ABSTRACT

Introduction

Performance-based risk-sharing agreements (PBRSAs), between payers, health care providers, and technology manufacturers can be useful when there is uncertainty about the (cost-) effectiveness of a new technology or service. However, they can be challenging to design and implement.

Areas covered

A total of 18 performance-based agreements were identified through a literature review. All but two of the agreements identified were pay-for-performance schemes, agreed between providers and payers at the national level. No examples were found of agreements between health care providers and manufacturers at the local level. The potential for these local agreements was illustrated by hypothetical case studies of water quality management and an integrated chronic kidney disease program.

Expert opinion

Performance-based risk-sharing agreements can work to the advantage of patients, health care providers, payers, and technology manufacturers, particularly if they facilitate the introduction of technologies or systems of care that might not have been introduced otherwise. However, the design, conduct, and implementation of PBRSAs in renal care pose a number of challenges. Efforts should be made to overcome these challenges so that more renal care patients can benefit from technological advances and new models of care.

1. Introduction

The notion of payment for performance is gaining popularity in health care worldwide. No longer are health professionals or providers paid for merely delivering a service; payment is based on achieving a given level of performance. In renal care, ‘pay-for-performance’ schemes exist in a number of settings. The exact nature of these schemes varies from place to place, but in general, they are agreements between providers and payers, with the provider being rewarded for meeting a pre-agreed target, or penalized for failing to meet it [Citation1–3].

For example, in the US, the End Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program (ESRD QIP), the first-ever mandatory federal pay for performance program, was launched in 2012 as the result of an overall reform of payment models for renal care of Medicare patients, mandated by the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act (MIPPA) in 2008. The MIPPA introduced a bundled prospective payment system for outpatient dialysis services provided to Medicare beneficiaries and legislated that payment would be linked to quality performance measures [Citation1,Citation2]. Within the Quality Incentive Program (QIP), dialysis facilities that do not meet certain standards are subject to a global Medicare payment reduction of up to 2%. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) constantly update and expand the quality metrics used to assess providers through an established process. For example, for the payment year 2020, quality measures encompassed both effectiveness and safety measures, including measures such as standardized readmission and transfusion ratios, dialysis adequacy, hypercalcemia, and vascular access measures, and reporting measures to incentivize facilities to report dialysis-event data [Citation4].

In addition to the QIP, the Comprehensive ESRD Care (CEC) Model, is a specialty-specific payment model launched in 2015, as a five year initiative by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation, with the objective of improving care and reducing costs for Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD. Within the CEC, dialysis clinics, nephrologists, and other providers join to create ESRD Seamless Care Organizations (ESCOs) and provide coordinated care to their matched ESRD beneficiaries. Like the accountable care organizations (ACOs) introduced by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, ESCOs are held accountable for the clinical and financial outcomes of their beneficiaries [Citation5]. This model is currently undergoing an assessment to determine whether and how it could be implemented as a permanent program. Finally, the ESRD treatment Choice (ETC) model has been proposed but delayed owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. This would provide financial incentives to providers to offer holistic kidney option education, appoint a care coordinator, and would involve a monthly capitation payment, including adjustments based on increasing the share of home dialysis patients and kidney transplants [Citation6].

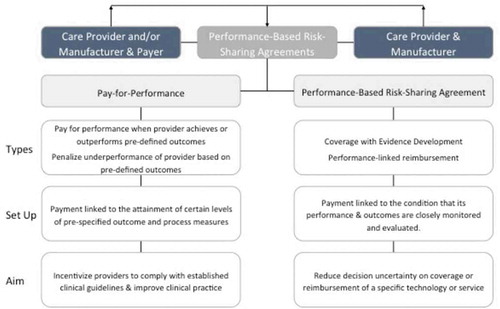

One feature of pay-for-performance schemes is that they mostly relate to the use of currently accepted treatments and procedures. The ‘performance’ being assessed relates mostly to the provider’s level of efficiency in providing current care. But what about situations where the choice is whether or not to adopt a new treatment or care model? This situation is common outside of renal care, for example, in decisions on whether or not to use an expensive new drug [Citation7]. The drug may increase survival but that is often not known with certainty when it secures a license. In these situations, a different type of performance-based agreement is used, called a performance-based risk-sharing agreement (PBRSA) [Citation8] Here, the parties to the agreement share the risk by entering into an interim arrangement to make the new treatment available, while basing the final level of coverage or payment on how well it performs in actual clinical use. (The distinction between the different types of performance-based agreements is illustrated in .)

In the case of new pharmaceuticals, and some medical devices, PBRSA are typically between the payer and technology manufacturer. However, they may also be between the manufacturer and provider, if there is a possibility that the provider can bear the extra cost of adopting the new technology within the current payment (e.g., Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG)). For example, a provider might adopt an expensive new device if it could be shown that it increased the efficiency of providing care. PBRSAs are particularly important in facilitating the adoption of new treatments or models of care. A good example is the establishment of the (reformed) Cancer Drugs Fund in the United Kingdom [Citation9]. This has provided a way of making promising, but expensive, cancer drugs available to patients without exposing the payer to considerable financial risk. If the drugs on the scheme are not as effective as was originally thought, the payer has the option to limit their use, or to reduce their price.

PBRSAs have been implemented in many areas of health care and the general challenges in the development and implementation of schemes have been discussed [Citation8,Citation10–12]. The purpose of this paper is to explore their potential in the field of renal care. This field is relevant given the high economic burden and the uncertainties surrounding the economic consequences of adopting new technologies in chronic diseases, where expenditure is continuous and ‘savings’ may be hard to realize. First, it reports the results of a literature review, conducted in order to identify any existing PBRSAs in the public domain and the opportunities and challenges of these agreements more generally. Secondly, two hypothetical case studies are developed to analyze the applicability of risk-sharing agreements in terms of opportunities and barriers for implementation in renal care.

2. Methods

First, a scoping review of the available literature was conducted up until September 2018 using relevant items from the PRISMA checklist as guidance [Citation13,Citation14]. The bibliographic databases searched were Ovid (including Medline), Embase and Web of Science. The eligibility criteria for inclusion were defined as follows: (i) Condition/disease: any stage of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and related complications (ii) Scope: studies discussing main characteristics, challenges, and/or opportunities of existing performance-based risk-sharing arrangements in renal care, or other schemes where payments for renal care are made conditional on the assessed performance of the technology. All types of studies, except for meeting abstracts, were included if published in English. Editorials were assessed on a case-by-case basis, to determine if they discussed relevant aspects of risk-sharing agreements.

The full strategy used for identifying relevant records is reported in Appendix 1.A search for ‘unpublished’ or ‘gray’ literature was also performed on Google using different combinations of the original search terms and the New York Academy of Medicine Grey Literature report. One reviewer performed the literature search, screened the records, and extracted the data from the included studies.

Since there is not always agreement on what constitutes a PBRSA, and these types of schemes are known under many different names, a broad search strategy was adopted encompassing all types of performance-based schemes, including pay-for-performance (P4P) schemes. Subsequently, the types of arrangements discussed in the identified records were classified by the authors as either PBRSAs or P4P arrangements. PBRSAs were identified using the five criteria proposed in the taxonomy by Garrison et al. [Citation8] (), whereas P4P schemes were defined as schemes whose main objective is to improve quality of care by tying reimbursement to metric-driven outcomes, best practices, and/or patient satisfaction, rather than to reduce decision uncertainty on coverage or reimbursement of a specific new technology or service [Citation15,Citation16].

Data from the identified studies were extracted according to a predefined extraction template, which included the target patient population (e.g. chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 3 to 5, End-Stage Renal Disease patients); the name and description of any performance-based risk-sharing agreement included; and the country or setting where the scheme was implemented. In addition, information on the challenges or success factors for the schemes was collected including data on their desirability/appropriateness, design, implementation, and evaluation of the outcomes obtained.

Second, since the review only identified schemes at the national level, two hypothetical case studies were developed reflecting different situations in which a PBRSA could be relevant locally: (i) an agreement related to the adoption of a new technology or service (Water Quality Management); and (ii) an agreement related to the adoption of a new model of care (Integrated Chronic Kidney Disease Programme). In each case, the opportunities for a risk-sharing agreement and the key features of such an arrangement were discussed, including the outcome(s) to be monitored, the design for data collection, the likely time horizon for the agreement, and the possible financial arrangements.

3. Results

3.1. Literature review

In total, 1256 non-duplicate records were identified from the selected bibliographic sources, and 99 potentially relevant papers were retrieved for full-text analysis, after the initial title and abstract screening. Of these, 42 records were discarded as they discussed schemes such as disease management or continuous quality improvements, where data collection and performance monitoring were not linked to payment or reimbursement of the technologies or service concerned. Another 20 studies were excluded as they did not discuss any challenges or success factors of the schemes, and a further 19 studies were excluded for not meeting one or more of the other inclusion criteria. The flowchart (PRISMA diagram) of the study selection process is shown in . Finally, 18 records met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. Of these, 16 were classified as discussing P4P schemes, and 2 were classified as discussing PBRSAs. Details of all the records identified are given in Appendix 2.

The two papers addressing PBRSAs mainly discussed the potential of these schemes to overcome the specific challenges of collecting clinical evidence in nephrology and reducing uncertainty in decision-making concerning the adoption of a specific technology or model of care [Citation17,Citation18]. In both studies, the authors comment that a coverage with an evidence development scheme, where coverage of a technology or service is made conditional on the collection of further clinical data, may be desirable from the perspectives of payers, manufacturers, and patients. In fact, the rationale behind proposing PBRSAs in renal care resides in the fact that new treatments may have high potential, but there are both challenges and a lack of encouragement for manufacturers to conduct high-quality studies such as RCTs, particularly those assessing hard clinical endpoints [Citation7,Citation8]. The two papers are summarized in Box 2 below.

Box 1. Key Characteristics of PBRSAs

Box 2. Structured summary of the papers discussing PBRSAs

3.2. Case studies

The literature review outlined a number of the challenges in designing and conducting performance-based schemes in renal care. However, although 18 records in total were identified, only 2 of these discussed PBRSAs. All the schemes identified were national schemes, mainly aimed at improving clinical practice and case management by defining a set of financial incentives linked to certain pre-specified process and outcome quality measures. No schemes at the local level were identified where the risk of residual uncertainties in the performance of potentially innovative technologies for renal care is shared between the manufacturer and the payer or health care provider. This may have been because such schemes do not exist in renal care, or because many of the details of schemes agreed between individual manufacturers and providers are confidential, precluding publication. Therefore, we developed two hypothetical case studies based on situations in renal care for which we were aware that schemes existed or were being planned. In selecting the cases we chose one to relate to the introduction of a new technology and service and one relating to the adoption of a new care model. The key characteristics of the two potential schemes are summarized in .

Table 1. Key characteristics of potential schemes

3.3. Water quality management

This is an example of an agreement between a technology manufacturer and dialysis provider concerning the adoption of a new service at the hospital or provider level. Patients undergoing conventional dialysis three times per week are exposed to 300–600 liters of water per week. Dissolved chemical contaminants, or bacterial and/or endotoxin contamination of the dialysis water, and/or dialyzate can threaten the health, or even the life, of a hemodialysis patient [Citation19]. The source of water used in HD consists basically of drinking water, purified by various techniques, whose composition and quality depend on the raw water’s parameters. The quality of the water can change from season to season, or even from day to day. Therefore, monitoring the quality of the water used for dialysis is a vital aspect of HD treatment.

From the dialysis provider’s perspective, ensuring the quality of the water can be time consuming and, if the quality falls below the acceptable level, this can be disruptive to dialysis services. Therefore, there may be value in a service that guarantees and takes legal responsibility for water quality and assumes the risk of any adverse consequences of poor water quality, for example, by a purification system that incorporates continuous monitoring of water quality, providing the provider with documentation, checking pre-treatment parameters on a daily basis (e.g. chlorine level). Since such a service would only be available at a cost, the dialysis provider would need reassurance that it was good value for money and, as long as that is uncertain, may be hesitant to contract for the service.

The PBRSA could be informed by a health technology assessment undertaken at the hospital level [Citation20]. In order to establish the PBRSA, information would be required on the cost of water testing procedures currently in place in the dialysis center concerned. In several jurisdictions, testing algorithms have been specified [Citation21]. In addition, data would be required on the probability of disruption and any consequences of problems with water quality. The data on these events may be hard to obtain for a particular dialysis center, given their likely low frequency of occurrence, so estimates may have to be made based on the literature, or on the broader experience of dialysis centers in the location concerned.

In this case, the PBRSA would be between the manufacturer of the water testing system and the provider. There are a number of ways the financial aspects of the PBRSA could be constructed. One option would be a two-part tariff, the first part being a rental charge based on the cost of the water testing system that the service replaces. Then, the second part could consist of a ‘bonus’ for ensuring water quality during the period of the agreement. Under this approach the water service provider would receive a financial penalty if water quality was not guaranteed.

3.4. Integrated Chronic Kidney Disease Programme

The establishment of an Integrated Chronic Kidney Disease (ICKD) program is an example of the adoption of a new care model. As patients progress through the different stages of chronic kidney disease, their quality of life is likely to decrease [Citation22] and the cost of their care is likely to increase [Citation23]. This process may include more frequent hospitalizations, culminating in the need for renal replacement therapy (RRT). Therefore, any intervention that has the potential to delay progression and to reduce complications of disease may be associated with considerable benefits in terms of improved health and, depending on the exact disease and treatment profile, resource savings. The objective of establishing an ICKD program is to reduce hospitalization, delay progression, and ease the transition to RRT by providing more integrated management of care, beginning in the earlier stages of disease [Citation24]. Specifically, an ICKD program could have any or all of the following elements: (i) disease detection and stratification of patients based on their risk of adverse events, to allocate resources efficiently; (ii) patient-centered care management, supported by a care manager to educate, coach, and coordinate; and (iii) monitoring of vital parameters and patient-reported outcomes at home to avoid complications and foster compliance with therapy. Such a program might be offered to patients when they enter CKD stage 3.

However, such a program would incur costs, including the appointment of a care manager, the resource implications of care and services prescribed under the program, educating patients, and negotiations with existing staff about new methods of working, e.g. telemonitoring. Of course, depending on the effectiveness of the new model, these costs could potentially be offset by reductions in hospitalizations, delays in the transition to RRT, and smoother transitions when a patient is in need of RRT. There is some evidence suggesting the existence of these benefits [Citation25–27], but dialysis providers may still be uncertain that they would be realized in their setting. Moreover, providers reimbursed through fee-for-service may not be sufficiently incentivized to implement this program without a change in payment arrangements (e.g. to prevent income losses). Therefore, ICKD programs could be candidates for a PBRSA, in order to gather evidence to convince both dialysis providers, patients, and payers.

The design of the PBRSA could be based on a traditional prospective randomized controlled trial, with patients being assigned to the ICKD program or not. However, given the time and cost of conducting an RCT, it is more likely that such a PBRSA would be based on a before/after study, whereby historical data on costs and outcomes would be gathered and compared with data gathered in a prospective study after the implementation of the ICKD program. The ‘before’ cohort could be constructed using the records of patients reaching Stage 3 over the past 2–3 years and extracting data on the subsequent interventions received, hospitalizations incurred, time to RRT, and successfully adhering to that RRT. The ‘after’ cohort could be constructed by following patients enrolled in the ICKD program and collecting the same data prospectively, over the same 2–3 year period. In addition, quality of life could be measured as the patient’s health state changed. Such a study design would pose challenges, in matching, or adjusting for differences in, the two cohorts and taking account of any other changes in service provision over time that might affect the comparison.

As in the previous examples, the detailed financial aspects of the PBRSA would have to be negotiated and would depend on who is bearing any increased cost of the ICKD program. Therefore, it would be important to assess the costs and benefits from different perspectives, such as the payer, provider, and patient. This is because costs and savings might accrue to different parties. For example, the provider may incur the costs of implementing the ICKD program, but may not save costs if the hospitalizations fell on another budget. The analysis would help determine whether any financial transfers would be necessary to implement the ICKD program on an on-going basis. Specifically, if the reduction in hospitalizations benefited the payer but not the provider adopting the CKD program, it may be worthwhile for the payer increasing the level of reimbursement to the provider of the renal care to encourage that provider to implement the program. This would also be the case if the payer could be convinced of the quality of life benefits of integrated care, through both delaying RRT and in easing the transition to RRT. Therefore, in this case the PBRSA would most likely be an agreement between the provider and the payer, with the payer providing temporary reimbursement and agreeing to increase the level of reimbursement permanently if it could be demonstrated that there were cost offsets, or improvements to the quality of care.

4. Discussion

Performance-based risk-sharing agreements can work to the advantage of patients, health care providers, payers, and technology manufacturers, particularly if they facilitate the introduction of technologies or systems of care that might not otherwise have been introduced [Citation8]. However, they require careful design and implementation [Citation12]. No performance-based risk-sharing arrangements (PBRSAs) were found in the renal care literature and only two papers discussed the potential for such schemes. This may be because many of these arrangements are agreed at the local level between health care providers and technologies manufacturers. They may also involve confidential elements and therefore the incentives to publicize them may be low.

In order to illustrate the potential and challenges of PBRSAs, we developed two hypothetical case studies. These illustrated a number of issues that have been discussed in the literature outside renal care. First, PBRSAs can potentially involve a number of key parties, including the technology manufacturer, health care provider, and patient. In order for these arrangements to be successful, the various parties need to work together to address the following challenges: defining the value proposition for the new technology or system of care, identifying the outcome(s) of interest, determining the study design, defining the data collection and monitoring arrangements, determining the actions following the conclusion of the scheme and financing the scheme. indicates the roles and responsibilities of the various parties.

Table 2. Roles and Responsibilities in PBRSAs

There is no doubt that the design, conduct, and implementation of PBRSAs in renal care pose a number of challenges [Citation10], but these have been overcome in other areas of health care [Citation7]. Therefore, efforts should be made to overcome these challenges in renal care, so that more patients can benefit from technological advances and new models of care, while protecting the interests of payers, health care providers, technology manufacturers, and patients. This will require more discussions between the three major parties in these agreements (payers, providers, and technology manufacturers), about the potential benefits to be obtained and the incentives required to implement them.

5. Expert opinion

There is a growing interest in the use of performance-based risk-sharing agreements (PBRSAs) in all fields of health care. These agreements are particularly useful in situations where there is uncertainty about the effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of a new technology, treatment, or care plan. Under these arrangements a new treatment can be funded on the condition that further data are collected to demonstrate the effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of the treatment concerned. The potential advantage of these arrangements is that patients can obtain early access to promising new treatments or technologies, because the risk to the provider or payer of health care is minimized, by making future payment or approval of the new intervention dependent of the results obtained in practice.

However, although our review of the renal care literature found many examples of pay-for-performance schemes relating to improved performance in existing care, but there was little discussion of PBRSAs relating to the introduction of new treatments or care plans. One potential reason for this could be that, unlike the PBRSAs concerning new medicines which typically involve the manufacturer and national payer, agreements in renal care also involve the provider. Local agreements between the manufacturer and provider are unlikely to be published in the literature. However, the issues in developing and implementing these schemes can be illustrated by hypothetical case studies. For example, as in the case of Water Quality Management, the arrangement could be between the manufacturer and provider alone and be agreed at the local level. Such agreements are unlikely to be published in the literature. Alternatively, in the case of an Integrated Chronic Kidney Disease Programme, the agreement could potentially involve all three parties, or be between the provider and payer. This complicates matters if a manufacturer has to convince a provider of the advantages of a new treatment or care plan, who then has to bear any additional cost of the new intervention unless the payer can be convinced to increase the payment bundle to fund it.

This points to another possible reason why PBRSAs are less common in renal care than for medicines; the way new treatments of care plans are funded. In the case of a new medicine, if a payer, being convinced of the additional benefit, feels that a drug should be made available to patients, an additional payment can be made to include it on the national or local formulary. However, in the case of new treatments or care plans in renal care, the increase in funding would have to be through a revision of the bundled payment to the provider. These payments are not easily increased to accommodate changes in the model of care, especially if it is not clear what proportion of the benefits of the new intervention go to the provider in terms of cost-offsets, or to patients in terms of improved patient care, which the payer may consider worth paying for.

Therefore, in developing PBRSAs in renal care several complexities need to be addressed, including (i) establishing the value proposition underlying the new treatment, technology, or care plan, (ii) identifying the outcomes, in costs and effects, that will be measured, (iii) agreeing the arrangements for data collection and analysis, (iv) financing the study, and (v) determining the roles and responsibilities of the various parties to the agreement.

Despite the challenges, the potential benefits from establishing PBRSAs in renal care are considerable. Therefore, health care partners, providers, and payers with an interest in these schemes should benefit from the findings of this research, with the hope that a number of such arrangements will be developed in the future. The major beneficiaries of such a collaboration will be patients, who would benefit from access to new technologies, treatments, and services.

Looking to the future, it might be possible to change the focus of some of the existing pay-for-performance schemes to encourage the adoption of new treatments of care plans if these have the potential to improve the quality of care. Some of the schemes could be designed as PBRSAs, where the bundled payment is increased on the condition that data are collected to establish whether health outcomes are improved, or cost offsets are generated. These data could then be used to determine the revised payment level at the end of the scheme. This would bring renal care more into alignment with other fields of health care, where ways are being found to make promising new treatment available, while sharing the financial risk between payers, providers, and manufacturers.

Article highlights

Performance-based risk-sharing agreements are attracting considerable interest in health care, as they offer potential benefits to patients, technology manufacturers, health care providers and payers.

Despite this interest, progress in establishing these agreements has been slow and has been mainly limited to new medicines.

The field of renal care is a potential candidate for these agreements, since it consists of a range of expensive long-term services, the quality or cost-effectiveness of which could be improved.

This paper adds to our knowledge by identifying a number of such agreements in renal care, describing their key characteristics.

Performance-based risk-sharing agreements can be complex in the field of renal care, requiring agreement by payers, providers and technology manufacturers on a number of key issues in the design, conduct and evaluation of schemes.

These complexities are illustrated by the use of two hypothetical case studies.

Overall, there is further scope for PBRSA in renal care, providing the main challenges can be overcome.

Reviewers disclosure

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Declaration of interest

Ellen Busink, Christian Apel, and Dana Kendzia are employees of Fresenius Medical Care. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2016-11-04/pdf/2016-26152.pdf and https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/ESRDQIP/Downloads/PY-2020-Final-Rule-NPC-v10.pdf]; https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/comprehensive-esrd-care/

4. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/quality-outcome-framework-report-of-the-review.pdf

References

- Gupta N, Wish JB. Do current quality measures truly reflect the quality of dialysis? Semin Dial. 2018;31(4):406–414.

- Weiner D, Watnick S. The ESRD quality incentive program—can we bridge the Chasm? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017(28): 1697–1706.

- Desai AA, Garber AM, Chertow GM. Rise of pay for performance: implications for care of people with Chronic Kidney Disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(5):1087–1095.

- CMS.Org - Laws & Regulations [Internet]. [ cited 2020 Dec 30]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/ESRDQIP/05_LawsandRegs

- Pham HH, Cohen M, Conway PH. The Pioneer Accountable Care Organization Model: improving Quality and Lowering Costs. JAMA. 2014;312(16):1635.

- Executive Order on Advancing American Kidney Health [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-advancing-american-kidney-health/ (Accessed 05 February 2020).

- Dabbous M, Chachoua L, Caban A, et al. Managed Entry Agreements: policy Analysis From the European Perspective. Value Health. 2020;23(4):425–433. .

- Garrison LP, Towse A, Briggs A, et al., Performance-Based Risk-Sharing Arrangements—Good Practices for Design, Implementation, and Evaluation: report of the ISPOR Good Practices for Performance-Based Risk-Sharing Arrangements Task Force. Value Health. 16(5): 703–719. 2013. .

- NHS England Cancer Drugs Fund Team. Appraisal and Funding of Cancer Drugs from July 2016 (including the new Cancer Drugs Fund) - A new deal for patients, taxpayers and industry [Internet]. NHS England; 2016. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/cdf-sop.pdf(Accessed 05 February 2020).

- Reckers-Droog V, Federici C, Brouwer W, et al. Challenges with coverage with evidence development schemes for medical devices: A systematic review. Health Policy Technol. 2020;9(2):146–156. S2211883720300137. .

- Stafinski T, McCabe CJ, Menon D. Funding the Unfundable: mechanisms for Managing Uncertainty in Decisions on the Introduction of New and Innovative Technologies into Healthcare Systems. PharmacoEconomics. 2010;28(2):113–142.

- Drummond M. When do performance-based risk-sharing arrangements make sense? Eur J Health Econ. 2015;16(6):569–571.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and Explanation. Ann Inter Med. 2018;169(7):467. .

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339(jul21 1):b2535–b2535. .

- Mannion R, Davies HTO. Payment for performance in health care. BMJ. 2008;336(7639):306–308.

- Hahn jim. Pay-for-Performance in Health Care. Washington DC. Congressional Research Service (CRS); 2006.

- Mendelssohn DC, Manns BJ. A Proposal for Improving Evidence Generation in Nephrology. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(1):13–18. .

- Mendelssohn DC, McFarlane P. Conditionally Funded Field Evaluations-A Solution to the Economic Barriers Limiting Evidence Generation in Dialysis?: FIELD EVALUATIONS IN DIALYSIS. Semin Dial. 2011;24(5):556–559. .

- Boccato C, Evans DW, Lucena R, et al. Water and dialysis fluids. a quality management guide; 2015.

- AdoptHTA. The AdHopHTA handbook: a handbook of hospital-based health technology assessment [Internet]. 2015. Available from: www.adhophta.eu.(Accessed 05 February 2020).

- British Columbia Provincial Renal Agency (BCPRA) Hemodialysis Committee. In: Dialysate Water System Microbiology & Endotoxin Sampling. Vancouver: British Columbia Provincial Renal Agency (BCPRA); 2016.Pages 1-8

- Nguyen NTQ, Cockwell P, Maxwell AP, et al. Chronic kidney disease, health-related quality of life and their associated economic burden among a nationally representative sample of community dwelling adults in England. In: Bolignano D, editor. PLOS ONE. Vol. 13. 2018. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207960.

- ReNe (Renal Lombardy Network), Additional contributors from ReNe Network, Roggeri A, Roggeri DP, Zocchetti C, et al. Healthcare costs of the progression of chronic kidney disease and different dialysis techniques estimated through administrative database analysis. J Nephrol. 2017;30(2):263–269.

- Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP, Streja E, et al. Transition of care from pre-dialysis prelude to renal replacement therapy: the blueprints of emerging research in advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(suppl_2):ii91–ii98. .

- Fishbane S, Agoritsas S, Bellucci A, et al. Augmented Nurse Care Management in CKD Stages 4 to 5: A Randomized Trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(4):498–505. .

- Hopkins RB, Garg AX, Levin A, et al. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of a Randomized Trial Comparing Care Models for Chronic Kidney Disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(6):1248–1257. .

- Chen PM, Lai TS, Chen PY, et al. Multidisciplinary Care Program for Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease: reduces Renal Replacement and Medical Costs. Am J Med. 2015;128(1):68–76. .

Appendix 1 Search terms

Appendix 2 Details of the Performance-Based Schemes Identified in the Review

In the review, four countries were identified where P4P schemes have been implemented in renal care, namely the US, the UK, Australia (state of Queensland) and Taiwan. In the US, the ESRD Quality Incentive Program (QIP) was introduced in 2011 by the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act (MIPPA) together with a bundled prospective payment system for renal dialysis services provided to Medicare beneficiaries. Within the QIP, dialysis facilities that do not meet certain standards in a particular year are subject to a global Medicare payment reduction of up to 2% in the ‘payment year,’ which is 2 years after the year of assessment [Citation9]. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) constantly update and expand the quality metrics used to assess providers through an established process. For example, for the payment year 2020, quality measures encompassed both effectiveness and safety measures, including measures such as standardized readmission and transfusion ratios, dialysis adequacy, hypercalcemia, and vascular access measures, and reporting measures to incentivize facilities to report dialysis-event data. There are 36 ESRD Seamless care Organizations (ESCOs) in the US participating in the Comprehensive ESRD Care Model, which is designed to identify, test, and evaluate new ways to improve care for Medicare beneficiaries with end-stage renal disease.Footnote1

In the UK, the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) was introduced in 2004 as part of the General Medical Services Contract for primary care providers (PCPs). The QOF is a voluntary reward and incentive program rewarding GP practices for delivering interventions and achieving patient outcomes using evidence-based indicators developed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)Footnote2 . QOF indicators also include four qualities and reporting measures for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), including incentives to establish the development of a register of patients with CKD (categories G3aA1 to G5A3 – previously stage 3–5); promote improved BP control, and treatment with renin-angiotensin system antagonists where appropriate [Citation10]Footnote3 . Recently, the QOF has undergone a review process with the ultimate aims of determining future priorities of the scheme, and developing proposals for reform that may help to address these prioritiesFootnote4 . Future changes in the scheme have been announced including a revision of existing indicators.

In the Australian state of Queensland, the Clinical Practice Improvement Payment Project (CPIP) was a P4P program introduced by the health authority in 2008 and terminated in 2013 after the project underwent an external review. The program awarded clinical units that achieve pre-specified process and outcome targets including vascular access management with functional arteriovenous fistula, arteriovenous graft, or Tenckhoff catheter, and patients screening and treatment for dialysis or transplant-related infections. Notably, payments to individual renal units were to be used for investments in quality improvement, education, training, and research.

Finally, in Taiwan, a nationwide pre-ESRD P4P care program was launched in 2006 to provide more comprehensive care to patients with advanced CKD through a multidisciplinary integrated care model [Citation11]. Under the pre-ESRD P4P scheme, health care providers receive additional bonus payments for attaining a set of pre-specified process and outcome indicators related to patient enrollment, comprehensive patient education, annual evaluation, and four types of case management (CKD patients at stage 3b-4, CKD patients at stage 5, patients with proteinuria, and continuous case management for all CKD patients and those with proteinuria). Process indicators include the provision of physician care, nursing care, dietician services, and data management at patient enrollment, the provision of comprehensive education and dietician services at each follow-up visit, and the provision of annual physical examinations. In addition, providers are encouraged to achieve minimal levels of quality indicator targets (e.g. blood pressure < 130/80 mmHg, total cholesterol/triglyceride < 200 mg/dL, serum albumin > 3.5 g/dL, HbA1c < 7.5%, and hematocrit > 28%). Outcome indicators, depending upon the health status of an enrolled patient with CKD, include reductions in the estimated values of glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), time to initiating dialysis or receiving kidney transplantation, use of erythropoietin, peritoneal dialysis, and outpatient dialysis, creation of vascular access before dialysis, and achievement of complete remission of proteinuria (UPCR < 200 mg/g) [Citation12].

Since the aim of the described schemes is to improve clinical practice by financially rewarding good performers (or by penalizing bad performers), a general concern reported in the identified studies was about whether the schemes would be able to achieve their objectives without resulting in distortions in care, or unintended negative consequences. For example, in the US QIP, a recurrent challenge referred to the possibility that, in the absence of an adequate case-mix adjustment mechanism, providers would game the scheme by ‘cherry-picking’ healthier patients for whom the expected financial gains would be maximized. In addition, the appropriateness of the quality measures used to determine payment was another recurrent topic. Particularly, measures were required i) to be underpinned by solid clinical evidence; ii) to be correlated with final health outcomes and to reflect patient preferences (e.g. survival, but also patients’ comfort, satisfaction with care, and quality-of-life); iii) to be actionable by or directly attributable to the recipients of the financial incentives; iv) to be independent from other processes and not leading to unintended consequences; and v) to be easily measurable with the available data sources and data infrastructure.

Further aspects concerning the design of the schemes related to the appropriate size of the incentives or penalties that would be required to prompt a change in clinical practice; the choice of the target recipient of the incentives, for example, the individual providers or facility/organization level; or the need for alignment of the incentives across the different specialties involved in the process of care beyond nephrologist and dialysis facilities (e.g., endocrinologists, cardiologists, vascular surgeons, and participating caregivers including nurses, dieticians, social workers, and pharmacists) [Citation13].

For example, in ESRD care, clinical investigations are often hampered by the relatively low number of patients treated in individual dialysis units, resulting in the need for high-cost multi-center studies to provide evidence on final clinical outcomes, such as survival [Citation8]. In addition, the lack of validated surrogate outcomes predicting survival limits the possibility to decrease study size, complexity, duration, and therefore the high cost of the required clinical studies. Lastly, ESRD patients are exposed to both traditional risk factors (e.g. cardiovascular risk) and non-traditional uremia or dialysis-related risk factors, so that single interventions that work very well in non-dialysis patients may not be effective in dialysis patients. This in turn requires that interventions that have been proven to be successful in the general population should generally be retested in dialysis patients.

The 18 studies are summarized in Table A2.1 below.

Table A2 .1. Details of the schemes identified

[Citation9Footnote5Footnote6 [Citation10]Footnote7Footnote8 [Citation11 [Citation12 [Citation13