ABSTRACT

Background: Concerns about falls, or fear of falling, are frequently reported by older people and can have serious consequences. Aim of this study was to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of a home-based, cognitive behavioral programme for independently-living, frail older people in comparison with usual care from a societal perspective.

Methods: This economic evaluation was embedded in a randomized-controlled trial with a follow-up of 12-months. In the trial 389 people aged 70 years or older were allocated to usual care (n = 195) or the intervention group (n = 194). The intervention group received a home-based, cognitive behavioral programme. Main outcome measures were concerns about falls and Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs).

Results: Average total costs per participant in the usual care group were 8,094 Euros and 7,890 Euros for participants in the intervention group. The intervention group showed a significant decrease in concerns about falls and a non-significant increase in QALYS in comparison with the usual care group. The probability that the intervention was cost-effective was 75% at a willingness to pay of 20,000 Euros per QALY.

Discussion: The programme is likely to be cost-effective, and therefore a useful addition to current geriatric care, particularly for those persons who are not able or willing to attend group programmes.

Trial registration: NCT01358032

1. Background

Concerns about falls, or fear of falling, are a common health problem and a threat to autonomy for independently-living older people. Depending on the target sample and measurement method, prevalence rates from 20% to 85% are reported for independently-living older adults [Citation1]. Concerns about falls are reported not only by those who have recently fallen, but also by those who have not [Citation2,Citation3]. These concerns are associated with adverse outcomes in psychosocial, physical and functional domains such as loss of balance confidence, social isolation, symptoms of anxiety and depression, avoidance of daily activities, physical frailty, falls, loss of independence, and institutionalization [Citation1,Citation4–10]. In addition to the negative consequences of concerns about falls, there is the risk of increased healthcare usage and societal costs [Citation7]. Although concerns about falls can be seen as a health problem apart from actual falls [Citation11], little is known about the societal costs.

Several reviews showed that different approaches may be successful in reducing concerns about falls [Citation12–14] and can potentially contribute to a better quality of life and independent living for older people. The multicomponent, cognitive behavioral programme ‘A Matter of Balance’ (AMB) is one of the few interventions that targets psychosocial and physical as well as functional aspects of concerns about falls [Citation15,Citation16]. This community-based group programme proved to be successful in reducing concerns about falls and associated activity avoidance without increasing the number of falls [Citation17,Citation18]. The programme consistently shows effects on a broad range of outcomes and is considered preferable to usual care in terms of costs and effects in independently-living older people [Citation17–27]. The programme comprises eight group sessions and is led by trained healthcare professionals or volunteers and has been successfully implemented in different settings, i.e. in several states of the US and nationwide in the Netherlands [Citation28–31]. Despite its success, a substantial percentage of (potential) participants do not attend or finish the programme because of health problems [Citation17,Citation32]. To enable frail, independently-living people to participate and to accommodate with their preferences [Citation33], we developed a tailor-made, home-based format (AMB-Home) [Citation34]. This new programme consists of seven individual sessions, including three home visits and four telephone contacts. The principles of the AMB programme were maintained in AMB-Home, namely to instill adaptive and realistic views about the risks of falling via cognitive restructuring and to increase activity and safe behavior using goal setting and action planning. Evaluation of the clinical effects of AMB-Home showed a significant decrease in concerns about falls in the intervention group in comparison with the usual care group [Citation35]. AMB-Home also demonstrated favorable effects regarding the reduction of associated avoidance of activity, disability and the number of indoor falls in the intervention group in comparison with the usual care group [Citation35].

Interventions that support remaining active as long as possible are important in aging societies, also in view of managing healthcare costs [Citation36]. An economic evaluation of the group programme of AMB in the Netherlands showed comparable costs in the control and intervention groups with significant clinical effects in the intervention group, which could therefore be considered as preferable to usual care [Citation23]. However, the impact of the AMB-Home programme on health-related quality of life and costs is not yet known. Consequently, in this paper we report the results of an economic evaluation using data obtained during the AMB-Home trial [Citation34]. The study aims to assess whether our individual, cognitive behavioral approach is preferable to care as usual in terms of costs and effects. We investigated whether AMB-Home leads to lower levels of concerns about falls and consequently a higher quality of life without an increase in costs, and can therefore be considered to be cost-effective. The cost-effectiveness analysis is performed from a societal perspective (healthcare, as well patient and family costs).

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

This economic evaluation was part of a two-group randomized controlled trial with a follow-up period of 12 months [Citation34]. In this economic evaluation we performed a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) and cost-utility analysis (CUA) by comparing the societal costs and effects of the intervention group with those of the usual care group from a societal perspective according to the Dutch guidelines [Citation37]. The reporting follows the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) guidelines [Citation38]. The design of this study is described in detail elsewhere [Citation34].

The selection of participants was performed in four consecutive cycles between March and December 2009 in three communities in the southern part of the Netherlands. The municipal registry offices of these communities randomly selected a total of 11,490 addresses of people in the communities aged 70 years or older. To screen for eligibility, these people received a short postal questionnaire with a free return envelope, as well as information about the trial and an informed consent form. People were included when they reported at least sometimes concerns about falls as well as associated activity avoidance, and valued their perceived general health as fair or poor (i.e. excluding participants who rate their health as excellent to good) as assessed with one item of the Medical Outcomes Study-20 (MOS-20) [Citation39], and signed the informed consent. and signed the informed consent. The MOS-20 selection criterion was used as it was assumed that participants with a fair or poor health state would be at higher risk of fear of falling and could be considered as frail. People were excluded if they were confined to bed, restricted to permanent use of a wheelchair, were waiting for nursing home admission, or experienced substantial hearing, vision or cognitive impairments. In addition, a restriction was applied to couples. Only one person of a couple was allowed to participate in the trial to prevent reciprocal influencing; lots were drawn to determine who would be included. Participants were randomly allocated to either the usual care or the intervention group. A computerized two block stratified randomisation was performed with one prognostic factor: the level of concerns about falls (sometimes, regular, often, and very often). The randomisation took place directly after the baseline measurement and was conducted by an external agency blinded to participant characteristics. The intervention group was offered seven sessions of AMB-Home to reduce concerns about falls. The usual care group did not receive an intervention. During the study period, no standard treatment for concerns about falls was available in The Netherlands. Hence, it is likely they received no treatment. The Medical Ethics Committee of Maastricht University/Academic Hospital Maastricht in the Netherlands approved the study (MEC 07-3-064).

2.2. Intervention and usual care group

‘A Matter of Balance at Home’ (AMB-Home) is an individual, cognitive behavioral programme for managing concerns about falls. The programme is comprised of seven individual sessions, consisting of three home-visits of 60, 60 and 75 minutes, respectively, and four telephone contacts of 35 minutes each. As noted, it is founded on the evidence-based group programme A Matter of Balance (AMB) which uses principles of cognitive restructuring, social modeling, education and other strategies for behavioral change [Citation17,Citation18,Citation40]. The purpose of the programme is to enable the participants to shift from maladaptive to adaptive cognitions with respect to falling and concerns about falls, instilling a realistic view the risk of falling, increasing belief in self-efficacy and feelings of control, and changing the participants’ behavior. To achieve these goals, the following strategies are applied: 1) identifying and restructuring misconceptions about falls and the risk of falling with e.g. discussions and checklists; 2) setting realistic personal goals for increasing activity levels and safe behavior by establishing e.g. action plans; and 3) promoting the uptake of old and new daily life activities that have been avoided due to concerns about falls with e.g. exposure in vivo. The programme was conducted by community nurses (n = 8) who were qualified in the field of geriatrics and worked for local home-care agencies. More details about the programme are published elsewhere [Citation34,Citation35].

The intervention period was approximately four months.

Since no standard treatment for concerns about falls was available during the study period it is likely that participants in the usual care group received no treatment, although, like the participants in the intervention group, they may have received usual care from health and community service providers or informal caregivers, depending on their needs.

2.3. Outcomes

Data were collected at baseline and at 5- and 12-month follow-up via telephone interviews.

The clinical outcome for the CEA was concerns about falls assessed by the 16-item Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I). Participants were asked to indicate how concerned they were about falling while carrying out several activities of daily living (1 = not at all concerned to 4 = very concerned; the scale is 16–64) [Citation41,Citation42]. Avoidance behavior due to concerns about falls was measured with the 16-item Falls Efficacy Scale-International Avoidance Behavior (FES-IAB), in which item is also rated on a 4-point scale (1 = not at all concerned to 4 = very concerned) leading to a range of 16–64 points [Citation35,Citation43]. Both questionnaires have been evaluated with respect to psychometric properties [Citation35,Citation41–43]. The Health Survey Short Form (SF-12)* was used to measure both health-related quality of life [Citation44] and utilities for the cost-utility analysis (CUA). The SF-12 is a self-administered questionnaire, which is widely used as a quality of life and utility instrument. The SF-12 (called SF-6D when it is used for economic evaluations) presents results in health states. Utility values are calculated for these health states, using preferences elicited from a general population, the so-called Brazier algorithm [Citation45]. The value of the utility theoretically ranges from 1, representing the best possible health state, to 0, equal to death, to below zero, states worse than death [Citation31]. These utilities were used to calculate Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs). This was done by multiplying the time spent in a specific condition (quantity of life lived) by the utility of that health state (quality of life lived) using the area under the curve method [Citation46].

Furthermore, 1-item questions on concerns about falls, the avoidance of activities owing to these concerns and the number of falls are assessed at baseline.

Data was gathered by means of telephone interviews which are conducted by trained interviewers, who were blinded for group allocation. For the assessment of fall accidents and health care use, participants received a fall calendar after the baseline measurement. Every month, a sheet of the calendar had to be returned via a freepost envelope.

Footnote: *For the SF12v1, Standard Recall, Netherlands (Dutch) an unlicensed version was used that deviates from the official version on the item about pain. The perception of pain is asked for instead of pain as barrier. Accordingly, the results should interpreted with care when comparing with SF12v1 scores from other studies [Citation47].

2.4. Health service utilization and costs

The economic evaluation is carried out from a societal perspective. This means that all costs are taken into account, irrespective of who bears the costs or gains the benefits. In this study we have assessed (1) intervention costs, (2) healthcare costs, and (3) patient and family costs. First, the costs of the programme consisted of materials used, salaries of the facilitators, costs of training sessions for the facilitators etc. Second, the healthcare costs that were included were hospital visits (both inpatient and outpatient treatment), GP consultations, and visits to allied professionals (i.e. occupational therapist, physiotherapist, and dietician). Third, the patient and family costs included (nursing) home-care, informal care, aids, and in-home modifications. Because of the complex relation between concerns about falls and a wide range of outcomes in the domains of physical, mental and social health, no distinction could be made between costs related to concerns about falls and other health care costs. Loss of productivity was not included, because all persons were above the age of retirement in the Netherlands.

Cost data were collected by means of a (monthly) cost dairy for one year [Citation48]. Participants were asked to report their use of healthcare services and the patient and family costs on a form and were required to send this in each month. See Additional file 1 for the complete questionnaire. Participants who did not return the form or had missing data were contacted by phone to ensure completion of data.

In order to estimate the costs, the volumes were multiplied by the assigned cost price of that unit. Cost prices were obtained from the Dutch guidelines for cost analysis in health care research [Citation37]. If these costs were not available in the guideline, costs were estimated by using the retail prices listed by professional organizations. Costs of healthcare devices, aids and in-home adaptations were estimated by looking on the internet for retail prices from suppliers in the Netherlands. For each product, the average price was used. All costs are expressed in 2011 Euros (€) and if necessary indexed to the baseline year using a consumer price index as suggested in the manual [Citation37]. An overview of all used prices can be found in Additional file 2. Since the time frame in which costs and effects occurred was relatively short (one year for the individual participant), discounting (a correction for time preference) was not necessary [Citation46].

2.5. Synthesizing cost and effects

To examine cost-effectiveness and cost-utility, incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) and incremental cost-utility ratios (ICURs) were calculated by dividing the difference in costs by the difference in effects (in concerns about falls and in QALYs) between the usual care group and the intervention group. The ICERs and ICURs were considered as the incremental cost per unit of additional effect [Citation46].

The ICERs were plotted in a cost-effectiveness plane (CE-plane), in which the x-axis shows the difference in effect between the intervention and usual care, and the y-axis the differences in costs between the intervention and usual care. In a CE-plane, four quadrants are shown; ICERs located in the North East (NE) indicate that the intervention was both more effective and more costly in comparison with usual care. ICERs in the South East (SE), the dominant quadrant, indicate that the intervention is more effective and less costly than usual care. ICERs in the South West (SW) indicate that the intervention was less effective and less costly than usual care, and ICERs located in the North West (NW), the inferior quadrant, indicate that the intervention was less effective and more costly [Citation46].

An intervention is preferred above usual care when there are higher effects with lower costs, and not preferred when the intervention has lower effects against higher costs in comparison with usual care. Nevertheless, when there are both higher effects and higher costs, or lower effects and lower costs, the preference for an intervention depends on how much society is willing to pay for a certain gain in effect. In the Netherlands the willingness to pay (WTP) to gain one QALY ranges from 20,000 Euro to 80,000, depending on the disease burden [Citation49]. In a recent report from the Dutch Health Care Institute, the disease burden in the Netherlands is classified into three categories, namely low with WTP up to €20,000/QALY; middle with WTP up to €50,000/QALY; and high with WTP up to €80,000/QALY [Citation50]. The disease burden of concerns about falls is not known; however, many older people see the risk of falling and concerns about falls as part of the aging process [Citation51]. Accordingly, we used a WTP of € 20,000/QALY, which is also often used for preventive interventions [Citation49,Citation50]. As for almost all clinical outcomes, no acceptable WTP level has been defined for concerns about falls so far; therefore a range is described which shows the likelihood that the intervention is cost-effective at different thresholds, i.e. Euro values for 1 point of improvement in concerns about falling.

2.6. Sensitivity analyzes

As the results of an economic evaluation are always influenced by uncertainty it is common to perform a number of sensitivity analyzes to show the results of analyzes with alternative assumptions. We performed sensitivity analyzes in which per-protocol analysis was used, in which all older persons who attended at least five sessions were included as this was considered to be minimally sufficient for intervention exposure [Citation17,Citation18]. Furthermore, sensitivity analyzes were performed from a healthcare perspective (only medical costs) to allow comparison of the outcomes with other studies, since many studies exclusively applied this perspective (see [Citation34]). In addition, the healthcare perspective is the preferred perspective in some countries, for example in the United Kingdom [Citation52]. Finally, two additional sensitivity analyzes were performed, i.e. an analysis without extreme cost outliers and an analysis with avoidance of activity due to concerns about falls as outcome for studying the cost-effectiveness of the behavioral component of the programme. Outliers were defined by a boxplot in which a point beyond the upper outer fence was considered to be an extreme outlier [Citation53].

2.7. Statistical analyzes

The intention-to-treat principle was used for the primary (base-case) analyzes, including all participants with data on costs (at least 75%, i.e. 9 out of 12 months) and clinical outcomes at 12 months, regardless of whether they received the (complete) intervention or not.

Missing values were handled according to the guidelines of the original authors who developed these measures. For the FES-I and the FES-IAB, missing values were imputed at the level of the scale by means of multiple imputations if individual data on no more than 4 items (≤25%) of the FES-I and the FES-IAB was missing [Citation54]. For the SF-12, missing data (i.e. ≤25%) was replaced by the mean of the treatment group (i.e. intervention or usual care group) [Citation45]. Missing values for the cost data were imputed by linear interpolation (i.e. imputation with participants’ mean score on the previous and next measurement) [Citation55].

Clinical outcomes were assessed using mixed-effects linear regression analyzes (maximum likelihood with fixed variables) due to multiple observation per participant, using a random intercept for every participant. Models were adjusted for the baseline value of the outcome measure, age, gender, perceived general health, and the number of falls in the 6-months period before baseline and concerns about falls (i.e. 1-item questionnaire). These covariates were considered a priori as relevant to the outcomes [Citation34]. The level of statistical significance was set at .05, one-tailed, because we expected an improvement on the outcomes.

Uncertainty around the ICERs was examined using 5,000 non-parametric bootstraps that were plotted on a cost-effectiveness plane (CE-plane). In this nonparametric method an estimation of the sampling distribution was made by simulating the original data many times. Seemingly unrelated regression equations (SURE) [Citation56] were bootstrapped (5,000 times) to allow for correlated residuals of the cost and utility equations and to account for baseline differences in age, gender, perceived general health, and the number of falls in the 6-months period before baseline and concerns about falls. Before cost-effectiveness planes (CE-planes) and incremental cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (ICEA-curve) were plotted, the total scores on the FES-I and FES-IAB were mirrored; in that way a high score on the FES-I or FES-IAB means a better state, as already holds for QALYs as outcome [Citation57,Citation58].

Statistical analyzes were performed in SPSS 21.0.1 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL); bootstrapping was done in STATA 14.

3. Results

The flow of participants during the trial is presented in . Eligibility screening occurred in the general community (see Study Design). Through randomisation, 195 participants were allocated to the usual care group, and 194 participants were included in the intervention group. The programme was started by 164 participants (85%) of the 194 participants, and 117 participants (60%) received at least five of the seven programme sessions. In the usual care group 162 participants completed the trial and 159 (82%) of them had complete data, whereas 133 participants in the intervention group completed the trial and 130 (67%) of them had complete data. Withdrawal was highest at the 5-month follow-up measurement, which was directly after the intervention period. The main reasons for being lost to follow-up were similar in the usual care and intervention group, i.e. lost interest and health problems. Baseline characteristics were comparable in both groups (). No significant differences were identified regarding baseline characteristics between dropouts in the intervention and in the usual care group (not tabulated).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and outcomes (n = 289)

3.1. Costs

As shown in , the mean costs of the intervention were 716 Euros per participant. Average total costs per participant in the usual care group were 8,094 Euros and, in the intervention group 7,890 Euros (including intervention costs). None of the (sub)categories, e.g. healthcare or family and patient costs, show a significant difference in costs between the two groups. The volumes per category are tabulated in Additional file 3.

Table 2. Mean (SD) costs in euros of healthcare utilization after 12 months (n = 289)

3.2. Clinical outcomes

The intervention group showed a significant decrease in concerns about falls in comparison with the usual care group. The estimated programme effect from baseline to the 12-month follow-up was 3.92 points on the FES-I (adjusted mean difference) (95% CI: -∞ – −2.52; P < 0.001) [Citation35]. At the 12-month follow-up no significant difference in quality of life was found between the intervention and usual care group (0.016 point on SF-6D (adjusted mean difference) 95% CI: −0.003–0.036; P = 0.16).

3.3. Cost-effectiveness

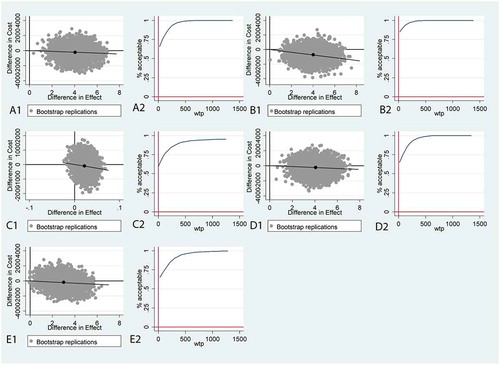

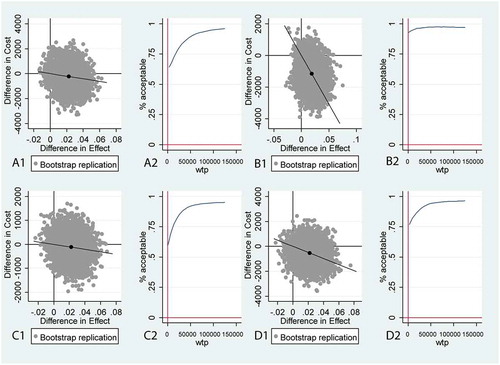

Comparing the costs and effects of the AMB-Home programme to the usual care group, the intervention was preferred over usual care (see ). The ICEA-curve () indicates that the probability of AMB-Home being cost-effective is 60 to 100% with a range of from 0 to 1500 Euros for the WTP thresholds. It can also be seen that the probability of AMB-Home being cost-effective is already 100% at a WTP of 1,300 Euros for an improvement for concerns about falls. This implies that when society is willing to pay 1,300 Euros, the programme is certainly cost-effective for a one point increase on the FES-I. The cost-effectiveness of the programme for a WTP of 20,000 Euros for one QALY is 75%. This implies that when society is willing to pay 20,000, there is a 75% probability that the programme is cost-effective for one more year of optimal health.

Table 3. Cost-effectiveness analyzes and sensitivity analyzes for concerns about falls and QALY

Figure 2. Cost-effectiveness planes (CE-planes) and incremental cost-effectiveness acceptability (ICEA) curves for concerns about falls (FES-I as outcome)

3.4. Sensitivity analyzes

As the cost-effectiveness of the programme may vary depending on the groups, perspective and outcomes that are chosen, sensitivity analyzes were performed by selecting participants on the basis of their exposure to the programme (per-protocol), from a healthcare perspective and after deleting extreme outliers. In , ICERs and the distribution of the ICERs on the CE-planes are presented for these sensitivity analyzes, both for concerns about falls and QALYs as outcomes. Overall, the probability of the cost-effectiveness of AMB-Home increased if participants received five or more sessions compared to usual care, decreased when costs were taken only from a healthcare perspective, and without outliers was rather similar to the base case analyzes. In the CE-planes and ICEA-curves for concerns about falls show that the probability that the programme is cost-effective is 99% at a WTP of 600 Euros for a one point increase on the FES-I for those who received five or more sessions (this line does not reach 100%). From a healthcare perspective, the programme is 94% cost-effective at a WTP of 1,300 Euros.

With respect to QALYs, the probability that the programme is cost-effective with a WTP of 20,000 Euros is 87% if participants received five or more sessions (). With the same WTP of 20,000 Euros and analyzed from a healthcare perspective, the probability of cost-effectiveness of AMB-Home was 73%.

Figure 3. Cost-utility planes (CU-planes) and incremental cost-effectiveness acceptability (ICEA) curves for QALYs

The range of the probability of cost-effectiveness for avoidance behavior due to concerns about falls was almost the same as for the base case analysis of concerns about falls ().

4. Discussion

In this study we assessed, from a societal perspective, the cost-effectiveness of AMB-Home, a home-based, cognitive behavioral programme for reducing concerns about falls. Average total costs per participant were 8,094 Euros in the usual care group and 7,890 Euros in the intervention group, including 716 Euros for the programme. With regard to concerns about falls as well as QALYs, the programme is likely to be cost-effective. For QALYs the probability is 75% that the programme is cost-effective at a WTP of 20,000 Euros. For concerns about falls the probability is already 100% with a WTP of 1,300 Euros. Sensitivity analyzes showed that if participants received at least five out of the seven sessions the probability that AMB-Home is cost-effective increased. When costs were assessed from a healthcare perspective, the probability of AMB-Home being cost-effective decreased.

Interestingly, a reduction in patient and family costs was observed while health care costs were relatively equal between groups. This strengthens the idea that AMB-Home may help independently-living, frail older people in supporting them to remain active as long as possible as the use of professional home care and professional domestic help lower sharply decreased in the intervention group.

Previously, studies have been conducted to examine the potential cost savings of the U.S. version of ‘A Matter of Balance’ [Citation25,Citation26]. However, as far as we know, only the Dutch group programme of an AMB has reported on the costs related to its effectiveness in the domain of concerns about falls [Citation23]. As the study of van Haastregt and colleagues did not use QALYs nor the FES-I as effect outcome measure it is difficult to compare this study with our study. However, all economic evaluations of the programme in the US and the Netherlands show the programme to be preferable in terms of costs and effects when in comparison with usual care.

Some remarks deserve attention. First, in our calculation the probability that the intervention is cost-effective regarding concerns about falls is 100% at a WTP of 1,300 Euros. However, it is difficult to determine the amount of Euros that society is WTP for concerns about falls among older people. This is a common difficulty for disease specific instruments [Citation59,Citation60]. Future research aimed at identifying maximum WTP thresholds for commonly used outcomes related to functional and psychological outcomes in older people is warranted. This would make it possible to better compare clinical effects to QALYs in economic evaluations. Second, regarding the costs, we did not include recruitment costs because the programme should be (and is) implemented within the scope of regular care. Potential participants could be referred for example by a GP, physiotherapist or community nurse. Although we expect (national) implementation costs to not be substantial, one may expect that some form of marketing would be necessary to inform GPs or other health professionals that the service is available and also convince them to introduce the services to those who would need it in practice. As the intervention has currently been embedded in 120 health care organizations throughout The Netherlands, this is not expected to hamper implementation. Finally, missing costs were interpolated using individual costs incurred before and after the missing point. This is a commonly used method; however, other methods could be also used, such as imputation of the individual mean. Hendriks and colleagues showed that the method used can influence the results [Citation55]. In our study all participants with missing values were contacted by phone to complete the data. Given the completeness of our dataset of the participants who were included in the analyzes, the impact of imputation in our study is likely to be small.

Several limitations of the present study should be noted. First, the dropout rate of study participants was substantial and different in the two study groups: i.e. 17% in the usual care group and 34% in the intervention group. Therefore, selective dropout may be an issue, although additional analyzes showed no significant differences between dropouts in the two groups with respect to the selected baseline characteristics. Second, the withdrawal from AMB-Home was high: i.e. 40% of the participants in the intervention group received less than five of seven sessions [Citation61]. Third, we were not able to adjust for potential baseline differences with respect to costs between both groups, because costs were not measured at baseline. As a result, differences in costs from the beginning of the study between the groups could have influenced the final results. Fourth, the timeframe of one year is relatively short for an economic evaluation. Therefore, it remains unclear whether the positive effects of the programme are maintained over the long term. This is especially important given the 4 months intervention period and the fact that our final follow-up assessment was conducted 12 months after baseline which is only 7 months post intervention. This relatively short follow-up may hamper comparisons with other studies that applied a more common follow-up period of 12 months after the intervention [Citation34]. Fifth, given the inclusion criteria (e.g. a perceived ‘fair’ or ‘poor’ health according to the MOS-20) our results cannot necessarily be translated to the whole population of older persons living in The Netherlands. Finally, both fall accidents and (health care) resource use were measured using monthly diaries. Despite being reported as a feasible and valid way of collecting data, the data may suffer from recall bias as the use of a cost diary requires more time from participants which may constitutes an above average burden given the population at hand [Citation48].

Despite these limitations, to our current knowledge this is the first study comparing not only the cost-effectiveness, but also the cost-utility of the cognitive behavioral programme ‘A Matter of Balance’ [Citation23,Citation25,Citation26]. Strengths of this economic evaluation were a strong study design, including longitudinal, prospective data collection, and that costs were assessed from a societal perspective in a frail population.

The adherence to AMB-Home was not optimal, and the outcomes of the per-protocol sensitivity analyzes revealed that the cost-effectiveness of the intervention is considerably higher for the group who received at least five sessions. Therefore, it should be explored if a personal intake [Citation31], and tailoring the number of sessions of the programme to the capacities, skills and preferences of the participant [Citation62] can lead to a higher adherence rate and to better results on effectiveness and costs.

4.1. Conclusions

For frail older people who are concerned about falling, AMB-Home can be considered to be good value for money, because the programme has a reasonable probability of being cost-effective. AMB-Home demonstrated no effects on quality of life, but clinical effects were shown for concerns about falls and there was a small decrease in costs. Therefore, this home-based, individualized AMB format is a useful addition to current geriatric care, and provides an alternative for those people who are not able or willing to attend group programmes.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer Disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Geolocation information

Limburg, the Netherlands

Authors’ contributions

SMAAE, TACD, GARZ and GIJMK were responsible for the conceptualization and design of the study. TACD, GARZ and GIJMK developed the materials for the study and received input from JCMvH. BFMW, TACD and SMAAE conducted the data analyzes and all authors were involved in interpreting the data. TACD and SMAAE created the first draft of this paper and the other authors provided input. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. All authors had full access to all of the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The Medical Ethics Committee of the Maastricht University/Academic Hospital Maastricht in the Netherlands approved the study (MEC 07-3-064).

Participants were required to sign an informed consent form before they could enroll in the study.

Consent for publication

By signing the informed consent, the study participants gave their approval for non-identifiable study data to be published in summary form.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (55.4 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants and the nurses from the home-care organizations “Envida” (previously: “GroenekruisDomicura”) in Maastricht, “Zorggroep Meander” in Heerlen and “Zuyderland” (previously “Orbis Thuiszorg”) in Sittard-Geleen for their participation. The Center for Data and Information Management (MEMIC), Yvonne van Eijs, Inge van der Putten and Els Rennen are acknowledged for their assistance with the data collection.

Data Availability Statement

Facilitator and participants’ manuals, as well as data and the statistical code are available on request from the corresponding author at [email protected].

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Scheffer AC, Schuurmans MJ, van Dijk N, et al. Fear of falling: measurement strategy, prevalence, risk factors and consequences among older persons. Age Ageing. 2008 Jan;37(1):19–24. PubMed PMID: 18194967.

- Legters K. Fear of falling. Phys Ther. 2002 Mar;82(3):264–272. PubMed PMID: ISI:000174242400007; English.

- Zijlstra GA, van Haastregt JC, van Eijk JT, et al. Prevalence and correlates of fear of falling, and associated avoidance of activity in the general population of community-living older people. Age Ageing. 2007 May;36(3):304–309. PubMed PMID: 17379605.

- Li F, Fisher KJ, Harmer P, et al. Fear of falling in elderly persons: association with falls, functional ability, and quality of life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003 Sep;58(5):P283–P290. PubMed PMID: 14507935; English.

- Kressig RW, Wolf SL, Sattin RW, et al. Associations of demographic, functional, and behavioral characteristics with activity-related fear of falling among older adults transitioning to frailty [Research support, non-U.S. Gov’t research support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001 Nov;49(11):1456–1462. PubMed PMID: 11890583; eng.

- Deshpande N, Metter EJ, Lauretani F, et al. Activity restriction induced by fear of falling and objective and subjective measures of physical function: a prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008 Apr;56(4):615–620. PubMed PMID: 18312314; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2645621.

- Cumming RG, Salkeld G, Thomas M, et al. Prospective study of the impact of fear of falling on activities of daily living, SF-36 scores, and nursing home admission. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000 May;55(5):M299–M305. PubMed PMID: 10819321; English.

- Boyd R, Stevens JA. Falls and fear of falling: burden, beliefs and behaviours. Age Ageing. 2009 Jul;38(4):423–428. PubMed PMID: 19420144; English..

- Delbaere K, Close JC, Brodaty H, et al. Determinants of disparities between perceived and physiological risk of falling among elderly people: cohort study. Bmj. 2010 Aug 19;341:c4165. PubMed PMID: 20724399; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2930273. English.

- Denkinger MD, Lukas A, Nikolaus T, et al. Factors associated with fear of falling and associated activity restriction in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015 Jan;23(1):72–86. PubMed PMID: 24745560.

- Clemson L, Kendig H, Mackenzie L, et al. Predictors of injurious falls and fear of falling differ: an 11-year longitudinal study of incident events in older people. J Aging Health. 2015 Mar;27(2):239–256. PubMed PMID: 25117181.

- Zijlstra GA, van Haastregt JC, van Rossum E, et al. Interventions to reduce fear of falling in community-living older people: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007 Apr;55(4):603–615. PubMed PMID: 17397441; English.

- Bula CJ, Monod S, Hoskovec C, et al. Interventions aiming at balance confidence improvement in older adults: an updated review. Gerontology. 2011;57(3):276–286. PubMed PMID: 21042008; English.

- Kendrick D, Kumar A, Carpenter H, et al. Exercise for reducing fear of falling in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11:CD009848. PubMed PMID: 25432016; English. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD009848.pub2.

- Peterson EW. Using cognitive behavioral strategies to reduce fear of falling: A matter of balance. Generations. 2002;26(4):53–59. PubMed PMID: WOS:000185520600011; English.

- Zijlstra GA, Tennstedt SL, van Haastregt JC, et al. Reducing fear of falling and avoidance of activity in elderly persons: the development of a Dutch version of an American intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2006 Aug;62(2):220–227. PubMed PMID: 16139984. .

- Tennstedt S, Howland J, Lachman M, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a group intervention to reduce fear of falling and associated activity restriction in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998 Nov;53(6):P384–P392. PubMed PMID: 9826971; English.

- Zijlstra GA, van Haastregt JC, Ambergen T, et al. Effects of a multicomponent cognitive behavioral group intervention on fear of falling and activity avoidance in community-dwelling older adults: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009 Nov;57(11):2020–2028. PubMed PMID: 19793161; eng. .

- Zijlstra GA, van Haastregt JC, van Eijk JT, et al. Mediating effects of psychosocial factors on concerns about falling and daily activity in a multicomponent cognitive behavioral group intervention. Aging Ment Health. 2011 Jan;15(1):68–77. PubMed PMID: 20924813; English. .

- Batra A, Melchior M, Seff L, et al. Evaluation of a community-based falls prevention program in South Florida, 2008–2009 [Article]. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012 Jan;9:E13. PubMed PMID: 22172180; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3277381. English.

- Page TF, Batra A, Palmer R. Cost analysis of a community-based fall prevention program being delivered in South Florida [Research support, non-U.S. Gov’t]. Fam Community Health. 2012 Jul–Sep;35(3):264–270. PubMed PMID: 22617417; eng..

- Smith ML, Jiang L, Ory MG. Falls efficacy among older adults enrolled in an evidence-based program to reduce fall-related risk: sustainability of individual benefits over time. Fam Community Health. 2012 Jul–Sep;35(3):256–263. PubMed PMID: 22617416; English..

- van Haastregt JC, Zijlstra GA, Hendriks MR, et al. Cost-effectiveness of an intervention to reduce fear of falling. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2013 Jul;29(3):219–226. PubMed PMID: 23778198.

- Cho J, Smith ML, Ahn S, et al. Effects of an evidence-based falls risk-reduction program on physical activity and falls efficacy among oldest-old adults. Front Public Health. 2014;2:182. PubMed PMID: 25964911; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4410414.

- Howland J, Shankar KN, Peterson EW, et al. Savings in acute care costs if all older adults treated for fall-related injuries completed matter of balance. Inj Epidemiol. 2015;2(1):25. PubMed PMID: 26457239; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4594092. Eng.

- Ghimire E, Colligan EM, Howell B, et al. Effects of a community-based fall management program on medicare cost savings. Am J Prev Med. 2015 Dec;49(6):e109–e116. PubMed PMID: 26385160; eng.

- Chen T, Edwards JD, Janke MC. the effects of the a matter of balance program on falls and physical risk of falls, Tampa, Florida, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:150096.

- Healy TC, Peng C, Haynes MS, et al. The feasibility and effectiveness of translating a matter of balance into a volunteer lay leader model. J Appl Gerontol. 2008 Feb;27(1):34–51. PubMed PMID: WOS:000252532900003; English.

- Ory MG, Smith ML, Wade A, et al. Implementing and disseminating an evidence-based program to prevent falls in older adults, Texas, 2007–2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010 Nov;7(6):A130. doi: onbekend. PubMed PMID: 20950537; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2995605. English.

- Ullmann G, Williams HG, Plass CF. Dissemination of an evidence-based program to reduce fear of falling, South Carolina, 2006–2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012 May;9:E103. PubMed PMID: 22632740; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3457761. English.

- Zijlstra GA, van Haastregt JC, Du Moulin MF, et al. Effects of the implementation of an evidence-based program to manage concerns about falls in older adults. Gerontologist. 2013 Oct;53(5):839–849. PubMed PMID: 23135419; Eng.

- van Haastregt JC, Zijlstra GA, van Rossum E, et al. Feasibility of a cognitive behavioural group intervention to reduce fear of falling and associated avoidance of activity in community-living older people: a process evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:156. PubMed PMID: 17900336; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2194766.

- Dorresteijn TA, Rixt Zijlstra GA, Van Eijs YJ, et al. Older people’s preferences regarding programme formats for managing concerns about falls. Age Ageing. 2012 Jul;41(4):474–481. PubMed PMID: 22367355; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3377130. eng.

- Dorresteijn TA, Zijlstra GA, Delbaere K, et al. Evaluating an in-home multicomponent cognitive behavioural programme to manage concerns about falls and associated activity avoidance in frail community-dwelling older people: design of a randomised control trial [NCT01358032]. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011 Sep 20;11:228. PubMed PMID: 21933436; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3189875. English.

- Dorresteijn TA, Zijlstra GA, Ambergen AW, et al. Effectiveness of a home-based cognitive behavioral program to manage concerns about falls in community-dwelling, frail older people: results of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):2. PubMed PMID: 26739339.

- Harper S. Economic and social implications of aging societies. Science (New York, NY). 2014 Oct 31;346(6209):587–591. PubMed PMID: 25359967; eng..

- Oostenbrink JB, Bouwmans CAM, Koopmanschap MA, et al. Handleiding voor kosten onderzoek; methoden en standaard kostprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg (Geactualiseerde versie 2010). Diemen: The Netherlands: College voor Zorgverzekeringen; 2010.

- Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS)–explanation and elaboration: a report of the ISPOR health economic evaluation publication guidelines good reporting practices task force. Value Health. 2013 Mar–Apr;16(2):231–250. PubMed PMID: 23538175.

- Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE Jr. The MOS short-form general health survey. Reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care. 1988 Jul;26(7):724–735. PubMed PMID: 3393032; English.

- Vestjens L, Kempen GI, Crutzen R, et al. Promising behavior change techniques in a multicomponent intervention to reduce concerns about falls in old age: a Delphi study. Health Educ Res. 2015 Apr;30(2):309–322. PubMed PMID: 25753146.

- Kempen GI, Zijlstra GA, van Haastregt JC. [The assessment of fear of falling with the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I). Development and psychometric properties in Dutch elderly]. Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr. 2007 Aug;38(4):204–212. PubMed PMID: 17879824.

- Yardley L, Beyer N, Hauer K, et al. Development and initial validation of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I). Age Ageing. 2005 Nov;34(6):614–619. PubMed PMID: 16267188; eng.

- Zijlstra G, Dorresteijn T, Vlaeyen J, et al. Measuring avoidance behavior due to fear of falling in community-living older adults. Gerontologist. 2013 Nov;53:199. PubMed PMID: WOS:000327442102435; English.

- Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 health survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA project. International quality of life assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998 Nov;51(11):1171–1178. PubMed PMID: 9817135.

- Brazier JE, Roberts J. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Med Care. 2004 Sep;42(9):851–859. PubMed PMID: 15319610.

- Drummond MF. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd ed. (Oxford medical publications). Oxford [etc.]: Oxford University Press; 2005.

- Personal communication with QualityMetric. October 2012.

- Goossens MEJB, MPH R-VM, Vlaeyen JWS, et al. The cost diary: a method to measure direct and indirect costs in cost-effectiveness research. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000 Jul;53(7):688–695. PubMed PMID: WOS:000088519500005; English.

- RvdVe Z. 2006. Zinnige en duurzame zorg: transparante keuzen in de zorg voor een houdbaar zorgstelsel. Zoetermeer.

- Nederland Z. 2015. Kosteneffectiviteit in de praktijk.

- McInnes E, Seers K, Tutton L. Older people’s views in relation to risk of falling and need for intervention: a meta-ethnography. J Adv Nurs. 2011 Dec;67(12):2525–2536. PubMed PMID: WOS:000297837700004; English.

- Birch S, Gafni A. On being NICE in the UK: guidelines for technology appraisal for the NHS in England and Wales. Health Econ. 2002;11(3):185–191.

- NIST/SEMATECH e-handbook of statistical methods. http://www.itl.nist.gov/div898/handbook/prc/section1/prc16.htm, October 2013. [cited 2018 Nov 14]. Available from: http://www.itl.nist.gov/div898/handbook/

- Sinharay S, Stern HS, Russell D. The use of multiple imputation for the analysis of missing data. Psychol Methods. 2001 Dec 6;(4):317–329. PubMed PMID: WOS:000172907100002; English. DOI:10.1037/1082-989X.6.4.317.

- Hendriks MR, Al MJ, Bleijlevens MH, et al. Continuous versus intermittent data collection of health care utilization. Med Decis Making. 2013 Nov;33(8):998–1008. PubMed PMID: 23535608.

- Davidson R, MacKinnon JG. Estimation and inference in econometrics. Oxford: OUP catalogue. 1993.

- Briggs AH, Wonderling DE, Mooney CZ. Pulling cost-effectiveness analysis up by its bootstraps: a non-parametric approach to confidence interval estimation. Health Econ. 1997 Jul–Aug;6(4):327–340. PubMed PMID: 9285227.

- Fenwick E, Byford S. A guide to cost-effectiveness acceptability curves. Br J Psychiatry. 2005 Aug;187:106–108. PubMed PMID: 16055820.

- Clark F, Jackson J, Carlson M, et al. Effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention in promoting the well-being of independently living older people: results of the well elderly 2 randomised controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012 September 1;66(9):782–790..

- Dear BF, Zou JB, Ali S, et al. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of therapist-guided internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for older adults with symptoms of anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Ther. 2015;46(2):206–217.

- Dorresteijn TA, Rixt Zijlstra GA, Van Haastregt JC, et al. Feasibility of a nurse-led in-home cognitive behavioral program to manage concerns about falls in frail older people: a process evaluation. Res Nurs Health. 2013 Jun;36(3):257–270. PubMed PMID: 23533013.

- Simek EM, McPhate L, Hill KD, et al. What are the characteristics of home exercise programs that older adults prefer?: a cross-sectional study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2015 Jul;94(7):508–521. PubMed PMID: 25802951.