INTRODUCTION

In the documentary film Chinese Mayor (大同), the mayor Geng Yanbo is driven by the dream of turning the city of Datong from a polluted industrial town in northern Shanxi province into the most special place in China, a cultural destination (Zhou Citation2015). The price for this ambitious plan is the displacement of 500 000 residents (and the demolition of about 200 000 homes), in order to make space for the reconstruction of the Old City’s fourteenth-century Ming Dynasty walls. The film’s depiction of the dynamics within the city administration provides fascinating insights into how cities in China may become the personal creative projects of their administrators, and how they are often left unfinished as the central government decides to interfere and move administrators around the country. It shows how mayors – as key politicians in the city – often face little predictability when undertaking such projects. What the film does not show is the unprecedented public debate that followed the transformations in Datong. But the documentary does reveal what lies on the other side of the urban facade, namely the subjects of urbanisation: the actual residents who either bought apartments or have been living in illegal residences for a long time and face relocation and uprooting. The logic of land use and capital, as well as the mission of civilising the city through new aesthetics, displaces them without providing any alternative.

The renewal of the city of Datong through the manipulation of heritage, e.g. the creation of pseudo-historical buildings and fictional re-creations (Cui Citation2018), exemplifies many characteristic aspects of Chinese urbanisation. The 12th five-year plan (2011–2015) envisioned the demolition of old and illegally occupied houses and the resettlement of residents to new apartment blocks. This massive campaign significantly impacted the growth, and the face, of Chinese cities. The 13th five-year plan announced in 2015 aimed at a more human-centred form of urbanisation and the migration of rural residents to third-tier cities. We find developments similar to Datong’s throughout China’s territory, from the old town renewal of Kashgar in the very northwest to the revitalisation of lilong neighbourhoods (consisting of lanes with residential housing) in Shanghai. The displacement of inhabitants due to large construction projects has occurred during the construction of landmark buildings in Beijing (e.g. the Bird’s Nest or the Opera House) down to the southwest, during the renewal of Kunming’s inner city (Zhang Citation2006). The power dynamics created by politicians’ will to change and the economic opportunities that arise through urban restructuring have shaped the visual contours of cities in recent decades. The film Chinese Mayor reminds us of various important aspects to consider when attempting to understand diverse urbanisation processes in China. Doing so is the objective of this special issue, whose key conceptual thread is related to the idea of the spectacle.

In line with Woodworth’s (Citation2015) concept of a ‘counter-spectacle’, the articles in this special issue literally look behind and beyond the physical walls of the Chinese city. While our perspective on the ‘spectacle’ is often limited to the image conveyed by urban architecture, the contributions in this issue sharpen our view of two moments in the cycle of the built environment.

On the one hand, three articles analyse the ways in which urban built structures come into being and the atmospheres they convey. The contributions by Ryan McCaffrey/Kiah Rutz, Dennis Zuev/Tim Simpson and Madlen Kobi shed light on the emergence and construction of urban buildings/structure and on the ways in which ‘Chineseness' enters built structures through architectural elements, narratives and historical alignments. It is in these moments, when urban buildings are being renewed and restructured, that actors negotiate the spectacular city. Whether in Hangzhou (McCaffrey & Rutz), Macau (Zuev & Simpson) or Aksu in Xinjiang (Kobi), similar processes of reinventing the Chinese city and transforming ideas into built structures become visible.

On the other hand, the special issue provides insights into the ways in which buildings are being imagined, inhabited and maintained by their residents. Gladys Pak Lei Chong, Martin Minost and Willy Sier/Sanderien Verstappen take us literally behind the facades of new residential constructions. Through ethnographic approaches, they provide intimate glimpses of the everyday appropriation of built structures. We learn about what making home means for residents in Beijing (Pak Lei Chong), Chongqing (Minost) and Wuhan (Sier/Verstappen). In a complementary manner, Federica Mirra provides us with insights into how the visual arts approach Chinese urban spectacles such as architectural copycats, gated communities, and themed towns.

All of these contributions thus extend our perspective on the Chinese city beyond the spectacle. Buildings are not static bystanders; their full potential crystallises through the ideas and practices of the people that make and inhabit them. The contributions in this special issue therefore make visible elements which are often left invisible in approaches to the Chinese city. The structure of this overarching introduction to the special issue is as follows. Firstly, we briefly speak about Chinese urbanism as a visual phenomenon. Secondly, we problematise the concept of the spectacle in relation to displays of modernity in the Chinese urban space. And finally, in the concluding sections we emphasise the need for sensory approaches that move beyond the visual dimension and argue for more nuanced approaches to understanding the visual changes in diverse locales (such as Western and interior China) and the implications of such changes.

CHINESE URBANISM AS A VISUAL PHENOMENON: ARTISTIC IMAGINARIES OF THE CHINESE CITY

While different forms and processes of urban transformation in China have been thoroughly investigated through the lens of urban studies, geography and urban planning, the visual aspect of urbanity in China has received little attention. Indeed, Chinese urbanity as a visual phenomenon, a visualscape (Anzoise, Barberi, and Scandurra Citation2017), with its fragmented, overlapping fabrics of the everyday (DeVerteuil Citation2023), the extremes and sites/sights of the built environment and urban inequality have remained virtually unexamined.

At the same time, a handful of monographs and edited volumes (De Kloet and Scheen Citation2013a; Valjakka and Wang Citation2018; Wang Citation2016) have ventured to explore the imaginaries of the Chinese city through examination of relationships between the arts and urbanisation, visual culture, visual politics and image-ining of Chinese urbanity, attending to the diverse manifestations of art forms in Chinese cities. In Gregory Bracken’s book (Citation2012), aspects of urbanisation in three key Chinese cities – Shanghai, Hong Kong and Guangzhou – are approached through the lens of global ambitions, and cultural and architectural expressions. These three cities have defined the post-colonial geography of the Chinese urban spectacle as global cities, projecting China’s image globally.

Meanwhile De Kloet and Scheen cover diverse embodiments of the imaginary of the Chinese cities – conceptualised as scopic and haptic machines (De Kloet and Scheen Citation2013b) that facilitate representations and artistic urban interventions by art collectives or film-makers – such as the famous visual artwork by Cao Fei, RMB City. De Kloet and Scheen remind us to see urban changes as complex entanglements in which the visual (the spectacle) is just one part of urban living. The spectacle is also very much a front stage display or performance (inhibited by social scripts and norms), in the terms of Erving Goffman’s presentation of self (Citation1956), while the back stage displays informal and unscripted behaviours – inequalities and informal makeshift urban forms that remain tucked away from the public. Yet the inequalities are detectable through juxtaposition (DeVerteuil Citation2023) and a more detailed exploration of the other side of the city as the generator of visual pleasures. This sort of invisibility of certain parts of the city is discussed by Wang (Citation2016), especially in the context of sweeping demolitions in Beijing in preparation for the megaevent – the Olympic games in 2008 – and the urban texture of backstreets and street corners in the shadow of the glittering skyscrapers.

While the interlinkage between the visual and the city has been recognised in previous studies, such as those mentioned above, it calls for continuous critical analysis. Urbanity in China has been approached, among other ways, via analysis of urban interfaces emerging from visual arts practice (Valjakka and Wang Citation2018), cinematic depictions of the city (Braester Citation2010; Zhang Citation2010), a study of artists’ provocative responses to issues of urbanisation (Wang Citation2016), and engagements with the omnipresent Chinese character of chai (拆), used to mark houses to be demolished (Chu Citation2014; Yuet Chau Citation2008; Zhao and Bell Citation2005). Zhao and Bell (Citation2005) also discuss the dramatic scale of demolitions and its symbolic politics of disappearing urban forms.

The character chai is a visual reminder of state authority, and has a revolutionary connotation, promising urban renewal and improvement. The multiple depictions of chai on rows of houses are a striking narrative, similar to graffiti, but more laconic. The process of demolition itself and its scale () caused the emergence of the solitary resistance of dingzihu – iconic nail households that would come to be strikingly juxtaposed against the already-emerging new high-rise condominiums ().

FIGURE 1. Demolition of urban housing and chai as a narrative of transition and the promise of life improvement in Tianjin. Source: Dennis Zuev (2008).

FIGURE 2. Dingzihu as a spectacle of solitary urban resistance in Shanghai. Source: Dennis Zuev (2008).

Valjakka and Wang (Citation2018) suggest that forms of artistic and creative practice in China can be regarded as a form of cultural activism, in which multiple urban interventions raise critical awareness and reshape living conditions. This kind of activism does not challenge the authorities, but instead challenges established perceptions of what urban development is (Valjakka and Wang Citation2018, 17). It could be regarded as a ‘hidden transcript’ or form of resistance (Scott Citation1990).

In her monograph, Wang (Citation2016) deconstructs urbanisation via an examination of the works of various artists, and the transformation of Chinese artistic practice and aesthetics as they move from rural to urban, from traditional mountain/water (shanshui) landscapes to urbanscapes. Graffiti, in particular – a form of urban art (Valjakka Citation2011) that was not a particularly significant part of Chinese visual culture – became an important phenomenon within cities like Hong Kong and Macau (Zhang and Chan Citation2022). Gradually, these cities’ graffiti culture was overtaken by that of big cities in mainland China that followed suit, using graffiti to re-fabricate ruined and decaying urban spaces into something that could be visually consumed by tourists and locals and redistributed further digitally (Zuev Citation2015). In Chongqing’s art district Huangjueping, for example, multi-storey houses along the main road are lavishly decorated with graffiti on their outdoor walls, jostling for a visual upgrade through the display of public art ().

FIGURE 3. Multi-storey apartment houses in Chongqing’s art district Huangjueping and the display of public art within the built fabric of the city. Source: Madlen Kobi (2017).

In the geography of Chinese urban spectacle, Hong Kong occupies a special place. When compared with Beijing and Shanghai, only Hong Kong has received as much attention from visual scholars and filmmakers (e.g. Wong Kar-Wai), and despite being a special administrative region, it does merit attention as a ‘disappearing city’ (Abbas Citation2013). The city bears almost no trace of its past (Bracken Citation2012): the image of the now-vanished Kowloon Walled City was associated with the exotic stereotype of a poorly governed, clandestine Asian slum-city (see Girard and Lambot Citation1993). Kowloon Walled City became the epitome of what it meant to live in an overpopulated, dense urban environment, and was depicted in numerous art works, inspiring the cyberpunk aesthetics of Tokyo-based amusement park and facility Kawasaki Warehouse.

Hong Kong – one of the key global cities, despite its problematic branding (Chu Citation2011) – has also been explored as a visualscape. Its neighbourhoods have been seen through the lens of postcoloniality and urban policy failures (Banerjee Citation2017); and through that of light pollution, with a focus on the resulting tensions between everyday residential lives and the necessity of preserving the iconic nighttime cityscape (Lam Citation2022). A distinctive place in the visualisation of Hong Kong is occupied by the work of Caroline Knowles and Doug Harper (Citation2009), which pairs social-anthropological and photographic discourses, contextualising the lives of British expatriates after transition through the use of documentary black and white photography.

While not always explicitly drawing on visual methodologies, many of the aforementioned contributions to some extent employ visual metaphors, such as that of ‘spectacle'. But they do not tackle the complexity of urban change behind these visual interventions. In the next section, we discuss the concept of spectacle as applied to Chinese cities.

THE SPECTACLE OF THE CHINESE CITY

China’s rise on the global political stage is one of the transformative events of our time and has frequently been associated with its hyper-speed urbanisation (Bracken Citation2012; Campanella Citation2008; Friedmann Citation2005). Representations of Chinese cities worldwide provide a visual sense of the seemingly endless sea of houses rising up to the sky, with very little green space left. Ren (Citation2012, 22) argues that Chinese urbanism has become the manifestation of its economic development and thus aligns with Guy Debord (Citation2014, 11), who wrote that ‘[t]he spectacle is capital accumulated to the point that it becomes images.’ It is not only landmark buildings (such as the Bird’s Nest or the CCTV Tower) that have shaped the image of the Chinese city, but also the endless rows of similar-looking high-rise residential buildings (). As living spaces, they constitute the body of these huge cities, and they persuade us to believe that the ‘images of power’ (Broudehoux Citation2010) are transmitted through physical structures. It is especially through architecture and the built environment, which are again and again represented through visual means, that the Chinese city is known to the outside world. Not only construction, but also the waves of demolitions to make space for new spectacular buildings, have received scholarly attention (Chu Citation2014; Hsing Citation2010; Jiang Citation2015; Ren Citation2014; Yuet Chau Citation2008).

FIGURE 4. ‘Weird’ architecture in Chongqing, with the domination of the vertical urbanscape in the Chinese city. Source: Madlen Kobi (2017).

These approaches highlight that the spectacle is double-sided, with a front stage and a back stage (see above). In recent years, the visual cultural aspects of urbanisation have been eclipsed by scholarly interest in social issues and urban politics (De Kloet and Scheen Citation2013a). Beyond spectacular urbanisation, there is a story about displaced residents and communities, and about environmental pollution, that represents the darker side of the spectacle.

The concepts of spectacle and imaginary have been widely used by urban studies scholars (e.g. Mercer and Mayfield Citation2015; Roast Citation2022; Schrijver Citation2011; Schwenkel Citation2015; Woodworth Citation2015; Wu Citation2004; Wu, Li, and Lin Citation2006), but rarely critically examined by visual studies scholars (Zuev and Bratchford Citation2020). Visual perspectives and the notion of the spectacle provide new imaginative avenues (De Kloet and Scheen Citation2013a), sensitising us to the atmospheric aspects of urban spectacles and attuning us to what remains invisible (Chu Citation2014, 365). Indeed, as Abbas (Citation2013) argues with the case of Hong Kong the speed of appearance and ‘disappearance’ is a new stage of urban spectacle in Chinese cities. Apart from the spectacularity of specific cities or regions, scholars have indirectly addressed other visual aspects of Chinese urbanity such as ‘weird' architecture and exotic urban sights (Lynteris Citation2016).

Architecture studies has looked attentively at the emerging urban forms in China; with its break-neck urbanisation, the country could be enjoyed as a laboratory for urban growth (Mars and Hornby Citation2008) – one where designs are drawn up in days and configurations remain for decades. For an architect, China is a perfect setting for experimenting with utopian visions when clients have inexhaustible funds. At the same time, it can be subject to political supervision, which takes form, for example, of reprimands for excessively ‘weird' architecture (Zuo Citation2021). One common trope, the excess in visual appearance and the rise of weird architecture in China, can be seen in urban developments that seek to imitate non-Chinese architectural forms. Roast (Citation2022), in his visual analysis of weird architecture in Chongqing, shows how the city’s vertical topography combines with its housing and transportation planning and noted celebrity city ambitions to produce ‘weird' aesthetic forms, such as ‘horizontal skyscrapers’. He suggests that vertical density in Chongqing and its extreme vertical architecture serves to create ‘luxified skies’ (Graham Citation2015).

The vertical forms of the built environment can align with the spiritual, economic and social power of a place (Bratchford and Zuev Citation2023) and are intricately linked to displays – and the spectacle – of modernity in China, which we will discuss in the next section.

THE DISPLAY OF CHINESE MODERNITY ON THE URBAN STAGE

Since the 1980s, Chinese society has undergone significant social, economic, political, and cultural transformations which have left observable traces in the urban landscape in many ways. The former socialist city, composed of six-storey residential buildings and organised in work units (danwei), by the 1990s was replaced by a city where economic means started to determine one’s residential neighbourhood. Multi-lane highways filled with cars from all over the world have displaced the bicycle masses so characteristic of Chinese cities until the 1990s. And since the late 2000s, digital technologies have started to dominate everyday lives, from shopping to mobility to dating. Personal exchanges that formerly took place in the proximity of one’s home are now organised through digital means.

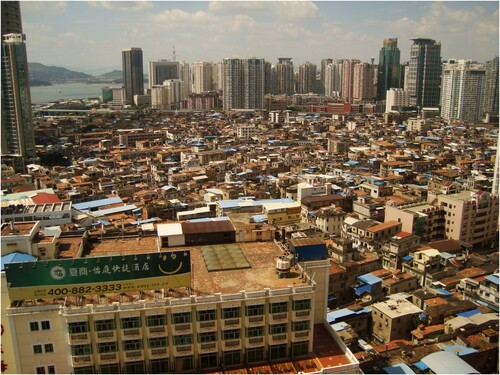

A visual approach to the city combines the visible with the invisible aspects of the city. We underline Ma’s (Citation2002, 1558–1559) idea that ‘[…] urban landscape is the physical embodiment of the technology, culture, and ideology of a city. As a major constitutive element of cities, urban landscape articulates, reflects, and signifies the dominant values and mode of social and economic reproduction of the time. As representations of culture and ideology, however, the hidden and symbolic meanings of the forms of the urban landscape are not always apparent.’ In order to make these symbolic and everyday meanings of the landscape visible, the backbone of the articles in this special issue has been formed by talking to and engaging with Chinese residents. Because urban territories are constantly changing, this change must be studied in relation to, and together with, the environments and living conditions with which they coevolve. Citizens’ urban realities also depend on the kind of housing and urban district in which they live – for example, whether they dwell in high- or low-rise buildings affects their visual perception and everyday engagement with the city ().

FIGURE 5. Xiamen’s urbanscape, characterised by low-rise and high-rise dwelling realities coexisting next to one another. Source: Madlen Kobi (2012).

The factors that have shaped the visual appearance of the Chinese city in the post-reform period are manifold, ranging from political power embodied in the built environment to the influx of global ideas of urbanity. This special issue explores the coexistence of different urban atmospheres in Chinese cities, and in particular the mutual influence of forms of modernity, on the one hand, and more traditional Chinese urban structures and city-making practices, on the other. Modernity in Chinese cities is a place-specific reality that manifests in urban practices of renewal and the reimagination of urban spaces (Zhang Citation2006). But it also manifests in the naming of residential districts with words such as ‘international', ‘new’ or ‘green’, in an attempt to align built structures in Chinese cities to global forms of housing (Ren Citation2011, 96; Citation2012). The concept of ‘spectacle' helps elucidate this rise of a new urban aesthetic in Chinese cities in the last three decades. As a realm to envision and experience the city, the concept of spectacle allows us not only to reflect on ongoing changes, but to consider Chinese visual traditions that are grounded in the philosophical and aesthetic foundations of Chinese art. Traditional artistic concepts such as shanshui are, for example, reconsidered in contemporary Chinese urban architecture (Ma and MAD architects Citation2015; Mirra Citation2019).

At the same time, despite the potency of the concept of spectacle, we realise that it is possible to go beyond its visual dimension, and in the next section we emphasise how the concept of spectacle can open up other senses.

SENSORY URBAN APPROACHES BEYOND THE VISUAL

The spectacle as a visual experience is perhaps the easiest sense to be conveyed in an academic journal, even if images do not replace the on-site experience of a cityscape. Considering the spectacle of the Chinese city, however, also means being attentive to our non-visual senses: listening to soundscapes (Bivouac Recordings Citation2022; Feld Citation1996; Jug and Kobi Citation2021), tasting (e.g. through food, see Cesaro Citation2000; Kaufmann Citation2011), smelling, and touching are complementary in assessing cityscapes through fieldwork. In this issue, the contributions provide glimpses into Chinese residences in gated communities (Minost) and the apartments of different socio-economic groups in Beijing (Pak Lei Chong), and in the essay related to the cover photo Zuev and Simpson speak of the construction site as the continuous reminder of material re-fabrication and manufacturing. But we also look into the ‘empty homes’ that are not as empty as their denomination would suggest: Sier and Verstappen show that the second homes that mostly migrants buy in Chinese suburban areas are empty neither in terms of their interior furniture nor in terms of the imagined ideas around them, even if most of the time they are not being used. Switching to the outside of buildings, Mirra engages with the ways in which artists convey urban sensory experiences to spectators. Through artists’ work, she writes, ‘one would experience the sensation of leaving the physical reality to enter other imaginary worlds.’

From an architectural perspective, we get insights into the appearance of Hangzhou’s inner-city area during a renewal period before the eleventh annual G20 Summit took place in 2016 (Kiah and Rutz). Hangzhou’s streets and roadsides at that time seemed somewhat messy, with construction activities and waste hidden behind billboards. A fascination for the transformations of cityscapes also plays a significant role in two other contributions: Zuev and Simpson engage with affective atmospheres in Macau, expanding our senses beyond the visual to get a sense of the spectacle from an inhabitant’s perspective. In a similar vein, Kobi takes us on a walk through the city of Aksu in Xinjiang, where she bodily encountered the city and discussed sensing and ethnic perceptions of cityscapes with residents while traversing the sites. The objective of this special issue is to analyse and deconstruct the elusive nature of the sublime atmosphere of Chinese cities. It brings into sight its scale and its unique spatial ordering, but also its cultural particularity. Using the visual perspective can be a fruitful way to approach the affective content of the urban atmosphere (Latka Citation2019).

As urban atmospheres consist of elemental forces, such as air and water, in the final part of this section we briefly touch upon the visual importance of elements in the city, such as pure air and blue skies. These are important indicators not just of liveability, but also the progress of the Chinese state in speedily discarding the image of the polluted developing country plagued by ever-present haze or smog (Ahlers and Hansen Citation2017). The concept of ‘Apec blue sky’, which emerged before the APEC meeting in Beijing in 2014, came to denote a wonderful but also fleeting state of the urban sky. Through rigorous political control measures to reduce carbon emissions from factories and traffic, the sky over the capital turned from grey to blue. It painfully hinted at the regional inequalities between cities in China, where some residents can enjoy a view of blue skies (namely those in Beijing, Shanghai or Shenzhen, where important world events take place) and others in the interior or ‘smokestack’ cities who cannot because they suffer from the consequence of industrial production that had been established or transferred there.Footnote1 While air and blue sky became key contestation grounds for all categories of Chinese citizens, research has focused on the reactions of the middle classes (Ahlers and Shen Citation2018; Li and Tilt Citation2018). The pure air in the city and access to it became the object of artistic interrogation, leading to a case of creative coping with air pollution. In Hong Kong, for instance, blue skyline banners/’clean-air displays’ were provided to draw attention to the issue of environmental degradation and the ‘coping' with the smog as a fantasy, simultaneously providing a more aesthetically pleasing background to (mostly mainland) tourists taking pictures in front of the skyscrapers. They also became a part of the everyday visual landscape for residents performing their routine practices, such as jogging.Footnote2

The poor air quality and grey skies over cities are crucial in our visual analysis of the spectacle, as the image of the polluted capital negatively impacts the reputation and image of China. And the absence of blue sky has become one of the major push factors prompting many affluent Chinese to seek urban residence elsewhere. These are just some of the costs of the economic miracle.

DETRIMENTAL EFFECTS OF THE SPECTACLE

The Communist Party has demonstrated its power through the spectacular transformation of Chinese cities. But the shining facades of the new high-rise buildings are built on top of a number of detrimental effects that emerged in the post-reform period. Broudehoux (Citation2010, 53) suspects that spectacular architecture is a way to distract the public’s attention from the high level of political control under which they live. It has helped to ‘divert public attention away from the shortcomings of rapid urban redevelopment’ (Broudehoux Citation2010, 58). One of these shortcomings is the above-mentioned relocation of urban residents from their homes, which have been demolished to make way for the construction of new buildings. But the environmental consequences are also huge. While urban atmospheres in many Chinese cities are heavily polluted (Ahlers and Hansen Citation2017; Jing Citation2015), the extraction of resources to sustain the building of new structures transforms rural landscapes through the opening of mines, the excessive need for water, and the externalisation of the ecological effects of urbanisation. One final detrimental effect is the surveillance and vulnerability to disease of dense living areas, which has become apparent since the 2010s, particularly with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Looking at Chinese cities during the pandemic allows us to see how the urban context has become an important stage for ‘economies of appearance’ (Tsing Citation2000) in China, where COVID-19 management within the ‘zero-Covid' policy often meant draconian lockdowns (e.g. in Shanghai 2022). The zero-Covid policy also translated into heightened surveillance and the continuous testing of the whole population in an attempt to generate an exemplary hygienic city image in line with the wider Chinese national project of health surveillance as a constituent of the ‘hygienic modernity’ narrative (Rogaski Citation2004). One could criticise this as an attempt at hygienic urbanism – which is one of the crucial frameworks for understanding the logic of the zero-Covid policy. The logic becoming a part of the sanitary sci-tech spectacle and the essence of the modern Chinese city as a civilising machine for educated and hygienically ordered subjects (see Cartier Citation2016). This hygienic spectacle involved the segregation of neighbourhoods and repetitive vernacular rituals of hygienic optimisation, such as elevator disinfections, sprinkling sanitiser on the surface of the city streets, wiping surfaces and disinfecting buses, all performed by an army of employees. Although the zero-Covid policy has now been scrapped, it provided a window of opportunity to observe Chinese urban governance in times of crisis, and the violent implications of hygienic urbanism – as demonstrated by lockdowns in Shanghai in 2022.

In the next section we emphasise that to properly grasp urban China today, we need more nuanced approaches to understanding the visual changes that have occurred in diverse locales, as well as the implications of such changes.

THE CHINESE CITY BEYOND EASTERN CHINA: RE-FABRICATING URBAN SPECTACLE IN CHINA’S NORTH WEST

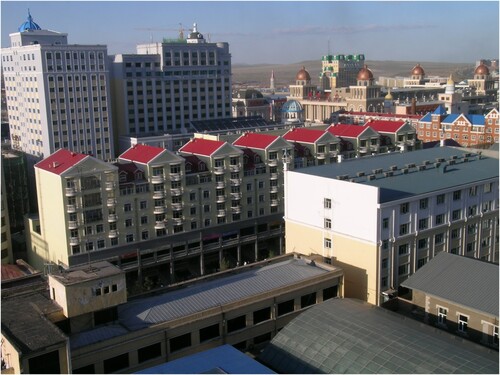

While the emerging new urban fabric of coastal cities like Shanghai, Hong Kong, Shenzhen and Guangzhou, as well as the capital Beijing, has been explored extensively, urban transformations and city-making practices in the interior regions, beyond the first-tier cities, have been neglected (Kobi Citation2016; Zuev Citation2018). We argue that the spectacle of Chinese urbanity is sometimes even more pronounced in border regions where urban development helps mark state territory (Kobi Citation2016; Szadziewski, Mostafanezhad, and Murton Citation2022; Woodworth Citation2017; Yeh Citation2013). Piper Gaubatz has examined the transformation of urban form in China, including in the Northwest, since the 1990s (Citation1996), and has recently published studies that explore changes in public urban squares in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia (Citation2021) and new public spaces in Xining, Qinghai (Citation2008). She suggests that public spaces such as squares, despite having a political function, have been re-fabricated (materially) and re-invented to accommodate multiple groups of residents and diverse functions. The central square in Hohhot, for example, was previously a boring, paved, empty space and has recently been transformed into a lively, green, social space, a metamorphosis from ‘concrete slab to park’ (Gaubatz Citation2021). Such studies of urban changes in the Northwest remind us of radical differences and disparities between Chinese cities and regions.

The development of border cities is also highly uneven as some cities benefit more from cross-border trade and business than others. Manzhouli () and Hohhot in the Northeast, Khorgos and Kashgar in the Northwest, Ruili in the Southwest, and Zhuhai at the border with Macau are cities whose economies thrive on the legal, semilegal (parallel) and illegal trade with neighbouring countries (Alff Citation2017; Su and Miao Citation2022). However, they are rarely discussed in academic literature on urbanisation in China. Studying these and other cities that do not appear in international headlines – such as Chengdu, Harbin, Lanzhou, Wuhan, Nanjing and Xian – expands our knowledge of the particularity of the Chinese city, and draws attention to the importance of considering the local urban politics.

FIGURE 6. The staggering growth of the border town of Manzhouli, located on the western branch of the former Chinese Eastern Railway, is a reminder of decades of lucrative border trade with Russia. Source: Dennis Zuev (2008).

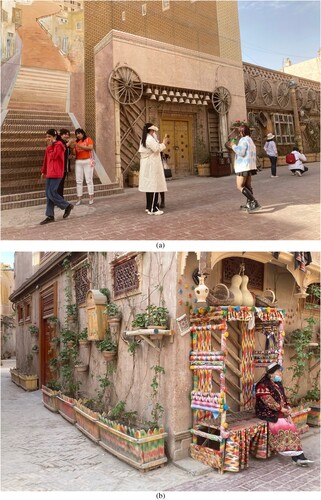

Despite the contested topic of urban developments in Xinjiang, only a few scholars in the last decade have ventured beyond the politically engaged discourse on ethnic contradictions and the politics of control to understand the changing appearance of cities there. While we have one article in this special issue concerned with the spectacle of the Chinese city in the Uyghur homelands (Kobi Citation2023), we would like to offer a vignette here that accounts for the radical transformations in the city of Kashgar in the southwest corner of Xinjiang. Kashgar is an ancient Silk Road city in Central Asia, close to neighbouring Afghanistan, Pakistan and the former Soviet republics of Central Asia. It is also the city with the highest percentage of Uyghur inhabitants in Xinjiang.

With this vignette we stress the conceptual importance of looking at Chinese cities not with the Western or ‘tourist gaze’ (Szadziewski, Mostafanezhad, and Murton Citation2022; Urry Citation1990), but by considering the perspectives of the local urban politics of control, development, branding and heritage or culture. The dialogue with Chinese scholars regarding the local urban politics is often missing in the Western literature (Hein and Foster Citation2023; Svensson and Maags Citation2018). At the same time, some studies by Chinese authors insightfully suggest that the new search for cultural identity in urban China is born out of a mix of reality and fantasy, which may pose a challenge to existing theories of authenticity (Guo Citation2023).

A short walk from Chini Bagh Hotel past the crumbling, century-old former wooden building of the British Consulate leads to the remaining chunk of the old Kashgar. The winding alleys with earthen walls, houses with glass covered inner courtyards, ornate wooden gates and doorknockers, with metallic plates where ‘Ideal Family’ or ‘Exemplary Household’ is inscribed in the Uyghur and Chinese languages. Many of these houses have a lock on the gates and there are no longer any lights on at night. Some look long abandoned and are crumbling, the paper notice announcing that the house had been vacant for months. Many of the inhabitants have moved out or have been moved out. It seems that they have left the houses in a rush. Some say they have moved to live in tall building blocks or even away from Kashgar.

Sand dust is the element that shapes life in Central Asian cities. The dust is abrasive and occlusive by nature – it shapes, softens, obscures the sky, keeps things away from the sight. The yellow, sandy, dusty streets are adorned by rows of plants that give life to them. In some alleys, one can still see what reminds of the glory of the past. In the night, the smoke from kebab stands fills the air, the nan bread stalls and fruit and vegetable vendors lining the streets. (Kashgar, April 2023)

According to many Western visitors and Xinjiang residents as well, Kashgar old town lost much of its former magic and glory (becoming practically soulless) due to the disappearance of the lively atmosphere within the narrow, winding alleyways that contained a buzzing life of artisans, shops and restaurants. The causes of these changes are ‘bulldozing politics’ and ubiquitous surveillance culture. As we suggested earlier, this concept of bulldozing politics – and that of the crane and pile driver politics that follows – can be applied to Kashgar old town in a similar vein as to Beijing, Tianjin ( and ) and Shanghai, where whole neighbourhoods of colonial or traditional Chinese dwellings have been bulldozed to make space for newer buildings.

The latest observations by the authors allow to conjecture that while Kashgar old town’s layout is gone, it did not disappear as radically as the erased Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong. Nor did Kashgar’s old town become a ‘fake’ neighbourhood, as the locals still live there and children play on the street; nan bread is still baked and sold. Instead, the old town’s layout has been made more readable and has been re-aestheticised for domestic tourist consumption. In certain parts, this has involved ‘weird' interventions similar to the weird architecture in Chongqing that we mentioned in an earlier section. Weird in Kashgar is found in the multiple collections of utensils hanging on the walls, the murals imagining the ancient city, swinging benches, the green plants trying to add a bit more verdancy to the walls in a city that is constantly dealing with sandstorms and dry weather conditions. It is a pop-up selfie-set with the living residents as actors within the scenery (see diptych of (a,b)). Kashgar exemplifies the fate of many other cities across China and across the globe that have been either completely bulldozed or re-fabricated (e.g. via reformulation of the street layout) to appeal to tourists, and/or to facilitate better ‘seeing by the state’ (Scott Citation1998), and/or to allow the authorities to keep face in the event of natural disasters (earthquakes).

FIGURE 7. Kashgar old town, still intact but with new visual interventions. A re-fabricated spectacle of a Silk Road city for tourist consumption. (a) selfie-sets, streets for taking pictures – imaginary old town in murals and in collections of objects, (b) Urban furniture for tourists and locals. Source: Dennis Zuev, Kashgar 2023.

Since the mid 2010s, cities in Xinjiang have undergone a visual and architectural transformation. Here the political climate of surveillance, ethnic segregation and an active police state have contributed to the formation of new local affective atmospheres (which differ across cities in the North and South). With our vignette and analysis, we were concerned with the transformation of the old town’s structures. But during our short visit to the town, many topics could not be discussed with locals and many questions have been left unanswered. Without doubt, Kashgar’s old town has been touristified with Chinese characteristics, and it follows a template of a ‘hygienic’, organised, ‘civilized’, suzhi elevating (Grose Citation2021) and safe old town.

CONCLUSIONS

In this introduction, and through multiple articles rooted in distinctive urban settings, we wish to underline the importance of applying the notion of spectacle to changes in, and transformations of, Chinese cities. It is a notion that encourages us to look at the scale of these cities’ destruction and restructuring. Visual scholars of Chinese urbanism would benefit from looking at Chinese cities as continuously transforming entities into which elements of shanzhai (or fakeness) – see (De Kloet and Scheen Citation2013b) and Mirra (this issue) – but also authenticity (Hein and Foster Citation2023) are being integrated. This continuous elaboration of the urban fabric gives rise to what we might call a continuously refabricated spectacle (as we briefly demonstrate in our closing vignette on Kashgar’s old town), where ideological and material meanings are not as they were originally. Expecting that the city will always remain the same in China or elsewhere is inappropriate; visual scholars should therefore follow and document the ongoing process of refabrication – whether this is related to specific facets, such as the aesthetics of the inner-city core, to housing estates, to urban infrastructure hubs or indeed to the intricate relationship between, and diversity of, different urban forms in the same city.

Another point that we wish to convey is that the notion of spectacle – as it relates to the visual appearance of cities, as well as to related changes in the urban experience – requires further unpacking. Our concluding vignette and related references also highlight the dearth of studies on the Chinese urban interior that lies beyond the well-documented cities. Without critical documentation of changes in these cities, we may lose an important basis for understanding the dynamics of (uneven) regional politics in China. Reference to other visual documents, such as films, can perhaps help recover the missing pieces. We are convinced that integrating the spectacular transformation of different localities into recent debates will enrich the discussion on visual approaches to the city. Therefore, this special issue not only provides perspectives on Beijing (Pak Lei Chong) and Shanghai (Mirra), but also includes articles on Wuhan (Sier/Verstappen), Chongqing (Minost), Macau (Zuev/Simpson), Hangzhou (Rutz/McCaffrey) and Aksu, the Uyghur city in the Northwest (Kobi). Talking about ‘the Chinese city’ means finding a common ground on which to discuss these highly diverse and localised processes and experiences of the urban spectacle.

Related to this is also the importance of further studies about the urban aesthetics of newly emerging second- and third-tier cities, e.g. Xiongan or Hengqin, which are experiments in administration, regional governance, and the movement of financial capital and human resources. They may become generic ‘shanzhai’ cities similar to Pudong (De Kloet and Scheen Citation2013b) or ghost cities (Shepard Citation2015). However, the Chinese dialectics of copying architectural forms from elsewhere, as has been shown in this issue (Mirra) and beyond (Guo Citation2023; Pendrakowska Citation2023), needs to be examined more closely. In some cases, the past can be transformed into a theme park; in others, embracing artificiality allows for the aesthetic infusion that inspires imagination.

After numerous studies on massive urban transformations in Chinese cities, it remains to us to question the image of the future city that the Chinese state (along with Western architects) and Chinese people are envisioning. What are the visual indicators of a ‘civilized city’, as promoted in the urban re-fabrication of Kashgar? How does such a city relate to what we can already see (see ) in a random photo taken from the high-speed train between Guangzhou and Zhuhai: modernist yet low-rise, diverse urban forms, green grass, blue sky and water, a utopian image that is actually already there? What lies behind this? Is it the ideal of a single-family home with a garden so prominent among house buyers in Europe and Northern America? Are such living conditions achievable in other parts of China and not just in the well-off Guangdong province? To learn what the future spectacular Chinese city will look like, we may need to examine the scale of destruction as much as the scale of construction and the invisible backstage performances behind it.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dennis Zuev

Dennis Zuev is the Head of the Department of History and Heritage at University of St. Joseph, Macau and the coordinator of the Research Lab for Cultural Sustainability. He is also a senior researcher at CIES-ISCTE, IUL, Portugal and member of Urban Transitions Hub, University of Lisbon. He is the author of Urban Mobility in Modern China: The growth of the E-Bike (Palgrave, 2018). His recent co-edited volume with Gary Bratchford is “Vision and Verticality. A Multidisciplinary Approach” (Palgrave, 2024).

Madlen Kobi

Madlen Kobi is a social anthropologist and assistant professor at the Social Anthropology Unit, Department of Social Sciences, University of Fribourg, Switzerland. She has conducted extensive ethnographic research in China since 2009 (particularly in Beijing, Chongqing, and different cities in northwest China) and her research and teaching foci are architecture, circular economy, infrastructure, waste, urban political ecology and material culture.

Notes

1 China's far west poised to overtake Hebei in a “most polluted” list https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/9017-China-s-far-west-poised-to-overtake-Hebei-in-a-most-polluted-list (accessed July 12 2023).

2 Hazy Skies in Hong Kong? Just Pose with a Fake Skyline. https://www.theatlantic.com/china/archive/2013/08/hazy-skies-in-hong-kong-just-pose-with-a-fake-skyline/278997/ (accessed July 12 2023).

REFERENCES

- Abbas, Ackbar. 2013. Hong Kong. Culture and the Politics of Disappearance. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Ahlers, Anna L., and Mette Halskov Hansen. 2017. “Air Pollution: How Will China Win Its Self-Declared War Against It?” In Routledge Handbook: China’s Environmental Policy, edited by Eva Sternfeld, 83–96. London: Routledge.

- Ahlers, Anna L., and Yongdong Shen. 2018. “Breathe Easy? Local Nuances of Authoritarian Environmentalism in China’s Battle Against Air Pollution.” China Quarterly 234:299–319. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741017001370.

- Alff, Henryk. 2017. “Trading on Change. Bazaars and Social Transformation in the Borderlands of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Xinjiang.” In The Art of Neighbouring. Making Relations Across China’s Borders, edited by Martin Saxer, and Juan Zhang, 95–121. Asian Borderlands. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Anzoise, Valentina, Paolo Barberi, and Giuseppe Scandurra. 2017. “City Visualscapes, an Introduction.” Visual Anthropology 30 (3): 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/08949468.2017.1296284.

- Banerjee, Bidisha. 2017. “Looking Beyond ‘Buildings of Chrome and Glass’: Hong Kong’s ‘Uncanny Postcoloniality’ in Photographs of Tin Shui Wai.” Visual Studies 32: 60–69.

- Bivouac Recording. 2022. “‘60 Min Cities’ Series.” Accessed May 29, 2023. https://soundcloud.com/bivouacrecording/sets/60-minute-cities.

- Bracken, Gregory, ed. 2012. Aspects of Urbanization in China. Shanghai, Hong Kong, Guangzhou. Vol. 6. Publications Series. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Braester, Yomi. 2010. Painting the City Red: Chinese Cinema and the Urban Contract. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Bratchford, Gary, and Dennis Zuev. 2023. “Vision & Verticality: A Visual Sociology of the Sky.” In Vision and Verticality. A Multidisciplinary Approach, edited by G. Bratchford and D. Zuev, 1–15. Cham: Palgrave.

- Broudehoux, Anne-Marie. 2010. “Images of Power. Architectures of the Integrated Spectacle at the Beijing Olympics.” Journal of Architectural Education 63 (2): 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1531-314X.2010.01058.x.

- Campanella, Thomas J. 2008. The Concrete Dragon. China’s Urban Revolution and What It Means for the World. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Cartier, Carolyn. 2016. “A Political Economy of Rank: The Territorial Administrative Hierarchy and Leadership Mobility in Urban China.” Journal of Contemporary China 25 (100): 529–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2015.1132771.

- Cesaro, Cristina M. 2000. “Consuming Identities: Food and Resistance Among the Uyghur in Contemporary Xinjiang.” Inner Asia 2:225–238. https://doi.org/10.1163/146481700793647850.

- Chu, Stephen Yiu-wai. 2011. “Brand Hong Kong: Asia's World City as Method?” Visual Anthropology 24 (1-2): 46–58.

- Chu, Julie. 2014. “When Infrastructures Attack: The Workings of Disrepair in China.” American Ethnologist 41 (2): 351–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12080.

- Cui, Jinze. 2018. “Heritage Visions of Mayor Geng Yanbo.” In Chinese Heritage in the Making: Experiences, Negotiations and Contestations, edited by C. Maags and M. Svensson, 223–244. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- De Kloet, Jeroen, and Lena Scheen. 2013a. Spectacle and the City. Chinese Urbanities in Art and Popular Culture. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- De Kloet, Jeroen, and Lena Scheen. 2013b. “Pudong: The Shanzhai Global City.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 16 (6): 692–709. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549413497697.

- Debord, Guy. 2014. The Society of the Spectacle. Translated and Annotated by Ken Knabb. Berkeley, CA: Bureau of Public Secrets.

- DeVerteuil, Geoffrey. 2023. “Juxtaposition and Visualising the Middle Ground in the Unequal City.” Visual Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2023.2217171.

- Feld, Steven. 1996. “Waterfalls of Songs: An Acoustemology of Place Resounding in Bosavi, Papua New Guinea.” In Senses of Place, edited by Steven Feld, and Keith H. Basso, 91–135. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

- Friedmann, John. 2005. China’s Urban Transition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gaubatz, Piper. 1996. Beyond the Great Wall: Urban Form and Transformation on the Chinese Frontiers. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Gaubatz, Piper. 2008. “New Public Space in Urban China. Fewer Walls, More Malls in Beijing, Shanghai and Xinin.” China Perspectives 4 (4): 72–83. https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.4743.

- Gaubatz, Piper. 2021. “New China Square: Chinese Public Space in Developmental, Environmental and Social Contexts.” Journal of Urban Affairs 43 (9): 1235–1262. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2019.1619459.

- Girard, Greg, and Ian Lambot. 1993. City of Darkness. Life in Kowloon Walled City. Surrey: Watermark Publications.

- Goffman, Erving. 1956. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Doubleday Publishing.

- Graham, Stephen. 2015. “Luxified Skies.” City 19 (5): 618–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1071113.

- Grose, Timothy A. 2021. “If You Don’t Know How, Just Learn: Chinese Housing and the Transformation of Uyghur Domestic Space.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44 (11): 2052–2073. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1789686.

- Guo, B. 2023. “Critical Chinese Copying as an Interrogation of the Hegemony of Authenticity.” In Understanding Authenticity in Chinese Cultural Heritage, edited by A. Hein and C. J. Foster, 123–138. London: Routledge.

- Hein, A., and C. J. Foster. 2023. “Introduction. Understanding Authenticity in Chinese Cultural Heritage.” In Understanding Authenticity in Chinese Cultural Heritage, edited by A. Hein and C. J. Foster, 1–18. London: Routledge.

- Hsing, You-Tien. 2010. The Great Urban Transformation. Politics of Land and Property in China. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jiang, Jiehong. 2015. An Era Without Memories: Chinese Contemporary Photography on Urban Transformation. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Jing, Chai. 2015. Under the Dome. Accessed May 29, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T6X2uwlQGQM.

- Jug, Katja, and Madlen Kobi. 2021. “Biopolitics of Heating Infrastructures in Chongqing (China).” Roadsides 6:62–71.

- Kaufmann, Lena. 2011. Mala Tang: Alltagsstrategien ländlicher Migranten in Shanghai. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Knowles, Caroline, and Douglas Harper. 2009. Hong Kong: Migrant Lives, Landscapes, and Journeys. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kobi, Madlen. 2016. Constructing, Creating, and Contesting Cityscapes. A Socio-Anthropological Approach to Urban Transformations in Southern Xinjiang, People’s Republic of China. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Kobi, Madlen. 2023. “Building Shanghai in the Borderlands. A Visual Approach to the Restructuring of the Uyghur City in Xinjiang.” Visual Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2023.2197419.

- Lam, Yee-Man. 2022. “A Study of Light Pollution Discourse in Hong Kong.” Visual Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2022.2060302.

- Latka, Thomas. 2019. “Philosophy of the Atmospheric Turn.” In Atmospheric Turn in Culture and Tourism: Place, Design and Process Impacts on Customer Behaviour, Marketing and Branding (Advances in Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, Vol. 16), edited by M. Volgger and D. Pfister, 15–30. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Li, X., and Brian Tilt. 2018. “Perceptions of Quality of Life and Pollution among China's Urban Middle Class: The Case of Smog in Tangshan.” The China Quarterly 234:340–356. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741017001382.

- Lynteris, Christos. 2016. “The Prophetic Faculty of Epidemic Photography: Chinese Wet Markets and the Imagination of the Next Pandemic.” Visual Anthropology 29 (2): 118–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/08949468.2016.1131484.

- Ma, Laurence J. C. 2002. “Urban Transformation in China, 1949 – 2000: A Review and Research Agenda.” Environment and Planning A 34 (9): 1545–69.

- Ma, Yansong, and MAD Architects. 2015. Shanshui City. Zürich: Lars Müller.

- Mars, Neville, and Adrian Hornsby, eds. 2008. The Chinese Dream. A Society Under Construction. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers.

- Mercer, David, and Prashanti Mayfield. 2015. “City of the Spectacle. White Night Melbourne and the Politics of Public Space.” Australian Geographer 46 (4): 507–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2015.1058796.

- Mirra, Federica. 2019. “Reverie Through Ma Yansong’s Shanshui City to Evoke and Re-Appropriate China’s Urban Space.” Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art 6 (2): 393–413. https://doi.org/10.1386/jcca_00013_1.

- Pendrakowska, P. P. 2023. “Can a Copy Deliver an Authentic Experience? An Interdisciplinary Approach to Fieldwork Conducted in Southeast China.” In Understanding Authenticity in Chinese Cultural Heritage, edited by A. Hein and C. J. Foster, 139–154. London: Routledge.

- Ren, Xuefei. 2011. Building Globalization. Transnational Architecture Production in Urban China. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

- Ren, Xuefei. 2012. “Green’ as Spectacle in China.” Journal of International Affairs 65 (2): 19–30.

- Ren, Xuefei. 2014. “The Political Economy of Urban Ruins: Redeveloping Shanghai.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38 (3): 1081–1091. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12119.

- Roast, Asa. 2022. “Towards Weird Verticality: The Spectacle of Vertical Spaces in Chongqing.” Urban Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980221094465.

- Rogaski, Ruth. 2004. Hygienic Modernity. Meanings of Health and Disease in Treaty-Port China. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Schein, Louisa. 2006. Minority Rules: The Miao and the Feminine in China’s Cultural Politics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Schrijver, Lara. 2011. “Utopia and/or Spectacle? Rethinking Urban Interventions Through the Legacy of Modernism and the Situationist City.” Architectural Theory Review 16 (3): 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/13264826.2011.621545.

- Schwenkel, Christina. 2015. “Spectacular Infrastructure and Its Breakdown in Socialist Vietnam.” American Ethnologist 42 (3): 520–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12145.

- Scott, James. 1990. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven, CT: Yale Univesity Press.

- Scott, James C. 1998. Seeing Like a State. How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Shepard, Wade. 2015. Ghost Cities of China: The Story of Cities Without People in the World’s Most Populated Country. Asian Arguments. London: Zed Books.

- Su, Xiaobo, and Yi Miao. 2022. “Border Control. The Territorial Politics of Policy Experimentation in Chinese Border Cities.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 46 (4): 522–541. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.13079.

- Svensson, Marina, and Christina Maags. 2018. ”Mapping the Chinese Heritage Regime: Ruptures, Governmentality, and Agency.” In: Chinese Heritage in the Making: Experiences, Negotiations and Contestations, edited by M. Svensson and C. Maags, 11–38. Amsterdam: University Press.

- Szadziewski, Henryk, Mary Mostafanezhad, and Galen Murton. 2022. “Territorialization on Tour: The Tourist Gaze Along the Silk Road Economic Belt in Kashgar, China.” Geoforum 128:135–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.12.010.

- Tsing, Anna L. 2000. “Inside the Economy of Appearances.” Public Culture 12 (1): 115–144. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-12-1-115.

- Urry, John. 1990. The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies. London: SAGE.

- Valjakka, Minna. 2011. “Graffiti in China – Chinese Graffiti?” The Copenhagen Journal of Asian Studies 29 (1): 31–61.

- Valjakka, Minna, and Meiqin Wang. 2018. Visual Arts, Representations and Interventions in Contemporary China. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Wang, Meiqin. 2016. Urbanization and Contemporary Chinese Art. London: Routledge.

- Woodworth, Max D. 2015. “From the Shadows of the Spectacular City: Zhang Dali’s Dialogue and Counter-Spectacle in Globalizing Beijing 1995–2005.” Geoforum 65:413–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.02.005.

- Woodworth, Max. 2017. “Landscape and the Cultural Politics of China’s Anticipatory Urbanism.” Landscape Research 43 (7): 891–905. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2017.1404020.

- Wu, Fulong. 2004. “Transplanting Cityscapes: The Use of Imagined Globalization in Housing Commodification in Beijing.” Area 36 (3): 227–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0004-0894.2004.00219.x.

- Wu, Yifei, Xun Li, and George C.S. Lin. 2006. “Reproducing the City of the Spectacle. Mega-Events, Local Debts, and Infrastructure-Led Urbanization in China.” Cities 53:51–60.

- Yeh, Emily T. 2013. Taming Tibet: Landscape Transformation and the Gift of Chinese Development. Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Yuet Chau, Adam. 2008. “An Awful Mark. Symbolic Violence and Urban Renewal in Reform-Era China.” Visual Studies 23 (3): 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725860802489882.

- Zhang, Li. 2006. “Contesting Spatial Modernity in Late-Socialist China.” Current Anthropology 47 (3): 461–476. https://doi.org/10.1086/503063.

- Zhang, Yingjin. 2010. Cinema, Space, and Polylocality in a Globalizing China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Zhang, H., and B. H.-S. Chan. 2022. “Differentiating Graffiti in Macao: Activity Types, Multimodality and Institutional Appropriation.” Visual Communication 21 (4): 560–580. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357220966737.

- Zhao, Xudong, and Duran Bell. 2005. “Destroying the Remembered and Recovering the Forgotten in Chai. Between Traditionalism and Modernity in Beijing.” China Information 19 (3): 489–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203X05058507.

- Zhou, Hao. 2015. The Chinese Mayor (Original Title: Datong). Zhaoji Films.

- Zuev, Dennis. 2015. “Cities, Visual Consumption of.” In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Consumption and Consumer Studies, edited by Daniel Thomas Cook and Michael Ryan, 79–81. London: John Wiley & Sons.

- Zuev, Dennis. 2018. Urban Mobility in Modern China. The Growth of the E-Bike. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zuev, Dennis, and Gary Bratchford. 2020. Visual Sociology. Practices and Politics in Contested Spaces. Palgrave Pivot. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zuo, Mandy. 2021. “Chinese Government Bans Those ‘Weird Buildings’ that Xi Jinping Can’t Stand.” South China Morning Post. Accessed July 12, 2023. https://www.scmp.com/news/people-culture/article/3129880/chinese-government-bans-those-weird-buildings-xi-jinping-cant.