Abstract

With 22 per cent of its housing stock vacant, China has the highest vacancy rate in the world. Yet Chinese cities are marked by constant expansion and the construction of high-rise buildings. Why are all these ‘empty homes’ being built? And what moves people to buy homes in which they cannot live? In this article, we explore these questions through a filmmaking project embedded in long-term ethnographic fieldwork in Wuhan. The film Empty Home, included in this article, focuses on the social and symbolic aspects of home- and city-making, revealing the importance of homeownership for mobile Chinese families in a rapidly transforming society. This article views the real-estate market as an important site for constructing citizen-state relations and argues that the symbolic and social significance of empty homes is crucial for understanding the deep meanings of the Chinese state’s drive for urban expansion and Chinese citizens’ desire to become homeowners. In addition to contributing to knowledge about Chinese homemaking, the article shows how using filmmaking in ethnographic fieldwork can strengthen the research process.

INTRODUCTION

High-rise apartment blocks can be seen all over Wuhan, the capital city of China’s Hubei province. Its horizons are full of cranes and structures draped with green construction gaze and displaying gigantic telephone numbers hanging down the towers under construction, which inform prospective buyers who to ring. These signs of a building frenzy are not confined to the city centre. Leaving Wuhan by car, you drive through a repetitive landscape of new residential areas, with new roads, train stations and high rises under construction as far as the eye can see. When you drive into these residential areas, however, you are struck by the strange absence of residents. An eerie silence demonstrating the lack of human presence remains after the sound of drilling and the chatter of construction workers subside.

China has the highest housing vacancy rate of all countries in the world. It is estimated that 22 per cent of Chinese housing stock is vacant, so that 65 million privately owned properties in China do not have occupants (Batarags Citation2021; Bloomberg News Citation2018). Recent unrest in the Chinese property world caused by financial turmoil in the Evergrande Group, one of China’s biggest property developers (Yu, Mcmorrow, and Ju Citation2021) led to a downturn in markets worldwide and attracted attention to the high number of vacant apartments in China (Toh Citation2021). Before this happened, China’s endless landscapes of empty housing stock had already been commented on in Chinese and international media (Woodworth Citation2020; xx Citation2016; Diamond Citation2018). However, all this focus on China’s empty housing stock has not stopped builders from constructing, consumers from buying, and local governments from planning new real-estate developments. Why?

The academic and media reports that discuss China’s empty housing stock tackle this phenomenon mainly in economic terms, asking whether this vacancy rate is the sign of an economic bubble (Stahl Citation2013; Fung Citation2014; Glaeser et al. Citation2017). The owners of these vacant properties are thought to be wealthy individuals who invest in property because they think it is safer and more profitable than keeping their savings in the bank. Our findings shed light on a radically different perspective. Shifting the focus to the social and symbolic aspects of the purchase of housing by less than wealthy residents, this article demonstrates that ‘empty homes’ can be much more than an investment opportunity. Complementing anthropological and sociological literature on the concept of home, we also show that using filmmaking in ethnographic fieldwork can illuminate the social and symbolic significance of the relationship between a home and its owner.

In this article, we therefore bring together debates about vacant property, rural-urban relations and the potential of visual methods of social research. Firstly, we discuss the literature on China’s high vacancy rates and the increased importance of homeownership in relation to the literature on the renegotiation of rural-urban relations in China. Secondly, we explain why introducing a camera into this field site generated new insights. After this, we present two case studies, including a short film entitled Empty Home co-created by the two authors (Verstappen and Sier Citation2016), and analyse why rural families own vacant property in Chinese towns and cities. We argue that, although they have no inhabitants, empty homes still have great symbolic and social significance for their owners.

Our analysis focuses on the experiences of rural-urban migrant families for whom homeownership is an important tool for navigating the competitive marriage market in a rapidly urbanising China. For individual homeowners, the home becomes a site of emotional gratification; within the family, the home enables dispersed relatives to maintain family bonding amid their experiences of hypermobility; and in the relationship between the family with the wider society, the home is of paramount symbolic importance in negotiations of family status and marriage. An analysis of these dynamics offers new insights into the connection between the large number of vacant homes in China and the country’s ongoing rural-urban transition.

HOUSING VACANCY RATES IN CHINA

Rising housing vacancy rates have been reported in countries ranging from India (Chandran Citation2018) to the UK (Busby Citation2018), and from Japan (Shomaker Citation2021) to the USA (Badger Citation2012). This phenomenon has attracted criticism at a time of severe housing crises that have left many homeless. Explanations for this international phenomenon have been sought in the globalisation of real estate and the proliferation of neoliberal economic policies that have allowed real-estate markets to operate across national borders, enabling an international class of elites to invest in real estate while soaring prices make homeownership inaccessible to local workers and residents (Rogers and Koh Citation2017). Since its liberalisation, the Chinese housing market has become increasingly popular with foreign investors, while wealthy Chinese investors have also been found to be buying large quantities of real estate both in China itself and in other countries (Rogers and Koh Citation2017; Gaspar Citation2020). The size and rapid growth of the Chinese real-estate market make it a popular topic for the economists who focus on the Chinese economy. In such studies, the country’s high vacancy rate is construed as a risk factor. For example, Glaeser et al. (Citation2017) compare US and Chinese housing markets and offer a number of scenarios that may occur in the Chinese housing market. Their findings confirm that the combination of crowded cities and empty housing stock is a distinctive feature of China’s housing landscape (Citation2017, 102), and that this can affect future prices of real estate if the Chinese state does not implement measures to balance supply and demand (Citation2017, 94).

Other social scientists, however, argue that the Chinese state’s ideological commitment to urban growth goes beyond economic logic. Political scientists Sorace and Hurst (Citation2016) suggest that the expansion of cities also needs to be considered as symbolical and political signs of China’s modernisation, which play an important role in people’s assessment of the state’s political performance and its legitimacy. These dynamics lead to contradictory scenarios in which local states continue to construct more housing in cities even when there is no direct need for it and if constructing it carries a huge financial burden (Sorace and Hurst Citation2016, 305). Zhang (Citation2010) demonstrates that homeownership has emerged as a central concern for Chinese development policies, which now promise homeownership for all Chinese citizens – a radical break with earlier ideologies that eschewed private property. Zhang explains that there has been a shift in attitudes towards housing and private property after Mao’s rule (1949–1976), when owning private property put citizens in the dangerous category of the landlord class, which could lead to their persecution during political campaigns that called for the eradication of property-based class divisions. Conversely, when state-owned companies were split up and privatised as part of the economic reform starting in 1978, citizens were encouraged or obliged to take on the responsibility for their own housing. The real-estate boom that followed this move transformed China from a predominantly public housing regime to a country with one of the highest rates of private homeownership in the world and made house ownership one of the most important markers of social status in Chinese society (Fleischer Citation2007; Zhang Citation2010). We contribute to these studies of the symbolic and social meanings of real estate by addressing the views of China’s rural-urban migrants, whose lives have become mobile and unstable after decades of development policies with an urban bias led to mass migration from China’s countryside to the cities.

The rural-urban divide is the deepest social divide in Chinese society, where rural and urban refer not only to geographical locations, but also to two types of citizenship status that Chinese citizens can be ascribed through the country’s hukou system. This residency registration system assigns people either rural or urban status at birth (depending on the status of their parents), and this has massive consequences for citizens’ access to state services and subsidies. Even though scholars have long argued that the hukou system is an important source of injustice (Alexander and Chan Citation2004), more recently researchers have tried to decentre the debate on the hukou system in studies on rural-urban relations, arguing that additional factors are crucial for shaping rural-urban inequalities, including the conditions in the Chinese real-estate market (Zhan Citation2011; Wang et al. Citation2020). During the reform era the privatisation of urban real estate led to a rapid rise in the price of urban property. The rural housing policy did not change to the same extent; the state does not allow the free trading of rural residential properties and although houses may be recognised as private property, the land on which they are built still belongs to the village collective (Wang et al. Citation2012). These factors have enlarged the wealth gap based on real estate among rural and urban citizens (Wang et al. Citation2020). Purchasing real estate in Chinese cities for rural-urban migrants is further complicated by their nonlocal and rural hukou registration, which prevents them from accessing subsidised housing. Moreover, it sometimes means they have to fulfil extra requirements to buy a house (e.g., make higher down payments than urban people, or show they have paid at least two years of social insurance or income tax in the city) (Chen, Shi, and Tang Citation2019). Moreover, the imbalanced sex ratio in rural China has heightened competition between prospective husbands and homeownership has become a very important requirement for marriage (Driessen and Sier Citation2021).

This article focuses on the social and symbolic aspects of buying urban real estate among migrants to the city with a rural hukou. It asks: why do people buy houses in which they cannot live? The answer, for rural migrants in today’s China, is that owning a house can serve as an anchor for their dispersed family. The house furnishes them with a social identity, showing that they are part of China’s urban middle-class and symbolising their relationship with the city. By demonstrating these houses have other functions in addition to offering families’ investment opportunities or places to live, we shed new light on questions about the high vacancy rates in China’s housing stock.

EMPTY HOMES: CONCEPTUAL AND METHODOLOGICAL PREMISES

By drawing attention to the practices and narratives by which owners create a sense of home in these properties even if they do not live in them, we conceptualise the properties not merely as vacant houses or financial investments, but as empty homes. Our interpretation of the notion of home draws on recent studies in the field of migration and diaspora (Frost and Selwyn Citation2018; Rapport and Overing Citation2000). While the home was conceived in earlier scholarship primarily as a space of dwelling (Douglas Citation1991, 289–290), contemporary migration scholars reconceptualise home as ‘a special kind of relationship with place’ that is experienced through feelings of familiarity, security, and control (Boccagni Citation2017, 7). This conceptual delinking of the home from a dwelling helps us to understand the sense of home articulated by China’s highly mobile rural-urban migrants.

Scholarly efforts to reconceptualise the home have been paired with methodological innovations to enhance qualitative research into the question how people experience home, with growing interest in visual methods (Boccagni Citation2017, 30–43). Examples include home video interviews (Pink Citation2004), photographs or videos of domestic practices (Arnold et al. Citation2012; Daniels Citation2021; Verstappen Citation2021), and participant-generated photographs to explore where and when people feel at home (Sirriyeh Citation2010). Our use of filmmaking resonates with the home video interview, in which the interviewed can point to the aspects they find important while talking and showing the researcher around their home.

Our film could not have been recorded without the prior ethnographic research in China’s Hubei province (Sier Citation2020); yet the decision to collaborate on a film project in the last phase of this ethnographic research (with camera work by Sanderien Verstappen) enabled us to concentrate on the house itself. The selection of a house where the film could be made was a prompt for further and more concrete research into the location of various houses; once a house had been found for the filming, the introduction of a second researcher with a camera heightened the focus on the concrete, the material and the performative aspects of homeownership. The protagonist (Wendy) took an active interest in and to some extent control over the filming process, for example, by pointing out objects to film and explaining what they meant. The process of filming therefore worked as a catalyst to probe the relationship between a home and its owner, and as a tool with which to reflect on this relationship. Preparing, filming, editing and discussing the film led us to pay increased attention to what was present in the house, seeing beyond the absence of its residents. In screenings of the film, we considered these presences and their meanings from the perspectives of our audiences (Rutten and Verstappen Citation2015). Our analysis of the meanings that these empty homes hold for their owners highlights the value of reconceptualising home beyond the notion of a fixed, physical dwelling, and the importance of understanding that buying a house is more than a financial strategy.

THE FILM Empty Home (2016)

When Willy Sier conducted ethnographic fieldwork in China’s Hubei province (2015–2016) among young university-educated people from rural backgrounds, she noticed that the topic of buying houses was frequently discussed. Everybody seemed to be in dire need of a house or an apartment, preferably in the city (Sier Citation2021). However, she also found that in many cases places were purchased, only subsequently to remain unoccupied. These houses or apartments were located in small towns and cities as well as on the furthest outskirts of the provincial capital, Wuhan, in areas with a plentiful supply of newly constructed buildings but devoid of people. In these far-flung urban peripheries, houses are affordable, yet as they are so remote from facilities, industry and labour markets, homeowners are forced to reside elsewhere, closer to their places of work. These field observations were the starting point of a short film, Empty Home. It was made in cooperation with Wendy, a young rural-urban migrant in Wuhan who agreed to show us her family’s recently acquired apartment and answer our questions about why this house was purchased in front of the camera.

[The film Empty Home: https://vimeo.com/209590747]

Wendy loves her home (jia, in Chinese). The apartment, with two bedrooms, a living room, and a kitchen is in the quiet suburbs in Wuhan’s Hankou district. The new furniture, air-conditioning and flat screen TV make the flat comfortable and convenient, and the space is lovingly decorated with hand-knitted flowers and pictures painted by Wendy and her sister. However, despite the effort and investment that went into furnishing and decorating the apartment, nobody has spent much time living there. Only once did the family gather together there for a New Year’s celebration. But, preferring to be surrounded by their old neighbours, friends, and family members during these weeks of festivities, the family chose to return to their village for subsequent New Year’s breaks. If the family spends so little time in their apartment, why does Wendy perceive it to be her home?

EMPTY HOMES AS ANCHOR POINTS

Existing explanations encourage us to understand empty property in financial terms, and thus to recognise the value of empty real estate as something that can provide a sense of financial security in an unstable environment (e.g. Glaeser et al. Citation2017). While Wendy agrees with this explanation, saying that real estate prices in China ‘can only go up’ and acknowledging that the house can be seen as a clever investment, she also repeatedly stresses that the apartment means much more to her than an opportunity to make money. Although none of the family members have spent much time in the apartment, Wendy is adamant about calling it her home. The emotional investment that has gone into an apartment that belongs to Wendy’s family suggests that empty homes can serve to anchor dispersed families.

Wendy’s family is a characteristic example of the hundreds of millions of Chinese rural-urban migrants who are popularly referred to as the country’s floating population. Her family is dispersed throughout the country – her parents and sister live in Guangzhou, a megacity in southern China, some family members live in Wuhan and one uncle remains in the old family home in rural Hubei province. From the time that Wendy was born, she and her family members have been separated and on the move. With her parents working as labour migrants, Wendy spent most of her childhood with her grandparents and as a boarder in the school system from the age of 10.

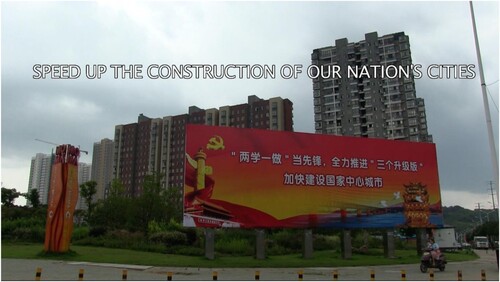

Wendy’s family members also belong to the growing number of Chinese ‘rural’ citizens who settle permanently in cities. These rural-urban migrants are the product of a set of policies by the Chinese state, including the ‘National New-Type Urbanisation Plan (2014–2020)’. This plan, released by the Central Committee of the China Communist Party on 16 March 2014, set out the aim of increasing the percentage of the Chinese population living in cities from 53.7 per cent in 2014 to 60 per cent in 2020. Indeed, many Chinese cities are rapidly expanding. In Wuhan the number of residents increased from 2 million in 1970 to more than 10 million in 2018. The promotion of the city and urban living as the desired form of modernity is also reflected by government campaigns that call for speedy construction of the urban environment ().

FIGURE 1. The billboard reads: ‘Speed up the construction of our nation’s cities’. (Still Empty Home, minute 14.19).

In 2012, Wendy’s parents decided to buy an apartment in Wuhan, where both of their daughters were studying and working at the time. They invested several decades of their savings from working in factories and restaurants. Wendy continued to live in the vicinity of the campus after she graduated, when she opened a small fashion shop in the campus area together with her friend, Lucky. In 2016, during the making of the video, the two young women slept every night on a fold-out couch in their shop (). Wendy did not live in the apartment her parents bought because it was too far away from the shop to commute, and the city’s extensive metro system did not reach the apartment. Wendy nevertheless imagined that her parents would live there after their retirement, even though she admitted that her father had not been very enthusiastic about the prospect. It was clear that an elderly couple would face considerable challenges if they lived in the apartment. Given that there was no access to public transport or shops or markets in walking distance, and there were hardly any neighbours living in the building, the whole area was characterised by a remarkably silent atmosphere.

FIGURE 2. The shop in the campus area of Wuhan where Wendy lived in 2016, two hours of travel time from the apartment her parents had bought in the outskirts of Wuhan. (Stills Empty Home, minutes 12.00 and 12.59).

Despite the fact that neither Wendy nor her sister or parents live there, the apartment holds important symbolic meanings for them. One meaning is its location: it is in the city. Families like Wendy’s have practiced rural-urban migration since the 1980s, when massive economic development in the cities created labour opportunities for rural workers and restrictions on mobility were lifted. They are now making their connection to the city more permanent by buying urban property, despite the continued restriction of the Chinese hukou system. Among rural families with long histories of mobility, the purchase of an urban apartment can thus be seen as a way of completing the process of rural-urban transition. The symbolic value of purchasing a home in the city seems to lie in its power to solidify rural migrants’ urban status and their sense of belonging to an urban community.

Another meaning of the house lies in its ability to provide physical evidence that this family exists. Wendy shows us that the house is full of objects with meanings. The shoe cabinet was custom-made to store her sister’s shoes. The house slippers and blankets in the cupboard were made from cotton produced in their village of origin. The drawings on the wall were sketched by Wendy and framed by her father. The IKEA painting with the words ‘Love Home’ and the textile flowers were brought into the house ‘with our own hands’ (). Anthropologists of material culture think of such practices of decoration and personalisation as a way of ‘turning houses into homes’ (Edwards Citation2005), and they have analysed the links between collecting and purchasing goods and the agent’s social relations, especially those based on love and care (Miller Citation1998). Through such small acts of love and care, Wendy and her family have turned a financial investment into a home, and this home has now become an anchor point for the family. Wendy explains that she sometimes goes to the apartment for a few days just to be there, feeling that this brings her closer to her family.

FIGURE 3. Wendy shows meaningful objects in the house, such as the shoe cabinet and the textile flowers. (Stills Empty Home, minute 03.35 and 15.15).

Overall, the practices that constitute buying and decorating a house seem to provide their owners a sense of social and emotional security. Even if the home is empty, in the sense that family members are rarely there, it is full of objects and meanings that refer to the past, present and future of the dispersed family, while its urban locality shapes its meaning as a site of their aspirations and their orientation in the wider society.

EMPTY HOMES AS ‘MARRIAGE HOUSES’

To deepen the analysis of empty homes in China, it is useful to compare the empty home shown in the film with a second case study. In February 2016 Willy Sier attended the wedding of a young couple in rural Hubei province. The couple had met through a marriage agent and were not yet very familiar with one another. The celebrations started with one day of festivities on the premises of the bride’s family. The next morning the bride was ‘taken’, in the form of a mock kidnap, by the groom to his family house. After the groom carried the bride into his car, he drove towards his village, followed by a parade of cars transporting the wedding guests who were part of the bridal party. On the way, the parade stopped at the marriage house (hunjia), a property purchased by the groom’s family as part of the wedding negotiations.

This marriage house (a and b) had been the subject of much discussion during and before the wedding on the bride’s side of the family. The negotiations between the two families had not been very smooth. The bride’s family had demanded that the groom’s family bought a privately owned apartment before the wedding, requiring an enormous investment from the latter. Their inability to make this investment had led to the postponement of the marriage the previous year. Now, the house had been bought, but the aunt in case remained unimpressed: ‘It’s only a very cheap house’.

FIGURE 4. (a). The bedroom with the blankets that were given as part of the dowry and the wedding picture in the window. (b). The new sofa in the living room. (Photographs by Willy Sier during a visit to a marriage house on 4 February 2016).

That day, the string of wedding cars drove down the gravel roads among fields and through rural hamlets for about an hour, following the car transporting the new couple and the dowry, a sizeable collection of thick winter blankets, before we arrived in a small township called Gaoyang. Gaoyang is the township closest to the groom’s village, accessed by a dusty road lined by shops and multistorey buildings. The building in which the marriage house was located was a simple, five-storey cement construction. Through large doors made of metal and plastic, we entered the bare, unlit stairways and walked up to the fifth floor. At the door, the groom’s family members received us with hot water and tangerines before giving us a quick tour of the house. The apartment was spacious, about 60 square metres, and had been newly renovated. There were two bedrooms, a bathroom, and a living-dining-room, all carefully decorated and decked out with brand-new furniture: a large sofa, dining table, beds, a luxurious bathroom and a large flat screen television. Some of the furniture and appliances were still covered in plastic, waiting to be unwrapped. In the bedroom there was a large print of one of the couple’s wedding pictures.

Minutes later we were rushed back to the cars, as the family hoped to start the ceremony in the groom’s village exactly at noon, an auspicious hour. As we arrived in the house of the groom’s family, I thought about the contrast between the marriage house and the houses in which the bride and groom had grown up. The farmhouses were simple, with bare cement floors and without heating or bathroom facilities. In these cold rooms, people sat around the coal stove to warm themselves, and they relieved themselves at the back of the house, behind a simple screen. However, what was most surprising was that despite the obvious contrast in convenience and living standards between the farmhouse and the marriage house, and despite the considerable investments made in purchasing and decorating the marriage house, neither the couple nor their family members would actually live there. After the wedding, the bride and groom planned to return to Dongguan and Guangzhou, respectively, two of China’s largest southern cities and very popular destinations for migrant labourers from Hubei province, to continue working as a chef and a factory hand.

If mobility and urban orientations go a long way to explain the increased participation of rural middle-class citizens as house owners in the real-estate market, their house ownership is also shaped by changing gender norms and marriage markets. Today, many people in rural Hubei say that ‘without a house, marriage is just not possible!’ They explain this by referring to China’s history of patrilocal living, stating that it is traditional to have a marriage house. However, this tradition has changed dramatically over the past decades. In earlier form of patrilocal living in rural Hubei, provision of a marriage house by a groom’s family was also part of the wedding tradition, yet it often consisted of no more than redecorating a room or building a structure on the family plot in the husband’s village. Today, rural families are expected to provide newlywed couples with costly privately owned apartments, preferably in an urban environment.

China scholars observe that in China post-Mao, the increasing importance attached to material success and security in the capitalist labour market is linked to new attitudes vis-á-vis gender differences, which had been diluted in a communalist ideology of gender equality but re-emerged in a capitalist labour market in which a man’s self-worth is tied to his ability to make money, possess goods, and gain political power (Zhang Citation2010, 166). As a result, the purchase of a house is considered to be primarily the responsibility of men, who bear the primary burden of providing for their families. This gender ideology is also shaped by China’s highly imbalanced gender ratio. In this context, today’s parents face considerable difficulty in helping their sons to find a wife, especially in rural areas, where the relative lack of marriageable women increases the bargaining power of the bridal family (Driessen and Sier Citation2021). If Wendy’s family house offers insights into homeownership as a way to anchor dispersed families in times of mobility and rural-urban transition, the marriage house offers another insight in the meaning of house ownership for rural men in a changing marriage market.

CONCLUSION

How might we understand the fast expansion of China’s urban peripheries, full of newly constructed flats but devoid of people, shops and work opportunities? In this article, we have looked beyond the familiar images of empty streets and lifeless flats and have entered two of these flats at a time when the house owners had visited the otherwise locked apartment, to learn what these places mean to the people who purchase them.

Our conceptualisation of these houses as empty homes contributes to anthropological and sociological studies of home and homemaking, which aim to broaden the concept of home beyond the narrow meaning of a dwelling (Boccagni Citation2017). We have arrived at this conceptualisation using a combination of research methods, by combining classic ethnographic methods such as interviews and participant observation with a filmmaking project that allowed us to focus in detail on what was present in one such vacant house. The film Empty Home highlights the social and symbolic significance of the relation between a vacant house and its owner but also demonstrates more broadly how filmmaking can strengthen and deepen ethnographic attention to the concrete practices through which people make and experience a home. This filmmaking project was complemented with comparative research into other kinds of empty homes in China. To understand why rural-urban migrants in China buy houses in the cities, but often do not live in their urban houses afterwards, we have engaged with the symbolic and social meanings of house ownership, in addition to financial and material ones, from the perspective of the absentee house owners.

Existing studies of changing real-estate markets in China have focused almost entirely on relatively wealthy families with an urban hukou. It has been argued (Fleischer Citation2007) that for urban families, owning a house means choosing a lifestyle that indicates their class position in urban society (Zhang Citation2010). In this article we have shifted the focus to a group of home buyers that remains unacknowledged in academic discussions on the real-estate market in China: the rural house-owners in the city. We have argued that, for them, homeownership conveys somewhat different meanings. Their lives are characterised by mobility and their aspirations are directed towards urbanisation. In this context a house becomes both a source of financial security and an attempt to stabilise their lives socially and emotionally. The house holds great symbolic power as a material anchor for a family that is spread out all over the country; as a place from which individual family members can feel connected to their family even when they are not physically present. Buying an urban house is, moreover, seen as a great accomplishment that marks the completion of the transition from a rural past to an urban future and an affirmation of new urban identities, even if the house cannot (yet) be lived in. This results, however, in an unresolved tension: if the house is a means to seek anchorage in a context of intense mobility, that same house forces the family to keep afloat. For families like those we have described above, buying a house is a substantial financial investment: they use mortgages to buy their new apartments and to afford the mortgage payments, the owners had no choice but continue working as labour migrants. There is thus a tension between the desire to settle down through buying property and the need to be mobile to afford such a purchase.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Wendy for literally opening her home to us and to all other interlocutors who supported this project. We also thank Carole Pearce for her writing support.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- Alexander, P., and A. Chan. 2004. “Does China Have an Apartheid Pass System?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 30 (4): 609–629. doi:10.1080/13691830410001699487

- Arnold, J., A. Graesch, E. Ragazzini, and E. Ochs. 2012. Life at Home in the Twenty-First Century. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

- Badger, E. 2017. ‘When the (Empty) Apartment Next Door Is Owned by an Oligarch.’ The New York Times, 21 July, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/21/upshot/when-the-empty-apartment-next-door-is-owned-by-an-oligarch.html.

- Batarags, L. 2021. ‘China Has at Least 65 Million Empty Homes – Enough to House the Population of France.’ Business Insider, 14 October, https://www.businessinsider.com/china-empty-homes-real-estate-evergrande-housing-market-problem-2021-10?international=true&r=US&IR=T.

- Boccagni, P. 2017. Migration and the Search for Home: Mapping Domestic Space in Migrants’ Everyday Lives. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Busby, M. 2018. ‘England Has More Than 200,000 Empty Homes. How to Revive Them?’ The Guardian, 25 September, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/sep/25/england-has-more-than-200000-empty-homes-how-to-revive-them

- Chandran, R. 2018. ‘Thousands of Low-Cost Homes Empty in India Despite Urban Shortage.’ Reuters, 9 July, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-housing-rights/thousands-of-low-cost-homes-empty-in-india-despite-urban-shortage-idUSKBN1JZ29L.

- Chen, Y., S. Shi, and Y. Tang. 2019. “Valuing the Urban Hukou in China: Evidence from a Regression Discontinuity Design for Housing Prices.” Journal of Development Economics 141: 102381. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2019.102381

- Daniels, I. 2021. ‘Disobedient Buildings.’ https://www.disobedientbuildings.com.

- Diamond, M. 2018. ‘A Fifth of China’s Homes Are Abandoned. Take a Look Inside China’s “Ghost Cities.”’ Insider, 19 December, https://www.insider.com/inside-chinas-ghost-cities-photos-2018-12.

- Douglas, M. 1991. “The Idea of a Home: A Kind of Space.” Social Research 58 (1): 287–307.

- Driessen, M., and W. Sier. 2021. “Rescuing Masculinity: Giving Gender in the Wake of China’s Marriage Squeeze.” Modern China 47 (3): 266–289. doi:10.1177/0097700419887465

- Edwards, C. 2005. Turning Houses Into Homes: A History of the Retailing and Consumption of Domestic Furnishings. London: Routledge.

- Fleischer, F. 2007. “To Choose a House Means to Choose a Lifestyle.” The Consumption of Housing and Class-Structuration in Urban China.’ City and Society 19 (2): 287–311. https://doi.org/10.1525/city.2007.19.2.287

- Frost, N., and T. Selwyn. 2018. Travelling towards Home: Mobilities and Homemaking. New York: Berghahn.

- Fung, E. 2014. ‘More Than 1 in 5 Homes in Chinese Cities are Empty, Survey Says.’ 11 June, 2014. Wall Street Journal, 11. https://www.wsj.com/articles/more-than-1-in-5-homes-in-chinese-cities-are-empty-survey-says-1402484499.

- Gaspar, S. 2020. “Buying Citizenship? Chinese Golden Visa Migrants in Portugal.” International Migration 58 (3): 58–72. doi:10.1111/imig.12621

- Glaeser, E., W. Huang, Y. Ma, and A. Shleifer. 2017. “A Real Estate Boom with Chinese Characteristics.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 31 (1): 93–116. doi:10.1257/jep.31.1.93

- Miller, D. 1998. Material Cultures: Why Some Things Matter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bloomberg News. 2018. ‘A Fifth of China’s Homes Are Empty. That’s 50 Million Apartments.’ 8 November, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-11-08/a-fifth-of-china-s-homes-are-empty-that-s-50-million-apartments.

- Pink, S. 2004. “Performance, Self-Presentation and Narrative: Interviewing with Video.” In Seeing is Believing?: Approaches to Visual Research, edited by Christopher J. Pole, 61–77. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Rapport, N., and J. Overing. 2000. “Home and Homelessness.” In In Social and Cultural Anthropology: The Key Concepts, edited by Nigel Rapport, and Joanna Overing, 154–162. London: Routledge.

- Rogers, D., and S. Y. Koh. 2017. “The Globalisation of Real Estate: The Politics and Practice of Foreign Real Estate Investment.” International Journal of Housing Policy 17 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1080/19491247.2016.1270618

- Rutten, M., and S. Verstappen. 2015. “Reflections on Migration Through Film: Screening of an Anthropological Documentary on Indian Youth in London.” Visual Anthropology 28 (5): 398–421. doi:10.1080/08949468.2015.1085795

- Shomaker, T. 2021. ‘As Japan’s Empty Homes Multiply, Its Laws are Slowly Catching Up.’ Nikkei, 7 June, https://asia.nikkei.com/Life-Arts/Life/As-Japan-s-empty-homes-multiply-its-laws-are-slowly-catching-up.

- Sier, W. 2020. Everybody Educated?: Education Migrants and Rural-Urban Relations in Hubei Province, China. PhD Diss. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam.

- Sier, W. 2021. “Daughters’ Dilemmas: The Role of Female University Graduates in Rural Households in Hubei Province, China.” Gender, Place and Culture 28 (10): 1493–1512. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2020.1817873.

- Sirriyeh, A. 2010. “Home Journeys: Im/Mobilities in Young Refugee and Asylum-Seeking Women’s Negotiations of Home” Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark) 17 (2): 213–227. doi:10.1177/0907568210365667

- Sorace, C., and W. Hurst. 2016. “China’s Phantom Urbanisation and the Pathology of Ghost Cities.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 46 (2): 304–322. doi:10.1080/00472336.2015.1115532

- Stahl, L. 2013. ‘China’s Real Estate Bubble.’ 3 March 2013, CBS 60 Minutes, http://www.cbsnews.com/videos/chinas-real-estate-bubble-the-con-artist-cajunketchup/

- Toh, M. 2021. ‘Ghost Towns’: Evergrande Crisis Shines a Light on China’s Millions of Empty Homes.’ CNN, 15 October, https://edition.cnn.com/2021/10/14/business/evergrande-china-property-ghost-towns-intl-hnk/index.html.

- Verstappen, S. 2021. “Ethnocinematographic Theory: How to Develop Migration Theory Through Ethnographic Filmmaking.” In Visual Methodology in Migration Studies: New Possibilities, Theoretical Implications, and Ethical Questions, edited by Karolina Nikielska-Sekula, and Amandine Desille, 99–116. Cham: Springer.

- Verstappen, S. and W. Sier. 2016. ‘Empty Home’, https://vimeo.com/209590747?share=copy.

- Wang, Y., Y. Li, Y. Huang, C. Yi, and J. Ren. 2020. “Housing Wealth Inequality in China: An Urban-Rural Comparison.” Cities 96: 102428. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2019.102428

- Wang, H., F. Su, L. Wang, and R. Tao. 2012. “Rural Housing Consumption and Social Stratification in Transitional China: Evidence from a National Survey.” Housing Studies 27 (5): 667–684. doi:10.1080/02673037.2012.697548

- Woodworth, M. 2020. “Picturing Urban China in Ruin: “Ghost City”.” Photography and Speculative Urbanization.’ GeoHumanities 6 (2): 233–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2020.1825110

- xx, J. 2016. ‘Gosh’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hTGJfRPLe08.

- Yu, S., R. Mcmorrow, and S.F. Ju. 2021. Evergrande Used Retail Financial Investments to Plug Funding Gaps.’ Financial Times, 21 September, https://www.ft.com/content/0b03d4de-1662-4d30-bcfd-c9bae24fa9cc.

- Zhan, S. 2011. “What Determines Migrant Workers’ Life Chances in Contemporary China? Hukou, Social Exclusion, and the Market.” Modern China 37 (3): 243–285. doi:10.1177/0097700410379482

- Zhang, L. 2010. In Search of Paradise: Middle-Class Living in a Chinese Metropolis. Cornell: Cornell University Press.