ABSTRACT

Objective

To report on the process of developing the Lebanese Economic Evaluation Guideline (LEEG), and to provide relevant material that could assist guideline developers in the future.

Methods

The development of the LEEG closely followed the process proposed by the World Health Organization, i.e. to set up a Guideline Development Group (composed of three Lebanese experts), to establish the rationale for developing the guideline in Lebanon, to identify its scope, to search and retrieve evidence through two systematic reviews, to assess and present the evidence, to translate the evidence into guidelines and recommendations through a deliberative process, and to consult international experts. The deliberative process included a survey, an in-person interview, and a consensus workshop with 16 Lebanese key stakeholders. Data was collected and quantitative analysis was conducted using SPSS software. International experts from Maastricht University - The Netherlands were consulted for issuing the LEEG. Supported by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health (MoPH), the LEEG will be available for public consultation on the MoPH’s webpage, and a final version will be made available thereafter.

Conclusion

Clear and transparent reporting of the guideline development process should support international organizations as well as other developers in establishing their guidelines within their national context.

1. Introduction

Within the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) framework, Economic Evaluation (EE) studies provide information about cost-effective health intervention [Citation1]. In some countries, these pharmacoeconomic tools are used merely to calculate pharmaceutical benefits, while in others, they are mandatory for decision-making and reimbursement related to the pricing of health interventions [Citation2–4]. In Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs), these tools are used to make health interventions accessible to larger subgroups [Citation5]. In a survey of Health Economics (HE) researchers located in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, 83% of participants considered the absence of national methodological guidelines as a barrier to conducting EE [Citation6], because it is more effective for a country to develop and adhere to its own guidelines than to adopt those developed by other countries [Citation7,Citation8]. Consequently, many countries were unable to adhere to the international Decision Support Initiative (iDSI) reference case, which aims at improving the quality and comparability of cost-effectiveness analyses [Citation8]. This could be attributed to the preference for their own national guidelines. If health system arrangements such as Universal Health Coverage (UHC) are ever to be adopted by LMICs, Economic Evaluation Guidelines (EEGs) are required to increase standardization and improve the quality of the economic methods applied [Citation4,Citation9–11].

Several international organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Network of Agencies for HTA (INAHTA), and the Guidelines International Network (GIN), have emphasized the importance of having a transparent and evidence-based process for developing national guidelines [Citation11–13]. Since such Health System Guidance (HSG) provides key inputs for decision-making, its development should follow a systematic process with transparent and reported steps [Citation14]. There are two important domains in the development process: the ‘participants’ domain, which focuses on the composition of the HSG development team, and the ‘methods’ domain, which focuses on determining systematic methods and transparency in reporting along with the best available and up-to-date evidence [Citation11]. Effective multisectoral capacity and an explicit systematic approach to development and reporting is fundamental to ensuring high-quality guidelines [Citation11,Citation14]. Unfortunately, most of the methodological weaknesses and gaps in LMIC EEGs directly correlate with the low quality of the ‘participants’ and ‘methods’ domains [Citation11]. To remedy this deficiency, it is crucial for LMICs to develop a systematic approach to evidence searches, evidence translation, and evidence synthesis, along with a deliberative process involving different stakeholders [Citation12,Citation15–18]. Despite the importance of these factors in developing decent guidelines, very few countries, specifically LMICs, have given them much consideration [Citation11].

In Lebanon, the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) is the regulatory authority for health and the party responsible for HSG development, establishment, and implementation [Citation19]. No EEG has yet been set for Lebanon [Citation4,Citation19–21]. Like many GCC high, and middle-income countries, Lebanon needs an EEG to be a pillar of evidence-informed policy-making for health [Citation6,Citation21,Citation22]. However, after 25 years of classification by the World Bank as an upper-middle income country, in 2022–2023 Lebanon’s economic standing was reclassified downward to status as a lower-middle income country (World Bank Classification). Moreover, Lebanon’s hardships have been compounded by multifold crises, including economic and financial collapse, the COVID-19 pandemic and its repercussions, the explosion in and extensive damage to the Beirut port, and the consequences of Ukraine war [Citation23].

All of these crises have had a severe impact on the Lebanese healthcare sector [Citation24,Citation25]. Even before these misfortunes, the Lebanese population was characterized by a high prevalence of chronic diseases and difficulty in accessing basic health care services [Citation25]. Consequently, the MoPH in collaboration with the WHO identified the need for an HTA committee. However, to achieve this strategic goal, the committee must have an EEG on which to establish its operating procedures [Citation26].

In recognition of Lebanon’s need for an EEG to support evidence-based decision-making, we developed the Lebanese Economic Evaluation Guideline (LEEG). In this paper, we aim to provide a transparent report on the process of developing the LEEG to be adopted at the national level. In addition, by explicitly describing the steps of the development process, we hope to contribute relevant material to assist other guideline developers, especially in LMICs, in developing their own national guidelines.

2. Methodological approach

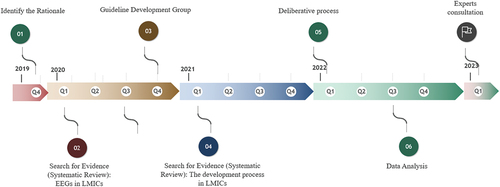

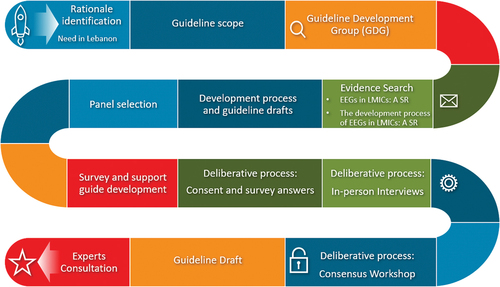

The development of the LEEG consisted of a structured, systematic, and transparent process following various clearly defined steps as set out below. We followed a similar process to the one proposed by the WHO: i.e. to set up a Guideline Development Group (GDG) along with an external review group, to establish the rationale for developing the guideline, to identify its scope, to search and retrieve evidence, to assess and present that evidence, and to translate the evidence into guidelines and recommendations through a deliberative process [Citation12]. The process itself consisted of a combination of qualitative and quantitative data collection. summarizes the steps of the LEEG development process, from identifying the rationale to the experts’ consultation.

Figure 1. A summary of the development process. This summary covers all the steps followed to the development of LEEG, from the rationale identification to the experts consultation.

2.1. Step 1. Identification of the rationale for developing the LEEG

EEGs are an invaluable tool in a society where healthcare resources are scarce (Yue, 2021). In 2017 and 2022, the MoPH’s health strategy plans focused on the need for laws to reorient health care spending to more cost-effective alternatives [Citation26,Citation27]. For example, Lebanese EEGs are to be used to guide healthcare spending in the context of UHC and to standardize EE studies.

2.2. Step 2. Guideline scope

The LEEG will focus on EE methods for the following end users:

As a tool for Lebanese policymakers and payers to make decisions and allocate their scarce resources;

As a guide for pharmaceutical companies to assist with their reimbursement submissions;

As a guide for researchers to conduct EE studies; and

As a supported practice for optimizing health care access for patients.

2.3. Step 3. Guideline Development Group (GDG)

As shown in , the GDG is composed of the coordinator (R.K.), who is an expert in health systems and representative of potential users; R.R., an expert in HTA and health economics; and C.D., an expert in research synthesis and knowledge translation. R.K. is a PharmD, PhD, and Professor at the Lebanese University – Faculty of Sciences and Medical Sciences, a quality assurance Director of the Pharmaceutical Products Program at the Ministry of Public Health, and Chair of the ISPOR Arabic Network. R.R. is an Assistant Professor at the Lebanese American University with a PhD in HTA. C.D. is an affiliate at the HE and Technology Assessment Center and PhD candidate in HTA at Maastricht University in The Netherlands. The international experts and reviewers are S.E and M.H., both from Maastricht University in The Netherlands. S.E. is a Professor in Public HTA, and M.H. is an Associate Professor in HE and HTA.

Table 1. Guideline development group.

2.4. Step 4. Search for evidence

The purpose of this step was to review the general characteristics and key features of other EEGs developed in LMICs, and to review the steps followed by these countries. As the preferred sources for evidence are systematic reviews [Citation12], the authors systematically reviewed the EEGs and their development process in LMICs [Citation4,Citation11]. This step followed the preferred methods for reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis, and the systematic reviews were conducted as per a protocol that was registered a priori. The search strategy was validated by a medical information specialist. The search covered many scientific databases as well as grey literature, was broad, and without restrictions on language or publication date. Full-text screening and data extraction were undertaken independently, in duplicate, based on pre-defined forms.

The first systematic review, entitled ‘Economic evaluation guidelines in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review,’ investigated which LMICs had developed their guidelines, to systematically review these guidelines, and to explore the similarities and differences between them [Citation4]. The evidence retrieved was used to draft the statements describing each key feature that was included in the study survey, along with the proposed choices presented to the participants (Supplementary material 1). The stated choices refer to different recommendations by LMICs, along with the choices adapted for the Lebanese context.

In the second systematic review, entitled ‘The development process of economic evaluation guidelines in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review,’ the authors systematically identified the steps followed by LMICs in the development of their EEGs [Citation11]. A quality assessment of this development process was conducted, using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation-Health Systems (AGREE-HS) tool. This work revealed the need for a well-structured development process to establish a quality EEG. In addition, this work was used to explore the steps needed for such a process and to draft the LEEG development process.

2.5. Step 5. Development process and guideline drafts

Based on the findings identified in the systematic reviews (see Step 4: Search for evidence), the GDG drew up a protocol for developing the LEEG () from which a draft guideline emerged. Following a predefined protocol tailored to the Lebanese healthcare system, we developed the LEEG.

2.6. Step 6. Panel selection

Development of the LEEG involved 16 Lebanese key stakeholders with varying levels of expertise in health economics and different backgrounds. Participants were selected deliberately and impartially, based on their engagement in the healthcare system. They represented decision-makers (i.e. Lebanese payers and the MoPH) and other stakeholders in the Lebanese healthcare system. Participants were asked to provide input and feedback for issuing recommendations. Information on their respective affiliations (e.g. payer, pharmaceutical sector, academia, and policymakers), position, discipline, and educational background are presented in . Half of the participants involved in the LEEG development process were decision-makers (n = 8); the other half represented a variety of pursuits. The 16 participants comprised the following:

One from a cancer patient support association, who represented Lebanese patient advocacy groups;

One representing Lebanese bioethicists;

One representing Lebanese academicians;

Two representing hospitals and private insurance as private payers in the Lebanese context;

Six representing the public payers – one from the National Social Security Fund, one from the Civil Servants Cooperative, three from the MoPH as a public payer, and one from the Military Funds;

One representing nurses in Lebanon;

Two representing physicians (one oncologist and one nephrologist);

One representing pharmacists;

One representing the Lebanon chapter of the professional society for health economics and outcomes research (ISPOR).

Table 2. Participants’ information.

2.7. Step 7. Survey and support guide development

Based on the evidence retrieved from the two above-mentioned systematic reviews [Citation4,Citation11] we identified the key features and adapted them to formulate the survey (see Supplementary material 1). It includes:

An introductory section describing the scope of the project,

Seven questions referring to the general characteristics of the guidelines, four in the form of a seven-point Likert-scale question and three in the form of a closed-ended question. The focus was on the LEEG’s needs, its importance in decision-making, and its applicability. The goal was to provide insight into the target audience in order to pinpoint the most useful type and purpose of the guideline.

Two questions related to the participant’s background and expertise, in the form of one seven-point Likert-scale question and one closed-ended question.

Twenty-two closed-ended questions referred to the key features of the EEG as adapted from information provided by the ISPOR.

A support guide was formulated and sent alongside the survey. It included a brief methodological explanation of the key concepts of the general characteristics and key features of the proposed guideline.

2.8. Step 8. The deliberative process

2.8.1. Consent and survey answers

An introductory e-mail was sent to all participants. It included a clear description of the project with its intended goal, the consent form for participation, the survey document, the support guide, and the published version of the two relevant systematic reviews [Citation4,Citation11]. All key stakeholders (n = 16) agreed to participate in the study and completed the surveys (100% response and completion rates).

2.8.2. In-person interviews

After consent was given and the survey completed, C.D. reviewed the answers. According to the participant’s time and place preference, C.D. arranged a face-to-face interview of up to 60 minutes with each participant. After obtaining the participant’s consent, all interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim, and then translated into English. During these interviews, open-ended questions were asked to validate the survey’s data and to collect further insights and opinions regarding the LEEG’s implementation. C.D. was the interviewer and R.R. was the note-taker. All 16 key stakeholders were interviewed (100% response and completion rates). A summary of the interviews is presented in Supplementary Material 2.

2.8.3. Consensus workshop

Based on the results of the survey and the interviews, the GDG identified several discrepancies that required consensus. Discrepancies were defined as general characteristics and key features that had a cumulative percentage of less than 50%, along with key features that had a cumulative percentage of between 50–60%. These discrepancies were presented for reconsideration in a consensus workshop. Accordingly, a virtual meeting was organized, where a poll for each recommended key feature was launched, and the participants could independently decide on the key features requiring consensus. The participants’ answers were analyzed instantly and the results shared directly with the participants. Of the 16 key stakeholders, 75% (n = 12) participated in the consensus workshop.

After each step of the deliberative process (i.e. survey completion, in-person interviews, and consensus workshop), data was collected and a quantitative analysis was conducted using SPSS software, version 28 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). Descriptive statistics – i.e. mean, standard deviation, and range for quantitative variables; frequency and percentage for categorical variables – were calculated for the guideline’s general characteristics and key features. Additionally, we statistically analyzed the frequency and percentage of decision-makers’ responses for each general characteristic and key feature.

The consensus workshop was an opportunity for the GDG to collectively decide how to address aspects of the LEEG about which there was disagreement. Initially there was a suggestion that this situation might call for use of the Delphi technique to reach consensus. However, the method ultimately adopted allowed for a more immediate and deliberative process to focus on the specific, resource poor needs of Lebanon.

2.9. Step 9. Draft guideline

Following data analysis of the consensus workshop’s outcome, the GDG issued a draft of the guideline. This draft included the general characteristics and the key features of the LEEG and was the subject of discussion and consultation with experts.

2.10. Step 10. Experts’ consultation

The GDG experts reviewed the guideline draft and amended it to produce the guideline document. The unresolved discrepancies from the consensus workshop were also presented to the experts, in addition to other key features results, and discussed with the GDG. This consultation step was fundamental to ensuring good practice and implementability of the LEEG in the Lebanese health care system. With the support of the Lebanese MoPH and a willingness to adopt it, the LEEG will be available for public consultation on the MoPH’s webpage. A final version will be made available thereafter. presents the LEEG timeline from inception to experts’ consultation.

3. Discussion

Considering the crises from which Lebanon is suffering and the population’s need to access basic health care services, it is evident that the LEEG is important to Lebanon’s ability to mount a response that positively impacts its health care system. Furthermore, an effective HTA and economic evaluation would improve access to better healthcare technologies. To accomplish these goals, however, development of the LEEG must be founded upon a transparent and evidence-based process that ensures improved quality of data and comparability of cost-effectiveness analyses, as well as continued public trust in its application after implementation.

Surprisingly few high-income countries have reported on the process of developing their guidelines [Citation11]. Even countries that are considered pioneers in the development of EEGs, such as Australia or the United Kingdom, have remained silent about their development process [Citation28,Citation29]. Canada, on the other hand, is an example of a high-income country that has explicitly reported on the development process [Citation30]. In revising its previous edition, Canada identified gaps within certain topic areas and commissioned research accordingly. Methodological advancements in health economics were considered, other economic evaluation guidelines were reviewed, and health economic experts were consulted. Like Canada, Lebanon reviewed EEGs from other countries and consulted experts.

In middle-income countries, the steps for developing EEGs were inconsistent [Citation11]. For example, when developing their guidelines, Colombia, Cuba, Egypt, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand reviewed the guidelines of other countries that had already established an EEG. In addition, Bhutan, Brazil, China, Cuba, Egypt, Malaysia, Mexico, the Philippines, and Thailand arranged workshops and consultation meetings for experts and stakeholders to propose recommendations and updates of their EEG. Lebanon followed the process adopted by Cuba, as that country had included the steps of its guideline preparation procedure in its methodological guide for the economic evaluation of its health care system. Cuba reviewed the economic methodological guides from different countries, organized a consensus workshop, and concluded with a consultation with international experts and organizations [Citation31]. Like Thailand and Egypt, Lebanon reported independently on the development process of their EEGs [Citation32–34].

The LEEG development follows the detailed process proposed by the WHO [Citation12]. Precautions were taken to avoid competing interests and any influence by the funding agency on guideline development [Citation12]. Consulting with international experts provided indispensable support to the GDG and to ensuring that HE fundamentals were applied within the LEEG. As is the case in the majority of middle-income countries such as Bhutan, Brazil, Cuba, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, the Russian Federation, and South Africa, where EEGs are supported by the Ministry of Health, the adoption and implementation of the LEEG are endorsed by the MoPH in Lebanon [Citation11,Citation35].

In Lebanon, process transparency was considered an important aspect of guideline development. While some high-income countries agreed with this perspective, not all of them did. For example, Canada’s Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) named the members of the guidelines working group and the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) briefly described the major roles of their guideline development team [Citation28,Citation30,Citation36]. However, Australia’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) did not even report the disciplines of its guideline developers. Similarly, middle-income countries tended to poorly disclose their development team [Citation11]. In contrast, Lebanon, like Egypt and Indonesia, opted for transparency by disclosing the make-up of the teams engaged in developing the guideline. It is hoped that this transparency by the GDG, with its expertise and knowledge, will help to strengthen the trust of stakeholders and their willingness to adopt the LEEG. Further, it is planned for the LEEG to be published independently.

In developing the LEEG, the GDG deserves considerable recognition for the many challenges that had to be overcome. Functioning against a backdrop of severe economic and financial crisis, a massively destructive explosion in the country’s main port, and the demands of the COVID-19 pandemic, their dedication in developing the guideline was remarkable. Lebanese healthcare stakeholders were preoccupied by the demands of procuring resources in various crises and providing healthcare access to patients; convincing them to engage in the LEEG project at that time required the project coordinator’s constant intervention and extraordinary commitment, as well as a talent for diplomacy. Additionally, the project was extremely fortunate to have the support of exceptional healthcare experts in Lebanon, who were able to navigate the fragmented healthcare sector to identify and select people to provide a balanced representation of the various fields. The work of all these individuals was made more challenging by the COVID-19 pandemic: the entire deliberative process, including the consensus workshop, had to be organized and accomplished virtually. Although all steps were considered to be helpful and complimentary, a Delphi panel could be an option in the future, instead of a consensus workshop, in countries with a large number of stakeholders involved in the development process.

Last but not least, the development of LEEG exercised best practices as endorsed by the WHO for developing an EEG, from identification of its rationale until its issue [Citation12]. Best practices as established by the Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation Enterprise – Health Systems tool (AGREE-HS) were adopted for the reporting process [Citation37].

4. Strengths and limitations

Involving Lebanese key-stakeholders with different expertise and backgrounds fulfilled the requirement for a diverse understanding of evidence and methodological criteria in the context of a deliberative process [Citation12]. In comparison with the Delphi method, the process adopted for the LEEG was more elaborative and resource-oriented. During our consensus workshop, the discussion was inhibited to insure and emerge creativity [Citation38]. The 100% response rate in survey completion and interviews revealed the level of stakeholder interest and eagerness for the opportunity to have a national EEG to support decision-makers in allocating their scarce resources in the fragmented Lebanese healthcare system. Furthermore, we note that there was no evidence that the enthusiastic response by stakeholders was in any way influenced by the funding agency.

However, this study has its limitations. Although the panel represented the target population of the LEEG, the number of participants (n = 16) was small. Additionally, during the workshop a few participants were absent due to travel obligations, so that the participation rate (n = 12) was less than complete. Moreover, the level of HE expertise varied. Some participants were extremely knowledgeable and experts in health economics, while others had more limited knowledge of health economics and their recommendations were based on their respective organizations’ vision. Furthermore, consensus was not reached for all discrepancies. In those cases, the experts’ consultation, although necessary for the process as demonstrated in several high- and middle-income countries, overrode the deliberative process aim.

5. Conclusion

This study detailed the methodological approach used in developing an EEG for Lebanon. It showed that EEGs are most effective when they are founded upon a transparent and evidence-based process that ensures improved quality of data and comparability of cost-effectiveness analyses, as well as continued public trust in its application after implementation. A clear, transparent, and systematic approach fulfills the need for a tool to develop economic evaluation guideline. It is hoped that by sharing our approach to the development of the LEEG, it can serve as a basis for effective decision-making and efficient use of scarce resources for other EEGs or HSGs, whether at the national or international level. In the context of Lebanon, it is hoped that the transparency made plain in developing the LEEG will strengthen the trust of those conducting EE studies, improve implementation, and benefit Lebanon’s health care system as a whole.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Authors contributions

All authors were involved in the concept and design of the LEEG. R Karam was the project coordinator, R Rizk was the expert in Health Technology Assessment and Health Economics, and C Daccache was the expert in research synthesis and in knowledge translation. C Daccache performed the searches. C Daccache and R Karam contacted the Lebanese stakeholders. C Daccache reviewed the survey responses. In the interviews, C Daccache was the interviewer and R Rizk was the note-taker. During the workshop, R Karam was the moderator and C Daccache was the presenter. S Evers and M Hiligsmann were the international experts. C Daccache drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The content of this manuscript has not been published nor is being considered for publication elsewhere.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (540 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all Lebanese key stakeholders whose participation was of great value to the development of the Lebanese health economic evaluation guideline.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2023.2280213

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: from value for money to value-based health services: a twenty-first century shift. 2021 policy brief. [Cited 2023 Oct 19]. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240020344

- Miot J, Thiede M. Adapting pharmacoeconomics to shape efficient health systems en route to UHC - Lessons from two continents. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:1–5. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00715

- Nagi MA, Rezq MAA, Sangroongruangsri S, et al. Does health economics research align with the disease burden in the middle East and North Africa region? A systematic review of economic evaluation studies on public health interventions. Glob Heal Res Policy. 2022;7(25). doi: 10.1186/s41256-022-00258-y

- Daccache C, Rizk R, Dahham J, et al. Economic evaluation guidelines in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2022;38(1). doi: 10.1017/S0266462322000186

- World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: institutionalizing health technology assessment mechanisms: a how to guide. Ed. Bertram M, Dhaene G, Edejer TTT. 2021 [Cited 2023 Oct 19]. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240020665

- Almazrou SH, Alaujan SS, Al-Aqeel SA. Barriers and facilitators to conducting economic evaluation studies of Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries: a survey of researchers. Health Res Policy Sys. 2021;19(71):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12961-021-00721-1

- Eljilany I, El-Dahiyat F, Curley LE, et al. Evaluating quantity and quality of literature focusing on health economics and pharmacoeconomics in Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;18(4):403–414. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2018.1479254

- Emerson J, Panzer A, Cohen JT, et al. Adherence to the iDSI reference case among published cost-per-DALY averted studies. PLoS One. 2019;25(5):1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205633

- Guide to economic analysis and Research (GEAR) [Internet]. Mind maps: what are the difficulties in conducting health economic evaluations in low- and middle-income countries? Technical (methodological) difficulties (a list of six separate links to various topics) [Cited 2023 Oct 19]. Available online at: http://gear4health.com/gear/difficulties-in-conducting-health-economic-evaluations

- Luhnen M, Prediger B, Neugebauer EAM, et al. Systematic reviews of health economic evaluations: a structured analysis of characteristics and methods applied. Res Synth Methods. 2019;10(2):195–206. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1342

- Daccache C, Karam R, Rizk R, et al. The development process of economic evaluation guidelines in low- and middle- income countries: a systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2022;38(1):1–8. doi: 10.1017/S0266462321000659

- Bosch-Capblanch X. Handbook for supporting the development of health system guidance: supporting informed judgements for health system policies. Swiss Trop Public Health Inst Swiss Centre Inter Health. 2011 [Cited 2023 Oct 19];(July):2–176. Available at: https://www.swisstph.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/WHOHSG_Handbook_v04.pdf

- Guidelines International Network [Internet]. Pitlochry, Scotland: welcome to guidelines international Network [Cited 2023 Oct 19]. Available at: https://g-i-n.net/

- Bosch-Capblanch X, Lavis JN, Lewin S, et al. Guidance for evidence-informed policies about health systems: rationale for and challenges of guidance development. PLOS Med. 2012;9(3). doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001185

- Ako-Arrey DE, Brouwers MC, Lavis JN, et al. Health systems guidance appraisal – -a critical interpretive synthesis. Implement Sci. 2016;11(9). doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0373-y

- Lavis JN, Røttingen J-A, Bosch-Capblanch X, et al. Guidance for evidence-informed policies about health systems: linking guidance development to policy development. PLOS Med. 2012;9(3). doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001186

- Bond K, Stiffell R, Ollendorf DA. Principles for deliberative processes in health technology assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2020;36(4):445–452. doi: 10.1017/S0266462320000550

- Oortwijn W, Husereau D, Abelson J, et al. Designing and implementing deliberative processes for health technology assessment: a good practices report of a joint HTAi/ISPOR task force. Value Health. 2022;25(6):869–886. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2022.03.018

- Republic of Lebanon Ministry of Public Health [Internet – NB: button available on website to translate all text into English]. Beirut, Lebanon. [Cited 2023 Oct 19]. Available at: https://moph.gov.lb/

- Rida NA, Ibrahim MIM, Z-U-D B. Pharmaceutical pricing policies in Qatar and Lebanon: narrative review and document analysis. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2019;10(3):277–287. doi: 10.1111/jphs.12304

- Dahham J, Rizk R, Hiligsmann M, et al. The economic and societal burden of multiple sclerosis on Lebanese society: a cost-of-illness and quality of life study protocol. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2022;22(5):869–876. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2022.2008242

- Alkhaldi M, Basuoni AA, Matos M, et al. Health technology assessment in high, middle, and low-income countries: new systematic and interdisciplinary approach for sound informed-policy making: research protocole [sic]. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:2757–2770. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S310215

- World Bank. Washington, DC: the world by income. 2022 [cited 2023 Oct 19]. Available at: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/the-world-by-income-and-region.html

- Fleifel M, Farraj KA. The Lebanese healthcare crisis: an infinite calamity. Cureus. 2022;14(5). doi: 10.7759/cureus.25367

- Boulanger E. 2021 multi- sector needs assessment. 2022 Apr.

- Republic of Lebanon Ministry of Public health [Internet – NB: button available on website to translate all text into English]. Beruit Lebanon: Lebanon National Health Strategy –Vision; 2030 [Cited 2023 Oct 19]. Available at. https://www.moph.gov.lb/en/Pages/0/67043/lebanon-national-health-strategy-vision-2030

- Republic of Lebanon Ministry of Public health [Internet – NB: button available on website to translate all text into English]. Beirut, Lebanon: Strategic Plan For The Medium Term (2016 To 2020). 2016, Pub 2017 [Cited 2023 Oct 19]. Available at: https://www.moph.gov.lb/en/Pages/9/1269/strategic-plans#/en/view/11666/strategic-plan-2016-2020-

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Manchester, England: Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013. [Citation 2023 Oct 19] Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg9/chapter/foreword

- CADTH (Canada’s drug and health technology agency). Canada: Ottowa, Ontario, Canada: Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies; 4th 2023 [Citation 2023 Oct 19]. Available at. https://www.cadth.ca/guidelines-economic-evaluation-health-technologies-canada-0

- Australian Government department of health and Aged Care, Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee. Canberra, Australia: Guidelines For Preparing a Submission To The Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC). Version 5. 2016 Sep [Citation 2023 Oct 19]. Available at: https://pbac.pbs.gov.au/

- González G, Maria A. Guia metodologica para la evaluacion economica en salud. Cuba 2003. [Methodological guide for economic evaluation in health. Cuba 2003. Rev Cubana Salud Pública. 2003;30(1):37–54. Available at. https://www.academia.edu/11413612/MINISTERIO_DE_SALUD_P%C3%9ABLICA

- Teerawattananon Y, Chaikledkaew U. Thai health technology assessment guideline development (special article). J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91(Suppl 2):S11–15. Available at. https://www.hitap.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Teerawattananon-2008-Thai-health-technology.pdf

- Chaikledkaew U, Kittrongsiri K. Guidelines for health technology assessment in Thailand (2nd ed.) – the development process. J Med Assoc Thail. 2014;97(Suppl 5):S4–9. Available at. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264634825_Guidelines_for_health_technology_assessment_in_THailand_second_edition-the_development_process

- Elsisi GH, Kaló Z, Eldessouki R, et al. Recommendations for reporting pharmacoeconomic evaluations in Egypt. Value Health Reg Issues. 2013;2(2):319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2013.06.014

- World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: Advancing the right to health: the vital role of law. 2017 WHO publication. [Citation 2023 Oct 19]. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511384

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Manchester, England: developing NICE guidelines: the manual. Pub 2014; updated 2023. [Citation 2023 Oct 19]. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg20/chapter/introduction

- Appraisal of Guidelines Research & Evaluation Trust (AGREE). Appraisal of guidelines Research & evaluation — health systems (AGREE-HS). 2018 [Citation 2023 Oct 19]. Available at: https://www.agreetrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/AGREE-HS-Manual-March-2018.pdf

- Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, et al. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20476. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020476