ABSTRACT

Introduction

Fifty years since Dr Tudor-Hart’s publication of the ‘Inverse Care Law’, all-cause mortality rates and COVID-19 mortality rates are higher in more deprived areas. Part of the solution is to increase access and availability to healthcare in underserved and deprived areas. This paper examined how socio-economically representative the undergraduate general practice placements are in Northern Ireland (NI).

Methods

A quantitative study of general practices involved in undergraduate medical placements through Queen’s University Belfast, comparing practice lists by deprivation indices, examining both blanket deprivation and deprivation quintile trends for teaching and non-teaching practices.

Results

Deprivation data for 135 teaching practices were compared against the 323 NI practices. Teaching practices had fewer patients living in the most deprived quintiles compared with non-teaching practices. Fewer practices with blanket deprivation were involved in undergraduate medical education, 32% compared with 42% without blanket deprivation. Practices in areas of blanket deprivation were under-represented as teaching practices, 10%, compared to 14% of NI general practices that met this criterion.

Conclusion

Practices with blanket deprivation were under-represented as teaching practices. Exposure to general practice in deprived areas is an essential step to improving future workforce recruitment and ultimately to closing the health inequalities gap. Ensuring practices in high-need areas are proportionately represented in undergraduate placements is one way to direct action in addressing the ‘Inverse Care Law’. This study is limited to NI and further work is required to compare institutions across the UK and Ireland.

Introduction

People living in areas of deprivation have a disproportionate burden of disease [Citation1]; experiencing greater disease complexity, multi-morbidity and psychological problems [Citation2]. This was further exposed during the COVID-19 pandemic with those living in the most deprived areas facing the greatest impact [Citation3,Citation4]. Data from the Office for National Statistics early in the pandemic [Citation5] showed death rates from COVID-19 were twice as high in the most deprived, compared to the most affluent, deciles. Marmot and Allen [Citation6] described the impact as ‘a clear social gradient: the more deprived the area the higher the mortality’.

Half a century ago, Tudor-Hart proposed the concept of an ‘inverse care law’; ‘The availability of good medical care tends to vary inversely with the need for it in the population served. This inverse care law operates more completely where medical care is most exposed to market forces, and less so where such exposure is reduced’ [Citation7].

This ‘law’, whereby, those with the highest need are least likely to receive it has been the subject of much analysis over the past year [Citation8–10]. Tudor-Hart went on to explain that medical education propagated the inverse care law, as medical students practised ‘ideal medicine under ideal conditions’ encouraging graduates to; ‘leave those who need them most and go to those who need them least’ (ibid) [Citation7]. A similar deficit was acknowledged by the Independent Commission on the Education of Health Professionals in 2010, concluding that globally: ‘the content, organisation, and delivery of health professionals’ education have failed to serve the needs and interests of patients and populations’ [Citation11].

Creating a proactive undergraduate medical curriculum that integrates deprivation-based practice, is crucial for the future provision of healthcare in areas of deprivation [Citation12,Citation13]. The General Medical Council publication Outcomes for Graduates, which sets the standards for medical curricula in the UK, requires that newly-qualified doctors should be able to recognise the effects of poverty and affluence on health, understand the impact of health inequalities, and the social determinants of health [Citation14].

Work done by the Deep End Project in Scotland highlighted that insufficient exposure for students and trainees to medical issues in the context of areas of deprivation resulted in a lack of confidence, skills, and a reduced desire to work in such areas [Citation15]. A systematic review on clinical placements in underserved areas showed that regardless of a medical student’s background, they were more likely to undertake a formal post in an underserved rural area following a prior student placement [Citation16]. This extends to prospective medical students, with general practice work-experience improving prospective medical students' aspirations to pursue a career in GP [Citation17]. Research in England showed that GP practices engaging in medical education were not necessarily representative of English general practice, being overall more rural, white and in better health [Citation18]. A similar theme was seen in postgraduate training in Scotland, with training GP practices more likely to be in affluent areas [Citation19]. The maxim ‘You don’t know what you don’t know’ applies: expanding students’ exposure to healthcare within areas of deprivation provides a foundational awareness in the first instance and the potential to develop an interest to work in these communities.

There are notable examples of programmes and initiatives run by individual medical schools and third-sector organisations, which aim to increase ‘exposure’ to medical care in areas of deprivation. These include the Difficult and Deprived Areas Programme (DDAP) in the North East of England [Citation20] the work of Fairhealth in medical education [Citation21] and the benefits in recruitment and retention through the work of the Deep End Pioneer Scheme [Citation8]. However, there is little published information about the extent to which this is being intentionally addressed within the undergraduate curricula of UK medical schools.

In recent years, in part due to recruitment and retention issues of GPs, there has been a concerted focus on clinical experience for medical students in the context of general practice [Citation22]. General practice in the UK and Ireland provides healthcare within bounded geographical locations to local populations often sharing a number of characteristics, among them, level of deprivation. The recently published Royal College of General Practitioners and Society for Academic Primary Care digital textbook Learning General Practice [Citation23] provides a framework for medical students with a section dedicated to the social determinants of health. Insufficient exposure to general practice in areas of deprivation potentially sets the foundations for poor recruitment and retention of staff, further propagating the ‘inverse care law’ and worse health outcomes for those living with the highest need: the ‘inverse teaching law’.

In this work, we aimed to pose the question: ‘Do undergraduate general practice placements propagate the “inverse care law” by limiting the opportunity to experience primary healthcare in the areas of highest need, during medical school?’ and to answer the question for the Northern Ireland (NI) context.

In NI, more than 1 in 3 people (37%) live in socio-economic deprivation compared to approximately 1 in 5 in England, Scotland and Wales (18–22%) [Citation24]. The reasons for this are complex and multifactorial, but in part due to the recent history of civil conflict and the ongoing implications for healthcare provision. The ‘Troubles’ refers to conflict spanning three decades resulting in over 3,500 deaths and 30,000 people injured [Citation25]. This legacy is evident in the high exposure to trauma [Citation25,Citation26], the prevalence of ‘diseases of despair’, such as substance misuse and alcohol dependency alongside deprivation [Citation27] and the highest suicide rate with the UK and Ireland [Citation27].

Method

At the time of the study, Queen’s University Belfast (QUB) was the only medical school placing students in general practices, giving a unique insight across NI as a whole, through the clinical placement activity of one institution. Using the National Health Application & Infrastructure Services (NHAIS), aggregated practice-level deprivation data was collated for each GP list across NI.

The Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) Multiple Deprivation Measure 2017 was used, in which the deprivation results are published at Super Output Area (SOA) level [Citation28,Citation29]. There are 890 SOAs in NI. Each SOA has a population range between 1,300 and 2,800 people [Citation30]. These are ranked 1 (most deprived) to 890 (least deprived), placing 178 SOAs in each quintile of deprivation. Individual post-codes can be translated into an SOA. The postcodes of patients registered in each practice were grouped to the quintile of deprivation as per SOA. Using these data quintiles, it was possible to derive the percentage of registered patients in each practice, living in each quintile of deprivation. This allowed for a deprivation profile of all GP practices, within Northern Ireland.

This profiling identified practices with ‘blanket deprivation’ as well as reviewing the mean percentages of patients in each quintile of deprivation. A working definition of a ‘general practice with blanket deprivation’ was chosen as a practice with more than 50% of the registered patient list living in the most deprived quintile of SOAs, as per registered patient postcodes. Using quintile of deprivation is in keeping with the NHS England and the NHS Improvement Core20PLUS5 approach of supporting health inequalities by focusing on the target population in the most deprived 20% [Citation31]. The cut off at 50% of the patient list follows similar definition used in ‘Deep End’ work whereby the ‘Deep End’ is defined as practices with over half (50%) of the patient list in the most deprived cohort as per local indices of multiple deprivation [Citation32]. To enhance the analysis further, the total patient means in each quintile was calculated and compared between teaching and non-teaching practices.

In March 2021, the School of Medicine at QUB had 140 practices actively engaged in hosting undergraduate medical students. These teaching practices were ranked within all 323 general practices using the NHAIS April 2020 data, providing the proportion of patients in each deprivation quintile. This permitted the identification of the number of NI GP teaching practices serving areas of ‘blanket deprivation’, as well as comparisons between percentages of patients living in each quintile of deprivation.

Results

Of the original list of 140 GP practices, 135 were matched to the NHAIS data set, three practices were duplicated on the list, and the remaining two practices did not have enough specific information to identify the exact practice, for instance, based within a health centre with multiple general practices listed at the address provided: therefore they were excluded from the research study.

Fourteen of the 135 (10.4%) general practices receiving medical students as part of their undergraduate medical educational programme were categorised as general practices with blanket deprivation. This compares to 13.6% of practices across NI that meet these criteria ().

Table 1. Breakdown of registered teaching practices by deprivation versus national average.

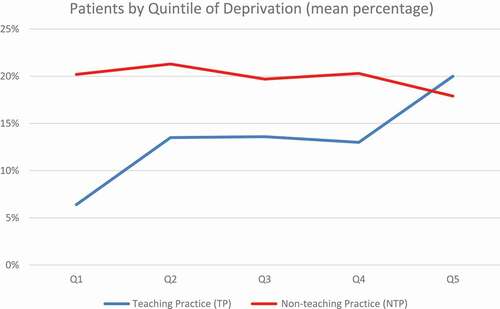

Dividing NI GP practices into blanket versus non-blanket deprivation, 32% of the former and 42% of the latter were involved in medical education. Analysis by patients per quintile of deprivation showed that teaching practices had, on average, fewer registered patients in the most deprived quintiles. shows the average results. Mean average shows increased patient numbers registered to postcodes in the most affluent quintiles. shows the correlation, with teaching practices (TP) trending towards more patients registered in affluent postcodes and therefore least deprived quintiles 4 and 5.

Table 2. Average values for percentages of patients per deprivation quintile for teaching practices (TP) and non-teaching practices (NTP).

Discussion

We found that within Northern Ireland, the current undergraduate general practice placements allowed for some exposure to high need deprived areas, but this was not representative of general practice across Northern Ireland. Thus, it is likely propagating the ‘inverse care law’. When looking at the mean percentage of patients per deprivation quintile, non-teaching practices (NTP) corresponded more closely to the national Northern Ireland picture. This was not the case for teaching practices (TP), where patient populations had lower proportions of patients living in areas of highest deprivation (Q1–Q2). Additionally, the proportion of general practices in areas of blanket deprivation, was below that for NI as a whole, with 10% of QUB teaching practices meeting this criterion compared to the NI average of approximately 14% of practices. This is further compounded by a higher proportion of ‘non-blanket deprivation’ practices being involved in medical education (42%) compared to 32% of blanket deprivation practices.

This finding raises questions about why practices with blanket deprivation are less likely to be involved in undergraduate training. The inequity in workforce of full-time equivalent GPs in areas of deprivation, practically means there are fewer possible trainers and GP tutors [Citation33,Citation34]. As well as the increased work pressures and strains that working in areas of deprivation can have, GPs working in areas of deprivation have increased patient lists [Citation34–36], increased demand for appointments [Citation35], shorter appointments with more complexity [Citation37] and reported higher stress among the workforce [Citation2].

Ongoing engagement in the delivery of medical education at practice level could be an artefact of practice history with the interest, and involvement in teaching, mainly among newly-recruited GP partners. In this way, reluctance to take on teaching or a willingness to give it up due to the pressures highlighted above may mean that attrition to teaching is higher in these blanket deprivation practices.

There may also be patient factors to consider: with higher mental health co-morbidity in areas of high deprivation [Citation35,Citation36,Citation38,Citation39], it is plausible that students are less welcome in the consultations or could add to the complexity faced by the clinician. Practically, there may be factors of space availability [Citation40], with practices in areas of blanket deprivation tending to be situated in more inner-city locations, where the premises may be smaller, with less space to host students. These factors present potential barriers in the ability of a practice in an area of blanket deprivation to host students.

We suggest possible solutions and actions to address these barriers might include (1) active recruitment of practices from areas of deprivation that have never been involved in teaching; (2) incentive schemes; (3) enabling buddying of practices to share workload. We are not aware of any such schemes. It would be incumbent on funders of clinical placements to ensure funding fairness and equity especially when comparing primary and secondary care [Citation40], given the importance of primary care in the future of healthcare.

The next step could be to move beyond simply ensuring there is this adequate and universal coverage of general practices across the socio-economic landscape, instead exploring the extent to which the impact of deprivation is highlighted to students during their clinical placement. It would be helpful to investigate how this impacts post-graduate general practice training programmes, and whether the concept of undergraduate placements propagating the ‘inverse care law’ projects to postgraduate training.

Limitations

The study focuses on general practice placements, and the role of undergraduate primary care placements to propagate or address the ‘inverse care law’, where these high-need areas are comparatively under-doctored [Citation34] (). It does not take into account secondary or hospital placements and how exposure to deprivation varies for undergraduates in these settings. As deprivation data in each jurisdiction is calculated differently, direct comparisons between medical schools across the UK and Ireland, should be undertaken with caution. In NI, using SOA data, deprivation data points and values are not given; therefore, this can under- or over-estimate deprivation, by way of there always being a highest and lowest decile or quintile. It is, however, broadly acknowledged that there is an increased prevalence of deprivation in NI [Citation24], therefore likely that the involvement of practices working in areas of underserved and deprived populations is under-estimated if compared to the UK as a whole, with medical students in NI likely having a higher probability of being exposed to deprivation within the primary care setting.

Table 3. Results table data with the breakdown of each practice.

This work focuses on blanket deprivation: it is possible that a focus on ‘pocket deprivation’ would have merit. Perhaps, a pocket deprivation approach would show that many students do get some experience to the health needs of those in deprived areas, although this would not answer the question around the intentionality of institutions in placing students in the most deprived practices. One approach might be to promote learning activities within these non-blanket deprivation practices to identify disparate health outcomes among selected high deprivation cohorts of these practices.

Conclusion

This paper posed the question: ‘Do undergraduate general practice placements propagate the “inverse care law” by limiting the opportunity to experience primary healthcare in the areas of highest need, during medical school?’ Analysing the intentionality of medical schools in ensuring the doctors of tomorrow are placed in practices reflective of general practice as a whole, is one method of answering it; it is also a method by which to direct action. This study was limited to one institution, covering the entirety of Northern Ireland. It demonstrated under-representation of general practices serving the most deprived populations being involved in undergraduate medical education. Thus, it can be argued that undergraduate placements are currently propagating the ‘inverse care law’, rather than tackling it.

The authors’ institution has launched a new undergraduate curriculum in 2020 within which, when fully implemented in the 2024–25 academic year, 25% of clinical time will be spent in general practice. The insights provided in this paper afford the opportunity to endeavour intentionally to have all students experiencing and reflecting on healthcare in areas of high deprivation, with the ultimate aim of training doctors with an interest to close the health inequalities gap. As Government looks to ‘Level Up’ society and medical schools increase general practice placements, consideration of whether the selection of teaching practices is reflective of general practice is imperative. Failure to do so, may result in more medical students pursuing a career in general practice, but not necessarily in high need, socio-economically deprived areas thus inadvertently, widening inequalities. It is important to continue looking for ways to improve, as Marmot summarised when referring to addressing health inequities and inequalities: ‘Do something, do more, do it better’ [Citation41].

Ethical considerations

The study did not require ethical approval.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Marmot M. Fair society, healthy lives: the Marmot review. Final report. 2010.

- Mercer SW, Watt GC. The inverse care law: clinical primary care encounters in deprived and affluent areas of Scotland. Ann Fam Med. 2007 Nov–Dec;5(6):503–510.

- Michael Marmot JA, Goldblatt P, Herd E, et al. Build back fairer: the COVID-19 Marmot review. In: The pandemic, socioeconomic and health inequalities in England. London: Institute of Health Equity; 2020. p. 12–14.

- Suleman MSS, Webb C, Tinson A, et al. Unequal pandemic, fairer recovery: the COVID-19 impact inquiry report. London: The Health Foundation; 2021.

- Statistics OoN. Deaths involving COVID-19 by local area and socioeconomic deprivation: deaths occurring between 1 March and 31 July 2020. Office of National Statsitics: ONS; 2020.

- Marmot M, Allen J. COVID-19: exposing and amplifying inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020 Sep;74(9):681–682.

- Hart JT. The inverse care law. Lancet. 1971 Feb 27;1(7696):405–412.

- Scotish Deep End Project. 50 years of the inverse care law conference. University of Glasgow; 2021. Available from: https://www.gla.ac.uk/media/Media_823260_smxx.pdf

- Mercer SW, Patterson J, Robson JP, et al. The inverse care law and the potential of primary care in deprived areas. Lancet. 2021 Feb;397(10276):775–776.

- Fisher RAL, Malhotra AM, Alderwick H. Tackling the inverse care law: analysis of policies to improve general practice in deprived areas since 1990. London: The Health Foundation; 2022.

- Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010 Dec;376(9756):1923–1958.

- Poppleton A. Are we propagating the inverse care law as GPs? Br J Gen Pract. 2019 Feb;69(679):64.

- Boelen C. Coordinating medical education and health care systems: the power of the social accountability approach. Med Educ. 2018 Jan;52(1):96–102.

- General Medical Council. Outcomes for graduates. London: General Medical Council; 2018.

- Blane DN. Medical education in (and for) areas of socio-economic deprivation in the UK. Educ Prim Care. 2018 09;29(5):255–258.

- Crampton PES, McLachlan JC, Illing JC. A systematic literature review of undergraduate clinical placements in underserved areas. Med Educ. 2013 Oct;47(10):969–978.

- Agravat P, Ahmed T, Goudie E, et al. Medical applicant general practice experience and career aspirations: a questionnaire study. BJGP Open. 2021;5(3). DOI:10.3399/BJGPO.2021.0023

- Rees EL, Gay SP, McKinley RK. The epidemiology of teaching and training general practices in England. Educ Prim Care. 2016 Nov;27(6):462–470.

- McCallum M, Hanlon P, Mair FS, et al. Is there an association between socioeconomic status of general practice population and postgraduate training practice accreditation? A cross-sectional analysis of Scottish general practices. Fam Pract. 2020;37(2):200–205.

- Crampton P, Hetherington J, McLachlan J, et al. Learning in underserved UK areas: a novel approach. Clin Teach. 2016 Apr;13(2):102–106.

- Fairhealth. [cited 2021 Sep 20]. Available from: https://www.fairhealth.org.uk/home

- Wass V, Gregory S, Petty-Saphon K. By choice—not by chance: supporting medical students towards future careers in general practice. London: Health Education England and the Medical Schools Council; 2016 [ 2020].

- Harding A, Hawthorne K, Rosenthal J. Learning general practice. A digital textbook for clinical students, postgraduate trainees and primary care educators. Royal College of General Practitioners; 2021 [cited 2021 Oct 14]. Available from: https://www.rcgp.org.uk/-/media/Files/GP-training-and-exams/Discover-GP/Medical-students/learning-general-practice.ashx?la=en

- Abel GA, Barclay ME, Payne RA. Adjusted indices of multiple deprivation to enable comparisons within and between constituent countries of the UK including an illustration using mortality rates. BMJ Open. 2016 11;6(11):e012750.

- Cairns E, Darby J. The conflict in Northern Ireland: causes, consequences, and controls. Am Psychol. 1998;53(7):754.

- Bunting BP, Ferry FR, Murphy SD, et al. Trauma associated with civil conflict and posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence from the Northern Ireland study of health and stress. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(1):134–141.

- O’Neill S, O’Connor RC. Suicide in Northern Ireland: epidemiology, risk factors, and prevention. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):538–546.

- Northern Ireland Super Output Areas Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA). 2013 [cited 2021 Jul 14]. Available from: https://www.nisra.gov.uk/support/geography/northern-ireland-super-output-areas

- Northern Ireland Multiple Deprivation Measure 2017 (NIMDM2017) Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA). 2021 [cited 2021 Jul 14]. Available from:. https://www.nisra.gov.uk/statistics/deprivation/northern-ireland-multiple-deprivation-measure-2017-nimdm2017

- Census Geography Office for National Statistics. 2021 [cited 2022 Apr 8]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/geography/ukgeographies/censusgeography#super-output-area-soa

- England NHS. Core20PLUS5 the equality and health inequalities hub. NHS England; [cited 2022 May 7]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/core20plus5/

- Watt G, Deep End Steering Group. GPs at the deep end. Br J Gen Pract. 2011 Jan;61(582):66–67.

- Nussbaum C, Massou E, Fisher R, et al. Inequalities in the distribution of the general practice workforce in England: a practice-level longitudinal analysis. BJGP Open. 2021 Oct;5(5). DOI:10.3399/BJGPO.2021.0066

- Fisher RDP, Asaria M, Thorlby R. Level or not?. The Health Foundation; 2020 [cited 2020 Sep]. Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/level-or-not

- McLean G, Guthrie B, Mercer SW, et al. General practice funding underpins the persistence of the inverse care law: cross-sectional study in Scotland. Br J Gen Pract. 2015 Dec;65(641):e799–805.

- Cassell A, Edwards D, Harshfield A, et al. The epidemiology of multimorbidity in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract. 2018 04;68(669):e245–e251.

- Gopfert A, Deeny SR, Fisher R, et al. Primary care consultation length by deprivation and multimorbidity in England: an observational study using electronic patient records. Br J Gen Pract. 2021;71(704):e185–e192.

- Stafford MSA, Thorlby R, Fisher R, et al. Briefing: understanding the health care needs of people with multiple health conditions. The Health Foundation. 2018. Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/understanding-the-health-care-needs-of-people-with-multiple-health-conditions

- Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012 Jul;380(9836):37–43.

- Harding A, McKinley R, Rosenthal J, et al. Funding the teaching of medical students in general practice: a formula for the future? Educ Prim Care. 2015 Jul;26(4):215–219.

- World Health Organisation. Review of social determinants and the health divide in the WHO European region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2013.