ABSTRACT

This article draws on the author’s doctoral research to examine the relationships between children’s geographies in different spaces of geographical thought in England – geography in and of everyday life, geography as an academic discipline and geography as a school subject. It begins by setting out how children’s geographies have largely been omitted from school geography due to complex reasons including the impact of governmental policy on teaching and teacher education, and the public accountability of schools. Drawing on a case study of five young people’s narratives about London, the article then examines their perspectives on education – highlighting that the young people view both London, and the education system, as a space of opportunity and hope, but also of inequality and injustice. The article concludes by arguing that through drawing on the ideas and methodologies of children’s geographies as a subdiscipline, and recognising and exploring the geographies of those who are taught, school geography can be enhanced by making teachers more informed about the children they teach and providing children with opportunities to examine (their own) geographies through engaging with disciplinary thought.

Introduction

The school gate is a boundary that most of us are familiar with – it is a social and spatial line that many people cross on a daily basis. The gate can also be an emotional threshold; a space that’s ingrained in fond or otherwise memories of our own childhood, or of dropping a child off at school for the first or last time. The gate differentiates the school from the street and the wider world; it marks the start of a space with distinct rules and expectations (Aitken Citation2001; Freeman and Tranter Citation2011; Oswell Citation2013; Hammond and McKendrick Citation2020) and where the child leaves the care of their parent or guardian and enters the charge of teachers and school managers. Traversing this boundary can be exciting and daunting, lead to feelings of anxiety and loss, and/or freedom and opportunity.

This article is concerned with this boundary and that of the classroom door. Walking into a classroom often means entering a space in which there are distinct power relationships between teachers and students (Freire Citation1970; Foucault Citation1978). These power relationships are constructed from a complex web of adult–child and teacher-student social imaginations and their embodied enactments. These relationships can affect how, and why, social interactions occur; the spatial positioning of different social actors during these interactions (Giddens Citation1986); a person’s identity; expectations of how a person should behave (Aitken Citation1994); and imaginations of what, and how, a person should learn. Recognising this boundary and the socio-emotional impacts it has on people matters; it matters to children and their experiences of education, and if and how they connect their everyday knowledge and experiences to the specialised knowledge they engage within school; it matters to their parents and carers; and it matters to teachers, policy makers and those interested in education and schooling, in considering how they provide the best possible education to society’s children.

Drawing on my doctoral research throughout (Hammond Citation2020), in this article I explore the value of recognising the reciprocal relationships between the child’s everyday life and geographies (including beyond the school gate) and their formal geographical education. The use of the term reciprocal relationships is used here to acknowledge and celebrate that as is expounded in the sub discipline children geographies, children do not enter the classroom as empty vessels (Freire Citation1970), but with rich and varied experiences and imaginations of the world (Holloway and Valentine Citation2000; Biddulph Citation2011; Yarwood and Tyrell Citation2012). In turn, children often draw upon specialised knowledge and skills learnt in, and through, their formal education in their everyday lives and futures. Despite this relationship seeming simplistic, it is highly complex and affected by social-political landscapes (Morgan Citation2019); social constructions and imaginations of children and childhood (Shapiro Citation1999; Aitken Citation2001; Citation2018; Skelton Citation2008; Hörschelmann and van Blerk Citation2012; Freeman and Tranter Citation2015); educational systems, philosophies and policies at national and school levels (Catling Citation2011; Roberts Citation2014); choices teachers make as they engage in ‘curriculum making’ (Lambert and Morgan Citation2010; Mitchell Citation2019), and children’s responses to, and interactions with, their teacher and the subject they are studying (Lambert and Biddulph Citation2014).

In this article, I argue that recognising and exploring children’s geographies is of value to school geography. I show that children’s geographies are of value to teachers, in enhancing their knowledge of the children they teach and thus making them more informed in the curriculum making underpinning their teaching. In addition, I argue that engaging with disciplinary knowledge about children’s geographies is of value to children, in providing them with opportunities to situate and explore (their own) experiences and imaginations of the world. I use the term ‘school geography’ to examine the place of geography (as a subject) in schools/schooling. The choice of terminology enables consideration of not only curriculum (what is taught) at national, school or classroom level, but also the complexities of teaching and learning, and questions of pedagogy and purpose which, teachers, school leaders and policy makers regularly grapple with.

The argument begins with the idea that geographical thought exists in different spaces – everyday life, as well as formalised in the academic discipline and the school subject. I then use the spaces of geographical thought as a conceptual framework to situate an examination of the relationships, and what Castree, Fuller, and Lambert (Citation2007) term ‘borders’, existing between children’s geographies in each of the spaces. The use of this framework supports critical consideration as to how and why both the geographies children bring with them into, and/or choose to share in, schools and classrooms, and disciplinary thought (including knowledge and methodologies) on children’s geographies, are of value to school geography. I then examine how children’s geographies have been represented in school geography. I focus specifically on geography education in England, as this is where the research took place, and argue that factors including accountability pressures in schools, and lack of teacher education in the field, have often meant that children’s geographies have gone unnoticed and/or under-considered in classrooms. I then move on to introduce my doctoral research, which investigated children’s geographies and their value to geography education in schools. Following this, I examine the findings of the research, focussing specifically on children’s perspectives on education, before arguing for the development of sustained and significant relationships between children’s geographies and school geography.

The relationships and ‘borders’ between different spaces of geographical thought

Despite both the philosophical and practical centrality of children to education and schooling, there is much debate about the relationships between the child’s rich and varied everyday life and their formal (geographical) education (Catling and Martin Citation2011; Biddulph Citation2011; Roberts Citation2014; Citation2017). Young and Muller (Citation2016) highlight the significance of these relationships to education, when they assert that the key curriculum questions policy makers, schools and teachers grapple with are concerned with the boundaries, differences and relationships, between ‘everyday’ knowledge and the specialised, theoretical, knowledge children engage with in schools and classrooms. This specialised knowledge is produced and advanced in, and organised by, academic disciplines (such as geography) and then is said to be transformed and recontextualised into school subjects (Bernstein Citation2000; Deng Citation2017; Firth Citation2018; Finn Citationforthcoming).

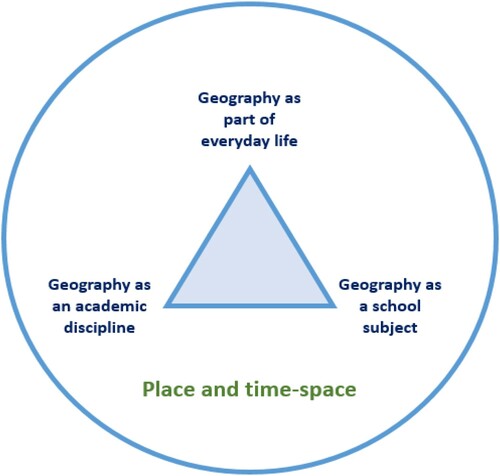

Through a conceptual triad, shows the three spaces of geographical thought, with the lines between the spaces representing relationships, and the movement of people and ideas between them. The spaces of thought also shape, and are shaped by, the place and time–space in which they exist. For example, Bonnett (Citation2008, 104) highlights that in the age of empire, Britain’s school students were expected to ‘recall the resources, communications, topographic features and ethnic groups of Britain’s overseas possessions’ in geography, in an age dominated by a pedagogy of ‘read and remember’. Today, this imperialist ‘take’ on geography raises significant ethical, political and professional questions, not least about racism and the domination of people and places, and how this is then represented in, and (re)produced through, education (Dorling and Tomlinson Citation2019).

Figure 1. Spaces of geographical thought (Hammond Citation2020).

Acknowledging these distinctive spaces of geographical thought and the connections between them is of value because it allows examination of the relationships that exist, and are possible, between each of the spaces. In the case of this article, is used to facilitate discussion as to how, and why, children’s geographies, and academic research and literature about them, are of value to school geography. I consider each of these spaces in further detail, and in doing so I explore the relationships and ‘borders’ that exist between them. Castree, Fuller, and Lambert (Citation2007) use the language of ‘borders’ to conceptualise the divisions between geography in the academy and geography in schools, noting institutional and personal constraints have often prevented the development of meaningful and sustained relationships between them. Castree, Fuller, and Lambert (Citation2007) argue that these constraints affect both those researching and teaching in the academy – who may not always be fully aware of current policy and practice in schools – and those working and teaching in schools. In the context of schools, Castree, Fuller, and Lambert (Citation2007) assert that a combination of pressures from performance league tables, and a focus on generic pedagogic skills and attainment, from both government and school leadership teams over recent years have made it ‘very difficult for geography teachers to pursue professional development through the subject – even when opportunities do exist’ (p. 130).

The idea of ‘borders’ existing between these two spaces of formal geographical thought is well recognised in debates about geography education (Butt and Collins Citation2018; Butt Citation2020; Finn et al. Citation2021). Lambert (Citation2014, 157) asserts the importance of recognising, and ultimately crossing, these borders when he explains that in order to ‘create educational encounters of significance’ school geography must re-engage with disciplinary knowledge. Lambert’s argument is situated in wider debates about ‘powerful knowledge’ (Young Citation2008; Young and Muller Citation2010; Young Citation2013; Roberts Citation2013; Young and Muller Citation2016), and the value of subjects framing the curriculum in providing students with access to this knowledge. Although disciplinary knowledge is not neutral, or free from socio-cultural norms (Butt Citation2017), for Young and Muller (Citation2010) it is a matter of social justice that all students are supported in accessing, and engaging with, this knowledge through their schooling.

In contributing to these debates, Maude (Citation2016) argues that geographical knowledge can be ‘enabling’, and introduces a typology of knowledge that is powerful to, and for, geography’s students:

Type one – knowledge that provides students with new ways of thinking about the world;

Type two – knowledge that provides students with powerful ways to analyse explain and understand the world;

Type three – knowledge that gives students some power over their own knowledge;

Type four – knowledge that enables young people to follow and participate in debates on significant local, national and global issues;

Type five – knowledge of the world.

However, concerns have been raised that debates about powerful knowledge have failed to recognise the importance of connecting to young people’s lives beyond the school gate. For example, in the context of primary education, Catling and Martin (Citation2011, 319) argue that if geography education fails to recognise children’s ethno-geographies – geographies they ‘bring with them into schools’ – then it fails both to acknowledge the study of everyday life and geographies (as is a distinct and important area of research in the academy) and also fails to respect children as people who shape, and are shaped by, the worlds in which they live. This argument is echoed by Roberts (Citation2014, Citation2017), who explains that literature about powerful knowledge has, as yet, failed to fully explore the importance of connecting new specialised knowledge to what children already know to support them in meaning making. Not considering the connections between ‘everyday’ and ‘powerful’ knowledge can therefore be seen to risk creating what Freire (Citation1970) terms ‘banking education’. In this situation, students are conceptualised as ‘depositories’ in which the teacher ‘deposits’ knowledge, and thus opportunities for engaging in reciprocal student-teacher dialogue, and respect for children’s geographies, rights and lives beyond the classroom door, are limited (Hammond Citation2020b).

Engaging with children’s everyday experiences and imaginations of the world, and academic knowledge on children’s geographies, is significant to school geography in recognising children as social actors, who are aware and self-conscious in the world, and who exist as people beyond the school gate. This knowledge is valuable not only in respecting children, who have (at times) been sub-ordinated in education and society (Freire Citation1970; Giddens Citation1986; Oswell Citation2013), but also in supporting teachers in being more informed about the children they teach. To contextualise these debates and my research further, I now move on to examine how children’s geographies have been conceptualised in school geography.

Children’s geographies and school geography

In England, children’s geographies are not included in programmes of study at any Key Stage of schooling (DfE Citation2013, Citation2014), meaning that it is not an explicit area of study directed by the state for schools that follow the national curriculum. In light of this, Hammond and McKendrick (Citation2020) report that geography teacher educators – who in the context of their research are those working in teacher education in higher education institutions – often share a perspective that the lack of recognition of children’s geographies in governmental policy is a primary reason why children’s geographies have been marginalised in the school subject.

As children’s geographies are not reflected in national educational policy in England, it is left to geography teachers and departments, and more broadly to schools, to decide if, how and why, they might engage with the sub discipline and/or the geographies of those they teach. Teachers may consider this in relation to the purposes of a geographical education – which might include taking children beyond their everyday experiences and knowledge, or encouraging children to look at the everyday in new ways, through engaging with disciplinary knowledge and methodologies, whilst respecting and valuing their experiences and imaginations of the world. Teachers may also consider children’s geographies in their curriculum choices – for example, by having children’s geographies as a distinct area of study (Roberts Citation2017). This might include exploring children’s own neighbourhood geographies using participatory approaches (McKendrick and Hammond Citation2020), or drawing on research and disciplinary thinking to examine children’s lives and geographies in other times or places. Finally, teachers may consider children’s geographies in relation to pedagogy – for example, in considering how they can support children in connecting their prior and everyday knowledge to the specialist knowledge they are studying, to support them in meaning making and to avoid banking education. Drawing on the participatory and enabling methods central to research in children’s geographies in pedagogy, may also facilitate critical examination of the relationships between children and teachers that best support children in their education.

In contrast to the Department for Education, academic geographers, and those interested in geography education more broadly, have often extolled the benefits of school geography engaging with children’s geographies (Horton, Kraftl, and Tucker Citation2008; Biddulph Citation2011; Catling Citation2011; Yarwood and Tyrell Citation2012; Roberts Citation2017). For example, in her 2010 editorial in ‘Teaching Geography’ (a professional journal published by the Geographical Association for geography teachers), Biddulph (Citation2010, 45) asserts:

Acknowledging and valuing what young people bring to the curriculum is one way of ensuring that the geography they learn is both meaningful and connected to their everyday lives; it is also the means by which we can build a bridge between young people and the mandated curriculum to ensure that the subject discipline, the geography that they learn, is a vehicle through which they make sense of their own lives as well as those beyond their immediate horizon.

Despite these arguments, the place of children’s geographies in school geography in England remains uncertain and lacks visibility. There are several, inter-related, reasons for this. First, as Firth and Biddulph (Citation2009) both highlight and contest, there are arguments within education that a focus on children’s lives and experiences in schooling would be anti-intellectual, and reduce the quality of what is taught and children’s experiences of education. In contrast to debates in children’s geographies that recognise children as social actors who shape social worlds, some academics interested geography education do not perceive children in this way. For example, Standish (Citation2009, 165) describes children as ‘immature and undeveloped beings’, asserting that they ‘are not yet able to make a valid contribution to the political realm’. Whilst Standish situates his argument in the notion of protecting children ‘from the responsibilities and pressures of adulthood’ (Standish Citation2009), his position risks disempowering children in their schooling, their everyday lives and potentially their futures, through suggesting that they cannot contribute to societal debate. This, in turn, risks allowing adults to speak for children and/or dismiss their perspectives in their entirety.

Although Standish’s ideas about school geography have been critiqued as being disconnected from the discipline of geography (Morgan, Hordern, and Hoadley Citation2019), it is significant to raise, and challenge, his perspectives as (student) teachers ‘following Standish’s advice would be forced to jettison or forget much of their own training in the contemporary subject in favour of a cleansed or eviscerated version of the school subject’ (p116). This concern is especially pertinent in regards to the relationships between children’s geographies and school geography both in considering how the child is constructed, respected and represented in education and schooling; but also in regards to reflecting on the purposes and potential of a geographical education – which, as Maude (Citation2016) suggests includes consideration as to how we enable children through geography – for example, through supporting children to use disciplinary knowledge to think about the world in different ways, and to contribute to societal debate.

Secondly, the omission of children’s geographies from national curricula can be seen to be exacerbated by the well-documented accountability pressures on (geography) teachers (Jones and Lambert Citation2018) and nationally recognised concerns about teacher workload (DfE Citation2018). With limited time, increased monitoring and a focus on student results potentially leading to geography teachers feeling they do not have the time or space to either explore children’s geographies in the classroom, or to develop their own knowledge of children and childhood.

Thirdly, children’s geographies have been omitted from some initial teacher education (ITE) programmes (Catling Citation2011). This problem has also been exacerbated, as it is situated in a context in which there are recruitment and retention issues of geography teachers in England (Geographical Association Citation2015). This has resulted in an increase of applicants, and trainee teachers, without a degree in geography. This, in turn, is situated in landscape in which there is a lessening of university subject specialist input into ITE due to a diversification of routes into teaching (Whiting et al. Citation2018). This means geography teachers may never have had an opportunity to actively consider and/or study children’s geographies (or even children and childhood) in either their Bachelor’s degree and/or post-graduate teacher education programme.

Thus, the socio-political construction of the child, especially in the context of the recent ‘knowledge turn’ in school level education in England (Morgan Citation2019) has failed to adequately consider the relationships between the child’s everyday knowledge and geographies, and the specialist knowledge they engage with in schools. Rather, subjects in schools tend to be portrayed simply as collections of knowledge students should learn (Catling Citation2011). Indeed, Catling (Citation2011) issues a stark warning that the current educational landscape is constructed of national policy which limits teacher autonomy, and omits opportunities for active citizenship and contributions by children, often failing to consider how, and why, it is of value for children to share and deconstruct (their own) geographies as part of their formal geographical education. This puts school geography at odds with academic debate in children’s geographies, in which research seeks to examine children’s experiences and imaginations of the world to better understand children, childhood and society, and to empower them in the process of doing so (Aitken Citation2001; Citation2018; van Blerk and Kesby Citation2008; Fass Citation2013).

The ‘place’ of children’s geographies in school geography in England is therefore tenuous, and heavily influenced by educational policy, and teacher education and freedoms (Roberts Citation2014). Yet, to really understand how, and why, a geographical education can be enabling and offer freedom to children in their lives and futures (Maude Citation2016), it is of critical importance to consider the reciprocal relationships between a child’s everyday life and their formal education. I now move on to introduce the research.

Introducing the research

My doctoral research was ‘an investigation into children’s geographies and their value to geography education in schools’. Data was collected in a school I had previously worked in London as a geography teacher, primarily because I had a rapport with the school community – including teachers, students and their families. The research was conducted in line with BERAs (Citation2011) ethical guidelines and was approved by ethical review at UCL Institute of Education.

My doctoral enquiry was orientated by three research questions (RQs):

RQ1 What do young people’s narratives reveal about their geographies and imaginations of London?

RQ2 How can the ‘production of space’ contribute to knowledge of children’s geographies and imaginations of the world?

RQ3 How can geography education use ideas and methodologies from children’s geographies to enhance school geography?

The storytelling and geography group was designed to enable the young people to participate through oral narratives. Whilst recognising that the group was an artificially constructed forum, the use of oral narratives aimed to enable the young people to communicate in a way that was, as far as possible, concurrent with everyday life and was familiar and accessible to the participants (Bushin Citation2009). Further to this, it aimed to empower the young people in the research, through allowing them to have ownership of the ‘control and flow’ of the stories they shared (Langevang Citation2009). This is because narratives are concurrent with human existence. Indeed, for Bruner (Citation2004, 708), ‘life as led is inseparable from life as told – or more bluntly, a life is not ‘how it was’ but how it is interpreted, reinterpreted, told and retold’. Bruner argues that humans use narratives to organise memories and events, and we ultimately ‘become the autobiographical narratives we ‘tell about’ our lives’ (p694). When this argument is considered alongside Massey’s (Citation2005) reflection that places are collections of stories that exist within the wider geometries of space and time, the use of oral narratives can support consideration of how people shape, and are shaped by, place and time–space. It is also worthy of note, that the research was conducted in a group context to facilitate examination of the relationships between individual and shared narratives.

RQ2 focussed on examining the value of using the ‘production of space’ (Harvey Citation1990; Lefebvre Citation1991) to analyse the narratives of the young people who participated in the research. The production of space is one of Lefebvre’s most influential ideas, running through many of his works, and is also a book – originally published as ‘La Production de l’Espace’ in 1974. Lefebvre’s ‘critical conscience’ (Lefebvre quoted in Elden Citation2006) on everyday life led him to engage in a multi-way dialogue – between the spaces of philosophy and everyday life – to explore the production and sustenance of power relations within, and between, societies under late capitalism.

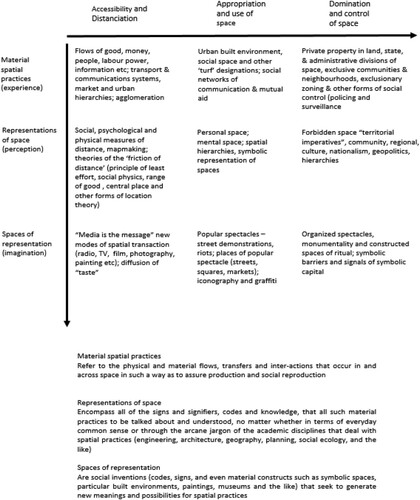

Lefebvre’s work can be seen as a struggle to affect change and ultimately to challenge inequalities (Brenner and Elden Citation2009). To support the examination of how space is produced, sustained and evolves, Lefebvre (Citation1991) introduces his readers to a conceptual triad: spatial practice; representations of space and representational space. Harvey (Citation1990) used and developed Lefebvre’s triad into a ‘grid of spatial practices’ () to further explore the subtleties and complexities of spatial practices in urban settings (Watts Citation1992). Harvey expresses his radical motivation for doing this, arguing that to transform society, we must critically explore, and seek to understand, the complexities of social space. He contextualises his motivation in the time–space of neoliberalism, which he argues is a ‘permanent arena’ of social conflict and struggle, stating that ‘those who have the power to command and produce space, possess a vital instrumentality for the reproduction and enhancement of their own power’ (p256). Thus, for Harvey, it is significant to examine how inequalities and injustices are produced and sustained to be able to truly challenge them. This argument appealed to me in the context of this research, in examining the geographies of children and young people, who have at times been under-represented, and/or subordinated, in both education and society (Freire Citation1970; Foucault Citation1978; Aitken Citation2018; Freeman and Tranter Citation2015; Morgan Citation2019).

Figure 2. A 'Grid' of Spatial Practices” by David Harvey, reprinted from 'Flexible Accumulation through Urbanization Reflections on “Post-Modernism” in the American City.' Perspecta 26. Hans Baldauf, Baker Goodwin, Amy Reichert, eds. New Haven: Yale School of Architecture, 1990. Page 257.

I used Harvey’s grid in the coding of the young people’s narratives, considering how they shape, and are shaped by, social space. Although the production of space has been influential in many academic disciplines – including geography and philosophy – it has received limited attention in the field of education (Middleton Citation2017). Therefore, engaging with academic debate on everyday life in the context of school geography enabled me to make connections between each of the spaces of geographical thought and examine the value of doing this in RQ3. I now move on to set out the findings of the research.

Research findings

The research produced evidence and insight on three aspects of the young people’s lives in London. First, the young people in the study navigated multiple, sometimes contradictory, social spaces when constructing and representing themselves, and their identities, in London. Analysis showed that young people particularly focussed on the themes of religion; sex, sexuality and gender; voice; and their experiences of feeling or being British, or indeed not, in narratives related to identity. Secondly, the young people imagined London as a jigsaw of territories with distinct social rules existing in different spaces and places within the city. Here, the analysis suggested that the young people perceived London to be what Massey (Citation2008) terms a ‘city of villages’ divided by both gangs and between ethnic groups. Thirdly, London was perceived by the young people participating in the research as a place of opportunity and hope, but also of inequality and injustice. Analysis highlighted that this linked to the conceptualisation of home, with young people’s narratives on education also being a prominent feature of their discussions. In examining the findings further, in this article I focus specifically on exploring the young people’s experiences of, and perspectives on, education. I do this to share the voices of young people, who have thus far largely been omitted in debates about powerful knowledge, and the value of (a geographical) education.

Unsurprisingly, given the centrality of schools and education to children’s everyday lives, spatial practices and the social and physical spaces they exist within and contribute to – all of the young people in the study shared narratives about education. Analysis identified the following sub themes in young people’s narratives: social hierarchies and education – including narratives related to geographies of education; exclusive communities and education – considering the opportunities and communities education affords access to; social control and education – how dominant people construct education to (re)produce space in a way that benefits themselves, and how this relates to and/or causes issues of social justice; and personal space – relating to the young people’s values and ideas about the purposes of education. I now move on to further examine these themes, drawing on the young people’s narratives to illuminate the discussions. As the themes have clear relationships between them, I explore them concurrently.

In their narratives, all of the young people reflected on the importance of social justice in education, and showed awareness of, and interest in, geographies of education at micro and macro scales. For example, when I asked the question as to whether they felt they had a good education, Tilly responded, stating:

Tilly: we get more than any other country in the world. Here, I think, they actually understand that the people who are going to be ruling over the country are children, so they of course want us to succeed. And, I think they’ve realised now, that it doesn’t matter which background that you’ve come from, it just matters what you have to give.

All of the participants in the research echo Tilly’s perception that England’s education system is comparatively strong at an international level. For example, Jack shares that along with the English language, the education system was a primary reason why his father moved their family (from another European country, although his parents were both raised in the Middle East) to England. Jack’s narratives can be interpreted as him having a clear view on the purposes of education, for example:

yeah, without GCSE’s you can’t get a job, that’s the main test! If you fail that, you fail your life!

Is education about anything else, though?

no, it’s not, it’s just your GCSE’s. The reason we come to school, is to pass our GCSEs. If we don't pass our GCSEs, then about 11, maybe even 13, years of our lives have been wasted.

Rachel’s narratives can be read as her echoing Tilly’s concerns about the impact of an accountability culture in education. For example, she states ‘I think the education system has messed us up, and it’s so depressing, it’s true, the education has messed up completely’ before noting ‘we’re only learning now, what we were supposed to learn last year’. This narrative can be seen as Rachel, to some extent, having a Hirschian (Hirsch Citation2007) view of knowledge and education, in which students have to learn content to be repeated for an exam. Rachel appears to perceive that banking education (Freire Citation1970) will support her in achieving success in her schooling. Despite their concerns about the English system, both Tilly and Rachel state that they love education. In addition, Rachel echoes Tilly in stating that she’d rather attend a state school than a private one, as she feels people are more accepted.

Rachel also talks regularly about gangs in her area and the challenges her community faces. This seems to motivate her to want to leave the area and her narratives suggest that she sees education as a route out. For example, Rachel states ‘instead of being violated and shouting and going against the government … (I’ll) work inside the system, use my mind, get my head into books, get a good education, get some money and get a good job’. Rachel goes on to express that those who have dreams of success (she gives the example of herself wanting to become a lawyer), but who hang out on street corners, are ‘just defeatist’. This narrative can be interpreted as Rachel perceiving that England provides educational opportunities, but that people have to make decisions as individuals as to if, and how, they engage with education. It can be seen as showing a perception that there are personal, as well as societal, responsibilities in regards to education and as representative of neoliberal thinking.

Like Jack, Rachel’s family, especially her father, are very eager for her to do well in school and get a good formal education. She notes that her father – who she shares was raised on a social housing estate in Glasgow in the 1970s – tells her that she should ‘throw mental bricks, stick your head in the books, learn something, get to that rank where you have a say in it, and if that doesn’t work, try again, until you get what you want’. However, Rachel’s narratives also show that she feels pressure related to accessing exclusive communities through education. For example, when discussing GCSEs, she states ‘there is so much emphasis on GSCEs now!’ This can be interpreted as Rachel perceiving that within the school she attends, and potentially in society more broadly, there is a substantial focus on attainment in national exams as part of the educational system.

As well as opportunities, the group also shares narratives related to education as a form of social control. For example, Tilly expresses that she feels the education system itself is an experiment, stating:

Tilly: ever since that we were born, we were, or I know I am, a social experiment. Because I've got this thing, because, like, you we’re born in the twenty-first-century so they can do surveys on you to see how you’re moving on, and that is, that there, we’re like an experiment. They’re are also practising the iGCSE’s on us, and they've been testing out all of the changes in the education system on us. They just want to see if we are getting better or not, but I don't think it's fair. Especially because education is meant to be, like, it's meant to nourish you, and you're meant like enjoy it, but how can you enjoy it, if they just change everything every single second.

Another area of discussion between the young people is the relationships between socio-economic inequalities and injustices, and education. For example, Jessica and Alex discuss that it’s hard for some members of the community to cross the boundary of the school gate or classroom door each day:

Jessica: yes schools for bad kids, a referral unit, and most of the kids that go to (referral unit x) won't get a job, like as a politician or anything like that. Yeah maybe I'm being stereotypical, but no one really wants a child, who has a bad attitude and a temper and stuff, and got kicked out of school, at 13. Sometimes people have to understand, their backgrounds, what they were brought up with, and that they will probably going through a hard time. And yet they have no right to bring into school, and to take it out another people, but some people just don't understand, if you get what I’m trying to say?

Alex: this also like, some people struggle to focus in class

Jessica: but some of it is their fault, if you get what I’m trying to say.

To conclude this article, I now move on to consider how these narratives and children’s geographies more broadly are of value to school geography.

Conclusion: recognising and exploring children’s geographies in school geography

Through encouraging young people to share their experiences and imaginations of London using storytelling as a methodology, this research has shown that the young people in this study feel that there is social pressure to access ‘exclusive communities’ (Harvey Citation1990) through education. Unsurprisingly due to the age group of the young people in this research, this relates to GCSEs, which analysis suggests they conceptualise as a social currency enabling them to access jobs, opportunities and social communities. The research has illustrated that the young people perceive that an accountability system related to national examinations affects both teachers and teaching, suggesting that through their experiences of education, and their socialisation more broadly, the young people have developed a Hirschian view of knowledge and a desire to receive a banking model (Freire Citation1970) of education to ensure they are able to access exams and exclusive communities. These perspectives do not consider ideas about how, or why, (geographical) education can be powerful and enabling (Lambert Citation2014; Maude Citation2016), or of the relationships between children’s everyday lives and geographies, and schooling.

This raises significant questions for those interested in (geography) education, in considering how geography education, and education more broadly, can be powerful, and enabling, to a (young) person. Here, geography education can benefit from the ideas and methods expounded in children’s geographies, through considering how, and why, children can be empowered in, and through, their education. By recognising, respecting and drawing upon children’s geographies beyond the school gate, geography teachers can be more informed about the children they teach. Knowledge about children’s geographies – including ideas, concepts, theories and methods from the subd iscipline and knowledge about the lives of those they teach – has the potential to enable teachers to support children in situating and exploring (their own) everyday lives and geographies using disciplinary thought. This, in turn, has the potential to support children in contributing to debates that matter to them and empower them in their lives and futures. Respecting the child and their geographies, and engaging them in reciprocal dialogue, is key here (Freire Citation1970) as it can be seen to empower children in connecting their everyday lives and their formal geographical education.

As both the children who took part in this research articulated, and literature reviewed in this paper highlights, schools in England currently face challenges related to accountability and performativity, and notions of knowledge as lists to be learnt. Considering the reciprocal relationships between the child’s everyday life and geographical education through drawing on children’s geographies has the potential to be a transformative idea in geography education. However, as has been highlighted by Hammond and McKendrick (Citation2020) in their research with geography teacher educators (exploring their experiences of, and perspectives on, children’s geographies), much work is to be done here. This work involves crossing ‘borders’ between children’s geographies and geography education, through opening up channels of communication between them. As has been highlighted by Horton, Kraftl, and Tucker (Citation2008), research (sharing) between the two fields can enhance knowledge of geographies of education, the spatialities of education and how children’s experiences beyond the school gate can be included in curricula. This research has added to these debates by focussing on exploring the relationships between different spaces of geographical thought, and the child’s everyday life and formal education.

In concluding this article, I make three further suggestions as to areas of future research and knowledge exchange between children’s geographies and geography education, to move debates forward. The first of these suggestions is to encourage a dialogic conversation between children’s geographers and those interested in geography education (e.g. policy makers and teachers) to consider how and why children’s geographies might be included, and furtherexplored, in school geography for children of different ages (including consideration of curriculum, pedagogy and purpose). This should include critical consideration of how and why knowledge, ideas, concepts, themes and methods developed by and/or used in research in children’s geographies might enhance geographical education. Secondly, I suggest research to explore children’s perspectives as to the value of considering children’s geographies in education and schooling would enable children to contribute to debates in, and about, education. Finally, I propose that an examination of teacher and educational policy maker knowledge of, and perceptions on, children’s geographies and their ‘place’ in school geography would further enhance knolwegdgeof borders existing between children’s geographies and geography education in schools. This research would enable children’s geographers and those interested in geography education to critically consider the significance of, and what opportunities there are, to cross borders between the fields.

Acknowledgements

My thanks go to Professor David Lambert for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. Thank you also to the anonymous peer reviewers for their constructive and developmental feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aitken, S. 1994. Putting Children in Their Place. Washington, DC: Association of American Geographers.

- Aitken, S. 2001. Geographies of Young People: The Morally Contested Spaces of Identity. London: Routledge.

- Aitken, S. 2018. Young People, Rights and Place: Erasure, Neoliberal Politics and Postchild Ethics. London: Routledge.

- BERA. 2011. Ethical Guidelines for Education Research 2011. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/bera-ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2011.

- Bernstein, B. 2000. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity: Theory, Research, Critique. Revised Edition. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc.

- Biddulph, M. 2010. “Editorial: Valuing Young People’s Geographies.” Teaching Geography 35 (3): 45.

- Biddulph, M. 2011. “Young People’s Geographies: Implications for Secondary Schools.” In Geography, Education and Future, edited by G. Butt, 44–59. London: Bloomsbury.

- Biddulph, M. 2012. “Spotlight On … Young People’s Geographies and the School Curriculum.” Geography (Sheffield, England) 97 (3): 155–162.

- Bonnett, A. 2008. What is Geography? London: SAGE Publications.

- Brenner, N., and S. Elden. 2009. “Introduction, State, Space, World: Lefebvre and the Survival of Capitalism.” In State, Space and World: Selected Essays, edited by N. Brenner, S. Elden, and G. Moore, 1–48. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

- Bruner, J. 2004. “Life as Narrative.” Social Research 71 (3): 691–710.

- Bushin, N. 2009. “Interviewing with Children in Their Homes: Putting Ethical Principles Into Practice and Developing Flexible Techniques.” In Doing Children’s Geographies, edited by L. van Blerk and M. Kesby, 9–25. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Butt, G. 2017. “Debating the Place of Knowledge Within Geography Education: Reinstatement, Reclamation or Recovery.” In The Power of Geographical Thinking, edited by C. Brooks, G. Butt, and M. Fargher, 13–26. Springer.

- Butt, G. 2020. Geography Education Research in the UK: Retrospect and Prospect. The UK Case, Within the Global Context. Switzerland: Springer.

- Butt, G., and G. Collins. 2018. “Understanding the Gap Between Schools and Universities’.” In Debates in Geography Education, 2nd ed., edited by D. Lambert and M. Jones, 263–274. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Castree, N., D. Fuller, and D. Lambert. 2007. “Geography Without Borders.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 32 (3): 317–335.

- Catling, S. 2011. “Children’s Geographies in the Primary School.” In Geography, Education and Future, edited by G. Butt, 15–29. London: Bloomsbury.

- Catling, S., and F. Martin. 2011. “Contesting Powerful Knowledge: The Primary Geography Curriculum as an Articulation Between Academic and Children’s (Ethno-) Geographies.” The Curriculum Journal 22 (3): 317–335.

- Deng, Z. 2017. “Pedagogical Content Knowledge Reconceived: Bringing Curriculum Thinking Into the Conversation on Teachers’ Content Knowledge.” Teaching and Teacher Education 72: 155–164.

- DfE. 2013. National Curriculum in England: Geography Programmes of Study. Accessed December 31, 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-geography-programmes-of-study.

- DfE. 2014. The National Curriculum in England: Framework for Key Stages 1 to 4 (updated 2 December 2014). Accessed October 8, 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-framework-for-key-stages-1-to-4/the-national-curriculum-in-england-framework-for-key-stages-1-to-4.

- DfE. 2018. Policy Paper: Reducing Teacher Workload. Accessed April 3, 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/reducing-teachers-workload/reducing-teachers-workload.

- Dorling, D., and S. Tomlinson. 2019. Rule Britannia: Brexit and the End of Empire. London: Birkbeck Publishing Ltd.

- Elden, S. 2006. “Some are Born Posthumously: The French Afterlife of Henri Lefebvre.” Historical Materialism 14 (4): 185–202.

- Fass, P. S. 2013. The Routledge History of Childhood in the Western World. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Finn, M. Forthcoming. “Questioning Recontextualisation: Considering Recontextualisation’s Geographies.” In Recontextualising Geography for Education, edited by M. Fargher, D. Mitchell, and E. Till. Switzerland: Springer.

- Finn, M., L. Hammond, G. Healy, J. D. Todd, A. Marvell, J. H. McKendrick, and L. Yorke. 2021. “Looking Ahead to the Future of GeogEd: Creating Spaces of Exchange Between Communities of Practice.” Area. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12701.

- Firth, R. 2018. “‘Recontextualising Geography as a School Subject’.” In Debates in Geography Education, 2nd ed., edited by D. Lambert and M. Jones, 275–286. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Firth, R., and M. Biddulph. 2009. “Young People’s Geographies.” Teaching Geography 34 (1): 32–34.

- Foucault, M. 1978. The Will to Knowledge: The History of Sexuality 1. Oxford: Penguin Books.

- Freeman, C., and P. Tranter. 2011. Children and Their Urban Environments: Changing Worlds. London: Earthscan Ltd.

- Freeman, C., and P. Tranter. 2015. “‘Children’s Geographies’.” In International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, edited by J. D. Wright, 491–497. London: Elsevier.

- Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin Books.

- Geographical Association. 2015. Geography Initial Teacher Education and Supply in England: A National Research Report by the Geographical Association. Sheffield: Geographical Association.

- Giddens, A. 1986. The Constitution of Society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Hammond, L. 2020. “An Investigation into Children’s Geographies and their Value to Geography Education in Schools”. Thesis (PhD), University College London.

- Hammond, L. 2020b. “‘Children, Childhood and Changing Technology’.” In Geography Education in a Digital World, edited by N. Walshe and G. Healy, 38–49. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hammond, L., and J. H. McKendrick. 2020. “Geography Teacher Educators’ Perspectives on the Place of Children’s Geographies in the Classroom.” Geography (Sheffield, England) 105 (2): 86–93.

- Harvey, D. 1990. “Flexible Accumulation Through Urbanisation Reflections on “Post-Modernism” in the American City.” Perspecta 26: 251–272.

- Hirsch, E. D. 2007. The Knowledge Deficit: Closing the Shocking Education Gap for American Children. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Holloway, S., and G. Valentine. 2000. Children’s Geographies: Living, Playing, Learning. London: Routledge.

- Hörschelmann, K., and L. van Blerk. 2012. Children, Youth and the City. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Horton, J., P. Kraftl, and G. Tucker. 2008. “The Challenges of “Children’s Geographies”: A Reaffirmation.” Children’s Geographies 6 (4): 335–348.

- Jones, M., and D. Lambert. 2018. “‘Introduction: The Significance of Continuing Debates’.” In Debates in Geography Education, 2nd ed., edited by M. Jones and D. Lambert, 1–14. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lambert, D., and M. Biddulph. 2014. “The Dialogic Space Offered by Curriculum-Making in the Process of Learning to Teach, and the Creation of a Progressive Knowledge-Led Curriculum.” Asia Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 43 (3): 210–224.

- Lambert, D., and J. Morgan. 2010. Teaching Geography 11-18: A Conceptual Approach. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Lambert, D., M. Young, D. Lambert, C. Roberts, and M. Roberts. 2014. “Subject Teachers in Knowledge-Led Schools.” In Knowledge and the Future School: Curriculum and Social Justice, edited by M. Young, D. Lambert, C. Roberts, and M. Roberts. London: Bloomsbury.

- Langevang, T. 2009. “‘Movements in Time and Space: Using Multiple Methods in Research with Young People in Accra, Ghana.” In Doing Children’s Geographies, edited by L. Van Blerk and M. Kesby, 42–56. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space (English Translation). London: Blackwell Publishing.

- Massey, D. 2005. For Space. London: SAGE.

- Massey, D. 2008. World City. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Matthews, H., and M. Limb. 1999. “Defining an Agenda for the Geography of Children: Review and Prospect.” Progress in Human Geography 23 (1): 61–90.

- Maude, A. 2016. “What Might Powerful Geographical Knowledge Look Like.” Geography (Sheffield, England) 101 (2): 70–76.

- McKendrick, J. H., and Hammond, L. 2020. “Connecting with Children’s Geographies in Education.” Teaching Geography 45 (3): 118–121.

- Middleton, S. 2017. “Henri Lefebvre on Education: Critique and Pedagogy.” Policy Futures in Education 15 (4): 410–426.

- Mitchell, D. 2019. Hyper-socialised: How Teachers Enact the Geography Curriculum in Late Capitalism. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Morgan, J. 2019. Culture and the Political Economy of Schooling: What’s Left for Education? London: Routledge.

- Morgan, J., J. Hordern, and U. Hoadley. 2019. “On the Politics and Ambition of the ‘Turn’: Unplacking the Relations Between Future 1 and Future 3.” The Curriculum Journal 30 (2): 105–124.

- Oswell, D. 2013. The Agency of Children: From Family to Global Human Rights. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Roberts, M. 2013. ““Powerful Knowledge”: To What Extent is this Idea Applicable to School Geography.” Accessed April 10, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r_S5Denaj-k&t=17s.

- Roberts, M. 2014. “Powerful Knowledge and Geographical Education.” Curriculum Journal 25 (2): 187–209.

- Roberts, M. 2017. “Geographical Knowledge is Powerful If … .” Teaching Geography 42 (1): 6–9.

- Rousell, D., and A. Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles. 2019. “A Systematic Review of Climate Change Education: Giving Children a ‘Voice’ and a ‘Hand’ in Redressing Climate Change.” Children’s Geographies 18 (2): 191–208.

- Shapiro, T. 1999. “What is a Child.” Ethics 109 (4): 715–738.

- Skelton, T. 2008. “Research with Children and Young People: Exploring the Tensions between Ethics, Competence and Participation.” Children’s Geographies 6 (1): 21–36.

- Standish, A. 2009. The False Promise of Global Learning: Why Education Needs Boundaries. New York: Bloomsbury Academic and Professional.

- van Blerk, L., and M. Kesby. 2008. Doing Children’s Geographies: Methodological Issues in Research with Young People. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Watts, M. J. 1992. “Space for Everything (A Commentary).” Cultural Anthropology 7 (1): 115–129.

- Whiting, C., G. Whitty, I. Menter, P. Black, A. Parfitt, K. Reynolds, and N. Sorensen. 2018. “Diversity and Complexity: Becoming a Teacher in England in 2015-2016.” Review of Education 6 (1): 69–96.

- Yarwood, R., and N. Tyrell. 2012. “Why Children’s Geographies.” Geography (Sheffield, England) 97 (3): 123–128.

- Young, M. 2008. Bringing Knowledge Back In: From Social Constructivism to Social Realism in the Sociology of Education. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Young, M. 2013. “‘Powerful Knowledge’: To What Extent is this Idea Applicable to School Geography.” Bringing Knowledge Back In.Accessed April 10, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r_S5Denaj-k&t=17s.

- Young, M., and J. Muller. 2010. “Three Educational Scenarios for the Future: Lessons from the Sociology of Knowledge.” European Journal of Education 45 (1): 11–27.

- Young, M., and J. Muller. 2016. Curriculum and the Specialisation of Knowledge: Studies in the Sociology of Education. Abingdon: Routledge.