ABSTRACT

Background

The Italian National Health Service (INHS) has recently reimbursed the monoclonal antibody inebilizumab as a second line monotherapy after rituximab (RTX) use for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD) patients ≥ 18 years anti-aquaporin 4 antibody-immunoglobulin G positive, who experienced a relapse in the last year or cannot receive RTX, if incident patients. Other INHS-reimbursed drugs for NMOSD treatment are satralizumab, eculizumab and, off-label, besides RTX, ocrelizumab, tocilizumab, and immunosuppressants.

Research design and methods

A 3-year (2023–2025) prevalence-based budget impact model following the INHS viewpoint compared the costs and the NMOSD attacks without (1st scenario) and with inebilizumab (2nd scenario). The epidemiology of NMOSD, and the INHS-funded healthcare resources (drugs and their administration; specialist visits; hospitalizations due to drug-related adverse events and NMOSD attacks) were obtained from the literature. One-way, threshold value and scenario sensitivity analyses investigated the robustness of the baseline findings.

Results

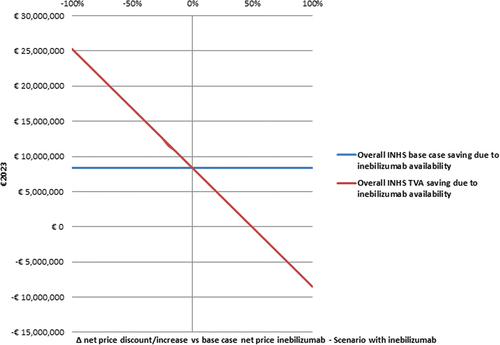

During 2023–2025 inebilizumab saves the INHS €8,373,125.13 (1st scenario: €176,770,028.63; 2nd scenario: €168,396,903.50) and 12.74 NMOSD attacks (1st scenario: 213.94; 2nd scenario: 201.19). Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the baseline results.

Conclusion

Inebilizumab reduces the INHS expenditure for NMOSD drugs. Future research should explore the cost-effectiveness of inebilizumab vs other NMOSD-targeting drugs in Italy.

1. Introduction

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD) is an autoimmune disease of the central nervous system that affects preferentially the optic nerve and spinal cord [Citation1,Citation2].

NMOSD prevalence is estimated in 0.54–6/100,000 individuals worldwide, with higher number of cases in South America and Asia [Citation3,Citation4].

NMOSD is associated primarily with the anti-aquaporin 4 (AQP4) antibody. Positivity to AQP4-immunoglobulin G (IgG) test helps neurologists with differentiating between NMOSD and multiple sclerosis and provides the specialists with a clinical rationale for starting systemic immunosuppressants (including steroids; azathioprine; mycophenolate and rituximab [RTX]) [Citation5–8].

Without effective therapy, ≥50% of NMOSD patients become clinically blind or permanently disabled/unable to walk independently [Citation9–12], and nearly 80%-90% of them experience recurrent NMOSD relapses (also known as attacks), such as optic neuritis, transverse myelitis, or a combination of the symptoms of both, often with a poor recovery after the attack [Citation10,Citation13].

NMOSD patients report remarkable consumption of healthcare resources, for both acute (e.g. high dose corticosteroids and plasma exchange) and long-term therapies (e.g. disease modifying therapies), neuroimaging, specialist visits, and comorbidities, as well as a worsened health-related quality of life [Citation14,Citation15].

Therefore, NMOSD is associated with relevant annual healthcare costs, that yielded €52,000 per patient in US in 2021 [Citation15,Citation16].

Inebilizumab (Uplizna®) (Horizon Therapeutics, Deerfield, IL) is a monoclonal antibody used as monotherapy to treat NMOSD patients aged ≥18 years who tested AQP4-IgG+ [Citation17].

In the N-Momentum trial 21 out of 174 (12%) of the NMNSOD patient on inebilizumab vs. 22 out of 56 (39%) in the control arm experienced an attack, corresponding to a 73% reduction in adjudicated relapse risk over the trial duration (hazard ratio 0.27; 95% CI 0.15–0.50; p < 0.001) [Citation18]. A further analysis showed a reduction of relapse risk by 77% among the AQP4-IgG+ NMOSD patients on inebilizumab vs. their AQP4-IgG+ counterparts who received placebo.

The Italian National Health Service (INHS) has recently reimbursed the monoclonal antibody inebilizumab as a second line monotherapy after RTX use for NMOSD patients ≥18 years anti-aquaporin 4 antibody-immunoglobulin G positive, who experienced a relapse in the last year or cannot receive RTX, if incident patients [Citation17].

The aim of this research is to create a 2-scenario budget impact model (BIM) and compare the costs and the NMOSD attacks following the INHS viewpoint before (1st scenario) and after (2nd scenario) the availability of inebilizumab on the Italian market.

All the parameters that populate the BIM are detailed in the Supplementary Information (SI) Tables SI1-SI14.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Patient population

The number of NMOSD patients was calculated by projecting onto the Italian population [Citation19–21] the prevalence and the incident rates obtained from the NMOSD registry maintained by the Lombardy region (North-West part of the country; 9.94 million inhabitants in 2022) [Citation22,Citation23], subtracted NMOSD-related and age and gender-specific all-cause mortality as reported by Italian life tables [Citation24,Citation25] (Tables SI1-SI4).

The gender-specific prevalence rates for NMOSD were stratified into four age classes and expressed as cases per 100,000 inhabitants: 18–39 years (female: 3.227; male: 1.396); 40–64 years (female: 4.482; male: 1.903); 65–79 years (female: 3.114; male: 1.540); 80–109 years (female: 0.708; male: 1.350). The incident rate, fixed for age and gender, was 0.160 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year [Citation22] (Table SI3). To give a more realistic view, the NMOSD incidence rate was adjusted for age and gender ().

Table 1. Base case analysis – Methods – BIM main parameters – I.

Only prevalent patients were assumed to die. To avoid double-counting, the annual probability of NMOSD-related death (0.015) [Citation24] and age and gender-specific all-cause mortality [Citation25] were considered as competing risks [Citation28]. Consistent with the way prevalence rates for NMOSD were reported [Citation22], age and gender-specific all-cause mortality retrieved from the Italian life tables [Citation25] were stratified in four age classes [Citation28]. The half-cycle correction (that is, the assumption that a patient passes away at six months instead of at the beginning or at the end of the year) was applied [Citation29] (Table SI2).

2.2. Design of the budget impact model

Following the international and the Italian Medicines Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco – AIFA) guidelines [Citation30,Citation31], a prevalence-based BIM was developed in Excel Windows® 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, US).

Both BIM scenarios, which stretch over a 3-year time horizon (2023–2025), included NMOSD patients who tested AQP4-IgG+ and were considered eligible to receive inebilizumab according to the reimbursement conditions negotiated with AIFA [Citation17,Citation26,Citation27] (; Table SI4).

As the patient population is forecast to remain stable during 2023–2025 [Citation19–21], no variation in the number of NMOSD AQP4-IgG+ patients was expected.

In the 1st scenario, that does not include inebilizumab, incident NMOSD patients who were not eligible to receive RTX, and treatment experienced NMOSD patients who suffered a relapse in the last year were administered satralizumab, eculizumab, ocrelizumab, tocilizumab or immunosuppressants (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine or prednisone, as per neurologist’s choice). While ocrelizumab and tocilizumab are used as off-label, second line therapies in NMOSD after RTX, their beneficial effects on NMOSD patients’ health state have been proved [Citation32–34].

In the 2nd scenario inebilizumab is the new entry that broadens the therapeutic options for NMOSD patients in Italy included in the 1st scenario.

When rounded up to the nearest integer, the number of patients eligible for NMOSD therapies different from RTX ranged between 393 (2023) and 394 (2024 and 2025) per year in both scenarios (). The variation in INHS cost due to inebilizumab availability on the Italian market was calculated as the difference between the costs totalized in the two scenarios.

As the BIM is not populated with real patients’ data, no Ethics Committee approval was required by the current Italian legislation [Citation35].

2.3. Market shares

The market shares for all the drugs included in the 1st scenario were retrieved from a recent market research study [Citation36] (; Table SI7).

Table 2. Base case analysis – Methods – BIM main parameters – II.

The availability of inebilizumab was assumed to cause a redistribution of the market shares of NMOSD-targeting drugs that was captured in the 2nd scenario. The variation in the market shares was estimated by means of reasonable forecasts based on the market shares that populated the 1st scenario of the BIM [Citation36] (; Table SI9).

In both scenarios during the 3-year timespan the conditional probability of receiving mycopehate mofetil, azathioprine or prednisone given immunosuppressant therapy was estimated to be constant at 0.330, 0.330 and 0.340, respectively (; Tables SI8 and SI10).

2.4. Healthcare resources

For inebilizumab, satralizumab and eculizumab the annual posology and the number of administrations were obtained from the summary of product characteristics [Citation37–39]. The same parameters were retrieved from the literature for ocrelizumab [33], tocilizumab [Citation34], immunosuppressants (mycophenolate mofetil and azathioprine) [Citation40] and prednisone [Citation41] (; Table SI2).

The route of administration (RoA) was subcutaneous (sc) for satralizumab and per os for immunosuppressants, whereas for the other drugs the RoA was infusional (Table SI2).

A first and a follow-up specialist visits per year were assumed for all the drugs that were administered sc or per os, whereas patients receiving infusion therapy were hypothesized to be assessed upon drug administration without the need of further specialist visits (; Table SI11).

As reported by other authors [Citation49] patients’ perfect medication compliance to drug prescription was assumed in both scenarios.

The drug-specific annual attack rate (AAR) was obtained from randomized clinical trials for inebilizumab, satralizumab, eculizumab, and immunosuppressants [Citation32,Citation43–45] (; Tables SI3 and SI14).

Ocrelizumab and tocilizumab were assumed to have the same AAR of RTX (0.157) [Citation32] for two different reasons. Ocrelizumab and RTX share the same mechanism of action [Citation50], whereas there is no evidence that tocilizumab is more effective than RTX or ocrelizumab.

In addition, the AAR estimate of tocilizumab was conservative, as the only available study on this drug was conducted on high-activity NMOSD patients whose AAR was 0.4 [Citation34] instead of 0.157 [Citation32].

The probability of NMOSD drugs-related level ≥ 3 [Citation51] adverse events (AEs) was provided by literature [Citation18,Citation26,Citation43,Citation48] (; Tables SI5 and SI6).

For all the drugs the AAR as well as the probability of experiencing a given NMOSD drug-related AE were kept constant during the 3-year timespan the BIM stretches over (; Tables SI3, SI5 and SI6).

No healthcare resource concerning NMOSD diagnosis and Emergency Room visits were considered, as their consumption was not assumed to differ among the drugs included in the BIM.

2.5. Cost

Consistent with the BIM viewpoint, only INHS-funded healthcare resources were costed (; Tables SI12 and SI13). Drugs were valued at their net price that is, ex-factory price x 0.95^2 [Citation17,Citation52–57]. Hidden discount (that is, the mandatory reduction of the ex-factory price reported in the AIFA decree issued after the reimbursement decision. The hidden discount should be acknowledged by drug manufacturer to public hospitals and sometimes also to private hospitals endorsed by INHS as healthcare services providers) was not considered, as the percentage of the hidden discount on the ex-factory price is kept confidential between AIFA and the manufacturer [Citation58].

Infusion drug administrations, as well as specialist visits, were valued according to the version of the INHS tariffs for outpatient procedures currently in force [Citation42] ( ; Table SI12).

Per os and sc RoAs were not costed as patient self-administration was assumed.

As NMOSD patients are oftentimes severely ill [Citation14,Citation15], NMOSD attacks and NMOSD drugs-related AEs were assumed to be managed in hospital setting and costed via the last updated Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs) tariffs adopted by the INHS [Citation46].

As the Italian DRGs tariffs for inpatient and day-hospital stay differ, a weighted DRG tariff for AAR and each NMOSD drug-related AE was calculated, the weight being the last available national number of medical and surgical DRG-specific discharges from inward and day-hospital settings with and without complications or comorbidities for patients aged ≥18 years, as reported by the Italian Ministry of Health [Citation47] ( ; Tables SI12 and SI13).

Costs were expressed in €2023 values.

Following the recommendations of the literature on BIM [Citation30] costs were not discounted.

2.6. Statistical analysis

A parametric 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was calculated for all the BIM parameters (167/244 = 68.44%) whose uncertainty could be modeled via a theoretical probability distribution [Citation29,Citation59,Citation60]. Whenever the sample size (N) was available, the standard error (SE) of the sampling distribution of the parameter was calculated analytically. A coefficient of variation was imposed on the parameter point estimate to determine the SE of the mean if N could not be collected from the data [Citation29,Citation59,Citation60].

The Gamma distribution was applied to NMOSD prevalence and incidence rates as well as AARs (Table SI3).

The Beta distribution was assigned to binomial data (e.g. probability for a NMOSD patient to be tested for AQP4-IgG) (Tables SI4-SI6).

A Dirichlet distribution was fitted to multinomial data (e.g. market shares of the different drugs in both scenarios the BIM is composed of) (Tables SI7-SI 10).

If different from drugs, the uncertainty concerning the volume and the unit cost of healthcare resources consumed by notional NMOSD patients was modeled via a Gamma and a Normal distribution, respectively (Tables SI11-SI 13).

Drug posology, administrations and cost are exogenous parameters [Citation59] as their value is approved or set by international or national regulatory agencies (e.g. European Medicines Agency; AIFA). Therefore, their values are certain (; Table S2).

Sample estimates and ranges for age-specific forecasts of the Italian population were retrieved from the same official sources [Citation19–21] (Table S1).

2.7. Sensitivity analyses

The robustness of the base case results was checked via a comprehensive set of sensitivity analyses [Citation61,Citation62].

2.7.1. One-way sensitivity analysis

The way each one of the 244 parameters included in the BIM contributed to the cost difference for the INHS between the 1st and 2nd scenarios was first investigated via one-way sensitivity analysis (OWSA). In OWSA the bounds of the range or 95% CI replaced the sample estimate of each parameter at a time while keeping the other ones unchanged [Citation30,Citation31,Citation61,Citation62].

2.7.2. Scenario sensitivity analysis

The reliability of the base case results was also explored via five scenario sensitivity analyses (SSA) [Citation30,Citation31,Citation61,Citation62].

A first SSA tested if a reduction of the BIM time horizon (from 1 up to 2 years) changes the base case findings due to a progressive but incomplete redistribution of the market shares after the entry of inebilizumab in the Italian market.

A second SSA assumed that only patients belonging to one of the four age class (18–39; 40–64; 65–79; 80–109 years) entered the BIM at a time.

In a third SSA the baseline prevalence and incidence rates were replaced by the lower and upper bounds of their 95% CIs.

The same replacement was made for AAR in the fourth SSA.

The fifth SSA investigated three different hypotheses of extreme redistribution of the market shares of inebilizumab, satralizumab and eculizumab in the 2nd scenario of the BIM in which inebilizumab was available. Each drug was assumed to capture the market shares of the remaining two and the subsequent effect on the INHS saving was calculated. The other medications maintained the market shares estimated in the 2nd scenario of the BIM ().

2.7.3. Threshold value analyses

Threshold value analysis (TVA) aims at determining the critical value of a given parameter (or a set of parameters) after which the baseline results reverse (e.g. the base case saving becomes an additional cost for the third-party payer) [Citation61–63].

Both TVAs refer to the 2nd scenario of the BIM as they assumed the availability of inebilizumab.

The first TVA investigated the effect of a variation (±10% at a time) in the 3-year average market share for inebilizumab (from −100% to + 100% vs baseline BIM) counterbalanced by an equivalent variation in the market shares of satralizumab and eculizumab.

The second TVA explored the impact of reducing or increasing (±5% at a time) the net price of inebilizumab (from −100% to + 100% vs baseline BIM).

3. Results

3.1. Base case analysis

The annual and 3-year per patient costs for the drugs included in the BIM are reported separately (Tables SI15-SI 23) and, unlike the BIM scenarios, they are calculated without taking the respective market shares into account. During the 3-year time horizon their amounts vary from €5995.85 (immunosuppressants) (Table SI23) to €1,310,512.56 (eculizumab) per patient (Table SI17).

As far as the BIM is concerned, the overall cost for the INHS yields €176,770,028.63 (1st scenario; inebilizumab unavailable on the Italian market) and €168,396,903.50 (2nd scenario; inebilizumab available on the Italian market). For both scenarios, the cost for the INHS is led by the cost of drugs that totaled €175,802,696.50 and €167,480,869.43 (or 99.45% and 99.46% of the overall cost), respectively (). Conversely, the office visits showed the smallest contribution to the overall cost (0.02%), with €33,943.82 and €30,755.18 in the 1st and 2nd scenario, respectively.

Table 3. Base case analysis – Results – Cost and saving for the INHS – I – Scenario without inebilizumab (€2023)a.

Table 4. Base case analysis – Results – Cost and saving for the INHS – II – Scenario with inebilizumab (€2023)a.

The availability of inebilizumab on the Italian market reduces the number of NMOSD attacks from 213.94 to 201.19, with a difference of 12.74 over the 3-year time horizon (; Table SI24), whereas the cost of managing the NMOSD relapses does not exceed 0.26% (€455,034.77) and 0.24% (€427,931.89) of the 3-year INHS cost in the 1st and 2nd scenario, respectively ().

Figure 1. Base case analysis - Number of NMOSD attacks - Scenario without inebilizumab (Panel A), scenario with inebilizumab (Panel B) and difference between the two scenarios (Panel C)

The availability of inebilizumab on the Italian market generates a €8,373,125.13 overall saving for the INHS, that was mainly due to a reduction in public expenditure for NMOSD-targeting drugs (€8,321,827.07, or 99.39% of the INHS total saving) ().

3.2. Sensitivity analyses

3.2.1. One-way sensitivity analysis

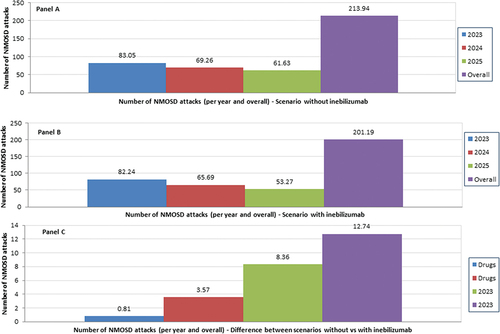

All the OWSA findings are consistent with the baseline results in showing a 3-year saving for the INHS due to inebilizumab entering the Italian market ().

Figure 2. One-way sensitivity analysis - Results concerning the first 10 parameters of the BIM that causes the largest variations in the base case INHS saving due to inebilizumab availability (€8,373,125.13) (€2023). a

Interestingly, the market shares that populated the 1st and the 2nd BIM scenarios represent 9 out of the 10 most relevant OWSA parameters.

The overall INHS saving calculated in the base case BIM is most sensitive to variations in the market share for eculizumab in 2025 in the 1st scenario (from −89.01% to + 94.75% vs baseline results).

Conversely, changes in the satralizumab market share in 2025 (1st scenario) have a mild leveraging on the 3-year INHS saving (from −18.85% to + 19.12% vs baseline results).

3.2.2. Scenario sensitivity analysis

The first SSA highlights the role of the increasing market share for inebilizumab in the 2nd scenario, as 46.38% of the overall saving for the INHS is generated during the 3rd year ().

Table 5. Scenario sensitivity analysis – Results (€2023).

The results of the second SSA are consistent with the epidemiology of NMOSD in Italy. Since the highest prevalence of the disease is reported for the 40–64 age class, populating the BIM solely with this stratum of patients causes the lowest reduction in the overall INHS saving vs baseline analysis (−45.00%).

The third SSA shows that replacing the point estimate of age and gender-specific prevalence and incidence rates with the lower and the upper bounds of their respective 95% CIs, produces remarkable departures from the overall INHS saving estimated in the base case BIM (−65.46% and + 76.52%, respectively).

The fourth SSA proves the impact on the 3-year INHS saving due to the same replacement for AAR to be negligible (−0.20% and + 0.30% vs baseline analysis, respectively), while sparing 4.80 and 24.50 attacks (−62.32% and + 92.31% vs base case findings, respectively).

The findings of the fifth SSA confirms the cost-saving profile of inebilizumab. When inebilizumab captures the market shares of satralizumab and eculizumab, the overall saving for the INHS reaches €88,423,663.95 with 14.64 NMOSD attacks spared (+956.04% and +14.91% vs base case results, respectively), whereas it raises to €98,243,921.77, but with 6.69 more NMOSD attacks (+1073.32% and −152.49% vs baseline BIM, respectively) when both inebilizumab and eculizumab are totally replaced by satralizumab. Conversely, when the market shares of inebilizumab and satralizumab are assumed to drop to zero in favor of eculizumab, the overall saving for the INHS becomes negative. Put differently, this last hypothesis creates an expected INHS overall cash outlay of €158,097,898.74 while saving 39.01 NMOSD attacks (−1988.16% and + 206.22 vs base case analysis, respectively).

Interestingly, even under these extreme redistribution of market shares, inebilizumab only increases the INHS saving and reduces NMSOD attacks when compared to the baseline findings.

3.2.3. Threshold value analyses

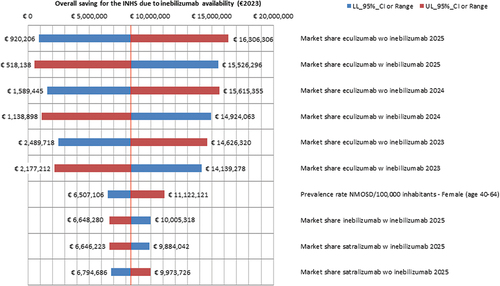

The first TVA shows that the 3-year saving for the INHS becomes < 0 only if the baseline 3-year mean market share of inebilizumab drops by ≥ 30% (). Doubling the average market share of inebilizumab (that is, from 0.117 to 0.233) during the timespan the BIM stretches over, has a 4.61-time multiplicative effect on the overall INHS savings calculated in the base case analysis (€38,594,983.99 vs €8,373,125.13).

Figure 3. Threshold value analysis – I - Effect of inebilizumab market share variation on the base case INHS saving due to inebilizumab availability (€8,373,125.13) (€2023).a

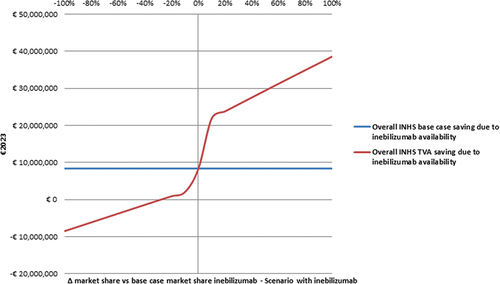

As shown by the second TVA, the overall saving for the INHS proves to be robust against extreme increases in the inebilizumab net price, as the 3-year saving for the INHS becomes < 0 only if inebilizumab net price increases by ≥ 50% ().

4. Discussion

This research reports on a two-scenario BIM aimed at investigating the variations in INHS cost caused by the availability of inebilizumab as a new treatment for NMOSD in Italy.

Inebilizumab entry displaces mainly the use of other drugs also approved for the treatment of NMOSD, such as satralizumab and eculizumab [Citation17,Citation37,Citation39,Citation54,Citation55], and also prevents a remarkable number of NMOSD attacks.

According to the baseline results and the findings of the comprehensive set of sensitivity analyses inebilizumab is expected to reduce by €1.14-€88.42 million the cost of managing NMOSD patients for the INHS, in addition to saving 4.80–24.50 NMOSD attacks.

No previous researchers investigated the impact of inebilizumab on the costs borne by third-party payers of other jurisdictions. In addition, BIMs concerning other drugs targeting NMOSD are poorly represented in the health economic literature.

According to the results of a Markov model-supported BIM performed in Thailand, when prescribed to 84 out of 280 NMOSD notional patients who were resistant to azathioprine, the 3-year BIM for mycophenolate mofetil and RTX biosimilar with CD27+ memory B cell monitoring ranged between 33,000–198,000 US dollars (USD), 2019 values [Citation64].

However, the literature provides cost descriptions [Citation62] on NMOSD that can be considered for comparing the results of the BIM detailed at the previous paragraphs.

A retrospective cost description that took into account 2014–2018 insurance claims concerning 162 US NMOSD patients retrieved from the IBM MarketScan US database, revealed that the cost for drugs was, on average, USD 6349 per year, or 10.12% of the mean overall cost per NMOSD patient [Citation65], which is way lower than the 99.45% reported in our research.

Provided that comparison of costs totaled by patients with the same disease but managed in different healthcare systems brings about some methodological issues [Citation66], it is also worth mentioning that these insurance claims date back to an era of cheaper drugs, when eculizumab, inebilizumab and satralizumab were not yet available for NMOSD AQP4+ patients [Citation65].

A US cross-sectional survey that enrolled 193 NMOSD patients showed the cost for drugs (mainly RTX [60.6%], prednisone/corticosteroid [20.2%], mycophenolate mofetil [17.1%], and azathioprine [14.5%]) to sum up to USD262,598 (year unspecified), that is the 40.83% of the overall healthcare costs (USD643,103) [Citation67]. Interestingly, and consistent with two of the assumptions made in our research, less than one half of the patients enrolled in the survey (82, or 42.4%) were examined every six months and those on RTX were assessed by physicians just before the drug infusion, with no need for further follow-up visits during the year.

A rapid review reported on the cost of managing a NMOSD AQP4+ patient during a 3-year timespan with eculizumab in US to be twice as costing as with inebilizumab (USD 2,100,000 vs USD 917,000) [Citation68], but also highlighted that inebilizumab is 25–40 times more expensive than RTX. As far as the Italian setting is concerned, RTX is not a competitor of inebilizumab, as the place in therapy for inebilizumab is a second line treatment for NMOSD AQP4+ patients who switched from RTX for effectiveness and/or safety reasons [Citation17].

The main limitation of our research rests on the recent entry of inebilizumab in the Italian market. Therefore, this 2-scenario BIM is basically a forecasting exercise that is assumed to be informative for the INHS decision makers as well as for the neurologists dealing with NMOSD patients in Italy. While it is apparent that the redistribution of the market shares across the two scenarios because of inebilizumab drives the saving for the INHS, it remains to be seen how the Italian market for NMOSD drugs will react to the availability of inebilizumab in the years to come.

In addition, future empirical economic evaluations performed alongside clinical trials comparing inebilizumab vs other NMOSD drugs in the real-world setting should focus on the difference, in terms of cost and saving for the INHS, between active and non-active phases of the disease [Citation69], a topic that our research does not cover.

Besides, NMOSD attacks and NMOSD drugs-related AEs management was costed according the Italian DRG tariffs that reimburse hospitals via an all-inclusive perspective lump sum [Citation46]. This approach is in line with the INHS perspective adopted in the BIM [Citation31] and the research assumption that, being oftentimes severely ill [Citation14,Citation15], NMOSD patients are cared for in inpatient setting. However, the DRG scheme does not allow to single out the healthcare services that contribute to the production of a hospitalization episode [Citation62], making any micro-costing exercise unfeasible and double-counting (that is, costing the same healthcare resource twice) prone. Hence, it remains to be seen whether the DRG tariffs-based valuation of healthcare resources is a fair and true proxy for the real cost borne by hospitals for treating NMOSD attacks and NMOSD drugs-related AEs [Citation70]. That said, it would be interesting if future research following the hospital or the societal perspective [Citation62] could derive an average empirical cost for managing NMOSD patients in Italy in inpatient and outpatient settings, as already reported for Germany [Citation15,Citation69].

Eventually, we assumed that the NMOSD notional patients included in the BIM were totally compliant to their therapies [Citation49]. The plausibility of this research hypothesis in the real world setting and its bearing on the INHS saving due to the availability of inebilizumab on the Italian marker should be investigated in future clinical and health economic studies.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, according to our base case assumptions the reimbursement of inebilizumab is expected to generate about €8 million saving for the INHS during a 3-year time horizon. While this should be seen as an outstanding achievement for INHS decision makers who manage the public expenditure for drugs, future complete economic evaluation of healthcare programs [Citation62] should also explore the cost-effectiveness [Citation62,Citation71] of inebilizumab when compared to other drugs targeting NMOSD in Italy.

Declaration of interest

C Lazzaro has received an unconditional research grant from Horizon Therapeutics S.r.l., Milan, Italy. Outside this research, in the past three years C Lazzaro has received research grants, speaker or consultancy fees from AstraZeneca S.p.A, Ipsen S.p.A., Janssen-Cilag SPA, Roche S.p.A., Roche Diagnostics S.p.A., Sanofi s.r.l., Santen GmbH. N A Mazzanti and S Rossi are employees and equity owners of Horizon Therapeutics S.r.l., Milan, Italy. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Declaration of generative artificial intelligence in scientific writing

Authors declare that no section of this manuscript, including tables, figures and supplemental information was supported by Artificial Intelligence.

Author contributions

C Lazzaro: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Manuscript preparation, Manuscript review. N A Mazzanti: Conceptualization, Data curation, Manuscript review. S Rossi: Conceptualization, Data curation, Manuscript review. F Parazzini: Conceptualization, Expert suggestions, Manuscript review. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Reviewer disclosures

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed receiving consulting and board fees from Horizon therapeutics. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Complying with ethics of experimentation

Ethical approval was not needed.

Consent

Participatory consent was not needed.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (196.8 KB)SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2023.2267176

Additional information

Funding

References

- Wingerchuk DM, Banwell B, Bennett JL, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology. 2015;85(2):177–189. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001729

- Patterson SL, Goglin SE. Neuromyelitis optica. North Am. 2017;43(4):579–591. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2017.06.007

- Pandit L, Asgari N, Apiwattanakul M, et al.; GJCF International clinical consortium & biorepository for neuromyelitis optica. Demographic and clinical features of neuromyelitis optica: a review. Mult Scler. 2015;21(7):845–853. doi: 10.1177/1352458515572406.

- Katz Sand I. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2016;22(3):864–896. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000337

- Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF. Neuromyelitis optica and the evolving spectrum of autoimmune aquaporin-4 channelopathies: a decade later. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1366(1):20–39. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12794

- Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, et al. Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2006;66(10):1485–1489. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000216139.44259.74

- Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Lucchinetti CF, et al. The spectrum of neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(9):805–815. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70216-8

- Jarius S, Frederikson J, Waters P, et al. Frequency and prognostic impact of antibodies to aquaporin-4 in patients with optic neuritis. J Neurol Sci. 2010;298(1–2):158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.07.011

- Wingerchuk DM, Hogancamp WF, O’Brien PC, et al. The clinical course of neuromyelitis optica (Devic’s syndrome). Neurology. 1999;53(5):1107–1114. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.5.1107

- Kitley J, Leite MI, Nakashima I, et al. Prognostic factors and disease course in aquaporin-4 antibody-positive patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder from the United Kingdom and Japan. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 6):1834–1849. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws109

- Borisow N, Mori M, Kuwabara S, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of NMO spectrum disorder and MOG-encephalomyelitis. Front Neurol. 2018;9:888. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00888

- Kim H, Park KA, Oh SY, et al. Association of optic neuritis with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and multiple sclerosis in Korea. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2019;33(1):82–90. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2018.0050

- Jarius S, Ruprecht K, Wildemann B, et al. Contrasting disease patterns in seropositive and seronegative neuromyelitis optica: a multicentre study of 175 patients. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:14. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-14

- Ajmera MR, Boscoe A, Mauskopf J, et al. Evaluation of comorbidities and healthcare resource use among patients with highly active neuromyelitis optica. J Neurol Sci. 2018;384:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2017.11.022

- Hümmert MW, Schöppe LM, Bellmann-Strobl J, et al. Neuromyelitis Optica Study Group (NEMOS). Costs and health-related quality of life in patients with NMO spectrum disorders and MOG-antibody-associated disease: CHANCENMO study. Neurology. 2022;98(11):e1184–e1196. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200052

- Royston M, Kielhorn A, Weycker D, et al. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: clinical burden and cost of relapses and disease-related care in US clinical practice. Neurol Ther. 2021;10(2):767–783. doi: 10.1007/s40120-021-00253-4

- Agenzia Italiana Del Farmaco. Determina 13 marzo 2023. Regime di rimborsabilità e prezzo, a seguito di nuove indicazioni terapeutiche, del medicinale per uso umano «Uplizna». (Determina n.209/2023). (23A01736). Rome Italian: Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. Vol. n.71. Mar 24 2023; p. 35–37.

- Cree BAC, Bennett JL, Kim HJ, et al. N-MOmentum study investigators. Inebilizumab for the treatment of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (N-MOmentum): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10206):1352–1363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31817-3

- Sistema Statistico Nazionale - Istituto Nazionale di Statistica [Internet]. Demo-Geodemo. Previsioni della popolazione residente per sesso, età e regione - Base 1/1/2021. Ripartizione: Italia - Maschi e femmine - Anno: 2023. Rome: Sistema Statistico Nazionale - Istituto Nazionale di Statistica; [updated 2022 Jan 1; cited 2023 Mar 31]. Available from: http://demo.istat/it. Italian.

- Sistema Statistico Nazionale - Istituto Nazionale di Statistica [Internet]. Demo-Geodemo. Previsioni della popolazione residente per sesso, età e regione - Base 1/1/2021. Ripartizione: Italia - Maschi e femmine - Anno: 2024. Rome: Sistema Statistico Nazionale - Istituto Nazionale di Statistica; [ updated 2022 Dec 31; cited 2023 Mar 31]. Available from: http://demo.istat.it/Italian.

- Sistema Statistico Nazionale - Istituto Nazionale di Statistica [Internet]. Demo-Geodemo. Previsioni della popolazione residente per sesso, età e regione - Base 1/1/2021. Ripartizione: Italia - Maschi e femmine - Anno: 2025. Rome: Sistema Statistico Nazionale - Istituto Nazionale di Statistica; [ updated 2022 Dec 31; cited 2023 Mar 31]. Available from: http://demo.istat.itItalian.

- Sistema Statistico Nazionale - Istituto Nazionale di Statistica [Internet]. Demo-Geodemo. Ricostruzione della popolazione 2002-2019. Ripartizione: Lombardia - Maschi e femmine - Anno: 2016. Rome: Sistema Statistico Nazionale - Istituto Nazionale di Statistica; [ updated 2018 Dec 31; cited 2023 Mar 31]. Available from: http://demo.is.tat.it. Italian.

- Regione Lombardia [Internet]. Open data. Neuromielite ottica. Regione Lombardia; [updated 2021 Jun 11; cited 2023 Mar 31]. Available from: https://www.dati.lombardia.it/stories/s/4vth-4xkw.Italian

- Mealy MA, Kessler RA, Rimler Z, et al. Mortality in neuromyelitis optica is strongly associated with African ancestry. Neurol(r) Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammation. 2018;5(4):e468. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000468

- Sistema Statistico Nazionale - Istituto Nazionale di Statistica [Internet]. Demo-Geodemo. Mappe, Popolazione, Statistiche Demografiche dell’ISTAT. Tavole di mortalità della popolazione residente. Ripartizione: Italia - Maschi e femmine - Anno: 2021. Rome: Sistema Statistico Nazionale - Istituto Nazionale di Statistica; [ updated 2022 Jan 1; cited 2023 Feb 8]. Available from: http://demo.ist.at.it.Italian.

- Barreras P, Vasileiou ES, Filippatou AG, et al. Long-term effectiveness and safety of rituximab in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and MOG antibody disease. Neurology. 2022;99(22):e2504–e2516. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000201260

- Strategic Research Insight (SRI). UPLIZNA Italy landscape study. Princeton NJ: SRI; 2021 Sep 24.

- Briggs A, Sculpher M, Dawson J, et al. The use of probabilistic decision models in technology assessment: the case of total hip replacement. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2004;3(2):79–89. doi: 10.2165/00148365-200403020-00004

- Briggs A, Sculpher M, Claxton K. Decision modelling for health economic evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

- Sullivan SD, Mauskopf JA, Augustovski F, et al. Budget impact analysis-principles of good practice: report of the ISPOR 2012 budget impact analysis good practice II task force. Value Health. 2014;17(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.08.2291

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco [Internet]. Linea guida per la compilazione del dossier a supporto della domanda di rimborsabilità e prezzo di un medicinale ai sensi del D.M. 2 agosto 2019. Versione 1.0. Rome: Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco; [updated 2020 Dec 30; cited 2023 Apr 22]. Available from: https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/-/l-aifa-approva-le-nuove-linee-guida-per-la-contrattazione-dei-prezzi-e-rimborsi-dei-farmaci.Italian.

- Velasco M, Zarco LA, Agudelo-Arrieta M, et al. Effectiveness of treatments in neuromyelitis optica to modify the course of disease in adult patients. Systematic review of literature. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;50:102869. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.102869

- Kümpfel T, Thiel S, Meinl I, et al. Anti-CD20 therapies and pregnancy in neuroimmunologic disorders: a cohort study from Germany. Neurol(r) Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammation. 2020;8(1):e913. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000913

- Ringelstein M, Ayzenberg I, Harmel J, et al. Long-term therapy with interleukin 6 receptor blockade in highly active neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(7):756–763. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.0533

- della Salute M. Decreto 8 febbraio 2013. Criteri per la composizione e il funzionamento dei comitati etici. (13A03474). Rome: Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana, Serie Generale, n. 96 del 24 aprile 2013; 12–21. Italian.

- Strategic Research Insight (SRI). UPLIZNA Italy baseline ATU report. Princeton NJ: SRI; 2022 Oct 12.

- European Medicines Agency [Internet]. Enspryng, INN-satralizumab. Annex I. Summary of product characteristics. Amsterdam: European Medicines Agency; [ updated 2021 Sep 15; cited 2023 Feb 10]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/enspryng-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- European Medicines Agency [Internet]. Uplizna, INN-inebilizumab. Annex I. Summary of product characteristics. Amsterdam: European Medicines Agency; [ updated 2022 Nov 11; cited 2023 Feb 10]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/uplizna-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- European Medicines Agency [Internet]. Soliris, INN-eculizumab. Annex I. Summary of product characteristics. Amsterdam: European Medicines Agency; [ updated2022 Nov 14; cited 2023 Feb 10]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/soliris-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Kimbrough DJ, Fujihara K, Jacob A, et al.; GJCF-CC&BR. Treatment of neuromyelitis optica: review and recommendations. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2012;1(4):180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2012.06.002.

- Agenzia Italiana Del Farmaco [Internet]. Prednisone. Riassunto delle caratteristiche del prodotto. Rome: Agenzia Italiana Del Farmaco; [ updated 2018 Jul 6; cited 2023 Feb 15]. Available from: https://farmaci.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/aifa/servlet/PdfDownloadServlet?pdfFileName=footer_002298_042725_RCP.pdf&sys=m0b1l3.Italian.

- Ministero della Salute. Decreto 18 ottobre 2012. Remunerazione prestazioni di assistenza ospedaliera per acuti, assistenza ospedaliera di riabilitazione e di lungodegenza post acuzie e di assistenza specialistica ambulatoriale. (13A00528). Rome: Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n. 23 [Internet]. 2013 Jan 28 [cited 2023 Apr 30]. Allegato 3 Prestazioni di assistenza specialistica ambulatoriale. Available from: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderPdf.spring?seriegu=SG&datagu=28/01/2013&redaz=13A00528&artp=3&art=1&subart=1&subart1=10&vers=1&prog=001. Italian.

- Pittock SJ, Berthele A, Fujihara K, et al. Eculizumab in aquaporin-4-positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(7):614–625. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900866

- Kleiter I, Traboulsee A, Palace J, et al. Long-term efficacy of satralizumab in AQP4-IgG-seropositive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder from SAkuraSky and SAkuraStar. Neurol(r) Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammation. 2022;10(1):e200071. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000200071

- Rensel M, Zabeti A, Mealy MA, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of inebilizumab in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: analysis of aquaporin-4-immunoglobulin G-seropositive participants taking inebilizumab for ≥4 years in the N-MOmentum trial. Mult Scler. 2022;28(6):925–932. doi: 10.1177/13524585211047223

- Conferenza Permanente per i Rapporti tra lo Stato le Regioni e le Province Autonome di Trento e Bolzano [Internet]. Accordo, ai sensi dell’articolo 9, comma 2, dell’Intesa n. 82/CSR del 10 luglio 2014 concernente il nuovo Patto per la Salute per gli anni 2014-2016, sul documento recante “Accordo interregionale per la compensazione della mobilità sanitaria aggiornato all’anno 2020 - Regole tecniche”. Rome: Conferenza Permanente per i Rapporti tra lo Stato le Regioni e le Province Autonome di Trento e Bolzano; [ updated 2021 Jun 3; cited 2023 Apr 22]. Available from: https://www.statoregioni.it/media/4032/p-3-csr-atto-rep-n-174-22set2021-corretto.pdf. Italian.

- Ministero della Salute [Internet]. Rapporto annuale sull’attività di ricovero ospedaliero. Dati SDO 2020. Rome: Ministero dellaSalute; [updated 2022 Jul; cited 2023 Apr 22]. Available from: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_3277_allegato.pdf. Italian.

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (CADTH) [Internet]. CADTH common drug review - clinical review report satralizumab (enspryng). Table 17. Ottawa: Ottawa: CADTH; [updated 2021 Jun; cited 2023 Apr 22]. Available from: https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/cdr/clinical/sr0663-enspryng-clinical-review-report.pdf

- Oppe M, Muresan B, Chan K, et al. Budget impact of introducing subcutaneous vedolizumab as a maintenance therapy in biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced patients with ulcerative colitis in France. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2023;23(2):205–213. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2023.2160322

- European Medicines Agency [Internet]. Ocrevus, INN-ocrelizumab. Annex I. Summary of product characteristics. Amsterdam: European Medicines Agency; [ updated2022 Oct 3; cited 2023 Feb 10]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/ocrevus-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [Internet]. Common Terminology Criteria For Adverse Events (CTCAE). Version 5.0. (WA) DC US: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; [updated 2017 Nov 27; cited 2023 Apr 20]. Available from: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_5x7.pdf

- Agenzia Italiana Del Farmaco. Determinazione 27 settembre 2006.Manovra per il governo della spesa farmaceutica convenzionata e non convenzionata. Rome: Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n.227. Sep 29 2006; p. 58–59. Italian.

- Agenzia Italiana Del Farmaco. Determina 21 febbraio 2022. Rinegoziazione del medicinale per uso umano «Ocrevus», ai sensi dell’art. 8, comma 10, della legge 24 dicembre 1993, n. 537. (Determina n. 164/2022). (22A01395). Rome: Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n.53. Mar 4 2022; p. 22–24. Italian.

- Agenzia Italiana Del Farmaco. Determina 5 settembre 2022. Regime di rimborsabilità e prezzo, a seguito di nuove indicazioni terapeutiche, del medicinale per uso umano «Soliris». (Determina n. 596/2022). (22A05103). Rome: Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n.210 Italian; 2022 Sep 8p. 8–10.

- Agenzia Italiana Del Farmaco. Determina 5 settembre 2022. Riclassificazione del medicinale per uso umano «Enspryng», ai sensi dell’articolo 8, comma 10, della legge 24 dicembre 1993, n. 537. (Determina n. 588/2022). (22A05108). Rome: Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n.211 Italian; 2022 Sep 9p. 41–43.

- Agenzia Italiana Del Farmaco. Determina 13 gennaio 2023. Regime di rimborsabilità e prezzo, a seguito di nuove indicazioni terapeutiche, del medicinale per uso umano «Roactemra». (Determina n. 2/2023). (23A00318). Rome: Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n.20. Jan 13 2023; p. 51–54. Italian.

- Agenzia Italiana Del Farmaco [Internet]. Liste di trasparenza. Rome: Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco; [updated 2023 Feb 15; cited 2023 Feb 15]. Available from https://www.aifa.gov.it/liste-di-trasparenza. Italian.

- Ministero della Salute. Decreto 2 agosto 2019. Criteri e modalità con cui l’Agenzia italiana del farmaco determina, mediante negoziazione, i prezzi dei farmaci rimborsati dal Servizio sanitario nazionale. (20A03810). Rome: Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n.185. Jul 24 2020; p. 6–10. Italian.

- Briggs AH. Handling uncertainty in economic evaluation and presenting the results. In: Drummond M McGuire A, editors Economic evaluation in healthcare: merging theory with practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. p. 172–214.

- Pagano M, Gauvreau K, Mattie H. Principles of biostatistics. 3rd ed. Boca Raton (FL): CRC/Chapman & Hall; 2022.

- Briggs AH, Gray AM. Handling uncertainty when performing economic evaluation of healthcare interventions. Health Technol Assess. 1999;3(2):1–134. doi: 10.3310/hta3020

- Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of healthcare programmes. 4th. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

- Lazzaro C, Bordonaro R, Cognetti F, et al. An Italian cost-effectiveness analysis of paclitaxel albumin (nab-paclitaxel) versus conventional paclitaxel for metastatic breast cancer patients: the COSTANza study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:125–135. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S41850

- Aungsumart S, Apiwattanakul M, Filippi M. Cost effectiveness of rituximab and mycophenolate mofetil for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder in Thailand: economic evaluation and budget impact analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0229028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229028

- Exuzides A, Sheinson D, Sidiropoulos P, et al. The costs of care from a US claims database in patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. J Neurol Sci. 2021;427:117553. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2021.117553

- Glick HA, Doshi JA, Sonnad SA, et al. Economic evaluation in clinical trials. 2nd. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014.

- Beekman J, Keisler A, Pedraza O, et al. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: patient experience and quality of life. Neurol(r) Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammation. 2019;6(4):e580. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000580

- Levy M, Fujihara K, Palace J. New therapies for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(1):60–67. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30392-6

- Knapp RK, Hardtstock F, Wilke T, et al. Evaluating the economic burden of relapses in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: a real-world analysis using German claims data. Neurol Ther. 2022;11(1):247–263. doi: 10.1007/s40120-021-00311-x

- Brouwer W, Rutten F, Koopmanschap M. Costing in economic evaluations. In: Drummond M McGuire A, editors Economic evaluation in healthcare: merging theory with practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. p. 68–93.

- Neumann PJ, Ganiats TG, Russell LB, et al. editors, Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. 2nd. (NY) (NY): Oxford University Press; 2016.