ABSTRACT

Background

Inadequate response to antidepressant medication is common. Often, adjunctive pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy is recommended.

Objective

To measure adherence to adjunctive pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy among individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD).

Methods

Retrospective cohort study of individuals with MDD on antidepressant monotherapy who added adjunctive pharmacotherapy and/or psychotherapy. Medication adherence was measured by proportion of days covered (PDC) with optimal adherence defined as PDC≥0.80 and psychotherapy adherence defined by count of visits (optimal 8+ visits). Factors associated with optimal adherence were assessed by logistic regression.

Results

Among 218,192 individuals with adjunctive therapy, 185,349 added pharmacotherapy and 32,843 added psychotherapy. In the subsequent 12 months, 36.2% and 54.9% achieved optimal adherence to adjunctive pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, respectively. Adherence to adjunctive pharmacotherapy was associated with adding psychotherapy, index antidepressant adherence, medical comorbidities, and MDD severity codes. Adherence to adjunctive psychotherapy was associated with adding another medication, previous psychiatry visit and psychiatric comorbidities.

Conclusion

Adjunctive psychotherapy appears under-utilized and adherence to adjunctive therapy was low. Low adherence to adjunctive therapy reinforces challenges in managing MDD. That a second adjunctive therapy enhanced adherence to the initial adjunctive therapy indicates an opportunity to explore alternative adjunctive therapies.

1. Introduction

Ranked as a leading cause of disability, major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common, chronic episodic condition associated with elevated use of healthcare services [Citation1], reduced productivity, inability to work [Citation2], increased morbidity and mortality [Citation3,Citation4], diminished health-related quality of life [Citation5] and increased risk of suicide [Citation6].

For most individuals with MDD, the initial treatment option is antidepressant pharmacotherapy. There are numerous antidepressant drug classes, which have comparable therapeutic effectiveness. (APA) Despite this array of available treatment options, more than half of MDD patients experience a lack of adequate response with the initial therapy selected [Citation7,Citation8]. In these patients, care often evolves to include augmentation – the addition of a second prescription drug class or of psychotherapy to the treatment regimen – both of which have been shown to be equally effective augmentation strategies [Citation9].

Medication adherence is a significant contributor to treatment response. Low rates of adherence to antidepressant therapy are common [Citation10] and are associated with lack of treatment response [Citation11]. However, much less is known about adherence to pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy used to augment existing therapy. This population represents an important sub-group – one that appears motivated to engage in treatment, having undertaken one course of antidepressant therapy and initiated a second or even third treatment option.

Recently published articles on adherence to augmentation therapy among patients with MDD have focused exclusively on augmentation with atypical antipsychotics [Citation12,Citation13] however, atypical antipsychotics are just one of numerous therapeutic augmentation options. The objective of this research study was to improve our understanding of adherence to adjunctive pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy among patients with MDD and to identify the factors associated with higher levels of adherence.

2. Methods

This research was a retrospective observational cohort study of individuals with MDD who augmented antidepressant monotherapy with either a second antidepressant medication (‘Adjunctive Pharmacotherapy’), psychotherapy (‘Adjunctive Psychotherapy’), or both a second medication and psychotherapy (‘Dual Adjunctive Therapy’). The research protocol received an exempt determination from the Advarra Institutional Review Board.

2.1. Identification and selection of study participants

The sampling frame was the national sample of individuals identifiable in a commercially-available database of medical and pharmacy insurance claims licensed from Clarivate (www.clarivate.com). The study period was 1 January 2014 through 31 December 2019. The case-finding period was 1 July 2014 through 31 December 2018 and was used to identify the adjunctive therapy initiation date (index). The baseline and follow-up periods were the six months prior to and 12 months following index.

Eligible adults had two or more outpatient claims (or one inpatient claim) associated with MDD diagnosis codes (ICD-9-CM (296.2x or 296.3x) or ICD-10-CM (F32.x, F33.x) excluding MDD with psychotic features) on claims separated by at least 30 days; evidence of adjunctive therapy in the period between 1 July 2014 and 31 December 2018; claim(s) for antidepressant medication (alpha-2 receptor antagonist, MAOI, serotonin modulators, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), tricyclic, tetracyclic, or other antidepressant (primarily, bupropion)) before and after initiation of adjunctive therapy, defined as 50% adherence in the 56 days (eight weeks) immediately prior to and following the initiation of adjunctive therapy; evidence of continual insurance benefits eligibility defined by at least one medical or pharmacy claim in each calendar quarter in the baseline and follow-up periods; and had no evidence of psychotherapy in the three months prior to index. Study participants were excluded if they had a paid insurance claim by Medicare or two or more claims associated with bipolar or other depression disorders, dementia, psychosis, schizophrenia, or dissociative and conversion disorders.

The eligible study population was assigned to one of two cohorts: adjunctive pharmacotherapy or adjunctive psychotherapy. The Adjunctive Pharmacotherapy cohort had at least 50% adherence to adjunctive pharmacotherapy in the eight weeks following index and the Adjunctive Psychotherapy population had at least one additional psychotherapy claim in the 56 days following index. Adjunctive pharmacotherapy included the addition of a second antidepressant or an atypical antipsychotic. Adjunctive psychotherapy was defined by CPT codes 90832, 90834, 90837, 90839, 90840, 90845, 90847, 90847, 90853, and 96152.

2.2. Statistical analysis

Demographic variables included age, sex, state of residence, and insurance. Psychiatric comorbidities, measured across the 18-month study period, included generalized anxiety disorder, substance-related disorders, insomnia, alcohol-related disorders, PTSD, dysthymic disorder, and panic disorder. The highest prevalence medical comorbidities included hypertension, lower back pain, hyperlipidemia, obesity, COPD, fatigue, osteoarthritis, diabetes, asthma, and anemia. MDD severity level (mild, moderate, severe, in remission, unspecified) was derived from ICD diagnosis codes in the period prior to index. Individuals with multiple severity classifications were assigned the most severe diagnosis. A psychiatrist visit was defined as a visit to a provider with a psychiatry specialty taxonomy code any time in the 18-month study period.

Adherence measures included discontinuation (a 60-day gap without a subsequent claim following the last available days’ supply) and proportion of days covered (PDC) defined as the total days’ supply associated with paid pharmacy claims in the follow-up period divided by 365 days with adherent defined as PDC≥0.80. Further, beginning on the index date, using the days’ supply associated with each pharmacy claim, and assuming that each day of supply was consumed consecutively, we determined if an individual had drug available on a given day. By summing across all individuals, we calculated and then graphed the expected proportion of individuals with available adjunctive pharmacotherapy drug by day throughout the follow-up period. Adherence to adjunctive psychotherapy was the count of unique claims for psychotherapy service during the follow-up period. Optimal adherence was defined as eight or more sessions, the median number of documented visits in the follow-up period.

Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Differences between categorical variables were tested with Chi-squared tests. Differences between continuous variables were tested with two-sided t-tests for normally distributed variables and Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U-tests for skewed variables. Two separate multivariate logistic regression models were used to identify factors associated with: 1) achieving optimal adherence to augmentation therapy among individuals who augmented with pharmacotherapy and 2) achieving optimal adherence to augmentation therapy among individuals who augmented with psychotherapy.

The threshold for significance was set at 0.05. All analyses were performed with SAS software, v9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA.

3. Results

A total 218,192 met eligibility criteria: 189,091 augmented with pharmacotherapy and 33,516 augmented with psychotherapy. () The population was predominantly female (74.1%), had an average age of 47.8 years, commercially-insured (71.5%), and included residents from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Of the 35.1% of participants who had an MDD claim indicating severity, ‘moderate’ was most common (57.4%) followed by ‘severe’ (28.0%), ‘mild’ (10.5%), and ‘in remission’ (4.1%). The most common psychiatric comorbidities were generalized anxiety disorder (20.8%), substance use disorder (20.5%), and insomnia (15.9%). ()

Table 1. Select demographic, comorbidity, and MDD-related healthcare characteristics.

3.1. Pharmacotherapy vs. psychotherapy

Individuals who augmented with psychotherapy were substantially different than those who augmented with pharmacotherapy, being younger (43.6 vs. 48.5 years; p < 0.01), more likely to be male (27.6% vs. 25.6%; p < 0.01), and to have MDD severity documented at baseline (62.2% vs 30.3%; p < 0.01). Dual augmentation was relatively infrequent, with only 2.6% of the pharmacotherapy group adding psychotherapy during follow up and only 14.3% who augmented with psychotherapy, adding a 2nd drug to the treatment regimen. The psychotherapy group had higher rates of generalized anxiety disorder (58.8% vs. 45.2%; p < 0.01); post-traumatic stress disorder (12.9% vs. 5.1%; p < 0.01); alcohol-related disorders (9.4% vs. 6.0%; p < 0.01); dysthymic disorder (8.6% vs. 5.1%; p < 0.01); and panic attacks (7.6% vs. 4.6%; p < 0.01). The pharmacotherapy group had higher rate of insomnia (17.0% vs. 9.5%; p < 0.01) and substance use disorder (20.7% vs. 19.4%; p < 0.01). ()

Table 2. Demographic characteristics and comorbidities among eligible participants with MDD, by adjunctive therapy.

3.2. Adherence to augmentation therapy

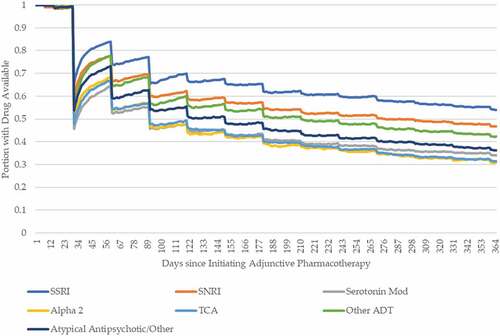

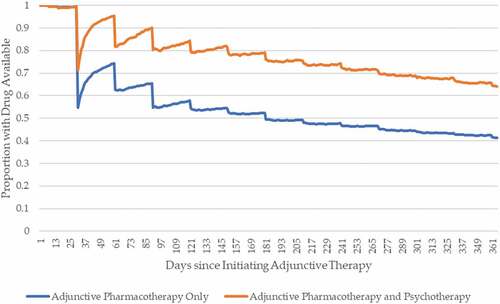

The most frequent augmentation pharmacotherapy class was SSRIs (20.6%) followed by other antidepressants (primarily, bupropion) (17.0%), serotonin modulators (16.1%) and SNRIs (10.9%). () After 12 months, 50.4% of the SSRI group remained on therapy, followed by SNRI (46.8%), other antidepressants (42.2%), and atypical antipsychotics (32.2%). () The overall rate of adherence to augmentation pharmacotherapy was substantially higher among those who also initiated psychotherapy (64.0% on therapy at 12 months compared to 41.4%) compared to those who did not. ()

Figure 2. Adherence to adjunctive pharmacotherapy comparing individuals who did and did not add psychotherapy.

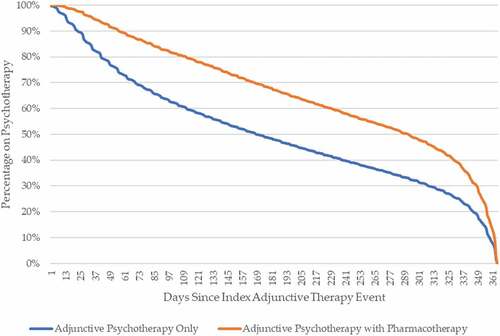

Among the 32,843 individuals who augmented with psychotherapy, 92.8% of the visits were individual therapy with the individual and/or family present, followed by group psychotherapy (4.5%), family psychotherapy (1.6%), health and behavioral assessment (0.8%), and psychotherapy for crisis (0.2%). Overall, the median number of psychotherapy visits was 8 (IQR: 4–15); with individuals who added a 2nd drug to the therapeutic regimen in the follow-up period with a median of 13 visits (IQR: 7–22). Individuals who added a 2nd pharmacotherapy to their regimen remained in psychotherapy significantly longer than those who did not: 68% remained in psychotherapy as of 180 days post-augmentation compared to only 48% of those who did not add a 2nd drug ().

3.3. Factors associated with adherence

Given the study sample size, nearly all factors were significantly associated with adherence to pharmacotherapy and with completing eight or more psychotherapy sessions. () After adjustment, the strongest positive predictor of adherence to adjunctive pharmacotherapy was adherence to index antidepressant therapy (OR: 3.10; 95%CI: 3.02, 3.19)), followed by initiating psychotherapy (OR: 3.03; 95%CI: 2.84, 3.22), age relative to the youngest age group of 18–30 years (65+ years – OR: 1.39; 95%CI: 1.32, 1.46; and 50–64 years – OR: 1.29; 95%CI: 1.24, 1.33); and 31–49 years – OR 1.15; 95%CI: 1.11, 1.19), and the highest coded MDD severity level – relative to severity unspecified (moderate – OR: 1.09; 95%CI: 1.06, 1.12 and severe – OR: 1.07; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.11). () Compared to SSRIs, augmentation with any other drug class was associated with significantly lower odds of adherence and each psychiatric comorbidity was independently associated with a lower odds of achieving adherence to augmentation therapy.

Table 3. Logistic regression results for factors associated with adherence to adjunctive therapy.

After adjustment, fewer factors were associated with the odds of achieving optimal psychotherapy adherence. The strongest positive predictor of adherence to adjunctive psychotherapy was the addition of a 2nd pharmacotherapy during the follow-up period (OR: 2.35; 95%CI: 2.19, 2.52), followed by selected psychiatric comorbidities including anxiety (OR: 1.34), dysthymic disorder (OR: 1.24), and alcohol use disorder (OR: 1.13). The oldest age group (65+ years) and select medical comorbidities were associated with lower odds of achieving optimal psychotherapy adherence. ()

4. Discussion

In this population of nearly 220,000 individuals with MDD, adherence to adjunctive pharmacotherapy was poor, and continuation of psychotherapy was low. However, individuals who initiated a 2nd pharmacotherapy treatment and psychotherapy achieved significantly higher levels of adherence to both augmentation therapies. The likelihood of achieving optimal adherence to adjunctive pharmacotherapy varied by therapeutic class, with the highest adherence among individuals who added SSRIs and SNRIs. Of potentially more significance is the association of adherence with psychiatric comorbidity. Each measured psychiatric comorbidity was associated with lower levels of adherence to augmentation pharmacotherapy while PTSD, alcohol-use disorder, and dysthymic disorder were associated with higher levels of psychotherapy use.

Based on our results, augmenting antidepressant therapy with a 2nd drug is the preferred therapeutic option among those who do not adequately respond to initial treatment. The results of this study are relevant to any clinician who manages individuals with MDD. It is estimated that more than 50% of individuals have an inadequate response to the initial therapy. Among these individuals, providers have various therapeutic options, including changing dose, switching medications, and adding a medication. Given the frequency of augmentation, it is important for clinicians to recognize the high rate of non-adherence, even among a population willing to attempt additional therapeutic options. Our results suggest the importance of monitoring progress.

Despite the prevalence of augmentation, little has been published on adherence to adjunctive pharmacotherapy using real-world data. Recently published results focused only on atypical antipsychotic medications as augmentation therapy. Yan, et al [Citation12]. reported poor adherence among four specific antipsychotic medications – with PDCs ranging from 20.7% to 29.6% and Broder, et al [Citation13]. reported six-month adjusted PDC rates for adjunctive atypical antipsychotic use between 55.5 and 58.9%.

The concept of adherence to psychotherapy is difficult to measure in administrative data. There is no consensus methodology for measuring adherence to psychotherapy visits. Gaspar, et al [Citation14]., defined adherence as four visits in the first month; however, the population studied was more severe and not representative of the broader population of individuals with MDD.

Despite this challenge, it is worth highlighting that several factors that predict adherence to pharmacotherapy also predict non-adherence (or lower rates of) psychotherapy. Older age and several medical comorbidities are associated with higher adherence to pharmacotherapy but less persistence with psychotherapy, while psychiatric care and several psychiatric comorbidities are associated with greater use of psychotherapy but lower adherence to pharmacotherapy.

As defined by the ICD code selected, the severity of MDD appears to play an important role in adherence to augmentation therapy. This finding is difficult to interpret because of the substantial number of codes selected that define severity as ‘unspecified.’ However, our results suggest that selecting an ICD-10 code that includes a severity assessment may be useful for identifying future adherence to therapy. These results are consistent with other studies that indicate ICD-10 coding of MDD severity is clinically valuable, predicting both the risk of relapse and of suicide [Citation15] and that use severity classifications from validated screening questionnaires to predict treatment response [Citation16].

Our results document relatively low rates of adherence to adjunctive therapy, whether pharmaco- or psychotherapeutic. These results may provide information to providers interested in identifying individuals at highest risk of non-adherence and who may benefit from a more intensive care model. More promising, our results indicate that adding a psychotherapeutic intervention to adjunctive pharmacotherapy has a positive influence on medication adherence. These results may represent the cumulative therapeutic effect of complementary interventions or may reflect a selection bias, selecting for individuals and providers with a commitment to therapeutic engagement. In practice, it likely reflects some of each. Teasing out the independent effect of the drug’s therapeutic effect from the impact of an individual’s or provider’s behavior is a significant and long-standing challenge. Nonetheless, given the relatively low rate of psychotherapy [Citation17,Citation18] and the well-documented emotional and practical patient barriers to psychotherapy (i.e. time commitment, cost, stigma) [Citation19,Citation20], these results suggest that alternative therapeutic options – complementary to pharmacotherapy – may have significant benefits to the individual. Finally, if these results hold true, the potential benefits of increased adherence may extend from improved clinical outcomes to improved financial outcomes (lower rates of inpatient and emergency services use).

4.1. Limitations

The study sample represents individuals who elect to add adjunctive pharmacotherapy and/or psychotherapy to an initial antidepressant medication. These results only apply to this population and may not be generalizable to individuals with MDD, overall. Next, the data source does not include insurance benefits eligibility, and may omit some healthcare utilization. This risk is mitigated by the required ongoing use of care, measured by submitted and remitted claims data but cannot be discounted. Further, the study can only infer the intent of treatment and cannot determine reasons for discontinuation. The population has recent diagnoses of MDD, and prescription drug use recommended by guidelines; however, claims cannot confirm the intent for the adjunctive therapeutic intent or the reasons for discontinuation which are well documented [Citation21]. The analysis assumes that adjunctive therapy should persist throughout the 12-month follow up period.

5. Conclusions

Use of psychotherapy as an adjunctive therapy appears under-utilized and adherence to adjunctive therapy, whether medication or psychotherapy, was low. High rates of augmentation coupled with low rates of adherence to augmentation reinforce the challenges faced by providers and individuals in the management of MDD. The insight that an additional therapy appears to enhance adherence to the initial adjunctive therapy indicates an opportunity to explore the synergistic effect of alternative adjunctive therapies, including mHealth and related solutions.

Declarations of interest

J Liberman, C Ruetsch and P Rui are employees of Health Analytics, LLC which was funded to conduct the study. F Forma was an employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. at the time the study was conducted. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

F Forma: Study conception and design; interpretation of results; critical review of manuscript; final approval of submitted version.

J Liberman: Study conception and design; interpretation of results; critical review of manuscript; final approval of the submitted version.

C Ruetsch: Study conception and design; interpretation of results; critical review of manuscript; final approval of the submitted version.

P Rui: Data management and analysis; critical review of manuscript; final approval of the submitted version.

All authors approved the final version for publication and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Margaret L. Stinstrom for her administrative support.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amos TB, Tandon N, Lefebvre P, et al. Direct and indirect cost burden and change of employment status in treatment-resistant depression: a matched-cohort study using a us commercial claims database. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(2):24–32.

- Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, et al. Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3135–3144.

- Jiang W, Alexander J, Christopher E, et al. Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(15):1849–1856.

- van Dooren FE, Nefs G, Schram MT, et al. Depression and risk of mortality in people with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e57058.

- Goldney RD, Phillips PJ, Fisher LJ, et al. Diabetes, depression, and quality of life: a population study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(5):1066–1070.

- Malone KM, Haas GL, Sweeney JA, et al. Major depression and the risk of attempted suicide. J Affect Disord. 1995;34(3):173–185.

- Hiranyatheb T, Nakawiro D, Wongpakaran T, et al. The impact of residual symptoms on relapse and quality of life among Thai depressive patients. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:3175–3181.

- Nil R, Lutolf S, Seifritz E. Residual symptoms and functionality in depressed outpatients: a one-year observational study in Switzerland with escitalopram. J Affect Disord. 2016;197:245–250.

- Gaynes BN, Warden D, Trivedi MH, et al. What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Psych Services. 2009;60(11):1439–1445.

- Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Antidepressant adherence: are patients taking their medications? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012;9(5–6):41–46.

- Fortney JC, Pyne JM, Edlund MJ, et al. Relationship between antidepressant medication possession and treatment response. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):377–379.

- Yan T, Greene M, Chang E, et al. Impact of atypical antipsychotics as adjunctive therapy on psychiatric cost and utilization in patients with major depressive disorder. Clinocecon Outcomes Res. 2020; 12: 81–89.

- Broder MS, Greene M, Yan T, et al. Medication adherence, health care utilization, and costs in patients with major depressive disorder initiating adjunctive antipsychotic treatment. Clin Therapeutics. 2019;41(2):221–232.

- Gaspar FW, Zaidel CS, Dewa CS. Rates and determinants of use of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy by patients with major depressive disorder. Psych Services. 2019;70(4):262–270.

- Kessing LV. Severity of depressive episodes according to ICD-10: prediction of risk of relapse and suicide. Br J Psych. 2004;184(2):153–156.

- Huang SH, LePendu P, Iyer SV, et al. Toward personalizing treatment for depression: predicting diagnosis and severity. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(6):1069–1075.

- Marcus SC, Olfson M. National trends in the treatment for depression from 1998 to 2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(12):1265–1273.

- Gum AM, Hirsch A, Dautovich ND, et al. Six-month utilization of psychotherapy by older adults with depressive symptoms. Community Ment Health J. 2014;50(7):759–764.

- Mohr DC, Hart SL, Howard I, et al. Barriers to psychotherapy among depressed and nondepressed primary care patients. Ann Behav Med. 2006;32(3):254–258.

- Brenes GA, Danhauer SC, Lyles MF, et al. Barriers to mental health treatment in rural older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(11):1172–1178.

- Solmi M, Miola A, Croatto G, et al. How can we improve antidepressant adherence in the management of depression? A targeted review and 10 clinical recommendations. Braz J Psychiatry. 2021;43(2):189–202.