ABSTRACT

Background

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) is an ultra-rare, genetic disorder of heterotopic ossification within soft, connective tissues resulting in limited joint function and severe disability. We present results from an international burden of illness survey (NCT04665323) assessing physical, quality of life (QoL), and economic impacts of FOP on patients and family members.

Methods

Patient associations in 15 countries invited their members to participate; individuals with FOP and their family members were eligible. The survey was available online, in 11 languages, from 18 January–30 April 2021. Participants responded to assessments measuring joint function, QoL, healthcare service and living adaptation utilization, out-of-pocket costs, employment, and travel.

Results

The survey received 463 responses (patients, n = 219; family members, n = 244). For patients, decreased joint function was associated with reduced QoL and greater reliance on living adaptations. Nearly half of primary caregivers experienced a mild to moderate impact on their health/psychological wellbeing. Most primary caregivers and patients (≥18 years) reported that FOP impacted their career decisions.

Conclusions

Data from this survey will improve understanding of the impact of FOP on patients and family members, which is important for identifying unmet needs, optimizing care, and improving support for the FOP community.

1. Introduction

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP; OMIM #135100) is an ultra-rare, severely debilitating genetic disorder characterized by congenital malformations of the great toes and progressive heterotopic ossification (HO), which transforms soft, connective tissues into heterotopic bone [Citation1,Citation2]. Other common signs of FOP are proximal medial tibial osteochondromas, cervical spine malformations, short/broad femoral necks, hearing impairment, and shortened thumbs [Citation3]. The estimated prevalence of FOP is 1.36 per million people (range: 0.036–1.428); the reported prevalence varies by country and region [Citation4–6]. Approximately 97% of all people with FOP carry the same specific mutation in the ALK2/ACVR1R206H gene, which encodes a receptor involved in the bone morphogenetic protein signaling pathway; this mutation results in a dysregulated pathway and abnormal bone growth [Citation7,Citation8]. People with FOP experience sporadic episodes of often-painful soft tissue swelling, or flare-ups [Citation9]. While some flare-ups regress spontaneously, many appear to lead to HO [Citation9]. FOP progression can also occur in the absence of flare-ups [Citation10].

The symptoms of FOP typically begin in childhood, with 93% of people first experiencing symptoms before 18 years of age [Citation5]. One of the primary symptoms of FOP is HO, which is permanent, accumulates over time, and leads to severe functional limitations in joint mobility and progressive disability; most people with FOP require a wheelchair by their third decade of life [Citation11,Citation12]. In addition, HO increases the risk of health morbidities such as fractures [Citation13], severe restrictive lung disease [Citation13], scoliosis [Citation13], pressure ulcers [Citation13], severe weight loss due to jaw ankylosis [Citation13], gastrointestinal issues [Citation14], hearing impairment [Citation15], and acute and chronic pain [Citation16]. People with FOP also experience high rates of hospitalization; in the 12 months prior to enrollment in the FOP Registry (a global disease registry operated by the International FOP Association [IFOPA] containing the largest and most detailed collection of clinical and medical information on people living with FOP), 27% of individuals had been hospitalized, with the most common reasons for admission being pain management (8.4%), fall/injury/accident/fracture (7.9%), and respiratory infection (4.4%) [Citation14,Citation17]. The highest rate of hospitalization was observed in those aged <9 years [Citation14]. Furthermore, life expectancy for people with FOP varies widely; the median life expectancy for people with FOP is estimated to be 56 years of age, with death often caused by cardiorespiratory complications [Citation12].

For most people with FOP around the world, there are no approved disease-modifying treatments available, so management is supportive and focuses on minimizing risk of flare-up triggers, managing pain and comorbidities, and providing assistive care [Citation13]. Avoidance is a common management tactic, as a minor trauma for a person with FOP can lead to a flare-up that results in HO and disease progression [Citation13]. People with FOP may avoid activities that involve busy or crowded spaces, where risk of falling is greater, and activities that cause muscular injury, such as contact sports and intramuscular injections [Citation13]. People with greater amounts of HO tend to report more limited joint function and greater difficulty conducting activities of daily living (ADLs); they benefit from assistive care aiming to prolong mobility and independence at home, school, and in the workplace [Citation18]. The need for aids, assistive devices, and adaptations (AADAs) increases with age for people with FOP, due to the progressive accumulation of HO [Citation14]. Data from the FOP Registry identified bathing attendants, drinking straws, reaching sticks, and memory foam bed mattresses as the AADAs most commonly used by people with FOP [Citation14].

Bone diseases are known to have a major physical, financial, and emotional impact on affected individuals and their family members, as well as negative consequences for quality of life (QoL) [Citation19]. While recent research has enhanced knowledge on the clinical aspects of FOP, data on the physical, QoL, social, and economic impacts of FOP are limited, as these studies did not evaluate the impact of hospitalizations and living adaptation requirements for people with progressive loss of joint function, nor did they capture the wide-ranging effects of FOP on caregivers.

Burden of illness studies are valuable tools for understanding the multifaceted impact of a disease [Citation20,Citation21]. Evaluating the impact of FOP in this way is crucial for improving access to adequate resources and support for disease management, optimizing care, and evaluating the benefits of new healthcare interventions [Citation22,Citation23]. As FOP affects all races and there is no ethnic, sex, or geographic predisposition, it is important to understand its impact on people in communities around the world [Citation7,Citation8]. Furthermore, as FOP is an ultra-rare disease with a low prevalence, collecting responses from numerous countries is important to ensure an adequate sample size. For this reason, we conducted the first international burden of illness survey (NCT04665323) to investigate the physical, QoL, social, and economic impact of FOP on individuals and their family members.

2. Methods

2.1. Survey design and participants

The survey was co-created by FOP community advisors and a team of researchers employed or affiliated with Ipsen (Sponsor). The survey was available via an online platform in 11 languages across 15 countries: Argentina, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Poland, Russia, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom (U.K.), and the United States (U.S.). The feasibility of conducting the survey in various territories was assessed, and countries were ultimately selected based on the presence of national FOP organizations and support networks to help with survey dissemination, as well as local regulations regarding acceptability of a central institutional review board (IRB) for review of the protocol.

Participants were recruited through the IFOPA and local/regional partner FOP organizations (Supplementary Table S1). People of any age with FOP, as well as their immediate family members (parents/legal guardians and siblings aged ≥18 years) were eligible to participate in the survey. Eligible participants were notified of the survey launch through e-mail, community newsletters, and personal outreach. All adult participants were required to provide informed consent, and informed assent was required for patients aged 13–17 years, alongside informed consent from a parent/legal guardian. For patients aged <13 years, a parent/legal guardian was required to provide consent and to complete the survey on the patient’s behalf as a proxy. Family members who acted as proxies and completed the survey on behalf of their relative with FOP could also participate themselves as family members. Patients were allowed assistance to physically enter responses if they were unable to complete the survey independently.

Participants were directed to appropriate questions for their age and their relationship to the individual with FOP (Supplementary Table S2). Additional questions were addressed to the family member identifying as the primary caregiver for the person with FOP. Participant demographics were collected and included gender, age, country of residence, highest level of schooling completed, and employment status. Information on whether an individual’s diagnosis of FOP had been confirmed by genotyping was also collected.

The survey was conducted in compliance with Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPP) Guidelines, the International Ethical Guidelines for Health-Related Research Involving Humans, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Guidance for Industry: Good Pharmacovigilance and Pharmacoepidemiologic Assessment, and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The survey was reviewed and approved centrally by the IRB of the University of Pennsylvania, FOP community advisors, and the Sponsor. Consistent with best-practice reporting of patient involvement in research, we report the patient involvement in this project using the standardized Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP2) checklist (Supplementary Table S1) [Citation24].

2.2. Physical functioning assessments

The impact of FOP on the physical functioning of patients was assessed using the Patient-Reported Mobility Assessment (PRMA) [Citation25,Citation26] and the FOP Physical Function Questionnaire (FOP-PFQ) [Citation27] (Supplementary Table S3).

The PRMA scores each of 12 joints and three body regions as 0 (not limited at all), 1 (moderately limited), or 2 (extremely limited [cannot move at all]); total scores range from 0–30, with higher scores representing more severe limitations in mobility. PRMA total scores were categorized into four levels: Level 1, total score 0–6; Level 2, total score 7–12; Level 3, total score 13–18; and Level 4, total score ≥19. These four levels were selected to balance the number of evaluable patients with meaningful differences in disease impact between PRMA levels. The categorization of the PRMA levels was validated by a clinical expert who treats patients with FOP.

The FOP-PFQ was used to assess the impact of FOP on ADLs and physical functioning. Total scores were transformed to reflect the percentage of worst possible score, with a score of 0% representing no loss of physical function, and 100% representing complete loss of physical function [Citation27].

2.3. Quality of life assessments

The impact of FOP on the QoL of patients and family members was assessed using the EuroQoL health-related QoL questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L) [Citation28,Citation29] and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS; adult and pediatric) Global Health Scale [Citation30] (Supplementary Table S3).

The EQ-5D-5L, completed by participants aged ≥13 years, is a patient-reported measure of health-related QoL. Using the U.S. algorithm, participants’ responses were converted into a single index score that represents QoL according to the preferences of the general population [Citation31]. Possible scores range from −0.573 to 1 (the latter represents full health).

The PROMIS (adult) Global Health Scale, used for all participants aged ≥15 years, and the PROMIS (pediatric) Global Health Scale, used for patients aged <15 years, assessed physical and mental function. All scores are reported as T-scores, with higher T-scores indicating better physical/mental health; T-score distributions are standardized such that 50 represents the mean for the general U.S. population.

The primary caregiver subpopulation completed the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) to assess the impact of caring for a family member with FOP on health and psychological wellbeing (Supplementary Table S3) [Citation32]. With total scores ranging from 0–88, the impact was considered to be little/absent for scores <21, mild to moderate for scores of 21–40, moderate to severe for scores of 41–60, and severe for scores of 61–88 [Citation33].

A tailored, FOP-specific questionnaire was developed with input from FOP community advisors to understand the social and emotional impact of FOP on family members. The questionnaire included a set of 28 questions related to stress, worries/concerns, and the impact on personal daily activities and relationships (Supplementary Table S3).

2.4. Economic assessments

Additional questions, tailored to individuals with FOP, their family members, and/or primary caregivers, were included in the survey to assess utilization of healthcare services, utilization of living adaptations (which refers to AADAs and medical therapies/doctors), out-of-pocket costs, and the impact of FOP on employment and ADLs, including travel. AADAs were grouped into four areas identified by the IFOPA and national FOP organizations as categories of AADAs utilized by people living with FOP: mobility/daily activities/pay for assistance, bedroom/bathroom/home, workplace/technology, and school/sport (Supplementary Table S3).

2.5. Statistical analysis

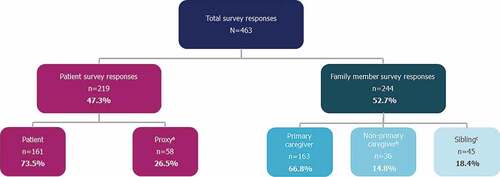

The primary analysis populations were the patient population and the family member population. The family member population was also analyzed by subpopulation: primary caregivers, non-primary caregivers (i.e. parents/legal guardians who did not identify as the primary caregiver), and siblings (). Continuous data were summarized using descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation [SD]). Categorical data were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Percentages were calculated based on the number of non-missing observations. Details on scoring for each assessment are provided in Supplementary Table S3. Analyses were performed for all patients, by PRMA level and by age group, as appropriate. Patients with FOP were categorized into the following age groups to align with prior work that used these categories to provide a representative cross-section of disease severity and/or progression: <8 years, 8–14 years, 15–24 years, and ≥25 years [Citation34]. Where possible, responses from family members were linked with the responses of the related person with FOP and analyses were performed based on the related patient’s age and PRMA level. Patient information was anonymized and remained protected during the linkage process.

Figure 1. Survey responses by study population.

Linear regression analyses were performed to understand the impact of decreasing joint mobility (PRMA total score) on the following: physical functioning/ADLs (FOP-PFQ score), health-related QoL (EQ-5D-5L index score), primary caregivers’ health and psychological wellbeing (ZBI total score), healthcare service and living adaptation utilization (number of living adaptations by AADA area and medical therapies/doctors), and out-of-pocket expenditure (U.S. participants only; sum of all expenses declared). Regression slope was used to assess the significance of linear relationships. Linear regression analyses (with the exception of out-of-pocket expenditure) were adjusted for geographic region using the following country groups: North America (Canada, U.S.), Latin America (Argentina, Brazil, Mexico), Europe (France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, Sweden, U.K.), and Rest of the World (Japan, Russia, South Korea).

3. Results

3.1. Participant demographics

The survey was available online and accessible via computer and mobile phone between 18 January 2021 and 30 April 2021. There were 463 total responses to the survey, including 219 responses to the patient survey and 244 responses to the family member survey (). There were no deviations from the protocol and no participants were excluded from the patient or family member populations. Participant demographics can be found in . The majority of patients had a diagnosis of FOP confirmed by genotyping (87.2%). Mean (SD) age of patients was 24.2 (14.3) years. Approximately half of patients were ≥25 years of age (49.3%), with the remainder distributed across the other age groups as follows: <8 years, 14.2%; 8–14 years, 18.3%; 15–24 years, 18.3%. Mean (SD) age of primary caregivers was 49.2 (12.0) and 85.4% of primary caregivers identified as female. Patient demographics by age group can be found in Supplementary Table S4.

Table 1. Burden of illness survey participant demographics.

3.2. Physical impact of FOP on patients

3.2.1. PRMA and FOP-PFQ (patients ≥2 years)

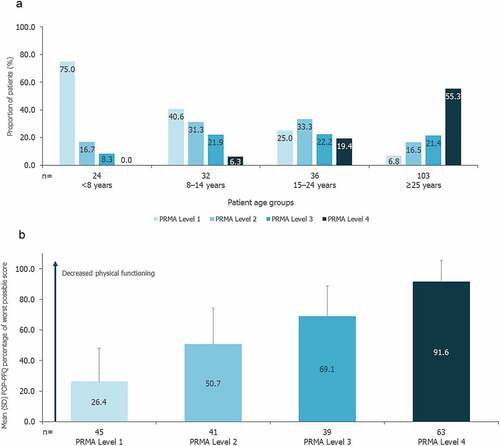

Approximately one-third of patients had a PRMA total score in Level 4 (33.8%), with a relatively even distribution of patients across PRMA Levels 1–3. There was a clear trend for worsening mobility and joint function with age; 55.3% of patients aged ≥25 years had PRMA total scores in Level 4, compared with no patients aged <8 years (), and mean (SD) FOP-PFQ score increased from 29.6 (25.1) for patients aged <8 years (n = 25) to 76.1 (26.7) for patients aged ≥25 years (n = 104; Supplementary Figure S1). Mean (SD) FOP-PFQ score was also highest for patients with PRMA total scores in Level 4 (91.6 [14.0]; n = 63) and lowest for patients with PRMA total scores in Level 1 (26.4 [21.7]; n = 45; ). Linear regression analysis identified a statistically significant positive relationship between limitations in joint mobility and ability to conduct ADLs, such that for every one-unit increase in PRMA total score, there was a mean (standard error [SE]) increase (i.e. worsening) of 3.258 (0.160) in FOP-PFQ score (p < 0.0001).

Figure 2. a) Joint mobility by patient age group b) Impact of joint mobility on patients’ physical functioning.

3.3. Quality of life impact of FOP on patients and family members

3.3.1. EQ-5D-5L (patients ≥13 years and family members)

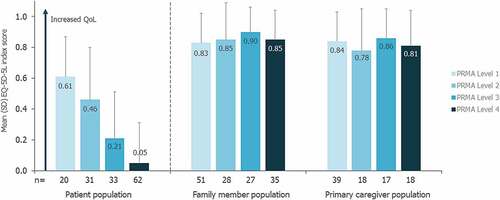

Mean (SD) EQ-5D-5L index score for patients (≥13 years; n = 152) was 0.24 (0.36). Patients with greater restrictions in joint mobility had worse QoL, with mean (SD) EQ-5D-5L index score decreasing from 0.61 (0.26; n = 20) for patients with PRMA total scores in Level 1 to 0.05 (0.26; n = 62) for those in Level 4 (). Linear regression analysis demonstrated a significant negative association between limitations in joint mobility and the QoL of patients, such that for every one-unit increase in PRMA total score, there was a mean (SE) decrease (i.e. worsening) of 0.029 (0.003) in the EQ-5D-5L index score (p < 0.0001).

Figure 3. Impact of joint mobility on QoL for patients, family members, and primary caregivers.

For the family member population, the mean (SD) EQ-5D-5L index score was 0.85 (0.21; n = 238); the primary caregiver subpopulation had a similar mean (SD) score of 0.83 (0.22; n = 158). The mean EQ-5D-5L index score for family members and the primary caregiver subpopulation did not appear to vary by the PRMA level or age of the related patient with FOP (, Supplementary Figure S2). For family members and primary caregivers, the relationship between EQ-5D-5L index score and the related patient’s PRMA total score was not statistically significant (linear regression analyses: p = 0.674 and p = 0.297, respectively).

3.3.2. PROMIS (patients ≥5 years and family members)

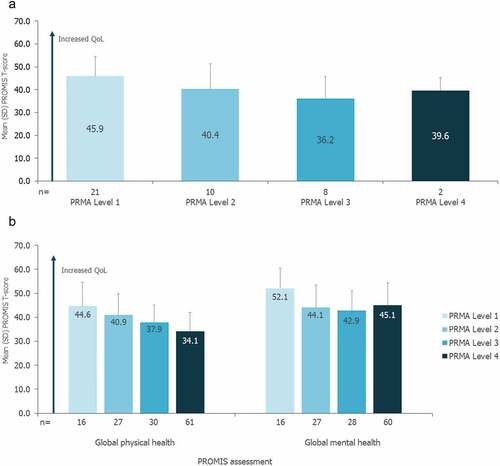

Mean (SD) PROMIS (pediatric) global total T-score for patients aged 5–14 years was 42.3 (9.9; n = 50). For these patients, QoL as assessed by PROMIS global T-score tended to decrease with greater mobility restrictions (). Mean (SD) PROMIS global physical and mental health T-scores for patients (≥15 years) were 37.6 (9.0; n = 140) and 44.9 (9.5; n = 137), respectively. For these patients, QoL as assessed by PROMIS global physical health T-score also tended to decrease with greater mobility restrictions; mean global mental health T-scores were highest for patients with the least mobility restrictions (PRMA Level 1), and lower and similar across the remaining PRMA levels (). When analyzed by age, older patients had lower QoL as assessed by PROMIS (Supplementary Table S5). All family members, primary caregivers, non-primary caregivers, and siblings had mean global physical and mental health T-scores close to 50, which represents the mean of the general U.S. population (Supplementary Figure S3). For family members, mean global physical and mental health T-scores were similar across all PRMA levels of the related patient with FOP (Supplementary Figure S4).

Figure 4. a) Impact of joint mobility on QoL for patients 5–14 years of age b) Impact of joint mobility on QoL for patients ≥15 years of age.

3.3.3. Zarit Burden Interview (primary caregivers)

Close to half (45.1%) of primary caregivers (n = 153) reported a ZBI total score between 21 and 40, indicating a mild to moderate impact on their health and/or psychological wellbeing (Supplementary Table S6). A score <21, indicating little to no impact, was reported by 39.9% of primary caregivers (Supplementary Table S6). The majority of primary caregivers caring for the youngest group of patients (<8 years) reported a mild to moderate impact (56.7%; n = 30), while the majority of primary caregivers caring for the oldest group of patients (≥25 years) reported little or no impact (57.7%; n = 26; Supplementary Table S6). The impact on primary caregivers did not vary by the PRMA level of the patient being cared for (Supplementary Table S6). The relationship between PRMA total score and ZBI total score was not significant (linear regression analysis: p = 0.169).

3.3.4. Emotional impact questionnaire (family members)

Learning of their relative’s FOP diagnosis was very/extremely difficult for 79.2% of family members, and 85.4% of family members reported that the occurrence of flare-ups in their relative with FOP was very/extremely stressful (Supplementary Table S7). The majority of family members were often/always worried that their relative with FOP may hurt themselves (67.7%) and found the challenges of FOP very/extremely stressful (57.5%; Supplementary Table S7). Socially, however, most family members thought that caring for a relative with FOP had no/little negative impact in terms of social interaction (73.4%), making friends (83.5%), joining clubs (74.7%), attending family or social events (70.8%), dating (82.9%), or pursuing an interest (71.7%; Supplementary Table S7). The most common ADLs for which family members reported ‘always’ assisting the related person with FOP were preparing/cooking meals (49.1%), bathing/showering (48.1%), dressing (44.2%), shopping (41.2%), and leaving the house (38.7%). Family members spent eight hours per day (mean) helping to provide care or assistance to their relative with FOP (Supplementary Table S7). The median number of hours per day family members spent providing care or assistance to their relative with FOP with a PRMA total score in Level 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, was 6.0, 6.5, 3.0, and 2.0.

3.4. Economic impact of FOP on patients and family members

3.4.1. Healthcare service utilization and living adaptations (all patients)

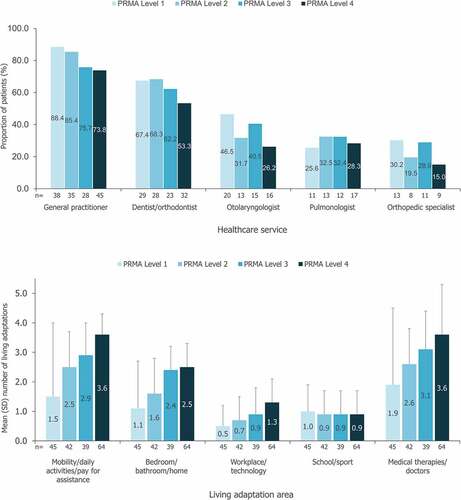

The healthcare services most commonly consulted by patients with FOP in the 12 months prior to survey completion were general practitioners (GP; 78.3%) and dentists/orthodontists (59.5%), with healthcare service utilization varying by the patient’s PRMA level (). AADA use also varied by PRMA level and was generally higher for patients with greater mobility restrictions (). Linear regression analyses identified significant positive associations between the number of living adaptations used in the 12 months prior to survey completion and the patient’s PRMA total score; for AADAs, this significant positive relationship was identified for all areas (p < 0.0001) apart from school/sport (p = 0.826). For medical therapies/doctors, a significant relationship was also identified (p < 0.0001).

Figure 5. a) Most commonly utilized health services within the past 12 months b) Utilization of aids, assistive devices and adaptations and medical therapies/doctors.

3.4.2. Ability to travel (patients ≥18 years)

For patients aged ≥18 years (n = 142), loss of joint mobility substantially limited ability to travel, with 50.0% of patients with PRMA total scores in Level 4 unable to travel by plane, 34.4% unable to travel by car, and financial costs limiting or preventing travel entirely for 59.0% of patients with the most severe mobility limitations (Supplementary Table S8). Overall, financial costs limited or prevented nearly half (47.7%) of patients with FOP from traveling (Supplementary Table S8).

3.4.3. Employment (patients ≥18 years and family members)

When asked whether FOP had impacted career decisions, 82.8% of patients aged ≥18 years (n = 142) reported ‘yes.’ This impact was substantial for those with severe mobility restrictions, with 85.2% of patients with PRMA total scores in Level 4 reporting that FOP impacted career decision-making. Over one-third of family members (38.9%) and over half of primary caregivers (51.3%) reported needing to adapt their career to look after their relative with FOP. The proportion of family members who felt that having a relative with FOP had impacted their career was greatest for those caring for patients with PRMA total scores in Level 1 (40.0%) or Level 4 (39.4%). Primary caregivers reported missing a mean (SD) of 30.6 (87.8) days of work in the 12 months prior to completing the survey due to caring for a family member with PRMA total scores in Level 1. Mean (SD) number of work days missed was similar if the related patient had PRMA total scores in Level 3 (35.4 [91.4]) and lower for Level 2 (7.1 [13.0]) and Level 4 (3.1 [6.2]).

3.4.4. Cost of care (out-of-pocket expenditure; all patients)

The median cost of care (out-of-pocket) by country is shown in Supplementary Figure S5. In all countries, the vast majority of patients (>83%) reported at least one expense across the five living adaptation areas (AADAs and medical therapies/doctors) in the 12 months prior to completing the survey. The most common cost of care area in the majority of countries was medical therapies/doctors (>77% of patients), with the exception of Mexico, Poland, South Korea, and the U.S., where mobility/daily activities/pay for assistance was the most common area (>92% of patients). For patients from the U.S., mean cost of care (U.S. dollars) in the 12 months prior to survey completion was higher for those with PRMA total scores in Levels 3 and 4 compared with those with PRMA total scores in Levels 1 and 2 (Supplementary Figure S6). Linear regression analysis of data from U.S. patients did not show a significant positive relationship between PRMA total score and out-of-pocket expenditure (U.S. dollars) in the 12 months prior to completing the survey (p = 0.0542). Living adaptations related to mobility, daily activities, and/or pay for assistance constituted the greatest overall costs for U.S. patients compared with the other four categories of living adaptations assessed (Supplementary Table S9). In addition, patients spent more money on living adaptations related to mobility, daily activities, and/or pay for assistance with each increasing PRMA level (Supplementary Figure S7); however, the same trend was not observed for the other four categories of living adaptations assessed (Supplementary Table S9).

4. Discussion

Substantial progress has been made in recent years to advance understanding of the clinical characteristics and disease mechanism of FOP. Published case series [Citation8,Citation35], large patient surveys [Citation10,Citation14], and prospective natural history studies have provided valuable insights into the clinical profile and progression of FOP [Citation34,Citation36]. However, information on the physical, QoL, social, and economic impact of FOP has been lacking. This study provides a significant contribution to the literature, collecting detailed information on the impact of FOP on people with the disorder and their family members.

4.1. Physical impact

The progressive and irreversible nature of HO contributes to the cumulative disability experienced by people with FOP [Citation2,Citation11]. The survey responses demonstrate that reduced joint mobility (assessed by PRMA) is significantly associated with decreased physical functioning and ability to conduct ADLs (assessed by FOP-PFQ). For patients with the most severe mobility limitations, mean FOP-PFQ score was near 100%, which represents the most severe limitations in physical function. These findings support results from a natural history study of FOP, which reported a strong correlation between FOP-PFQ score and Cumulative Analogue Joint Involvement Scale (CAJIS) total score (r = 0.71), the physician-reported instrument on which the PRMA (a patient-reported instrument) is based [Citation34].

Individuals aged <8 years reported the least severe restrictions in joint mobility and physical functioning and individuals aged ≥25 years experienced the greatest restrictions; this finding confirms that mobility and physical functioning worsen over the lifetime of an individual with FOP, largely due to the progressive and irreversible nature of HO. A similar finding was identified in a natural history study of FOP, in which physical functioning also significantly decreased with increasing age; the youngest group of patients (<8 years) had the lowest mean FOP-PFQ score at baseline, compared with the oldest group of patients (25–65 years) who had the highest [Citation34]. Data from the FOP Registry have also shown that younger patients have greater physical functioning, with lower FOP-PFQ scores seen for patients aged 0–8 years and 9–15 years compared with patients aged >15 years [Citation14].

4.2. Quality of life impact

The results of this survey support the findings of previous studies that demonstrated that the progressive development of HO, and the increasingly limited mobility and physical functioning for people with FOP, has a severe, negative impact on QoL [Citation37]. For individuals with the most severe physical limitations (PRMA Level 4), the mean EQ-5D-5L score was 0.05, which is close to the equivalent of mortality. A systematic review found that mean EQ-5D-5L scores reported by people living with diabetes mellitus, cancer, multiple sclerosis, and cardiovascular disease range from 0.31–0.99, 0.62–0.90, 0.31–0.78, and 0.56–0.85, respectively [Citation38], while a study on chronic low back pain reported a median (range) EQ-5D-5L score of 0.62 (−0.07–0.91) [Citation39]. These mean and median EQ-5D-5L scores are all notably higher than that for FOP, demonstrating the severe impact of FOP on patients’ QoL. A similar trend was also identified for the PROMIS Global Health Scale, with T-scores decreasing (i.e. lower QoL) for patients with greater mobility restrictions.

For family members and primary caregivers, the impact of the related patient’s joint mobility on QoL was less clear. The mean health-related QoL (as assessed by the EQ-5D-5L) of primary caregivers (mean age 49.2 years) was found to be similar to that of the mean for individuals aged 45–54 years in the U.S. population (0.83 versus 0.82, respectively) [Citation40]. Furthermore, the related patient’s joint function was not a significant predictor of the health and/or psychological wellbeing of primary caregivers (as assessed by the ZBI). In this survey, the majority of primary caregivers identified as female (85.4%), which aligns with previous research demonstrating that women most often assume the role of primary caregiver for people with rare diseases [Citation41]. Interestingly, while nearly 40% of primary caregivers caring for patients with the most severe mobility limitations reported needing to adapt their careers, the majority of those caring for the oldest group of patients (most of whom had the most severe mobility limitations) reported little or no impact on their health and/or psychological wellbeing. Further research into the longitudinal impact of providing care for people with FOP is needed. A possible explanation for these findings may be that the ZBI assessment captures the ‘current’ wellbeing of the individual. Therefore, the results from the ZBI may, in part, be reflective of resilience and the ability to recover and adapt from challenging experiences, as family members and primary caregivers learn from experience and grow their support network within the FOP community. Alternatively, these findings may reflect resignation felt by primary caregivers over time regarding the inevitability of disease progression. An additional factor may be that people with FOP aged ≥25 years often have paid caregivers and/or personal aids, which may decrease stress on family members providing care.

The FOP-specific emotional impact questionnaire found that the majority of family members were often/always worried that their child/sibling with FOP may hurt themselves. For a person with FOP, minor trauma, such as a fall, can lead to a flare-up and result in HO and disease progression [Citation13]. Therefore, it is unsurprising that over two-thirds of family members cited this as a constant worry. The questionnaire also identified that over half of family members found the challenges of FOP very/extremely stressful. Overall, questions relating to the acute phases of living with a family member with FOP (e.g. first diagnosis, flare-ups) revealed a large emotional impact on family members. The majority of family members indicated little to no negative social impact, which may reflect that, when not experiencing the acute phases of FOP disease progression, the impact on family members is reduced.

4.3. Economic impact

In addition to the physical, QoL, and social impact of FOP, the survey investigated the financial impact of FOP on patients and their family members. The results indicate that, overall, patients with more severe functional limitations use a greater number of living adaptations. These results support the findings from the FOP Registry, where a modified CAJIS score was positively correlated with the total score for use of AADAs (i.e. more restricted movement led to greater AADA use; Pearson’s coefficient: 0.56) [Citation14]. However, people with FOP in certain regions of the world may have greater difficulty accessing and affording living adaptations; therefore, their needs may not be accurately reflected through an assessment of the number of living adaptations they use. The results also indicate that for patients from the U.S., living adaptations related to mobility, daily activities, and/or pay for assistance are responsible for the greatest overall costs compared with the other four categories of living adaptations assessed. In addition, the costs associated with this category of living adaptations are greater with each increasing PRMA level, suggesting a greater financial impact for patients with more severe mobility loss. However, the same trend was not observed for the other four categories of living adaptations assessed; small sample sizes for subpopulations of country-level data may be a limiting factor in identifying which types of living adaptations result in the greatest costs for patients with the least and most severe mobility loss.

For participants from the U.S., mean cost of care in the 12 months prior to survey completion was higher for patients with PRMA total scores in Levels 3 and 4 compared with patients with PRMA total scores in Levels 1 and 2. Additionally, while costs appear to plateau for patients with PRMA total scores in Levels 3 and 4, at a mean of approximately 22,000 U.S. dollars, the range of costs becomes progressively wider with each PRMA level; patients with PRMA total scores in Level 4 reported an upper range of approximately 164,000 U.S. dollars for costs related to FOP. These findings suggest that as mobility loss increases, patients and their family members are subject to a greater financial burden. Higher costs for patients with more severe mobility loss may be attributable to a greater number of living adaptations used and/or the use of more complex and expensive living adaptations. As healthcare systems, insurance, and costs vary by region, these are important considerations to be explored further; research to determine healthcare resource utilization and costs from the payer perspective is ongoing.

This survey found that healthcare utilization by people with FOP appears to be similar to that of the general U.S. adult population; 78.3% of individuals with FOP indicated that they had visited a GP within the 12 months prior to survey completion, compared to 83.4% of adults in the U.S. in 2020 [Citation42]. Findings are similar for visits to a dentist/orthodontist, with 59.5% of individuals with FOP reporting having a dental exam or cleaning in the last 12 months, compared to 63.0% of U.S. adults in 2020 [Citation43]. However, while overall healthcare resource use appears to be comparable, FOP Registry data show that the proportional decrease in patient visits to GPs and dentists/orthodontists from 2019 to 2020, with the onset of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, was greater for people with FOP than for the general U.S. adult population [Citation42–44]. This may reflect the ‘shielding’, or the minimization of face-to-face contact with others due to being at high risk of serious illness, and the lack of access to healthcare services that people with FOP experienced during the global pandemic; as COVID-19 vaccinations are administered intramuscularly, which may trigger a flare-up and new bone growth, many people with FOP remain unvaccinated and highly vulnerable, and may have delayed seeking medical care during this period of time.

The results of this survey highlight that people with FOP with the most severe mobility restrictions may have different needs to people with FOP at earlier stages of disease progression. As disability increases over time, priorities in the management of FOP shift, with a large focus on daily care and support, and an increased reliance on assistance from family members with performing daily activities. Limitations in mobility also greatly restrict an individual’s ability to travel, as identified in this survey, with approximately one-third of patients with the most severe mobility restrictions unable to travel by car and approximately half unable to travel by airplane, train, or bus. In addition, the ability to fulfill basic needs outside of the home, such as eating or using the bathroom, becomes increasingly challenging with limited mobility and may restrict opportunities to travel, particularly to places with poor accessibility for people with disabilities. Evolving care priorities and difficulty traveling may contextualize our finding that people with FOP with the most severe mobility limitations used healthcare services less frequently than those individuals with greater joint mobility. Patients with the most severe mobility restrictions may rely on telehealth services, with in-person healthcare services only utilized when there is an urgent need. These findings underscore the need to further understand how severe mobility impairment may negatively impact patients’ ability to seek care, and if this may vary by geographical region.

The impact of FOP on employment may be similar to that of other chronic, progressive diseases. A study of patients with multiple sclerosis found that the proportion of patients who had to modify their employment status increased as the disease progressed, from 37% with mild disease to 82% with severe disease [Citation45]. Furthermore, both individual and household income declined with multiple sclerosis progression, and lost productivity was a major indirect cost to society [Citation45]. In this survey, family members indicated that their career decisions were most significantly impacted when the related person with FOP had either the least or most severe mobility restrictions. Although the impact of FOP on career decisions may be expected for those family members caring for an individual with severe mobility restrictions, this finding reflects that the patients who have the least severe joint restrictions are often in the early years of FOP, which can be a highly active period for the family in terms of seeking expert medical advice, therapies, and information. For families, a major focus during this period is the prevention of disease progression.

Furthermore, primary caregivers of people with FOP reported missing approximately one month of work in the 12 months prior to completing the survey due to caring for a family member in either the lowest (PRMA Level 1) or second highest (PRMA Level 3) category of joint mobility restrictions. In contrast, primary caregivers of patients with the most restricted mobility (PRMA Level 4) reported, on average, less than five missed days of work in the prior 12 months. This result appears to contradict the above finding of a significant impact on career decisions for those with a family member with the most restricted mobility. However, it is possible that the assessment of missed work days only highlights an individual’s ‘current’ circumstances, whereas the reported impact on career decisions reflects if this has ever been the case for that individual. For example, more than three-quarters of patients with the most restricted mobility are aged ≥25 years. Therefore, most primary caregivers for these patients may be of retirement age and as such may have previously had their career impacted by FOP, but will not currently report any work days missed in the survey. An additional consideration is that the survey overlapped with the COVID-19 pandemic, which substantially impacted employment and working patterns, and this may have influenced responses [Citation46,Citation47]. Public or private programs to assist families in paying for full- or part-time caregiving services may be beneficial, and future research into the financial impact of such programs would be valuable. A recent study on the total economic burden of rare diseases in the U.S. found that indirect costs due to productivity loss of the person with the rare disease and their caregivers constituted a substantial proportion of the overall economic costs of rare diseases, around 44% [Citation48]. Although to date information regarding the economic cost of specific rare diseases has been limited, the results presented here demonstrate that FOP has a substantial impact on career decisions and missed workdays for caregivers, and further insight into the economic consequences of these impacts on families is needed. Overall, the findings from this survey highlight how the needs and priorities for people with FOP and their family members may change during different phases of disease progression, and can provide insight into the resources and support that individuals and their family members may require at various points in time.

4.4. Strengths and limitations

This survey received responses from a total of 219 patients and 244 family members from 15 countries. Age and gender demographics of patient participants were similar to those in the FOP Registry, in which more than one-third of all known individuals with FOP are enrolled (based on approximately 900 known individuals with FOP) [Citation14,Citation44]. Although this suggests that the survey’s patient population was generally representative of the international FOP community, it is important to note that the survey was not available in every country and the results may not be representative of the experiences of all individuals, particularly those from underserved communities, where unmet needs may be greater. Importantly, the survey was only available online, and therefore may not have been accessible to those in the FOP community with limited access to the internet.

Family member participants were asked whether they identified as the primary caregiver for the related individual with FOP, and these participants were directed to additional questions to assess the impact on the primary caregiver subpopulation. However, in many households, caregiving responsibilities may be shared, and requesting that one family member identify themselves as the primary caregiver may have been restrictive for some survey participants. Furthermore, the 12-month recall period for many of the questionnaires included in the survey may have been limiting, as people with FOP can experience periods of time with no acute symptoms and/or HO accumulation. Additionally, families may have previously invested in living adaptations, and spent money modifying home environments and purchasing aids and assistive devices in prior years. Therefore, responses may not have accurately captured a person’s overall life experience and the complete financial impact of FOP. The 12-month recall period also coincided with the global COVID-19 pandemic and, therefore, healthcare utilization and out-of-pocket expenditure reported here may differ from pre-pandemic patterns. For example, recent data from the FOP Registry showed that the percentage of patients who visited their doctor was lower in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic (75%) than in 2019 (83%), and this was also the case for the percentage of patients who visited their dentist (43% in 2020 compared with 63% in 2019) [Citation44]. Families may have also delayed major home adaptations during the pandemic, and this may have affected results. Additionally, for some participants, past events may have been difficult to recall, which may have impacted survey responses. Further research would be beneficial to understand the use of specific living adaptations and associated costs over a longer period of time for individuals with FOP and their family members.

A potential limitation is the description of the study in recruitment materials as a burden of illness survey; it is possible that the use of the term ‘burden’ may have influenced survey responses if participants had concerns that their family member with FOP would see their responses and feel like a ‘burden’. A limitation of the survey design is that some assessments were not disease-specific, including the EQ-5D-5L, PROMIS, and ZBI, and therefore may not fully capture the nuances of the experiences of people living with FOP and their family members. However, the non-FOP-specific questionnaires were useful tools to compare the experiences of the FOP community with those of the general public and other communities of people living with chronic diseases. It is worth noting that the 5L version of the EQ-5D was selected over the 3L version because the expanded number of levels allows for a more sensitive and precise assessment of the health-related QoL of participants [Citation49], and because of recommendations for the use of 5L version from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [Citation50]. The use of the U.S. algorithm, rather than country-specific algorithms, to convert participants’ responses to all questions on the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire into a single index score may also be viewed as a limitation of this study, as preferences for health may differ between countries. However, this was done to maintain uniformity and reduce bias in the regression analyses, and country-specific algorithms were not available for all countries (algorithms were only available for Canada, Germany, Japan, and the U.S.). The U.S. algorithm was used for all countries as it is the most represented country in the survey. Finally, small sample sizes for country-level data generally inhibited subgroup analyses that would have allowed for interpretation of survey responses in the context of cultural differences and variations in local healthcare practices. Future post-hoc analyses using country-level data with responses grouped by the participants’ broader geographic region may provide important insights. Where subgroup analyses were conducted using data with uneven distributions of a low number of participants (e.g. country-level cost of care data), the results should be interpreted cautiously.

Despite these limitations, this survey was the first to collect valuable data on the multifaceted impact of FOP on patients and their family members. Although as a cross-sectional survey the information collected represents a specific point in time, the findings presented here provide a baseline and this survey was an important opportunity to capture these data before any approved disease-modifying treatments are available to patients with FOP. These data will facilitate future research that will contribute to understanding the impact of FOP on individuals and their family members over time. In addition, the availability of the survey in 15 countries and 11 languages provides an international perspective of the impact of FOP on patients and their family members. An additional strength was the co-creation of the survey with FOP community advisors; their input allowed for the inclusion of assessments and tailored questionnaires that would be most relevant to the FOP community and facilitated the international dissemination of the survey. Continued collaboration with FOP community advisors is key to ensure that the results of the survey are interpreted appropriately and shared using accessible language.

5. Conclusion

This survey demonstrated that progressive loss of joint mobility and function, and decreased ability to carry out daily activities, is associated with a considerable, negative QoL impact for people with FOP and a mild to moderate impact on primary caregivers’ health and/or psychological wellbeing, particularly for those looking after younger children with FOP. In addition, loss of joint function creates a substantial need for living adaptations for people with FOP, and results in changes to career plans and missed days of work for these individuals and their family members. This finding suggests a negative financial impact due to rising household expenses and a negative economic impact on society due to lost productivity of these individuals and their family members as FOP progresses. This survey was not available in every country and, therefore, additional research into the impact of FOP on people living in underserved FOP communities is needed. Overall, this study provides valuable information that can be used to refine resources and support for disease management, to optimize care, and to provide guidance for the development of new healthcare interventions for people with FOP and their family members.

Declaration of interest

M Al Mukaddam: Research investigator: Clementia/Ipsen, Regeneron; Non-paid consultant: BioCryst, Blueprint Medicines, Daiichi Sankyo, Incyte, Keros; Advisory board (all voluntary): IFOPA Registry Medical Advisory Board, Incyte, International Clinical Council on FOP; non-restricted educational fund from Excel and Catalyst sponsored by Ipsen; KS Toder: Research funding from Clementia/Ipsen and Regeneron; M Davis: Member of the Rare Bone Disease Alliance Steering Committee, the Rare Bone Disease Summit Steering Committee, and the Global Genes RARE Global Advocacy Leadership Council; A Cali: Trustee of The Radiant Hope Foundation, Trustee of the Ian Cali FOP Research Fund/Penn Medicine, Co-founder and Advisory Board member Tin Soldiers Patient Identification Program, Executive Producer Tin Soldiers documentary, Past IFOPA Chairman of the Board, Executive Associate of the International Clinical Council on FOP (all voluntary); M Liljesthröm: Co-Founder and President of Fundación FOP, Argentine IPC Representative, IFOPA Research Committee member, past IFOPA Board member (all voluntary); S Hollywood: Committee member on the IFOPA LIFE Award Program, Committee member on the IFOPA Fundraising Committee; K Croskery, EA Böing: Employees and shareholders of Ipsen; A-S Grandoulier: Employee of Atlanstat, contractor for Ipsen; JD Whalen: Employee of Ipsen at the time of the study; FS Kaplan: Research investigator: Clementia/Ipsen, Regeneron; Advisory Board: IFOPA Registry Medical Advisory Board; Founder and Past-President of the International Clinical Council on FOP. In April 2019, Ipsen acquired Clementia Pharmaceuticals. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

Substantial contributions to study conception/design, or acquisition/analysis/interpretation of data: M Al Mukaddam, KS Toder, M Davis, A Cali, M Liljesthröm, S Hollywood, K Croskery, EA Böing, A-S Grandoulier, JD Whalen, FS Kaplan; drafting of the publication, or revising it critically for important intellectual content: M Al Mukaddam, KS Toder, M Davis, A Cali, M Liljesthröm, S Hollywood, K Croskery, EA Böing, A-S Grandoulier, JD Whalen, FS Kaplan; final approval of the publication: M Al Mukaddam, KS Toder, M Davis, A Cali, M Liljesthröm, S Hollywood, K Croskery, EA Böing, A-S Grandoulier, JD Whalen, FS Kaplan. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors agree for the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Medical writing

The authors thank Ellie Zachariades, MSc, and Marielle Brown, PhD, of Costello Medical, UK for providing medical writing support, which was sponsored by Ipsen in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines.

Data sharing statement

Qualified researchers may request access to patient-level study data that underlie the results reported in this publication. Additional relevant study documents, including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, annotated case report form, statistical analysis plan and dataset specifications may also be made available. Patient level data will be anonymized, and study documents will be redacted to protect the privacy of study participants. Where applicable, data from eligible studies are available 6 months after the studied medicine and indication have been approved in the US and EU or after the primary manuscript describing the results has been accepted for publication, whichever is later. Further details on Ipsen's sharing criteria, eligible studies and process for sharing are available here (https://vivli.org/members/ourmembers/). Any requests should be submitted to www.vivli.org for assessment by an independent scientific review board.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (3.2 MB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants involved in the study and the FOP study team which includes Michelle Davis, Executive Director of the IFOPA, Adam Sherman, former Research Director of the IFOPA, and the following FOP community advisors, who all contributed to the design of this study: Christopher Bedford-Gay, U.K.; Anna Belyaeva, Russia; Amanda Cali, U.S.; Julie Collins, Australia; Suzanne Hollywood, U.S.; Antoine Lagoutte, France; Moira Liljesthröm, Argentina; Karen Munro, Canada; Nancy Sando, U.S. The authors also thank the following national FOP organizations: Fundación FOP (Argentina), FOP Brasil (Brazil), Canadian FOP Network, FOP France, FOP Germany, FOP Italia Onlus (Italy), J-FOP (Japan), FOP Mexico, FOP Polska (Poland), FOP Russia, Korean FOP Overcome Family (KFOPOF; South Korea [Republic of Korea]); Asociación Española de Fibrodisplasia Osificante Progresiva (AEFOP; Spain), Svenska FOP-föreningen (Sweden; members from Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland), and FOP Friends (U.K.). We thank Marin Wallace, Canada and Roger zum Felde, Germany for their contributions to this project prior to their passing.

The survey was carried out by Engage Health (Eagan, Minnesota, United States). Translation of the survey was managed by the specialist vendor TransPerfect Life Sciences and validated by local affiliates of the Sponsor.

Results of this survey have been presented in part at the following meetings: International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) EU, Virtual, November 30–3 December 2021; ISPOR, Washington, D.C., U.S., May 15–18, 2022; Endocrine Society (ENDO), Atlanta, GA, U.S., June 11–14, 2022; European Conference on Rare Diseases (ECRD), Virtual, June 27–1 July 2022; International Conference on Children’s Bone Health (ICCBH), Dublin, Ireland, July 2–5, 2022; World Orphan Drug Congress (WODC), Boston, MA, U.S., July 11–13, 2022; International Skeletal Dysplasia Society (ISDS), Santiago, Chile, August 24–27, 2022.

Trial registration number: NCT04665323.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2022.2115360

Additional information

Funding

References

- Online mendelian inheritance in man. #135100 fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva; FOP. Updated 2017. [cited 2022 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.omim.org/entry/135100

- Kaplan FS, Tabas JA, Gannon FH, et al. The histopathology of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. An endochondral process. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(2):220–230.

- Kaplan FS, Xu M, Seemann P, et al. Classic and atypical fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) phenotypes are caused by mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) type I receptor ACVR1. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(3):379–390.

- Liljesthröm M, Pignolo R, Kaplan F. Epidemiology of the global fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) community. J Rare Dis Res Treat. 2020;5(2):31–36.

- Baujat G, Choquet R, Bouée S, et al. Prevalence of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) in France: an estimate based on a record linkage of two national databases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):123.

- Pignolo RJ, Hsiao EC, Baujat G, et al. Prevalence of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) in the United States: estimate from three treatment centers and a patient organization. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16(1):350.

- Shore EM, Xu M, Feldman GJ, et al. A recurrent mutation in the BMP type I receptor ACVR1 causes inherited and sporadic fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Nat Genet. 2006;38(5):525–527.

- Zhang W, Zhang K, Song L, et al. The phenotype and genotype of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva in China: a report of 72 cases. Bone. 2013;57(2):386–391.

- Pignolo RJ, Shore EM, Kaplan FS. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: diagnosis, management, and therapeutic horizons. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2013;2(2):437–448.

- Pignolo RJ, Bedford-Gay C, Liljesthröm M, et al. The natural history of flare-ups in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP): a comprehensive global assessment. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31(3):650–656.

- Connor JM, Evans DA. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. The clinical features and natural history of 34 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982;64(1):76–83.

- Kaplan FS, Zasloff MA, Kitterman JA, et al. Early mortality and cardiorespiratory failure in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(3):686–691.

- Kaplan FS, Al Mukaddam M, Baujat G, et al. The medical management of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: current treatment considerations. Proc Int Clin Counc FOP. 2021;2:1–127.

- Pignolo RJ, Cheung K, Kile S, et al. Self-reported baseline phenotypes from the international Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva (FOP) association global registry. Bone. 2020;134:115274.

- Levy CE, Lash AT, Janoff HB, et al. Conductive hearing loss in individuals with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Am J Audiol. 1999;8(1):29–33.

- Peng K, Cheung K, Lee A, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of pain, flare-up, and emotional health in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: analyses of the International FOP Registry. JBMR Plus. 2019;3(8):e10181.

- IFOPA. FOP Registry [cited 2022 Jun 1]. Available from: https://fopregistry.org/

- Pignolo RJ, Baujat G, Brown MA, et al. Greater heterotopic ossification burden is associated with reduced mobility, function, and quality of life in individuals with FOP. J Bone Miner Res. 2021;37(Suppl 1):71.

- Office of the Surgeon General. Bone health and osteoporosis: a report of the surgeon general. Rockville (MD): Office of the Surgeon General (US); 2004.

- Kodra Y, Cavazza M, de Santis M, et al. Social economic costs, health-related quality of life and disability in patients with cri du chat syndrome. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5951.

- Landfeldt E, Lindgren P, Bell CF, et al. The burden of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: an international, cross-sectional study. Neurology. 2014;83(6):529–536.

- Slade A, Isa F, Kyte D, et al. Patient reported outcome measures in rare diseases: a narrative review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13(1):61.

- Ernstsson O, Janssen MF, Heintz E. Collection and use of EQ-5D for follow-up, decision-making, and quality improvement in health care - the case of the Swedish national quality registries. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2020;4(1):78.

- Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ. 2017;358:j3453.

- Kaplan FS, Al Mukaddam M, Pignolo RJ. A cumulative analogue joint involvement scale (CAJIS) for fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP). Bone. 2017;101:123–128.

- Kaplan FS, Al Mukaddam M, Pignolo RJ. Longitudinal patient-reported mobility assessment in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP). Bone. 2018;109:158–161.

- Pignolo RJ, Kimel M, Whalen J, et al. Validity and reliability of the fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva physical function questionnaire (FOP-PFQ), a patient-reported, disease-specific measure. J Bone Miner Res. 2020;35:312.

- EQ-5D Instruments. [cited 2022 Jun 1]. Available from: www.euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments

- Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, et al. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(7):1717–1727.

- Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, et al. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(7):873–880.

- Pickard AS, Law EH, Jiang R, et al. United States valuation of EQ-5D-5L health states using an international protocol. Value Health. 2019;22(8):931–941.

- Hébert R, Bravo G, Préville M. Reliability, validity and reference values of the Zarit Burden Interview for assessing informal caregivers of community-dwelling older persons with dementia. Can J Aging. 2000;19(4):494–507.

- Zarit S, Zarit J. Instructions for the burden interview. University Park: Pennsylvania State University; 1987.

- Pignolo RJ, Baujat G, Brown MA, et al. Natural history of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: cross-sectional analysis of annotated baseline phenotypes. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):98.

- Kaplan FS, Strear CM, Zasloff MA. Radiographic and scintigraphic features of modeling and remodeling in the heterotopic skeleton of patients who have fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;304:238–247.

- Al Mukaddam M, Pignolo RJ, Baujat G, et al. A natural history study of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP): 12-month outcomes. J Endocr Soc. 2020;4(Suppl 1):OR29–05.

- Nakahara Y, Kitoh H, Nakashima Y, et al. Longitudinal study of the activities of daily living and quality of life in Japanese patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(6):699–704.

- Zhou T, Guan H, Wang L, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with different diseases measured with the EQ-5D-5L: a systematic review. Front Public Health. 2021;9:675523.

- Poder TG, Wang L, Carrier N. EQ-5D-5L and SF-6Dv2 utility scores in people living with chronic low back pain: a survey from Quebec. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e035722.

- Jiang R, Janssen MFB, Pickard AS. US population norms for the EQ-5D-5L and comparison of norms from face-to-face and online samples. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(3):803–816.

- EURODIS. Juggling care and daily life. The balancing act of the rare disease community. A Rare Barometer survey. 2017. [cited 2022 Aug 10]. Available from: https://innovcare.eu/survey-juggling-care-daily-life-balancing-act-rare-disease-community/

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Percentage of having a doctor visit for any reason in the past 12 months for adults aged 18 and over, United States, 2019–2020. National Health Interview Survey [cited 2022 Feb 5]. Available from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/NHISDataQueryTool/SHS_adult/index.html

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Percentage of having a dental exam or cleaning in the past 12 months for adults aged 18 and over, United States, 2019–2020. National Health Interview Survey [cited 2022 Feb 5]. Available from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/NHISDataQueryTool/SHS_adult/index.html

- International Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva Association (IFOPA). 2020 FOP registry annual report. 2021. [cited 2022 Jun 1].Available from: https://www.ifopa.org/2020_fop_registry_annual_report

- The Canadian Burden of Illness Study Group. Burden of illness of multiple sclerosis: part I: cost of illness. Can J Neurol Sci. 1998;25(1):23–30.

- International Labour Organization. ILO monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. Seventh edition. 2021. [cited 2022 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/coronavirus/impacts-and-responses/WCMS_767028/lang--en/index.htm

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Supplemental data measuring the effects of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on the labor market 2020. Updated 2022. [cited 2022 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/cps/effects-of-the-coronavirus-covid-19-pandemic.htm

- Yang G, Cintina I, Pariser A, et al. The national economic burden of rare disease in the United States in 2019. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022 ;17(1):163.

- Janssen MF, Bonsel GJ, Luo N. Is EQ-5D-5L better than EQ-5D-3L? A head-to-head comparison of descriptive systems and value sets from seven countries. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(6):675–697.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Position statement on use of the EQ-5D-5L value set for England. Updated 2019. [cited 2022 Aug 15]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/nice-guidance/technology-appraisal-guidance/eq-5d-5l