ABSTRACT

In recent years, increased interest in the Professional judgment and Decision Making (PJDM) of outdoor instructors has focused on experts. This paper builds on earlier work, exploring the components and development of PJDM in mid-career outdoor instructors. The study conducted and thematically analysed semi-structured interviews with nine senior instructors working for Outward Bound Trust (the Trust) in the UK. Findings included two over-arching themes; (1) a Hahnian approach to development, in line with the philosophies that underpin the Trust’s work, and (2) practical wisdom: the synergy of contextual comprehension and appropriate options. We conclude that these mid-career outdoor instructors’ decision making is dependent on high levels of situational awareness, situational demands, and availability of appropriate options as a course of action. We further identify a philosophical chain between the Trust’s ethos, instructor development, and adaptive expertise. These skills develop through a process akin to a cognitive apprenticeship within the Trust’s community of practice.

Introduction

Research into the Professional judgment and Decision Making (PJDM) of outdoor professionals has primarily focussed on the PJDM of expert outdoor instructors (Collins & Collins, Citation2015a, Citation2016b). However, recently in this journal, Mees, Toering, and Collins (Citation2021) explored the development of PJDM in early-career ‘competent’ instructors. That study found that for early-career instructors managing safety was a primary focus, which, alongside complex situational demands, led to high cognitive demands on those instructors. For those early-career instructors, decision making skills were developed through a social experiential learning process that included challenging formative experiences within their community of practice, and, crucially, a metacognitive development through this. This paper expands that initial investigation, filling a gap between competent and expert by examining mid-career instructors. Consequently, we consider the development and attributes of these mid-career instructors and ask two questions: What are the components of effective PJDM in these instructors, and what do those instructors perceive are the critical factors in the development of their PJDM?

PJDM in the outdoors

The ability to decide on what developmental tool to use, and in what context, is a core skill for the outdoor instructor and has been operationalised in coaching via PJDM, by Abraham and Collins (Citation2011b) and more recently in adventure sports by Collins & Collins, (Citation2015b), Collins & Collins, (Citation2016a), Collins & Collins (Citation2016b). PJDM has proven effective in other domains including social work (Taylor & Whittaker, Citation2018), sports psychology (Martindale & Collins, Citation2005), and strength and conditioning (Downes & Collins, Citation2021).

The Outward Bound Trust (The Trust) is an educational charity providing personal development for young people aged 10–25 through residential adventure education courses. The courses are built on Hahnian educational philosophies: that people are capable of more than they know, and by pushing beyond perceived limits and reflecting on that, they can be brought to realise it. Based at residential centres across the UK, these courses are predominantly 5 days in duration and promote deliberate learning through adventure activities such as mountainous expeditions, overnight wild camping, canoe journeys and rock climbing. The Trusts approach exploits the hyperdynamic nature of adventure experiences which are characterised by multiple interrelating factors, and are information-rich, but present ill-structured problems that are often time-constrained (Collins & Collins, Citation2016b).

PJDM has been viewed as a relevant model of decision making in these hyperdynamic environments. PJDM is a dual process, a synergy of naturalistic and classic decision making processes. Naturalistic decision making is characterised by uncertainty, changing conditions, time pressures, high stakes, and organisational constraints (Zsambok & Klein, Citation1997). This process derives from experience, recognition primed decision making, heuristics, and intuition. This is framed within classic decision making, a more rational and logical process, which is more time-consuming. Both are cognitively demanding, naturalistic because of sub-optimal information and classic because of the quantity of information. The two processes operate in synergy, the proportion of each varying, depending on the context of the decision. Typically, a more significant proportion of classic in planning and review, a larger proportion of naturalistic in-action.

Significantly effective PJDM is contingent on declarative (the what), and procedural (the doing) forms of knowledge (Anderson, Citation1983), which lie at the heart of the options available to the instructor. However, both are operationally dependent on conditional knowledge (the why) (Abraham & Collins, Citation2011a) derived from the context via a high degree of situational awareness.

Situational awareness and demands

Situational Awareness (SA) is essential for PJDM, particularly in the hyperdynamic environment cited above. Endsley’s (Citation1995) widely accepted definition of SA describes three levels:

The basic perception of information in context, without which there is a chance of basing judgements on an inaccurate conceptualisation of the situation.

Combining, interpreting, storing and integrating multiple pieces of information to comprehend the meaning in context.

Projecting that information to predict future events and their implications.

SA is a separate stage of the decision making process, preceding decisions, but part of a cyclical process whereby SA is, in turn, impacted by those decisions (Endsley, Citation2000). As a result, SA generates demands on the decision making process.

These situational demands refer to the understanding of the task, including the constraints, participant needs and aims (Abaham & Collins, Citation2015; Flach, Citation1995) and have four co-dependent domains: environmental demands, group needs, availability of resources, and self-awareness (Mees et al., Citation2021). Although the relationship between SA and situational demands is synergetic (Collins, Giblin, Stoszkowski, & Inkster, Citation2020), simultaneous comprehension and management of these combined demands create cognitive load (Collins & Collins, Citation2019). This load can narrow attentional focus, with an associated deterioration of SA (Prinet, Mize, & Sarter, Citation2016) and a commensurate decline in the quality of the decision.

Developing PJDM and adaptive expertise in outdoor instructors

Instructors employed by The Trust must be qualified, holding a national governing body award, at the minimum level, e.g. Summer Mountain Leader, Rock Climbing Instructor (Mountain Training, Citation2022), or Paddlesport Instructor (British Canoeing, Citation2022). In addition, every instructor undergoes a six-week induction process that introduces the instructor to the organisational structures, operating procedures, the support frameworks, and The Trusts community of practice. A process of in-house final sign-offs is then used to clear the instructor to lead activities, highlighting that The Trust shares Barry and Collins’ (Citation2021) view that national governing body awards alone are not sufficient as an indicator of expertise within outdoor education. Once signed-off, the instructors will then be developed to hold additional responsibilities, e.g. directing multiple groups on a course programme. This professional growth is an intentional development supported by Learning and Adventure Managers whose role is to oversee ongoing professional development for staff: a manifestation of the Hahnian philosophies cited earlier.

Adaptive expertise

Adaptive expertise is an essential attribute for The Trust’s instructors and is facilitated by deploying PJDM (Hatano & Inagaki, Citation1986; Mees, Sinfield, Collins, & Collins, Citation2020; Tozer, Fazey, & Fazey, Citation2007). Adaptive expertise is necessitated by the complex and hyperdynamic environments (Tozer et al., Citation2007), which require adaptation and flexibility (Pulakos et al., Citation2009). Consequently, PJDM allows pedagogic agility when combined with high levels of SA; a capacity to respond to the needs of the individuals and demands of the environments—the context, and conditional aspect.

Both routine expertise and adaptive expertise require the ability to perform parts of an action without error. However, an adaptive expert utilises these interchangeable components and applies them in different ways. The components are learnt in a context, then reapplied and reconfigured to fit new purposes, thus, creating infinite contextually coherent pedagogic solutions to meet the demands of the situation. The application of these components is indicative of adaptive expertise (Hutton et al., Citation2017; Pulakos et al., Citation2009). The more dynamic the context and application, the more adaptability required.

Hanson, White, Dorsey, and Pulakos (Citation2005) offer a description of adaptability: ‘effective change in response to an altered situation’ (p. 2), in essence, linking adaptability to SA and thus decision making (Endsley, Citation1995). In addition, Pulakos, Arad, Donovan, and Plamondon (Citation2000) offer three facets of adaptability; physical, ability to adjust to the environmental changes (SA); interpersonal, adjusting interactions with others (response to the situational demands created by the participants) and mental, adjusting thinking to novel situations (a willingness to create and embrace new solutions).

Adaptive expertise entails recognising situations in which routine will not suffice, and thus a need for innovation. Pragmatically, procedure, routine and adaptability are applied to resolve the pedagogic challenges (Olsen & Rasmussen, Citation1989; Sonnentag, Niessen, & Volmer, Citation2012) faced by the instructor via the synergy of nested decision making processes, use of knowledge, hypothesis construction and evaluation, and solution-finding (Lin, Schwartz, & Hatano, Citation2005).

Innovators can only be adaptive experts if empowered and enabled to operationalise their intention to act, have the process and meta-process required to retain and transport knowledge, and operate within a culture and community of practice in which innovation is valued and championed (Kirton, Bailey, & Glendinning, Citation1991). Adaptive experts focus on acquiring new knowledge, skills, and reflection on their application. Mees et al. (Citation2020) surmised that this might also influence how the instructors’ knowledge is interconnected and understood procedurally, episodically or semantically. Consequently, there is a value placed on the instructors’ own learning, application of knowledge, and problem-solving (Bell, Horton, Blashki, & Seidel, Citation2012; Bransford, Derry, Berliner, Hammerness, & Beckett, Citation2005). In addition, there is a willingness to recognise challenges to that knowledge, identify and replace assumptions, and fill skill gaps (Bransford et al., Citation2005; Crawford, Schlager, Toyama, Riel, & Vahey, Citation2005). This capacity to self-assess requires cognitive flexibility, deep thinking skills, and metacognitive abilities (Barnett & Koslowski, Citation2002; Bell & Kozlowski, Citation2008; Stokes, Schneider, & Lyons, Citation2010). Consequently, adaptive experts appear willing to critically challenge assumptions and embrace new approaches (Lin et al., Citation2005). Developing adaptable outdoor instructors who can operate in the hyperdynamic environment with a range of different groups is vital, as is further investigation into the development of such attributes.

Method

Reflecting our study aims to identify the components of effective PJDM in these mid-career instructors and comprehend what those instructors perceive as critical factors in developing their PJDM, we adopted an inductive approach, identical to Mees et al. (Citation2021) enabling direct comparison between early-career and mid-career instructors in the same organisation.

Participants

A purposive sample of British mid-career instructors (n = 9, mean age = 40) was selected from instructors working for The Trust in the UK. To ensure good domain-specific knowledge, selection was based on the following criteria:

Employed by the Outward Bound Trust as a Senior Instructor

Between 7 and 15 years of experience as a competent outdoor instructor prior to promotion as a Senior Instructor.

Having the capacity to lead several adventure activities independently.

Availability due to work routines and COVID-19 restrictions (a convenience sample in this respect)

Willingness to discuss professional practice

We recognise these participants as mid-career or ‘skilled’ (Dreyfus & Dreyfus, Citation1986) instructors, differing from late-career or ‘expert,’ and early-career or ‘competent’ (Mees et al., Citation2021) instructors. This sample’s total experience ranged from 7 to 21 years (m = 15), and time at The Trust from 3 to 15 years (m = 6). All participants held multiple (m = 4) adventure sports coaching or leadership awards and had multiple sign-offs to lead within the trust, with at least one higher-level award, their activity area of expertise. Six participants held a higher-level academic qualification in outdoor education (e.g. a degree). All participants were white British males. The impact of COVID-19 reduced the number of instructors active at the time of the study.

Procedure

Following ethical approval and participant consent, a cognitive pilot was conducted with a representative sample (Willis, Citation2005). No changes were made to the protocol used by Mees et al. (Citation2021), as such we utilised an identical interview guide ().

Table 1. Semi-structured interview guide.

Each participant was interviewed at a convenient time and place following a teaching session. At the beginning of the interview, the researcher identified a situation and decision which occurred during the session. Having agreed on the situation this was used as the focal point for the interview questions. Interviews lasted between 29 and 61 minutes (m = 43) and were digitally recorded for later transcription by the first author.

Analysis

Data was analysed through an inductive reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021). Firstly, interviews were transcribed verbatim by the first author, beginning the familiarisation process before re-reading, checking and correcting against the recorded interview. Next, data was coded by the first author based on what they highlighted about the participants’ decision making and development. Based on these codes, themes were generated, then reviewed, developed, and refined in an iterative and reflexive process. The aim was to understand and interpret the data and identify themes. Themes were not identified dependent on the frequency of codes, but on what they revealed about instructors’ decision making and development.

The authors are experienced qualified outdoor professionals across a range of activities and organisations, with a combined experience of over 50 years. Both authors subscribe to the notion that theory-free knowledge is impossible and acknowledge that bringing their specialised experience to their roles will have influenced data collection and analysis. Accordingly, the generation of themes in a reflexive thematic analysis has an inherently subjective aspect, and as such, themes cannot be generated without reference to the researchers’ values and experiences. The authors subscribe to a pragmatic research philosophy (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2004) whereby research requires a practical outcome and is the result of an epistemological chain coherent with the authors’ values (Teddlie, Citation2005), hence a reflexive thematic analysis process.

Whilst the notion of bracketing was considered, it suggests that it is possible to put aside all preconceptions and biases before beginning analysis, in direct contrast to suggestions from Braun and Clarke (Citation2021) in their reflexive thematic analysis. Consequently, we reject the notion of bracketing. Instead, a reflective journal, and critical friend (see Costa & Kallick, Citation1993), were utilised to assist in challenging our assumptions. Naturally, findings by Mees et al. (Citation2021) regarding early-career instructors were acknowledged prior to analysis, however as we took an inductive approach, these concepts were not used as a guide for analysis. Unique identifying codes (Robson & McCartan, Citation2016) were assigned to ensure the participant’s anonymity and avoid deductive disclosure (e.g. OI1).

Results

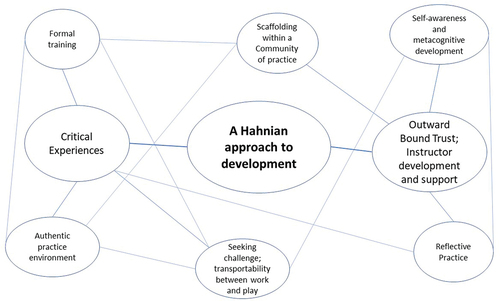

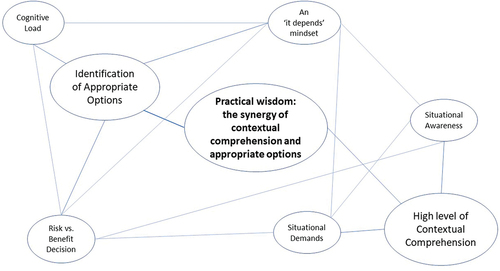

The analysis generated 312 codified units which informed two overarching themes: (1) A Hahnian approach to development, reflecting The Trust’s underpinning philosophy, supported by two themes and five sub-themes, and (2) Practical wisdom: the synergy of contextual comprehension and appropriate options, supported by two themes and six sub-themes, as illustrated in .

Table 2. Overarching themes, themes, and subthemes.

Throughout the iterative process of developing themes, we revisited, built, and refined themes; however, as with the complex and ‘messy’ (Simon, Collins, & Collins, Citation2017) nature of outdoor instructors’ operational environment, there remained some connected, interactional and overlapping areas across themes and subthemes. This is captured by each overarching theme, however, to avoid the implication of a linear relationship between subthemes we have utilised thematic maps () (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) to represent the relationships in addition to . The links between subthemes are indicated by lines on the map, highlighting where an element of the subtheme has a relationship to an element of another. For example, an authentic practice environment is a subtheme in its own right, noting the importance of authenticity and real consequence in practice. However, it is also related to formal training (which may be conducted in an authentic setting) and to seeking challenge (where instructors sought to practice their skills in challenging environments outside of the workplace). These three subthemes are collated under the theme Critical Experiences.

Figure 2. Thematic map: practical wisdom: the synergy of contextual comprehension and appropriate options.

A hahnian approach to development

Reflecting the Hahnian philosophies that underpin The Trust’s approach to outdoor education, instructors attributed their development to ‘critical experiences.’ They purposefully sought out experiences to challenge themselves ‘seeking challenge’ but also acknowledged the impact of ‘formal training’ on their development. Crucially, the most valuable of these critical experiences occurred within an ‘authentic’ practice environment. Instructors also described a purposeful facilitated development encompassed by the theme ‘Outward Bound Trust; instructor development and support’ which was ‘scaffolded within a community of practice’ (Wenger, Citation1998). ‘Living’ (OI1) The Trust philosophies and beliefs enhanced instructors’ ability and inclination to participate in ‘reflective practice’ which further developed their ‘self-awareness and metacognition.’ These themes are relational, which we highlight using the thematic map (), as such the results below may include links to subthemes from the other theme.

Critical experiences

The instructors sought out experiences that would challenge and support the development of their decision making skills, consistent with a Hahnian ethos. These need not be successful experiences but were considered to be authentic and involving real risk; OI4 described ’I have gone through, you know, some pretty dire moments, with groups or with [climbing] partners or, you know, just out and about doing stuff. And that’s definitely influenced some of the decision making’. Getting things wrong, ’trial and error’ (OI9), was something all instructors noted as developmental. However, the value was created by effective reflection ‘I can remember that was a big moment, it was like right I’ve gotta work on that’ (OI5) to translate the experience into valuable learning.

The instructors recognised the limitations of their national governing body awards, and highlighted that their work in outdoor education involved additional skills and decision making; OI7 said, ‘you do all the NGB [national governing body] training sort of stuff … It’s like that’s all kinda how you just keep people safe basically and, like, that’s like, only one little bit of our job here is to keep them safe.’ When operating in the hyperdynamic environment, with varying situational demands OI3 highlighted the challenge and weakness of following a set process, describing an event early in their career:

I worked with these, sort of challenging, well, fairly challenging groups in Merseyside, yeah, quite soon after I was qualified as a sailing instructor and, I just really realised the moment they stepped off the minibus, that going through the RYA’s Method [wouldn’t work]

The instructors highlighted the need to understand the prescribed processes ‘they are very prescriptive’ (OI3) reflecting Hatano and Inagaki’s (Citation1986) contention that routine expertise precedes adaptive. Understanding enabled deconstruction of the process and then adapted reconstruction to fit the context. OI1 described the evolution of this ability, in-context, which occurred later, after qualification:

It’s like a driving test … they [the awards] really sort of, give you that skill set to kind of operate competently within that, within the remit of the qualification … I don’t believe you come away from that being like, excellent, because you’ve not delivered it to groups

OI7 described intentionally practising decision making as a skill in its own right and explained:

If you are in an environment yourself that’s genuinely challenging and you are having to make some properly consequential hard decisions, it’s like, it’s a skill, isn’t it? And like any skill, you get better at doing it when you actually push yourself to have to do it somewhere difficult.

Instructors sought out personally challenging experiences to develop their decision making in their own time; they did not actively seek out risky decision making environments as an aspect of work, potentially due to the cognitive demands and the consequent impact on the quality and safety of their session. There was a distinct separation between what was an acceptable level of challenge at work, and what was acceptable at play, OI3 commented that it was essential to ‘separate out work and other people’s well-being, with having your own adventures.’ Nevertheless, decision making practice in a variety of authentic environments aided in developing the instructors’ confidence in their ability to apply their skills; ‘Managing yourself and friends and whoever you’re with, in more challenging environments, I guess then ties back to like, being more confident when you are in these, kind of, less challenging … ’ (OI7). This highlights an understanding of decision making as a vital skill, transferable between both work and play, and different activities, suggesting a meta aspect to the transportability of the decision making skills.

Outward bound trust; instructor development and support

As noted earlier, the notion of development through challenge is central to The Trust’s ethos and inherent in this community of practice: the counterbalance that made this feel achievable was the supportive culture in the organisation: the scaffolding provided. OI1 summarised ‘It’s working with the people that I work with across the Outward Bound Trust, that I feel like has provided that, sort of, safe environment in which to work on those things.’

This community of practice offered instructors a breadth of potential knowledge accessed through working with others in formal team-teaching, as OI6 explained: ‘you see so many different people and so many different ways of working, and so many different thought processes, so many different ideas. It’s like, wow, I’ve got all this information to draw from,’ highlighting the value in an approach that makes thinking visible. ‘Sharing stories with colleagues’ (OI6) informally, e.g. during minibus journeys to the venue or in the staff room over a cup of tea, was also considered valuable and evidenced a professional culture, as OI3 explained: ‘People used to chat about their day openly and chat about anything that had, sort of, happened … you know, that kind of informal chat time is quite important really.’ Formalised processes scaffolded this informal communication and formed part of the safety culture, e.g. sharing of plans and lessons learned in morning staff meetings, formal and informal social interactions as part of the centre routine, and memos with updated safety information distributed via the centre or Trust internal communication.

Notably, the instructors wanted to comprehend their own and others’ decisions, to become more metacognitive; OI7 described favouring ‘lots of conversation about, like, why people do what they do. Like, people have different thought processes and different ways … Particularly at Outward Bound where we have such freedom.’ Rather than focusing on just the declarative and procedural knowledge, instructors also aimed to understand the conditional knowledge required; the how and why.

The instructors noted that early in their careers, opportunities for decision making were limited because their practice was more prescribed. There was a need for initial technical competence and a shared mental model of the Trust’s practice to be developed before variety could be gradually integrated into practice and adaptable decisions made. As the instructors’ expertise developed so too did the breadth of the situational demands, akin to a bandwidth expansion process, the bandwidth expanding gradually. This highlighted the significance of the instructor induction process before working for The Trust and the ongoing development.

There’s a balance of, like, needing some level of experience to get to that point isn’t there … to have those basics nailed first, otherwise, you start, I think if you start thinking about all that extra stuff, that’s when you’re gonna forget something that’s important and somebody’s gonna die! (OI7)

In jest, OI7 highlighted the importance of having enough physical and cognitive resources ‘in hand’ to be able to process all the additional elements of the role of the personal development instructor and maintain safety, demonstrating their metacognition and noting the importance of scaffolding.

All instructors appeared to be reflective practitioners ‘I’m a reflective person’ (OI9). These skills had developed as part of participation in adventure activities; challenging our initial assumption that these skills had developed as an aspect of their professional practice. The Trust placed a high value on on-action reflective practice. However, OI7 highlighted reflections organic in nature ‘I don’t tend to, like, sit down and consciously think, right, I’m gonna think about what happened today. It’s more sort of organic and happens as I’m out and about doing stuff.’ Reflective practice was integrated into practice rather than an addition, reflecting similar findings to Nash, MacPherson, and Collins (Citation2022) in sports coaches. The instructors favoured different styles of reflection, some preferred ‘sitting and thinking’ (OI8), while most preferred a critical friend: a fellow instructor or mentor, discussing with others from their community of practice for contextual understanding, ‘my reflection is just through a conversation about, you know, this is what happened, this is why it happened, if it was happening again, this is what I’d do, this is how I’ve learned from it’ (OI4). The significance and value placed on reflection support the notion of a cognitive apprenticeship (Collins, Brown, & Holum, Citation1991), where tacit processes are made visible in order to develop cognitive skills, that aligned with The Trust’s ethos and culture. However, the reflective process is far more integrated and less formalised than anticipated. This reflection was purposeful with clear intentions to draw conclusions and an equally clear intention to act on the findings.

Critically, the instructors described reflecting on their PJDM, a metacognition ‘I sort of replay, what decisions did I make? Was I happy with them? Is there anything I could have done differently?’ (OI8). This links with the desire to seek out challenge cited earlier ‘it allowed me to unpick what I already knew and put that into some sort of context, and then I could fill in the gaps of what I didn’t know’ (OI5). The instructors learned that these challenges provide powerful developmental opportunities ‘that was some of the more challenging, sort of, decision making risk management type stuff I’ve had to do. I think that experience … if I had to pinpoint when I started getting better at doing it, that was probably it’ (OI7). Their personal adventures informed their self-awareness and consequently PJDM skills.

Practical wisdom: the synergy of contextual comprehension and appropriate options

OI7 described the key to decision making as the ’ability to pick the right thing, for the right group, in the right situation’. This statement encompasses the key components of skilled outdoor instructors utilising PJDM. Namely, the practical wisdom which synergises the ability to have several viable technical and pedagogic options to select from (choosing the right thing at the right time), and to have a high level of contextual comprehension, relating to the situational demands (the right group), and SA (the right place). The identification of these options both relies upon and supports successful management of the instructors’ cognitive load. The instructors were ultimately aiming to balance risk and benefit in their decisions, mindful of the dynamic factors involved in the context, with an ‘it depends’ mindset. As before, these themes are interconnected, as demonstrated by the thematic map (), consequently some subthemes do appear in other themes throughout the results.

A high level of contextual comprehension

These instructors consistently demonstrated a high level of SA ‘the water levels were pretty tame, pretty low. There was no real consequence of being washed away. Or, you know, if there was a slip, it would only be a small one’ (OI4). This projection level of SA was based on nuanced environmental knowledge, venue-specific knowledge, weather, conditions (tide, water levels, terrain) and temperature. A basic projection level of SA was evident amongst all the instructors, ‘on a different day there would be lots more’ (OI7), with a higher level of extrapolation and projection amongst those with broader and greater experience,

On an inconsequential grass slope, I mean, you see them fall over a lot, and you think right, ok, if that was a consequential place then I’d need to be on that, but then really you can predict when they’re gonna fall (OI5).

However, a reactive approach was also evident when encountering unpredicted events. For example, OI8 described ‘there’s this water [unusual conditions] that I hadn’t brought into play, so I should probably react to that. This seems like more of an obstacle than I’d previously anticipated,’ suggesting an additional capacity to have ready access to options for events that could not be anticipated. We conjecture that this may be in the form of an immediate action plan, If X happens then we will do Y and a solution to acute rather than chronic decision making demands.

Comprehension of the situational demands was apparent in three similar levels to SA cited earlier; a descriptive ‘it’s the attitude within the group, and the characters, you know individuals within that team, how they responded to each other’ (OI1), a comprehension ‘pre-existing injury that, sort of led to that, like the planning to avoid him having to do something he couldn’t do’ (OI2), and a projection ‘if one of them was to decide to do something stupid, are the others gonna rein them back in?’ (OI7).

Situational demand was made up of identifying, understanding and predicting psychological demands, for example, the emotional state of the group in the environment ‘trying to, like, set the week up in a positive way and get them to buy into why they’re here and enjoy it’ (OI7); physical demands, such as the ability of the group ‘they’d not had the best night’s sleep, feeling a bit tired and achy from the day before’ (OI6); social demands, for instance, the group dynamic ‘I’d be watching for how they sort of, like, react to each other’ (OI2), and the impact it may have on the session ‘collectively, [they] had sort of coalesced into … an esprit de corps, a real sort of team spirit in terms of the level of challenge that I felt they were capable of’ (OI1).

In addition, the situational demands were also created by the developmental aims of the session: the learning outcomes. These may be curriculum-based with school groups, socially based with youth groups, or professionally based with apprentices. For instance:

We were working on a bit of goal setting, the team had set some broad goals to relate to their aims, which relate to the values of the company. So, they were broadly looking at safety, sort of, pushing their challenges, and their support and encouragement. (OI3)

The participants recognised that the root cause of past mistakes was frequently connected to poor assessment or management of these demands, OI7 said:

I’ve had a few … yeah, just things where it doesn’t work at all, and it could be like … just the sort of level of challenge is completely wrong or the group, or sort of, trying to put some learning focus on something that they’re not ready for.

This also describes the required environment knowledge, OI6 expressed a ’need to know it well enough’ when referring to the SA. This knowledge helps to ‘build up a picture’ (OI3), informing the PJDM; however, it may also imply challenges in transferring SA from context to context. While these instructors demonstrated predictive levels of SA, this may not be fully formed or be transportable between contexts.

These instructors reported developing their contextual comprehension via observation and questioning of their groups while undertaking activities, in a specific and progressive way, before any point of commitment. OI9 explained

It’s what they’re saying, what they’re doing, how they’re behaving around you, as to whether, what’s their emotional intelligence level, what’s their fitness level. Then you take that a step higher and go, let’s go do jog and dip. During that, is a really good profiling tool … you find out what, in some way what attitude do they have to the course, what’s their motivation?

In addition, the instructors described their ability to read facial expressions, tone of voice, body language and changes in behaviour to inform their understanding of the situation: an emotional intelligence. This skill seemed particularly important to utilise in challenging places. OI5 described ‘they’re not like spread eagle, they’ve got their weight on their feet, they’re moving fluidly … you can see in their eyes they’re not totally gripped.’ OI6 explained the synergy ’it depends entirely upon who they are, what the aim is and what the environment is doing’.

Identification of appropriate options

The instructors selected from a range of strategies (options) to ensure the safety and education of their participants, a risk versus benefit. OI7 described the decision making process:

I guess kind of, balancing up those things, and like, today [the environment] being sort of benign, and with such a nice sort of, competent group, you can very much focus on the learning side. But like, yeah, in different situations that balance would be totally different.

The instructors pre-filtered their options while planning their sessions based on contextual priors (Gredin, Bishop, Broadbent, Tucker, & Williams, Citation2018) to create a straw man plan of viable options. For example, understanding and projecting the meaning of a northerly wind at a particular venue, the physical impact, and the group’s ability. Options could then be discounted or retained as ‘workable’ as the wind strengthened, because of the terrain, or the group became more fatigued than anticipated, because the wind was colder. The consequential framework plan is flexible, adaptable, and highly conditional: ‘it depends’ (OI6), ‘I might be more kind of direct, and more kind of, lead from the front’ (OI4).

A unique characteristic of these mid-career instructors’ plans was pre-set points during the session to make crucial decisions ‘there are points where you are deciding, are we gonna do the through trip?’ (OI7), dependent on a projection of the PJDM process, the progress of the activity being measured against the anticipated conditions and groups performance. The projection of the situation demands was based on an anticipated trajectory of development. Consequently, the instructors discounted some options ahead of time, based on their experience with the group or the situation differing from that anticipated, ‘the start, that was already kind of pre-set, having already seen them’ (OI4). In this respect, the instructor contrasts reality with what they anticipate.

OI6 indicated the cognitive effort required in balancing the demands, ‘there’s only so many plates you can spin, you’ve got to keep them spinning.’ The instructors reported discomfort in new environments where they prioritised the SA at the expense of the cognitive resources deployed to the situational demands, a metacognition, to reduce their pedagogic agility in favour of security. OI7 described,

The first time I took a group in this gorge, I was more concerned with managing them safely through it than I was with what the learning outcomes were. But as you get to know it and get comfortable with it, you can, and you’ve got then the headspace to be thinking more, a bit more about the other needs of the group.

When these instructors were comfortable in the context the balance returned in favour of pedagogic adaptability and flexibility; it was ‘safe enough’ (OI2) and thus more cognitive resources to be deployed to meet the situational demands.

OIs described various strategies used to manage cognitive load, such as pattern recognition or intuition ‘maybe I don’t have any awareness that I’m doing it’ (OI4); heuristics ‘I kind of look at it as lemons in a row. When you get to three lemons, you really want to start wondering, is this what we should be doing?’ (OI6) (Raffan, Citation1988), the community of practice ‘chat about anything that had happened’ (OI3), planning for adaptability ‘Never go to war without an exit plan’ (OI9), and proactive coping ‘guessing when it’s likely to go wrong’ (OI2).

Instructors also attempted to maintain some control of the environment by replanning to optimise stable weather conditions or selecting less-dynamic environments

I go into the environments that I feel more than comfortable in … And then that’s quite significant really and gives you that that sort of headspace to, you know, you’re not thinking about what you’re personally doing. So, you can, you know, you’ve got time for people you’re with (OI3).

These mid-career instructors manipulated the demands to reduce cognitive load utilising prior knowledge of participants ‘to walk into something completely blind … I would only do that if I was with people who I knew were capable’ (OI6) and having complete comprehension of the aims for the session (situational demands) ‘you’re like completely and utterly confident with the, like, delivery of that course … there’s a lot more, like, freedom in your head, space in your head’ (OI7). These strategies enabled instructors to focus their cognitive efforts on addressing the pedagogic demands.

Discussion

These instructors frequently described reflecting and learning from authentic, diverse experiences involving real risk: critical development experiences (Tripp, Citation2012; Webb, McElligott, & Collins, Citation2021) and intentionally sought them out as a way to develop, suggesting a growth mindset (Dweck, Citation2012). Developing the instructors’ metacognition appeared critical in gaining the declarative, procedural and conditional knowledge essential for adaptive expertise (Mees et al., Citation2020). Collins, Collins, and Grecic (Citation2014) identified an epistemological chain linking instructors’ beliefs to their practice.Our findings suggest an additional chain links these instructors with the Hahnian philosophies associated with The Trust. Mees et al. (Citation2021) also identified this in the competent instructors, but to a lesser extent. The instructor’s philosophical coherence with The Trust’s may be the attraction to work at The Trust, or could be instilled via their induction, work, and training; though we suggest, in reality, is a combination of the two. Such findings suggest the induction and development process may be akin to a cognitive apprenticeship approach which utilises methods such as modelling, coaching, scaffolding, articulation, reflection and exploration (Barry & Collins, Citation2021; Dennen, Citation2004) or could be enhanced by adopting a cognitive apprenticeship and is worthy of further investigation.

The community of practice held shared mental models of instructional practice (Abraham, Muir, & Morgan, Citation2010). One aspect of this was a shared ‘Outward Bound language’ that appeared to be constructed through observations, engagement, and reflection on the community’s shared experiences. This allowed instructors to access, understand and interpret their knowledge (Collins & Evans, Citation2007), facilitating their development and comprehension of work in The Trust.

Team teaching and the support of peers have been linked to a reduction in stress and anxiety (McGovern, Citation2021) and according to Vernon (Citation2011) shapes professional, social, and personal success, emphasising that work and play are not mutually exclusive. Development in one domain supports development in the other, highlighting the centrality of the community of practice in ongoing professional development for these outdoor instructors.

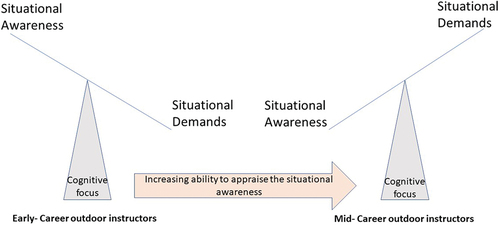

The ability to do the right thing, in the right place, with the right people, at the right time echoes the findings of Mees et al. (Citation2021) in early-career instructors, however reflecting Endsley’s (Citation1995) levels of SA, these mid-career instructors held a comprehension and projection level of the situational demands (Abaham & Collins, Citation2015). Early-career instructors and these mid-career instructors operated in similar environments, in the same organisation, and with similar aims. However, these mid-career instructors found appraising the situational demands less difficult and less cognitively demanding and were, therefore, able to facilitate greater pedagogic agility. Consequently, the decision making strategies between the two groups differed in focus. Early-career instructors tended to plan in detail, becoming attached to the plan and limiting their adaptability, a time invested heuristic. Comparatively, mid-career instructors utilised a straw man plan, with set points to make crucial decisions on preselected options which were audited throughout the session (Collins & Collins, Citation2019). The uncertainty and scarcity of knowledge generated cognitive demands (Collins & Collins, Citation2019) and perceived lack of control may create anxiety (Bunyan & Boniface, Citation2000); thus, in unfamiliar situations, the mid-career instructors identified a focus primarily on safety, a possible metacognition. Comparatively, the early-career instructors prioritised safety (SA) regardless, while mid-career instructors took a risk-benefit decision: Is it ‘safe enough’ as OI2 said, to focus on the education? Is it risky enough to facilitate development? summarises this difference in cognitive focus between early-career and mid-career instructors, with early-career instructors focusing on SA (i.e. safety) and mid-career instructors, likely due to the SA requiring less cognitive demands, focusing on situational demands (i.e. pedagogic needs).

Limitations, further research, and implications for practice

We acknowledge that this study has some limitations. Firstly, the participants were of a single gender, owing to the challenges in finding suitable participants during COVID-19. Reflecting the research aims the instructors came from within a single organisation; however, we recruited participants from three different centres across The Trust. We also note the advantages of removing some variables in understanding the development of instructors who have had some parity across their recent professional development, thus enabling more direct comparison between groups.

Several new potentials for investigation have emerged; the existence of a philosophical chain linking the organisational ethos and instructor beliefs, which is then evidenced behaviourally in their practice; further studies of the development and evaluation of metacognition in instructors; and the suitability of the club-based national governing body awards for professional use. Interestingly, the instructors noted that their national governing body training was misaligned with their professional careers (Sinfield, Allen, & Collins, Citation2019). They needed to deconstruct the procedures advocated in NGB training and identify their loose parts (Nicholson, Citation1971) to reconstruct in each individual situation. This raises two points: first, the suitability of the national governing body awards which reflect a historic club-based approach to adventure activities in the UK, for outdoor education. More significantly, the entry-level national governing body awards are competency-based, rather than expertise-based assessments (Burke, Burke, & Martindale, Citation2014). Although some aspects of practice are competency-based (e.g. tying a figure-of-eight knot or performing a bow draw), many other elements such as decision making are aspects of adaptive expertise and might be better trained and assessed with a mixed competency-expertise focus. Indeed, an effective tool for the assessment of decision making requires investigation.

Finally, the similarities of the Trust’s approach to cognitive apprenticeships would suggest a value in comparing and contrasting cognitive apprenticeship with the Trust’s professional development. In line with this direction of investigation, we suggest the next step in understanding the development of PJDM in outdoor instructors is the creation of an intervention grounded in the research, which supports instructor development. The notion of cognitive apprenticeship appears to provide a scaffold for this intervention. We propose that this considers themes highlighted: contextual comprehension, cognitive load, the pre-selection of options, critical experiences, and the social aspect of development. The Trust’s instructor support appeared to have all the ‘hallmarks’ of a cognitive apprenticeship; further exploration of this as a developmental framework may enable The Trust to optimise this aspect of their programme.

Implications for practice surround the need to facilitate a development which supports instructors to become confident and competent across a variety of activities and environments, to allow them to then develop towards becoming adaptive experts. Training based on a cognitive apprenticeship has the added advantage of transportability between activities and situations.

We acknowledge a need for further metacognitive development, expanding tools such as Collins and Collins’ Big 5 questions (a series of progressively metacognitively challenging questions, which were initially researched within The Trust); targeted training to ‘coach the coach/mentor’ toward articulating the conditional knowledge, to further support shared knowledge within the Trust’s community of practice; increasing comprehension of situational demands as adaptive experts through varied practice and flexibility-focused feedback (Hutton et al., Citation2017; Tozer et al., Citation2007); and finally, development as a skilful practitioner of the activities in the environment—a prerequisite to outdoor instruction, unlike traditional sports such as football or rugby.

Conclusion

PJDM for these mid-career skilled instructors consisted of having and selecting from a range of pre-filtered options appropriate to their comprehension of the situational demands; this was informed by a detailed contextual comprehension, particularly the ability to comprehend and project the future state of these elements. These instructors purposefully developed their PJDM through intentional practice and reflection on their own experiences. These aspects sat within a clear and coherent Hahnian philosophical framework that was an integral part of an ongoing instructor development programme akin to a cognitive apprenticeship. This approach valued reflection and collaboration within a community of practice and active development of metacognitive skills, seeking out critical experiences and support from within their community of practice.

Compared with early-career instructors in the Mees et al. (Citation2021) study, these instructors appeared to have increased SA, and greater ability to anticipate and project the situational demands. They also appeared to have a pre-filtered range of options to choose from: they selected from fewer, but more suitable options, consequently with a reduced cognitive load. Going forwards, we suggest that critical elements for developing PJDM in outdoor instructors revolve around the development of SA, situational demands and the creation of options possibly using a cognitive apprenticeship approach, based on a shared mental model of practice that is contextually developed, and transferable between environment and activities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abaham, A., & Collins, D. (2015). Professional judgement and decision making in sport coaching: to jump or not to jump. In International Conference on Naturalistic Decision Making McLean, VA (pp. 1–7). .

- Abraham, A., Muir, B., & Morgan, G. (2010). UK Centre for Coaching Excellence scoping project report: National and international best practice in Level 4 coach development. Leeds.

- Abraham, A., & Collins, D. (2011a). Effective skill development: How should athletes’ skills be developed. In A. B. D. Collins & H. Richards (Eds.), Performance psychology: a guide for the practitioner (pp. 207–230). London: Churchill Livingstone. doi:10.1016/B978-0-443-06734-1.00015-8

- Abraham, A., & Collins, D. (2011b). Taking the next step: Ways forward for coaching science. Quest, 63(4), 366–384.

- Anderson, J. (1983). The architecture of cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Barnett, S. M., & Koslowski, B. (2002). Adaptive expertise: Effects of type of experience and the level of theoretical understanding it generates. Thinking & Reasoning, 8(4), 237–267.

- Barry, M., & Collins, L. (2021). Learning the trade – Recognising the needs of aspiring adventure sports professionals. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 1–12. DOI: 10.1080/14729679.2021.1974501

- Bell, B. S., & Kozlowski, S. W. J. (2008). Active learning: Effects of core training design elements on self-regulatory processes, learning, and adaptability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 296–316.

- Bell, E., Horton, G., Blashki, G., & Seidel, B. M. (2012). Climate change: Could it help develop ‘adaptive expertise’? Advances in Health Sciences Education, 17(2), 211–224.

- Bransford, J., Derry, S., Berliner, D., Hammerness, K., & Beckett, K. L. (2005). Theories of learning and their roles in teaching. In L. Darling-Hammond & J. Bransford (Eds.), Preparing teachers for a changing world: what teachers should learn and be able to do (pp. 40–87). San Fransisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2) The publisher’s URL is, 77–101.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 1–25.

- British Canoeing. (2022). Retrieved 10 March 2022, from https://www.britishcanoeing.org.uk/

- Bunyan, P. S., & Boniface, M. R. (2000). Leader anxiety during an adventure education residential experience: An exploratory case study. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 1(1), 37–44.

- Burke, V., Burke, V., & Martindale, A. (2014). The illusion of competency versus the desirability of expertise: Seeking a common standard for support professions in sport. Sports Medicine, 44(9), 1177–1184.

- Collins, A., Brown, J., & Holum, A. (1991). Cognitive apprenticeship: Making thinking visible. American Educator, 15(3), 6–11.

- Collins, H., & Evans, R. (2007). Rethinking expertise. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Collins, L., Collins, D., & Grecic, D. (2014). The epistemological chain in high-level adventure sports coaches. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 15(3), 224–238.

- Collins, L., & Collins, D. (2015a). Integration of professional judgement and decision-making in high-level adventure sports coaching practice. Journal of Sports Sciences, 33(6), 622–633.

- Collins, L., & Collins, D. (2015b). Professional judgement and decision-making in adventure sports coaching: The role of interaction. Journal of Sports Sciences, 34(13), 1232–1239.

- Collins, L., & Collins, D. (2016a). Professional judgement and decision-making in the planning process of high-level adventure sports coaching practice. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 16(3), 256–268.

- Collins, L., & Collins, D. (2016b). The foci of in-action professional judgement and decision-making in high-level adventure sports coaching practice. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 17(2), 1–11.

- Collins, L., & Collins, D. (2019). Managing the cognitive loads associated with judgment and decision-making in a group of adventure sports coaches: A mixed-method investigation. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 21(1), 1–16.

- Collins, L., Giblin, M., Stoszkowski, J., & Inkster, A. (2020). A study of situational awareness in a small group of sea kayaking guides. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 21(June), 3.

- Costa, L., & Kallick, B. (1993). Through the lens of a critical friend. Education Leadership, 52(2), 49–51.

- Crawford, V. M., Schlager, M., Toyama, Y., Riel, M., & Vahey, P. (2005). Characterizing adaptive expertise in science teaching introduction and overview. In American Educational Research Association Annual Conference. Montreal, Canada.

- Dennen, V. P. (2004). Cognitive apprenticeship in educational practice: Research on scaffolding, modeling, mentoring, and coaching as instructional strategies. In D. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (pp. 813–828). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Downes, P., & Collins, D. (2021). Exploring the decision making processes of early career strength and conditioning coaches. International Journal of Physical Education, Fitness and Sports, 10(2), 80–87.

- Dreyfus, H. L., & Dreyfus, S. E. (1986). Mind over machine: The power of human intuition and expertise in the era of the computer. New York, NY: The Free Press. doi:10.1109/MEX.1987.4307079

- Dweck, C. (2012). Mindset: Changing the way you think to fulfil your potential. New York, NY: Constable & Robinson.

- Endsley, M. (1995). Endsley, M.R.: toward a theory of situation awareness in dynamic systems. Human Factors Journal, 37(1) Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 32–64.

- Endsley, M. (2000). Theoretical underpinnings of situation awareness: A critical review. In M. R. Endsley & D. J. Garland (Eds.), Situation awareness analysis and measurement (pp. 3–32). Mahwah, NJ: LEA. DOI: 10.1007/978-981-15-1010-6_2

- Flach, J. M. (1995). Situation awareness: Proceed with caution. Human Factors, 37(1), 149–157.

- Gredin, N. V., Bishop, D. T., Broadbent, D. P., Tucker, A., & Williams, A. M. (2018). Experts integrate explicit contextual priors and environmental information to improve anticipation efficiency. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 24(4), 509–520.

- Hanson, R. A., White, S. S., Dorsey, D. W., & Pulakos, E. D. (2005). Training adaptable leaders: Lessons from research and practice. Arlington, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute For the Behavioral and Social Sciences Research.

- Hatano, G., & Inagaki, K. (1986). Two courses of expertise. In H. Stevenson, H. Azuma, & K. Hakuta (Eds.), Child Development and Education in Japan (pp. 262–272). New York, NY: Freeman. doi:10.1002/ccd.10470

- Hutton, R., Ward, P., Gore, J., Turner, P., Hoffman, R., Leggatt, A., & Conway, G. (2017). Developing adaptive expertise: A synthesis of literature and implications for training. In 13tg International Conference on Naturalistic Decision Making (pp. 81–86). Bath, UK.

- Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14–26.

- Kirton, M., Bailey, A., & Glendinning, W. (1991). Adaptors and innovators: Preference for educational procedures. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 125(4), 445–455.

- Lin, X., Schwartz, D. L., & Hatano, G. (2005). Toward teachers’ adaptive metacognition. Educational Psychologist, 40(4), 245–255.

- Martindale, A., & Collins, D. (2005). Professional judgment and decision making: The role of intention for impact. Sport Psychologist, 19(3), 303–317.

- McGovern, G. (2021). How Outward Bound co-instructor relationships create a context for emotional support during stressful course situations. Journal of Community Psychology, 49(6), 1904–1922.

- Mees, A., Sinfield, D., Collins, D., & Collins, L. (2020). Adaptive expertise – A characteristic of expertise in outdoor instructors ? Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 25(4), 1–16.

- Mees, A., Toering, T., & Collins, L. (2021). Exploring the development of judgement and decision making in outdoor instructors. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 1–15. doi:10.1080/14729679.2021.1884105

- Mountain Training. (2022). Retrieved 10 March 2022, from http://www.mountain-training.org/

- Nash, C., MacPherson, A., & Collins, D. (2022). Reflections on reflection : Clarifying and promoting use in experienced coaches. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(867720), 1–13.

- Nicholson, S. (1971). How not to treat children: The theory of loose parts. Landscape Architecture, 62(1), 30–34.

- Olsen, S., & Rasmussen, J. (1989). The reflective expert and the prenovice: Notes on skill-, rule-, and knowledge-based performance in the setting of instruction and training. In L. Bainbridge & S. Ruiz-Quintanilla (Eds.), Developing skills with information technology (pp. 9–33). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

- Prinet, J. C., Mize, A. C., & Sarter, N. (2016). Triggering and detecting attentional narrowing in controlled environments. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society (pp. 298–302). Washington, DC. DOI: 10.1177/1541931213601068

- Pulakos, E., Arad, S., Donovan, M., & Plamondon, K. (2000). Adaptability in the workplace: Development of a taxonomy of adaptive performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(4), 612–624.

- Pulakos, E., Schmitt, N., Dorsey, D., Arad, S., Borman, W., & Hedge, J. (2009). Predicting adaptive performance: Further tests. Human Performance, 15(4), 339–366.

- Raffan, J. (1988, March). Wilderness crisis management. Explore Magazine, 410, 1–14.

- Robson, C., & McCartan, K. (2016). Real world research: A resource for users of social research methods in applied settings (4th ed.). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

- Simon, S., Collins, L., & Collins, D. (2017). Observational heuristics in a group of high level paddle sports coaches. International Sport Coaching Journal, 4(2), 235–245.

- Sinfield, D., Allen, J., & Collins, L. (2019). A comparative analysis of the coaching skills required by coaches operating in different non-competitive paddlesport settings. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 2017, 1–15.

- Sonnentag, S., Niessen, C., & Volmer, J. (2012). Expertise in software design. The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511816796.021

- Stokes, C. K., Schneider, T. R., & Lyons, J. B. (2010). Adaptive performance: A criterion problem. Team Performance Management: An International Journal, 16(3/4), 212–230.

- Taylor, B., & Whittaker, A. (2018). Professional judgement and decision-making in social work. Journal of Social Work Practice, 32(2), 105–109.

- Teddlie, C. (2005). Methodological issues related to causal studies of leadership: A mixed methods perspective from the USA. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 33(2), 211–227.

- Tozer, M., Fazey, I., & Fazey, J. (2007). Recognizing and developing adaptive expertise within outdoor and expedition leaders. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 7(1), 55–75.

- Tripp, D. (2012). Critical incidents in teaching developing professional judgement (Classic ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Vernon, F. (2011). The experience of co-instructing on extended wilderness trips. Journal of Experiential Education, 33(4), 374–378.

- Webb, D. J., McElligott, S., & Collins, L. (2021). Key characteristics of optimal developmental experiences in a group of expert Sea Kayak Guides. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 1–16. doi:10.1080/14729679.2021.1935285

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Willis, G. (2005). Cognitive Interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. London, UK: Sage.

- Zsambok, C., & Klein, G. (1997). Naturalistic decision making (pp. 269–283). New Jersey: Erlbaum.