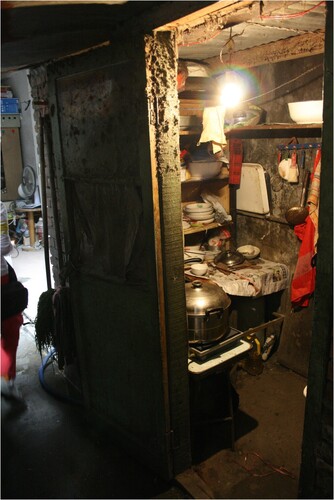

Historically traced back to the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), hutongs are said to represent the ‘cultural DNA’ of Beijing (N. Wang Citation1997) and were homes for local residents for many generations. The demolition and gentrification of many hutongs drew particularly intense media, artistic, and academic attention (Mao Citation2018; Stone Citation2008; Jiang, Chi, and Feng Citation2021). The pre-modern conditions inside homes in hutongs were rarely captured or presented. gives a glimpse of the interior of these homes, this space was crafted into a ‘cooking’ area with utensils and plates, yet improperly facilitated with no wash basin or sewerage system, and electric wires appeared unsafely ‘extended’ and ‘inserted’ for daily usage. The images of modern homes in high-rises in the mass media and around the city presented a home image of comfort and convenience. The contrasting images were also mobilised by the authorities, claiming demolition not only for gentrification but also for upgrading residents’ living quality and safety (e.g. fire hazards due to illegal structures and improper electric wirings). Residents of hutongs complained about the overcrowded space, and poor conditions and sanitary facilities (e.g. no private toilets or bathrooms) in these homes. Many were socially attached to their neighbourhoods, they also shared that they would prefer to accept a modern high-rise apartment and a compensation package. For some, the disputes surrounding demolition were about their forced removal without reasonable compensation, and about exploitation, corruption, and land speculation. Also around this period, many construction projects started to ‘wall up’ to hide the ‘work in progress’.

Beijing Leaping Forward

Two years after the Olympics, the World Expo 2010 in Shanghai – despite being less of a spectacle than the Olympics – used the slogan ‘Better City, Better Life’ (城市,让生活更美好). The importance of daily urban living and the ideal of good homes were displayed in many pavilions. One could recognise the evolution of state-driven urban development discourses – from demolition-destruction to construction-led directives – in the discourse on the good life in recent years.

Since the 2008 Olympics, China has also leapt forward with its technology-driven political economy. The interest in Beijing real estate has grown enormously over the years. The average sale price of residential real estate in Beijing, per square metre, grew from 4515 RMB (699 USD) in 2004 to RMB 42,684 (USD 6371) in 2020 – a 10-fold price increase within 15 years.Footnote4

The excessive increase in the sale price of real estate has created a captivating (and misleading) impression of ‘property = growth in wealth’, and has resulted in excessive property development in and around Beijing. The photo in was taken in December, 2015; this estate agency in Zhangjiakou (张家口), a prefecture-level city of Hebei bordering Beijing and one of the key sites for the 2022 Winter Olympics, named itself the ‘property supermarket’ (楼盘超市) on the building façade. By calling itself a ‘supermarket’ it mobilised the imaginary of abundance, freedom of choice, and agency. With a bank next door, it produced an image of financial feasibility and credibility. This ‘supermarket’ was inside, and was surrounded by under-occupied properties, reminding one of the disturbing images of ‘ghost towns’. Less well-off people, but with some capital, were the targeted consumers, often internal migrants who could not afford properties inside Beijing, and who had a mixture of longing for and fear of missing the golden opportunities.

One of the common features in the homes were the use of images and posters as decoration, shown in . The images within the posters, postcards, stickers, leaflets, and so on, reflect, remind, and project the inhabitants’ memories, imaginations, and desires. In practical terms, they also suggest temporalities – one’s (changing) aspirations as well as their precarity within this top-tier city. These visual materials are light in weight, and can be easily discarded and replaced when moving house or whenever one (dis)likes them. They are both ‘flexible’ and ‘functional’ as they help personalise a space, making it ‘homely’, taking away the bareness of an often nearly empty rental unit, and sometimes, covering poor conditions, traces of previous inhabitants, and the landlords’ controlling presence. These images open a wide range of imaginations of possibilities: one can be at home and in the imagined places and spaces, confined and free at the same time.

The space where these images were found, and the images themselves provided traces of the dwellers’ intersectional backgrounds: gender, class, family, age groups, and generational aspirations. Internal migrants to Beijing were often low-paid manual labourers, who maximised their savings by minimising their rental cost with less space and often the sub-par conditions. The images surrounding their beds ( and ) would be something these informants would see immediately before their dreamtime and when waking up; they served both as reminders that motivate daily efforts as well as their (collective) imaginations of a better and more hopeful future. The repetitive, orderly-aligned images of beds (), their compulsive presence suggested that they were not randomly chosen but symbolically significant to the subject. The educational posters () projected the parents’ imagination of what education meant for the next generation. The postcards and art-event leaflets – on the fridge against a well-maintained wall – in presented a ‘better’ home condition for a better-off subject aspired for experiential and imagined leisure and aesthetic journeys. All these images uncannily implicated mobilities ().

IKEA has been hugely popular in China, with their stores attracting enormous crowds, especially during the weekends and on public holidays. China is one of IKEA’s fastest-growing markets, and has had the largest annual volume of sales globally since 2017. Through its use of a set of generic formulae, which are both global and local at the same time (Chong and Chow Citation2021), IKEA produces, designs, and displays the ideal homes that guide one’s imaginations of what the good life could look and feel like. The store makes this so accessible and non-discriminatorily welcoming for anyone, that visitors are seen comfortably feeling ‘at home’, sitting, lying down, sleeping, or having chats in the showrooms. As Appadurai expressed it, ‘Where there is consumption there is pleasure, and where there is pleasure there is agency’ (Citation1996, 7). The popularity of IKEA has generated imitations and growth in the home furnishing market, with many of the products being sold on e-commerce platforms like Taobao.

China’s spectacular growth in technology has expanded the imaginations of the good life. Smart home technology – still in its infancy but with huge growth potential – has further advanced the imaginations of ideal homes that are not only fun and stylish, but also ‘safe’ and personalised to one’s needs. Individuals acquire a growing sense of control, freedom, and security, despite modern day challenges, such as air pollution and water safety. These home imaginations are not fantasy, but are ideas that drive exploration and actions supporting both urban and technological developments in China.

Coda: The Dyad of Aspiration and Desperation?

The collective imagination of the good life, anchored at home, allows us to see the ‘plurality of imagined worlds’ (Appadurai Citation1996, 5). The visual approach of homes directs a different set of perspectives and experiences, which complicates a general view about China: that the authoritarian state only controls and oppresses the people using force; while Chinese subjects are rendered as a uniform group of faceless, passive, and powerless victims. Ordinary subjects, of diverse backgrounds and economic means, have their own imaginations about how they can and want to live. Imagination is an affective and powerful force. It mobilises memory and activates desire, which are ‘central to all forms of agency’, as Appadurai (Citation1996, 31) reminds us. This agency suggests autonomous and self-governed actions that motivate and aspire. Yet, he was also critical of it: ‘even the meanest and most hopeless of lives, the most brutal and dehumanising of circumstances, the harshest of lived inequalities are now open to the play of the imagination’ (Citation1996, 54).

The ascendency of Beijing as a world-class city fuels imaginations for those outside the top-tier cities in China; they too aspire to lead a growth-driven good life. The home conditions of these internal migrants are often poor; however, they endure and persist with the imagined good life for the future. Their imaginations fuel Beijing’s growth with cheap manual labour. However, as Beijing and China moved forward, and the city further advanced its imagination of being a well-managed, well-organised, and safe global city, some were no longer welcome because they symbolised disruption; many were forcefully removed, and incoming migrants have faced stricter controls since 2017.Footnote5 The escalating home prices over the years had also made the imagined promise of home that brings stability, prosperity, and growth more distant, while further subjugating one to endless labour and sacrifices – unremitting catching up – just as Lauren Berlant’s Cruel Optimism (Citation2012) warns about the failed promises of the good life in liberal-capitalist societies. Imagination exposes a dyadic relationship between optimism and pessimism.

On a reflective note, this visual approach is entangled with my perspectives, personal journeys, and positionality. From searching for a temporary ‘home’ to researching ‘home’, I have been exploring the imaginations and homes in a globalising world. Like many of the people I encountered in these processes, I embodied as well as navigated around different identities – a Hongkonger, a female researcher, a migrant, a Chinese diaspora in the Netherlands, a daughter, and a parent, etc. – privileges and burdens at the same time. These identities enabled me to experience different (imagined) homes, with changing perspectives. The people I encountered were often as much curious about me as I was about them. Our similarities-yet-differences created a distance that was also translated into curiosities – and imaginations – among us. These imaginations opened the door for this visual approach, albeit unfairly and subjectively I am writing this essay, and I saw and experienced hers/his/theirs without reciprocal exchanges. As a method, the 12-year time span presents a temporal and spatial distance, allowing the images to travel beyond the momentary disruption of movement and time (Bratchford Citation2018) to speak back of the dyadic relationships between the past and the ‘present’, the spectacular and the ordinary, the personal and the national, aspiration and desperation.

The fast-advancing technological changes in China today also urge one to ask if and how (communication) technologies amplify the imaginations of the good life, and if they present possibilities and means of re-imagination that challenge the existing discourses and norms. Methodologically, this visual essay also represents a new development that urges one to explore and adopt different visual methodologies in research. What I noticed during these home visits was the rarity of the use of personal or family photos at home, except for the older subjects or those married with children. Informants explained that they had such images easily accessible on their smartphone, and the majority no longer printed out photographs. Physical dwellings remain essential, yet the ways in which imaginations are displayed, constructed, and materialised in the digital age, as Zuev and Bratchford proposed, require one to engage with different visual methodologies that consider the four aspects of ‘collection, production, analysis and communication of visual data’ (Citation2021, 27). For instance, the dependencies on the smartphone and the use of digital platforms in our daily lives requires one to consider how to integrate such interfaces into visual research.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the special issue organisers Dennis Zuev and Madlen Kobi, as well as the anonymous reviewers, and Gary Bratchford, for their support and helpful comments.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gladys Pak Lei Chong

Gladys Pak Lei Chong is Associate Professor at the Department of Humanities and Creative Writing at Hong Kong Baptist University.

Notes

1 The informants for the home research that started in 2015 were young people, born after Reform and Opening policy, and the one-child policy at the end of 1970s; while the research on smart home technology, which started in 2018, included young people as well as older subjects.

2 Qianmen is the area south of Tiananmen, the centre of Beijing. Dashilan is located right next to Qianmen street.

3 Located in the eastern half of Beijing urban centre (Dongcheng district), Nanluoguxiang is a neighbourhood with many hutongs, and famous for its traditional architecture. It has been transformed into a touristic shopping and restaurant area.

4 https://www.ceicdata.com/en/china/nbs-property-price-monthly/property-price-ytd-avg-beijing (accessed on 10 September, 2021) and https://www-statista-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/statistics/243404/sale-price-of-residential-real-estate-in-china/ (accessed on 1 July, 2022).

5 The axing of this group was triggered by a fire in Daxing, killing 19 people. This resulted in a huge public debate about this floating population, and the use of the derogatory term ‘low-end population’ (低端人口) – low education, low income – indicating that their presence was undesirable for Beijing.

REFERENCES

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. Modernity at Large. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Berlant, Laurent. 2012. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Braester, Yomi. 2010. Painting the City Red Chinese Cinema and the Urban Contract. Book. Asia-Pacific: Culture, Politics, and Society. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bratchford, Gary. 2018. “Visualising the Invisible: A Guided Walk Around the Pendleton Housing Estate, Salford, UK.” Visual Studies (Abingdon, England) 33 (4): 395–397. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2019.1584053.

- Broudehoux, Anne Marie. 2007. “Spectacular Beijing: The Conspicuous Construction of an Olympic Metropolis.” Journal of Urban Affairs, doi:10.1111/j.1467-9906.2007.00352.x.

- Chong, Gladys Pak Lei. 2017. Chinese Subjectivities and the Beijing Olympics. London: Rowman and Littlefield International.

- Chong, Gladys Pak Lei. 2020. “Dwelling, Aspirations, and the Good Life: Inter-Referencing Young People in Beijing and Hong Kong.” In Trans-Asia as Method: Theory and Practices, edited by Jeroen de Kloet, Yiufai Chow, and Gladys Pak Lei Chong, 177–210. London: Rowman and Littlefield International.

- Chong, Gladys Pak Lei, and Yiu Fai Chow. 2021. “Domestic Matters: IKEA Catalogues, Good Home, and the Changing Aspirations of Urban Chinese.” In Changing Senses of Place in the Face of Global Challenge, edited by Christopher Raymond, Lynn Manzo, Dan Williams, Andres di Masso, and Timo von Wirth, 313–328. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Galimberti, Jacopo, Noemí de HaroGarcía, and Victoria H. F. Scott. 2020. Art, Global Maoism and the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Book. Edited by Jacopo Galimberti, Noemí de Haro García, and Victoria H. F. Scott. Rethinking Art’s Histories. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Harper, Douglas. 2002. “Talking About Pictures: A Case for Photo Elicitation.” Visual Studies (Abingdon, England) 17 (1): 13–26. doi:10.1080/14725860220137345.

- Jiang, Jinlin, Yiqing Chi, and Jieyun Feng. 2021. “Struggle Between Tradition and Modernity: The Images of Beijing Hutongs in Anglo-American Media.” Critical Arts 35 (1): 65–84. doi:10.1080/02560046.2021.1887313.

- Kloet, Jeroen de, and Lena Scheen. 2013. Spectacle and the City. Spectacle and the City. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam. doi:10.2307/j.ctt6wp73q

- Mao, Ruoxuan. 2018. “The Commercialization of Beijing Hutongs.” Journal of Geography and Geology 10 (4): 39–49. doi:10.5539/jgg.v10n4p39.

- Pauwels, Luc. 2019. “Worlds of (In)Difference: A Visual Essay on Globalisation and Sustainability.” Visual Studies (Abingdon, England) 34 (1): 79–92. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2019.1621681.

- Pink, Sarah. 2003. “Interdisciplinary Agendas in Visual Research: Re-Situating Visual Anthropology.” Visual Studies (Abingdon, England) 18 (2): 179–192. doi:10.1080/14725860310001632029.

- Ren, Xuefei. 2008. “Architecture and Nation Building in the Age of Globalization: Construction of the National Stadium of Beijing for the 2008 Olympics.” Journal of Urban Affairs 30 (2): 175–190. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9906.2008.00386.x.

- Stone, Amy. 2008. “Farewell to the Hutongs: Urban Development in Beijing.” Dissent 55 (2): 43–48. doi:10.1353/dss.2008.0087.

- Traue, Boris, Mathias Blanc, and Carolina Cambre. 2019. “Visibilities and Visual Discourses: Rethinking the Social With the Image.” Qualitative Inquiry, doi:10.1177/1077800418792946.

- Visser, Robin. 2004. “Spaces of Disappearance: Aesthetic Responses to Contemporary Beijing City Planning.” Journal of Contemporary China 13: 39. doi:10.1080/1067056042000211906.

- Wang, Ning. 1997. “Vernacular House as an Attraction: Illustration from Hutong Tourism in Beijing.” Tourism Management 18 (8): 573–580. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(97)00079-4.

- Wang, Meiqin, and Minna Valjakka. 2015. “Urbanized Interfaces: Visual Arts in Chinese Cities.” China Information 29 (2): 139–153. doi:10.1177/0920203X15589704.

- Zuev, Dennis, and Gary Bratchford. 2021. Visual Sociology. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG.